Abstract

Objective

Early prediction of bacteraemia in the elederly is needed in the emergency department (ED).

Design, setting and participants

A prospective study in Japan; single-centre trial in patients who satisfied the sepsis criteria was conducted between September 2014 and March 2016. Forty-six elderly patients aged ≥70 years were included. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Osaka Medical College. Ethics Committee approval number was 1585.

Interventions

Blood sampling to evaluate C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT) and presepsin plasma levels; two sets of blood sampling for bacterial cultures; and evaluations of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation scores were performed on arrival at the ED. The results were compared between patients with bacteraemia and those without bacteraemia.

Main outcome measure

The accuracy of detecting bacteraemia.

Results

The presepsin value was significantly higher in the bacteraemia group than in the non-bacteraemia group (866.6±184.6 vs 639.9±137.1 pg/mL, p=0.03). The PCT and CRP did not significantly differ between the groups. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve values were not significantly different among presepsin (0.69), PCT (0.61) and CRP (0.53). Multivariate analysis showed that presepsin was independently associated with bacteraemia (OR 8.84; 95% CI 0.95 to 81.79; p=0.02).

Conclusion

Presepsin could be a good biomarker to predict bacteraemia in elderly patients with sepsis criteria admitted to the ED.

Keywords: presepsin, elderly patients, bacteraemia, emergency department, biomarker

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The number of elderly people who are brought to the emergency department (ED) has increased in recent years. Moreover, decreased immunity due to various underlying diseases, such as diabetes and malignant disorders, make early diagnosis of bacteraemia in the elderly important. This research was focused on the elderly on their arrival at the ED.

The present study had a relatively small sample size, a single-centre design and a relatively high exclusion ratio of eligible patients.

Our findings may have been underpowered and represented type 2 statistical error.

Introduction

Bacteraemia causes bacterial bloodstream infection that is associated with a significant mortality.1 2 In particular, the susceptibility to bacteraemia is increased in elderly people who have decreased immunity due to various underlying diseases, such as diabetes and malignant disorders.3 In recent years, the number of elderly people who are brought to the emergency department (ED) has increased in an ageing society. Therefore, early prediction of bacteraemia on arrival at the ED is important.

Blood bacterial culture is the gold standard to diagnose bacteraemia, but it requires several days to obtain the results.4 Various biomarkers, including C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT), had been used to support the diagnosis of bacteraemia.5 Presepsin, which is the soluble fraction of cluster of differentiation 14 (CD14), had been thought to be associated with infections,6 based on the fact that a subtype of CD14 is present inside and on the cell membranes of macrophages, monocytes and granulocytes, and is responsible for intracellular transduction of endotoxin signals. Several studies demonstrated that presepsin was more useful than PCT for the diagnosis of sepsis.7 8 In a systematic review and meta-analysis, presepsin levels were significantly lower in sepsis survivors than in non-survivors9; however, most of these presepsin levels were taken at the intensive care unit, not at the ED.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the accuracy of presepsin, in comparison with PCT and CRP, in predicting bacteraemia in elderly patients admitted to the ED for suspected infection with sepsis.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

This study was prospectively conducted at the ED of the Osaka Medical College Hospital between September 2014 and March 2016. Elderly patients aged ≥70 years and who fulfilled the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria or were suspected to have bacteraemia were eligible to enrol in this study. The exclusion criteria were terminal stage of malignant cancer, AIDS or end-stage liver disease, and absence of patient or relative consent to enrol in the study.

On arrival at the ED, all eligible patients underwent two sets of collection of 20 mL of blood samples for bacterial cultures and one collection of 10 mL of blood sample for measurements of CRP, PCT and presepsin levels in plasma. Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA)10 and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II)11 scores were also evaluated. The plasma levels of the three biomarkers and the morbidity scores were compared between two groups of patients: the bacteraemia group (ie, positive result on bacterial blood cultures) and the non-bacteraemia group (ie, negative result on bacterial blood cultures).

Measurement methods

Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. The results of our study will be disseminated to patient who wish to be notified.

The CRP, PCT and presepsin levels were measured in the blood specimens collected at the ED before antimicrobial agent administration. Blood samples of presepsin were collected in tubes that contained ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, with slow mixing followed by immediate centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The separated plasma of presepsin was collected and stored at −35°C until analysis. Plasma presepsin levels were determined only by a chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (PATHFAST immunoassay analytical system; Mitsubishi Chemical Medience Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. After sterilisation of the sites (either percutaneous or from a vascular access device) with the use of a chlorhexidine–alcohol mixture,12 two sets of 10 mL blood were obtained (one each for the aerobic and anaerobic bottles) and submitted to our central laboratory for culture.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the JMP V.13.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Continuous variables were presented as mean±SE and were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. A χ2 test was used to compare differences in the categorical variables. A multivariate logistic regression analysis model, which response variable was presence of bacteraemia, and explanatory variables were CRP, PCT and presepsin, was used to identify the influence of CRP, PCT and presepsin on bacteraemia. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to derive the optimal cut-off values, with sensitivity, specificity, predictive values and likelihood ratios, of the biomarkers in predicting bacteraemia and area under the curve (AUC) differences were assessed with DeLong test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research question and outcome measures was informed by the elderly patients who have decreased immunity due to various underlying diseases admitted to the ED. During the study design period, elderly patients aged ≥70 years and who fulfilled the SIRS criteria or were suspected to have bacteraemia were invited to participate in this study.

Results

Characteristics of the study population and microbiology results

Of 56 patients who were eligible for this study, 4 patients with terminal stage of malignant cancer, 4 patients with AIDS, 1 patient with end-stage liver disease and 1 patient who did not consent to enrol in this study were excluded. Therefore, 46 patients (28 men and 18 women) were included. The isolated bacteria were Gram-positive microorganisms in 11 cases (Staphylococcus caprae in 1, S. epidermidis in 5, S. hominis in 1, Lactobacillus acidophilus in 1, Enterococcus species in 1, Streptococcus species in 1 and Streptococcus equisimilis in 1) and Gram-negative microorganisms in 4 cases (Serratia marcescens in 1, Morganella morganii in 1, Klebsiella pneumoniae in 1 and Escherichia coli in 1).

Comparison between the bacteraemia and non-bacteraemia groups

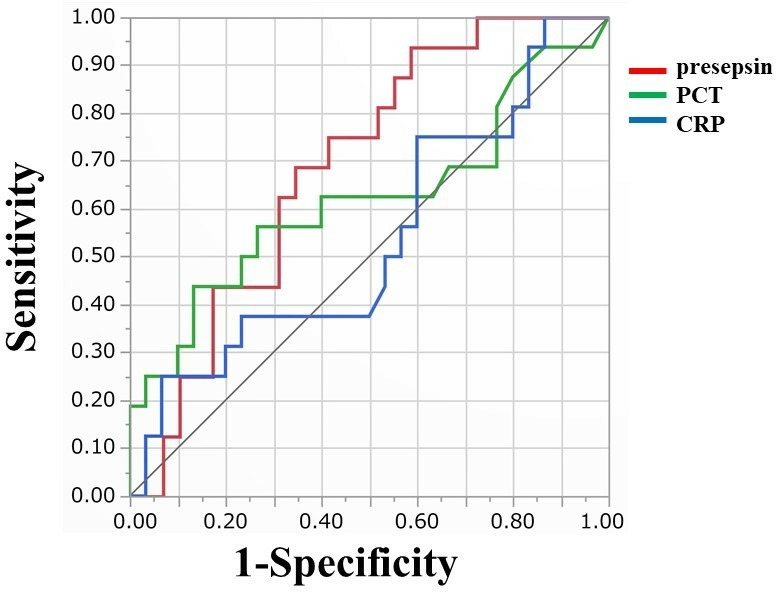

The univariate analysis showed no significant differences between the two groups in terms of sex (p=0.57) and age (p=0.86) (table 1). The presepsin value was significantly higher in the bacteraemia group than in the non-bacteraemia group (866.6±184.6 vs 639.9±137.1 pg/mL, p=0.03). Both groups were not significantly different PCT (p=0.18), CRP (p=0.66), SOFA (p=0.07) and APACHE II (p=0.53). The cut-off values derived from the ROC curves were 285 pg/mL for presepsin, 15.8 ng/mL for PCT and 34.6 mg/L for CRP (table 2). The AUC value of presepsin (0.69) did not significantly differ with that of PCT (0.61, p=0.30) and CRP (0.53, p=0.07) (figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Non-bacteraemia (n=30) |

Bacteraemia (n=46) |

P value (the univariate analysis) | OR | 95% CI | P value (the multivariate analysis) | |

| Age, years | 77.30±1.23 | 78.93±1.69 | 0.57 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Sex, n, male/female | 18/12 | 10/6 | 0.86 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Presepsin (pg/mL) | 639.93±137.10 | 866.56±184.58 | 0.03 | 8.84 | 0.95 to 81.79 | 0.02 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 6.77±10.05 | 45.04±13.76 | 0.18 | 2.89 | 0.19 to 0.56 | 0.18 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 12.64±2.38 | 15.41±3.26 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.06 to 6.54 | 0.71 |

| SOFA score | 2.20±0.47 | 4.2±0.65 | 0.07 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| APACHE II score | 13.63±1.0 | 14.56±1.37 | 0.53 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Continuous variables were presented as mean±SE.

APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; CRP, C-reactive protein; N/A, not available; PCT, procalcitonin; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Table 2.

Prediction of bacteraemia

| Cut-off | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | PPV, % | NPV, % | |

| Presepsin (pg/mL) | 285 | 93.7 | 41.3 | 46.8 | 92.3 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 15.8 | 43.7 | 86.7 | 63.6 | 74.2 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 34.6 | 25 | 93.3 | 66.6 | 70 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; NPV, negative predictive value; PCT, procalcitonin; PPV, positive predictive value.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve diagnostic value of presepsin, PCT and CRP for differentiating between positive and negative blood cultures. CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin.

In the multivariate analysis, only presepsin was the only significant risk factor for bacteraemia (OR 8.84; 95% CI 0.95 to 81.79; p=0.02). Because the number of cases was small, so three biomarkers were examined in this study.

Discussion

Early diagnosis of bacteraemia at the ED is very important for the initiation of appropriate treatments and to improve outcomes, but it is not easy and often overlooked, especially in elderly patients, in whom symptoms are not always straightforward and can be misleading. In this prospective study on elderly patients admitted to the ED, we found that (1) presepsin levels were higher with bacteraemia than with non-bacteraemia; (2) presepsin was an independent predictor of bacteraemia and (3) there was no significant difference in the AUC values among presepsin, PCT and CRP. Therefore, presepsin was superior to CRP and PCT in predicting bacteraemia in elderly patients admitted to the ED.

Liu et al 7 and Carpio et al 13 reported that the cut-off values of presepsin for mortality in septic ED patients were 556 and 825 pg/mL, respectively. Considering that the outcome of those studies was mortality, a cut-off value of 285 pg/mL for bacteraemia in our study might be reasonable. Romualdo et al reported that the cut-off value for bacteraemic SIRS was 729 pg/mL for ED patients with a mean age of 67 years.14 Leli et al reported that the cut-off value for bacteraemia was 843.5 pg/mL for suspected sepsis in internal medicine wards, in oncohaematology, in intensive care units and in surgery wards.15 In our study, the sensitivity was 93.7% and the negative predictive value was 92.3% at a cut-off value of 285 pg/mL for bacteraemia. In elderly patients who are more prone to infections, the cut-off value for bacteraemia might be lower compared with that in young people.

There were no significant differences in the SOFA and APACHE II scores between the groups. Notably, such physiologic estimations might have been offset by the elderly pathophysiologic characteristics, including dementia, which could have complicated consciousness assessment; potential hypertension, which could have rendered the blood pressure as normal; and the intake of various oral medications for other diseases. Nevertheless, the stronger correlations with the SOFA or APACHE II scores of presepsin than of PCT and CRP suggested that compared with PCT and CRP, presepsin more likely reflected the disease severity of elderly patients on arrival at the ED.

In this study, blood culture contaminations were likely. The median adult inpatient blood culture contamination rate was reported to be only 2.5%,16 and 12.4% rate of isolated coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) was reported to be clinically significant.17 Therefore, the presence of CNS in 7 of 16 (43%) positive blood cultures might have significantly affected the results of this study. However, our study population comprised elderly people who were susceptible to bacteraemia due to decreased immunity; therefore, the probability of isolating the true pathogens on culture is higher than that in adults. The other limitations of the present study include the relatively small sample size, the single-centre design and the relatively high exclusion ratio of 18% (10 of 56) of the eligible patients. Therefore, our findings may have been underpowered and represented type 2 statistical error.

In our study, the PCT cut-off value of 15.8 ng/mL suggested by the ROC was higher than in a systematic review and meta-analysis.5 The reason might be also explained by the small sample size and lack of data on patient’s medical history.

Bacteraemia can be identified in about 30% of septic patients and necessitates further diagnostic evaluation.18 Therefore, studies are needed in which the primary outcome would be to pick up patients at risk of adverse outcomes, not just the presence of bacteraemia.

Conclusion

This cohort study suggested that presepsin could be more useful than PCT and CRP in predicting bacteraemia in elderly patients admitted to the ED. Further studies are needed to define the exact cut-off value for the prediction of bacteraemia in these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the cooperation of the staff involved in the emergency department.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design of the study: YI and AT. Acquisition of data: YI, RI, MN and AT. Analysis and interpretation of the data: YI and AT. Material and financial support: YI, KT, RI, MN, KU and AT. Writing, review and/or revision of the manuscript: YI and AT.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Osaka Medical College. Ethics committee approval number was 1585.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1. Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1546–54. 10.1056/NEJMoa022139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thwaites GE, Scarborough M, Szubert A, et al. Adjunctive rifampicin to reduce early mortality from Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: the arrest RCT. Health Technol Assess 2018;22:1–148. 10.3310/hta22590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martin GS, Mannino DM, Moss M. The effect of age on the development and outcome of adult sepsis. Crit Care Med 2006;34:15–21. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000194535.82812.BA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flayhart D, Borek AP, Wakefield T, et al. Comparison of BACTEC plus blood culture media to BacT/Alert FA blood culture media for detection of bacterial pathogens in samples containing therapeutic levels of antibiotics. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:816–21. 10.1128/JCM.02064-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoeboer SH, van der Geest PJ, Nieboer D, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin for bacteraemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21:474–81. 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shozushima T, Takahashi G, Matsumoto N, et al. Usefulness of presepsin (sCD14-ST) measurements as a marker for the diagnosis and severity of sepsis that satisfied diagnostic criteria of systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Infect Chemother 2011;17:764–9. 10.1007/s10156-011-0254-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu B, Chen Y-X, Yin Q, et al. Diagnostic value and prognostic evaluation of presepsin for sepsis in an emergency department. Crit Care 2013;17 10.1186/cc13070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ulla M, Pizzolato E, Lucchiari M, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of presepsin in the management of sepsis in the emergency department: a multicenter prospective study. Crit Care 2013;17 10.1186/cc12847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang HS, Hur M, Yi A, et al. Prognostic value of presepsin in adult patients with sepsis: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0191486 10.1371/journal.pone.0191486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. on behalf of the Working group on sepsis-related problems of the European Society of intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:707–10. 10.1007/bf01709751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. Apache II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985;13:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maiwald M, Chan ESY. The forgotten role of alcohol: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical efficacy and perceived role of chlorhexidine in skin antisepsis. PLoS One 2012;7:e44277 10.1371/journal.pone.0044277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carpio R, Zapata J, Spanuth E, et al. Utility of presepsin (sCD14-ST) as a diagnostic and prognostic marker of sepsis in the emergency department. Clin Chim Acta 2015;450:169–75. 10.1016/j.cca.2015.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Romualdo LGdeG, Torrella PE, González MV, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of presepsin (soluble CD14 subtype) for prediction of bacteremia in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome in the emergency department. Clin Biochem 2014;47:505–8. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leli C, Ferranti M, Marrano U, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of presepsin (sCD14-ST) and procalcitonin for prediction of bacteraemia and bacterial DNAaemia in patients with suspected sepsis. J Med Microbiol 2016;65:713–9. 10.1099/jmm.0.000278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schifman RB, Bachner P, Howanitz PJ. Blood culture quality improvement: a College of American pathologists Q-Probes study involving 909 institutions and 289 572 blood culture sets. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1996;120:999–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weinstein MP, Towns ML, Quartey SM, et al. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures in the 1990s: a prospective comprehensive evaluation of the microbiology, epidemiology, and outcome of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 1997;24:584–602. 10.1093/clind/24.4.584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bates DW, Sands K, Miller E, et al. Predicting bacteremia in patients with sepsis syndrome. Academic medical center Consortium sepsis project Working group. J Infect Dis 1997;176:1538–51. 10.1086/514153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.