Abstract

Objective

To explore antecedents, components and influencing factors on active case-finding (ACF) policy development and implementation.

Design

Scoping review, searching MEDLINE, Web of Science, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the World Health Organization (WHO) Library from January 1968 to January 2018. We excluded studies focusing on latent tuberculosis (TB) infection, passive case-finding, childhood TB and studies about effectiveness, yield, accuracy and impact without descriptions of how this evidence has/could influence ACF policy or implementation. We included any type of study written in English, and conducted frequency and thematic analyses.

Results

Seventy-three articles fulfilled our eligibility criteria. Most (67%) were published after 2010. The studies were conducted in all WHO regions, but primarily in Africa (22%), Europe (23%) and the Western-Pacific region (12%). Forty-one percent of the studies were classified as quantitative, followed by reviews (22%) and qualitative studies (12%). Most articles focused on ACF for tuberculosis contacts (25%) or migrants (32%). Fourteen percent of the articles described community-based screening of high-risk populations. Fifty-nine percent of studies reported influencing factors for ACF implementation; mostly linked to the health system (eg, resources) and the community/individual (eg, social determinants of health). Only two articles highlighted factors influencing ACF policy development (eg, politics). Six articles described WHO’s ACF-related recommendations as important antecedent for ACF. Key components of successful ACF implementation include health system capacity, mechanisms for integration, education and collaboration for ACF.

Conclusion

We identified some main themes regarding the antecedents, components and influencing factors for ACF policy development and implementation. While we know much about facilitators and barriers for ACF policy implementation, we know less about how to strengthen those facilitators and how to overcome those barriers. A major knowledge gap remains when it comes to understanding which contextual factors influence ACF policy development. Research is required to understand, inform and improve ACF policy development and implementation.

Keywords: tuberculosis, active case-finding, health policy, policy development, policy implementation, preventive medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The scoping review design was able to provide collated and comprehensive insights into the peer-reviewed scientific literature on the topic, and included a wide scope of factors influencing active case-finding (ACF) policy development and implementation.

The review may have provided a more in-depth insight into the topic by including additional databases, searching grey literature and references of included studies, and contacting authors for more information.

We did not do a critical appraisal of the individual sources of evidence or within sources of evidence, nor did we describe sources of funding for the included articles.

We limited the inclusion to studies written in English.

Reporting of ACF policy development and implementation varied in completeness across the included articles, and as such, our data are limited by the details described in the literature.

Background

Systematic screening for tuberculosis (TB) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the ‘systematic identification of people with suspected active TB, in a predetermined target group, using tests, examinations or other procedures that can be applied rapidly’.1 Active case-finding (ACF) is synonymous with systematic screening for active TB, although it usually implies screening outside of health facilities. TB is a major global health challenge, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries. The WHO End TB Strategy and the Sustainable Development Goals aim at finding the ‘missing cases’ and ending the global TB epidemic by 2030. This will require intensified activity to increase TB case detection, specifically in ‘hard-to-reach’ groups.2 In 2019, there was a 3 million gap between estimated incident and notified TB cases globally, reflecting a combination of an underdiagnosis of cases and underreporting of cases who have been detected.3 Many people with TB are diagnosed only after long delays,4 causing suffering and economic hardship for TB patients and TB-affected households, and sustained transmission.1

ACF is mostly provider-initiated. It targets people in high-risk groups who may not seek healthcare actively.1 Potential benefits for patients include reduced morbidity, mortality and economic consequences due to earlier diagnosis, while society can benefit from reduced transmission and a reduced burden of TB, which often affects the most economically productive members of a society. TB screening in high-risk groups has been implemented in many settings within the TB programme or in the context of research and can significantly improve TB case notification.5–7

However, if not well targeted and implemented, ACF can be costly leading to diversion and waste of scarce resources, potentially compromising passive case-finding infrastructure and weakening health systems. It can also cause harm to individuals, for example, by increasing the risk of a false positive diagnosis and providing TB treatment to individuals without TB, or increased stigma and discrimination arising from uncovering TB, which need to be weighed against the benefit of identifying cases in the community that would otherwise go untreated.1 2

Questions remain about both if ACF in general is worthwhile, and how to best plan and implement outreach screening through ACF in a given context as a synergistic way, that is, integrated into the healthcare system, and not delivered separately in a parallel system. The evidence base is weak concerning the benefits and cost-effectiveness of ACF and how it varies between risk groups.8 The strength of evidence to support alternative ACF approaches is low, with few head-to-head trial results being available to inform policy and practice. Many differences exist in stakeholders' values and preferences concerning the rationale, outcomes and possible secondary effects of ACF. Despite the relatively weak evidence, WHO has a guideline on systematic TB screening and the Global Fund9 and TB REACH10 provide increasing funding for ACF, while a growing number of countries are increasing investment in and have national policies for ACF. For example, Vietnam’s National Strategic Plan 2015–2020 includes ACF in remote and congregate settings, and in high-risk groups including contacts, prisoners, miners, the elderly, homeless people, young adults, migrants, factory workers, communities, people living with HIV, multidrug-resistant patients, young males, smokers and intravenous drug users.11

The aim of this study was to explore antecedents, components and influencing factors for ACF policy development and implementation, to inform and improve future ACF policy processes. We did not aim to review the evidence on ACF per se; therefore, we explore yield, accuracy and impact only in the context of how they influence ACF policy development or implementation.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review, using an a-priori protocol based on the following research question: Which are the antecedents, components and influencing factors (barriers and facilitators) in developing and implementing ACF policies? The scoping review methodology was deemed appropriate given the breadth of the question. The protocol was based on guidance from the Joanna Briggs Methods Manual for Scoping Reviews.12 The inclusion criteria, the screening manual and the data-charting table were developed by one author (OB), reviewed by two authors (KV and KL) to ensure face validity, and pilot-tested. All team members were consulted at various stages of the scoping review to provide input on the search, data extraction and charting, and the interpretation of the results. The charted data were summarised in tables, and then condensed resulting in tables 1 and 2. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was used to guide reporting.13 The completed checklist is available in online additional file 1. The protocol is available from the corresponding author on request.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the articles included in the scoping review (n=73)

Table 2.

Barriers and facilitators for active case-finding policy implementation (n=43)

| Reported factors | References | Number (%) |

| Health system level | ||

| Limited financial resources | 16 21 22 26 27 32 39 40 43 46 48 51 54 66 78 | 15 (35) |

| Existing systems and structures | 14 19 21 27 38 43 44 53 54 69 78 | 11 (26) |

| Availability of diagnostic tests and services | 16 19 27 34 41 49 50 66 | 8 (19) |

| Staff experience, expertise, motivation | 14 17 24 26 27 39–41 43 46 52 55 58 71 | 14 (33) |

| Over-burdening staff | 16 21 26 39 41 51 70 | 7 (16) |

| Using person-centred approaches | 14 22 23 27 34 43 53 65 | 8 (19) |

| Collaboration and integration | 14 16 18 34 39 43 52 | 7 (16) |

| Health education | 34 40–43 | 5 (12) |

| Health information and research system level | ||

| Data, systems, supervision | 19 24 27–29 42 48 | 7 (16) |

| Individual and community level | ||

| Stigma and discrimination | 14 22–25 27 28 31 37 38 43 50 58 59 77 82 | 16 (37) |

| Individual characteristics | 23 31 34 37 39 43 51 58 65 66 77 83 | 12 (28) |

| Sociocultural factors | 24 25 27 28 34 41 43 46 47 54 56 59 77 83 | 14 (33) |

| Fear | 23 24 34 38 39 43 53–56 | 10 (23) |

| Mistrust | 14 24 41 43 46 47 51 53 57 72 | 10 (23) |

| Knowledge and awareness | 14 23 24 26 37 43 53 58 | 8 (19) |

bmjopen-2019-031284supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

Data sources and search

We searched MEDLINE, Web of Science, The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the WHO Library from January 1968 (year of the first publication on ACF in MEDLINE) until January 2018. The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a medical librarian from Karolinska Institutet (Carl Gornitzki), and further refined through team discussion. The search strategy for MEDLINE is available in online additional file 2. The latter was standardised but adapted to fit the other database searches. The respective search strategies are available from the corresponding author on request. The results of the literature search were imported into Rayyan.

bmjopen-2019-031284supp002.pdf (47.8KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria

Eligible studies focused on the detection of active TB disease. The review included studies describing or analysing ACF policy development and implementation. Facilitators and barriers linked to access or treatment were included, if there was a clear link to ACF. Furthermore, the review included studies analysing the use of evidence in ACF policy development and implementation. Studies of any design, conducted in any setting or country and those published in the English language were eligible for inclusion. We excluded studies focusing only on latent TB infection, passive case-finding and childhood TB, and studies about effectiveness, yield, accuracy and impact without descriptions of how this evidence has/could influence ACF policy. The inclusion of different ACF approaches implies that while many lessons can be learnt across different settings, some might not be generalisable.

Screening, data abstraction and charting

One reviewer (OB) initially reviewed titles to remove duplicates, and those studies not focusing on TB. Two reviewers (OB and KV) independently reviewed titles and abstracts, and then full-text articles for inclusion. Conflicts were resolved through discussion based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

The data-charting table was developed in Microsoft Excel. An abridged version of the table is available in online additional file 3. Data were extracted on study design, country, target population for ACF, benefits of ACF, risks of ACF, ACF antecedents, ACF policy development and implementation (use of evidence, country-level to individual-level facilitators and barriers, stakeholders involved), lessons learnt, future perspectives and future research. Relevant data were charted by one author (OB), while a second author (KV) verified this step by charting data from a random sample of studies for comparison. Differences in data-charting were resolved by discussion.

bmjopen-2019-031284supp003.pdf (110.3KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

This study is related to a qualitative study of experts and a survey of National TB Programme managers combined with a policy document review on the topic of ACF policy development and implementation which are currently under way to harness tacit knowledge on the topic. The research questions and variables for these studies were informed by the results of this scoping review. The results of this study will be presented to researchers and policy-makers in the field via targeted issue briefs. We will also share the results with the public via a video and short messages on social media.

Results

Literature search

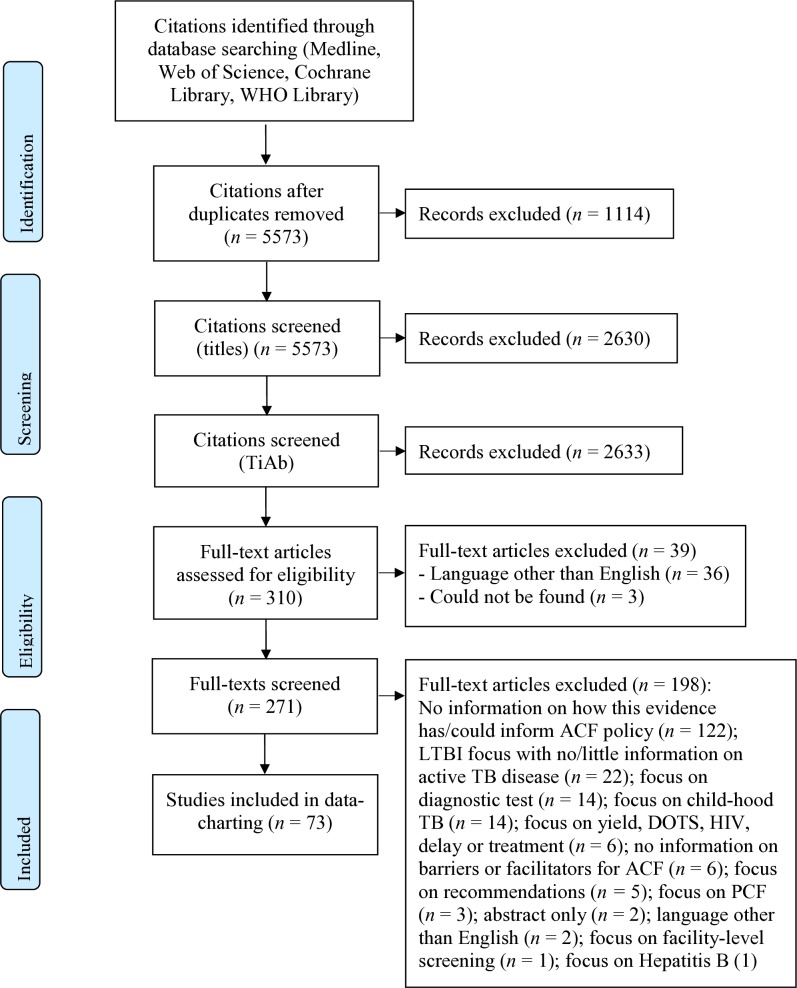

After screening 2943 titles and abstracts and 271 full-text articles, 73 unique articles fulfilled our eligibility criteria (figure 1).14–86 The reasons for excluding full-text articles are provided in figure 1. What all included studies have in common is the goal of finding ‘missing’ TB cases through ACF, while the approaches vary greatly; from contact investigation to screening people in homeless shelters (table 1). An example of a study included in this review is a qualitative study by Ayakaka et al, which explored influencing factors for TB contact investigation in Kampala, Uganda.14 The stakeholders who were interviewed described key barriers for ACF as being limited knowledge about TB among contacts, stigma, mistrust of health centre staff among index patients and contacts, and high travel costs for lay health workers and contacts. At the same time, key facilitators for ACF comprised personalised and enabling services provided by lay health workers. To overcome barriers and strengthen facilitators, the researchers identified education, incentivisation and restructuring of the service environment as relevant interventions.14

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. ACF, active case-finding; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; TB, tuberculosis.

Characteristics of the included articles (n=73)

The breadth of studies identified reflect the complexity and diversity of ACF policies and their characteristics. There has been a gradual increase in the number of articles on ACF since the first identified (eg, from 1979), and 67% (n=49/73) were published in the period 2010–2018 (table 1). The studies were conducted in all WHO regions, that is, the African region (22%, n=16/73), the Americas (North America) (14%, n=10/73), the Eastern Mediterranean region (1%, n=1/73), the European region (23%, n=17/73), South-East Asia (7%, n=5/73) and the Western Pacific region (12%, n=9/73). The most common types of articles were classified as quantitative papers (41%, n=30/73), reviews (22%, n=16/73) and qualitative studies (12%, n=9/73). The most frequent ACF target groups were contacts (25%, n=18/73) and migrants from high-incidence countries (32%, n=23/73), while 14% percent (n=10/73) of the articles focused on screening of defined communities. The remaining studies focused on different target groups which are specified in table 1.

Antecedents

ACF has been implemented for many decades primarily in high-income countries, starting with mass screening campaigns in the general population in the 1950s and 1960s, then moving towards specific risk populations in recent decades, such as migrants from high-incidence countries and prison populations.15 In low-income and middle-income countries, the interest in ACF has increased in recent years, mainly as a response to a sustained case detection gap documented in annual Global TB Reports produced by WHO3 and the emergence of new WHO guidelines.16

Generally, TB programmes have moved from traditionally vertical approaches and exclusively facility-based case-finding among people seeking care with TB symptoms (so called ‘passive case-finding’) towards being closer to the client through decentralised, community-based solutions and outreach activities, including ACF—similar to community-based testing services that have increased access to HIV testing and care.17 18

In 1976, the WHO Expert Committee on TB recommended that countries abandon indiscriminate mobile mass radiography, as evidence showed the inefficiency of population-wide screening in settings that had seen TB rates drop dramatically since the World War II.19 It should be noted that the Expert Committee emphasised that TB screening should still be done in selected risk groups.19 20

The current WHO guidelines on systematic screening for active TB were released in 2013.1 These guidelines still discourage indiscriminate mass screening and strongly recommend ACF only in selected high-risk groups, while conditionally recommending screening in other high-risk groups. Conditional recommendations are those for which the benefits are expected to outweigh the risks, while the trade-offs, such as cost-effectiveness, feasibility or affordability may be uncertain. For example, WHO has made a conditional recommendation (very low-quality evidence) for screening certain clinical risk groups in settings where the TB prevalence is over 100 per 100 000 population (while not recommending such screening in countries with a prevalence of less than 100 per 100 000 population).1 The 2013 WHO guidelines—reflected in the latest 2015 WHO’s End TB Strategy2 and aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals—put ACF back on the agenda. The guidelines provide principles for how to test and expand an approach that had been largely missing in previous global TB strategies, including the Directly Observed Treatment, Short Course Strategy from 199487 and the Stop TB Strategy 2006–2015 (although contact investigation and screening people living with HIV was included in the latter).88 Moreover, the guidelines emphasise the importance of basing ACF policy on local epidemiology and to perform careful evaluations of ACF implementation, yield and impact to improve the ACF evidence base.20 Today, ACF is considered a global health priority.21 22

Components

According to WHO,1 the main components of ACF include (1) having high-quality TB diagnosis, treatment, care, management and support for patients, as well as the capacity to scale these up (if needed), before screening is initiated; (2) prioritising risk groups; (3) choosing a suitable screening algorithm; (4) following established ethical principles; (5) optimising synergies with the delivery of other health and social services and (6) monitoring and reassessing ACF approaches.

The components of ACF, as well as those of the wider health system that ACF depends on, are well described in the literature. It is important for high-quality diagnosis, treatment, care, management, patient support and capacity for scale-up to be available.19 Risk groups must be prioritised based on assessments of benefits and risks, feasibility, acceptability, the number needed to screen to detect a case of TB and the cost-effectiveness of ACF,19 while also considering the heterogeneity of the risk group.23

The overall ACF approach must be flexible, patient-centred15 24 and culturally sensitive.25 In resource poor settings, ACF is often backed by multichannel financing mechanisms, including from international donors.26 Record-keeping, monitoring and evaluation are described as being essential.27 28 Incentives are sometimes deemed necessary, for example, for health workers,5 29 laboratory technicians,30 screening participants11 31–35 and TB patients.29 35 36 The articles also emphasised ACF-specific health education as paramount—for patients,31 37–39 their families,40 providers24 and community health workers (CHW).36 37 The training of CHWs should be followed by supervision.41 42 In addition, community involvement32 39 42 43 and social mobilisation29 are major parts of ACF. One study described how the involvement of community leaders was a key component to improve trust among patients and contacts.31

Finally, the studies underlined how vital it is to collaborate with other disease programmes,33 34 43 agencies and sectors26 27 and to integrate ACF within existing systems.18 44 The latter includes collaboration between providers and community-based organisations,43 and between HIV and TB services.45

Influencing factors

In the following section, we summarise influencing factors for ACF policy development and implementation. We chose to speak of ‘influencing factors’ rather than facilitators and barriers, as one and the same factor might be a facilitator in one context and a barrier in another, for example, health workers’ satisfaction might be a powerful facilitator for ACF,42 while the lack thereof could be a strong barrier as well.46

Influencing factors for ACF policy development

ACF policy development processes were not well described in the literature. Policy development comprises the investment of governments and donors in ACF. Only two articles reported facilitators and/or barriers for ACF policy development: politics46 47 and laws.47 Welshman46 describes how, in the mid-1950s, the Ministry of Health in the United Kingdom subverted pressure from stakeholders who were in favour of compulsory ACF at ports of entry—the Ministry ‘argued that the problem (of TB in migrants) was a minor one’ so a policy was not developed. On the other hand, laws such as the 1958 Commonwealth Migration Act were described, which made screening compulsory, and thus influenced ACF policy development in the UK.47

Influencing factors for ACF policy implementation

Policy implementation processes in the area of ACF are widely researched. In total, 43 articles reported barriers and/or facilitators for ACF implementation (table 2). Most articles mentioned factors at the level of the health system, as well as the individual and community level.

Health system level

It is fundamental to consider health system factors when putting ACF policy into practice and identifying which factors influence ACF policy implementation the most. We derived six major themes from the articles: (1) availability of financial resources, (2) existing systems and structures, (3) availability of diagnostic tests, (4) staff experience and motivation, (5) collaboration between different actors and (6) implementation of a person-centred approach.

Availability of financial resources

Many articles (35%, n=15/43) mentioned financial resources as an influencing factor for ACF policy implementation. Finances were described as being scarce at different levels of the health system,40 for the provision of staff,39 42 drugs and equipment.48

Existing systems and structures

Existing systems and structures were reported as influencing factors for ACF policy implementation by 26% (n=11/43) of the articles. Studies elaborated on the availability of health and social services14 19 and laboratory networks21 that could be used for ACF implementation.

Availability of diagnostic tests of sufficient sensitivity and specificity

Nineteen percent (n=8/43) of the articles elaborated on the availability of diagnostic tests and services as key influencing factor for ACF policy implementation—with many articles referring to the availability of molecular diagnostic tests such as Xpert MTB/RIF.27 36 49 50 Decentralisation of healthcare services, national coverage of diagnostics and task sharing were perceived as facilitators of ACF policy implementation, but unavailable in many settings.33

Staff experience and motivation

Thirty-three percent (n=14/43) of the studies described staff experience and motivation as influencing factors for ACF policy implementation. One study elaborated on how, on the one hand, staff members would feel motivated by increased case detection and awareness-raising through ACF. On the other hand, they would be frustrated when being ‘shouted at, ignored, (and) harassed’ by target communities, in this case people living in poor urban settlements.39 The over-burdening of staff was highlighted by 16% (n=7/43) of the articles, for example, leading to absenteeism,51 and thus inhibiting ACF implementation.

Collaboration between different actors

A variety of studies (16%, n=7/43) described collaboration as an important influencing factor for ACF policy implementation. One example is the collaboration between community workers, health centre staff and laboratory technicians in delivering diagnostic services as part of ACF.16 Moreover, Akkerman et al described the positive impact on diagnostic accuracy and the proportion of follow-up medical interventions when there is close collaboration with a limited number of experienced, high-volume chest radiograph readers when screening asylum seekers and other high-risk groups.52

Implementation of a person-centred approach

The need for a person-centred approach to ACF policy implementation was referred to by 19% (n=8/43) of the articles, for example, adopting approaches including healthcare providers being non-judgemental and supportive of patients and their families during diagnosis and follow-up,53 and assuring confidentiality.22 52 Another 12% (n=5/43) of the articles emphasised health education for the general public, screening participants, as well as TB patients and their families as a necessity.

Individual and community

ACF policies should be for individuals and communities and their influence on successful implementation is elaborately described in the literature. Three overarching themes emerged from the studies: (1) stigma and discrimination, (2) individual characteristics and sociocultural factors and (3) knowledge and awareness.

Stigma and discrimination

Many studies (37%, n=16/43) reported stigma and discrimination linked to TB as influencing factors for ACF policy implementation. The consequences could be the avoidant behaviour of a contact of an index TB case, such as providing incorrect phone numbers and/or wrong directions to their homes,14 or misconceptions about TB.24 43 Issues of fear, either of TB disease,23 39 53 the process of ACF,54 or the wider implications of being identified as a TB case, for example, through migrant screening programmes, where being diagnosed with TB case has in some instances resulted in deportation.34 38 55 56 Studies also reported the lack of trust of patients and their families as key barrier for ACF policy implementation41 51—not only for early diagnosis, but for the sustained commitment to addressing social determinants of TB.57

Individual characteristics and sociocultural factors

Twenty-eight percent (n=12/43) of the articles mentioned the social characteristics of the persons screened as key influencing factors for ACF policy implementation, for example, for ensuring equitable access to care21 39 58 and promoting conducive health-seeking behaviour.23 41 43 Moreover, the articles frequently reported sociocultural factors and language (33%, n=14/43) as influencing factors for ACF policy implementation. Culture was commonly described as a barrier to ACF policy implementation,34 41 59 for example, if cultural beliefs would negatively influence the receptiveness to community health workers’ advice. Only one study mentioned culture as a facilitator for putting ACF into practice, for example, if culture meant respect towards professional authority.59

Knowledge and awareness

Finally, 19% (n=8/43) of the articles reported factors related to knowledge and awareness as influencing factors for ACF policy implementation. One such factor could be the understanding of the purpose of ACF.24 Also, knowledge and awareness are closely linked to persisting stigma and discrimination, for example, Ayakaka et al 14 describe how health workers attributed TB-associated stigma to a lack of general knowledge in the community about TB.

Discussion

Characteristics of the included articles

We identified 73 articles addressing antecedents, components and/or influencing factors for ACF policy development and implementation. The included studies originated from all WHO regions. Africa and Asia are home to 90% of the 30 high TB burden countries (53% and 37%, respectively),89 which may explain why studies were more frequently conducted in these continents: 22% of the studies were conducted in Africa, 12% in the Western-Pacific region and 7% in South-East Asia. Studies conducted in the European region (23%) were predominantly about different forms of migrant screening. There was no study from Latin America among the 73 included articles, and there were no articles in the Spanish language among those excluded.

Most studies were published after 2010, which may be a result of programmes implementing WHO guidelines on systematic screening1 as well as the growing number of prevalence surveys in different settings.39 We classified 41% of the articles as quantitative, for example, cross-sectional and cohort studies, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness studies, randomised controlled trials and programme evaluations. The next most common study types were reviews (22%) and qualitative studies (12%). The first qualitative studies on our topic were published in 2003.24 54 We only identified two mixed-methods studies, one published in 201342 and one in 2015.39 The mixed-methods design combined with quantitative ACF evaluation might become more commonly used to explore the complexity of ACF policy development and implementation in the future, as it has the potential to both increase contextual understanding and reduce biases.

Among the broad range of possible target groups for ACF, most of the articles focused either on TB contacts or migrants. The focus on the latter was mainly in low-incidence countries and may be a result of long-standing national health and migration policies supporting these types of screening. Yet, other studies covered vulnerable groups, such as homeless people, people living with HIV or people living in congregate settings, as well as the urban poor. Some articles included analysis of more than one high-risk group. There were no studies on indiscriminate mass screening. However, there were studies targeting broad communities, for example, communities with high HIV prevalence.

Antecedents

Despite the growing number of studies (eg, operational studies), there is still a relative lack of evidence about the health benefits for individuals, the epidemiological impact and cost-effectiveness of different ACF approaches. Nonetheless, the interest in ACF has clearly increased in recent years. The persistent case detection gap, the 2013 WHO guidelines on systematic screening1 and ACF being mentioned as a core component of the End TB Strategy2 seem to have motivated countries to include ACF in national TB strategies. Universal Health Coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals have only marginally been mentioned as important for stepping up the TB response.33 However, the Sustainable Development Goals—which aim to ‘leave no one behind’—might have contributed to a greater interest in ACF to leave no undiagnosed TB patients behind.

Not having enough evidence to drive ACF policy development and implementation means that decisions to embark on ACF rely largely on stakeholders’ tacit knowledge, experience, values and preferences. Demonstrated screening yield in the same or other settings could also motivate further ACF implementation, although the number of cases detected may not be a relevant public health impact measure in itself. The above-mentioned WHO guidelines use the term ‘indirect evidence’.1 Strong ‘direct evidence’ exists that early diagnosis and correct TB treatment reduce morbidity, mortality and transmission. This can constitute, for example, ‘indirect evidence’ for ACF, based on the logic that if ACF leads to early detection and treatment, then it should also lead to better health outcomes and less transmission, despite the lack of trial data demonstrating a direct health impact of ACF. Similar reasoning can be used to describe potential harms associated with ACF, for example, based on modelling of the risk of false positive TB diagnoses in different epidemiological contexts. ‘Indirect evidence’, tacit knowledge, experience, values and preferences are likely to be important antecedents for national policy.

Components

The components of ACF policy, and of the system which ACF is part of, are complex. The articles reported on the prerequisites of the given system, its resources,46 capacity30 42 and tools.90 However, they also elaborated on the need for integrating ACF into health systems,41 60 as well as educating and engaging healthcare providers,5 21 communities,12 29 39 44 screening participants35 and TB patients and their families25 34 35 for ACF implementation to succeed. All components seem indispensable for successful ACF policy development and implementation. Yet, in real-life settings, rarely all components are in place.

Which ACF components are essential and which are non-essential? The 2013 WHO guidelines on systematic screening list six key principles for screening for active TB, the first principle being: ‘Before screening is initiated, high-quality TB diagnosis, treatment, care, management and support for patients should be in place, and there should be the capacity to scale these up further to match the anticipated rise in case detection that may occur as a result of screening’.1 Yet, countries might not even completely adhere to this very first principle, for example, due to a lack of resources, before a country embarks on ACF policy development and implementation.

Influencing factors

Scarce research on ACF policy development

Our findings indicate a paucity of research focusing specifically on ACF policy development. The only two factors described— politics and laws—were mentioned by the same author in two different articles and concerned migrant TB screening in a low-incidence country.46 47

Even though not documented as such in the literature, data on the epidemiological situation of a country and local evidence regarding impact are assumed to be key factors influencing ACF policy development.1 These types of data and evidence are needed to identify high-risk groups90 and devise appropriate screening algorithms. An assessment of the epidemiological situation might be based on data from regularly collected data sets or prevalence surveys, and WHO has developed a tool to help countries estimate screening yield and costs based on such data to identify appropriate risk groups and approaches.91

Interestingly, the evolution of the funding landscape for ACF, for example, through TB REACH, has not been explicitly mentioned as an influencing factor for ACF policy development or implementation, though it has been a likely game-changer. TB REACH is a case-finding initiative funded largely by Global Affairs Canada and coordinated by the Stop TB Partnership.92 The initiative has both funded ACF activities and raised awareness about the importance of ACF. It has contributed to the local evidence base, while the uptake of the evidence generated by TB REACH may be considered but not mentioned in the studies included in this review. Four articles mentioned TB REACH as funder of their research, with the disclaimer that the initiative had no role in study design, data collection and analysis.16 42 60 61 Other publications acknowledged its role in implementing ACF when describing the study methods, for example, that TB REACH funded door-to-door screening39 or the implementation of different ACF models62 and that the initiative upgraded an ACF strategy by introducing new diagnostics which still have limited availability in many settings (eg, Xpert MTB/RIF).36 It is important to reflect on and document the influence that TB REACH, other international funding mechanisms and technical agencies have on ACF policy development and implementation.

ACF policy and social determinants of health

Many barriers and facilitators for implementing ACF policies lie at the level of communities and individuals. These factors include social determinants such as the educational level,14 35 employment status27 63 and access to care64 of the target population. These factors can limit an individual’s or a community’s participation in ACF. ACF policies cannot be put in practice successfully if implementation barriers prevail. However, rather than talking about ‘missing cases’ and communities that are ‘hard to reach’, it may be useful to consider if health services are missing or hard to reach instead.

Individuals or communities may be ACF target groups precisely because health services are missing or hard to reach. As such, ACF could be a way to by-pass access barriers, for example, by using mobile units. Yet, even when designing services to be more accessible, target populations may still not come forward, take the next step of referral to complete the diagnostic pathway or adhere to treatment due to socioeconomic barriers.

We argue that ACF polices thus must be designed and implemented with careful consideration of social determinants in a given context to avoid possible harm. Whitehead and Dahlgren93 described how interventions designed to help vulnerable populations may be ‘implemented in such a way as to stigmatize the very people the programme was designed to help and, in so doing, push them to avoid the help on offer.’

A comprehensive view on ACF policies

A comprehensive approach in developing and implementing ACF policies is required that includes health education as an important component to ACF policies, and that ensures collaboration between key stakeholders, both between patients and providers, and between providers and local health authorities, between agencies, and across sectors and disease programmes.

Although this review focused on the factors that influence ACF policy and implementation, it is important to also reflect on how ACF policy influences its context in return, for example, not only factors at the level of the community and the individual, but at the level of the health system and beyond; How may the ACF policy increase or decrease stigma in a community? How may ACF policy influence the human and financial resources available in a health system? Only then may we see the real impact of ACF and be able to make equitable decisions in policy development and implementation processes.

Future research

This scoping review demonstrated that while we know much about facilitators and barriers for ACF policy implementation, we know less about how to strengthen those facilitators and how to overcome those barriers. A major knowledge gap remains when it comes to understanding which contextual factors influence ACF policy development.

Limitations

Our scoping review has some limitations. To increase the feasibility, we limited the search to MEDLINE, Web of Science, The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the WHO Library. We did not do a critical appraisal of the individual sources of evidence or within sources of evidence, nor did we describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence. Such appraisals and descriptions would have allowed us to discover the scarcity of research and to characterise the quality of and gaps in the evidence base and enable the development of robust recommendations. We leave these questions for future systematic reviews to address.

We acknowledge that we may have been able to provide a more in-depth overview of antecedents, components and influencing factors for ACF policy development and implementation by including additional databases, searching grey literature and references of included studies, and contacting authors for more information, which could be included in a future systematic review. However, we believe that our review still adds value to the current body of knowledge on ACF, by providing collated and comprehensive insights into the peer-reviewed scientific literature. We also limited the inclusion to studies written in English, which may have resulted in the exclusion of eligible studies in other languages, for example, Spanish. Furthermore, the results from this scoping review are only up to date as of 31 January 2018. The data were extracted by one reviewer only. However, the data are likely valid, as a pilot-test was conducted prior to embarking on data extraction with members of the study team. A second reviewer verified a random selection of the data.

Another limitation was that the included articles often did not distinguish between the implementation of an ACF policy versus the implementation of an ACF programme or intervention. This is likely due to inconsistent use of the terms in the literature. As such, our results are likely applicable to both. Furthermore, the reporting of ACF policy development and implementation varied in their completeness across the included articles, and as such, our data are limited by the details described in the literature, for example, most papers described steps to implementation, but did not provide details on non-response or unsuccessful practices. There is a risk of publication bias.

Conclusions

We identified some main themes regarding the antecedents, components and influencing factors for ACF policy development and implementation. However, evidence remains scarce especially concerning policy development. Research on ACF is required to understand, inform and improve policy development and implementation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

OB is funded by the EU-Horizon 2020-funded IMPACT-TB project (grant 733174). The authors thank Carl Gornitzki, medical librarian at Karolinska Institutet, for supporting the development of the search strategy, and Gabriella Ekman, writing instructor at Karolinska Institutet’s University Library for her valuable feedback in writing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Twitter: @olibiermann

Contributors: OB, KL, MC and KV conceived the study. OB developed the search strategy together with a medical librarian from Karolinska Institutet. OB and KV screened titles and abstracts, and then full-text articles. OB extracted, charted, analysed and interpreted the data. KV verified the data extraction by charting data from a random sample of studies for comparison. OB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KL, MC and KV were consulted at various stages of the scoping review to provide input on the search strategy, data extraction, charting, analysis and the interpretation of the results, and provided comments on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the EU-Horizon 2020-funded IMPACT-TB project (grant 733174).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. World Health Organization Systematic screening for active TB: principles and recommendations. Switzerland, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization Implementing the end TB strategy: the essentials. Switzerland, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization Global TB report 2019. Switzerland, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Storla DG, Yimer S, Bjune GA. A systematic review of delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. BMC Public Health 2008;8:15 10.1186/1471-2458-8-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blok L, Sahu S, Creswell J, et al. . Comparative meta-analysis of tuberculosis contact investigation interventions in eleven high burden countries. PLoS One 2015;10:e0119822 10.1371/journal.pone.0119822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Creswell J, Codlin AJ, Andre E, et al. . Results from early programmatic implementation of Xpert MTB/RIF testing in nine countries. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:2 10.1186/1471-2334-14-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Creswell J, Sahu S, Blok L, et al. . A multi-site evaluation of innovative approaches to increase tuberculosis case notification: summary results. PLoS One 2014;9:e94465 10.1371/journal.pone.0094465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kranzer K, Afnan-Holmes H, Tomlin K, et al. . The benefits to communities and individuals of screening for active TB disease: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013;17:432–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Global Fund World Health organization and stop TB partnership strategic initiative, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/tb/joint-initiative/en/ [Accessed 8 Apr 2019].

- 10. Stop TB Partnership TB REACH, 2019. Available: http://www.stoptb.org/global/awards/tbreach/ [Accessed 8 Apr 2019].

- 11. National TB Control Program National strategic plan for TB control for the period 2015-2020. Vietnam, Hanoi: Ministry of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Joanna Briggs Institute Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. . PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ayakaka I, Ackerman S, Ggita JM, et al. . Identifying barriers to and facilitators of tuberculosis contact investigation in Kampala, Uganda: a behavioral approach. Implement Sci 2017;12:33 10.1186/s13012-017-0561-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eang MT, Satha P, Yadav RP, et al. . Early detection of tuberculosis through community-based active case finding in Cambodia. BMC Public Health 2012;12:469 10.1186/1471-2458-12-469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lorent N, Choun K, Thai S, et al. . Community-Based active tuberculosis case finding in poor urban settlements of Phnom Penh, Cambodia: a feasible and effective strategy. PLoS One 2014;9:e92754 10.1371/journal.pone.0092754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Godfrey-Faussett P, Ayles H. Can we control tuberculosis in high HIV prevalence settings? Tuberculosis 2003;83:68–76. 10.1016/S1472-9792(02)00083-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Corbett EL, MacPherson P. Tuberculosis screening in high human immunodeficiency virus prevalence settings: turning promise into reality. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013;17:1125–38. 10.5588/ijtld.13.0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lönnroth K, Corbett E, Golub J, et al. . Systematic screening for active tuberculosis: rationale, definitions and key considerations. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013;17:289–98. 10.5588/ijtld.12.0797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zenner D, Hafezi H, Potter J, et al. . Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening migrants for active tuberculosis and latent tuberculous infection. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2017;21:965–76. 10.5588/ijtld.16.0935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Golub JE, Mohan CI, Comstock GW, et al. . Active case finding of tuberculosis: historical perspective and future prospects. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2005;9:1183–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kerrigan D, West N, Tudor C, et al. . Improving active case finding for tuberculosis in South Africa: informing innovative implementation approaches in the context of the Kharitode trial through formative research. Health Res Policy Syst 2017;15:42 10.1186/s12961-017-0206-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swigart V, Kolb R. Homeless persons' decisions to accept or reject public health disease-detection services. Public Health Nurs 2004;21:2:162–70. 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.021210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shrestha-Kuwahara R, Wilce M, DeLuca N, et al. . Factors associated with identifying tuberculosis contacts. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003;7:S510–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de Vries SG, Cremers AL, Heuvelings CC, et al. . Barriers and facilitators to the uptake of tuberculosis diagnostic and treatment services by hard-to-reach populations in countries of low and medium tuberculosis incidence: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:e128–43. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30531-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li J, Liu X-Q, Jiang S-W, et al. . Improving tuberculosis case detection in underdeveloped multi-ethnic regions with high disease burden: a case study of integrated control program in China. Infect Dis Poverty 2017;6:151 10.1186/s40249-017-0365-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baxter S, Goyder E, Chambers D, et al. . Interventions to improve contact tracing for tuberculosis in specific groups and in wider populations: an evidence synthesis. Health Serv Deliv Res 2017;5:1–102. 10.3310/hsdr05010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Van den Bosch CA, Roberts JA. Tuberculosis screening of new entrants; how can it be made more effective? J Public Health Med 2000;22:220–3. 10.1093/pubmed/22.2.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hinderaker SG, Rusen ID, Chiang C-Y, et al. . The fidelis initiative: innovative strategies for increased case finding. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:1:71–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Erkens C, Slump E, Kamphorst M, et al. . Coverage and yield of entry and follow-up screening for tuberculosis among new immigrants. Eur Respir J 2008;32:153–61. 10.1183/09031936.00137907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tupasi TE, Radhakrishna S, Co VM, et al. . Bacillary disease and health seeking behavior among Filipinos with symptoms of tuberculosis: implications for control. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2000;4:1126–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cook VJ, Shah L, Gardy J. Modern contact investigation methods for enhancing tuberculosis control in Aboriginal communities. Int J Circumpolar Health 2012;71:18643 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Suthar AB, Zachariah R, Harries AD. Ending tuberculosis by 2030: can we do it? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2016;20:1148–54. 10.5588/ijtld.16.0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tankimovich M. Barriers to and interventions for improved tuberculosis detection and treatment among homeless and immigrant populations: a literature review. J Community Health Nurs 2013;30:83–95. 10.1080/07370016.2013.778723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ayles H, Muyoyeta M, Du Toit E, et al. . Effect of household and community interventions on the burden of tuberculosis in southern Africa: the ZAMSTAR community-randomised trial. Lancet 2013;382:1183–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61131-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morishita F, Yadav R-P, Eang MT, et al. . Mitigating financial burden of tuberculosis through active case finding targeting household and neighbourhood contacts in Cambodia. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162796 10.1371/journal.pone.0162796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fox GJ, Loan LP, Nhung NV, et al. . Barriers to adherence with tuberculosis contact investigation in six provinces of Vietnam: a nested case-control study. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:103 10.1186/s12879-015-0816-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kulane A, Ahlberg BM, Berggren I. ‘It is more than the issue of taking tablets’: the interplay between migration policies and TB control in Sweden. Health Policy 2010;97:26–31. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lorent N, Choun K, Malhotra S, et al. . Challenges from tuberculosis diagnosis to care in community-based active case finding among the urban poor in Cambodia: a mixed-methods study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0130179 10.1371/journal.pone.0130179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Karki B, Kittel G, Bolokon I, et al. . Active community-based case finding for tuberculosis with limited resources: estimating prevalence in a remote area of Papua New Guinea. Asia Pac J Public Health 2017;29:17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Getnet F, Hashi A, Mohamud S, et al. . Low contribution of health extension workers in identification of persons with presumptive pulmonary tuberculosis in Ethiopian Somali region pastoralists. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:193 10.1186/s12913-017-2133-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yassin MA, Datiko DG, Tulloch O, et al. . Innovative community-based approaches doubled tuberculosis case notification and improve treatment outcome in southern Ethiopia. PLoS One 2013;8:e63174 10.1371/journal.pone.0063174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Seedat F, Hargreaves S, Friedland JS. Engaging new migrants in infectious disease screening: a qualitative semi-structured interview study of UK migrant community health-care leads. PLoS One 2014;9:e108261 10.1371/journal.pone.0108261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sekandi JN, Dobbin K, Oloya J, et al. . Cost-effectiveness analysis of community active case finding and household contact investigation for tuberculosis case detection in urban Africa. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117009 10.1371/journal.pone.0117009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kranzer K, Lawn SD, Meyer-Rath G, et al. . Feasibility, yield, and cost of active tuberculosis case finding linked to a mobile HIV service in Cape town, South Africa: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001281 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Welshman J. Compulsion, localism, and pragmatism: the Micro-Politics of tuberculosis screening in the United Kingdom, 1950–1965. Soc Hist Med 2006;19:295–312. 10.1093/shm/hkl002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Welshman J, Bashford A. Tuberculosis, migration, and medical examination: lessons from history. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:282–4. 10.1136/jech.2005.038604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mor Z, Lerman Y, Leventhal A. Pre-immigration screening process and pulmonary tuberculosis among Ethiopian migrants in Israel. Eur Respir J 2008;32:413–8. 10.1183/09031936.00145907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Abubakar I, Stagg HR, Cohen T, et al. . Controversies and unresolved issues in tuberculosis prevention and control: a low-burden-country perspective. J Infect Dis 2012;205(Suppl 2):S293–300. 10.1093/infdis/jir886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dierberg KL, Dorjee K, Salvo F, et al. . Improved detection of tuberculosis and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among Tibetan refugees, India. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:463–8. 10.3201/eid2203.140732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Harper I, Fryatt R, White A. Tuberculosis case finding in remote mountainous areas--are microscopy camps of any value? Experience from Nepal. Tuber Lung Dis 1996;77:384–8. 10.1016/S0962-8479(96)90107-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Akkerman OW, de Lange WCM, Schölvinck EH, et al. . Implementing tuberculosis entry screening for asylum seekers: the Groningen experience. Eur Respir J 2016;48:261–4. 10.1183/13993003.00112-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Southern A, Premaratne N, English M, et al. . Tuberculosis among homeless people in London: an effective model of screening and treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1999;3:1001–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chemtob D, Leventhal A, Weiler-Ravell D. Screening and management of tuberculosis in immigrants: the challenge beyond professional competence. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003;7:959–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brewin P, Jones A, Kelly M, et al. . Is screening for tuberculosis acceptable to immigrants? A qualitative study. J Public Health 2006;28:253–60. 10.1093/pubmed/fdl031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. MacPherson DW, Gushulak BD. Balancing prevention and screening among international migrants with tuberculosis: population mobility as the major epidemiological influence in low-incidence nations. Public Health 2006;120:712–23. 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lönnroth K, Migliori GB, Abubakar I, et al. . Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Eur Respir J 2015;45:928–52. 10.1183/09031936.00214014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mayo K, White S, Oates SK, et al. . Community collaboration: prevention and control of tuberculosis in a homeless shelter. Public Health Nurs 1996;13:2:120–7. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1996.tb00229.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tardin A, Dominicé Dao M, Ninet B, et al. . Tuberculosis cluster in an immigrant community: case identification issues and a transcultural perspective. Trop Med Int Health 2009;14:9:995–1002. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Datiko DG, Yassin MA, Theobald SJ, et al. . Health extension workers improve tuberculosis case finding and treatment outcome in Ethiopia: a large-scale implementation study. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000390 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Khan K, Hirji MM, Miniota J, et al. . Domestic impact of tuberculosis screening among new immigrants to Ontario, Canada. Can Med Assoc J 2015;187:E473–81. 10.1503/cmaj.150011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Adejumo AO, Azuogu B, Okorie O, et al. . Community referral for presumptive TB in Nigeria: a comparison of four models of active case finding. BMC Public Health 2016;16:177 10.1186/s12889-016-2769-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Azman AS, Golub JE, Dowdy DW. How much is tuberculosis screening worth? estimating the value of active case finding for tuberculosis in South Africa, China, and India. BMC Med 2014;12:216 10.1186/s12916-014-0216-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bell TR, Molinari NM, Blumensaadt S, et al. . Impact of port of entry referrals on initiation of follow-up evaluations for immigrants with suspected tuberculosis: Illinois. J Immigr Minor Health 2013;15:673–9. 10.1007/s10903-013-9779-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. O'Hara NN, Roy L, O'Hara LM, et al. . Healthcare worker preferences for active tuberculosis case finding programs in South Africa: a Best-Worst scaling choice experiment. PLoS One 2015;10:e0133304 10.1371/journal.pone.0133304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wright CW. An opinion survey of tuberculosis case-finding procedures. S Afr Med J 1979;56:6:224–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Layton MC, Cantwell MF, Dorsinville GJ, et al. . Tuberculosis screening among homeless persons with AIDS living in single-room-occupancy hotels. Am J Public Health 1995;85:11:1555–9. 10.2105/AJPH.85.11.1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hogan H, Coker R, Gordon A, et al. . Screening of new entrants for tuberculosis: responses to Port notifications. J Public Health 2005;27:192–5. 10.1093/pubmed/fdi019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Klinkenberg E, Manissero D, Semenza JC, et al. . Migrant tuberculosis screening in the EU/EEA: yield, coverage and limitations. Eur Respir J 2009;34:1180–9. 10.1183/09031936.00038009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tan L, Altman RD, Nielsen NH, et al. . Screening nonimmigrant visitors to the United States for tuberculosis: report of the Council on scientific Affairs. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:334–40. 10.1001/archinte.161.3.334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Alvarez GG, Gushulak B, Abu Rumman K, et al. . A comparative examination of tuberculosis immigration medical screening programs from selected countries with high immigration and low tuberculosis incidence rates. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:3 10.1186/1471-2334-11-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bloss E, Newbill K, Peto H, et al. . Challenges and opportunities in a tuberculosis outbreak investigation in southern Mississippi, 2005-2007. South Med J 2011;104:731–5. 10.1097/SMJ.0b0.3e318232679e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Corbett EL, Bandason T, Duong T, et al. . Comparison of two active case-finding strategies for community-based diagnosis of symptomatic smear-positive tuberculosis and control of infectious tuberculosis in Harare, Zimbabwe (DETECTB): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376:1244–53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61425-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mhimbira FA, Cuevas LE, Dacombe R, et al. . Interventions to increase tuberculosis case detection at primary healthcare or community-level services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;11:CD011432 10.1002/14651858.CD011432.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Fox GJ, Nhung NV, Sy DN, et al. . Household-contact investigation for detection of tuberculosis in Vietnam. N Engl J Med 2018;378:221–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1700209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Fox GJ, Barry SE, Britton WJ, et al. . Contact investigation for tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2013;41:140–56. 10.1183/09031936.00070812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Honarvar B, Odoomi N, Rezaei A, et al. . Pulmonary tuberculosis in migratory nomadic populations: the missing link in Iran's national tuberculosis programme. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014;18:272–6. 10.5588/ijtld.13.0650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kranzer K, Houben RM, Glynn JR, et al. . Yield of HIV-associated tuberculosis during intensified case finding in resource-limited settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:93–102. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70326-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lönnroth K, Mor Z, Erkens C, et al. . Tuberculosis in migrants in low-incidence countries: epidemiology and intervention entry points. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2017;21:624–36. 10.5588/ijtld.16.0845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mallick G, Shewade HD, Agrawal TK, et al. . Enhanced tuberculosis case finding through advocacy and sensitisation meetings in prisons of central India. Public Health Action 2017;7:67–70. 10.5588/pha.16.0109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mulder C, Erkens CGM, Kouw PM, et al. . Missed opportunities in tuberculosis control in the Netherlands due to prioritization of contact investigations. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:177–82. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Mwansa-Kambafwile J, McCarthy K, Gharbaharan V, et al. . Tuberculosis case finding: evaluation of a paper slip method to trace contacts. PLoS One 2013;8:e75757 10.1371/journal.pone.0075757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ospina JE, Orcau A, Millet J-P, et al. . Community health workers improve contact tracing among immigrants with tuberculosis in Barcelona. BMC Public Health 2012;12:158 10.1186/1471-2458-12-158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Smit GSA, Apers L, Arrazola de Onate W, et al. . Cost-effectiveness of screening for active cases of tuberculosis in Flanders, Belgium. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:1:27–35. 10.2471/BLT.16.169383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Szkwarko D, Mercer T, Kimani S, et al. . Implementing intensified tuberculosis case-finding among street-connected youth and young adults in Kenya. Public Health Action 2016;6:142–6. 10.5588/pha.16.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS. Tuberculosis: active case finding survey in an urban area of India, in 2012. J Res Health Sci 2013;13:1:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. World Health Organization What is dots? A guide to understanding the WHO-recommended TB control strategy known as dots. Switzerland, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 88. World Health Organization Building on and enhancing dots to meet the TB-related millennium development goals. Switzerland, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 89. World Health Organization Use of high burden country Lists for TB by who in the post-2015 era. Switzerland, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 90. World Health Organization Towards TB elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. WHO/ HTM/TB/2014.13. Switzerland, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Miller CR, Mitchell EMH, Nishikiori N, et al. . A web-based tool for prioritizing risk groups and selecting algorithms for screening for active tuberculosis. Submitted. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 92. Stop TB Partnership , 2019. Available: http://www.stoptb.org/ [Accessed 25 Mar 2019].

- 93. Whitehead M, Dahlgren G. Concepts and principles for tackling social inequities in health: levelling up Part 1. World Health organization collaborating centre for policy research on social determinants of health, University of Liverpool. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031284supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-031284supp002.pdf (47.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-031284supp003.pdf (110.3KB, pdf)