Abstract

The transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) channel is a mechanosensor in endothelial cells (EC) that regulates cyclic strain-induced reorientation and flow mediated nitric oxide production. We have recently demonstrated that TRPV4 expression is reduced in tumor EC and tumors grown in TRPV4KO mice exhibited enhanced growth and immature leaky vessels. However, the mechanism by which TRPV4 regulates tumor vascular integrity and metastasis is not known. Here, we demonstrate that VE-cadherin expression at the cell-cell contacts is significantly reduced in TRPV4-deficient tumor EC and TRPV4KO EC. In vivo angiogenesis assays with Matrigel of varying stiffness (700–900 Pa) revealed a significant stiffness-dependent reduction in VE-cadherin positive vessels in Matrigel plugs from TRPV4KO mice compared with WT mice, despite an increase in vessel growth. Further, syngeneic Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) tumor experiments demonstrated a significant decrease in VE-cadherin positive vessels in TRPV4KO tumors compared with WT. Functionally, enhanced tumor cell metastasis to the lung was observed in TRPV4KO mice. Our findings demonstrate that TRPV4 channels regulate tumor vessel integrity by maintaining VE-cadherin expression at cell-cell contacts and identifies TRPV4 as a novel target for metastasis.

Keywords: angiogenesis, mechanotransduction, stiffness, TRPV4, vascular integrity, VE-cadherin

1. Introduction

Tumor angiogenesis is characterized by abnormal and immature vessel growth. The tumor vasculature becomes leaky, resulting in irregular flow and increased interstitial pressure, as well as creates a low oxygen environment and stiff extracellular matrix (ECM). The culmination of these characteristics can form a barrier to chemo- and radio–therapies and aid in the extravasation and metastasis of tumor cells. Understanding the regulation of tumor vascular integrity is of great importance in the treatment of cancer [3, 4]. Vascular integrity of tumor vessels are regulated by junctional and adherent complexes that exist between the endothelial cells (ECs) themselves as well as between the ECs and surrounding pericytes [3, 4]. Vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin is an endothelial specific adherens junction protein that modulates EC barrier stability by interacting with catenins and the actin cytoskeleton. VE-cadherin also promotes vessel stabilization by inhibiting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR2) signaling [3, 4]. However, during the angiogenic process, the adhesive function of VE-cadherin decreases to aid in new vessel growth. Previous studies have demonstrated that ECM stiffness can contribute to angiogenesis by disrupting the EC monolayer as well as promoting permeability and EC sprouting [14, 15]. These findings suggest that ECM stiffness can influence VE-cadherin junctional complexes during angiogenesis, which has not been studied in detail

We have recently demonstrated that mechanosensitive ion channel transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) acts as mechanosensor in the endothelium and modulates EC reorientation in response to cyclic strain. We also demonstrated that TRPV4 expression is functionally downregulated in tumor ECs which corresponds to increased tumor growth and angiogenesis in TRPV4 knockout (TRPV4KO) mice. Importantly, tumors grown in TRPV4KO mice displayed immature, leaky vessels devoid of pericyte coverage. Pharmacological activation of TRPV4 was able to restore pericyte coverage and improve delivery of an anti-cancer agent, cisplatin [1, 23–25]. Although our previous work has demonstrated that TRPV4 modulates endothelial mechanosensitivity towards ECM stiffness, and the absence of TRPV4 results in immature tumor vessels, it is not yet known whether TRPV4 modulates VE-cadherin. In the present study, we demonstrate that TRPV4-dependent mechanotransduction regulates tumor angiogenesis and vessel integrity via modulation of VE-cadherin expression at endothelial cell-cell contacts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Normal endothelial cells (NEC) were obtained from murine dermal microvasculature,tumor endothelial cells (TEC) were isolated from transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate and TRPV4KO EC were isolated and cultured as previously described [7, 10, 25]. As previously described, the expression of EC markers and the absence of mesenchymal cell markers were confirmed prior to the use of these cells for experimentation [1, 7, 10].

2.2. Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS. Cells were blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) or serum containing media for 30–60 minutes and incubated for 60 minutes with primary antibodies VE-cadherin (1:100) (Santa Cruz). Cells were washed and incubated for 60 minutes with secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa-Fluor 488 (Invitrogen). Following the last round of washes, cells were mounted with hard set mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Lab). Images were captured using the Olympus IX81 Microscope and processed using NIH Image J software.

2.3. Animals

The experimental design(s) with the use of animals was approved by the Internal Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Northeast Ohio Medical University. All mice in this study were of C57BL/6 background (WT and TRPV4KO) (9–12 weeks of age; male) and were fed with ad libitum access to standard diet and water.

2.4. Matrigel Plug Assay

Mice were anesthetized with Ketamine/Xylazine cocktail according to their body weight. Phenol red free Matrigel (Corning) supplemented with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (0.25 µg/mL) (Corning), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (0.2 ng/mL) (R&D Systems), and heparin sulfate (0.5 µg/mL) (Sigma Aldrich) were subcutaneously injected into each flank. As previously described, various concentrations of microbial transglutaminase were added to alter stiffness[1, 10]. Matrigel plugs were excised after 2 weeks and processed for immunohistochemistry. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stained tissue was used to calculate the average number of nuclei per plug, using 10X images taken from 5 different fields of the Matrigel Plug. 20X images taken from 10–20 different fields were used to measure the area of the vessels following CD31 staining by tracing the vessels using ImageJ software. The data are reported as the area of endothelium per vessel in microns. VE-cadherin staining was used in conjunction with CD31 to visualize EC junctions and presented as percentage of VE-cadherin staining per vessel area. The data are reported as the percentage of VE-cadherin covered vessels.

2.5. Syngeneic Tumor Model

Mice were anesthetized with Ketamine/Xylazine cocktail according to their body weight. Two million Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) cells were subcutaneously injected into each flank. Tumor growth was monitored and tumor volumes were measure at 7, 14, and 21 days, as described previously [1]. After 21 days, mice were euthanized with Fatal Plus or anesthetized with Ketamine/Xylazine cocktail and tumor tissue was extracted and embedded in OCT (Tissue Tek) for immunohistochemistry.

2.6. Lung Metastasis

The lung tissue was collected after 21 days of tumor injection and fixed in 4% PFA for immunohistochemistry. H&E staining was performed and the total number of metastasis was calculated per lung. The data are reported as average number of metastases per lung.

2.7. Immunohistochemistry

Collected tumor tissue and Matrigel plugs were embedded in OCT (Tissue-Tek) and cryosectioned at 7–10 µM thickness on coated slides. Sections from both the central and peripheral regions of the tumors were used for staining. Frozen sections were stained with the following primary antibodies were added to the sections: CD31 (1:50) (Invitrogen), NG2 (1:200) (Millipore), and VE-cadherin (1:100) (Santa Cruz) and secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa-Fluor 488 or Alexa-Fluor 594 (Invitrogen) as described previously [1, 26–27]. Lung tissue was processed and embedded in paraffin and cut using a Leica microtome (Leica Biosystems) at 7–10 µM thickness on coated slides. Prior to staining, sections were deparaffinized in a 60°C oven and rehydrated in xylene and varying percentages of alcohol and then stained for H&E. Slides were then dehydrated in varying percentages of alcohol and xylene followed by mounting with DPX Mountant (Sigma Aldrich). Images were captured using either Olympus IX81 or Olympus BX61VS Microscope and processed using NIH Image J software.

2.8. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using Microsoft Excel. Analyses were completed using Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc testing. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. TRPV4 modulates VE-cadherin localization at cell-cell junctions

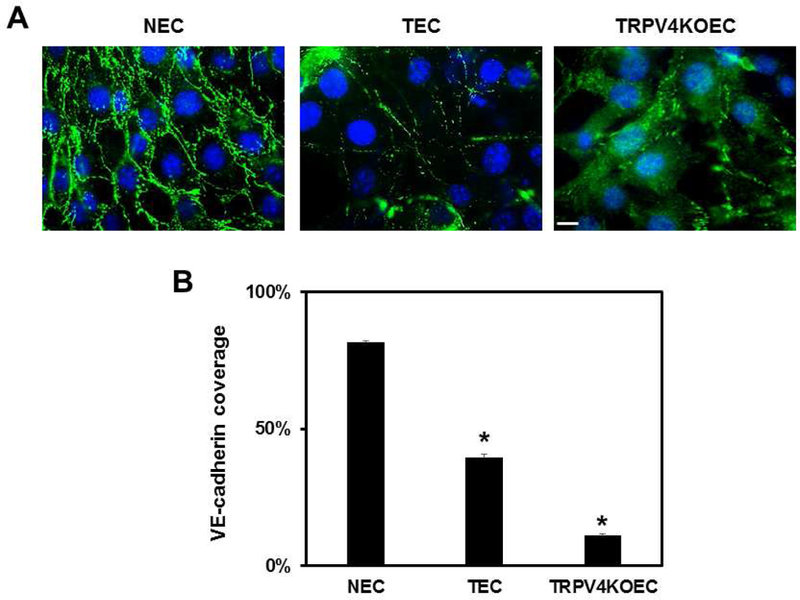

To investigate the mechanism by which TRPV4-mechanotransduction mediates vascular integrity, we first examined VE-cadherin localization in NEC, TRPV4-deficient TEC, and TRPV4KO EC. VE-cadherin staining in NECs was localized in the cell membrane and at the cell-cell contacts (Figure 1A). In TECs, VE-cadherin staining was weaker, displaying discontinued VE-cadherin along the cell junctions. Importantly, TRPV4KO ECs exhibited poor VE-cadherin staining at the cell-cell contacts and with a punctate pattern along the plasma membrane, with most of the staining in the cytoplasm. Quantitative analysis demonstrated that VE-cadherin covered 90% of the cell-cell contact area in NECs which was significantly decreased (p≤0.05) in TRPV4-deficient TEC (40%) and TRPV4KOEC (10%) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. TRPV4 modulates VE-cadherin localization at cell-cell junctions.

Representative immunofluorescence images of NEC, TEC, and TRPV4KO EC showing localization of VE-cadherin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). B) The graph represents the quantification of VE-cadherin coverage at the cell-cell junctions of NEC, TEC and TRPV4KO EC. Data represented are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. The significance was set at p≤0.05. Scale bar = 10 µm.

3.2. TRPV4 regulates angiogenesis in vivo in response to matrix stiffness

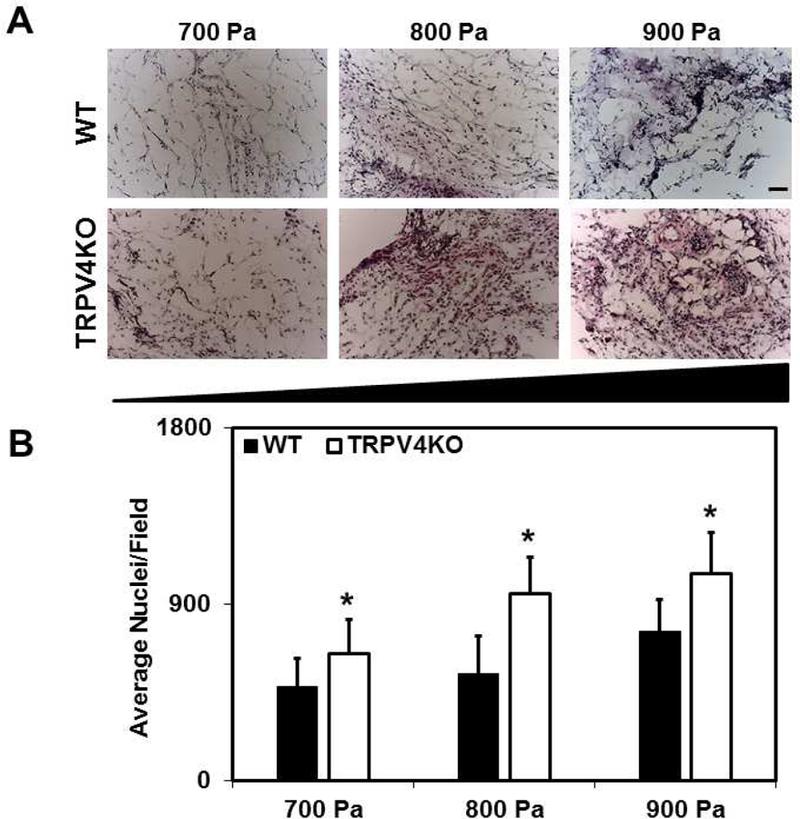

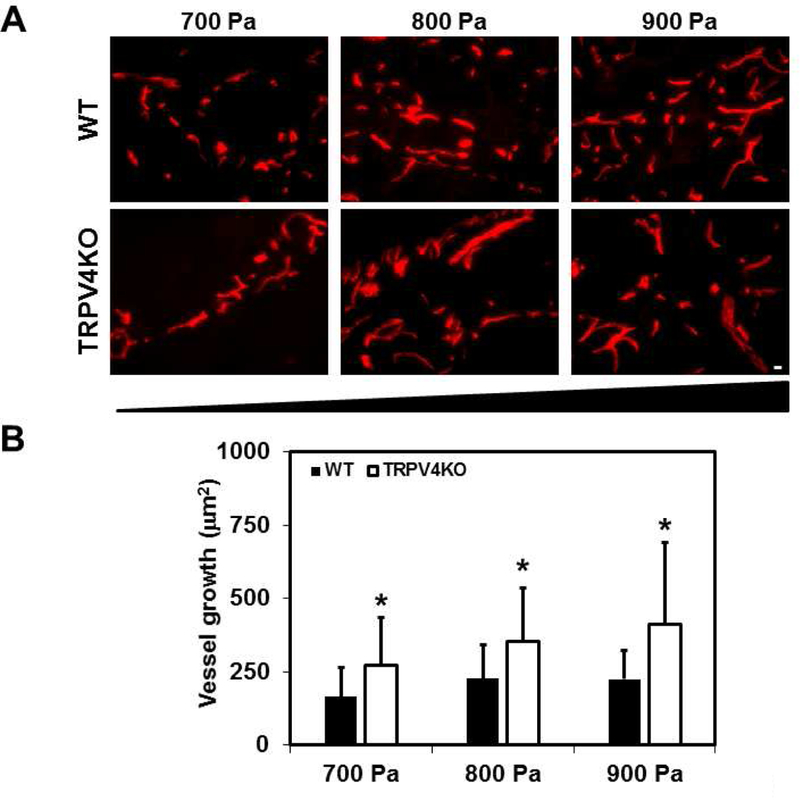

To unequivocally confirm that TRPV4-dependent mechanosensitivity mediates angiogenesis and vascular integrity in vivo, we employed a modified Matrigel plug assay by subcutaneously implanting Matrigel of varying stiffness (low to high: 700, 800 and 900 Pa) in WT and TRPV4KO mice (Figure 2A). Hematoxylin and Eosin staining revealed stiffness-dependent recruitment of cells into the Matrigel plugs. Quantitative analysis of the number of nuclei in Matrigel plugs isolated from WT mice exhibited a statistically non-significant increase between low and high stiffness (700 vs 900 Pa; 481 ± 144 vs 763 ± 171). In contrast, Matrigel plugs isolated from TRPV4KO mice displayed a significant stiffness-dependent increase (p≤0.05) in cell recruitment (Figure 2B) (700 vs 900 Pa; 644 ± 175 vs 1055 ± 212). To evaluate the vascular growth, Matrigel plug sections were then immunostained for EC marker, CD31 (Figure 3A). We found that vascular growth, measured as the area of endothelium, increased from low to intermediate stiffness, reaching a plateau at the highest stiffness in WT mice (700 vs 800 vs 900 Pa; 164 ± 98 vs 225 ± 114 vs 224 ± 100) (Figure 3B). However, TRPV4KO Matrigel plugs exhibited a continuous increase in vascular growth with increasing stiffness (700 vs 800 vs 900 Pa; 273 ± 160 vs 353 ± 180 vs 410 ± 280).

Figure 2. TRPV4 regulates angiogenesis in vivo in response to matrix stiffness.

A) Representative bright field images of H&E stained Matrigel plugs of varying stiffness (700–900 Pa) excised from WT and TRPV4KO mice. B) Quantitative analysis of the average number of nuclei per field in Matrigel plugs showing a significant (p≤0.05) stiffness-dependent (700–900 Pa) increase of nuclei in TRPV4KO plugs in comparison to WT. Data represented are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. The significance was set at p≤0.05. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Figure 3. Deletion of TRPV4 results in poor vessel integrity in response to varying matrix stiffness in vivo.

A) Representative immunofluorescence images (20X) showing CD31 (red) to visualize physiological angiogenesis in response to changing stiffness (700–900 Pa) in WT and TRPV4KO mice. B) Quantitative analysis of the area of endothelium per vessel (µm2) showing a significant (p≤0.05) stiffness-dependent (700–900 Pa) increase in vessel area in TRPV4KO Matrigel plugs. Data represented are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. The significance was set at p≤0.05. Scale bar = 10 µm.

3.3. TRPV4KO mice exhibit decreased VE-cadherin coverage in Matrigel plugs of varying stiffness

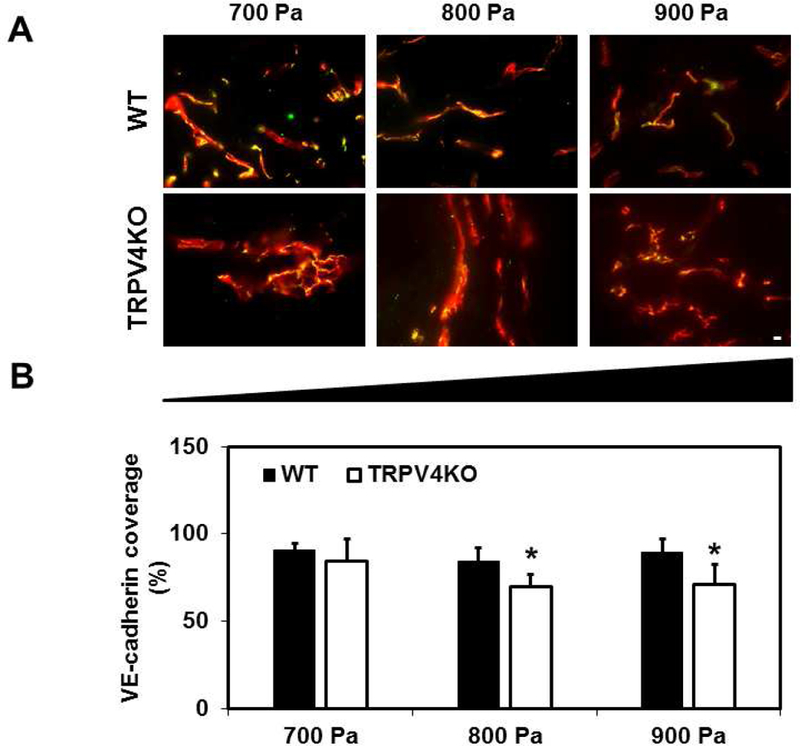

To determine if TRPV4 also plays a role in the final step of angiogenesis i.e., vessel maturation and stability, we evaluated EC junctional integrity in the Matrigel plugs by visualizing VE-cadherin (Figure 4A). Vasculature in WT Matrigel plugs displayed VE-cadherin that co-localized with CD31 along the majority of the newly formed vessels, indicating matured vascular networks. However, TRPV4KO Matrigel plugs exhibited many vessels, with gaps or weak VE-cadherin staining. Quantitative analysis of the percentage of VE-cadherin co-localization with CD31 revealed that the absence of TRPV4 resulted in a significant reduction (p≤0.05) at intermediate and high stiffness compared with WT (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. TRPV4KO mice exhibit decreased VE-cadherin coverage in Matrigel plugs of varying stiffness.

A) Representative immunofluorescence merged (yellow) images (20X) of CD31 (red) co-localized with adherens junction protein, VE-cadherin (green), in Matrigel plugs of different stiffness (700–900 Pa) among WT and TRPV4KO mice. B) Quantitative analysis of VE-cadherin covered vessels showing a significant (p≤0.05) reduction in endothelial junctions in TRPV4KO Matrigel plugs in comparison to WT Matrigel plugs. Data represented are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. The significance was set at p≤0.05. Scale bar = 10 µm.

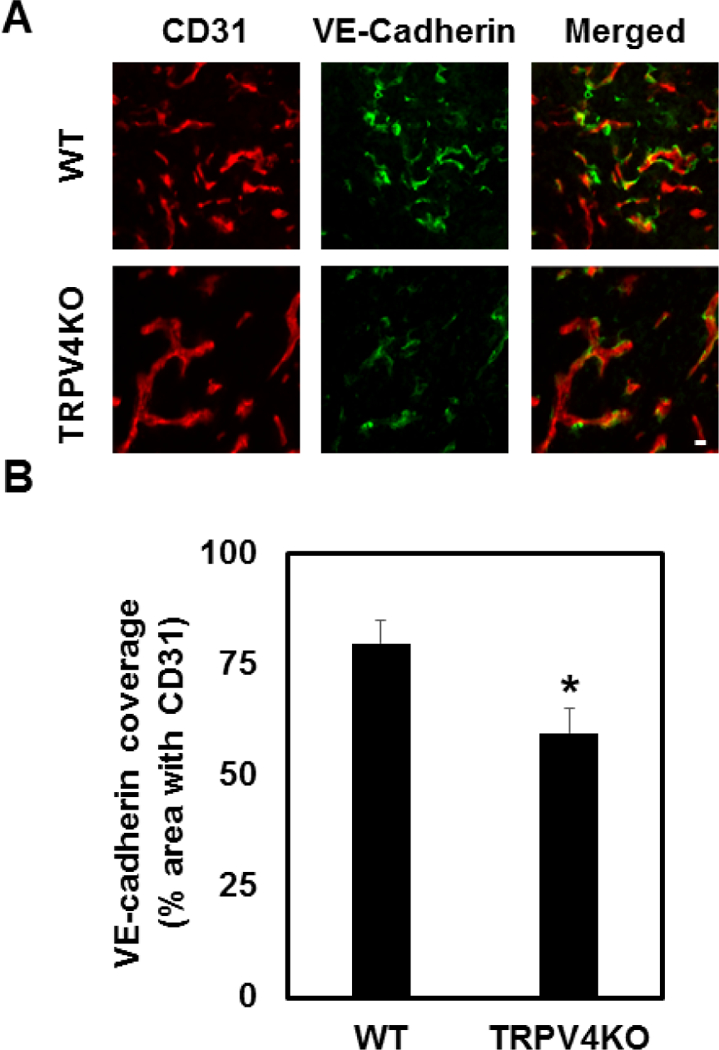

3.4. TRPV4 deletion reduces VE-cadherin expression and destabilizes tumor vessel integrity

Consistent with our previous findings [1, 24, 25], syngeneic tumor experiments revealed that tumor growth is increased in TRPV4KO mice compared with WT at 21 days (data not shown). We next stained tumor tissue with specific pericyte marker, NG2, which revealed decreased expression in TRPV4KO tumors, similar to α-SMA staining (Supplementary Figure.1 [1]) compared with WT. Quantitative analysis of the percentage of NG2 co-localization with CD31 in tumor vasculature revealed that the absence of TRPV4 resulted in a significant reduction (p≤0.05) of NG-2 containing vessels compared with WT tumors (Supplementary Figure.1). We then examined if this decrease in vascular integrity in the tumor vasculature is mediated by change in VE-cadherin. Immunohistochemistry analysis revealed that TRPV4KO mice exhibited decreased VE-cadherin expression in tumor vessels compared with WT (Figure 5A). Quantitative analysis revealed a significant decrease in VE-cadherin positive vessels (Figure 5B) in TRPV4KO tumors compared with WT tumors.

Figure 5. TRPV4 deletion reduces VE-cadherin expression and destabilizes tumor vessel integrity.

A) Vessel integrity was assessed with immunofluorescence in tumor sections from WT and TRPV4KO mice. Vessels were visualized by co-staining with CD31 (red) and cell-cell junctions were stained with VE-cadherin (green) [n≥3]. B) Quantitative analysis of VE-cadherin covered vessels showing a significant (p≤0.05) reduction in tumor vasculature in TRPV4KO mice in comparison to WT. Scale bar = 10 µm.

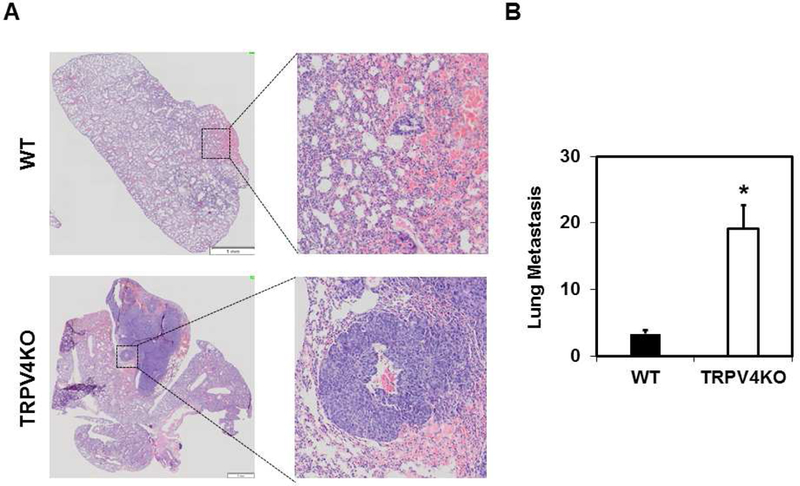

3.5. TRPV4KO tumors revealed increased metastasis to the lung

To determine the pathological significance of the above findings, we next asked if these tumor vessels facilitate metastasis of tumor cells. We collected and analyzed lung tissue at the endpoint (21 days) of the tumor experiments. Histological examination of the lung with H&E staining revealed large secondary tumors (metastasis foci) in TRPV4KO mice compared to small secondary lung tumors in WT mice following tumor growth(Figure 6A). Quantification of metastasis revealed approximately six times the number of secondary lung tumors in the TRPV4KO mice than WT mice (Figure 6B).

Fig.6. Absence of TRPV4 promotes lung metastasis of subcutaneous LLC tumor.

A) Brightfield images (2X and 20X) of H&E stained lung tissue collected from tumor bearing WT and TRPV4KO mice to visualize metastases (secondary tumor growth) in the lung. B) Quantitative analysis of average number of lung metastasis from WT and TRPV4KO mice with LLC tumors [n≥4]. Data represented are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. The significance was set at p≤0.05. Scale bar = 1 mm.

4. Discussion

The regulation of angiogenesis by mechanotransduction mechanisms is starting to receive greater attention with the recognition of the role mechanical factors play in cell physiology and pathology, including EC proliferation, migration, and lumen formation. Our previous studies have revealed the importance of TRPV4-mediated endothelial mechanosensing in angiogenesis in vitro [1]. In the present study, we confirmed, for the first time, that TRPV4 is undeniably mechanosensitive in vivo. We demonstrated that TRPV4 is a required mechanosensor for angiogenesis, in that TRPV4KO mice lacking this mechanosensor exhibit vessel malformations characterized by increased vascular growth and integrity in response to changes in ECM stiffness. Importantly, we demonstrated that when TRPV4 expression is deficient or absent, VE-cadherin accumulation at cell-cell contacts is reduced, leading to increased tumor metastasis.

ECM stiffness has been shown to influence EC growth and angiogenesis and in fact, stiffer matrices can cause an increase in angiogenic sprouts that are able to deeply invade into a 3D collagen matrix [8, 15]. While exact mechanosensitive receptors regulating this process are not well studied, TRPV4 is an appealing candidate and we have recently substantiated its role during angiogenesis, mainly in vitro [1]. To better understand and confirm TRPV4-mediated mechanosensing in angiogenesis to variations in ECM substrates in vivo, we examined Matrigel plugs of different stiffness grown in WT and TRPV4KO mice. We found that the intermediate substrate (800 Pa) is the optimum stiffness for vascular growth in WT mice which correlated with previous work by Ingber and colleagues that established a mechanotranscriptional mechanism by which ECM stiffness governs VEGFR2 gene promoter activity and expression to stimulate angiogenesis [17]. However, the identity of the proximal mechanosensor(s) involved remains unknown. The findings in this study clearly demonstrate that mechanosensitive ion channel TRPV4 regulates physiological angiogenesis in that the absence of TRPV4 results in stiffness-dependent increases in both vascular growth and disruption of vascular integrity. The enhanced vascular growth and malformed vascular network in TRPV4KO Matrigel plugs substantiates the previously identified role of TRPV4 as a negative regulator of angiogenesis since the absence of TRPV4 promotes proliferation and abnormal angiogenesis [1, 24, 25]. To our knowledge, this is the first report that establishes the mechanosensitive angiogenic role of TRPV4 in vivo.

Several studies have also demonstrated that stiffening ECM can contribute to angiogenesis by disrupting the EC monolayer as well as promoting permeability and EC sprouting [14, 15]. Moreover, when angiogenesis is in the final steps, vascular integrity must be achieved to ensure the stabilization and maintenance of the newly formed vasculature, thus, any malfunction in this process can result in serious outcomes, including tissue ischemia, edema, and hemorrhage [18]. Since TRPV4KO Matrigel plugs exhibited enhanced vascular growth in conjunction with malformed vascular architecture, we examined VE-cadherin vessel coverage. In connection with our findings, the absence of TRPV4 resulted in a significant decrease in VE-cadherin/CD31 co-localization at low, intermediate, and high stiffness, while WT Matrigel plugs presented with intact vessels at every stiffness. These findings could explain the increased vascular growth in TRPV4KO Matrigel plugs, not only because TRPV4KO EC display increased proliferation[1, 24], but also due to the fact that disrupted VE-cadherin can promote EC proliferation through VEGFR2 activation [18]. Overall, WT mice expressing TRPV4 can sense changes in substrate stiffness and ensure vessel stabilization. In contrast, TRPV4KO vessels exhibit weak VE-cadherin coverage, indicative of immature vessels, which suggests a role for TRPV4 in vascular integrity via VE-cadherin junctions. Indeed, our in vitro immunostaining experiments revealed that VE-cadherin expression at cell-cell junctions correlated with the functional expression of TRPV4 in EC. Decreased junctional localization of VE-cadherin in EC where TRPV4 is deregulated suggests that these EC lack viable connections with neighboring cells and their immediate environment, which could contribute to aberrant mechanosensing and abnormal angiogenesis. Our findings strongly suggest that TRPV4 is required for VE-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contacts and overall EC stability.

Solid tumor tissue is known to be stiffer than healthy tissue which has recently been found to directly affect the tumor vasculature [2, 16, 26]. The disruption of VE-cadherin at cell junctions can contribute to the abnormal vascular phenotype observed in solid tumors and has been identified as a major player in the stability of the tumor vasculature [5]. Moreover, downstream signaling of VE-cadherin has also been shown to mediate interactions between ECs and pericytes [6] and tumor vessels often exhibit discontinuous coverage of pericytes [11]. To date, only a few studies have identified targets that direct the maturation process to establish functional vessels, including apoptosis inhibitor Birc2 [19], miR-126 [9], small GTPase, R-Ras [20], and the endothelial adrenomedullin-RAMP2 system [22]. However, none of these targets directly involve mechanotransduction mechanisms, which is particularly important in the stiff tumor tissue. Here, we demonstrate the involvement of mechanosensor TRPV4 in the integrity of the tumor vasculature. More specifically, we demonstrated that the absence of TRPV4 resulted in reduced VE-cadherin stabilized junctions, poor pericyte coverage, and enhanced vascular permeability, the combination of which promoted the growth of secondary tumors, or metastasis, to the lung.

Many of the existing anti-angiogenesis therapies focusing on VEGF encounter modest clinical benefits due inactivation over time. This is predominantly due to acquired resistance, wherein tumors develop VEGF-independent growth factor pathways to promote tumor growth [12], or intrinsic resistance, where tumors are able to circumvent drug penetration, for example, due to high interstitial pressure [13]. Vascular normalization approaches recognize that vessel maturation and the prevention of vessel regression is an equally necessary objective for tumor vasculature, although there is still a need to identify specific targets [21]. In this study, we demonostrate that mechanosensitive ion channel TRPV4 plays a role in vascular integrity and functionality in both physiological and pathological angiogenesis and could be a growth factor alternative target for vascular normalization therapies as well as metastasis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

TRPV4 is a mechanosensitive ion channel highly expressed in endothelium.

TRPV4 functional expression is reduced in tumor endothelial cells.

TRPV4KO mice exhibit increased tumor growth, angiogenesis and vessel malformations compared to WT in response to subcutaneously implanted LLC.

TRPV4 deficiency or deletion reduced VE-cadherin at cell-cell contact in endothelial cells.

Absence of TRPV4 induced matrix stiffness-dependent increase in vascular growth and decrease in VE-cadherin positive vessels in Matrigel plugs.

TRPV4 deletion destabilized VE-cadherin junctions in tumor vasculature and promoted metastasis to lung in a syngeneic tumor model.

5. Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)-(R15CA202847 and R01HL119705) to CKT.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest:

None.

References

- [1].Adapala RK, Thoppil RJ, Ghosh K, Cappelli HC, Dudley AC, Paruchuri S, Keshamouni V, Klagsbrun M, Meszaros JG, Chilian WM, Ingber DE, Thodeti CK, Activation of mechanosensitive ion channel TRPV4 normalizes tumor vasculature and improves cancer therapy, Oncogene, 35 (2016) 314–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bordeleau F, Mason BN, Lollis EM, Mazzola M, Zanotelli MR, Somasegar S, Califano JP, Montague C, LaValley DJ, Huynh J, Mencia-Trinchant N, Negron Abril YL, Hassane DC, Bonassar LJ, Butcher JT, Weiss RS, Reinhart-King CA, Matrix stiffening promotes a tumor vasculature phenotype, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114 (2017) 492–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Carmeliet P, Angiogenesis in health and disease, Nat Med, 9 (2003) 653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Carmeliet P, Jain RK, Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis, Nature, 473 (2011) 298–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Corada M, Mariotti M, Thurston G, Smith K, Kunkel R, Brockhaus M, Lampugnani MG, Martin-Padura I, Stoppacciaro A, Ruco L, McDonald DM, Ward PA, Dejana E, Vascular endothelial-cadherin is an important determinant of microvascular integrity in vivo, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96 (1999) 9815–9820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dejana E, Giampietro C, Vascular endothelial-cadherin and vascular stability, Current opinion in hematology, 19 (2012) 218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dudley AC, Khan ZA, Shih SC, Kang SY, Zwaans BM, Bischoff J, Klagsbrun M, Calcification of multipotent prostate tumor endothelium, Cancer cell, 14 (2008) 201–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Edgar LT, Underwood CJ, Guilkey JE, Hoying JB, Weiss JA, Extracellular matrix density regulates the rate of neovessel growth and branching in sprouting angiogenesis, PloS one, 9 (2014) e85178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fish JE, Santoro MM, Morton SU, Yu S, Yeh RF, Wythe JD, Ivey KN, Bruneau BG, Stainier DY, Srivastava D, miR-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity, Developmental cell, 15 (2008) 272–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ghosh K, Thodeti CK, Dudley AC, Mammoto A, Klagsbrun M, Ingber DE, Tumor-derived endothelial cells exhibit aberrant Rho-mediated mechanosensing and abnormal angiogenesis in vitro, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105 (2008) 11305–11310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hashizume H, Baluk P, Morikawa S, McLean JW, Thurston G, Roberge S, Jain RK, McDonald DM, Openings between defective endothelial cells explain tumor vessel leakiness, The American journal of pathology, 156 (2000) 1363–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jain RK, Delivery of novel therapeutic agents in tumors: physiological barriers and strategies, Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 81 (1989) 570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kerbel RS, Tumor angiogenesis: past, present and the near future, Carcinogenesis, 21 (2000) 505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Krishnan R, Klumpers DD, Park CY, Rajendran K, Trepat X, van Bezu J, van Hinsbergh VW, Carman CV, Brain JD, Fredberg JJ, Butler JP, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Substrate stiffening promotes endothelial monolayer disruption through enhanced physical forces, American journal of physiology. Cell physiology, 300 (2011) C146–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee PF, Bai Y, Smith RL, Bayless KJ, Yeh AT, Angiogenic responses are enhanced in mechanically and microscopically characterized, microbial transglutaminase crosslinked collagen matrices with increased stiffness, Acta biomaterialia, 9 (2013) 7178–7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, Fong SF, Csiszar K, Giaccia A, Weninger W, Yamauchi M, Gasser DL, Weaver VM, Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling, Cell, 139 (2009) 891–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mammoto A, Connor KM, Mammoto T, Yung CW, Huh D, Aderman CM, Mostoslavsky G, Smith LE, Ingber DE, A mechanosensitive transcriptional mechanism that controls angiogenesis, Nature, 457 (2009) 1103–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Murakami M, Simons M, Regulation of vascular integrity, Journal of molecular medicine, 87 (2009) 571–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Santoro MM, Samuel T, Mitchell T, Reed JC, Stainier DY, Birc2 (cIap1) regulates endothelial cell integrity and blood vessel homeostasis, Nature genetics, 39 (2007) 1397–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sawada J, Urakami T, Li F, Urakami A, Zhu W, Fukuda M, Li DY, Ruoslahti E, Komatsu M, Small GTPase R-Ras regulates integrity and functionality of tumor blood vessels, Cancer cell, 22 (2012) 235–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Simons M, Angiogenesis: where do we stand now?, Circulation, 111 (2005) 1556–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tanaka M, Koyama T, Sakurai T, Kamiyoshi A, Ichikawa-Shindo Y, Kawate H, Liu T, Xian X, Imai A, Zhai L, Hirabayashi K, Owa S, Yamauchi A, Igarashi K, Taniguchi S, Shindo T, The endothelial adrenomedullin-RAMP2 system regulates vascular integrity and suppresses tumour metastasis, Cardiovascular research, 111 (2016) 398–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Thodeti CK, Matthews B, Ravi A, Mammoto A, Ghosh K, Bracha AL, Ingber DE, TRPV4 channels mediate cyclic strain-induced endothelial cell reorientation through integrin-to-integrin signaling, Circulation research, 104 (2009) 1123–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Thoppil RJ, Adapala RK, Cappelli HC, Kondeti V, Dudley AC, Gary Meszaros J, Paruchuri S, Thodeti CK, TRPV4 channel activation selectively inhibits tumor endothelial cell proliferation, Scientific reports, 5 (2015) 14257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Thoppil RJ, Cappelli HC, Adapala RK, Kanugula AK, Paruchuri S, Thodeti CK, TRPV4 channels regulate tumor angiogenesis via modulation of Rho/Rho kinase pathway, Oncotarget, 7 (2016) 25849–25861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tredan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF, Drug resistance and the solid tumor microenvironment, Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 99 (2007) 1441–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.