Short abstract

http://aasldpubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/hub/journal/10.1002/(ISSN)2046-2484/video/14-5-reading-patel a video presentation of this article

http://aasldpubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/hub/journal/10.1002/(ISSN)2046-2484/video/14-5-interview-patel the interview with the author

Abbreviations

- ADPLD

autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease

- AS

aspiration sclerotherapy

- ESRD

end‐stage renal disease

- LT

liver transplantation

- MELD

Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease

- PLD

polycystic liver disease

- TLV

total liver volume

Establish the Diagnosis

Polycystic liver disease (PLD) is characterized by more than 20 fluid‐filled biliary epithelial‐lined cysts in the liver.1 The majority of PLD cases occur as an extrarenal manifestation of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) caused by mutations in PKD1 and PKD2.2 A separate condition, autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease (ADPLD), is caused by mutations in SEC63 and PRKCHS genes, among others, and manifests with cysts typically restricted to the liver.2, 3 Distinguishing ADPKD from ADPLD is crucial because the former can progress to end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) and has extrarenal manifestations, which require extra vigilance and sometimes preemptive screening (e.g., intracranial aneurysms) (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Location | Extrarenal Manifestations (Frequency) | Additional Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | Liver cysts (94% over the age of 35 years) | |

| Diverticular disease (50%‐83% in patients with ESRD) | Diverticular disease and abdominal hernias are not routinely screened for in patients with ADPKD; however, studies have shown an increased occurrence in patients with ESRD related to ADPKD | |

| Hernias (45%) | ||

| Pancreatic cysts (9%‐36%) | Pancreatic cysts can clinically present as chronic pancreatitis because of compression of the pancreatic duct | |

| Common bile duct dilation (40%) | ||

| Choledochal cysts (rare) | ||

| Splenic cysts (2.7%) | ||

| Nongastrointestinal | Cardiac valve abnormalities (mitral valve prolapse: 25%) | Screening with echocardiography is not recommended unless a murmur is detected or cardiovascular symptoms arise3 |

| Pericardial effusion (35%) | ||

| Arachnoid cysts (8%‐12%) | Patients with focal neurological deficits and headaches should be evaluated for arachnoid membrane cysts, but they are usually asymptomatic | |

| Cerebral aneurysms (9%‐12%) | Patients with a family history of intracranial arterial aneurysms or hemorrhagic strokes, or who present with sudden severe headache should be screened and evaluated through magnetic resonance angiography. Asymptomatic patients without a family history who are older than 30 years should be counseled on the risks and benefits of screening prior to proceeding.5 No screening is recommended for extracranial aneurysms located in the aorta, coronary, or splenic arteries3 | |

| Spinal meningeal cysts (1.7%) | Spinal cysts can rarely present with orthostatic headache, diplopia, hearing loss, and ataxia | |

| Seminal vesicle cysts (40%) | ||

| Bronchiectasis (37%) | ||

| Thyroid cysts (not clearly defined) |

In all cases of PLD, acquisition of an accurate family history and a radiographic evaluation for the presence of renal cysts should be performed. Ultrasound is often used; however, computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are more sensitive for detecting kidney or liver cysts.3

The diagnosis of ADPKD in the setting of liver cysts is based on a family history of polycystic kidneys with a requisite number of renal cysts for a given age (Table 2). Importantly, up to one‐third of ADPLD patients have small numbers of renal cysts, but typically without renal expansion, increased total kidney volume, or kidney dysfunction.4 Notably, liver cysts in ADPLD are often greater in quantity and size than those of ADPKD.

Table 2.

| Family History | ADPLD | ADPKD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Age < 40 years | At least one hepatic cyst | Age 15‐39 years | At least three unilateral or bilateral renal cysts |

| Age > 40 years | At least four hepatic cysts | Age 40‐59 years | At least two unilateral renal cysts | |

| Age ≥ 60+ years | At least four cysts in each kidney | |||

| Negative | >20 liver cysts with no renal cysts; a small number of renal cysts may be present in 28%‐35% of patients, but renal dysfunction is absent | Age < 30 years | Five bilateral renal cysts | |

| Age 30‐60 years | Five bilateral renal cysts | |||

| Age > 60 years | Eight bilateral renal cysts | |||

Rarely, after radiographic evaluation a causative diagnosis may be uncertain and genetic testing should be considered and may be required for access to certain therapies (e.g., tolvaptan for preventing the progression of renal dysfunction). Genetic testing can also be useful for prognostication. PKD1 mutations are found in 85% to 90% of patients with ADPKD; the remaining 10% to 15% have PKD2 mutations, which are often associated with a milder phenotype and later progression to ESRD.5, 6 SEC63 and PRKCSH mutations, which result in abnormal trafficking of the PKD1 and PKD2 proteins, cause more severe ADPLD. However, 70% of patients do not have identifiable mutations.

Characterize the Symptoms

One of five patients with PLD experience symptoms (from direct compression of nearby structures), with the most common being abdominal pain or distention, nausea, emesis, esophageal reflux, early satiety, shortness of breath, and lower back pain.5 These symptoms should be monitored at routine office visits. Importantly, women are typically more severely affected with Polycystic Liver Disease Questionnaire than men. Two validated, disease‐specific questionnaires, the PLD‐Q and the Polycystic Liver Disease Complaint Specific Assessment can be used to systematically assess symptom burden and evaluate treatment efficacy.1

Patients can experience acute liver cyst complications as well. These include infection, rupture, torsion, and hemorrhage, which often manifest as acute, severe right upper quadrant abdominal pain and/or fevers. Furthermore, rarely, cyst compression of the biliary tree or hepatic vasculature can produce obstructive jaundice or portal vein thrombosis or complications from portal hypertension, respectively.1 Importantly, despite massive liver cystic involvement, parenchymal function is preserved in PLD; thus, if reduced serum albumin levels are observed, it is typically secondary to malnutrition. Thus, with massive hepatomegaly, biannual assessment of functional status, muscle mass, and prealbumin and albumin should be considered.

Characterize the Cyst Burden

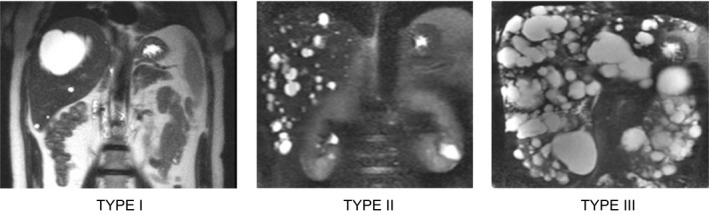

The emergence of symptoms should prompt cross‐sectional imaging to characterize liver cyst burden and determine appropriate treatment; there is no role for routine surveillance of cysts with imaging. Several classification systems have been proposed, including the widely cited Gigot classification (Fig. 1) and the Schnelldorfer classification system, which has been incorporated into the exception points criteria for liver transplantation (LT) (Table 3).

Figure 1.

The Gigot classification for PLD. Type I is characterized by a liver that has <10 large (>10 cm) cysts. Type II is characterized by diffuse parenchymal involvement by multiple medium‐sized cysts with large areas of noncystic parenchyma. Type III is characterized by large numbers of small‐ and medium‐sized cysts spread diffusely throughout the parenchyma with only minimal, normal areas.5

Table 3.

The Schnelldorfer Classification Relates Symptom Burden to the Number of Liver Sectors Involved

| Type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |

| Symptoms | Absent or mild | Moderate or severe | Severe | Severe |

| Cyst findings | Focal | Focal | Diffuse | Diffuse |

| Normal hepatic segments | >3 | >2 | >1 | <1 |

| Portal vein/hepatic vein occlusion | No | No | No | Yes |

The liver sectors are left lateral sector, left medial sector, right anterior sector, and right posterior sector.

Adapted with permission from World Journal of Gastroenterology.5 Copyright 2013, the authors. Published by Baishideng Publishing Group, Inc.

Initiate Treatment

Treatment is reserved for symptomatic patients. The goal is to minimize symptoms and improve quality of life by reducing the progressive increase in cyst size. High estrogen exposure through pregnancy, oral contraceptives, and estrogen‐replacement therapy are associated with more severe PLD; therefore, avoidance of estrogen‐ and progesterone‐containing oral contraceptives or intrauterine devices in women with PLD is recommended.1

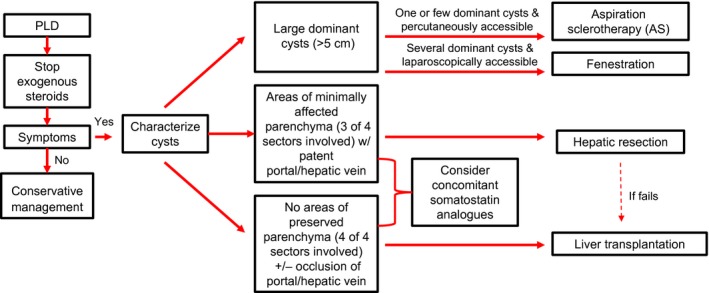

Current available medical treatment includes somatostatin analogues (e.g., octreotide, lanreotide). These agents inhibit cyclic adenosine monophosphate production, which results in reduced epithelial proliferation, as well as a reduction in transepithelial chloride secretion of the cholangiocytes lining the hepatic cysts.1 Three randomized prospective clinical trials demonstrated a 2.9% to 4.9% decrease in total liver volume (TLV) at 6 to 12 months. Importantly, liver cyst infection was a noted complication in these trials, and further study is needed to determine the effects of long‐term treatment.2 Consideration for use should be restricted to symptomatic patients who demonstrate a large TLV (e.g., Schnelldorfer types C and D) and are unable to undergo surgical interventions (Fig. 2); there are no data to support preemptive use in asymptomatic individuals.2 However, it should be noted that the off‐label use of these medications can make them difficult to obtain in the United States.

Figure 2.

Algorithm for the medical and surgical management of PLD. Conservative management is indicated for patients who are asymptomatic; treatment is indicated only for patients with symptoms. Adapted with permission from Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.2 Copyright 2017, Elsevier.

More invasive treatments include aspiration sclerotherapy (AS), liver cyst fenestration, hepatic resection, and LT. AS involves percutaneous cyst fluid aspiration with injection of a sclerosing agent to destroy the epithelial lining and prevent future fluid secretion. AS is a safe and efficacious technique for patients who have one or a few large, dominant cysts with diameters greater than 5 cm.7 The majority of patients report an improvement (72%‐100%) and complete resolution of symptoms (56%‐100%). Cyst volume reduction ranges from 76% to 100%.7 A common complication is postprocedural pain from peritoneal irritation.

Cyst fenestration combines aspiration and surgical deroofing of cysts. This surgical approach can treat more dominant cysts in one session than AS can, but complication and symptom recurrence rates are not negligible (23% and 22%‐24%, respectively). A laparoscopic approach is preferred but is not feasible for cysts in posterior segments or near the dome of the liver.2

Partial or segmental hepatic resection can be performed in patients with significant cyst burden in specific liver segments. Hepatic resection has significant morbidity (51%) and patient mortality (3%) associated with it. Furthermore, it complicates future LT because of the high occurrence of postsurgical adhesions.2

LT definitively cures PLD, but it is appropriate in only a small number of patients, including those with extensive TLV and therapeutically refractory complications. Because PLD patients have preserved synthetic liver function, they often have very low Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores, and exception points need to be obtained.8 The guidance for application for MELD exception points proposed by United Network for Organ Sharing states that points may be granted to patients with Schnelldorfer types C (with prior resection/fenestration) and D with at least two of the following: hepatic decompensation, concurrent renal failure (on dialysis), and/or compensated comorbidities. Historically, severe malnutrition was also taken into consideration when requesting exception points.1, 5, 9

Conclusion

A practical approach to a patient with PLD includes clinically distinguishing between ADPKD and ADPLD, determining the presence of symptoms, and characterization of cyst burden with TLV measurements. These steps are essential to determining the appropriate therapy for the patient.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Van Aerts RM, Van de Laarschot LF, Banales JM, et al. Clinical management of polycystic liver disease. J Hepatol 2018;68:827‐837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mikolajczyk AE, Te HS, Chapman AB. Gastrointestinal manifestations of autosomal‐dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:17‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Eckardt K‐U, et al. Autosomal‐dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): executive summary from a kidney disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2015;88:17‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cnossen WR, Drenth JPH. Polycystic liver disease: an overview of pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014;9:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abu‐Wasel B, Walsh C, Keough V, et al. Pathophysiology, epidemiology, classification and treatment options for polycystic liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:5775‐5786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pei Y, Obaji J, Dupuis A, et al. Unified criteria for ultrasonographic diagnosis of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:205‐212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wijnands T, Görtjes A, Gevers T, et al. Efficacy and safety of aspiration sclerotherapy of simple hepatic cysts: a systematic review. Am J Roentgenol 2017;208:201‐207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arrazola L, Moonka D, Gish RG, et al. Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease (MELD) exception for polycystic Liver disease. Liver Transpl 2006;12:110‐111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rodriguez PS, Barritt AS, Gerber DA, et al. Liver transplant for unusually large polycystic liver disease: challenges and pitfalls. Case Rep Transplant 2018;2018:4863187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Luciano RL, Dahl NK. Extra‐renal manifestations of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): considerations for routine screening and management. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;29:247‐254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]