Abstract

Objectives

Although clinical learning is pivotal for nursing education, the learning process itself and the terminology to address this topic remain underexposed in the literature. This study aimed to examine how concepts equivalent to ‘learning in practice’ are used and operationalised and which learning activities are reported in the nursing education literature. The final aim was to propose terminology for future studies.

Design

The scoping framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley was used to answer the research questions and address gaps in the literature. Two systematic searches were conducted in PubMed, EBSCO/ERIC and EBSCO/CINAHL between May and September 2018: first, to identify concepts equivalent to ‘learning in practice’ and, second, to find studies operationalising these concepts. Eligible articles were studies that examined the regular learning of undergraduate nursing students in the hospital setting. Conceptualisations, theoretical frameworks and operationalisations were mapped descriptively. Results relating to how students learn were synthesised using thematic analysis. Quality assessment was performed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist.

Results

From 9360 abstracts, 17 articles were included. Five studies adopted a general, yet not explained, synonym for learning in practice, and the other approaches focused on the social, unplanned or active nature of learning. All studies used a qualitative approach. The small number of studies and medium study quality hampered a thorough comparison of concepts. The synthesis of results revealed five types of learning activities, acknowledged by an expert panel, in which autonomy, interactions and cognitive processing were central themes.

Conclusions

Both theoretical approaches and learning activities of the current body of research fit into experiential learning theories, which can be used to guide and improve future studies. Gaps in the literature include formal and informal components of learning, the relation between learning and learning outcomes and the interplay between behaviour and cognitive processing.

Keywords: undergraduate nursing education, learning in practice

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study followed a rigorous design, using an established research framework, a comprehensive two-step search strategy and a well-documented selection process.

The analysis of both conceptualisations, study quality and study results allowed for the identification of quantitative and qualitative gaps in the literature.

A limitation is that the literature search only covered undergraduate nursing education in the hospital setting, while a comparison with literature on learning in practice in other health professions would enrichen our understanding of potential conceptualisations.

Introduction

Learning in the clinical setting is crucial for becoming a competent nurse.1 However, although a vast body of knowledge exists on factors that influence learning, the process itself remains underexposed in the literature.2 Understanding learning in the clinical setting can help design, supervise and evaluate individual learning trajectories. In the nursing education literature, just as in other health professions education literature, different terms are used to describe and study learning in clinical practice, with different underlying theoretical or conceptual frameworks.

This study aimed to examine how different concepts equivalent to ‘learning in practice’ are used and operationalised and which learning activities are reported in the nursing education literature. The final aim was to propose a terminology to guide future studies. To our knowledge, the only study that included distinct concepts of clinical learning in the health setting in a review before was a concept analysis of work-based learning in healthcare education from 2009.3 The authors identified common attributes, enabling factors and consequences of workplace learning and proposed a definition. The current review built on this work by critically examining the use of these concepts within the context of undergraduate nursing education and by analysing their outcomes.

To enable comparison of the literature, this study focused on undergraduate students in the general hospital setting. This context is the traditional setting for nursing training and offers a wide array of multidimensional learning opportunities4 through the presence of different healthcare professionals and students, as well as complex and acute patients. Moreover, this study is limited to undergraduate (also called bachelor, diploma or associate degree) education, which is the initial training that prepares for registration as a nurse, in which students learn the profession and shape their identity. As a final demarcation allowing for the contrasting of concepts, we focused on studies about how students learn during their regular day to day work at the ward, instead of evaluations of specific interventions or models.

Methods and analysis

The scoping review approach was chosen, as it can help understand complex concepts through clarifying definitions and conceptual boundaries5 and enables to identify key concepts and gaps in the literature.6 The approach developed by Arksey and O'Malley7 and refined by Levac et al 8 and the Joanna Briggs Institute9 was used, consisting of the six stages: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting studies; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results and (6) expert consultation. Reporting on this scoping review followed the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Review checklist,10 as outlined in online supplementary file 1. The review followed an a priori developed research protocol11 (see online supplementary file 2) with a little deviation by choosing the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist12 over the quality indicators of Buckley et al,13 as this allowed for more specific and systematic quality assessment. As anticipated, study questions and refined inclusion criteria were added during the search process.

bmjopen-2019-029397supp001.pdf (63.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029397supp002.pdf (175.2KB, pdf)

Stage 1. Identifying the research question

The original research question was:

‘How are different concepts that are used as an equivalent to learning in the hospital setting operationalised in the undergraduate nursing education literature?’

As scoping is an iterative process,7 the following research question was added based on the findings along the search process:

‘Which activities do undergraduate nursing students learn from in the clinical setting?’

Stage 2. Identifying relevant studies

As suggested by the Joanna Briggs Institute,9 a comprehensive search strategy was iteratively developed (by MS and JCFK) following the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies 2015 guideline statement,14 starting with a broad search (search step 1) to inform the subsequent search strategy (search step 2). The different search queries were first developed for PubMed and later extended to EBSCO/ERIC and EBSCO/CINAHL. See our search strategy for both steps in online supplementary file 3.

bmjopen-2019-029397supp003.pdf (173.2KB, pdf)

In search step 1, from inception to May 2018, the terms ‘learning in clinical practice’ and ‘undergraduate nursing students’ were combined to identify concepts that are used as an equivalent to ‘learning in clinical practice’ and that could be included in the second search step. Eligible concepts were those relating to the process of clinical learning rather than specific aspects of it or associated factors. The first 200 abstracts were screened by the two reviewers (MS and RAK) independently to extract potentially eligible concepts. As the two reviewers reached full agreement on potentially eligible concepts within these first 200 abstracts, the first reviewer screened the rest of the abstracts. After all abstracts had been screened, all concepts were discussed between the two reviewers and a final selection of concepts to be included in the second search step was made. Disagreements were resolved through comparison of the concepts with the inclusion criteria, based on their use within the abstract. Potentially eligible concepts of which the meaning remained unclear after discussion were also added to the list of concepts to be used in search step 2. Other concepts coming up during the search and selection process that appeared eligible were added to the selection of concepts after discussion between the reviewers. See online supplementary file 4 for concepts and reason for inclusion/exclusion in the second search step.

bmjopen-2019-029397supp004.pdf (63.2KB, pdf)

In search step 2, between May and September 2018, each of the identified concepts was combined with ‘undergraduate nursing students’ to find studies operationalising these concepts in the literature about nursing students’ learning in practice. After these two searches, reference lists of included studies were checked for additional publications meeting inclusion criteria.

Stage 3. Study selection

Two researchers (MS and RAK) independently screened abstracts from search step two and assessed the eligibility for full text retrieval. Selected full-text studies were compared between the reviewers with disagreements being resolved through discussion and consensus and with input from the full research team.

The inclusion criteria were developed iteratively. The initial inclusion criteria were:

Original research or reviews in peer reviewed journals that have learning in undergraduate clinical nursing practice in the hospital setting as one of their main topics, regardless of publication date and type of article.

Studies that examine how students learn in the clinical hospital setting.

In line with the aim of the study, the inclusion criteria were refined to:

Original research or reviews in peer reviewed journals, regardless of publication date, type of article and study quality, that examine the learning of undergraduate nursing students in the clinical hospital setting as it regularly occurs.

This results in the following exclusion criteria:

Studies:

evaluating organisational models or interventions,

about factors influencing learning in clinical practice, including supervision styles, teaching methods and clinical learning environment,

outside the general hospital setting,

about very specific student populations, patient populations or settings (eg, palliative care) generating results that might be limited to that setting,

about interprofessional learning,

about the acquisition of specific skills,

about student’s ‘experience’ of clinical learning without explicit reference to the learning process.

As the study aimed to examine how learning in practice is operationalised in peer-reviewed research, books, book reviews, commentaries, letters to the editor, PhD theses and reports were excluded.

Stage 4. Charting the data

Selected studies were documented including study characteristics (year, country, methodology, study question, study design, participants, outcomes), conceptualisation of learning in practice (definitions, theoretical underpinnings/rationale, operationalisations), results, learning activities and study quality. Two researchers piloted and refined the data extraction form on the first five studies. The completed form was discussed in the research team for accuracy and validity. Learning activities were extracted by two reviewers independently (MS and RAK), and the other variables were initially charted by the first reviewer and checked by the second reviewer. Learning activities were separated from other study results by going through the result sections of the studies and underlining findings (themes, observations, quotes) that referred to how nursing students learn in the hospital setting. When possible, the original wordings were used in the data chart. Colloquial expressions that lost meaning outside the context of the article were slightly rephrased. Although formal assessment of study quality in scoping reviews is debated,6 9 quality assessment of included studies by the CASP checklist12 was decided on to address qualitative gaps in the literature.8

Stage 5. Collating, summarising and reporting results

Data were analysed in two ways. First, descriptive accounts of concepts, theories, subsequent operationalisations and study quality were given and compared. Second, a data-driven thematic analysis of learning activities was conducted.15 These findings were categorised using open coding. All the results were compared and consolidated through consensus between MS and RAK.

Stage 6. Expert consultation

In order to confirm our findings, we presented our analysis of the learning activities to four experts of different institutions in the Netherlands (a senior clinical educator, a coordinator of clinical education, a head of nursing education department and a coordinator of nursing education). Short semistructured (telephone) interviews were conducted, in which a written summary of the findings was presented and respondents were asked (1) whether they recognised the findings, (2) whether they missed anything and (3) whether they had any other comments on the findings.

Patient and public involvement

As education is essential for improving patient care, patients will eventually benefit from the body of knowledge this study contributes to. However, specific interests of patients have not been investigated. Patients have not been involved in the design or the conduct of the study. The consulted experts can be considered participants of this study and will be informed about the results as soon as it has been published.

Results

Search results

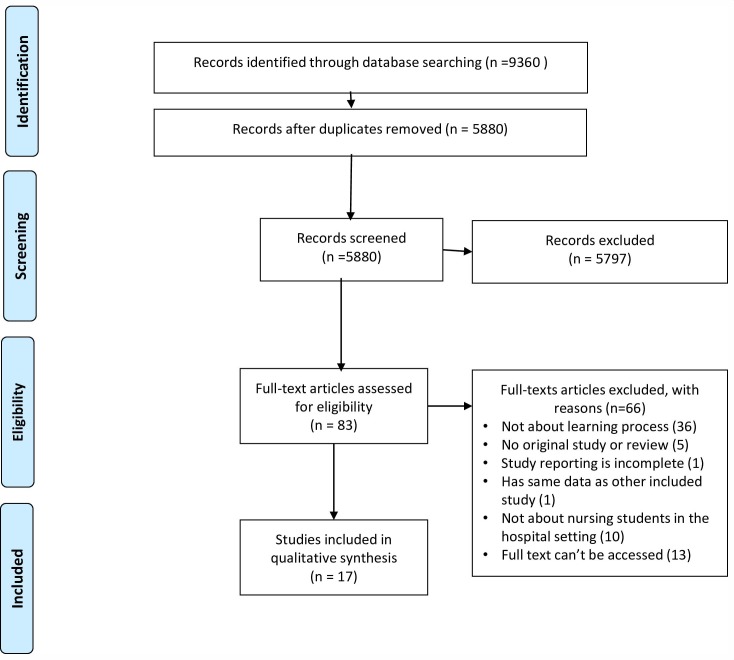

This initial search to identify concepts yielded 7211 abstracts, of which 5658 remained after removing duplicates. As the two reviewers (MS and RAK) reached full agreement on potentially eligible concepts after screening the first 200 abstracts, the remaining abstracts were screened by MS only. Seventy potentially eligible concepts were extracted. After discussion between the reviewers, 22 concepts were selected, to which 3 concepts were added later in the process, so the second search was run with 25 different concepts. See online supplementary file 4 for concepts and reason for inclusion/exclusion in search step 2. The second search, using the 25 concepts selected in the initial search, generated 9360 results of which 5880 remained after duplicates were removed. A total of 83 abstracts were selected for full text reading and 17 studies were included (see online supplementary file 5 for excluded full texts and reason for exclusion). Three pairs of studies were based on (partly) overlapping data,16–21 but were all included as the results only partly overlapped. Reference list screening of the full text articles did not generate any extra results. See figure 1 for a flow diagram of search step 2.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram article screening and selection search step 2.

bmjopen-2019-029397supp005.pdf (141.9KB, pdf)

General study characteristics

All included studies examined the process of undergraduate nursing students’ learning in the clinical setting, as a result of their primary aim or as a significant secondary finding of a broader research question. Six of the studies18–23 investigated undergraduate nursing students’ learning in both the classroom setting and the clinical setting. One of the studies included nursing students and midwifery and social work students.24 However, data presentation in the current study is restricted to findings concerning nursing students in the clinical setting. All were primary studies, of which 16 were qualitative studies and 1 mixed methods.21 Publication year ranged from 1987 to 2018. Studies were conducted in different countries in Europe, Middle East, North America and Oceania.

Study quality

Table 1 shows the quality of the included studies as assessed with the CASP tool.12 In the only mixed method study included,21 the quantitative data were analysed only descriptively and were used to inform the qualitative data. Therefore, this study was also appraised with the CASP. To summarise, in the majority of studies, it was unclear how the results answered the research question, because of a lack of clear aims, lack of clear operationalisation or both, in spite of clear descriptions of the process of data analysis and its outcomes.

Table 1.

Quality of the included studies as assessed with the CASP12 tool

| Baraz et al 32 | Burnard20 | Burnard21 | Carey et al 29 | Dadgaran et al 25 | Gidman24 | Grealish and Ranse26 | Green and Holloway22 | Kear18 | Kear19 | Manninen16 | Manninen et al 17 | Mayson and Hayward31 | Roberts30 | Seylani et al 23 | Stockhausen27 | Windsor28 | |

| Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | No | No |

| Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes |

| Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | No | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Can’t tell | Yes | Can’t tell | No | No | No |

| Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | Yes | can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | No | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Is there a clear statement of findings? | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

CASP, Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.

Concepts, operationalisations and learning activities

Table 2 summarises the main concepts, operationalisations, frameworks, findings and learning activities of the 17 selected studies. Findings concerning conceptualisation and operationalisation as well as the results concerning learning activities will be discussed in the following paragraphs.

Table 2.

Main concepts, operationalisations, frameworks, findings, learning activities of the included studies

| Conceptualisation | Operationalisation | Learning activities | ||||

| Main term(s) used to describe learning in practice Definition, if provided, in italics |

Main concept studied

Definition, if provided, in italics |

Theoretical or conceptual framework for interpreting results/explicit reference to learning theories | Summary of operationalisation | Main study results, arranged according to the studies’ objectives | Learning activities for nursing students in the hospital setting, identified by the reviewers in the studies’ result sections | |

| Baraz et al

32

(2014) |

Learning process in clinical setting | Learning styles in clinical setting Individual’s preferred methods of knowledge and skill acquisition and information organisation |

No theoretical framework, used, reference to Kolb’s stages of experiential learning | Semistructured interviews about what and how students learn in the clinical setting | Three clinical learning styles

|

|

| Burnard21 | Clinical experiences | Experiential learning ‘Experiential learning’ has been used to describe many different sorts of educational approaches ranging from the use of interactive group strategies) to accrediting people for their life experience when considering those people for entrance to courses |

No theoretical framework, used, reference to Kolb’s stages of experiential learning | In-depth interviews about how students perceive experiential learning | Definitions of experiential learning:

|

|

| Burnard20 | Clinical experiences | Experiential learning No definition provided with justification: ‘it appears that the term can be used by different people in different ways’ |

No theoretical framework, used, reference to Kolb’s stages of experiential learning | Interviews about how students and tutors experience experiential learning and questionnaire about perceptions of experiential learning | Experiential learning

Students mostly relate experiential learning to learning in the clinical setting. |

|

| Carey et al 29 | Learning in clinical settings/learning within the clinical practice environment; Clinical learning | Peer-assisted learning in which students acquire skills and knowledge through the active help provided by status equals or matched companions (Topping, 2005). | – | Observation of interaction patterns between students | Three themes contributing to impact of peer-assisted learning:

|

|

| Dadgaran et al 5 | Clinical learning | Clinical learning | – | Semistructured interviews about how students experience their clinical learning; subsequent observations of students in the clinical setting with a focus on interactions | Five categories and one ‘core variable’: 1. Facing unfavourable clinical facts 2. Analysis of a clinical situation and appropriate decision making

Two approaches to learning:

|

|

| Gidman24 | Learning in practice | Learning from patient stories | No theoretical framework, used, reference to Eraut’s theory on informal learning | Conversational interviews about students’ perceptions of their learning experiences of listening to patient stories |

|

|

| Grealish and Ranse26 | Learning in the workplace, clinical learning | Learning in the clinical workplace | Community of practice | Students’ written narratives about where they learnt while on clinical placement | Three thematic constructs, called ‘learning triggers’:

|

|

| Green and Holloway22 | Learning in the clinical setting | Experiential learning | No theoretical framework, used, reference to Kolb’s stages of experiential learning | Non-directive interviews about students' understanding, experience and interpretation of experiential learning | Six themes:

|

|

| Kear18 | Clinical experience | Transformative learning The process of critically reflecting on previous assumptions or understandings in order to determine whether one still holds them to be true or challenges their claims (Mezirow) |

Transformative learning | Students’ stories about how they experienced their learning | On analysis of the narrative data, five threads emerged from the interviews with the participants:

|

|

| Kear19 | Clinical experiences | Transformative learning Changes in meaning perspectives that have developed over an individual's lifetime based on their life experiences (Mezirow, 2000) |

Transformative learning | Students’ stories about how they experienced their learning | On analysis of the narrative data, five threads emerged from the interviews with the participants:

|

|

| Manninen et al 17 | Learning process in clinical practice; learning through participation and dialogue; learning in clinical practice; learning at a clinical education ward | Experiences of learning at a clinical ward | Authenticity and transformative learning | Semistructured interviews of how students experienced their encounters with others | Two main themes:

|

|

| Manninen16 | Learning in clinical practice | Nursing students’ learning in relation to encounters with patients, supervisors, peer students and other healthcare professionals | Transformative learning and concepts of authenticity and threshold | Semistructured interviews and group interviews of students’ experience of their learning with a focus on their encounters with others. Observations with follow-up interviews about student-patient encounters and about supervision | The results show that the core of student meaningful learning is the experience of both external and internal authenticity. External authenticity refers to being in a real clinical setting meeting real patients. Internal authenticity is about the feeling of belonging and really contributing to patients’ health and well-being |

|

| Mayson and Hayward31 | Clinical practice experiences | Learning from hidden curriculum Hidden curriculum involves the experience and application of theory and the wider social context relates to the practice development |

Hidden curriculum | Semistructured interviews about clinical areas and persons that have been beneficial for students’ learning as well as descriptions of their learning |

Given a lack of a summary of important themes, I extracted these findings myself

|

|

| Roberts30 | Clinical learning; informal on-the job learning | Peer learning Peer learning involves students learning from each other |

No theoretical framework, used, reference to Eraut’s theory on informal learning and Melia’s theory of professional socialisation | Observation of students in clinical practice with a focus on peer interactions | Themes:

|

|

| Seylani et al 23 (2012) | Clinical experiences | Informal learning Informal or indirect learning can occur as a function of observing, retaining and replicating behaviours during educational experiences |

– | Semistructured interviews about what changes students experienced during their study apart from theoretical and practical knowledge | Five categories of students’ experiences:

|

|

| Stockhausen27 | Learning in the workplace | Learning in the workplace | No theoretical framework, used, reference to Kolb’s stages of experiential learning | Students’ journals and reflective group debriefings comprehending reflections on clinical experiences | Themes

|

|

| Windsor28 | Learning in the contextual setting of clinical practice | Clinical learning experience | Focused interviews about how nursing students perceive their clinical experiences | Main categories of learning: nursing skills, time management, professional socialisation. A pattern of student development through three phases |

|

|

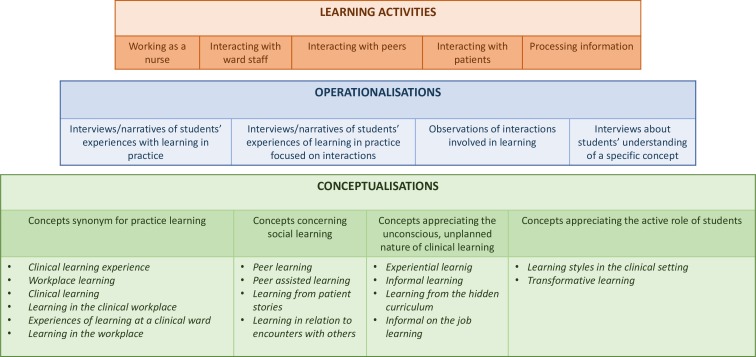

Conceptualisations

Main concepts

To analyse how learning in practice was approached, we compared the main concepts of study, usually reflected in the aims of the paper. Five of the papers studied a concept that was a synonym for learning in clinical practice such as clinical learning experience or workplace learning.17 25–28 However, in none of these studies the concept was defined or justified. The remaining 11 studies examined a specific concept related to learning in general, which was studied within the context of clinical practice. In four of the studies, this concept concerned social learning, either in general or from specific groups that are naturally present in the nursing ward.16 24 29 30 In five of the studies, the non-conscious, unplanned nature of learning was explicitly targeted by the concepts of experiential, informal and hidden curriculum learning.20–23 31 The remaining studies focused on the active role of the student in learning by investigating learning styles,32 or a specific combination of both the process and effects of learning as reflected in the concept of transformative learning.18 19

Theoretical frameworks

The five studies that used a theoretical or conceptual framework to structure the study, used Wenger’s community of practice26 or Mezirow’s transformative learning theory.16–19 Three of the studies tried to extend on existing theories using a grounded theory approach.20 21 25 The remaining nine studies discussed their research questions and findings in the light of previous literature relevant for their specific study,22 23 27 28 some of them referring to theories about learning such as Eraut’s theory of informal learning, Melia’s theory of professional socializsation,30 or Kolb’s learning cycle.20–22 27 32

Operationalisations

Nine studies used interviews, narratives or both to address students’ experiences of learning in general18 19 25 26 31 32 or specifically learning from interactions.16 17 24 The different approaches shared a semistructured nature, in which a few main topics were introduced by the researcher, to which students could bring up their ideas and experiences. Some authors20–22 combined an exploration of what students understood by experiential learning, with an examination of their actual experiences in experiential learning. Finally, in three of the studies, learning was operationalised by the observation of interactions between nursing students and peers or colleagues that play a role in learning.16 29 30

Comparison of conceptualisations and operationalisations

Most of the studies, apart from the ones that focus on social interactions, adopted a very open approach to examine learning in practice, irrespective of the concepts and theoretical frameworks used. This resulted in a variety of overlapping outcomes. Together with the small number of studies, a thorough comparison of the suitability of different concepts was difficult. However, the overarching focus on students’ personal, unplanned learning experience as a result of social interactions, suggests that the use of concepts derived from constructivist and social-cultural theories are most appropriate for studying clinical learning in nursing education.33

Learning activities

The thematic analysis allowed us to extract the following classes of activities that are observed or reported to contribute to learning during the daily presence of students in the nursing ward.

Working as a nurse

Interacting with ward staff

Interacting with peers

Interacting with patients

Processing information.

1. Working as a nurse

Students learn by actively engaging in nursing practice, including gaining responsibility for designing care plans, organising care, practicing skills and delivering patient care themselves,18 20–22 25–27 32 within a supportive environment.26 Several studies explicitly report how the importance of working independently evolves throughout training.16 17 25 28 It should be noted that this theme may overlap with the other themes and might reflect a more general characteristic of learning in practice.

2. Interacting with ward staff

Students learn by observing both good and poor examples of registered nurses, listening to them and choosing which one could serve as a role model.18–21 23 26–28 31 32 Students learn from other professionals on the ward, for example, by listening to their discussions during rounds17 28 32 or receiving feedback.26 Besides observing nurses, students learn from sharing their work experiences with resident nurses and questioning them.25 27 28 32

3. Interacting with peers

Students learn from peers by working together, questioning each other, sharing experiences, observing each other at work18 22 29 31 32 and teaching each other.30 They pass on implicit rules by asking for advice and guidance. Through discussing standards in practice, development plans and practical issues they challenge each other and expand their knowledge.29 Through dividing the work between them, students optimise their exposure to different learning situations.29

4. Interacting with patients

Listening to patients and building relationships is reported as an activity that students learn from.16–18 22 24 26 31 Providing end-of-life care contributes to students’ learning,18 19 23 as well as caring for specific patient groups such as those with different religious beliefs, communication problems, extensive needs, chronic illnesses or who visibly suffer.16–18 23 27 32 Concrete activities that are regarded to be valuable include involving the patient in the nursing process,17 assisting them with little things,26 giving medication, doing postoperative observations and performing simple tasks such as making a bed as long as they can be done independently.26

5. Processing information

A final class of activities refers to how students look up, process and store information related to patient care and their learning process. Reflecting on nursing practice promotes learning,20–22 27 32 sometimes supported by a journal or a portfolio.22 More specifically, students reflect by analysing and comparing nursing practice and thinking how to improve it, making connections with theory and previous experience.18 19 25 27 32 Negative experiences such as not being able to answer questions, witnessing poor practice, making mistakes and emotion evoking encounters, stimulate students to reflect and expand their knowledge and skills.17 18 23 26 30 Students benefit from going through textbooks18 25 28 and patient charts,28 32 as a preparation for the work shift or for specific activities such as patient education.

Summary of results

Figure 2 summarises the findings regarding conceptualisations, operationalisations and learning activities.

Figure 2.

Conceptualisations, operationalisations, learning activities scoping review.

Expert consultation

All four experts acknowledged the synthesised learning activities as the core of clinical training. One of them added a nuance that some activities automatically promote learning (‘learning by doing’), while others require support by staff (eg, ‘peer learning’). Moreover, one of them noted that experiences may only result in learning after the learning has been made conscious. Compared with their ideal vision of practice learning, another expert missed the active role of the student in creating learning opportunities, as well as formalised elements of learning, such as the formulation of learning goals and the elaboration of theory learnt in school. However, this was something they missed in their own daily practice as well. Finally, two experts noted that the ‘supervisor’ role of the resident nurse was referred to minimally; it appeared that resident nurses were primarily observed as role models. Two of the experts were surprised by the notion that negative experiences are repeatedly mentioned as learning opportunities.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine how different concepts equivalent to ‘learning in practice’ are operationalised and which learning activities are reported in the nursing education literature. The final aim was to propose a terminology to guide future studies. The scoping approach allowed for identification of gaps in the current literature.7 Five of the 17 reviewed studies adopted a general, yet unexplained, synonym for learning in practice as their object of study, the others approached learning in practice focusing on the social, unplanned and active nature of learning. These foci are in line with the broader literature on practice learning in healthcare education.3 34 Regardless of conceptualisations, all studies adopted a qualitative approach, resulting in various, yet overlapping themes. A closer examination of learning activities that were reported throughout the results, revealed five classes of activities that are congruent with separate bodies of literature on the importance of increasing independence,35 interaction with others,36 learning from authentic situations with patients and reflection37 as well as with experiences from our expert panel.

Our eventual aim was to make suggestions about the use of terminology in future research. The use of various terms for the same phenomenon may be inherent to the existence of different learning theories,34 that each lack explanatory power to inform all aspects of clinical education.38 Unfortunately, as the poor alignment within most studies resulted in similar operationalisations and results irrespective of the concepts used, specific recommendations about how to use these concepts are hard to make on the basis of the current literature. Yet, when considering overarching trends, all concepts and learning activities in the current body of research fit well into a constructivist approach to learning and more specifically experiential learning theories.34 Building on educational theorists like Piaget and Dewey,33 experiential learning theories cover both cognitive and sociocultural approaches to learning,34 sharing the idea that learning evolves from doing, in an individual trajectory that is not predefined, in constant interaction with others, in which reflection and the interaction between theory and practice are central.3 34 Although some of the studies in the current research did use experiential theories or referred to them,20–22 27 32 a more systematic and justified use of these theories and underlying concepts to frame and interpret research, would benefit future research. For instance, as was commented by one of the experts we consulted, the interactions between behaviour and cognitive processing were underexposed in the current literature. Cognitive approaches of experiential learning building on the work of Kolb39 could offer useful models to study and interpret these interactions. Given the body of work on experiential learning theories including their application in different stages of (medical) education, further elaboration on these theories can add to our understanding of learning and can help design and evaluate learning interventions in and outside the ward.40 41

Although some studies demonstrated how students actively interact with their environment by discussing inconsistencies, asking questions, and reflecting on undesirable role models, few of them offered examples of students actively creating learning opportunities or negotiating what and how to learn. This is in line with literature showing that students often focus on task completion and fitting into the team at the expense of deepening, broadening and self-regulating their learning.42–44 Future studies should continue to address both individual and environmental factors that affect students’ ability to actively and critically navigate through their clinical placements. In line with our previous recommendations, approaching clinical learning as ‘experiential learning’ may help seeing it as a pathway for personal development rather than getting students adapted to the current work in the ward.45 A next step would be to identify individual preferences and behaviours in appreciating learning opportunities. Caution has to be taken though in labels such as ‘learning styles’ as one of the studies32 did, in the absence of an accurate description of how this has been interpreted.

Not surprisingly, there were frequent references to the informal or hidden nature of clinical learning. As this learning occurs partly unconsciously, it is a challenging subject to define and study.46 In the reviewed studies, informal learning was addressed by what it is not (ie, theoretical and practical knowledge), and hidden curriculum was described by learning resources that were not reported by participants.31 Formal or formalised activities in the clinical area (such as peer teaching and doing ‘clinical homework’) were not labelled as such. As both formal and informal learning coexist in the practice setting and the dichotomy between the two has been questioned,47 clear definitions of these concepts are required, with which the different activities that student engage in throughout the day can be classified.

In most of the studies, potential or desirable learning outcomes were not articulated and were not separated from outcomes such as professional identity formation or well-being. Studies that did include the intended effect of learning in their definitions, as those of Kear,18 19 did not critically revisit if these outcomes were indeed reported. The lack of predefined outcomes in clinical learning48 and the scope of this review excluding articles confined to skills performance49 or assessment,50 might explain why learning outcomes received relatively little attention in the reviewed studies. However, critically discussing the learning process in relation to actual and desirable outcomes, with reference to the body of literature on this topic, would improve our understanding of clinical learning.

In this review, clinical learning has been studied from the viewpoint of the student as a learner, as opposed to the perspective of external factors affecting students’ learning. However, as both this review and previous literature have demonstrated,2 learning is a social process that is highly dependent on the environment. If students feel supported by the team they will be more willing to take responsibility and actively create learning opportunities.43 51 The current work adds to our understanding of the student’s role within the complex structure of clinical nursing education and can be a starting point for future research on how individual interactions between students and their environment promote learning.

Limitations

The variety of concepts, processes, definitions and outcomes associated with learning in clinical practice proved challenging in determining the boundaries of our search. The selection was influenced by choice of terminology and framing by the authors of the studies. This review therefore provides insight into the current use of terminology as well as caveats in applying it. Limiting to nursing in the hospital setting excluded us from both theoretical and experimental research on practice learning in other health professions. However, this focus enabled us to synthesise specific findings from the different studies. The approach can be of interest for other health professions and will eventually allow for comparison of the literature. Finally, our synthesis of learning activities is based on studies with heterogeneity in populations, setting and year of publication, in which the same type of activity might have a different meaning. As we reinterpreted some of the data, caution has to be taken in drawing firm conclusions.52 Nevertheless, as the findings were recognised by experts and correspond with existing literature, the categories found are a good starting point for further study.

Conclusion

This review provides an overview of how learning in clinical practice has been addressed in the undergraduate nursing education literature and which learning activities are reported. The studies share a constructivist approach to learning, but offer little guidance for the use of specific terminology in future studies due to a lack of alignment within the studies. Studies consistently reveal the importance of working independently, learning from peers, professionals and patients and the cognitive appraisal of learning. Both the approaches and reported learning activities fit well into experiential learning theories. There is still uncertainty about formal and informal components of learning and how they should be studied, as well as about desirable outcomes of clinical learning and how to incorporate them in research. Given the importance of students’ active engagement in learning as well as their reflection on it, behavioural and cognitive aspects of learning as well as their interactions should be explicitly addressed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @r_kusurkar

Contributors: MS, RAK, HEMD, SMP and JCFHK contributed to the research idea and study design and edited and revised the paper. MS and JCFHK developed the search strategy and executed the search. MS and RAK identified and agreed eligible papers and extracted the data. MS wrote the manuscript. RAK led the supervision of the project.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Cope P, Cuthbertson P, Stoddart B. Situated learning in the practice placement. J Adv Nurs 2000;31:850–6. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flott EA, Linden L. The clinical learning environment in nursing education: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:501–13. 10.1111/jan.12861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manley K, Titchen A, Hardy S. Work-based learning in the context of contemporary health care education and practice: a concept analysis. Pract Dev Health Care 2009;8:87–127. 10.1002/pdh.284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bisholt B, Ohlsson U, Engström AK, et al. . Nursing students' assessment of the learning environment in different clinical settings. Nurse Educ Pract 2014;14:304–10. 10.1016/j.nepr.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:1386–400. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:48 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 2010;5 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews In: A E, M Z, eds Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer's manual: the Joanna Briggs Institute. eds, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. . PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stoffels M, Peerdeman SM, Daelmans HEM, et al. . Protocol for a scoping review on the conceptualisation of learning in undergraduate clinical nursing practice. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024360 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme CASP qualitative checklist 2018. Available: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ accessed august 2018

- 13. Buckley S, Coleman J, Davison I, et al. . The educational effects of portfolios on undergraduate student learning: a best evidence medical education (BEME) systematic review. BEME guide No. 11. Med Teach 2009;31:282–98. 10.1080/01421590902889897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. . PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;75:40–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, et al. . Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:45–53. 10.1177/135581960501000110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Manninen K. Experiencing authenticity - the core of student learning in clinical practice. Perspect Med Educ 2016;5:308–11. 10.1007/s40037-016-0294-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Manninen K, Welin Henriksson E, Scheja M, et al. . Authenticity in learning – nursing students’ experiences at a clinical education ward. Health Educ 2013;113:132–43. 10.1108/09654281311298812 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kear TM. An investigation of transformative learning experiences during associate degree nursing education using narrative methods, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kear TM. Transformative learning during nursing education: a model of interconnectivity. Nurse Educ Today 2013;33:1083–7. 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burnard P. Student nurses' perceptions of experiential learning. Nurse Educ Today 1992;12:163–73. 10.1016/0260-6917(92)90058-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burnard P. Learning from experience: nurse tutors' and student nurses' perceptions of experiential learning in nurse education: some initial findings. Int J Nurs Stud 1992;29:151–61. 10.1016/0020-7489(92)90005-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Green AJ, Holloway DG. Student Nurses’ Experience of Experiential Teaching and Learning: towards a phenomenological understanding. Journal of Vocational Education & Training 1996;48:69–84. 10.1080/0305787960480105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Seylani K, Negarandeh R, Mohammadi E. Iranian undergraduate nursing student perceptions of informal learning: a qualitative research. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2012;17:493–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gidman J. Listening to stories: valuing knowledge from patient experience. Nurse Educ Pract 2013;13:192–6. 10.1016/j.nepr.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dadgaran SA, Parvizy S, Peyrovi H. Passing through a Rocky way to reach the Pick of clinical competency: a grounded theory study on nursing students' clinical learning. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2012;17:330–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grealish L, Ranse K. An exploratory study of first year nursing students' learning in the clinical workplace. Contemp Nurse 2009;33:80–92. 10.5172/conu.33.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stockhausen LJ. Learning to become a nurse: students' reflections on their clinical experiences. Aust J Adv Nurs 2005;22:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Windsor A. Nursing students' perceptions of clinical experience. J Nurs Educ 1987;26:150–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carey MC, Chick A, Kent B, et al. . An exploration of peer-assisted learning in undergraduate nursing students in paediatric clinical settings: an ethnographic study. Nurse Educ Today 2018;65:212–7. 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roberts D. Learning in clinical practice: the importance of peers. Nurs Stand 2008;23:35–41. 10.7748/ns.23.12.35.s55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mayson J, Hayward W. Learning to be a nurse. The contribution of the hidden curriculum in the clinical setting. Nurs Prax N Z 1997;12:16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baraz S, Memarian R, Vanaki Z. The diversity of Iranian nursing students' clinical learning styles: a qualitative study. Nurse Educ Pract 2014;14:525–31. 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dornan T, Mann KV, Scherpbier AJ. Medical education: theory and practice. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: AMEE guide No. 63. Med Teach 2012;34:e102–15. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.650741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Levett-Jones T, Lathlean J, Higgins I, et al. . Staff-student relationships and their impact on nursing students' belongingness and learning. J Adv Nurs 2009;65:316–24. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04865.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Egan T, Jaye C. Communities of clinical practice: the social organization of clinical learning. Health 2009;13:107–25. 10.1177/1363459308097363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2009;14:595–621. 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bleakley A. Broadening conceptions of learning in medical education: the message from teamworking. Med Educ 2006;40:150–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02371.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development FT press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koivisto J-M, Niemi H, Multisilta J, et al. . Nursing students’ experiential learning processes using an online 3D simulation game. Educ Inf Technol 2017;22:383–98. 10.1007/s10639-015-9453-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chmil JV, Turk M, Adamson K, et al. . Effects of an experiential learning simulation design on clinical nursing judgment development. Nurse Educ 2015;40:228–32. 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McNelis AM, Ironside PM, Ebright PR, et al. . Learning nursing practice: a multisite, multimethod investigation of clinical education. J Nurs Regul 2014;4:30–5. 10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30115-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Newton JM, Henderson A, Jolly B, et al. . A contemporary examination of workplace learning culture: an ethnomethodology study. Nurse Educ Today 2015;35:91–6. 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Levett-Jones T, Lathlean J. The ascent to competence conceptual framework: an outcome of a study of belongingness. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:2870–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tynjälä P. Perspectives into learning at the workplace. Educational Research Review 2008;3:130–54. 10.1016/j.edurev.2007.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lawrence C, Mhlaba T, Stewart KA, et al. . The hidden curricula of medical education: a scoping review. Acad Med 2017;93:648–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Billett S. Critiquing workplace learning discourses: participation and continuity at work. Studies in the Education of Adults 2002;34:56–67. 10.1080/02660830.2002.11661461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wilkinson TJ. Kolb, integration and the messiness of workplace learning. Perspect Med Educ 2017;6:144–5. 10.1007/s40037-017-0344-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Coyle-Rogers P, Putman C. Using experiential learning: facilitating hands-on basic patient skills. J Nurs Educ 2006;45:142–3. 10.3928/01484834-20060401-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Price B. Key principles in assessing students’ practice-based learning. Nurs Stand 2012;26:49–55. 10.7748/ns2012.08.26.49.49.c9236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Levett-Jones T, Lathlean J. Belongingness: a prerequisite for nursing students' clinical learning. Nurse Educ Pract 2008;8:103–11. 10.1016/j.nepr.2007.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ruggiano N, Perry TE. Conducting secondary analysis of qualitative data: should we, can we, and how? Qual Soc Work 2019;18 10.1177/1473325017700701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029397supp001.pdf (63.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029397supp002.pdf (175.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029397supp003.pdf (173.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029397supp004.pdf (63.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029397supp005.pdf (141.9KB, pdf)