Abstract

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), Q fever, and Lyme disease are endemic to southern Kazakhstan, but population-based serosurveys are lacking. We assessed risk factors and seroprevalence of these zoonoses and conducted surveys for CCHF-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices in the Zhambyl region of Kazakhstan. Weighted seroprevalence for CCHF among all participants was 1.2%, increasing to 3.4% in villages with a known history of CCHF circulation. Weighted seroprevalence was 2.4% for Lyme disease and 1.3% for Q fever. We found evidence of CCHF virus circulation in areas not known to harbor the virus. We noted that activities that put persons at high risk for zoonotic or tickborne disease also were risk factors for seropositivity. However, recognition of the role of livestock in disease transmission and use of personal protective equipment when performing high-risk activities were low among participants.

Keywords: Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Q fever, Lyme disease, Coxiella burnetii, Borrelia burgdorferi, tickborne infections, vector-borne infections, zoonoses, One Health, livestock, Kazakhstan, bacteria, viruses

Zoonoses account for 61% of human infectious diseases and 75% of emerging pathogens (1). Zoonotic diseases pass from animals to humans through direct contact with animals, inhalation of infectious aerosols, consumption of contaminated animal products, or a bite from a vector, such as a tick (2). Global incidence of tickborne diseases is increasing and expected to continue rising (3). Given changes in ecologic factors, such as climate and land use, tickborne diseases have emerged in new areas during the past 3 decades, and the incidence of endemic tickborne pathogens has increased (4). Vectorborne infections were responsible for ≈28.8% of emerging infectious diseases during 1990–2000 (5).

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), Q fever, and Lyme disease are widespread zoonotic diseases that cause a range of illness and death in humans. CCHF, caused by Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV), an RNA virus of the family Nairoviridae, is highly fatal (6). The virus is maintained through an enzootic cycle involving mammals, ticks, and humans, and is transmitted to humans through contact with viremic livestock or infected ticks. CCHF is endemic to Africa, Asia, eastern and southern Europe, and central Asia (7). Q fever is caused by the bacterium Coxiella burnetii, which infects many vertebrates, but ruminant livestock are thought to be its primary reservoir. Transmission to humans most commonly occurs from inhalation of dust contaminated with urine, feces, milk, or birth products from infected animals (8). Q fever has been identified in most countries (8). Severe cases can result in pneumonia or hepatitis in humans, and ≈5% of infections become chronic (9). Lyme disease is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, a bacterium transmitted to humans through the bite of Ixodes ticks. Untreated Lyme infection can disseminate and spread to the joints, heart, and nervous system. Lyme disease is the most commonly reported arthropodborne disease in North America and is prevalent throughout central Europe, particularly Germany, Austria, and Slovenia (10,11). Lyme disease is the sixth most commonly reported notifiable infectious disease in the United States (https://www.cdc.gov/lyme). In addition, incidence of Lyme disease and the range of tick vectors have been increasing in Europe and Asia (10,11), where Lyme disease is found in western Russia, Mongolia, northeast China, and Japan.

CCHF, Q fever, and Lyme disease are endemic to the southern Kazakhstan region of Zhambyl, but their true burden is largely unknown because few serologic surveys have been conducted in Kazakhstan and central Asia. The Zhambyl region covers >55,000 km2 and has a population of ≈1.2 million. The region is characterized by diverse ecology, containing both desert steppes and mountainous pastures, and elevations of 213–4,115 m. The region has 363 villages and 4 cities. Livelihoods are largely pastoral or agricultural, and common occupations involve a high degree of animal contact, placing humans at increased risk for zoonotic infections.

Among the 3 diseases, only CCHF is a reportable disease in Kazakhstan. During 2000–2013, the Zhambyl region had 73 reported human CCHF cases, the second highest case-count among regions in Kazakhstan (12). However, data on human prevalence of CCHF in Kazakhstan are limited to reported clinical cases, even though studies show >80% of infections are subclinical (13). Although Q fever was detected in Kazakhstan in the 1950s, the lack of surveillance or serologic studies obscure our understanding of Q fever or Lyme disease incidence in the population (14). Quantifying seroprevalence of these diseases in humans can help identify areas of pathogen circulation and areas where humans could be infected.

For this study, we aimed to determine the seroprevalence of antibodies against CCHFV, C. burnetii, and B. burgdorferi in humans who interact with livestock in the Zhambyl region. In addition, we sought to assess the population’s knowledge of risk factors for disease transmission and how frequently they engage in activities that increase or reduce risk for infection.

Methods

In June 2017, we conducted a knowledge, attitudes, and practices and risk factor survey (KAP/risk factor survey), along with serosurveys for CCHF, Q fever, and Lyme disease, in 30 rural villages in the Zhambyl region. Participants could enroll in the KAP/risk factor survey, the serosurvey, or both. Eligible participants were >18 years of age, residents of the village for >2 months, and residents of a household containing a sheep or cow of >1 year of age.

Sample Size

Sample selection was based on concern about CCHF as a nationally reportable disease. We conducted surveys in households in which sheep and cattle serosurveys simultaneously were conducted; sample size calculations were based on expected seroprevalence of sheep and cattle. We calculated a target sample size of 561 households with sheep and 473 households with cattle. We based the sample size on an α of 0.05, power of 80%, a design effect of 2, and an expected response rate of 90%. We assumed CCHF seroprevalence of 24% in sheep and 19% in cattle, on the basis of a meta-analysis of previous serosurveys (15).

Participant Selection

We stratified the 363 villages in the region by known (CCHF-endemic) or unknown (non–CCHF-endemic) recent circulation of CCHF. We defined recent circulation as 1 confirmed human case reported in hospital-based surveillance from Zhambyl Oblast Health Department (Taraz, Kazakhstan) or 1 CCHF-positive tick confirmed in the previous 5 years and reported in annual tick surveillance data from the Ministry of Agriculture of Kazakhstan. We identified 66 (18.2%) villages that met the definition for having known, recent CCHF circulation.

We selected 15 villages from each stratum; probability of selection was proportional to the number of sheep and cattle in the village. We obtained livestock counts from reports by village veterinarians to the Ministry of Agriculture. Elevation of the 30 villages was 220–2,590 m (mean 781 m, median 488 m). Mean elevation was 513 m for villages with known CCHF circulation and 1,049 m for villages without known circulation.

Local veterinarians provided information on livestock-owning households in each village. To verify, data collectors conducted a census of 5 villages and mapped households containing sheep or cattle. The veterinarian registry was accurate except for 2 instances in which the household recently had sold animals. Survey teams randomly selected 35 households from these registries and 1 adult per household for study participation.

KAP/Risk Factor Survey

We adapted our KAP/risk factor survey from one conducted in Georgia during a 2014 CCHF outbreak (16). We translated the survey into Russian and Kazakh, the 2 most common languages in the region. Survey teams pilot tested the questionnaire in an eligible village not selected for the study.

The survey team administered the questionnaire verbally at each respondent’s residence. Survey questions covered demographics; occupations; history of animal and tick interactions; illness in the previous 4 months or fever and hemorrhaging; and knowledge of CCHF transmission routes, symptoms, and risk factors. The survey did not contain questions specific for Lyme disease or Q fever.

Serosurvey

After answering the questionnaire, respondents were asked to go to their local health clinic to provide a blood sample on the same day. Each village had a health clinic within walking distance of participants. Nurses drew 5 mL of blood from each participant and stored it in a serum separator tube. Blood samples were kept on ice, centrifuged within 6 h, and transported within 24 h to the Zhambyl Regional Laboratory for Especially Dangerous Pathogens in Taraz, where laboratorians aliquoted serum into 4 samples/participant and stored serum at −20°C until analysis.

Laboratorians analyzed samples for evidence of recent CCHF exposure, indicated by presence of IgM, by using VectoCrimean-CCHF-IgM Kits (Vector-Best, https://vector-best.ru) and for evidence of past CCHF exposure, indicated by IgG, by using VectoCrimean-CHF-IgG Kits (Vector-Best). Laboratorians assessed past exposure to C. burnetii, indicated by presence of IgG, using ELISA-Anti-Q Kit No. 1 (Pasteur Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology, http://www.pasteur-nii.spb.ru), and exposure to Borellia spp., indicated by presence of IgG against B. afzelii, B. garinii, or B. burgdorferi, by using LymeBest-IgG Test Kits (Vector-Best). All testing was performed with commercially available ELISA kits, according to manufacturer instructions (17,18).

Data Analysis

We analyzed data by using R version 3.4.3 (19). We weighted results for each participant by calculating the inverse probability of selection and applying a poststratification adjustment to each stratum to account for nonresponses. We stratified KAP/risk factor answers specific to CCHF according to whether the health department recognized the village as having known, recent history of CCHF. We used χ2 test in bivariate analysis to compare frequencies between these 2 strata. We used logistic regression models to test associations between risk factors and seropositivity. We defined risk for zoonotic or tickborne disease as participation in >1 of the following activities: handling ticks with bare hands; working with livestock; working in a healthcare setting; being a veterinarian; or herding, birthing, shearing, slaughtering, or milking animals.

Ethics Review

Each participant provided written, informed consent. No personal identifying information was collected. The Institutional Review Board in Almaty, Kazakhstan, through the Committee for Public Health Protection, approved the study. The protocol was reviewed according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention human subjects review procedures, which determined the agency was not engaged in the study because the Zhambyl Departments of Health and Agriculture owned and collected the data.

Results

KAP/Risk Factor Survey

We selected 969 households; 948 persons completed surveys, a 98% response rate. Reasons for nonresponse included 4 households that were not visited, 2 that were abandoned, and 1 that was not found. In addition, 12 persons did not consent: 4 did not want to participate in the serosurvey, 1 did not have time, 1 distrusted the data team, and 6 gave no reason. Further, 2 persons were excluded from analysis because information on their village of residence was missing and they could not be analyzed according to survey design.

Respondents’ median age was 46 (range 19–90) years; 54% were male (Table 1). Most (66.7%) were native to Kazakhstan. The most frequently reported occupations were taking care of the home (23.0%) and farming or herding (20.8%).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study population in survey of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Kazakhstan.

| Patient characteristics | Median (IQR) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 46 (36–56) | 19–90 |

| Household size | 6.1 (4.6–8.4) | 2.7–21.6 |

| Land owned, ha | 0.18 (0.12–0.25) | 0.004–776 |

| Land rented, ha |

0.20 (0.14–0.90) |

0.024–776 |

| No. animals owned | ||

| Ovine | 15.0 (3.0–35.0) | 0–1,320 |

| Bovine | 2.0 (1.0–5.0) | 0–141 |

| Poultry | 0 (0–8.0) | 0–80 |

| Equine | 0 (0–1.0) |

0–100 |

|

|

No. participants |

% Participants (95% CI) |

| Sex | ||

| M | 509 | 56.1 (50.5–61.5) |

| F |

437 |

43.9 (38.5–49.5) |

| Country of origin | ||

| Kazakhstan | 733 | 66.7 (44.0–85.9) |

| Russia | 73 | 10.5 (4.4–23.0) |

| Turkey | 45 | 4.4 (1.9–9.2) |

| Kyrgyzstan | 3 | 0.6 (0.2–1.9) |

| Uzbekistan | 3 | 0.4 (0.1–2.1) |

| Other |

89 |

15.7 (4.0–45.7) |

| Occupation | ||

| Farmer, herder, animal tender | 163 | 20.8 (10.1–38.1) |

| Gardener, fieldworker | 50 | 3.1 (1.3–7.4) |

| Butcher | 1 | 0.001 (0–0.01) |

| Healthcare worker | 21 | 2.5 (1.5–4.1) |

| Veterinarian | 15 | 1.5 (0.6–4.1) |

| Office, indoor worker | 153 | 14.0 (9.0–21.1) |

| Family or home caretaker | 179 | 23.0 (18.4–28.5) |

| Student | 10 | 1.1 (0.4–3.1) |

| Retired | 147 | 9.8 (6.3–14.9) |

| Unemployed | 105 | 14.3 (5.8–31.0) |

| Other |

101 |

9.9 (3.4–25.6) |

| Education level | ||

| None | 12 | 0.1 (0.03–0.5) |

| Elementary school | 9 | 0.8 (0.3–2.0) |

| Middle school | 437 | 44.1 (33.9–54.9) |

| High school | 159 | 11.5 (7.5–17.2) |

| Vocational school | 71 | 4.1 (1.7–9.5) |

| College |

251 |

38.9 (28.3–50.8) |

| Monthly income, US $ | ||

| <60 | 43 | 4.0 (1.3–11.4) |

| 61–150 | 373 | 39.1 (24.6–55.8) |

| 151–300 | 257 | 26.8 (20.1–34.6) |

| 301–450 | 34 | 0.8 (0.2–3.0) |

| 451–600 | 9 | 0.5 (0.1–2.1) |

| >600 | 7 | 0.2 (0.04–1.1) |

| Unknown, refused to answer | 222 | 28.6 (12.6–52.6) |

Of respondents, 64.4% (95% CI 50.9%–75.8%) reported participating in >1 activity putting them at elevated risk for zoonotic or tickborne disease during their lives; 55.4% (95% CI 42.8%–67.3%) reported doing so in the previous 4 months (Table 2). Of high-risk activities, butchering or handling raw meat (36.4%) and shearing (26.0%) or herding (25.8%) animals were most common. Of respondents, 139 (22%) who birthed animals in the previous 4 months and 222 (47.4%) who slaughtered an animal in the previous 4 months wore no personal protective equipment (PPE). Few respondents reported tick bites (Table 3), but >85% said ticks were a major problem (Table 4). Most respondents (93.6%) reported killing ticks with an object; only 0.5% reported killing ticks with bare hands. Most (94.0%) used pesticide to prevent ticks on animals.

Table 2. Participation in activities putting them at high risk for tickborne zoonotic diseases among respondents in survey of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Kazakhstan*.

| Activities | No. respondents | % Respondents (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Herding animals | ||

| Ever | 297 | 17.4 (8.4–32.5) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

190 |

25.8 (14.3–42.2) |

| Assisting with animal births | ||

| Ever | 226 | 11.3 (6.8–18.3) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

140 |

5.9 (3.5–9.9) |

| Shearing animals | ||

| Ever | 331 | 26.0 (19.7–33.4) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

223 |

17.0 (12.9–22.1) |

| Milking animals | ||

| Ever | 316 | 23.2 (16.3–31.9) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

251 |

18.9 (12.8–27.0) |

| Slaughtering animals | ||

| Ever | 292 | 25.4 (15.8–38.1) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

229 |

20.4 (12.0–32.4) |

| Butchering or handling raw meat | ||

| Ever | 351 | 36.4 (28.4–45.2) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

296 |

30.7 (22.7–40.0) |

| Eating raw meat | ||

| Ever | 8 | 0.5 (0.1–1.9) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

0 |

– |

| Handling ticks with bare hands | ||

| Ever | 61 | 3.5 (1.1–10.3) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

27 |

2.0 (0.4–8.4) |

| Working in a healthcare setting | ||

| Ever | 5 | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

3 |

0.2 (0–0.8) |

| Working in a garden† | ||

| Ever | 175 | 14.5 (7.6–27.4) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

150 |

12.4 (6.5–22.6) |

| Consuming unpasteurized milk or dairy products‡ | ||

| Ever | 8 | 1.0 (0.4–2.2) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

0 |

– |

| Participated in >1 high-risk activity | ||

| Ever | 683 | 64.4 (50.9–75.8) |

| Within the previous 4 mo |

580 |

55.4 (42.8–67.3) |

| Use of personal protective equipment | ||

| Assisting with animal births, n = 139† | ||

| Gloves | 73 | 55.2 (35.8–73.1) |

| Gown | 43 | 55.1 (30.3–77.6) |

| Boots | 21 | 30.0 (11.8–58.0) |

| Glasses | 3 | 12.7 (2.0–51.5) |

| None | 46 | 20.4 (11.0–34.7) |

| Shearing animals, n = 222† | ||

| Gloves | 172 | 83.6 (71.7–91.2) |

| Gown | 119 | 73.9 (55.9–86.4) |

| Boots | 59 | 20.6 (12.2–32.6) |

| Glasses | 4 | 2.9 (0.7–11.4) |

| None | 21 | 5.2 (1.7–15.2) |

| Milking animals, n = 250† | ||

| Gloves | 26 | 15.5 (5.5–36.8) |

| Gown | 178 | 81.6 (60.6–92.7) |

| Boots | 12 | 5.7 (2.2–14.1) |

| None | 71 | 17.5 (6.4–39.5) |

| Slaughtering animals, n = 229† | ||

| Gloves | 36 | 23.3 (10.5–44.1) |

| Gown | 91 | 49.1 (33.6–64.8) |

| Boots | 16 | 5.2 (2.0–12.9) |

| Glasses | 1 | 1.6 (0.2–9.4) |

| None |

129 |

47.4 (29.8–65.7) |

| *Percentages weighted by calculating the inverse probability of selection and applying a post-stratification adjustment to each stratum to account for nonresponses. †>1 response possible. ‡Not considered a high-risk activity. | ||

Table 3. Interactions with ticks among respondents in survey of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Kazakhstan*.

| Human–tick interactions | No. respondents | % Respondents (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Had a tick bite† | 17 | 1.0 (0.3–3.3) |

| Handled tick with bare hands† |

61 |

3.5 (1.1–10.3) |

| Method of tick disposal after bare hand removal, n = 27 | ||

| Threw it out | 1 | 3.2 (0.3–29.3) |

| Killed with bare hands† | 1 | 0.5 (0–5.9) |

| Killed with object | 16 | 93.6 (69.2–99.0) |

| Burned it |

10 |

3.5 (0.6–18.8) |

| Number of tick bites in previous 4 mo |

0 |

0 |

| Method of human tick bite prevention‡ | ||

| None | 133 | 9.3 (3.9–20.8) |

| Long, layered clothing | 694 | 68.8 (55.2–79.9) |

| Gloves | 588 | 73.1 (60.5–82.9) |

| Pesticides in environment | 267 | 13.8 (7.9–22.9) |

| Insect repellent on self, clothing | 155 | 17.7 (10.0–29.3) |

| Avoiding woody areas | 133 | 12.2 (4.1–31.0) |

| Avoiding unnecessary animal contact |

111 |

13.9 (5.0–33.3) |

| Animal–tick interactions | ||

| Found ticks on livestock | 486 | 29.7 (19.6–42.3) |

| Primary method used to remove ticks on livestock | ||

| Bare hands† | 12 | 4.3 (1.2–15.0) |

| Gloved hands | 95 | 29.8 (15.9–48.7) |

| With an object | 291 | 51.7 (34.0–69.0) |

| Go to a clinic | 15 | 3.3 (1.2–8.7) |

| Pour liquid mixture on animal | 32 | 3.0 (1.2–7.1) |

| Burn the tick | 6 | 0.7 (0.2–2.2) |

| Leave the tick | 31 | 6.8 (2.6–16.3) |

| Use tick medication for animals | 905 | 94.0 (76.0–98.8) |

*Percentage weighted by calculating the inverse probability of selection and applying a poststratification adjustment to each stratum to account for nonresponses. †High-risk tick interaction. ‡>1 response possible.

Table 4. Comparison of respondent attitudes between CCHF-endemic villages and non–CCHF-endemic villages in survey of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Kazakhstan* .

| Attitudes |

CCHF-endemic, n = 442 |

Non–CCHF-endemic, n = 506 |

p value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. respondents† |

% Respondents (95% CI) |

|

No. respondents† |

% Respondents (95% CI) |

||

| Among all persons | ||||||

| Ticks are a problem in the community | 0.05 | |||||

| Major problem | 410 | 95.3 (89.9–97.9) | 408 | 86.6 (67.8–95.2) | ||

| Minor problem | 4 | 0.7 (0.2–3.0) | 13 | 2.1 (0.8–5.6) | ||

| Not a problem | 3 | 0.6 (0.1–3.1) | 52 | 5.0 (1.0–21.9) | ||

| Don’t know | 23 | 3.4 (1.2–9.0) | 33 | 6.4 (2.7–14.4) | ||

| People in my community frequently get bitten by ticks | 0.74 | |||||

| Often | 245 | 49.0 (19.4–79.3) | 187 | 33.5 (12.2–64.7) | ||

| Occasionally | 24 | 7.4 (1.3–32.2) | 94 | 13.3 (5.4–29.4) | ||

| Rarely | 149 | 40.4 (17.7–68.1) | 202 | 50.2 (20.7–79.5) | ||

| Don’t know |

22 |

3.2 (1.4–7.2) |

|

23 |

3.0 (0.7–12.1) |

|

| Among persons who have heard of CCHF |

n = 420 |

|

n = 371 |

|

||

| CCHF is a problem in the community | 0.12 | |||||

| Major problem | 401 | 96.2 (90.0–98.6) | 326 | 93.7 (82.7–97.9) | ||

| Minor problem | 3 | 0.7 (0.2–3.1) | 9 | 1.9 (0.5–6.6) | ||

| Not a problem | 1 | 0.1 (0–0.5) | 26 | 2.7 (0.5–13.5) | ||

| Don’t know | 15 | 3.0 (1.1–8.4) | 10 | 1.7 (0.5–6.1) | ||

| CCHF is something I should be worried about | 0.01 | |||||

| Very worried | 371 | 86.1 (72.5–93.5) | 317 | 93.6 (83.5–97.7) | ||

| Somewhat worried | 40 | 11.5 (4.2–27.8) | 19 | 2.6 (0.9–7.4) | ||

| Not worried | 1 | 0.02 (0–0.2) | 25 | 2.5 (0.4–13.9) | ||

| Don’t know | 8 | 2.4 (0.4–12.4) | 10 | 1.2 (0.2–7.1) | ||

| I can protect myself from CCHF | <0.01 | |||||

| Yes | 380 | 90.5 (82.5–95.0) | 191 | 52.5 (33.6–70.6) | ||

| No | 4 | 0.7 (0.2–3.2) | 100 | 22.7 (8.3–48.8) | ||

| Don’t know | 36 | 8.9 (4.2–17.9) | 80 | 24.8 (12.6–43.0) | ||

| I would welcome a CCHF survivor into my community | 379 | 89.2 (79.7–94.5) | 348 | 94.2 (87.9–97.4) | 0.17 | |

*CCHF, Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever. †Percentage weighted by calculating the inverse probability of selection and applying a poststratification adjustment to each stratum to account for nonresponses.

Participants from CCHF-endemic villages had a higher knowledge of CCHF, likely because the health department provided education in these villages (Table 5). Most respondents (95.6%, 95% CI 93.8%–99.9%) in CCHF-endemic villages had heard of CCHF, compared with only 71.3% (95% CI 61.7%–79.3%) in non–CCHF-endemic villages (Table 5). Information from healthcare workers, pamphlets, and village meetings were common ways participants learned about CCHF. In addition, 95.8% (95% CI 89.8%–98.3%) of respondents in CCHF-endemic villages who knew about CCHF could recognize >1 high-risk activity, compared with 75.9% (95% CI 49.1%–91.1%) in non–CCHF-endemic villages. Most recognized tick bites as a mode of transmission, and >10% in CCHF-endemic villages recognized animal blood as a potential mode of transmission. Despite a lower disease knowledge in non–CCHF-endemic villages, respondents thought CCHF was a major problem (Table 4), but only 52.5% felt prepared to protect themselves from CCHF, compared with 90.5% from CCHF-endemic villages.

Table 5. Comparison of participant knowledge of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever between CCHF-endemic villages and non–CCHF-endemic villages, Kazakhstan*.

| Information about CCHF |

CCHF-endemic villages, n = 442 |

|

Non–CCHF-endemic villages, n = 506 | p value |

| No. participants† | % Participants (95% CI) | No. participants† | % Participants (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heard of CCHF | 420 | 95.6 (93.8–99.9) | 371 | 2.0 (61.7–79.3) | <0.001 | |

| Source* | n = 420 | n = 371 | ||||

| Village, community meetings | 262 | 62.1 (28.0–87.3) | 110 | 46.9 (16.2–80.1) | ||

| School | 77 | 18.9 (8.8–35.9) | 25 | 4.1 (1.5–11.1) | ||

| Television | 196 | 60.5 (42.7–75.9) | 333 | 87.4 (77.9–93.2) | ||

| Radio | 34 | 8.1 (3.7–16.7) | 10 | 2.1 (0.7–6.1) | ||

| Newspaper, magazine | 153 | 43.6 (28.7–59.6) | 117 | 32.7 (25.1–41.3) | ||

| Pamphlets | 240 | 72.5 (51.2–86.9) | 248 | 79.5 (61.7–90.3) | ||

| Posters | 225 | 69.6 (43.8–87.0) | 185 | 66.1 (45.9–81.8) | ||

| Education campaign | 18 | 4.0 (1.3–11.4) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Training course | 3 | 90.6 (0.1–3.4) | 7 | 2.8 (0.9–8.6) | ||

| Healthcare worker | 329 | 89.0 (78.8–94.6) | 175 | 62.0 (31.2–85.5) | ||

| Know someone with CCHF | 12 | 3.2 (1.2–8.5) | 30 | 4.7 (3.1–7.0) | ||

| Other, friend, family member |

8 |

2.2 (0.7–6.9) |

|

1 |

1.0 (0.2–5.5) |

|

| Transmission | ||||||

| Tick bite | 415 | 99.6 (98.5–99.9) | 367 | 99.4 (97.8–99.9) | ||

| Mosquito bite | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Flea bite | 5 | 0.05 (0–0.4) | 3 | 0.4 (0.1–2.7) | ||

| Crushing tick with bare hands | 218 | 53.8 (21.4–83.3) | 96 | 31.3 (15.5–53.0) | ||

| Contact with blood from an infected animal | 50 | 9.10 (3.5–21.7) | 91 | 21.0 (7.1–48.1) | ||

| Contact with birthing tissue of infected animal | 16 | 2.0 (0.6–6.4) | 66 | 16.1 (5.1–40.7) | ||

| Eating or touching raw meat of infected animal | 12 | 1.3 (0.4–4.5) | 49 | 12.4 (4.1–32.0) | ||

| Contact with blood from infected human | 186 | 41.6 (28.2–56.3) | 183 | 45.0 (30.2–60.9) | ||

| Contact with persons sick with CCHF | 135 | 37.8 (19.3–60.6) | 204 | 67.9 (47.3–83.3) | ||

| Unpasteurized milk | 7 | 0.3 (0.1–1.7) | 10 | 1.9 (0.5–7.3) | ||

| Correctly identified >1 transmission route |

413 |

99.6 (98.5–99.9) |

|

367 |

99.6 (97.8–99.9) |

0.90 |

| High-risk activities | ||||||

| Working with livestock | 386 | 94.7 (86.6–98.0) | 168 | 52.8 (30.4–74.1) | ||

| Gardening or fieldwork | 144 | 50.1 (27.5–72.7) | 89 | 30.4 (17.0–48.2) | ||

| Being in a woody area | 115 | 30.6 (13.0–56.5) | 152 | 55.1 (33.6–74.9) | ||

| Crushing ticks with bare hands | 261 | 62.2 (30.8–85.8) | 132 | 39.3 (26.4–53.9) | ||

| Shearing animals | 231 | 53.7 (29.0–76.7) | 102 | 37.2 (18.4–60.7) | ||

| Butchering meat | 79 | 16.7 (7.4–33.6) | 50 | 14.7 (5.0–35.9) | ||

| Working in healthcare | 67 | 14.3 (5.6–31.8) | 51 | 6.4 (4.1–9.7) | ||

| Slaughtering animals | 35 | 7.5 (3.8–14.3) | 17 | 4.1 (1.6–10.2) | ||

| Being a veterinarian | 120 | 28.5 (12.7–52.1) | 76 | 29.1 (11.2–57.2) | ||

| Contact with sick humans | 222 | 55.2 (33.8–74.8) | 266 | 77.8 (66.6–86.1) | ||

| Don’t know | 9 | 0.8 (0.2–3.0) | 2 | 0.04 (0–0.3) | ||

| Correctly identified at >1 high-risk activity |

378 |

95.8 (89.8–98.3) |

|

248 |

75.9 (49.1–91.1) |

0.001 |

| Signs and symptoms in humans | ||||||

| Fever | 398 | 96.8 (92.7–98.6) | 312 | 93.0 (79.4–97.8) | ||

| Headache | 302 | 74.5 (44.0–91.6) | 297 | 88.7 (71.0–96.2) | ||

| Nausea, vomiting | 183 | 55.8 (36.8–73.2) | 86 | 25.0 (13.8–41.1) | ||

| Diarrhea | 75 | 22.4 (12.4–37.2) | 59 | 20.3 (11.6–33.3) | ||

| Muscle pain | 190 | 48.0 (26.1–70.6) | 81 | 19.3 (8.5–38.1) | ||

| Joint pain | 222 | 59.8 (46.3–72.1) | 158 | 47.6 (32.7–62.9) | ||

| Fatigue | 224 | 66.3 (52.8–77.6) | 240 | 66.0 (51.5–77.9) | ||

| Cough, respiratory involvement | 53 | 12.9 (5.1–29.0) | 26 | 5.6 (1.3–21.6) | ||

| Congestion | 110 | 27.2 (14.6–44.8) | 15 | 4.5 (1.4–13.4) | ||

| Bruising | 115 | 27.7 (15.2–45.1) | 59 | 10.1 (4.4–21.4) | ||

| Bleeding, hemorrhage | 251 | 57.2 (42.6–70.7) | 129 | 26.4 (15.3–41.7) | ||

| Red eyes | 55 | 14.1 (7.5–24.9) | 6 | 0.6 (0.2–2.3) | ||

| Coma | 21 | 4.6 (2.1–10.0) | 3 | 0.3 (0.1–1.7) | ||

| Death | 73 | 17.0 (6.8–36.4) | 13 | 1.2 (0.3–4.7) | ||

| Don’t know | 19 | 1.5 (0.5–4.6) | 10 | 0.7 (0.1–3.9) | ||

| Correctly identified >1 symptom in humans |

395 |

98.0 (94.6–99.3) |

|

346 |

97.0 (90.6–99.1) |

0.57 |

| Signs and symptoms in animals | ||||||

| None (correct response) | 69 | 20.0 (3.4–64.0) | 35 | 16.0 (2.0–64.3) | 0.84 | |

| Fever | 149 | 36.5 (10.5–73.9) | 203 | 44.0 (14.9–78.0) | ||

| Aggression, agitation | 64 | 13.3 (4.7–32.6) | 130 | 31.1 (10.3–63.8) | ||

| Vomiting | 84 | 27.2 (7.1–64.6) | 30 | 7.0 (1.3–30.9) | ||

| Lethargy | 87 | 23.0 (6.6–56.0) | 151 | 28.5 (10.2–58.3) | ||

| Abortion, stillbirth | 77 | 20.5 (6.1–50.4) | 46 | 9.8 (2.7–29.9) | ||

| Reduced appetite | 75 | 22.1 (6.3–54.4) | 145 | 33.0 (11.8–64.3) | ||

| Hair loss | 60 | 16.3 (4.6–44.0) | 34 | 7.2 (1.5–28.5) | ||

| Weight loss | 55 | 15.3 (4.2–42.3) | 38 | 6.6 (1.3–26.6) | ||

| Reduced milk production | 54 | 15.7 (4.8–41.0) | 26 | 5.0 (1.3–17.5) | ||

| Respiratory problems | 29 | 7.7 (2.4–21.8) | 18 | 2.2 (0.5–9.4) | ||

| Bleeding, hemorrhage | 52 | 11.1 (3.6–28.9) | 47 | 9.4 (3.2–24.7) | ||

| Eye problems | 13 | 3.1 (0.6–15.2) | 3 | 0.3 (0.04–2.7) | ||

| Death | 12 | 1.3 (0.4–3.8) | 2 | 0.2 (0.04–1.1) | ||

| Don’t know | 71 | 13.8 (5.4–30.7) | 2 | 1.0 (0.2–5.4) | ||

*>1 response possible in each category. CCHF, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. †Percentage weighted by calculating the inverse probability of selection and applying a post-stratification adjustment to each stratum to account for nonresponses.

Serosurveys

Of 948 persons completing the KAP/risk factor survey, 914 (96.4%) submitted blood samples. Of 34 persons who did not participate in the serosurvey, 10 did not show up for a blood draw, 4 did not have time, 2 feared needles, 1 feared consequences of detection, 1 had recent surgery, and 16 reported no reasons. Serum from 914 samples was tested for evidence of CCHF. In addition, 911 samples were tested for Lyme disease, 910 were tested for Q fever, and 4 did not have adequate sample volume for Lyme disease and Q fever testing.

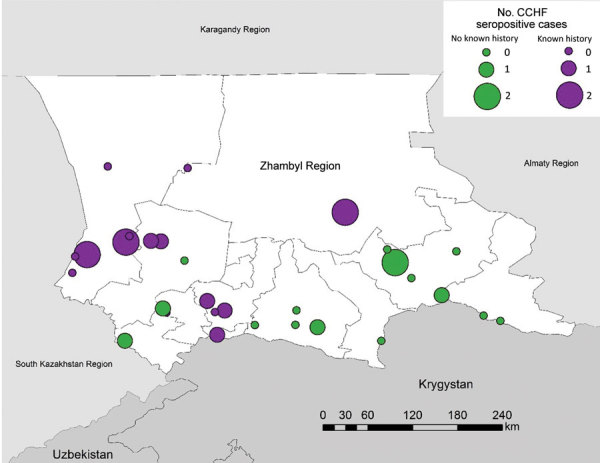

Of 914 persons tested for CCHFV, 3 were positive for IgM, 12 for IgG, and 2 were positive for both (Table 6). Among livestock owners in the Zhambyl region, weighted CCHFV seroprevalence was 1.2% (95% CI 0.5%–2.7%). In CCHF-endemic villages, seroprevalence was 3.4% (95% CI 1.8%–6.43%), compared with 0.9% (95% CI 0.3%–2.7%) in non–CCHF-endemic villages. We found evidence of recent or past CCHFV exposure in persons from 13/30 (43.3%) villages (Figure 1).

Table 6. Characteristics of persons seropositive for 3 tickborne diseases, Kazakhstan*.

| Characteristics | CCHF (17/914) |

Lyme (27/911) |

Q fever (11/910) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR |

Range | Median | IQR |

Range | Median |

IQR |

Range | |||||||

| Age, y | 54.0 | 42.0–58.0 | 21.0–68.0 | 40.0 | 32.0–46.5 | 23.0–76.0 | 50.0 | 36.5–56.5 | 25.0–72.0 | ||||||

| Household size | 6.1 | 4.7–6.7 | 3.9–13.3 | 5.2 | 4.1–6.6 | 2.8–12.4 | 5.2 | 4.9–6.2 | 4.7–13.3 | ||||||

| Land ownership, ha |

0.15 |

0.12–0.20 |

0.01–5.0 |

|

0.2 |

0.13–0.25 |

0.03–9.0 |

|

0.2 |

0.1–0.3 |

0–5 |

||||

| Animals owned, no. | |||||||||||||||

| Ovine | 7.0 | 0–20.0 | 0–200 | 15.0 | 6.0–29.5 | 0–127 | 13.0 | 1.0–39.5 | 0–105 | ||||||

| Bovine | 2.0 | 2.0–5.1 | 0–8.0 | 2.0 | 2.0–4.0 | 0–10 | 3.0 | 2.5–4.0 | 0–12 | ||||||

| Poultry | 0 | 0–3.0 | 0–23 | 0 | 0–7.5 | 0–32 | 0 | 0–11 | 0–34 | ||||||

| Equids | 0 |

0 |

0–2.0 |

|

0 |

0–1.5 |

0–15 |

|

0 |

0–1.5 |

0–6 |

||||

|

|

No. persons |

% Persons (95% CI) |

No. persons |

% Persons (95% CI) |

No. persons |

% Persons (95% CI) |

|||||||||

| Total |

17 |

1.2 (0.5–2.7) |

|

27 |

2.4 (1.2–4.6) |

|

11 |

1.3 (0.3–5.0) |

|||||||

| Village type | |||||||||||||||

| CCHF-endemic | 11 | 3.4 (1.7–6.4) | 13 | 2.0 (0.7–5.9) | 3 | 0.1 (0.02–0.9) | |||||||||

| Non–CCHF-endemic |

6 |

0.9 (0.3–2.7) |

|

14 |

2.5 (1.1–5.2) |

|

8 |

1.5 (0.4–5.9) |

|||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||||

| M | 10 | 70.8 (31.9–92.6) | 18 | 70.1 (42.5–88.2) | 5 | 35.4 (26.8–44.9) | |||||||||

| F |

7 |

29.2 (7.4–68.1) |

|

9 |

29.9 (11.8–57.5) |

|

6 |

64.6 (55.1–73.1) |

|||||||

| Country of origin | |||||||||||||||

| Kazakhstan | 14 | 70.3 (24.6–94.5) | 24 | 89.1 (42.8–98.9) | 7 | 96.7 (46.8–99.9) | |||||||||

| Russia | 2 | 10.5 (1.6–45.4) | 1 | 0.2 (0–2.3) | 4 | 3.3 (0.1–53.2) | |||||||||

| Turkey | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 (0–0.7) | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Other |

1 |

19.1 (1.7–75.6) |

|

1 |

10.7 (1.0–57.7) |

|

0 |

0 |

|||||||

| Occupation | |||||||||||||||

| Farmer, herder, animal tender | 2 | 24.2 (3.6–73.5) | 5 | 27.2 (6.0–68.6) | 1 | 1.0 (0–36.6) | |||||||||

| Gardener, fieldworker | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.2 (0–2.3) | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Healthcare worker | 1 | 3.2 (0.3–28.3) | 1 | 4.4 (0.4–34.2) | 1 | 7.3 (0.1–81.4) | |||||||||

| Veterinarian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 (0–0.7) | 0 | – | |||||||||

| Office, indoor worker | 1 | 5.4 (0.6–34.2) | 7 | 32.1 (7.0–74.7) | 1 | 7.3 (0.1–81.4) | |||||||||

| Family or household caretaker | 3 | 11.4 (2.9–35.7) | 3 | 0.9 (0.1–7.4) | 4 | 53.7 (17.8–86.1) | |||||||||

| Student | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Retired | 5 | 13.6 (3.8–38.7) | 2 | 10.2 (1.1–54.4) | 1 | 1.3 (0–43.9) | |||||||||

| Unemployed | 4 | 40.0 (9.8–80.3) | 4 | 20.6 (5.1–55.4) | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Other |

1 |

2.2 (0.2–17.9) |

|

3 |

4.4 (1.2–14.9) |

|

3 |

29.5 (14.8–50.2) |

|||||||

| Education level | |||||||||||||||

| None | 1 | 0.02 (0–0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 (0–14.0) | |||||||||

| Elementary school | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Middle school | 5 | 53.9 (18.4–85.8) | 10 | 35.8 (9.6–74.7) | 4 | 87.4 (19.0–99.5) | |||||||||

| High school | 3 | 10.9 (2.6–36.4) | 5 | 4.1 (1.0–15.8) | 2 | 10.2 (0.3–80.4) | |||||||||

| Vocational school | 1 | 0.9 (0.1–8.3) | 1 | 1.1 (0.1–9.2) | 1 | 0.5 (0–14.0) | |||||||||

| College |

7 |

34.3 (8.4–74.8) |

|

11 |

58.9 (25.0–86.0) |

|

2 |

1.0 (0–18.9) |

|||||||

| Monthly income, US $ | |||||||||||||||

| <60 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.6 (0.2–23.4) | 2 | 1.0 (0–38.9) | |||||||||

| 61–150 | 10 | 53.7 (17.5–86.3) | 9 | 26.9 (5.9–68.5) | 3 | 31.0 (16.9–49.9) | |||||||||

| 151–300 | 4 | 35.0 (7.5–78.0) | 11 | 55.2 (20.0–85.9) | 1 | 7.3 (0.1–81.4) | |||||||||

| 301–450 | 1 | 0.5 (0.1–5.3) | 1 | 0.6 (0.1–5.2) | 1 | 0.3 (0–9.3) | |||||||||

| 451–600 | 0 | – | 1 | 0.6 (0.1–5.2) | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Don’t know, refused |

2 |

10.9 (1.2–55.8) |

|

4 |

14.0 (2.2–54.2) |

|

3 |

60.3 (41.6–76.4) |

|||||||

| Length of time in village | |||||||||||||||

| Whole life | 15 | 76.9 (27.0–96.8) | 23 | 76.9 (27.0–96.8) | 6 | 42.2 (14.6–75.7) | |||||||||

| >5 y | 1 | 4.0 (0.3–33.6) | 1 | 4.0 (0.3–33.7) | 1 | 52.5 (16.1–86.5) | |||||||||

| 4 mo–5 y | 1 | 19.1 (1.8–75.6) | 2 | 19.1 (1.8–75.6) | 3 | 2.3 (0–60.1) | |||||||||

| 2–<4 mo |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

1 |

2.9 (0–65.7) |

|||||||

| Activities participated in during lifetime | |||||||||||||||

| Herding animals | 8 | 28.9 (10.6–58.1) | 10 | 17.7 (3.9–53.1) | 4 | 34.4 (26.3–43.6) | |||||||||

| Assisting with animal births | 6 | 31.8 (6.7–75.2) | 7 | 5.8 (1.5–20.6) | 4 | 9.1 (0.3–79.0) | |||||||||

| Shearing animals | 5 | 12.6 (3.7–35.2) | 13 | 27.9 (9.7–58.3) | 6 | 35.9 (26.8–46.1) | |||||||||

| Milking animals | 8 | 28.3 (8.0–64.1) | 9 | 22.0 (5.7–56.8) | 4 | 15.6 (0.3–92.8) | |||||||||

| Slaughtering animals | 6 | 35.6 (7.9–78.1) | 9 | 19.5 (4.6–54.6) | 5 | 34.9 (26.5–44.5) | |||||||||

| Butchering, handling raw meat | 5 | 34.7 (7.5–77.9) | 11 | 33.3 (9.8–69.6) | 5 | 30.6 (16.3–49.9) | |||||||||

| Eating raw meat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Handling ticks with bare hands | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1.2 (0.2–7.1) | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Having tick on body | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Working in healthcare | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.4 (0.4–34.2) | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Working in garden† | 1 | 2.2 (0.2–17.9) | 3 | 10.0 (1.0–54.6) | 3 | 1.6 (0.1–33.1) | |||||||||

| Consuming unpasteurized dairy† | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

|

>1 high risk activity |

15 |

90.9 (60.3–98.5) |

|

21 |

53.5 (18.6–85.1) |

|

9 |

46.2 (14.0–81.9) |

|||||||

| Activities without personal protective equipment‡ | |||||||||||||||

| Birthing animals | 1 | 8.3 (0.7–55.0) | 2 | 73.6 (25.4–93.8) | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Shearing animals | 1 | 6.7 (0.4–54.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Milking animals | 1 | 2.3 (0.2–24.0) | 2 | 39.7 (3.6–92.8) | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Slaughtering animals |

4 |

83.3 (20.9–98.9) |

|

3 |

14.0 (1.7–61.0) |

|

2 |

77.3 (42.0–99.6) |

|||||||

| Illness with hemorrhaging and fever, ever | 0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.5 (0–14.0) |

|||||||||

*CCHF, Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever. †Not considered a high-risk activity. ‡No. participants who participated in this activity at any time.

Figure 1.

Number of CCHF-seropositive cases in villages included in serologic survey for tickborne diseases, Zhambyl region, Kazakhstan. Circle size denotes the number of IgG antibody–positive serology results indicating past exposure or IgM antibody–positive serology results indicating recent exposure to CCHF. Purple circles indicate that the village had previous known history of CCHF; green circles indicate the village had no known history of CCHF. CCHF, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever.

Of the 17 persons seropositive for CCHFV, median age was 54 years; 58% were male (Table 6). No persons reported previous CCHF diagnosis or illness with fever and hemorrhaging in the previous 5 years or a tick bite or handling ticks with bare hands in the previous 4 months. Occupations among the 17 seropositive persons were farmer or herder (n = 2), healthcare worker (n = 1), office or indoor worker (n = 1), homemaker (n = 5), retired (n = 3), unemployed (n = 4), and other (guard; n = 1).

Of 5 participants with evidence of recent exposure to CCHFV, 4 reported participating in >1 high-risk activity in the previous 4 months: 3 milked animals, 2 helped birth animals, 1 sheared animals, and 1 slaughtered animals. One participant reported experiencing an illness with joint pain in the previous 4 months. Three were from non–CCHF-endemic villages, which could suggest a wider range of virus circulation than previously thought.

In logistic regression, controlling for age and sex, participation in >1 high-risk activity had a statistically significant association with IgG or IgM seropositivity (adjusted OR [aOR] 5.6, 95% CI 1.1–29.7). Being >50 years of age was associated with having a history of infection but was not a risk factor for incident infection. Villages at lower elevations were more likely to have >1 person seropositive for CCHFV in logistic regression, but the association was not statistically significant (p = 0.41).

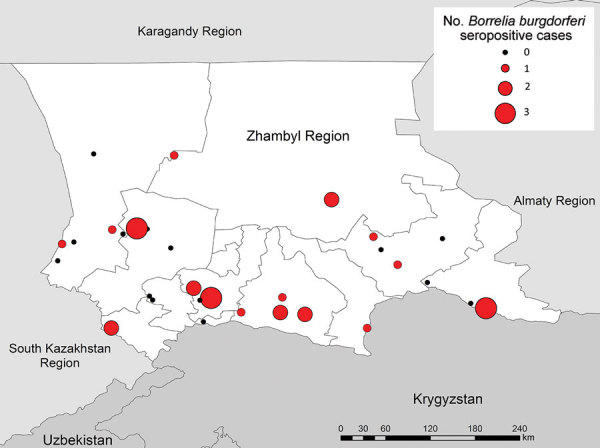

Of 911 participant samples tested for Lyme disease, 27 showed evidence of past exposure by IgG against tickborne borrelioses (Table 6). Weighted seroprevalence in the Zhambyl region was 2.4% (95% CI 1.2%–4.6%). We detected seropositive participants in 16/30 (53.3%) villages (Figure 2); occupations were farmer or herder (n = 5), gardener or fieldworker (n = 1), healthcare worker (n = 1), veterinarian (n = 1), office or indoor worker (n = 9), retired (n = 2), homemaker (n = 3), unemployed (n = 4), and other (geologist; n = 1) (Table 6). We did not identify specific activities statistically associated with seropositivity for Lyme disease, but we identified participants who were seropositive, even in a village at 2,590 m, an elevation at which the disease had not been reported in Kazakhstan.

Figure 2.

Number of Borrelia burgdorferi–seropositive cases in villages included in serologic survey for tickborne diseases, Zhambyl region, Kazakhstan. Circle size denotes the number of IgG antibody–positive serology results indicating past exposure to B. burgdorferi.

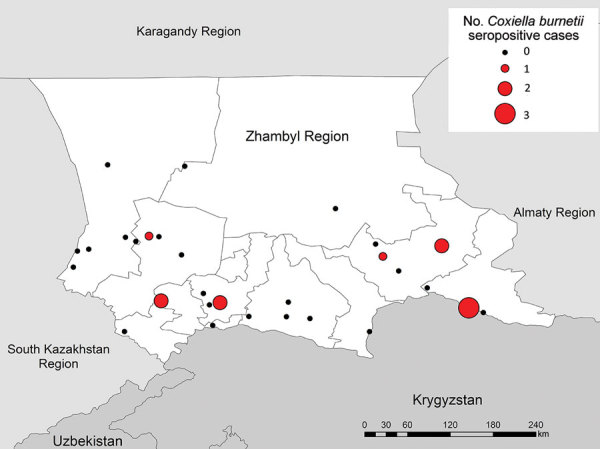

Of 910 samples tested for Q fever, 11 showed evidence of past exposure by C. burnetii IgG. Weighted seroprevalence was 1.3% (95% CI 0.3%–5.0%) with seropositivity in 5/30 (53.3%) villages (Figure 3). Occupations of the 11 seropositive participants were farmer or herder (n = 1), healthcare worker (n = 1), retired (n = 1), homemaker (n = 4), and inside or office worker (teacher, locksmith, or civil servant; n = 4;) (Table 6). Controlling for age and sex, history of herding (aOR 2.9, 95% CI 1.5–5.4) and slaughtering animals (aOR 2.7, 95% CI 1.5–4.8) had statistically significant associations with seropositivity. Villages at lower elevations were more likely to have >1 person seropositive for Q fever in logistic regression, but the association was not statistically significant (p = 0.49).

Figure 3.

Number of Coxiella burnetii–seropositive cases in villages included in serologic survey for tickborne diseases, Zhambyl region, Kazakhstan. Circle size denotes the number of IgG antibody–positive serology results indicating past exposure to C. burnetii.

Discussion

We conducted a serosurvey to update data on the prevalence of CCHF, Q fever, and Lyme disease in Kazakhstan. Because little is known about the seroprevalence of these diseases in central Asia, this study will increase regional awareness. Cases go undetected because of subclinical infections, nonspecific diagnostic methods, or poor surveillance. Our serosurvey identified persons exposed to these pathogens who might have been missed by existing surveillance platforms.

We found a weighted seroprevalence of 1.2% of CCHF in the study region, comparable to findings from studies in Turkey, Iran, and Bulgaria that reported seroprevalences of 2.3%–2.8% (20–22). We found a seroprevalence of 3.4% in villages classified as CCHF-endemic, similar to findings from studies in Bulgaria, China, Georgia, Kosovo, and Turkey that reported seroprevalences of 3%–4% (16,22–28). Most CCHFV serosurveys have been conducted in the Middle East, with a few in Asia, and prevalence estimates range widely, even in the same country.

The comparability of our results to other published surveys is limited because many studies sampled during an outbreak or only sampled high-risk populations. Another CCHFV serosurvey from Kazakhstan found a seroprevalence of 12.7% among patients hospitalized with a fever of unknown origin in the Almaty and Kyzylorda regions (29). Studies of persons exposed to livestock in Iran and Turkey reported CCHFV seroprevalences >12% (30,31). Serosurveys in abattoir workers reported seroprevalences ranging from 0.75% to 16.5% (32,33). Studies in hyperendemic territories reported seroprevalences >10% in the general population (34–41), and a study in Kosovo reported 24% seroprevalence (42).

We found moderate seroprevalence (2.4%) for B. burgdorferi compared with findings for other countries in the region. For instance, a serosurvey in Ukraine found seroprevalences of 25%–38% in a healthy population depending on the ecologic zone (43). However, seroprevalence could be caused by other Borrelia species in that region and might not be specific to the Lyme disease group of Borreliae. In addition, <3 of 35 persons tested in some villages were seropositive (43).

We also found a lower weighted seroprevalence for Q fever (1.3%) than most reports. Our findings more closely approximate the 3.1% seroprevalence reported in the United States (44). However, as with CCHFV, prevalence of past infection varies widely by location. For instance, reports from Turkey demonstrate ≈4% seroprevalence in urban areas but 19% in rural areas (45). As we saw with Lyme disease, some villages in our sample had <3 of 35 participants who tested seropositive. Previous studies identified higher seroprevalence for Q fever in butchers (46,47), and our study showed 30.6% of participants seropositive for Q fever had butchered animals or handled raw meat.

A limitation of our study is that the Lyme disease assay was designed for broader reactivity and was not analytically specific to a single agent. This assay likely also reacts with relapsing fever Borreliae, which has unknown distribution in Kazakhstan. Further, validation studies from Vanhomwegen et al. (17) reported an analytic sensitivity of 80% for CCHF IgG Vector-Best kits and 88% for the IgM kits, with a specificity of 100% for both, so the true seroprevalence could be underestimated. The same is true for Lyme disease; a study reported a sensitivity of only 68.8% for the Vector-Best Lyme IgG kit (18).

We were surprised by the few reports of tick bites, considering that ≈90% of respondents listed ticks as a major problem and about one third had found ticks on their livestock. A previous survey identified crushing ticks with bare hands as common and a risk factor for CCHF (16). However, most respondents in our study reported crushing ticks with an object, suggesting contact with livestock could be a more common route of exposure among participants. This possibility could be problematic because <20% of respondents identified infected animals as a potential source of transmission. In addition, nearly half did not wear PPE when slaughtering animals, an exceptionally high-risk activity. The low recognition of the role of livestock in CCHF transmission is seen in other regions (48,49), but targeted educational campaigns have improved knowledge of transmission routes (50).

Our results have been translated into direct public health action. For instance, the serosurvey revealed that CCHFV is circulating in areas previously unknown to have CCHF activity. Because such areas were not prioritized for educational activities, knowledge of CCHF and modes of transmission was low compared with areas of known transmission. In addition, whereas the KAP/risk factor survey revealed that most respondents understood the risks posed by ticks and many took precautions against tick bites, most did not understand the role animals play in these zoonoses, nor did they wear proper PPE when performing high-risk activities. We helped the health department clarify their pamphlets to state specific high-risk activities and describe which PPE should be worn during each activity. Formative research into the availability and affordability of PPE, as well as the cultural perceptions of PPE when performing activities that may have ritualistic significance, such as slaughtering, is warranted.

A One Health approach that recognizes the interconnectedness of animal, human, and environmental health is needed for effective zoonotic and vectorborne disease control. This study incorporated personnel from the Kazakhstan Ministry of Health, Zhambyl Oblast Public Health Protection Department, and the Ministry of Agriculture. Additional studies in the region will analyze blood and ticks collected from livestock for evidence of past zoonotic infection. Combining the results of the human serosurvey with results of the animal and tick surveys will permit more in-depth investigations into the role of environmental factors, such as climate and elevation, in the transmission of these pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Akimat of Zhambyl Oblast, the Health Protection Committee of the Ministry of Health and the Committee of Veterinary Control and Surveillance of the Ministry of Agriculture of Kazakhstan, Public Health Protection Department, Health Department, Sanitary Epidemiology Expertise Center, and the Veterinary Inspection unit of Zhambyl Oblast for their help in arranging and performing the investigation. We are grateful for Amber Dismer and Jodi Vanden Eng for technical assistance in the EpiSample application and to Mary Claire Worrell for her assistance generating maps for the application. We thank Ryan Wiegand for assistance in developing the sample selection protocol and Curtis Blanton for discussions regarding trimming of the sample weights.

Biography

Ms. Head is a doctoral student in epidemiology at the University of California, Berkeley, California, USA, and a previous Global Health Epidemiology Fellow at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia, USA. She has worked with CDC’s offices in Kazakhstan on surveillance platforms for influenza, encephalitis, and meningitis. Her research uses statistical and mathematical models to understand the transmission of environmentally mediated or zoonotic pathogens.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Head JR, Bumburidi Y, Mirzabekova G, Rakhimov K, Dzhumankulov M, Salyer SJ, et al. Risk factors for and seroprevalence of tickborne zoonotic diseases among livestock owners, Kazakhstan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Jan [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2601.190220

References

- 1.Taylor LH, Latham SM, Woolhouse ME. Risk factors for human disease emergence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:983–9. 10.1098/rstb.2001.0888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christou L. The global burden of bacterial and viral zoonotic infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:326–30. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03441.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paules CI, Marston HD, Bloom ME, Fauci AS. Tickborne diseases—confronting a growing threat. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:701–3. 10.1056/NEJMp1807870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kilpatrick AM, Randolph SE. Drivers, dynamics, and control of emerging vector-borne zoonotic diseases. Lancet. 2012;380:1946–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61151-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451:990–3. 10.1038/nature06536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitehouse CA. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Antiviral Res. 2004;64:145–60. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messina JP, Pigott DM, Golding N, Duda KA, Brownstein JS, Weiss DJ, et al. The global distribution of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109:503–13. 10.1093/trstmh/trv050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maurin M, Raoult D. Q fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:518–53. 10.1128/CMR.12.4.518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raoult D, Tissot-Dupont H, Foucault C, Gouvernet J, Fournier PE, Bernit E, et al. Q fever 1985-1998. Clinical and epidemiologic features of 1,383 infections. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79:109–23. 10.1097/00005792-200003000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray J, Kahl O, Lane R, Stanek G. Lyme borreliosis: biology, epidemiology, and control. 1st ed. Wallingford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: CABI; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone BL, Tourand Y, Brissette CA. Brave new worlds: the expanding universe of Lyme disease. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017;17:619–29. 10.1089/vbz.2017.2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nurmakhanov T, Sansyzbaev Y, Atshabar B, Deryabin P, Kazakov S, Zholshorinov A, et al. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus in Kazakhstan (1948-2013). Int J Infect Dis. 2015;38:19–23. 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoogstraal H. The epidemiology of tick-borne Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Asia, Europe, and Africa. J Med Entomol. 1979;15:307–417. 10.1093/jmedent/15.4.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsoi DC, Rapoport LP, Samartseva ET. Epidemiological studies of Q fever in the area of Dzhambul in the Kazakh SSR. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1980;24:206–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spengler JR, Bergeron É, Rollin PE. Seroepidemiological studies of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in domestic and wild animals. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004210. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greiner AL, Mamuchishvili N, Kakutia N, Stauffer K, Geleishvili M, Chitadze N, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever knowledge, attitudes, practices, risk factors, and seroprevalence in rural Georgian villages with known transmission in 2014. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158049. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanhomwegen J, Alves MJ, Zupanc TA, Bino S, Chinikar S, Karlberg H, et al. Diagnostic assays for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1958–65. 10.3201/eid1812.120710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manzeniuk IN, Vorob’eva MS, Nikitiuk NM, Arumova EA, Anan’eva LP, Baranova SG, et al. [Preparations for serodiagnosis of diseases due to causative agents of ixode tick-borne Borreliosis (Lyme disease). Communication 2. Comparative study of recombinant enzyme immunoassay test-systems (rELISA) for serological diagnosis of ixode tick-borne Borreliosis] [in Russian]. Antibiot Khimioter. 2004;49:25–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yagci-Caglayik D, Korukluoglu G, Uyar Y. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in selected seven provinces in Turkey. J Med Virol. 2014;86:306–14. 10.1002/jmv.23699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izadi S, Holakouie-Naieni K, Majdzadeh SR, Chinikar S, Nadim A, Rakhshani F, et al. Seroprevalence of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Sistan-va-Baluchestan province of Iran. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2006;59:326–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christova I, Gladnishka T, Taseva E, Kalvatchev N, Tsergouli K, Papa A. Seroprevalence of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, Bulgaria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:177–9. 10.3201/eid1901.120299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gergova I, Kamarinchev B. Seroprevalence of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in southeastern Bulgaria. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2014;67:397–8. 10.7883/yoken.67.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia H, Li P, Yang J, Pan L, Zhao J, Wang Z, et al. Epidemiological survey of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in Yunnan, China, 2008. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e459–63. 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sargianou M, Panos G, Tsatsaris A, Gogos C, Papa A. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: seroprevalence and risk factors among humans in Achaia, western Greece. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e1160–5. 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sidira P, Maltezou HC, Haidich AB, Papa A. Seroepidemiological study of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in Greece, 2009-2010. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:E16–9. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03718.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fajs L, Humolli I, Saksida A, Knap N, Jelovšek M, Korva M, et al. Prevalence of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in healthy population, livestock and ticks in Kosovo. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110982. 10.1371/journal.pone.0110982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gazi H, Özkütük N, Ecemis Ö, Atasoylu G, Köroglu G, Kurutepe S, et al. Seroprevalence of West Nile virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, Francisella tularensis and Borrelia burgdorferi in rural population of Manisa, western Turkey. J Vector Borne Dis. 2016;53:112–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdiyeva K, Turebekov N, Dmitrovsky A, Tukhanova N, Shin A, Yeraliyeva L, et al. Seroepidemiological and molecular investigations of infections with Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus in Kazakhstan. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;78:121–7. 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chinikar S, Ghiasi SM, Naddaf S, Piazak N, Moradi M, Razavi MR, et al. Serological evaluation of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in humans with high-risk professions living in enzootic regions of Isfahan province of Iran and genetic analysis of circulating strains. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:733–8. 10.1089/vbz.2011.0634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunes T, Engin A, Poyraz O, Elaldi N, Kaya S, Dokmetas I, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in high-risk population, Turkey. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:461–4. 10.3201/eid1503.080687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andriamandimby SF, Marianneau P, Rafisandratantsoa JT, Rollin PE, Heraud JM, Tordo N, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever serosurvey in at-risk professionals, Madagascar, 2008 and 2009. J Clin Virol. 2011;52:370–2. 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mostafavi E, Pourhossein B, Esmaeili S, Bagheri Amiri F, Khakifirouz S, Shah-Hosseini N, et al. Seroepidemiology and risk factors of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever among butchers and slaughterhouse workers in southeastern Iran. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;64:85–9. 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bayram Y, Parlak M, Özkaçmaz A, Çıkman A, Güdücüoǧlu H, Kılıç S, et al. Seroprevalence of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever in Turkey’s Van Province. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2017;70:65–8. 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2015.675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mustafa ML, Ayazi E, Mohareb E, Yingst S, Zayed A, Rossi CA, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Afghanistan, 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1940–1. 10.3201/eid1710.110061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bukbuk DN, Fukushi S, Tani H, Yoshikawa T, Taniguchi S, Iha K, et al. Development and validation of serological assays for viral hemorrhagic fevers and determination of the prevalence of Rift Valley fever in Borno State, Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108:768–73. 10.1093/trstmh/tru163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lwande OW, Irura Z, Tigoi C, Chepkorir E, Orindi B, Musila L, et al. Seroprevalence of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in Ijara District, Kenya. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:727–32. 10.1089/vbz.2011.0914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapman LE, Wilson ML, Hall DB, LeGuenno B, Dykstra EA, Ba K, et al. Risk factors for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in rural northern Senegal. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:686–92. 10.1093/infdis/164.4.686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bodur H, Akinci E, Ascioglu S, Öngürü P, Uyar Y. Subclinical infections with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, Turkey. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:640–2. 10.3201/eid1804.111374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koksal I, Yilmaz G, Aksoy F, Erensoy S, Aydin H. The seroprevalance of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in people living in the same environment with Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever patients in an endemic region in Turkey. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142:239–45. 10.1017/S0950268813001155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cikman A, Aydin M, Gulhan B, Karakecili F, Kesik OA, Ozcicek A, et al. Seroprevalence of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in Erzincan Province, Turkey, relationship with geographic features and risk factors. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016;16:199–204. 10.1089/vbz.2015.1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Humolli I, Dedushaj I, Zupanac TA, Muçaj S. Epidemiological, serological and herd immunity of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in Kosovo. Med Arh. 2010;64:91–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biletska H, Podavalenko L, Semenyshyn O, Lozynskyj I, Tarasyuk O. Study of Lyme borreliosis in Ukraine. Int J Med Microbiol. 2008;298:154–60. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2008.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson AD, Kruszon-Moran D, Loftis AD, McQuillan G, Nicholson WL, Priestley RA, et al. Seroprevalence of Q fever in the United States, 2003-2004. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:691–4. 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.09-0168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erturk R, Poyraz Ö, Güneş T. Serosurvey of Coxiella burnetii in high risk population in Turkey, endemic to Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus. J Vector Borne Dis. 2017;54:341–7. 10.4103/0972-9062.225839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gozalan A, Rolain JM, Ertek M, Angelakis E, Coplu N, Basbulut EA, et al. Seroprevalence of Q fever in a district located in the west Black Sea region of Turkey. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:465–9 . 10.1007/s10096-010-0885-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Esmaeili S, Pourhossein B, Gouya MM, Amiri FB, Mostafavi E. Seroepidemiological survey of Q fever and brucellosis in Kurdistan Province, western Iran. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:41–5. 10.1089/vbz.2013.1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yilmaz R, Ozcetin M, Erkorkmaz U, Ozer S, Ekici F. Public knowledge and attitude toward Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever in Tokat Turkey. Iran J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2009;3:12–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gungormus Z, Kiyak E. Evaluation of knowledge about protection against Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2011;42:737–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koculu S, Oncul A, Onal O, Yesilbag Z, Uzun N. Evaluation of knowledge of the healthcare personnel working in Giresun province regarding Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever before and after educational training. J Vector Borne Dis. 2015;52:166–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]