Abstract

Mental healthcare is largely unavailable throughout Haiti, particularly in rural areas. The aim of the current study is to explore perceived feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of potential culturally adapted interventions to improve mental health among Haitian women. The study used focus group discussions (n=12) to explore five potential interventions to promote mental health: individual counseling, income-generating skills training, peer support groups, reproductive health education, and couples’ communication training. Findings indicate that individual counseling, support group, and skills training components were generally anticipated to be effective, acceptable, and feasible by both male and female participants. That being said, participants expressed doubts regarding the acceptability of the couples’ communication training and reproductive health education due to: a perceived lack of male interest, traditional male and female gender roles, lack of female autonomy, and misconceptions about family planning. Additionally, the feasibility, effectiveness, and acceptability of the components were described as dependent on cost, proximity to participants, and inclusion of a female health promoter that is known in the community. Given the lack of research on intervention approaches in Haiti, particularly those targeting mental health, this study provides a foundation for developing prevention and treatment approaches for mental distress among Haitian women.

Keywords: Mental health, Haiti, task-shifting, feasibility, acceptability

Background

Haiti is a site of myriad stressors, from poverty and high infant mortality to natural disasters and a history of political instability. Despite a high burden of mental illness, few resources are available for formal mental healthcare, particularly in rural areas (Raviola et al., 2012; Wagenaar et al., 2012). Women are particularly at risk for mental illnesses and their sequelae, yet insufficient research has focused on the particular pathways placing women at risk or the most effective avenues for prevention. An exploratory study of women’s stressors and mental health in two rural communities in Haiti found reproductive health stressors (e.g., lack of reproductive autonomy, child-rearing stressors) to be primary stressors impacting the well-being of women. This study highlighted the need for additional research on the important link between reproductive health and mental health outcomes for women and families. The current study expands on this research to explore perceptions of proposed interventions for the mental health of Haitian women, either by addressing upstream risk-factors associated with reproductive health, or through treatment and support.

Currently, reliable data on the overall prevalence of mental health disorders in Haiti is not available due to the lack of a national public health surveillance system (Safran et al., 2011; WHO 2005; WHO 2010). However, several studies have examined psychological disorders and the need for intervention in Haiti. Wagenaar et al., (2012) found high rates of depression symptomology and suicidal ideation in a sample of men and women in the rural Central Plateau. Furthermore, Martsolf (2004) assessed a sample of hospital patients in Haiti and determined that 54% met the criteria for major depressive disorder, suggesting a need for mental health intervention. Following the earthquake, Safran et al., (2011) found that 1–2% of 30,000 individuals seen in a healthcare clinic within a 7-week period were primarily seeking care for psychological health. These numbers provide evidence of a clear need for psychological services. Although evidence on mental health in Haiti is limited, several studies indicate a high prevalence of psychological disorders and the need for intervention.

Maternal Mental Health

Globally, depression and anxiety rates are higher among women (WHO 2017). Maternal mental health is an important social need which has implications for short- and long-term physical health outcomes (Scott et al., 2016), premature mortality (Walker et al., 2015; Chesney et al., 2014), reduced economic productivity (Chisholm et al., 2016), and poor physical, cognitive, and socio-emotional outcomes for children (Kingston et al., 2014). Of particular concern is the effect of maternal depression in low-income settings, as evidence indicates that the negative impact is amplified in such resource-constrained contexts (Tyano et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2007). Maternal mental health problems can have negative psychological and attitudinal impacts that can adversely affect the woman’s ability to manage child carerelated tasks and express sensitivity and responsiveness in caregiving (WHO 2008; Rahman et al., 2013). Studies evaluating the relationship between women with common mental disorders (CMDs) and child wellbeing in low- and middle-income countries identify positive correlations between CMDs in mothers and several childhood outcomes including malnutrition, infectious disease, hospital admissions, and worsened physical, cognitive, social, behavioral, and emotional development (Anoop et al., 2004; Harpham et al., 2005; Rahman et al., 2004; Patel et al., 2003; Walker et al., 2007).

Risk factors for mental health problems during the perinatal period and after childbirth include unintended pregnancy, adolescent pregnancy, poverty, difficulty with husband’s behavior, lack of reproductive autonomy, and a large number of children, among others. (WHO 2008; Fischer et al., 2012; Faisal-Cury et al., 2004; Nhiwatiwa et al., 1998; Rahman et al., 2003). These findings suggest that interventions targeting maternal mental health should involve not only approaches relating to psychotherapeutic strategies, but should also address reproductive health, financial stability, and marital relationships.

Access to Mental Healthcare

In Haiti, approximately 40% of the population lacks access to healthcare (USAID 2017). Where healthcare services are available, 40% of the rural population has no available primary health care (World Bank 2006; WHO 2010). Lacking basic healthcare, mental health services have historically not been prioritized by the government, and very few mental health professionals work in the nation (WHO 2010). Estimated counts of professionals from the 2003 PAHO/WHO report revealed 10 psychiatrists and 9 psychiatric nurses working in the public sector, all centralized in Port-au-Prince. More recent estimates via a faculty examination suggest an increase in psychiatric professionals in Haiti, yet these numbers remain woefully inadequate for the population (Nicolas et al., 2012).

Sustainability of psychological services appears to be an obstacle to care. Nicolas et al., (2012) noted that non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and international organizations have a history of providing care in Haiti for short periods of time following natural disasters, leaving individuals without care after approximately three to six months. In addition, training for psychology and social work graduate students who provide care is often insufficient (Nicholas et al., 2012). One notable attempt to improve access to care involves the healthcare NGO Partners in Health, and its sister organization Zanmi Lasante, that work with local clinicians in Haiti to incorporate psychological services into the primary care system. They incorporate medications, psychoeducation, and psychotherapy into existing primary care clinics and mobile clinics to treat patients (Fils-Aimé et al., 2018; Grelotti et al., 2015; Grelotti 2013; Raviola et al., 2012). Such services should be replicated outside of the two departments (Central Plateau, Artibonite) that PIH/ZL serves. Additionally, although efforts are in place to improve access to mental healthcare, expanding community-based mental healthcare should be a priority in order to reduce the unmet need for psychological services (Belkin et al., 2011).

Idioms of Distress and Explanatory Models of Mental Illnesses

Mental health in Haiti is not understood and expressed in an identical manner to “Western” perceptions and categorizations of psychological illnesses. Cross-culturally, distinct idioms of distress and explanatory models of illness are used to convey the perceived origin and impact of negative mental and physical states (Kohrt and Hruschka 2010; Nichter 1981). Many idioms of distress in Haiti can be categorized as relating to the head (tèt) or the heart (kè), while cultural syndromes like “thinking too much” are commonly used to identify an individual in distress (Keys et al., 2012; Kaiser et al., 2014). In a biomedical setting, these idioms of distress are often misdiagnosed as purely physical symptoms, disregarding the psychological contributions in the interpretations of illness (Keys et al., 2012).

Vodou, a complex and syncretic magico-religious system in Haiti, is sometimes involved in the explanatory framework for mental illness, usually involving concepts of supernatural harm (Farmer 1992; Vonarx 2007; WHO 2010). This includes the perception of evil spirits being sent by jealous individuals or supernatural possession due to individuals’ failure to serve familial spirits (Carrazana et al., 1999; Desrosiers and Fleurose 2002; Sterlin 2006; James 2008; WHO 2010). At the same time, these explanatory models of illness are often misunderstood or caricatured by outsiders, who also overestimate their influence on perceived effectiveness of biomedical treatment methods. For example, Khoury et al., (2012) report that, although observers often claim that Haitians will eschew biomedical mental healthcare due to Vodou beliefs, their respondents described having sought out mental healthcare in a biomedical setting but found it ineffective due to the inadequacy of care provided. These findings suggest space for community-based treatment approaches and involvement of local community members in interventions, in order to properly address psychological distress in the Haitian context.

Psychotherapy and Task-Shifting Approaches

In settings like Haiti where mental health professionals are lacking, task-shifting can be an effective method for reducing the treatment gap (Kakuma et al., 2011; Eaton et al., 2011). In this approach, community members with little to no formal qualifications are trained to deliver particular interventions that would usually be accomplished by specialists (WHO 2008; Petersen et al., 2001, Fulton et al., 2011).

There is significant evidence supporting the effectiveness of task-shifting for delivering psychotherapy interventions (Barnett et al., 2018; Rahman et al., 2013, 2016; Singla et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2015). Solutions-focused and stress management therapeutic approaches are effective in a variety of settings. For example, studies in South Africa and Zimbabwe that aimed to reduce depression in women using problem-solving therapy demonstrated statistically significant reduction in severity of CMDs (Nyatsanza et al., 2016; Chibanda et al., 2015). In addition, Problem Management Plus, a low-intensity therapeutic approach based on problem-solving and behavioral treatment techniques using lay helpers was effective at reducing post-traumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms in two randomized controlled trials (Bryant et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2017; van’t Hof 2018). These studies indicate that the use of task-shifting in low-skill psychotherapy interventions has been effective in low-income settings and may be relevant to the Haitian context.

Reproductive Health in Haiti

There is an evident bi-directional relationship between mental health and reproductive health. Poor mental health increases the risk for early and unwanted pregnancies (WHO 2008), and such unintended pregnancies and subsequent child-rearing stressors can negatively impact the mental health of women (Gipson et al., 2008).

In Haiti, an estimated 35.3% of women have an unmet contraceptive need, among the highest in the world (USAID 2016). Haiti is also one of the highest-ranked countries for unmet need to postpone first birth in married women (ranked 2 out of 52) and in unmet need for sexually active never-married women (59%) (Sedgh et al., 2016). Reasons for unmet need in Haiti include gender inequities, lack of resources, lack of knowledge, religion, and a largely rural population (USAID 2016; Casterline et al., 2000). Given the relevance of gender and power dynamics to issues of reproductive health, including husband opposition to contraception, the relationship between reproductive autonomy and mental health is also of importance. As is common in global health settings, most sexual and reproductive rights-based interventions carried out in Haiti have been centered around HIV/STIs (Logie et al., 2014). There is a dearth of information regarding mental health and reproductive health initiatives being delivered in tandem in Haiti.

In a previous study on women’s stressors and mental health in Léogáne, Haiti, we found that women described their stress as driven by economic dependence on men, paired with male expectations for having children, in the context of resource scarcity (BLINDED). This led to reduced reproductive and economic autonomy, child-rearing stressors, and poor physical and mental health outcomes. This study also revealed a lack of existing resources for women to cope with these stressors. These findings suggest that effective mental health interventions in the Léogáne context should include both preventive components - addressing reproductive health needs, economic autonomy and power dynamics - and treatment components.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of the current study is to explore perceived feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness, as well as necessary cultural adaptations, of potential interventions to improve mental health among Haitian women. Based on prior research, the intervention components explored included individual counseling, income-generating skills training, peer support groups, reproductive health education, and couples’ relationship training.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in the Léogane Commune of Haiti in May-July 2017. Haiti is located in the Caribbean Sea and was established in 1804 as the world’s first Black Republic, following a successful slave uprising. The official languages in Haiti are French and Kreyòl. Political and economic instability, a long history of international military and political intervention, as well as numerous natural disasters have slowed Haiti’s development; it ranks 154th out of 177 countries on the Human Development Index. Approximately 24% and 59% of the country’s population are in extreme poverty (less than 1.25 USD a day) and poverty (less than 2 USD a day), respectively (Singh and Barton 2015). The rural poor, who constitute two-thirds of the total population, lack access to safe water and electricity. Haiti has an agricultural economy; as such, farming is the main source of rural income (WHO 2010; Caribbean Country Management Unit 2006; UNSD 2010).

Differences in wealth, education, and language – resulting from historically-rooted forms of exclusion – define Haiti’s class hierarchy (Desrosiers and Fleurose 2002). Approximately 72% of the population has only a primary school education, and only 1% of the population has a university level education. Literacy levels are low; about 80% of the rural population and 47% of those in urban centers lack the ability to read French, the official language of education and business (WHO 2010; Caribbean Country Management Unit 2006).

Families typically adhere to well-defined gender roles, where women are primarily responsible for household tasks, such as food preparation, child care, working in commerce, and managing the family budget, and men are typically the family breadwinners and are involved in agricultural work or manual labor (Coreil 1983a; De Zaldoundo and Barnard 1995). Most Haitians identify as both Christian and Vodou (sèvi lwa, serve the spirits; WHO 2010), although this results in a tenuous relationship, as Vodou practice has historically been targeted by the Catholic Church, Haitian and foreign governments, and more recently by the increasing numbers of evangelical Christians in Haiti.

Léogáne has a population of 134,000 and is located 16 miles from Port-au-Prince (World Population Review 2018). The epicenter of the 2010 earthquake was 5 miles outside of the town, which caused significant damage and casualties in the area. It is estimated that approximately 80–90% of the buildings in Léogáne were destroyed at the time. In Haiti, about 316,000 individuals were reported dead or missing, many of whom were residents of Léogáne (GOH 2010; Eberhard et al., 2010). As a result, there was a large influx of disaster relief efforts in the damaged areas to address physical and mental health needs (PAHO/WHO 2011).

Study design

We used focus group discussions (FGDs) to explore perceived feasibility, acceptability, and necessary adaptations of potential mental health intervention components. Intervention components were selected through prior research on female stressors in the study site and informed by evidence-based interventions implemented in similar settings. The study was conducted in Léogáne town and Fondwa, a rural community in Léogáne Commune.

Intervention component selection

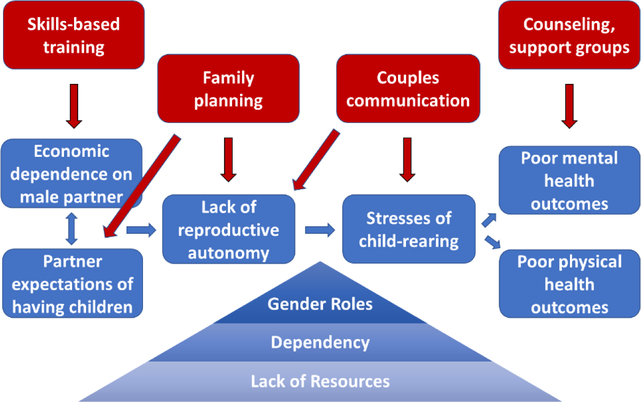

Exploratory research conducted one-year prior in Haiti identified the most common stressors for women (BLINDED). The identified stressors largely focused on lack of economic and reproductive autonomy and their effects, including having too many children, stresses of taking care of children, “thinking too much,” and lack of support system, among others. Through examination of these findings, five main intervention targets were developed: individual mental health, female empowerment through skills training, peer support groups, reproductive health education, and couples’ communication skills (see Figure 1). A literature review on prior effective interventions that targeted these areas was conducted in order to identify evidence-based intervention components to explore in the current study.

Fig 1:

Drivers of women’s stress (blue) and proposed intervention components (red). From (BLINDED).

Data collection

Four local research assistants (RAs) facilitated all data collection. RAs underwent a three-day training that included information on participant recruitment processes, consent procedures, explanation and practice of FGD procedures, piloting an FGD, discussion of appropriate, non-stigmatizing translations of mental health-related terminology into Kreyòl, and research ethics.

Since formative research demonstrated the important influence of male partners, both male and female perspectives were included. Twelve FGDs were conducted, stratified by gender and consisting of 5–8 individuals each. Participants were recruited using convenience and purposive sampling. RAs traveled to centralized public areas in Léogáne and Fondwa to recruit research participants who were 18 years of age or older. Three of the FGD consisted of participants from established groups in the Léogáne or Fondwa area, such as a women’s group, members of a vocational training school, and religious leaders within the community. FGDs were conducted in somewhat private areas of public locations, such as in secluded areas of libraries and parks.

A summary script describing each proposed intervention component was developed and translated into Kreyòl (see Box 1). Each FGD discussed either the mental health focused components (items 1–3 in Box 1) or the reproductive health focused components (items 4–5). FGDs were each facilitated by a Haitian RA, who explained the concept and details regarding each intervention component, one-by-one, and asked scripted questions to the group about expected feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness; whether similar interventions existed; necessary adaptations for each component; and delivery considerations (i.e. logistics, format, target population, and delivery agent - referred to in FGDs as a Health Promoter). Another RA translated the discussion to two American researchers, who took notes and recorded the order of individuals speaking to facilitate matching to transcriptions. Only one American researcher was able to speak Kreyól and communicate directly with FGD participants. The other American researchers received summary translations of the discussion from an RA and asked probes to the participants, which were translated into Kreyòl via the facilitator, to prompt further discussion on particular topics of interest.

Box 1: Proposed intervention components as described in FGDs.

1. Individual Counseling

If a woman is feeling stressed, she would be able to meet with a Health Promoter in a private area. The Health Promoter would be trained in Problem-Solving Therapy and would help the woman develop solutions to her problems through open discussion and goal-setting. The session would last approximately an hour, and at the end of the session an appointment would be made for the following week. At the next session, the woman would be able to meet with the same Health Promoter and discuss whether the solutions were successful and what revisions needed to be made in order to make them more effective. The woman would be offered a total of six sessions. [This component is based on a problem-solving therapy intervention implemented in Zimbabwe by Chibanda et al. (2011) and Problem Management Plus, an intervention for common mental disorders developed by WHO (Dawson et al., 2015)].

2. Skills Training

Once a week, women could come together in groups of 8–10 to learn useful skills, such as making bracelets or flower art. These workshops would be taught by a community member who is proficient in that skill and would last approximately an hour. These skills could be used as hobbies and as a way for women to get out of the house and meet with other women. They could also be used for economic gain if the women choose to sell their products in the future. There would be a referral system between the mental health counseling and the skills training workshops.

3. Support Group

The aim of this group is to allow women in the community to come together to discuss their problems and how they handle them in order to receive support and advice. The group would meet weekly for approximately an hour and would be led by trained facilitators. Each week, these discussions would be focused on one of the top stressors indicated by women, such as thinking too much, taking care of children, and having too many children, although conversations do not need to be exclusively about these topics.

4. Reproductive Health Education

Workshops would be held to educate community members about different topics in family planning and reproductive health. Separate workshops would be held for men and women, and each would be conducted by a Health Promoter, who would be trained in anatomy, contraceptive methods, sexually transmitted diseases, and couple relationship skills. During each session, the Health Promoter would educate and counsel women and men on different types of family planning and provide information on how to receive the form they want.

FGDs were audio-recorded, transcribed directly from Kreyòl to English, and analyzed using thematic analysis. Analysis included both deductive (e.g., intervention components, feasibility) and inductive themes (those identified by reviewing transcripts, e.g. religion). These themes were operationalized into codes, which were reviewed, modified, and agreed upon by team members. FGD transcripts were coded using NVivo software. Code summaries were developed by reviewing data coded for each theme, separated by intervention component and accounting for differences by gender of participants.

Ethical considerations

All study procedures were approved by IRB Misyon Sante Fanmi Ayisyen and Duke University IRB. All participants provided verbal consent after having the study described to them and prior to data collection activities.

Results

Existing interventions

No participants knew of interventions similar to the individual counseling intervention that currently existed in the community. A clinic run by Doctors Without Borders was mentioned, but this was targeting physical illness and no longer existed in the community. Participants also explained that “Health ministries” also ran a program that talked to women, but it was not effective and occurred in a group setting. Reasons for the ineffectiveness included that the groups would break apart, and attendance was low.

In relation to the support group, women in Fondwa said that there was an existing women’s group; however, it did not focus on stress. They did say, however, that they talked about women’s problems in the group. In Léogáne, most of the women and men said that programs similar to the support group component did not exist in the community. One woman mentioned that she knew of a group, while one man indicated that several women’s groups existed in the countryside, but none existed in Léogáne.

In addition, one intervention that was similar to the skills training component was a free trade school in Port-au-Prince that was run by one of the participants. She teaches skills such as cooking, crocheting, and sewing for free, but this school is located far from Léogáne and is difficult to reach. Other similar interventions that the women mentioned were a bracelet-making training for children at a local church and a vocational school that costs money. There was also mention of a cooking class that no longer existed. Some participants said that there were similar interventions that only lasted 2 or 3 days and, therefore, were not sustainable.

Several participants explained that family planning workshops that were similar to the proposed reproductive health education workshop had existed at various points in time, but they were not continuous. Women in Fondwa said that the priest recently held a family planning workshop, but not everyone was able to attend. In this workshop, they learned about reproductive health but explained that in other interventions, they were simply given condoms and other family planning methods. The women also said that a group of foreigners did a family planning workshop at the clinic and that an organization called Kore Timoun did a similar workshop as well, but they were not consistent programs. One woman spoke about a training that was done with older women. Most men said that they did not know of similar interventions that currently existed but that the Red Cross had done something similar in the past.

For the couples’ communication training, the majority of participants said that a similar intervention did not exist in the community. However, there were two women in Léogáne who said that something similar did exist. Specifically, one of them said that people used to come into the community and talk about the same subject matter, but she did not go into greater detail. One man said that St. Croix radio used to do trainings for couples, but the other men mentioned that similar interventions did not exist or that they had not heard of any.

Perceived Effectiveness

Participants expected both the individual counseling intervention and support group to be effective at reducing stress in women. This was indicated through discussions regarding the benefits of talking about problems with others. Women specified that the ability to communicate about their problems would be beneficial, describing a characteristic of Haitian culture that promotes the sharing of ideas and thoughts. It was clarified, however, that women’s willingness to speak in a group will be dependent on their level of shyness and the gender of the Health Promoter, with a female health promoter highly preferred. In relation to individual counseling, a recurring theme was the insufficiency of exclusively speaking about problems. Participants felt that, although speaking to the Health Promoter would be beneficial, it would not effectively solve the underlying issues at hand, such as medical problems. Therefore, the women felt that the individual counseling component would be more effective if the Health Promoter gave tangible help, such as medications.

In addition, all participants expected the skills training sessions to be effective. In these sessions, a community member proficient in a useful skill would teach the skill to a group of women. These skills would give the women the ability to create a product or perform a service that could be used for monetary gains. Some examples of possible skills include jewelry making, flower art, and gardening. The two most commonly expressed reasons for the potential usefulness of skills training were people’s interest in gaining knowledge and the potential to earn money through the skills gained from the program. Male participants indicated that the money earned from this component could help empower women to be more independent. This component was identified many times as of the most useful from both men and women.

Both women and men believed that the reproductive health education component would be effective in assisting women in having fewer children. Participants explained that, currently, women tend to have a large number of children, which causes several problems due to the lack of economic means to care for the children. Women expressed that the knowledge gained during the training would be useful to them, as it would help them to take care of their families, prevent sexually transmitted diseases, and understand more about reproductive health. This knowledge was perceived to be important because women would be more likely to use family planning methods if they had an improved understanding of the methods.

Participants disagreed regarding the expected effectiveness of the couples’ communication component, with differences patterned by location of residence and gender of the participant. Women had strong doubts concerning the willingness of men to attend the sessions and stated that men would not apply certain elements of the training, such as contributing to the household responsibilities like folding laundry. Other women believed that the training had the potential to be effective if men chose to participate. It appeared that the women from Léogáne had more optimistic views on the component’s effectiveness compared to women from Fondwa, but in both locations women felt the effectiveness would be inhibited by lack of participation from men. Despite doubts about male participation, some women indicated that this component would be more useful compared to the reproductive health education component. In contrast, men believed that the couple’s communication component would be very effective. They expressed that it would be useful for couples to learn how to improve their communication, which could aid in diminishing other problems, such as having too many children.

Acceptability

Female participants mentioned that the individual counseling, skills training, and support group components would be acceptable for most women in their community, although some would not be comfortable participating due to their personal characteristics, such as shyness, and particular interests. In terms of individual counseling, women reported that they would generally be comfortable discussing their problems with someone in order to receive different perspectives or advice. Occasionally, the concept of individual counseling was compared to talking to a friend, which seemed to ensure comfort surrounding their ability to talk about problems in that context. Other women explained that they would rather seek advice from their friends and mentioned that it is within the Haitian culture to talk and share with their friends. Men believed that the component would be acceptable, needed, and wanted by their community.

A support group was described as acceptable if there is not another women’s group that exists in the area. For example, it was noted that there is already a women’s group in the Fondwa community; therefore, women from that area would not accept another women’s support group. Women may also be unaccepting of a support group run by nuns, due to the discomfort involved with sharing vulnerable topics with them.

For the skills training component, a woman who runs a free skills training program in Port-au-Prince believed that it would be very acceptable as long as it is free, especially because her current program is very well-liked and popular. Two men mentioned that the workshop would help women organize their lives, have an income, and “add value to their own worth.” Other men believed that women gaining professional skills might infringe on the ego of a man and reflect negatively on the profession, since it would include women. There were also men who argued that, if women gain new skills, they would have an even larger list of chores and responsibilities.

For the reproductive health education and couples’ communication components, there was disagreement between female and male participants regarding anticipated acceptability among males. For both components, several men mentioned that men would accept the programs and be willing to participate, as long as they did not have other important obligations occurring at the same time and as long as they were free of cost. Women believed that men would be less interested in the programs than women and, consequently, would not accept the programs.

The reproductive health education component sparked a particular concern by one male regarding limited participation due to the common misconceptions about contraception that circulate in their community – specifically, that contraception causes sickness. The participant declared that people with negative perceptions of family planning methods will not attend the program. This view is consistent with documented beliefs among Haitians that contraceptive use may be harmful to one’s health, such as through causing side effects (Loh 2015; Reyes et al., 2017; Yang 2013).

With regard to the couples’ communication component, women were particularly hesitant to accept the couples’ communication intervention due to its reliance on male attendance. Women agreed that if men chose to participate, then they would accept the program; however, others thought that men would not accept the advice given in such a workshop. The men seemed to be much more optimistic about male acceptability of the program. They did not show such certainty that male participation would be difficult, although some men implied that initial participation rates might be low. Most were very excited and invested in their potential participation in the couples’ communication training workshops. They were most interested in the basic knowledge and mediation for relationship problems that the program offers, especially since they explained communication is lacking for Haitian couples.

All participants believed that there would be distrust from men when women leave to attend the programs, particularly those that do not incorporate husband involvement. Men indicated that several men in their community would have reservations about their wives attending due to jealousy, stating that men would think that women are leaving the home to be unfaithful. One man explained the necessity of advertising the support group and reproductive health education programs over the radio to ensure that the men will hear about the program. The radio is “credible,” according to this individual, which will increase the likelihood that men will allow women to attend the program.

Feasibility

Feedback relating to expected feasibility of all components was positive, except for the couples’ communication program, for reasons described above regarding male involvement. A major barrier that was anticipated to be a hindrance to participation across all intervention areas was transportation. Participants expressed that Tom Gato (the FHM clinic near Fondwa) would be difficult to travel to, but people would attend the programs if they were close to home and free. On the other hand, one participant suggested that programs be located outside of the city in rural areas because individuals in those areas have less access to hospitals.

For the individual counseling intervention, low levels of literacy were noted as a potential barrier as people who are illiterate may not participate due to feelings of shame. Participants described that low levels of education could be stigmatizing, and illiterate individuals might feel that professionals would look down on them. In addition, there were contradictory opinions on the number of sessions that should be held for the individual counseling. Some participants indicated that having six sessions would be enough, and others thought six sessions was too much because the sessions would begin to waste the women’s time.

For the skills training component, one woman explained that having varying skillsets to learn in the workshops would be “a lot.” During discussions about the reproductive health education component, one male participant indicated that government support may be needed. Another participant mentioned the need for program continuity. He noted the importance of women maintaining ongoing relationships with providers to ensure that their questions and concerns arising from contraceptive use (e.g., intrauterine devices) are adequately addressed.

Comments surrounding the use of incentives for the individual counseling, skills training, and reproductive health education components indicated that the benefits of the programs would serve as sufficient incentive for people to attend. The perceived importance of this benefit suggests that there is no need for additional incentives to foster program feasibility. If incentives were provided, suggestions included water, small cookies or candies, small amounts of money for transportation, pills, condoms, crackers, juice, and rice.

Delivery

Delivery approaches were examined in order to understand participant perceptions of acceptable target populations for each component, component formats (i.e. group or individual sessions), logistics (i.e. timing and location), and appropriate characteristics of the delivery agents, described as Health Promoters in this study.

Target population

The suggested target populations for each component varied based on gender, age, and location characteristics. In general, for the individual counseling, support group, and skills training components, participants believed that young women should be the target population. One man stated that there were many people who need mental help after the earthquake, but women should be the main target population due to their high levels of stress. Participants also mentioned that the rural areas should be prioritized as the target population for the individual counseling and skills training workshops, rather than a city, such as Léogáne, because individuals from rural areas have higher vulnerability and less access to hospitals.

Participants believed that the target population for the reproductive health education and couples’ communication components should include individuals within the age range of 12–30 years old. Others suggested a narrower age range, believing that girls in their early teens, such as 13 or 14, should be included in the trainings because they can become pregnant at that age and females are having children earlier and earlier. One woman gave an example that when young women get pregnant, they are forced to leave school - reinforcing the usefulness of providing a support group for the younger generation. It was also mentioned that the training would be wasted on older adults because they already have families and would have no use for knowledge on family planning. A man additionally mentioned that this training would be useful because of the high incidence of rape in the community.

Format

Specific components, such as the individual counseling, skills training, and support group, have a set format (individual vs. group setting); therefore, they were not discussed in terms of format. For the reproductive health education workshop, a group setting was generally believed to be acceptable by both men and women. However, some women expressed that groups should be separated by gender, as there are certain things that are applicable solely to women or men.

In terms of the couples’ communication, many men stated that they would prefer to do the training in groups of couples. One man said that it would be like a brotherhood where they can come together and be informed. However, others disagreed, mentioning that they would be discussing personal problems and should do this privately.

Logistics

For the support group, women recommended that the sessions be held in a calm, quiet place with no children present. It was also mentioned that the reproductive health education component should be held up to three times per week with limited time between sessions to encourage knowledge retention. The couples’ communication component was suggested to be held once a week. Participants also discussed suggested days of the week when the components should be held. There was consensus that, for all components, market hours should be avoided. Some participants went further to suggest that the programs should not be held at all on market days. Others preferred weekend activities, suggesting that the sessions occur after the market on Saturday or after church on Sunday. One participant proposed holding the interventions during vacation times, when children are no longer in school.

Delivery agent

For the individual counseling, reproductive health education, and skills training interventions, a female health promoter was generally preferred by all. Women indicated that they would not accept a male health promoter. For the individual counseling intervention, participants felt that the important attributes of the health promoter be: wisdom, comprehension skills, and education; compassion; being from the local area; good character/well-respected in the community; and knowledgeable about stress. In addition, as the Fondwa community has low literacy levels, the groups believed that a health promoter who is patient and uses a variety of training methods to share ideas (e.g., visual aids, like pictures) is necessary. Women stated that the health promoter does not need to be a psychologist; however, this would not deter attendance either. Specific individuals were mentioned as potential health promoters, including young girls from the women’s group in Fondwa.

With regard to the support group, some women believed they would feel more comfortable speaking to someone they knew; however, others preferred a health promoter whom they did not know. Preferred characteristics of the support group health promoter included: good character and adequate training. It was noted that these characteristics are important because the men will not allow their wife to go if the health promoter does not have these attributes. In addition, the health promoter should express belief and trust in the group, be a good listener, and respect confidentiality.

Participants felt that the health promoters for the reproductive health education and couples’ communication components should be patient, knowledgeable, kind, assertive, non-judgmental, professional, calm, and respectful.

Adaptations

Participants suggested names for the individual counseling component that would be understandable to the general public, such as “Community Health Trainer” or “Member Advice.” There was also suggested changes to the title ‘Health Promoter,’ where the name ‘counselor’ was suggested as an alternative. Furthermore, participants indicated that these programs should be adapted to cater to the illiterate, elderly, or otherwise disadvantaged women to appropriately involve various groups of people. It was mentioned that this would involve training health promoters in a particular way that gives them knowledge of how to adapt their communication methods to the needs of varying types of women. One woman suggested using images and drawings to help the elderly learn and remember what was said.

For the support group, the researchers probed whether participants would suggest combining the support group and skill training workshop. There was disagreement regarding combining the women’s group and skills training group. Some participants believed that having two separate programs would demand too much time. However, the majority of comments suggested that it would be preferred if the programs were separate, as it would allow women to choose the program in which to participate. Women provided ideas regarding different skills that could be included in the skills training component. Some women said that they would want to have classes on flower-making, music, financial literacy, sewing, cooking, English, pastry-making, and bracelet-making.

Additionally, participants mentioned a few suggestions regarding adaptations to the couples’ communication component. One male participant believed that this should be an individual, appointment-based program to ensure that there is no discomfort associated with discussing problems in front of a group. Another male participant mentioned that separating men and women might be useful to guarantee that men and women could attend the training, even if they did not have a husband or wife, or if their husband or wife did not want to attend.

There were no adaptations suggested for the reproductive health education component.

Discussion

This study explored anticipated effectiveness, feasibility, acceptability, and necessary cultural adaptations of potential interventions to address mental health in Léogáne, Haiti. The current study proposed five culturally adapted components for interventions that address mental health directly and indirectly, through targeting problem-solving skills, social support, financial insecurity, female autonomy, and family planning methods. Findings indicate that individual counseling, support group, and skills training components were generally perceived as effective, acceptable, and feasible by both male and female FGD participants. At the same time, participants expressed doubts regarding the acceptability of the couples’ communication training and reproductive health education components. Reservations surrounding these components focused on lack of male interest, traditional male and female gender roles, lack of female autonomy, and misconceptions about family planning. Feasibility, effectiveness, and acceptability of the components appeared to be dependent on cost, proximity to participants, and inclusion of a female health promoter that is known in the community.

The results suggest that task-shifting is an appropriate strategy for these intervention components. Participants mentioned that the health promoter did not need to be a professional and listed desired characteristics that could be fulfilled by trained lay people. Additionally, given the scarcity of mental health care professionals in Haiti (Caribbean Country Management Unit 2006; World Bank 2006; WHO 2010) and the perceived inadequacy of existing biomedical treatment options for mental health disorders (Khoury et al., 2012), community member involvement as facilitators for treatment and health education dissemination may be beneficial.

Furthermore, there is evidence that task-shifting approaches lowers the cost of treatment services, which was an aspect that all participants valued with regards to component acceptability. For example, Buttorff et al., (2012) completed an economic evaluation of a task-shifting intervention for common mental disorders in India, which demonstrated that using lay workers was a cost-effective and cost-saving approach. Additionally, Petersen et al., (2011) found that task-shifting in South African primary health care reduced the number of health care providers and reduced costs. Such studies support the use of task-shifting to lower the cost of mental health interventions, increasing accessibility and capacity to fund the services. Moreover, participants indicated a necessity for the components to be located near the target population, which was frequently suggested to be rural communities, and for the inclusion of known community members as health promoters. Given the low-resource environment of the rural areas, task-shifting may provide a feasible option for services to reach the targeted population and include local community members as program facilitators. At the same time, efforts to reduce costs by relying on “volunteer” community health workers have raised debates in global health, wherein some of the most burdened providers of care are often not remunerated (Maes et al., 2010; Maes et al., 2015).

There was disagreement among participants about how traditional gender roles and cultural norms may interface with the interventions, influencing their effectiveness. With regard to the couples’ communication training, female FGD participants noted that men would refuse to participate due to their hesitation to perform household tasks. Although these gender roles are deeply rooted -- wherein women are primarily responsible for household tasks and men predominantly contribute to the workforce and financially provide for the family (Coreil 1983a; De Zaldoundo and Barnard 1995) -- there is some evidence that there is flexibility regarding these roles (Mensa-Kwao et al., in review). Furthermore, decision-making is often dominated by men, which can have implications for reproductive health outcomes and treatment-seeking for women (Sternberg and Hubley 2004). Therefore, although there is doubt regarding acceptability due to male non-engagement, this male involvement might be necessary to optimally impact female mental health.

Studies have examined the impact of incorporating men into interventions targeting reproductive health and female empowerment. Doyle et al., (2018) examined the impact of a couples’ intervention on behavioral and health-related outcomes in Rwanda. In this intervention, community volunteers engaged men and couples in group discussions that focused on topics like gender and power, fatherhood, and couple communication and decision-making. The study found that women in the intervention used contraceptives to a greater degree than the control group, and men had greater participation in household and child care tasks, as well as decreased dominance in decision-making. This suggests that incorporating men in such programs can be effective if done in an appropriate manner and should be further examined and adapted for the Haitian context.

Additionally, program sustainability, particularly regarding the reproductive health education and support group components, appeared to be a concern for participants. Reproductive health interventions have been implemented at various times in Haiti; however, these programs are often short-lived and inconsistent in their service delivery due their lack of institutionalization through a formal Haitian network or system of governance (Maternowska 2006). In addition, many international NGOs without a vested interest in the community implement programs which fail to adequately consider the community needs and norms (Maternowska 2006). Such concerns were raised by participants, who felt that these attempted interventions created confusion and discomfort for women who were introduced to family planning methods by an NGO with which they eventually lost contact. This type of inconsistency left women with no outlet to receive follow-up services regarding side effects or removal of current methods, resulting in concerns about using contraceptive methods in the future. Efforts should focus on addressing these concerns, for example by involving local community members as program leaders to improve appropriateness for the community and trust in the program.

Participants also mentioned concerns about the development of support groups in Léogáne due to their knowledge that past attempts were unsuccessful. Despite concerns with support group sustainability in the Léogáne area, the city has a history of growth of women’s groups during the time of President Aristide; however, the women’s group leader’s death during the 2010 earthquake led to the disintegration of women’s groups in the area. This historical period of successful support groups suggests that such groups may be sustainable if devoted group leaders are involved in the process. Group participation and sustainability, nonetheless, may still be impacted by discomfort with sharing personal information in a group setting.

Limitations

The presence of American researchers in the focus group discussions may have created social desirability bias. This was clearly evidenced during one FGD where participants appeared to have polarizing views that either supported traditional Haitian gender roles or more autonomous positions in their relationships. Those who promoted autonomy within relationships attempted to engage with the researchers to seek approval of their views. Additionally, FGD participants were recruited through convenience sampling, which poses a risk of sampling bias, for example potentially excluding community members with formal employment.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrates that there is a high degree of expected acceptability, feasibility, and usefulness for addressing mental health of women through interventions focused on problem-solving skills, social support, financial insecurity, female autonomy, and family planning methods. Given the lack of research on intervention approaches in Haiti, particularly those targeting mental health, this study provides a foundation for developing prevention and treatment approaches for mental distress among Haitian women. It also contributes to literature on rigorous adaptation processes for introducing evidence-based interventions into new settings.

Funding:

This study was funded by grants from the Duke Global Health Institute and Emory Global Health Institute. Dr. Kaiser was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (F32MH113288).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Caroline Zubieta, Duke University.

Alex Lichtl, Duke University.

Karen Trautman, Duke University.

Stefka Mentor, Duke University.

Diana Cagliero, Emory University.

Augustina Mensa-Kwao, Emory University.

Olivia Paige, Emory University.

Schatzi McCarthy, Department of Research, Family Health Ministries.

David Walmer, Atlantic Reproductive Medicine, Duke Global Health Institute, Duke University.

Bonnie N. Kaiser, Duke Global Health Institute, Duke University, Department of Anthropology, University of California San Diego.

References

- Anoop S, Saravanan B, Joseph A, Cherian A, and Jacob KS. 2004. “Maternal Depression and Low Maternal Intelligence as Risk Factors for Malnutrition in Children: A community Based Casecontrol Study from South India.” Archives of Disease in Childhood 89 (4): 325–29. Doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.009738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett ML, Gonzalez A, Miranda J, Chavira DA, & Lau AS (2018). Mobilizing community health workers to address mental health disparities for underserved populations: A systematic review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(2), 195–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkin Gary S., Unutzer Jurgen, Kessler Ronald C., Verdeli Helen, Raviola Giuseppe J., Sachs Katherine, Oswald Catherine, et al. , 2011. “Scaling Up for the “Bottom Billion”: “5×5” Implementation of Community Mental Health Care in Low-Income Regions.” Psychiatric Services 62 (12): 1494–502. Doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.000012011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau Nicole, Kessler Ronald C., Chilcoat Howard D., Schultz Lonnie R., Davis Glenn C., and Andreski Patricia. 1998. “Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Community.” Archives of General Psychiatry 55 (7): 626–32. Doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant Richard A., Schafer Alison, Dawson Katie S., Anjuri Dorothy, Mulili Caroline, Ndogone Lincoln, Koyiet Phiona, et al. ,. 2017. “Effectiveness of a Brief Behavioural Intervention on Psychological Distress among Women with a History of Gender-based Violence in Urban Kenya: A Randomised Clinical Trial. PLOS Medicine 14 (8). Doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttorff Christine, Hock Rebecca S., Weiss Helen A., Naik Smita, Araya Ricardo, Kirkwood Betty R., Chrisholm Daniel, et al. , 2012. “Economic evaluation of a task-shifting intervention for common mental disorders in India.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90(11): 813–821. doi: [ 10.2471/BLT.12.104133] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caribbean Country Management Unit. 2006. Social Resilience and State Fragility in Haiti: A Country Social Analysis. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Carrazana Enrique, DeToledo John C., Tatum William, Rivas-Vasquez Rafael, Rey Gustavo J., and Wheeler Steve. 1999. “Epilepsy and Religious Experiences: Voodoo Possession.” Epilepsia 40(2): 239–241. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb02081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casterline John B., and Sinding Steven W.. 2000. “Unmet Need for Family Planning in Developing Countries and Implications for Population Policy.” Population and Development Review 26 (4): 691–723. Doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2000.00691.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cerda Magdalena, Paczkowski Magdalena, Galea Sandro, Memethy Kevin, Péan Claude, and Desvarieux Moïse. 2012. “Psychopathology in the Aftermath of the Haiti Earthquake: A Population-Based Study of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Major Depression.” Depression and Anxiety 30 (5): 413–24. doi: 10.1002/da.22007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney Edward, Goodwin Guy M., and Fazel Seena. 2014. “Risks of All-cause and Suicide Mortality in Mental Disorders: A Meta-review.” World Psychiatry 13 (2): 153–60. doi. 10.1002/wps.20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibanda D, Bowers T, Verhey R, Rusakaniko S, Abas M, Weiss HA, & Araya R (2015). The Friendship Bench programme: a cluster randomised controlled trial of a brief psychological intervention for common mental disorders delivered by lay health workers in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 9(1), 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm Dan, Sweeny Kim, Sheehan Peter, Rasmussen Bruce, Smit Filip, Cuijpers Pim, and Saxena Skekhar. 2016. “Scaling-up of Treatment of Depression and Anxiety: A Global Return on Investment Analysis.” The Lancet Psychiatry 3(7): 415–24. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30131-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary Neerja, Sikander Siham, Atif Najia, Singh Neha, Ahmad Ikhlaq, Fuhr Daniela C., Rahman Atif, et al. , 2014. “The Content and Delivery of Psychological Interventions for Perinatal Depression by Non-specialist Health Workers in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 28(1): 113–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins Pamela Y., Patel Vikram, Joestl Sarah S., March Dana, Insel Thomas R., Daar Abdallah S., Bordin Isabel A, et al. , 2011. “Grand challenges in global mental health.” Nature 475: 27–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coreil Jeannine. 1983. “Allocation of Family Resources for Health Care in Rural Haiti.” Social Science & Medicine 17 (11): 709–19. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson Katie S., Bryant Richard A., Harper Melissa, Alvin Kuowei Tay Atif Rahman, Schafer Alison, and Van Ommeren Mark. 2015. “Problem Management Plus (PM+): A WHO Transdiagnostic Psychological Intervention for Common Mental Health Problems.” World Psychiatry 14 (3): 354–57. doi: 10.1002/wps.20255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara De Zalduondo, and Bernard Jean Maxius. 1996. “Meaning and consequences of sexual-economic exchange” In Conceiving Sexuality, edited by Richard Parker and John Gagnon. Boston: Routledge Kegan Paul [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers Astrid, and Fleurose Sheila St. 2002. “Treating Haitian Patients: Key Cultural Aspects.” American Journal of Psychotherapy 56 (4): 508–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2002.56.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle Kate, Levtov Ruti G., Barker Gary, Bastian Gautam G., Bingenheimer Jeffrey B., Kazimbaya Shamsi, Nzabonimpa Anicet, et al. , 2018. “Gender-transformative Bandebereho Couples’ Intervention to Promote Male Engagement in Reproductive and Maternal Health and Violence Prevention in Rwanda: Findings from a Randomized Controlled Trial.” Plos One 13 (4). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton Julian, Layla McCay Maya Semrau, Chatterjee Sudipto, Baingana Florence, Araya Ricardo, Ntulo Christina, et al. , 2011. “Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries.” The Lancet 378(9802): 1592–1603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60891-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard MO, Steven Baldridge, Justin Marshall, Walter Mooney, and Rix GJ 2010. “The MW 7.0 Haiti earthquake of January 12, 2010.” USGS/EERI Advance Reconnaissance Team report. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2010–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Faisal-Cury A, Tedesco JJA, Kahhale S, Menezes PR, and Zugaib M. 2004. “Postpartum Depression: In Relation to Life Events and Patterns of Coping.” Archives of Womens Mental Health 7 (2): 123–31. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer Paul. 1992. “The birth of the Klinik: A cultural history of Haitian professional psychiatry.” In Ethnopsychiatry: The Cultural Construction of Professional and Folk Psychiatries, edited by Gaines Atwood D., 251–272. Albany: SUNY. [Google Scholar]

- Fawzi Mary C. Smith, Eustache Eddy, Oswald Catherine, Surkan Pamela, Louis Ermaze, Scanlan Fiona, Wong Richard, et al. , 2010. “Psychosocial Functioning Among HIV-Affected Youth and Their Caregivers in Haiti: Implications for Family-Focused Service Provision in High HIV Burden Settings.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 24 (3): 147–58. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fils-Aimé J. Reginald, Grelotti David J., Thérosmé Tatiana, Kaiser Bonnie N., Raviola Giuseppe, Alcindor Yoldie, Severe Jennifer, et al. , 2018. “A Mobile Clinic Approach to the Delivery of Community-based Mental Health Services in Rural Haiti.” Plos One 13 (6). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher Jane, de Mello Meena Cabral, Patel Vikram, Rahman Atif, Tran Trach, Holton Sara, and Holmes Wendy. 2012. “Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90(2): 139–149. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.0918506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton Brent D., Scheffler Richard M., Sparkes Susan P., Erica Yoonkyung Auh Marko Vujicic, and Soucat Agnes. 2011. “Health Workforce Skill Mix and Task Shifting in Low Income Countries: A Review of Recent Evidence.” Human Resources for Health 9 (1). doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea Sandro, Nandi Arijit, and Vlahov David. 2005. “The Epidemiology of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder after Disasters.” Epidemiologic Reviews 27 (1): 78–91. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxi003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson Jessica D., Koenig Michael A., and Hindin Michelle J.. 2008. “The Effects of Unintended Pregnancy on Infant, Child, and Parental Health: A Review of the Literature.” Studies in Family Planning 39 (1): 18–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldmann Emily, and Galeo Sandro. 2014. “Mental health consequences of disasters.” Annual review of public health 35: 169–183. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Haiti (GOH). 2010. Action Plan for National Recovery and Development of Haiti. Port-au-Prince: GOH. [Google Scholar]

- Grelotti David J. 2013. “Even More Mountains: Challenges to Implementing Mental Health Services in Resource-Limited Settings.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 52 (4): 339–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grelotti David J., Lee Amy C., Joseph Reginald Fils-Aime Jacques Solon Jean, Therosme Tatiana, Handy Petit-Homme Catherine M. Oswald, et al. , 2015. “A pilot initiative to deliver community-based psychiatric services in rural Haiti after the 2010 earthquake.” Annals of global health 81(5): 718–724. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2015.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpham Trudy, Huttly Sharron, De Silva Mary J., and Abramsky Tanya. 2005. “Maternal Mental Health and Child Nutritional Status in Four Developing Countries.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 59 (12): 1060–064. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James Erica C. 2008. “Haunting ghosts: Madness, Gender, and Ensekirite in Haiti in the Democratic era” In Postcolonial Disorders, edited by Mary-Jo DelVecchio Good, Sandra Teresa Hyde and Sarah Pinto, 133–155. London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- James Erica C. 2010. Democratic insecurities: Violence, trauma, and intervention in Haiti. Los Angeles: Univ of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Bonnie N., Mclean Kristen E., Kohrt Brandon A., Hagaman Ashley K., Wagenaar Bradley H., Khoury Nayla M., and Keys Hunter M.. 2014. “Reflechi Twòp—Thinking Too Much: Description of a Cultural Syndrome in Haiti’s Central Plateau.” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 38 (3): 448–72. doi: 10.1007/s11013-014-9380-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuma Ritsuko, Minas Harry, Van Ginneken Nadja, Dal Poz Mario R, Desiraju Keshav, Morris Jodi E., Saxena Shekhar, et al. ,. 2011. “Human Resources for Mental Health Care: Current Situation and Strategies for Action.” The Lancet 378 (9803): 1654–663. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys Hunter M., Kaiser Bonnie N., Kohrt Brandon A., Khoury Nayla M., and Brewster Aimée-Rika T.. 2012. “Idioms of Distress, Ethnopsychology, and the Clinical Encounter in Haitis Central Plateau.” Social Science & Medicine 75 (3): 555–64. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MN, Hamdani SU, Chiumento A, Dawson K, Bryant RA, Sijbrandij M, Nazir H, et al. ,. 2017. “Evaluating Feasibility and Acceptability of a Group WHO Trans-diagnostic Intervention for Women with Common Mental Disorders in Rural Pakistan: A Cluster Randomised Controlled Feasibility Trial.” Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 1-11. doi: 10.1017/s2045796017000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury Nayla M., Kaiser Bonnie N., Keys Hunter M., Brewster Aimee-Rika T., and Kohrt Brandon A.. 2012. “Explanatory Models and Mental Health Treatment: Is Vodou an Obstacle to Psychiatric Treatment in Rural Haiti?” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 36 (3): 514–34. doi: 10.1007/s11013-012-9270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer Laurence J. 2002. “Psychopharmacology in a Globalizing World: The Use of Antidepressants in Japan.” Transcultural Psychiatry 39 (3): 295–322. doi: 10.1177/136346150203900302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt Brandon A., and Hruschka Daniel J.. 2010. “Nepali Concepts of Psychological Trauma: The Role of Idioms of Distress, Ethnopsychology and Ethnophysiology in Alleviating Suffering and Preventing Stigma.” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 34 (2): 322–52. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9170-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe Athena R., and Hutson Royce A.. 2006. “Human Rights Abuse and Other Criminal Violations in Port-au-Prince, Haiti: A Random Survey of Households.” The Lancet 368 (9528): 864–73. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie Carmen H., Daniel Carolann, Newman Peter A., Weaver James, and Loutfy Mona R.. 2014. “A Psycho-Educational HIV/STI Prevention Intervention for Internally Displaced Women in Leogane, Haiti: Results from a Non-Randomized Cohort Pilot Study.” PLoS ONE 9 (2). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh HM. Peer-informed learning on increasing contraceptive knowledge among women in rural Haiti. 2015. (Order No. 1606112). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I. (1755920279)

- Lopez Alan D., and Murray Christopher C.J.L. 1998. “The global burden of disease, 1990–2020.” Nature Medicine 4: 1241–43. 10.1038/3218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes Kenneth C., Kohrt Brandon A., and Closser Svea. 2010. “Culture, status and context in community health worker pay: pitfalls and opportunities for policy research. A commentary on Glenton et al.,(2010).” Social Science & Medicine 71(8), 1375–1378. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes Kenneth C., Closser Svea, Vorel Ethan, and Tesfaye Yihenew A.. 2015. “Using community health workers: Discipline and Heirarchy in Ethiopia’s Women’s Development Army.” Annals of Anthropological Practice 39(1), 42–57. doi: 10.1111/napa.12064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martsolf Donna S. 2004. “Childhood Maltreatment and Mental and Physical Health in Haitian Adults.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 36 (4): 293–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catherine Maternowska, M.. 2006. Reproducing inequities: Poverty and the politics of population in Haiti. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mensa-Kwao Augustina. 2018. “Exploring Stress among Women in Léogâne, Haiti: An Application of the Theory of Gender and Power.” Master’s thesis, Emory University [Google Scholar]

- Miller Nikki Levy. 2000. “Haitian Ethnomedical Systems and Biomedical Practitioners: Directions for Clinicians.” Journal of Transcultural Nursing 11 (3): 204–11. doi: 10.1177/104365960001100307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria Yuval, Nandi Vijay, and Galea Sandro. 2007. “Post-traumatic Stress Disorder following Disasters: A Systematic Review.” Psychological Medicine 38 (4): 467–80. doi: 10.1017/s0033291707001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nhiwatiwa Sekai M., Patel Vikram, and Acuda Wilson. 1998. “Predicting Postnatal Mental Disorder with a Screening Questionnaire: A Prospective Cohort Study from Zimbabwe.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 52 (4): 262–66. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.4.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichter Mark. 1981. “Idioms of Distress: Alternatives in the Expression of Psychosocial Distress: A Case Study from South India.” Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 5 (4): 379–408. doi: 10.1007/bf00054782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas Guerda, Jean-Jacques Ronald, and Wheatly Anna. 2012. “Mental health counseling in Haiti: Historical overview, current status, and plans for the future”. Journal of Black Psychology 38(4), 509–519. doi: 10.1177/0095798412443162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nyatsanza Memory, Schneider Marguerite, Davies Thandi, and Lund Crick. 2016. “Filling the Treatment Gap: Developing a Task Sharing Counselling Intervention for Perinatal Depression in Khayelitsha, South Africa.” BMC Psychiatry 16 (1): 164. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0873-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. 2011. “Earthquake in Haiti–One Year Later” PAHO/ WHO Report on the Health Situation. Washington, DC: PAHO/WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Patel Vikram, and Kleinman Arthur. 2003. “Poverty and Common Mental Disorders in Developing Countries.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81: 609–15. doi: 10.1037/e538812013-019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel Vikram, Kirkwood Betty R., Pednekar Sulochana, Pereira Bernadette, Barros Preetam, Fernandes Janice, Datta Jane, et al. ,. 2006. “Gender Disadvantage and Reproductive Health Risk Factors for Common Mental Disorders in Women.” Archives of General Psychiatry 63(4): 404–13. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen Inge, Bhana Arvin, Baillie Kevin, and the Mental Health and Poverty Research Programme Consortium. 2011. “The Feasibility of Adapted Group-Based Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) for the Treatment of Depression by Community Health Workers Within the Context of Task Shifting in South Africa.” Community Mental Health Journal 48(3): 336–41. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9429-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen Inge, Lund Crick, Bhana Arvin, Flisher Alan J., and the Mental Health and Poverty Research Programme Consortium. 2011. “A task shifting approach to primary mental health care for adults in South Africa: human resource requirements and costs for rural settings.” Health policy and planning, 27(1): 42–51. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atif Rahman, Iqbal Zafar, and Harrington Richard. 2003. “Life events, social support and depression in childbirth: perspectives from a rural community in the developing world.” Psychological Medicine 33(7): 1161–167. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Hamdani SU, Awan NR, Bryant RA, Dawson KS, Khan MF, … & Sijbrandij M (2016). Effect of a multicomponent behavioral intervention in adults impaired by psychological distress in a conflict-affected area of Pakistan: a randomized clinical trial. Jama, 316(24), 2609–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Atif, Fisher Jane, Bower Peter, Luchters Stanley, Tran Thach, Yasamy M. Taghi, Saxena Shekhar, and et al. ,. 2013. “Interventions for Common Perinatal Mental Disorders in Women in Low- and Middle-income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91(8): 593–601. doi: 10.2471/blt.12.109819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Atif, Iqbal Zafar, Bunn James, Lovel Hermione, & Harrington Richard. 2004. “Impact of maternal depression on infant nutritional status and illness: a cohort study.” Archives of general psychiatry 61(9): 946–952. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes J, Tukiainen E, Partovi S, & Sridhar A 2017. Factors Influencing Contraception Use in Rural Haiti Women: A Mixed-Methods Pilot Study [8A]. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 129(5), 10S–11S. [Google Scholar]

- Safran Marc A., Chorba Terence, Schreiber W. Merritt, Archer Roodly, and Cookson Susan T.. 2011. “Evaluating Mental Health after the 2010 Haitian Earthquake.” Disaster Medicine & Public Health Preparedness 5(2): 154–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Lora Antonio, Morris Jodi, Berrino Annamaria, Esparza Patricia, Barrett Thomas, Ommeren Mark van, et al. ,. 2011. “Mental Health services in 42 low- and middle-income countries: a WHO-AIMS cross-national analysis.” Psychiatric Services 62(2):123–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott Kate M., Lim Carmen, Ali Al-Hamzawi Jordi Alonso, Bruffaerts Ronny, José Miguel Caldas-De-Almeida Silvia Florescu, et al. ,. 2016. “Association of Mental Disorders with Subsequent Chronic Physical Conditions.” JAMA Psychiatry 73(2): 150–58. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgh Gilda, Ashford Lori S., and Hussain Rubina. 2016. Unmet need for contraception in developing countries: Examine women’s reasons for not using a method. New York, NY: The Guttmacher Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Singh RJ, & Barton-Dock M (2015). Haiti: Toward a New Narrative. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Singla DR, Kohrt BA, Murray LK, Anand A, Chorpita BF, & Patel V (2017). Psychological treatments for the world: lessons from low-and middle-income countries. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 149–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterlin Carlo. 2006. “Pour une approche interculturelle du concept de sante.” Ruptures,revue transdisciplinaire en sante 11(1): 112–12 [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg Peter, and Hubley John. 2004. “Evaluating Men’s Involvement as a Strategy in Sexual and Reproductive Health Promotion.” Health Promotion International 19 (3): 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trangsrud R 1998. “Adolescent Reproductive Health in East and Southern Africa: Building Experience, Four Case Studies” Regional Adolescent Reproductive Health Network, USAID, REDSO/ESA. Nairobi, Kenay: Family Care International. [Google Scholar]

- Tyano Sam, Keren Miri, Herrman Helen, and Cox John. 2010. Parenthood and mental health: A bridge between infant and adult psychiatry. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Statistics Division. 2010. “Millennium Development Goals Indicators.” Accessed January 21, 2018. http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Data.aspx.

- United States Agency for International Development. 2017. Haiti Health Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: USAID. [Google Scholar]