Abstract

Objectives

To systematically review the available literature on physicians’ and dentists’ experiences influencing job motivation, job satisfaction, burnout, well-being and symptoms of depression as indicators of job morale in low-income and middle-income countries.

Design

The review was reported following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines for studies evaluating outcomes of interest using qualitative methods. The framework method was used to analyse and integrate review findings.

Data sources

A primary search of electronic databases was performed by using a combination of search terms related to the following areas of interest: ‘morale’, ‘physicians and dentists’ and ‘low-income and middle-income countries’. A secondary search of the grey literature was conducted in addition to checking the reference list of included studies and review papers.

Results

Ten papers representing 10 different studies and involving 581 participants across seven low-income and middle-income countries met the inclusion criteria for the review. However, none of the studies focused on dentists’ experiences was included. An analytical framework including four main categories was developed: work environment (physical and social), rewards (financial, non-financial and social respect), work content (workload, nature of work, job security/stability and safety), managerial context (staffing levels, protocols and guidelines consistency and political interference). The job morale of physicians working in low-income and middle-income countries was mainly influenced by negative experiences. Increasing salaries, offering opportunities for career and professional development, improving the physical and social working environment, implementing clear professional guidelines and protocols and tackling healthcare staff shortage may influence physicians’ job morale positively.

Conclusions

There were a limited number of studies and a great degree of heterogeneity of evidence. Further research is recommended to assist in scrutinising context-specific issues and ways of addressing them to maximise their utility.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017082579.

Keywords: job morale, job motivation, job satisfaction, burnout, well-being and symptoms of depression, physicians, low- and middle-income countries

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is novel in synthesising qualitative data from all available research on low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) and provides conclusions based on findings from diverse countries, cultural backgrounds and clinical specialties.

This study can inform the design of potential interventions and workforce policies and interventions in LMICs; therefore, their clinical utility can be advanced.

Limited availability and heterogeneity of studies allowed drawing only tentative conclusions.

This study might be limited conceptually since a small number of studies were eligible.

Background

The crisis in human resources for health has been defined as one of the most severe global health problems1 and a major barrier to achieving universal health coverage and building a sustainable health system.2 This crisis is especially acute for low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), many of which suffer from both a shortage and poor devotion of healthcare staff.3

Due to the far-reaching effect of job morale, interest in the issue among healthcare staff has increased considerably in recent decades.4 First, positive job morale is linked to a greater number of healthcare workers being recruited and retained5 which appears to be essential in solving the pressing issue of healthcare staff maldistribution in LMICs.2 Second, healthcare staff with positive job morale are more likely to provide higher quality care to patients.6 7 Furthermore, improving staff well-being could save healthcare spending by decreasing financial investments in medical education8 and lower spending on sickness absence and staff turnover.9

Despite its importance, there is no universally adopted definition for the concept of job morale nor an agreement on what it constitutes. This could partially explain why research studies aiming to measure job morale are somewhat sporadic.10 11 Although several authors have tried to investigate job morale as a single entity,5 12–16 they ended up measuring its outcomes or explanatory variables.4 Particularly, they referred to the significance of job motivation, job satisfaction, well-being, burnout and depressive symptoms. All these variables can be regarded as indicators of job morale.

Most studies on job morale in healthcare have focused on either nurses10 11 17–21 or healthcare staff in general,5 13 22–25 although job morale has been shown to vary by professional group22 and training status.26–28 A limitation of the current academic literature is that relatively little is known about physicians’ and dentists’ experience of job morale in LMICs.29–31 There is a lack of detailed description of contextual features and latent influences which could be provided by qualitative research.32 Identifying and dentists’ experiences that influence job morale may help to create an analytical framework for analysing workforce policies and interventions with clinical and economic benefits.

Against this background, this review aimed to answer for the following research question: Which experiences influence job motivation, job satisfaction, burnout, well-being and symptoms of depression as indicators of job morale among physicians and dentists in LMICs?

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic search of electronic databases and grey literature was performed according to the review protocol. The following six electronic databases were searched: Scopus, Pubmed, PsycINFO, Embase, Web of Science and The Cochrane Library up to May 2018. Search terms combined three overlapping areas with key words such as ‘morale’ OR ‘job motivation’ OR ‘job satisfaction’ OR ‘well-being’ OR ‘burnout’ OR ‘depression symptoms’ AND ‘physicians’ OR ‘dentists’ AND ‘LMICs’ (see online supplementary file 1). Publication bias was reduced by searching conference papers and unpublished literature; hand searches of key journals and reference lists were performed. This review was reported following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.33

bmjopen-2018-028657supp001.pdf (95.3KB, pdf)

Selection criteria

Studies were eligible if they assessed any one of the job morale constructs such as job motivation, job satisfaction, well-being, burnout and depression symptoms by using qualitative methods; if at least 50% of the sample were qualified physicians and/or dentists employed in public healthcare settings or if data about qualified physicians and/or dentists employed in public healthcare settings were provided separately; if at least 50% of the sample were from the LMICs as defined by World Bank criteria34 or data from the country of interest was provided separately. Papers were excluded if more than 50% of the sample were not yet fully qualified physicians and (or) dentists who were undertaking training at the time of the study (medical students, residents, trainees, registrars or junior physicians), and if they were not written using Latin alphabet, Russian or Kazakh. There was no restriction on the date the studies were conducted. All included articles were inspected independently by a second researcher (SZS) to verify inclusion.

Considering the definitional imprecision of job morale and the different dimensions used to characterise it, we employed an inclusive approach adopting of five indicators of interest, including job motivation, job satisfaction, well-being, burnout and depression symptoms.

Review strategy

Titles and abstracts of identified articles were exported into EndNote V.X8 and were screened by the first reviewer (AS) in order to exclude irrelevant studies and duplicates. Full-text articles were inspected again for the relevance according to the inclusion criteria. A random sample of 20% of the articles was independently screened by the second reviewer (SZS) at each stage. Discrepancies were resolved by involving a third reviewer (SP). Mismatches at the full-text screening stage were added up and inter-rater reliability calculated. The level of agreement between AS and SZS was 80%, between AS and SP was 75%.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data from each paper, including study details, participant demographics and key results were extracted (see online supplementary file 2). In the case of mixed methods studies, only qualitative findings were extracted. The second reviewer (SZS) ensured the accuracy at this stage by extracting data from 20% of the included papers. One article written in Portuguese was extracted by involving a native speaker. Methodological quality was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) for qualitative studies.35

bmjopen-2018-028657supp002.pdf (73.8KB, pdf)

Data synthesis and risk of bias assessment

As part of the framework method,36 data from the results sections of included articles were coded in the reviewing software (EPPI-reviewer) and preliminary concepts describing physicians’ experiences were defined inductively. Similar concepts were grouped into categories and sub-categories independently by two reviewers (AS, SZS) and were discussed with other researchers (SP, FM, SN) to ensure the range and depth of the coding. The defined categories were then organised in the analytical framework. The framework matrix was used to provide a list of illustrative quotations. Additionally, vote counting37 was used as a descriptive tool to indicate patterns across the included studies. We calculated the frequency of defined categories to present how prevalent each category was within the included studies.

Based on CASP studies were appraised in accordance with 10 criteria, where the majority of studies were rated as appropriate with regard to aims, methodology and research findings (see online supplementary file 3).

bmjopen-2018-028657supp003.pdf (42.4KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

The results of the analysis were solely based on the previously published literature, as this study did not involve patients or public.

Results

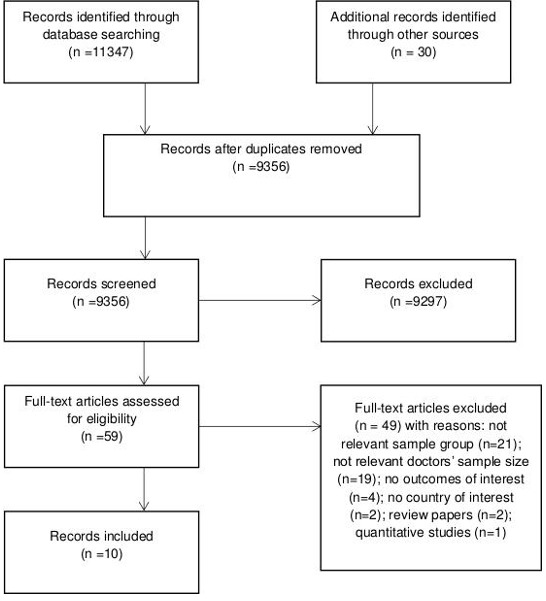

The original search yielded 11 347 articles through database searching and 30 through other sources. A total of 2021 articles were removed as duplicates, and 9297 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The full texts of the remaining 59 papers were examined, 10 of which were included and represented 10 unique studies. None of the studies focused on dentists’ experiences met the inclusion criteria. The detailed selection process is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Overview of included studies

Included studies were published between 2010 and 2017, in English, with the exception of one. They were conducted across seven LMICs, including four upper-middle-income countries (South Africa, China, Brazil and Russia), two lower-income countries (Pakistan and Moldova) and one low-income country (Uganda). With regard to the study design, four were mixed methods and six were qualitative. The majority of studies were conducted in primary31 38–42 and secondary healthcare settings.43 44 The included studies’ characteristics are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| N | Authors, year | Country (income group) | Setting | Study design | Data collection | Sampling | Sample size | Gender | Age/average |

| 1 | Ashmore, 201344 | South Africa (upper-middle income) | Urban | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (primary and follow-ups) | Purposive | 51 (28 dual practice doctors and 23 policy-makers/managers) | 64% males 36% females |

29–63/not stated |

| 2 | Chen et al, 201738 | China (upper-middle income) | Rural | Qualitative | Focus groups | Not stated | 39 doctors | 59% males 41% females |

Not stated/38–47 (in five different settings) |

| 3 | Feliciano et al, 201141 | Brazil (upper-middle income) | Urban | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews | Purposive | 24 doctors (12 paediatricians; 8 general practitioners, psychiatrist, infectologists, obstetric gynaecologist, anaesthesiologist) | 66.7% males 33.3% females |

Not stated |

| 4 | Kotzee and Couper, 200640 | South Africa (upper-middle income) | Rural | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews | Unclear: random or purposive (both stated) | 10 non-specialist qualified doctors | 60% males 40% females |

25–36/not stated |

| 5 | Li et al, 201739 | China (upper-middle income) | Rural | Mixed methods | Semi-structured interviews | Purposive | 34 (21 village doctors and 13 managers) | 76.5% males 23.5% females |

Not stated |

| 6 | Liadova et al, 201743 | Russia (upper-middle income) | Urban | Mixed methods | In-depth interviews | Not stated | 50 emergency doctors | 60% males 40% females |

25–50/not stated |

| 7 | Luboga et al, 201046 | Uganda (low income) | Not stated | Mixed methods | Focus groups | Stratified random | 49 doctors | 90% males 10% females |

26-70/36 |

| 8 | Malik et al, 201045 | Pakistan (lower-middle income) | Urban | Mixed methods | Open-ended questionnaire | Stratified random | 360 doctors | 50% males 50% females |

Not stated |

| 9 | Shah et al, 201631 | Pakistan (lower-middle income) | Rural | Qualitative | Semi-structured and in-depth interviews | Not stated | 22 (16 doctors and 6 managers/administrators) | 86.4% males 13.6% females |

Not stated/38 |

| 10 | Wallace and Brinister, 201042 | Moldova (lower-middle income) |

Urban | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | Purposive | 20 family physicians | 100% females | Not stated/ 42.4±7.2 |

Physicians’ experiences influencing job morale

Identified concepts relevant to physicians’ experiences of job morale were grouped into four main framework categories: work environment (I), rewards (II), work content (III) and managerial context (IV). The respective sub-categories within each of these categories are presented in the following section. Illustrative quotations within each category are provided in table 2.

Table 2.

Illustrative quotations

| Categories and sub-categories | Relevant studies (vote-counting) | Supporting quotations |

| I.Work environment | ||

| 1. Physical | Nine studies 31 38 40–46 | |

| 1.1. Working conditions | Eight studies 31 38 40–42 44–46 | |

| 1.1.2. Hospital infrastructure | Seven studies 31 38 40 42 44–46 | “Yes, it’s [the hospital] not really good for really working…” (Kotzee and Couper, 2006) |

| “I think we make our patients more sick in the hospital - somebody can come with one disease and go away with five diseases. The infection control is very poor mainly because the facility is so bad. Sometimes you have no soap to wash the hands. These are the hopeless situations when you are working in such a place that you feel very disgusted when you look at the bed, you look at the mattress on bed and you look at the bed sheets the patient is sleeping in.”(Luboga et al., 2011) | ||

| “Okay, you just go and look at the lavatories, especially in the public areas … That’s the consumer, but you know there are ways you can deal with that, and one of the ways to deal is that you have some sort of attendant, and constant cleaning of the lavatories. I mean a lot of patients come to me and … refuse to go to the lavatory because they say it’s so filthy… And that makes one feel very ashamed … Telephones get stolen… bed linen gets stolen, and you’re working in that environment… where there isn’t a blanket to put on the patient, there isn’t a pillow for her head and it’ s because things have been nicked. So and all of that you know is difficult.” (Ashmore, 2013) | ||

| “When you are engaged in work, it is difficult to survive in summer without air conditioning, because it is extremely hot in the summer in Guangxi, with peak temperatures even up to 40°C sometimes.” (Chen et al., 2017) | ||

| 1.1.3. Availability of resources | Seven studies 31 38 41 42 44–46 | “Okay firstly… our casualty… there is virtually nothing you know related to emergency…if you want to attend to an emergency patient there isn’t much you can use except maybe things like… IV lines…may be a drip stand; since I came here we didn’t have simple things like glucometers. So every time a patient comes and you want to do the glucose level you have wait for the lab to do it. Recently they have introduced some glucometers but they wok only for a few months… maybe there is one BP machine, which is used by two or three different wards. They have to wait until the other ward is done so they can go and borrow so it is – yeah – it is a problem” (Kotzee and Couper, 2006) |

| “Then another thing is equipment. We are doing operations but we do not have some equipment like theatre lights. After complaining we were given a tube for operation, but even in the whole ward we do not have enough lights. And can you imagine the whole of this hospital with only two oxygen concentrators? At least every ward should be having one or two. We have only one for the paediatric ward after complaining so long. So if you are using it on the child, and someone else needs it you either remove the child to die or you wait for the other to die.” (Luboga et al, 2011) | ||

| “…you are in the teaching facility. I mean you would love to have all the modern things like the books the overseas people are talking about and you would love to impart that knowledge onto your students. But we don’t have the equipment, I mean we have but you will find that they are outdated…” (Ashmore, 2013) | ||

| 1.2. Living conditions | Three studies 31 40 46 | “… the other most important thing is good accommodation; but anybody is going to struggle with accommodation they are not going to enjoy working there… you don’t want to wake up in the morning and know that you are going to share your bathroom with four other people and staff like that…” (Kotzee and Couper, 2006) |

| “…I joined BHU because I hoped to get a house to live; but the BHU residence is not worth living…” (Shah et al, 2006) | ||

| “Who will w willing to work in a BHU which doesn’t even have road access? I have to walk two kilometres daily to reach the main road leading to the BHU where I work.” (Shah et al, 2006) | ||

| 2. Social | Nine studies 31 38 40–46 | |

| 2.1. Relationships with nurses and auxiliary staff | Five studies 31 40 41 44 45 | “There is a difficulty I terms of the nursing staff and I don’t think when I was a registrar it was better. I think the staff were trained differently, they were trained in general nursing and then midwifery so the midwives instead of doing 3 months or whatever it is in midwifery and a general training so they’re less competent… the doctors picking up a lot of duties which the nurses should do automatically and they don’t…Which makes it far less satisfying for the doctor, and far more stressful because… you can’t trust the instructions are definitely going to be carried out.” (Ashmore, 2013) |

| “…it was shock to me, because in training people did not exist the nurse with as much power as she has today in the family health unit, it was a very big shock when I arrived… I see nurse being a doctor, I was horrified, so I asked myself: what I am doing here, what is left for me?” (Feliciano et al, 2011) | ||

| 2.2. Relationships with other physicians | Two studies 40 44 | “… it is very stimulating to work in a collegial and academic environment where you’re going to, you know, X-ray meetings and you’re on wards rounds, with consultants that are giving their different inputs…” (Ashmore, 2013) |

| “…what has helped keep me stimulated is even though we are in rural area there are so many visiting consultants coming from Wits and Garankuwa and Polokwane… Just knowing that there’s people coming every month or so that are interested in what you’re doing: that can support you and you can always ask them; it definitely improves the quality of your work and the job satisfaction and you feel less out of touch and that you’re doing the right thing, sometimes you need a bit of reassurance that you are doing the right things under the circumstances.” (Kotzee and Couper, 2006) | ||

| 2.3. Relationships with patients | Five studies 31 38 42–44 | “…some of my patients do not want to be informed or listen to me.” (Wallace and Brinister, 2010) |

| “Most patients with hypertension do not understand it. It is hard to convince them to come back to the clinic.” Wallace and Brinister, 2010 | ||

| “Sometimes they cursed and shouted at us. Even worse, some patients doubted the value of our medical services,” (Chen et al, 2017) | ||

| 2.4. Relationships with managers/supervisors | Five studies 31 40 43 44 46 | |

| 2.4.1 Respect | Two studies 40 44 | “I don’t think… [the administration]” quite realise the human resources they have available to them. I think sometimes they don’t actually realise they’re working with professionals, and they don’t treat us as such…” (Ashmore, 2013) |

| 2.4.2. Support | Two studies 44 46 | “You feel that you’re being hamstrung at every turn by the state you’re trying to do. They don’t make an effort to find out what’s required by people who are actually doing the job…” (Ashmore,2013) |

| 2.4.3. Recognition | Two studies 31 44 | “…In many other organizations, people with our skills and experience would be very highly valued and perceived as such. But you know here we don’t get perceived or treated like that at all… ” (Ashmore,2013) |

| 2.4.4. Autonomy | Two studies 43 46 | “…management gave appropriate autonomy to staff, while still providing adequate supervision.” (Luboga et al, 2011) |

| II. Rewards | ||

| 1. Financial | Eight studies 31 38–40 43–46 | “I am really willing to be a village doctor; it’s a good job, you know. However, the income is too low to subsist on. I must earn what I need for living. ” (Li et al, 2017) |

| “Now there are more and more people breeding silkworms. They even earn more than us (village doctors). ” (Li et al, 2017) | ||

| “Our main purpose (to work in BHUs) is salary; which does not match with our qualifications…” (Shah et al, 2006) | ||

| “I earned below 2000 RMB (USD 303) per month, and sometimes I work more than 14 hours in 1 day.” (Chen et al, 2017) | ||

| 2. Non-financial | ||

| 2.1. Career development | Five studies 31 40 44–46 | “… when you go into a job you need something that’s got a career path, and there aren’t career paths [in public]. There’s a few, a small little cadre at the top, a small group of people who get to principal or chief or specialist, and the rest of the people can spend their entire career as a senior specialist no matter how brilliant they are and much of a contribution they make.” (Ashmore, 2013) |

| 2.2. Professional development | ||

| 2.2.1.Learning opportunities | Five studies 31 40 41 44 45 | “…one of the things that is really distressing me for a few years, because [Family Healthcare Strategy] stopped doing the education work…” (translation) (Feliciano et al, 2011) |

| “Job satisfaction includes professional development, and there is no provision to allow us to further our qualification.” (Luboga et al, 2010) | ||

| 2.2.2.Teaching/research opportunities | One study 44 | “… it is good and interesting to have students around you. So the teaching component of it I’ve always found just varies your day. It adds a little bit of an extra dynamic to what your routines are, so it can be quite fan and it’s… a little bit challenging, and it just…adds spice to all your humdrum things.” (Ashmore, 2013) |

| 3. Social respect | Four studies 31 38 39 42 | “Although there have been many changes along with rapid development, patients still looks for me when they get sick because of my reputation. All their family members know me and come to me for help.” (Li et al, 2017) |

| “People hardly knew me when I just came back home for the job in 1998. At that time, patients didn’t know of my abilities. Everything was difficult. It got better several years later, as I worked longer.” (Li et al, 2017) | ||

| “Wherever we go, people respect us, just like we have some guarantee. We’re certainly satisfied by this.” (Li et al, 2017) | ||

| “People don’t consider a family physician important in their lives. They don’t appreciate their family physician, but they do specialists.”(Wallace and Brinister, 2008) | ||

| “Most of the patients here are local farmers. They are honest and full of integrity. They followed our advice and showed their appreciation to us.” (Chen et al, 2017) | ||

| III. Work content | ||

| 1. Workload | Eight studies 31 39 41–46 | “Too much workload now. I am in charge of only one village, with about 1500 residents. However, thy live dispersedly. One is here, while another is quite far away. I run around all day long, but still can only offer public health services for several households.” (Li et al, 2017) |

| “There is no time for my family and children.” (Wallace and Brinister, 2008) | ||

| “…the number of patients and the little time for consultation, so I have no conditions…” (translation) (Feliciano et al, 2011) | ||

| 2. Nature of work | Five studies 31 38 39 42 44 | |

| 2.1. Serving people | Four studies 31 38 39 42 44 | “…you feel like you’re making a tangible difference to people’s lives” (Ashmore, 2013) |

| “I like the work because you get to know entire families. My patients are like my extended family. When I get results, it makes me very happy.” (Wallace an Brinister, 2010) | ||

| “When my patients are cured after treatment, I feel so fulfilled and delighted. One patient still maintains contact with me. Our friendship began when he came to me with appendicitis. He has been well for 5 years now.” (Chen et al, 2017) | ||

| 2.2. Diversity | Two studies 42 44 | “You never know what the next case is. [Family medicine] forces you to use all the knowledge you learned at university” (Wallace an Brinister, 2010) |

| 3. Job security/stability | Three studies 31 44 45 | “…the public sector is rick solid, so you basically have to do something bad to get fired. So there is a high degree of certainty in your job…” (Ashmore, 2013) |

| 3.1.Safety | Three studies 31 44 45 | |

| 3.2.Physical | Two studies 31 45 | “Female physicians usually do not like to work in BHUs. The reason may be the lack of security…” (Shah et al, 2006) |

| 3.3.Legal | One study 44 | “In state you’ve got three levels of people below you, so if you’re…a state consultant, yes, you’ve got different stresses, you’ve got to give a lecture and you’ve got to give that, but I’m saying that’s a different type of stress. But on a clinical responsibility level, between you and the patients, there is an intern and registrar… So the family’s complaining… and that comes all the way through those two people before it gets you. So that’s like you’re three degrees removed.” (Ashmore, 2013) |

| IV. Managerial context | ||

| 1. Staffing levels | Seven studies 31 38 40 42–44 46 | |

| 1.1. Doctors’ and assistants’ deficiency | Five studies 31 38 40 44 46 | “…If you fell you can’t go away because there aren’t people to cover your work then it creates tension in your ability to care for people. So resources around you do matter…The deficit falls on you to work hard.” (Ashmore, 2013) |

| “There is only one medical assistant per family physician. That’s just not enough.” (Wallace and Brinister, 2010) | ||

| “We lack the doctors we need to provide adequate services. The shortage has pushed us to work longer. If more doctors could join us, that may ease our burdens.” (Chen et al, 2017) | ||

| 1.1.1. Retention | One study 44 | “I mean… in our department…to retain people is quite difficult, people work for a year or two then they go to private or they go off somewhere else. And for those posts to be filled again, it takes a lot of time… and in between people are frustrated.” (Ashmore, 2013) |

| 1.1.2. Absenteeism | Two studies 31 46 | “…30% posts of physicians in the province are filled and most of them do no attend to their duties regularly.” (Shah et al, 2006) |

| 1.1.3. Recruitment | Two studies 40 46 | “…They (managers) don’t advertise posts that are available, they’ll tell you in human resources that the posts are there but even if you qualify for the posts they tell that because it hasn’t been advertised, you can’t get into.” (Kotzee and Couper, 2006) |

| 1.2. Administrative staff deficiency | Three studies 42 44 | “…within every department there are the obvious managerial requirements that some people take up. So somebody might do the roster allocation, somebody might do the leave allocation, somebody might do the budgeting, all that kind of stuff within any department. And that is left mostly to the members of the department to do even though we have very little training or no training whatsoever in management.” (Ashmore, 2013) |

| *“There’s lots of paperwork, but it is easier now with the electronic medical record.” (Wallace and Brinister, 2010) | ||

| 2. Protocols and guidelines consistency | Four studies 31 41 44 46 | “…if the performance reports are not analysed properly, then no actions are expected. The performance appraisals currently in practice must be updated. Job descriptions do not exist in health department; older version of the documents needs to be updated.” (Shah et al, 2006) |

| “I think, medication prescription should be at the discretion of the physician…”(translation) (Feliciano et al, 2011) | ||

| 3. Political interference | Two studies 31 46 | “…Every patient is equal to us and we cannot give preference to a relative of a member of any political party. They try to influence us in several ways or they often threaten us to get us transferred to a remote BHU [Basic Healthcare Unit]” (Shah et al, 2016) |

| “We get political interference under decentralization…They look at negative aspects of our work and comment badly, coming anytime even after midnight to our homes. This is a member of parliament…” (Luboga et al, 2011) | ||

Work environment

Categories such as physical31 38 40–46 and social31 38 40–46 work environment appeared in all included studies.

Physical

Participants expressed that job morale was influenced considerably by working conditions, as a crucial source of job motivation45 and satisfaction.38 40 Few of them were ‘satisfied with physical environment’,31 but the majority of physicians felt ‘very disgusted’46 and ‘very ashamed’44 of the hospital infrastructure and constraints of resources, including lack of medicines and equipment deficiency.31 38 40 44 46 Additionally, physicians noted that poor physical environment in the hospitals ‘annoyed patients’31 and showed awareness that poor hygienic conditions were making patients ‘more sick’.46 The category addressing ‘physical work environment’ included residential living conditions for physicians who were based in more rural health settings.31 40 They described their residences as ‘inhabitable’ houses with poor ‘water and electricity connections’,31 that are ‘falling apart’.40 The limited options for schooling for their children31 46 and underdeveloped road access31 were frustrating and demotivating.

Social

Physicians described a sense of ‘collegiality’ and ‘regular interactions’ among staff in the healthcare facilities as a motivator44 and perceived ‘poor interpersonal relations’ as generally as demotivating.45 Four main sub-categories contributed to defining the ‘social environment’ category: relationships with nurses and auxiliary,31 40 41 44 45 relationships with other physicians40 44; relationships with patients31 38 42–44 and relationships with managers/supervisors.31 40 43 44 46

Participants questioned the professional ‘competency’44 and ‘power’41 of nurses and noticed that auxiliary staff were ‘unsupportive and apprehensive’ and worked ‘often without a license to practice’.31

Relationships with other fellow physicians were found to be ‘very stimulating’44 not only within a hospital, but this view also emerged in case of ‘visiting consultants’ in rural settings.40

There was inconsistency in experiences relating to physician-patient relationships. Some participants ‘seemed fairly happy’44 and ‘expressed satisfaction with their current relationships’.38 However, others expressed the view that physicians ‘often had to see angry patients’,31 who ‘could not understand the physicians’ work’38 and tend to ‘bring all their problems [beyond health-related]’.42 It was emphasised that “difficult” patients are a significant cause of physicians’ burnout.

Physicians indicated that relationships with managers/supervisors mainly depended on the provision of ‘adequate supervision’46 with enough respect,40 44 support,44 46 recognition31 44 and autonomy.43 46 ‘Poor supervision’45 demotivated physicians and ‘total control’ by managers/supervisors contributed to their burnout.43

Rewards

Almost all papers discussed the importance of financial31 38–40 43–46 and non-financial31 38–40 44–46 rewards in medical practice.

Financial

The majority of physicians felt that their financial compensation was ‘not acceptable’,46 ‘low’43 and ‘failed to reflect the job’s value’,38 especially in rural areas39 40 and considered their low salaries as a significant ‘demotivator’.45 However, some participants noted that medical practice has advantageous financial incentives, such as state pension, paid holidays and sabbatical leaves.44

Non-financial

Despite the importance of financial incentives, physicians highlighted that ‘money is not the most important factor for any clinician’.40 Career development appeared to be significant in determining physicians’ job morale.31 40 44–46 However, they showed the general sense of dissatisfaction ‘with overall process of promotions and transfers in the public health sector’.31 Conceptually, career development closely connected with the availability of learning, teaching and research opportunities31 40 41 44 45 which were ‘necessary for the professional growth of physicians’.31 Moreover, social respect was also considered a non-financial incentive31 38 39 42 which varied in terms of the professional reputation, gained by years of practice39 and admiration of public servants, as a part of the community culture31 and across different physicians’ specialties.42

Work content

The overarching category of ‘work content’ sub-categories, such as workload, nature of work,31 39 42 44 job security31 44 45 and physical and legal safety, was observed in almost all included papers as experiences influencing job morale.

Workload

The workload was mentioned broadly across all included studies.31 39 41–46 Specifically, physicians complained about ‘too many working hours’43 and the necessity to be ‘on the end of the phone’.44 Emergency duties and long working hours were especially discouraging for married female physicians and single mothers44 because they worried that ‘their other responsibilities remain unattended’.31 Additional frustration was related to a large number of patients in-charge39 and ‘fixed times for appointments’.42

Nature of work

Despite the excessive workload, physicians have emphasised that the ‘serving’ nature of medical profession31 38 39 42 44 and the diversity42 44 of work was extremely satisfying38 and motivating.45 Participants felt ‘a sense of achievement’38 when they ‘get results and see patients feeling better’.42 They also expressed a ‘passion to serve their own communities’.31

Job security/stability

Furthermore, some physicians reported that regardless of ‘whether you do it well or whether you don’t do it so well’44 working in public healthcare facilities ‘ensured job security for the rest of their careers’31 and provided them with the ‘ability to support’ their families.45

Physical and legal safety

The motivation experienced as a result of job security and stability was contrasted with the demotivation felt due to low levels of ‘personal safety’,45 especially for rural female physicians31 and growing responsibility for patients, ‘in [a] legal sense’.44 However, it has been noted that medico-legal risk for physicians could be mitigated by interns, residents and registrars, who ‘shield’ physicians from assuming complete medicolegal responsibility for all patients.44

Managerial context

Experiences within the managerial aspect of medical practice were broadly discussed in terms of the staffing levels,31 38 40 42–44 46 protocols and guidelines consistency,31 41 44 46 and political interference.31 46

Staffing levels

Low staffing levels of physicians, medical assistants and managers appeared to be a substantial cause of dissatisfaction38 44 and contributed towards absenteeism31 46 and retention problems.44 Excessive workload caused by the deficit of physicians46 and medical assistants42 resulted in physicians being frequently ‘absent’ from their duties31 and ‘encourage[d] others to leave’44 as well. Moreover, it seemed quite difficult to attract people to work in healthcare facilities, ‘despite the district posting the growing vacancies for multiple years, no applications had been received’.46 At the same time, physicians raised a concern that vacant posts may not be advertised properly.40 The additional burden of paperwork42 43 fell on physicians as a result of administrative staff deficiency44 which could be alleviated by implementing electronic medical systems.42

Protocols and guidelines consistency

Physicians stated that job description, protocols and guidelines regulating the drug prescriptions41 and performance appraisal31 processes ‘needed to be revised to include the solutions to the current work place problems’.31 Nonetheless, the ‘growing requirements’43 as a consequence of the increasing number of ‘regulations and rules’44 were highlighted as a source of frustration44 and burnout.43

Political interference

Certain physicians felt that managerial work context was possibly disrupted by ‘politically powerful persons’31 interfering ‘in the decision making [process] at health facilities’46 and their attempts to get a prioritised treatment for relatives.31 Some participants believed that it was difficult to be promoted or transferred to a desired position ‘without links with any influential person’31 and mentioned cases of ‘intimidation of health workers by local politicians’.46

Discussion

Main findings

The aim of our systematic review was to synthesise qualitative studies exploring physicians’ experiences influencing job motivation, job satisfaction, burnout, well-being and symptoms of depression as indicators of job morale in LMICs.

The analytical framework that comprised four main categories of the work environment (I), rewards (II), work content (III) and managerial context (IV), was developed based on concepts that emerged from included studies. According to the vote counting results, workloads, working conditions and financial rewards were most frequently mentioned as influencing job morale and have been described in almost all studies. The majority of studies mentioned important experiences regarding staffing levels, career and professional development, relationships with nurses/auxiliary staff and managers/supervisors. Physicians from almost half of the included studies focused their attention on the nature of work, relationships with patients, protocols and guidelines consistency.

Physicians were quite consistent in defining whether their experiences were positive or negative. Experiences of excessive workload, low salaries, poor working and living conditions, fewer opportunities for career and professional development, staff shortage, tense physician–nurse and physician–manager/supervisor relationships, inconsistent professional guidelines and political interference were described as negative. Although physicians reported more negative experiences, positive experiences were also underlined in terms of the serving nature of work, being given social respect, job stability and collegial relationships with other physicians.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of qualitative studies exploring physicians’ experiences influencing job morale in LMICs. A further strength is that the review searched through papers from all LMICs and was not limited by physicians’ specialty or to English language publications. This allowed for the inclusion of data from diverse countries, cultural backgrounds and clinical specialties. However, this approach presented some limitations. First, although it was possible to extract general concepts in physicians’ experiences, there is not enough evidence to assess whether these apply to all medical specialties and to other countries. There may be regional and clinical nuances that have not been identified in this review. Second, the prevalence of negative experiences over positive ones could be caused by a biased focus of studies on exploring difficulties. Third, heterogeneity of studies due to imprecise definitions of the concept of ‘job morale’, made it challenging to provide firm conclusions. Although dentists were included in the literature search, none of the studies on dentists met the inclusion criteria; therefore, the results cannot be generalised to them.

Despite these limitations, the current review is a valuable collation of studies and specifies which experiences influence the job morale of physicians.

Comparison with literature from high-income countries

The present review supports qualitative findings from previous studies that have been conducted in high-income countries (HICs). It is particularly consistent with findings that serving and helping patients,13 47 48 working on diverse medical cases13 22 48 49 and healthy relationships with other medical staff13 14 48 50 51 constitute positive experiences and enhances workers’ job morale. It supports evidence that excessive workload,16 22 49 50 52 insufficient staffing levels,13 16 51 administrative burden16 22 50 and poor relationships and understanding between medical staff and managers13 16 50 influence job morale negatively. In general, the tendency that professionals are more satisfied with the job content than with its structure and management can be observed not only among physicians. It applies also to employees of different occupations.

Contrary to our findings, healthcare staff employed in high-income countries indicated positive experiences regarding the consistency of existing protocols and guidelines,13 48 relationships with patients47 50 51 and opportunities for continuing education.22 The review also demonstrated some evidence regarding poor physical environment within healthcare facilities and constraints of resources, as has been recorded previously.13 16 50 However, these findings should be interpreted with caution due to their context-dependency.53 The context often includes increasing poverty,54 inequality55 and collapsing healthcare systems.56 57 The structural adjustment programmes promoted by international financial institutions and widely implemented across LMICs may influence the context.58–61 In particular, the freezing of vacant posts and mandated ceilings on wages can be substantial barriers to recruiting and retaining healthcare staff.55 62 63

Quantitative findings from research on healthcare staff working in HICs helped to corroborate the results of this review. Single studies and reviews conducted in HICs also report associations between job morale and factors such as financial rewards,64–68 workload,4 64–66 68 recognition,13 23 support,16 23 autonomy,23 65 67 staffing levels,69 learning/teaching/research opportunities,64 69 workload,4 64–66 68 diversity of work,64 68 relationships with colleagues,23 64 65 67 69 job security and protocols and guidelines consistency.16 67 This is consistent with what this review found in LMICs. Despite this consistency, it is not clear as to whether evidence from HICs can be simply transferred to LMICs and the other way around.

Implications for research and practice

By considering physicians’ experiences across seven LMICs, the current review findings suggest that in order to advance current clinical practices by enhancing job morale, interventions and workforce policies should aim at increasing salaries, improving working and living conditions, tackling healthcare staff shortage and excessive workload and providing more opportunities for career and professional development. However, it is very difficult to achieve in resource-scarce settings. Finding the right balance between growing demands and limited resources is a key challenge. A critical approach to healthcare policy with a specific reference to ethics and a range of disciplines in social science are likely to be required to achieve and maintain that balance.70 71 Also, findings suggest that professional guidelines, such as job descriptions, performance appraisal and protocols regulating drug prescriptions should be revised and effectively implemented. This may have a potential positive influence on physician-nurse relationships by maximising role clarity.

There are at least four implications for future research. First, in order to generate clear directives for improvements, future research studies should investigate whether job morale is perceived and valued differently by different medical specialties, and the research gap around dentists’ experiences should be addressed. Second, the structural and social determinants of job morale of physicians in LMICs should be studied more systematically which requires funding for such research. Third, contextual features should be considered as they might limit the applicability of findings from one healthcare setting and region to another. Fourth, existing interventions and strategies should be assessed rigorously to define implementation requirements, cost-effectiveness and long-term changes.

Conclusions

The current review has identified that perceived threats to positive job morale of physicians in LMICs outweigh perceived incentives. It has highlighted several areas in which strategies aiming to improve physicians’ job morale in in LMICs may be targeted. However, generalised conclusions are tentative because of the heterogeneity, limited number and inconsistent quality of the existing studies. Future research into physicians’ experiences influencing job morale in LMICs should robustly examine context-specific issues and appropriate ways of addressing them, to ensure that the results can be translated into practical programmes for improving healthcare practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to all members of the Unit for Social and Community Psychiatry for their assistance in data analysis. We wish to thank Dr Mariana Pinto da Costa for translating the article in Portuguese.

Footnotes

Contributors: AS and SP designed the study with input from SN. AS conducted the systematic searches of the literature, selected the studies, performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. SZS ensured the consistency of study selection, data extraction and analysis. FM contributed to the analysis and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was sponsored by the Kazakhstan Ministry of Education and Science Center forInternational Programs as part of a PhD studentship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Aluttis C, Bishaw T, Frank MW. The workforce for health in a globalized context – global shortages and international migration. Glob Health Action 2014;7:23611 10.3402/gha.v7.23611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030 Geneva. Switzerland: World Health Organisation, 2016. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/pub_globstrathrh-2030/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO The world health report 2006 - working together for health Geneva. Switzerland: World Health Organisation, 2006. http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grieve S. Measuring morale - Does practice area deprivation affect doctors' well-being? 1997. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Reininghaus U, Priebe S. Assessing morale in community mental health professionals: a pooled analysis of data from four European countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007;42:237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Department of Health Nhs health and wellbeing: final report. Department of Health, 2009. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130124052412/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_108907.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, et al. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159015 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mills EJ, Kanters S, Hagopian A, et al. The financial cost of doctors emigrating from sub-Saharan Africa: human capital analysis. BMJ 2011;343:d7031 10.1136/bmj.d7031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chaudhury NHJ. Ghost doctors: absenteeism in Bangladeshi health facilities. The World Bank, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10. McFadzean F, McFadzean E. Riding the emotional roller-coaster: a framework for improving nursing morale. J Health Organ Manag 2005;19:318–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Day GE, Minichiello V, Madison J. Nursing morale: what does the literature reveal? Aust. Health Review 2006;30:516–24. 10.1071/AH060516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnsrud L K. Measuring the quality of faculty and administrative Worklife: implications for college and university Campuses 2002.

- 13. Totman J, Hundt GL, Wearn E, et al. Factors affecting staff morale on inpatient mental health wards in England: a qualitative investigation. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11 10.1186/1471-244X-11-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson S, Wood S, Paul M, et al. Inpatient mental health staff morale: a national investigation 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Gulliver P, Towell D, Peck E. Staff morale in the merger of mental health and social care organizations in England. J Psychiatr MENT health Nurs. England 2003:101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cahill J, Gilbody S, Barkham M, et al. Systematic review of staff morale in inpatient units in mental health settings 2018.

- 17. Callaghan M. Nursing morale: what is it like and why? J Adv Nurs 2003;42:82–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02582.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cox KB. The effects of unit morale and interpersonal relations on conflict in the nursing unit. J Adv Nurs 2001;35:17–25. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01819.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haw MA, Claus EG, Durbin-Lafferty E, et al. [Improving job morale of nurses despite insurance cost control. 1: Organization assessment]. Pflege 2003;16:103–10. 10.1024/1012-5302.16.2.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang K-P, Huang C-K. The effects of staff nurses' morale on patient satisfaction. J Nurs Res 2005;13:141–52. 10.1097/01.JNR.0000387535.53136.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hagopian A, Zuyderduin A, Kyobutungi N, et al. Job satisfaction and morale in the Ugandan health workforce. Health Aff 2009;28:w863–75. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Priebe S, Fakhoury WKH, Hoffmann K, et al. Morale and job perception of community mental health professionals in Berlin and London. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005;40:223–32. 10.1007/s00127-005-0880-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson S, Osborn D, Araya R, et al. Morale in the English mental health workforce: questionnaire survey 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24. Bowers L, Allan T, Simpson A, et al. Morale is high in acute inpatient psychiatry. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2009;44:39–46. 10.1007/s00127-008-0396-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abraham LJ, Thom O, Greenslade JH, et al. Morale, stress and coping strategies of staff working in the emergency department: a comparison of two different-sized departments. Emerg Med Australas 2018;30:375–81. 10.1111/1742-6723.12895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. NHS Staff Surveys. Available: http://www.nhsstaffsurveys.com/Page/1064/Latest-Results/2017-Results/

- 27. Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med 2014;89:443–51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A, Benos A. Burnout in internal medicine physicians: differences between residents and specialists. Eur J intern Med. Netherlands 2006:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chopra M, Munro S, Lavis JN, et al. Effects of policy options for human resources for health: an analysis of systematic reviews. The Lancet 2008;371:668–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60305-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mathauer I, Imhoff I. Health worker motivation in Africa: the role of non-financial incentives and human resource management tools. Hum Resour Health 2006;4 10.1186/1478-4491-4-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shah SM, Zaidi S, Ahmed J, et al. Motivation and retention of physicians in primary healthcare facilities: a qualitative study from Abbottabad, Pakistan. Int J Health Policy Manag 2016;5:467–75. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Victora CG, Habicht J-P, Bryce J. Evidence-Based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health 2004;94:400–5. 10.2105/AJPH.94.3.400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World bank open data, 2018. Available: https://data.worldbank.org

- 35. Critical appraisal skills programme. CASP qualitative, 2018. Available: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist.pdf

- 36. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme 2006.

- 38. Chen Q, Yang L, Feng Q, et al. Job satisfaction analysis in rural China: a qualitative study of doctors in a township Hospital. Scientifica 2017;2017:1–6. 10.1155/2017/1964087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li T, Lei T, Sun F, et al. Determinants of village doctors' job satisfaction under China's health sector reform: a cross-sectional mixed methods study. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:64 10.1186/s12939-017-0560-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kotzee TJ, Couper ID. What interventions do South African qualified doctors think will retain them in rural hospitals of the Limpopo Province of South Africa? Rural Remote Health 2006;6:581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Feliciano KVdeO, Kovacs MH, Sarinho SW. [Burnout among Family Healthcare physicians: the challenge of transformation in the workplace]. Cien Saude Colet 2011;16:3373–82. 10.1590/s1413-81232011000900004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wallace LS, Brinister I. Women family physicians' personal experiences in the Republic of Moldova. J Am Board Fam Med 2010;23:783–9. 10.3122/jabfm.2010.06.100089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liadova AV, Korkiya ED, Mamedov AK, et al. The burnout among emergency physicians: evidence from Russia (sociological study). Man in India 2017;97:495–507. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ashmore J. 'Going private': a qualitative comparison of medical specialists' job satisfaction in the public and private sectors of South Africa. Hum Resour Health 2013;11:1 10.1186/1478-4491-11-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Malik AA, Yamamoto SS, Souares A, et al. Motivational determinants among physicians in Lahore, Pakistan. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:201 10.1186/1472-6963-10-201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Luboga S, Hagopian A, Ndiku J, et al. Satisfaction, motivation, and intent to stay among Ugandan physicians: a survey from 18 national hospitals. Int J Health Plann Manage 2011;26:2–17. 10.1002/hpm.1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zwack J, Schweitzer J. If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Academic Medicine 2013;88:382–9. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318281696b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sofia Kjellström and Gunilla Avby and Kristina Areskoug-Josefsson and Boel Andersson Gäre and MONICA Andersson B. work motivation among healthcare professionals: a study of well-functioning primary healthcare centers in Sweden. Journal of Health Organization and Management 2017;31:487–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Agana DF, Porter M, Hatch R, et al. Job satisfaction among academic family physicians. Fam Med 2017;49:622–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reid Y, Johnson S, Morant N, et al. Explanations for stress and satisfaction in mental health professionals: a qualitative study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999;34:301–8. 10.1007/s001270050148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hall L, Johnson J, Heyhoe J, et al. Strategies to improve general practitioner wellbeing: a focus group study 2017;35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kruse GR, Chapula BT, Ikeda S, et al. Burnout and use of HIV services among health care workers in Lusaka district, Zambia: a cross-sectional study. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:55 10.1186/1478-4491-7-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Willis-Shattuck M, Bidwell P, Thomas S, et al. Motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:247 10.1186/1472-6963-8-247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mohindra KS. Healthy public policy in poor countries: tackling macro-economic policies. Health Promot Int 2007;22:163–9. 10.1093/heapro/dam008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kentikelenis AE. Structural adjustment and health: a conceptual framework and evidence on pathways. Soc Sci Med 2017;187:296–305. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nolan T, Angos P, Cunha AJLA, et al. Quality of hospital care for seriously ill children in less-developed countries. The Lancet 2001;357:106–10. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03542-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Travis P, Bennett S, Haines A, et al. Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the millennium development goals. The Lancet 2004;364:900–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16987-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Beste J, Pfeiffer J. Mozambique's debt and the International monetary fund's influence on poverty, education, and health. Int J Health Serv 2016;46:366–81. 10.1177/0020731416637062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Laurell AC. Three decades of neoliberalism in Mexico: the destruction of Society. Int J Health Serv 2015;45:246–64. 10.1177/0020731414568507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Coburn C, Restivo M, Shandra JM. The African Development Bank and women’s health: A cross-national analysis of structural adjustment and maternal mortality. Soc Sci Res 2015;51:307–21. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hossen MA, Westhues A. The medicine that might kill the patient: structural adjustment and its impacts on health care in Bangladesh. Soc Work Public Health 2012;27:213–28. 10.1080/19371910903126754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kentikelenis AE, Stubbs TH, King LP. Structural adjustment and public spending on health: evidence from IMF programs in low-income countries. Soc Sci Med 2015;126:169–76. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thomson M, Kentikelenis A, Stubbs T. Structural adjustment programmes adversely affect vulnerable populations: a systematic-narrative review of their effect on child and maternal health. Public Health Rev 2017;38:13 10.1186/s40985-017-0059-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Van Ham I, Verhoeven AAH, Groenier KH, et al. Job satisfaction among general practitioners: a systematic literature review. Eur J Gen Pract 2006;12:174–80. 10.1080/13814780600994376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Scheurer D, McKean S, Miller J, et al. U.S. physician satisfaction: a systematic review. J Hosp Med 2009;4:560–8. 10.1002/jhm.496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tomljenovic M, Kolaric B, Stajduhar D, et al. Stress, depression and burnout among hospital physicians in Rijeka, Croatia. Psychiatr Danub 2014;26 Suppl 3:450–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Goetz K, Jossen M, Szecsenyi J, et al. Job satisfaction of primary care physicians in Switzerland: an observational study. Fam Pract 2016;33:498–503. 10.1093/fampra/cmw047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Joyce C, Wang WC. Job satisfaction among Australian doctors: the use of latent class analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy 2015;20:224–30. 10.1177/1355819615591022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Janus K, Amelung VE, Gaitanides M, et al. German physicians “on strike”—Shedding light on the roots of physician dissatisfaction. Health Policy 2007;82:357–65. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. McCoy D. Critical Global Health: Responding to Poverty, Inequality and Climate Change Comment on "Politics, Power, Poverty and Global Health: Systems and Frames". Int J Health Policy Manag 2017;6:539–41. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schrecker T. Interrogating scarcity: how to think about 'resource-scarce settings'. Health Policy Plan 2013;28:400–9. 10.1093/heapol/czs071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028657supp001.pdf (95.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028657supp002.pdf (73.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028657supp003.pdf (42.4KB, pdf)