Abstract

Objectives

Weaknesses of the nine-hole peg test include high floor effects and a result that might be difficult to interpret. In the twenty-five-hole peg test (TFHPT), the larger number of available pegs allows for the straightforward counting of the number of pegs inserted as the result. The TFHPT provides a comprehensible result and low floor effects. The objective was to assess the test-retest reliability of the TFHPT when testing persons with stroke. A particular focus was placed on the absolute reliability, as quantified by the smallest real difference (SRD). Complementary aims were to investigate possible implications for how the TFHPT should be used and for how the SRD of the TFHPT performance should be expressed.

Design

This study employed a test-retest design including three trials. The pause between trials was approximately 10–120 s.

Participants, setting and outcome measure

Thirty-one participants who had suffered a stroke were recruited from a group designated for constraint-induced movement therapy at outpatient clinics. The TFHPT result was expressed as the number of pegs inserted.

Methods

Absolute reliability was quantified by the SRD, including random and systematic error for a single trial, SRD2.1, and for an average of three trials, SRD2.3. For the SRD measures, the corresponding SRD percentage (SRD%) measure was also reported.

Results

The differences in the number of pegs necessary to detect a change in the TFHPT for SRD2.1 and SRD2.3 were 4.0 and 2.3, respectively. The corresponding SRD% values for SRD2.1 and SRD2.3 were 36.5% and 21.3%, respectively.

Conclusions

The smallest change that can be detected in the TFHPT should be just above two pegs for a test procedure including an average of three trials. The use of an average of three trials compared with a single trial substantially reduces the measurement error.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN registry, reference number ISRCTN24868616.

Keywords: stroke, measurement, reliability, clinical assessment, hand function, twenty-five-hole peg test

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The generalisability of the results may be limited: the participants were selected because they should benefit from constraint-induced movement therapy, and few scored above 20 pegs during the 50 s trial duration.

Among other measures of reliability, the smallest real difference percentage was reported; this is a good measure for comparisons between different tests, scales and populations.

The results are presented with several different reliability measures to offer knowledge about the source of the measurement error.

As the test-retest trials were performed within minutes, possible day-to-day variation was not captured.

The intended practice trial was included as one of three trials in the analyses which appears to have contributed to the learning effect.

Introduction

For a comprehensive upper limb assessment among persons with stroke, it is important to combine a measure of proximal upper limb function with a measure of hand function.1 However, only approximately 25% of studies regarding upper limb interventions include a specific measure of hand function.1 The nine-hole peg test (NHPT) is a common test of hand function focusing on fine manual dexterity, and it is the most common such test used in research.1–3 Two studies of stroke populations investigated the reliability of the NHPT, and there was a large discrepancy in the reliability reported: the smallest real difference percentage (SRD%) 24% vs 52%.2 3 The NHPT has mostly shown moderate to excellent correlations (0.55–0.97) with other tests and self-reports focusing on hand function, including the Action Research Arm Test, the Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function Test and the Stroke Impact Scale (hand function domain).4 5 The exception is the Motor Activity Log, for which low correlations have been reported (0.23–0.33).5

A weakness of the NHPT is that many persons with stroke cannot reach the lower limit; that is, a floor effect arises. Furthermore, if the number of completed pegs is used as an outcome measure, a test with only nine pegs can measure only a narrow range of hand function, resulting in profound ceiling effects.6 Therefore, to widen the scale and avoid ceiling effects, the original NHPT expresses the result as the time needed to complete the test (including inserting and removing all the pegs).2 3 7 8 However, this approach aggravates the floor effects because tests that are not completed during the stipulated time (limits of 60 and 180 s have been used) are excluded.2 3 The maximum time could be prolonged; however, this would be time consuming, mentally strenuous and therefore possibly unethical due to the possibility of a non-completed test after a lengthy attempt. A modified NHPT is used to mitigate the floor effect while avoiding the ceiling effect; in this modified version, the result is expressed as the number of inserted pegs per unit of time (ie, the frequency).9 This modified test includes only peg insertion and not peg removal. It is thus possible also to include tests that were not completed within the stipulated time limit and still measure performance on the same task across the entire range of hand function. However, it may be difficult both to interpret the frequency and to communicate it to other staff members and patients, especially to those suffering from a brain injury. The reliability of this modified test has not been investigated.

In Sweden, a similar peg test, a twenty-five-hole peg test (TFHPT), has been used in clinical practice. The larger number of available pegs makes it straightforward to count the number of pegs inserted during a stipulated time frame of 50 s as the test result. Thus, the TFHPT measures fine manual dexterity on a numerical scale that is easy to comprehend, with low floor effects and presumably reasonable ceiling effects (based on prestudy data). Moreover, compared to the individuals whom the original NHPT can test, individuals with worse hand function can be tested with the TFHPT.2 3 Of the two studies investigating the reliability of the NHPT, the one with the most generous time limit excluded all tests that were not completed in 180 s.3 This limit corresponds to inserting and removing a minimum of 2.5 pegs in 50 s, whereas 0 pegs inserted in 50 s is a valid result with the TFHPT. The TFHPT has not been previously described in the literature, and its reliability has not been investigated. Due to the similarity of the NHPT and the TFHPT, the underlying skill assessed with these tests is most likely the same. However, since the tests have completely different stop criteria—a time limit for the TFHPT vs the insertion of all pegs for the NHPT—equal reliability cannot be taken for granted.7 Thus, if the size of the measurement error related to the TFHPT is shown to be acceptable, this test may be useful in both clinical practice and research.

The overall aim of this study was to assess the test-retest reliability of the TFHPT for persons suffering from stroke. A particular focus was placed on the absolute reliability, as quantified by the smallest real difference (SRD). Complementary aims were to investigate possible implications for how the TFHPT should be used and for how the SRD of the TFHPT performance should be expressed.

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were consecutively recruited in the process of screening patients eligible for inclusion in a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT). The patients were considered for inclusion because they were to undergo constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) at one of the clinics participating in the RCT. The clinics were outpatient rehabilitation clinics in the public healthcare system in Sweden. Data were collected at the clinics. The sample in this study consisted of included and excluded participants in the multicentre RCT. The participants were included if they had one stroke or more registered in the medical record and if TFHPT data were available from three trials before and three trials after the CIMT. Moreover, with regard to the outcome measure, a minimum of one peg and a maximum of 24 pegs inserted was necessary for inclusion. This was to avoid an untrue low measurement error from participants stable at 0 or 25 pegs inserted. These two intervals are wider, a person can be far below the floor or high over the ceiling, so measurements at these intervals should be more stable.

A minimum of 30 participants were included to obtain a sufficient number for a reliability study.10

Procedure and measurements

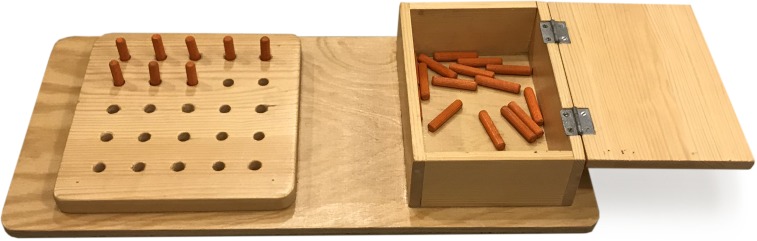

The TFHPT has twenty-five holes and pegs (figure 1). The test used in this study consisted of a rectangular 21×45 cm board with a box containing pegs on one side and an elevated 18×18 cm area with holes on the other side. The holes were 9 mm wide and 18 mm deep, and they were spaced 20 mm apart. The box had a base of 13×18 cm and was 5 cm deep. The pegs were 40 mm long and 8 mm in diameter.

Figure 1.

The twenty-five-hole peg test.

A battery of different tests was administered in this study, including the Fugl-Meyer test11 and the Birgitta Lindmark motor assessment (BL motor assessment).12 13 The TFHPT was administered as the second test. The preceding test, the BL motor assessment, required approximately 30–60 min to administer. The tests were administered in an examination room in which only the participant and the physiotherapist were present. For the TFHPT, three trials were performed with each hand. The participants started with the less-affected hand, followed by the more-affected hand, that is, the hand of investigation in this test-retest study. The pause between trials was approximately 10–120 s. The board was placed at a distance favoured by the participant with the centre row of holes centred towards the navel and the box side oriented towards the tested hand. The starting position was with both hands on the board, and time keeping began on first hand contact with the pegs. We gave participants the following instructions:

I want you to pick up one peg at a time and insert them in the holes of the board.

Use only the right/left hand; you can only use the other hand to steady the board.

You can fill the holes in any order you desire.

We start with a practice trial.

You have 50 s to insert as many pegs as you can. After 50 s, the trial is terminated.

Are you ready? Ready, set, go!

After the practice trial: This was practice; now come the two actual test trials, where the results are recorded. Repeat step 6.

The test-retest reliability of the TFHPT was assessed on two separate occasions, that is, before and after a 2-week training period (the CIMT). The same procedure was used on both of these occasions, and for each participant, all tests were administered by the same physiotherapist. The assessment after the CIMT period was performed as an internal validation.

Two physiotherapists, SE and BL, administered the tests in this study. SE has general experience with persons suffering from stroke and experience administering the original NHPT. BL has extensive experience with persons suffering from stroke, including administering the original NHPT. Background data from medical records were collected by staff at the clinics.

Statistics

All three trials were used in the analyses, although the first trial was introduced to the participants as a practice trial. Analyses of preintervention data and postintervention data were performed separately.

Bland-Altman plots of trials one and two provided a graphic description of the data variability. The mean of trials one and two was plotted against the difference between trials two and one for each subject. Heteroscedasticity (ie, an association between the random error and the magnitude of measurements14) was investigated with pairwise comparisons of trials using Koenker’s15 studentised test which is useful for small samples and skewed data. Heteroscedasticity is indicated by a significant result.

Measurement error can be either random or systematic. In random error, there is no pattern of variability between trials, whereas in systematic error, the measurements vary in a non-random way (ie, the mean values between the trials differ).16 To investigate whether there was a systematic error in test scores, one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to detect potential between trial effects.

Reliability is a term that describes how the measurement result of an instrument is affected by measurement error.6 14 Reliability can be quantified as either relative or absolute.6 Relative reliability refers to the consistency of the positions of measurements relative to those of others within the tested group, and it is quantified using several intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs).16 17 In ICCs, between-subject variability is related to the within-subject variability by a ratio.16 Thus, ICCs are sensitive to the degree of between-subject variability, and with all other things being equal, a more heterogeneous sample (ie, a larger between-subject variability) produces higher ICC values.16 17 The concept of absolute reliability refers to the consistency of measurements within individuals.6 16 Measurement error, quantified as within-subject SD in repeated tests, is a common measure of absolute reliability6 14 16–18 and is called the SE of measurement (SEM). SRD is an extension of the SEM, and it can be seen as the smallest detectable difference, with 95% certainty, using a test instrument on an individual.16

Three separate measures of relative reliability, that is, ICC2.1, ICC2.3 and ICC3.3, including 95% CIs, were calculated. This panel of measures was used to compare the results representative of single and average measures and to obtain an estimate of the influence of systematic error. The first figure in the ICC designation represents the type of ICC model.16 ICC2.1 and ICC2.3 are calculated from a two-way random effect model and incorporate both systematic and random error, whereas ICC3.3 is calculated from a two-way fixed effect model and incorporates only random error.16 19 Thus, the less systematic error contributes to the total error, the closer ICC2.3 is to ICC3.3.16 The second figure in the ICC designation represents single or average measures, where ‘1’ represents single measures and ‘2’ or higher represents the number of trials from which the average is calculated.16 ICC2.1 represents the reliability of a test procedure in which the subject is tested with a single trial on a test occasion.16 ICC2.3 and ICC3.3 represent the reliability of a test procedure in which the subject is tested with three trials on a test occasion and the score is expressed as the average of these trials.

To estimate absolute reliability, the SEM, SRD and SRD percentage (SRD%) were calculated for each of the three different ICC measures (ICC2.1, ICC2.3 and ICC3.3), resulting in the corresponding properties SEM2.1, SRD2.1, SRD%2.1, SEM2.3, SRD2.3, SRD%2.3, SEM3.3, SRD3.3 and SRD%3.3. The SEM was calculated according to , where SD was calculated from the total sum of squares (SSTOTAL) in the ANOVA table generated in the ICC analyses as .16 The SRD was calculated using the formula 1.96×SEM × , where 1.96 is related to the 95% CI and refers to the error of two measurements.16 The SRD% was calculated by dividing the SRD value by the grand mean multiplied by 100.2 10 This value is independent of measurement units and is indexed to the mean value of the observations from which it was derived. It is therefore a good measure for comparisons between different tests, scales and populations.10 14 17 An SRD% of 30% has been suggested as an acceptable level of reliability.20

Because estimates of absolute reliability vary with the type of ICC value, some caution is warranted when comparing them with measures from other studies.16 Therefore, SEMmean square error term (MSE) = was also calculated, where MSE (this term is called residual error by Hopkins and the mean square residual in the SPSS output) was taken from the ANOVA table of the ICC calculation.16 17 This SEM measure represents the reliability of a test procedure in which the subject is tested with a single trial on a test occasion, and it is a pure measure of random error.16 SRDMSE and SRD%MSE were also derived from SEMMSE.

The analysis of test-retest reliability was preplanned. SPSS V.21 was used to calculate ICC and ANOVA. The alpha level was set to 0.05.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or members of the public were involved in the development or design of this study.

Results

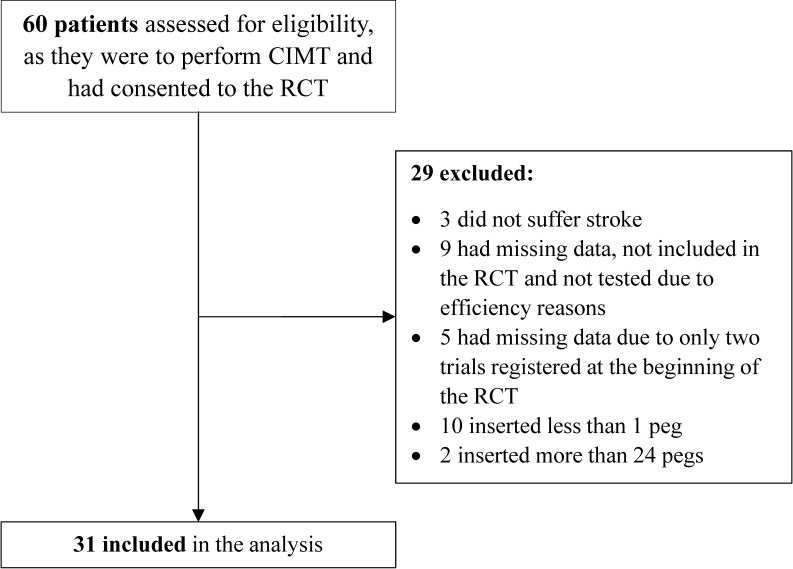

In this study, participants were recruited between January 2011 and September 2014. Of 60 eligible patients, 29 were excluded for any of the following reasons: not suffering a stroke, missing data and yielding either below the minimum or above the maximum number of inserted pegs (figure 2). This yielded 31 participants (21 men and 10 women) for inclusion in the analysis, with a mean±SD age of 66±9 years (table 1). The two eligible patients who were excluded because they exceeded the permitted maximum number of pegs inserted completed the 25 pegs in their best trial within 49.3 s and 39.4 s. Of the 10 patients who were excluded because they fell below the minimum number of inserted pegs, six inserted at least one peg in one of the trials. Data were collected from 17 and 14 participants by the two physiotherapists (third and last author, respectively) at seven clinics.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the recruitment process in the study. CIMT, constraint-induced movement therapy; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants at preintervention trials

| Participants | n=31 |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 66±9 |

| Men/women, n* | 21/10 |

| Time since stroke (months), median (IQR), (min–max) |

17 (8–24), (2–70) |

| Previous dominant hand more affected by stroke, n | 19 |

| TFHPT, mean of three trials (number of pegs), mean±SD, (min–max) | 10.8±6.8, (1–22.7) |

| Fugl-Meyer test (score), median (IQR), (min–max) |

46 (41–53), (29–62) |

| More than one stroke, n | 3 |

*Number of participants.

TFHPT, twenty-five-hole peg test.

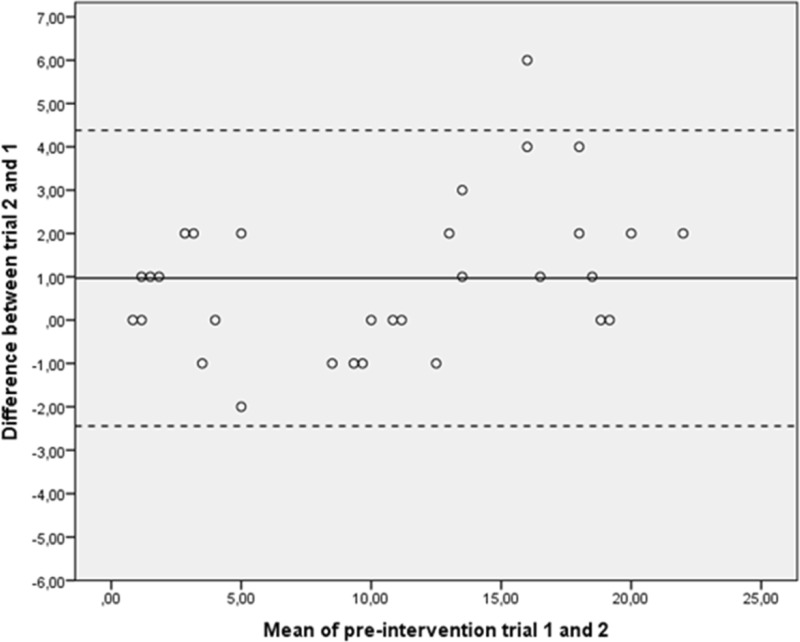

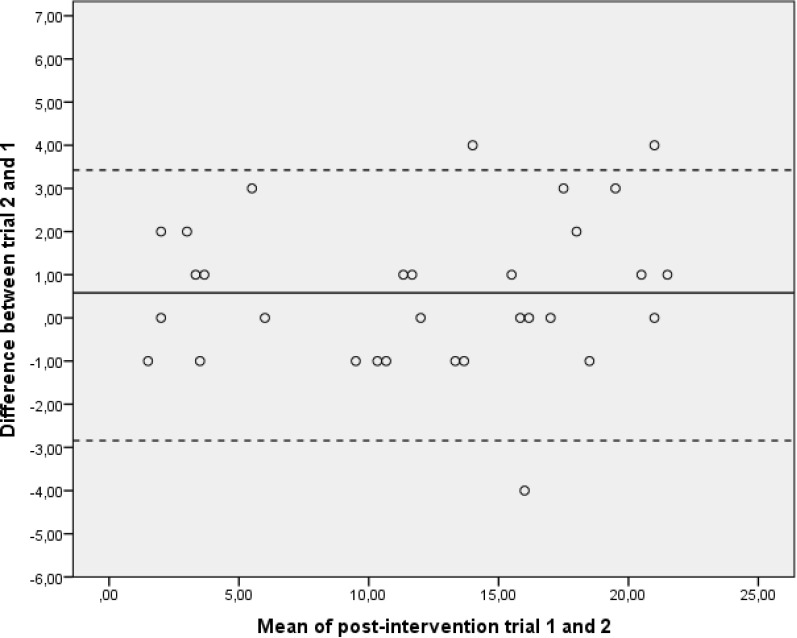

A graphic description of the data variability can be seen in the Bland-Altman plots (figures 3 and 4). According to Koenker’s studentised test, the measurement error was not affected by heteroscedasticity (table 2).

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman plots of numbers of pegs from preintervention trials. The mean of trials 1 and 2 was plotted against the difference of trials 2 and 1 for each subject. The centre line displays the mean difference for the group between trials 2 and 1. The upper and lower confidence limits were calculated as the mean difference±SD of the mean difference ×1.96.

Figure 4.

Bland-Altman plots of numbers of pegs from postintervention trials. The mean of trials 1 and 2 was plotted against the difference of trials 2 and 1 for each subject. The centre line displays the mean difference for the group between trials 2 and 1. The upper and lower confidence limits were calculated as the mean difference±SD of the mean difference ×1.96.

Table 2.

Results of the Koenker’s studentised test, n=31

| Pairwise test of trials | Preintervention trials | Postintervention trials | ||

| Χ2 | P value | Χ2 | P value | |

| 1–2 | 1.33 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.52 |

| 2–3 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 1.38 | 0.24 |

| 1–3 | 0.28 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 0.66 |

For preintervention trials, the mean values±SDs for trials 1, 2 and 3 were 10.0±6.5, 11.0±7.1 and 11.5±6.9, respectively. The one-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect between trials with F (2, 29)=10.9 and p<0.001. Post hoc tests revealed differences between trials 2 and 1 and between trials 3 and 1, with mean differences (95% CIs) of 1.0 (0.3–1.6) and 1.5 (0.9–2.2), respectively.

For postintervention trials, the mean values±SD for trials 1, 2 and 3 were 11.8±6.5, 12.4±6.7 and 12.5±6.8, respectively. The one-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect between trials with F (2, 29)=4.1 and p=0.027. Post hoc tests revealed a difference between trials 3 and 1, with a mean difference (95% CIs) of 0.6 (0.2–1.1).

For preintervention trials, ICC2.3 (95% CI) was 0.99 (0.97‒0.99) (table 3). The SRDs incorporating random and systematic error, SRD2.1 and SRD2.3, were 4.0 and 2.3 pegs, respectively. The corresponding SRD% values for SRD2.1 and SRD2.3 were 36.5% and 21.3%, respectively. The SRD incorporating only random error, SRD3.3, was 2.0 pegs.

Table 3.

Results of reliability measures for preintervention trials

| ICC (95% CI) | SEM*, n† | SRD‡, n | SRD%§ | |

| ICC2.1 | 0.96 (0.90 to 0.98) | 1.4 | 4.0 | 36.5 |

| ICC2.3 | 0.99 (0.97 to 0.99) | 0.8 | 2.3 | 21.3 |

| ICC3.3 | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | 0.7 | 2.0 | 18.3 |

| Derived from MSE | 1.3 | 3.5 | 32.1 |

*SEM derived from ICC2.1, ICC2.3, ICC3.3 and MSE.

†Number of pegs.

‡Smallest real difference derived from ICC2.1, ICC2.3, ICC3.3 and MSE.

§SRD percentage derived from ICC2.1, ICC2.3, ICC3.3 and MSE.

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; MSE, mean square error term; SEM, SE of measurement; SRD, smallest real difference.

For postintervention trials, SRD2.1 and SRD2.3 were 3.2 and 1.8 pegs, respectively (table 4). SRD3.3 was 1.8 pegs.

Table 4.

Results of reliability measures for postintervention trials

| ICC (95% CI) | SEM*, n† | SRD‡, n | SRD%§ | |

| ICC2.1 | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.98) | 1.1 | 3.2 | 25.9 |

| ICC2.3 | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.0) | 0.7 | 1.8 | 15.0 |

| ICC3.3 | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.0) | 0.7 | 1.8 | 15.0 |

| Derived from MSE | 1.1 | 3.1 | 25.5 |

*SEM derived from ICC2.1, ICC2.3, ICC3.3 and MSE.

†Number of pegs.

‡Smallest real difference derived from ICC2.1, ICC2.3, ICC3.3 and MSE.

§SRD percentage derived from ICC2.1, ICC2.3, ICC3.3 and MSE.

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; MSE, mean square error term; SEM, SE of measurement; SRD, smallest real difference.

Discussion

This study indicated that in a selected group of persons suffering from stroke, the absolute test-retest reliability of the TFHPT was at a level that can be considered acceptable for measures representing an average of three trials and incorporating systematic error.

To assess implications for the use of the TFHPT and to determine which SRD measure best captures the absolute reliability, three issues were considered: (1) whether to use single or average measures, (2) whether to include systematic error in the assessments and (3) whether to take heteroscedasticity into account.

Comparing SRD2.1 to SRD2.3 revealed that the use of an average of three trials reduced the measurement error by approximately 1.5 pegs compared with the use of a single trial. This finding suggests that the reliability of the TFHPT is substantially improved when an average of three trials is used.

Comparing SRD2.3 to SRD3.3, where SRD3.3 incorporates only random error, revealed that the contribution of the systematic error was approximately 0.3 pegs of the total 2.3 pegs when the average of three trials was used.16 Although the systematic error was small compared with the random error, it was not small enough to be overlooked in the assessment of reliability. Therefore, SRD2.3 is preferable to SRD3.3 for measuring the reliability of the TFHPT.

The choice of SRD% instead of SRD is dependent on whether the measurement error is affected by heteroscedasticity. A measure of absolute reliability, expressed as an absolute number of pegs, can overestimate or underestimate the number of pegs necessary to demonstrate an improvement for an individual.14 17 The reason is that the random error of measurements often increases with the magnitude of the measurements (ie, heteroscedasticity).14 17 As a remedy, the use of a relative measure of absolute reliability, such as SRD%, has been proposed.14 17 However, the lack of heteroscedasticity detection suggests that both SRD2.3 and SRD%2.3 are appropriate measures of reliability for the TFHPT.14

The results for SRD2.3 and SRD%2.3 were 2.3 pegs and 21.3%, respectively. The value of SRD%2.3 fell within the 30% level which has been suggested as acceptable.20 The 30% level seems high in this context, with persons affected by stroke in a chronic stage; from a clinical viewpoint, our opinion is that the results of 21.3% and 2.3 pegs in this study indicate a barely acceptable level of absolute reliability. For a favourable level, we believe that a mean number consisting of approximately 1.5 pegs is desirable.

The relative test-retest reliability, as measured by ICC2.3, was 0.99, which seems excellent. The discrepancy between the level of the relative and the absolute reliability is most likely caused by the heterogeneity in this study population (figure 3, table 1) which inflates the relative reliability.16

The level of the relative absolute test-retest reliability (SRD%), the most comparable measure, observed for the TFHPT in this study (21.3%) is better than what Chen et al 2 reported (54%) and is at approximately the same level as Ekstrand et al 3 reported (24%) for the NHPT. Although the SRD% measures reported in the studies by Chen et al and by Ekstrand et al were calculated in different ways than the SRD%2.3 reported in this study, the measures used in these three studies are fairly equivalent.16 Several methodological differences between these three studies could have affected the results.2 3 First, the results of the TFHPT and NHPT were measured using different scales, and the use of time for completion of the test in the NHPT should accommodate more variability than the peg count used in the TFHPT. However, the SRD% results should still be comparable between the TFHPT and the NHPT because this relative measure of absolute reliability adjusts for different scales and study populations.14 17 Second, in this study of the TFHPT, the test and retest trials were performed within minutes compared with within days in the studies of the NHPT. Thus, the TFHPT may seem more reliable because of possible random error from day-to-day variation in performance which was not captured in this study.17 21 Third, the longer time since stroke in this study of the TFHPT compared with the study of NHPT by Chen et al 2 may have resulted in seemingly better reliability for the TFHPT because of a more stable level of hand function. In the study by Chen et al, a systematic error may have originated in recovery from stroke in the 3–5 days between the test and retest trials because the time since stroke was 3 months or less for a quarter of the study sample.22

The implications of the results of this study are that the TFHPT can be used in a clinical situation to detect changes in a patient’s hand function. The test procedure should employ an average of three trials on each occasion, and a change of 2.3 pegs or more between two occasions should be considered real improvement/worsening. Furthermore, it seems that the ceiling effects in the TFHPT can be considered acceptable. Only two of the persons assessed for eligibility inserted 25 pegs, and only one of them actually hit the ceiling because according to this individual’s best times for completion of the 25 pegs, he/she would have been able to insert more pegs if available. This occurred in a sample where approximately a quarter of the included participants suffered from mild impairment of arm and hand function as judged by the Fugl-Meyer test.23 24

There was a tendency towards improved reliability after the CIMT period which was due to decreased systematic error and decreased random error. The decreased systematic error can be observed in the main effects of trial in the ANOVA results.16 The decreased systematic error is most likely due to a decreased learning effect when the participants had previous experience in the test. The learning effect is indicated by the increases in the mean values over the trials, especially over trials 1–2, and the decreased learning effect is indicated by the less pronounced increase in the postintervention trials.14 17 The lower random error can be observed from the lower SRD3.3 results in the postintervention trials.16 The cause of the decreased random error is less clear, but it could also be attributed to the decreased systematic error.17 This is because the magnitude of the learning effect probably differs between individuals, which will show as random error. Furthermore, it is likely that the SRD2.3 result of 2.3 pegs for TFHPT could, in reality, be adjusted downwards. A peg test is often used to evaluate a rehabilitation period; because the error is smaller in the postintervention trials, the ‘true’ SRD may be somewhere between the SRDs of the preintervention and postintervention trials (2.3 vs 1.8).

Four weaknesses of this study should be considered. The sample included a relatively low number of participants with few observations above 20 pegs and participants who were selected because they should benefit from CIMT.10 17 These sample qualities may thus, to some degree, hinder the generalisation of the results to other groups of people suffering from stroke. In addition, the intended practice trial was included as one of three trials in the analyses which appears to have contributed to systematic error through an increased learning effect, indicated by a large increase in the mean values between trials 1 and 2.14 16 17 Thus, to mitigate the learning effect, a practice trial preceding regular trials is recommended. Moreover, the possible day-to-day variation was not captured in the present study design. The advantage of this approach is that it yields a pure result for measurement error for the instrument in this population; the disadvantage is that the result is less clinically applicable.17 21 Finally, in this study, sensitivity to change and validity were not examined. However, the criterion validity for NHPT has mostly shown a moderate to excellent level4 5 and the underlying skill assessed with the TFHPT is most likely the same. A high reliability level is a prerequisite for high validity, and because the reliability of the TFHPT was at the same level as that of the NHPT, the criterion validity should also be similar.21

In conclusion, our results suggest that the smallest detectable difference between two assessments using a test procedure with an average of three trials conducted by a single tester should be just above two pegs with the TFHPT. Furthermore, to reach an acceptable level of measurement error, the use of the average of multiple trials is crucial. Future research should focus on optimising the number of trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff at the clinics for the extra work associated with participating in the RCT. The authors thank Håkan Littbrand for input on the conception of the study and Monika Edström for administrative work with the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study design and data interpretation: SE, FG, BL and MH. Data acquisition: SE, BL and MH. Statistical analysis: SE and FG. Drafting and finalisation of the manuscript: SE. Critical revision of the manuscript: FG, BL and MH. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: FG, BL and MH.

Funding: The Norrbacka-Eugenia Foundation; The Swedish STROKE-Association; The Stroke Foundation of Northen Sweden; and the Centre for Clinical Research Sörmland, Uppsala University.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå, reference 09-104M, with additional approval Dnr 2010/314-32M, Dnr 2011-244-32M and 2012-235-32M.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Santisteban L, Térémetz M, Bleton J-P, et al. Upper limb outcome measures used in stroke rehabilitation studies: a systematic literature review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154792 10.1371/journal.pone.0154792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen H-M, Chen CC, Hsueh I-P, et al. Test-retest reproducibility and smallest real difference of 5 hand function tests in patients with stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009;23:435–40. 10.1177/1545968308331146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ekstrand E, Lexell J, Brogårdh C. Test-retest reliability and convergent validity of three manual dexterity measures in persons with chronic stroke. Pm R 2016;8:935–43. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beebe JA, Lang CE. Relationships and responsiveness of six upper extremity function tests during the first six months of recovery after stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther 2009;33:96–103. 10.1097/NPT.0b013e3181a33638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin K-chung, Chuang L-ling, Wu C-yi, et al. Responsiveness and validity of three dexterous function measures in stroke rehabilitation. J Rehabil Res Dev 2010;47:563–71. 10.1682/jrrd.2009.09.0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carter RE, Lubinsky J, Domholdt E. Rehabilitation research: principles and applications. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier-Saunders, 2016: 239–44. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mathiowetz V, Weber K, Kashman N, et al. Adult norms for the nine hole PEG test of finger dexterity. Occup Ther J Res 1985;5:24–38. 10.1177/153944928500500102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oxford Grice K, Vogel KA, Le V, et al. Adult norms for a commercially available nine hole PEG test for finger dexterity. Am J Occup Ther 2003;57:570–3. 10.5014/ajot.57.5.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heller A, Wade DT, Wood VA, et al. Arm function after stroke: measurement and recovery over the first three months. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1987;50:714–9. 10.1136/jnnp.50.6.714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lexell JE, Downham DY. How to assess the reliability of measurements in rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2005;84:719–23. 10.1097/01.phm.0000176452.17771.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fugl-Meyer AR, Jääskö L, Leyman I, et al. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. A method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med 1975;7:13–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lindmark B, Hamrin E. Evaluation of functional capacity after stroke as a basis for active intervention. Validation of a modified chart for motor capacity assessment. Scand J Rehabil Med 1988;20:111–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lindmark B, Hamrin E. Evaluation of functional capacity after stroke as a basis for active intervention. Presentation of a modified chart for motor capacity assessment and its reliability. Scand J Rehabil Med 1988;20:103–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med 1998;26:217–38. 10.2165/00007256-199826040-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koenker R. A note on studentizing a test for heteroscedasticity. J Econom 1981;17:107–12. 10.1016/0304-4076(81)90062-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res 2005;19:231–40. 10.1519/15184.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hopkins WG. Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Med 2000;30:1–15. 10.2165/00007256-200030010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bland JM, Altman DG. Measurement error. BMJ 1996;312:1654 10.1136/bmj.312.7047.1654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420–8. 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang S-L, Hsieh C-L, Lin J-H, et al. Optimal scoring methods of hand-strength tests in patients with stroke. Int J Rehabil Res 2011;34:178–80. 10.1097/MRR.0b013e328342dd96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sim J, Wright C. Research in health care: concepts, designs and methods. Cheltenham, England: Nelson Thornes Ltd, 2002: 123–33. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kwakkel G, Kollen B, Twisk J. Impact of time on improvement of outcome after stroke. Stroke 2006;37:2348–53. 10.1161/01.STR.0000238594.91938.1e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duncan PW, Goldstein LB, Horner RD, et al. Similar motor recovery of upper and lower extremities after stroke. Stroke 1994;25:1181–8. 10.1161/01.STR.25.6.1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Woytowicz EJ, Rietschel JC, Goodman RN, et al. Determining levels of upper extremity movement impairment by applying a cluster analysis to the fugl-meyer assessment of the upper extremity in chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;98:456–62. 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.