Abstract

Microtubules are dynamic polymers, which grow and shrink by addition and removal of tubulin dimers at their extremities. Within the microtubule shaft, dimers adopt a densely packed and highly ordered crystal-like lattice structure, which is generally not considered to be dynamic. Here we report that thermal forces are sufficient to remodel the microtubule shaft, despite its apparent stability. Our combined experimental data and numerical simulations on lattice dynamics and structure suggest that dimers can spontaneously leave and be incorporated into the lattice at structural defects. We propose a model mechanism, where the lattice dynamics is initiated via a passive breathing mechanism at dislocations, which are frequent in rapidly growing microtubules. These results show that we may need to extend the concept of dissipative dynamics, previously established for microtubule extremities, to the entire shaft, instead of considering it as a passive material.

Microtubules are self-organized tubular scaffolds serving as tracks for intra-cellular transport. They are dynamic dissipative structures, which grow or shrink primarily by tubulin dimer addition or removal at their extremities. Their non-equilibrium behavior results from the irreversible hydrolysis of GTP1,2 and manifests itself as stochastic transitions between growth and shrinkage phases, called dynamic instability2–6. For three decades, a substantial effort in microtubule research has been dedicated to the study of the dynamic instability at the microtubule tips7. In contrast, only little is known about the dynamical properties of the microtubule shaft8. A first hint that the shaft is dynamic came from the observation of end-stabilized microtubules in the absence of free tubulin. Microtubules started to soften in a localized region and eventually broke apart. Breakage of soft regions could be prevented by reintroducing GTP-tubulin into the solution, suggesting that both, dimer loss and incorporation, occurred along the shaft9. More recently, Schaedel et. al.10 demonstrated that microtubules, subjected to short (~10 seconds) repeated cycles of bending, softened and incorporated free tubulin dimers into the shaft. Reid et al.11 showed tubulin incorporation into the shaft of stabilized microtubules containing massive structural defects. Others have detected GTP-tubulin islands along the shaft12,13, potentially resulting from a dynamic tubulin turnover in the shaft. Live cell imaging revealed that sites of tubulin turnover also exist in vivo, predominantly in microtubule bundles or at intersections between two microtubules13,14. Recently, it was shown that microtubule severing enzymes, such as spastin and katanin, are able to actively remove tubulin dimers from the shaft. The ensuing gaps in the lattice are repaired rapidly by the incorporation of free tubulin15. Estimates of the change in free energy upon transferring a dimer from the fully occupied lattice into the surrounding medium range from 35 kBT to 80 kBT16–18, suggesting that spontaneous dimer loss is not relevant during the lifetime of a microtubule. However, it is known that the microtubule lattice is not perfect but exhibits defects, such as missing dimers, cracks and dislocations19–24. Here, we combine data of tubulin turnover obtained by TIRF microscopy and structural data obtained by cryo-electron microscopy with kinetic Monte Carlo modeling to elucidate the origin of the lattice turnover. Our data support the idea that the elastic stress associated with structural lattice defects is sufficient to promote a spontaneous localized tubulin turnover on the timescale of minutes, even in the absence of external forces. We propose a robust and simple breathing mechanism that relates lattice turnover to the presence of dislocation defects. Our simulations capture the dynamic instability at the tip, as well as the localized turnover in the shaft, thus extending the concept of microtubule dynamics from the tip to the shaft.

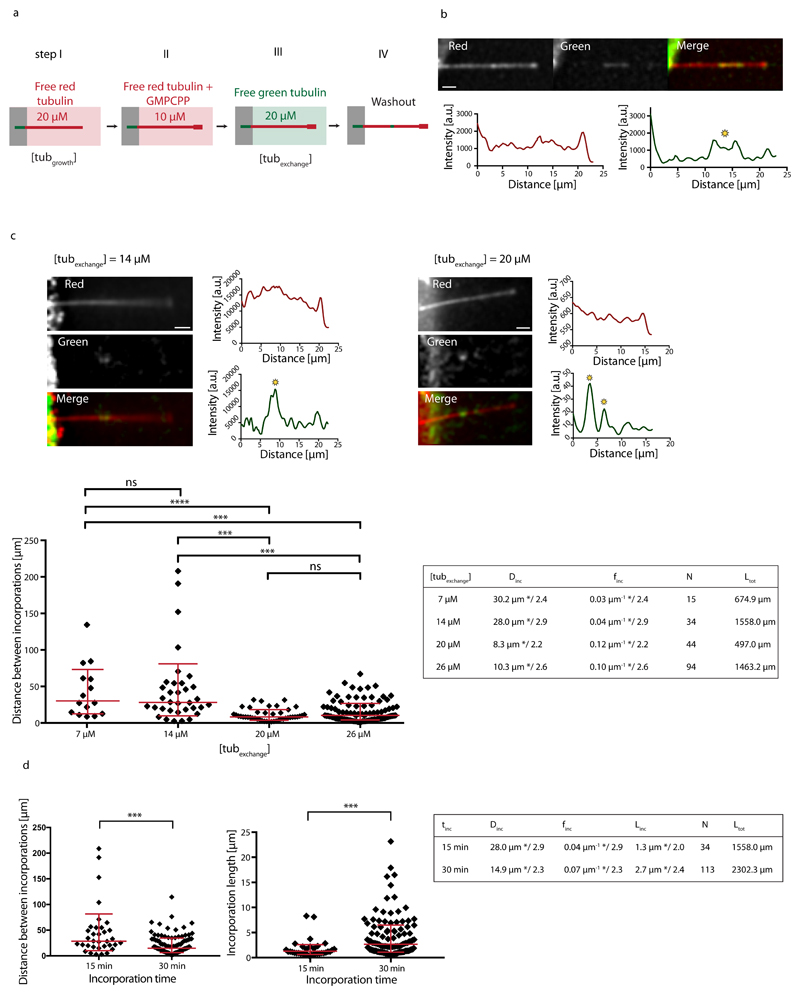

To test the possibility of spontaneous dimer turnover we polymerized microtubules in vitro from purified brain tubulin25. As depicted in Fig. 1a, dynamic microtubules were nucleated from short taxol-stabilized microtubule seeds and elongated in the presence of 20 μM of free tubulin dimers (“tubulin growth” condition), 20% of which was labeled with red fluorophores. Importantly, microtubules were not stabilized with taxol, which is known to impact the lattice structure11,26,27. Microtubule ends where then capped with GMPCPP tubulin, a non-hydrolysable analog of GTP, to protect them from depolymerization. Capped microtubules were exposed to 20 μM of free tubulin dimers labeled with a green fluorophore for 15 minutes (“tubulin exchange” condition). After washout of the free tubulin, green tubulin spots of micrometer size became apparent along microtubule shafts (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S1a). This method revealed that tubulin incorporation occurs spontaneously, i.e. in the absence of external mechanical forces. To test the dependence of the incorporation on the free tubulin concentration, microtubules generated in the tubulin-growth process (step I in Fig. 1a) were exposed to different concentrations of free green-fluorescently labeled tubulin in the tubulin-exchange process (step III in Fig. 1a). Sites of incorporated tubulin were identified using line scans of the green-fluorescence intensity along the microtubule (Fig. 1b,c and Methods). We analyzed incorporation by randomly concatenating all microtubules and by measuring the distance between adjacent incorporation spots. The resulting distribution of distances (Fig. 1c) is skewed and better described by geometric mean */ geometric standard deviation (sd) factor, than by arithmetic mean ± sd28. At low free tubulin concentrations (7 μM and 14 μM) the typical spatial frequencies of incorporation sites (finc=0.03 μm-1 */2.4 and finc=0.04 μm-1 */2.9, respectively) are not significantly different. Upon increasing the free tubulin concentration to 20 μM, the typical frequency increases significantly to finc=0.12 μm-1 */2.2. Increasing the free tubulin concentration to 26 μM does not significantly further increase the typical frequency (finc=0.10 μm-1 */2.6). We conclude that tubulin incorporation depends critically on the concentration of free tubulin. Furthermore, tubulin incorporation is a continuous process, whereby the frequency and length of incorporation spots at 14 μM free tubulin increases between 15 and 30 min of incorporation (Fig. 1d). The increase in spot size allows us to estimate the growth speed of the incorporation spots to about 0.09 μm/min. The increase in the frequency of incorporation spots over time (Fig. 1d) could potentially be the result of two different mechanisms. i) Small incorporation spots that are undetectable at short incorporation times become bigger and therefore visible after longer incorporation times or ii) new incorporation spots are nucleated over time along the microtubule shaft. We will come back to the distinction between the two mechanisms later. The mean size of incorporation spots after 15 min of incubation increases slightly with the free tubulin concentration (Supplementary Fig. S1b), indicating that although the appearance of incorporation spots depends critically on the free tubulin concentration, a higher tubulin concentration (above a critical concentration) favors a faster growth of incorporation spots. In summary, the incorporation of tubulin into microtubules in the absence of external constraints suggests a genuine spontaneous and continuous process of tubulin turnover.

Figure 1.

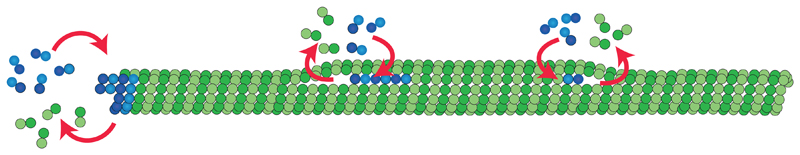

Incorporation of free tubulin into the microtubule lattice visualized by TIRF. (a) Schematic representation of the experimental setup used to test microtubule-lattice turnover in the absence of external forces. Microtubules were grown with red-fluorescent tubulin at a concentration of 20 μM (step I) before they were capped with GMPCPP (step II) and exposed to green-fluorescent free tubulin at a concentration of 20 μM (step III). After 15 min, the green tubulin was washed out to reveal spots of green tubulin along the red microtubule (step IV). (b) Example of a red microtubule showing spots of incorporated green tubulin along the lattice. The graphs represent line scans along the microtubule (red curve: red fluorescent channel, green curve: green fluorescent channel). Sites of incorporated tubulin were identified as zones of fluorescence intensity, which were at least 2.5-fold higher than the background fluorescence (see yellow star). Scale bar: 3 μm. (c) Microtubules grown at 20 μM tubulin concentration were exposed to 7 μM, 14 μM, 20 μM and 26 μM of green-fluorescent free tubulin [step III in (a)]. The images and line scans represent typical examples for 14 μM and 20 μM as described in (b). Scale bars: 3 μm. The graph shows the distribution of distances between incorporation spots after concatenating all microtubules in a random order. The red bars indicate the geometric mean*/sd factor. p-values are <0.001 (7 and 14 μM vs. 20 and 26 μM). The table summarizes the average distance Dinc and frequency finc (geometric mean */sd factor) of incorporation spots. (d) Comparison of distances between incorporations (left) and lengths of incorporation spots (right) for two different incubation times (15 min and 30 min) at 14 μM free tubulin in step III of (a). p-values are <0.001. The table summarizes the average distance Dinc, frequency finc and size Linc of incorporation spots (geometric mean */sd factor) for each incubation time tinc. The estimated speed of elongation of the incorporation spots is v≈Linc/tinc≈0.09 μm/min. Ltot and N in the tables in (c,d) denote the total length of microtubules analyzed and the total number of observed incorporation spots, respectively.

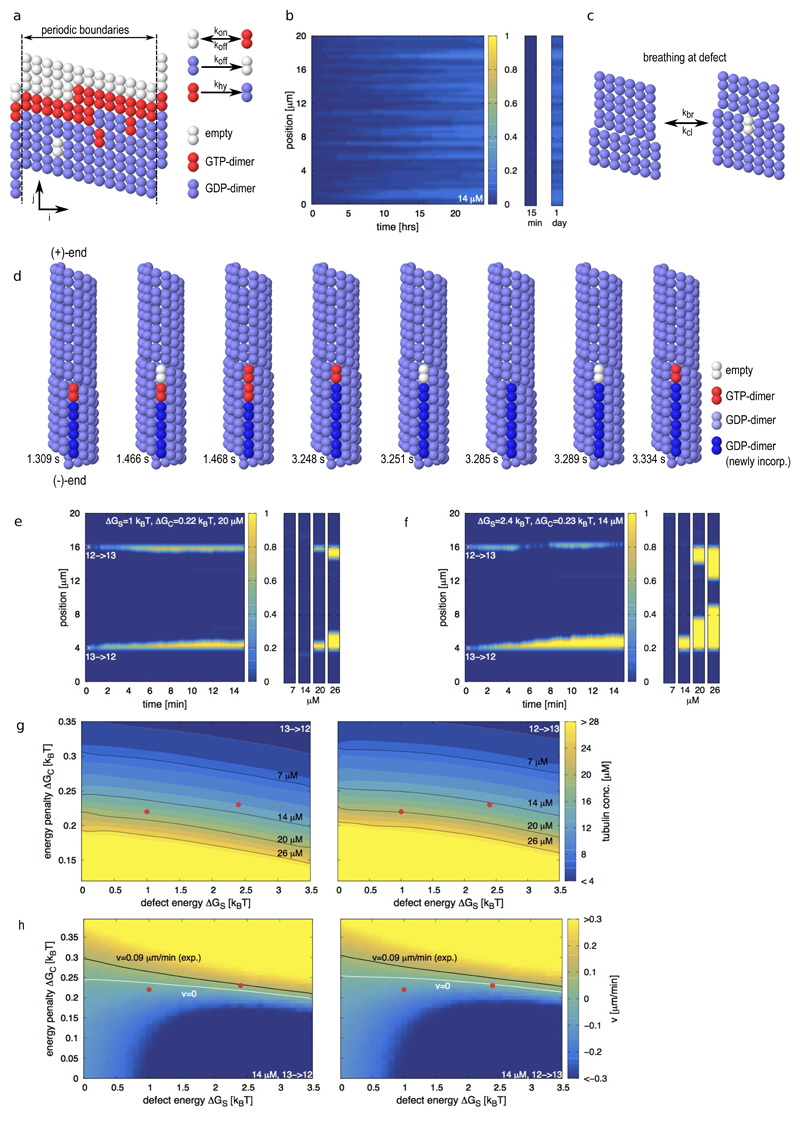

How is a spontaneous localized tubulin turnover possible in such a highly ordered structure as the microtubule shaft? Using lower estimates for the binding energy and taking into account the entropic loss upon dimer polymerization, the typical time for a dimer to leave the lattice of a 20 μm long microtubule ranges between 15 min and 3 hours (see Supplementary Information and Supplementary Fig. S2a). Given the stochastic nature of chemical reactions, and the fact that dimer loss occurs in a cooperative manner (the loss of the first dimer reduces the time for the loss of the next neighbors), we felt it worthwhile to test whether the loss or incorporation of dimers at the perfect shaft could reproduce the experimentally observed localized exchange pattern (Fig. 1b,c). To that end we developed a simple, albeit robust, kinetic Monte-Carlo model (Fig. 2a and Methods) for the canonical microtubule lattice (13 protofilaments, 3 start left-handed helix29,30), referred to in the following as the 13 protofilament lattice. Similar types of Monte Carlo models have been used to study the microtubule tip dynamics16,31,32. Here, we specifically allowed for the exchange of dimers between the microtubule shaft and the surrounding solution, which had not been considered previously. The model parameters (see Supplementary Table S1) are comparable to values found in the literature and are adapted to reproduce dynamic instability of the microtubule (+)-end (Supplementary Fig. S2b). To investigate the experiments of end-stabilized microtubules shown in Fig. 1, we simulated the exchange of dimers between 20 μm long microtubule shafts and the solution containing 14 μM free tubulin (Fig. 2b). A single dimer occasionally left the lattice, however the open lattice space was rapidly filled, before more neighboring dimers could leave the lattice. Thus, the frequency of dimer exchange between the lattice and the pool of free dimers during the first 15 minutes was considered too low to be detectable experimentally. Within one day, the shaft exchanged about 1 dimer per 5 helical turns with the solution in an almost homogeneous fashion. Therefore, a regular lattice cannot explain the localized exchange pattern. We hypothesized that the elastic stress, associated with dislocation defects, might be sufficient to promote a spontaneous localized tubulin turnover. We therefore extended our Monte-Carlo model to simulate the microtubule dynamics at transitions between 12 and 13 protofilament lattice conformations via dislocation defects. Thereby we postulated (i) that a passive lattice breathing mechanism occurs at the defect site (Fig. 2c); (ii) that the defect is associated with an elastic strain energy ΔGS; and (iii) that the 12 protofilament lattice is slightly less stable than the 13 protofilament lattice33 by a small conformational energy penalty ΔGC. As an illustration, Fig. 2d shows snapshots of a numerical simulation of a 13→12 dislocation [the arrow indicates the direction of the (+)-end] in the presence of free tubulin. Shown are consecutive single events in the Monte Carlo model, e.g. breathing, incorporation and loss of tubulin-dimers and hydrolysis. Thereby the position of the dislocation is moving along the microtubule long axis. For the 13→12 dislocation depicted in Fig. 2d a motion of the dislocation towards the (+)-end leads to an elongation of the additional protofilament, i.e. free tubulin is incorporated into the microtubule. A motion of the dislocation towards the (-)-end leads to a depolymerization of the additional protofilament, corresponding to a loss of tubulin-dimers from the microtubule. With this model we simulated the exchange of dimers for microtubule shafts containing two dislocation defects, a 13→12 and a 12→13 transition. Fig. 2e shows a kymograph for the tubulin incorporation into the shaft over 15 min at a free tubulin concentration of 20 μM. Also shown are the final states of the microtubule shaft at varying free tubulin concentrations. In this example, tubulin incorporation is not detectable at low tubulin concentrations (7 and 14 μM). However, both dislocations are incorporating free tubulin at higher tubulin concentrations (20 and 26 μM), whereby an increase in the tubulin concentration leads to longer incorporation stretches. This example shows two important experimental features (Fig. 1c): Tubulin incorporation is localized at dislocations and requires a critical concentration of free tubulin. Fig. 2f shows a simulated kymograph of tubulin incorporation for a different set of parameters that demonstrates the effect of the directionality of the protofilament transition. At 14 μM the 13→12 transition is incorporating free tubulin, whereas the 12→13 transition is not. At a higher tubulin concentration of 20 μM both transitions are incorporating free tubulin. The different dynamics of the two types of defects arise from the fact, that hydrolysis of a GTP-dimer can only occur if its top neighbor site [in the direction of the (+)-end] is occupied (see Methods), reminiscent of the different dynamic properties of (+) and (-)-microtubule tips3. Figs. 2g and h present how the tubulin incorporation varies with the properties of the 13→12 and 12→13 transitions. For comparison, the black line in Fig. 2h shows the experimentally measured elongation speed of incorporation spots (see Fig. 1d, ~0.09 μm/min at 14 μM free tubulin), which allows us to approximately situate our experiments in the model parameter space. Supplementary Figs. S2c,d and S3 show further phase diagrams for other parameter combinations. We have further tested the model behavior by comparing it to experiments with end-stabilized microtubules (grown at 20 μM free tubulin) in the complete absence of free tubulin. The dynamics and typical time scale of microtubule breakage matched well between simulations and experiments and confirmed also the observations of Dye et al.9 albeit on a shorter time scale (see Supplementary Information and Supplementary Fig. S4). Overall, the breathing mechanism reproduces the localized and continuous incorporation of tubulin into the shaft with a critical dependency on the free tubulin concentration, as observed experimentally (Fig. 1 c and d). In the model, dimer incorporation occurs only by elongation of free protofilament ends. It is straightforward to include a destabilization of neighboring protofilaments close to the dislocation into the model to extend the incorporation spots laterally. However, as a proof of principle, our simple model captures well the measured data. The breathing mechanism allows for a dynamic lattice restructuring by guaranteeing at the same time an overall stable lattice with little impact on overall microtubule appearance (width and curvature).

Figure 2.

Monte-Carlo simulations of microtubule lattice dynamics. (a) Lattice scheme for a 13 protofilament lattice with a seam (left) and possible lattice transitions with their associated rate constants (right). (b) Simulated kymograph of the incorporation of free tubulin dimers into the microtubule shaft of and end-stabilized 13 protofilament microtubule within 24 hours. The free tubulin concentration is 14 μM. The small graphs on the right are representative for the microtubule appearance at the indicated times. The color scale indicates the number of incorporated dimers per helical turn. (c) Scheme of the breathing mechanism of the microtubule lattice at a dislocation defect. (d) Sequence of simulation snapshots of tubulin turnover at a dislocation defect, where the protofilament number changes from 13 to 12 into the direction of the microtubule (+)-end. The snapshots correspond to consecutive single events in the Monte Carlo model with the simulation times indicated below. (e,f) Simulated kymographs of the incorporation of free tubulin dimers into the microtubule shaft containing defects, whose initial position is marked by the white asterisk. The defect strain energy ΔGS, the conformational energy penalty ΔGC and the free tubulin concentration are indicated in the top region of each kymograph. The small graphs on the right show snapshot of the incorporation pattern after 15 min at the indicated free tubulin concentrations below each snapshot. The color code indicates the number of incorporated dimers per helical turn. (g) Phase diagrams of the critical concentration of tubulin incorporation depending on the conformational energy penalty ΔGC and the defect strain energy ΔGS. The color code indicates the critical free tubulin concentration where the dislocation is stationary. Shown are the phase diagrams of a 13→12 (left) and a 12→13 (right) transition. The black lines indicate the isolines of the experimentally used free tubulin concentrations. (h) Phase diagrams of the speed of motion of dislocations depending on the conformational energy penalty ΔGC and the defect strain energy ΔGS for a free tubulin concentration of 14 μM. Shown are the phase diagrams of a 13→12 (left) and a 12→13 (right) transition. The color code indicates the speed of motion of the dislocation along the microtubule axis in μm/min. Note, that a positive speed v>0 indicates a net elongation of the free profofilament end at the dislocation, which gets visible as tubulin incorporation spots in the experiments. The white line indicates a stationary dislocation with v=0 and the black line indicates the experimentally measured incorporation speed (~0.09 μm/min at 14 μM free tubulin). The red dots in (g,h) indicate the parameter combinations for the simulations of (e) and (f). Remaining parameters for all simulations are as in Supplementary Table S1 with ΔGS=2.4 kBT and ΔGC=0.23 kBT in (d).

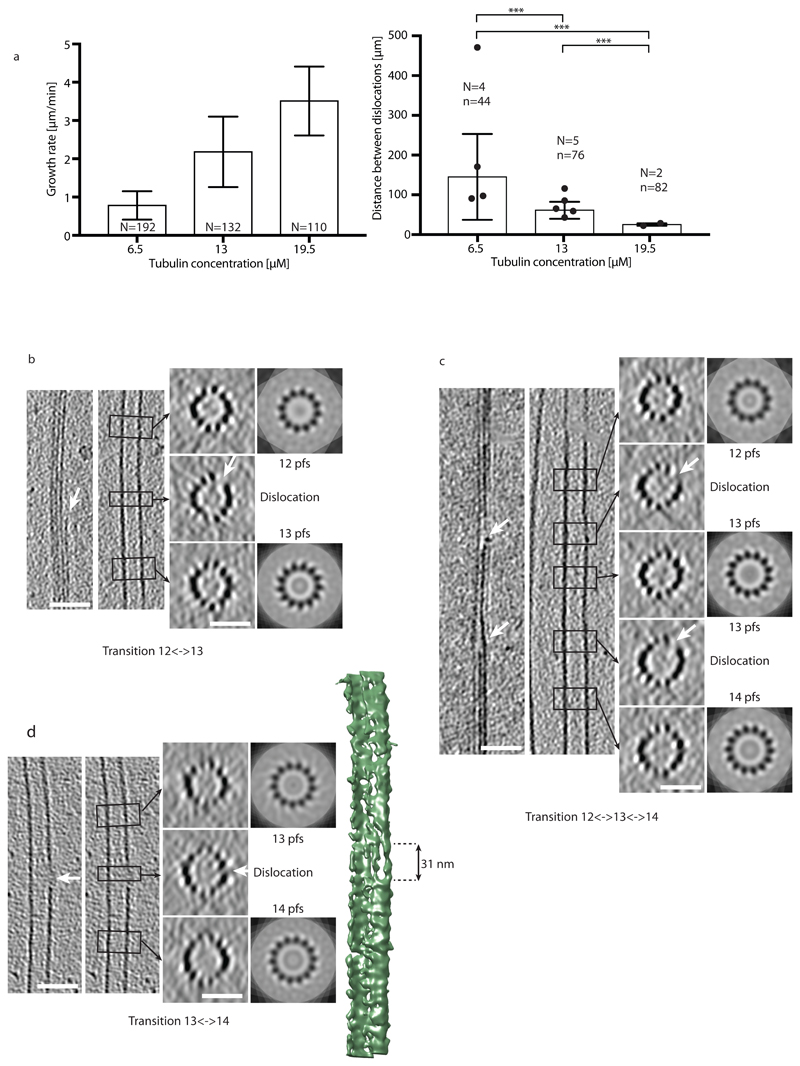

Dislocations are the predominant defect structures, which can be detected by cryo-electron microscopy19,20. However, their dynamics has not been characterized yet. Since the direct observation of tubulin incorporation at defects was too challenging, we decided to establish the link between defects and lattice turnover indirectly. It has previously been hypothesized that the defect frequency increases with the microtubule growth speed, i.e. the concentration of free tubulin during elongation10,34. Therefore, we investigated the effect of tubulin concentration, and hence of microtubule growth rate, on the frequency of lattice defects using previously acquired cryo-electron microscopy data (Fig. 3). Since dislocations could result from annealing of self-assembled microtubules with different lattice conformations and to facilitate the visualization of elongating plus ends, we choose to grow microtubules from centrosomes at tubulin concentrations below the critical concentration for self-assembly35. While the vast majority of the microtubules were in the 13_3 conformation (13 protofilament, 3 start helix) in these conditions, we also detected other lattice conformations, e.g. 14_3 and 12_3 lattice conformations. Transition types were preferentially single changes in protofilament numbers, e.g., 13→12, 13→14 and 14→13 (see Supplementary Information and Supplementary Fig. S5a). We characterized the growth rate and the dislocation frequency as a function of tubulin concentration at assembly (6.5 μM, 13 μM and 19.5 μM, see Methods). Both, the microtubule growth rate and the dislocation frequency increased with increasing tubulin concentration (Fig. 3a and b). Furthermore, the defect frequency detected by cryo-electron microscopy (0.007±0.005 μm-1, 0.016±0.005 μm-1, and 0.040±0.005 μm-1 for tubulin concentrations of 6.5 μM, 13 μM, and 19.5 μM) is comparable to the frequency of tubulin incorporation observed by TIRF microscopy (Table 1 and 2). Note that a direct comparison of the frequencies is difficult, since microtubules were grown under different conditions for TIRF and cryo-electron microscopy observations. In our breathing model (Fig. 2c), we proposed that the opening of the lattice close to the dislocation allows for the incorporation of free tubulin. Indeed we could visualize a gap in the lattice structure in the vicinity of a protofilament dislocation in three dimensions based on microtubule reconstructions from cryo-electron tomography at medium resolution and in the absence of averaging methods36 (Fig. 3b-d and Supplementary Fig. S5b-e). Fig. 3d shows the surface of a microtubule with a gap of about 31 nm in length in the transition region, suggesting that tubulin can indeed be added at the free ends of protofilaments at dislocations.

Figure 3.

Dislocation defects in the microtubule lattice detected by cryo-electron microscopy. (a) Growth rate (left) and mean distances between dislocations (right) in centrosome-nucleated microtubules as a function of the free tubulin concentration. N in the left graph denotes the number of microtubules analyzed. N and n in the right graph denote the number of cryo-electron microscopy samples analyzed and the total number of dislocations detected, respectively (see Methods and Supplementary Information). Mean±sd values for the spatial frequencies of dislocations are 0.007±0.005 μm-1, 0.016±0.005 μm-1 and 0.040±0.005 μm-1 for 6.5 μM, 13 μM and 19.5 μM free tubulin, respectively. All p-values are <0.001. (b-d) Cryo-electron tomograms of protofilament number transitions. The left panels show longitudinal slices through the microtubule in the transition region whereas the right panels show transverse sections. The left longitudinal section shows a cut through the transition region, whereas the right longitudinal section shows a cut through a central part of the microtubule. The transverse sections are averaged over the height of the black rectangles shown in the longitudinal sections (corresponding regions are indicated by black arrows) and correspond to N-fold rotational averages of the closed microtubule regions (N denotes the protofilament number). White arrows indicate the free end of a protofilament (dislocation) with the accompanying gap in the lattice at the transition. The scale bars are 50 nm for longitudinal and 25 nm for transverse sections. (b) 12⌦13 protofilament number transition. (c) 12⌦13 and 13⌦14 protofilament number transitions in close proximity in the same microtubule. (d) 13⌦14 protofilament number transition. The image to the far right shows the 3D rendering of the microtubule with the dislocation at the edge of the microtubule. A gap in the lattice with an approximate length of 31 nm is clearly visible. In (d) both longitudinal sections are identical.

Table 1.

Summary of mean frequencies of tubulin incorporation spots observed by TIRF for various growth and exchange conditions after 15 min of tubulin incorporation. Shown is also the sd factor characterizing the width of the lognormal distribution, as well as the total length of microtubules analyzed and the total number of incorporation spots.

| Tubulin concentration (elongation) [μM] |

Tubulin concentration (incorporation) [μM] |

Total length analyzed (μm) |

Number of incorporation spots | Incorporation frequency (mean */ sd factor) [μm-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 7 | 675 | 15 | 0.03 */ 2.4 |

| 20 | 14 | 1558 | 34 | 0.04 */ 2.9 |

| 20 | 20 | 497 | 44 | 0.12 */ 2.2 |

| 20 | 26 | 1463 | 94 | 0.10 */ 2.6 |

| 14 | 20 | 149 | 8 | 0.08 */ 1.8 |

| 20 | 20 | 497 | 44 | 0.12 */ 2.2 |

| 26 | 20 | 377 | 65 | 0.23 */ 2.0 |

| 20 (Xenopus egg extract) | 14 | 3278 | 210 | 0.09 */ 2.8 |

Table 2.

Lattice-defect frequency (mean ± sd) in centrosome-nucleated microtubules observed by Cryo-electron microscopy for various concentrations of tubulin during elongation. Also shown is the total length of microtubules analyzed and the total number of defects.

| Tubulin concentration [μM] |

Total length analyzed [μm] |

Number of lattice defects | Lattice defect frequency (mean ± sd) [μm-1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6.5 | 6385 | 44 | 0.007 ± 0.005 |

| 13 | 4673 | 76 | 0.016 ± 0.005 |

| 19.5 | 2056 | 82 | 0.040 ± 0.005 |

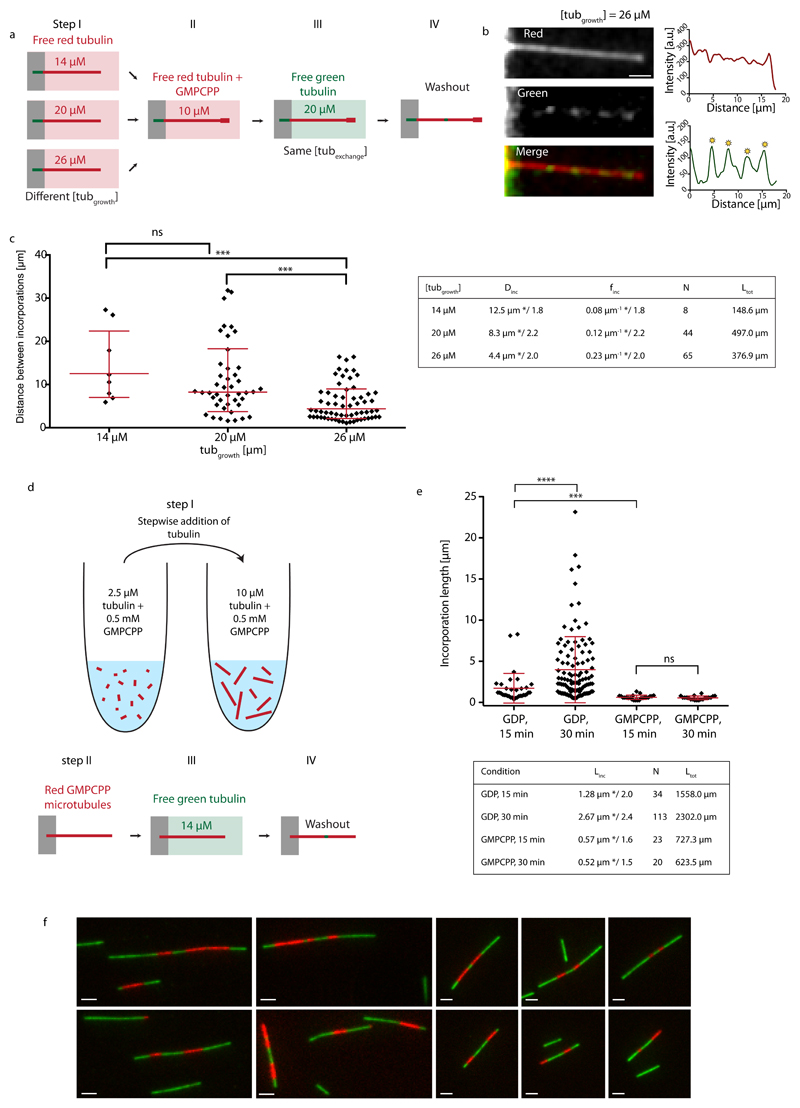

We then took advantage of the correlation between microtubule growth rate and lattice defect frequency. Red microtubules were grown at various concentrations of free tubulin, capped and exposed to the same concentration of green tubulin (20 μM) for 15 min (Fig. 4a and b). Microtubules grown at 14, 20 and 26 μM showed frequencies of incorporations of 0.08 μm-1*/1.8, 0.12 μm-1*/2.2 and 0.23 μm-1*/2.0, respectively (Fig. 4c). This clearly demonstrates that higher defect frequencies from structural data are associated with higher frequencies for incorporation sites from TIRF data. It indicates that tubulin incorporation is related to specific lattice structures and not an unspecific aggregation of tubulin at the shaft. It also invalidates the previously mentioned hypothesis (Fig. 1d), that incorporation sites are continuously nucleated along the shaft, as both processes, unspecific aggregation and continuous nucleation of incorporation spots, should be independent of the speed, at which microtubules were polymerized.

Figure 4.

Incorporation of free tubulin into the microtubule lattice visualized by TIRF. (a) Schematic representation of the experimental setup to test the role of the microtubule growth rate (i.e. lattice-defect frequency) on tubulin turnover in the microtubule lattice. Microtubules were grown in 14 μM, 20 μM or 26 μM red-fluorescent free tubulin (step I) before capping with GMPCPP (step II). Microtubules were then exposed to 20 μM green-fluorescent free tubulin for 15 min (step III) before washout and imaging (step IV). (b) The images and line scans (red curve: red fluorescent channel, green curve: green fluorescent channel) show an example of a microtubule grown at a free tubulin concentration of 26 μM, which contains several incorporation spots marked by the yellow asterisks. Scale bar: 3 μm. (c) The graph shows the distribution of distances between incorporation sites after concatenating all microtubules in a random order. Red bars represent the geometric mean*/sd factor. p-values are <0.001 for the concentration pairs (20 μM, 26 μM) and (14 μM, 26 μM). The table summarizes the mean distance (Dinc) and frequency (finc) between incorporation spots (geometric mean */sd factor). N and Ltot denote the total number of observed incorporation spots and the total length of microtubules analyzed, respectively. (d,e) Incorporation of free tubulin into GMPCPP-microtubules. (d) Schematic representation of the experimental setup used to test microtubule lattice turnover in GMPCPP-microtubules. Red labeled GMPCCP microtubules were first polymerized in a test tube by the step-wise addition of GMPCPP-tubulin (step I), before being transferred and fixed to the bottom of a passivated microfluidic chamber (step II). GMPCPP-microtubules were then exposed to green labeled free tubulin for 15 or 30 min (step III). Prior to imaging, the free tubulin was washed out (step IV). (e) The graph shows the distributions of the length of tubulin incorporation spots (Linc) into the GMPCPP-lattice (and the GDP-lattice for comparison, see Fig. 1d) after 15 and 30 min of incubation at 14 μM free tubulin. The red bars indicate the geometric mean*/sd factor, which are also summarized in the table (N and Ltot denote the total number of observed incorporation spots and the total length of microtubules analyzed, respectively.). (f) Alternating patterns of red and green labeled tubulin along GMPCPP-microtubules which indicate annealing. In a separate experiment from the scheme indicated in (d), to show microtubule annealing, microtubules were first polymerized in a test tube from red labeled GMPCPP-tubulin and then elongated with green GMPCPP-tubulin. The simple pattern green-red-green shows the initial red tubulin stretch, which was elongated at the (+)- and (-)-ends by green tubulin. The alternating pattern green-red-green-red-green indicates annealing between two microtubules.

The role of structural defects in lattice turnover suggests that a perfect lattice would display a different dynamics. We aimed at testing this prediction by growing microtubules from GMPCPP-tubulin as they exist almost exclusively (96 %) in the 14 protofilament lattice configuration, in contrast to the polymorphism of the GDP lattice37 (see also our Supplementary Data). To that end microtubules were polymerized from GMPCPP-tubulin in a test tube and transferred into the microfluidic chamber to perform the incorporation experiment (Fig. 4d and Methods). GMPCPP-microtubules showed tubulin incorporation, however the incorporation spots were smaller than in our previous experiments (Fig. 4e), suggesting they were annealing sites rather than actual sites of lattice turnover. To test this possibility we performed another experiment aimed at highlighting annealing events. We polymerized short red labeled GMPCPP-microtubules, which were elongated at the (+) and (-)-end using green labeled tubulin in a test tube (Methods), resulting in microtubules with typical stripe patterns green-red-green or green-red-green-red-green (Fig. 4f), which testified from the occurrence of numerous annealing events. Moreover, the incorporation spots did not elongate between 15 and 30 min of incorporation (Fig. 4e) in contrast to the lattice turnover sites we observed previously, suggesting that the incorporation stopped when the annealing was completed. We conclude, that incorporation of free tubulin occurred preferentially at annealing sites between microtubules with frayed ends and rarely along the regular GMPCPP shaft.

To test the occurrence of turnover in more physiological conditions where microtubule binding proteins accompany the growth of microtubules, we performed the incorporation experiment for microtubules grown in Xenopus egg extract cytoplasm and also in an alternative TicTac buffer (Supplementary Information and Supplementary Figs. S6 and S7). Both experiments showed tubulin incorporation with frequencies comparable to the in vitro setup using BRB buffer (see Tables 1 and 2). In a final set of experiments we roughly quantified the number of incorporated dimers. We found that small incorporation spots ≤ 1 μm contained several tens of fluorescent dimers (Supplementary Information and Supplementary Fig. S8), in agreement with our model mechanism, where a single protofilament elongates at the dislocation.

Localized tubulin incorporations have been observed in living cells and attributed to mechanical stresses in the lattice13,14. Our in vitro experiments now suggest that dimer loss and incorporation may occur spontaneously in the absence of mechanical stress. Furthermore, our model simulations and the correlation between fluorescence data and structural data indicate, that a spontaneous and localized lattice turnover may occur in the vicinity of lattice defects (Fig. 5), which are frequent in rapidly growing microtubules. A simple passive breathing model for dislocation defects shows that dislocations with a strain energy as weak as the thermal energy kBT are sufficient to induce lattice plasticity and tubulin turnover.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of microtubule dynamics, showing elongation and shortening of the microtubule at the tip and elongation and shortening of free protofilament ends at dislocations along the shaft.

Methods

Tubulin purification and labeling

Tubulin was purified from fresh bovine brain by three cycles of temperature-dependent assembly and disassembly in Brinkley Buffer 80 (BRB80 buffer; 80 mM PIPES, pH 6.8, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM MgCl2 plus 1 mM GTP38). MAP-free neurotubulin was purified by cation-exchange chromatography (EMD SO, 650 M, Merck) in 50 mM PIPES, pH 6.8, supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EGTA39. Purified tubulin was obtained after a cycle of polymerization and depolymerization. Fluorescent tubulin (ATTO-488 and ATTO-565-labeled tubulin) and biotinylated tubulin were prepared as previously described40. Microtubules from neurotubulin were polymerized at 37°C for 30 min and layered onto cushions of 0.1 M NaHEPES, pH 8.6, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 60% v/v glycerol, and sedimented by high centrifugation at 30°C. Then microtubules were resuspended in 0.1 M NaHEPES, pH 8.6, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 40% v/v glycerol and labeled by adding 1/10 volume 100 mM NHS-ATTO (ATTO Tec), or NHS-Biotin (Pierce) for 10 min at 37°C. The labeling reaction was stopped using 2 volumes of 2X BRB80, containing 100 mM potassium glutamate and 40% v/v glycerol, and then microtubules were sedimented onto cushions of BRB80 supplemented with 60% glycerol. Microtubules were resuspended in cold BRB80. Microtubules were then depolymerized and a second cycle of polymerization and depolymerization was performed before use.

Cover-glass micropatterning

The micropatterning technique was adapted from Portran et al.41. Cover glasses were cleaned by successive chemical treatments: 30 min in acetone, 15 min in ethanol (96%), rinsing in ultrapure water, 2 h in Hellmanex III (2% in water, Hellmanex), and rinsing in ultrapure water. Cover glasses were dried using nitrogen gas flow and incubated for three days in a solution of tri-ethoxy-silane-PEG (30 kDa, PSB-2014, creative PEG works) 1 mg/ml in ethanol 96% and 0.02% of HCl, with gentle agitation at room temperature. Cover glasses were then successively washed in ethanol and ultrapure water, dried with nitrogen gas, and stored at 4°C. Passivated cover glasses were placed into contact with a photomask (Toppan) with a custom-made vacuum-compatible holder and exposed to deep UV (7 mW/cm2 at 184 nm, Jelight) for 2 min 30 s. Deep UV exposure through the transparent micropatterns on the photomask created oxidized micropatterned regions on the PEG-coated cover glasses.

Microfluidic circuit fabrication and flow control

The microfluidic device was fabricated in PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning) using standard photolithography and soft lithography. The master mold was fabricated by patterning 50-μm thick negative photoresist (SU8 2100, Microchem, MA) by photolithography42. A positive replica was fabricated by replica molding PDMS against the master. Prior to molding, the master mold was silanized (trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl)silane, Sigma) for easier lift-off. Four inlet and outlet ports were made in the PDMS device using 0.5 mm soft substrate punches (UniCore 0.5, Ted Pella, Redding, CA). Connectors to support the tubing were made out of PDMS cubes (0.5 cm side length) with a 1.2 mm diameter through hole. The connectors were bonded to the chip ports using still liquid PDMS as glue, which was used to coat the interface between the chip and the connectors, and was then rapidly cured on a hotplate at 120°C. Teflon tubing (Tefzel, inner diameter: 0.03'', outer diameter: 1/16'', Upchurch Scientific) was inserted into the two ports serving as outlets. Tubing with 0.01'' inner and 1/16'' outer diameter was used to connect the inlets via two three-way valves (Omnifit labware, Cambridge, UK) that could be opened and closed by hand to a computer-controlled microfluidic pump (MFCS-4C, Fluigent, Villejuif, France). Flow inside the chip was controlled using the MFCS-Flex control software (Fluigent). Custom rubber pieces that fit onto the tubing were used to close the open ends of the outlet tubing when needed.

Microtubule growth on micropatterns using standard (BRB80) buffer

Microtubule seeds were prepared at 10 μM tubulin concentration (30% ATTO-488-labeled or ATTO-565-labeled tubulin and 70% biotinylated tubulin) in BRB80 supplemented with 0.5 mM GMPCPP at 37°C for 1 h. The seeds were incubated with 1 μM Taxotere (Sigma) at room temperature for 30 min and were then sedimented by high centrifugation at 30°C and resuspended in BRB80 supplemented with 0.5 mM GMPCPP and 1 μM Taxotere. Seeds were stored in liquid nitrogen and quickly warmed to 37°C before use.

The PDMS chip was placed on a micropatterned cover glass and fixed on the microscope stage. The chip was perfused with neutravidin (25 μg/ml in BRB80; Pierce), then washed with BRB80, passivated for 20 s with PLL-g-PEG (Pll 20K-G35-PEG2K, Jenkam Technology) at 0.1 mg/ml in 10 mM Na-Hepes (pH = 7.4), and washed again with BRB80. Microtubule seeds were flowed into the chamber at high flow rates perpendicularly to the micropatterned lines to ensure proper orientation of the seeds. Non-attached seeds were washed out immediately using BRB80 supplemented with 1% BSA. Seed grafting on PEGylated micropatterned surfaces prevents microtubule displacement while switching the medium and minimizes shaft interaction with the substrate10,41. Seeds were elongated with a mix containing 14, 20 or 26 μM of tubulin (20% labeled) in BRB80 supplemented with 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaPi, 1 mM GTP, an oxygen scavenger cocktail (20 mM DTT, 1.2 mg/ml glucose, 8 μg/ml catalase and 40 μg/ml glucose oxidase), 0.1% BSA and 0.025% methyl cellulose (1500 cp, Sigma) at 37°C. GMPCPP caps were grown by supplementing the before-mentioned buffer for with 0.5 mM GMPCPP (Jena Bioscience) and using 10 μM tubulin (100% labeled with a red fluorophore) at 37°C. Capping extends the microtubule lifetime and allows for the investigation of lattice turnover over a period of several minutes despite the dynamic instability in vitro. For fracture experiments, this buffer was then replaced by a buffer containing the same supplements, but without free tubulin and GTP (“washing buffer”). For incorporation experiments, the same buffer as for seed elongation was used, supplemented by 7 μM, 14 μM, 20 μM or 26 μM tubulin (100% labeled, green fluorescent, labeling ratio of about 2 fluorophores per dimer). Microtubules were incubated in this buffer for 15 min or 30 min at 37°C before replacing it with washing buffer for imaging.

GMPCPP microtubule growth in solution and incorporation of free tubulin on micropatterns

Seeds were elongated with a mix containing 2.5 μM of tubulin (20% labeled) in BRB80 supplemented with 0.5 mM GMPCPP for 10 min at 37°C. Step wisely, 1.5 μM tubulin (20% labeled) were added in the mix every 10 min. The final tubulin concentration was 10 μM. Microtubules were incubated 1 hour at 37 °C. A PDMS chip was placed on a micropatterned cover glass and fixed on the microscope stage. The chip was perfused with neutravidin (25 μg/ml in BRB80; Pierce), then washed with HKEM (10mM Hepes pH7.2; 5mM MgCl2; 1mM EGTA; 50mM KCl), passivated for 1min with PLL-g-PEG (Pll 20K-G35-PEG2K, Jenkam Technology) at 0.1 mg/ml in 10 mM Na-Hepes (pH = 7.4), and washed again with HKEM supplemented with 1% BSA. Microtubules were flown into the chamber perpendicularly to the micropatterned lines. Non-attached microtubules were washed out immediately using HKEM supplemented with 1% BSA. For incorporation experiments, GMPCPP-microtubules were incubated with 14 μM Tubulin (100% labeled, green fluorescent, labeling ratio of about 2 fluorophores per dimer) in Tic Tac (16mM Pipes pH 6.9; 10 mM Hepes; 5 mM MgCl2; 1 mM EGTA; 50 mM KCl) supplemented with an oxygen scavenger cocktail (20 mM DTT, 1.2 mg/ml glucose, 8 μg/ml catalase and 40 μg/ml glucose oxidase), 0.1% BSA, 0.025% methyl cellulose (1500 cp, Sigma) and 1 mM GTP. Microtubules were incubated in this buffer for 15 or 30 min at 37 °C before replacing it with washing buffer for imaging.

Imaging

Microtubules were visualized using an objective-based azimuthal ilas2 TIRF microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti, modified by Roper Scientific) and an Evolve 512 camera (Photometrics). The microscope stage was kept at 37°C using a warm stage controller (LINKAM MC60). Excitation was achieved using 491 and 561 nm lasers (Optical Insights). Time-lapse recording was performed using Metamorph software (version 7.7.5, Universal Imaging). Movies were processed to improve the signal/noise ratio (smooth and subtract background functions of ImageJ, version 1.47n5). To visualize incorporation, images were typically taken every 150 ms and 30 images were overlain and averaged. Sites of incorporated tubulin were identified using line scans of the green-fluorescence intensity along the microtubule (Fig. 1b) and corresponded to zones of fluorescence intensity that were at least 2.5-fold higher than the background fluorescence. For fracture experiments, images were taken every 10 s. Visualization of fluctuating microtubules allowed for a clear distinction between fluorescence emanating from the microtubule and from the background.

Cryo-electron microscopy and tomography

Analysis of lattice-defect frequency as a function of tubulin concentration was performed on microtubules assembled from phosphocellulose-purified calf-brain tubulin nucleated by centrosomes isolated from KE-37 human lymphoid cells35,43. Briefly, centrosomes (final concentration 1 x 108 centrosomes per ml) were mixed with tubulin at the desired concentration (6.5 μM, 13.5 μM and 19 μM). Samples were incubated directly on the EM grid under controlled humidity and temperature conditions20 for short assembly times (2 to 5 min), or incubated in a test tube for longer times. Grids were blotted with a filter paper to form a thin film of suspension, and quickly plunged into liquid ethane. Microtubules were visualized with an EM 400 electron microscope (Philips) operating at 80 kV. Images were taken at ~1.5 μm underfocus on negatives (SO-163, Kodak). Sites of transition of protofilament and/or helix-start numbers were determined on printed views of the negatives (see Ref. [19] for details). The field of view in cryo-electron microscopy is much smaller than in light microscopy. Therefore it was impossible to concatenate all microtubules and measure distances between defects. Instead we calculated mean distances between defects (and spatial frequencies) and standard deviations from the total length of analyzed microtubules and the number of observable lattice defects from different samples. For each negative, the total length of the non-13_3 microtubule segments was measured. Since the vast majority of the microtubules were 13_3, their percentage was estimated by counting all 13_3 and non-13_13 microtubules. The total length of 13_3 microtubules was then extrapolated from these measurements. The average defect frequency was calculated by dividing the number of defects by the total microtubule length. Mean values (±sd) provided for each tubulin concentration represent the weighted average of 4, 5 and 2 sample grids for the 6.5 μM, 13 μM and 19.5 μM tubulin concentration conditions, respectively, as explained in Statistical Methods. The high density of microtubule asters at 19 μM tubulin concentration allowed us to analyze specimens prepared at short assembly times (2 and 3 min), compared to the other assembly conditions (up to 30 min of assembly). Microtubule growth rates at these tubulin concentrations are taken from Chrétien et al.35 (see Table III therein).

Cryo-electron tomography was performed on microtubules self-assembled from phosphocellulose-purified porcine brain tubulin44. Ten nanometer gold nanoparticles coated with BSA (Aurion) were added to the suspension to serve as fiducial markers36. Specimens in 4 μl aliquots were pipetted at specific assembly times and vitrified as described above. Specimen grids were observed with a Tecnai G2 T20 Sphera (FEI) operating at 200 kV. Tilt series, typically in the angular range ±60°, were acquired in low electron-dose conditions using a 2k x 2k CCD camera (USC1000, Gatan). Three-dimensional reconstructions were performed using the eTomo graphical user interface of the IMOD software package45 and UCSF Chimera46.

Statistical Methods

The incorporation patterns of microtubules observed by TIRF microscopy were analysed by concatenating all microtubules in a random order together and by measuring the distance between two adjacent incorporation spots (center-to-center distance). As the data represent approximately a lognormal distribution, we calculated the geometric mean and standard deviation (sd) factor of the measured distances, since they better represent the central tendency than the arithmetic mean, as proposed by Kirkwood28. The range between the lower bound (the geometric mean divided by the geometric sd factor) and the upper bound (the geometric mean multiplied by the geometric sd factor) contains about two thirds of the data points, assuming that they follow a lognormal distribution. To test the significance between mean values obtained by the above described method we used the Mann-Whitney test (two-tailed) as a non-parametric alternative to a t-test, given that the distribution is non-Gaussian. The cryo-electron microscopy data were analyzed by calculating then mean distance <d>k between transitions for each sample k (i.e. each time point, see Supplementary Information) using <d>k=Lk/Nk, where Nk and Lk denote the total number of transitions and the total length of the microtubules in the sample. From these values we calculated weighted averages <d>=Σk<d>kNk/ΣkNk and estimates for the standard deviations σ2≈Σk(<d>k-<d>)2Nk/ΣkNk. The thus determined statistical values were analyzed using a two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction for unequal standard deviations. The data are represented as mean ± sd.

Monte-Carlo Simulations

Kinetic Monte-Carlo simulations were performed using a rejection-free random-selection method47.

Lattice Structure

We used the same lattice structure (Fig. 2a) as previously introduced by others16,31. Briefly, the microtubule is modeled on the scale of the tubulin dimer as the canonical 13_3 (13 protofilament, 3 start left-handed helix) structure. In addition, we postulate the existence of a less stable 12_3 (12 protofilament, 3 start helix) lattice structure30,48. The 13_3 lattice and the 12_3 lattice are connected via dislocation defects, where a single protofilament is lost or added (see Fig. 2c). All lattice structures are modeled as square lattices, i.e. each dimer has two longitudinal and two lateral neighbors. Individual lattice sites on the square lattice are identified by a doublet of integers (i,j). The lattice is periodic in a direction perpendicular to the long axis of the microtubule with an offset of 3/2 lattice sites to reproduce the seam structure. Therefore lattice sites at the seam have 2 nearest “half” neighbors across the seam, i.e. dimers at the left seam in Fig. 2a with the doublet (1,j) are in contact with dimers (13,j+2) and (13,j+1) and dimers at the right seam with doublet (13,j) are in contact with dimers (1,j-1) and(1,j-2) for a 13 protofilament lattice. At a dislocation defect a lattice site has only one longitudinal neighbor site.

Lattice transitions and rate constants

Lattice sites can be either empty or occupied by GTP-bound (T) or GDP-bound (D) dimers. Dimers interact with other dimers on nearest neighbor lattice sites via attractive interactions, characterized by bond energies ΔG1 and ΔG2 for longitudinal and lateral bonds, respectively. We assume that longitudinal and lateral bonds of T-T contacts are further stabilized by the energy, ΔGT1 and ΔGT2, respectively, following the allosteric model proposed by Alushin et al.49 Note, that the stabilization of longitudinal T-T contacts is a major difference to the model by vanBuren et al.16, but permits to capture the dynamic instability without further assumptions. The stabilization of only lateral T-T contacts is not sufficient to induce a dynamic instability with sufficiently long phases of growth and shrinkage. To limit the number of free parameters we fix the lattice anisotropy in the binding energies as ΔG1/ΔG2 =ΔGT1/ΔGT2=2, i.e. longitudinal contacts are twice as stable as lateral contacts. This property is also reflected in the stabilizing effects of T-T contacts.

Typically different lattice conformations correspond to different lattice energies33. We include this property by assuming a small destabilizing conformational energy penalty, ΔGC, for dimers in the 12 protofilament lattice compared with the 13 protofilament lattice. Dislocation defects perturb the lattice structure and induce an additional elastic strain in the lattice. In our simple approach we attribute a destabilizing energy, ΔGS, to the dimer located directly at the dislocation defect to mimic the defect strain energy.

For the passive process of polymerization and depolymerization, the principle of detailed balance has to hold. Therefore, on and off rate constants, kon and koff (see Fig. 2a), must be coupled by the relation50

| (1) |

where c0 denotes the standard concentration of free tubulin in solution, i.e. 1 M by convention, and ΔG denotes the change in free energy upon transferring a free dimer from the solution into the lattice. Note, that c0 in (1) is not the actual concentration of the free tubulin in solution, but the standard concentration and originates from the concentration dependence of the chemical potential, i.e. kBT In where c denotes the actual concentration of free tubulin in solution. ΔG = ΔGB + ΔGE +… contains contributions from binding of the dimer to nearest neighbors ΔGB, the loss of entropy due to immobilization of the free dimer in the lattice ΔGE, and further contributions related to the conformation of the lattice, ΔGC, and the presence of defects ΔGS. For practical reasons, we rewrite equation (1) into

| (2) |

with and where ΔG* contains now only binding, conformational and defect strain contributions. We assume that Eq. (2) also governs the depolymerization of GDP-dimers. The difference between the off-rates for GDP-bound and GTP-bound dimers arises from the difference in the binding energy ΔGB.

GTP dimers are irreversibly hydrolyzed into GDP dimers by the rate constant khy if their hydrolysable β subunit is in contact with the α subunit of another dimer, i.e. if the top-next longitudinal lattice site in Fig. 2a in the direction of the microtubule (+)-end is occupied. Hence our modeling permits the following transitions: free GTP dimers can polymerize into a lattice structure, bound GTP dimers can depolymerize from the lattice or hydrolyze into GDP dimers; and bound GDP dimers can depolymerize from the lattice.

At dislocation defects, the lattice can breathe (i.e. open with rate constant kbr to create an empty lattice site and close with rate constant kcl to annihilate an empty lattice site) as depicted in Fig. 2c. Because breathing is a reversible process kbr and kcl are related by

| (3) |

ΔGBR denotes the difference in lattice free energy between the closed and open lattice state. It contains contributions from the conformational energy penalty for a 12 protofilament lattice, ΔGC, which accelerates opening because a less favorable 12 protofilament lattice is receding in favor of a more stable 13 protofilament lattice, contributions from the lateral binding energy of the lateral bond which will be opened, ΔG2 or ΔG2+ΔGT2, and the release in defect strain energy, ΔGS. ΔGBR depends on the occupation of the lattice sites in proximity to the defect.

Monte-Carlo simulations were performed using a custom-written C code. Unless stated otherwise, we used the parameters listed in Supplementary Table S1 for the simulations shown in Fig. 2 and in Supplementary Figs. S2 and S4 and the parameters listed in Supplementary Table S2 for the simulations shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. The microtubule lattice was visualized using the Jmol software package51.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the French National Agency for Research (ANR-16-CE11-0017-01 to DC, ANR-12-BSV5-0004-01 to MT, ANR-14-CE09-0014-02 to LB and ANR-18-CE13-0001 to KJ, MT, and DC) the Human Frontier in Science Program (RGY0088 to MT) and the European Research Council (Starting Grant 310472 to MT).

Footnotes

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request, see author contributions for specific data sets.

Code availability

The source code of the kinetic Monte Carlo model along with detailed instructions to reproduce the data for this manuscript is available online (https://sourceforge.net/projects/microtubulelatticemodel). The codes for the analysis of the model simulations are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Author Contributions

LS and ST performed all dimer exchange and fracture experiments with the help of JG and AA. LS, LB and MT designed these experiments. DC designed and performed cryo-electron microscopy experiments. KJ designed and performed numerical simulations. LS, ST, CA, LB, MT and KJ analyzed data. LS, MT, DC and KJ wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Carlier M-F. Guanosine-5’-triphosphate hydrolysis and tubulin polymerization. Mol Cell Biochem. 1982;47:97–113. doi: 10.1007/BF00234410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchison T, Kirschner MW. Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature. 1984;312:237–42. doi: 10.1038/312237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker RA, O'Brien ET, Pryer NK, Soboeiro MF, Voter WA, Erickson HP, Salmon ED. Dynamic instability of individual microtubules analyzed by video light microscopy: rate constants and transition frequencies. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1437–1448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard J, Hyman AA. Dynamics and mechanics of microtubule plus end. Nature. 2003;422:753–758. doi: 10.1038/nature01600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duellberg C, Cade NI, Holmes D, Surrey T. The size of the EB cap determines instantaneous microtubule stability. Elife. 2016;5:1–23. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aher A, Akhmanova A. Tipping microtubule dynamics, one protofilament at a time. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2018;50:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akhmanova A, Steinmetz MO. Control of microtubule organization and dynamics: two ends in the limelight. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:711–726. doi: 10.1038/nrm4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gasic I, Mitchison TJ. Autoregulation and repair in microtubule homeostatis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2019;56:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dye RB, Flicker PF, Lien DY, Williams RC. End-stabilized microtubules observed in vitro: stability, subunit, interchange, and breakage. Cell Motil Cytoskel. 1992;21:171–86. doi: 10.1002/cm.970210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaedel L, John K, Gaillard J, Nachury MV, Blanchoin L, Théry M. Microtubules self-repair in response to mechanical stress. Nat Mater. 2015;14:1156–1163. doi: 10.1038/nmat4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reid TA, Coombes C, Gardner MK. Manipulation and Quantification of Microtubule Lattice Integrity. Biology Open. 2017;6:1245–1256. doi: 10.1242/bio.025320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimitrov A, Quesnoit M, Moutel S, Cantaloube I, Poüs C, Perez F. Detection of GTP-tubulin conformation in vivo reveals a role for GTP remnants in microtubule rescue. Science. 2008;322:1353–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.1165401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Forges H, Pilon A, Cantaloube I, Pallandre A, Haghiri-Gosnet A-M, Perez F, Poüs C. Localized Mechanical Stress Promotes Microtubule Rescue. Curr Biol. 2016;26:3399–3406. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aumeier C, Schaedel L, Gaillard J, John K, Blanchoin L, Théry M. Self-repair promotes microtubule rescue. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:1054–1064. doi: 10.1038/ncb3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vemu A, Szczesna E, Zehr EA, Spector JO, Grigorieff N, Deaconescu AM, Roll-Mecak A. Severing enzymes amplify mirotubule arrays through lattice GTP-tubulin incorporation. Science. 2018;361:eaau1504. doi: 10.1126/science.aau1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.VanBuren V, Odde DJ, Cassimeris L. Estimations of lateral and longitudindal bond energies within the microtubule lattice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6035–6040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092504999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.VanBuren V, Cassimeris L, Odde DJ. Mechanochemical model of microtubule structure and self-assembly kinetics. Biophys J. 2005;89:2911–2926. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.060913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sept D, Baker NA, McCammon JA. The physical basis of microtubule structure and stability. Prot Sci. 2003;12:2257–2261. doi: 10.1110/ps.03187503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chrétien D, Fuller SD. Microtubules switch occasionally into unfavorable configurations during elongation. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:663–76. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chrétien D, Metoz F, Verde F, Karsenti E, Wade RH. Lattice defects in microtubules: protofilament numbers vary within individual microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:1031–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.5.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atherton J, Stouffer M, Francis F, Moores CA. Microtubule architecture in vitro and in cells revealed by cryo-electron tomography. Acta Cryst D. 2018;74:1–13. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318001948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vitre B, Coquelle FM, Heichette C, Garnier C, Chrétien D, Arnal I. EB1 regulates microtubule dynamics and tubulin sheet closure in vitro. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:415–21. doi: 10.1038/ncb1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doodhi H, Prota AE, Rodríguez-García R, Xiao H, Custar DW, Bargsten K, Katrukha EA, Hilbert M, Hua S, Jiang K, Grigoriev I, et al. Termination of Protofilament Elongation by Eribulin Induces Lattice Defects that Promote Microtubule Catastrophes. Curr Biol. 2016;26:1713–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaap IT, de Pablo PJ, Schmidt CF. Resolving the molecular structure of microtubules under physiological conditions with scanning force microscopy. Eur Biophys J. 2004;33:462–7. doi: 10.1007/s00249-003-0386-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisenberg RC. Microtubule Formation in vitro in Solutions Containing Low Calcium Concentrations. Source Sci New Ser. 1972:1104–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4054.1104. 177174254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kellogg EH, Hejab NMA, Howes S, Northcote P, Miller JH, Díaz JF, Downing KH, Nogales E. Insights into the Distinct Mechanisms of Action of Taxane and Non-Taxane Microtubule Stabilizers from Cryo-EM Structures. J Mol Biol. 2017;429:633–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yajima H, Ogura T, Nitta R, Okada Y, Sato C, Hirokawa N. Conformational changes in tubulin in GMPCPP and GDP-taxol microtubules observed by cryoelectron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:315–322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201201161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirkwood TBL. Geometric means and measures of dispersion. Biometrics. 1979;35:908–909. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandelkow E-M, Schultheiss R, Rapp R, Müller M, Mandelkow E. On the surface lattice of microtubules: helix starts, protofilament number, seam, and handedness. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1067–1073. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.3.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chrétien D, Wade RH. New data on the microtubule surface lattice. Biol Cell. 1991;71:161–174. doi: 10.1016/0248-4900(91)90062-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardner MK, Charlebois BD, Jánosi IM, Howard J, Hunt AJ, Odde DJ. Rapid microtubule self-assembly kinetics. Cell. 2011;146:582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Z, Wang H-W, Mu W, Ouyang Z, Nogales E, Xing J. Simulations of tubulin sheet polymers as possible structural intermediates in microtubule assembly. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(10):e7291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunyadi V, Chrétien D, Jánosi IM. Mechanical stress induced mechanism of microtubule catastrophes. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:927–938. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janson ME, Dogterom M. A bending mode analysis for growing microtubules: evidence for a velocity-dependend rigidity. Biophys J. 2004;87:2723–2736. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.038877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chrétien D, Fuller SD, Karsenti E. Structure of growing microtubule ends: two-dimensional sheets close into tubes at variable rates. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1311–1328. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.5.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coquelle F, Blestel S, Heichette C, Arnal I, Kervrann C, Chrétien D. Cryo-electron tomography of microtubules assembled in vitro from purified components. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2011;777:193–208. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-252-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyman AA, Chrétien D, Arnal I, Wade R. Structural Changes Accompanying GTP Hydrolysis in Microtubules: Information from a Slowly Hydrolyzable Anlalogue Guanylyl-(α,β)-Methylene-Diphosphonate. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:117–125. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shelanski ML. Chemistry of the filaments and tubules of brain. J Histochem Cytochem. 1973;21:529–539. doi: 10.1177/21.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malekzadeh-Hemmat K, Gendry P, Launey JF. Rat pankreas kinesin: Identification and potential binding to microtubules. Cell Mol Biol. 1993;39:279–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyman A, Drechsel D, Kellogg D, Salser S, Sawin K, Steffen P, Wordeman L, Mitchison T. Preparation of modified tubulins. Methods Enzymol. 1991;196:478–485. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)96041-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Portran D, Gaillard J, Vantard M, Théry M. Quantification of MAP and molecular motor activities on geometrically controlled microtubule networks. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2013;70:12–23. doi: 10.1002/cm.21081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duffy DC, McDonald JC, Schueller OJ, Whitesides GM. Rapid prototyping of microfluidic systems in poly(dimethylsiloxane) Anal Chem. 1998;70:4974–4984. doi: 10.1021/ac980656z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chrétien D, Buendia B, Fuller SD, Karsenti E. Reconstruction of the centrosome cycle from cryoelectron micrographs. J Struct Biol. 1997;120:117–133. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weis F, Moullintraffort L, Heichette C, Chrétien D, Garnier C. The 90-kDa heat shock protein HSP90 protects tubulin against thermal denaturation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:952–534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mastronarde DN. Dual-axis tomography: an approach with alignment methods that preserve resolution. J Struct Biol. 1997;120:343–352. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. CSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–12. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lukkien JJ, Segers JPL, Hilbers PAJ, Gelten RJ, Jansen APJ. Efficient Monte Carlo methods for the simulation of catalytic surface reactions. Phys Rev E. 1998;58:2598–2610. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.58.2598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sui H, Downing KH. Structural basis of interprotofilament interaction and lateral deformation of microtubules. Structure. 2010;18:1022–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alushin GM, Lander GC, Kellogg EH, Zhang R, Baker D, Nogales E. High-resolution microtubule structures reveal the structural transitions in αβ-tubulin upon GTP hydrolysis. Cell. 2014;157:1117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Groot SR, Mazur P. Non-equilibrium thermodynamics. Dover Publications Inc; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 51.http://www.jmol.org.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.