Abstract

Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy, defined as the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services is responsible in part for suboptimal levels of vaccination coverage worldwide. The WHO recommends that countries incorporate plans to measure and address vaccine hesitancy into their immunisation programmes. This requires that governments and health institutions be able to detect concerns about vaccination in the population and monitor changes in vaccination behaviours. To do this effectively, tools to detect and measure vaccine hesitancy are required. The purpose of this scoping review is to give a broad overview of currently available vaccine hesitancy measuring tools and present a summary of their nature, similarities and differences.

Methods and analysis

The review will be conducted using the framework for scoping review proffered by Arksey and O’Malley. It will comply with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews’ guidelines. The broader research question of this review is: what vaccine hesitancy measuring tools are currently available?

Search strategies will be developed using controlled vocabulary and selected keywords. PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and reference lists of relevant publications will be searched. Titles and abstracts will be independently screened by two authors and data from full-text articles meeting the inclusion criteria will be extracted independently by two authors using a pretested data charting form. Discrepancies will be resolved by discussion and consensus. Results will be presented using descriptive statistics such as percentages, tables, charts and flow diagrams as appropriate. Narrative analysis will be used to summarise the findings of the review.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval is not required for the review. It will be submitted as part of a doctoral thesis, presented at conferences and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

Keywords: vaccine hesitancy, immunization, vaccination, tools, scoping reviews, Public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The review will bring to the fore gaps that exist in the area of contextual development and validation of vaccine hesitancy measuring tools.

The non-prescriptive study selection criteria will broaden the scope of included literature.

Compliance with the PreferredReporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for ScopingReviews will enable the review to be one of its earliest use and test of impact.

No meta-analysis is planned for this scoping review.

Introduction

The significant contributions of vaccination to the health and general well-being of the human race cannot be overemphasised. The drastic reduction in the mortality, morbidity and disability rates due to Vaccine Preventable Diseases (VPDs) worldwide since its introduction are great testimonials to the efficacy of vaccination. It has been estimated that over 3 million deaths and 75 000 disabilities are prevented annually by vaccination.1 This makes it one of the most successful public health interventions of modern times.2 The progress made in vaccination coverage over the years was further accentuated and accelerated by the introduction of the WHO’s Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in 1974.3 EPI is a resounding success in most parts of the world. The global immunisation coverage (indicated by the percentage of children who has received the third dose of diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis vaccine4 5 is estimated at 86% in 2015 according to WHO and UNICEF data on global immunisation. This coverage is said to have been sustained above 85% since the year 2010.6 To continue to be a public health success, vaccines needs to be accepted and trusted by its target populace, and broadly and adequately used.7

The global challenge of vaccine hesitancy

The estimates reported above are calculated using the official national immunisation coverage figures reported to WHO-UNICEF by member states.4 They however, fall short of the Global Vaccine Action Plan’s target of 90% coverage at national level and 80% coverage at district levels for the Decade of Vaccines, that is, 2011 to 2020.6 8 Moreover, national coverage levels have been known to ‘mask’ variations within countries, concealing clusters of subnational geographical or sociological areas where coverage is much lower.5 6 These areas with low or suboptimal vaccination coverage have provided fertile breeding grounds for intermittent outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases in various parts of the world, including developed and developing countries.9–11 These outbreaks have been attributed, in part, to the delay or outright refusal of some members of the population to vaccinate themselves or their children even when such services are available.

This phenomenon, that is, the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services, is defined as vaccine hesitancy.12 Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context specific, and varies across time, place and vaccines.12 13 It can be described on a continuum ranging from those who accept all vaccines without any doubt to those who reject all without any doubt. The large, heterogeneous group of individuals between these two extremes exhibits varying degrees of ‘hesitancy’.12 Vaccine hesitancy thus reflects the client’s disposition towards vaccination as opposed to health system factors which impede vaccine uptake. Consequently, vaccine hesitancy shifts focus from the well-researched ‘supply’ side of vaccination to the relatively understudied ‘demand’ side of vaccination, exploring people’s willingness to accept vaccination for themselves or their children when supply and access are available. The extreme expression of vaccine hesitancy; vaccine refusal, is as old as the advent of vaccination itself.9 14 15 Evidence suggests that it has become more pronounced on the global vaccination landscape in recent years, aided among other things by the increasing advancement in Information and Communication Technologies.3 14

Many of the countries in the world contend with vaccine hesitancy, with well over 90% of the 194 member states of the WHO reporting it over 3 years as against less than the 10% that reported ‘no hesitancy’.16 The 3 year (2015 to 2017) analysis of WHO/UNICEF member state Joint Reporting Form by Sarah Lane and her team also revealed that vaccine hesitancy is present in all the six WHO regions, and it cuts across all the four categories of country income levels as classified by the WHO. These are: low, lower middle, upper middle and high income category.16 On country level, vaccine hesitancy has been identified in urban and rural dwellers,17 as well as among people of low literacy and those of high literacy18 19 howbeit for different reasons which are beyond the scope of this review protocol to elucidate. There are documented evidence that shows that vaccine hesitancy is present among adherents of the two major religions of the world20 and is not limited to either gender.21 22 Also, notable is the fact that vaccine hesitancy may have an inverse relationship with vaccine confidence, the lack of which may be regarded as one of the main determinants of vaccine hesitancy; covering issues of trust. When confidence is low or lacking, there is the tendency to be hesitant, delay or outrightly refuse vaccination.23

Determinants of vaccine hesitancy

Determinants of vaccine hesitancy can also be referred to as factors, reasons or causes of vaccine hesitancy. According to the WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization Working Group on vaccine hesitancy report of 2014,24 there are myriads of factors that influences the vaccine decision-making process. This is not surprising given its complex and context specific nature. They proffered two models of vaccine hesitancy determinants; the 3C model which is a succinct, easy-to-grasp model comprising of three determinants of vaccine hesitancy all starting with the letter ‘C’, and the more detailed, Working Group Determinants of Vaccine Hesitancy Matrix.12 24 25

In the 3C model, the determinants of vaccine hesitancy are identified as: confidence, which covers issues of trust, not only in safety and effectiveness of vaccines, but also in the competence of the healthcare professionals that administer them and the healthcare systems that delivers them, as well as in the motives of the policymakers who proposes them; convenience involves the ease or otherwise at which the vaccines and related services are accessed, their affordability and the willingness of the individuals to pay and complacency, which occurs when the need to vaccinate is low because the perceived risk of vaccine preventable diseases is deemed to be low. Complacency is particularly heightened in situations where other competing health or life responsibilities are present. These tend to dwarf the need for vaccination which is seen as a preventive measure against diseases, many of which are no longer common or seen as life-threatening, ironically, due to the successes of previous vaccination endeavours.12 24

In recent years, additional two ‘Cs’ have been proposed to expand the ‘3C’ model to a ‘5C’ model. These are rational calculation in which individuals with no strongly defined vaccination attitude embark on an intensive search for information, and depending on their findings, assess the risk of vaccination and make a decision (usually a subjective one) either to vaccinate or not to vaccinate and collective responsibility, on the other hand is implied when individuals or subgroups makes vaccine decisions based on their sense of social responsibility. Such may decide to vaccinate themselves to protect others. For example, pregnant women deciding to take pertussis vaccines based on their understanding that the protection it offers is not for themselves but for their unborn babies.13 26 27

The second model, the Working Group Determinants of Vaccine Hesitancy Matrix is more complex and detailed than the 3C model as earlier mentioned, it broadly groups the determinants under three categories. The first is contextual influences, the second, individual and group influences and the third, vaccine and vaccination-specific issues. Each of these categories has a number of factors listed under them that gives more details about the determinant and its scope.25 Knowing the determinants of vaccine hesitancy in a particular context and setting allows for targeted interventions to be developed purposely to combat its effect in that particular context and setting; as not all intervention works in all settings at all times and for all vaccines. Most of the interventions to mitigate against vaccine hesitancy and its effects have been designed and tested in high-income countries (HICs), with precious little documented in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Effects of vaccine hesitancy

The effects of vaccine hesitancy, that is, the delay or refusal of vaccination for one’s self or ones’ dependant(s) despite the availability and offer of such services can be grave and far-reaching. Vaccine hesitancy is known to have a negative effect on vaccine demand, which in turn affects vaccine uptake and consequently the level of coverage needed to contain outbreaks and maintain control of vaccine preventable diseases. Ultimately, this undermines the effectiveness and successes of immunisation programmes.9

Vaccine hesitancy does not only pose a danger to the hesitant or vaccine-refusing individuals and/or their dependants, but also to the larger society. Vaccine hesitancy reduces ‘herd immunity’, that is, the level at which immunisation coverage is to be maintained if protection is to be offered to those too young (for example, neonates) or too sick (the immunocompromised) to be immunised.28 These subgroup of people depend on the immunisation of other people in their community to protect them from contacting some vaccine preventable diseases. The level of coverage required for herd immunity in a community to prevent an outbreak of measles is estimated at 95%. If there is a reduction in this level for a sustained period of time in a community, an outbreak measles is imminent in such a community.

Controversies based on quasi ‘scientific’ claims such as the one ignited by the infamous Wakefield study conducted in the UK, which suggested a direct link between the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism, resulted in widespread vaccine hesitancy and consequent negative effects. One of such effects is the erosion of confidence in the safety of vaccines, particularly the MMR vaccine, leading to marked decrease in vaccination levels and outbreaks of measles in the UK,29 some parts of Europe such as Austria, Germany and France13 and the USA.30 Another unfortunate example of the effect of vaccine hesitancy is demonstrated in the fivefold increase in the incidence of polio cases in Nigeria between 2002 to 2006. This was caused by the boycott of the oral polio vaccine, due to controversies emanating from unfounded rumours and distrust in the government.26

A lot of countries battle with the effects of vaccine hesitancy, the global influence of which prompted the WHO to recommend that it or its proxies should be constantly monitored. This necessitates the development of tools to detect and measure vaccine hesitancy.12

Measures of vaccine hesitancy

The menace of vaccine hesitancy and its attendant undesirable effects are a threat to public health globally. Its complex and context specific nature, and variability across time, place and vaccines makes its detection and measure somewhat challenging. There had been several efforts in recent past to develop tools for the detection and measures of vaccine hesitancy, such as Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines Survey,31 Vaccine Confidence Scale,32 33 Global Vaccine Confidence Index19 and Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS).34 Most were developed for use in HIC, and some, like the VHS has been validated and used in such context and settings.34 While acknowledging the work of Wallace et al,35 who recently developed and validated a tool; the Caregiver Vaccine Acceptance Scale in Ghana, an LMIC in sub-Saharan Africa, there is, nevertheless a dearth of such context specific tools to measure vaccine hesitancy in many other sub-Saharan LMIC context and settings. Hence there is a need for deliberate and concerted effort to fill this existing knowledge gap. As imperative this need is; care must be taken in executing this mandate to ensure that such generated tools are not just context-specific and valid, but can also provide a basis for data comparison with, and possible integration with those generated in other parts of the world. This can only be possible if similar templates are adapted and used in the development of such tools. This seems to be an implicit rationale behind the SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy’s’ recommendation #1 in their full report of 2014 to WHO member states. The recommendation states that member states should ‘incorporate a plan to measure and address vaccine hesitancy into their country’s immunisation programme as part of good programme practices; the compendium of vaccine hesitancy survey questions may help; use of questions from the compendium facilitates inter-country comparisons, though the survey questions still remain to be validated throughout different settings’.24 This is exemplified in the effort of Wallace and his team,35 and is the main thrust of the research project which the scoping review subsequent to this protocol aims to address. The crux of the project is to develop a context-specific validated tool in a sub-Saharan LMIC setting based on the compendium of vaccine hesitancy survey questions developed by Larson and her team in 201536 commissioned by the WHO. The use of the compendium questions is expected to facilitate inter-country comparisons when validated in different settings as stated in the recommendation.

Methods and analysis

The use of scoping reviews, especially in health and related fields, has steadily been on the rise since 2012.37 38 Scoping reviews are used to identify research gaps, map key concepts and identify main sources of evidence available in a particular area of research.39 40 A scoping review is particularly useful when the area of research is a complex and heterogeneous one,40 such as vaccine hesitancy. The complex and contextual nature of vaccine hesitancy, and its variation across time, place and vaccines makes scoping review an ideal tool for its investigation. Also, the usability of scoping reviews to capture the breadth of evidence available on a particular area of research is in alignment with the aim of this scoping review. The aim of the scoping review subsequent to this protocol is to give a broad overview of currently available vaccine hesitancy measuring tools, and present a summary of their nature, and similarities and differences. In keeping with this aim, no empirical evaluation of the tools will be conducted. However, variations in the target groups of the different tools and the types of scales used will be highlighted in the data extraction and discussion sections of the final review.

The scoping review will use the Arksey and O’Malley framework for conducting scoping reviews.39 It will incorporate suggested improvements and recommendations by other authors such as Levac,41 Pham37 and the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) manual for review authors42 where appropriate. The JBI’s manual for review authors stipulates the use of an a-priori protocol for scoping reviews, it also recommends that the inclusion and exclusion criteria for such reviews should clearly relate to the objectives and research questions of such reviews. This protocol is in compliance with this stipulation, and the scoping review will adopt the recommendations in the process of its conduct. The mandatory five stages of the six stage steps of the Arksey and O’Malley framework will be utilised in the conduct of this scoping review, with the optional sixth stage not included. The six stages are:

Identifying a research question;

Identifying relevant studies;

Study selection;

Charting the data;

Collating, summarising and reporting the result;

Consultation exercise (optional step).

The sixth stage, the consultation stage, is an optional stage, though Arksey and O’Malley alluded to its inclusion enhancing their scoping review.39 The objective of this particular scoping review does not require a consultation stage.

Stage 1: identifying a research question

The research question for the scoping review is an off-shoot of the broader research question for the project of which the scoping review forms part of the evidence synthesis phase. The research question is clearly articulated and focused as recommended by Levac and the JBI’s manual for review authors,40 41 and the scope of the review is indicated in the question. The review question is: What vaccine hesitancy measuring tools are currently available? The phrase ‘currently available’ for the purpose of this scoping review refers to tools published in peer-reviewed journals available in the public domain from the year 2010 to date. This period includes the first 9 years of the decade of vaccines which spans from 2011 to 2020.8 Most of the tools in use were developed within this time frame, the few that might be before this period would have had their essence captured in their successors, as using an existing tool as the template for the development of a new one is a consistent method of tool development. This further clarification of the research question will also help in the development of an effective search strategy, and aid in the selection of the inclusion and exclusion criteria of retrieved records.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Several bibliographic databases of peer-reviewed journals will be searched, these will include, but will not be limited to; MEDLINE (PubMed), Web of Science and Scopus. The three-step search strategy recommended by the JBI manual for review authors42 will be carried out in this stage. The first step includes the use of broad search terms to interrogate at least two electronic databases to retrieve relevant articles. Table 1 shows the proposed search strategy to be used to search MEDLINE. This strategy will be tailored for the other databases. The title and abstract of selected articles from this initial broad search will be scanned for keywords and index terms used to describe the articles. In the second step, the keywords and index terms identified in the first step will be used to develop comprehensive search strategies (search strings) using controlled vocabulary and text words. The focused search strategy, reflective of the research question, will include the use of major keywords such as tools, surveys, scales, interviews and questionnaires in conjunction with the main search term ‘vaccine hesitancy’ and its variants. The search strategy will be tailored to the specifications of each of databases searched. The third and final step will include the ‘hand-searching’ of selected relevant records to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant and available literature. Two or more authors including a seasoned evidence synthesis researcher will be involved in this three-step search for relevant records, this process ensures the optimisation of the search strategy, and will lay a solid foundation for the determination of the inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as the subsequent stages.

Table 1.

Proposed search strategy to search MEDLINE (PubMed)

| Search terms | |

| #1 | (Vaccination Refusal) OR (Vaccine refusal) OR (Anti Vaccination Movement) OR (Vaccine hesitant) OR (vaccination hesitant) OR (Vaccine hesitancy) OR (vaccination hesitancy) OR (immunization hesitancy) OR (immunization hesitant) OR (immunization refusal) OR (immunisation hesitancy) OR (immunisation hesitant) OR (immunisation refusal) OR (vaccine avoidance) OR (vaccination avoidance) OR (vaccine resistance) OR (vaccination resistance) OR (immunization avoidance) OR (immunization resistance) OR (vaccine waiver) OR (mandatory vaccination) |

| #2 | “Pro-vaccination” OR “Vaccination acceptance” OR “vaccine acceptance” OR “Immunization acceptance” OR “Pro-vaccine” OR “Vaccine confidence” OR “Vaccination confidence” |

| #3 | #1 OR #2 |

| #4 | “measurement tools” OR Surveys OR Questionnaire OR Questionnaires OR Interviews OR tool OR tools OR measure OR measures OR measurements OR survey OR interview OR scales OR scale OR index |

| #5 | #3 AND #4 |

A preliminary search in PubMed was conducted in July 2019, using an earlier version of the search strategy shown in table 1. During the peer review process additional search terms were included, and the updated search strategy tested in PubMed in October 2019. The expanded search strategy (tailored to each electronic database) will be used to conduct a comprehensive search of the literature for the scoping review in January 2020 to February 2020.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All relevant studies recovered from the comprehensive search irrespective of study design, country of origin, purpose, vaccines and target populace (eg, population subsets of all demographic strata) covered will be included. Though the search strategy will be filtered to focus on studies available from the year 2010 as earlier indicated, it will also be expanded to include relevant studies that may be available before that time period, and any retrieved record will be reported. Efforts will be made to contact authors of relevant articles whose titles and abstracts meet the inclusion criterial, but whose full-text is not available in the public domain, via email.

Studies that are irrelevant, not published in English, do not include any form of measurement tools, or with tools not measuring vaccine hesitancy will be excluded.

Stage 3: study selection

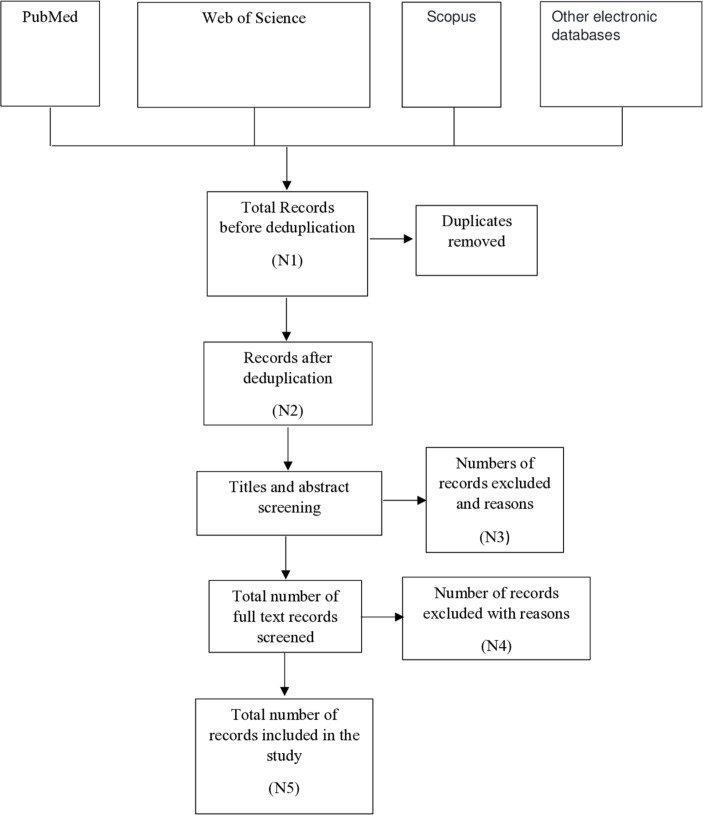

The three-step search strategy will inform the selection of studies to be included in the scoping review. All studies that meet the inclusion criteria will be imported into a reference management package (EndNote). The total number of relevant studies retrieved from the first step of the search will be recorded, as will the total number of studies retrieved from each source of information in the second step. The records will be de-duplicated and the number of duplicates removed recorded. The number of studies excluded after screening of titles, abstracts and full-texts will be recorded, as will the reasons for exclusion. This information will be presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram, a schematic draft of which is presented as figure 1 as recommended in the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews extension checklist.43

Figure 1.

PreferredReporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Stage 4: charting the data

A data charting form that will provide a logical summary of information extracted from each full-text article included in the study will be developed prior to the commencement of the scoping review and will be updated as necessary as the study progresses.42 The data charting form will be designed to extract information relevant to the review question and objectives, and will include, but may not be limited to: title, authors, year of publication, WHO region, country where study was conducted, type of tool, target population, vaccines investigated, domain investigated, number of constructs and total number of items. Data charting will be carried out independently in duplicate by two authors including an evidence synthesis researcher, and as with the preceding stages, other authors will be consulted to resolve differing opinions and to provide supervisory oversight. Below is the tentative list of fields to be completed in the data charting form:

First author, Title, Journal name, Year of publication, Name of measure/tool, Study type, Country, WHO region, World Bank economic classification, Target population, Vaccine(s) investigated, Total number of items, Subscales, Construct/or domains investigated, Method of data collection, Validation tests, Item generation process, Study limitations, Other important information.

Stage 5: collating, summarising and reporting the results

Information from data extracted from included studies will be collated, and quantitative results presented using descriptive statistics such as percentages, tables, charts and flow diagrams as appropriate, while the qualitative results will be reported thematically. This will be followed by an informed discussion based on careful consideration of the results in keeping with the purpose and objective of the review. No meta-analysis is planned for the review, neither will the quality of evidence of included studies be assessed as the purpose of the scoping review is to give a descriptive overview of currently available vaccine hesitancy measuring tools in the literature, and present a summary of their nature, similarities and differences. Therefore, the findings of the review will be reported as described above, and no empirical evaluation of the tools will be conducted in keeping with this aim of the review.

Stage 6: consultation exercise (optional step)

A consultation exercise is not intended for this review as its relevance to the review question and objectives is negligible. Therefore, none will be conducted.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval is not a requirement for the review. All data will be obtained from publicly available documents, and no primary data will be generated. The scoping review forms part of the evidence synthesis phase of a doctoral research project that has obtained ethics approval from the Stellenbosch University Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number S19/01/014 (PhD)).

The review will be presented at conferences and other relevant and appropriate platforms. It will also be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the critical review and technical editing of the manuscript provided by Dr. A.B. Wiyeh.

Footnotes

Twitter: @CharlesShey

Contributors: EOO led the conceptualisation, design and drafted the protocol. EDP and CSW developed the search strategy and EDP conducted the preliminary searches; HM and CSW provided supervisory overview and feedback on the methodology and the manuscript. This team of four authors give their approval to the publishing of this protocol manuscript.

Funding: The work reported herein was made possible through funding by the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) through its Division of Research Capacity Development under the SAMRC Internship Scholarship Programme from funding received from the South African National Treasury. The content hereof is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the SAMRC or the funders.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ansong D, Tawfik D, Williams EA, et al. Suboptimal vaccination rates in rural Ghana despite positive caregiver attitudes towards vaccination. J Vaccines Immun 2014;2:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ehreth J. The global value of vaccination. Vaccine 2003;21:596–600. 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00623-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burnett RJ, Larson HJ, Moloi MH, et al. Addressing public Questioning and concerns about vaccination in South Africa: a guide for healthcare workers. Vaccine 2012;30:C72–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization Who vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system. 2004 global summary. World health organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burton A, et al. Who and UNICEF estimates of national infant immunization coverage: methods and processes. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:535–41. 10.2471/BLT.08.053819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO Global immunization coverage sustained in the past five years. Available: https://www.who.int/immunization/newsroom/press/immunization_coverage_july_2016/en/ [Accessed 27 Jun 2019].

- 7. Succi rC de M. vaccine refusal – what we need to know. J Pediatr 2018;94:574–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Global vaccine action plan. Vaccine 2013;31:B5–31. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, et al. Vaccine hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013;9:1763–73. 10.4161/hv.24657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bloom BR, Marcuse E, Mnookin S. Addressing vaccine hesitancy. Science 2014;344:339 10.1126/science.1254834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dubé E. Addressing vaccine hesitancy: the crucial role of healthcare providers. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017;23:279–80. 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015;33:4161–4. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Betsch C, Böhm R, Chapman GB. Using behavioral insights to increase vaccination policy effectiveness. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2015;2:61–73. 10.1177/2372732215600716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rosselli R, Martini M, Bragazzi NL. The old and the new: vaccine hesitancy in the era of the web 2.0. challenges and opportunities. J Prev Med Hyg 2016;57:E47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bloom DE. The value of vaccination. Adv Exp Med Biol 2011;678:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lane S, MacDonald NE, Marti M, et al. Vaccine hesitancy around the globe: analysis of three years of WHO/UNICEF joint reporting form data-2015–2017. Vaccine 2018;36:3861–7. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Siddiqui M, Salmon DA, Omer SB. Epidemiology of vaccine hesitancy in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013;9:2643–8. 10.4161/hv.27243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dasgupta P. Vaccine Hesitancy for childhood vaccinations in slum areas of Siliguri, India. Indian J Public Health 2017;61:199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Larson HJ, de Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z, et al. The state of vaccine confidence 2016: global insights through a 67-Country survey. EBioMedicine 2016;12:295–301. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Njeru I, Ajack Y, Muitherero C, et al. Did the call for boycott by the Catholic bishops affect the polio vaccination coverage in Kenya in 2015 ? A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J 2016;24:1–9. 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.120.8986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zewdie A, Letebo M, Mekonnen T. Reasons for defaulting from childhood immunization program: a qualitative study from Hadiya zone, southern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1–9. 10.1186/s12889-016-3904-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ozawa S, Wonodi C, Babalola O, et al. Using best-worst scaling to RANK factors affecting vaccination demand in northern Nigeria. Vaccine 2017;35:6429–37. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Orenstein WA, Gellin BG, Beigi RH, et al. Assessing the state of vaccine confidence in the United States: recommendations from the National vaccine Advisory Committee. Public Health Rep 2015;130:573–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. WHO Report of the SAGE Working group on vaccine Hesitancy, 2014. Available: https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WORKING_GROUP_vaccine_hesitancy_final.pdf [Accessed 28 Jun 2019].

- 25. Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, et al. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine 2014;32:2150–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cooper S, Betsch C, Sambala EZ, et al. Vaccine hesitancy – a potential threat to the achievements of vaccination programmes in Africa. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018;14:2355–7. 10.1080/21645515.2018.1460987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Betsch C, Schmid P, Heinemeier D, et al. Beyond confidence: development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLoS One 2018;13:e0208601 10.1371/journal.pone.0208601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Verelst F, Kessels R, Delva W, et al. Drivers of vaccine decision-making in South Africa: a discrete choice experiment. Vaccine 2019;37:2079–89. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.02.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Keenan A, Ghebrehewet S, Vivancos R, et al. Measles outbreaks in the UK, is it when and where, rather than if? A database cohort study of childhood population susceptibility in Liverpool, UK. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014106 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Callender D. Vaccine hesitancy: more than a movement. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016;12:2464–8. 10.1080/21645515.2016.1178434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Taylor JA, et al. Development of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents. Hum Vaccin 2011;7:419–25. 10.4161/hv.7.4.14120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gilkey MB, Magnus BE, Reiter PL, et al. The vaccination confidence scale: a brief measure of parents' vaccination beliefs. Vaccine 2014;32:6259–65. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gilkey MB, Reiter PL, Magnus BE, et al. Validation of the vaccination confidence scale: a brief measure to identify parents at risk for refusing adolescent vaccines. Acad Pediatr 2016;16:42–9. 10.1016/j.acap.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Dube E, et al. The vaccine hesitancy scale: psychometric properties and validation. Vaccine 2018;36:660–7. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wallace AS, Wannemuehler K, Bonsu G, et al. Development of a valid and reliable scale to assess parents’ beliefs and attitudes about childhood vaccines and their association with vaccination uptake and delay in Ghana. Vaccine 2019;37:848–56. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.12.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, et al. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool. Vaccine 2015;33:4165–75. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, et al. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods 2014;5:371–85. 10.1002/jrsm.1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:1–10. 10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stenberg M, Mangrio E, Bengtsson M, et al. Formative peer assessment in healthcare education programmes: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 2018;8:e025055 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci 2010;5 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. The Joanna Briggs Institute Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 edition/supplement Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. Clim Chang 2013 - Phys Sci Basis 2015:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.