Abstract

Background

Uncertainty lingers about optimal monotherapy initiation for hypertension. Recent guidelines recommend starting any primary agent among five first-line drug classes, thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics (THZ), angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blockers, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (ndCCB), in the absence of comorbid indications. Randomized trials fail to further refine this choice.

Methods

We develop a comprehensive framework for real-world evidence that enables comparative effectiveness and safety evaluation across many drugs and outcomes from observational data encompassing millions of patients while minimizing inherent bias. Using this framework, we conduct a systematic, large-scale study under a new-user cohort design to estimate the relative risks of 3 primary and 6 secondary effectiveness and 46 safety outcomes comparing all first-line classes across a global network of 6 administrative claims and 3 electronic health record databases. The framework addresses residual confounding, publication bias and p-hacking using large-scale propensity adjustment, a large set of control outcomes, and full disclosure of hypotheses tested.

Findings

Using 4.9 million patients, we generate 22,000 calibrated, propensity-score adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) comparing all classes and outcomes across databases. Most estimates reveal no effectiveness differences between classes. THZ, however, demonstrate better primary effectiveness than ACEi: acute myocardial infarction (HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.75–0.95), hospitalization for heart failure (0.83; 0.74–0.95) and stroke (0.83; 0.74–0.95) risk while on initial treatment. Safety profiles also favor THZ over ACEi. The ndCCB drugs are significantly inferior to the other four classes.

Interpretation

This comprehensive framework introduces a new way of conducting observational healthcare science at scale. The approach supports equivalence between drug classes for initiating monotherapy for hypertension -- in keeping with current guidelines -- with the exception of THZ superiority to ACEi and the inferiority of ndCCB.

Funding

US National Science Foundation, US National Institutes of Health, Janssen Research & Development, IQVIA, Australian National Health and Medical Research Council

Background

Patients and physicians have a wide range of pharmacological options to treat hypertension, a key risk factor for cardiovascular disease, but limited guidance on which specific first-line agent to initiate. The 2017 ACC/AHA Blood Pressure Treatment Guidelines endorse any thiazide or thiazide-like diuretic, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker or calcium channel blocker unless contraindicated 1. Similar nonspecificity emerges from the 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines, with the further inclusion of beta-blockers 2.

These recommendations derive largely from older randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that provided direct comparisons between a limited number of agents, not drug classes, and often did not restrict to therapy initiation. For example, the largest head-to-head RCT of antihypertensives, the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), enrolled patients from February 1994 through January 1998, more than two decades ago, evaluated three representative agents and a majority of participants had been previously treated 3. Moreover, most studies considered in the 2017 ACC/AHA Guidelines systematic review 4 were conducted before 2000.

The 2017 Cochrane Review of first-line therapy for hypertension, an update from 2009, found no new RCTs to include 5. Their literature review concludes that “first-line low-dose thiazides reduced all morbidity and mortality outcomes in adult patients with moderate to severe primary hypertension. First-line ACE inhibitors and calcium channel blockers may be similarly effective, but the evidence was of lower quality.” Thus, there remains uncertainty and, unfortunately, we lack contemporary knowledge of the real-world comparative effectiveness of common antihypertensive drugs with respect to outcomes - and the safety trade-offs among these options.

Accordingly, we have developed the open-science Large-scale Evidence Generation and Evaluation in a Network of Databases for Hypertension (LEGEND-HTN) study to compare common antihypertensive drug treatments by employing a systematic, large-scale analysis across nine observational databases from the Observational Health Data Science and Informatics (OHDSI) distributed data network 6. This novel approach employs massive data across several countries and synthesizes tens of thousands of comparisons with analytic techniques to minimize residual confounding. In contrast to a single comparison approach, LEGEND provides a comprehensive view of the findings and their consistency across populations, drugs and outcomes and by design avoids the harms of publication bias or over-emphasizing a single observational analysis subject to p-hacking. We report results comparing monotherapy drug classes from participating data sources through November 2018, covering patients from July 1996 to March 2018.

Methods

Data sources

LEGEND-HTN includes six administrative claims and three electronic health record (EHR) databases standardized to OHDSI’s Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) common data model version 5 (https://github.com/OHDSI/CommonDataModel) that maps international coding systems into standard vocabulary concepts. The claims databases are: IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (CCAE, US employer-based private payer -- patient ages <= 65), Optum ClinFormatics (Optum, US private-payer -- primarily <= 65), IBM MarketScan Medicare Supplemental Beneficiaries (MDCR, US retirees -- 65+), IBM MarketScan Multi-state Medicaid (MDCD, US Medicaid enrollees -- all ages), Japan Medical Data Center (JMDC, Japan private-payer -- 18 – 65) and Korea National Health Insurance Service / National Sample Cohort (NHIS/NSC, South Korea -- all ages); the EHRs are: Optum Pan-Therapeutic (PanTher, US health systems -- all ages), IMS/Iqvia Disease Analyzer Germany (IMSG, German ambulatory-care -- all ages) and Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC, US academic health system -- all ages) (see Supplementary Material for database details). All data partners had prior Institutional Review Board approval or exemption for their participation.

Study design

Within each database source, we employ a retrospective, comparative new-user cohort design 7,8. We consider patients new-users if their first observed treatment for hypertension was monotherapy with any active ingredient within the five drug classes listed as primary agents in the 2017 AHA/ACC Guidelines 1: thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics (THZ), angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (dCCB) or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (ndCCB). We require patients to have at least one year of prior database observation before first exposure and a recorded hypertension diagnosis at or in the one-year preceding treatment initiation.

We study 55 outcomes of interest, including both effectiveness and safety end-points. We divide effectiveness outcomes into three primary end-points: acute myocardial infarction (MI), hospitalization for heart failure (HF) and stroke, based on their use in the 2017 AHA/ACC Guidelines systematic review 4, and six further effectiveness outcomes that leading RCTs involving hypertension treatment have considered 3,9,10. The 46 safety outcomes are antihypertensive drug side effects, including angioedema, cough, electrolyte imbalance, gout, diarrhea, and kidney disease. We construct all outcomes based on prior published phenotypes (Supplementary Table 2) and each typically involves one or more diagnosis codes in the inpatient or outpatient setting. The Supplementary Material provides full and reproducible cohort instantiation details for MI, HF and stroke in any OMOP database and links to computer-readable details for the remaining outcomes.

For each outcome, we exclude patients with events prior to initiation and define patient time-at-risk in two ways: on-treatment analysis follows patients from one day after treatment initiation until they first discontinue their initial therapy choice or their record ends, while intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis follows patients until their record ends. We construct these continuous drug exposures from the available longitudinal data by grouping sequential prescriptions that have fewer than 30 days gap between them. We present further details on exposure and outcome cohort construction and standardized execution across the network in the Supplement Material.

Statistical analysis

To adjust for potential measured confounding and improve the balance between drug class cohorts, we build propensity score (PS) models 11 for each class-pair and data source using a consistent data-driven process through regularized regression. 12 This process allows the data to decide which combinations of a large set of predefined baseline patient characteristics, including demographics and prior conditions, drug exposures, procedures and health service utilization behaviors, are most predictive of treatment assignment (see Supplement Material for construction details) The number of potential characteristics differs across class-pair and data source, ranging from 7,515 (ARB vs dCCB in JMDC) to 70,784 (ACEi vs dCCB in Optum). We stratify or variable-ratio match patients by PS and use Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) between alternative target and comparator treatments for the risk of each outcome in each data source. We aggregate HR estimates across data sources to produce meta-analytic estimates using a random-effects meta-analysis 13. For the monotherapy initiation of the five drug classes (ten pairwise comparisons) to study 55 outcomes in nine databases (plus one meta-analysis) using two time-at-risk definitions and two PS-adjustment approaches, we generate 10 × 55 × (9 + 1) × 2 × 2 = 22,000 effect estimates.

Residual study bias from unmeasured and systematic sources can still exist in observational studies after controlling for measured confounding 14,15. Therefore, for each effect estimate, we further conduct negative control outcome experiments where the null hypothesis of no effect is believed to be true using 76 controls (Supplementary Table 3) identified through a data-rich algorithm 16. We use the empirical null distributions and synthetic positive controls 17 to calibrate each HR estimate, its 95% confidence interval (CI) and the p-value to reject the null hypothesis of no differential effect. We refer to a HR as significantly different from the null value when its calibrated 95% CI does not include this value. This corresponds to a calibrated p < 0.05 without correcting for multiple testing.

Finally, for each of the 22,000 target-comparator-outcome-database-analysis combinations, we report full study diagnostics and results. These include power calculations estimating minimum detectable relative risk (MDRR), preference score (a transformation of PS that adjusts for prevalence differences between population) distributions to evaluate empirical equipoise 18 and population generalizability, patient characteristics to evaluate cohort balance before and after PS-adjustment, negative and positive control calibration plots to assess residual bias, and Kaplan-Meier plots to examine HR proportionality assumptions. We define target and comparator cohorts to stand in empirical equipoise if the majority of patients in both carry preference scores between 0.3 and 0.7 and to achieve sufficient balance if all after-adjustment baseline characteristics return absolute standardized mean differences < 0.1.

Post-hoc sensitivity analysis with blood pressure

Because of the potential confounding effect of blood pressure (BP) and to better understand the impact of the lack of base-line BP measurements on effectiveness and safety estimation that arises in administrative claims and some EHR data, we perform a non-prespecified sensitivity analysis within the PanTher database. This EHR does record systolic and diastolic BP for most subjects. For each class-pair, we first rebuild PS models where we additionally include base-line BP measurements as patient characteristics, stratify or match patients under the new PS models that directly adjust for potential BP confounding and then estimate effectiveness and safety HRs.

Study execution

We conduct this study using the open-source OHDSI CohortMethod R package (https://github.com/OHDSI/CohortMethod) with large-scale analytics achieved through the Cyclops R package 19. The pre-specified LEGEND-HTN protocol and end-to-end open and executable source code are available at: https://github.com/OHDSI/Legend. We have developed an interactive LEGEND website to promote transparency and allow for sharing and exploration of the complete result set at: http://data.ohdsi.org/LegendBasicViewer. For clarity, we present here principal comparisons and outcomes under an on-treatment, PS-stratified design; see the Supplementary Material and website for all comparisons, outcomes, databases and analysis choices of interest.

Role of funding sources

No funding sources (Janssen, IQVIA, US National Science Foundation, US National Institutes of Health and Australian National Health and Medical Research Council) had input in the design, execution, interpretation of results or decision to publish.

Supplementary material and protocol

Supplementary material is available at: https://www.dropbox.com/s/rnxoodpjkx2sa1g/SupplementaryMaterial_Lancet_revision.pdf?dl=0

Protocol is available at: https://github.com/OHDSI/Legend/blob/master/Documents/OHDSI%20Legend%20Protocol%20Hypertension%20V03.docx

Results

LEGEND-HTN includes longitudinal claims and EHR data from 4,893,591 patients, 48% of whom initiated an ACEI, 17% a THZ, 16% a dCCB, 15% an ARB, and 3% an ndCCB (Table 1). The CCAE, PanTher, and Optum databases contributed the most patients to the study across all five drug classes. Median on-treatment time-at-risk for patients varied by drug class and database between one to seven months, but in most databases, 25% of the patients were exposed to their first drug class for greater than one year. Median overall follow-up time for patients was more than two years for most databases, with 25% of patients having more than five years of follow-up in each drug class. Supplementary Table 4 details individual drug ingredients within each class. The majority of ACEi new-users started on lisinopril (80%), THZ new-users on hydrochlorothiazide (94%), ARB new-users on losartan (45%), dCCB new-users on amlodipine (85%), and nCCB new-users on diltiazem (62%).

Table 1:

Population size and follow-up time for each first-line antihypertensive drug class within each database. We report median and interquartile range (IQR) times. When executing comparative studies, we exclude database populations with < 2,500 new-users.

| On-treatment time (in days) |

Total follow-up time (in days) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Database | Patients | median | IQR | median | IQR | |

| Thiazide or thiazide-like diuretic (THZ) | CCAE | 305,741 | 95 | (29 – 486) | 733 | (300 – 2,247) |

| Optum | 201,325 | 90 | (30 – 478) | 740 | (303 – 2,183) | |

| MDCR | 36,683 | 116 | (29 – 612) | 1,025 | (418 – 2,779) | |

| MDCD | 34,743 | 59 | (30 – 245) | 553 | (253 – 1,828) | |

| NHIS-NSC | 6,454 | 29 | (6 – 414) | 2,555 | (1,397 – 3,680) | |

| PanTher | 234,274 | 89 | (89 – 198) | 1,245 | (547 – 2,534) | |

| IMSG | 5,113 | 100 | (50 – 287) | 1,310 | (528 – 2,909) | |

| CUMC | 6,275 | 250 | (51 – 1,537) | 1,807 | (752 – 3,652) | |

| Total: | 830,608 | |||||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) | CCAE | 779,041 | 116 | (38 – 530) | 675 | (282 – 1,960) |

| Optum | 563,419 | 118 | (30 – 555) | 722 | (298 – 2,130) | |

| MDCR | 101,610 | 152 | (58 – 652) | 831 | (365 – 2,423) | |

| MDCD | 66,185 | 78 | (30 – 329) | 578 | (262 – 1,879) | |

| NHIS-NSC | 5,317 | 67 | (27 – 525) | 2,756 | (1,733 – 3,738) | |

| PanTher | 737,065 | 89 | (89 – 200) | 1,099 | (459 – 2,313) | |

| IMSG | 109,799 | 100 | (50 – 402) | 1,196 | (508 – 2,627) | |

| CUMC | 10,571 | 104 | (30 – 1,225) | 1,388 | (511 – 3,390) | |

| Total: | 2,373,007 | |||||

| Angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) | CCAE | 230,002 | 147 | (54 – 628) | 699 | (288 – 2,149) |

| Optum | 170,852 | 146 | (46 – 640) | 694 | (292 – 2,100) | |

| MDCR | 31,647 | 195 | (83 – 779) | 953 | (401 – 2,661) | |

| MDCD | 7,764 | 87 | (30 – 347) | 548 | (249 – 2,008) | |

| JMDC | 53,532 | 218 | (58 – 983) | 793 | (354 – 1,865) | |

| NHIS-NSC | 16,286 | 128 | (29 – 1,004) | 1,475 | (706 – 3,010) | |

| PanTher | 207,097 | 89 | (37 – 187) | 1,017 | (395 – 2,259) | |

| IMSG | 29,951 | 98 | (56 – 427) | 974 | (414 – 2,323) | |

| CUMC | 5,361 | 90 | (30 – 500) | 1,153 | (482 – 2,673) | |

| Total: | 752,492 | |||||

| Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (dCCB) | CCAE | 217,684 | 89 | (29 – 456) | 613 | (254 – 1,803) |

| Optum | 169,209 | 91 | (30 – 515) | 660 | (272 – 2,014) | |

| MDCR | 38,514 | 143 | (47 – 654) | 768 | (341 – 2,240) | |

| MDCD | 34,860 | 53 | (30 – 238) | 494 | (217 – 1,548) | |

| JMDC | 51,770 | 136 | (30 – 741) | 649 | (291 – 1,665) | |

| NHIS-NSC | 33,050 | 60 | (14 – 815) | 2,101 | (1,124 – 3,422) | |

| PanTher | 227,899 | 89 | (84 – 187) | 919 | (336 – 2,139) | |

| IMSG | 18,262 | 100 | (50 – 328) | 1,176 | (471 – 2,632) | |

| CUMC | 7,292 | 90 | (30 – 768) | 1.099 | (329 – 2,971) | |

| Total: | 798,540 | |||||

| Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (ndCCB) | CCAE | 33,382 | 93 | (29 – 528) | 719 | (298 – 2,265) |

| Optum | 38,831 | 119 | (30 – 663) | 780 | (307 – 2,249) | |

| MDCR | 10,613 | 134 | (36 – 676) | 819 | (352 – 2,513) | |

| MDCD | 4,248 | 61 | (30 – 303) | 657 | (275 – 2,190) | |

| PanTher | 51,870 | 89 | (29 – 163) | 1,272 | (552 – 2,527) | |

| Total: | 138,944 | |||||

Table 2 illustrates the patient baseline characteristics for one target - comparator - database combination, comparing patients initiating THZ (target) with patients initiating ACEi (comparator) in the CCAE database. Before PS stratification, ACEi new-users are more likely to be male, have diabetes, hyperlipidemia, arteriosclerosis or heart disease relative to patients initiating a THZ. After stratification, the THZ and ACEi populations are well-balanced on all 56,535 baseline patient characteristics. Supplementary Tables 5a – 5i present patient baseline characteristics for the remaining pairwise class comparisons in CCAE. To highlight some specific differences between the new-user populations prior to adjustment: ndCCB new-users have a higher baseline prevalence of atrial fibrillation and other heart diseases than other class users, while dCCB new-users are more likely be pregnant women than ACEi/ARB (classes for which use during pregnancy is specifically contraindicated) new-users (Supplementary Figure 2). Finally, Supplementary Figure 16 histograms display base-line systolic and diastolic BP for new-users across all drug-classes in the PanTher database. THZ new-users have the highest median BP of 142/88 (interquartile range [IQR]: 130/80 – 152/95), followed by dCCB (141/84, IQR: 130/76 – 155/94), ACEi (140/84, IQR: 128/76 – 152/92), ARB (138/82, IQR: 126/74 – 150/90) and ndCCB (133/80, IQR: 122/70 – 146/87).

Table 2:

Baseline patient characteristics for THZ and ACEi new-users in the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (CCAE) database. We report the proportion of new-users satisfying selected baseline characteristics and the standardized difference of population proportions (StdDiff) before and after stratification. Less extreme StdDiffs through stratification suggest improved balance between patient cohorts through propensity score adjustment.

| Before stratification |

After stratification |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | THZ(%) | ACEi (%) | StdDiff | THZ (%) | ACEi (%) | StdDiff |

| Age group | ||||||

| 10–14 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −0.02 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| 15–19 | 0.6 | 0.7 | −0.02 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.00 |

| 20–24 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.02 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.01 |

| 25–29 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 0.06 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 0.00 |

| 40–44 | 13.4 | 12.1 | 0.04 | 12.3 | 12.4 | 0.00 |

| 45–49 | 16.3 | 16.1 | 0.01 | 15.9 | 16.2 | −0.01 |

| 50–54 | 17.7 | 18.7 | −0.03 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 0.00 |

| 55–59 | 16.2 | 18.3 | −0.06 | 18.0 | 17.8 | 0.00 |

| 60–64 | 13.2 | 15.5 | −0.06 | 15.3 | 15.0 | 0.01 |

| 65–69 | 1.1 | 1.3 | −0.02 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.00 |

| Gender: female | 60.7 | 38.4 | 0.46 | 45.2 | 44.7 | 0.01 |

| Medical history: General | ||||||

| Acute respiratory disease | 26.1 | 24.5 | 0.04 | 25.5 | 25.0 | 0.01 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 1.1 | 1.2 | −0.01 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.00 |

| Chronic liver disease | 1.1 | 1.5 | −0.03 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.00 |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 1.4 | 1.8 | −0.03 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.00 |

| Dementia | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.00 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| Depressive disorder | 8.1 | 7.4 | 0.03 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4.6 | 18.3 | −0.44 | 13.5 | 14.5 | −0.03 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 7.5 | 7.8 | −0.01 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 0.00 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1.6 | 1.7 | −0.01 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.01 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.00 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 25.5 | 36.1 | −0.23 | 33.0 | 33.2 | 0.00 |

| Lesion of liver | 0.2 | 0.2 | −0.01 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Obesity | 10.0 | 8.5 | 0.05 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 0.01 |

| Osteoarthritis | 10.7 | 11.3 | −0.02 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 0.01 |

| Pneumonia | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.00 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.01 |

| Psoriasis | 0.9 | 1.0 | −0.02 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.00 |

| Renal impairment | 0.5 | 1.1 | −0.06 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.01 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.01 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.00 |

| Schizophrenia | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.00 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 0.2 | 0.3 | −0.01 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Urinary tract infectious disease | 6.4 | 5.1 | 0.05 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 0.01 |

| Viral hepatitis C | 0.3 | 0.4 | −0.01 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.00 |

| Medical history: Cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.3 | 0.4 | −0.03 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.00 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.0 | 1.7 | −0.06 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.00 |

| Coronary arteriosclerosis | 1.0 | 2.2 | −0.10 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0.00 |

| Heart disease | 6.5 | 9.0 | −0.09 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 0.01 |

| Heart failure | 0.3 | 0.5 | −0.02 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.00 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0.9 | 1.7 | −0.07 | 1.4 | 1.5 | −0.01 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3.3 | 4.1 | −0.04 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 0.01 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.00 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Medical history: Neoplasms | ||||||

| Hematologic neoplasm | 0.4 | 0.5 | −0.01 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.01 |

| Malignant lymphoma | 0.2 | 0.2 | −0.01 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Malignant neoplasm of anorectum | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.01 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| Malignant neoplastic disease | 3.8 | 4.2 | −0.02 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 0.01 |

| Malignant tumor of breast | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.03 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.01 |

| Malignant tumor of colon | 0.2 | 0.2 | −0.01 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.00 |

| Malignant tumor of lung | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.00 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| Malignant tumor of urinary bladder | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.01 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| Primary malignant neoplasm of prostate | 0.3 | 0.5 | −0.03 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Medication use | ||||||

| Antibacterials for systemic use | 50.7 | 48.8 | 0.04 | 50.1 | 49.3 | 0.02 |

| Antidepressants | 19.1 | 17.7 | 0.04 | 18.6 | 18.2 | 0.01 |

| Antiepileptics | 6.0 | 6.2 | −0.01 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 0.00 |

| Antiinflammatory and antirheumatic products | 26.3 | 24.0 | 0.05 | 25.1 | 24.6 | 0.01 |

| Antineoplastic agents | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.00 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.01 |

| Antipsoriatics | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.00 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.00 |

| Antithrombotic agents | 2.2 | 3.3 | −0.06 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 0.01 |

| Beta blocking agents | 0.4 | 0.5 | −0.01 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Drugs for acid related disorders | 14.0 | 14.1 | 0.00 | 14.4 | 14.1 | 0.01 |

| Drugs for obstructive airway diseases | 20.3 | 18.1 | 0.06 | 19.0 | 18.8 | 0.01 |

| Drugs used in diabetes | 3.1 | 15.6 | −0.44 | 10.9 | 12.1 | −0.04 |

| Immunosuppressants | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.00 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.00 |

| Lipid modifying agents | 13.6 | 24.6 | −0.28 | 21.0 | 21.6 | −0.02 |

| Opioids | 16.0 | 15.2 | 0.02 | 15.9 | 15.5 | 0.01 |

| Psycholeptics | 18.2 | 17.6 | 0.02 | 18.4 | 17.8 | 0.02 |

| Psychostimulants, agents used for adhd and nootropics | 3.1 | 2.9 | 0.02 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 0.01 |

For five data sources (CCAE, MDCR, IMSG, JMDC, CUMC), all executed class comparisons stand in empirical equipoise (see Supplementary Figure 1 for preference score distributions in CCAE). MDCD, Optum, PanTher and NHIS show less equipoise for comparisons involving ARBs or ndCCBs. However, in general, PS-adjustment achieves sufficient covariate balance to reduce concerns that measured baseline confounding biases estimated effects (Supplementary Figure 2). Finally, before calibration, nominal 95% confidence intervals cover 86.7% of control estimates across all comparisons; after calibration, they cover 96.7%.

Table 3 reports the meta-analytic comparative effect estimates for our primary effectiveness outcomes: acute MI, hospitalization for HF and stroke. More than half of the comparisons show no significant difference between classes at a nominal 5% Type I error rate. However, THZs demonstrate a significantly lower risk of all three outcomes relative to ACEis (acute MI: HR=0.84 [95% CI: 0.75 – 0.95); HF: HR=0.83 [95% CI: 0.74 – 0.95] and stroke: HR=0.83 [95% CI: 0.74 – 0.95]) with an approximate 15% lower event rate. Supplementary Table 6 reports patient counts, observation time and events for pairwise class comparisons under the primary effectiveness outcomes.

Table 3:

Meta-analytic hazard ratios (HR) estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) comparing the relative risk of primary cardiovascular effectiveness outcomes between new-users of first-line antihypertensive drug classes. Primary outcomes are acute myocardial infarction (MI), hospitalization for heart failure (HF) and stroke. Estimates are calibrated to reduce residual bias and report the HR for patients in the target cohort relative to comparator cohort; HRs < 1 favor target.

| Acute MI |

Hosp. for HF |

Stroke |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Comparator | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p |

| THZ | ACEi | 0.84 (0.75 – 0.95) | 0.01 | 0.83 (0.74 – 0.95) | 0.01 | 0.83 (0.74 – 0.95) | 0.01 |

| THZ | ARB | 0.93 (0.81 – 1.11) | 0.41 | 0.90 (0.79 – 1.06) | 0.19 | 0.93 (0.80 – 1.11) | 0.41 |

| THZ | dCCB | 0.90 (0.81 – 1.02) | 0.14 | 0.90 (0.80 – 1.04) | 0.18 | 0.89 (0.79 – 1.03) | 0.14 |

| THZ | ndCCB | 0.70 (0.59 – 0.84) | < 0.01 | 0.58 (0.52 – 0.65) | < 0.01 | 0.78 (0.71 – 0.87) | < 0.01 |

| ACEi | ARB | 1.11 (0.95 – 1.32) | 0.20 | 1.05 (0.88 – 1.26) | 0.60 | 1.07 (0.92 – 1.27) | 0.38 |

| ACEi | dCCB | 1.08 (0.96 – 1.22) | 0.18 | 1.08 (0.94 – 1.25) | 0.24 | 1.05 (0.93 – 1.21) | 0.38 |

| ACEi | ndCCB | 0.87 (0.77 – 1.00) | 0.04 | 0.68 (0.60 – 0.78) | < 0.01 | 0.89 (0.82 – 0.98) | 0.02 |

| ARB | dCCB | 0.95 (0.80 – 1.14) | 0.69 | 1.04 (0.86 – 1.26) | 0.66 | 0.99 (0.83 – 1.19) | 0.93 |

| ARB | ndCCB | 0.78 (0.69 – 0.91) | 0.01 | 0.71 (0.64 – 0.80) | < 0.01 | 0.84 (0.73 – 0.97) | 0.05 |

| dCCB | ndCCB | 0.84 (0.76 – 0.93) | < 0.01 | 0.73 (0.68 – 0.78) | < 0.01 | 0.87 (0.79 – 0.96) | 0.01 |

THZs also show a significantly lower risk of acute MI, hospitalization for HF and stroke relative to ndCCBs (Table 3). We observe no significant differences in these outcomes between THZs and either ARBs or dCCBs. However, we find that the two subtypes of calcium channel blockers exhibit significantly differential hazards, with dCCBs having a lower risk of acute MI, hospitalization for HF and stroke relative to ndCCBs. Finally, we observe no differences in these three primary effectiveness outcomes between ACEis, ARBs and dCCBs.

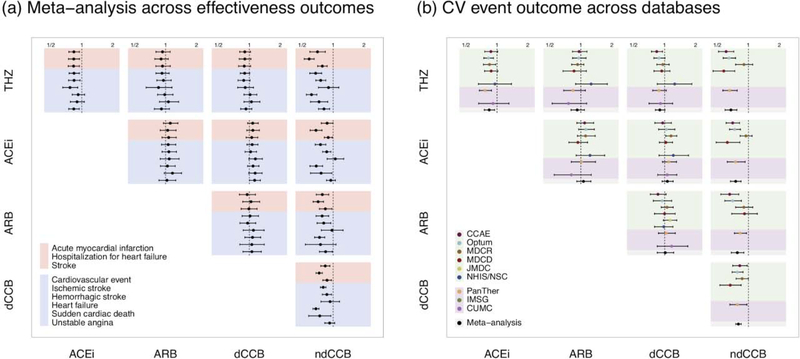

Figure 1a presents the meta-analytic comparative effect estimates across all nine effectiveness outcomes. Seven of these outcomes demonstrate a significantly decreased HR in favor of THZs as compared to ACEis. We observe no significant differences in outcomes in the remaining comparisons, with the marked exception of ndCCBs that underperform all other drug classes. Figure 1b further stratifies meta-analytic estimates into their individual data source-specific contributions for one exemplar outcome: major cardiovascular (CV) events that is a composite based on ALLHAT of acute MI, hospitalization for HF, stroke and sudden cardiac death. In all CV event comparisons, data sources return relatively consistent estimates, with I 2 < 40% indicating low heterogeneity. In comparing THZs and ACEIs, we observed that three databases independently return significantly decreased effect estimates, and the meta-analysis allows greater precision around the estimate (HR=0.84 [95% CI: 0.75–0.95]) than any one source alone achieves. Relative to ndCCBs, we again see that THZs, ACEIs, ARBs and dCCBs all demonstrate decreased risks of CV events, with two or more sources contributing significant effect estimates to the meta-analysis.

Figure 1:

Comparative effectiveness of THZ, ACEi, ARB, dCCB and ndCCB drug classes. Points report HR estimates and lines mark their 95% CIs. HRs < 1 favor target (row) over comparator (column). (a) Meta-analytic risk estimates across all nine effectiveness outcomes with primary outcomes in red and secondary outcomes in blue. (b) Cardiovascular (CV) event risk estimates by data source and meta-analysis. Colors identify databases; the top block are administrative claims databases, the middle block are EHRs and black highlights a meta-analysis across all other sources. Not all databases contain sufficient new-users for study inclusion. CV event is a composite outcome of acute MI, hospitalization for HF, stroke and sudden cardiac death.

Figure 2 displays meta-analytic effect estimates for all 46 safety outcomes in comparing THZs with ACEIs, ARBs, dCCBs and ndCCBs. The remaining comparisons are in Supplementary Figures 12a – 12c. Relative to other drug classes, THZs have a significantly higher risk of hypokalemia (vs ACEi HR=2.8 [95% CI: 2.2 – 3.6], vs ARB HR=2.9 [95% CI: 2.2 – 4.3], vs dCCB HR =1.9 [95% CI: 1.6 – 2.4] and vs ndCCB HR=1.8 [95% CI: 1.5 – 2.1]) and, correspondingly, a significantly lower risk of hyperkalemia. THZs also demonstrate a significantly higher risk of hyponatremia compared to other drug classes. As expected, there is a significantly increased risk of angioedema and cough for ACEi new-users. The resulting, PS-adjusted and calibrated HR for angioedema in THZ vs ACEi new-users is 0.44 (95% CI, 0.35 – 0.57). Across all disease categories, 16 further safety outcomes occur at a significantly higher rate in ACEi as compared to THZ new-users including mortality, gastrointestinal side-effects and renal disorders.

Figure 2:

Meta-analytic safety profiles comparing THZ to ACEi, ARB, dCCB and ndCCB new-users across 46 outcomes listed on product labels. Points and lines identify HR estimates with their 95% CIs, respectively. Outcomes in grey signify that the CI covers HR =1 (null hypothesis of no differential risk).

Figure 3 examines the effect of adjusting for base-line BP across all nine effectiveness outcomes for all class-pairs in the PanTher database. Out of 90 HR estimates, only three cases change their statistically significant interpretation when incorporating BP in the PS model. The risk of acute MI in THZ vs ACEi new-users moves from HR=0.81 (95% CI: 0.68 – 0.98) to HR=0.85 (95% CI: 0.70 – 0.1.03) and the 95% CIs measuring the risk of acute MI and stroke in dCCB and ndCCB no longer cover HR=1. Supplementary Figure 17 shows similar consistency between estimates for the safety profile of THZ vs ACEi.

Figure 3:

Effectiveness estimates comparing THZ to ACEi, ARB, dCCB and ndCCB new-users using propensity scores with and without baseline blood pressure (BP) adjustment in the PanTher database. Points and lines identify HR estimates with their 95% CIs, respectively. Black circles demarcate estimates based on large-scale propensity scores built without BP measurements and grey squares identify estimates additionally including baseline measurements from the electronic health record.

Discussion

LEGEND-HTN is the largest and most comprehensive study ever conducted to provide evidence about the comparative effectiveness and safety of first-line antihypertensives, representing more than 4.9 million patients initiating monotherapy across nine databases from four countries, examining all pairwise comparisons between the five first-line drug classes against a panel of 55 health outcomes. This equates to 22,000 traditional observational studies, many of which researchers could have hand-picked, hand-tweaked and published individually. Most comparisons reveal no effectiveness differences between classes. We find, however, that patients initiating treatment with a THZ have a significantly lower risk of seven effectiveness outcomes, including acute MI, hospitalization for HF and stroke, as compared to ACEi new-users while patients remain on-treatment with their initial drug class choice. Additionally, the THZ safety profile is markedly better compared with ACEis. Patients who initiate with an ndCCB experience a significantly higher risk of poor effectiveness outcome compared with all other class choices, but less adequate cohort balance and equipoise in these comparisons may limit their generalizability. Finally, there stand no significant effectiveness differences between the remaining classes.

Across the patients we study who initiated monotherapy, nearly 50% are prescribed ACEis and fewer than 18% THZs. While our results suggest ACEis have only a modestly less favorable effectiveness profile than THZs in magnitude, the effect of favoring THZs across the whole population could be substantial; if the 2.4 million ACEi new-users we observed had instead chosen a THZ, over 3,100 major CV events could potentially have been avoided. This equates to 1.3 CV events avoided for every 1,000 patients who initiate with a THZ instead of an ACEi, yielding a substantial public health impact, particularly given the more favourable safety profile of THZs.

Real-world observational studies can fill evidence gaps from what can be learned from RCTs. Whereas RCTs remain a key tool for high-quality clinical efficacy estimates in patient-limited, controlled settings, LEGEND-HTN delivers estimates of real-world effectiveness 20. For example, the 2017 ACC/AHA Blood Pressure Treatment Guideline systematic review conducts a meta-analysis of three RCTs 3,21,22 to estimate the relative risk (RR) of MI between 18,421 THZ and 12,225 ACEi users in total, yielding a RR of 1.2 (95% CI: 0.78 – 2.0). This estimate is concordant with, but lacks the statistical power of the LEGEND-HTN estimate involving over 2.2 million patients who further encompass greater real-world heterogeneity. We note, however, that the LEGEND-HTN estimate of MI risk is not concordant with any of the three individual RCTs, but their marked differences with each other leaves the question unanswered. For important efficacy outcomes, head-to-head RCTs between specific drug classes do not exist; examples include: THZ vs ARB for risk of HF, and THZ vs ARB and ACEi vs ARB for risk of major CV events and renal events 4. Further, for convenience, extant RCTs usually recruit previously treated hypertensive subjects; LEGEND-HTN, on the other hand, focuses on treatment initiation and so directly assess initiation guidelines Finally, while RCTs and the systematic review furnish a comprehensive summary of cardiovascular outcomes, there is relatively little evidence about the comparative safety of these classes. LEGEND-HTN provides this additional context across a large panel of effectiveness and safety outcomes for all class comparisons.

Through an international network, LEGEND-HTN seeks to take advantage of disparate health databases drawn from different sources, including administrative claims and EHRs, and across a range of countries and practice settings. These large-scale and unfiltered populations better represent real-world practice than the restricted study populations in prescribed treatment and follow-up settings from RCTs. The strong agreement among the separate database estimates despite heterogeneity in patient populations, practice-settings and data capture processes further supports the plausibility of true causal effect differences. Even with this greater generalizability, however, we cannot exclude the possibility of subpopulations not sufficiently captured in our research network that feature a considerably different effectiveness profile.

An obvious LEGEND-HTN limitation is the absence of BP measurements within some databases. Baseline BP may drive class choice, resulting in unmeasured confounding by indication between cohorts. For example, physicians may preferentially prescribe a THZ rather than an ACEi for patients with lower baseline BP. If uncorrected, this can bias risk estimates to favor THZs given the strong correlation between higher BP and cardiovascular events. In PanTher, however, we observed that THZ new-users have the highest median BP across drug classes. Unfortunately, there is no guarantee that this relationship holds in other data sources. So, to protect against such confounding, LEGEND-HTN employs large-scale PS-models involving tens of thousands of baseline patient characteristics, many of which should also associate with BP to facilitate its indirect adjustment in spite of remaining unobserved. A post hoc sensitivity analysis reveals that including BP in the PS-model does achieve near-perfect balance on baseline BP across comparisons in PanTher, but does not lead to clinically meaningfully different effect sizes estimates than when not including BP.

LEGEND-HTN’s standardization enables us to consider multiple study design choices. One choice is the time-at-risk definition. On-treatment time results in shorter follow-up than ITT. As expected, we see blunted estimates of differential effectiveness and risks between drug class new-users under an ITT design (see Supplementary Material). We caution, however, against over-interpreting estimate differences between time-at-risk choices, as treatment escalation is more likely to confound ITT estimates.

On-treatment follow-up time also helps assess differential adherence to initial treatment. Except in the CUMC database, median on-treatment time is modestly shorter (0 – 38 days) for THZ vs ACEi new-users. Such differences, if meaningful, are also less likely to confound on-treatment estimates where time-at-risk ends with initiation treatment discontinuation. Further, claims databases report drug fulfillment while EHRs report prescriptions. As fulfillment more directly reflects actual drug-taking, one might expect differential adherence to generate notable effect estimate differences across data sources; we do not observe such differences in comparing THZ vs ACEi new-users.

Finally, cardiovascular observational research has a poor track record when it comes to reliability and reproducibility 23. One likely cause is residual confounding due to the observational nature of the studies. In contrast to most observational research, LEGEND-HTN minimizes the risk of residual bias by using reproducible methods to address observed confounding, by reporting study diagnostics such as empirical equipoise and covariate balance, and by unprecedentedly applying a large set of control outcomes to measure and then account for remaining systematic error. Marked covariate balance and empirical equipoise between new-user cohorts across data sources demonstrate here successful adjustment for observed confounding and comparable, generalizable populations for HR estimation. Control experiments further reduce systematic error and return calibrated CIs and p-values with reliable statistical interpretation. Other causes of concern are publication bias and p-hacking that LEGEND-HTN addresses by consistently applying our study design to many comparisons and reporting all results through its interactive website. This further enables result-set users to apply multiple testing correction for their specific research topic as appropriate. Finally, LEGEND-HTN delivers true Open Science, with all study artifacts including study protocol, analytical code, and full results made publicly available. As a consequence, LEGEND-HTN evidence should demonstrate high reliability 24.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

2017 ACC/AHA Blood Pressure Treatment Guidelines recommend initiating monotherapy for hypertension with any primary agent among five first-line drug classes based on a systematic review of randomized trials. Similar nonspecificity emerges from the 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines. The largest such trial, ALLHAT, enrolled patients more than two decades ago, only evaluated three representative agents and a majority of participants had been previously treated for hypertension. We lack contemporary knowledge of the real-world comparative effectiveness of common antihypertensive drugs with respect to outcomes and the safety trade-offs among these class options for treatment initiation.

Added value of this study

LEGEND for Hypertension exploits state-of-the-art methods to control for residual confounding, publication bias and p-hacking in real-world evidence studies and demonstrates generally comparable effectiveness between drug classes across nine international health databases. However, effectiveness and safety benefits suggest initiating with a thiazide or thiazide-like diuretic over an ACE inhibitor, the most common initiating monotherapy across databases. Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are also inferior to the other four first-line classes.

Implications of all the available evidence

Initiating with a thiazide instead of an ACE inhibitor carries potential to avoid many major cardiovascular events and warrants further study.

Acknowledgments

This work is partially supported through the US National Science Foundation grant IIS 1251151, US National Institutes of Health grants U19 AI135995 and R01 LM006910, and Australian National Health and Medical Research Council grant GNT1157506

Declaration of Interests

Drs. Ryan and Schuemie are employees of Janssen Research and Development, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Reich is an employee of IQVIA, whose customers are the entire pharmaceutical industry, amongst which are the manufacturers of the studied drugs. Drs. Hripcsak and Suchard have received grant funding from Janssen to support methods research not directly related to this study. Neither Janssen nor IQVIA had input in the design, execution, interpretation of results or decision to publish. Dr. Madigan reports personal fees from Simon Greenstone Panatier, Williams Hart, Lieff Cabraser, and the Lanier Law firms. Dr. Krumholz reports personal fees from UnitedHealth, IBM Watson Health, Element Science, Aetna, Facebook, Arnold & Porter, and the Ben C. Martin Law Firm; grants from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson, and the Food and Drug Administration; and serving as founder of the personal health information platform Hugo outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2018;138(17):e426–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018;39(33):3021–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major Outcomes in High-Risk Hypertensive Patients Randomized to Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor or Calcium Channel Blocker vs Diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA 2002;288(23):2981–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reboussin DM, Allen NB, Griswold ME, et al. Systematic Review for the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2018;138(17):e595–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musini VM, Gueyffier F, Puil L, Salzwedel DM, Wright JM. Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in adults aged 18 to 59 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet] 2017;Available from: 10.1002/14651858.cd008276.pub2 (accessed on 21 July 2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hripcsak G, Duke JD, Shah NH, et al. Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI): Opportunities for Observational Researchers. Stud Health Technol Inform 2015;216:574–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan PB, Schuemie MJ, Gruber S, Zorych I, Madigan D. Empirical performance of a new user cohort method: lessons for developing a risk identification and analysis system. Drug Saf 2013;36 Suppl 1:S59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernán MA, Robins JM. Using Big Data to Emulate a Target Trial When a Randomized Trial Is Not Available. Am J Epidemiol 2016;183(8):758–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ACCORD Study Group, Cushman WC, Evans GW, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2010;362(17):1575–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, et al. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N Engl J Med 2015;373(22):2103–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika 1983;70(1):41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian Y, Schuemie MJ, Suchard MA. Evaluating large-scale propensity score performance through real-world and synthetic data experiments. Int J Epidemiol 2018;47(6):2005–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7(3):177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuemie MJ, Ryan PB, DuMouchel W, Suchard MA, Madigan D. Interpreting observational studies: why empirical calibration is needed to correct p-values. Stat Med 2013;33(2):209–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuemie MJ, Hripcsak G, Ryan PB, Madigan D, Suchard MA. Robust empirical calibration of p-values using observational data. Stat Med 2016;35(22):3883–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voss EA, Boyce RD, Ryan PB, van der Lei J, Rijnbeek PR, Schuemie MJ. Accuracy of an automated knowledge base for identifying drug adverse reactions. J Biomed Inform 2017;66:72–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuemie MJ, Hripcsak G, Ryan PB, Madigan D, Suchard MA. Empirical confidence interval calibration for population-level effect estimation studies in observational healthcare data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018;115(11):2571–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker A, Patrick Lauer, et al. A tool for assessing the feasibility of comparative effectiveness research. Comparative Effectiveness Research 2013;3:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suchard MA, Simpson SE, Zorych I, Ryan P, Madigan D. Massive Parallelization of Serial Inference Algorithms for a Complex Generalized Linear Model. ACM Trans Model Comput Simul 2013;23(1):10:1–10:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roland M, Torgerson DJ. What are pragmatic trials? BMJ 1998;316(7127):285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zanchetti A, Crepaldi G, Bond MG, et al. Different effects of antihypertensive regimens based on fosinopril or hydrochlorothiazide with or without lipid lowering by pravastatin on progression of asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis: principal results of PHYLLIS--a randomized double-blind trial. Stroke 2004;35(12):2807–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wing LMH, Reid CM, Ryan P, et al. A comparison of outcomes with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and diuretics for hypertension in the elderly. N Engl J Med 2003;348(7):583–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rush CJ, Campbell RT, Jhund PS, Petrie MC, McMurray JJV. Association is not causation: treatment effects cannot be estimated from observational data in heart failure. Eur Heart J 2018;39(37):3417–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuemie MJ, Ryan PB, Hripcsak G, Madigan D, Suchard MA. Improving reproducibility by using high-throughput observational studies with empirical calibration. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci [Internet] 2018;376(2128). Available from: 10.1098/rsta.2017.0356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.