Abstract

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) pulmonary infections are a growing concern worldwide, with a disproportionate incidence in persons with pre-existing health conditions. NTM have frequently been found in municipally-treated drinking water and building plumbing, leading to the hypothesis that an important source of NTM exposure is drinking water. The identification and quantification of NTM in environmental samples are complicated by genetic variability among NTM species, making it challenging to determine if clinically-relevant NTM are present. Additionally, their unique cellular features and lifestyles make NTM and their nucleic acids difficult to recover. This review highlights recent work focused on quantification and characterization of NTM and on understanding the influence of source water, treatment plants, distribution systems, and building plumbing on the abundance of NTM in drinking water.

Keywords: Nontuberculous mycobacteria, MAC, Mycobacterium avium, opportunistic pathogens, drinking water

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Infections due to opportunistic pathogens (OPs) are a growing public health concern. OPs generally only infect susceptible persons, including those with pre-existing health conditions and the immunocompromised. Like other water-associated OPs such as Legionella pneumophila and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are present in the environment and can proliferate in drinking water systems. NTM possess waxy, “acid-fast” cell walls, which render them more hydrophobic and might allow them to be more readily aerosolized than other bacteria [1]. Sometimes called “biofilm pioneers”, NTM can attach to a variety of surfaces and establish biofilms, and are among select bacteria with the ability to enter and survive within amoebae [1,2]. This combination of properties confers the resistance needed to survive conventional water treatment and proliferate in drinking water systems despite the presence of disinfectant residuals [1].

NTM predominately cause pulmonary infections but also cause skin, soft tissue, and post-operative infections [3–6]. A 2012 study estimated the annual cost of hospitalizations in the U.S. due to pulmonary NTM infections to be $194 million [7]. NTM infection prevalence has increased over the last two decades. Specifically, positive specimen reporting rates in four U.S. states increased from 8.2 to 16 per 100,000 persons from 1994 to 2014, and rates in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland rose from 0.9 to 7.6 per 100,000 persons from 1995 to 2012 [8–10]. However, the true prevalence of NTM infection is unknown and challenging to determine due to the lack of reporting requirements and difficulties with NTM identification from clinical specimens.

Despite the health and economic importance of NTM infections, little is known about specific sources of human exposure to NTM. Recent work has found NTM in drinking water and water system biofilms, suggesting that contact with drinking water might be one source of pulmonary infections [11,12]. However, substantial knowledge gaps, including the lack of risk assessment models, difficulty in evaluating mechanisms of exposure, and host-specific factors that influence susceptibility, have made it difficult to link NTM infections to drinking water and develop mitigation strategies. Given the recent increases in NTM infections, it is paramount that we:

understand the sources and routes of NTM exposure;

identify the risk factors associated with NTM infections; and

develop risk mitigation strategies to reduce NTM infection.

This review focuses on recent efforts to characterize NTM transfer from natural environments to human hosts through drinking water.

Identification of NTM and Their Characteristics

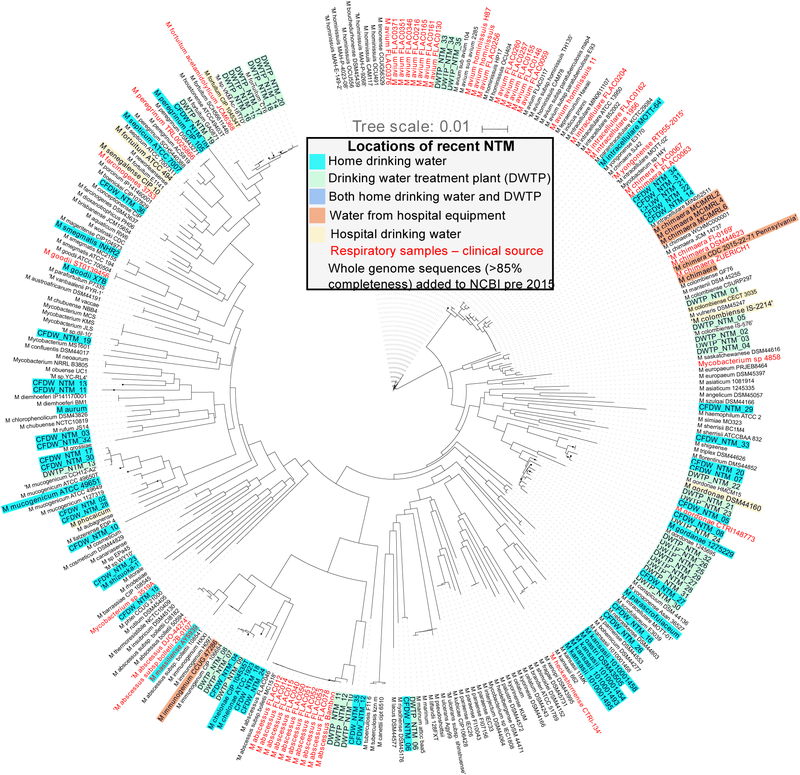

The genus Mycobacterium consists of more than 170 species [13–15]. The vast majority of these species comprise the so-called “nontuberculous mycobacteria”, of which only a few account for most human NTM infections [8,16]. Examples of NTM often associated with infection are the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC, which includes M. avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and Mycobacterium chimaera), the Mycobacterium abscessus complex (MAB, which includes M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii), Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium kansasii, and Mycobacterium chelonae [13,16–18]. Identification of NTM is crucial for infection diagnosis, prevention, and risk assessment. NTM identification strategies include culturing with NTM-specific media and use of methods that target NTM-specific proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids (Table 1). Among these methods, nucleic-acid based approaches are most commonly used and employ extraction protocols with rigorous physical and enzymatic steps to lyse the waxy NTM cell wall [19,20]. Sequencing the 16S rRNA gene, which is commonly used for bacterial identification, often does not allow for identification of NTM to the species, subspecies, or strain levels [15,18]. NTM identification beyond the species level is particularly important for MAC and MAB members, as certain subspecies within these groups are associated with distinct clinical outcomes [18,21]. Though sequencing whole genomes or several genes is often necessary for species or strain level resolution, some single genes (rpoB and hsp65) can provide species resolution depending on the specific sequence site and length. These techniques have been used to identify similar species and strains of NTM within clinical and water system samples collected in the same studies [22,23]. Figure 1 shows the taxonomic relatedness of NTM species recently isolated from human respiratory tract and drinking water samples using rpoB sequence analysis.

Table 1.

Common methods for the identification and quantification of NTM

| Type of analysis/target molecule | Method | Target | Typical level of identification | Type of sample that can be processed | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-based | Lowenstein-Jensen slant | Viable and culturable Mycobacterium cells | Presumptive genus-level - although subsequent molecular or biochemical methods are required to confirm | Mixed culture sample with subsequent passage to isolate pure cultures | [11,12,23,28,32–36,39,41,44,58,61–63,78–80] |

| Middlebrook medium | |||||

| Nucleic acids | PCR | 16S rRNA gene | genus-level - presence or absence | Pure culture or mixed culture sample | [81] |

| 16S - 23S rRNA gene ITS region | species-level - presence or absence | Pure culture or mixed culture sample | [82] | ||

| Random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) | Species-, subspecies-level | Pure culture | [83] | ||

| qPCR | 16S rRNA gene | genus-level | Mixed culture sample | [27,49,53,54] | |

| atpE gene | genus-level | Mixed culture sample | [31,40,42] | ||

| 16S - 23S rRNA gene ITS region | species-level | Mixed culture sample | [43,48,52] | ||

| hsp65 gene | genus- or species-level depending on primers | Mixed culture sample | [84] | ||

| Sequencing | Whole genome | sub-species level1 | Pure culture or mixed culture sample | [15,23,61,79] | |

| 16S rRNA gene | genus-, complex-, or species-level2 | Pure culture or mixed culture sample | [11,12,19,30,37,47,50,53,54,57,62,85,86] | ||

| rpoB gene | genus-, complex-, or species-level2 | Pure culture or mixed culture sample | [20,22,39,42] | ||

| hsp65 gene | genus-, complex-, or species-level2 | Pure culture or mixed culture sample | [11,12,86] | ||

| 16S - 23S rRNA gene ITS region | genus-, complex-, or species-level2 | Pure culture or mixed culture sample | [54] | ||

| Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) | species-level | Pure culture | [17,86] | ||

| Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis | Viable and culturable Mycobacterium cells | Complex- or species-level | Pure culture | [5,78,79] | |

| PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) | rpoB gene | sub-species level | Pure culture | [87] | |

| hsp65 gene | species-level | Pure culture | [23,28,88] | ||

| 16S - 23S rRNA gene ITS region | complex- or species level | Pure culture | [89] | ||

| Microarray and probe hybridization | 16S rRNA gene | complex- or species level | Mixed culture sample | [81,85] | |

| gyrB gene | Complex or species level | Mixed culture sample | [90] | ||

| Lipids | High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) | Mycolic acids | Species-level | Pure culture | [79,91] |

| Proteins | Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization- time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) | Cellular proteins | Complex or species level | Pure culture | [79,92] |

level of identification and genome completeness achieved vary based on sequencing platform and level of diversity in mixed samples,

level of identification achieved depends on the target gene, length of amplicon, and sequencing platform used.

Figure 1.

Dendrogram showing relatedness of NTM species and strains based on rpoB gene sequences. Text colors refer to the types of samples the sequences were obtained from (light blue - home drinking water samples; green – drinking water treatment plant samples; dark blue – sequences found in both home and drinking water samples; orange – water from hospital equipment; yellow – hospital drinking water; red – clinical respiratory samples; black – whole genome sequences at least 85% complete added to NCBI prior to 2015). Sources provided in SI.

NTM in Source Waters Used for Drinking Water Production

Regional clustering of pulmonary NTM infections has led to investigations of links between NTM infection and geographic and environmental factors, including characteristics of source waters used for drinking water production. An analysis of NTM infections in Medicare patients in the U.S. found 55 counties in eight states with clusters of infection, and the two counties with the highest risk were located in Louisiana and Hawaii [24]. Geographic factors that correlate with elevated NTM infection rates include higher evapotranspiration rates, a greater percentage of land covered by water, and household proximity to water [24,25]. An evaluation of U.S. NTM infections published in 2017 noted that, while MAC infections were common across the country, higher prevalence of MAB and M. chelonae infections was reported in the west [26]. Although it appears that there are distinct regional trends, it is unclear how geographic and environmental factors influence the prevalence of certain species and the risk of NTM infection.

NTM occurrence in source waters is also being investigated. Higher concentrations of M. avium in water have been associated with higher turbidity and particulate matter, possibly due to attachment to particles [27,28]. Furthermore, higher rates of NTM infection have been linked to the use of tap water derived from surface water sources versus from groundwater sources [29]. However, treatment and distribution system factors might have a greater impact than source water on NTM concentrations at the tap. For example, a source to tap monitoring study in Louisiana observed low NTM relative abundances in the Mississippi River water and drinking water leaving the treatment plant, but high relative abundances in distribution system and tap water [30]. At a minimum, this finding suggests that NTM persisted during distribution, but could mean that growth of NTM took place in the distribution system and building plumbing. Methods that allow monitoring of changes in absolute abundances would be necessary to confirm NTM growth [31]. Although it appears that certain environmental conditions favor the proliferation of NTM in source water, these factors do not necessarily contribute to NTM concentrations at the tap. Further work is needed to assess the risks posed by the use of source waters containing NTM for drinking water production.

NTM Survival Through Drinking Water Treatment Processes

M. avium has been a potential concern in drinking water for decades and has been included on all U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Contaminant Candidate Lists. Nevertheless, NTM monitoring and reporting for drinking water is not required in the U.S. or other countries. This lack of surveillance has limited the evaluation of NTM removal through treatment systems. Much of the NTM-related drinking water research thus far has focused on NTM inactivation through disinfection. Pure cultures of M. avium require a disinfection dose, expressed as the product of disinfectant concentration and time of exposure (CT), up to 2,300-fold and 50-fold higher for 99.9 percent inactivation with chlorine and ozone, respectively, compared to Escherichia coli [32]. Similarly, inactivation of M. fortuitum and Mycobacterium mucogenicum with free chlorine requires a substantially higher CT than E. coli and Bacillus subtilis [33]. M. avium resistance to chloramine has also been observed, though reported values vary [32,34]. NTM inactivation at a given CT further varies based on the source of the strain (laboratory or environmentally-isolated strain), pH, nutrient availability, temperature, and whether the organism is sessile or planktonic [32,33,35,36]. Recently, increases in viable cell concentrations and the relative abundance of NTM were observed after initial exposure to ozone in a drinking water treatment plant’s ozone contactors [37]. Further investigation determined that NTM were accumulating in biofilms and solids in the ozone contactors, which had formed due to non-ideal flow conditions. Such variations in inactivation for different growth conditions and strains make it difficult to simulate inactivation effectively in the laboratory and warrant further investigation in full-scale systems.

NTM survival has also been linked to entry into eukaryotic cells. Amoebae, such as Hartmanella vermiformis and Acanthamoeba spp., are commonly found in water systems and feed on bacteria via phagocytosis [38]. NTM possess the ability to survive phagocytosis and can live and sometimes replicate inside amoebae [39–41]. Surveys in drinking water have found that NTM and amoebae occurrence are often highly associated and that inactivation of M. avium inside Acanthamoeba required substantially higher CT values than free-living M. avium [42–44]. Furthermore, the demonstration that monochloramine exposure leads to the upregulation of mammalian cell entry gene 1 (mce1) in M. avium, which facilitates NTM entry into eukaryotic cells, is cause for concern (D Berry, PhD thesis, University of Michigan, 2009). This research suggests that, in addition to incidental amoebal uptake of NTM during grazing, some NTM might also initiate cell entry. The presence of amoebae in drinking water might therefore select for NTM that not only survive disinfection, but can also potentially infect other eukaryotic cells, including human cells. Given these findings, further investigation is needed to characterize how NTM respond to external pressures, such as oxidant (e.g., ozone, chlorine, chloramine) exposure, and to explore new methods for prevention of NTM infection.

NTM in Distribution Systems and Building Plumbing

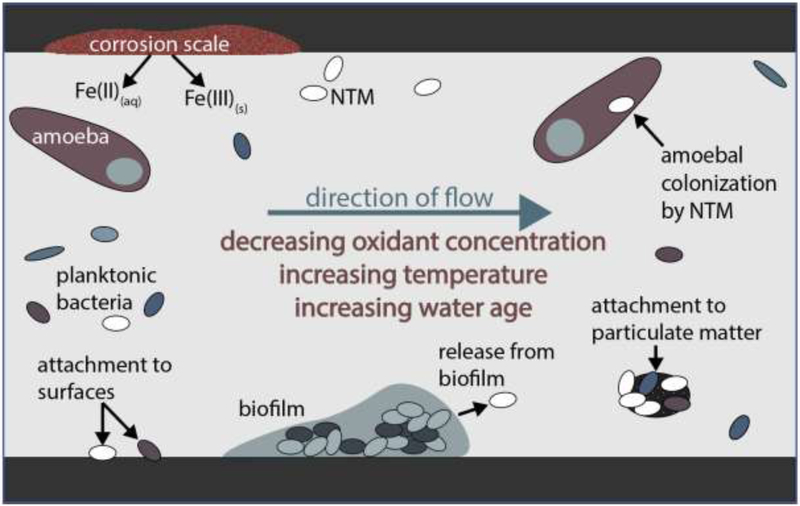

Approximately 90% of the U.S. population receives drinking water treated in centralized treatment plants (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/safe-drinking-water-information-system-sdwis-federal-reporting). Treated water is transported through underground distribution systems and storage tanks, reaching consumers through building plumbing. Although utilities in the U.S. and many other countries provide a disinfectant residual to control microbial growth after treatment, dissipation of that residual, nutrient availability, and other factors result in drinking water that contains bacteria at levels as high as 106 to 108 cells/liter [45,46]. While NTM are resistant to both chlorine and chloramines, they are generally considered to be preferentially selected for in distribution systems where monochloramine is used as the residual disinfectant [11,47]. Other distribution system characteristics, such as water age, pipe material, accumulation of solids in storage tanks, and concentrations of dissolved metals could also influence NTM diversity, abundance, and growth [31,48,49]. Figure 2 summarizes interactions of chemical, biological, and physical factors that contribute to NTM occurrence in distribution systems. The complexity and heterogeneity of water systems make it challenging to link NTM growth and persistence to a few definable factors; more work is required to develop distribution system management strategies to mitigate the presence of NTM.

Figure 2.

Factors influencing NTM concentrations in distribution systems

In contrast to distribution system studies, research on NTM in building plumbing is plentiful, likely due to the number of NTM infections linked to public buildings. Large surface area to volume ratios, intermittent stagnation, low disinfectant residuals, and warm temperatures make building plumbing a favorable environment for bacterial attachment and growth [50–53]. NTM have been found in numerous plumbing appurtenances, including faucets and showerheads [12,22,54]. An analysis of the microbial composition of showerhead biofilms in U.S. cities found significant enrichment for MAC spp., with higher relative abundances of MAC spp. in biofilms compared to in the water feeding into showerheads [54]. Higher relative abundances of NTM have also been observed in showerheads fed by municipal water versus well water [12,54]. A recent survey of homes in Ann Arbor, Michigan receiving chloraminated water found NTM in all building plumbing water and biomass samples collected [31]. NTM abundance has been linked to various abiotic and biotic parameters in building plumbing, including iron concentration, water age, disinfectant type, and the presence of amoebae [11,31,42]. However, further research is needed to better characterize the concentrations of clinically relevant strains and understand how these concentrations might correlate to specific chemical and physical parameters.

Potential interventions for OP control in building plumbing include chemical and physical means of deselection. Studies evaluating on-site disinfectant addition have shown varying levels of efficacy and note the potential for corrosion and scaling caused by the added oxidants [55,56]. One study also noted the increase in relative abundance of NTM with the implementation of on-site monochloramine disinfection [57]. An evaluation of UV irradiation found that the dose required for inactivation of 15 strains of M. avium subsp. hominissuis varied widely across strains and was substantially higher than doses typically used in water treatment [58]. While such studies provide insights into potential control strategies for NTM, more work is needed to identify mitigation strategies that do not result in unintended consequences (e.g., selection for other OPs).

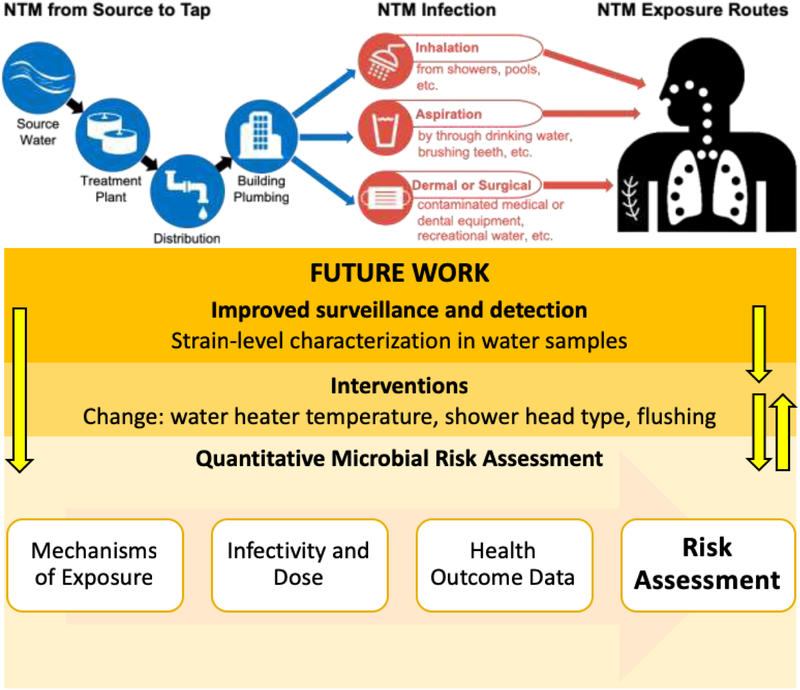

Routes of Exposure and Infection

Studies have repeatedly shown that rates of NTM pulmonary infection around the world are increasing. While the reasons for this rise are unclear, increased exposure to NTM might be a contributing factor [59]. Linking NTM infections to a particular source is challenging and is complicated by often long periods of time between NTM exposure and diagnosis, lack of standardized methods for strain genotyping, and the pervasiveness of NTM in the environment. The most probable routes of NTM pulmonary infection are through inhalation and aspiration, whereas contact with contaminated surfaces is likely significant for skin, soft tissue, and post-operative infections [4,16,60] (Figure 3). While NTM are believed to be inhaled primarily through water aerosols, complex air flow dynamics and low biomass yields make nucleic acid-based analyses of aerosols challenging. Despite these challenges, measurable concentrations of NTM in aerosols have been detected in air samples from bathrooms, showers, humidifiers, hot tubs, and therapy pools [61–64]. Further studies on NTM quantification and detection in aerosol samples are required to elucidate the link between water and aerosolized NTM.

Figure 3.

Overview of possible NTM infection and exposure routes through drinking water and suggested future work needed for NTM infectivity and pulmonary infection prevention.

While NTM can infect humans through multiple routes, the risk of infection is highly dependent on the host. Risk factors that contribute to a person’s susceptibility include increased age and pre-existing health conditions. Persons with lung pathology or compromised immune systems, such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis, and human immunodeficiency virus infection, are at particular risk of pulmonary NTM infection [65–68]. Genetic factors and use of some immunosuppressing medications are also thought to increase susceptibility [69–71]. Although efforts have been made to assess the risk posed by NTM in water through quantitative microbial risk assessment, so far these studies do not capture the full breadth of the complexity associated with NTM in drinking water [72–74]. This type of risk assessment is complex, and drinking water-specific studies are needed to elucidate how host and environmental factors influence risk of NTM infection.

Future Work

Although our ability to detect and identify NTM has greatly improved over the last two decades, little is known about how the observed concentrations of various NTM in drinking water correlate to the disease burden. As shown in Figure 3, considerable work is needed to assess how various exposure mechanisms, concentrations of NTM, and host-specific factors contribute to risk of pulmonary infection. Aerosolization of NTM is in particular need of additional investigation given the hypothesis that aerosols are a central route of exposure. Recent studies with other infectious bacteria have shown that certain species and strains were preferentially aerosolized, and that ease of aerosolization might correlate with strains more frequently associated with infection [75,76]. Similar studies are needed to determine how NTM concentrations in water correlate with levels in aerosols to narrow the focus of risk assessment to strains that are most readily aerosolized. Compared to other, better-studied bacteria, relatively little is known about how exposure to NTM correlates with risk of infection and what can be considered an infective dose. The risk of NTM drug resistance is also of growing interest, as NTM infections typically require extended treatment with multiple antimicrobials and recurrence of infection is common [77,78]. Given the ubiquity of NTM in water and other environments, complete elimination or inactivation of viable organisms during drinking water treatment and distribution might not be possible. Rather, NTM levels in drinking water must be managed to minimize the risk of infection, as is done with other microorganisms of concern.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are pervasive in drinking water systems.

NTM are resistant to disinfection and are found in pipe and showerhead biofilms.

Inhalation and/or aspiration of drinking water might cause NTM pulmonary infections.

Improved infection reporting is needed to better characterize NTM health burden.

Linking NTM infections to water sources is difficult and requires further study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Terese Olson, Amy Pruden, Dongjuan Dai, and Linda Kalikin for helpful discussions. This research was supported with funding from the Water Research Foundation (Project #4721) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (LIPUMA15G0). Katherine Dowdell was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE 1256260. Sarah-Jane Haig was supported by an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Microbiology of the Built Environment fellowship (G-2014-13739) and a University of Michigan Dow Sustainability postdoctoral fellowship. Yun Shen was supported by an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Microbiology of the Built Environment Fellowship (G-2016-7250). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding sources.

References

- 1.Falkinham JO: Mycobacterium avium complex: Adherence as a way of life. AIMS Microbiol 2018, 4:428–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greub G, Raoult D: Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004, 17:413–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falkinham JO: Current epidemiologic trends of the nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Curr Environ Health Rep 2016, 3:161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misch EA, Saddler C, Davis JM: Skin and soft tissue infections due to nontuberculous mycobacteria. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2018, 20:6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnabel D, Esposito DH, Gaines J, Ridpath A, Anita Barry M, Feldman KA, Mullins J, Burns R, Ahmad N, Nyangoma EN, et al. : Multistate US outbreak of rapidly growing mycobacterial infections associated with medical tourism to the Dominican Republic, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2016, 22:1340–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen KB, Yuh DD, Schwartz SB, Lange RA, Hopkins R, Bauer K, Marders JA, Delgado Donayre J, Milligan N, Wentz C: Nontuberculous mycobacterium infections associated with heater-cooler devices. Ann Thorac Surg 2017, 104:1237–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collier SA, Stockman LJ, Hicks LA, Garrison LE, Zhou FJ, Beach MJ: Direct healthcare costs of selected diseases primarily or partially transmitted by water. Epidemiol Infect 2012, 140:2003–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donohue MJ: Increasing nontuberculous mycobacteria reporting rates and species diversity identified in clinical laboratory reports. BMC Infect Dis 2018, 18:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study used clinical laboratory reports from four U.S. states to evaluate the isolation rates of NTM and the proportion of NTM infections attributed to MAC and MAB. The rate of NTM positive specimens doubled over the last 20 years, and the proportion of detections of MAC and MAB versus other types of NTM also increased.

- 9.Moore JE, Kruijshaar ME, Ormerod LP, Drobniewski F, Abubakar I: Increasing reports of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 1995–2006. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah NM, Davidson JA, Anderson LF, Lalor MK, Kim J, Thomas HL, Lipman M, Abubakar I: Pulmonary Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare is the main driver of the rise in non-tuberculous mycobacteria incidence in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 2007–2012. BMC Infect Dis 2016, 16:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * The authors analyzed reports of NTM postitive cultures in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland between 2007 to 2012. The overall incidence of NTM infection was found to have increased over the period and was primarily due to pulmonary infections caused by MAC. The rates of extrapulmonary infection did not rise during the study period.

- 11.Donohue MJ, Mistry JH, Donohue JM, O’Connell K, King D, Byran J, Covert T, Pfaller S: Increased frequency of nontuberculous mycobacteria detection at potable water taps within the United States. Environ Sci Technol 2015, 49:6127–6133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gebert MJ, Delgado-Baquerizo M, Oliverio AM, Webster TM, Nichols LM, Honda JR, Chan ED, Adjemian J, Dunn RR, Fierer N: Ecological analyses of mycobacteria in showerhead biofilms and their relevance to human health. mBio 2018, 9:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * About 650 showerhead biofilm samples were collected by citizen scientists from locations across the U.S. and Europe and 16S rRNA gene sequencing was used to determine the relative abundance of bacterial genera within these samples with a particular focus on NTM. In the U.S., the relative abundance of NTM in biofilms collected from showers fed by municipal water was greater than in biofilms collected from showers fed well water. On average, the NTM relative abundance in U.S. samples was 2.3 times greater than in European samples. Both findings can likely be attributed to differences in disinfectant concentrations. The study also reported a correlation of relative abundances of free-living amoebae and NTM. Sequencing of the hsp65 gene found varying relative abundances of NTM that harbor pathogens in different geographic regions and the study reported a correlation between these results and the prevalence of reported NTM disease.

- 13.Tortoli E: Microbiological features and clinical relevance of new species of the genus Mycobacterium. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014, 27:727–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falkinham JO: Environmental sources of nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Chest Med 2015, 36:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedrizzi T, Meehan CJ, Grottola A, Giacobazzi E, Fregni Serpini G, Tagliazucchi S, Fabio A, Bettua C, Bertorelli R, De Sanctis V, et al. : Genomic characterization of nontuberculous mycobacteria. Sci Rep 2017, 7:45258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, Holland SM, Horsburgh R, Huitt G, Iademarco MF, et al. : An official ATS/IDSA statement: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. 2007, 175:367–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SY, Shin SH, Moon SM, Yang B, Kim H, Kwon OJ, Huh HJ, Ki CS, Lee NY, Shin SJ, et al. : Distribution and clinical significance of Mycobacterium avium complex species isolated from respiratory specimens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2017, 88:125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffith DE, Brown-Elliott BA, Benwill JL, Wallace RJ: Mycobacterium abscessus: “Pleased to meet you, hope you guess my name…” Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015, 12:436–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caverly LJ, Carmody LA, Haig SJ, Kotlarz N, Kalikin LM, Raskin L, LiPuma JJ: Culture-independent identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria in cystic fibrosis respiratory samples. PLoS ONE 2016, 11:e0153876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haig S-J, Kotlarz N, LiPuma JJ, Raskin L: A high-throughput approach for identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria in drinking water reveals relationship between water age and Mycobacterium avium. mBio 2018, 9:e02354–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** A DNA extraction procedure was developed that yielded eight times more NTM DNA than commercial DNA extraction kits. This method was coupled with high-throughput, single-molecule real-time sequencing of NTM rpoB genes to identify NTM species in samples taken from a chloraminated disitribution system. Increased water age was found to positivily correlate with the relative abundance of M. avium subsp. avium.

- 21.Cho EH, Huh HJ, Song DJ, Moon SM, Lee SH, Shin SY, Kim CK, Ki CS, Koh WJ, Lee NY: Differences in drug susceptibility pattern between Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare isolated in respiratory specimens. J Infect Chemother 2018, 24:315–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honda JR, Hasan NA, Davidson RM, Williams MD, Epperson LE, Reynolds PR, Smith T, Iakhiaeva E, Bankowski MJ, Wallace RJ Jr., et al. : Environmental nontuberculous mycobacteria in the Hawaiian Islands. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016, 10:e0005068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * NTM isolates were obtained from water biofilms and soils from 62 households and 15 clinical respiratory samples in Hawaii and were analyzed using partial rpoB gene sequencing. In these environmental and clinical samples, M. chimaera was the most frequently recovered NTM, and no M. avium was recovered from either sample type. The dominance of M. chimaera and lack of M. avium suggests that climatic or geographic conditions in Hawaii might promote the growth of NTM different than those most commonly found in Asia or the continental U.S.

- 23.Lande L, Alexander DC, Wallace RJ, Kwait R, Iakhiaeva E, Williams M, Cameron ADS, Olshefsky S, Devon R, Vasireddy R, et al. : Mycobacterium avium in community and household water, suburban Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, 2010 – 2012. Emerg Infect Dis 2019, 25:473–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Falkinham JO, Holland SM, Prevots DR: Spatial clusters of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012, 186:553–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouso JM, Burns JJ, Amin R, Livingston FR, Elidemir O: Household proximity to water and nontuberculous mycobacteria in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2017, 52:324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spaulding AB, Lai YL, Zelazny AM, Olivier KN, Kadri SS, Rebecca Prevots D, Adjemian J: Geographic distribution of nontuberculous mycobacterial species identified among clinical isolates in the United States, 2009–2013. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017, 14:1655–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang T, Cui Q, Huang Y, Dong P, Wang H, Liu WT, Ye Q: Distribution comparison and risk assessment of free-floating and particle-attached bacterial pathogens in urban recreational water: Implications for water quality management. Sci Total Environ 2018, 613–614:428–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falkinham JO, Norton CD, LeChevallier MW: Factors influencing numbers of Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other mycobacteria in drinking water distribution systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 2001, 67:1225–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotlarz N, Raskin L, Zimbric MA, Errickson J, LiPuma JJ, Caverly LJ: A retrospective analysis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infection and monochloramine disinfection of municipal drinking water in Michigan. mSphere [under review], [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hull NM, Holinger EP, Ross KA, Robertson CE, Harris JK, Stevens MJ, Pace NR: Longitudinal and source-to-tap New Orleans, LA, U.S.A. drinking water microbiology. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51:4220–4229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haig S-J, Kotlarz N, Kalikin L, Chen T, Guikema S, LiPuma JJ, Raskin L: Abundance of opportunistic bacterial pathogens in household drinking water are impacted by dissolved iron concentration and distribution system parameters. Environ Sci Technol [under review], [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor RH, Falkinham JO, Norton CD, LeChevallier MW: Chlorine, chloramine, chlorine dioxide, and ozone susceptibility of Mycobacterium avium. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000, 66:1702–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, Sui M, Yuan B, Li H, Lu H: Inactivation of two mycobacteria by free chlorine: Effectiveness, influencing factors, and mechanisms. Sci Total Environ 2019, 648:271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luh J, Tong N, Raskin L, Mariñas BJ: Inactivation of Mycobacterium avium with monochloramine. Environ Sci Technol 2008, 42:8051–8056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Dantec C, Duguet JP, Montiel A, Dumoutier N, Dubrou S, Vincent V: Chlorine disinfection of atypical mycobacteria isolated from a water distribution system. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002, 68:1025–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steed KA, Falkinham JO: Effect of growth in biofilms on chlorine susceptibility of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006, 72:4007–4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * The relative abundance of bacterial genera was monitored using 16S rRNA gene sequencing of cultures and DNA extracted from membrane-intact cells in biomass samples in water and biofilm samples collected from a full-scale drinking water treatment plant ozone contactor. Biofilm formation on the ozone contactor walls and sludge accumulation within a hydraulic dead zone were suggested to be responsible for the surprising finding that total viable cells and the relative abundance of NTM increased after the first ozone contact chamber.

- 37.Kotlarz N, Rockey N, Olson TM, Haig S-J, Sanford L, LiPuma JJ, Raskin L: Biofilms in full-scale drinking water ozone contactors contribute viable bacteria to ozonated water. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52:2618–2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas JM, Ashbolt NJ: Do free-living amoebae in treated drinking water systems present an emerging health risk? Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45:860–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delafont V, Samba-Louaka A, Cambau E, Bouchon D, Moulin L, Héchard Y: Mycobacterium llatzerense, a waterborne Mycobacterium, that resists phagocytosis by Acanthamoeba castellanii. Sci Rep 2017, 7:46270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samba-Louaka A, Robino E, Cochard T, Branger M, Delafont V, Aucher W, Wambeke W, Bannantine JP, Biet F, Héchard Y: Environmental Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis hosted by free-living amoebae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018, 8:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.da Silva JL, Nguyen J, Fennelly KP, Zelazny AM, Olivier KN: Survival of pathogenic Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. massiliense in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Res Microbiol 2017, 169:56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delafont V, Mougari F, Cambau E, Joyeux M, Bouchon D, Héchard Y, Moulin L: First evidence of amoebae-mycobacteria association in drinking water network. Environ Sci Technol 2014, 48:11872–11882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu J, Struewing I, Vereen E, Kirby AE, Levy K, Moe C, Ashbolt N: Molecular detection of Legionella spp. and their associations with Mycobacterium spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and amoeba hosts in a drinking water distribution system. J Appl Microbiol 2016, 120:509–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berry D, Horn M, Xi C, Raskin L: Mycobacterium avium infections of Acanthamoeba strains: Host strain variability, grazing-acquired infections, and altered dynamics of inactivation with monochloramine. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010, 76:6685–6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ling F, Whitaker R, LeChevallier MW, Liu W-T: Drinking water microbiome assembly induced by water stagnation. ISME J 2018, 12:1520–1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lipphaus P, Hammes F, Kötzsch S, Green J, Gillespie S, Nocker A: Microbiological tap water profile of a medium-sized building and effect of water stagnation. Environ Technol 2014, 35:620–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gomez-Alvarez V, Revetta RP, Domingo JWS: Metagenomic analyses of drinking water receiving different disinfection treatments. Appl Environ Microbiol 2012, 78:6095–6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qin K, Struewing I, Domingo J, Lytle D, Lu J: Opportunistic pathogens and microbial communities and their associations with sediment physical parameters in drinking water storage tank sediments. Pathogens 2017, 6:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H, Masters S, Falkinham JO, Edwards MA, Pruden A: Distribution system water quality affects responses of opportunistic pathogen gene markers in household water heaters. Environ Sci Technol 2015, 49:8416–8424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ji P, Parks J, Edwards MA, Pruden A: Impact of water chemistry, pipe material and stagnation on the building plumbing microbiome. PLoS ONE 2015, 10:e0141087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bédard E, Laferrière C, Déziel E, Prévost M: Impact of stagnation and sampling volume on water microbial quality monitoring in large buildings. PLoS ONE 2018, 13:e0199429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lu J, Buse H, Struewing I, Zhao A, Lytle D, Ashbolt N: Annual variations and effects of temperature on Legionella spp. and other potential opportunistic pathogens in a bathroom. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2017, 24:2326–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li H, Li S, Tang W, Yang Y, Zhao J, Xia S, Zhang W, Wang H: Influence of secondary water supply systems on microbial community structure and opportunistic pathogen gene markers. Water Res 2018, 136:160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feazel LM, Baumgartner LK, Peterson KL, Frank DN, Harris JK, Pace NR: Opportunistic pathogens enriched in showerhead biofilms. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2009, 106:16393–16399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Casini B, Aquino F, Totaro M, Miccoli M, Galli I, Manfredini L, Giustarini C, Costa A, Tuvo B, Valentini P, et al. : Application of hydrogen peroxide as an innovative method of treatment for Legionella control in a hospital water network. Pathogens 2017, 6:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rhoads WJ, Pruden A, Edwards MA: Anticipating challenges with in-building disinfection for control of opportunistic pathogens. Water Environ Res 2014, 86:540–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baron JL, Vikram A, Duda S, Stout JE, Bibby K: Shift in the microbial ecology of a hospital hot water system following the introduction of an on-site monochloramine disinfection system. PLoS ONE 2014, 9:e102679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schiavano GF, De Santi M, Sisti M, Amagliani G, Brandi G: Disinfection of Mycobacterium avium subspecies hominissuis in drinking tap water using ultraviolet germicidal irradiation. Environ Technol 2017, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nishiuchi Y, Iwamoto T, Maruyama F: Infection sources of a common non-tuberculous mycobacterial pathogen, Mycobacterium avium complex. Front Med 2017, 4:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lande L: Environmental niches for NTM and their impact on NTM disease In Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease: A Comprehensive Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Edited by Griffith DE. Humana Press; 2019:131–144. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morimoto K, Aono A, Murase Y, Sekizuka T, Kurashima A, Takaki A, Sasaki Y, Igarashi Y, Chikamatsu K, Goto H, et al. : Prevention of aerosol isolation of nontuberculous mycobacterium from the patient’s bathroom. ERJ Open Res 2018, 4:00150–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomson R, Tolson C, Carter R, Coulter C, Huygens F, Hargreaves M: Isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) from household water and shower aerosols in patients with pulmonary disease caused by NTM. J Clin Microbiol 2013, 51:3006–3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hamilton LA, Falkinham JO: Aerosolization of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium abscessus from a household ultrasonic humidifier. J Med Microbiol 2018, 67:1491–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Glazer CS, Martyny JW, Lee B, Sanchez TL, Sells TM, Newman LS, Murphy J, Heifets L, Rose CS: Nontuberculous mycobacteria in aerosol droplets and bulk water samples from therapy pools and hot tubs. J Occup Environ Hyg 2007, 4:831–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ford ES, Horne DJ, Shah JA, Wallis CK, Fang FC, Hawn TR: Species-specific risk factors, treatment decisions, and clinical outcomes for laboratory isolates of less common nontuberculous mycobacteria in Washington State. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017, 14:1129–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jones MM, Winthrop KL, Nelson SD, Duvall SL, Patterson OV, Nechodom KE, Findley KE, Radonovich LJ, Samore MH, Fennelly KP: Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration. PLoS ONE 2018, 13:e0197976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lake MA, Ambrose LR, Lipman MCI, Lowe DM: “Why me, why now?” Using clinical immunology and epidemiology to explain who gets nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. BMC Med 2016, 14:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Prevots DR: Epidemiology of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial sputum positivity in patients with cystic fibrosis in the United States, 2010–2014. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018, 15:817–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study analyzed five years of data from a U.S. cystic fibrosis patient database to examine the relationship between NTM pulmonary infection and geographic, temporal, and demographic-related factors. The authors observed that the majority of pulmonary NTM disease was caused by either MAC or MAB. There was a higher prevalence of NTM pulmonary infection in certain geographic areas and demographics (e.g., study participants who were older and had a lower body mass index). These findings suggest that some U.S. states have higher rates of pulmonary NTM infection in cystic fibrosis patients and that certain regions and populations would benefit from increased screening.

- 69.Honda JR, Alper S, Bai X, Chan ED: Acquired and genetic host susceptibility factors and microbial pathogenic factors that predispose to nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Curr Opin Immunol 2018, 54:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamamoto K, Mukae H: Mycobacterial infection: TB and NTM—what are the roles of genetic factors in the pathogenesis of mycobacterial infection? In Clinical Relevance of Genetic Factors in Pulmonary Diseases. Edited by Kaneko T. Springer; Singapore; 2018:169–191. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brode SK, Campitelli MA, Kwong JC, Lu H, Marchand-Austin A, Gershon AS, Jamieson FB, Marras TK: The risk of mycobacterial infections associated with inhaled corticosteroid use. Eur Respir J 2017, 50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hamilton KA, Weir MH, Haas CN: Dose response models and a quantitative microbial risk assessment framework for the Mycobacterium avium complex that account for recent developments in molecular biology, taxonomy, and epidemiology. Water Res 2017, 109:310–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study is one of the first quantitative microbial risk assessments (QMRA) focused on MAC in engineered water systems. The authors compiled infectivity data from the literature for M. intracellulare, M. chimaera, and M. avium subsp. hominissuis and used the combined data and research on disease outcomes to propose several dose-response models. They identified areas of research needed to improve MAC QMRA.

- 73.Hamilton KA, Ahmed W, Toze S, Haas CN: Human health risks for Legionella and Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) from potable and non-potable uses of roof-harvested rainwater. Water Res 2017, 119:288–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bentham R, Whiley H: Quantitative microbial risk assessment and opportunist waterborne infections–are there too many gaps to fill? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perrott P, Turgeon N, Gauthier-Levesque L, Duchaine C: Preferential aerosolization of bacteria in bioaerosols generated in vitro. J Appl Microbiol 2017, 123:688–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gauthier-Levesque L, Bonifait L, Turgeon N, Veillette M, Perrott P, Grenier D, Duchaine C: Impact of serotype and sequence type on the preferential aerosolization of Streptococcus suis. BMC Res Notes 2016, 9:273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee BY, Kim S, Hong Y, Lee S-D, Kim WS, Kim DS, Shim TS, Jo K-W: Risk factors for recurrence after successful treatment for Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59:AAC.04577–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boyle DP, Zembower TR, Qi C: Relapse versus reinfection of Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease: Patient characteristics and macrolide susceptibility. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016, 13:1956–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brown-Elliott BA: Laboratory Diagnosis and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria In Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease: A Comprehensive Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Edited by Griffith DE. Humana Press; 2019:15–60. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang H, Bédard E, Prévost M, Camper AK, Hill VR, Pruden A: Methodological approaches for monitoring opportunistic pathogens in premise plumbing: A review. Water Res 2017, 117:68–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kirschner P, Rosenau J, Springer B, Teschner K, Feldmann K, Bottger EC: Diagnosis of mycobacterial infections by nucleic acid amplification: 18-month prospective study. J Clin Microbiol 1996, 34:304–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ngan GJY, Ng LM, Jureen R, Lin RTP, Teo JWP: Development of multiplex PCR assays based on the 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacer for the detection of clinically relevant nontuberculous mycobacteria. Lett Appl Microbiol 2011, 52:546–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sommerstein R, Rüegg C, Kohler P, Bloemberg G, Kuster SP, Sax H: Transmission of Mycobacterium chimaera from heater-cooler units during cardiac surgery despite an ultraclean air ventilation system. Emerg Infect Dis 2016, 22:1008–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tobler NE, Pfunder M, Herzog K, Frey JE, Altwegg M: Rapid detection and species identification of Mycobacterium spp. using real-time PCR and DNA-Microarray. J Microbiol Methods 2006, 66:116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hall L, Doerr KA, Wohlfiel SL, Roberts GD: Evaluation of the MicroSeq system for identification of mycobacteria by 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing and its integration into a routine clinical mycobacteriology laboratory. J Clin Microbiol 2003, 41:1447–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Adékambi T, Drancourt M: Dissection of phylogenetic relationships among 19 rapidly growing Mycobacterium species by 16S rRNA, hsp65, sodA, recA and rpoB gene sequencing. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2004, 54:2095–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee H, Park HJ, Cho SN, Bai GH, Kim SJ: Species identification of mycobacteria by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the rpoB gene. J Clin Microbiol 2000, 38:2966–2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Telenti A, Marchesi F, Balz M, Bally F, Bottger EC, Bodmer T: Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol 1993, 31:175–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Roth A, Reischl U, Streubel A, Naumann L, Kroppenstedt RM, Habicht M, Fischer M, Mauch H: Novel diagnostic algorithm for identification of mycobacteria using genus-specific amplification of the 16S-23S rRNA gene spacer and restriction endonucleases. J Clin Microbiol 2000, 38:1094–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fukushima M, Kakinuma K, Hayashi H, Nagai H, Ito K, Kawaguchi R: Detection and identification of Mycobacterium species isolates by DNA microarray. J Clin Microbiol 2003, 41:2605–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Butler WR, Guthertz LS: Mycolic acid analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography for identification of Mycobacterium species. Clin Microbiol Rev 2001, 14:704–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Buckwalter SP, Olson SL, Connelly BJ, Lucas BC, Rodning AA, Walchak RC, Deml SM, Wohlfiel SL, Wengenack NL: Evaluation of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for Identification of Mycobacterium species, Nocardia species, and other aerobic actinomycetes. J Clin Microbiol 2016, 54:376–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.