Abstract

Objectives

To describe the social networks that diffuse knowledge, attitudes and behaviours relating to different domains of practice within teams of trainee doctors in an acute hospital medical setting. The domains examined were ‘clinical-technical’, ‘patient centredness’ and ‘organisation of work’.

Design

Sequential mixed methods: (i) sociocentric survey of trainee consisting of questions about which colleagues are emulated or looked to for advice, with construction of social network maps, followed by (ii) semi-structured interviews regarding peer-to-peer influence, analysed using a grounded theory approach. The study took place over 24 months.

Setting

An acute medical admissions unit, which receives admissions from the emergency department and primary care, in a National Health Service England teaching hospital.

Participants

Trainee medical doctors working in five consecutive rotational teams. Surveys were done by 39 trainee doctors; then 15 different participants from a maximal diversity sample were interviewed.

Results

Clinical-technical behaviours spread in a dense network with rich horizontal peer-to-peer connections. Patient-centred behaviours spread in a sparse network. Approaches to non-patient facing work are seldom copied from colleagues. Highly influential individuals for clinical technical memes were identified; high influencers were not identified for the other domains.

Conclusion

Information and influence relating to different aspects of practice have different patterns of spread within teams of trainee doctors; highly influential individuals were important only for spread of clinical-technical practice. Influencers have particular characteristics, and this knowledge could guide leaders and teachers.

Keywords: internal medicine, change management, medical education & training

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first research describing several coexisting social networks in the same team in medical practice.

Interviews were used to explore and explain phenomena underlying the social network patterns.

The surveys and interviews could be subject to recall bias, which is a recognised issue in social network research.

Respondents may be subject to influence and learning that they are not conscious of, and so an ‘invisible’ social network may have been overlooked.

We researched social networks within bounded teams of trainee doctors; links to other doctors outside the core team and links to other disciplines are not included.

Introduction

Doctors in training are important members of the clinical microsystems that deliver acute medical care.1 The quality of that care is affected by the knowledge, attitudes and behaviours that they bring to bear. Despite long undergraduate and postgraduate training, many elements of real-world care can be under-represented in the formal curriculum, including broader patient-centred behaviours, such as expressing compassion, shared decision-making and providing good experience and practical skills such as managing oneself and one’s work.2 3 Once qualified, trainee doctors form communities of practice and continue to acquire skills and knowledge through ‘on the job’ contextual learning.4–6 Learning from peers is an important and valued part of this experience. A national multispeciality survey of trainee doctors rated learning from other trainees as contributing more to their learning than lectures, tutorials and reading.7 Knowledge of the patterns of peer-to-peer connections that channel such spread would enable quality improvement leaders and teachers to optimise uptake of new practice across clinical teams.8

The aim of this research is to explore how knowledge, attitudes and behaviours diffuse between individuals through different network structures within bounded teams of trainee doctors. Different types of skills and behaviours impact the quality of medical care. Clinical-technical knowledge and skills help trainees reach correct diagnoses, and deliver correct treatments (an example would be knowing which patients should undergo a certain diagnostic test). Patient-centredness skills increase the quality of patient and carer experience (an example would be the ability to reassure an anxious patient). We postulated a third category, that we termed ‘organisation of work’, by which we refer to the skills that allow clinicians to prioritise and order tasks, particularly non-patient facing tasks, so as to reduce the cost of care (an example would be the ability to prioritise tasks that impact resource use) (online supplementary file 1). We hypothesised that memes, (using the original meaning: a unit of knowledge, attitude or behaviour that can spread between individuals through communication or imitation) relating to these different aspects of day-to-day work may be conducted via different channels within the same clinical team.9 If this is the case, it may be necessary to use different approaches to disseminate memes associated with the different domains and this knowledge would serve as a guide to clinical leaders and quality improvement agents who aim to change practice across diffuse clinical teams.

bmjopen-2018-027039supp001.pdf (34.4KB, pdf)

We conducted the research among several different teams of trainee doctors a single acute medical unit (AMU). The AMU provides care for the initial 24 to 72 hours of an emergency medical hospital admission.10 11 AMU trainees have access to a relatively large team of colleagues who they can approach for advice, or who’s work they can observe. We constrained the research to interactions that occur in real time during work and did not explore use of electronic media. The study used a mixed methods sequential design, with surveys mapping network structures, followed by interviews with members from later teams that added to and triangulated the survey data and explored survey findings.

Ethical issues

All participants gave informed consent.

One researcher (PS) was a consultant who spent some time working in the unit. We believe that the relationship between PS and the trainees was not such that participants would feel coerced. All trainees invited took part, we believe this is because we ensured participation was convenient.

The surveys asked people to name colleagues who were influential for them. We reassured participants that confidentiality would be maintained and survey data would be in anonymised format.

Methods

Participants

Participants were doctors in training working in a single acute admission unit in an National Health Service hospital. Teams of doctors are allocated to the unit, at 4 to 6 monthly intervals. They are training in internal medicine, but they have different experiences and skills that they bring from previous roles. The research was conducted in five consecutive teams, each of approximately 20 trainee doctors, over a total period of 24 months. The first two teams completed electronic surveys, and the members of the following four teams participated in interviews.

Surveys

We invited all trainees in two consecutive AMU teams to complete an electronic survey (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah). The sociometric survey (online supplementary file 2) included questions about who they had asked for advice, who they would choose to approach in future and who have they emulated or been influenced by in the AMU team. The questions were repeated for each of the three domains. Teams completed 19 and 20 surveys respectively. Survey responses were converted to unweighted directional edges and entered into SocNetV software to construct network graphs for each of the two teams, one graph for each work domain.

bmjopen-2018-027039supp002.pdf (30.8KB, pdf)

Method of approach: Participants were invited at the end of routine team meetings to take part by accessing the survey on their electronic devices.

Interviews

Participants were selected as a maximum diversity sample, to include representatives at different stages of training to avoid bias. Subjects were approached on a 1:1 basis in the workplace and invited to do an interview at a time convenient to them. All those invited agreed to take part.

Two researchers conducted interviews. GS, research fellow, (female) had no prior contact with the teams; PS (male) was a consultant physician and had had some intermittent working contact with the participants. Both had previous experience of qualitative research at postgraduate level. Coders agreed that there were no apparent differences between the findings from the interviews of the two researchers. PS as interviewer had preconception that highly influential individuals would be those with less patient-centred attitudes. These preconceptions relate to PS’s own training in the 1980s. Results were very different from these views, and we believe that these preconceptions did not cause bias. GS is a non-clinical researcher and had no previous knowledge of acute medical practice.

Interviews were semi-structured, and included vignettes to illustrate the meaning of the domains. Interview guides included questions about which colleagues were particularly influential, and what their characteristics were, in order to explore the finding of the presence of high influencers from the initial survey phase of the study. Interview guides are included as online supplementary file 3.

bmjopen-2018-027039supp003.pdf (34.4KB, pdf)

We were not aware of any existing literature on knowledge transfer and influence specifically related to different aspects of practice. We used the domains as a framework to guide interviews, but used an inductive-deductive grounded theory approach to develop novel theories about the ways that diffusion happened and the way that influencers were identified. Developing theories were fed back in subsequent interviews for triangulation.12

Theoretical analysis was done independently by two coders using NVivo V.11.4.1 (QSR International Pty Ltd). Coding was done after every two to four interviews. Themes that developed were incorporated as prompts into subsequent interviews. When items were coded differently the coders discussed these and reached consensus. Interviews continued until it appeared that theoretical saturation was achieved. Initial interview guides are appended.

Patient and public involvement

None.

Results

Surveys

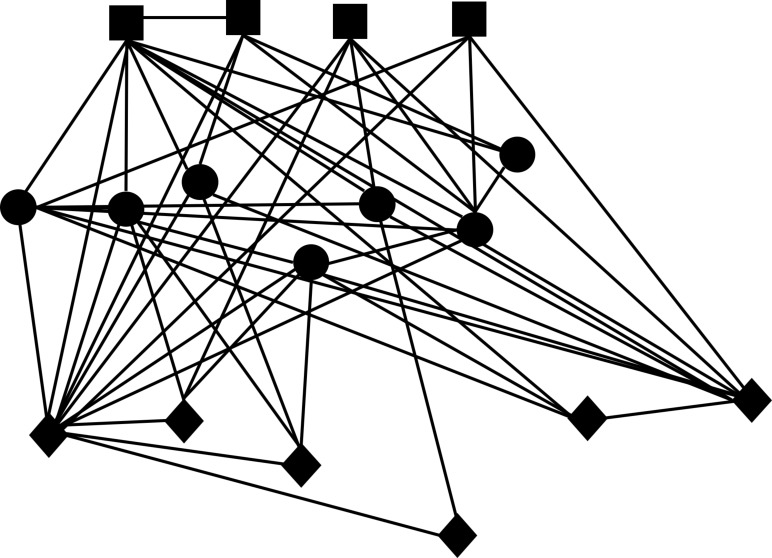

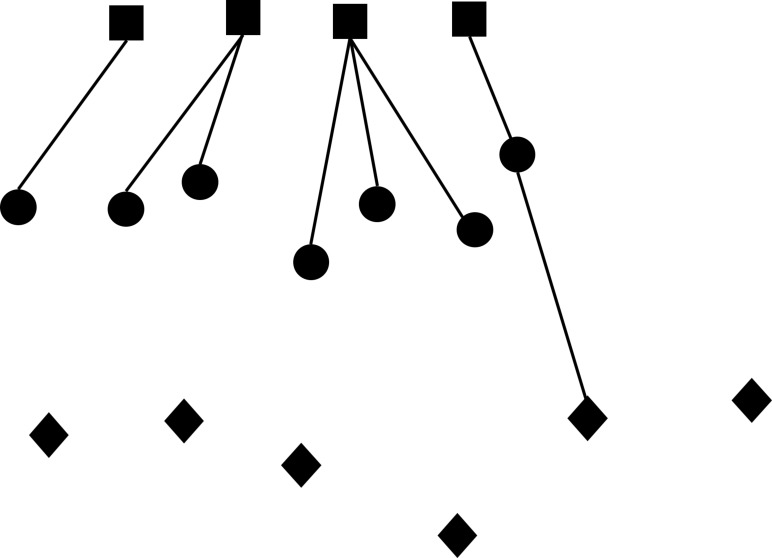

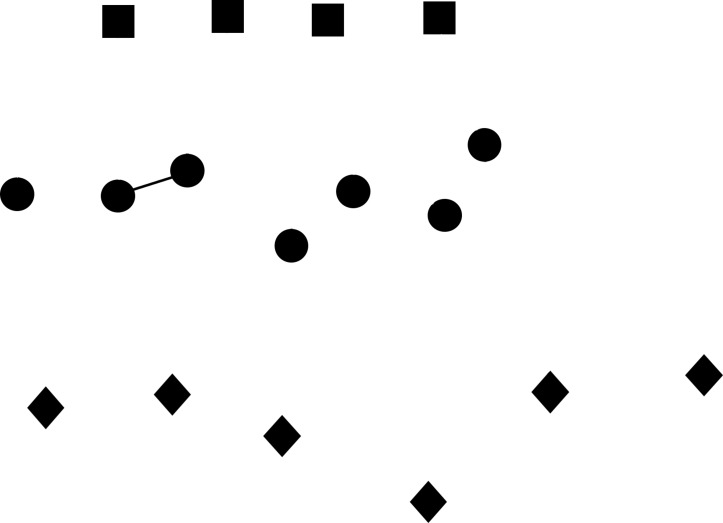

We found that clinical-technical knowledge flowed through dense networks with rich horizontal connections, (see figures 1–3). In contrast, the network conducting memes relating to patient-centredness was sparse, and where there was person-to-person transmission, it tended to be among isolated pairs with no chains. Ways of organising work were apparently hardly influenced at all by others. For the clinical technical domain, the average number of people each individual influenced (average degree) was 3.7 and 3.5 for team 1 and team 2, and the number of connections as a proportion of the maximum possible (density) was 0.3 and 0.2. Equivalent values for the patient-centred domain were lower, 0.4 and 0.6 for average degree and 0.03 and 0.02 for density. Values for the communication of memes relating to organisation of work were 0.05 and 0.00 for average degree and 0.003 and 0.00 for density. Figures 1–3 show the network graphs for the three domains for team one; the graphs for team two showed similar topography. Some individuals showed network features of high influencers. These were high degree centrality (the number of connections that an individual has) and betweeness centrality (the number of bridges an individual completes between others) which is associated with the ability to control information flow.13

Figure 1.

Network graph showing directed connections that conduct clinical-technical knowledge and influence. Square=CT 4-7 grades (registrar), Circles=CT 1–3 (seniorhouse officer), Diamonds=FY 1–2 (house officer).

Figure 2.

Graph for network relating to the patient-centred behaviours.

Figure 3.

Graph for network relating to the non-patient facing practices.

Interviews

We conducted 15 interviews and consider that theoretical saturation was achieved. Participants were representative of the mix of levels of seniority within the team of trainees: five foundation year (house officer, US intern equivalent), seven core or speciality trainees in year 1 to 2 (senior house officer, US resident equivalent), three core or speciality trainees in year 3 to 7 (registrar, resident or fellow equivalent); nine were female, all had trained in UK medical schools.

Theories that emerged were; (i) there were characteristics of actions that determined if they would be taken on board by a trainee, and (ii) there were characteristics of people that determined if their advice would be used or actions emulated; (iii) some values and beliefs that influenced behaviour came from outside of work; (iv) patterns of influencing differed between domains.

There was consensus among trainees that a significant proportion of their work practice was based on learning from peers.

You learn a lot of theory in med school but actually when you get here things are done differently and you learn by seeing what people more senior or experienced do. FY1

Domain 1: technical-clinical; diagnosing and treating

Characteristics of influencers

Chief determinants of individuals who were technical influencers were approachability and kindness, a record of visible successes and conscientiousness.

Approachability was based not only on the way an individual had responded in the past to requests for help and advice, but also on how kind they were in general — to patients and to members of other disciplines; trainees predicted that people who were globally kind would be kind to them if they sought advice.

My feeling is their empathy toward patients will be similar to their empathy toward me

There’s definitely people who won’t give you a hard time. You can see how they are toward other people, nurse, patients. CT1

Many participants expressed that they valued kindness toward patients for its own sake, and held kind colleagues in higher esteem, and were more likely to trust and copy their technical practices.

I think, to be honest, the number one thing is kindness. (referring to judging global competence) CT1

Someone who’s kind to patients and kind to everyone on the ward …… that’s the kind of person I would copy in other ways. CT2

Conversely,

Even if they’re, say, a brilliant diagnostician or surgeon, if I see someone behaving badly with a patient, I struggle to learn from them.

Trainees valued friendship and friendliness

If they’re pally, if you’ve chatted to them before, consider them friends, you’re likely to trust their knowledge and skills.

I’m much more likely to copy the good bits in the people I’m already on good terms with who might be my friend.

Individuals who were seen as committed to doing their job well were influencers.

Some work hard at being good at their job, you’ll walk in on them, like, reading things online and things, that kind of person I would be more inclined to copy. CT2

There are certain doctors, I like the way they go about the profession, I feel I could learn a lot by acting like them. CT1

Characteristics of actions and behaviours themselves could make them more likely to be emulated.

A great deal of weight was placed on observable success. This might be an unlikely disease picked up by a test, or a treatment when a patient is seen to recover. Strategies such as diagnostic workup were valued when ‘thorough’, meaning that several possible diagnoses were considered and excluded. When a colleague explained the logic behind a clinical approach, the trainees were more likely to incorporate it.

Domain 2: providing good patient experience

All trainees expressed that they had never, and did not envisage that they would in future, ask for advice on interpersonal interaction with a patient. There was a feeling that this was a behaviour that should be determined by one’s own values that largely came from outside the profession and often predated medical school.

I think you come with ideas of how you’d like to be, how you’d like to speak to people.

You’re taught a lot of science but you sort of come before that with an idea of how you want to provide people with dignity and being honest and open, that’s the values I’ve had, it’s been long-term.

I had that sort of preconceived idea from before I even came to medical school.

As a source of these values, parental influence was mentioned most often; trainees felt they carried the beliefs and behaviours that their parents displayed. Other cited sources were secondary school, social groups, exposure to life in general and, in only one case, religion.

Probably from parents, encouraging good values, I was just always told that’s the way to do it and eventually it becomes part of who you are.

Characteristics of actions and behaviours

When questioned about the ways that they could be influenced at work to behave differently toward patients, all trainees talked about communication skills and learning through observing ways that conversations were phrased. Trainees wanted to improve skills in ‘set piece’ situations, such as end-of-life discussion. They copied snippets, to use in the future.

We explored what they meant by good communication that they would emulate. A commonly cited criterion was a successful outcome. Examples of success included the patient appearing to understand what they were being told, evidenced by verbal or non-verbal signals. A number cited as an example of success a patient being convinced to change their mind and accept a treatment that the doctor felt they should receive.

In contrast to the clinical domain, personal characteristics of the person who was being observed was not perceived to impact on whether they would be influential.

If I can see there’s progress being made, personality is neither here or there, if goal has been achieved. FY2

Going beyond learning about phrasing, we explored the influencing of wider values and attitudes

Characterisitics of people

Many participants tended to select role models who had similar values, with the role model used to reinforce existing beliefs/behaviours.

I guess I come to it with a kind and caring nature and one of the important things I look for in a role model is, do they have that too?

There is a subconscious… why did I get into this and who do I deem also to be in for the right reasons, actually to help people and look after patients.

I guess, me, personally I've always been an all rounder, I see it’s important I have respect for an all rounder like me, that’s who I will look to; being kind is part of being an all rounder.

Trainees particularly noticed small discretionary acts, cited examples included making tea for a patient, responding to a patient who is calling out for attention and making a special effort to contact a patient’s relatives. Several felt that they had behaved differently after seeing somebody else put themselves out to provide good patient experience.

If I see Dr X make someone a cup of tea I think I SHOULD try to be more like that, I SHOULD try to be better.

Some trainees discussed the way that observing negative patient-centred behaviours could affect them, and felt their behaviour was adversely affected when the majority of a team were behaving in a non-patient centred way. However, they felt that they were more strongly influenced by seeing what they felt was good patient-centred care, than bad. When local culture was contrary to good care, they could be inspired for the good by a single individual.

If someone said ‘hang on a minute let’s think about what more we can do for the patient’, I think definitely I’d stop and take a moment and think ‘is there more we can do’. FY1

Domain 3: organisation of work

Trainees generally agreed that there were no personal characteristics that made an individual influential in terms of ways of organising work.

There was a sense of willingness to do work differently if asked to do so but only by people who worked in the same clinical context and knew about how things worked. There was resistance to adapting practice in response to requests from people seen as outsiders, particularly managers.

…if it’s someone doing a similar job to you, I’d be inclined to try it, but if it was someone not from this environment, someone in a suit, someone who doesn’t do a job like this, my reaction to that would be ‘actually you don’t understand how busy this job is’. FY2

If a senior ward nurse asked me to do something this way, because it helped them, I'd be more likely.

There was a strong sense that an approach would have to be tested personally before adoption.

If someone did something, and it seemed to work, I’d try it to see if it worked, it wouldn’t matter whether I looked up to that person or not

There was a widespread feeling that trainees could not make a difference to care by the way they organised their work because the system is so inflexible it tends to negate benefits of improving working practices, and so it is not worth trying to improve one’s efficiency.

Discussion

Behaviours and information flow from individual to individual. This leads to dissemination of knowledge and influence across groups through patterns of habitual connections that are termed social networks. This phenomenon has been described in a broad range of social contexts, including clinical teams.14–16 Social network analysis explores the way that individuals interact with social context, and how structures emerge from interpersonal interactions, increasing our understanding of behaviours. Previous research has shown that social networks are key for developing practice among trainee doctors.17–19 Knowledge about the function of networks among trainees offers important intelligence for those who aim to improve the quality of care within frontline clinical microsystems through training and influence. Most existing studies of health professionals have mapped generic social networks, without differentiating or identifying the type of information conducted.20 In the teams of medical trainees that we investigated, we found that there were multiple synchronous network structures channelling memes relating to different domains of practice. This is the first study to our knowledge that has mapped coexisting networks that conduct different kinds of information within a single clinical team.

We found that learning and influence in the different domains studied flowed very differently, if at all. Clinical-technical knowledge flowed through densely connected networks. In contrast, the networks relating patient centredness were present but were sparse, and there were suggestion from interviews that there were important influences outside the team and the profession. ‘Organisation of work’ appeared not to have any direct peer-to-peer spread. This suggests different strategies might be needed to introduce memes relating to different domains. New clinical technical knowledge is the most likely to diffuse passively within a team. Patient-centred behaviours have a limited degree of peer-to-peer transfer, and so enthusiasts might best role model these behaviours frequently, to multiple members of a team. Organising work appears to be devoid of any spread or emulation, and human factor approaches might be more successful than role modelling.

Interviews provided triangulation for the survey finding of the existence of a few high clinical-technical influencers. Attributes of clinical-technical influencers included consistent kindness, and signs of conscientiousness. An interesting finding was that trainees appraised clinical management on the basis of visible diagnostic or therapeutic success. This is at odds with the fact that many diagnostic strategies deliberately aim for low yields, and many treatments have a high ‘number needed to treat’ or delayed outcomes: Therefore many correct management approaches have visible success only on rare occasions. This makes explanation of underlying logic important in teaching.

In relation to the spread of patient centredness, trainees did not identify highly influential individuals, and it was actions themselves were seen as more or less worthy of emulation. Compassion, a concern for the impact of behaviours on the patients’ internal psychological state was not volunteered as a driver. Instead, communication interactions were judged on the basis of ‘getting the job done’, for example, getting a message over accurately or getting the patient to agree with the doctor on a decision. The failure to talk about concern for the patient’s emotions may be an artefact of the kind of language used day-to-day, and may not reflect an absence of compassion. However, the findings point to a need for leaders to be explicit about behaving to improve patient experience and to demonstrate and teach approaches such as shared decision-making. An interesting finding was that trainees described that they looked to people they felt to be similar to themselves as their role models. Doctors felt they carried their own values from outside their professional life, and looked for validation, rather than looking to adopt new sets of values. If true, this has impactions for those hoping to inculcate values among trainees, suggesting that amplification of existing attitudes may be more appropriate.

Many of these findings are in keeping with existing literature. The presence of high influencers in healthcare teams is established. In keeping with our own results, the personality characteristics associated with this network influencing roles have been shown to include contentiousness and agreeableness.21 The importance of perception of the utility of a practice, which we found to be key for adoption of ways of organising work, is also described elsewhere.22

We have added an extra dimension to existing knowledge of healthcare professional networks by differentiating and describing social networks that spread different kinds of work-related information and influence in medical teams. This can inform teaching and communication strategies according to the domain of practice being targeted. Our findings also provide insight into how an individual might adapt their own behaviour so as to exert more influence.

This work has a number of limitations. It was conducted in a single centre, and may not be representative of all acute settings, although in mitigation, six different consecutive clinical teams were included over a period of 2 years. We limited the research to trainee doctors, and did not include other professions; previous work has described the importance of networks that span professional groups; it would be interesting to go on to perform more inclusive studies. Future research could explore how individuals from outside of the core team and from different disciplines exert influence, and how electronic media provides wider peer-to-peer links. The categorisation of memes into three domains is pragmatic and probably over simplistc, and there are many more subtle aspects of practice that could be explored in future work.

Conclusion

The social networks of influence and knowledge transfer among trainee doctors in an acute setting conform to quite different patterns when considering the spread of innovations in three domains, technical-clinical, patient-centred and organisation of work. The characteristics and prevalence of highly influential individuals also differs between domains. This casts light on the way that practices develop across a team, informs those who wish to enhance their influencing, and emphasises the importance of making desirable behaviours clearly visible to facilitate their spread. Knowing how these coexisting networks are configured and driven is likely to be useful for those leading quality improvement work that requires on the uptake of innovative behaviours across a clinical microsystem.

This article presents independent research supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care programme for North West London. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: PS conceived the study; PS and GS collected data; PS, GS, MH and IY all contributed to analysis and writing.

Funding: PS is funded by Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Trust and NIHR CLAHRC NW London; GS is funded by Danone Ltd; IY is funded by The Health Foundation, UK.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Hampshire-B REC; reference 15/SC/0052.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Nelson EC, Godfrey MM, Batalden PB, et al. . Clinical microsystems, part 1. The building blocks of health systems. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2008;34:367–78. 10.1016/S1553-7250(08)34047-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fernandez A, Teherani A, Boscardin CK, et al. . Assessment of medical students' shared decision-making in standardized patient encounters. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:367–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burack JH, Irby DM, Carline JD, et al. . Teaching compassion and respect; attending pysicians’ responses to problematic behaviors. J Gen Intern Med 1999;14:49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Swanwick T. Informal learning in postgraduate medical education: from cognitivism to 'culturism'. Med Educ 2005;39:859–65. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lingard L, McDougall A, Levstik M, et al. . Representing complexity well: a story about teamwork, with implications for how we teach collaboration. Med Educ 2012;46:869–77. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04339.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wenger E. Communities of practice: learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baldwin DC, Daugherty SR. How residents say they learn: a national, Multi-Specialty survey of first- and second-year residents. J Grad Med Educ 2016;8:631–9. 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00182.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meltzer D, Chung J, Khalili P, et al. . Exploring the use of social network methods in designing healthcare quality improvement teams. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1119–30. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Distin K. The selfish Meme: a critical reassessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Acute Medicine Taskforce Acute medical care, 2007. Available: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/acute_medical_care_final_for_web.pdf [Accessed 07 Apr 2019].

- 11. Bell D, Skene H, Jones M, et al. . A guide to the acute medical unit. Br J Hosp Med 2008;69:M107–9. 10.12968/hmed.2008.69.Sup7.30432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heath H, Cowley S. Developing a grounded theory approach: a comparison of Glaser and Strauss. Int J Nurs Stud 2004;41:141–50. 10.1016/S0020-7489(03)00113-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Battistoni E, Fronzetti Colladon A. Personality correlates of key roles in informal advice networks. Learn Individ Differ 2014;34:63–9. 10.1016/j.lindif.2014.05.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Christakis NA, Fowler JH. Social contagion theory: examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Stat Med 2013;32:556–77. 10.1002/sim.5408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wagter JM, van de Bunt G, Honing M, et al. . Informal interprofessional learning: visualizing the clinical workplace. J Interprof Care 2012;26:173–82. 10.3109/13561820.2012.656773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Isba R, Woolf K, Hanneman R. Social network analysis in medical education. Med Educ 2017;51:81–8. 10.1111/medu.13152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shokoohi M, Nedjat S, Majdzadeh R. A social network analysis on clinical education of diabetic foot. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2013;12:44 10.1186/2251-6581-12-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jippes E, Achterkamp MC, Brand PLP, et al. . Disseminating educational innovations in health care practice: training versus social networks. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:1509–17. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chambers D, Wilson P, Thompson C, et al. . Social network analysis in healthcare settings: a systematic scoping review. PLoS One 2012;7:e41911 10.1371/journal.pone.0041911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fong A, Clark L, Cheng T, et al. . Identifying influential individuals on intensive care units: using cluster analysis to explore culture. J Nurs Manag 2017;25:384–91. 10.1111/jonm.12476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, et al. . Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med 2010;8:2–11. 10.1186/1741-7015-8-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027039supp001.pdf (34.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-027039supp002.pdf (30.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-027039supp003.pdf (34.4KB, pdf)