Abstract

Objective

Hispanics/Latinos, the largest immigrant population in the USA, undergo the process of acculturation and have a large burden of heart failure risk. Few studies have examined the association of acculturation on cardiac structure and function.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

The Echocardiographic Study of Latinos.

Participants

1818 Hispanic adult participants with baseline echocardiographic assessment and acculturation measured by the Short Acculturation Scale, nativity, age at immigration, length of US residence, generational status and language.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Echocardiographic assessment of left atrial volume index (LAVI), left ventricular mass index (LVMI), early diastolic transmitral inflow and mitral annular velocities.

Results

The study population was predominantly Spanish-speaking and foreign-born with mean residence in the US of 22.7 years, mean age of 56.4 years; 50% had hypertension, 28% had diabetes and 44% had a body mass index >30 kg/m2. Multivariable analyses demonstrated higher LAVI with increasing years of US residence. Foreign-born and first-generation participants had higher E/e′ but lower LAVI and e′ velocities compared with the second generation. Higher acculturation and income >$20K were associated with higher LVMI, LAVI and E/e′ but lower e′ velocities. Preferential Spanish-speakers with an income <$20K had a higher E/e′.

Conclusions

Acculturation was associated with abnormal cardiac structure and function, with some effect modification by socioeconomic status.

Keywords: acculturation, echocardiogram, hispanics/latinos, socioeconomic status

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A population-based cohort study design focusing on the predominantly immigrant Hispanic/Latino population in the USA.

A detailed comprehensive echocardiographic examination was performed to determine cardiac structure and function in every participant.

By including several acculturation measures (nativity, years of US residence/age at migration, Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics subscales, language preference and generational status), our goal was to be comprehensive and to capture several aspects of acculturation.

We are specifically referring to acculturation into the US culture, which may not be generalisable to acculturation in other settings.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and heart failure (HF) risk factor burden is higher among Hispanic/Latinos in the USA1 2 compared with non-Hispanic whites leading to abnormalities of cardiac structure and function,3 which have been associated with incident clinical HF,4 incident CVD and increased mortality.5–8

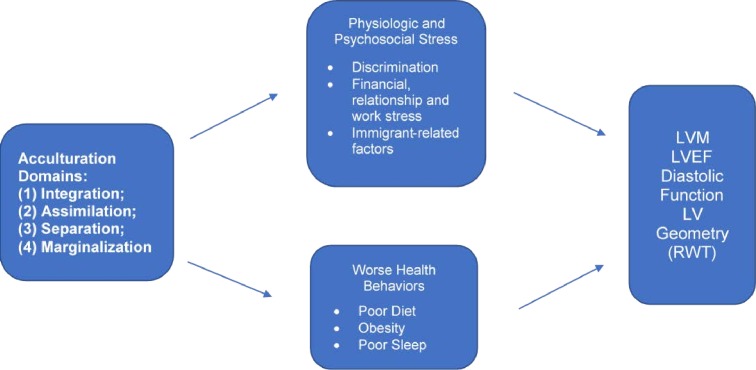

Hispanics/Latinos have a higher incidence of HF as compared with non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics/Latinos who present with HF are younger with more comorbidities and a lower left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) compared with non-Hispanic whites.2 9–11 Beyond traditional HF risk factors (hypertension, diabetes and obesity), sociocultural factors such as acculturation, may contribute to HF risk among Hispanic/Latinos (figure 1),2 but the impact of acculturation on cardiac structure and function has not been examined. The fact that Hispanics/Latinos are the largest immigrant population in the USA accentuates the public health impact of studying the influence of acculturation on cardiac parameters.

Figure 1.

Proposed relationships between acculturation with cardiac structure and function. LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Acculturation is a multidimensional process whereby immigrants adapt to the beliefs and practices of a host culture.12 This can pose a chronic daily stressor for many immigrants that can affect physical health outcomes. Higher acculturation levels have been associated with increased psychosocial stress, deleterious CV health behaviours and a higher CV risk factor burden.13–16 In our mechanistic framework, the acculturative process leads to increase stress and worse health behaviours that separately or jointly alter cardiac structure and function to increase HF risk. Few studies17 18 have examined acculturation in relation to HF risk specifically focusing on cardiac structure and function as key intermediary outcomes.

We primarily sought to test whether acculturation, an important sociocultural variable with biopsychosocial implications, is associated with cardiac structure and function among Hispanics/Latinos. Studies of acculturation and CVD often overlook socioeconomic status (SES) as an effect modifier. Because SES is associated with cardiac parameters19 and modifies the association between acculturation and other health-related variables,20 secondarily, we sought to test whether our primary associations are moderated by SES.

Methods

Cohort description

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) is a population-based study of 16 415 Hispanic/Latinos from randomly selected households at four US field centres (Bronx, New York; Chicago, Illinois; Miami, Florida; and San Diego, California).21 Probability sampling was used to ensure broad representation of the target population and to minimise the sources of bias that may otherwise enter into the cohort selection and recruitment process. Participants were between 18 and 74 years of age and self-identified as Cuban, Central American, Dominican, Mexican, Puerto Rican or South American Hispanic/Latino heritage. The Echocardiographic Study of Latinos (ECHO-SOL) ancillary study was designed to provide echocardiographic parameters characterising cardiac structure and function in a representative HCHS/SOL baseline subsample of 1818 participants ≥45 years old.3 22 All ECHO-SOL participants gave informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in the development of the research question, design, recruitment or implementation of this research cohort study. Results were disseminated to study participants in the form of a data book and periodic newsletters (see www.saludsol.net).

In-person examination

The examination protocol for the parent HCHS/SOL has been previously published.13 Obesity was defined as a body mass index ≥30.0 kg/m2. Seated resting blood pressures were measured in triplicate, and the average of the second and third readings was used for analysis. Type 2 diabetes was defined based on American Diabetes Association definition using one or more of the following criteria: (1) fasting serum glucose >126 mg/dL, (2) oral glucose tolerance test >200 mg/dL, (3) self-reported diabetes, (4) hemoglobin a1c (HbA1C)>6.5% or (5) taking antidiabetic medication or insulin. Renal function was measured by estimated glomerular filtration rate. Physical activity levels, categorised as low or medium/high, were assessed using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire.23 Self-report questionnaires assessed smoking status (no/ever/current), alcohol consumption (current/no) and insurance coverage (yes/no) and type (private/Medicare/Medicaid). Educational level was defined as highest degree or level of school completed. Current household income while living in the USA was dichotomised as <$20 000 and >$20 000, given the low number of participants with incomes >$40 000. Our secondary analysis focused on current income as a more relevant influencer of a participant’s acculturative process, acting as a proxy for the ability to integrate and be exposed to mainstream US cultural contexts. Marital status was categorised as either single, married, partnered, separated, divorced or widowed.

Echocardiographic measurements

Trained sonographers performed transthoracic echocardiography examinations, including two-dimensional imaging, and spectral, colour and tissue Doppler.22 Echocardiographic measures of left and right heart structure and function included:

LV mass index (LVMI) was determined according to guidelines,24 by subtracting the LV endocardial cavity volume from the LV epicardial volume and multiplying the resultant myocardial volume by the myocardial density and indexing to body surface area.

LV systolic function and volumes. LVEF was derived from volumetric assessments using the method of discs from apical 4-chamber and 2-chamber long-axis views to measure end-diastolic volume (EDV) and end-systolic volume (ESV). LVEF was calculated: (EDV − ESV) ⁄ EDV.

LV diastolic function was defined per guidelines,25 using three echocardiographic parameters: (1) peak early (E) and late (A) diastolic transmitral inflow velocities; (2) early diastolic (e′) annular velocities (the average of septal and lateral annular velocities were used); (3) left atrial volume indexed (LAVI) to body surface area.

Relative wall thickness (RWT) predicates LV geometry and was defined as: [(posterior LV wall thickness × 2)/LV diastolic diameter]. Higher RWT values are associated with a smaller LV cavity size, and lower RWT values are associated with higher LV cavity sizes.

Acculturation measures

Acculturation was defined using several validated measures. First, nativity was classified as either born in or outside the US mainland (50 states). Those born in Puerto Rico (PR) or other US territories were classified as born outside of the US mainland to reflect their migration and acculturation experiences. Second, foreign-born individuals were asked the number of years lived in the USA and categorised as <5, 5–10, 11–20 and >20 years. We used the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH),26 which has two subscales based on 5-point Likert type questions: (1) the SASH language subscale (items related to language use (eg, language they speak and think)); and (2) the SASH social relations subscale (items related to media preference and social affiliations (eg, language of media programmes watched; ethnicity of close friends)). The SASH has yielded reliabilities (α) of 0.92 (overall), 0.90 (language use), 0.86 (media preference) and 0.78 (ethnic and social relations). These subscales were analysed separately with higher scores representing higher degrees of acculturation. Fifth, language preference was further characterised as English versus Spanish based on language of interview. Finally, data on generational status (first-generation and second-generation Hispanics are US born and distinct from their foreign-born immigrant parents) was collected as well as age at the time of migration to the USA.

Statistical analyses

Sampling weights were used to obtain weighted frequencies of descriptive variables and population estimates in the ECHO-SOL target population. We used means±SEs for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. LVMI, RWT, LVEF, e′ annular velocities and LAVI were analysed as continuous variables. LV diastolic dysfunction (LVDD) was analysed as a binary variable (present vs absent).3 Acculturation variables were categorical (foreign born vs US born; first generation vs second generation; Spanish language preference vs English), ordinal (<5, 5–10, 11–20 and >20 years in the USA) and continuous measures (age at immigration and SASH subscales). Weighted means and linear regression analysis was used for continuous variables whereas weighted frequencies and Rao-Scott χ2 was used for the categorical/ordinal variables. Means were compared across categorical acculturation variables using regression analysis for each dependent variable measure of cardiac structure (LVMI, RWT and LAVI) and function (LVEF, e′ and E/e′). Only associations that were statistically significant in unadjusted analyses were further explored in multivariable analysis. Unadjusted and multivariable linear and logistic regression analyses were determined by our continuous and categorical dependent variable, respectively, using sequential modelling for age and sex followed by models including clinical covariates (diabetes, hypertension and obesity), and behavioural characteristics (physical activity, tobacco use and alcohol use). For years in the USA, we compared >20 years–<5 years as well as an overall comparison across each category of years in the USA. We performed a couple of sensitivity analyses (data not shown): (1) comparing acculturative characteristics of individuals born in the island of PR versus other foreign-born Hispanics; (2) comparing acculturation and healthcare utilisation using HCHS/SOL questions regarding difficulty obtaining healthcare in the past year and number of physician visits in the past year. We tested effect moderation with income through the use of interaction terms in models followed by stratified analyses by income for statistically significant interactions at the p<0.01 level. All other statistical tests were two sided at a significance level of 0.05. All reported values were weighted to account for HCHS/SOL sampling probability design, stratification, clustering and non-response and to make estimates applicable to the HCHS/SOL target population. All analyses were performed using SAS V.9.3 PROC SURVEY procedures.

Results

The study sample included 1818 participants; 57% were women and almost half (46%) had a reported annual income under $20 000.Over half of the study participants were married and most had some type of health insurance (mostly Medicaid and/or Medicare). Hypertension and diabetes were prevalent in half and almost one-third of the study population respectively. Most of the study population was foreign born, only 14% preferred English, almost half (49%) had been in the USA >20 years with a mean age of migration of 34 years of age, signifying that the majority came to the USA as adults (table 1). Mean values of echocardiographic variables (LAVI, RWT, LVMI and LVEF) were all within normal limits for this study population. However, mean e′ annular velocities and E/e′ ratio were borderline abnormal. Some degree of diastolic dysfunction was seen in over half (52%) of the study population, as previously described.3

Table 1.

ECHO-SOL demographic and clinical characteristics (n=1818)*

| Demographic characteristics | (N (%)) |

| Women | 1187 (57.4) |

| Age (mean (SE)) | 56.4 (0.37) |

| High school graduate or higher | 726 (43.3) |

| Annual family income >$20 000 | 787 (45.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 332 (18.8) |

| Married/partner | 961 (53.2) |

| Separated/divorced/widow | 522 (28.0) |

| Health insurance | 1042 (60.1) |

| Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics | (Mean (SE)) |

| Language use subscale | 1.7 (0.05) |

| Social relations subscale | 2.1 (0.03) |

| Length of US residence (years) | (N (%)) |

| <5 years | 178 (13.6) |

| 5–10 years | 247 (15.2) |

| 11–20 | 385 (22.1) |

| >20 | 842 (49.1) |

| Second generation or higher | 185 (9.3) |

| English language preference | 225 (14.0) |

| Age at migration (mean (SE)) | 34.0 (1.0) |

| US born | 163 (7.9) |

| Clinical characteristics | (N (%)) |

| Hypertension | 861 (50.0) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 523 (28.4) |

| Current smoker | 304 (17.6) |

| Physical activity level low | 1227 (67.3) |

| BMI ≥30 | 822 (44.3) |

| Current alcohol use | 770 (43.5) |

| Echocardiographic variables | (Mean (SE)) |

| Left atrial volume index (<33 mL/m2) | 23.0 (0.25) |

| Relative wall thickness (0.22–0.42) | 0.40 (0.004) |

| Left ventricular mass index (45–105 g/m2) | 82.7 (0.7) |

| Ejection fraction (>55 %) | 59.8 (0.2) |

| E prime (e’) (8–16 cm/s) | 8.1 (0.09) |

| E/e’ (<12) | 10.0 (0.12) |

| Diastolic dysfunction (N (%)) | 916 (51.9) |

Percentages are weighted row percentages.

Normal values are provided for cardiac structure and function variables.

*Ns presented are unweighted counts of total participants in the ECHO-SOL with each respective characteristic.

BMI, body mass index.

Online supplementary table S1 shows unadjusted relationships between acculturation measures and echocardiographic characteristics. There were statistically significantly higher mean LAVI values across categories of length of time spent in the US, whereas RWT appeared to have a U-shaped association. A statistically significantly lower annular relaxation velocity and higher E/e′ ratio was seen among the foreign born compared with US born and among those first generation compared with second generation. Greater acculturation, as measured by higher SASH language scale scores, was associated with greater LAVI. Younger age of migration to USA was associated with increased RWT and LAVI.

bmjopen-2018-028729supp001.pdf (54.7KB, pdf)

Adjusted analyses (table 2) demonstrated greater time spent in the USA is significantly associated with increased RWT and LAVI. A statistically significantly higher E/e′ ratio was seen among the foreign-born participants. Those first generation had lower LAVI, lower e′ annular velocities and higher E/e′ ratios compared with second generation. Higher SASH language scale scores and younger age of migration to USA were both associated with increased LAVI. These associations persisted in sequential models adjusted for clinical factors and behavioural factors both separately and together. Although greater odds of LVDD was seen in unadjusted associations with nativity, generational status, SASH language and age of immigration (table 3), these associations did not persist on adjusted analysis.

Table 2.

Adjusted analyses of acculturation measures with cardiac structure and function*

| LVMI (g/m2) | RWT | LAVI (mL/m2) | LVEF (%) | E’ (cm/s) | E/e’ | |

| β (p) | β (p) | β (p) | β (p) | β (p) | β (p) | |

| Nativity | ||||||

| Age, sex | −0.349 (0.12) | 0.571 (0.02) | ||||

| Model 1 | — | — | — | — | −0.320 (0.10) | 0.524 (0.02) |

| Model 2 | −0.324 (0.14) | 0.532 (0.02) | ||||

| Model 3 | −0.303 (0.12) | 0.503 (0.02) | ||||

| Foreign born | ||||||

| (Years in the USA) | ||||||

| Age, sex | — | 0.020 (0.06); all (0.03) | 1.57 (0.02); all (<0.05) | — | — | — |

| Model 1 | 0.022 (0.02); all (0.02) | 1.63 (0.02); all (<0.05) | ||||

| Model 2 | 0.018 (0.06); all (0.02) | 1.55 (0.02); all (0.05) | ||||

| Model 3 | 0.021 (0.02); all (0.007) | 1.71 (0.01); all (0.04) | ||||

| Generation | ||||||

| Age, sex | −0.468 (0.21) | −0.529 (0.01) | 0.710 (0.002) | |||

| Model 1 | — | — | −1.797 (0.004) | — | −0.447 (0.01) | 0.594 (0.003) |

| Model 2 | −1.444 (0.03) | −0.499 (0.01) | 0.671 (0.003) | |||

| Model 3 | −1.584 (0.01) | −0.425 (0.02) | 0.575 (0.006) | |||

| SASH language | ||||||

| Age, sex | 0.580 (0.01) | 0.125 (0.10) | ||||

| Model 1 | — | — | 0.610 (0.008) | — | 0.097 (0.11) | — |

| Model 2 | 0.546 (0.01) | 0.123 (0.15) | ||||

| Model 3 | 0.590 (0.007) | 0.095 (0.16) | ||||

| Age at immigration | ||||||

| Age, sex | 0.0005 (0.15) | −0.040 (0.008) | −0.005 (0.27) | |||

| Model 1 | — | 0.0005 (0.13) | −0.040 (0.008) | — | −0.006 (0.14) | — |

| Model 2 | 0.0004 (0.15) | −0.038 (<0.001) | −0.005 (0.37) | |||

| Model 3 | 0.0004 (0.13) | −0.038 (0.01) | −0.005 (0.22) |

For years in the USA, the first p value reflects <5 years versus >20 years comparison, whereas the second p value is for overall comparison across all the years in the US categories (<5; 5–10; 11–20; >20). Model 1: age, sex, diabetes, hypertension and obesity; model 2: age, sex, physical activity, tobacco and alcohol use; model 3: model 1+model 2.

*Only acculturation measures that were significant in unadjusted analyses were analysed in multivariable adjusted models.

e’, mitral annular early diastolic velocity; E/e’, ratio between early mitral inflow velocity and mitral annular early diastolic velocity; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction;LVMI, left ventricular mass index; RWT, relative wall thickness; SASH, Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted* analyses of acculturation measures with diastolic dysfunction

| Unadjusted | Adjusted sequential models | ||||

| Age, sex | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||

| Nativity | |||||

| Foreign born | 1.67 (1.08 to 2.58) | 0.98 (0.62 to 1.55) | 0.94 (0.59 to 1.51) | 0.98 (0.62 to 1.55) | 0.95 (0.59 to 1.53) |

| US born | Ref | ||||

| Years in the USA | |||||

| <5 | 0.86 (0.60 to 1.24) | ||||

| 5–10 | 0.72 (0.49 to 1.04) | — | — | — | — |

| 11–20 | 0.91 (0.61 to 1.37) | ||||

| >20 | Ref | ||||

| Generation | |||||

| 1 | 1.90 (1.24 to 2.92) | 1.29 (0.77 to 2.14) | 1.18 (0.74 to 1.91) | 1.26 (0.77 to 2.06) | 1.18 (0.73 to 1.89) |

| 2 | Ref | ||||

| Language preference | |||||

| English | 0.67 (0.34 to 1.32) | — | — | — | — |

| Spanish | Ref | ||||

| SASH language | 0.81 (0.67 to 0.98) | — | — | — | — |

| SASH social | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.15) | — | — | — | — |

| Age at immigration | 1.02 (1.004 to 1.03) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.02) | 1.01 (0.995 to 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) | 1.01 (0.995 to 1.02) |

ORs (95% CIs) are presented.

Model 1: age, sex, diabetes, hypertension and obesity.

Model 2: age, sex, physical activity, tobacco and alcohol use.

Model 3: model 1+model 2.

*Only acculturation measures that were significant in unadjusted analyses were analysed in adjusted models.

Significant interactions (p<0.01) were found between our main exposure (acculturation) and income on the effect of cardiac structure and function. Among those with annual incomes >$20 000, a greater number of years in the USA was associated with higher LVMI, lower e′ annular velocities and a higher E/e′ ratio compared with those making <$20 000 annually. Generational status was associated with increased LAVI only among those making >$20 000 annually. However, being a preferential Spanish speaker carried a statistically significant higher E/e′ ratio only among those making <$20 000 annually (Online supplementary table S2).

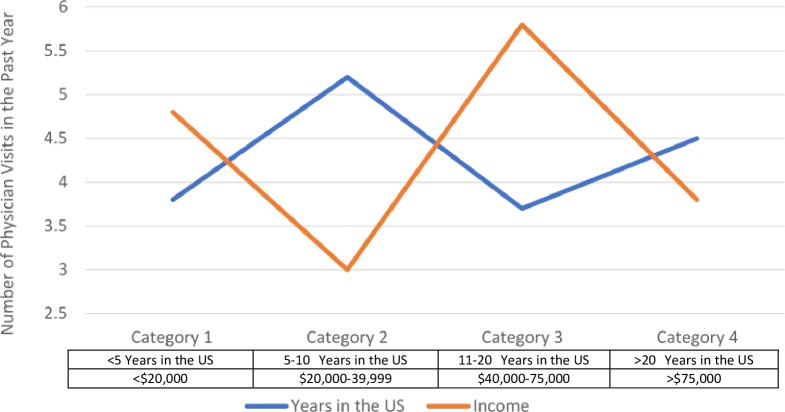

Of foreign-born Hispanics, 24% were born in the US Commonwealth of PR, none in the US Virgin Islands. Spanish language preference was less among Hispanics born in PR compared with other foreign-born Hispanics. PR-born Hispanics scored higher on the SASH language scale and social interaction scale indicating higher acculturation levels compared with other foreign-born Hispanics. However, the level of Spanish language preference and SASH scores was still lower among PR-born Hispanics compared with US-born Hispanics. With regard to acculturation and healthcare utilisation, being foreign-born, having less years in the USA and not having health insurance were all significantly associated with difficulty obtaining healthcare in the past year. Foreign-born individuals had less physician visits over the past year compared with US born. The relation between years in the USA and physician visits was complex, non-linear and mirrored an opposite pattern with income (figure 2). Having health insurance coverage was significantly associated with more physician visits over the past year.

Figure 2.

Relation of years residing in the USA or income level with number of physician visits.

Discussion

Hispanics/Latinos in the USA represent a relatively young demographic such that the future public health burden of HF as this population ages may be underestimated.27 The Hispanic population >65 years of age is expected to grow 328% between 2000 and 2030, making Hispanics the fastest growing ageing population in the USA.28 As the Hispanic population ages, and HF risk factors and cardiac abnormalities progress, it is likely that an epidemic of HF will emerge in this population.

Acculturation is a complex but important phenomenon among immigrant populations that encompasses multiple domains: (1) integration: maintaining the original parent culture while adopting the host culture; (2) assimilation: rejecting the parent culture and entirely adopting the host culture; (3) separation: rejecting the host culture and keeping the parent culture; and (4) marginalisation: not identifying with either the original culture or the host culture.29 The acculturation process can be positive, improved life opportunities in the host culture compared with the parent culture and/or it could be negative due to the challenging nature of change and adaptation to new cultural and social expectations. Prior studies show strong negative effects of greater acculturation on worsening CV risk factors but positive effects on use of preventive health services.30–32 HCHS/SOL has demonstrated significant heterogeneity in CVD risk factor burden among Hispanics/Latinos by country of origin and acculturation measures.13 Our analysis of validated acculturation measures provides several important contributions. First, higher levels of acculturation were associated with abnormal cardiac structure and function in our predominately foreign-born, Spanish-speaking adult population. Second, different measures of acculturation (each capturing different aspects of the acculturative process) had varying associations with different measures of cardiac structure and function (each considered its own specific outcome). Finally, income significantly moderated these associations. Our findings support the premise that exposure to the social and environmental stress of acculturation may promote unhealthy behaviours33 and/or act via undefined pathways of physiological/psychosocial stress to contribute to the increased HF risk seen among Hispanics/Latinos27(figure 1). Additionally, our sensitivity analysis suggests that living in the island of PR still allows for maintenance of a culture that is distinct from the US culture. Further elucidating the complexities of acculturative factors influencing HF risk in immigrant populations is warranted.

Although to our knowledge, there is no existing literature on the association between acculturation and HF risk, our study found several measures of acculturation (increasing years of US residence, English preference and younger age at immigration) were associated with abnormal cardiac structure and function (increased LAVI, increased LVMI, increased RWT, lower annular e′ relaxation velocity and higher E/e′ ratio). Although the magnitudes of our observed associations are modest, limiting the short-term clinical relevance of these findings, the long-term public health importance is likely high, given the potential for progression of cardiac damage with the accumulation of acculturative stress during the life course. This is particularly salient given the fact that abnormal cardiac structure and function is an independent risk factor for the future development of clinical HF. An increased E/e′ ratio, LAVI and LVMI are markers of chronically elevated filling pressures associated with impaired cardiac relaxation and HF with preserved EF.34 35 The presence of abnormal cardiac structure and function has been associated with increased HF hospitalisations, cardiovascular death and improved CV risk prediction.35–37 Importantly, these cardiac abnormalities are additive, with worse outcomes seen in individuals with more than one alteration.35 In order to identify preclinical CV disease, abnormalities in cardiac structure and function determined by echocardiography are important intermediary measures, many of which have been associated with incident CVD, incident clinical HF and increased mortality.5–7 Given the size of the US Hispanic/Latino population and high burden of acculturation (82% were foreign born), echocardiography might help to identify a particularly high risk subset of participants.

Left ventricular mass (LVM) is associated with CVD, sudden cardiac death and all-cause mortality.34 Among foreign-born Hispanics/Latinos, we found increased LVMI with increasing years in the USA. Our study is consistent with prior studies showing a high prevalence of LVM among Hispanics/Latinos especially among low-income Hispanics/Latinos with increasing years of US residence.18 38 39Prior studies have demonstrated that adjustment for socioeconomic factors did not fully account for the presence of increased LVMI among Hispanics/Latinos40 possibly due to the residual effect of acculturation. Changes in LVM can occur without overt clinical hypertension in adrenergic states, such as chronic stress41 with psychosocial factors such as perceived discrimination and low social support.42 43 Acculturative stress is the psychological impact of navigating the acculturation process and making decisions on retaining one’s native culture while adapting to a new cultural context. Acculturation as a chronic stressor may negatively affect mental and physical health through unhealthy behaviours,31 33 increased anxiety, depression, perceived discrimination and lack of social support,15 33 44 all of which may impact adrenergic biomarkers leading to cardiac structural and functional abnormalities and increased HF risk observed in our study. This is an area of research to further explore in future studies.

The statistically significant interaction between acculturation and SES on cardiac measures may shed light on the ‘Hispanic paradox’, which states that Hispanics/Latinos, a disproportionately low SES group, have lower overall mortality and cardiovascular mortality compared with non-Hispanic Whites.2 Low SES is a composite chronic stressor encompassing multiple factors (eg, work, housing and financial strain). Longitudinal studies have shown an inverse association between SES level and adverse outcomes.42 45 We hypothesised that less acculturation (more retention of the parent culture) may be protective of the adverse health consequences of low SES. In our study, those with higher SES (defined as annual incomes >$20 000) exhibited more deleterious effects of increasing acculturation on cardiac structural and functional measures. A prior study found the relationship between acculturation and healthcare utilisation to be complex and moderated by SES.46 Our exploratory analysis found that being foreign born and having a higher income may make one less likely to use healthcare. A more extensive analysis on the complex nature of acculturation and healthcare utilisation is beyond the scope of our paper, but this area deserves further consideration in future studies. There may be more acculturative stress for higher SES immigrants, perhaps through increased contact and interaction with the mainstream culture,47 which may contribute to our findings. Familismo is a culture-specific factor characterised by having strong bonds with nuclear and extended family resulting in a high level of perceived family support and is associated with indicators of improved health.48 49 Studies suggest that with increasing acculturation, familismo is eroded and dimensions of familismo begin to increase psychosocial stress rather than alleviate it.49–51

Several limitations should be noted. Our study is cross-sectional and precludes the ability to assess the temporal sequence of the relationships and causal inference. However, our findings warrant replication and longitudinal follow-up. Participants resided in one of four US cities, precluding generalisability to all Hispanic/Latinos in the USA. While this study is one of the largest studies of acculturation with cardiac structure and function in any population, the sample size is relatively modest; thus, we were underpowered to perform stratified analyses by national origin in order to characterise the heterogeneity within Hispanic/Latinos. We are specifically referring to acculturation into the US culture, which may not be generalisable to acculturation in other settings. Finally, our study focuses on acculturation as a unique intraethnic phenomenon. By including several measures (nativity, years of US residence/age at migration, SASH subscales, language preference and generational status), our goal was to be comprehensive and to capture several aspects of acculturation. We believe acculturation cannot be captured by just one measure, as has been done in much of the prior literature; however, we agree that even our multivariable approach may not fully capture the complexities of all aspects and dimensions of the acculturative process.

Conclusions

In addition to traditional CV risk factors, acculturation may explain the disproportionate burden of HF risk among Hispanics/Latinos. Our study found significant deleterious associations between several acculturation measures with cardiac structural and functional parameters among a predominantly low-SES, foreign-born Hispanic/Latino population with increasing years of residence in the USA. The acculturation experience is not unique to Hispanics/Latinos. Our study may help generate further research in other immigrant populations. Further elucidation of how acculturation impacts HF risk to improve risk stratification and to inform the development of culturally appropriate interventions to amplify protective factors is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff and participants of HCHS/SOL and ECHO-SOL for their important contributions. Investigators website: http://www.cscc.unc.edu/hchs/.

Footnotes

Contributors: Research conception and design: CJR and LL; collection and assembly of data: CJR, MA, RCK and LG; analysis and interpretation of the data: CJR, LL and KS; drafting of the article: CJR, LL and FR; critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: CJR, LL, FR, JRK, FP, LG, WA and FG; obtaining of funding: CJR, RCK and MA; statistical expertise: KS, FG; CJR and LL are responsible for the overall content as guarantors.

Funding: This study supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to the University of North Carolina (N01-HC65233), University of Miami (N01-HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (N01-HC65235), Northwestern University (N01-HC65236) and San Diego State University (N01-HC65237). The following institutes contributed to Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL): National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and NIH Institution-Office of Dietary Supplements. ECHO-SOL was supported by the NHLBI (R01 HL104199, Epidemiologic Determinants of Cardiac Structure and Function among Hispanics: CJR, Principal Investigator). LL acknowledges the support of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program and NIDDK 1K23DK098280-01. FR was supported from a career development award from the NHLBI (1K01 HL144607). No relationships with industry supported this work.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board at the Wake Forest School of Medicine and at each study site(Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York; Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois; University of Miami, Miami, Florida; University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California; Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina) provided approval and oversight of all study materials and activities.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;131:e29–322. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rodriguez CJ, Allison M, Daviglus ML, et al. Status of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: a science Advisory from the American heart association. Circulation 2014;130:593–625. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mehta H, Armstrong A, Swett K, et al. Burden of systolic and diastolic left ventricular dysfunction among Hispanics in the United States: insights from the echocardiographic study of Latinos. Circ Heart Fail 2016;9:e002733 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of cardiology Foundation/American heart association Task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:e147–239. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hobbs FDR, Roalfe AK, Davis RC, et al. Prognosis of all-cause heart failure and borderline left ventricular systolic dysfunction: 5 year mortality follow-up of the echocardiographic heart of England screening study (echoes). Eur Heart J 2007;28:1128–34. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Armstrong AC, Jacobs DR, Gidding SS, et al. Framingham score and LV mass predict events in young adults: cardia study. Int J Cardiol 2014;172:350–5. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bombelli M, Facchetti R, Cuspidi C, et al. Prognostic significance of left atrial enlargement in a general population: results of the PAMELA study. Hypertension 2014;64:1205–11. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Erqou S, Butler J, et al. Assessing the Risk of Progression From Asymptomatic Left Ventricular Dysfunction to Overt Heart Failure: A Systematic Overview and Meta-Analysis. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:237–48. 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vivo RP, Krim SR, Cevik C, et al. Heart failure in Hispanics. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1167–75. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vivo RP, Krim SR, Krim NR, et al. Care and outcomes of Hispanic patients admitted with heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction: findings from get with the guidelines-heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:167–75. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bahrami H, Kronmal R, Bluemke DA, et al. Differences in the incidence of congestive heart failure by ethnicity: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:2138–45. 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zambrana RE, Carter-Pokras O. Role of acculturation research in advancing science and practice in reducing health care disparities among Latinos. Am J Public Health 2010;100:18–23. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.138826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Avilés-Santa ML, et al. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA 2012;308:1775–84. 10.1001/jama.2012.14517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ayala GX, Baquero B, Klinger S. A systematic review of the relationship between acculturation and diet among Latinos in the United States: implications for future research. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108:1330–44. 10.1016/j.jada.2008.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease: an update on current knowledge. Annu Rev Public Health 2013;34:337–54. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Suh M, Barksdale DJ, Logan J. Relationships among acculturative stress, sleep, and nondipping blood pressure in Korean American women. Clin Nurs Res 2013;22:112–29. 10.1177/1054773812455054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peterson PN, Campagna EJ, Maravi M, et al. Acculturation and outcomes among patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:160–6. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Effoe VS, Chen H, Moran A, et al. Acculturation is associated with left ventricular mass in a multiethnic sample: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2015;15:161 10.1186/s12872-015-0157-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rodriguez CJ, Sciacca RR, Diez-Roux AV, et al. Relation between socioeconomic status, race-ethnicity, and left ventricular mass: the Northern Manhattan study. Hypertension 2004;43:775–9. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000118055.90533.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee H, Cardinal BJ, Loprinzi PD. Effects of socioeconomic status and acculturation on accelerometer-measured moderate-to-vigorous physical activity among Mexican American adolescents: findings from NHANES 2003-2004. J Phys Act Health 2012;9:1155–62. 10.1123/jpah.9.8.1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lavange LM, Kalsbeek WD, Sorlie PD, et al. Sample design and cohort selection in the Hispanic community health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol 2010;20:642–9. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rodriguez CJ, Dharod A, Allison MA, et al. Rationale and design of the echocardiographic study of Hispanics/Latinos (ECHO-SOL). Ethn Dis 2015;25:180–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cleland CL, Hunter RF, Kee F, et al. Validity of the global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ) in assessing levels and change in moderate-vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1255 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of echocardiography's guidelines and standards Committee and the chamber quantification writing group, developed in conjunction with the European association of echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005;18:1440–63. 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Appleton CP, et al. Clinical utility of Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressures: a comparative simultaneous Doppler-catheterization study. Circulation 2000;102:1788–94. 10.1161/01.cir.102.15.1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, et al. Development of a short Acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci 1987;9:183–205. 10.1177/07399863870092005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rangel MO, Kaplan R, Daviglus M, et al. Estimation of incident heart failure risk among US Hispanics/Latinos using a validated echocardiographic risk-stratification index: the echocardiographic study of Latinos. J Card Fail 2018;24:622–4. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. US Census Bureau 65+ in the United States:2005. current population reports, 2005. December. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, et al. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. American Psychologist 2010;65:237–51. 10.1037/a0019330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moran A, Diez Roux AV, Jackson SA, et al. Acculturation is associated with hypertension in a multiethnic sample. Am J Hypertens 2007;20:354–63. 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abraído-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Flórez KR. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation?: implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1243–55. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. DuBard CA, Gizlice Z. Language spoken and differences in health status, access to care, and receipt of preventive services among US Hispanics. Am J Public Health 2008;98:2021–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, et al. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health 2005;26:367–97. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abbate A, Arena R, Abouzaki N, et al. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: refocusing on diastole. Int J Cardiol 2015;179:430–40. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.11.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shah AM, Claggett B, Sweitzer NK, et al. Cardiac structure and function and prognosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: findings from the echocardiographic study of the treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:740–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zile MR, Gottdiener JS, Hetzel SJ, et al. Prevalence and significance of alterations in cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 2011;124:2491–501. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.011031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Burke MA, Katz DH, Beussink L, et al. Prognostic importance of pathophysiologic markers in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:288–99. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zabalgoitia M, Ur Rahman SN, Haley WE, et al. Impact of ethnicity on left ventricular mass and relative wall thickness in essential hypertension. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:412–7. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00925-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rodriguez CJ, Diez-Roux AV, Moran A, et al. Left ventricular mass and ventricular remodeling among Hispanic subgroups compared with non-Hispanic blacks and whites: MESA (multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:234–42. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rodriguez CJ, Lin F, Sacco RL, et al. Prognostic implications of left ventricular mass among Hispanics: the Northern Manhattan study. Hypertension 2006;48:87–92. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000223330.03088.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Julius S, Li Y, Brant D, et al. Neurogenic pressor episodes fail to cause hypertension, but do induce cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension 1989;13:422–9. 10.1161/01.HYP.13.5.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson KW, et al. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: the emerging field of behavioral cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:637–51. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rodriguez CJ, Elkind MSV, Clemow L, et al. Association between social isolation and left ventricular mass. Am J Med 2011;124:164–70. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gallo LC, Penedo FJ. Espinosa de Los Monteros K, Arguelles W. Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? J Pers 2009;77:1707–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gallo LC, de los Monteros KE, Allison M, et al. Do socioeconomic gradients in subclinical atherosclerosis vary according to acculturation level? analyses of Mexican-Americans in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Psychosom Med 2009;71:756–62. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b0d2b4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peng B-L, Zou G-Y, Chen W, et al. Association between health service utilisation of internal migrant children and parents' acculturation in Guangdong, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e018844 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McClure LA, Zheng DD, Lam BL, et al. Factors associated with ocular health care utilization among Hispanics/Latinos: results from an ancillary study to the Hispanic community health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134:320–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Davila YR, Reifsnider E, Pecina I. Familismo: influence on Hispanic health behaviors. Applied Nursing Research 2011;24:e67–72. 10.1016/j.apnr.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, et al. Hispanic Familism and Acculturation: What Changes and What Doesn't? Hisp J Behav Sci 1987;9:397–412. 10.1177/07399863870094003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Miranda AO, Estrada D, Firpo-Jimenez M. Differences in family cohesion, adaptability, and environment among Latino families in dissimilar stages of acculturation. The Family Journal 2000;8:341–50. 10.1177/1066480700084003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rodriguez N, Mira CB, Paez ND, et al. Exploring the complexities of familism and acculturation: central constructs for people of Mexican origin. Am J Community Psychol 2007;39:61–77. 10.1007/s10464-007-9090-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028729supp001.pdf (54.7KB, pdf)