Abstract

Introduction

Home care clients are increasingly medically complex, have limited access to effective chronic disease management and have very high emergency department (ED) visitation rates. There is a need for more appropriate and targeted supportive chronic disease management for home care clients. We aim to evaluate the effectiveness and preliminary cost effectiveness of a targeted, person-centred cardiorespiratory management model.

Methods and analysis

The Detection of Indicators and Vulnerabilities of Emergency Room Trips (DIVERT) — Collaboration Action Research and Evaluation (CARE) trial is a pragmatic, cluster-randomised, multicentre superiority trial of a flexible multicomponent cardiorespiratory management model based on the best practice guidelines. The trial will be conducted in partnership with three regional, public-sector, home care providers across Canada. The primary outcome of the trial is the difference in time to first unplanned ED visit (hazard rate) within 6 months. Additional secondary outcomes are to identify changes in patient activation, changes in cardiorespiratory symptom frequencies and cost effectiveness over 6 months. We will also investigate the difference in the number of unplanned ED visits, number of inpatient hospitalisations and changes in health-related quality of life. Multilevel proportional hazard and generalised linear models will be used to test the primary and secondary hypotheses. Sample size simulations indicate that enrolling 1100 home care clients across 36 clusters (home care caseloads) will yield a power of 81% given an HR of 0.75.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board as well as each participating site’s ethics board. Results will be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals and for presentation at relevant conferences. Home care service partners will also be informed of the study’s results. The results will be used to inform future support strategies for older adults receiving home care services.

Trial registration number

Keywords: cardio-respiratory, disease management, chronic disease management, cluster-randomised, DIVERT scale, home care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The pragmatic attitude of the trial towards cluster selection, cluster assignment, participant selection, participant recruitment, informed consent and outcome measurement supports generalisation to other jurisdictions.

Postrandomisation selection bias is limited by the use of existing, objective measures of eligibility.

The use of secondary data for baseline data collection and follow-up measurement increases the accuracy of the data collection and limits the loss to follow-up compared with primary collection methods.

It is not possible to conceal the treatment assignment, which exposes half of the primary and secondary outcomes measures to placebo and observer-expectancy effects.

The jurisdictions included in the study used a convenience, non-probability sampling approach in cluster selection, which may limit external validity.

Introduction

Publicly funded home care services are delivered to at least 6% of Canadians aged 65–74, 15% aged 75–84% and 32% aged 85 or older.1 These home care clients are increasingly medically complex, often access care across multiple settings, have very high emergency department (ED) visitation rates and have relatively poor access to effective chronic disease management.2–4 Their frequent ED use is not congruent with chronic disease management or geriatric care principles and creates excess cost burdens on the healthcare system.5 6

Effective chronic disease management models employ multiple components delivered by a coordinated multidisciplinary team.7 According to the ‘chronic disease management model’, home care plays a complementary function to the care medical practitioners provide.7 Clinical and self-care support, as well as case management, are among the most effective components in chronic disease management.8–10 Self-care education and support has been shown to improve health outcomes across chronic diseases.11 12 The provision of sustained follow-up by nurses or non-medical staff can also be effective.13 14

Effective home care services have been limited by insufficient targeting of clients that are most at need or most likely to benefit.15 16 We developed and validated a prognostic case-finding tool for home care clients known as the Detection of Indicators and Vulnerabilities of Emergency Room Trips (DIVERT) Scale that has been recommended for use in the provision of home care.17–19 It can be derived in real time from the inter-Resident Assessment Instrument for Home Care (RAI-HC) standardised home care assessment system used in nine Canadian provinces as well as Estonia, Finland, Hong Kong, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Singapore, Spain, Switzerland and 29 US states. Cardiorespiratory symptoms and conditions are prominent predictive elements of the DIVERT Scale.

Canadian home care providers, historically focused on the delivery of personal support services, have started to develop supportive chronic disease management capacity (eg, specialist nurse monitoring).20 Most trials, however, exclude frail seniors and are not specific to home care, which leaves little evidence to inform chronic disease management practices in this large sector of healthcare.17

From evidence-based guidelines developed—in part—by our team, extensive client profiling, and input of clients/families as well as health professionals, we developed a person-centred, multicomponent cardiorespiratory management model. Our approach is based on evidence of effective implementations in other fields,21 and includes all elements for ‘person-centred care’.22 The pilot study was recognised on the 2015 Ontario Minister of Health and Long-Term Care’s Medal Honour Roll for Excellence in Health Quality.23 24

Recent Canadian trials have tested a ‘Virtual Ward’ and a ‘transitional care services’ model in postacute adult patients (the latter with heart failure) and found no benefit.25 26 The ‘Virtual Ward Model’ cited difficulty of hospital teams to integrate with community-based care. Community-based chronic disease management can reduce hospital use.25 27 Our study diverges from this given that we focus on home care clients who are frail and not specifically ‘postacute’. Also, our intervention leverages a validated case finding tool based on real-time inputs from community-based providers rather than care from hospital-based teams.

The DIVERT-Collaboration Action Research and Evaluation (CARE) trial will adopt a pragmatic attitude to avoid the well-documented difficulty that many clinical trials have in producing results that are generalisable to real-world conditions.28 29 As our interest is in the effects of the intervention under realistic rather than optimal conditions, the intervention will be delivered in usual care settings by usual care providers for usual clients. Home care caseloads will be randomised to intervention or control rather than individual clients in order to mimic the process that would occur when clinical practice changes. Cluster randomised designs are commonly used in pragmatic trials as practice changes are implemented at levels higher than the client in real-world conditions.30 31 The DIVERT-CARE trial will also make use of secondary data sources for outcome measurement. The use of administrative data has been shown to be more accurate than client-reported results for health services utilisation and permits excellent follow-up over long periods of time without the need for intrusive follow-up procedures.32 33 A number of pragmatic, cluster-randomised trials using administrative data have appeared in the literature.34–37

This paper describes the protocol and presents the rationale for a cluster-randomised study investigating the effectiveness of a cardiorespiratory disease management model in a targeted home care client population. This paper complies with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials 2013 recommendations for clinical trial protocol reporting.38 This trial will report findings in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines.39

Methods and analysis

Study population

The trial will be conducted in partnership with three regional, public-sector, home care providers across Canada: Hamilton-Niagara-Haldimand-Brant Local Health Integration Network (HNHB LHIN) in Ontario, Western Health in Newfoundland and Island Health in British Columbia. These three Canadian jurisdictions were selected from five potential jurisdictions that expressed interest based on their geographical (West, Central and East) and political–cultural diversity. Each healthcare provider will select a number of home care caseloads to be included in the study based on historical practice patterns from each subregion including caseload size, home care enrolment and assessment patterns. A caseload represents a group of clients in a small geographical area that is served by a home care coordinator (or ‘case manager’). Recruitment and randomisation will occur at the level of the caseload and as such clients were not involved in the research strategy. Each site will select enough caseloads to enrol approximately 360 long-stay home care clients, for a total of 1100 clients over a 1.5 year time frame. We expect that over 42 distinct geographic home care caseloads will be enrolled in total.

Study design

The DIVERT-CARE trial is a pragmatic, cluster-randomised, two-arm parallel cluster, multicentre, superiority trial with a primary outcome of time to first ED visit within 6 months of the index home care clinical assessment. The unit of randomisation/intervention will be the cluster (home care caseload; figure 1: caseload randomisation schematic), while the unit of inference/measurement/analyses will be the home care client. The cluster-randomised design limits the potential for contamination and differential enrolment given that management and discretion over the use of resources is contained within each home care caseload. This design also supports the feasibility of the trial by reducing the number of resources (care providers) required to be trained in the intervention protocol. See table 1 for an overview of the trial methods and design; Protocol Version 2.1 (17 April 2017).

Figure 1.

Caseload randomisation schematic. HNHB LHIN, Hamilton-Niagara-Haldimand-Brant Local Health Integration Network.

Table 1.

WHO trial registration dataset for Detection of Indicators and Vulnerabilities of Emergency Room Trips Collaboration Action Research and Evaluation (DIVERT-CARE) Trial (as of 11 March 2019; protocol version 2.1, 17 April 2017)

| Data category | Information |

| Primary registry and trial identifying number | ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03012256 |

| Date of registration in primary registry | 6 January 2017 |

| Secondary identifying numbers | |

| Source(s) of monetary or material support | Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant Community Local Health Integration Network (Hamilton, Ontario); Western Health (Corner Brook, Newfoundland and Labrador); Island Health (Victoria, British Columbia); Canadian Frailty Network |

| Primary sponsor | McMaster University |

| Secondary sponsor(s) | None |

| Contact for public queries | Graham Campbell, MA (campbg4@mcmaster.ca) |

| Contact for scientific queries | Andrew Costa, PhD (acosta@mcmaster.ca) McMaster University |

| Public title | The DIVERT-CARE (Collaboration Action Research and Evaluation) Trial |

| Scientific title | The DIVERT-CARE (Collaboration Action Research and Evaluation) Trial: a multiprovincial pragmatic cluster randomised trial of cardiorespiratory management in home care |

| Countries of recruitment | Canada |

| Health condition(s) or problem(s) studied | Heart failure; COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder) |

| Intervention(s) |

Experimental: cardiorespiratory management model44 |

| Control: usual care/no intervention | |

| Key inclusion and exclusion criteria |

Inclusion c riteria: |

| Long-stay home care clients living in a non-institutional setting (ie, admitted to home care and receive comprehensive clinical assessment (RAI-HC)) | |

| Clients with DIVERT score of 9, 10, 14 or 15 (ie, at least one cardiorespiratory symptom (chest pain, dyspnoea, dizziness, irregular pulse) and at least one cardiac condition (congestive heart failure or coronary artery disease)) Exclusion c riteria: Clients receiving palliative care (ie, prognosis of less than 6 months to live at time of assessment (Q. K8e from RAI-HC)) Clients receiving dialysis (Q. P2g from RAI-HC) | |

| Study type |

Interventional |

| Allocation: cluster randomised intervention model. Parallel assignment, open label | |

| Primary purpose: prevention | |

| Pragmatic | |

| Date of first enrolment | 6 February 2018 |

| Target sample size | 1080 |

| Recruitment status | Recruiting |

| Primary outcome(s) | The difference in days to first unplanned emergency department visit (hazard rate; time frame: up to 6 months from baseline); the difference in total care costs controlling for length of stay (time frame: up to 6 months from baseline); changes in patient activation (patient activation questionnaire; time frame: baseline, 2 months, 4 months, 6 months); the difference in the number of symptoms (time frame: baseline, 2 months, 4 months, 6 months) |

| Key secondary outcomes | The difference in the number of unplanned emergency department visits (time frame: up to 6 months from baseline); description of health-related quality of life (quality-of-life questionnaire; time frame: 4 months, 6 months) |

RAI-HC, Resident Assessment Instrument for Home Care.

Study objectives

Our main objective is to evaluate the effectiveness and preliminary cost effectiveness of a targeted, person-centred cardiorespiratory management model. The sample size for the primary outcome was calculated to determine whether the cardiorespiratory disease management model is superior to standard of care in postponing unplanned ED visits. Additional outcomes include determining if the cardiorespiratory disease management model is superior to standard of care in improving client activation, reducing symptoms and the cost effectiveness of this model. The symptoms of interest are shortness of breath, chest pain at rest or on exertion, dizziness, perceived pain control, oedema, noticeable decrease in food/fluids consumed and unintended weight loss.

Secondary objectives include determining if the cardiorespiratory disease management model is superior to standard of care for the number of unplanned ED visits, number of unplanned hospital admissions and change in health-related quality of life (HRQOL). HRQOL will be assessed by the Minimal Data Set Health Status Index, which is a RAI-HC-derived measure based on the Health Utilities Index Mark 2 that has demonstrated longitudinal construct validity.40 41

Eligibility criteria

The pragmatic attitude of the trial warrants the broadest inclusion criteria that are feasible. To be eligible for inclusion into this trial, home care clients must possess the following characteristics:

Admitted to home care and receive comprehensive clinical assessment (RAI-HC) as part of regular home care enrolment, or reassessment.

Nineteen years or older at time of assessment.

-

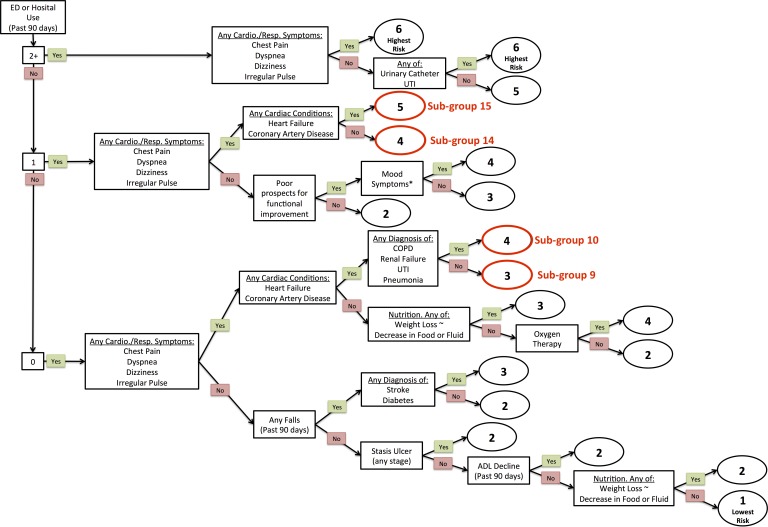

Categorised into DIVERT subgroups 9, 10, 14, or 15 (figure 2). This includes:

those with cardiorespiratory symptoms (chest pain, dyspnoea, dizziness, irregular pulse) who have a diagnosis of chronic cardiac disease and have not used an ED or hospital in the last 90 days9 10; or

those with cardiorespiratory symptoms who have had one ED or hospital exposure in the last 90 days, regardless of if they are diagnosed with chronic cardiac disease.14 15

Figure 2.

Detection of Indicators and Vulnerabilities of Emergency Room Trips scale target groups. ED, emergency department; UTI, Urinary Tract Infection

We will exclude clients with a prognosis of less than 6 months to live at time of assessment (Q. K8e from RAI-HC) and clients requiring dialysis treatment (Q. P2g from RAI-HC). The exclusion of palliative and dialysis care clients is necessary as some jurisdictions place these clients on specialised caseloads.

The eligibility criteria for the trial will result in a population that is representative of non-palliative home care clients in Canada who have cardiorespiratory symptoms and conditions. It captures approximately one-third of all assessed home care clients. However, we excluded individuals with cardiorespiratory symptoms with two or more hospital or ED episodes in the past 90 days given that they were determined in a pilot study to have exceedingly complex psychosocial needs (such as housing) that we could not address. They account for less than 4% of home care clients.

Recruitment and consent

All non-palliative, non-dialysis, adult home care clients in the trial caseloads assessed using the RAI-HC (during regular home care enrolment or reassessment) who fall into one of the four target DIVERT subgroups will be enrolled into the study by a care coordinator at the time of assessment. Eligible clients will automatically be included into the intervention or ‘regular care’ control groups on an intent-to-treat basis. Recruitment is expected to proceed over 6–9 months for each site. Analysis of the sample size simulations that were carried out on retrospective data from the HNHB LHIN region from November 2014 to June 2015 indicates an expected enrolment of four clients per caseload per month.

Each home care partners’ process for attaining consent will apply to the trial. Individual informed consent will not be sought given that the cardiorespiratory management model is accepted, considered the best practice care, and is offered—whole or in part—at the full clinical discretion of the home care provider as per existing practice. Trial investigators have no part in the data collection, individual care decision-making or record management during the study period beyond providing overall scientific guidance. We requested and received alteration to the requirements for consent based on satisfying the following Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans criteria42:

The research involves no more than minimal risk to the participants.

The alteration to consent requirements is unlikely to adversely affect the welfare of participants.

It is impossible or impracticable to carry out the research and to address the research questions properly, given the research design, if the prior consent of participants is required.

In the case of a proposed alteration, the precise nature and extent of any proposed alteration are defined.

The plan to provide a debriefing (if any) which may offer participants the possibility of refusing consent and/or withdrawing data and/or human biological materials, shall be in accordance with Article 3.7B.

Our waiver of informed consent complies with existing methodological and ethical guidelines for pragmatic cluster-randomised trials. Existing guidelines state that informed consent by clients is not needed if ‘the intervention is to the clear advantage of every person in the cluster for the cluster to be entered in the trial’.43

Intervention

Care planning and self-care support have been shown to be among the most effective elements of cardiorespiratory disease management8 10 along with sustained follow-up by nurses or non-medical staff.13 14 Care planning will be completed in a collaborative fashion among a care coordinator, the client and the client’s caregivers (both formal and informal). Clients in the intervention group will have their care plans guided by a multicomponent cardiorespiratory disease management model in addition to receiving their usual care.39 This comprehensive model for the intervention has been described in greater detail in a previous publication.44 The person-centred, multicomponent cardiorespiratory management model was developed based on guidelines,17 45 46 extensive home care client profiling and input from clients/families and health professionals. The management model contains the following components (see table 2): scheduled nurse-led self-management support (based on a training programme and tool kit); access to a staffed helpline; education on vaccines; advance care and goal planning; clinical pharmacist medication reconciliation; team case rounds; situation, background, assessment, and recommendation communication protocol with primary care; and a standardised transition package.21 44 47 Each component has a specific objective within the model; however, the manner in which it is delivered may be adapted. For example, some home care providers have clinical pharmacists on staff whereas others would rely on collaboration with community pharmacists.

Table 2.

Description of intervention components

| DIVERT-CARE intervention components | Description |

| Case finding using the DIVERT Scale | Use of the DIVERT Scale (embedded in interRAI assessment) to identify home care clients most likely to benefit. |

| Self-management education and supports | In-home assessment of self-management goals and needs, with practical education and skills training to recognise and manage symptoms. |

| Access to an immediate nurse-staffed helpline | Direct phone line staffed by nurses involved in the DIVERT-CARE intervention to aid with self-management and problem resolution. |

| Promotion of vaccines | Seasonal influenza vaccine and pneumococcal polysaccharide (Pneu-P-23) information and health promotion consistent with Canadian practice guidelines. |

| Advance care and goal planning | Consultation for advance care and goals of care planning, advanced care decisions and communication of care wishes. |

| Clinical pharmacist-led medication review | Review of medication for safety, efficacy and appropriate use of medications and delivery options. |

| Interprofessional team case rounds | Weekly or biweekly care team meeting to discuss care plan, update goals, and how to support changing care needs. |

| SBAR communication with primary care providers | SBAR formatted communication to effectively communicate disease relevant information and care updates to primary and specialist care providers. |

| Standardised ED transition package/personal care record | A succinct document to support continuity of care throughout health system. Personal care record of goals, plan of care and community supports. |

CARE, Collaboration Action Research and Evaluation; DIVERT, Detection of Indicators and Vulnerabilities of Emergency Room Trips; ED, emergency department; SBAR, situation, background, assessment, and recommendation.

Self-management education and supports will be tailored to the needs and goals of the client. As with all home care services, clients may refuse all or any of the intervention components. The components will be delivered over 15 weeks by care coordinators and nurses who have been trained by the research team. Care coordinators and nurses will be provided detailed manuals explaining the components and their role in supporting clients throughout the intervention. The self-management programme, based on previous pilot work,24 will use a population-based care approach pioneered by Wagner48 to help trial partners implement the cardiorespiratory disease management model.

The intervention adheres to the following three principles: (1) multidisciplinary teams at each site will be trained on the protocols and resources related to each component of cardiorespiratory management model; (2) the teams will identify steps required to deliver the interventions; (3) the teams will plan the deployment of the cardiorespiratory management model that engages clients, families and caregivers to ensure that adequate resources are dedicated to support the interventions across the intervention caseloads, while ensuring long-term sustainability.

Clients in the control group will receive the usual set of home care services. No changes will be made to their care planning process. Depending on the jurisdiction and client needs, usual care may include personal support, nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and other services. Depending on the jurisdiction, access to the components described in the cardiorespiratory disease management model is either non-existent or otherwise very rare and inconsistent for clients receiving usual care.

Allocation

Caseload randomisation was designed and completed centrally and not revealed to prospective sites until after all site caseloads were enrolled. Caseloads were randomised to intervention or control, and stratified by home care provider (region) and subregion (areas with similar economic status, access to care, and geography) at a 1:2 intervention to control ratio. The uneven allocation ratio increases the power of the trial while only minimally impacting operational and research resources.

A blocked allocation sequence was created via random number generation in collaboration with the biostatistics unit at St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton. The sequence features a 1:2 allocation ratio with a block of size 3. After enrolment, caseloads from each region were sorted by subregion and allocated using the sequence. In the event that the end of the clusters in a subregion did not coincide with the end of a block, the rest of the block was skipped and allocation of the next subregion started with a new block.

Data collection and outcome measures

The primary outcomes will be collected using secondary data over the 6-month observation period (see table 3). The use of routinely collected data for primary outcomes, cost and health measures limits potential for bias from lack of blinding given that neither the care team nor the trial investigators are directly involved in the collection of outcomes. These records are accurate given that they are the basis for healthcare reporting systems and payments between public home care providers and contracted service providers.

Table 3.

Routine measurement

| Activity | Staff member | Approximate time to complete | Baseline | 2 months | 4 months | 6 months |

| Assess for eligibility (If intervention caseload) (RAI-HC) |

Care coordinator | 5 min | X | |||

| Symptoms (RAI-HC) |

Care coordinator | 15 min | X | X | X | X |

| Health-related quality of life (RAI-HC) |

Care coordinator | 30 min | X | X | X | |

| Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13) | Care coordinator | 5 min | X | X | X | X |

| Administrative service and billing records (CHRIS, HCC MRR, CRMS) | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X |

| Emergency department and hospital records (NACRS, DAD) | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X |

HCC MRR: Home and Community Care Minimum Reporting Requirements (https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/forms/5502datadictionary.pdf).

RAI-HC: Resident Assessment Instrument for Home Care (https://www.cihi.ca/en/home-care).

CHRIS: Client Health and Related Information System (https://hssontario.ca/Who/Pages/protecting-your-privacy.aspx).

CRMS: Client and Referral Management System (https://www.nlchi.nl.ca/images/ProvincialCRMS_Registration_User_Guide_v2_0_2017-09-01.pdf).

NACRS: National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (https://www.cihi.ca/en/national-ambulatory-care-reporting-system -metadata).

DAD: Discharge Abstract Database (https://www.cihi.ca/en/discharge-abstract-database -metadata).

The main secondary datasets include the RAI-HC, the Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13), the Client Health and Related Information System (CHRIS), the Home and Community Care Minimum Reporting Requirements (HCC MRR), the Client and Referral Management System (CRMS), the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS) and the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD).

The RAI-HC is a standardised comprehensive assessment containing approximately 200 items and has been found to document major domains of health reliably.49–53

The PAM-1354 indicates the client’s progress through four stages as they become activated (ie, they believe their role in their own care is important, they learn enough to develop confidence to act on their own belief, they actually act and they reach the point where they can act even under stress). The PAM is a widely used measure of patient activation that has demonstrated sensitivity to health-related outcomes, including health service use.55 56

The CHRIS is the health administrative database used by Ontario’s publicly funded home care providers. It includes client assessments, documents, provider and vendor contracts, billing of services information and medical supplies and equipment rental costs.

The HCC MRR is an information management system defining a set of data elements that are reported to the British Columbia Ministry of Health by the regional health authorities. The HCC MRR captures information on clients, income and home and community care services.

The CRMS is a health information system designed to support client and referral management for clients receiving community-based services from the regional health boards in Newfoundland. It contains information on client records and clinical activity.

The NACRS contains data from all national hospital-based and community-based ambulatory care. It is collected and maintained by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), which conducts its own quality assurance procedures to ensure accuracy and completeness.

The DAD captures administrative, clinical and demographic information nationally on hospital discharges (including deaths, sign outs and transfers). It is collected and maintained by CIHI, which conducts its own quality assurance procedures to ensure accuracy and completeness.

Sample size calculations

Sample size calculation assumptions:

Primary outcome: time to first unplanned ED visit within 6 months of baseline.

HR of 0.75.

Mean size of a home care caseload: 120 clients.

Mean prevalence of DIVERT target group in each caseload: 30%.

Expected recruitment over 6 months per caseload: 30.

Mean cluster size: 30.

Allocation: 1:2 (intervention: control).

Simulations using retrospective secondary data sources were undertaken to explore the power of a hypothetical DIVERT-CARE trial conducted in the HNHB LHIN region of Ontario from December 2015 to June 2016. The simulations found that 36 HNHB home care caseloads randomised at a 1:2 intervention to control ratio could expect to enrol 1100 clients across 7 months. The simulation linked clients to their actual ED utilisation records and extended the time to first ED visit figures for clients in 12 randomly selected intervention caseloads to achieve an HR of 0.75, a figure chosen to be more conservative than the pilot study but still clinically significant. The overall event rate was 35.5% in the intervention group and 44.8% in the control. The median time to first visit was 88 days in the intervention group and 75 days in the control. The power of the simulated DIVERT trial was 81.3% with a two-sided alpha of 0.05. Simulations with an HR of 0.80 yielded a power of 60.1%. The intraclass correlation coefficient was estimated to be 0.005.

Based on the simulations, the target sample size for the trial will be 1100 clients, which will yield an approximate power of 81% for an HR of 0.75% and 60% for an HR of 0.80.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses will compare the treatment groups and sites on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics. Statistics on compliance, censoring and follow-up times will also be presented.

The primary outcome will be assessed through a multilevel proportional hazards model on an intent-to-treat basis. The dependent variable will be days until first unplanned ED visit, censored at date of home care discharge for any reason. Caseload and partner site will be included as nested random effects. Both unadjusted and adjusted results will be reported. For adjusted analysis, DIVERT subgroup, age and sex will be included as time-independent fixed effects. The HR, 95% CI and p value will be reported for the treatment group effect and covariates when applicable. A two-sided alpha level of 0.05 will be used to judge statistical significance.

The assumption of proportionality of hazards across treatment groups will be evaluated by a visual inspection of the hazard curves and statistical testing of a time-dependent treatment group effect. If the hazard curves cross or the time-dependent treatment group effect is significant (p<0.05), then primary analysis will be modified to consider treatment group as a time-varying effect.

The economic evaluation will examine total care costs, controlling for length of stay, between treatment groups to compare incremental costs to incremental effects (ie, cost per ED visit averted). Total care costs are defined as direct costs incurred by the home care provider in the provision of home care services, including: human resources and equipment. We will use a microcosting approach based on the listed/billed service cost consumed by each patient.

The other outcomes will be evaluated by multilevel generalised linear models. 4-month and 6-month changes in PAM, HRQOL, number of symptoms, number of ED visits and number of unplanned hospitalisations will be the respective dependent variables. Caseload and partner site will be included as nested random effects. Both unadjusted and adjusted results will be reported. For adjusted analysis, DIVERT subgroup, age and sex will be included as fixed effects. Unit change and rate ratios, with their associated 95% CI and p values, will be reported for the treatment group effect and covariates as applicable. A two-sided alpha level of 0.05 will be used to judge statistical significance.

Model assumptions will be evaluated by a visual inspection of residuals and the sensitivity of the results to the use of a heteroskedastic-robust variance estimator. If evidence of departure from model assumptions is present, then the analysis will be modified to use an empirical variance estimator.

Patient and public involvement

The intervention, comprehensively described elsewhere,44 was developed based on the input from clients/families and health professionals in a series of three in-person stakeholder meetings held in late 2013 and early 2014. The pilot of the study methodology was conducted in 2014 with the collaboration, input and funding from a regional, public sector, home care provider (HNHB LHIN). Participating clients and health professionals provided input into the intervention (and study design for health professionals) through telephone interviews using a structured questionnaire focused on the perceived benefit and utility of the interventions, overall satisfaction and areas for improvement. The outcomes of the pilot study were featured in the home care providers annual report to the community.

The present protocol, based on the aforementioned pilot study, received input from health professionals in each participating region through a series of in-person planning meetings in mid-2017. The general public was engaged in one region through a local radio programme. Adaptations and modifications to the intervention in each region to account for their unique health service context will be described in a forthcoming implementation publication. The experience of participating clients and health professionals will be investigated in a programme evaluation and qualitative study to be conducted in parallel. The results of the trial are expected to be released to the study participants and public though regional public reports.

Ethics and dissemination

Harm

This trial is unlikely to cause additional risk of harm since the various components of the intervention are already available from home care agencies and service providers, though rarely offered in the standard care plan. Direct risks to the health of the client are minimal as none of the components of the intervention are novel interventions. Each element of the intervention has been shown to be safe individually. Clients in the control group will continue to receive their usual care, while clients in the intervention group will receive usual care plus increased access to additional home care services defined by the cardiorespiratory treatment model. A Data Monitoring and Ethics (or equivalent) Committee was not required, and formal stopping rules or interim analyses are not planned.

Ethical approval

We have received ethics approval from the Hamilton-Integrated Research Ethics Board, Health Research Ethics Authority for Western Health, and the Clinical Research Ethics Board for Vancouver Island (see online supplementary file).

bmjopen-2019-030301supp001.pdf (43.5KB, pdf)

Results dissemination

We aim to make the results of this study public through peer-reviewed publications, clinical trial registry, thesis manuscripts, conference publications and notifications to our trial partners, who will include the findings in their regular newsletters and annual reports to clients, partners and government.

Discussion

In summary, this pragmatic, cluster-randomised, multicentre superiority trial will investigate the effectiveness of a cardiorespiratory disease management model in a targeted home care client population, with case finding occurring using the DIVERT scale.19 By offering a person-centred, multicomponent cardiorespiratory management model to home care clients at the highest levels of risk,44 we hope to determine if unplanned ED visits are postponed, clients have increased activation in their care, symptoms are reduced and that the care model is cost effective.

This pragmatic trial will inform how multicomponent cardiorespiratory care interventions are received as they are delivered in real-world conditions. Historically, trials investigating community programme have excluded frail seniors who would be at high risk of ED services. Additionally, other trials have tended to focus on postacute care and have not targeted high-risk clients when assessing community-based chronic disease management interventions.

The need for appropriate and targeted supportive chronic disease management is a clear and compelling health services issue, and is reflected in new provincial government investments into the sector. This trial will be an important precedent around the creation of more upstream approaches to care for home care clients that help to take further pressure of hospitals and EDs that are already facing issues of overcrowding across Canada.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the regional home care providers for their leadership and involvement in the study: Hamilton-Niagara-Haldimand-Brant Local Health Integration Network in Ontario, Western Health in Newfoundland, and Island Health in British Columbia.

Footnotes

Twitter: @@andrew_p_costa, @SchumacherCon, @PriddleTammy

Contributors: APC is the principal investigator and led the conceptualisation and design of the protocol, drafted, and revised the manuscript. CS, AJ, DD, MJ and GC made contributions to the design and implementation of the study, and supported the manuscript. GA, CMB, VB, SEB, DF, PCH, GH, JH, LL, RSM, LM and SS are coinvestigators that contributed to the design of the study, and revised the manuscript. JD, TP, JR, RG, DM and DH are trial partners who contributed to the design and implementation of the study. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: APC is supported by the Schlegel Chair in Clinical Epidemiology & Aging, McMaster University. This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant number 148933) and pilot funding from the Canadian Frailty Network (grant number 2015-15PB).

Disclaimer: This funding source has no role in the design of the study and will not have a role in its execution, analyses, interpretation of data, or decision to submit results.

Competing interests: It should be noted that DHF has a proprietary interest in Health Utilities Incorporated, Dundas, Ontario, Canada. HUInc distributes copyrighted Health Utilities Index materials and provides methodological advice on the use of the HUI.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Wilkins K. Government-subsidized home care. Ottawa, on: statistics Canada, 2006. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17111593 [Accessed 22 Aug 2018].

- 2. Seggewiss K. Variations in home care programs across Canada demonstrate need for national standards and pan-Canadian program. Can Med Assoc J 2009;180:E90–2. 10.1503/cmaj.090819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Health Council of Canada Seniors in need, caregivers in distress: what are home care priorities for seniors in Canada? 2012. Available: http://www.carp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/HCC_HomeCare_2d.pdf [Accessed 24 May 2018].

- 4. Jones A, Schumacher C, Bronskill SE, et al. . The association between home care visits and same-day emergency department use: a case–crossover study. Can Med Assoc J 2018;190:E525–31. 10.1503/cmaj.170892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gray LC, Peel NM, Costa AP, et al. . Profiles of older patients in the emergency department: findings from the interRAI multinational emergency department study. Ann Emerg Med 2013;62:467–74. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Salvi F, Morichi V, Grilli A, et al. . The elderly in the emergency department: a critical review of problems and solutions. Intern Emerg Med 2007;2:292–301. 10.1007/s11739-007-0081-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wagner EH, Davis C, Schaefer J, et al. . A survey of leading chronic disease management programs: are they consistent with the literature? Manag Care Q 1999;7:56–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wagner EH. More than a case manager. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:654–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-129-8-199810150-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Becker DM, Raqueño JV, Yook RM, et al. . Nurse-mediated cholesterol management compared with enhanced primary care in siblings of individuals with premature coronary disease. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1533–9. 10.1001/archinte.158.14.1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aubert RE, Herman WH, Waters J, et al. . Nurse case management to improve glycemic control in diabetic patients in a health maintenance organization. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:605–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-129-8-199810150-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:1097–102. 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson WG. Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on primary care and hospital readmission. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wasson J, Gaudette C, Whaley F, et al. . Telephone care as a substitute for routine clinic follow-up. JAMA 1992;267:1788–93. 10.1001/jama.1992.03480130104033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mukamel DB, Chou C-C, Zimmer JG, et al. . The effect of accurate patient screening on the cost-effectiveness of case management programs. Gerontologist 1997;37:777–84. 10.1093/geront/37.6.777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stuck AE, Elkuch P, Dapp U, et al. . Feasibility and yield of a self-administered questionnaire for health risk appraisal in older people in three European countries. Age Ageing 2002;31:463–7. 10.1093/ageing/31.6.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cardiac Care Network of Ontario Strategy for community management of heart failure in Ontario, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Health Quality Ontario Key observations: 2014-15 quality improvement plans community care access centres. 2014 Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Costa AP, Hirdes JP, Bell CM, et al. . Derivation and validation of the detection of indicators and vulnerabilities for emergency room TRIPS scale for classifying the risk of emergency department use in frail community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:763–9. 10.1111/jgs.13336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsasis P. Chronic disease management and the home-care alternative in Ontario, Canada. Health Serv Manage Res 2009;22:136–9. 10.1258/hsmr.2009.009002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, et al. . Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care 2001;39:II2–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered Care Person-Centered care: a definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:15–18. 10.1111/jgs.13866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care 2015 Minister’s Medal Winners, 2016. Available: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/transformation/minister_medal_2015.aspx [Accessed 18 Feb 2018].

- 24. Costa AP, Haughton D, Heckman G, et al. . The DIVERT-CARE catalyst trial: targeted chronic-disease management for home care clients. Innov Aging 2017;1:322–3. 10.1093/geroni/igx004.1190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dhalla IA, O’Brien T, Morra D, et al. . Effect of a Postdischarge virtual ward on readmission or death for high-risk patients. JAMA 2014;312:1305–12. 10.1001/jama.2014.11492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van Spall HGC, Lee SF, Xie F, et al. . Effect of patient-centered transitional care services on clinical outcomes in patients hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA 2019;321:753–61. 10.1001/jama.2019.0710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beswick AD, Rees K, Dieppe P, et al. . Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2008;371:725–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60342-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutical trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:499–505. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “To whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet 2005;365:82–93. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17670-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dickinson LM, Beaty B, Fox C, et al. . Pragmatic cluster randomized trials using covariate constrained randomization: a method for practice-based research networks (PBRNs). J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28:663–72. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.05.150001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, et al. . The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ 2015;350:h391 10.1136/bmj.h391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Anderson GL, Burns CJ, Larsen J, et al. . Use of administrative data to increase the practicality of clinical trials: Insights from the Women’s Health Initiative. Clinical Trials 2016;13:519–26. 10.1177/1740774516656579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Richards SH, Coast J, Peters TJ. Patient-Reported use of health service resources compared with information from health providers. Health Soc Care Community 2003;11:510–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2003.00457.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Richard E, Van den Heuvel E, Moll van Charante EP, et al. . Prevention of dementia by intensive vascular care (PreDIVA): a cluster-randomized trial in progress. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Dolovich L, et al. . Improving cardiovascular health at population level: 39 community cluster randomised trial of cardiovascular health awareness program (CHAP). BMJ 2011;342:d442 10.1136/bmj.d442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Steventon A, Bardsley M, Billings J, et al. . Effect of telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality: findings from the whole system Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2012;344:e3874 10.1136/bmj.e3874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Evans CD, Eurich DT, Taylor JG, et al. . A pragmatic cluster randomized trial evaluating the impact of a community pharmacy intervention on statin adherence: rationale and design of the community pharmacy assisting in total cardiovascular health (CPATCH) study. Trials 2010;11:76 10.1186/1745-6215-11-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. . Spirit 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. . Consort 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials 2010;11:32 10.1186/1745-6215-11-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wodchis WP, Hirdes JP, Feeny DH. Health-Related quality of life measure based on the minimum data set. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2003;19:490–506. 10.1017/S0266462303000424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jones A, Feeny D, Costa AP. Longitudinal construct validity of the minimum data set health status index. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018;16:102 10.1186/s12955-018-0932-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Tri-council policy statement: ethical conduct for research involving humans 2014, 2014. Available: http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/pdf/eng/tcps2-2014/TCPS_2_FINAL_Web.pdf

- 43. Medical Research Council Cluster randomised trials: methodological and ethical considerations. London: Medical Research Council, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schumacher C, Lackey C, Haughton D, et al. . A chronic disease management model for home care patients with cardio-respiratory symptoms: the DIVERT-CARE intervention. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs 2018;28:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Howlett JG, Chan M, Ezekowitz JA, et al. . The Canadian cardiovascular Society heart failure companion: bridging guidelines to your practice. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:296–310. 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. O'Donnell DE, Hernandez P, Kaplan A, et al. . Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - 2008 update - highlights for primary care. Can Respir J 2008;15:1A–8. 10.1155/2008/641965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Beckett CD, Kipnis G. Collaborative communication: integrating SBAR to improve quality/patient safety outcomes. J Healthc Qual 2009;31:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wagner EH. Population-Based management of diabetes care. Patient Educ Couns 1995;26:225–30. 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00761-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morris JN, Fries BE, Steel K, et al. . Comprehensive clinical assessment in community setting: applicability of the MDS-HC. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:1017–24. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02975.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kwan C-W, Chi I, Lam T-P, et al. . Validation of minimum data set for home care assessment instrument (MDS-HC) for Hong Kong Chinese elders. Clin Gerontol 2000;21:35–48. 10.1300/J018v21n04_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Leung AC, Liu CP, Tsui LL, et al. . The use of the minimum data set. home care in a case management project in Hong Kong. Care Manag J 2001;3:8–13. 10.1891/1521-0987.3.1.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Landi F, Tua E, Onder G, et al. . Minimum data set for home care: a valid instrument to assess frail older people living in the community. Med Care 2000;38:1184–90. 10.1097/00005650-200012000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hirdes JP, Ljunggren G, Morris JN, et al. . Reliability of the interRAI suite of assessment instruments: a 12-country study of an integrated health information system. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:277 10.1186/1472-6963-8-277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. . Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004;39:1005–26. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mosen DM, Schmittdiel J, Hibbard J, et al. . Is patient activation associated with outcomes of care for adults with chronic conditions? J Ambulatory Care Manage 2007;30:21–9. 10.1097/00004479-200701000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? an examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:520–6. 10.1007/s11606-011-1931-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030301supp001.pdf (43.5KB, pdf)