Abstract

Objective Comparative biomechanical analysis of tibial fixation strength for ligament reconstruction with interference screw compared with screw post and washer, and compared with the associated fixation of both methods (hybrid fixation).

Method A total of 54 specimens were used (porcine tibias and bovine flexor digital tendons), which were divided into three groups with fixation types similar to those used in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction: 1) fixation with interference screw; 2) fixation with screw post and toothed washer over knot and suture strand; and )- fixation with screw post and washer combined with interference screw (hybrid fixation). The analyses were performed through pull-out biomechanical tensile tests to determine the stiffness and load to system failure (yield load).

Results The hybrid fixation group presented a significantly higher final stiffness (59.10 ± 3.45 N/mm) in comparison to the other groups ( p < 0.05) and a higher yield load (581.34 ± 33.48 N) compared to the interference screw group ( p < 0.05).

Conclusion Hybrid fixation had biomechanical advantages over the bovine digital flexor graft fixation system in swine tibia during tensile tests.

Keywords: anterior cruciate ligament, surgical fixation devices, tibia

Introduction

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is important not only for the stability of the anteroposterior knee, but also for the entire complex gait kinetics. 1 US studies indicate an incidence of problems in this structure of 68.6/100,000 inhabitants. 2 Most injuries are related to the practice of sports, 3 and, among them, soccer has the highest rates of these injuries. 4

The resistance of the ACL is almost 2,000 N, but valgus knee torsion and internal rotation mechanisms are capable of injuring both the ACL and other knee structures such as the meniscus and cartilage. 5 After the initial inflammatory phase, patients commonly experience a chronic faltering sensation associated with reduced functional capacity, which in many cases points to the need for surgical intervention. 1

The ligament reconstruction technique enables the patients to return to their sports activities. The most commonly used grafts for ACL reconstruction are bone-tendon-bone, which are taken from the central third of the patellar tendon and knee flexor tendons (gracilis and semitendinosus). 6

The graft fixation methods in ACL reconstruction can be suspension, post, compression or hybrid. Post methods promote cortical fixation to the bone, but may use suture/strands as intermediate devices, which provides greater graft mobility within the tunnel. 7 And the compression methods promote direct fixation of the tendon against the cancellous bone of the tibial or femoral tunnel, closer to the joint. 8

Tibial fixation in ACL reconstruction is usually a point of lower resistance than femoral fixation, due to the lower density of the tibial bone and the graft fixation parallel to the tunnel. This generates a slippage force, and may cause early failure of the distal fixation. 9 10

Graft integration into the bone tunnel occurs around the twelfth week; 11 on the other hand, early physical therapy rehabilitation is important for the clinical outcome of ACL reconstruction surgery. Therefore, secure fixation in the immediate postoperative period is essential to prevent further displacement and impairment of the graft integration process. 12

Considering the possibility of failure related to the tibial fixation methods of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, especially regarding the isolated interference screw, 13 combined fixation methods, which are also called hybrid fixation, became widespread. 7 Since then, several studies have been conducted to determine if the addition of methods would effectively improve the initial rigidity of the system. Regarding this matter, there is divergence between studies. 10 14 15

Given this controversy, the present work was conducted through tensile testing, in an animal model, to compare three fixation devices: the interference screw, the washer and wire screw post, and the hybrid fixation (association of the two methods). The hypothesis studied was that the hybrid fixation method has biomechanical advantages over the isolated pressure and post methods.

Methods

A total of 54 porcine shins and 54 bovine forelegs were purchased from a meat processing plant, and they were carefully dissected to extract the deep digital tendon. The tendons were split in half, arranged in small plastic containers filled with 50 ml of 0.9% saline and then stored and frozen at -20° C until the date of testing.

In order to determine the cross-sectional area of the tendons, they were placed in an acrylic box filled with regular set Jeltrate paste (Dentsply, York, PA, US). The tendons were enveloped by the paste until they acquired a rubbery consistency, forming a mold. The paste was removed from the models, keeping the impression of the tendons. These alginate molds were cross sectioned into 10 mm thick blocks and scanned at 600 dpi of resolution per a HP J5780 (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA, US) scanner. The cross-sectional areas of the molds were measured using the Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, US) software. 16 As the pairs of tendons are folded in half to form the quadruple graft, the four smallest areas of each graft were added for the purpose of formal strength calculation, as it is the region of greatest stress on the graft. 17

The models were kept in an environment with controlled temperature (21° C) and humidity for 24 hours before the surgical procedures, 8 and kept hydrated until the traction tests were completed. The tendons and tibias were randomly divided among the groups. The tendon ends were sutured using the 3-loop Krakow technique, occupying 3 cm from the end of each tendon, with Ethibond Polyester 2 (Johnson & Johnson, Piscataway, NJ, US) polyester surgical strand.

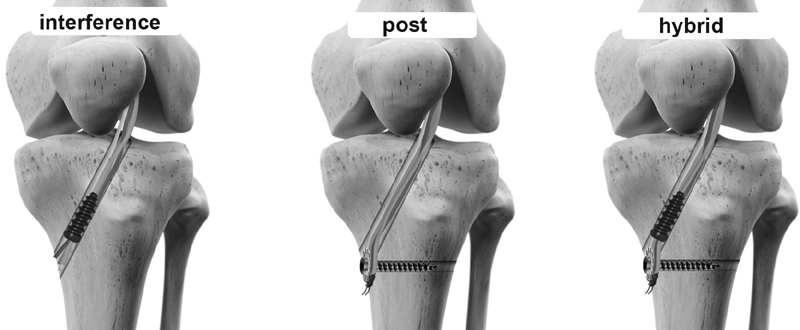

The three groups were then submitted to surgical procedures: the first group, with fixation with a 9 × 30-mm simple metallic interference screw (n = 19), was called the interference group; the second one, with post fixation with cortical screw (40 mm) and toothed washer over the suture knot (n = 18), was called the post group; and the third, with interference screw associated with screw and toothed washer post (n = 17), was called the hybrid group ( Figures 1 and 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Types of fixation (groups).

Fig. 2.

9 × 30-mm interference screw, 40-mm cortical screw, and toothed washer.

The tibial tunnels were made with a conventional guide at 55° and drilled with a cannulated drill with a 9-mm diameter. The graft was inserted into the tunnel until it was 5 cm outside the joint, reproducing a surgical situation closer to reality.

They were then positioned on the clamping device, which consisted of a precision angle vise with jaws designed to enable the clamping of the cylindrical bodies with three planes of freedom, enabling the alignment of the tibial tunnel with the drive shaft of the machine. The distal bone portion of the tibia was fixated to the traction machine by an epoxy-filled polyvinyl chloride (PVC) tube ( Figure 3 ). 18

Fig. 3.

Specimen positioned on the device.

For the tensile testing, the universal testing machine EMIC DL 10000 (Instron, São José dos Pinhais, PR, Brazil)was used, and it was equipped with built-in displacement transducers and an “s” load cell (CCE5KN, Instron) with a maximum nominal load of 500 kgf and a resolution of 0.1 kgf. The results were compiled using the Tesc (Instron) software, and extracted in raw form (displacement and force) for the graph and statistical analysis using Excel 365 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, US) spreadsheets.

The graft was pre-tensioned with a 10 N load for 60 seconds, 19 followed by the 50 mm/min speed test 20 until fixation failure. For the analysis of the results, we used the system rigidity (R R ) by the secant method for light loads (toe-region), the R R by the ordinary least squares method (tangent), and load to system failure (yield load), following the Pearson correlation coefficient 10 and the tension for failure (σR). The first point of the curve at which the graph loses its linearity was considered the load to failure (yield load), similar to the onset of plastic deformity in a metal system.

The statistical analysis for the biomechanical tests was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey multiple comparisons test of the honestly significant difference (HSD), considering values of p ≤ 0.05.

Results

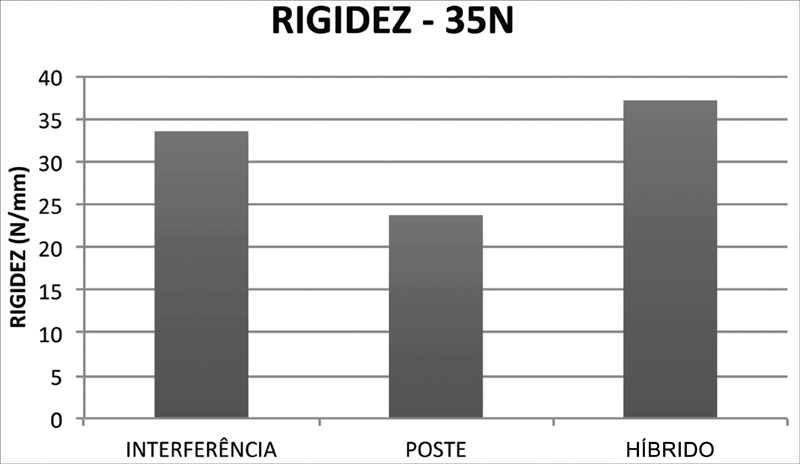

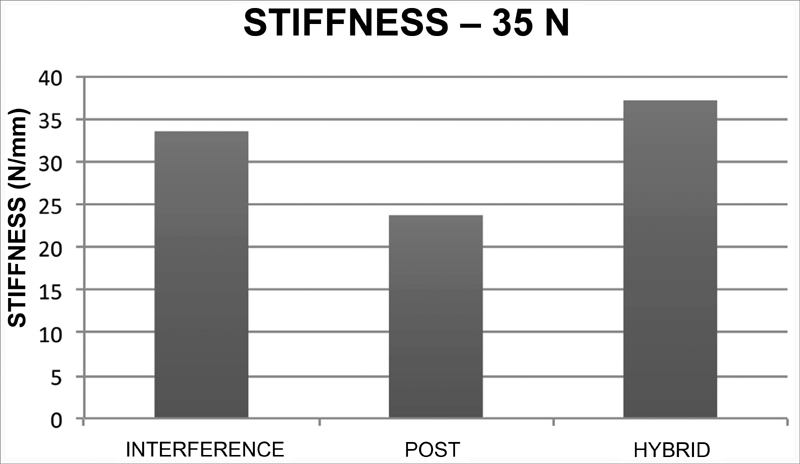

During the graft accommodation phase, described as toe-region , up to 35N, there was less stiffness in the post group (23.72 ± 2.16 N/mm), followed by the interference group (33.52 ± 2.23 N/mm) and the hybrid group (37.13 ± 2.37 N/mm). There was no statistically significant difference between the interference and hybrid groups. But in relation to the post-type system (post group) and pressure-type system (interference and hybrid groups), there were statistically significant differences ( p < 0.05) ( Figure 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Stiffness results until 35 N (N/mm).

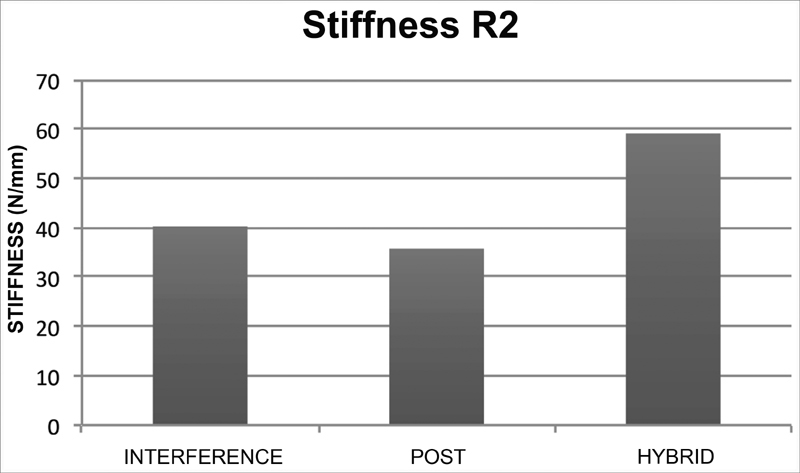

System rigidity to failure was higher in the hybrid group (59.10 ± 3.45 N/mm). The fixation of the post group was the one that reached the lowest stiffness (35.75 ± 3.15 N/mm), lower than the fixation with the interference screw (40.26 ± 3.24 N/mm). There was no statistically significant difference between the interference and post groups in the stiffness calculation by the linearity of the graph (tangent method). Both, however, had lower stiffness than the hybrid system ( p < 0.05) ( Figure 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Results of the final stiffness of the system (N/mm).

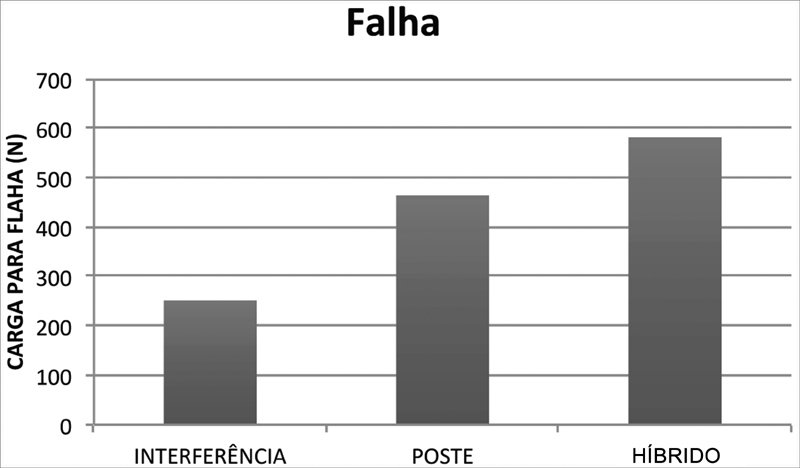

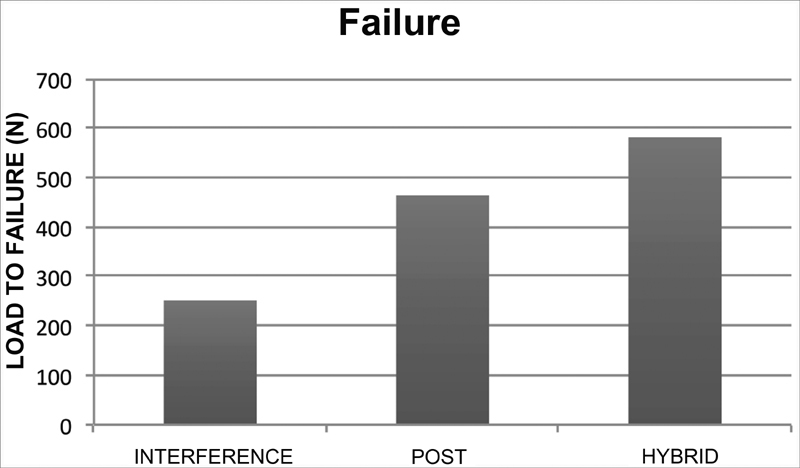

The load to failure in the interference group was of 270.34 ± 31.45 N; for the post group, it was of 463.72 ± 30.57 N; and, for the hybrid group, it was of 581.34 ± 33.49 N. The statistical analysis showed higher resistance in the hybrid group ( p < 0.05), followed by the post group and the interference group ( Figure 6 ). All failures occurred due to slippage and/or suture rupture in the post fixation.

Fig. 6.

System failure results (yield load) (N).

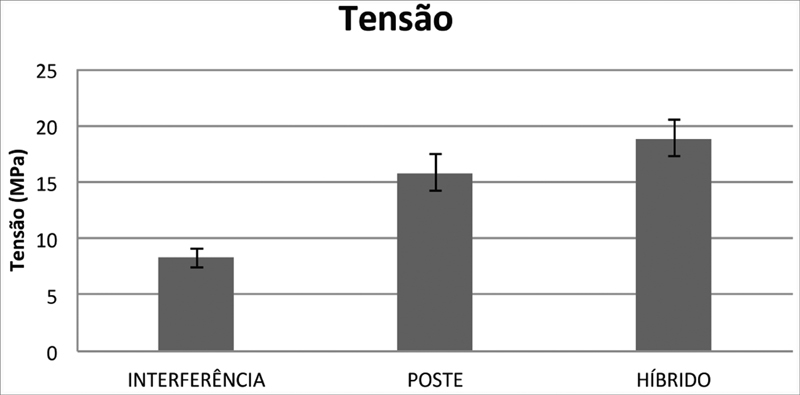

The tension to failure in the hybrid group (18.89 ± 1.66 KPa) showed no statistically significant difference regarding the one from the post fixation group (15.76 ± 1.61 KPa); however, both were statistically different when compared to the interference group fixation (8.31 ± 0.87 KPa) ( p < 0.05) ( Figure 7 ).

Fig. 7.

Tension results for system failure (MPa).

Discussion

The present study was performed using deep digital bovine tendons implanted in pig tibias, which are structures with biomechanical similarities to the human structure. 21 22 The tendon fixation was performed using an interference screw (interference group); a post screw with washer and wire (post group); and with a combination of techniques (hybrid group).

In order to analyze whether the hybrid fixation had biomechanical advantages over the others, each specimen was submitted to a pull-out test, with orientation of the load parallel to the tibial bone tunnel and determination of the rigidity of the system and load to failure (yield load).

During the tensile tests, we found that in the graft accommodation phase, the stiffness in the post group (23.72 ± 2.16 N/mm) was lower when compared to that of the others (pressure-type fixation: 33.52 ± 2.23 N/mm; hybrid fixation: 37.13 ± 2.37 N/mm). Most studies rule out this phase of the biomechanical fixation assay; 10 however, these loads are part of the rehabilitation process after ACL reconstruction surgery. 19 If there is low rigidity in the post fixation system, there may be an impairment in its healing compared to the methods that use pressure fixation. One hypothesis for this result is that the pressure fixation enables a lower initial accommodation than the post-type.

The hybrid fixation method showed higher rigidity than the methods used for the other groups (59.10 ± 3.45 N/mm), with statistical significance. Rigidity is the biomechanical parameter that best relates to the degree of laxity observed in the postoperative clinical examination. 7 These findings suggest that, in the immediate postoperative period, the hybrid method enables a greater system rigidity when compared to the interference screw or post fixation method. 23

The yield load in the hybrid fixation (581.34 ± 33.49 N) group was superior to that of the interference group (270.34 ± 31.45 N), with a statistically significant difference, which is in line with other studies. 14 22 One hypothesis for this increase in resistance is that cortical fixation prevents tendon slippage more effectively than pressure fixation.

Considering the need for a 445-N fixation strength in the postoperative period of ACL ligament reconstruction, 24 only hybrid fixation proved safe within these parameters. The results show that the fixation with the interference screw alone may not be sufficiently secure, not only due to the low resistance values, but also because of the variation in the results.

The tension to failure for the hybrid group (18.89 ± 1.66 KPa) showed no statistically significant difference from the that of the post fixation group (15.76 ± 1.61 KPa); however, both showed a statistically significant difference from the interference fixation group (8.31 ± 0.87 KPa), which is in line with the yield load resistance findings, with no objective influence of the tendon diameter used as grafts in each group. One hypothesis for this is that the tendons had little thickness variation, since they all had the same origin, and those that could not be used in a 9-mm tunnel were not used in the experiment.

These findings reveal that in the hybrid fixation there is a combination of the benefits of the fixation methods, and it maintains adequate stiffness in the first and last phases of the test, with higher load and stress to failure than in other methods.

The present study has limitations, as the use of animal models, which, although acceptable, does not completely replace young human bone, so the results of the present research cannot be extrapolated to absolute values for human surgery. 22 In addition, the use of the pull-out test, despite having scientific value, underestimates the elongation and consequent failure of the fixation system found in cyclic tests. 25

Future studies with cyclic load tests are recommended to analyze the deformation and slippage rates of the systems.

Conclusion

Tibial hybrid fixation for ACL reconstruction in an animal model has biomechanical advantages over simple fixation with an interference screw or post in the immediate postoperative period.

Conflitos de Interesse Os autores declaram não haver conflitos de interesse.

Estudo realizado na Faculdade Evangélica do Paraná (FEPAR), e na Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná (UTFPR), Curitiba, PR, Brasil.

Study developed at Faculdade Evangélica do Paraná (FEPAR) and Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná (UTFPR), Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil.

Referências

- 1.Fu F H, Bennett C H, Lattermann C, Ma C B. Current trends in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Part 1: Biology and biomechanics of reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(06):821–830. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270062501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders T L, Maradit Kremers H, Bryan A J et al. Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears and Reconstruction: A 21-Year Population-Based Study. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(06):1502–1507. doi: 10.1177/0363546516629944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majewski M, Susanne H, Klaus S. Epidemiology of athletic knee injuries: A 10-year study. Knee. 2006;13(03):184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astur D C, Xerez M, Rozas J, Debieux P V, Franciozi C E, Cohen M. Lesões do ligamento cruzado anterior e do menisco no esporte: incidência, tempo de prática até a lesão e limitações causadas pelo trauma. Rev Bras Ortop. 2016;51(06):652–656. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domnick C, Raschke M J, Herbort M. Biomechanics of the anterior cruciate ligament: Physiology, rupture and reconstruction techniques. World J Orthop. 2016;7(02):82–93. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i2.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Wall M, Scholes C J, Patel S, Coolican M RJ, Parker D A. Tibial fixation in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective randomized study comparing metal interference screw and staples with a centrally placed polyethylene screw and sheath. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(09):1858–1864. doi: 10.1177/0363546511406234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steiner M E, Hecker A T, Brown C H, Jr, Hayes W C.Anterior cruciate ligament graft fixation. Comparison of hamstring and patellar tendon grafts Am J Sports Med 19942202240–246., discussion 246–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheffler S U, Südkamp N P, Göckenjan A, Hoffmann R FG, Weiler A. Biomechanical comparison of hamstring and patellar tendon graft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction techniques: The impact of fixation level and fixation method under cyclic loading. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(03):304–315. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.30609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brand J, Jr, Weiler A, Caborn D N, Brown C H, Jr, Johnson D L. Graft fixation in cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(05):761–774. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280052501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prado M, Martín-Castilla B, Espejo-Reina A, Serrano-Fernández J M, Pérez-Blanca A, Ezquerro F. Close-looped graft suturing improves mechanical properties of interference screw fixation in ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(02):476–484. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-1975-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodeo S A, Arnoczky S P, Torzilli P A, Hidaka C, Warren R F. Tendon-healing in a bone tunnel. A biomechanical and histological study in the dog. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(12):1795–1803. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199312000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eguchi A, Ochi M, Adachi N, Deie M, Nakamae A, Usman M A. Mechanical properties of suspensory fixation devices for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: comparison of the fixed-length loop device versus the adjustable-length loop device. Knee. 2014;21(03):743–748. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kousa P, Järvinen T LN, Vihavainen M, Kannus P, Järvinen M. The fixation strength of six hamstring tendon graft fixation devices in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Part II: tibial site. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(02):182–188. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310020501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tetsumura S, Fujita A, Nakajima M, Abe M. Biomechanical comparison of different fixation methods on the tibial side in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a biomechanical study in porcine tibial bone. J Orthop Sci. 2006;11(03):278–282. doi: 10.1007/s00776-006-1016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J J, Otarodifard K, Jun B J, McGarry M H, Hatch G F, III, Lee T Q. Is supplementary fixation necessary in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions? Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(02):360–365. doi: 10.1177/0363546510390434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stieven Filho E, Malafaia O, Ribas-Filho J M et al. [Biomechanic analysis of the sewed tendons for the reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament] Rev Col Bras Cir. 2010;37(01):52–57. doi: 10.1590/s0100-69912010000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woo S L, Hollis J M, Adams D J, Lyon R M, Takai S. Tensile properties of the human femur-anterior cruciate ligament-tibia complex. The effects of specimen age and orientation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(03):217–225. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scannell B P, Loeffler B J, Hoenig M et al. Biomechanical comparison of hamstring tendon fixation devices for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Part 2. Four tibial devices. Am J Orthop. 2015;44(02):82–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trump M, Palathinkal D M, Beaupre L, Otto D, Leung P, Amirfazli A. In vitro biomechanical testing of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: traditional versus physiologically relevant load analysis. Knee. 2011;18(03):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aga C, Rasmussen M T, Smith S D et al. Biomechanical comparison of interference screws and combination screw and sheath devices for soft tissue anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on the tibial side. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(04):841–848. doi: 10.1177/0363546512474968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donahue T L, Gregersen C, Hull M L, Howell S M. Comparison of viscoelastic, structural, and material properties of double-looped anterior cruciate ligament grafts made from bovine digital extensor and human hamstring tendons. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123(02):162–169. doi: 10.1115/1.1351889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagarkatti D G, McKeon B P, Donahue B S, Fulkerson J P. Mechanical evaluation of a soft tissue interference screw in free tendon anterior cruciate ligament graft fixation. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(01):67–71. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290011601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fabbriciani C, Mulas P D, Ziranu F, Deriu L, Zarelli D, Milano G. Mechanical analysis of fixation methods for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring tendon graft. An experimental study in sheep knees. Knee. 2005;12(02):135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zantop T, Weimann A, Rümmler M, Hassenpflug J, Petersen W. Initial fixation strength of two bioabsorbable pins for the fixation of hamstring grafts compared to interference screw fixation: single cycle and cyclic loading. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(03):641–649. doi: 10.1177/0095399703258616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giurea M, Zorilla P, Amis A A, Aichroth P. Comparative pull-out and cyclic-loading strength tests of anchorage of hamstring tendon grafts in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(05):621–625. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270051301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]