Abstract

Viruses must navigate the complex endomembranous network of the host cell to cause infection. In the case of a non-enveloped virus that lacks a surrounding lipid bilayer, endocytic uptake from the plasma membrane is not sufficient to cause infection. Instead, the virus must travel within organelle membranes to reach a specific cellular destination that supports exposure or arrival of the virus to the cytosol. This is achieved by viral penetration across a host endomembrane, ultimately enabling entry of the virus into the nucleus to initiate infection. In this review, we discuss the entry mechanisms of three distinct non-enveloped DNA viruses—adenovirus (AdV), human papillomavirus (HPV), and polyomavirus (PyV)—highlighting how each exploit different intracellular transport machineries and membrane penetration apparatus associated with the endosome, Golgi, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane systems to infect a host cell. These processes not only illuminate a highly-coordinated interplay between non-enveloped viruses and their host, but may provide new strategies to combat non-enveloped virus-induced diseases.

1. Introduction

To cause infection, a virus typically binds to a receptor displayed on the surface of the host cell (Helenius, 2018; Mercer et al., 2010). This engagement triggers receptor-mediated endocytosis, initiating a complex journey for the viral particle through the highly inter-connected cellular endomembrane network (Staring et al., 2018). Transport via this network, which includes the endosome, lysosome, Golgi, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER), can lead to either non-productive or productive infection. In a non-productive infection, the virus is delivered to an organelle where it is either trapped or becomes degraded by a protease. By contrast, for productive infection to take place, the virus instead must be directed down a pathway that enables it to penetrate a membrane barrier so that it can reach the cytosol or the nucleus, which is essential for successful infection (Greber, 2016). The strategies devised by viruses as they exploit the myriad of host intracellular transport machineries and membrane penetration apparatus to promote infection, which are unique and vary widely, are often dependent on the physical properties of the viral particle.

One critical property of a virus that governs its productive entry route is the presence or absence of a lipid bilayer surrounding the viral particle. A virus encased within a lipid bilayer is called an enveloped virus, while a virus lacking this bilayer is called a non-enveloped virus. An enveloped virus, such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Melikyan, 2014) or influenza virus (Smrt and Lorieau, 2017), penetrates at either the plasma membrane or the endosome membrane of the host. Membrane penetration is accomplished when the viral and host membrane fuse, thereby delivering the core viral particle into the cytosol to promote infection (Skehel and Wiley, 2000; Weissenhorn et al., 1999).

By contrast, as a lipid bilayer does not surround a non-enveloped virus, its membrane penetration mechanism must be fundamentally distinct from an enveloped virus. Although the precise molecular basis by which a non-enveloped virus penetrates a host membrane remains enigmatic, a more coherent understanding of this process is emerging (Kumar et al., 2018; Moyer and Nemerow, 2011; Tsai, 2007). The first step is delivery of the viral particle to the membrane penetration site. For a virus that penetrates the plasma membrane, no intracellular transport is required as virus recruitment to the host cell surface from the extracellular milieu is sufficient. However, for a virus that penetrates an intracellular membrane such as the endosome, Golgi, or ER membrane, it must co-opt intracellular transport machineries to reach these compartments. Next, upon reaching the specific membrane penetration site, cellular cues such as low pH, receptors, proteases, or chaperones, confer critical conformational changes to the virus (Yamauchi and Greber, 2016). This results in formation of a hydrophobic viral intermediate capable of penetrating the limiting membrane. Alternatively, the host-induced structural alterations may trigger the release of a viral lytic factor previously hidden in the native virion. This lytic factor in turn binds to and compromises the integrity of the host membrane, thereby allowing the remaining core viral particle to undergo membrane penetration. In some instances, these host-induced conformational changes may be initiated prior to the virus arriving to the membrane penetration site. In the third and final step, depending on the specific penetration site, cytosolic or nuclear components are recruited to extract the virus into the cytosol or nucleus to complete the penetration process.

We focus this review on clarifying the molecular entry mechanisms of three different non-enveloped DNA viruses—adenovirus (AdV), human papillomavirus (HPV), and polyomavirus (PyV). These viruses are highlighted because they illustrate how distinct intracellular transport machineries and membrane penetration apparatus linked to the endosome, Golgi, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes can be exploited to promote infection.

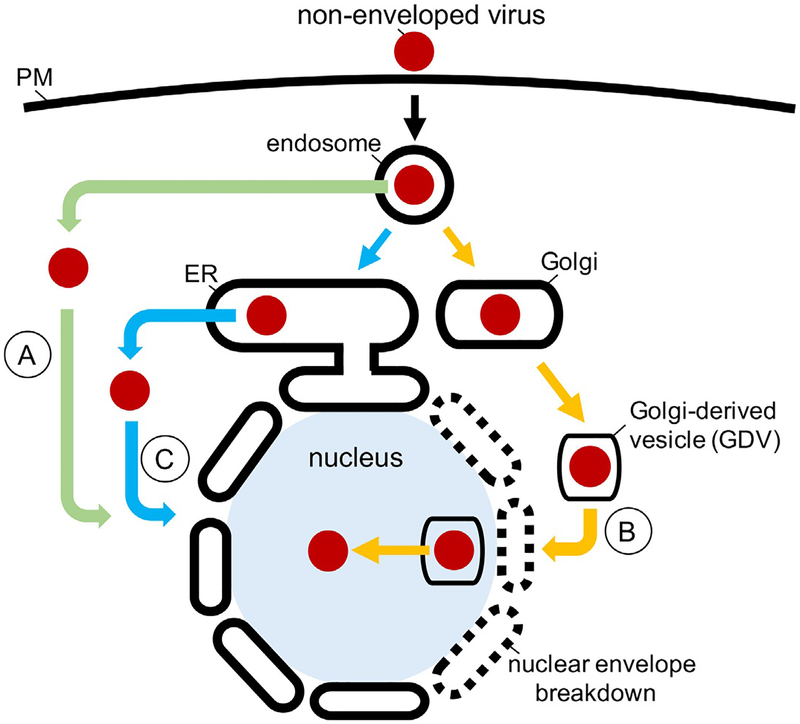

Specifically, post-endocytosis, AdV traffics to the endosome and relies on cues largely within this compartment to penetrate the endosome membrane in order to reach the cytosol (Fig. 1, green arrows); from the cytosol, the virus is delivered to the nucleus to cause infection. By contrast, HPV membrane penetration occurs in two steps (Fig. 1, orange arrows). Following entry to the endosome, HPV first initiates membrane penetration by partially inserting across the endosomal membrane. With a portion of the virus exposed to the cytosol, HPV is further targeted to the Golgi apparatus. During mitosis, Golgi membrane fragmentation generates Golgi-derived vesicles (GDVs) harboring HPV. These GDVs in turn gain access to the nucleus due to nuclear envelope breakdown at the onset of mitosis. Within the nucleus, HPV completes membrane penetration across the GDV membrane, fully depositing the viral particle into the nucleoplasm to enable infection. Yet a different journey is experienced by PyV. After reaching the endosome from the cell surface, PyV targets directly to the ER, bypassing the Golgi (Fig. 1, blue arrows). From the ER lumen, PyV crosses the ER membrane to reach the cytosol where it mobilizes further to the nucleus to trigger infection. By emphasizing cell entry of AdV, HPV, and PyV, this review reveals the diversity of mechanisms used by non-enveloped viruses during infectious entry.

Fig. 1.

Cellular entry of AdV, HPV, and PyV. (A) To infect cells, AdV traffics from the plasma membrane (PM) to the endosome where it penetrates the endosome membrane to reach the cytosol (green arrows); from the cytosol, the virus mobilizes to the nucleus to promote infection. (B) HPV infects cells by reaching the endosome where it initiates partial membrane penetration, exposing a segment of its viral protein to the cytosol. The membrane-inserted virus then sorts to the Golgi (orange arrow). Golgi membrane fragmentation during mitosis forms Golgi-derived vesicles (GDVs) containing HPV, which enter the nucleus when the nuclear envelope breaks down at the onset of mitosis. Upon complete translocation of the virus across the GDV membrane, HPV is deposited into the nucleoplasm to initiate infection. (C) After reaching the endosome from the PM, PyV is targeted to the ER from where it penetrates the ER membrane to gain entry into the cytosol (blue arrows). The virus is further transported to the nucleus to trigger infection.

2. Co-opting the endosome membrane system during cell entry of Adv

Although human AdV is responsible for mild respiratory and gastrointestinal infections, it can also cause life-threatening diseases in immunocompromised individuals (Lion, 2014). Paradoxically, modified forms of AdV are actively being explored as oncolytic agents, as well as vectors in gene transfer and vaccine delivery experiments, in combating different human diseases (Pascual-Pasto et al., 2019; Sayedahmed et al., 2018). Thus, clarifying AdV cell entry not only directly impacts our understanding of AdV-induced diseases, but has potential therapeutic implications for other diseases.

2.1. Receptor-mediated entry to the endosome

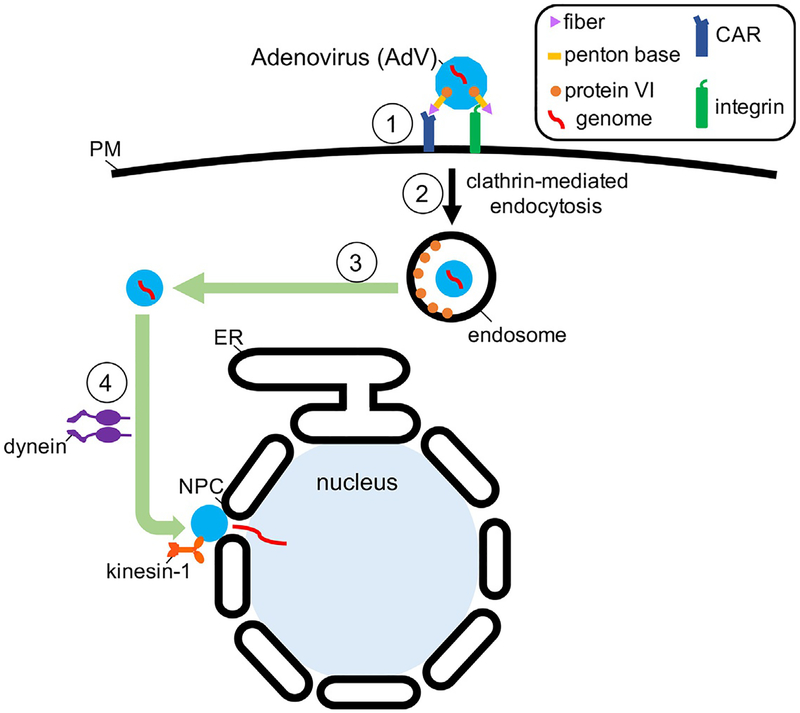

To date, there are at least 60 types of AdV. Structurally, AdV measures 90nm in diameter and harbors a 36-kilobase-pair double-stranded DNA genome. Thirteen structural proteins are encoded by its genome. When properly assembled, the viral particle displays 12 defined vertices, with each vertex composed of 2 distinct viral proteins—fiber, which binds to the host attachment receptor (van Raaij et al., 1999), and penton base, which interacts with the host internalization receptor (Zubieta et al., 2005). The primary host attachment receptor is the Coxsackie and Adenovirus Receptor (CAR) (Bergelson et al., 1997), although for some subtypes of AdV, the transmembrane proteins desmosomal desmoglein-2 (Wang et al., 2011) and CD46 of the complement system (Gaggar et al., 2003) can act in this capacity. Atomic-resolution of the protein-protein contact sites between fiber and CAR (Seiradake et al., 2006), or with CD46 (Cupelli et al., 2010), have been identified. Functionally, these attachment receptors serve to recruit the viral particles from the extracellular milieu to the plasma membrane of the host cell (Fig. 2, step 1).

Fig. 2.

Co-opting the endosome membrane system during cell entry of AdV. AdV entry is initiated when it binds to the CAR attachment receptor via the viral protein called fiber (step 1), followed by interaction with the integrin internalization receptor through the penton base viral protein. This engagement promotes clathrin-mediated endocytosis (step 2), delivering the virus to the endosome. In the endosome, protein VI is released from the virus. Protein VI then binds to and ruptures the endosome membrane, depositing the core viral particle in the cytosol (step 3). Cytosol-localized virus is targeted to the NPC by the dynein motor; here, the kinesin-1 motor pulls on the virus and disrupts the integrity of the viral structure and NPC, enabling the released viral genome to enter the nucleus.

Post-recruitment, AdV engages αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrin, which act as internalization receptors via interaction with the penton base of the virus (Wickham et al., 1993). Not surprisingly, given their roles as internalization receptors, integrins promote endocytosis of AdV. However, prior to virus internalization, coincident engagement of a single AdV particle with both CAR and an integrin receptor at the cell surface can initiate viral disassembly. This is thought to occur because integrins remain stationary within the lipid bilayer of the plasma membrane, while CAR experiences local drifting (Burckhardt et al., 2011). Hence, mechanical tension is generated and imparted on the virus when it binds simultaneously to these receptors (Burckhardt et al., 2011). This force begins the virus disassembly process and primes the virus for additional uncoating when it reaches the endosome, a step essential in virus penetration across the endosome membrane.

AdV internalization occurs through the classic receptor-mediated, clathrin-dependent pathway, delivering the virus to the endosome (Fig. 2, step 2) (Wang et al., 1998). However, there is also evidence that caveolae-mediated endocytosis (Yousuf et al., 2013) and non-selective macropinocytosis (Amstutz et al., 2008) can serve as alternative routes for AdV internalization. Cell-type differences between these experiments likely account for the varied endocytic pathways. Indeed, the ability to exploit different endocytic machineries is a common theme observed during entry of numerous non-enveloped viruses, including reovirus (Schulz et al., 2012), rotavirus (Gutierrez et al., 2010), and parvovirus (Boisvert et al., 2010).

2.2. Membrane penetration

Upon reaching the endosome, AdV is thought to gain access to the cytosol by penetrating the endosome membrane (Fig. 2, step 3). This idea is based on early negative-stain electron microscopy (EM) and fluorescence imaging studies (Greber et al., 1993; Morgan et al., 1969). In addition to these descriptive reports, functional analyses using inhibitors of endosomal acidification supported this idea (FitzGerald et al., 1983). However, one caveat is that although perturbing endosomal pH by a chemical inhibitor can disrupt appearance of AdV in the cytosol (Seth et al., 1984), this effect might in fact result from a block in the initial internalization of the virus before it reaches the endosome (Perez and Carrasco, 1994).

A more definitive understanding regarding the role of endosome membrane penetration during AdV entry was revealed when the viral lytic factor responsible for compromising the endosome membrane was identified. Specifically, in vitro biochemical and cell-based analyses demonstrated that the AdV protein VI, via its N-terminal amphipathic helix, is responsible for disruption of the endosome membrane (Maier et al., 2010; Wiethoff et al., 2005). High-resolution structural studies suggested that protein VI is normally hidden inside the virus where it acts to stabilize the peripentonal hexon and hexon interactions important for maintaining the overall virus architecture (Reddy and Nemerow, 2014). Hence, to release protein VI from AdV requires significant viral disassembly within the endosome (Nguyen et al., 2010), a process that may be triggered by the low pH of this compartment. Mechanistically, upon release from the virus, protein VI is believed to fragment the endosome membrane by binding to and inducing positive curvature to the lipid bilayer (Maier and Wiethoff, 2010), resulting in membrane rupture. In fact, AdV-induced membrane rupture can allow a 70kDa soluble marker to gain access into the cytosol (Prchla et al., 1995).

While other non-enveloped viruses also penetrate the endosome membrane, the AdV membrane penetration mechanism is fundamentally different to the one experienced by parvovirus. In this case, the virus uses the lipolytic enzyme phospholipase A2 (located at the N-terminus of its VP1 coat protein) in order to modify the endosome membrane (Farr et al., 2005). This triggers transient changes to the physical property of the lipid bilayer without imposing permanent damage so that a subviral complex can successfully breach the membrane (Suikkanen et al., 2003b). Similarly, reovirus releases a lytic factor (called μ1N) that interacts with the endosome membrane (Chandran et al., 2002) to induce specific size-selective pores in the membrane without inflicting significant damage. This allows the virus to penetrate this membrane and access the cytosol (Agosto et al., 2006; Ivanovic et al., 2008). Thus, although the endosome is a common site for membrane penetration of many non-enveloped viruses, the precise mechanism deployed to transport across this membrane barrier is vastly different.

2.3. Nuclear import

After endosome membrane fragmentation, the core AdV particle is deposited in the cytosol. Cytosol-localized AdV in turn engages the microtubule minus-end directed cytoplasmic dynein motor (hereafter called dynein) to transport to the nuclear pore complex (NPC) before entering the nucleus (Fig. 2, step 4) (Bremner et al., 2009). This directed movement can be countered by an unidentified motor (Suomalainen et al., 1999). Regardless, when AdV reaches the NPC, it docks to the NPC via interaction with the cytoplasmic filament Nup214 of the NPC (Trotman et al., 2001). The microtubule positive-end directed motor kinesin-1 is then recruited to the virus, pulling it away from the nucleus. This movement generates a mechanical force that simultaneously disassembles the virus to promote genome release and compromises the integrity of the NPC. These events enable the released viral genome to gain entry into the nucleus. Thus, generation of mechanical forces is important at both “ends” of productive AdV infection: prior to endocytosis and before nuclear entry. As dynein is also implicated in the delivery of cytosol-localized parvovirus (Suikkanen et al., 2003a) and likely reovirus (Mainou et al., 2013) into the nucleus post endosome escape, co-opting the cargo-transport function of dynein may be a shared strategy used by non-enveloped viruses to complete the last phase of productive infection.

3. Hijacking the dual endosome-Golgi membrane systems during HPV cell entry

Although HPV also exploits elements of the endosome during entry, a striking distinction is that this non-enveloped virus couples machineries associated with both the endosome and Golgi membrane systems to promote infection. HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States (Satterwhite et al., 2013) and high-risk HPV types are the primary cause of cervical, anogenital, and oropharyngeal cancers (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). Prophylactic vaccines against HPV are available; however, vaccine uptake is low (Walker et al., 2018) and the annual number of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers continues to rise (Van Dyne et al., 2018). There is no cure for HPV infection and despite its significant impact on human health, there is limited understanding of its cellular entry mechanism.

3.1. Cell-surface binding and entry to the endosome

To date, there are over 200 types of HPV (Muhr et al., 2018). Structurally, HPV is composed of the L1 and L2 capsid proteins. The L1 major capsid protein forms an icosahedral outer shell of 72 pentamers. Harbored within the L1 pentamers is the L2 minor coat protein. These viral proteins encapsulate an 8-kilobase-pair, double-stranded DNA genome (Buck et al., 2008). The viral genome encodes eight genes, some of which are necessary for cellular transformation (Doorbar, 2005).

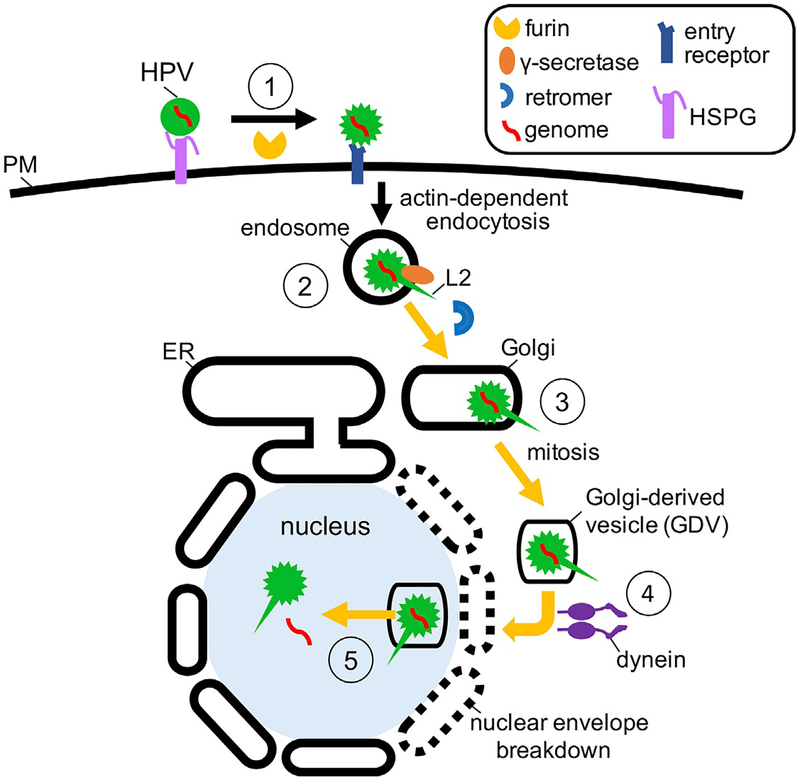

Through miniscule wounds or abrasions, HPV infects the basal epithelial cells of cutaneous and mucosal tissues (Doorbar, 2005). To initiate infection, L1 directly binds to heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) expressed at the surface of the host cell (Giroglou et al., 2001; Richards et al., 2013). Following HSPG binding, L1 is cleaved by the serine protease KLK8, and L2 interacts with the peptidylprolyl isomerase cyclophilin B (Bienkowska-Haba et al., 2009; Cerqueira et al., 2015). These steps result in exposure of L2 to the capsid surface, revealing a furin cleavage site at its N-terminus (Richards et al., 2006). While extracellular furin cleavage of L2 does not appear to be immediately essential for cell-surface events, it is required to engage factors important at later steps of viral entry (Richards et al., 2006). Ultimately, the conformational changes of the viral capsid allow for transfer to an unknown entry receptor at the plasma membrane (Fig. 3, step 1) (Day et al., 2008; Selinka et al., 2007). The identity of the entry receptor and mode of endocytosis remains a point of contention. Numerous putative factors are thought to support cellular uptake of HPV, including integrins α6 and β4, as well as tetraspanins CD63 and CD151 (Aksoy et al., 2014; Evander et al., 1997; Scheffer et al., 2013; Spoden et al., 2008). Annexin A2 and epidermal growth factor receptors have also been implicated in viral entry, though their contributions are less clear (Dziduszko and Ozbun, 2013; Surviladze et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2018).

Fig. 3.

Hijacking the dual endosome-Golgi membrane systems during HPV cell entry. To initiate infection, HPV attaches to HSPGs on the cell surface, resulting in conformational changes to the virus that enable furin-cleavage of L2 and subsequent transfer of the virus to an unknown entry receptor (step 1). The virus is then endocytosed by an actin-dependent mechanism to reach the endosome. As the endosome matures, the viral capsid proteins dissociate in a pH-dependent manner, and L2 engages γ-secretase. The C-terminus of L2 is then inserted across the endosomal membrane by γ-secretase, with the N-terminus remaining complexed to the viral DNA within the endosomal lumen (step 2). From here, the cytosolic portion of L2 engages retromer, and the virus is trafficked to the Golgi apparatus (step 3). Golgi fragmentation during mitosis generates HPV-harboring vesicles, which are thought to undergo dynein-mediated transport toward the nucleus (step 4). With the concomitant breakdown of the nuclear envelope during mitosis, the HPV-harboring vesicles enter the nucleus, where they remain intact until completion of mitosis and nuclear envelope reformation. Through an unknown mechanism, the viral genome is exposed to the nucleoplasm, and viral replication ensues (step 5).

Further complicating the process, emerging evidence suggests that endocytosis of HPV is independent of clathrin-, caveolin-, cholesterol-, or dynamin-mediated endocytic mechanisms (Schelhaas et al., 2012; Spoden et al., 2013). Rather, HPV internalization appears to be guided by an actin-dependent mechanism related to macropinocytosis. In vitro, endocytosis of HPV occurs in a highly asynchronous fashion, with virions continually internalized from 2 to 20h after addition of virus to cell culture (Schelhaas et al., 2012). This asynchronicity may be a result of the multiple conformational changes and extracellular processing events required for HPV entry. In addition, this asynchronicity suggests the presence of a secondary entry receptor as a limiting factor of viral uptake.

3.2. Membrane penetration

Upon internalization, HPV is delivered to the endosome. As the endosome matures and acidifies, L1 and L2 begin to dissociate in a pH-dependent manner (Smith et al., 2008). Proper dissociation and early endocytic trafficking of the virus also appears to involve cyclophilin B (Bienkowska-Haba et al., 2012), tetraspanin CD63, syntenin-1, and the ESCRT protein ALIX (Grassel et al., 2016), as well as interaction with sorting nexin 17 (Bergant Marusic et al., 2012). The extent to which L1-L2 disassembles at the endosome is unclear, as emerging evidence suggests that a subset of L1 remains associated with L2 and the viral genome through later trafficking steps (DiGiuseppe et al., 2017).

Similar to AdV, initial membrane penetration of HPV to the cytosol occurs at the endosomal membrane. However, HPV differs in that while it exposes the C-terminal portion of its L2 capsid protein to the cytosol, its N-terminal portion remains complexed to the viral DNA within the endosomal lumen (Fig. 3, step 2) (DiGiuseppe et al., 2015; Kamper et al., 2006). To achieve this topology, L2 must physically insert into the endosomal membrane. Although this topology is in principle possible because L2 contains a membrane-penetrating peptide and a transmembrane-like domain, how L2 is inserted into the endosomal membrane remains largely mysterious (Bronnimann et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2018).

A clue to this enigma was recently revealed when the transmembrane protease γ-secretase was shown to act as a chaperone, promoting insertion of L2 into the endosomal membrane in a pH-dependent manner (Inoue et al., 2018). Proper membrane insertion of L2 by γ-secretase is a critical step, as mutation of L2’s transmembrane-like domain, or of γ-secretase itself, terminates productive infection (Bronnimann et al., 2013; Inoue et al., 2018). The molecular basis by which γ-secretase promotes membrane penetration of L2 remains unclear. Despite the well-established proteolytic activity of this transmembrane protease, cleavage of L2 by γ-secretase is not required to promote HPV infection—only γ-secretase-induced membrane insertion of L2 is essential (Inoue et al., 2018). Thus, HPV appears to exploit a novel chaperone function of γ-secretase.

γ-secretase-dependent insertion of L2 is a decisive step of HPV infection, as it diverts the virus away from the non-productive lysosomal pathway and instead targets HPV along the productive route (Inoue et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2014). Specifically, with a portion of L2 now exposed to the cytosol, it engages the cytosolic retromer sorting complex (Lipovsky et al., 2013; Popa et al., 2015). Retromer normally functions to sort a cellular cargo from the endosome to the Golgi apparatus. HPV hijacks this retrograde transport function of the retromer, allowing for the endosome-localized virus to be delivered to the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 3, step 3) (Day et al., 2013; Popa et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2014). Upon reaching the Golgi, the viral DNA remains shielded from the cytosol within the Golgi lumen, with only L2 protruding into the cytosolic space.

3.3. Nuclear import

HPV remains in the Golgi until the onset of mitosis, when this organelle fragments to form Golgi-derived vesicles (GDVs) (Aydin et al., 2014; Champion et al., 2017). HPV takes advantage of Golgi fragmentation by budding off into GDVs, thus escaping the Golgi while still remaining protected within a membrane (Fig. 3, step 4) (DiGiuseppe et al., 2016). As mitosis progresses, the HPV-harboring vesicles are transported along the astral microtubules to the nuclear region, where the virus appears to colocalize with the centrosome (Calton et al., 2017; DiGiuseppe et al., 2016). This trafficking step is thought to involve dynein-mediated transport, though additional evidence is required to support this observation (Florin et al., 2006; Schneider et al., 2011).

With the concomitant nuclear envelope breakdown (NEB) during mitosis (Champion et al., 2017), the HPV-harboring vesicles gain entry to the nucleus (Aydin et al., 2014; Calton et al., 2017). In this manner, HPV accesses the nucleus without engaging the NPC, in contrast to AdV and PyV (see below). The virus-harboring vesicles associate with the condensed chromosomes of the host cell (Calton et al., 2017; DiGiuseppe et al., 2016). During this highly dynamic process, it is unclear how HPV anchors itself in the nucleus. One possibility is that the virus directly binds to the mitotic chromosomes through a chromatin binding domain on L2 (Aydin et al., 2017; Calton et al., 2017). Alternatively, L2 might actively target the viral DNA to promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies of the host cell (Day et al., 2004). As a third option, an unidentified nuclear host factor may help target and retain the viral complex at the nucleus during specific stages of mitosis. Though L2 appears to contain nuclear localization signals (NLSs) (Mamoor et al., 2012), the functional significance of these signals during infection remains to be addressed.

Upon completion of mitosis, when the nuclear envelope reforms, the HPV-harboring vesicle is effectively trapped within the nucleus (Calton et al., 2017, DiGiuseppe et al., 2016). How L2 and the viral genome fully translocate across the protective vesicular membrane into the nucleoplasm is entirely unknown (Fig. 3, step 5). In fact, the presence of cargo-transport vesicles within the nucleus is itself a unique phenomena, with no previously described examples.

What mechanism might translocate and expose the viral genome to the nucleoplasm? There is minimal evidence that nuclear phospholipases could play a role in degrading the vesicular membrane (Aydin et al., 2014; Lipovsky et al., 2013). Furthermore, whether L2 executes a function in exposing the viral DNA is not known. Coordinating nuclear entry and viral DNA translocation with mitotic NEB appears to be unique to HPV among non-enveloped viruses, though some enveloped viruses such as the murine-leukemia virus are known to rely on NEB as well (Cohen et al., 2011). Regardless, upon nuclear exposure of HPV’s genome, host cell machinery initiates viral transcription and replication, thereby promoting infection.

4. Exploiting the ER during cell entry of PyV

In contrast to AdV and HPV, by far the most unique feature of PyV cell entry is its reliance on ER-associated machineries. PyV infection is relatively common among the general population with a seroprevalence of up to 90% in some cases (DeCaprio and Garcea, 2013). PyVs cause debilitating disease in humans, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. These include neuropathy by BK PyV and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) by JC PyV. With the recent discovery of 11 new human PyVs, including Merkel cell PyV, which causes the oftenfatal Merkel cell skin carcinoma (Arora et al., 2012; DeCaprio and Garcea, 2013), the study of these small DNA tumor viruses is as essential as ever.

4.1. Receptor-mediated entry to the endosome

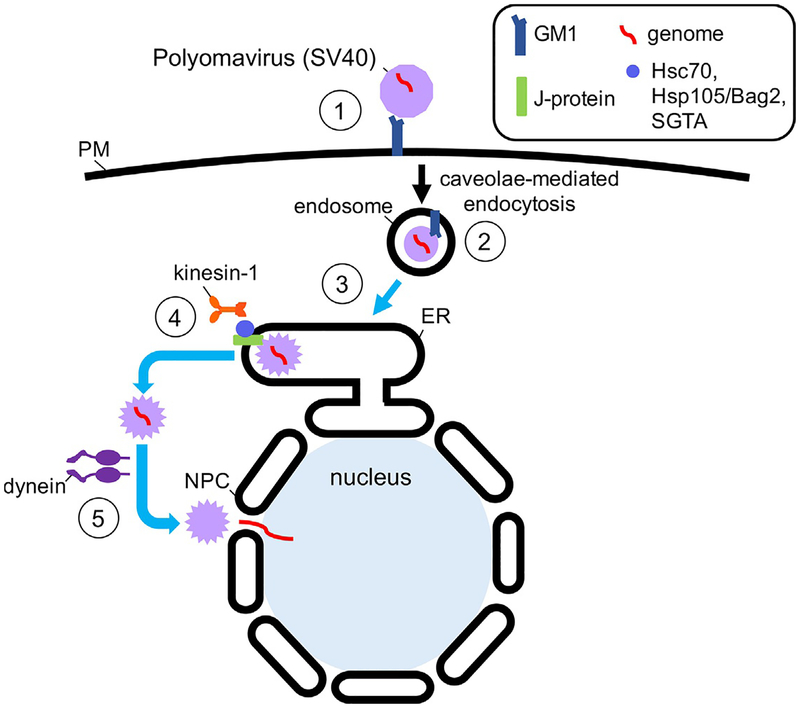

Historically, much of our knowledge on PyV was gained through the study of two animal viruses—the murine PyV and the simian virus 40 (SV40), the archetype PyV. In this chapter, we will discuss mainly the entry of SV40, which shares structural and genomic organization with human PyVs as well as the same infectious life cycle (Howley and Livingston, 2009). SV40 has a 5-kilobase-pair double-stranded DNA genome that is encased within an icosahedral capsid shell. The viral capsid is composed of 72 pentamers of the VP1 major capsid protein. Each pentamer is associated with one copy of either the VP2 or VP3 minor capsid proteins, which associate with the viral genome and contain an NLS (Chen et al., 1998; Liddington et al., 1991). When fully assembled, the virus is approximately 45nm in diameter.

To initiate viral entry, PyV attaches to a ganglioside glycolipid receptor on the host cell surface through its VP1 protein (Fig. 4, step 1). The exact receptor varies between PyVs, with SV40 associating with GM1, murine PyV binding GD1a and BK, and JC and Merkel cell PyVs interacting instead with either GD1b or GT1b (Erickson et al., 2009; Komagome et al., 2002; Low et al., 2006; Tsai et al., 2003). Following receptor binding, the virus is internalized by a caveolae/lipid-raft dependent mechanism and subsequently transported to the early endosome (Fig. 4, step 2) (Anderson et al., 1996). Endosomal maturation is essential for PyV entry as blocking maturation or acidification of the late endosome disrupts downstream steps of viral trafficking during entry (Qian et al., 2009).

Fig. 4.

Unique viral transport pathway through the ER during PyV entry. To infect cells, SV40 binds to the ganglioside GM1 receptor on the cell surface (step 1) and is endocytosed by a caveolae/lipid raft-dependent mechanism to reach the endosome (step 2). From here, the virus is targeted directly to the ER (step 3) where it undergoes conformational changes to penetrate the ER membrane and reach the cytosol (step 4). This requires the concerted effort of both ER resident proteins, a cytosolic chaperone complex, and the kinesin-1 motor. Once in the cytosol, the dynein motor transports SV40 to the nucleus where the viral genome enters through the NPC (step 5).

4.2. Membrane penetration of the ER membrane

Unlike AdV and HPV, the initial site of PyV membrane penetration is not at the endosomal membrane. Instead, virus-containing endosomes are sorted to the ER, at least in part, through the guidance of the ganglioside glycolipid receptor and in a microtubule-dependent fashion (Fig. 4, step 3) (Norkin et al., 2002; Pelkmans et al., 2001; Qian et al., 2009). The discovery that endocytosed SV40 bypasses the Golgi and is targeted directly from the endosome to the ER was the first evidence of this unique cellular transport route (Kartenbeck et al., 1989). At present, PyV is the only virus explicitly shown to utilize this pathway, although one study suggests that a subset of HPV may also transport through the ER during entry (Zhang et al., 2014).

PyV was initially thought to disguise itself as a misfolded substrate that hijacks the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway to reach the cytosol. This cellular quality control pathway ejects misfolded proteins from the ER into the cytosol through a Hrd1 E3 ubiquitin ligase-containing channel for degradation by the proteasome (Tsai et al., 2002). Entry of SV40, however, is Hrd1-independent and avoids ubiquitination (Geiger et al., 2011). Further, because SV40 crosses the ER membrane as a relatively large particle (45nm) that is unlikely to move through the pore of any known channel (Inoue and Tsai, 2011), a new model has emerged in which the virus reorganizes the ER membrane to create a membrane penetration site. In support of this model, SV40 infection induces mobilization of the BAP31 ER membrane protein as well as the transmembrane DNA J-proteins B12, B14, and C18 into discrete puncta called “foci” (Bagchi et al., 2015; Geiger et al., 2011; Goodwin et al., 2011; Walczak et al., 2014). This virus-induced transmembrane complex recruits a cytosolic chaperone complex composed of Hsc70, Hsp105, Bag2, and SGTA to the foci, which then extracts the virus into the cytosol (Fig. 4, step 4) (Dupzyk and Tsai, 2018; Dupzyk et al., 2017; Ravindran et al., 2015; Walczak et al., 2014). A more detailed review of this extraction process can be found in Dupzyk and Tsai (2016). The architectural structure of the foci as well as how SV40 induces its formation is not completely understood; however, recent studies show that this process relies on both the ER membrane protein complex 1 (EMC1) and the kinesin-1 molecular motor (Bagchi et al., 2016; Ravindran et al., 2017). It is likely that future research will reveal other ER-associated proteins involved in coordinating this virus-specific phenomenon.

In addition to being its site of membrane penetration, transport through the ER is essential to PyV infection as ER luminal proteins impart conformational changes on the virus that are essential for subsequent steps of the membrane transport pathway. Several members of the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family of ER luminal proteins induce structural rearrangement of the virus by reducing VP1 inter-pentameric disulfide bonds in the capsid shell (Schelhaas et al., 2007; Walczak and Tsai, 2011). This reduction is required for productive infection as it exposes the underlying hydrophobic VP2 and VP3 proteins to generate a viral particle that is primed and competent for membrane penetration (Magnuson et al., 2005; Norkin et al., 2002). This initial exposure of VP2 and VP3 may also be the first step in disassembly of the viral capsid in the cytosol.

4.3. Nuclear import

Upon reaching the cytosol, two major steps still stand between PyV and successful infection—physical transport to the nucleus and capsid disassembly to expose the viral genome (Inoue and Tsai, 2011). Similar to other non-enveloped viruses, SV40 engages the dynein motor when the virus arrives in the cytosol, which is essential for nuclear entry of the virus (Fig. 4, step 5) (Ravindran et al., 2018). This interaction is likely important for transporting the viral particle to the nucleus, as inhibiting the motor’s ATPase motor domain significantly impaired infection. How the virus is handed off from kinesin-1 to dynein after ER membrane penetration has not been established, and is a point of interest in the field. In addition to its role in transport, inhibiting dynein activity also impairs viral disassembly in the cytosol. We envision that, similar to AdV, dynein movement generates a mechanical force that physically disassembles the capsid shell to expose the viral genome. Alternatively, dynein may instead transport PyV to a secondary site where disassembly occurs by an unknown mechanism. In either case, viral disassembly is a rate-limiting step in PyV entry.

While PyV nuclear entry has not been fully characterized, evidence indicates that it also gains access to the nucleus through the NPC. Cytoplasmic injection of mAB414, an anti-nucleoporin antibody that blocks entry of signal-mediated nuclear proteins, inhibits the nuclear expression of the viral large T-antigen (TAg), a marker of successful nuclear entry (Clever et al., 1991; Yamada and Kasamatsu, 1993). Moreover, SV40 VP3 was reported to bind to components of the nuclear import machinery, including importin α/β (Nakanishi et al., 2002), which transport cargos with an NLS through the NPC (Lange et al., 2007). Interestingly, the first NLS was discovered in SV40 (Kalderon et al., 1984), and as VP2 and VP3 each contain this signal, it is possible that these minor capsid proteins remain associated with viral DNA after disassembly in order to direct the genome into the nucleus.

Finally, a proteomics approach using an immunoprecipitation-coupled mass spectrometry strategy identified several NPC components as interacting partners of cytosol-localized SV40, including the cytoplasmic filament Nup358/RanBP2 (Ravindran et al., 2018). Intriguingly, RanBP2, which associates with Nup214 during AdV nuclear import, has also been implicated in the nuclear import of enveloped viruses such as vaccinia virus and HIV (Hutten et al., 2009; Khuperkar et al., 2017). Therefore, while the entry pathways of different DNA viruses can take them along unique journeys through the cell, many of these routes appear to converge at their final destination for nuclear entry.

5. Conclusion and future directions

In order to cause infection, viruses must navigate the complex intracellular environment of their host cells to reach the cytosol or nucleus where replication occurs. In the case of non-enveloped DNA viruses, such as AdV, HPV and PyV, this infectious route can vary greatly. Prior to reaching the nucleus, their ultimate destination during entry, these viruses must first successfully penetrate a host membrane. Whether this occurs at the endosome, as seen with AdV and HPV, or at the ER membrane, as seen with PyV, membrane penetration remains a decisive step in productive infection.

The study of how non-enveloped viruses co-opt cellular membrane penetration apparatus and transport machineries has revealed much about how these viruses infect cells, but several questions remain. For instance, what precise structural changes are imparted on AdV that enables release of protein VI, and how might low pH be involved in this process? Regarding HPV, identifying the mysterious viral entry receptor is of foremost importance. Pinpointing this essential host factor will clarify the mode of HPV endocytosis and reveal a novel target for therapeutic development. In addition, resolving how this virus hijacks γ-secretase activity to promote penetration of the endosome membrane requires further research, as probing this phenomena will provide critical insights into the trafficking functions of both HPV and γ-secretase. Unlike other non-enveloped DNA viruses, HPV’s genome remains in a protective vesicle throughout nuclear entry. How the viral genome egresses from the transport vesicles into the nucleoplasm is perhaps the most intriguing question of HPV entry, yet remains largely unexplored. In the case of PyV, how this virus induces the construction of its own membrane penetration site is still a key question in the field. More specifically, how PyV signals to cellular factors, including kinesin-1, to mobilize into a virus-induced foci and whether this coordinates with membrane penetration are widely unknown. Additionally, identifying other host proteins involved in membrane penetration and the subsequent trafficking of PyV to the nucleus could provide new targets for combating infection.

The leveraging of both new and traditional techniques will be instrumental in addressing these outstanding questions. For instance, with increasing advances in high-resolution microscopy techniques, these state-of-the-art imaging approaches could be used to resolve the structure and formation of the PyV membrane penetration site. Along the same lines, these sophisticated methods may illuminate how γ-secretase mediates HPV insertion, as well as how the viral DNA translocates across the limiting membrane upon arrival in the nucleus. Because identifying additional host factors involved in viral entry is a criticial objective in clarifying the infection mechanisms of these non-enveloped viruses, ongoing proteomic advances may aid in this endeavor. For example, biotin-proximity labeling (BioID) can be used to screen for relevant protein-protein interactions, and if coupled with mass-spectrometry, may reveal even the most transient of associations (Kim et al., 2014, 2016). In addition to modern methods, however, the use of classical biochemical techniques is still very much needed. In particular, developing in vitro assays to reconstitute viral entry events will clarify the precise molecular mechanisms of these processes, which is imperative for answering these questions.

Even still, perhaps the greatest and most deliberated question remains. Why have these, and other non-enveloped viruses devised such different entry strategies to reach the nucleus to cause infection? It is even more puzzling when considering the variance in entry routes between types of the same virus. It is possible that while seemingly similar to us, the unique characteristics of each viral particle necessitate a selective path during entry: acidification in the endosome to reveal a hidden viral protein required for membrane penetration; ER luminal proteins to remodel the viral capsid for subsequent disassembly in the cytosol; or perhaps a Golgi-dependent action that has yet to be uncovered. While we can only speculate on the reasons, one thing that is certain is that after many years of viral evolution, these distinctions provide us the best clues to understanding and preventing virus infection and are only waiting to be discovered.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alex Kukreja (University of Michigan) for critically reviewing this article. C.C.S. is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (T32-AI007528). M.C.H. is supported by NIH (T32-GM007315). B.T. is funded by the NIH (RO1-AI064296).

References

- Agosto MA, Ivanovic T, Nibert ML, 2006. Mammalian reovirus, a nonfusogenic nonenveloped virus, forms size-selective pores in a model membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 103, 16496–16501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy P, Abban CY, Kiyashka E, Qiang W, Meneses PI, 2014. HPV16 infection of HaCaTs is dependent on beta4 integrin, and alpha6 integrin processing. Virology 449, 45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstutz B, Gastaldelli M, Kalin S, Imelli N, Boucke K, Wandeler E, Mercer J, Hemmi S, Greber UF, 2008. Subversion of CtBP1-controlled macropinocytosis by human adenovirus serotype 3. EMBO J. 27, 956–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson HA, Chen Y, Norkin LC, 1996. Bound simian virus 40 translocates to caveolin-enriched membrane domains, and its entry is inhibited by drugs that selectively disrupt caveolae. Mol. Biol. Cell 7, 1825–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora R, Chang Y, Moore PS, 2012. MCV and Merkel cell carcinoma: a molecular success story. Curr. Opin. Virol 2, 489–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin I, Weber S, Snijder B, Samperio Ventayol P, Kuhbacher A, Becker M, Day PM, Schiller JT, Kann M, Pelkmans L, Helenius A, Schelhaas M, 2014. Large scale RNAi reveals the requirement of nuclear envelope breakdown for nuclear import of human papillomaviruses. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin I, Villalonga-Planells R, Greune L, Bronnimann MP, Calton CM Becker M, Lai KY, Campos SK, Schmidt MA, Schelhaas M, 2017. A central region in the minor capsid protein of papillomaviruses facilitates viral genome tethering and membrane penetration for mitotic nuclear entry. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi P, Walczak CP, Tsai B, 2015. The endoplasmic reticulum membrane J protein C18 executes a distinct role in promoting simian virus 40 membrane penetration. J. Virol 89, 4058–4068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi P, Inoue T, Tsai B, 2016. EMC1-dependent stabilization drives membrane penetration of a partially destabilized non-enveloped virus. Elife 5, 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergant Marusic M, Ozbun MA, Campos SK, Myers MP, Banks L, 2012. Human papillomavirus L2 facilitates viral escape from late endosomes via sorting nexin 17. Traffic 13, 455–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergelson JM, Cunningham JA, Droguett G, Kurt-Jones EA, Krithivas A, Hong JS, Horwitz MS, Crowell RL, Finberg RW, 1997. Isolation of a common receptor for Coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science 275, 1320–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowska-Haba M, Patel HD, Sapp M, 2009. Target cell cyclophilins facilitate human papillomavirus type 16 infection. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowska-Haba M, Williams C, Kim SM, Garcea RL, Sapp M, 2012. Cyclophilins facilitate dissociation of the human papillomavirus type 16 capsid protein L1 from the L2/DNA complex following virus entry. J. Virol 86, 9875–9887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert M, Fernandes S, Tijssen P, 2010. Multiple pathways involved in porcine parvovirus cellular entry and trafficking toward the nucleus. J. Virol 84, 7782–7792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner KH, Scherer J, Yi J, Vershinin M, Gross SP, Vallee RB, 2009. Adenovirus transport via direct interaction of cytoplasmic dynein with the viral capsid hexon subunit. Cell Host Microbe 6, 523–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronnimann MP, Chapman JA, Park CK, Campos SK, 2013. A transmembrane domain and GxxxG motifs within L2 are essential for papillomavirus infection. J. Virol 87, 464–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck CB, Cheng N, Thompson CD, Lowy DR, Steven AC, Schiller JT, Trus BL, 2008. Arrangement of L2 within the papillomavirus capsid. J. Virol 82, 5190–5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt CJ, Suomalainen M, Schoenenberger P, Boucke K, Hemmi S, Greber UF, 2011. Drifting motions of the adenovirus receptor CAR and immobile integrins initiate virus uncoating and membrane lytic protein exposure. Cell Host Microbe 10, 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calton CM, Bronnimann MP, Manson AR, Li S, Chapman JA, Suarez-Berumen M, Williamson TR, Molugu SK, Bernal RA, Campos SK, 2017. Translocation of the papillomavirus L2/vDNA complex across the limiting membrane requires the onset of mitosis. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers For Disease Control And Prevention, 2018. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus, United States—2011–2015 USCS data brief, no. 4 Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira C, Samperio Ventayol P, Vogeley C, Schelhaas M, 2015. Kallikrein-8 proteolytically processes human papillomaviruses in the extracellular space To facilitate entry into host cells. J. Virol 89, 7038–7052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion L, Linder MI, Kutay U, 2017. Cellular reorganization during mitotic entry. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 26–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran K, Farsetta DL, Nibert ML, 2002. Strategy for nonenveloped virus entry: a hydrophobic conformer of the reovirus membrane penetration protein micro 1 mediates membrane disruption. J. Virol 76, 9920–9933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XS, Stehle T, Harrison SC, 1998. Interaction of polyomavirus internal protein VP2 with the major capsid protein VP1 and implications for participation of VP2 in viral entry. EMBO J. 17, 3233–3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clever J, Yamada M, Kasamatsu H, 1991. Import of simian virus 40 virions through nuclear pore complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 88, 7333–7337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Au S, Pante N, 2011. How viruses access the nucleus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 1634–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupelli K, Muller S, Persson BD, Jost M, Arnberg N, Stehle T, 2010. Structure of adenovirus type 21 knob in complex with CD46 reveals key differences in receptor contacts among species B adenoviruses. J. Virol 84, 3189–3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day PM, Baker CC, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, 2004. Establishment of papillomavirus infection is enhanced by promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 101, 14252–14257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day PM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, 2008. Heparan sulfate-independent cell binding and infection with furin-precleaved papillomavirus capsids. J. Virol 82, 12565–12568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day PM, Thompson CD, Schowalter RM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, 2013. Identification of a role for the trans-Golgi network in human papillomavirus 16 pseudovirus infection. J. Virol 87, 3862–3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCaprio JA, Garcea RL, 2013. A cornucopia of human polyomaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 11, 264–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiuseppe S, Keiffer TR, Bienkowska-Haba M, Luszczek W, Guion LG, Muller M, Sapp M, 2015. Topography of the human papillomavirus minor capsid protein L2 during vesicular trafficking of infectious entry. J. Virol 89, 10442–10452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiuseppe S, Luszczek W, Keiffer TR, Bienkowska-Haba M, Guion LG, Sapp MJ, 2016. Incoming human papillomavirus type 16 genome resides in a vesicular compartment throughout mitosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, 6289–6294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiuseppe S, Bienkowska-Haba M, Guion LGM, Keiffer TR, Sapp M, 2017. Human papillomavirus major capsid protein L1 remains associated with the incoming viral genome throughout the entry process. J. Virol 91 (16), 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorbar J, 2005. The papillomavirus life cycle. J. Clin. Virol 32 (Suppl. 1), S7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupzyk A, Tsai B, 2016. How polyomaviruses exploit the ERAD machinery to cause infection. Viruses 8, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupzyk A, Tsai B, 2018. Bag2 is a component of a cytosolic extraction machinery that promotes membrane penetration of a nonenveloped virus. J. Virol 92, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupzyk A, Williams JM, Bagchi P, Inoue T, Tsai B, 2017. SGTA-dependent regulation of Hsc70 promotes cytosol entry of simian virus 40 from the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Virol 91, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziduszko A, Ozbun MA, 2013. Annexin A2 and S100A10 regulate human papillomavirus type 16 entry and intracellular trafficking in human keratinocytes. J. Virol 87, 7502–7515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KD, Garcea RL, Tsai B, 2009. Ganglioside GT1b is a putative host cell receptor for the Merkel cell polyomavirus. J. Virol 83, 10275–10279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evander M, Frazer IH, Payne E, Qi YM, Hengst K, McMillan NA, 1997. Identification of the alpha6 integrin as a candidate receptor for papillomaviruses. J. Virol 71, 2449–2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr GA, Zhang LG, Tattersall P, 2005. Parvoviral virions deploy a capsid-tethered lipolytic enzyme to breach the endosomal membrane during cell entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 102, 17148–17153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald DJ, Padmanabhan R, Pastan I, Willingham MC, 1983. Adenovirusinduced release of epidermal growth factor and pseudomonas toxin into the cytosol of KB cells during receptor-mediated endocytosis. Cell 32, 607–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin L, Becker KA, Lambert C, Nowak T, Sapp C, Strand D, Streeck RE, Sapp M, 2006. Identification of a dynein interacting domain in the papillomavirus minor capsid protein l2. J. Virol 80, 6691–6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaggar A, Shayakhmetov DM, Lieber A, 2003. CD46 is a cellular receptor for group B adenoviruses. Nat. Med 9, 1408–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger R, Andritschke D, Friebe S, Herzog F, Luisoni S, Heger T, Helenius A 2011. BAP31 and BiP are essential for dislocation of SV40 from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. Nat. Cell Biol 13, 1305–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroglou T, Florin L, Schafer F, Streeck RE, Sapp M, 2001. Human papillomavirus infection requires cell surface heparan sulfate. J. Virol 75, 1565–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin EC, Lipovsky A, Inoue T, Magaldi TG, Edwards AP, Van Goor KE, Paton AW, Paton JC, Atwood WJ, Tsai B, Dimaio D, 2011. BiP and multiple DNAJ molecular chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum are required for efficient simian virus 40 infection. MBio 2, e00101–e00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassel L, Fast LA, Scheffer KD, Boukhallouk F, Spoden GA, Tenzer S, Boller K, Bago R, Rajesh S, Overduin M, Berditchevski F, Florin L, 2016. The CD63-Syntenin-1 Complex Controls Post-Endocytic Trafficking of Oncogenic Human Papillomaviruses. Sci. Rep 6, 32337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greber UF, 2016. Virus and host mechanics support membrane penetration and cell entry. J. Virol 90, 3802–3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greber UF, Willetts M, Webster P, Helenius A, 1993. Stepwise dismantling of adenovirus 2 during entry into cells. Cell 75, 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez M, Isa P, Sanchez-San Martin C, Perez-Vargas J, Espinosa R, Arias CF, Lopez S, 2010. Different rotavirus strains enter MA104 cells through different endocytic pathways: the role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Virol 84, 9161–9169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius A, 2018. Virus entry: looking back and moving forward. J. Mol. Biol 430, 1853–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howley PM, Livingston DM, 2009. Small DNA tumor viruses: large contributors to biomedical sciences. Virology 384, 256–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutten S, Walde S, Spillner C, Hauber J, Kehlenbach RH, 2009. The nuclear pore component Nup358 promotes transportin-dependent nuclear import. J. Cell Sci 122, 1100–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Tsai B, 2011. A large and intact viral particle penetrates the endoplasmic reticulum membrane to reach the cytosol. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Zhang P, Zhang W, Goodner-Bingham K, Dupzyk A, Dimaio D, Tsai B, 2018. gamma-Secretase promotes membrane insertion of the human papillomavirus L2 capsid protein during virus infection. J. Cell Biol 217, 3545–3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovic T, Agosto MA, Zhang L, Chandran K, Harrison SC, Nibert ML, 2008. Peptides released from reovirus outer capsid form membrane pores that recruit virus particles. EMBO J. 27, 1289–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalderon D, Roberts BL, Richardson WD, Smith AE, 1984. A short amino acid sequence able to specify nuclear location. Cell 39, 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamper N, Day PM, Nowak T, Selinka HC, Florin L, Bolscher J, Hilbig L, Schiller JT, Sapp M, 2006. A membrane-destabilizing peptide in capsid protein L2 is required for egress of papillomavirus genomes from endosomes. J. Virol 80, 759–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartenbeck J, Stukenbrok H, Helenius A, 1989. Endocytosis of simian virus 40 into the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol 109, 2721–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khuperkar D, Kamble A, Singh A, Ghate A, Nawadkar R, Sahu A, Joseph J, 2017. Selective recruitment of nucleoporins on vaccinia virus factories and the role of Nup358 in viral infection. Virology 512, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DI, Birendra KC, Zhu W, Motamedchaboki K, Doye V, Roux KJ, 2014. Probing nuclear pore complex architecture with proximity-dependent biotinylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, E2453–E2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DI, Jensen SC, Noble KA, Kc B, Roux KH, Motamedchaboki K, Roux KJ, 2016. An improved smaller biotin ligase for BioID proximity labeling. Mol. Biol. Cell 27, 1188–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komagome R, Sawa H, Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, Tanaka S, Atwood WJ, Nagashima K, 2002. Oligosaccharides as receptors for JC virus. J. Virol 76, 12992–13000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar CS, Dey D, Ghosh S, Banerjee M, 2018. Breach: host membrane penetration and entry by nonenveloped viruses. Trends Microbiol. 26, 525–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange A, Mills RE, Lange CJ, Stewart M, Devine SE, Corbett AH, 2007. Classical nuclear localization signals: definition, function, and interaction with importin alpha. J. Biol. Chem 282, 5101–5105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddington RC, Yan Y, Moulai J, Sahli R, Benjamin TL, Harrison SC, 1991. Structure of simian virus 40 at 3.8-A resolution. Nature 354, 278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lion T, 2014. Adenovirus infections in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 27, 441–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipovsky A, Popa A, Pimienta G, Wyler M, Bhan A, Kuruvilla L, Guie MA, Poffenberger AC, Nelson CD, Atwood WJ, Dimaio D, 2013. Genome-wide siRNA screen identifies the retromer as a cellular entry factor for human papillomavirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 7452–7457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low JA, Magnuson B, Tsai B, Imperiale MJ, 2006. Identification of gangliosides GD1b and GT1b as receptors for BK virus. J. Virol 80, 1361–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson B, Rainey EK, Benjamin T, Baryshev M, Mkrtchian S, Tsai B, 2005. ERp29 triggers a conformational change in polyomavirus to stimulate membrane binding. Mol. Cell 20, 289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier O, Wiethoff CM, 2010. N-terminal alpha-helix-independent membrane interactions facilitate adenovirus protein VI induction of membrane tubule formation. Virology 408, 31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier O, Galan DL, Wodrich H, Wiethoff CM, 2010. An N-terminal domain of adenovirus protein VI fragments membranes by inducing positive membrane curvature. Virology 402, 11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainou BA, Zamora PF, Ashbrook AW, Dorset DC, Kim KS, Dermody TS, 2013. Reovirus cell entry requires functional microtubules. MBio 4, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamoor S, Onder Z, Karanam B, Kwak K, Bordeaux J, Crosby L, Roden RB, Moroianu J, 2012. The high risk HPV16 L2 minor capsid protein has multiple transport signals that mediate its nucleocytoplasmic traffic. Virology 422, 413–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melikyan GB, 2014. HIV entry: a game of hide-and-fuse? Curr. Opin. Virol 4, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer J, Schelhaas M, Helenius A, 2010. Virus entry by endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem 79, 803–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C, Rosenkranz HS, Mednis B, 1969. Structure and development of viruses as observed in the electron microscope. V. Entry and uncoating of adenovirus. J. Virol 4, 777–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer CL, Nemerow GR, 2011. Viral weapons of membrane destruction: variable modes of membrane penetration by non-enveloped viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol 1, 44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhr LSA, Eklund C, Dillner J, 2018. Towards quality and order in human papillomavirus research. Virology 519, 74–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi A, Shum D, Morioka H, Otsuka E, Kasamatsu H, 2002. Interaction of the Vp3 nuclear localization signal with the importin alpha 2/beta heterodimer directs nuclear entry of infecting simian virus 40. J. Virol 76, 9368–9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen EK, Nemerow GR, Smith JG, 2010. Direct evidence from single-cell analysis that human {alpha}-defensins block adenovirus uncoating to neutralize infection. J. Virol 84, 4041–4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norkin LC, Anderson HA, Wolfrom SA, Oppenheim A, 2002. Caveolar endocytosis of simian virus 40 is followed by brefeldin A-sensitive transport to the endoplasmic reticulum, where the virus disassembles. J. Virol 76, 5156–5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Pasto G, Bazan-Peregrino M, Olaciregui NG, Restrepo-Perdomo CA Mato-Berciano A, Ottaviani D, Weber K, Correa G, Paco S, Vila-Ubach M, Cuadrado-Vilanova M, Castillo-Ecija H, Botteri G, Garcia-Gerique L, Moreno-Gilabert H, Gimenez-Alejandre M, Alonso-Lopez P, Farrera-Sal M, Torres-Manjon S, Ramos-Lozano D, Moreno R, Aerts I, Doz F, Cassoux N, Chapeaublanc E, Torrebadell M, Roldan M, Konig A, Sunol M, Claverol J, Lavarino C, Carmen De T, Fu L, Radvanyi F, Munier FL, Catala-Mora J, Mora J, Alemany R, Cascallo M, Chantada GL, Carcaboso AM, 2019. Therapeutic targeting of the RB1 pathway in retinoblastoma with the oncolytic adenovirus VCN-01. Sci. Transl. Med 11, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkmans L, Kartenbeck J, Helenius A, 2001. Caveolar endocytosis of simian virus 40 reveals a new two-step vesicular-transport pathway to the ER. Nat. Cell Biol 3, 473–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez L, Carrasco L, 1994. Involvement of the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase in animal virus entry. J. Gen. Virol 75 (Pt. 10), 2595–2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa A, Zhang W, Harrison MS, Goodner K, Kazakov T, Goodwin EC, Lipovsky A, Burd CG, Dimaio D, 2015. Direct binding of retromer to human papillomavirus type 16 minor capsid protein L2 mediates endosome exit during viral infection. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prchla E, Plank C, Wagner E, Blaas D, Fuchs R, 1995. Virus-mediated release of endosomal content in vitro: different behavior of adenovirus and rhinovirus serotype 2. J. Cell Biol 131, 111–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian M, Cai D, Verhey KJ, Tsai B, 2009. A lipid receptor sorts polyomavirus from the endolysosome to the endoplasmic reticulum to cause infection. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran MS, Bagchi P, Inoue T, Tsai B, 2015. A Non-enveloped virus hijacks host disaggregation machinery to translocate across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran MS, Engelke MF, Verhey KJ, Tsai B, 2017. Exploiting the kinesin-1 molecular motor to generate a virus membrane penetration site. Nat. Commun 8, 15496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran MS, Spriggs CC, Verhey KJ, Tsai B, 2018. Dynein engages and disassembles cytosol-localized SV40 to promote infection. J. Virol 92 (12), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy VS, Nemerow GR, 2014. Structures and organization of adenovirus cement proteins provide insights into the role of capsid maturation in virus entry and infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, 11715–11720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards RM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, Day PM, 2006. Cleavage of the papillomavirus minor capsid protein, L2, at a furin consensus site is necessary for infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 103, 1522–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards KF, Bienkowska-Haba M, Dasgupta J, Chen XS, Sapp M, 2013. Multiple heparan sulfate binding site engagements are required for the infectious entry of human papillomavirus type 16. J. Virol 87, 11426–11437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, Su J, Xu F, Weinstock H, 2013. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex. Transm. Dis 40, 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayedahmed EE, Kumari R, Shukla S, Hassan AO, Mohammed SI, York IA, Gangappa S, Sambhara S, Mittal SK, 2018. Longevity of adenovirus vector immunity in mice and its implications for vaccine efficacy. Vaccine 36, 6744–6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer KD, Gawlitza A, Spoden GA, Zhang XA, Lambert C, Berditchevski F, Florin L, 2013. Tetraspanin CD151 mediates papillomavirus type 16 endocytosis. J. Virol 87, 3435–3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelhaas M, Malmstrom J, Pelkmans L, Haugstetter J, Ellgaard L, Grunewald K, Helenius A, 2007. Simian virus 40 depends on ER protein folding and quality control factors for entry into host cells. Cell 131, 516–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelhaas M, Shah B, Holzer M, Blattmann P, Kuhling L, Day PM, Schiller JT, Helenius A, 2012. Entry of human papillomavirus type 16 by actin-dependent, clathrin- and lipid raft-independent endocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MA, Spoden GA, Florin L, Lambert C, 2011. Identification of the dynein light chains required for human papillomavirus infection. Cell. Microbiol 13, 32–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz WL, Haj AK, Schiff LA, 2012. Reovirus uses multiple endocytic pathways for cell entry. J. Virol 86, 12665–12675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiradake E, Lortat-Jacob H, Billet O, Kremer EJ, Cusack S, 2006. Structural and mutational analysis of human Ad37 and canine adenovirus 2 fiber heads in complex with the D1 domain of coxsackie and adenovirus receptor. J. Biol. Chem 281, 33704–33716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selinka HC, Florin L, Patel HD, Freitag K, Schmidtke M, Makarov VA, Sapp M, 2007. Inhibition of transfer to secondary receptors by heparan sulfate-binding drug or antibody induces noninfectious uptake of human papillomavirus. J. Virol 81, 10970–10980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Willingham MC, Pastan I, 1984. Adenovirus-dependent release of 51Cr from KB cells at an acidic pH. J. Biol. Chem 259, 14350–14353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem 69, 531–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, Campos SK, Wandinger-Ness A, Ozbun MA, 2008. Caveolin-1-dependent infectious entry of human papillomavirus type 31 in human keratinocytes proceeds to the endosomal pathway for pH-dependent uncoating. J. Virol 82, 9505–9512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smrt ST, Lorieau JL, 2017. Membrane fusion and infection of the influenza hemagglutinin. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 966, 37–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoden G, Freitag K, Husmann M, Boller K, Sapp M, Lambert C, Florin L, 2008. Clathrin- and caveolin-independent entry of human papillomavirus type 16— involvement of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs). PLoS One 3, e3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoden G, Kuhling L, Cordes N, Frenzel B, Sapp M, Boller K, Florin L, Schelhaas M, 2013. Human papillomavirus types 16, 18, and 31 share similar endocytic requirements for entry. J. Virol 87, 7765–7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staring J, Raaben M, Brummelkamp TR, 2018. Viral escape from endosomes and host detection at a glance. J. Cell Sci 131, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suikkanen S, Aaltonen T, Nevalainen M, Valilehto O, Lindholm L, Vuento M, Vihinen-Ranta M, 2003a. Exploitation of microtubule cytoskeleton and dynein during parvoviral traffic toward the nucleus. J. Virol 77, 10270–10279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suikkanen S, Antila M, Jaatinen A, Vihinen-Ranta M, Vuento M, 2003b. Release of canine parvovirus from endocytic vesicles. Virology 316, 267–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suomalainen M, Nakano MY, Keller S, Boucke K, Stidwill RP, Greber UF, 1999. Microtubule-dependent plus- and minus end-directed motilities are competing processes for nuclear targeting of adenovirus. J. Cell Biol 144, 657–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surviladze Z, Dziduszko A, Ozbun MA, 2012. Essential roles for soluble virion-associated heparan sulfonated proteoglycans and growth factors in human papillomavirus infections. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JR, Fernandez DJ, Thornton SM, Skeate JG, Luhen KP, Da Silva DM, Langen R, Kast WM, 2018. Heterotetrameric annexin A2/S100A10 (A2t) is essential for oncogenic human papillomavirus trafficking and capsid disassembly, and protects virions from lysosomal degradation. Sci. Rep 8, 11642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotman LC, Mosberger N, Fornerod M, Stidwill RP, Greber UF, 2001. Import of adenovirus DNA involves the nuclear pore complex receptor CAN/Nup214 and histone H1. Nat. Cell Biol 3, 1092–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai B, 2007. Penetration of nonenveloped viruses into the cytoplasm. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 23, 23–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai B, Ye Y, Rapoport TA, 2002. Retro-translocation of proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum into the cytosol. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 3, 246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai B, Gilbert JM, Stehle T, Lencer W, Benjamin TL, Rapoport TA, 2003. Gangliosides are receptors for murine polyoma virus and SV40. EMBO J. 22, 4346–4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, Thomas CC, Markowitz LE, Benard VB, 2018. Trends in Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers—United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep 67, 918–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Raaij MJ, Mitraki A, Lavigne G, Cusack S, 1999. A triple beta-spiral in the adenovirus fibre shaft reveals a new structural motif for a fibrous protein. Nature 401, 935–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak CP, Tsai B, 2011. A PDI family network acts distinctly and coordinately with ERp29 to facilitate polyomavirus infection. J. Virol 85, 2386–2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak CP, Ravindran MS, Inoue T, Tsai B, 2014. A cytosolic chaperone complexes with dynamic membrane J-proteins and mobilizes a nonenveloped virus out of the endoplasmic reticulum. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Mbaeyi SA, Fredua B, Stokley S, 2018. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep 67, 909–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Huang S, Kapoor-Munshi A, Nemerow G, 1998. Adenovirus internalization and infection require dynamin. J. Virol 72, 3455–3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Li ZY, Liu Y, Persson J, Beyer I, Moller T, Koyuncu D, Drescher MR, Strauss R, Zhang XB, Wahl JK 3rd, Urban N, Drescher C, Hemminki A, Fender P, Lieber A, 2011. Desmoglein 2 is a receptor for adenovirus serotypes 3, 7, 11 and 14. Nat. Med 17, 96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Calder LJ, Harrison SC, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, 1999. Structural basis for membrane fusion by enveloped viruses. Mol. Membr. Biol 16, 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham TJ, Mathias P, Cheresh DA, Nemerow GR, 1993. Integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell 73, 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiethoff CM, Wodrich H, Gerace L, Nemerow GR, 2005. Adenovirus protein VI mediates membrane disruption following capsid disassembly. J. Virol 79, 1992–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Kasamatsu H, 1993. Role of nuclear pore complex in simian virus 40 nuclear targeting. J. Virol 67, 119–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi Y, Greber UF, 2016. Principles of virus uncoating: cues and the snooker ball. Traffic 17, 569–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf MA, Zhou X, Mukherjee S, Chintakuntlawar AV, Lee JY, Ramke M, Chodosh J, Rajaiya J, 2013. Caveolin-1 associated adenovirus entry into human corneal cells. PLoS One 8, e77462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Kazakov T, Popa A, Dimaio D, 2014. Vesicular trafficking of incoming human papillomavirus 16 to the Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum requires gamma-secretase activity. MBio 5, e01777–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Monteiro Da Silva G, Deatherage C, Burd C, Dimaio D, 2018. Cell-penetrating peptide mediates intracellular membrane passage of human papillomavirus L2 protein to trigger retrograde trafficking. Cell 174 1465–1476.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta C, Schoehn G, Chroboczek J, Cusack S, 2005. The structure of the human adenovirus 2 penton. Mol. Cell 17, 121–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]