Abstract

Introduction Supporting and counselling couples with fertility issues prior to starting ART is a multidisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. The first German/Austrian/Swiss interdisciplinary S2k guideline on “Diagnosis and Therapy Before Assisted Reproductive Treatments (ART)” was published in February 2019. This guideline was developed in the context of the guidelines program of the German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) in cooperation with the Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (SGGG) and the Austrian Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (OEGGG).

Aims One third of the causes of involuntary childlessness are still unclear, even if the woman or man have numerous possible risk factors. Because the topic is still very much taboo, couples may be socially isolated and often only present quite late to a fertility center. At present, there is no standard treatment concept, as currently no standard multidisciplinary procedures exist for the diagnostic workup and treatment of infertility. The aim of this guideline is to provide physicians with evidence-based recommendations for counselling, diagnostic workup and treatment.

Methods This S2k guideline was developed on behalf of the Guidelines Commission of the DGGG by representative members from different professional medical organizations and societies using a structured consensus process.

Recommendations The first part of this guideline focuses on the basic assessment of affected women, including standard anatomical and endocrinological diagnostic procedures and examinations into any potential infections. Other areas addressed in this guideline are the immunological workup with an evaluation of the patientʼs vaccination status, an evaluation of psychological factors, and the collection of data relating to other relevant factors affecting infertility. The second part will focus on explanations of diagnostic procedures compiled in collaboration with specialists from other medical specialties such as andrologists, human geneticists and oncologists.

Key words: infertility, preconception counselling, endometriosis, PCOS, guideline

I Guideline Information

Guideline program of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG

For information on the guidelines program, please refer to the end of the guideline.

Citation format

Diagnosis and Therapy Before Assisted Reproductive Treatments. Guideline of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S2k Level, AWMF Register Number 015-085, February 2019) – Part 1, Basic Assessment of the Woman. Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2019; 79: 1278–1292

Guideline documents

The complete long version together with a slide version of this guideline and a list of the conflicts of interests of all authors involved are available in German on the homepage of the AWMF: https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/015-085.html

Guideline authors

Table 1 Lead author and/or coordinating lead author of the guideline.

| Author | AWMF professional society |

|---|---|

| Prof. Dr. B. Toth | German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe e. V.] (DGGG) Austrian Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics [Österreichische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe] (ÖGGG) German Society for Gynecological Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologische Endokrinologie und Fortpflanzungsmedizin] (DGGEF) |

Table 2 Contributing guideline authors.

| Author Mandate holder |

DGGG working group (AG)/AWMF/non-AWMF professional society/organization/association |

|---|---|

| Dr. Dunja Maria Baston-Büst | Expert |

| Prof. Dr. Hermann M. Behre | German Society for Andrology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Andrologie] (DGA) |

| Prof. Dr. Michael Bohlmann | Immunology Working Group [Arbeitsgemeinschaft] in the DGGG |

| Prof. Dr. Kai Bühling | German Society for Womenʼs Health [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Frauengesundheit] (DGF) |

| Prof. Ralf Dittrich | German Society for Endocrinology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Endokrinologie], (DGE) |

| Dr. Maren Goeckenjan | Steering committee |

| Prof. Dr. Katharina Hancke | German Society for Reproductive Medicine [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Reproduktionsmedizin] (DGRM) |

| Prof. Dr. Alexandra Bielfeld | Expert |

| Prof. Dr. Sabine Kliesch | German Society for Urology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie] (DGU) |

| Prof. Dr. Frank-Michael Köhn | German Society for Andrology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Andrologie] (DGA) |

| Prof. Dr. Jan Krüssel | German Society for Reproductive Medicine (DGRM) |

| PD Dr. Ruben Kuon | Expert |

| Dr. Jana Liebenthron | Steering committee |

| Prof. Dr. Frank Nawroth | Expert |

| PD. Dr. Verena Nordhoff | German Society of Human Reproductive Biology [Arbeitsgemeinschaft Reproduktionsbiologie des Menschen] (AGRBM) |

| Univ.Prof. h. c. Dr. Germar-Michael Pinggera | Austrian Society for Urology [Österreichische Gesellschaft für Urologie] (ÖGU) |

| Prof. Dr. Nina Rogenhofer | German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (DGGG), Immunology Working Group in the DGGG |

| Prof. Dr. Sabine Rudnik-Schöneborn | German Society for Human Genetics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Humangenetik e. V.] (GfH) Austrian Society for Human Genetics [Österreichische Gesellschaft für Humangenetik] (ÖGH) |

| Prof. Dr. Hans-Christian Schuppe | German Society for Andrology (DGA) |

| Prof. Dr. Andreas Schüring | Expert |

| Prof. Dr. Vanadin Seifert-Klauss | German Society for Endocrinology (DGE) |

| Prof. Dr. Thomas Strowitzki | German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) |

| Prof. Dr. Frank Tüttelmann | German Society for Andrology (DGA) |

| Dr. Kilian Vomstein | Steering committee |

| Prof. Dr. Ludwig Wildt | Austrian Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (OEGGG) |

| Prof. Dr. Tewes Wischmann | German Society for Fertility Counselling [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinderwunschberatung] (BKiD) |

| PD. Dr. Dorothea Wunder | Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (SGGG) |

| Prof. Dr. Johannes Zschocke | German Society for Human Genetics (GfH) Austrian Society for Human Genetics (ÖGH) |

PD Dr. Helmut Sitter (AWMF-certified guideline advisor/moderator) moderated the guideline.

II Guideline Application

Purpose and objectives

The purpose of this guideline is to standardize diagnosis and treatment prior to ART based on the available evidence in the current literature and national/international guidelines.

The guideline was developed using common, consistent definitions and based on objectivized evaluation modalities and standardized diagnostic and therapeutic protocols.

Targeted areas of patient care

Outpatient care

Primary care and specialist medical care

Target user groups/target audience

The recommendations of the guideline are aimed at gynecologists, general practitioners and specialists working in the fields of urology, andrology, human genetics, psychotherapy, clinical pathology, hemostaseology, and internal medicine as well as members of other professions who provide care to couples with fertility issues.

Additional targeted groups (for information purposes):

Nursing staff

Family members

Adoption and period of validity

The validity of this guideline was confirmed by the executive boards/heads of the participating professional societies/working groups/organizations/associations as well as by the boards of the DGGG and the DGGGG Guidelines Commission and of the SGGG and the OEGGG in January 2019 and was thus approved in its entirety. This guideline is valid from 1st February 2019 through to 31st January 2022. Because of the contents of this guideline, this period of validity is only an estimate.

III Methodology

Basic principles

The method used to prepare this guideline was determined by the class to which this guideline was assigned. The AWMF Guidance Manual (version 1.0) has set out the respective rules and requirements for different classes of guidelines. Guidelines are differentiated into lowest (S1), intermediate (S2) and highest (S3) class. The lowest class is defined as a set of recommendations for action compiled by a non-representative group of experts. In 2004, the S2 class was divided into two subclasses: a systematic evidence-based subclass (S2e) and a structural consensus-based subclass (S2k). The highest S3 class combines both approaches.

This guideline was classified as: S2k

Grading of recommendations

Grading of evidence based on the systematic search, selection, evaluation and synthesis of the evidence base followed by a grading of the evidence is not envisaged for S2k-level guidelines. The respective individual Statements and Recommendations are only differentiated by syntax, not by symbols ( Table 3 ).

Table 3 Grading of recommendations.

| Strength of recommendation | Syntax |

|---|---|

| strong recommendation, highly binding | must/must not |

| regular recommendation, moderately binding | should/should not |

| open recommendation, not binding | may/may not |

Statements

Expositions or explanations of specific facts, circumstances or problems without any direct recommendations for action included in this guideline are referred to as “Statements”. It is not possible to provide any information about the grading of evidence for these Statements.

Achieving consensus and strength of consensus

At structured NIH-type consensus-based conferences (S2k/S3 level), authorized participants attending the session vote on draft Statements and Recommendations. The process is as follows. A Recommendation is presented, its contents are discussed, proposed changes are put forward, and finally, all proposed changes are voted on. If a consensus has not been achieved (> 75% of votes), there is another round of discussions, followed by a repeat vote. Finally, the extent of consensus is determined based on the number of participants. ( Table 4 ).

Table 4 Classification showing the extent of agreement for consensus-based decisions.

| Symbol | Strength of agreement | Extent of agreement in percent |

|---|---|---|

| +++ | Strong consensus | > 95% of participants agree |

| ++ | Consensus | > 75 – 95% of participants agree |

| + | Majority agreement | > 50 – 75% of participants agree |

| – | No consensus | < 51% of participants agree |

Expert consensus

As the name already implies, this refers to consensus decisions taken with regard to Recommendations/Statements without a prior systematic search of the literature (S2k) or for which evidence is lacking (S2e/S3). The term “expert consensus” (EC) used here is synonymous with terms used in other guidelines such as “good clinical practice” (GCP) or “clinical consensus point” (CCP). The strength of the recommendation is graded as previously described in the chapter “Grading of recommendations”, i.e., purely semantically (“must”/“must not” or “should”/“should not” or “may”/“may not”) and without the use of symbols.

IV Guideline

1 Introduction

Supporting and counselling couples with fertility issues is a multidisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutic challenge.

Women often first approach their GP or gynecologist while men usually consult an andrologist or urologist. As there are no multidisciplinary guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of infertility, currently no standard concept exists for the appropriate diagnostic workup when examining these couples.

The aim of this guideline is to provide the treating physician with evidence-based recommendations on counselling, diagnostic workup and treatment. The first part of this guideline focuses on the basic assessment of affected women, while the second part discusses the diagnostic workup together with specialists from other medical specialties such as andrologists, human geneticists and oncologists. Because of the large number of topics discussed in the guideline, this short version was split into two parts. This first part focuses on the basic diagnostic workup for affected women, while the second part will discuss the workup together with specialists from other medical specialties such as andrologists, human geneticists and oncologists.

2 Prevalence, Epidemiology and Definition

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) defines infertility as follows: the failure to achieve a successful pregnancy after 12 months or more of appropriate, timed, unprotected intercourse 20 , 21 .

Primary infertility is differentiated from secondary infertility as, in the latter, the current partners have already had one successful pregnancy. Approximately 80% of couples become pregnant over a period of 12 months with regular unprotected intercourse, meaning that further diagnostic evaluation is necessary in around 5 – 15% of couples. Because of the age-related reduction in fertility, further diagnostic evaluations should already be carried out after 6 months in couples over the age of 35 years, followed by an intervention where necessary, while the interval to treatment can be longer for younger couples. Overall, older women have an increased risk of complications of pregnancy such as gestational diabetes, preeclampsia and placenta previa and have a higher rate of cesarean sections, and women aged > 40 years wanting to have children should be informed of this during the first consultation 23 .

The basic gynecological workup includes a detailed evaluation of the patientʼs medical history including questions about the patientʼs menstrual cycle (age at first menstruation, interval between periods, pain prior to, during or after menstruation), about general gynecological diseases such as salpingitis, vulvovaginitis, dysmenorrhea/endometriosis, complications and the course of previous pregnancies (miscarriage, small for gestational age [SGA], preeclampsia, etc.), previous gynecological operations, the womanʼs current vaccination status and a gynecological examination. This should include vaginal, cervical and uterine examinations (Pap smear, poss. bacterial smear test), the exclusion of infections and vaginal/uterine malformations (septate vagina/septate uterus, duplex uterus). The patient should also have the results of recent cancer screening tests (screening undertaken no more than 12 months previously).

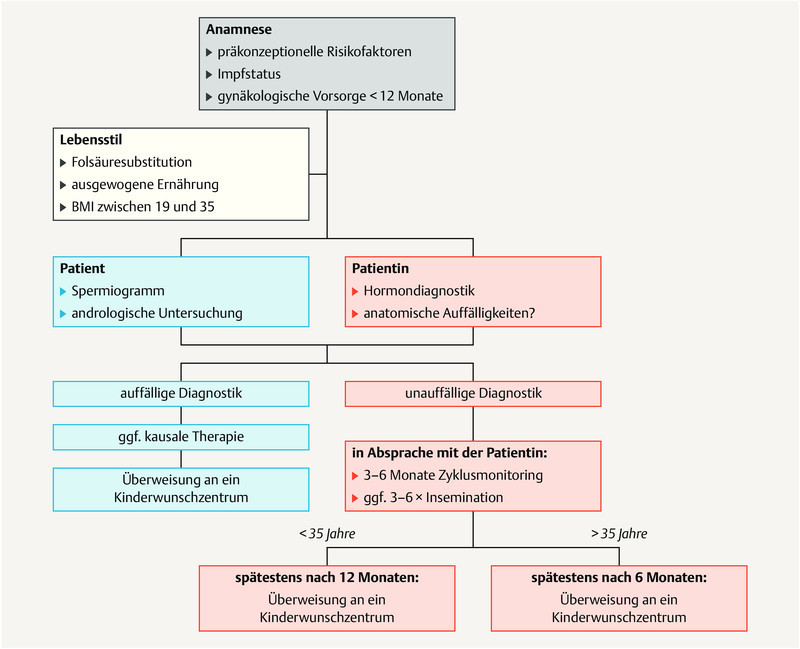

Depending on how long the patient has tried to become pregnant and the patientʼs age, the patient should be referred to a center for reproductive medicine as soon as possible ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic workup and timing of fertility evaluation. [rerif]

3 Diagnosis and Treatment Prior to Assisted Reproductive Medical Treatment

3.1 Diagnostic workup and treatment of relevant factors influencing infertility

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.1.E1 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| When taking the womanʼs medical history, the issue of (fertility-) relevant risk factors (e.g., age, smoking, alcohol, eating disorders, drug abuse, intensive physical exercise) must be explicitly raised during the consultation. The possible negative impact of these factors on the treatment outcome and the potential damage to gametes and the embryo must be pointed out. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.1.E2 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| During the first consultation with a couple wanting to have children, it must be pointed out to them that both a BMI > 30 kg/m 2 and a BMI < 19 kg/m 2 are associated with ovulation disorders which can lead to infertility. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.1.E3 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Before starting fertility treatment, women must be informed about the necessity of folic acid substitution with 400 µg folic acid. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.1.E4 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The obligatory folic acid substitution may take the form of a multivitamin preparation which additionally includes 20 µg vitamin D. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.1.E5 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| If the fertility disorder is related to the patientʼs behavior, appropriate counseling or psychotherapy should be recommended (e.g. psychotherapy for eating disorders, addiction counseling, psychosocial fertility counseling). | |

3.2 Sexuality and sexual disorders

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.2.E6 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| When examining the patient for possible fertility disorders, the patient should be specifically asked about sexual problems in the coupleʼs relationship. Changes in sexual experience or behavior during the subsequent course of treatment should be explicitly raised. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.2.E7 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| In cases where the couple themselves consider their sexual experience and behavior as requiring treatment, sexual therapy should be recommended. | |

3.3 Psychological factors

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.3.E8 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The use of screening tools to identify psychologically vulnerable couples may be considered. The couple should be offered a psychosomatic diagnosis; routine psychopathological diagnosis is not required. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.3.E9 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Currently, it is not generally recommended that the couple be referred for psychosocial counseling or psychotherapy, unless there are behavioral reasons for the fertility disorder or the patient has a mental illness (as defined in the ICD10) which requires treatment. | |

3.4 Diagnosis and treatment of congenital and acquired genital anomalies

3.4.1 Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the patientʼs detailed medical history, gynecological examination (speculum examination and bimanual palpation), imaging procedures or invasive surgical methods.

3.4.1.1 Sonography

2D vaginal sonography is a reliable imaging technique to show the shape and size of the uterus and ovaries and their respective pathologies. 3D vaginal sonography is used to visualize the cavity of the uterus and is a reliable method to assess uterine septa, fibroids and polyps.

In the ESHRE/ESGE meta-analysis 12 , 2D vaginal sonography used to evaluate genital malformations had a sensitivity of 67.3% (95% CI: 51.0 – 83.7) and a specificity of 98.1% (95% CI: 96.0 – 100) compared to hysteroscopy/laparoscopy (HSC/LSC). In the same meta-analysis, 3D vaginal sonography was reported to be superior to 2D sonography, with a sensitivity of 98.3% (95% CI: 95.6 – 100) and a specificity of 99.4% (95% CI: 98.4 – 100) compared to hysteroscopy/laparoscopy.

3.4.1.2 Hysterosalpingo contrast sonography (HyCoSy)

HyCoSy is non-invasive method based on the intracervical administration of a contrast medium, and it may be used in addition to sonography to obtain images of the cervix, the cavity of the uterus (septa, polyps, fibroids) and the uterine tubes. The disadvantage of this method is that the assessment is investigator-dependent and the validity of the findings may be reduced by artifacts (bowel loops, gas).

Compared to HSC/LSC, the ESHRE/ESGE meta-analysis reported a sensitivity of 95.8% (95% CI: 91.1 – 100) and a specificity of 97.4% (95% CI: 94.1 – 100) for HyCoSy 12 .

3.4.1.3 Hysteroscopy (HSC)

HSC provides information about cervical and intracavitary malformations and the ostia of the uterine tubes. The advantage of this method is that it simultaneously offers an opportunity to carry out surgical corrections. The disadvantage is that it provides no information about the thickness of the myometrium and the external contours of the uterus.

3.4.1.4 Laparoscopy (LSC)

A combination of LSC and HSC is still considered the gold standard. But as these procedures are invasive and non-invasive diagnostic methods have greatly improved in recent years, the appropriate procedure must be carefully weighed up on a case-by-case basis.

3.4.2 Diagnosis of congenital genital anomalies

This guideline only discusses selected common malformations: septate/subseptate uterus (ESHRE/ESGE Class 2, AFS Class V), bicornuate/duplex uterus (ESHRE/ESGE Class 3, AFS Class IV/III) and unicornuate unicollis uterus (ESHRE/ESGE Class 4, AFS Class II).

For detailed diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations on other more complex malformations, readers are explicitly referred to the German-language AWMF guideline on female genital malformations (No. 015-052).

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.4.E10 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| To exclude congenital malformations, vaginal sonography must be carried out after the gynecological examination. If there is a suspicion of congenital malformation, vaginal 3D sonography and/or hysteroscopy, poss. in combination with laparoscopy, must be carried out. | |

3.4.3 Diagnosing acquired genital anomalies

3.4.3.1 Diagnosing fibroids

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.4.E11 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Vaginal sonography must be used to diagnose fibroids. | |

3.4.3.2 Diagnosing polyps and intrauterine adhesions

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.4.E12 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Hysteroscopy must be carried out if there is a suspicion of intrauterine polyps and/or adhesions. | |

3.4.3.3 Diagnosing tubal factors

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.4.E13 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| If an investigation of tubal patency is indicated, the method used must either be laparoscopy with chromopertubation or hysterosalpingo contrast sonography (HyCoSy). If laparoscopy is used to investigate tubal patency, it must be combined with a hysteroscopy. | |

3.4.4 Treatment of congenital genital anomalies

It is generally assumed that around 3% of women with primary infertility and 5 – 10% of women who suffer recurrent spontaneous miscarriage have a congenital genital malformation 1 . Surgical treatment of a diagnosed uterine malformation is not the main approach for asymptomatic women with primary infertility. However, if surgical treatment is indicated, the top priority is to establish uterine functionality and anatomy.

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.4.E14 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Hysteroscopic septum dissection should be carried out in women with septate/subseptate uterus before starting fertility treatment. Bicornuate uterus, duplex uterus and unicornuate unicollis uteri must not be surgically corrected in women with primary infertility. | |

3.4.5 Treatment of acquired genital anomalies

3.4.5.1 Treatment of fibroids

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.4.E15 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Submucosal fibroids (FIGO type 0 and 1) must be removed with hysteroscopy before starting fertility treatment. Intramural and subserous fibroids may be removed laparoscopically. | |

3.4.5.2 Treatment of polyps and intrauterine adhesions

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.4.E16 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Intrauterine polyps and adhesions should be removed with hysteroscopy. Adhesion prophylaxis may be carried out postoperatively. | |

3.4.5.3 Treatment of tubal factors

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.4.E17 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy or laparoscopic proximal tubal occlusion must be carried out in women with hydrosalpinx before starting ART. | |

3.5 Diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.5.E18 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| A laparoscopic diagnostic workup with histological confirmation, chromopertubation and hysteroscopy should be carried out in infertile women with a suspicion of endometriosis. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.5.E19 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Peritoneal foci of endometriosis should be surgically removed. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.5.E20 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| In cases with ovarian endometriosis, the risk of the procedure reducing ovarian reserve must be weighed up against the possible benefits of surgery and discussed preoperatively with the patient. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.5.E21 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Surgical resection may be used to treat deep infiltrating endometriosis. | |

3.6 Infectious factors

The legally required screening parameters before starting ART which are also defined in numerous guidelines 4 , 6 , 7 , 8 are not the subject of the following recommendations.

3.6.1 Diagnosing infectious factors

3.6.1.1 Diagnosing vaginal infections

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.6.E22 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Screening for infectious disease (bacterial vaginosis) using vaginal smears must not be carried out in asymptomatic women. | |

3.6.1.2 Acute chlamydia infection

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.6.E23 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Screening for acute chlamydia infection must not be carried out in asymptomatic women. | |

3.6.1.3 Chronic chlamydia infection

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.6.E24 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Screening for chronic chlamydia infection (chlamydial serology) may be carried out. | |

3.6.2 Treatment of infectious factors

3.6.2.1 Treatment of vaginal infections

Clindamycin or metronidazole are recommended to treat bacterial vaginosis 19 . Co-treatment of the affected womanʼs male partner has no impact on the rate of recurrence of bacterial vaginosis 3 .

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.6.E25 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Prophylaxis against infection must not be carried out if there are no clinical symptoms and no confirmation of the pathogen. | |

3.7 Endocrine factors of female infertility

Endocrine disorders in women are the most common causes of infertility. Functional disorders of endocrine systems such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis or prolactin production lead to disturbances in oocyte maturation, ovulation and implantation. A rational, cost-effective workup of endocrine factors and targeted therapy to improve ovulation rates and implantation must be done before starting ART.

3.7.1 Diagnosing endocrine factors

3.7.1.1 Basic diagnostic workup for endocrine factors

The diagnostic confirmation of hormonal disorders consists of an initial basic diagnostic workup, which may then be expanded further with step-by-step diagnostic procedures in the event of suspicious findings. In addition to the hormonal diagnostic workup, vaginal ultrasound is done to evaluate the ovary, determine the antral follicle count (AFC) and obtain images of the uterus with a particular focus on the thickness of the endometrium. Single serum progesterone measurement in the luteal phase to confirm or exclude ovulation is carried out in the second half of the menstrual cycle, if possible 7 days after clinical assumption of ovulation 13 . The aim of the basic diagnostic workup is to evaluate hormonal regulation of the menstrual cycle and confirm ovulation.

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E26 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| The basic hormonal diagnostic workup in women with infertility should include the determination of LH, FSH, prolactin, testosterone, DHEAS, SHBG, free androgen index, estradiol and AMH on days 3 – 7 of the menstrual cycle (or when there is no follicle with a diameter > 10 mm). This basic diagnostic workup is accompanied by vaginal ultrasound to evaluate the functional status of the internal genitalia and by a diagnostic evaluation of the thyroid gland. Additional step-by-step diagnostic procedures are carried out based on suspicious findings (e.g., evaluation of androgens, androstenedione, 17-OH progesterone, HOMA-IR). | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E27 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Progesterone determination may be carried out around 7 days after the assumed ovulation (e.g., on day 21 of a 28-day cycle) to determine the ovulatory cycle. | |

3.7.1.2 Special endocrine workups

The differential evaluation of underlying disorders in patients with fertility issues and suspicious findings during the basic diagnostic workup provides the basis for targeted hormone therapy ( Table 5 ).

Table 5 Disorders of ovarian function and diagnostic criteria.

| Ovarian function disorder | Symptoms | Diagnostic lab workup | Vaginal ultrasound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luteal phase insufficiency | Short luteal phase (< 12 days after ovulation) premenstrual spotting |

LH, E2, progesterone approx. 7 days after ovulation Decreased midluteal progesterone levels |

Exclude ovarian cysts |

| Oocyte maturation disorder | Short or extended follicular phase, poss. luteal insufficiency or anovulation | Delayed or absent rise in estradiol levels during menstrual cycle, decreased luteal progesterone levels | Non-linear follicular maturation Endometrium < 7 mm |

| Hyperprolactinemic ovarian insufficiency | Changes in menstrual cycle length, from oligoovulation to amenorrhea, poss. accompanied by hypothyroidism | Prolactin, TSH (if levels are several times the normal level, cranial MRI) | – |

| Hyperandrogenic ovarian insufficiency/PCO syndrome | From oligoovulation to amenorrhea, hypermenorrhea, clinical signs of hyperandrogenemia, poss. obesity | Step-by-step diagnosis

|

Ovaries typical for PCOS Exclude ovarian cysts, evaluate the endometrium |

| Hypogonadotropic/hypothalamic ovarian insufficiency | Menstrual cycle length disorders, amenorrhea, often underweight | FSH, LH, estradiol, normal AMH | Thin endometrium, ovaries with normal AFC |

| Hypergonadotropic ovarian insufficiency | Menstrual cycle length disorders, amenorrhea | Increased FSH, decreased LH or estradiol, low AMH | Thin endometrium, ovaries with low AFC |

3.7.1.3 Primary/secondary amenorrhea

Causes of primary amenorrhea are, in the first instance, genetic anomalies, anatomical malformations or acquired disorders of ovarian function after gonadotoxic treatment in childhood.

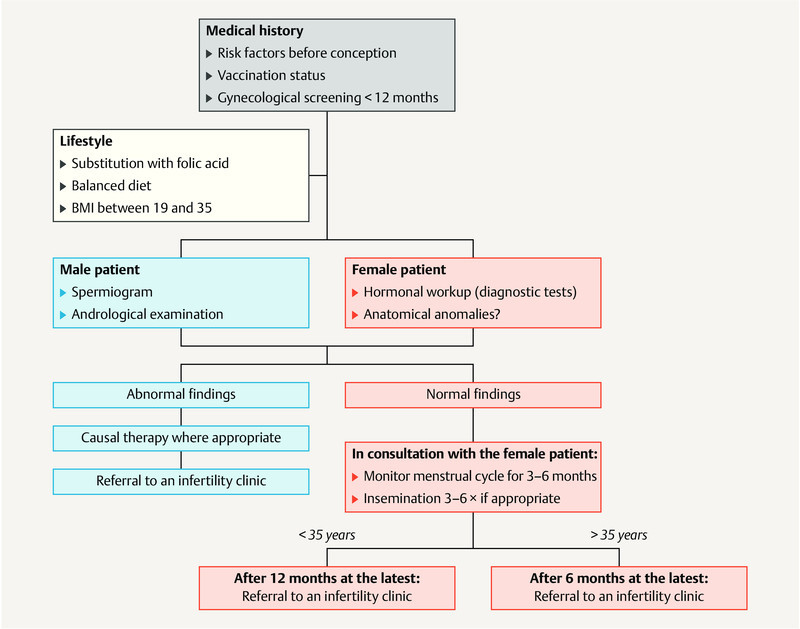

Because of their absent or delayed pubertal development, by the time the patient would like to have children, the causes of infertility have usually already been determined. A useful algorithm to determine the causes of primary amenorrhea must focus on pubertal development, gonadotropic regulation and whether the patient has a uterus, while the investigation into amenorrhea in infertile women must include additional differential diagnoses ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Differential diagnostic approach for amenorrhea. [rerif]

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E28 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The first diagnostic step to investigate amenorrhea must consist of a pregnancy test. After carrying out a basic diagnostic endocrine workup, subsequent examinations to obtain a differential diagnosis must be based on symptoms. | |

3.7.1.4 PCOS/hyperandrogenemia

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E29 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| If there is a suspicion of polycystic ovary syndrome, the first step must consist of a clinical evaluation of the diagnostic criteria for PCOS: according to the Rotterdam criteria, they include abnormal periods with oligoovulation or anovulation, clinical and/or lab-confirmed hyperandrogenemia as well as typical PCO sonomorphology. | |

3.7.1.5 Adrenogenital syndrome/congenital adrenal hyperplasia

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E30 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| If there is a suspicion of AGS (detailed endocrine diagnostic workup or ACTH test), molecular-genetic examinations must be carried out. If AGS/late-onset AGS is confirmed in the partner, genetic counselling must be provided. | |

3.7.1.6 AMH, age and oocyte quality

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E31 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The AMH value may be determined to estimate current ovarian activity and responsiveness to hormone stimulation treatment. It must not be used to evaluate fertility. | |

3.7.1.7 Anovulatory cycle and luteal phase insufficiency

In summary, at present there is no single, clinically valid laboratory test which can diagnose luteal phase insufficiency and differentiate between fertile and infertile women 5 .

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E32 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| If the length of the menstrual cycle is unremarkable and regular, no biopsy of the endometrium to investigate the luteal phase must be carried out. | |

3.7.1.8 Diabetes mellitus

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E33 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Determination of HbA 1c must be carried out in diabetic women prior to conception. Diabetic women must only have a planned pregnancy when blood sugar levels are near normal (HbA 1c < 6.5%). | |

3.7.1.9 Thyroid dysfunction

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E34 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| TSH levels must be determined in all women wanting to have children. If the TSH value is > 2.5 mU/L, the level of anti-thyroid antibodies should be determined. | |

3.7.2 Treatment of endocrine factors

3.7.2.1 Treatment of primary/secondary amenorrhea

Basically, the choice of treatment for menstrual cycle disorders including primary and secondary amenorrhea is determined by the underlying pathology.

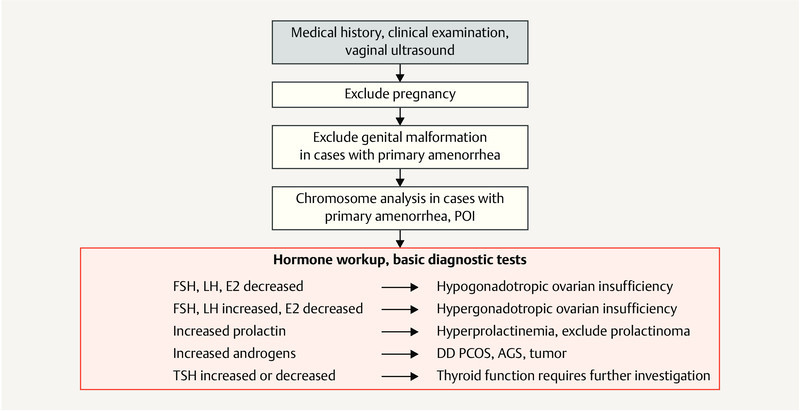

The choice of infertility treatment is determined by the diagnostic findings, any underlying hormonal disorders, and, for couples wanting to have children, other possible causes of infertility affecting the couple. The approach is shown in the diagram depicted in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

Therapeutic approach for amenorrhea. [rerif]

Women who are underweight with a BMI of less than 19 kg/m 2 and disordered ovulation should aim to increase their body weight 18 . The Endocrine Society recommends only starting hormonal stimulation to treat infertility in women with a BMI of > 18.5 kg/m 2 11 . Women with obesity should similarly aim to correct their body weight 11 .

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E35 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Women with a BMI of > 30 kg/m 2 must be advised to lose weight. | |

3.7.2.2 Treatment for hyperprolactinemia

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E36 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Women with confirmed hyperprolactinemia must be treated with dopamine agonists. | |

3.7.2.3 Treatment for PCOS/hyperandrogenemia

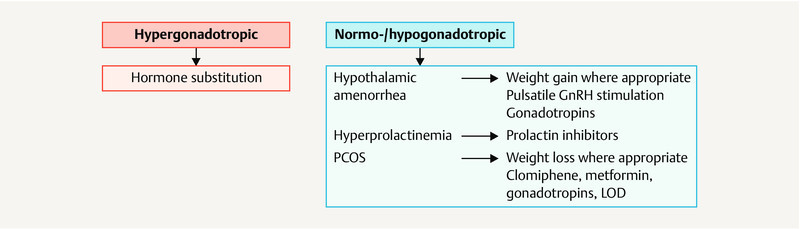

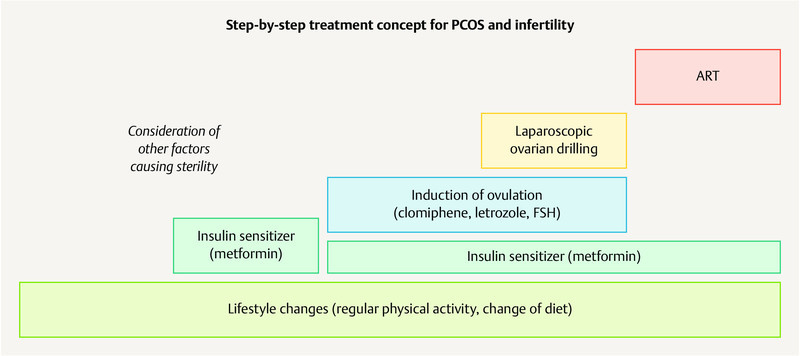

Treatment for PCOS follows a step-by-step approach ( Fig. 4 ). A better metabolic control though lifestyle changes including a change of diet and increased physical activity leading to weight management in women with a high BMI improves the symptoms of hyperandrogenism in women with PCOS 16 .

Fig. 4.

Step-by-step approach to treat PCOS in women wanting to have children. [rerif]

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E37 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Drug therapies to induce ovulation must be monitored sonographically, particularly in women with PCOS, to prevent multifollicular growth, overstimulation and multiple pregnancy. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E38 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| In women with PCOS and oligo- or anovulation, the first-line therapy to induce ovulation must consist of clomiphene stimulation or letrozole stimulation (off-label use). | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E39 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Metformin may be administered to women with PCOS to increase the frequency of ovulation. | |

3.7.2.4 Treatment of AGS and late-onset AGS

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E40 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Women with classic AGS must be treated with a glucocorticoid which does not cross the placenta. Treatment and monitoring of women must be coordinated with an endocrinologist who has a background in internal medicine. | |

3.7.2.5 Treatment for anovulatory cycles and luteal phase insufficiency

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E41 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Women with spontaneous menstrual cycles should not be prescribed cyclical progestogens. | |

3.7.2.6 Treatment of thyroid dysfunction

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E42 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Women should be prescribed at least 100 – 150 µg iodine supplement per day prior to conception. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E43 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Women with a TSH value of ≥ 2.5 mU/l should be substituted with L-thyroxine to achieve a TSH value of < 2.5 mU/l. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.7.E44 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Women with hyperthyroidism must have completed their definitive thyroid treatment (surgery, radioactive iodine treatment) before starting ART and becoming pregnant. | |

3.8 Immunological factors

Immunological factors which can have an impact on fertility are divided into different categories. Investigations may confirm the presence of unspecific autoantibodies; in rare cases, autoimmune disease may be present.

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.8.E45 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Identification of (unspecific) autoantibodies must not be carried out. | |

3.8.1 Diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of autoimmune disease

3.8.1.1 Antiphospholipid syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus

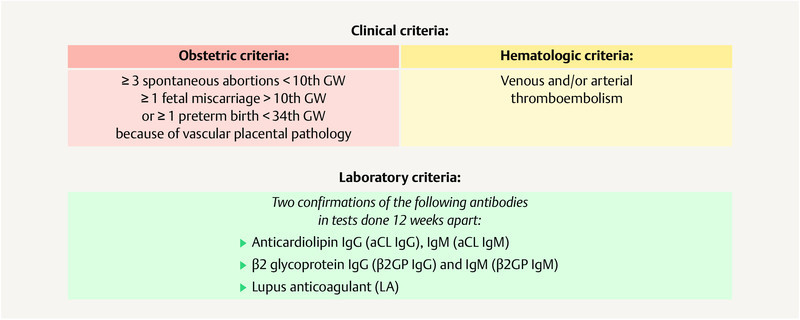

Antiphospholipid syndrome is defined using the Sapporo criteria and the revised Sapporo criteria and includes hematologic, obstetric and laboratory criteria ( Fig. 5 ) 15 , 24 . The incidence is around 5 new cases per 100 000 people every year, and the prevalence is 20 – 50 cases per 100 000 people 2 , 9 .

Fig. 5.

Diagnostic criteria for the confirmation of antiphospholipid syndrome. [rerif]

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.8.E46 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Women with APS/SLE must be managed by an interdisciplinary team already before conception, and management must include the determination of antibody status, disease activity, comorbidities and an updated scheme of treatment. The NMH and LDA dosages must be determined and additional therapeutic measures must be considered for high-risk cohorts (triple positive). | |

3.8.1.2 Other immunological diseases

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.8.E47 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Patients with rheumatoid arthritis, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis and other (auto-)immune disorders must be closely managed by an interdisciplinary team, with care already starting prior to conception. | |

3.8.2 Review of vaccination status before conception

Comprehensive vaccination protection during pregnancy prevents potentially dangerous diseases, vertical transmission to the fetus and intrauterine infections and offers the neonate passive immunity against neonatal infections 10 , 17 , 22 . Live vaccines such as vaccinations against measles, mumps, rubella and varicella zoster are contraindicated during pregnancy, although the risk is more theoretical than real, and inadvertent administration during pregnancy or conception shortly after vaccination are no reason to abort the pregnancy 14 . Inactivated vaccines such as those used against diphtheria, tetanus, influenza, hepatitis A and B and pertussis may be administered before and during pregnancy.

The patientʼs current vaccination status must be reviewed using the patientʼs WHO “International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis” (ICV). Patients who have no ICV should be given a new ICV; all basic immunizations the patient has received must be entered into the ICV or updated where necessary.

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.8.E48 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| The patientʼs vaccination status should be checked in her vaccination book; if necessary, a vaccination book should be created for her. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.8.E49 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The patientʼs rubella and varicella zoster immunity status must be clarified, and vaccination must be recommended where necessary. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.8.E50 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus + |

| Women of childbearing age should be vaccinated against tetanus, diphtheria and whooping cough (pertussis), i.e. they should have a Tdap vaccination every 10 years. | |

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The conflicts of interest of the authors are listed in the long version of the guideline./Die Interessenkonflikte der Autoren sind in der Langfassung der Leitlinie aufgelistet.

Guideline Program. Editors.

Leading Professional Medical Associations

German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe e. V. [DGGG]) Head Office of DGGG and Professional Societies Hausvogteiplatz 12, DE-10117 Berlin mailto:info@dggg.de http://www.dggg.de/

President of DGGG

Prof. Dr. med. Anton Scharl Direktor der Frauenkliniken Klinikum St. Marien Amberg Mariahilfbergweg 7, DE-92224 Amberg Kliniken Nordoberpfalz AG Söllnerstraße 16, DE-92637 Weiden

DGGG Guidelines Representatives

Prof. Dr. med. Matthias W. Beckmann Universitätsklinikum Erlangen, Frauenklinik Universitätsstraße 21–23, DE-91054 Erlangen

Prof. Dr. med. Erich-Franz Solomayer Universitätsklinikum des Saarlandes Geburtshilfe und Reproduktionsmedizin Kirrberger Straße, Gebäude 9, DE-66421 Homburg

Guidelines Coordination

Dr. med. Paul Gaß, Christina Meixner Universitätsklinikum Erlangen, Frauenklinik Universitätsstraße 21–23, DE-91054 Erlangen fk-dggg-leitlinien@uk-erlangen.de http://www.dggg.de/leitlinienstellungnahmen

Austrian Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (Österreichische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe [OEGGG])

Frankgasse 8, AT-1090 Wien stephanie.leutgeb@oeggg.at http://www.oeggg.at

President of OEGGG

Prof. Dr. med. Petra Kohlberger Universitätsklinik für Frauenheilkunde Wien Währinger Gürtel 18–20, AT-1090 Wien

OEGGG Guidelines Representatives

Prof. Dr. med. Karl Tamussino Universitätsklinik für Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe Graz Auenbruggerplatz 14, AT-8036 Graz

Prof. Dr. med. Hanns Helmer Universitätsklinik für Frauenheilkunde Wien Währinger Gürtel 18–20, AT-1090 Wien

Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe [SGGG]) Gynécologie Suisse SGGG Altenbergstraße 29, Postfach 6, CH-3000 Bern 8 sekretariat@sggg.ch http://www.sggg.ch/

President in SGGG

Dr. med. Irène Dingeldein Längmatt 32, CH-3280 Murten

SGGG Guidelines Representatives

Prof. Dr. med. Daniel Surbek Universitätsklinik für Frauenheilkunde Geburtshilfe und feto-maternale Medizin Inselspital Bern Effingerstraße 102, CH-3010 Bern

Prof. Dr. med. René Hornung Kantonsspital St. Gallen, Frauenklinik Rorschacher Straße 95, CH-9007 St. Gallen

References/Literatur

- 1.Acién P, Acién M, Sánchez-Ferrer M. Complex malformations of the female genital tract. New types and revision of classification. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2377–2384. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehrani T, Petri M. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2009. Antiphospholipid Syndrome in systemic autoimmune Diseases; pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaya-Guio J, Viveros-Carreño D A, Sierra-Barrios E M. Antibiotic treatment for the sexual partners of women with bacterial vaginosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(10):CD011701. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011701.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beschluss der Bundesärztekammer über die Richtlinie zur Entnahme und Übertragung von menschlichen Keimzellen im Rahmen der assistierten Reproduktion. Dtsch Arztebl. 2018;115:A-1096/B-922/C-918. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Current clinical irrelevance of luteal phase deficiency: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:e27–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.12.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gesetz über Qualität und Sicherheit von menschlichen Geweben und Zellen (Gewebegesetz), ausgegeben am 27.07.2007. Bundesgesetzblatt 2007 Teil I Nr. 35

- 7.Richtlinie des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses zur Empfängnisregelung und zum Schwangerschaftsabbruch, zuletzt geändert am 21. April 2016, veröffentlicht im Bundesanzeiger AT 28.06.2016 B1, in Kraft getreten am 29. Juni 2016. Bundesanzeiger AT 2016

- 8.Richtlinien des Bundesausschusses der Ärzte und Krankenkassen über ärztliche Maßnahmen zur künstlichen Befruchtung („Richtlinien über künstliche Befruchtung“), zuletzt geändert am 16. März 2017 veröffentlicht im Bundesanzeiger BAnz AT 01.06.2017 B4. in Kraft getreten am 2. Juni 2017. Bundesanzeiger BAnz AT 2017

- 9.Biggioggero M, Meroni P L. The geoepidemiology of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:A299–A304. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonik B, Fasano N, Foster S. The obstetrician-gynecologistʼs role in adult immunization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:984–988. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.128027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon C M, Ackerman K E, Berga S L. Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:1413–1439. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-00131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimbizis G F, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saravelos S H. The Thessaloniki ESHRE/ESGE consensus on diagnosis of female genital anomalies. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Collaborating Centre for Womenʼs and Childrenʼs Health (UK) . London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2013. Fertility: assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller-Stanislawski B, Englund J A, Kang G. Safety of immunization during pregnancy: a review of the evidence of selected inactivated and live attenuated vaccines. Vaccine. 2014;32:7057–7064. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyakis S, Lockshin M D, Atsumi T. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran L J, Hutchison S K, Norman R J. Lifestyle changes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(02):CD007506. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007506.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munoz F M, Englund J A. Vaccines in pregnancy. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:253–271. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70278-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.OʼFlynn N. Assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems: NICE guideline. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64:50–51. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X676609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oduyebo O O, Anorlu R I, Ogunsola F T. The effects of antimicrobial therapy on bacterial vaginosis in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(03):CD006055. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006055.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine . Definitions of infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:63. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine . Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile female: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:e44–e50. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monif G RG, Baker D A. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis; 2004. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deatsman S, Vasilopoulos T, Rhoton-Vlasak A. Age and Fertility: A Study on Patient Awareness. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2016;20:99–106. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20160024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson W A. Estimates of the US prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: Comment on the article by Lawrence et al. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:396. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199902)42:2<396::AID-ANR27>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]