Abstract

Objective

Recent studies into the factorial structure of the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) have shown that it was best represented by a single substantive factor when method effects associated with negatively worded (NW) items are considered. The purpose of the present study was to examine the presence of method effects, and their relationships with demographic covariates, associated with positively worded (PW) and/or NW items.

Design

A cross-sectional, observational study to compare a comprehensive set of confirmatory factor models, including method effects associated with PW and/or NW items with GHQ-12 responses.

Setting

Representative sample of all employees living in Catalonia (Spain).

Participants

3050 participants (44.6% women) who responded the Second Catalonian Survey of Working Conditions.

Results

A confirmatory factor analysis showed that the best fitting model was a unidimensional model with two additional uncorrelated method factors associated with PW and NW items. Furthermore, structural equation modelling (SEM) revealed that method effects were differentially related to both the sex and age of the respondents.

Conclusion

Individual differences related to sex and age can help to identify respondents who are prone to answering PW and NW items differently. Consequently, it is desirable that both the constructs of interest as well as the effects of method factors are considered in SEM models as a means of avoiding the drawing of inaccurate conclusions about the relationships between the substantive factors.

Keywords: psychological health, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ–12), method effects, item wording effects, confirmatory factor analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Sampling quality: a random and large representative sample of workers and face-to-face administration by professional interviewers.

Comparison of confirmatory models for positively worded (PW) and/or negatively worded (NW) items and the use of two different parameterisations.

There are no previous studies regarding the demographic correlates of wording effects on the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire.

The different response scale used for the NW items and the PW items in the questionnaire could be a confounding variable.

The results might not be generalised to other specific populations, for example, adolescents and elderly retired people.

Introduction

Originally developed by Goldberg,1 the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) has been widely used as a screening instrument for measuring General Psychological Health (GPH) in both community and non-psychiatric clinical settings.2 The shortest 12-item version (GHQ-12) is the most popular and has been employed on different settings and in several countries, as well as part of multiple major national health, social well-being and occupational surveys, achieving results which underline the fact that it is highly reliable and valid.3–11

Despite its broad application, the factor structure underlying the responses to the GHQ-12 remains a controversial issue. In this sense, although the GHQ-12 was originally developed as a unidimensional scale, this one-factor latent structure has found little empirical support and some alternative multidimensional models have been proposed as more appropriate. Thus, the one with the most empirical support is the three-factor model proposed by Graetz.5 12–22 It is important to note that the six positively worded (PW) items make up the first factor, whereas the other two factors are made up of the six negatively worded (NW) items (see figure 1, model 8). On the other hand, the bidimensional model, where the 6 NW and the 6 PW items in the GHQ-12 are grouped into two factors, has also obtained wide support, especially in studies based on exploratory factor analysis.5 10 23–28 The arguments against these models and in favour of the unidimensional solution are the high correlations between the factors13 and the low discriminant validity of the factor scores derived from these models.16 29 30

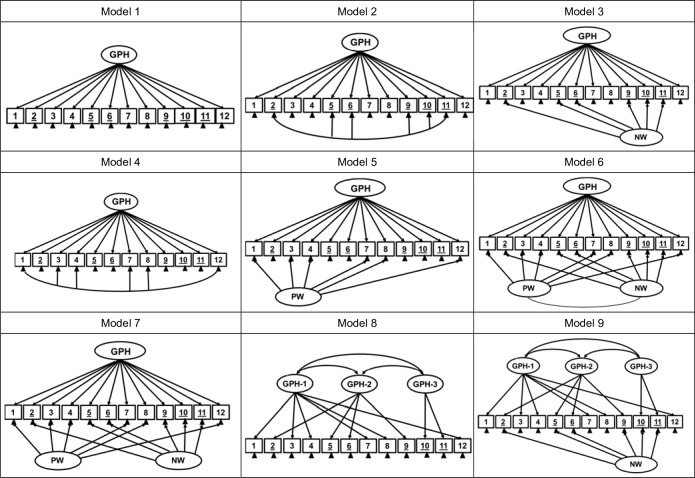

Figure 1.

Competing models tested for the 12-item General Health Questionnaire. Underlined numbers identify negatively worded items. GPH: General Psychological Health; NW: method factor associated with negatively worded items; PW: method factor associated with positively worded items.

As Hankins31 pointed out, multifactor models may just be the resulting artefact of the inclusion of PW and NW items in the questionnaire, and so the controversy about the factorial structure of the GHQ-12 might relate to the effect of item wording on subjects’ response patterns as part of a more general category called ‘method’.32 33 Hankins31 found that, after modelling the wording effects for the NW items, the unidimensional model fitted better than both the two-factor model (NW vs PW items) and Graetz’s three-factor model. Other studies have called into question the substantive meaning of the GHQ-12 multifactor solutions, suggesting that they might just be an artefact due to the wording effects associated with NW items.29 30 34–40 See Molina et al 36 for a deeper review about the dimensionality of GHQ-12.

Some studies about other instruments, however, suggested considering the wording effects not only for the NW items but also for the PW items.41 42 Regarding GHQ-12, only a recent meta-analysis modelled the presence of method effects for NW and PW items concluding that positively keyed items explained incremental variance beyond a general mental health factor.43

Therefore, another source of variability in the results about the factor structure of the GHQ-12 could come from the statistical control of method biases, which has been mainly achieved through the correlated traits–correlated methods (CTCM) and the correlated traits–correlated uniquenesses (CTCU) confirmatory factor analysis models. Both procedures have been used in GHQ-12, to deal with method effects applying the CTCM model,30 44 the CTCU model29 31 39 40 or both CTCM and CTCU models.34–37

To date, we have not found any study about GHQ-12 that analyse the wording effects associated with either PW items alone, or with NW and PW items simultaneously, comparing both CTCU and CTCM models. There are several multivariate statistical models for analysing method effect, and among them the CFA-based approaches are the most popular ones,45 in particular the CFA with CTCM (CFA-CTCM) and the CFA with CTCU (CFA-CTCU). On the one hand, the CTCM model specifies that indicators’ variance can be explained by a linear combination of trait, method and error effects,46 with trait and method effects specified as latent variables. The CTCM model, when methods are specified independent (uncorrelated), directly translates into the well-known bifactor model.47 48 On the other hand, the CTCU model specifies trait factors while method effects are modelled correlating the uniqueness of items (indicators) sharing a common method.49 Both CTCM and CTCU models have strengths and shortcomings and therefore are usually employed simultaneously.50 This work extends the previous work by Molina et al,36 which compares the fit of the unidimensional model, the multifactor models and the CTCM and CTCU unidimensional models with method effects for only the NW items.

To clarify, figure 1 (models 1 to 9) shows the nine CFA models estimated to test the potential method effects associated with either the PW or the NW or both. Model 1 is a one-factor model of general health. This model also works as a baseline model against which to compare other more complex models. Models 2 and 3 are the CTCU and CTCM models that include method effects for the NW items. These were the best fitting models in Molina et al 36 Models 4 and 5 are the CTCU and CTCM models including method effects for the PW items. Model 6 is the CTCM model including method factors for both the NW and PW items (a CTCU model with method effects for both PW and NW items was not estimated because it is not identified). Model 7 is a bifactor model with a general trait factor of general health and two method factors associated to NW and PW items. The three factors are independent (uncorrelated). Additionally, considering the best fitting multidimensional model in Tomás, Gutiérrez and Sancho51 based on the results by Graetz,12 models 8 and 9 were also tested. Model 8 posited three substantive dimensions: social dysfunction, anxiety and depression and loss of confidence. Model 9 included an additional method factor associated to NW items. Models considering a method factor associated to PW items made no sense as all PW items were indicators of social dysfunction.

As stressed by Marsh et al,52 it becomes necessary to consider this comprehensive set of competing models to determine the relative importance and substantive nature of the method effects.

Finally, there has been some research carried out on the demographic correlates of method effects, such as sex,53–57 age55 58 or educational level.41 59 With respect to the GHQ-12, to date, we have not found any studies that analyse demographic correlates of method effects.

Building on the previous studies, the first aim of this study was to overcome the limitation pointed out in Molina et al 36 and examine method effects associated with both PW and NW items. The second aim was to further understand the meaning of the method factors; therefore, we evaluated the relationships between the method factors and three covariates (ie, sex, age, and educational level) in the framework of a structural equation modelling (SEM).

Method

Participants

The data used in this study came from the Second Catalonian Survey of Working Conditions60 and were based on a representative random sample of all employees living in Catalonia (Spain). Data were collected between September and November 2010 by professional interviewers in private households. The sample comprised a total of 3050 participants who responded to the GHQ-12 included in the survey. Main sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Main sociodemographic characteristics

| Mean (SD) | n (%) | Range | |

| Gender | |||

| Women | 1361 (44.6) | ||

| Age | 40.46 (11.19) | 17–82 | |

| Education | |||

| Incomplete primary studies | 90 (3.0) | ||

| Primary studies | 541 (17.9) | ||

| Secondary studies: first stage | 637 (21.0) | ||

| Associate degree | 763 (25.2) | ||

| High school | 598 (19.8 | ||

| Graduate studies | 359 (11.9) | ||

| Postgraduate studies | 39 (1.3) |

Public involvement

Respondents were not involved in any stage of the design of the study and were only requested to respond the survey. In the selected households, interviewers identified themselves personally and informed that this was an official survey about the working conditions of employed Catalonian people commissioned by the Catalonian Government Work Department.

Results were published on the Catalonian Government Work Department website60 and are available at https://treball.gencat.cat/ca/ambits/seguretat_i_salut_laboral/publicacions/estadistiques_estudis/ci/ii_ecct/treballadors/

Measures

The GHQ-12 is a self-report scale that contains 6 PW items (eg, ‘Have you been able to face up to problems?’) and 6 NW items (eg, ‘Have you been losing confidence in yourself?’). The GHQ-12 was validated in Spain by Lobo and Muñoz.61 Table 2 shows the statements of these items in the same order as they were presented in the survey. It must be noted that the GHQ-12 has a different response scale for the PW items (ie, more than usual; same as usual; less than usual and much less than usual) and the NW items (ie, not at all; no more than usual; rather more than usual and much more than usual). Accordingly, the four-point scoring scheme was applied in our study, and so the total scores in the GHQ-12 ranged from 0 to a maximum of 36, with higher scores indicating lower levels of GPH.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, standardised factor loadings from model 7 and correlations between the model 7 factors and the covariates

| Model 7 | |||||

| Item | Mean | SD | GPH | PW | NW |

| Item 1. Able to concentrate | 1.03 | 0.37 | 0.42* | 0.49* | |

| Item 2. Lost sleep over worry | 0.57 | 0.75 | 0.78* | 0.07 | |

| Item 3. Playing a useful part in things | 0.96 | 0.31 | 0.09* | 0.59* | |

| Item 4. Capable of making decisions | 0.96 | 0.30 | 0.14* | 0.70* | |

| Item 5. Constantly under strain | 0.71 | 0.79 | 0.83* | 0.03 | |

| Item 6. Could not overcome difficulties | 0.44 | 0.66 | 0.76* | 0.25* | |

| Item 7. Enjoy day-to-day activities | 1.01 | 0.40 | 0.53* | 0.55* | |

| Item 8. Face up to problems | 0.99 | 0.32 | 0.39* | 0.60* | |

| Item 9. Feeling unhappy and depressed | 0.37 | 0.66 | 0.78* | 0.38* | |

| Item 10. Losing confidence in yourself | 0.19 | 0.48 | 0.53* | 0.70* | |

| Item 11. Thinking of yourself as a worthless person | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.48* | 0.72* | |

| Item 12. Feeling reasonably happy | 0.99 | 0.38 | 0.44* | 0.72* | |

| Relation between the model 7 factors and the socio-demographic variables | |||||

| Sex | 0.13* | −0.08* | −0.02 | ||

| Age | 0.11* | 0.08* | 0.01 | ||

| Educational level | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.06 | ||

*P< 0.05.

GPH, General Health Psychology;NW, negative wording factor; PW, positive wording factor.

For the purposes of exploring the correlates of method effects (ie, item wording effects), we used the following three covariates: (a) sex (0=men and 1=women); (b) age and (c) educational level, which was measured as a self-reported question with seven response graduated categories ranging from incomplete primary studies to postgraduate studies. The educational level was scored as the highest level of education reached.

Statistical analysis

A set of competing confirmatory factor models were estimated using MPlus V.8.3.62 Figure 1 shows the specification of all these CFA models. The goodness-of-fit indices computed were the χ2 statistic; the Comparative Fit Index (CFI); the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with its 90% CI and the Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Values greater than 0.95 for CFI, and lower than 0.06 and 0.08 for RMSEA and SRMR, respectively, are considered to indicate good model fit.

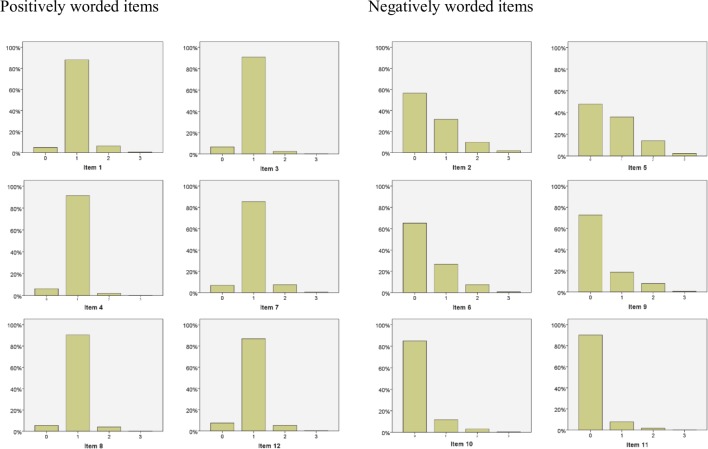

As concerns the estimation of CFA models, most studies into the GHQ-12 factor structure have used maximum likelihood.16 31 35 40 44 This estimation method relies on several assumptions which should be met to be confident about the results obtained. This is the case of the assumption of multivariate normality which implies, first, that the variables are continuous in nature and, second, that the joint distribution of the variables is normal. The first condition is unlikely to be met with the GHQ-12 Likert-type response data; nor is the second if the variables depart markedly from normality as is the case for the responses to the NW items which were heavily positively skewed (see figure 2). An alternative when these conditions are not met is to use the weighted least squares (WLS) estimator,63 which has already been used in some studies about the GHQ-12 factor structure13 18 20 29 and it will be the estimation method used here. Thus, the various CFA models were estimated using diagonally WLS.

Figure 2.

Bar charts of the response distributions for the 12-item General Health Questionnaire. Responses were given on a different four-point response scale for the positively worded items (0=better than usual, 1=same as usual, 2=less than usual, 3=much less than usual) and for the negatively worded items (0=not at all, 1=no more than usual, 2=more than usual, 3=much more than usual).

Finally, correlates of the GHQ-12 factors were evaluated using SEM through the inclusion in the finally selected model of the three covariates considered in this study: sex was treated as categorical, whereas age and educational level were treated as continuous variables.

Results

The goodness-of-fit statistics and indices obtained for the nine models compared here are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Fit indexes for the alternative models of the 12-item General Health Questionnaire

| Models | df | χ2 | CFI | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR |

| Model 1 | 54 | 5378.68 | 0.77 | 0.180 (0.176 to 0.184) | 0.119 |

| Model 2 | 39 | 928.099 | 0.96 | 0.086 (0.082 to 0.091) | 0.049 |

| Model 3 | 48 | 1345.38 | 0.95 | 0.094 (0.090 to 0.059) | 0.061 |

| Model 4 | 39 | 934.690 | 0.96 | 0.087 (0.083 to 0.092) | 0.052 |

| Model 5 | 48 | 1275.28 | 0.95 | 0.092 (0.087 to 0.096) | 0.058 |

| Model 6 | 41 | 497.520 | 0.98 | 0.060 (0.056 to 0.065) | 0.030 |

| Model 7 | 42 | 507.741 | 0.98 | 0.060 (0.056 to 0.065) | 0.030 |

| Model 8 | 51 | 1142.88 | 0.95 | 0.084 (0.080 to 0.088) | 0.054 |

| Model 9 | 45 | 960.388 | 0.96 | 0.082 (0.078 to 0.086) | 0.049 |

Models are specified in figure 1.

CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; SRMR, Standardised Root Mean Square Residual.

Model 1, with a single factor of general health, and model 8, with three substantive factors, had worse fit than the models that include wording effects. That is, a careful look at fit indexes makes clear that the inclusion of method effects always improves model fit. Indeed, both NW and PW method effects are needed to get the best fitting models. These best fitting models were models 6 and 7. Their fit was practically indistinguishable and, given that they only differ in that model 7 is more parsimonious because constrains method factors correlation to zero, it will be retained as the best representation of the observed data.

An in-depth inspection of the parameter estimates in model 7 (see table 2) showed that all factor loadings were statistically significant for the three factors, except for items 2 and 5 in the method factor comprising the NW items.

Finally, a statistical analysis of the relationships between the latent factors in model 7 and the three covariates considered in this study (ie, sex, age and educational level) was performed through a Multiple Indicator Multiple Causes (MIMIC) SEM model in which the effects between the three latent factors in model 7 and the three covariates were freely estimated, the focus being on the relationships between the method factors and the covariates. The model fit was excellent (RMSEA=0.040; RMSEA 90% Confidence interval (CI) = (0.037, 0.049); CFI=0.99; SRMR=0.029). As can be seen in table 2, the relations of age with the method factors were near to 0 and statistically non-significant for NW items, and positive and significant although small with PW items (0.08). Sex was significantly related to the method factor associated with PW items (–0.08), whereas the educational level was not significantly related to method factors. Thus, men and women differ in the way they answer PW items, meaning that men are slightly more likely than women to endorse PW items, and method effects associated with PW items also increased by age.

Discussion

This study focused on the examination of the latent structure underlying the responses to the GHQ-12, considering the role of method effects associated with both, PW and NW items, and using two alternative parameterisations of the CFA measurement models. What should first be noted is that the studies that have included method effects in the measurement model of the GHQ-12 have been more the exception than the rule in previous research into the factor structure of this questionnaire.

According to the results of the present study, we conclude that the GHQ-12 factor structure is best characterised by introducing latent method factors that capture both the method effects associated with NW and PW items (model 7). These results support the conclusion from previous research that the good fit obtained by multidimensional models (mainly the two-factor model and the three-factor Graetz’s model) could simply be explained by the artificial grouping of PW and NW items. However, the interpretation of the latent (method) factors as purely integrating method bias due to wording is not straightforward. It is obvious that NW and PW items share the wording. It is also clear that this three bifactor model (one trait and two method factors) fitted the data best. And finally, there is a lot of empirical evidence on these wording effects. However, it is also relevant to discuss the large loadings of many items on the method factors, being these loadings sometimes larger than their loadings in the trait factor. The general factor explains a 52% of the shared variance, but there are some items that deserve careful attention. For example, items 3 (‘playing useful part in things’) and 4 (‘capable of making decisions’) had very low loadings on the trait factor. If we understand PW method factor as the only method bias, then it follows that these two items are purely method effects, but surely they must share some trait variance. In the same vein, items 10 (‘losing confidence in yourself’) and 11 (‘thinking of yourself as a worthless person’) load very high in the NW method factor and, as a reviewer pointed out, a likely (post-hoc) explanation is that wording bias are still confounded with a confidence/self-image factor. Therefore, the interpretation of these effects as purely method and, accordingly, the interpretation of an overall score for the scale difficult may be compromised.

The second aim of this study was to examine the relationship between the method factors associated with both NW and PW items and three demographic variables, namely sex, age and educational level of the respondents. Regarding the sex, we found a statistically significant, but weak, relationship between PW and sex, so that men were more likely than women to endorse PW items. These results are in line with previous works that, in the context of RSES, have found sex differences in wording effects.56 57 As for the explanatory role of age on method effects, we found that the relationship between age and the NW effect was not statistically significant, which supports previous research using other questionnaires (eg, self-esteem scales,50 Hospital Anxiety & Depression Scale64). Moreover, our results give support to previous studies which had stated that, in older adults, the strongest method effects would be associated with PW items, rather than NW items.55 58

As to the educational level, we found that there was not a significant correlation of this variable on the two method factors. This result supports and extends the evidence obtained in Tomás et al 50 who found that the educational level of the respondents had no effect on the negative method factor using self-esteem questionnaires. This results contradicts previous research on the relationship of the NW factor and the educational level/verbal ability with different questionnaires and samples.41 64–69

Overall, the significant effects of sex and age on trait and method factors point out that women have a worse well-being, but this effect is partly modified by a method effect on the PW items, whereas the results for age suggest that older respondents have worse well-being and this effect is magnified by a method effect on the PW factor. The results on the individual differences related to the demographic variables considered in this study cannot only help to understand the presence of wording method effects but also to identify respondents who are prone to answering PW and NW items differently. In this sense, the relationship that appears as more evident is for the age and sex variables.

Another practical consequence of our study concerns the relationship between the intended measure of the GHQ-12 (ie, the GPH factor) and other constructs of interest. Several studies have shown that method effects can inflate, deflate or have no effect at all on estimates of the relationship between two constructs (see Podsakoff et al 70 for a further review of the effects that method biases have on individual measures and on the covariation between different constructs). Thus, it is desirable that both the constructs of interest as well as the effects of method factors, like PW and NW, are considered in SEM models as a means of controlling these systematic sources of bias, and thus avoiding the drawing of inaccurate conclusions about the relationship between the substantive factors.

Previous research on the GHQ-1231 36 has outlined the asymmetry in the participants’ responses as a function of the wording of the items, as well as the different responses scales for the PW and NW items. This asymmetry in the participants’ responses as a function of the wording of the items is consistent with results from previous research into wording effects for contrastive survey questions.71 The extent to which the presence of method effects is linked to the asymmetric pattern of responses and/or to the different response scales for the PW and NW items in the GHQ-12 should be examined in future research.

Comparing the current work with previous studies into the factorial structure of the GHQ-12, to our knowledge, this is the first study that tests a comprehensive set of models including method effects associated with both PW and NW items and also explores some demographic correlates of these method effects. Another strength of this work was the fact that it used a large representative sample of workers, but the results might not be generalised to other specific populations, for example, adolescents and elderly retired people.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @jmlosilla, @VivesJ_Research

Contributors: All authors meet the criteria recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data. MFR and JGM: drafted the article. JV and JML: critically revised the draft for important intellectual content. JMT: worked in the statistical analysis and interpretation of data. All authors agreed on the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Grant PGC2018-100675-B-I00, Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (Spain). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclaimer: All authors have agreed to authorship in the indicated order. All authors declare that this paper is an original unpublished work and it is not being submitted elsewhere. All authors do not have any financial interests that might be interpreted as influencing the research, and APA ethical standard were followed in the conduct of the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The research was not submitted to approval by an institutional review board since this is not a requirement at our universities for this type of study. Ethics approval was not sought for this study since this was a secondary analysis of anonymised data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Goldberg DP. The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. London: Oxford University Press, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldberg DP, Williams P. A user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, United Kingdom: NFER-Nelson, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhui K, Bhugra D, Goldberg D. Cross-cultural validity of the Amritsar depression inventory and the general health questionnaire amongst English and Punjabi primary care attenders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2000;35:248–54. 10.1007/s001270050235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daradkeh TK, Ghubash R, el-Rufaie OE. Reliability, validity, and factor structure of the Arabic version of the 12-Item general health questionnaire. Psychol Rep 2001;89:85–94. 10.2466/PR0.89.5.85-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gelaye B, Tadesse MG, Lohsoonthorn V, et al. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the general health questionnaire as a screening tool for anxiety and depressive symptoms in a multi-national study of young adults. J Affect Disord 2015;187:197–202. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med 1997;27:191–7. 10.1017/S0033291796004242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lundin A, Hallgren M, Theobald H, et al. Validity of the 12-item version of the general health questionnaire in detecting depression in the general population. Public Health 2016;136:66–74. 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rocha K, Pérez K, Rodríguez-Sanz M, et al. Propiedades psicométricas y valores normativos del General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) en población general española. Int J Clin Heal Psychol 2011;11:125–39. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sánchez-López MdelP, Dresch V. The 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): reliability, external validity and factor structure in the Spanish population. Psicothema 2008;20:839–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schmitz N, Kruse J, Tress W. Psychometric properties of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) in a German primary care sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999;100:462–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tait RJ, French DJ, Hulse GK. Validity and psychometric properties of the general health questionnaire-12 in young Australian adolescents. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2003;37:374–81. 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01133.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Graetz B. Multidimensional properties of the general health questionnaire. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1991;26:132–8. 10.1007/BF00782952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Campbell A, Knowles S. A confirmatory factor analysis of the GHQ12 using a large Australian sample. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 2007: 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cheung YB. A confirmatory factor analysis of the 12-item general health questionnaire among older people. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;17:739–44. 10.1002/gps.693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. French DJ, Tait RJ. Measurement invariance in the general health questionnaire-12 in young Australian adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004;13:1–7. 10.1007/s00787-004-0345-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gao F, Luo N, Thumboo J, et al. Does the 12-item general health questionnaire contain multiple factors and do we need them? Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:63–7. 10.1186/1477-7525-2-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mäkikangas A, Feldt T, Kinnunen U, et al. The factor structure and factorial invariance of the 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) across time: evidence from two community-based samples. Psychol Assess 2006;18:444–51. 10.1037/1040-3590.18.4.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Padrón A, Galán I, Durbán M, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) in Spanish adolescents. Qual Life Res 2012;21:1291–8. 10.1007/s11136-011-0038-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Penninkilampi-Kerola V, Miettunen J, Ebeling H. A comparative assessment of the factor structures and psychometric properties of the GHQ-12 and the GHQ-20 based on data from a Finnish population-based sample. Scand J Psychol 2006;47:431–40. 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00551.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shevlin M, Adamson G. Alternative factor models and factorial invariance of the GHQ-12: a large sample analysis using confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol Assess 2005;17:231–6. 10.1037/1040-3590.17.2.231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martin CR, Newell RJ. The factor structure of the 12-item general health questionnaire in individuals with facial disfigurement. J Psychosom Res 2005;59:193–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tomás JM, Meléndez JC, Oliver A, et al. Efectos de método en las escalas de Ryff: un estudio en población de personas mayores. Psicológica 2010;31:383–400. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andrich D, van Schoubroeck L. The General Health Questionnaire: a psychometric analysis using latent trait theory. Psychol Med 1989;19:469–85. 10.1017/S0033291700012502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gao W, Stark D, Bennett MI, et al. Using the 12-item general health questionnaire to screen psychological distress from survivorship to end-of-life care: dimensionality and item quality. Psychooncology 2012;21:954–61. 10.1002/pon.1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Glozah FN, Pevalin DJ. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) among Ghanaian adolescents. J Child Adolesc Ment Health 2015;27:53–7. 10.2989/17280583.2015.1007867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kilic C, Rezaki M, Rezaki B, et al. General health questionnaire (GHQ-12 & GHQ-28): psychometric properties and factor structure of the scales in a Turkish primary care sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1997;32:327-31 10.1007/bf00805437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Picardi A, Abeni D, Pasquini P. Assessing psychological distress in patients with skin diseases: reliability, validity and factor structure of the GHQ-12. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol 2001;15:410–7. 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Werneke U, Goldberg DP, Yalcin I, et al. The stability of the factor structure of the general health questionnaire. Psychol Med 2000;30:823–9. 10.1017/S0033291799002287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aguado J, Campbell A, Ascaso C, et al. Examining the factor structure and discriminant validity of the 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) among Spanish postpartum women. Assessment 2012;19:517–25. 10.1177/1073191110388146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ye S. Factor structure of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): the role of wording effects. Pers Individ Dif 2009;46:197–201. 10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hankins M. The factor structure of the twelve item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): the result of negative phrasing? Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2008;4 10.1186/1745-0179-4-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harvey RJ, Billings RS, Nilan KJ. Confirmatory factor analysis of the job diagnostic survey: good news and bad news. J Appl Psychol 1985;70:461–8. 10.1037/0021-9010.70.3.461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith N, Stults DM. Factors defined by negatively keyed items: the results of careless respondents? Appl Psychol Meas 1985;9:367–73. 10.1177/014662168500900405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abubakar A, Fischer R. The factor structure of the 12-Item general health questionnaire in a literate Kenyan population. Stress Health 2012;28:248–54. 10.1002/smi.1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fernandes HM, Vasconcelos-Raposo J. Factorial validity and invariance of the GHQ-12 among clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment 2013;20:219–29. 10.1177/1073191112465768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Molina JG, Rodrigo MF, Losilla J-M, et al. Wording effects and the factor structure of the 12-Item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12). Psychol Assess 2014;26:1031–7. 10.1037/a0036472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Motamed N, Edalatian Zakeri S, Rabiee B, et al. The factor structure of the twelve items general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): a population based study. Appl Res Qual Life 2018;13:303–16. 10.1007/s11482-017-9522-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rey JJ, Abad FJ, Barrada JR, et al. The impact of ambiguous response categories on the factor structure of the GHQ-12. Psychol Assess 2014;26:1021–30. 10.1037/a0036468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Romppel M, Braehler E, Roth M, et al. What is the general health questionnaire-12 assessing? Compr Psychiatry 2013;54:406–13. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith AB, Oluboyede Y, West R, et al. The factor structure of the GHQ-12: the interaction between item phrasing, variance and levels of distress. Qual Life Res 2013;22:145–52. 10.1007/s11136-012-0133-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marsh HW. Negative item bias in ratings scales for preadolescent children: a cognitive-developmental phenomenon. Dev Psychol 1986;22:37–49. 10.1037/0012-1649.22.1.37 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tomás JM, Oliver A. Rosenberg's self‐esteem scale: two factors or method effects. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J 1999;6:84–98. 10.1080/10705519909540120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gnambs T, Staufenbiel T. The structure of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): two meta-analytic factor analyses. Health Psychol Rev 2018;12:179–94. 10.1080/17437199.2018.1426484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang L, Lin W. Wording effects and the dimensionality of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-12). Pers Individ Dif 2011;50:1056–61. 10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wothke W. Models for multitrait-multimethod matrix analysis : Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, Advanced structural equation modeling: issues and techniques. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jöreskog KG. Analyzing psychological data by structural analysis of covariance matrices : Atkinson RC, Krantz DH, Luce RD, et al., Contemporary developments in mathematical psychology. 2 San Francisco: Freeman, 1974: 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Markon KE. Bifactor and hierarchical models: specification, inference, and interpretation. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2019;15:51–69. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reise SP. Invited paper: the rediscovery of Bifactor measurement models. Multivariate Behav Res 2012;47:667–96. 10.1080/00273171.2012.715555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Marsh HW, Bailey M. Confirmatory factor analyses of multitrait-multimethod data: a comparison of alternative models. Appl Psychol Meas 1991;15:47–70. 10.1177/014662169101500106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tomás JM, Oliver A, Galiana L, et al. Explaining method effects associated with negatively worded items in trait and state global and domain-specific self-esteem scales. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J 2013;20:299–313. 10.1080/10705511.2013.769394 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tomás JM, Gutiérrez M, Sancho P. Factorial validity of the general health questionnaire 12 in an Angolan sample. Eur J Psychol Assess 2017;33:116–22. 10.1027/1015-5759/a000278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Marsh HW, Scalas LF, Nagengast B. Longitudinal tests of competing factor structures for the Rosenberg self-esteem scale: traits, ephemeral artifacts, and stable response styles. Psychol Assess 2010;22:366–81. 10.1037/a0019225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. DiStefano C, Motl RW. Self-esteem and method effects associated with negatively worded items: investigating factorial invariance by sex. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J 2009;16:134–46. 10.1080/10705510802565403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gana K, Saada Y, Bailly N, et al. Longitudinal factorial invariance of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale: determining the nature of method effects due to item wording. J Res Pers 2013;47:406–16. 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lindwall M, Barkoukis V, Grano C, et al. Method effects: the problem with negatively versus positively keyed items. J Pers Assess 2012;94:196–204. 10.1080/00223891.2011.645936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Michaelides MP, Zenger M, Koutsogiorgi C, et al. Personality correlates and gender invariance of wording effects in the German version of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Pers Individ Dif 2016;97:13–18. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Urbán R, Szigeti R, Kökönyei G, et al. Global self-esteem and method effects: competing factor structures, longitudinal invariance, and response styles in adolescents. Behav Res Methods 2014;46:488–98. 10.3758/s13428-013-0391-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mullen SP, Gothe NP, McAuley E. Evaluation of the factor structure of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in older adults. Pers Individ Dif 2013;54:153–7. 10.1016/j.paid.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Marsh HW. Positive and negative global self-esteem: a substantively meaningful distinction or artifactors? J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;70:810–9. 10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Catalonian Labor Relations and Quality of Work Department Segunda Encuesta Catalana de Condiciones de Trabajo [Second Catalonian Survey of Working Conditions. Author: Barcelona:, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lobo A, Muñoz PE. Versiones en lengua española validadas : Goldberg D, Williams P, Cuestionario de Salud General GHQ (General Health Questionnaire). Guia para el usuario de las distintas versiones [Guide for the use of the different validated versions in Spanish language. Barcelona, Spain: Editorial Masson, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6th ed Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Browne MW. Asymptotically distribution-free methods for the analysis of covariance structures. Br J Math Stat Psychol 1984;37:62–83. 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1984.tb00789.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wouters E, Booysen FleR, Ponnet K, et al. Wording effects and the factor structure of the hospital anxiety & depression scale in HIV/AIDS patients on antiretroviral treatment in South Africa. PLoS One 2012;7:e34881–7. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bors DA, Vigneau F, Lalande F. Measuring the need for cognition: item polarity, dimensionality, and the relation with ability. Pers Individ Dif 2006;40:819–28. 10.1016/j.paid.2005.09.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Chen YH, Rendina-Gobioff G, Dedrick RF. Factorial invariance of a Chinese self-esteem scale for third and sixth grade students: evaluating method effects associated with the use of positively and negatively worded items. Int J Educ Psychol Assess 2010;6:21–35. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Corwyn RF. The factor structure of global self-esteem among adolescents and adults. J Res Pers 2000;34:357–79. 10.1006/jrpe.2000.2291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rammstedt B, Goldberg LR, Borg I. The measurement equivalence of big-five factor markers for persons with different levels of education. J Res Pers 2010;44:53–61. 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schmitt DP, Allik J. Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in 53 nations: exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol 2005;89:623–42. 10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 2012;63:539–69. 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kamoen N, Holleman B, Mak P, et al. Agree or disagree? cognitive processes in answering contrastive survey questions. Discourse Process 2011;48:355–85. 10.1080/0163853X.2011.578910 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.