Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Purpose

To investigate the effectiveness of using national, longitudinal milestones data to provide formative assessments to identify residents at risk of not achieving recommended competency milestone goals by residency completion. The investigators hypothesized that specific, lower milestone ratings at earlier time points in residency would be predictive of not achieving recommended Level (L) 4 milestones by graduation.

Method

In 2018, the investigators conducted a longitudinal cohort study of emergency medicine (EM), family medicine (FM), and internal medicine (IM) residents who completed their residency programs from 2015 to 2018. They calculated predictive values and odds ratios, adjusting for nesting within programs, for specific milestone rating thresholds at 6-month intervals for all subcompetencies within each specialty. They used final milestones ratings (May–June 2018) as the outcome variables, setting L4 as the ideal educational outcome.

Results

The investigators included 1,386 (98.9%) EM residents, 3,276 (98.0%) FM residents, and 7,399 (98.0%) IM residents in their analysis. The percentage of residents not reaching L4 by graduation ranged from 11% to 31% in EM, 16% to 53% in FM, and 5% to 15% in IM. Using a milestone rating of L2.5 or lower at the end of post-graduate year 2, the predictive probability of not attaining the L4 milestone graduation goal ranged from 32% to 56% in EM, 32% to 67% in FM, and 15% to 36% in IM.

Conclusions

Longitudinal milestones ratings may provide educationally useful, predictive information to help individual residents address potential competency gaps, but the predictive power of the milestones ratings varies by specialty and subcompetency within these 3 adult care specialties.

In 2001, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), along with the American Board of Medical Specialties, launched 6 general competencies as part of the Outcomes Project.1,2 One of the primary goals of this joint initiative was to facilitate the transition to outcomes-based education in residency and fellowship programs. The 6 general competencies—patient care and procedural skills, medical knowledge, professionalism, interpersonal skills and communication, system-based practice, and practice-based learning and improvement—were designed to help graduate medical education (GME) programs transform curricula and assessment to address the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors needed for modern clinical practice and to provide a framework for lifelong learning.1

Background

Brief history of competencies and milestones

Implementation of the 6 general competencies proved difficult. For example, some of the competencies, such as practice-based learning and improvement and systems-based practice, were new to educators. Another major challenge in using this competency framework to move to an outcomes-based approach has been designing curricula and assessments that are more deliberately and explicitly developmental.3 Milestones were first explored in 2007 as a potential approach to help guide longitudinal, developmental assessment of the general competencies and to create educational outcome measures for individual learners and GME programs.4 Milestones are narrative, specialty-specific descriptions of abilities at various stages of professional development that are based on the Dreyfus model.1,4,5 Milestones for the 6 general competencies are further subdivided into a set of subcompetencies that vary in number and content by specialty.6 Based on encouraging pilot studies,4,5 the ACGME decided to include milestones as a new component of the Next Accreditation System.6

Purpose and goal of milestones

Milestones are designed as a formative (or improvement focused, not summative) assessment framework to help facilitate and support the ongoing development of individual learners and the continual quality improvement of training programs. The only milestones-related accreditation requirement for GME programs is to report data on their learners twice a year, namely after their clinical competency committees (CCCs) have met to discuss each learner. Program directors and CCCs use the milestones framework to make educational judgments about learner progress, and they should use those judgments, along with supporting assessments, to provide meaningful feedback to learners.

The milestones initiative was officially launched in July 2013 with 7 specialties.7 The majority of remaining specialties started reporting in 2014. Cross-sectional, point-in-time studies examining milestones data across several specialties have provided some early validity evidence, and they have highlighted key features of milestones that are useful and helpful to residents.8–11 Recently, Weinstein12 commented on a report of a workshop at the National Academy of Medicine (NAM)13; both Weinstein and NAM noted that the assessment of GME effectiveness must increasingly be based on clinical practice outcomes post graduation and move beyond single proxy measures such as performance on a specialty certification exam.12,13 Notably, however, to make meaningful connections to future clinical performance outcomes, specialties need some level of a shared understanding of core educational outcomes for their specialty. The milestones as educational outcomes represent a step in this journey of linking performance in residency and fellowship to future practice. The prediction of clinical outcomes must be based not only on actual postgraduation clinical practice outcomes of previous cohorts but also on intermediate educational outcomes that are shown to be predictive of salutary clinical outcomes after graduation.

Milestones and learning analytics

We believe that longitudinal milestones data could enable the examination of learners’ developmental trajectories across the subcompetencies within each specialty. Learning analytics provides an approach and philosophy to help programs not only better identify specific opportunities for the growth and development of all learners but also identify learners at greater risk for not achieving recommended graduation targets.14 As defined by Johnson and colleagues, “learning analytics refers to the interpretation of a wide range of data produced by and gathered on behalf of students to assess academic progress, predict future performance, and spot potential issues.”15 Johnson et al and the United States Department of Education also note that learning analytics can help programs and institutions assess curricula and refine existing assessment approaches.15,16

Milestones data represent an amalgam and synthesis of multiple assessments into a set of developmental judgments about each resident. Milestones judgments should incorporate both quantitative and qualitative assessment information.17,18 Chan and colleagues note that milestones data can be used both for assessing the individual progression of a learner and by programs in a post hoc approach to improve programmatic assessment.14 Using longitudinal milestones data, we examined whether certain developmental patterns are predictive of an inability to attain the recommended fourth level of competency (of 5, see below) for each subcompetency by residency completion in 3 adult medicine specialties that entail 3-year residency programs: emergency medicine (EM), family medicine (FM), and internal medicine (IM). We hypothesized that specific, lower milestone ratings at earlier time points in residency would be predictive of not achieving the recommended Level 4 milestone by graduation.

Method

Study design

In 2018, we conducted a predictive modeling study using longitudinal milestones data from a cohort of residents in 3 specialties in the United States—EM, FM, and IM—who completed their training between July 2015 and June 2018. We conceptualized our analysis in this study as an assessment of how effectively midresidency milestones ratings (akin to a formative test such as a residency in-training examination of medical knowledge) performed as a feedback tool and/or as an early-warning signal of later suboptimal performance within the specific subcompetency.

Cohort population

Our study population comprised all residents who entered a 3-year EM, FM, or IM program in the United States in 2015 and completed their residency within the same program in 2018. Residents were excluded from analysis if:

their milestones ratings as a third-year resident were not reported when they graduated,

their milestones ratings as a first-year resident were not reported in December 2015, or

the resident missed at least 1 milestones assessment.

We selected EM, FM, and IM because each has now graduated at least 2 cohorts of residents who completed their training programs using milestones for the entirety of their residency and because all 3 specialties use Level 4 as the recommended (not required) target for residents to achieve for each subcompetency milestone upon graduation. For all 3 specialties, Level 4 roughly equates to proficiency in the Dreyfus model and signals readiness for clinical practice.1 We excluded 4-year EM programs to enable trajectory comparisons among 3-year specialties.

Milestones comparisons and choice of ratings for analysis

In each of the 3 selected specialties, programs judge residents on the milestones twice a year, meaning each resident receives 5 total reviews before the sixth and final review at graduation. While milestone Level 4 is the recommended graduation target, each specialty has constructed its subcompetency milestones narratives somewhat differently. Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 (available at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A716) provides an example of comparable patient care milestones from each of the 3 specialties.

EM and FM both labeled the 5 levels of milestones as simply “Level 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5,” and both provided an optional column labeled “Has not yet achieved Level 1.” IM, however, labeled Level 1 “Critical deficiency”; Level 4, “Ready for unsupervised practice”; and Level 5, “Aspirational.” Levels 2 and 3 do not include descriptors. The majority of residents in all 3 specialties would, ideally, demonstrate a Level 3 performance for most subcompetencies (“competence” in the Dreyfus model) at the point in training when they are entrusted to care for patients under mostly indirect or reactive supervision.19 A rating at Level 2 or 2.5 (i.e., still in transition to Level 3) for a resident who has only 12 to 18 months of the residency remaining but who has been afforded substantial clinical responsibilities under indirect or reactive supervision would hopefully trigger a careful review of the learner’s remaining clinical experiences plus additional assessments and/or an individualized learning plan (ILP).

Time points and predictive indices

We therefore used the milestones ratings from December 2016 and January 2017 (third milestones review occasion) and from May and June 2017 (fourth milestones review occasion) as the predictor variables. We selected a rating of Level 2.5 or lower in the middle of postgraduate year (PGY)-2, approximately 18 months into training, and a rating of Level 2.5 or lower at the end of PGY-2, approximately 24 months into training, as predictors of residents at risk of not achieving recommended competency milestones by the time they complete their residency program. We chose these 2 time points for 2 primary reasons. First, these ratings occur when the programs have assessed the individual resident’s progress a total of, respectively, 3 and 4 times, providing the program with a longitudinal pattern of performance. Second, by examining performance in PGY-2, the program still has sufficient time to institute targeted ILPs or, if needed, more formal and structured remediation.

Attainment of the recommended graduation target (i.e., Level 4) in each subcompetency at the time of graduation was the ideal educational outcome measure we used for this study. We used the Level 2.5 threshold at 2 time points and the final milestone rating (sixth milestones review occasion) for each of the 22 subcompetencies in IM and FM and the 23 subcompetencies in EM as the predictor variables. For each milestones review occasion, the specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and odds ratios (ORs) were calculated (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A716).

Statistical analysis

We obtained sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and OR data for each of the subcompetencies by milestones review occasions by using a generalized estimating equations model to account for potential correlations of milestones ratings among residents within each program (i.e., residents were nested within programs). For this purpose, we used an exchangeable working correlation matrix, based on the assumption that any 2 observations within a program have the same correlation. Once we estimated PPV and NPV, we regressed the status of not reaching Level 4 at the time of graduation (coded as 1 = has not achieved Level 4, 0 = has achieved or exceeded Level 4) on the Level 2.5 threshold (coded as 1 = has achieved a rating at or below Level 2.5, 0 = has achieved a rating greater than Level 2.5). Once we calculated sensitivity and specificity, we regressed the Level 2.5 threshold on the status of not reaching Level 4 at graduation. We used Bonferroni corrections to adjust for multiple comparisons in each specialty. We also calculated the number of programs that did not report any resident as receiving a rating lower than Level 4 at graduation for all subcompetencies; for these programs, milestones learning analytics would likely be less useful. Finally, using the same regression procedure outlined above, we calculated PPV estimates for each milestone rating threshold from Level 0 to Level 5 for each subcompetency and milestones review occasion, resulting in a comprehensive PPV matrix for each specialty. For the IM subcompetencies, critical deficiency was coded as Level 1 to be consistent with Level 1 in EM and FM subcompetencies. We used SAS Enterprise Guide (version 7.15, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) for all analyses.

Ethical considerations

The American Institutes for Research reviewed and approved this study. We conducted all analyses using deidentified datasets, procured from the ACGME.

Results

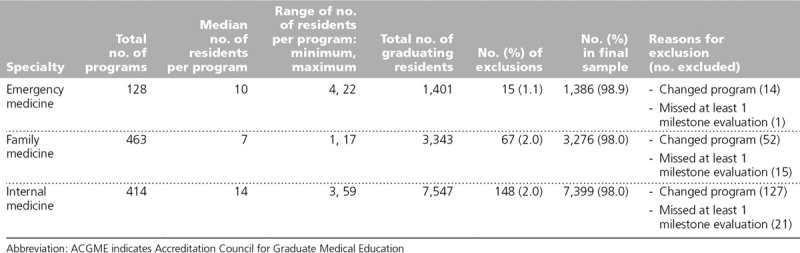

Through this study, we investigated the effectiveness of using national, longitudinal milestones data to provide formative assessments to identify residents at risk of not achieving recommended competency milestones levels by the time they complete their residency. We included a total of 1,386 EM residents (98.9% of residents from 128 programs), 3,276 FM residents (98.0% of residents from 463 programs), and 7,399 IM residents (98.0% of residents from 414 programs) in our analyses. See Table 1 for the demographic details of our study population. Table 2 provides the range of PPVs, NPVs, and ORs for each specialty, broken down by the 6 general competencies, for both the third and fourth milestones review occasions. We have provided the full results (number of residents not achieving Level 4, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and OR) for each subcompetency by specialty in the Supplemental Digital Appendix 3 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A716. The percentage of residents not reaching Level 4 ranged from 11% to 31% in EM (23 subcompetencies), 16% to 53% in FM (22 subcompetencies), and 5% to 15% in IM (22 subcompetencies). In IM, 90 programs (22%) did not report any graduating residents receiving a rating lower than a milestone Level 4 at graduation in any subcompetency; however, the proportion of programs without any residents achieving less than Level 4 in any subcompetency at graduation was much lower in FM (21 programs, 5%) and EM (9 programs, 7%).

Table 1.

Resident Sample and Exclusions by Specialty for a 2018 Study of ACGME Milestones Achievement

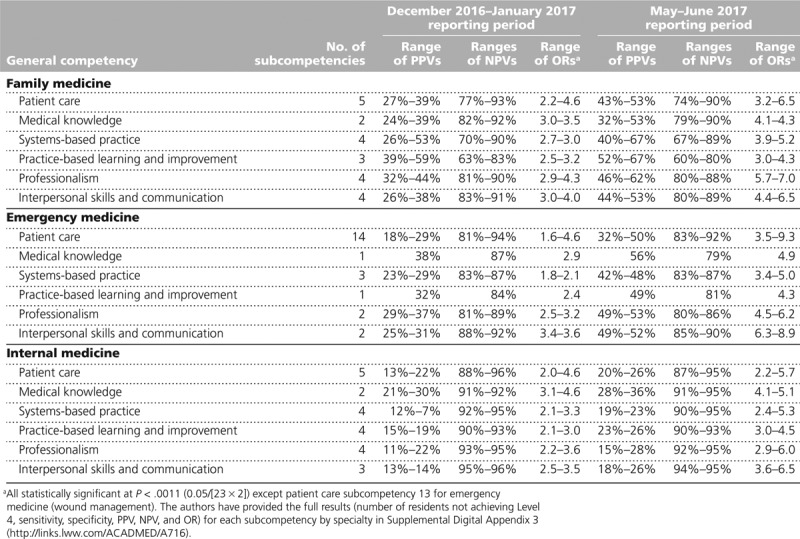

Table 2.

Milestones Ratings and Range of Positive Predictive Values (PPVs,) Negative Predictive Values (NPVs,) and Odds Ratios (ORs) for 6 General Competencies by Specialty by Reporting Period

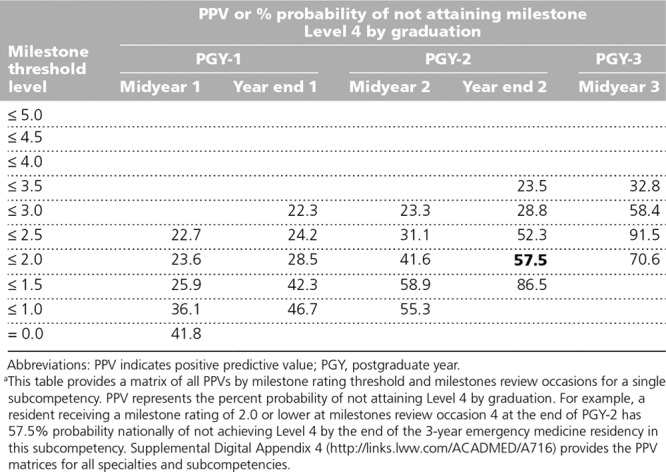

In Supplemental Digital Appendix 3 (http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A716), the PPV columns provide the percent probability, and the OR columns provide the odds, that a resident at or below the Level 2.5 threshold at milestones review occasion 3 (December 2016–January 2017) and milestones review occasion 4 (May–June 2017) would not achieve the recommended Level 4 by graduation. ORs were significantly elevated for all but one of the subcompetencies across all 3 specialties at both time points (only the EM patient care subcompetency of wound management at the December 2016–January 2017 milestones review occasion did not reach statistical significance). The PPVs in EM and FM were higher than those in IM. For example, residents in FM judged to be at or below Level 2.5 with 12 months remaining in their program had a 32% to 67% range of not reaching Level 4 across the 22 subcompetencies, with over half of PPVs 50% or higher. For IM, the PPVs were mostly in the 20% to 30% range. Finally, Table 3 provides an example of a PPV matrix for 1 EM subcompetency. Most of the PPVs rise with lower milestones ratings, especially later into residency. The PPV matrix for all subcompetencies is provided in Supplemental Digital Appendix 4 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A716.

Table 3.

PPV Matrix for the Team Management Subcompetency in Emergency Medicine: Leads Patient-Centered Care Teams, Ensuring Effective Communication and Mutual Respect Among Members of the Teama

Discussion

Summary of findings

The milestones are designed to help facilitate the professional development of residents longitudinally through formative assessment and feedback. For EM, FM, and IM, the recommended goal for graduation is to achieve performance at Level 4 (or higher) on the milestones. This study demonstrates that milestones ratings made at specific points during residency may provide educationally useful, predictive information or feedback about individual residents’ trajectories across the subcompetencies within all 3 disciplines. Using these predictive data as part of a learning analytics strategy may help program directors and CCCs identify which residents they need to consider more carefully and discuss further to explore why these learners may not be progressing as expected within a subcompetency. These data cannot, especially in isolation, provide an explanation for the ratings, but by looking at milestones data trajectories longitudinally, a program director or CCC may be able to better identify residents in need of guidance and help those residents refocus their learning. The data may help residents and clinical faculty develop ILPs for residents needing more formal remediation or intervention. The use of ILPs should be a core component of the milestones process and is consistent with best feedback practice.20–23

These data may also provide useful feedback for training programs and for each specialty as a whole.14–16 For example, in FM, 53% of residents did not attain Level 4 in the practice-based learning and improvement subcompetency of “improves systems in which the physician provides care.” This finding is likely more indicative of either challenges in designing curriculum or the availability of effective assessment tools than of resident achievement. Milestones were not designed to be used for high-stakes summative purposes but rather to continually facilitate improvement in curriculum and assessment; thus, in some of the subcompetencies, especially for FM and EM, the data may be more useful as a tool for the overall program and national specialty goals than for guiding individual residents.

Use of the predictive indices for individual and program improvement

The ultimate goal of the milestones framework is to provide specialty-specific formative assessment and feedback to assist each resident in achieving proficiency by graduation. This formative, or improvement, role of the milestones cannot be overstated. These data provide an early signal of the potential to use national milestones data to help guide programs and individual residents. If milestones were to be used as a summative tool, educators would likely not observe the current patterns in the results since the consequences of an assessment affect how the assessment is performed by the user.24,25 That is, the higher the stakes, the more likely problems such as halo and leniency error are to occur.25

Programs will need to guard both against labeling residents “problematic” if they are identified as being at risk for not achieving Level 4 and against creating a feed-forward bias. This precaution is particularly important because the outcome measure is the program’s final milestones rating, not an external gold standard like those typically used in PPV and NPV diagnostic-type tests. On the other hand, the lack of forward feeding of essential concerns and assessment information would place the resident—and, by extension, patients—at greater risk for not acquiring needed competencies before entry into unsupervised practice.26 The ultimate goal, and part of the professionalism of medical educators, is to appropriately identify residents at risk and intervene. This goal concerns as much, if not more, a cultural issue within medical education versus a technical analytic problem, but evidence-based data can help effect cultural transformation.27

To use these predictive indices most effectively, programs must understand their own CCC milestones rating culture, the local assessments that inform the milestones ratings, and their overall rating patterns.21 For example, a program that is consistently lenient on milestones ratings will likely have more false negatives (i.e., miss struggling residents). On the other hand, the PPV in a lenient program that does provide low milestones ratings within a subcompetency will likely be higher and therefore more meaningful in identifying a resident needing further review and discussion. Programs can get a sense of their milestones rating tendencies by examining their program-level data against the national distributions provided in annual milestones data reports.28 The opposite patterns may exist for programs that tend to be more stringent and may result in more false positives (i.e., identify residents who are actually progressing on pace); however, false positives become a serious issue only if milestones data are used for summative purposes. If the goal is to apply the milestones data to inform residents and CCCs of each learner’s probability of achieving Level 4, the risk of untoward bias against the resident should be lower. The bottom line is that each program needs to have sufficient insight into its own milestones rating patterns and behaviors to maximize the value of using these predictive analytic indices from a national sample.

Using predictive indices: Milestones 2.0

This analysis may also be helpful in the Milestones 2.0 revision process. While the ORs were elevated for IM, the PPVs in this specialty had less predictive power compared with those in EM and FM. There may be several reasons for this. First, ORs are insensitive to the denominator and, at best, may trigger a second look, but unlike PPVs, ORs cannot speak to the absolute magnitude of the risk. Second, the IM milestones are on a more compressed scale with the critical deficiency level used instead of a Level 1 approach. Third, labeling Level 4 as “Ready for unsupervised practice,” combined with the effects of individual milestones data being shared with the American Board of Internal Medicine, may contribute to possible leniency or halo effects.8 Fourth, the proportion of IM residents not achieving Level 4 is lower than that in EM and FM. In fact, over 20% of programs did not rate one of their IM residents lower than Level 4 in any of the 22 subcompetencies, a proportion substantially higher than that in either EM or FM.

Limitations

We acknowledge some limitations. First, we cannot fully speak to the accuracy of the milestones ratings, how each program approaches making milestone ratings in their CCCs, and what assessment information was used to make such ratings. Second, we do not have information on how the various programs handle struggling residents and what remediation processes they use. Remediation is the focus of another study currently underway at the ACGME. Third, these data can provide a signal around risk but cannot speak to the reasons behind lower ratings; explanations depend on thoughtful review and deliberation by CCCs and programs. Milestones ratings clearly depend on the quality of assessments and CCC processes.29–31 Several national qualitative studies are currently underway to better understand how CCCs make longitudinal decisions in EM, FM, and IM, and the results of these studies will inform Milestones 2.0 development.

Fourth, milestones can be subject to the same rater errors that occur in other assessment tools.25,32 Determining how much halo effect and leniency error, or severity error, might be present in the current milestones ratings is difficult; thus, programs should carefully consider these issues when using these data.25,32 We have certainly observed some potential evidence for halo and leniency in some of the programs in this study. Programs can use the 2018 national milestones report to compare their pattern of milestone ratings against a national sample to get a sense of leniency versus stringency.28 Programs may also want to review some of the milestones validity studies, including those examining the 3 specialties involved in this analysis.9–11 Fifth, the outcome variable for the PPV, NPV, and OR determinations was the final milestones rating and not an external standard; thus, the milestones ratings are intended solely for the purpose of an educational diagnostic outcome prediction. As the milestones system matures, future predictive analytic work should explore external measures as outcomes. To that end, a recent study in an EM program showed that using in-program assessments as outcomes provided useful predictive diagnostic input for identifying residents at risk.33

Next steps

As programs start to use these types of data, the desired outcome would be to reduce the number of residents not achieving Level 4 through the use of ILPs, coaching, curricular adjustments, and, when necessary, more formal remediation.21,34 Several early studies provided some preliminary evidence that milestones have helped to identify not only struggling residents needing formal remediation but also curricular gaps.21,31,34 If those programs that still provide more lenient ratings realize the potential value of this type of predictive analysis, they may become more comfortable providing lower milestone ratings when appropriate.

As milestones experience grows, predictive analyses will need to be conducted on a yearly basis. The primary goal of this research is to provide programs with data that will (1) help them guide residents’ professional development and (2) allow them to examine their own rating patterns as part of ongoing quality improvement activities in assessment. A second goal is to establish the validity and reliability of using national milestones data for formative purposes to enhance the effectiveness of GME—both through national efforts and through individual programs’ continuous quality improvement processes.

Future work will include following graduates into practice to see if longitudinal milestones ratings and developmental trajectories in residency correlate with various aspects of practice, such as quality and safety measures, scope of practice, and costs of care.12 Linking these educational outcomes data to future clinical and systems outcomes data will further enable important feedback loops for individual learners and programs alike. These analyses will also help to extend the early validity work with the milestones in these 3 and other specialties.9–11,31 Finally, as milestones and other assessment data continue to accrue and as programs continue to evolve their assessment programs, there will be an opportunity to explore the use of machine learning algorithms that may provide better precision and more timely feedback to programs both locally and nationally.34

Conclusions

In conclusion, the availability of longitudinal milestones data has enabled the creation of predictive indices that provide programs and specialty disciplines formative data in key competencies beyond medical knowledge to guide continuous quality improvement of residency training. These predictive indices can help identify residents who may be struggling and guide their improvement and their professional growth. These predictive indices may be a useful adjunct to CCC conversations about resident progress and needs for ILPs or more formal remediation programs. The ultimate goal is to ensure that all graduates of residency programs are truly ready to enter clinical practice with high levels of ability across all essential competencies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A716.

Funding/Support: The authors acknowledge the support of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Other disclosures: The authors are employees of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Dr. Holmboe receives royalties from Elsevier for a textbook on assessment.

Ethical approval: The American Institutes for Research reviewed the research protocol reported herein and deemed it exempt.

Previous presentations: Portions of this research were presented at the Association of Medical Education in Europe (AMEE), August 2018, Basel, Switzerland, and at the International Conference on Residency Education (ICRE), October 2018, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Data: No external data outside of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education were used for this study.

References

- 1.Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: Retrospective and prospective. Med Teach. 2007;29:648–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmboe ES, Batalden P. Achieving the desired transformation: Thoughts on next steps for outcomes-based medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90:1215–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green ML, Aagaard EM, Caverzagie KJ, et al. Charting the road to competence: Developmental milestones for internal medicine residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1:5–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aagaard E, Kane GC, Conforti L, et al. Early feedback on the use of the internal medicine reporting milestones in assessment of resident performance. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:433–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system—Rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1051–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swing SR, Beeson MS, Carraccio C, et al. Educational milestone development in the first 7 specialties to enter the next accreditation system. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hauer KE, Clauser J, Lipner RS, et al. The internal medicine reporting milestones: Cross-sectional description of initial implementation in U.S. residency programs. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauer KE, Vandergrift J, Hess B, et al. Correlations between ratings on the resident annual evaluation summary and the internal medicine milestones and association with ABIM certification examination scores among US internal medicine residents, 2013–2014. JAMA. 2016;316:2253–2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beeson MS, Holmboe ES, Korte RC, et al. Initial validity analysis of the emergency medicine milestones. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:838–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mainous AG, 3rd, Fang B, Peterson LE. Competency assessment in family medicine residency: Observations, knowledge-based examinations, and advancement. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:730–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinstein DF. Optimizing GME by measuring its outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2007–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services. Graduate Medical Education Outcomes and Metrics: Proceedings of a Workshop. 2018. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25003/graduate-medical-education-outcomes-and-metrics-proceedings-of-a-workshop. Accessed July 1, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan T, Sebok-Syer S, Thoma B, Wise A, Sherbino J, Pusic M. Learning analytics in medical education assessment: The past, the present, and the future. AEM Educ Train. 2018;2:178–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson L, Smith R, Willis H, Levine A, Haywood K. The 2011 Horizon Report. 2011. Austin, TX: The New Media Consortium; https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED515956.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Technology. Enhancing Teaching and Learning Through Educational Data Mining and Learning Analytics: An Issue Brief. 2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education; https://tech.ed.gov/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/edm-la-brief.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schumacher DJ, Michelson C, Poynter S, et al. ; APPD LEARN CCC Study Group. Thresholds and interpretations: How clinical competency committees identify pediatric residents with performance concerns. Med Teach. 2018;40:70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson RS, Borgert AJ, O’Heron CT, et al. A multicenter prospective comparison of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestones: Clinical competency committee vs. resident self-assessment. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:e8–e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ten Cate O, Chen HC, Hoff RG, Peters H, Bok H, van der Schaaf M. Curriculum development for the workplace using entrustable professional activities (EPAs): AMEE guide no. 99. Med Teach. 2015;37:983–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sargeant J, Lockyer J, Mann K, et al. Facilitated reflective performance feedback: Developing an evidence- and theory-based model that builds relationship, explores reactions and content, and coaches for performance change (R2C2). Acad Med. 2015;90:1698–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmboe ES, Edgar L, Hamstra S. The Milestones Guidebook, Version 2016. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/MilestonesGuidebook.pdf?ver=2016-05-31-113245-103. Accessed July 1, 2019.

- 22.Lefroy J, Watling C, Teunissen PW, Brand P. Guidelines: The do’s, don’ts and don’t knows of feedback for clinical education. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4:284–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messick S. Linn RL. Validity. In: Educational Measurement. 1989:3rd ed New York, NY: American Council on Education/Macmillan Publishing Company; 13–104. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downing SM. Validity: On meaningful interpretation of assessment data. Med Educ. 2003;37:830–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pangaro LN, Durning SJ, Holmboe ES. Holmboe ES, Durning SJ, Hawkins RE. Evaluation frameworks, forms, and global rating scales. In: Practical Guide to the Evaluation of Clinical Competence. 2018:2nd ed Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleary L. “Forward feeding” about students’ progress: The case for longitudinal, progressive, and shared assessment of medical students. Acad Med. 2008;83:800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pangaro L. “Forward feeding” about students’ progress: More information will enable better policy. Acad Med. 2008;83:802–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamstra SJ, Yamazaki K, Edgar L, Sangha S, Holmboe ES. Milestones National Report 2018. 2018. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/2018_Milestones_National_Report_2018-09-18_final.pdf?ver=2018-09-19-142602-030. Accessed July 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hauer KE, Chesluk B, Iobst W, et al. Reviewing residents’ competence: A qualitative study of the role of clinical competency committees in performance assessment. Acad Med. 2015;90:1084–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hauer KE, Cate OT, Boscardin CK, et al. Ensuring resident competence: A narrative review of the literature on group decision making to inform the work of clinical competency committees. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8:156–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conforti LN, Yaghmour NA, Hamstra SJ, et al. The effect and use of milestones in the assessment of neurological surgery residents and residency programs. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray JD. Global rating scales in residency education. Acad Med. 1996;71(1 suppl):S55–S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ariaeinejad A, Samavi R, Chan TM, Doyle TE. A performance predictive model for emergency medicine residents. November 2017In: Proceedings of 27th Annual Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering, Markham, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmboe ES, Call S, Ficalora RD. Milestones and competency-based medical education in internal medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1601–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]