Abstract

Objectives

(1) To develop an understanding of how social capital may be conceptualised within the context of end-of-life care and how it can influence outcomes for people with dementia and their families with specific reference to the context and mechanisms that explain observed outcomes. (2) To produce guidance for healthcare systems and researchers to better structure and design a public health approach to end-of-life care for people with dementia.

Design

A realist review.

Data sources

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and grey literature.

Analysis

We conceptualised social capital as a complex intervention and, in order to understand how change is generated, used realist evaluation methods to create different configurations of context, mechanism and outcomes. We conducted an iterative search focusing on social capital, social networks and end-of-life care in dementia. All study designs and outcomes were screened and analysed to elicit explanations for a range of outcomes identified. Explanations were consolidated into an overarching programme theory that drew on substantive theory from the social sciences and a public health approach to palliative care.

Results

We identified 118 articles from 16 countries ranging from 1992 to 2018. A total of 40 context-mechanism-outcome configurations help explain how social capital may influence end-of-life care for people with dementia. Such influence was identified within five key areas. These included: (1) socially orientating a person with dementia following diagnosis; (2) transitions in the physical environment of care; (3) how the caregiving experience is viewed by those directly involved with it; (4) transition of a person with dementia into the fourth age; (5) the decision making processes underpinning such processes.

Conclusion

This review contributes to the dispassionate understanding of how complex systems such as community and social capital might be viewed as a tool to improve end-of-life care for people with dementia.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018084524.

Keywords: public health, social medicine, dementia, palliative care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A broad search to avoid missing major concepts.

Using a realist methodology allows us to focus on how contexts influence outcomes while identifying generative mechanisms.

The programme theory generated by this approach is therefore applicable to multiple interventions across different settings.

Social networks and social capital were often studied from a narrow perspective. This lack of empirical evidence meant that context-mechanism-outcome configurations could not fully explore specific functions of social networks or social capital.

Background

The dementias are a group of incurable, progressive illnesses with uncertain clinical trajectories. Globally, there are 35.6 million people living with dementia; figures are projected to triple by 2050.1 The need for care, especially at the end-of-life, is an international public health priority.2

Dementia changes social relationships.2 3 These relationships are fundamental to improving access to services and delivery of care. Relational changes are often portrayed negatively, meaning people affected by dementia may experience social isolation and prejudice.3 4

Attempts to address this have sought to shift the focus in care towards a person’s environment and the wider societal and organisational practices that shape it.5 6 How these concepts operate at the end-of-life, a time of heightened vulnerability and dependency, is of profound social and ethical importance yet relatively under-researched.

Fraught with uncertainty and unpredictability,7 8 the end-of-life with dementia is often depicted as ‘tragic’ and ‘untimely’.3 Unsurprisingly, residential care is often recommended. While a positive experience for some, this process can bring further distress in the form of guilt, family discord and loss of identity.9 10

Specialist palliative care professionals have expertise and experience working with such complexity.11–13 However, comparatively few people with dementia are referred.14 In the UK, hospices have limited capacity, while cuts to social service budgets mean professional home care is diminishing.15 16

With these issues in mind, a public health approach to end-of-life care has been proposed.17 18 The movement aims to pre-empt issues such as social isolation and stigma, by promoting supportive networks of community members. There is a growing evidence base for this approach, yet how it relates to the specific challenges of dementia is unknown.19 20

Close association between the disciplines of public health and palliative care represents a shift from more traditional public health measures towards embracing the social determinants of health and the influence of communities in the development of health. The actual articulation of such an approach focuses on ‘health promotion’ and emphasises notions such as promoting community engagement and adopting progressive asset-based and social capital-orientated interventions.

Social capital is therefore a potential target for public health interventions operating in the context of end-of-life care. Social capital is however a controversial concept. This stems from a diverse literature where definitions are multiple and dependent on the context and complexity associated with its operationalisation.21–23 It follows that social capital may take many forms and is not uniformly accessible, while its sources and consequences are pleural.22 Unifying themes focus on social capital being inherent in the structure of human relationships. To possess social capital, one must therefore be held in connection with others and an advantage is realised through these other people. Positive consequences may exist at the level of the individual and the community.22

In order to better understand such a broad concept, Nahapiet and Ghoshal24 have distinguished between structural, cognitive and relational social capital. Structural social capital refers to the presence of a network of access to people and resources. Cognitive social capital relates to subjective interpretations of shared understandings, while relational social capital includes feelings of trust shared by people within a social context (eg, a community).

A public health approach to palliative care seeks to operationalise social capital and its varying components. In a relationship that is new and constantly evolving, a range of positive outcomes have been described.19 25–27 However, at the level of the individual, the processes involved in acquiring social capital cut both ways. For example, social ties may provide access to resource, but can also restrict individual freedoms and bar outsiders from access.22 For this reason, social capital in relation to health must be studied in all its complexity rather than as an example of value.

Previous systematic reviews have looked at factors including caregiver and family characteristics that influence transitions in care and the various interventions to support or delay this process.28 Less attention has been paid to exploring the underlying causal processes that occur during this process and how transitions in care fit into the broader picture of end-of-life care.

Evaluation questions and objectives

Research questions

What are the mechanisms by which social capital is believed to impact on relevant outcomes for people with dementia at the end-of-life?

What are the important contexts which determine whether different mechanisms produce intended outcomes?

In what circumstances and for who is social capital an effective intervention?

Objectives

To develop theory around the interaction between social capital, end-of-life care and dementia.

To develop an understanding of how social capital may be defined and conceptualised within the context of end-of-life care and how it can influence outcomes for people with dementia and their families with specific reference to the context and mechanisms that explain observed outcomes.

To produce guidance for healthcare systems and researchers to better structure and design a public health approach to end-of-life care for people with dementia.

Methods

To address the complexity presented by the research questions, we drew on critical realist philosophy.29 This distinguishes between three aspects of the world that co-exist yet remain distinct. The ‘empirical’, what we actually experience; the ‘actual’, events that occur and the ‘real’, generative mechanisms that are often hidden. This distinction implies that any singular event can be perceived differently when influenced by different mechanisms or that the same mechanism may lead to a different event depending on the context. Critical realist approaches follow an interpretative, theory-driven process of synthesising evidence from heterogeneous data.30 The main strength is to produce findings that explain how and why social practices have the potential to cause change. Findings are described in terms of context-mechanism-outcome configurations (CMOCs). We conceptualised social capital as a complex intervention. This was done in order to understand the challenges faced by a growing trend for public health interventions that seek to build social capital as a means of improving end-of-life care. Causation was not to be understood in relation to social capital per se, that is, to see if social capital ‘works’ or ‘doesn’t work’. Instead, causation is thought to be generative through the release of ‘mechanisms’ or underlying causal powers of individuals and communities.30

To account for the pan-disciplinary interest in social capital, our search was not restricted to one definition. Through immersion in the literature, we chose to focus on how the nature and existence of human relationships, within social structures such as healthcare, community and ‘the home’, were introduced or excluded from an evolving network of care, and how this appeared to influence outcomes at a series of key decision points. Instead of focusing on barriers or facilitators to the development of social capital, we focused on what happens in the presence of challenges faced by people with dementia.

The review is registered on PROSPERO and ran for 17 months (October 2017 to February 2019). It is reported according to the RAMASES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards) publication standards.31 The review followed Pawson’s five iterative stages as described below.32 With reference to Papoutsi et al,33 and in order to develop a more accessible narrative beyond CMOCs, we sought to engage with substantive theory in what became the sixth step.

Locating existing theories and programme theory development

Prior to formal literature searching, JMS devised an initial programme theory to act as a reference point. This was based on prior knowledge and an initial scoping search. The scoping search used key terms and recognised authors in the field across MEDLINE/PubMed and Google. Additional literature was accessed through citation tracking and eliciting key studies from experts.34 Relevant theories such as Bartlett and O’Connor’s model of ‘social citizenship’,5 Kitwood’s ideas on personhood6 35 36 and Kellehear’s ‘compassionate cities’ model17 37 were reviewed in conjunction with established literature on social capital.21–24

Findings were combined with the experiential, professional and content knowledge of the research team (JMS—clinical research fellow in palliative care, LS—consultant in palliative care and senior clinical lecturer in new public health approaches, NK—senior research fellow in dementia, PS—clinical academic in palliative care and ELS—clinical reader in old age psychiatry and expert in dementia and end-of-life care). The resulting programme theory acted as a guide for refining assumptions against data from the main search. Group consultations continued during data analysis in order to refine the programme theory.

Searching for evidence

Two distinct formal literature searches were conducted through the databases MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL. For the main search, terms included: dementia OR Alzheimer’s disease OR multiinfarct dementia OR vascular dementia; social capital OR social network OR social support OR community development OR community participation OR social integration; palliative therapy OR terminal care OR palliative care OR end-of-life OR death OR dying. Full terms are available in the online supplementary file. Terms were piloted and refined to increase sensitivity. Grey literature was searched using Google and the data base OpenGrey. References within included documents were screened for relevance.

bmjopen-2019-030703supp001.pdf (512.4KB, pdf)

The search was run in December 2017 and repeated in October 2018 to capture newly published articles. Databases were searched from inception. We included all studies on dementia relating to any aspect of social capital identified in step (i). All study designs were included across all settings. We excluded studies focusing on old age and frailty.

Following analysis of the literature from the main search, and discussions within the research team, an additional search was undertaken to focus the review on emerging themes. This looked at the influence of social networks and social capital on ‘transitions in care’. This was intended to provide more detail to the contextual influences identified as important from the main search. There were no prespecified exclusion criteria; all study types and settings were included.

Results from both searches were exported to EndNote X8 referencing software. Duplicates were removed using automated and manual checking. All citations were reviewed by JMS against the inclusion criteria and a 10% random subsample reviewed by NK.

Selecting articles

All titles and abstracts were screened by JMS and included if they were judged to contain data relevant to the programme theory. Studies did not need to contain all components of the programme theory so as not to exclude important concepts. Only studies in English were included. The purpose of selecting and appraising full text articles was not to create an exhaustive set of studies, but rather to reach conceptual saturation in which sufficient evidence could be collated to meet the stated aims.38 At the point of inclusion, based on relevance, judgements on the rigour and trustworthiness of each source were addressed (see online supplementary file for details). There was significant overlap between relevance and rigour as data were only selected to modify the programme (ie, relevant to the research question) theory when adherent to the chosen methodology (ie, rigorously conducted).

Extracting and organising data

Study characteristics were tabulated in Microsoft Word. Sections of text, including participant quotes, author interpretations and conclusions, relevant to the programme theory were highlighted in PDF format. Broad themes relating to the highlighted text were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet. Repeating themes were developed into codes inductively. Codes were also developed deductively (originating from the initial programme theory). The codes were refined based on emerging concepts throughout the analysis period. Codes were developed by asking if the identified information was referring to context, mechanism or outcome. On coding, the original text would be revisited and the highlighted text reviewed before making a decision. A sample 10% of the coded papers was independently reviewed by LS for consistency.

Synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions

Highlighted excerpts, which had then been coded, were transferred into a word document. This was printed and annotated as themes developed iteratively. As data came to represent context, mechanism or outcome, it was labelled as such and transferred into PowerPoint. This was to provide a more flexible work space to construct CMOCs. To develop an overall programme theory, we moved iteratively between the analysis of particular examples, discussion within the research team, refinement of programme theory and further iterative searching from within the existing data set.

A realist logic of analysis was applied to synthesise data. This process involves the constant movement from data to theory to refine explanations for observed patterns. Explanations were built at a level of abstraction that would cover a range of observed behaviours in different settings. In order to achieve this, inferences were made about which mechanism may be triggered in specific contexts. This was necessary as mechanisms were often not explicitly stated within the literature. The data set was then reviewed to find data to corroborate, refute or refine developing CMOCs.

Relationships between context, mechanism and outcomes were sought from within the same article to which relevant data appeared, but also across sources. Thus, it was not uncommon for a mechanism inferred from one article to explain the way contexts influence outcomes in a different article.

Writing and engaging with substantive theory

The process of writing helped develop the final programme theory. Narrative is used to explain the data which in turn enabled us to fine-tune our interpretations of meaning and relevance. Formal theory identified during the search was used to assist in programme theory refinement by substantiating the inferences made about contexts, mechanism and outcomes, thus enhancing plausibility and coherence.5 17 39–41

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in this research.

Results

Search results

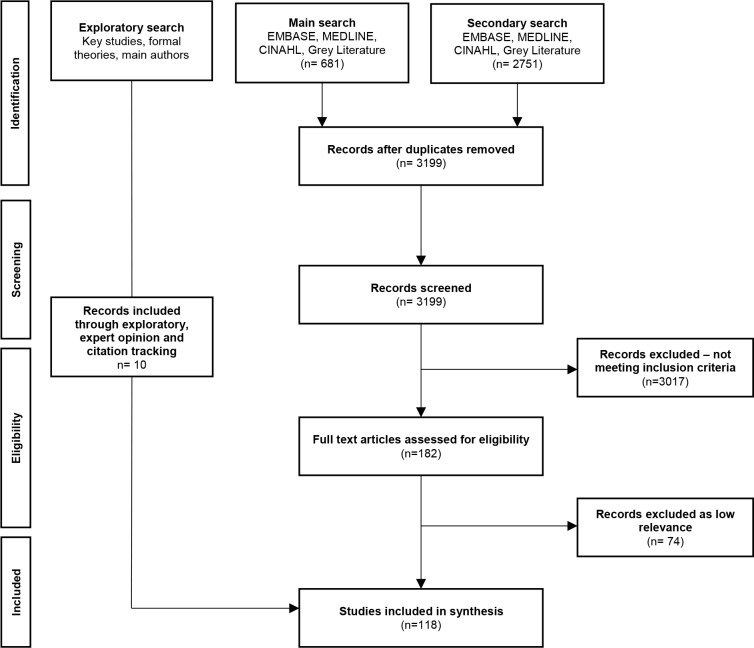

A total of 3199 titles and abstracts were screened leading to a full text review of 182 articles. Seventy-four articles were excluded after assessment for relevance and rigour and 10 added via citation analysis and expert opinion leaving a total of 118 included references (figure 1). Of these, 55 used qualitative methods, 28 used quantitative methods and 5 used mixed methods. There were 11 reviews and 19 references that included book chapters, editorials or commentaries (full characteristics available in the online supplementary file).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram.

Programme theory and CMOCs

The following sections provide a narrative overview of the programme theory that explains how social capital may influence end-of-life care for people with dementia. The impact of social capital is evaluated under five categories: (1) socially orientating a person with dementia following diagnosis; (2) the process of decision making; (3) transitions in the physical environment of care; (4) how the caregiving experience is viewed by those directly involved with it and (5) transition of a person with dementia into the fourth age. These five categories emerged following analysis and clustering of the data from the literature. They represent areas in which social capital was observed to have significant influence and which may therefore be targeted for further study and the development of public health interventions that are specifically seeking to harness the influence of social capital. Due to space constraints, only a selection of CMOCs are presented in narrative form. Definitions of key terms can be found in table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of key terms as used in this review

| Term | Definition |

| Context | Context was viewed as the backdrop to a person’s progressive journey following a diagnosis of dementia. More specifically, they were settings, structures, environments, public discourse, conditions, circumstances or specific universally experienced events (such as transitions in the care environment) where social relationships could be seen to directly influence outcomes either positively or negatively. Contexts triggered behavioural and emotional responses (ie, mechanisms) for both the individual with dementia and those people within their immediate social network (eg, family and friends). |

| Mechanisms | The way in which people with dementia and those involved in their care (both professional and lay) respond to and reason about challenges presented by the progression of dementia. Mechanisms were triggered in specific contexts and led to changes in behaviour and decision making. |

| Outcome | Observed points from the literature that resulted from an interaction between specific mechanism and contexts. These points represent outcomes that were observed to be directly influenced by social capital and as such are potential targets for interventions that seek to harness the role of social capital in end-of-life care. |

| Agency | Is the capacity of individuals to act independently, to make their own choice and thus bear influence on their surroundings. |

| Agentic influence | This is the influence exerted by the agent in question. |

| Cognitive social capital | Subjective interpretations of shared understandings held by a close network or group of people. |

| Structural social capital | The presence of a network of access to people and resources both professional and lay. |

| Relational social capital | Feelings of trust shared by people within a social context. |

Socially orientating a person with dementia following diagnosis

We found that the impact of structural social capital, that is, the properties of a social system and its networks of relations,24 was pronounced in socially orientating a person following diagnosis. Structural social capital was therefore viewed as a naturally occurring intervention that influenced how a person with dementia orientates themselves within the world. This influence of structural social capital is explained as a function of generative mechanisms in combination with specific and recurring contexts as seen within the data.

To explain this, we draw on the sociological concept of liminality; a state of ‘inbetweenness and ambiguity’ that often occurs following a serious diagnosis.42 43 Birt et al 44 describe movement to a ‘post-liminal’ state in dementia, a state characterised by interdependency that allows for the expression of a new identity that can exert influence on the surrounding environment.44 This process reflected themes developed from key sources5 6 and the data set at large.45–51

For example, we found evidence that where cohesive support networks surround a person with dementia,52 53 people are able to live with a sense of purpose52 54 while members of the network are able to advocate for their perceived wishes through the exchange of knowledge with other community members.55–61 Cohesive support networks developed knowledge or ‘expertise’ relating to the person with dementia.48 62 This was accumulated through the provision of care and equated to ‘longitudinal monitoring’.63–65 Knowledge was then conveyed through narrative66 67 to help develop a person’s role as an active citizen.5 44 52–54 67

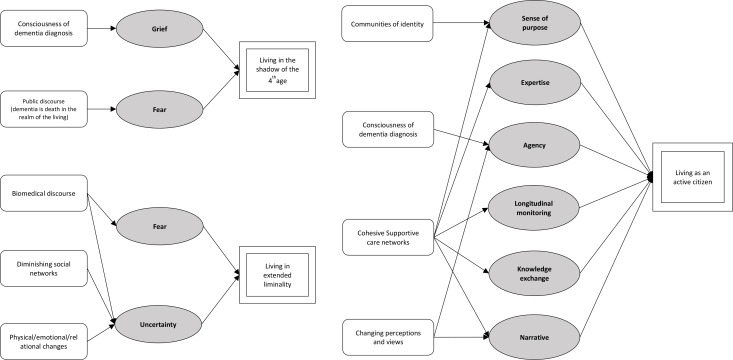

We also found evidence that with progression of dementia, social networks dwindle.52 68–70 The decline in social connections gave rise to people living in a period of extended liminality,44 46 71 72 where uncertainty as to what the future may hold was the generative mechanism.47–51 59 Periods of extended liminality were also noted to be a product of the pubic and biomedically fuelled discourse that depicts dementia as ‘death in the realm of the living’.3 71 This was also noted in situations where people, conscious of their diagnosis, experienced uncertainty as to how their views would be interpreted, again leading to a state of extended liminality.44 47–49 72 73 Figure 2 shows a complete set of CMOCs for this section. A summary overview of this section is shown in box 1. Detailed examples of CMOCs with supporting evidence are shown in table 2. A full list is available in the online supplementary file.

Figure 2.

Context-mechanism-outcome configuration for ‘transition to a post-liminal state’. Rectangular node=context; grey node=mechanism; double border node=outcome.

Box 1. Summary of findings.

Context

People enter a state of ‘inbetweenness’ or liminality following a diagnosis of dementia.

Influence of social capital as an intervention

Social capital, in particular structural social capital, influenced the coming to terms with a diagnosis and set the path moving forward.

Context-specific outcomes

Depending on the context, which would trigger specific mechanisms, people with dementia were found to move into one of three states; (1) living as an active citizen, (2) living in a state of extended liminality and (3) living in the shadow of the fourth age.

Table 2.

Examples of key CMO configurations with supporting evidence for ‘transition to a post-liminal state’

| Context (C)-Mechanism (M)-Outcome (O) | Example of supporting evidence from the literature |

| CMO: In the context of dementia being perceived as ‘death in the realm of the living’ (C), people with dementia and their wider social network experience fear and trepidation (M) that moves people into a state confined by the shadow of the ‘fourth age’ (O) |

Death in the realm of the living

: ‘Dementia confronts because it seems to bring death into life, implicitly questioning what life, relationship, and death are about.’ 3

Fear ‘people with dementia are often thought of as tragic, robbed of life, and having lost their personhood.’ 3 The fourth age ‘It is when people are no longer ‘getting by’, when they are seen as not managing the daily round, when they become third persons in others’ age-based discourse, within others’ rules, that they become subjects of a fourth age’ 102 |

| CMO: In communities of identity (C), people with dementia have a sense of purpose (M), which allows them to grow and maintain a role as an active citizen (O) | Communities of identity ‘This centre provides day care for those living with dementia but instead of playing games or receiving passive entertainment the main program is about the design and production of the mid-day meal. Seniors with dementia are asked to jointly design the meal, then to go out shopping together to buy the ingredients, and then return to help prepare the meals. Shopkeepers are briefed on the program and willingly participate in the program, learning and experiencing the complexities of communicating with seniors with dementia and also Compassionate communities gaining insight into the complexities of their care while sharing this in a small way.’ 54 |

| CMO: As dementia progresses, a person may change their perceptions and views on various issues (including death) (C), they maintain their role as an active citizen (O) by conveying these views through their agentic influence (M) |

Changing perceptions

: ‘Relatives and staff need to be aware that the person’s attitude to death may evolve during their dementia. When a comparison was made between participants’ attitudes to death and those ascribed to them by their family carers, for some people they appeared to have changed.’ 66

‘(Husband) had a bit of a health crisis about 12 months ago…when he came out of this acute crisis, he said to me he was afraid people that people would turn off the switch. So there was a complete change of his limited understanding…(now) I don't know whether I'm actually fulfilling his wishes.’ 53 |

The full list is available in the online supplementary file.

Decision making processes

The decision making process acted as a vehicle to move between outcomes and was heavily influenced by ‘cognitive social capital’. Cognitive social capital relates to the shared representations and interpretations of meaning held by involved parties.24

Cognitive social capital was viewed as an intervention that became influential at times of decision making. Its influence is explained as a function of generative mechanisms in combination with specific and recurring contexts as seen within the data.

This process was particularly evident in the context of advance care planning.53 67 74–76 Here, decision making processes are influenced by a family’s power as a surrogate decision maker. Mechanisms included the maintenance of a historic identity,75 77 growth of a new identity,66 74 78 discrimination against a person with reduced agency,51 74 76 compassion towards a person affected by dementia and ‘knowledge exchange’ between caregivers and professionals.18 60 66 68 74 75 77 78

Decision making was facilitated by ‘case based theory’ rather than ‘principal theory’,77 that is, when faced with a ‘what’s best scenario’, families use factors important to the individual as opposed to humanity in general. Here, narrative relating to the person with dementia is of prime importance. Depending on how the caring network developed this narrative, that is, through mechanisms such as identity growth, knowledge exchange, paternalism or identity maintenance, the outcome would vary.40 48 59 60 67 77 79 80

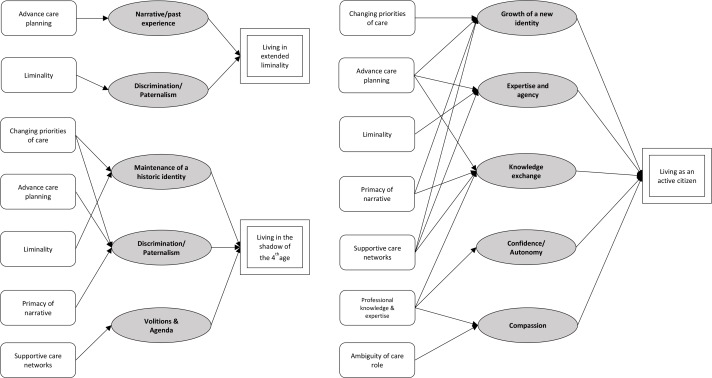

The influence of supportive care networks, both professional and lay, was not uniformly positive. Decision making was found to be subject to the independent ‘volitions and agendas’ of a care network or the paternalistic actions of professionals. These mechanisms lead to discrimination against the person with dementia in certain contexts.51 56 58 70 71 74 76 77 Box 2 provides a summary of findings for this section. Figure 3 shows a complete set of CMOCs with detailed examples described in table 3.

Box 2. Summary of findings.

Context

As dementia progresses, decisions relating to all aspects of life present challenges that come thick and fast.

Influence of social capital as an intervention

Shared representations and interpretations of meaning held by social networks influenced decision making.

Context-specific outcomes

(1) Living in extended ambiguity; (2) living as an active citizen; (3) living in the shadow of the fourth age.

Figure 3.

Context-mechanism-outcome configuration for decision making from the perspective of a person with dementia. Rectangular node=context; grey node=mechanism; double border node=outcome.

Table 3.

Examples of key CMO configurations for the ‘decision making process’ with supporting evidence

| Context (C)-Mechanism (M)-Outcome(O) | Example of supporting evidence from the literature |

| CMO: Families used ‘case based theory’ rather than ‘principal theory’ when making decisions. Here, narrative relating to the person with dementia is of prime importance (C). A more rewarding care experience occurs (O) with the use of agency (M), identity growth (M) and knowledge exchange (M). |

Primacy of narrative: ‘The ethical approach implicit in these families’ descriptions are consistent with a case-based theory, rather than a principle theory. When these family decision-makers utilized an abstract concept such as human dignity, they did so in a limited manner by discussing the factors that were important for the dignity of their relative, rather than for human dignity in general. They did not invoke patterns or principles from beyond their own experience.’77

Identity growth: ‘She had always been shy and didn’t want to entertain people. Yet, when her inhibitions were lost because of the Alzheimer’s, she would get excited when people visited. She enjoyed the Bible study in our home every Friday evening. One day I was late getting her up from a nap, and students were already arriving. I woke her, asking if she wanted to see the students coming. She jumped out of bed, replying, ‘I think they’ll want to see me.’ Indeed, she did have a special relationship with the students.’ 60 Knowledge exchange: ‘Inclusion was facilitated in other ways such as knowing the preferences of the person through previous interviews with them and their family, or by asking family members about what those preferences might be, building a biographical understanding of the person and being informed by that.’ 79 Rewarding experience: ‘I think whatever you do, you’ve got to do it with a relatively good grace. If you feel that you’ve been pushed into it, or you’re obliged to do it, then I think it won’t work.’ 59 |

| CMO: Where there is interaction with professional care services (C), the decision making process can be facilitated to increase a person’s role as an active citizen (O). Mechanisms include compassion, knowledge exchange and confidence/autonomy (M). |

Knowledge exchange: ‘I was able to tell the doctor what was going on with my mom. And he was grateful for the knowledge. He told me what to expect and when to call the clinic. I felt better prepared after that.’ 48

Confidence/autonomy : ‘So they’re sort of pre-empting what they know is going to happen. [Yes] See I don’t necessarily know that’s gonna happen so they’re kind of giving me that information. ‘Look, you know, you’re gonna be heading down this road soon so you may wanna do this, this and this.’ So it’s helping me to future plan [Yep] which I find very helpful.’80 |

| CMO: In a state of liminality characterised by indecision and uncertainty (C), medical paternalism and authority (M) can provide some direction allowing the decision making process to proceed with more fluidity but maintain a state of liminality and loss of control (O) |

Paternalism/authority: ‘So long as you say… ‘doctor’ in the sentence… she will go along with that, she will listen to that authority so that’s been good actually.’ (daughter) 59

My mother was asked what she thought and said, ‘Whatever the doctor thinks is best.’ 46 ‘The second strongest influence affecting the decisions of both groups…was the advice of the physician…’105 ‘You accept it because it’s easy…I think to meself [sic] ‘they are only trying to help you so let them do what they think is best’.’ 72 |

| CMO: Where relationships with a caring network become strained (C), a sense of guilt (M), failure (M) and uncertainty (M) in addition to the paternalistic actions of professional care networks (M) can cause the caregiving experience to become overwhelming (O) |

Strained relationships

: ‘It’s a different thing when Mum (person with dementia) was living with us. He (participant’s husband) just didn’t handle things, and I was between the devil and the deep. I didn’t want to -Mum needed the care. I felt that she wasn’t ready to go into a nursing home at that stage, and yes, it was awful. It affected me very badly’ 71

Guilt : ‘The doctor said my mom could not live alone. You know, I love my mom, but she could not come and live with us. It would have disrupted my whole family. I know it is terrible to call your mother a disruption. What a guilt trip.’81 Paternalism : ‘…healthcare professionals unfamiliar with the family and the resident’s individual wishes were also noted to cause unnecessary anxiety, again resulting in reluctance of further contact.’ 70 Uncertainty : ‘…thus, critical issues of personhood, identity, agency, and control were embedded in our moms’ experiences and reflected in our experiences as families as we struggled to ‘do what was right.’ 49 Overwhelming : ‘I had no one to look after mum, so I couldn’t go to work, and I do believe that that impacted and I do believe that that’s one of the reasons that they fired me. Because I couldn’t attend work because I had to look after mum’ 62 |

| CMO: Where powerful structures of care become involved (C), feelings of failure (M) and a loss of autonomy (or paternalism from healthcare professionals) (M) can lead to a care experience that feels overwhelming (O) |

Professionalised care: ‘Dementia starkly reveals the Cartesian biomedical model’s incomplete understanding of ‘health,’ through its inability, even unwillingness, to develop effective (non-biomedical) interventions to address a range of experiences of disease in their social, relational context.’3

‘…carers experience in receiving formal services is inherently ambiguous, for while formal services are providing support to family carers, they can also be undermining their sense of identity and control over their circumstances…’62 Loss of control/autonomy in the care role: ‘Oh God no, they did everything, all I had to do was go and visit and feed her. Didn’t even have to feed her but I liked to.’ 57 |

The full list is available in the online supplementary file.

When considering the decision making process from the perspective of the family or main carers, we found that the same contexts and mechanism were in operation. The CMO configurations are configured to outcomes relevant to the care network in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Context-mechanism-outcome configuration for decision making from the perspective of the caregiver. Rectangular node=context; grey node=mechanism; double border node=outcome.

Transitions in care

Much of the data focused on transitions for people into hospital or long-term care as a primary outcome.55 81–84 To understand the influence of social capital as an intervention in this setting, we drew on Bourdieu’s work that implies social capital is deeply reliant on the context of a particular social space.21

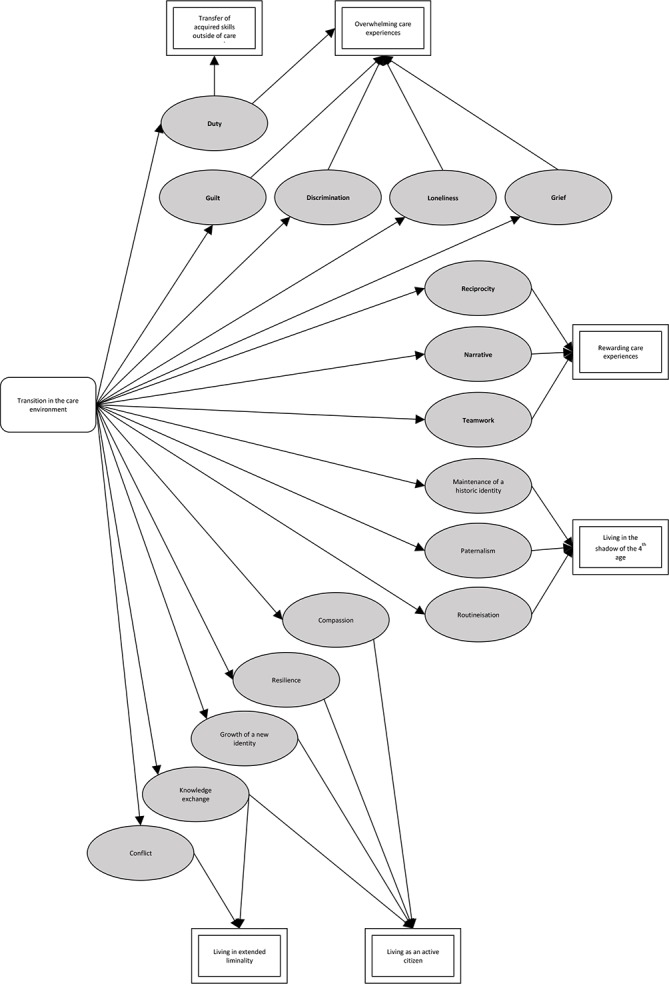

The data revealed that transitions in the care environment occur as a function of progressive illness, often as a necessity rather than something to be prevented.85 86 We found that transitions in the care environment were therefore operating as context as opposed to an outcome. The full CMO configurations are available in figure 5.

Figure 5.

Context-mechanism-outcome configuration for ‘transitions in the care environment’. Rectangular node=context; grey node=mechanism; double border node=outcome.

Transitions occurred within a person’s home as professionals entered and changed the physical space. They also occurred when a person moved out of the home into an alternate care environment.87–89 The process of physical transition acted as an interface on which supportive networks of care would convene along with the person with dementia and professional care services. The outcomes of this process contribute to the post-liminal states previously described but also help define the care experience for those within the main care network. Rather than being mutually exclusive endpoints, people would move between outcomes based on the contexts and mechanism described. Box 3 gives a summary of the findings from this section and box 4 gives detailed examples of CMOCs with supporting evidence.

Box 3. Summary of findings.

Context

Transitions occur as a function of progressive illness. Transitions are often a necessity rather than something to be prevented.

Influence of social capital as an intervention

Social capital bore great influence not on whether the transition occurred or not but more how the process unfolded and was perceived by the person with dementia and their wider social network.

Context-specific outcomes

(1) Overwhelming care experience; (2) rewarding care experience; (3) living in shadow of fourth age; (4) living as an active citizen; (5) living in extended ambiguity.

Box 4. CMO configurations with supporting evidence for ‘transitions in the care environment’.

Context (C)-Mechanism (M)-Outcome(O)

CMO: As dementia progresses and manifests as changes in behaviour and social relationships, transitions occur to the care environment, these might involve the person moving or objects moving into what was previously the home environment. Either way, the space as it previously was, transitions to something new (a hybrid space in the home) or an entirely new space in some form of institutional care (nursing home, hospital, sheltered accommodation). These transitions (C) have outcomes relating to the individual: living in extended liminality; living as an active citizen; living in the shadow of the fourth age, and to the individuals care network; rewarding care experiences; overwhelming care experiences and transfer of acquired skills outside of care network (O). Mechanisms identified include duty, paternalism, compassion, routinisation, reciprocity, narrative, resilience, discrimination, teamwork, identity growth, identity maintenance, grief, loneliness and knowledge exchange (M).

Example of supporting evidence from the literature

Transitions: ‘I tend to think that people with dementia do want familiar; it’s the change that is difficult to cope with and the familiar things are personal things, if we’re talking about residential care, to bring in personal things of theirs, whether it was his music, I know my husband did a lot of photography as a hobby… and he had the photographs there… and when he did go into respite, we took the same pictures, I think, that was important to him.’88

Transitions in the home: ‘Although all the care recipients and their family caregivers indicated a strong preference for home care over institutional care, their experiences and practices within their homes were disrupted and reconfigured by the insertion of logics emanating from the healthcare field’87

Duty: ‘Another difference was in the sense of obligation for family members to provide care for their next of kin through the course of the disease…’97

Guilt: ‘I visit here many times, but every time I am so ashamed. This place is like a dumpster where you throw away things, a place for well-off daughters’ in-law to throw away their parents-in-law. I felt so guilty in front of the nursing assistants to be a child of one of these elderly people. I don’t even dress nice when I come here because I’m afraid of what people will say of me since I’ve brought my parents over here.’106

Reciprocity: ‘Mom also taught me more about love. I learned to express my love. Because I knew she would easily forget, I would remind her many times a day that I loved her. Each time I did, she would light up with a smile. It brought me much joy to see her receive my love. Often when I was helping her, she would kiss me on the arm, whisper ‘I love you,’ or say ‘Thank you.’… I realized the more I said, ‘I love you,’ the more love grew’ 60

Resilience: ‘It is surprising that behavioural disturbances are one of the major reasons for admission in RUD (rehabilitation unit for dementia), but they are not risk factors for institutionalization after discharge. The process mediating the association between BPSD (behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia) and placement may be the ability of the caregiver to tolerate such behaviours and not BPSD by themselves.’ 107

Growth and liminality: ‘…participants show an orientation to the present and the future that contains growth on the one side and vulnerability on the other. Growth concerns personal growth and developing new ways in which to organize their lives. Aspects of vulnerability include declining health, possible dependence, coping with growing older, and being concerned with finitude.’ 45

Grief: ‘This transition (to long term care) can also highlight the sadness that marks the end of a long-standing relationship.’ 108

‘I had to keep reminding myself that the disease took away the dad I once knew’ 109

Loneliness: ‘I don’t actually call them that much, but just knowing they are there is a tremendous source of help…’9

Knowledge exchange: ‘A lack of communication or information sharing appeared to be a key reason why older adults and caregivers felt ignored, forgotten or unimportant’83

Conflict: ‘You tell him that I absolutely refuse for them to do anything with my father. Unless a doctor calls and tells me that I have to do something, it’s gonna stay the way it is now’. And I said, ‘If he doesn’t like it, and he thinks he’s gonna cause you trouble, you tell him that I’m gonna go get me a lawyer, and I’m gonna call Channel 5…’.’77

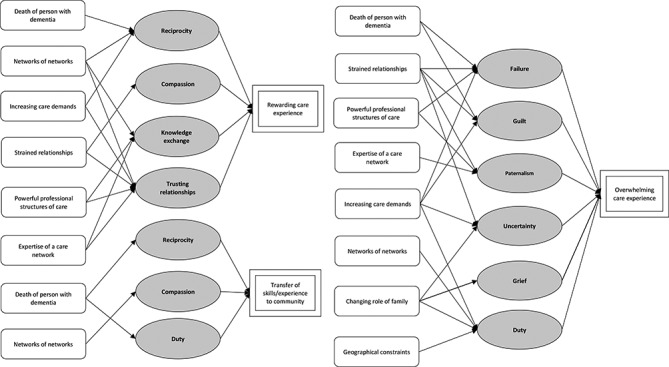

The caregivers experience

The caregivers experience brought up themes relating to the concept of relational social capital, that is, aspects such as trust, trustworthiness and norms.24 Here, relational social capital is conceptualised as the intervention that works to define a caregiver’s experience through combinations of observed contexts and mechanisms.

Much of the empirical data focused on the negativity associated with care.10 47 48 58 62 63 90–92 However, we found evidence of the positive aspects of caregiving, which was noted as an important outcome. For example, where relationships with a caring network become strained,10 62 71 93 the exchange of knowledge and trusting relationships56 57 70 90 generated rewarding aspects to the care experience.5 50 94–96

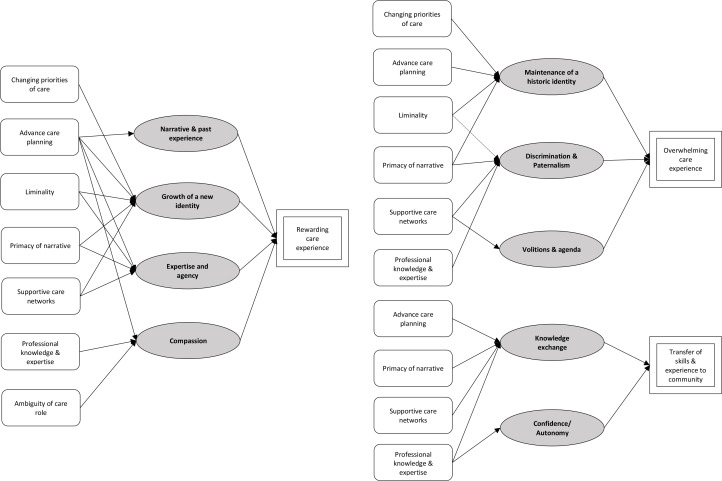

In certain conditions, there was also evidence of the skills acquired through the caregiving process being transferred to wider community networks. For example, when a person with dementia died, the void in reciprocity experienced during caregiving, and a sense of duty, can drive people to transfer their skills to the community.54 60 80 86 97–101 The full list of mechanisms and associated contexts are shown in figure 6. A summary of this section is given in box 5 and selected CMO configurations described in table 4.

Figure 6.

Context-mechanism-outcome configuration for the ‘caregiver’s experience’. Rectangular node=context; grey node=mechanism; double border node=outcome.

Box 5. Summary of findings.

Context

Positive and negative aspects to caregiving are reported in the literature.

Influence of social capital as an intervention

Social capital shaped how the caregiving experience was viewed however aspects are under-researched.

Context-specific outcomes

(1) Rewarding care experience; (2) overwhelming care experience; (3) transferring of skills to the community.

Table 4.

CMO configurations with supporting evidence for the ‘caregiver’s experience’

| Context (C)-Mechanism (M)-Outcome(O) | Example of supporting evidence from the literature |

| CMO: When a person with dementia dies (C), the void in reciprocity experienced during the care giving relationship (M) and a sense of duty (M) can drive members of the caring network to transfer their skills to the community (O) |

Reciprocity: ‘…yet many aspects of my experience were positive. My father and I had conversations about his memories of his older relatives that I doubt we would have had otherwise. Sharing the ups and downs of caregiving with my sister also brought us closer together. It was the first time that we had discussed our values about caregiving (despite having witnessed our mother’s experience), money, and ultimately, end-of-life care…’ 96

Duty: ‘As a son, taking care of my parents is my responsibility. Sometimes, my sisters come back home to care for my father, but they have already married out [of the family). They are guests. It's not their responsibility. I appreciate their assistance though. However, my brother and I have the ultimate responsibility to take care of our parents.’ 110 ‘I just took it as that was part of my life goal, to take care of them… It’s stressful, but sometimes it’s rewarding.’ 95 ‘…if you have to have something bad happen to you, to be able to turn it into something positive that helps other people, it’s a good thing to do… I like to say when I go out to speak that I have a lot of passions, that I have passions for gardening and for hiking and for quilting… I chose those passions, and then I have a passion that chose me, and that’s what Alzheimer’s is… I think there are ways to give of yourself that sort of replace that caregiving role… working with the Alzheimer’s Association and that work that I do- I think that’s filled the void.’ 95 |

| CMO: Where relationships with a caring network become strained (C), the exchange of knowledge (M) and trusting relationships (M) generated positivity and rewarding aspects to the care experience (O) |

Strain: ‘Initially life seemed unbearable. My mother was incontinent, hallucinating, and disoriented. At one point she stayed awake for 40 hours seeing people, places, and things that weren’t there. We were exhausted. But in time, she showed signs of improvement.’ Knowledge exchange: ‘I think just their reassurance…there is nothing physically they can do…they just reassure you…. That you are doing the right thing, more than anything, because sometimes you do doubt yourself’ 61 Trust : ‘External support resources from the community or charitable organisations were a key feature for some. Specifically, reliance on neighbours or being members of a close community gave reassurance of their relative’s safety when they were not present…’ 70 Rewarding aspects to care: ‘When my mother died from a fall, I reflected on the satisfaction and peace I had not anticipated I would feel. I knew what it was to ‘give back’ to my mother. It seems incredible that caregiving can be so satisfying. I look into her bedroom now and I can feel her presence…and I am thankful for the final gift she gave me.’ 94 |

| CMO: Where relationships with a caring network become strained (C), a sense of guilt (M), failure (M) and uncertainty (M) in addition to the paternalistic actions of professional care networks (M) can cause the caregiving experience to become overwhelming (O) |

Strained relationships: ‘It’s a different thing when Mum (person with dementia) was living with us. He (participant’s husband) just didn’t handle things, and I was between the devil and the deep. I didn’t want to [move to a care home)-Mum needed the care. I felt that she wasn’t ready to go into a nursing home at that stage, and yes, it was awful. It affected me very badly’ 71

Guilt: ‘The doctor said my mom could not live alone. You know, I love my mom, but she could not come and live with us. It would have disrupted my whole family. I know it is terrible to call your mother a disruption. What a guilt trip.’ 81 Paternalism: ‘…healthcare professionals unfamiliar with the family and the resident’s individual wishes were also noted to cause unnecessary anxiety, again resulting in reluctance of further contact.’ 70 Uncertainty: ‘…thus, critical issues of personhood, identity, agency, and control were embedded in our moms’ experiences and reflected in our experiences as families as we struggled to ‘do what was right.’ 49 Overwhelming: ‘I had no one to look after mum, so I couldn’t go to work, and I do believe that that impacted and I do believe that that’s one of the reasons that they fired me. Because I couldn’t attend work because I had to look after mum’ 62 |

| CMO: Where powerful structures of care become involved (C), feelings of failure (M) and a loss of autonomy (or paternalism from healthcare professionals) (M) can lead to a care experience that feels overwhelming (O) | ‘Hospitalisation of the person with dementia was also described as a challenging time. Carers may have taken responsibility for all of the caring, believed they knew the person and their needs most intimately and taken responsibility for decision-making; however, when the person with dementia is admitted to hospital, the carer is usually no longer primarily responsible for these things and he/she can experience an acute loss of control. In addition, vulnerable family caregivers can feel disempowered by the health care system, especially when they are not recognised as the expert in the care of their relative and not appropriately included in decision-making’ 71 |

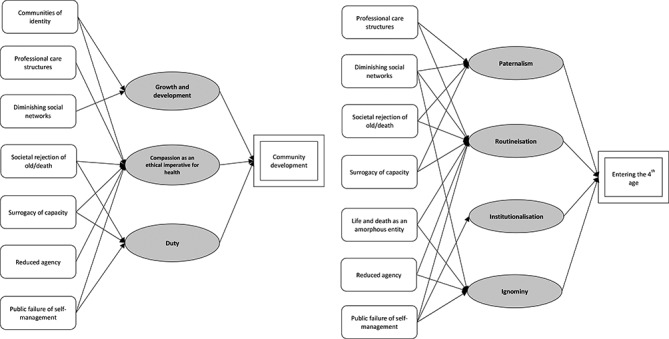

Dementia progression and the fourth age

The final aspect of our programme theory investigates the role of social capital in the context of entry into a state of complete dependency known as the ‘fourth age’.102 At this point, a person’s ability to influence their surroundings is reduced, social networks have diminished and preformed close contacts hold a narrative that is referred to during decision making.52 68–70 80 100 101 Where social networks have diminished, the routinisation of paternalistic care and the ignominy of this can lead to people entering the fourth age,58 69 100 102 103 see figure 7 for complete CMOC, box 6 for a summary and table 5 for evidenced examples.

Figure 7.

Context-mechanism-outcome configuration for dementia progression and transitioning to the fourth age. Rectangular node=context; grey node=mechanism; double border node=outcome.

Box 6. Summary of findings.

Context

A person’s ability to influence their surroundings is markedly reduced and social networks have diminished.

Influence of social capital as an intervention

Can impact on how caregiving skills are transferred to the community.

Context-specific outcomes

(1) Rewarding care experience; (2) overwhelming care experience; (3) transferring of skills to the community.

Table 5.

CMO configurations with supporting evidence for transitioning to the fourth age

| Context (C)-Mechanism (M)-Outcome(O) | Example of supporting evidence from the literature |

| CMO: Where there is a public failure of self-management (C), a person enters the fourth age (O) via mechanisms including institutionalisation (M), ignominy (M) routinisation of care (M). |

Public failure of self-management: reflections from a paid carer, ‘Not being able to take responsibility, not knowing that things (food) are mouldy or at the expiration date. Not knowing when you need to clean up (the house) and also not knowing how to perform certain actions.’ 69

Ignominy and routinisation: ‘this condition was devastating to watch, to(wife’s name)who was always rather coy, shy about the activities of bodily functions, to have her more or less on a timeslot and put into a machine, ‘cos they’d had lunch, lifted up and wheeled into the toilet – that was very devastating… I didn’t like to see her suffering these sorts of indignities.’ 58 ‘She passes stool and handles the faecal matter. Makes a mess and this then cannot be cleaned. The whole household stinks. There is smell of faeces always. Nobody will help. Even my husband, that is her own brother, does not want to be at home. He cannot stand the bad smell.’ 103 |

| CMO: Where communities of identity exist (C), people with dementia are seen to go about their business, their growth and development is then visually acknowledged so people develop an understanding of their needs and daily challenges. Through compassion (M) this may aid community development (O). | Communities of identity: ‘…where people living with dementia are normalized not only in terms of their day care activity—by not being treated as passive consumers of ‘treatments’ or ‘services’ but as active agents of their own preferences and activities—but also as people to be publicly seen going about their usual business. Furthermore, people not directly involved with care for people living with dementia are encouraged to participate in that care and to obtain basic understandings of both the challenges of living with dementia and also the challenges in its daily care. Thus the levels of public education about living with dementia and its care are significantly raised….’54 |

The fourth age has been theorised as a ‘black hole’ into which the effort and energy of caring falls into.102 We found no evidence of the reciprocity associated with dyadic caring relationships. There was however evidence of people transferring their acquired caring skills to the community. We hypothesise that this would result in the acquisition of network members that may contribute to care. Ultimately, this may begin to bring a shift in how society views someone dying with dementia, thus contributing to the way a person becomes a ‘person with dementia’ in the first instance. We did not find empirical data to corroborate this theory.

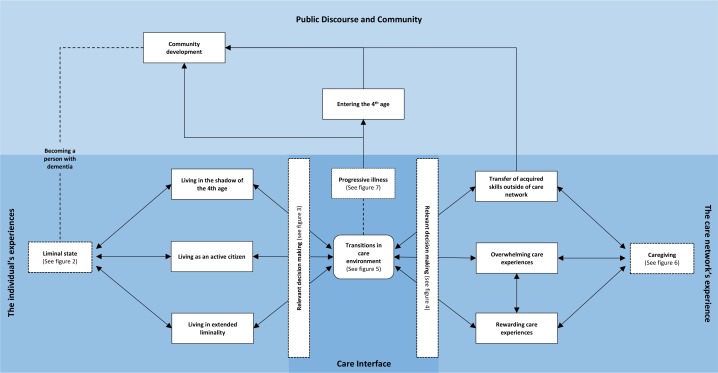

Figure 8 provides an overarching programme theory that depicts the relationship between each of the five subsections. Links represented by a dashed line represent unsubstantiated theory. The multiple contexts explored through the results section are situated in our programme theory under the umbrella terms; ‘liminal state—figure 2’; relevant decision making—figures 3 and 4; caregiving—figure 6; progressive illness—figure 7.

Figure 8.

Overarching programme theory. Rectangle=outcome; rounded edge rectangle=context; broken border=umbrella term for multiple contexts identified in corresponding figure; arrow=signifies CMO configuration; broken arrow=unsubstantiated theory without supplementary CMO data. CMO, context-mechanism-outcome(O)

Discussion

Summary of findings

This realist review of 118 studies has begun to uncover the complex relationships involved in the end-of-life journey. We have shown that human relationships, at an interpersonal, community and professional level, help shape decision making, thus bringing about change through key transitional states. Importantly, these relationships have the power to dictate outcomes; yet, their influence is not uniformly positive.

The review acknowledges the importance of the multiple contexts within which end-of-life care is played out. In doing so, we do not aim to produce evidence about the relative advantages or disadvantages of interventions that improve end-of-life care. We instead argue that the complexity inherent in the process requires in-depth understanding and multifaceted solutions. By exploring the underlying mechanisms that occur within certain contexts, we have developed a provisional theory that may act as a starting point on which to build, while helping public health interventions to be tailored more effectively.

Comparisons with existing literature

Despite a growing evidence base on the role of social networks and social capital in healthcare, there is still significant emphasis on professionally enacted interventions.47 90 91 104 This emphasis is underpinned by a culture that seeks immediately recognisable outcomes of mutual benefit to care receivers and providers. We found that where care is disjointed from how it has evolved in the home, it is less likely to bring meaningful results or be valued by those involved in the day-to-day care of a person with dementia.

A public health approach to palliative care promotes the development of communities that share responsibility for the care of the terminally ill and the bereaved.54 Dementia however is an illness like no other; the cognitive changes can outstrip the physical leading to a rapid dissolution of social capital on which this theory is dependent. In addition, the public discourse and fear that surrounds dementia reinforce the polarised view that caring for these people is primarily the responsibility of immediate family or of health and social care services.

Our results suggest that as people affected by dementia take a more active role in society, there is potential for growth and change to the broader sociopolitical dynamic and structures that influence public perception of dementia. While the individuals’ social networks may dwindle, there is potential for community growth through the transference of skills acquired. This concept is recognised by Bartlett’s social citizenship theory and its implications for social and healthcare practices.5

Recommendations for policy and practice

Making death, dying and dementia everyone’s business

Our findings stress the importance of human relationships across a range of interlinking networks that impact on care outcomes. Given this, it would not be adequate to implement interventions that target one specific group (lay or professional). Rather a cultural shift is required across wider societal and organisational practices that contribute to notions of responsibility and duty of care. Below are a series of practical points as to how this might be achieved.

Promote early engagement with existing social networks and social structures

When cohesive networks of people form around a person with dementia, it is more likely they will be empowered to live as an active citizen. This is more likely to occur and have lasting benefits if it is done at an early stage.

To achieve this outcome, employers of people with dementia, and of people who care for someone with dementia, need to accommodate for their needs. Families, and those lay people directly involved with care, need to acknowledge that dementia may lead to a change in identity. Allowing this identity to grow rather than trying to maintain a historical identity can facilitate a person with dementia becoming an active citizen and allow a more positive care giving experience that focuses less on grief and loss. At the same time, professional bodies must work to change the frequently encountered discourse that dementia is simply ‘death in the realm of the living’. This must be done at every level of our medical institutions not least in the way dementia is taught at undergraduate level.

Facilitate decision making

We must facilitate decision making processes by shining a light on how cognitive social capital influences decision making. For example, advance care planning should not be prescribed for all as a measure of ubiquitous value. Instead, we must use the information from this review which outlines how decisions are made and their potential to sometimes marginalise the expressed wishes of someone with dementia. Using this, more tailored public health interventions can be built to ensure decision making upholds a person’s role as an active citizen.

Understand transitions in the care environment as a process to be influenced rather than an outcome to be avoided

When transitions occur, the outcome is more likely to be positive when professionals and lay networks of care convene around themes of narrative and identity growth relating to the person with dementia. Understanding the influence of social capital in determining how this process unfolds is likely to yield more positive results than focussing on preventing transitions in care.

Promote the message that health and illness can and do co-exist

We found numerous anecdotes of joy within the literature. Joy involved in the caregiving process and joy felt at life events experienced by people living with dementia. Acknowledging that life continues as illness progresses is key to engaging people from all backgrounds in the care process. Greater publicity and acknowledgement of the skills acquired in care giving and the rewards of this role are needed.

Create a platform for mutual knowledge exchange between professionals, people with dementia and lay members of their care network

We found that where care is provided in a routine, top-down manner, irrespective of a person’s evolving identity and the knowledge and expertise held by their care network, the process becomes fraught with conflict. In order to harness the therapeutic potential of caring relationships, we should instead foster an environment of mutual knowledge exchange while appreciating that limitations exist on either side of the professional—lay divide. This needs to be better incorporated into training for professionals looking after people with dementia.

Acknowledge and value the skills developed through caregiving as tools for community development

We found that people develop a unique skill set through caregiving. In certain contexts, there is potential for the transference of these skills to the community. This may aid community development, thus contributing to the wider cultural shift outlined in (i).

Strengths and limitations

This review has been conducted in accordance with the methodological guidance for realist reviews as described in the RAMESES quality standards.31 The use of a broad search strategy was particularly helpful when evaluating an often ambiguous term such as social capital. The iterative nature of both the search and the analysis has allowed us to contextualise our definition of social capital. Realist methodology has also allowed us to focus on how contexts influence the variety of outcomes seen in end-of-life care. By identifying generative mechanisms, we hope to have articulated findings that are relevant across a range of settings.

Naturally, our findings are limited by the quality, breadth and specificity of available literature. We found social networks were often studied from a narrow perspective and defined as a set of dyadic relationships rather than communities of individuals. Social networks were often examined form professionally centred perspectives meaning they were used as a metaphor for ‘lay’ or ‘informal’ caring. Social networks therefore became synonymous with a rather generic approach (eg, partner, family or friends), which were rarely differentiated or compared. End points were frequently studied from a medical perspective (eg, hospital admission, nursing home transfer) leading to the assumption that medically defined priorities match those of the individual and their care network. The lack of empirical evidence suggests that while human relationships can be demonstrated to impact on care trajectories, the specific functions and their relationships with specific community or network structures could not be explored in any detail.

In using a systematic realist approach, we hope that our programme theory can be applied across a range of populations. At the same time, we recognise that inferences drawn from the data are subject to the lead researcher’s perspective. Reflexivity is key in conducting such work, and therefore, the context and personal assumptions of the main researcher were considered when reviewing references. Regular review of the emerging programme theory within the research team was also helpful in addressing this. We did not have a lay person affected by dementia to review gaps and inconsistencies with CMOCs. This combined with gaps in the empirical data mean our programme theory is likely to need modification as our knowledge of the topic expands.

Conclusion

Comparatively few interventions and/or end-of-life policies are designed to address the complexities highlighted by the multiple contexts and mechanisms identified in this review. As a public health approach to palliative care gathers pace, it is important that ‘community’ or ‘social capital’ is not viewed as a universal solution to the mounting public health crisis. This study highlights the need to take a more dispassionate approach, studying its potential in all its complexity in order to further understand what works for whom and in what circumstances.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Geoff Wong and Dr Chrysanthi Papoutsi for methodological support and teaching in realist methods via the Nuffield Departments of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford.

Footnotes

Twitter: @sawyer_joe, @drlizsampson

Contributors: JMS conceived the idea and designed the review. JMS and NK designed, piloted and built the search. JMS, NK, LS and ELS contributed to the interpretation of findings. JMS drafted the initial manuscript, and NK, LS, PS and ELS contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding: JMS is supported by the National Institute for Health Research Academic Clinical Fellowship Programme. ELS and PS are supported by Marie Curie Core grant funding, grant number MCCC-FCO-16-U. NK is supported by Alzheimer’s Society Junior Fellowship grant funding, grant number 399 AS-JF-17b-016.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Waite L. Dementia: an international crisis? Perspect Public Health 2012;132:154–5. 10.1177/1757913912450648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Organization WH Dementia: a public health priority. World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Macdonald G. Death in life or life in death? Dementia’s ontological challenge. Death Stud 2018;42:290–7. 10.1080/07481187.2017.1396398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilks SE, Little KG, Gough HR, et al. . Alzheimer's aggression: influences on caregiver coping and resilience. J Gerontol Soc Work 2011;54:260–75. 10.1080/01634372.2010.544531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartlett R, O’Connor D, Mann J. Broadening the dementia debate: towards social citizenship 2010.

- 6. Kitwood TM. Dementia reconsidered: the person comes first. Buckingham: Open university press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. . The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529–38. 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xie J, Brayne C, Matthews FE. Survival times in people with dementia: analysis from population based cohort study with 14 year follow-up. BMJ 2008;336:258–62. 10.1136/bmj.39433.616678.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hagen B. Nursing home placement: factors affecting caregivers' decisions to place family members with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs 2001;27:44–53. 10.3928/0098-9134-20010201-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fisher L, Lieberman MA. A longitudinal study of predictors of nursing home placement for patients with dementia: the contribution of family characteristics. Gerontologist 1999;39:677–86. 10.1093/geront/39.6.677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alliance WPC. Organisation WH. global atlas of palliative care at the end of life 2014.

- 12. Saunders C. A personal therapeutic journey. BMJ 1996;313:1599–601. 10.1136/bmj.313.7072.1599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pask S, Pinto C, Bristowe K, et al. . A framework for complexity in palliative care: a qualitative study with patients, family carers and professionals. Palliat Med 2018;32:1078–90. 10.1177/0269216318757622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:321–6. 10.1001/archinte.164.3.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Erel M, Marcus E-L, Dekeyser-Ganz F. Barriers to palliative care for advanced dementia: a scoping review. Ann Palliat Med 2017;6:365–79. 10.21037/apm.2017.06.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abel J, Kellehear A. Palliative care reimagined: a needed shift. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:21–6. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kellehear A. Compassionate cities. Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kellehear A. Third-wave public health? compassion, community, and end-of-life care. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies 2004;1:313–23. 10.1002/aps.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sallnow L, Richardson H, Murray SA, et al. . The impact of a new public health approach to end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2016;30:200–11. 10.1177/0269216315599869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whitelaw S, Clark D. Palliative care and public health: an asymmetrical relationship? Palliative Care: Research and Treatment 2019;12 10.1177/1178224218819745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. Cultural theory: An anthology 1986;1:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Portes A. Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu Rev Sociol 1998;24:1–24. 10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Putnam RD. Tuning in, tuning out: the strange disappearance of social capital in America. PS: Political science & politics 1995;28:664–83. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review 1998;23:242–66. 10.5465/amr.1998.533225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reeves D, Blickem C, Vassilev I, et al. . The contribution of social networks to the health and self-management of patients with long-term conditions: a longitudinal study. PLoS One 2014;9:e98340 10.1371/journal.pone.0098340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000316 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abel J, Kingston H, Scally A, et al. . Reducing emergency hospital admissions: a population health complex intervention of an enhanced model of primary care and compassionate communities. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e803–10. 10.3399/bjgp18X699437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Runge C, Gilham J, Peut A. Transitions in care of people with dementia. A systematic review of the literature. Report for the Primary Dementia Collaborative Research Centre 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bhaskar R. A realist theory of science: Routledge, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation London. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. . RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:1005–22. 10.1111/jan.12095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. . Realist synthesis: an introduction. Manchester: ESRC Research Methods Programme, University of Manchester, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Papoutsi C, Mattick K, Pearson M, et al. . Social and professional influences on antimicrobial prescribing for doctors-in-training: a realist review. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72:2418–30. 10.1093/jac/dkx194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ 2005;331:1064–5. 10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cheston R, Bender M. Understanding dementia: the man with the worried eyes. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers Ltd, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nolan M, Brown J, Davies S, et al. . The senses framework: improving care for older people through a relationship-centred approach. getting research into practice (grip) report 2006;2. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baum F. The new public health. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. . Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10 Suppl 1:21–34. 10.1258/1355819054308530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ducharme F, Couture M, Lamontagne J. Decision-Making process of family caregivers regarding placement of a cognitively impaired elderly relative. Home Health Care Serv Q 2012;31:197–218. 10.1080/01621424.2012.681572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liken MA. Caregivers in crisis: moving a relative with Alzheimer's to assisted living. Clin Nurs Res 2001;10:52–68. 10.1177/c10n1r6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud 1999;23:197–224. 10.1080/074811899201046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Turner V. Dramas, fields, and metaphors: symbolic action in human Society. Cornell University Press, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Van Gennep A. The rites of passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Birt L, Poland F, Csipke E, et al. . Shifting dementia discourses from deficit to active citizenship. Sociol Health Illn 2017;39:199–211. 10.1111/1467-9566.12530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gerritsen D, Kuin Y, Steverink N. Personal experience of aging in the children of a parent with dementia. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2004;58:147–65. 10.2190/UF7R-WXVU-VLGM-6MGW [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Powell T. A piece of my mind. life imitates work. JAMA 2011;305:542–3. 10.1001/jama.2011.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Goodman C, Froggatt K, Amador S, et al. . End of life care interventions for people with dementia in care homes: addressing uncertainty within a framework for service delivery and evaluation. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:42 10.1186/s12904-015-0040-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sadak T, Foster Zdon S, Ishado E, et al. . Potentially preventable hospitalizations in dementia: family caregiver experiences. Int Psychogeriatr 2017;29:1201–11. 10.1017/S1041610217000217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cloutier DS, Penning MJ. Janus at the crossroads: perspectives on long-term care trajectories for older women with dementia in a Canadian context. Gerontologist 2017;57:68–81. 10.1093/geront/gnw158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hurley AC, Volicer L. Alzheimer Disease: "It's okay, Mama, if you want to go, it's okay". JAMA 2002;288:2324–31. 10.1001/jama.288.18.2324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pecanac KE, Wyman M, Kind AJH, et al. . Treatment decision making involving patients with dementia in acute care: a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:1884–91. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gott M, Wiles J, Moeke-Maxwell T, et al. . What is the role of community at the end of life for people dying in advanced age? A qualitative study with bereaved family carers. Palliat Med 2018;32:268–75. 10.1177/0269216317735248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Michael N, O’Callaghan C, Sayers E. Managing ‘shades of grey’: a focus group study exploring community-dwellers’ views on advance care planning in older people. BMC Palliat Care 2017;16:1–9. 10.1186/s12904-016-0175-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kellehear A. Compassionate communities: end-of-life care as everyone's responsibility. QJM 2013;106:1071–5. 10.1093/qjmed/hct200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Afram B, Verbeek H, Bleijlevens MHC, et al. . Predicting institutional long-term care admission in dementia: a mixed-methods study of informal caregivers’ reports. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1351–62. 10.1111/jan.12479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Forbes DA, Finkelstein S, Blake CM, et al. . Knowledge exchange throughout the dementia care journey by Canadian rural community-based health care practitioners, persons with dementia, and their care partners: an interpretive descriptive study. Rural & Remote Health 2012;12:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shanley C, Russell C, Middleton H, et al. . Living through end-stage dementia: the experiences and expressed needs of family carers. Dementia 2011;10:325–40. 10.1177/1471301211407794 [DOI] [Google Scholar]