Abstract

We performed a network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomised studies in adult peritoneal dialysis patients to evaluate the effects of specific renin-angiotensin aldosterone systems (RAAS) blockade classes on residual kidney function and peritoneal membrane function. Key outcome parameters included the following: residual glomerular filtration rate (rGFR), urine volume, anuria, dialysate-to-plasma creatinine ratio (D/P Cr), and acceptability of treatment. Indirect treatment effects were compared using random-effects model. Pooled standardised mean differences (SMDs) and odd ratios (ORs) were estimated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We identified 10 RCTs (n = 484) and 10 non-randomised studies (n = 3,305). Regarding changes in rGFR, RAAS blockade with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) were more efficacious than active control (SMD 0.55 [0.06–1.04] and 0.62 [0.19–1.04], respectively) with the protective effect on rGFR observed only after usage ≥12 months, and no differences among ACEIs and ARBs. Compared with active control, only ACEIs showed a significantly decreased risk of anuria (OR 0.62 [0.41–0.95]). No difference among treatments for urine volume and acceptability of treatment were observed, whereas evidence for D/P Cr is inconclusive. The small number of randomised studies and differences in outcome definitions used may limit the quality of the evidence.

Subject terms: Nephrology, Peritoneal dialysis

Introduction

Despite improvement in the treatments and techniques for peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients, long-term PD leads to the decline of residual kidney function (RKF) and peritoneal membrane function (PMF), as a result of membrane or ultrafiltration (UF) failure1,2. Existing epidemiological studies have illustrated that RKF deteriorations over time in PD patients compromising patient survival as well as overall health-related quality of life (HRQOL)3–5. The CANUSA (Canada-United States Peritoneal Dialysis) study, the landmark multicenter prospective cohort of incident PD patients, showed 12% and 36% reductions in the risk of death for each 5 L/week/1.73 m2 increment in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and each 250 mL increase in urine volume, respectively3. Likewise, the risk of UF failure has increased 3–5% in the first year and 30–50% after three years of PD6–8. There is increasing evidence on the inter-relationship between the RKF and PMF9. Alterations in RKF and peritoneal characteristics over time are important determinants of patients’ technique survival and mortality9,10. Subsequently, treatment strategies for maintaining RKF in conjunction with PMF are crucial.

Blockade of the renin-angiotensin aldosterone systems (RAAS) with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) in PD patients are likely to preserve residual glomerular filtration rate (rGFR) along with residual urine volume until the PD patients reach anuria that may improve survival in these population11–15. Several studies revealed that blockade of RAAS positively effects the peritoneal membrane by reducing morphologic changes and preserving peritoneal membrane integrity16–18. Therefore, inhibitions of RAAS could potentially improve technique survival and allow patients to be sustained on PD programs for longer periods.

However, the role of RAAS blockade in PD patients has not been fully elucidated. Some studies have revealed the protective properties11–15,19, whereas others have not20–26. Previous systematic reviews have shown that ACEIs/ARBs substantially benefit in preserving rGFR in PD patients, while a lack of evidence exist regarding the relative efficacy of MRAs and direct renin inhibitors (DRIs)27–29. Moreover, existing pairwise meta-analyses have focused mainly on RKF rather than other clinically relevant and related outcomes such as PMF and adverse events27–29. Recently, treatment with an ACEIs or ARBs has been recommended by the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD)30 for PD patients with significant RKF, although the comparative effectiveness of specific RAAS blockade classes remains unknown.

To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis (NMA) of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomised studies in PD patients to evaluate the effects of specific RAAS blockade classes on RKF and PMF as determined by five key parameters: rGFR, urine volume, incidence of anuria, dialysate-to-plasma creatinine ratio (D/P Cr), and acceptability of treatment.

Results

Search strategy and characteristics of included studies

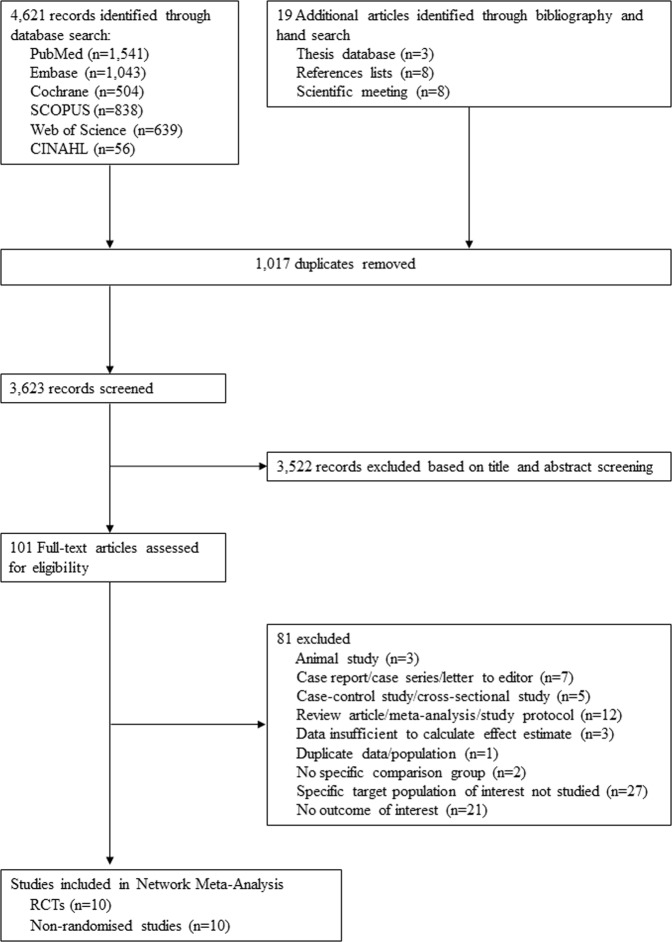

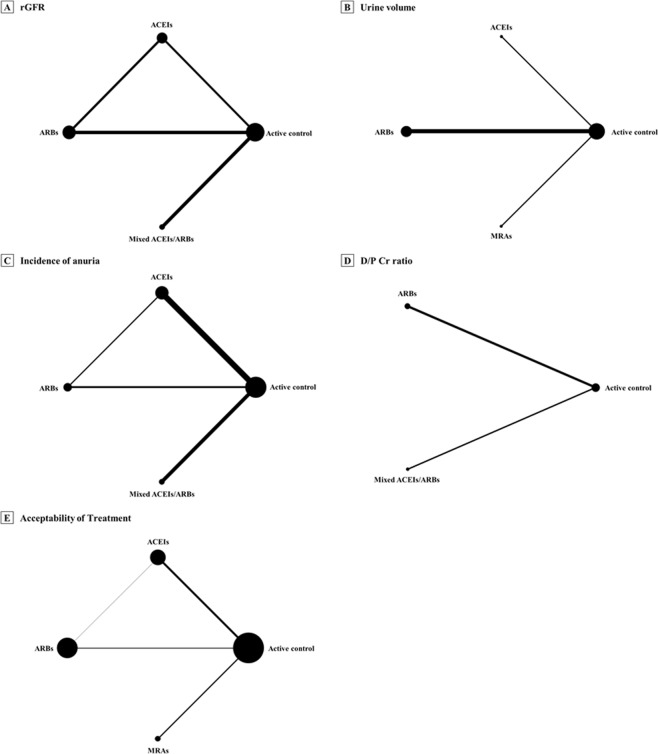

The systematic search details are described in Fig. 1. After screening of titles/abstracts, 101 full-text articles of potentially relevant studies were acquired. After appraising these articles against study inclusion/exclusion criteria (Supplementary, Table S1), we included 10 RCTs12–14,25,31–36 and 10 non-randomised studies11,20–24,26,37–39 that compared RAAS blockade classes with active control (Table 1). Four RAAS blockade classes were compared with active control—ACEIs, ARBs MRAs, and mixed ACEIs/ARBs, however, no data for DRIs in any outcome of interest. Two studies provided direct comparisons of ACEIs and ARBs31,36. Network diagrams presenting the available evidence for primary and secondary outcomes are illustrated in Figs. 2 and S1. Detailed methods of measurement and definition of outcomes are described in Supplementary Table S2. A total of 3,789 PD participants were enrolled in the set of included studies; the majority of these patients received continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). The baseline mean age and rGFR ranged from 40.2–66.8 years and 0.6–8.4 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. The follow-up periods ranged from 7 days to 66.3 months, and 12 (60%) studies encompassed participants from Asia. The study- and participant-characteristics are illustrated in Table 1 and Supplementary, Table S3.

Figure 1.

Selection of studies. Abbreviations: RCTs, randomised-controlled trials.

Table 1.

Description of included studies: RCTs and non-randomised studies.

| Author, Year | Design | Country Enrollment | Sample Size | Intervention | Control | Mean Age ± SD, Year | Female, N (%) | Mean rGFR ± SD, mL/min | Mean Urine Volume ± SD, mL/day | PD Modality | Follow-Up Period, Mean ± SD | Risk of Biasa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favazza et al., 199232 | RCT: open label, crossover study | Italy | 9 | Enalapril (40 mg/day) | Nifedipine (60 mg/day), Clonidine (0.45 mg/day) | 64.0 ± 5.4 | 3 (33.3) | 3.9 ± 0.8 | NR | CAPD | 14 days | 1/8 |

| Moist et al., 200011 | Non-randomised studies: prospective cohort study | USA | 1,032 | ACEI user | Non-ACEI users | 55.5 ± 14.6 | 490 (47.5) | 7.5 ± 2.7b | NR | CAPD, APD | 11.9 ± 1.7 months | 7/9 |

| Johnson et al., 200337 | Non-randomised studies: prospective cohort study | Australia | 146 | ACEI users | Non-ACEI users | 54.8 ± 16.3 | 83 (56.8) | 4.9 ± 2.3b | NR | CAPD, APD | 20.5 ± 14.8 months | 7/9 |

| Li et al., 200312 | RCT: open-label, parallel study | Hong Kong | 60 | Ramipril (5 mg/day) | Active controlc | 58.6 ± 12.1 | 22 (36.7) | 3.6 ± 2.0b | NR | CAPD | 12 months | 3/8 |

| Phakdee-kitcharoen et al., 2004d 31 | RCT: open label, crossover study | Thailand | 21 | Candesartan (8 mg/day) | Enalapril (10 mg/day) | 44.8 ± 10.1 | 7 (33.3) | 2.0 ± 2.4 | NR | CAPD | 1 months | 1/8 |

| Suzuki et al., 200413 | RCT: open-label, parallel study | Japan | 34 | Valsartan (40–80 mg/day) | Active controlc | 63.5 ± 3.5 | 16 (47.0) | 4.3 ± 1.7b | 1045.0 ± 220.6 | CAPD | 24 months | 3/8 |

| Rojas-Campos et al., 200520 | Non-randomised studies: quasi experimental (crossover) study | Mexico | 20 | Losartan (50–200 mg/day) | Prazosin (2–6 mg/day), verapamil (80–240 mg/day) | 42.9 ± 16.6 | 4 (20.0) | NR | NR | CAPD | 7 days | 1/8 |

| Wang et al., 200533 | RCT: open-label, parallel study | China | 32 | Valsartan (40–80 mg/day) | Active controlc | 42.0 ± 11.5 | 12 (35.3) | 4.9 ± 2.2b | 1085 ± 696.3 | CAPD | 28 ± 13 months | 1/8 |

| Furuya et al., 200621 | Non-randomised studies: quasi experimental (crossover) study | Japan | 8 | Candesartan (8 mg/day) | Active controlc | 66.8 ± 8.8 | 4 (50.0) | NR | 1035 ± 383.5 | CAPD, APD | 3 months | 1/8 |

| Jearnsujitwimol et al., 200639 | Non-randomised studies: quasi experimental (crossover) study | Thailand | 7 | Candesartan (8–16 mg/day) | Active controlc | 62.0 ± 3.6 | 2 (28.6) | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 16.9 ± 8.2 | CAPD |

12 weeks for treatment, 6 week for control |

1/8 |

| Zhong et al., 200734 | RCT: open-label, parallel study | China | 44 | Irbesartan (300 mg/day) | Active controlc | 44.0 ± 14.6 | 14 (31.8) | 4.5 ± 2.7b | 1255 ± 425.1 | CAPD | 12 months | 1/8 |

| Wontanatawatot et al., 200935 | RCT: open-label, parallel study | Thailand | 46 | Enalapril (40 mg/day) | Active controlc | 48.1 ± 12.0 | 25 (54.3) | NR | NR | CAPD | 6 months | 1/8 |

| Jing et al., 201022 | Non-randomised studies: retrospective cohort study | China | 66 | ACEI/ARB users | Non-ACEI/ARB users | 52.5 ± 12.2 | 24 (36.4) | 4.6 ± 2.7 | NR | CAPD | 12 months | 6/9 |

| Kolesnyk et al., 201123 | Non-randomised studies: prospective cohort study | Netherland | 452 | ACEI/ARB users | Non-ACEI/ARB users | 50.8 ± 10.6 | 154 (34.1) | 4.9 ± 2.4b | NR | Not specified | 3 years | 8/9 |

| Basturk et al., 201224 | Non-randomised studies: prospective cohort study | Turkey | 43 | ACEI users | Non-ACEI users | 40.2 ± 18.7 | 19 (44.2) | NR | 332 ± 476.3 | CAPD | 6 months | 6/9 |

| Reyes-Marín et al., 201236 | RCT: open-label, parallel study | Mexico | 60 | Enalapril (10 mg/day) | Losartan (50 mg/day) | 45.8 ± 19.0 | 24 (40.0) | 3.9 ± 1.8b | NR | APD | 12 months | 1/8 |

| Ito et al., 2014e 14 | RCT: open-label, parallel study | Japan | 158 | Spironolactone (25 mg/day) | Active controlc | 56.5 ± 13.4 | 45 (28.5) | NR | 1009.2 ± 762.2 | Not specified | 24 months | 3/8 |

| Szeto et al., 201538 | Non-randomised studies: retrospective cohort study | Hong Kong | 645 | ACEI/ARB users | Non-ACEI/ARB users | 57.2 ± 12.7 | 286 (44.3) | 3.7 ± 2.3b | NR | CAPD | 66.3 ± 34.7 months | 7/9 |

| Yongsiri et al., 201525 | RCT: double-blind, crossover study | Thailand | 20 | Spironolactone (25 mg/day) | Placebof | 52.4 ± 12.4 | 12 (60.0) | NR | 895.0 ± 582.0 | CAPD | 1 months | 3/8 |

| Shen et al., 201726 | Non-randomised studies: retrospective cohort study | USA | 886 | ACEI/ARB users | Non-ACEI/ARB users | 65.5 ± 13.6 | 390 (44.0) | 8.4 ± 4.8b | 991.6 ± 648.8 | CAPD, CCPD | 12.0 ± 10.8 months | 8/9 |

aFor RCTs, and quasi-experimental study, the risk of bias was assessed based on the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool and expressed as the number of low risk-risk judgments (ranging 0–8), while the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied for cohort study and summary scores ranging from 0–9 points.

bAdjusted for body surface area.

cTrial did not use a placebo.

dData were based on nonanuric and anuric patients at baseline.

eAll participants in both arm received ACEI or ARB treatment for at least 3 months.

fAntihypertensive agents were allowed except for ACEIs or ARBs treatment.

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; APD, automated peritoneal dialysis; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; CCPD, continuous cyclic peritoneal dialysis; rGFR, residual glomerular filtration rate; NR, not reported; PD, peritoneal dialysis; RCTs, randomised-controlled trials; SD, standard deviation; USA, the United States of America.

Figure 2.

Network plot of eligible comparisons for primary outcomes. Notes: The circles (nodes) represent the available treatments and the lines (edges) represent the available comparisons. Size nodes and width of edges indicate weighting according to the numbers of studies involved for each treatment and comparison, respectively. Abbreviations: ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; D/P Cr, dialysate-to-plasma creatinine; MRAs, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; rGFR, residual glomerular filtration rate.

Risk of bias of included studies

The summary results of the risk of bias assessment are shown in Table 1. Overall, the included studies had low methodological quality and high risk of bias (Supplementary Table S4). Among 10 RCTs and 3 quasi-experimental included studies, the risk of bias was high or unclear for sequence generation (61.5%); allocation concealment (69.2%); blinding of participants (92.3%), blinding of personnel (92.3%), and blinding of outcomes assessors (92.3%); completeness of outcome reporting (53.8%); and selective reporting of outcomes (92.3%). According to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), the summary scores of included 7 cohort studies ranged from 6–8 points, 5 cohort studies were considered to be at high-quality (≥7 points).

Residual kidney function

Findings from pairwise meta-analysis and NMA for RKF outcomes were consistent, except for the effect of ACEIs on change in rGFR (Table 2). The overall results are summarised in Fig. 3; and Supplementary, Tables S5 and S6. For pairwise comparison, heterogeneity was low to moderate (I2 < 75%), however, I2 values higher than 75% was identified for the comparisons of ARBs versus active control on change in urine volume (I2 = 87%). Rankogram and cumulative probability curves of RAAS blockade against active control are provided in Supplementary, Figs. S2 and S3, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of findings versus active control and the strength of evidence from pairwise meta-analysis and NMA.

| Treatment Comparisona | Findings from RCTs | Findings from RCTs and non-randomised studies | Strength of Evidence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Studies Includedb (N) | Pairwise Meta-Analysis | Network Meta-Analysisc | No. of Studies Includedb (N) | Pairwise Meta-Analysis | Network Meta-Analysisd | ||||||

| Effect Estimate (95% CI) | I2 (P-Value) | τ2 | Effect Estimate (95% CI) | Effect Estimate (95% CI) | I2 (P-Value) | τ2 | Effect Estimate (95% CI) | ||||

| Change in rGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | |||||||||||

| ACEIs | 2 (62) |

0.17 (-0.80 to 1.15) |

70% (0.069) | 0.353 |

SMD 0.52 (−0.07 to 1.11) |

2 (62) |

0.17 (−0.80 to 1.15) |

70% (0.069) | 0.353 |

SMD 0.55 (0.06 to 1.04) |

Low |

| ARBs | 3 (104) |

0.82 (0.17 to 1.47) |

59% (0.086) | 0.195 |

SMD 0.62 (0.10 to 1.14) |

3 (104) |

0.82 (0.17 to 1.47) |

59% (0.086) | 0.195 | SMD 0.62 (0.19 to 1.04) | Low |

| Mixed ACEIs/ARBs | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 (711) | 0.41 (0.25 to 0.57) | 0% (0.620) | <0.001 | SMD 0.45 (0.03 to 0.86) | Insufficient |

| Change in Urine Volume, mL/day | |||||||||||

| ACEIs | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 (43) |

SMD 0.20 (−0.45 to 0.86) |

NA | NA |

SMD 0.20 (−2.39 to 2.80) |

Insufficient |

| ARBs | 3 (112) |

SMD 1.38 (−0.07 to 2.82) |

91% (<0.001) | 1.466 |

SMD 1.39 (−0.29 to 3.08) |

4 (120) |

SMD 1.07 (−0.07 to 2.21) |

87% (<0.001) | 1.164 |

SMD 1.08 (−0.25 to 2.41) |

Low |

| MRAs | 1 (20) |

SMD −0.24 (−0.86 to 0.39) |

NA | NA |

SMD −0.24 (−3.11 to 2.63) |

1 (20) |

SMD −0.24 (−0.86 to 0.39) |

NA | NA |

SMD −0.24 (−2.83 to 2.35) |

Insufficient |

| Incidence of Anuria | |||||||||||

| ACEIs | 1 (60) |

OR 0.58 (0.36 to 0.94) |

NA | NA |

OR 0.62 (0.41 to 0.95) |

4 (1,265) |

OR 0.69 (0.57 to 0.83) |

0.0% (0.436) | <0.001 |

OR 0.69 (0.57 to 0.83) |

Low |

| ARBs | 2 (76) |

OR 0.89 (0.45 to 1.73) |

0.0% (0.903) | <0.001 |

OR 0.77 (0.46 to 1.29) |

2 (76) |

OR 0.89 (0.45 to 1.73) |

0.0% (0.724) | <0.001 |

OR 0.81 (0.51 to 1.31) |

Low |

| Mixed ACEIs/ARBs | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 (1,338) |

OR 0.88 (0.75 to 1.03) |

0.0% (0.409) | <0.001 |

OR 0.88 (0.75 to 1.03) |

Insufficient |

| Change in D/P Cr Ratio | |||||||||||

| ARBs | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 (28) |

SMD 0.04 (−0.48 to 0.57) |

0.0% (0.957) | <0.001 |

SMD 0.04 (−0.48 to 0.57) |

Insufficient |

| Mixed ACEIs/ARBs | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 (66) |

SMD −1.60 (−2.16 to −1.04) |

NA | NA |

SMD −1.60 (−2.16 to −1.04) |

Insufficient |

| Acceptability of Treatment | |||||||||||

| ACEIs | 3 (131) |

OR 1.57 (0.52 to 4.71) |

26.4% (0.257) | 0.266 |

OR 1.49 (0.59 to 3.80) |

4 (185) |

OR 0.93 (0.26 to 3.26) |

59.0% (0.062) | 0.897 |

OR 0.93 (0.37 to 2.37) |

Low |

| ARBs | 3 (116) |

OR 1.12 (0.23 to 5.43) |

0.0% (0.831) | <0.001 |

OR 1.21 (0.29 to 5.09) |

6 (151) |

OR 1.08 (0.29 to 3.99) |

0.0% (0.996) | <0.001 |

OR 1.06 (0.29 to 3.84) |

Low |

| MRAs | 2 (178) |

OR 1.46 (0.75 to 2.84) |

0.0% (0.850) | <0.001 |

OR 1.45 (0.59 to 3.57) |

2 (178) |

OR 1.46 (0.75 to 2.84) |

0.0% (0.850) | <0.001 |

OR 1.42 (0.40 to 5.05) |

Low |

aSummary of treatment effects compared with active control.

bNumber of studies with direct comparison.

cThe τ2 values in the network analyses from RCTs were: change in rGFR, 0.153 (moderate heterogeneity); change in urine volume, 2.043 (high heterogeneity); incidence of anuria, < 0.001 (low heterogeneity); change in D/P Cr ratio (NA); acceptability of treatment, 0.104 (moderate heterogeneity).

dThe τ2 values in the network analyses from RCTs and non-randomised studies were: change in rGFR, 0.061 (moderate heterogeneity); change in urine volume, 1.647 (high heterogeneity); incidence of anuria, < 0.001 (low heterogeneity); change in D/P Cr ratio (NA); acceptability of treatment, 0.340 (high heterogeneity).

Abbreviations: ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; CI, confidence interval; D/P Cr, dialysate-to-plasma creatinine; MRAs, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; NA, not applicable; NMA, network meta-analysis; OR, odds ratio; rGFR, residual glomerular filtration rate; RCTs, randomised-controlled trials; SMD, standardised mean difference.

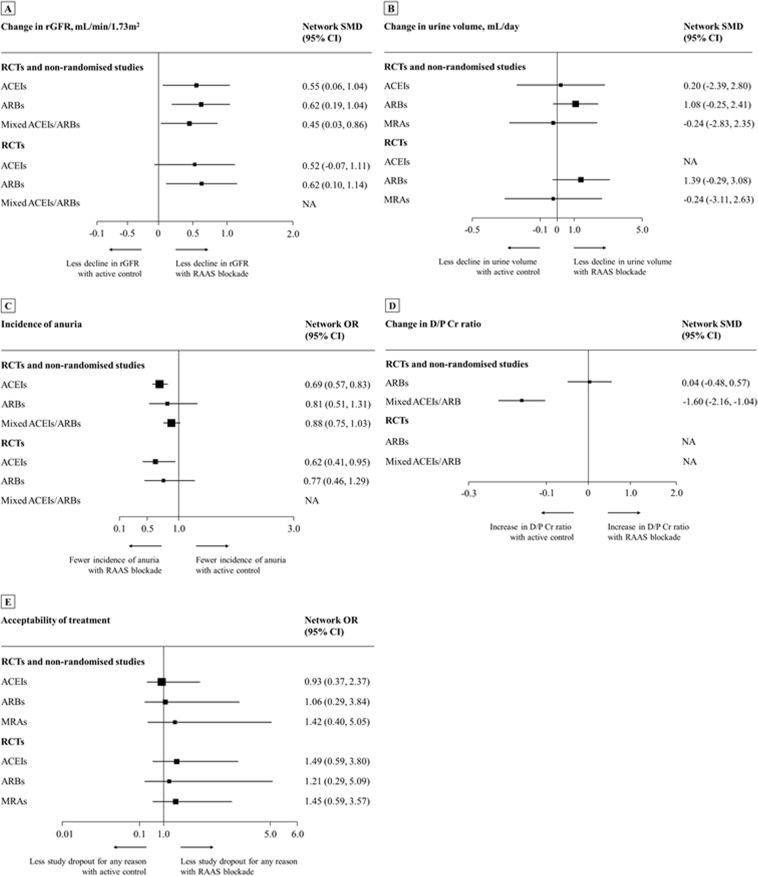

Figure 3.

Network meta-analysis of RAAS blockade compared with active control for primary outcomes. Abbreviations: ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; CI, confidence interval; D/P Cr, dialysate-to-plasma creatinine; MRAs, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; NA, not applicable; OR, odd ratio; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade; RCTs, randomised-controlled trials; rGFR, residual glomerular filtration rate; SMD, standardised mean difference.

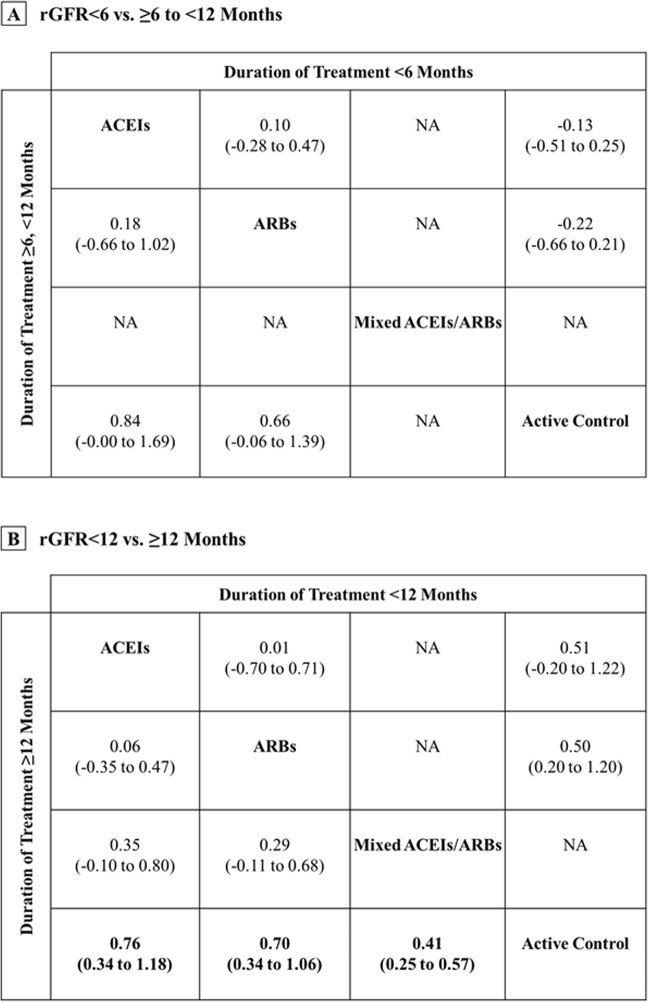

For change in rGFR, ACEIs or ARBs was substantially more efficacious than active control with medium treatment effects (standardised mean difference [SMD] range 0.45 to 0.55; Table 2 and Fig. 3). Interestingly, the NMA resulted that the protective effect of RAAS blockade on preservation of rGFR was found if duration of treatment was ≥12 months (SMD range 0.41 to 0.76; Fig. 4). No significant difference among treatment comparisons for change in urine volume was observed. Moreover, only ACEIs was associated with a significantly decreased risk of anuria compared with active controls. The odd ratios (ORs) from NMA of RCTs alone and RCTs/non-randomised studies together were 0.62 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.41 to 0.95) and 0.69 (95% CI, 0.57 to 0.83), respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

Figure 4.

Mean change in rGFR by duration of treatment: evidence from NMA (RCTs and non-randomised studies). Note: Bold values indicate statistical significance. For study duration <6 or <12 months, SMDs >0 indicate that the treatment specified in the row is more efficacious than that in the column. For study duration ≥6 to <12 or ≥12 months, SMDs >0 indicate that the treatment specified in the column is more efficacious than that in the row column. To obtain SMDs for comparisons in the opposite direction, positive values should be converted into negative values, and vice versa. Abbreviations: ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; CIs, confidence intervals; NMA, network meta-analysis; RCTs, randomised-controlled trials; rGFR, residual glomerular filtration rate; SMDs, standardised mean differences.

Owing to limited data, a dose-response relationship and several preplanned subgroup analyses could not be performed. However, our subgroup analyses showed no effect of RAAS blockade on change in rGFR from baseline among study size ≤ 50 participants or non-Asian countries (Supplementary, Tables S7 and S8). Meanwhile, there was no effect of study size or location on the main findings of change in urine volume and incidence of anuria.

Peritoneal membrane function and ultrafiltration volume

Overall results of PMF and UF volume did not differ among pairwise meta-analyses (Supplementary, Tables S5 and S6) and NMAs (Supplementary, Tables S9 and S10). Nonetheless, effect estimates were mainly drawn from non-randomised studies, and very few data were available. Thus, it was impossible to establish dose- and duration-response effects or subgroup analyses. Compared with active controls, mixed ACEIs/ARBs were associated with a statistically significant decrease in D/P Cr ratio (SMD −1.60; 95% CI [−2.16 to −1.04]; Table 2 and Fig. 3), whereas increase the 4-hour UF by the peritoneal equilibration test (SMD 1.36; 95% CI [0.02 to 2.70]; Supplementary, Table S9).

Acceptability of treatment and safety outcomes

Both pairwise meta-analysis and NMA of primary analysis (Table 2 and Fig. 3; Supplementary, Tables S5 and S6) and subgroup analyses (Supplementary, Tables S7 and S8) did not differ between treatment comparisons. Likewise, no associations with the occurrence of adverse events were found (Supplementary, Tables S9 and S10). Nevertheless, only one study14 revealed that MRAs with spironolactone increased the risk of gynaecomastia (OR 6.40 [1.37–29.92], Supplementary, Table S10), while no study reported safety outcome on angioedema/oedema or HRQOL.

Sensitivity analyses

Post-hoc analysis by adding conference abstracts could not be performed due to lack of additional relevant studies. The results for incidence of anuria, daily UF volume, and acceptability of treatment were robust and did not change substantially in sensitivity analyses (Supplementary, Tables S11–S13).

For change in rGFR, there was no protective effect of treatment comparisons after the analysis was restricted to studies from non-mainland China, as well as when studies with mixed ACEIs/ARBs were removed, except for ARBs which was not different when excluding mixed treatment effects (Supplementary, Table S14). Notably, the positive association between ARBs and change in urine volume was found when restricted analysis by excluding studies from mainland China was performed (SMD 3.19 [2.51–3.87], Supplementary, Table S12). Exclusion of crossover studies did not result in substantial differences for change in D/P Cr ratio and 4-hour UF volume, while removal of these studies resulted in ACEIs being associated with a significantly increased risk of dry cough (Supplementary, Table S13).

Assessment of heterogeneity, inconsistency, transitivity, and publication bias

For NMAs, most outcomes were associated with low to moderate statistically heterogeneity, except for change in urine volume, acceptability of treatment, and dry cough which were associated with high heterogeneity. Network meta-regression analyses could not be performed due to limited data availability. However, univariate meta-regression of pairwise analyses revealed that the heterogeneity of studies was not accounted by any of the study- or baseline participant-level characteristics for change in rGFR, urine volume, incidence of anuria or acceptability of treatment (Supplementary, Table S15).

There was no evidence of inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence based upon findings from the loop-specific and node-splitting methods (Supplementary, Tables S16 and S17), however, inconsistency for change in D/P Cr ratio and 4-hour UF volume were identified by the design-by-treatment interaction approach (Supplementary, Table S18). Analysis of comparison-adjusted funnel plots indicated no evidence of asymmetry, except for change in urine volume (Supplementary, Fig. S4).

Strength of the body of evidence

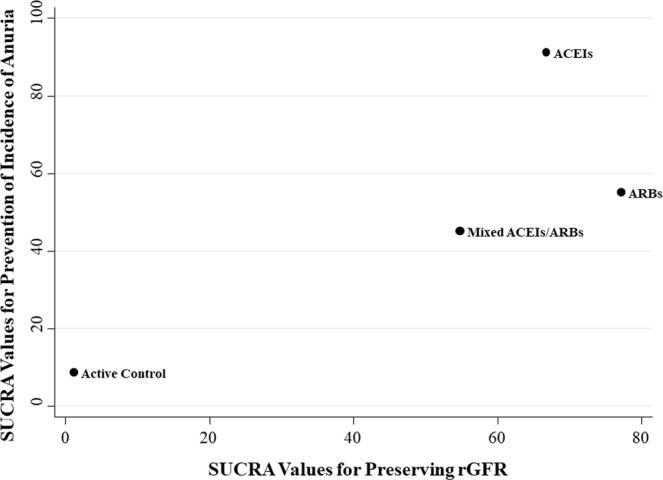

We graded the strength of evidence of ACEIs or ARBs for the preservation of RKF (rGFR and anuria) as low, whereas several outcomes were graded as insufficient due to study limitations, inconsistency, and imprecision of effect estimates (Table 2). We therefore ranked RAAS blockade with regard to rGFR and incidence of anuria as two dimensions (Fig. 5). The comparative effects of RAAS blockade according to the efficacy on preserve RKF and acceptability of treatment are provided in Supplementary, Fig. S5. However, effects of RAAS blockade on PMF could not be established due to limited evidence. Details of evidence synthesis by the Grading of Recommended Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system are described in Supplementary, Table S19.

Figure 5.

Two-dimension rank plot of effect estimates according to efficacy on preservation of rGFR and incidence of anuria. Abbreviations: ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; rGFR, residual glomerular filtration rate; SUCRA, surface under the cumulative ranking curve.

Discussion

Our NMA sheds unified hierarchies of evidence for all RAAS inhibitors, only ACEIs and ARBs treatments were efficacious than active control and ranked as the highest level of efficacy for the prevention of anuria and preservation of rGFR, respectively. Effects of RAAS blockade on PMF were inconclusive likely based on few studies examining PMF and its constituents as an outcome. No specific RAAS blockade classes were superior to other treatments with regard to adverse outcomes. However, it should be noted that our findings are limited by the strength of evidence according to the GRADE system revealed low or insufficient quality evidence.

Compared with existing reviews, our study has important methodological differences. This review incorporated of both RCTs and non-randomised studies to address some limitations of RCT, such as small sample size and short follow-up period, allow assessment of treatment comparisons simultaneously, and generalisable evidence40. A review by Akbari et al.29, demonstrated a protective effect of treatment with ACEIs/ARBs on preservation of rGFR at 12 months (mean difference [MD] 0.91 [0.14–1.68] mL/min/1.73 m2, and in line Zhang et al.28, (MD 1.11 [0.38–1.83] mL/min/1.73 m2 for treatment with ARBs). Given our findings, the superiority of ACEIs or ARBs is similar to the pattern seen in pairwise meta-analyses. Long-term use (≥12 months) of ACEIs and ARBs shown substantial benefit for change in rGFR (SMD 0.76 [0.34–1.18] and 0.70 [0.34–1.06] mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively), and prove more clinically significant benefit compared with treatment <12 months.

From the methodological viewpoint and based on the natural disease progression, the length of follow-up time is important to provide adequate statistical power. Besides a relatively small number of patients, it can be postulated that the short duration of treatment <12 months was ultimately underpowered to observe the intended effects of the RAAS blockade. Additionally, although the mechanisms of action of the RAAS blockade effects have not been clearly described in PD patients, delayed therapeutic effects of the use of RAAS blockade has been apparently illustrated in the certain population such as diabetic nephropathy and those with dietary protein restriction—presumably because of the hemodynamic effect of the inhibition of the RAAS activation41–43. In this circumstance, it may further explain that no significant association of the RAAS blockade on the rGFR was observed when a duration of treatment was <12 months. However, adequate powered controlled trials are warranted to confirm our findings in terms of duration-response effects.

Indeed, the urine volume is variable among the dialysis population, ranging from oliguria to normal or even above normal levels. These results are related to the circumstance that the urine output is influenced not only by the GFR, but also by the difference between the GFR and the rate of tubular transport mechanisms. In the PD population, urine volume accounted for only one half of the variance in GFR (r2 = 0.55, P < 0.001)37. Thereby, we hypothesised that the effect of RAAS blockade on the preserve of urine volume does not always in line with the rGFR. However, it is unclear whether or not the use of RAAS blockade among PD patients may have an additional effect on a slower rate of decline of urine volume. Owing to the statistical power was limited and the imprecision of this measure, including the errors and reliability of urine collection. Moreover, the pooled SMDs in our analyses were calculated using the median, range and/or interquartile range, which could be limited by the sample size of the included studies. Thus, caution must be considered in an interpretation of the findings.

Long-term PD treatment can lead to peritoneum injury by hypertonic PD solutions. Theoretically, RAAS blockade may have important role in “peritoneal protection”, as RAAS may reduce membrane fibrosis and neoangiogenesis, and decreased peritoneal protein loss that occurs over time16–18,24. However, we found that the data for these outcomes were substantially inconsistent, which suggest less reliability of the findings. We conclude that the effects of RAAS blockade on peritoneal membrane integrity remain unclear and warrant further clarification. Both pairwise and NMA had similar adverse outcomes across all other treatments, however, we underscore that the results were surrounded by uncertainty of effects estimated.

To our knowledge, this systematic review and NMA consisted of unpublished data, and more comprehensive than previous reviews as we did not impose any language restrictions. Our study was conducted by retrieving evidence from both RCTs and non-randomised studies, which reflect real-world practices.

However, several potential limitations of our study are worth noting. Firstly, even sophisticated adjusted cohort studies may be subjects to unmeasured confounders40. Moreover, the limited interconnections in the evidence networks studies should be stated that an indirect estimate is susceptible to confounding. Thus, findings should be interpreted with caution since it does not always agree with respect to direct evidences.

Secondly, heterogeneity of outcomes definition is an important concern because of measurement and definition of endpoint were not standardised and defined poorly across included studies. Given the low rate of reporting, measurement of urine volume as well as the incidence of anuria may have been under-ascertained if patients stopped collecting their urine when anuria is near or reached, particularly in the non-randomised studies. We therefore suggest that future trials with high methodological quality are needed.

Thirdly, the interpretation of our subgroup analyses was limited by small sample size and number of studies. Moreover, details of clinically relevant characteristic such as peritoneal equilibration test status, UF, and history of peritonitis were not fully reported across included studies. As such, several preplanned subgroup analyses cannot be performed to explore treatment effects in different subpopulations.

Fourthly, based on crossover design, carry-over effect may contribute to effect estimates of included studies which could have biased results towards a neutral effect on some outcomes, and against specific treatment comparisons. No further significant association was observed between treatment comparisons and change in D/P Cr ratio and 4-hour UF volume, whereas risk of dry cough substantially increases among ACEI users (OR 17.83 [1.22–261.44], Supplementary, Table S13) after removing the crossover design.

Fifthly, the majority of included studies were conducted in Asian countries and restricted largely to CAPD patients. This might affect our findings by limiting the generalisability to other ethnic/racial groups and individuals PD who treated with other PD modalities.

Lastly, because of primary data for the effects of MRAs and DRIs on RKF and PMF were scant, our review was unable to make any meaning conclusions regarding the comparative effectiveness and safety of these drugs among PD patients.

Our findings provide the evidence to support the use of ACEIs or ARBs among PD patients, which in line with the ISPD guidelines for assessment and management of RKF as a cardiovascular risk factor30. Besides cardiovascular benefits, we therefore advise the long-term use (≥12 months) of ACEIs or ARBs as an essential treatment compared with other antihypertensive, and this may improve mortality in these population as well. Thus, it is reasonable to suggest that clinician should prescribe ACEIs or ARBs in adult PD patients with significant RKF.

Currently, no recent controlled trial provides direct comparison between MRAs and ACEIs or ARBs treatment among PD patients, thus future trials with high methodological quality are needed. To understand the complex relationship between peritoneum and the kidney, clarifying the effects of each other is required. Besides systemic RAAS blockade, additional experimental study is required to determine effective strategies to decrease local peritoneal RAAS activation. In addition, dose- and duration response relationship of RAAS blockade for these outcomes also needs further investigation.

In summary, our analysis reveals that ACEIs or ARBs treatment is the most effective strategies for preserving RKF, and has similar clinical adverse outcomes across all other treatments. However, little evidence is available for effects of RAAS blockade on PMF in adults PD patients.

Methods

This study was performed in accordance with guidelines for comparative effectiveness reviews produced by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality44, and has been reported in line with guidance from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension statement for NMA (Supplementary, Appendix-I)45. The pre-specified protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42018083525). Details of the methodology used for this review are described in Supplementary, eMethods.

Data sources and search strategy

In brief, we searched electronic databases, including PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, and grey literature from inception to May 31, 2019, without language restrictions (search strategies are described in Supplementary, Appendix-II). Two independent reviewers screened eligible titles/abstracts and relevant full-text studies. Any disagreement was resolved through a team discussion.

Study selection and outcomes

We included both RCTs (parallel and cross-over trials) and non-randomised studies (quasi-experimental and retrospective/prospective cohort studies with a control group) that: (i) included adult participants aged ≥18 years; (ii) addressed the effects of the RAAS blockade with ACEIs, ARBs, DRIs, and MRAs and reported at least one of the outcomes of interest; and (iii) compared RAAS blockade against placebo/active control with follow-up of one week onward. We excluded studies that: (i) were N-of-one, case-control, cross-sectional, case series/case reports, and phase I or II study design; (ii) used a dual ACEIs and ARBs treatment; (iii) compared intraperitoneal administered of intervention/control groups; and (iv) included participants that received both PD and haemodialysis treatments.

The primary outcomes of interest were key parameters on RKF and PMF, including (i) rGFR, on the basis of 24-hour collection and calculated using the valid equation proposed (mL/min or mL/min/1.73 m2); (ii) urine volume, using a 24-hour timed urine collection or self-reported (mL/day); (iii) the incidence of anuria (defined according to each study, commonly <200 mL/day); (iv) ratio of D/P Cr by the peritoneal equilibration test; and (v) acceptability of treatment (defined to be study dropout for any reason).

The secondary outcomes of interest were: (i) 4-hour UF volume by the peritoneal equilibration test (mL/4-hour); (ii) daily UF volume (mL/day); (iii) adverse events, including hyperkalaemia (as defined by study authors, commonly >5.5 mmol/L), dry cough, hypotension, dizziness, angioedema/oedema, gynaecomastia, and peritonitis; (iv) HRQOL; and (v) healthcare expenditure (e.g. costs, hospitalisation).

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted the following data using a standardised extraction form: study- and participant-characteristics, interventions (specific RAAS blockade classes [for studies that cannot be specified the class of RAAS blockade, we reported separately as mixed treatment]), control groups, dose of drug, concomitant medications, and predefined outcomes. Data extraction was cross-checked and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. For studies with missing or incomplete data, the study authors were contacted by email for clarification. Two reviewers independently performed a critical appraisal of the risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool for RCTs/quasi-experimental46 and the NOS for cohort studies47.

Data synthesis and analysis

Only full-text articles were considered in the primary analysis. We employed a two-step approach to the performance of both pairwise meta-analysis and NMA. For the first step, only RCTs data were used. Subsequently, data from both RCTs and non-randomised studies were incorporated. For any continuous outcome parameters, the summary results from individual studies were captured as the mean difference in the changes with the formula: ∆valuechange = valueendpoint – valuebaseline, in which SD2change = [SD2baseline + SD2endpoint – (2 × ρ × SDbaseline × SDendpoint)], where ρ stands for the correlation coefficient. We anticipated ρ value of 0.75 between the baseline and endpoint values and equal variances during the RAAS blockade and control groups. Additionally, an estimated value of 0.56 was considered in a sensitivity analysis as described by Szeto et al.38. For meaningful interpretation of treatment effects, a mean difference of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 are considered to be small, medium, and large, respectively48.

A random-effects NMA was performed to compare indirect treatment effects for each outcome using a frequentist model. As a measurement varied across studies, the findings from NMAs were expressed in terms of SMDs for continuous outcomes and ORs for dichotomous outcomes, along with 95% CIs. The surface under the cumulative ranking curve, a relative ranking probability, was also estimated for each RAAS blockade class, and rankograms were also prepared49.

We evaluated characteristics of populations and study designs across all included studies to evaluate the assumption49,50. The network heterogeneity was assumed as the τ2 statistics, a between-study variance51–53. Assessment for consistency of direct and indirect effects was performed using three different approaches: the loop-specific approach, the node-splitting approach, and the design-by-treatment interaction model49,50,54. Comparison-adjusted funnel plots were used to investigate for reporting bias and potential effects of small studies55.

Preplanned subgroup analyses and meta-regressions were carried out to address potential sources of heterogeneity, including study sample size (≤50 vs. >50 participants), geographical region (Asian vs. non-Asian countries), age (<65 vs 65 years), sex (as reflected by % female), baseline rGFR, urine volume, D/P Cr, blood pressure, history of diabetes, and PD modality.

A series of sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of primary findings. These included: (i) assuming the correlation coefficient of 0.56 for estimating the SDchange38; (ii) excluding studies from mainland China to avoid a systematic bias related to the trustworthiness as described elsewhere56,57; (iii) excluding crossover studies to avoid carry-over effects58,59; (iv) excluding studies which classified as mixed treatment intervention; and (v) post-hoc analysis by adding unpublished conference abstracts.

Statistical significance for all tests was 2-tailed, with P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using STATA version 14.0 (StataCorp LP).

Grading the strength of evidence

To assess the strength of evidence for each outcome, the GRADE approach was performed and classified into insufficient-, low-, moderate-, or high-quality evidence60,61. The confidence in estimates could be downgraded or upgraded according to the risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, and indirectness. Any disputes were resolved by a third reviewer.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant from the Faculty of Pharmacy, Chiang Mai University. No funding source had any role in the study concept and design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, writing the report, or in the decision to submit for publication. The authors thank Pajaree Mongkhon, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Phayao, Phayao, Thailand., who helped develop search strategies.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: S Phatthanasobhon, S.N. and C.R.; Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: All authors; Drafting of the manuscript: S Phatthanasobhon, S.N., K.T. and C.R.; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: S Panyathong, Y.S., B.H., M.S. and K.N.; Statistical analysis: S Phatthanasobhon, S.N. and C.R.; Administrative, technical, or material support: S.N. and K.T.; Study supervision: S.N. and C.R. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Data availability

All data generated and analysed in this review were drawn from the existing article and reported along with the Supplementary Materials.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Surapon Nochaiwong and Chidchanok Ruengorn.

Contributor Information

Surapon Nochaiwong, Email: surapon.nochaiwong@gmail.com.

Chidchanok Ruengorn, Email: chidchanok.r@elearning.cmu.ac.th.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-55561-5.

References

- 1.Mehrotra R, Devuyst O, Davies SJ, Johnson DW. The Current State of Peritoneal Dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3238–3252. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams, J. D., Craig, K. J., von Ruhland, C., Topley, N. & Williams, G. T. The natural course of peritoneal membrane biology during peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int Suppl. S43–49 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bargman JM, Thorpe KE, Churchill DN. Relative contribution of residual renal function and peritoneal clearance to adequacy of dialysis: a reanalysis of the CANUSA study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2158–2162. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Termorshuizen F, et al. The relative importance of residual renal function compared with peritoneal clearance for patient survival and quality of life: an analysis of the Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD)-2. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:1293–1302. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(03)00362-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Wal WM, et al. Full loss of residual renal function causes higher mortality in dialysis patients; findings from a marginal structural model. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2978–2983. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heimburger O, Waniewski J, Werynski A, Tranaeus A, Lindholm B. Peritoneal transport in CAPD patients with permanent loss of ultrafiltration capacity. Kidney Int. 1990;38:495–506. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heimburger O, Wang T, Lindholm B. Alterations in water and solute transport with time on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 19. 1999;Suppl 2:S83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawaguchi Y. National comparisons: optimal peritoneal dialysis outcomes among Japanese patients. Perit Dial Int. 19. 1999;Suppl 3:S9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nessim SJ, Bargman JM. The peritoneal-renal syndrome. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:302–306. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marron, B., Remon, C., Perez-Fontan, M., Quiros, P. & Ortiz, A. Benefits of preserving residual renal function in peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int Suppl. S42–51 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Moist LM, et al. Predictors of loss of residual renal function among new dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:556–564. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V113556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li PK, Chow KM, Wong TY, Leung CB, Szeto CC. Effects of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor on residual renal function in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:105–112. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki H, Kanno Y, Sugahara S, Okada H, Nakamoto H. Effects of an angiotensin II receptor blocker, valsartan, on residual renal function in patients on CAPD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:1056–1064. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito Y, et al. Long-term effects of spironolactone in peritoneal dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:1094–1102. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013030273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yelken B, et al. Effects of spironolactone on residual renal function and peritoneal function in peritoneal dialysis patients. Adv Perit Dial. 2014;30:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamoto H, et al. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in the pathogenesis of peritoneal fibrosis. Perit Dial Int. 2008;28(Suppl 3):S83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimura H, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade ameliorates peritoneal fibrosis in new rat peritonitis model. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F1084–1093. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00565.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto D, Takai S, Hirahara I, Kusano E. Captopril directly inhibits matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis therapy. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:762–764. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolesnyk I, Noordzij M, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. A positive effect of AII inhibitors on peritoneal membrane function in long-term PD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:272–277. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rojas-Campos E, et al. Effect of oral administration of losartan, prazosin, and verapamil on peritoneal solute transport in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25:576–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuya R, Odamaki M, Kumagai H, Hishida A. Impact of angiotensin II receptor blocker on plasma levels of adiponectin and advanced oxidation protein products in peritoneal dialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2006;24:445–450. doi: 10.1159/000095361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jing S, Kezhou Y, Hong Z, Qun W, Rong W. Effect of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors on prevention of peritoneal fibrosis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton). 2010;15:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2009.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolesnyk I, Noordzij M, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. Treatment with angiotensin II inhibitors and residual renal function in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2011;31:53–59. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2009.00088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basturk T, et al. The effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on peritoneal protein loss and solute transport in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;67:877–883. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(08)04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yongsiri S, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of spironolactone for hypokalemia in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. Ther Apher Dial. 2015;19:81–86. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen JI, Saxena AB, Vangala S, Dhaliwal SK, Winkelmayer WC. Renin-angiotensin system blockers and residual kidney function loss in patients initiating peritoneal dialysis: an observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:196. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0616-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y, Ma X, Zheng J, Jia J, Yan T. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on cardiovascular events and residual renal function in dialysis patients: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:206. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0605-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang, L., Zeng, X., Fu, P. & Wu, H. M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for preserving residual kidney function in peritoneal dialysis patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. CD009120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Akbari A, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in peritoneal dialysis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Perit Dial Int. 2009;29:554–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang AY, et al. ISPD Cardiovascular and Metabolic Guidelines in Adult Peritoneal Dialysis Patients Part I - Assessment and Management of Various Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Perit Dial Int. 2015;35:379–387. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2014.00279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phakdeekitcharoen B, Leelasa-nguan P. Effects of an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker on potassium in CAPD patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:738–746. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(04)00954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Favazza A, et al. Peritoneal clearances in hypertensive CAPD patients after oral administration of clonidine, enalapril, and nifedipine. Perit Dial Int. 1992;12:287–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, Xiao MY. Protective effects of valsartan on residual renal function in patients on CAPD. Chinese. Journal of Blood Purification. 2005;4:605–606. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhong H, et al. Effcts of irbesartan on residual renal function in peritoneal dialysis patients. Chin J Nephrol. 2007;23:413–416. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wontanatawatot. The effect of enalapril and losartan on peritoneal membrane in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. Master of Science Program in Medicine thesis, Chulalongkorn University (2009).

- 36.Reyes-Marin FA, Calzada C, Ballesteros A, Amato D. Comparative study of enalapril vs. losartan on residual renal function preservation in automated peritoneal dialysis. A randomized controlled study. Rev Invest Clin. 2012;64:315–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson DW, et al. Predictors of decline of residual renal function in new peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2003;23:276–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szeto CC, et al. Predictors of residual renal function decline in patients undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2015;35:180–188. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2013.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jearnsujitwimol V, Eiam-Ong S, Kanjanabuch T, Wathanavaha A, Pansin P. The effect of angiotensin II receptor blocker on peritoneal membrane transports in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89(Suppl 2):S188–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cameron C, et al. Network meta-analysis incorporating randomized controlled trials and non-randomized comparative cohort studies for assessing the safety and effectiveness of medical treatments: challenges and opportunities. Syst Rev. 2015;4:147. doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0133-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1456–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klahr S, et al. The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood-pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:877–884. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403313301301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersen S, Tarnow L, Rossing P, Hansen BV, Parving HH. Renoprotective effects of angiotensin II receptor blockade in type 1 diabetic patients with diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2000;57:601–606. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. AHRQ Publication No. 10(14)-EHC063-EF. Chapters available at, http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), January 2014. [PubMed]

- 45.Hutton B, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:777–784. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Higgins, J. et al. In Cochrane Methods (eds J. Chandler, J. McKenzie, I. Boutron, & V. Welch). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 10 (Suppl 1), 10.1002/14651858.CD201601.

- 47.Wells, G. et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available at, http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed June 29, 2019.

- 48.Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn, (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988).

- 49.Chaimani, A., Salanti, G., Leucht, S., Geddes, J. R. & Cipriani, A. Common pitfalls and mistakes in the set-up, analysis and interpretation of results in network meta-analysis: what clinicians should look for in a published article. Evid Based Ment Health. pii: ebmental-2017-102753. (2017 Jul 24.). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Mills EJ, Thorlund K, Ioannidis JP. Demystifying trial networks and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f2914. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barth J, et al. Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: a network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rhodes KM, Turner RM, Higgins JP. Predictive distributions were developed for the extent of heterogeneity in meta-analyses of continuous outcome data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turner RM, Davey J, Clarke MJ, Thompson SG, Higgins JP. Predicting the extent of heterogeneity in meta-analysis, using empirical data from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:818–827. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Veroniki AA, Vasiliadis HS, Higgins JP, Salanti G. Evaluation of inconsistency in networks of interventions. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:332–345. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaimani A, Salanti G. Using network meta-analysis to evaluate the existence of small-study effects in a network of interventions. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3:161–176. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woodhead M. 80% of China’s clinical trial data are fraudulent, investigation finds. BMJ. 2016;355:i5396. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cyranoski D. China cracks down on fake data in drug trials. Nature. 2017;545:275. doi: 10.1038/nature.2017.21977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Curtin F, Elbourne D, Altman DG. Meta-analysis combining parallel and cross-over clinical trials. III: The issue of carry-over. Stat Med. 2002;21:2161–2173. doi: 10.1002/sim.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nolan SJ, Hambleton I, Dwan K. The Use and Reporting of the Cross-Over Study Design in Clinical Trials and Systematic Reviews: A Systematic Assessment. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berkman ND, et al. Grading the strength of a body of evidence when assessing health care interventions: an EPC update. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:1312–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Puhan MA, et al. A GRADE Working Group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;349:g5630. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analysed in this review were drawn from the existing article and reported along with the Supplementary Materials.