Abstract

Metabolic reprogramming is associated with the adaptation of host cells to the disease environment, such as inflammation and cancer. However, little is known about microbial metabolic reprogramming or the role it plays in regulating the fitness of commensal and pathogenic bacteria in the gut. Here, we report that intestinal inflammation reprograms the metabolic pathways of Enterobacteriaceae, such as Escherichia coli LF82, in the gut to adapt to the inflammatory environment. We found that E. coli LF82 shifts its metabolism to catabolize L-serine in the inflamed gut in order to maximize its growth potential. However, L-serine catabolism has a minimal effect on its fitness in the healthy gut. In fact, the absence of genes involved in L-serine utilization reduces the competitive fitness of E. coli LF82 and Citrobacter rodentium only during inflammation. The concentration of luminal L-serine is largely dependent on dietary intake. Accordingly, withholding amino acids from the diet markedly reduces their availability in the gut lumen. Hence, inflammation-induced blooms of E. coli LF82 are significantly blunted when amino acids, particularly L-serine, are removed from the diet. Thus, the ability to catabolize L-serine increases bacterial fitness and provides Enterobacteriaceae with a growth advantage against their competitors in the inflamed gut.

Microbial metabolism plays a fundamental role shaping the ecology of the microbial communities 1, 2. Intestinal inflammation leads to a microenvironment that is conducive to the growth of Enterobacteriaceae allowing them to outcompete obligate anaerobes 3, 4. Therefore, enterobacterial blooms, such as those seen in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) 5, are a hallmark of inflammation-associated dysbiosis. However, the microbial metabolic landscape associated with gut dysbiosis remains largely unexplored. Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC), a pathotype of E. coli, is often isolated from the intestinal mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), one of two major forms of IBD 6. AIEC colonization can cause massive intestinal inflammation in certain genetically engineered mice and can worsen inflammation in chemical- or pathogen-induced models of colitis 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. Given the accumulation of AIEC in CD patients, it is conceivable that AIEC employs unique metabolic pathways to adapt to disease-associated microenvironments.

Here, we report that intestinal inflammation causes AIEC to reprogram their metabolism. AIEC relies on amino acids, particularly L-serine, for its growth in the inflamed gut, while L-serine metabolism plays a minimal role in the fitness in the healthy gut. Some, most likely pathogenic, strains of Enterobacteriaceae employ the ability to catabolize L-serine to gain a fitness advantage over competing strains that are unable to utilize L-serine. Luminal L-serine used by pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae is primarily supplied by the diet. Therefore, restriction of dietary L-serine could prevent pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae from blooming in the inflamed gut.

Results

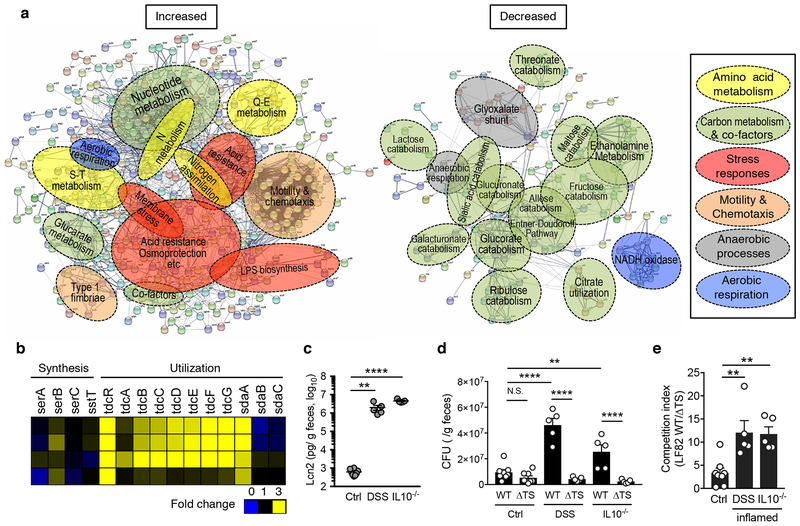

We first examined the impact of host disease on microbial metabolism in E. coli. A CD-associated AIEC strain LF82 6 was used to mono-colonize germ-free (GF) mice and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) was administrated to induced colitis. Genes related to catabolism of simple sugars, primary metabolic pathways utilized by E. coli for its growth under normal intestinal conditions 12, were significantly down-regulated during inflammation (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). Instead, genes associated with amino acid metabolism were markedly up-regulated in the inflamed gut (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). Among them, we found that L-serine utilization, such as tdcR, tdcABCDEFG, were strongly up-regulated in the inflamed gut (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1a, b, and Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, genes related to L-serine biosynthesis were not up-regulated (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). To investigate the importance of L-serine catabolism for the adaptation of E. coli to the inflamed gut, we generated isogenic mutant LF82 strains that lack the tdc operon (whole deletion of tdcABCDEFG genes; Δtdc), sdaBC genes (Δsda), and a strain that lacks both the tdc and sda genes (ΔtdcΔsda). LF82ΔtdcΔsda double mutant (ΔTS) showed a significant growth defect in L-serine-supplemented medium, while single mutant strains did not, indicating the products encoded by these genes are functionally redundant (Extended Data Fig. 1c, d). No growth defect was observed when the mutant strains were grown in DMEM medium (Extended Data Fig. 1c, d). Likewise, LF82ΔtdcΔsda double mutant did not reveal any growth defect in luminal contents isolated from healthy SPF mice (Extended Data Fig. 1c, d). To examine the role L-serine catabolism plays in the inflamed gut, we co-infected naïve (Ctrl) and colitic mice, both DSS-treated C57BL/6 mice and IL-10−/− mice, with LF82 WT and the ΔtdcΔsda double mutant. The presence of colitis was verified by measuring fecal lipocalin-2 (Lcn2) levels 13 (Fig. 1c). In Ctrl mice, no significant difference was observed in the colonization potential of both strains (Fig. 1d, e). In contrast, inflammation favored the expansion of WT LF82, but not the mutant (Fig. 1d, e). Likewise, loss of Tdc and Sda did not interfere with the respiration of nitrate, a by-product of host inflammatory responses that foster blooms of E. coli 3 (Extended Data Fig. 2a). These data indicate that E. coli LF82 employs L-serine catabolism to adapt to the inflammatory milieu.

Figure 1. E. coli reprograms its metabolism and utilizes serine in the inflamed gut.

(a) Germ-free (GF) mice were mono-colonized with E. coli LF82 for 1 week. E. coli mono-colonized mice were then treated with 1.5% DSS for 5 days. Cecal contents were harvested and microbial gene expression was analyzed by RNA-seq (N=4, biologically independent animals). A network analysis of bacterial genes up- (Left) and down-regulated (Right) in the inflamed gut (≥ 2.0-fold change) using the STRING protein–protein interaction database. The functional gene annotation was obtained from DAVID. Networks were exported with confidence view settings in which line thickness indicates the strength of data support. Each node (small circle) represents a gene up- or down-regulated in this analysis. The formed gene clusters were differentially colored with functional definitions as described in the box and shown as overlaid circles. (b) Fold increase (DSS/no DSS) of serine metabolism pathway genes. (c, d) Naïve SPF C57BL/6 mice (Control), DSS treated mice (day 5 post 3.0% DSS treatment), and colitis-developed Il10−/− mice were co-inoculated with LF82 WT and ΔtdcΔsda (ΔTS) mutant (1 x 109 CFU each/mouse, N=5-8, biologically independent animals). Fecal samples were collected 24 hrs post inoculation. (c) Presence of active inflammation was verified by measuring fecal Lcn2 levels. Dots indicate individual mice with mean ± s.e.m. (d) Bacterial CFUs for each strain were measured by plating. Dots indicate individual mice with geometric mean ± s.d. (e) The competitive index of WT/ΔTS mutant is shown. Dots indicate individual mice with geometric mean ± s.d. N.S.; not significant, **; P < 0.01, ***; P< 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 by 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test.

Bacteria sense their surroundings and reprogram their metabolic pathways in order to better adapt to environmental changes. In this regard, intestinal inflammation is marked by a decline in the abundance of obligate anaerobes. Since obligate anaerobes are the major fiber-degrading constituents of the microbiota, their scarcity likely translates into lower availability of mono-saccharides, which are primarily generated by microbial fermentation of non-digestible dietary carbohydrates 14. The lower availability of simple sugars may affect the expression of genes related to the metabolism of these substrates and promote the expression of metabolism of alternate nutritional sources, such as amino acids. Consistent with this notion, glucose-limitation triggered the expression of tdcA, the master regulator of the tdc operon, in LF82 (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Also, oxygen availability is thought to increase in the inflamed gut 15, 16. Compared to 0% O2, which represents the oxygen concentration in the healthy gut lumen, 2.0 % O2, which corresponds to oxygen concentration at the intestinal tissue 16, promoted the expression of tdcA (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Moreover, exposure to nitric oxide 17 resulted in the up-regulation of tdcA mRNA (Extended Data Fig. 2b). In addition, the inflammation-induced growth advantage of WT LF82 over ΔtdcΔsda LF82 was diminished in colitic Cybb−/− mice whose neutrophils/macrophages are deficient in NADPH oxidase (Extended Data Fig. 2c, d). Since WT and Cybb−/− mice developed a similar degree of colitis, hydrogen peroxide produced by the host may play a role in the regulation of L-serine catabolism in AIEC.

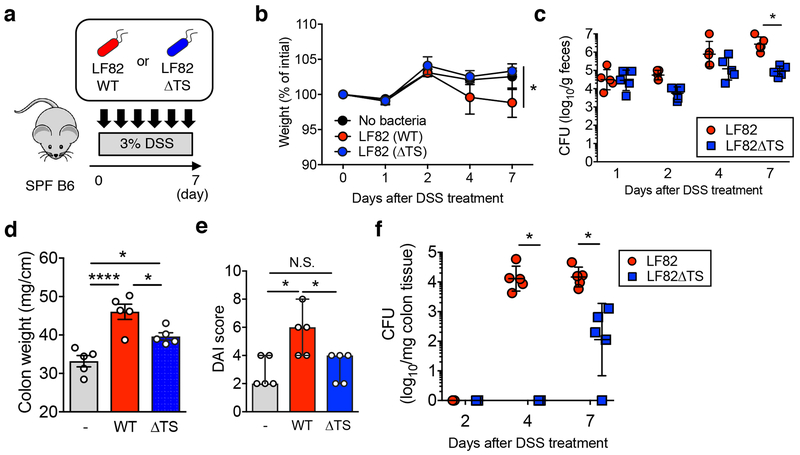

Next, we assessed the importance of L-serine metabolism in the pathogenesis of E. coli-driven colitis. To this end, DSS-colitis mice were colonized by either WT or the ΔtdcΔsda LF82 (Fig. 2a). Mice inoculated with LF82 WT lost slightly more body weight compared to control mice or LF82ΔtdcΔsda colonized mice (Fig. 2b). The luminal burden of WT and mutant LF82 was comparable before the onset of colitis (day 1) (Fig. 2c). The mutant’s colonization ability was slightly impaired in the early phase of colitis (day 2 and 4) (Fig. 2c). As colitis progressed (day 7), the luminal burden of the mutant strain was significantly lower than WT (Fig. 2c). Correlating with luminal bacterial burden, colonization by WT LF82 exacerbated colitis (as measured by thickening of the colon and DAI) while colonization by LF82ΔtdcΔsda did not increase the severity of colitis (Fig. 2d, e). Similarly, there was no difference between WT and mutant LF82 in attachment to the colonic mucosa before the onset of severe colitis (day 2) (Fig. 2f). Mucosal attachment of WT LF82 became evident on day 4. In contrast, mucosal attachment of the mutant strain was significantly impaired (Fig. 2f). Since the loss of L-serine utilization genes did not affect the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines or epithelial adhesion/invasion by LF82 (Extended Data Fig. 3), reduced inflammation results from reduced colonization due to impaired fitness of the mutant in the inflamed intestine.

Figure 2. L-serine catabolism promotes the fitness of AIEC in the inflamed gut.

(a) SPF C57BL/6 mice were treated with 3.0% DSS for 7 days (N=5, biologically independent animals).Mice were inoculated with LF82 WT or ΔtdcΔsda (ΔTS) double mutant (1 x 109 CFU each/mouse) every day. (b) Body weight changes. Data represent individual mice with mean ± s.e.m.. (c) Fecal bacterial CFUs. CFUs of Individual mice are shown as dots with geometric mean ± s.d.. (b, c) The statistical comparison between LF82 WT and ΔTS group has been made and considered significant only at Day 7. *; P < 0.05 by 2-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. (d, e) On day 7 post DSS, all mice are sacrificed and colonic weight (d) and disease activity index (DAI, e) were examined. Dots indicate individual mice with mean ± s.e.m. N.S.; not significant, *; P < 0.05, ****; P < 0.0001 by or 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. (f) The colonic tissues were harvested on indicated days following DSS treatment. Colonic mucosa-associated bacterial CFUs were assessed. CFUs from individual mice are shown as dots with geometric mean ± s.d.. *; P < 0.05 by 2-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test.

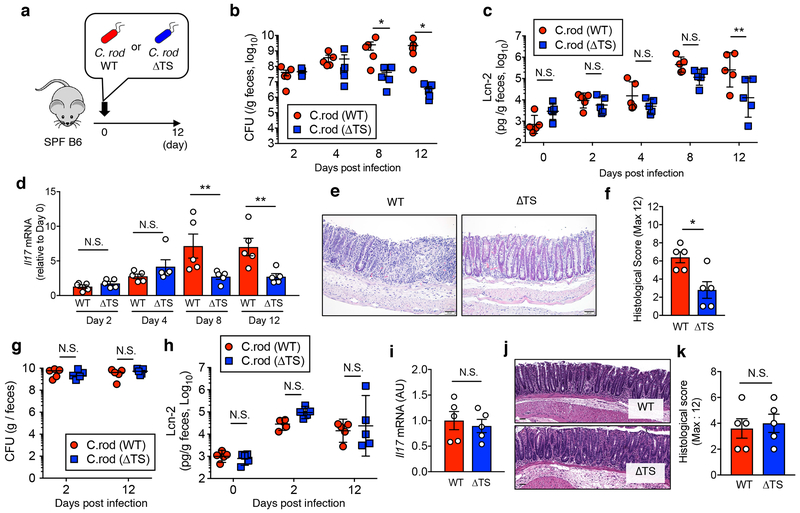

Next, we sought to determine whether L-serine utilization is a conserved mechanism used by Enterobacteriaceae to thrive in the inflamed gut. For this, we used Citrobacter rodentium, a murine model of human pathogenic E. coli infection18. SPF mice were infected with WT C. rodentium or the C. rodentium ΔtdcΔsda double mutant (Fig. 3a). WT C. rodentium was detected on day 2 and peaked on day 8 post infection (Fig. 3b). The colonization ability of the ΔtdcΔsda double mutant was comparable to the WT on days 2 and 4 post-infection (before onset of severe colitis). However, starting on day 8, the colonization ability of the ΔtdcΔsda double mutant was significantly impaired (Fig. 3b). Consequently, the severity of colitis (fecal Lcn2, mucosal IL-17A expression, histology) caused by the mutant was markedly reduced (Fig. 3c–f). Interestingly, in the absence of competing commensal microbiota (in GF mice), both WT and the ΔtdcΔsda C. rodentium colonized with equal efficiency and induced similar levels of inflammation (Fig. 3g–k). These results indicate that L-serine catabolism makes it possible for C. rodentium to gain a growth advantage over competing commensals.

Figure 3. L-serine catabolism promotes the fitness of C. rodentium in the inflamed gut.

(a) SPF C57BL/6 mice were infected orally with 1 x 109 CFU of WT or ΔtdcΔsda (ΔTS) double mutant C. rodentium (N=5, biologically independent animals). (b, c, d) Pathogen burden in feces, fecal Lcn2 levels, and Il17a mRNA expression in the colonic mucosa were monitored over the indicated time. Dots indicate individual mice with geometric mean ± s.d. (b) or mean ± s.e.m. (c, d). (e, f) Mice were sacrificed on day 12 and inflammation was assessed by histological evaluation. Representative H&E images (scale bar = 100 μm) (e) and histological score (f) are shown. Dots indicate individual mice with mean ± s.e.m.. (g) Germ-free (GF) C57BL/6 mice were mono-colonized with C. rodentium WT or C. rodentium ΔTS (1 x 109 CFU each/mouse) for 12 days. Fecal CFUs and Lcn2 level at indicated time points were analyzed. Dots indicate individual mice with geometric mean ± s.d. (g) or mean ± s.e.m. (h). (i, j, k) Mice were sacrificed on day 12. The expression of Il17a mRNA in the colonic mucosa (i), representative images of colon tissues (j) and histological score (k) were assessed. Dots indicate individual mice with mean ± s.e.m. N.S.; not significant, *; P < 0.05, **; P < 0.01 by 2-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test (b, c, d, g, h) or Man-Whitney U test (two-sided) (f, i, k).

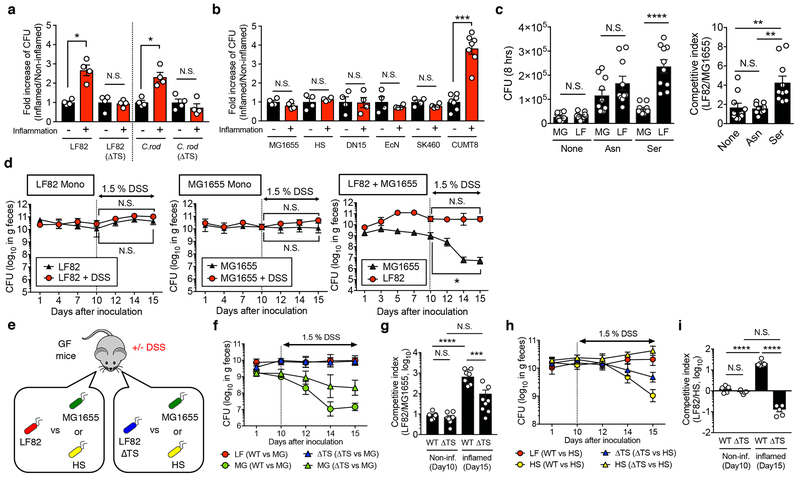

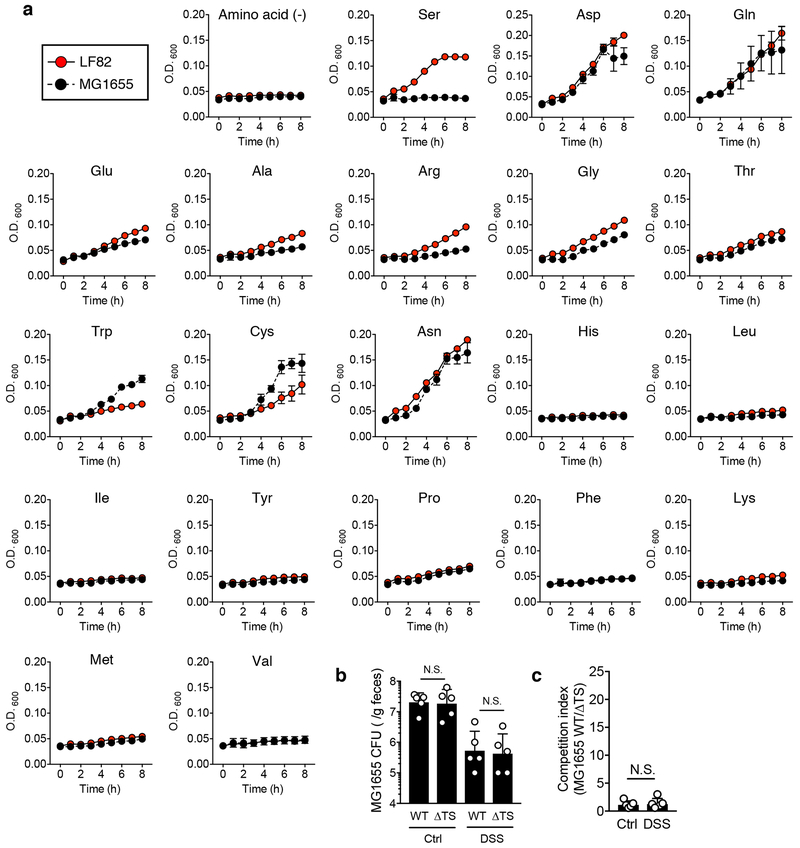

L-serine is a central substrate in the biosynthesis of proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, as well as several other amino acids 19. Due to its importance, E. coli has the highest demand for L-serine among all amino acids 20. Although it is known that the growth efficiency of E. coli in general is very poor when L-serine is the sole carbon source 21, specific strains of E. coli might utilize L-serine more efficiently than others. In this regard, we have reported that LF82 exploits intestinal inflammation caused by Salmonella Typhimurium to promote its fitness, whereas commensal E. coli HS fails to do so 22. We theorized that this phenotype is explained by variability in the efficacy of L-serine utilization between those two strains. To test this hypothesis, we examined the growth capacity of different E. coli strains in the inflamed luminal contents isolated from control and Salmonella-infected mice. Consistent with the data obtained from the in vivo models of colitis, AIEC LF82 and C. rodentium grew significantly more efficiently when cultured under inflammatory conditions ex vivo, whereas this was abolished in the absence of L-serine utilization genes (Fig. 4a). This result indicated that these strains exploit L-serine catabolism to maximize their fitness in the inflamed gut. Like human AIEC, a murine AIEC strain CUMT8 23 employed inflammation to bloom (Fig. 4b). In contrast, inflammation did not promote the growth of human commensal E. coli HS and MG1655 24, 25, human probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917, murine commensal E. coli strains dn15.6244.1 26 and SK460 (Fig. 4b). We next performed a growth competition assay using LF82 and MG1655. At first, we examined the intraspecific competition of these two E. coli strains in a single L-amino acid supplemented medium. Minimal medium supplemented with L-asparagine promotes the growth of both strains equally well (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 4a). However, in a L-serine-supplemented medium, LF82 grew more efficiently than MG1655 (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 4a). To verify the dispensability of L-serine catabolism in MG1655, we generated a MG1655 ΔtdcΔsda double mutant strain and examined its fitness in the inflamed gut. Since MG1655 fails to colonize naïve SPF mice efficiently 25, streptomycin-treated mice were inoculated with MG1655 (Extended Data Fig. 4b, c). In the absence of inflammation, both WT and ΔtdcΔsda MG1655 colonized with equal efficiency (Extended Data Fig. 4b, c). MG1655 colonization was not promoted by the presence of intestinal inflammation (DSS). Rather, inflammation limited the colonization ability of MG1655 (Extended Data Fig. 4b, c). Also, colonization of MG1655 ΔtdcΔsda was similar to the otherwise isogenic WT strain, suggesting that, unlike LF82, MG1655 does not employ L-serine catabolism to maximize its fitness in the inflamed gut.

Figure 4. L-serine catabolism regulates intraspecific competition of E. coli in the inflamed gut.

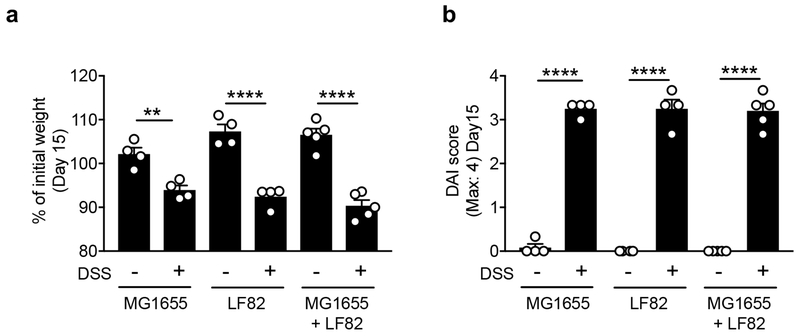

(a) E. coli LF82 WT, LF82 ΔtdcΔsda (ΔTS) mutant, C. rodentium DBS100 WT, and C. rodentium ΔtdcΔsda (ΔTS) mutant strains (1 x 103 CFU) were inoculated into sterilized cecal content isolated from healthy and colitic (Salmonella-induced colitis) and cultured for 8 hrs at 37°C with 20% O2 and 5% CO2. After 8hrs, culture media were plated onto LB agar and bacterial CFUs were measured. Fold increase of bacterial strains in the inflammation (+) luminal content to the inflammation (−) control condition is shown. Dots indicate individual replicates with mean ± s.e.m (N=4, biologically independent samples). N.S.; not significant, *; P < 0.05 by Mann–Whitney U test (two-sided). (b) Each indicated E. coli strain (MG1655, HS, dn15.6244.1 (dn), Nissle 1917 (EcN), SK460, and CUMT8) was cultured in cecal content isolated from control and colitic mice as described in (a). Fold increase of bacterial strains in the inflammation (+) luminal content to the inflammation (−) control condition is shown. Dots indicate individual replicates with mean ± s.e.m (N=4-7, biologically independent samples). N.S.; not significant, ***; P < 0.001 by Mann–Whitney U test (two-sided). (c) Competitive growth assay of LF82 (AmpR) (LF) and MG1655 (StrR) (MG) in a minimal medium supplemented with L-asparagine (Asn) or L-serine (Ser). Bacterial CFUs were quantified by culture on LB plates supplemented with ampicillin or streptomycin. Dots indicate individual replicates with mean ± s.e.m (N=10, biologically independent samples). N.S.; not significant, **; P < 0.01, ****; P < 0.0001 by 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. (d) Germ-free (GF) C57BL/6 mice were mono-colonized either with LF82 or MG1655, or co-colonized both strains (1 x 109/mouse each). On day 10, mice were treated with 1.5% DSS for 5 days. Bacterial CFUs in each mouse was quantified by culturing fecal matter at indicated time points. Data are given as geometric mean ± s.d. (N=3-4, biologically independent animals). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. N.S.; not significant, *; P < 0.05 by Mann–Whitney U test (day 10 (non-inflamed) vs day 15 (inflamed)). (e) GF C57BL/6 mice were co-colonized with LF82 WT or LF82 ΔtdcΔsda double mutant (ΔTS) and a commensal E. coli strain (MG1655 or HS) (1 x 109 CFU each/mouse) for 10 days. On day 10, colitis was induced by 1.5% DSS (for 5 days). Colonization of LF82 WT (LF), LF82ΔTS (ΔTS), and MG1655 (MG) (f) or HS (h) was assessed at indicated time points. Data are presented as a geometric mean ± s.d. The competitive index of LF82 WT/MG1655 (WT) and LF82ΔTS/MG1655 (ΔTS) (g) and LF82 WT/HS (WT) and LF82ΔTS/HS (ΔTS) (i) in the non-inflamed (Non-inf) gut (day 10) and the inflamed gut (day 15) are shown. Dots indicate individual mice with as geometric mean ± s.d (N=5-8, biologically independent animals). (g, i) N.S.; not significant, ***; P < 0.001, ****; P < 0.0001 by 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test.

To confirm the importance of L-serine utilization in intraspecific competition between E. coli strains in vivo, we mono- or co-colonize GF mice with LF82 (L-serine utilizer) and MG1655 (L-serine non-utilizer). Mice were then treated with DSS to induce intestinal inflammation (Extended Data Fig. 5). Intestinal inflammation did not affect the in vivo fitness of LF82 or MG1655 in mono-colonized mice (Fig. 4d). In LF82/MG1655 co-infected mice, both strains co-colonized stably (Fig. 4d). Interestingly, intestinal inflammation promoted the growth of LF82 at the expense of MG1655 (Fig. 4d). To confirm the involvement of L-serine catabolism in the intraspecific competition between these E. coli strains, we next co-infected GF mice with MG1655 and either AIEC LF82 WT or the LF82 ΔtdcΔsda (Fig. 4e). At steady-state, both LF82 WT and LF82ΔtdcΔsda stably colonized the intestine with MG1655 (Fig. 4f, g). Although WT LF82 outcompeted MG1655 in the inflamed gut, LF82ΔtdcΔsda was unable to outcompete MG1655 during inflammation (Fig. 4f, g). We have also confirmed the role L-serine catabolism plays in intraspecific E. coli competition by using E. coli HS (Fig. 4h, i). Thus, L-serine utilization, induced by intestinal inflammation, represents a key strategy by which certain E. coli strains gain a growth advantage over competing bacteria in the inflamed gut.

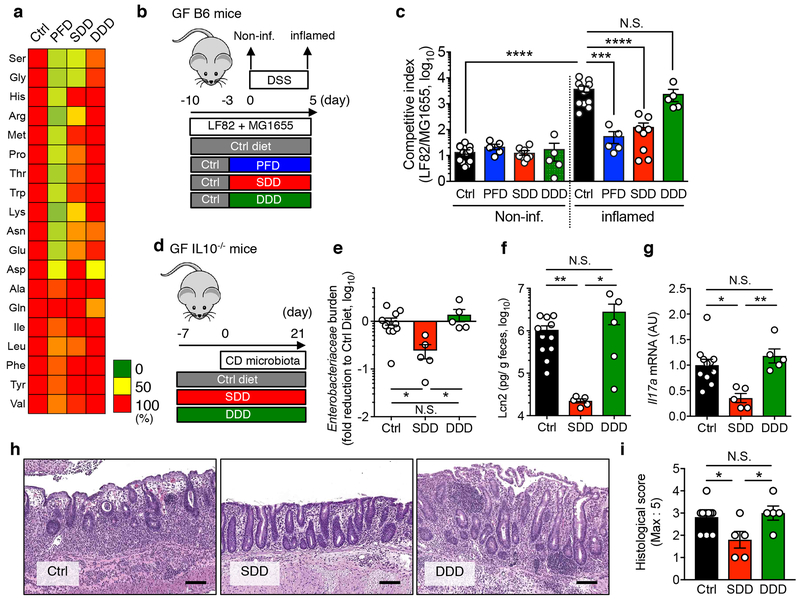

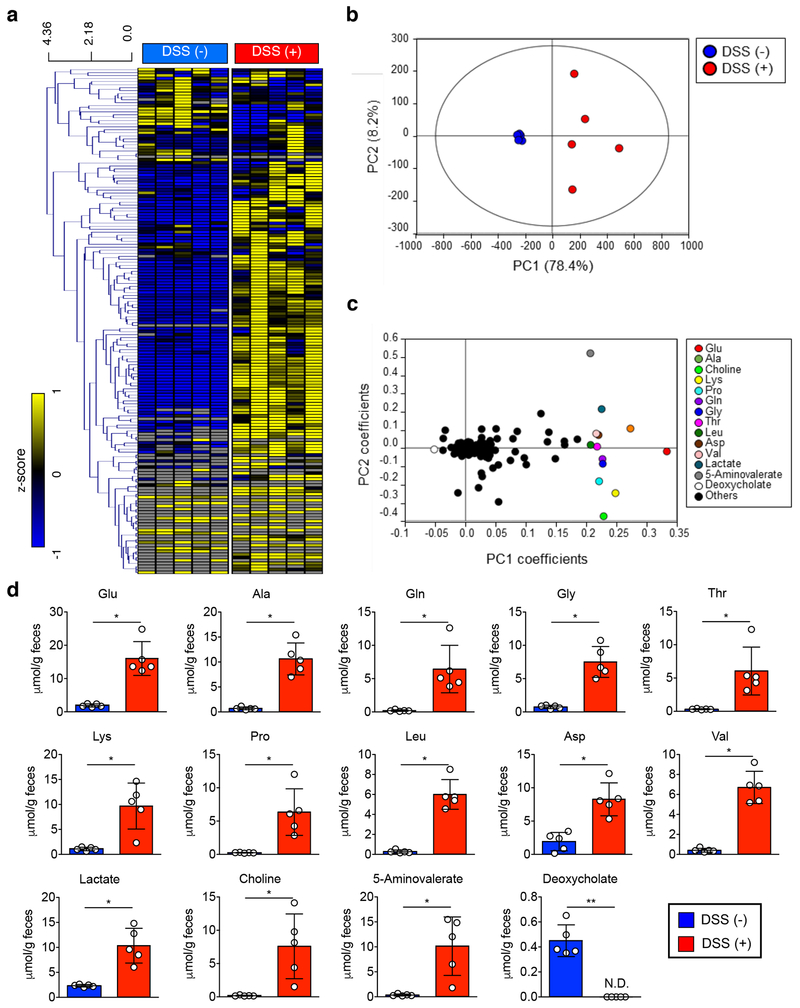

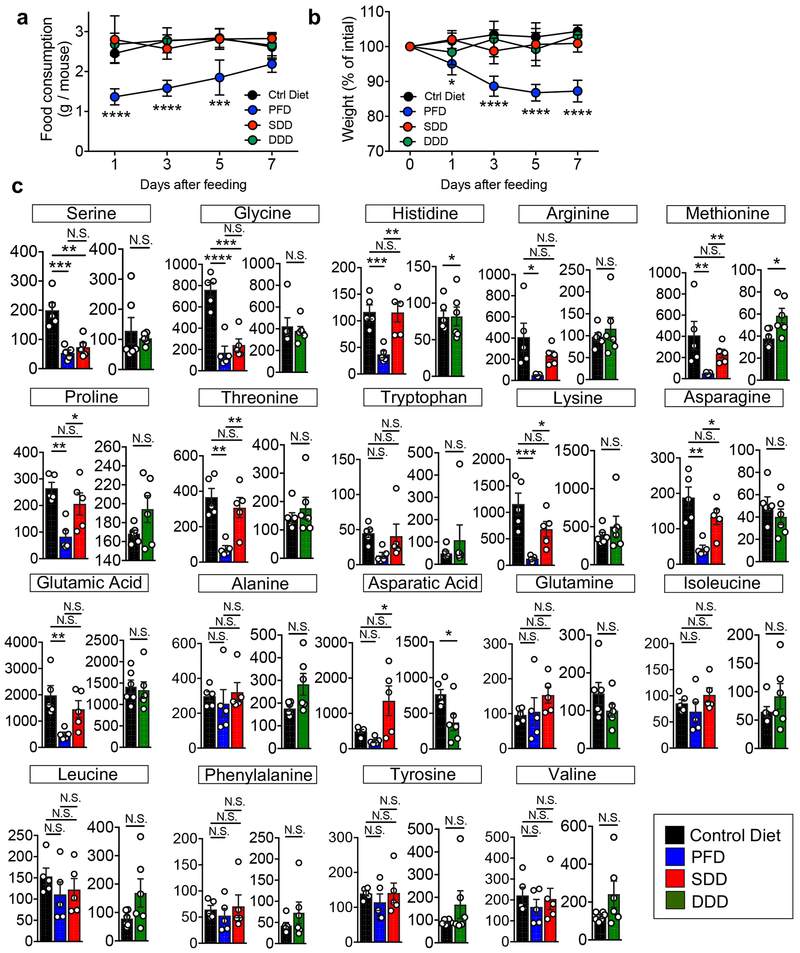

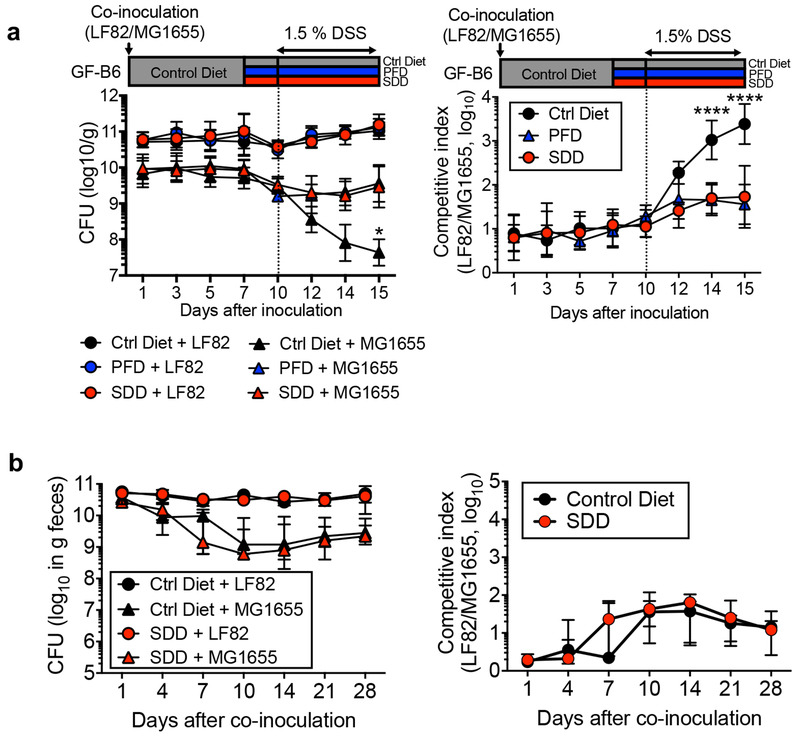

We next sought to determine where luminal L-serine, which drives pathogenic E. coli blooms, originates. To this end, we analyzed the luminal metabolites during intestinal inflammation. Luminal metabolite profiles were significantly altered during colitis with increased concentration of various amino acids (Extended Data Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 2). These amino acids could be released from damaged host tissues and/or the result of the leakage from the vasculature to the luminal surface due to the disruption of tight junctions 27. However, unlike other L-amino acids, the concentration of luminal L-serine was unchanged during intestinal inflammation (Extended Data Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 2). Although the majority of free L-amino acids are absorbed in the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract, a considerable amount of unabsorbed L-amino acids can reach the colon 28. To examine the role of diet-derived amino acids in the gut lumen, SPF mice were fed an amino acid-defined diet (Ctrl), a protein-free diet (PFD) 29 or a L-serine-deficient diet (SDD) 30. Glycine was also removed from the SDD, because serine and glycine may be inter-converted in vivo 31. To validate the specificity of SDD, we also used a L-aspartic acid-deficient diet (DDD). Both LF82 and MG1655 can use L-aspartic acid for their growth (Extended Data Fig. 4). However, unlike L-serine, genes related to L-aspartic acid metabolism are not altered during inflammation (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). First, we monitored consumption of each diet as well as the impact the diets had on body weight. There was no difference in consumption between the control diet and the SDD or the DDD (Extended Data Fig. 7a). Consistent with the amount of diet consumed, we did not detect any difference in animal body weight across the three experimental groups (Extended Data Fig. 7b). However, animals in the PFD group consumed significantly less chow than the other 3 groups, and, as a result, PFD-fed mice experienced body weight loss (Extended Data Fig. 7a, b). Next, we examined changes in the availability of luminal L-amino acids in mice maintained on these diets. The luminal concentrations of L-serine and L-glycine in PFD and SDD groups were lower compared to the control group (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 7c). In DDD-fed mice, the luminal concentration of L-aspartic acid, but not other amino acids, was significantly decreased (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 7c). To address the importance of diet-derived L-serine in intraspecific competition of E. coli, we co-infected GF mice with LF82 and MG1655 (Fig. 5b). Intestinal colonization of both strains was relatively stable and was not affected by dietary changes in healthy mice (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 8). Interestingly, the inflammation-induced dominant colonization of LF82 was blunted when dietary L-serine was depleted (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 8). Notably, the lack of dietary L-aspartic acid did not influence the competition between LF82 and MG1655 at steady-state or during inflammation (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5. Dietary L-serine fosters the bloom of E. coli in the inflamed gut.

(a) SPF C57BL/6 mice were fed a control amino acid-defined diet (Ctrl), protein-free diet (PFD), L-serine and L-glycine-deficient diet (SDD), or L-aspartic acid-deficient diet (DDD) for 14 days. On day 3, fecal samples were collected from all mice. Capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CE-TOF/MS) was used to measure the concentration of luminal L-amino acids. Mean values relative to ctrl diet-fed mice are shown as a heatmap. (b, c) Germ-free (GF) C57BL/6 mice were co-inoculated with AIEC LF82 and commensal E. coli MG1655 for 7days (from day −10 to day −3). All mice were fed the Ctrl diet during this period. After 7 days (on day −3), the diet was switched to PDF, SDD, or DDD. The control group stayed on the Ctrl diet. Three days after switching diets (on day 0), colitis was induced by 1.5% DSS (for 5 days). The competitive index of LF82/MG1655 was analyzed at steady-state (day 0, Non-inf) and during inflammation (day 5, inflamed). Dots indicate individual mice with geometric mean ± s.d. (N=5-12, biologically independent animals). N.S.; not significant, ***; P < 0.001, ****; P < 0.0001 by 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. (d-i) GF Il10−/− mice (N=5-12) were fed either the Ctrl Diet or the amino acid-deficient diet (SDD or DDD) from 7 days prior to microbiota reconstitution. After 7days, a Crohn’s disease patient-derived fecal microbiota was orally inoculated. On day 21 post microbiota transplantation, mice were sacrificed, and intestinal inflammation was evaluated. (e) Fecal Enterobacteriaceae load on day 21 was measured by qPCR. Fecal Lcn2 levels (f), Il17a Mrna expression in the colonic mucosa (f), representative H&E images (scale bar = 100 μm) and histological scores (h, i) on day 21. (e-i) Dots indicate individual mice with geometric mean (e) or mean (f, g, i) ± s.d. N.S.; not significant, *; P < 0.05, **; P < 0.01 by 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test.

Lastly, we asked whether the SDD can be a treatment option for diseases associated with the expansion of pathobiont-type Enterobacteriaceae. To this end, we employed an animal model of CD because the expansion of Enterobacteriaceae, including AIEC, is a hallmark of CD 5, 6. We and others have reported that colonization by microbiotas isolated from CD patients results in the development of severe colitis in various models of colitis, including Il10−/− mice 32, 33. Therefore, we used this CD microbiota-driven model of colitis to validate the therapeutic potential of suppressing the growth of pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae through administration of the SDD. Consistent with the previous report 32, CD microbiota colonization resulted in the development of severe colitis (increased fecal Lcn2, mucosal IL-17A expression, and histopathology) in mice maintained on a control diet (Fig. 5d). As expected, the lack of dietary L-serine reduced gut colonization by Enterobacteriaceae (Fig. 5e). Strikingly, restriction of dietary serine significantly attenuated colitis induced by the CD microbiota (Fig. 5f–i). In contrast, consumption of DDD did not affect the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae or the severity of colitis (Fig. 5e–i). These results demonstrate that withholding dietary L-serine can prevent inflammation-induced bloom of pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae in a CD model, thereby attenuating colitis.

Discussion

The present study provides evidence that nutritional preference of intestinal bacteria relies on the microenvironment that the bacteria face. Some bacteria may utilize different metabolic pathways for their growth depending on the condition of the host. AIEC and C. rodentium employ L-serine metabolism to maximize their fitness in the inflamed gut, while this metabolic pathway is not used or has only a minor role for the bacterial fitness in the healthy gut. Since L-serine is not utilized efficiently for the growth of some E. coli strains, this metabolic reprogramming is crucial for these bacteria to gain a growth advantage over other competing strains. In this study, we demonstrated the critical role of tdc and sda genes in the fitness of E. coli strains in the inflamed gut by using the ΔtdcΔsda mutant strains. Unfortunately, due to the size of operons, we were unable to successfully clone to complement the mutants. However, since a mutation in a single operon (e.g., Δtdc mutant or Δsda mutant) did not affect the ability of either mutant to utilize L-serine, the growth defect seen in the ΔtdcΔsda double mutant is a distinct phenotype that arises in the absence of both operons. Also, the ΔtdcΔsda double knock-out in non-pathogenic E. coli MG1655 did not influence the fitness of this E. coli strain in the inflamed gut. To be more certain, we generated two additional double mutant strains in a clean background to rule out a secondary mutation and those new strains showed identical growth defects on L-serine (Supplementary figure 1).

Although the mechanism by which L-serine promotes the growth of pathogenic E. coli in the inflamed gut remains elusive, E. coli can catabolize L-serine and convert it to pyruvate, which is a necessary substrate for gluconeogenesis and the TCA cycle 31. L-serine can, therefore, be a source of energy. Likewise, L-serine metabolism allows for the synthesis of proteins, nucleic acids and lipids, which are all required for bacterial growth 19. In addition to its metabolic roles, L-serine might act as a signaling molecule that promotes the expression of stress response genes or is used as a precursor in the synthesis of gene products involved in adaptation to stress. In this context, it is known that L-serine catabolism is elevated in E. coli under heat shock conditions and L-serine is probably used for the generation of heat shock proteins 34. Another possibility is that L-serine elicits the secretion of antimicrobial molecules, such as bacteriocin 35. The antimicrobial molecules, in turn, suppress the growth of competing strains, thereby leading to the selective growth of L-serine utilizers. In any scenario, L-serine utilization appears to be a strategy some E. coli, most likely pathobiont-type strains, employ to adapt to environmental change and to compete more effectively with other bacteria. In this regard, L-serine catabolism pathway is used by other enteropathogens for their in vivo growth. For example, Campylobacter jejuni requires sdaA for the persistent colonization 36, 37. Thus, the utilization of L-serine during inflammation most likely is a conserved mechanism that pathogenic bacteria employ for their competitive fitness. However, non-pathogenic E. coli strains also harbor L-serine utilization genes, suggesting that the signals or transduction pathways necessary to activate L-serine catabolism during inflammation could be responsible for pathogen-specific adaptation to the inflammatory microenvironment 21. Pathobionts, including AIEC, might be poised to sense the environmental changesb created by intestinal inflammation, through as yet unidentified mechanisms, to turn on the expression of L-serine catabolism genes.

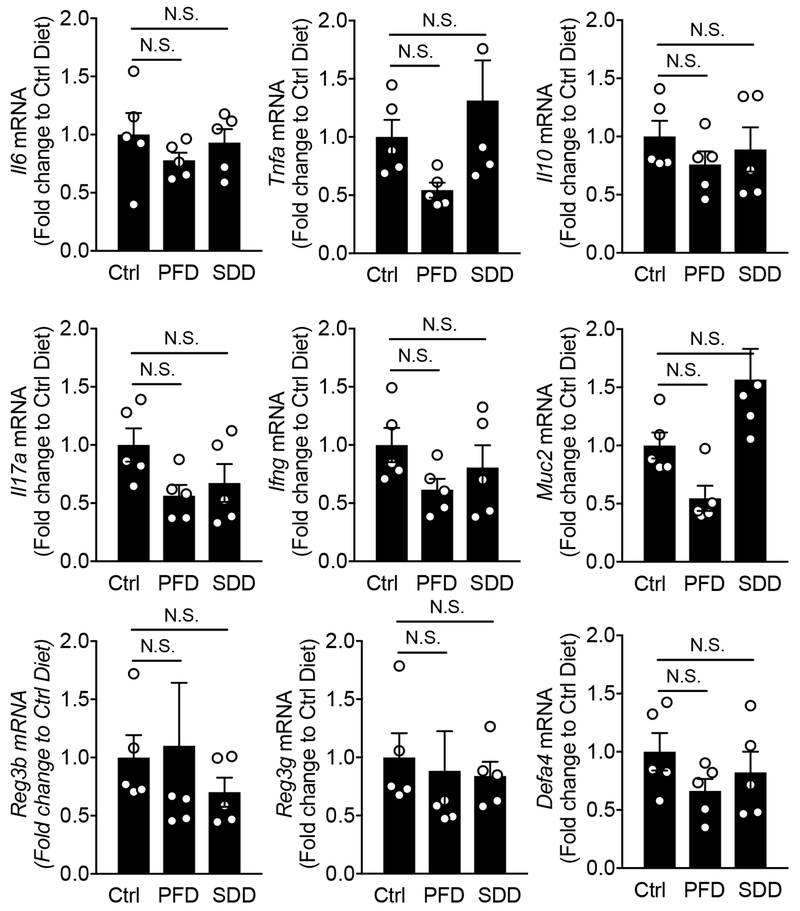

In this study, we have demonstrated that restriction of dietary amino acid, particularly L-serine, intake prevents the expansion of Enterobacteriaceae in the inflamed gut. It is notable that depletion of non-essential amino acids L-serine and L-glycine does not affect host physiology 30. Indeed, deprivation of dietary serine did not affect the expression of host-derived antimicrobial molecules, such as Reg3b and Reg3g, mucus production, as well as host immune responses, such as Il17a, Ifng (Extended Data Fig. 9). While not observed by us, it has been reported that dietary L-serine is a key nutritional factor required for optimal host immune responses during infections caused by bacterial pathogens. For instance, during systemic Listeria monocytogenes infection, L-serine is required for de novo purine biosynthesis in proliferating pathogen-specific effector T cells 38. Hence, lower availability of dietary L-serine results in decreased proliferation of pathogen-specific effector T cells 38. Thus, it remains possible that the deprivation of dietary L-serine prevents the inflammation-induced blooms of Enterobacteriaceae in part through the modification of host immunity.

Taken together, L-serine utilization pathways can be viewed as therapeutic targets that selectively inhibit the growth of certain pathogenic bacteria without influencing beneficial commensal bacteria. Since the diet has been shown to influence the availability of luminal nutrients, appropriate dietary intervention could be used to effectively treat dysbiosis-driven diseases, such as IBD.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and mutant construction

All bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3. E. coli strains were routinely grown aerobically in LB medium (10 g/l tryptone, 5 g/l yeast extract, 10 g/l NaCl) or on LB agar (15 g/l agar) at 37°C. When appropriate, antibiotics were added to the media at the following concentrations: 100 μg/ml Ampicillin (Amp), 25 μg/ml kanamycin (Kan), 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol (Cm) and 100 μg/ml Streptomycin (Str). E. coli LF82 and MG1655 deletion mutants were constructed using the lambda red recombinase system 39. Primers homologous to sequences between the 5’ and 3’ ends of the target genes were designed and used to replace the target genes with a nonpolar kanamycin- or chloramphenicol-resistance cassette derived from template plasmids pKD4 or pKD3, respectively (Supplementary Table 4). Confirmation of E. coli mutants was carried out by PCR using primers flanking the target gene sequence and comparing the product size to the wild-type PCR product size.

Mice

Specific pathogen-free (SPF) C57BL/6 WT, Il10−/−, and Cybb−/− mice were originally purchased from the Jackson Laboratories and housed and bred in the Animal Facility at the University of Michigan. GF WT C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the GF Animal Facility at the University of Michigan or the Charles River Laboratories. GF Il10−/− mice obtained from GF Animal Facility at the University of Michigan. All GF mice were housed in flexible film isolators and their GF status was checked weekly by aerobic and anaerobic culture. The absence of the microbiota was verified by microscopic analysis of stained cecal contents that detects any unculturable contamination. In all animal strains, 8–16-week-old female and male mice were used for the experiments. They were provided with autoclaved distilled water, ad libitum, and animal chow, as described below. SPF mice were fed a sterilized laboratory rodent diet 5L0D (LabDiet). GF and gnotobiotic mice were fed a sterilized rodent breeder diet 5013 (LabDiet). For the experiments with dietary modifications, three types of amino acid-modified diets were used: (i) control diet that contains defined amounts of all 20 amino acids (Ctrl, TD.130595), (ii) protein/amino acid-free diet (PFD, TD.93328), (iii) L-serine and L-glycine-deficient diet (SDD, TD.140546), and (iv) L-aspartic acid-deficient diet (DDD, TD.180664). Custom diets were manufactured by Envigo (Madison, WI, USA) and sterilized by gamma irradiation. All animal studies were performed in accordance with protocols reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Michigan. No statistical methods were used to predetermine the sample size for animal experiments. Mice in the closer ages and similar weight were randomly assigned to experimental and control groups. All animal experiments were not blinded except for the pathology assessment.

Bacterial transcriptome analysis

Cecal contents (100-300mg) from E. coli mono-colonized mice treated with 1.5 % DSS for 5 days were isolated (N=4, each group). Total RNA was extracted by combining Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (pH4.5, Ambion 9720) and LiCl precipitation (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, isolated RNA was treated with DNase (Ambion) and RNeasy (QIAGEN). Any bacterial ribosomal RNAwas depleted by Ribo-zero kit (illumina). Isolated RNA was then assessed for quality using TapeStation (Agilent). Samples with RNA Integrity Numbers (RINs) of 8 or greater were prepped using the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (NEB), NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep kit (NEB) and NEB Next Multiplex Adaptors for Illumina (NEB, E7335, E7500, E6609, E7600). Between 10ng to 1μg of total RNA was converted to mRNA by poly A purification. The mRNA was then fragmented and copied into first strand cDNA using reverse transcriptase and random primers. The 3 prime ends of the cDNA were adenylated and adapters were ligated. The unique 6 nucleotide barcode present in one of the ligated adapters in each sample allowed us to sequence more than one sample in every lane of the Illumina HiSeq flow cell. The products were purified and enriched by PCR to create the final cDNA library. Final libraries were checked for quality and quantity by TapeStation (Agilent) and qPCR using Kapa’s library quantification kit for Illumina Sequencing platforms (Kapa Biosystems). Sixteen samples were multiplexed and pooled. They were clustered on the cBot (Illumina) and sequenced on two lanes of a 50 cycle single end HiSeq 2500 run in High Output mode using version 4 reagents according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Fifty-one base-long high quality unpaired-end reads were mapped on LF82 genomic sequence CU651637 by bowtie2 (ver. 2.3.5.1) with default parameters after the removal of reads mapped on the control PhiX174 and mouse genomes 40, and then reads of individual genes were counted by HTSeq 41. Genes that were expressed at the different levels in two groups were detected by using LEfSe (p<0.05) of Mothur 42, and selected by ‘comparative marker selection’ (false discovery rate q<0.05, 10,000 permutations, all marker detection=0) of GENE-E (software.broadinstitute.org/GENE-E). For network and functional gene ontology analysis, bacterial genes up-regulated (≥2.0 fold, ratio w/ to w/o DSS) or down-regulated (<2.0 fold, ratio w/ to w/o DSS) in each LF82 or MG1655 strain were extracted and analyzed using the STRING protein–protein network database (ver.11.0) 43. The STRING software compiles all available experimental evidence for the reconstruction of functional protein association networks. For each interaction, STRING confers a metric called ‘confidence score’. All interactions fetched in the analysis had a confidence score ≥ 0.4. Multiple rounds of iteration of the Kmeans clustering method using different k seed numbers were performed. The functional gene clusters were then determined by DAVID (ver.6.8) and mapped onto the network.

Fecal metabolome analysis

Capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CE-TOFMS)–based metabolome analysis was conducted as described previously with some modifications 44. In brief, fecal samples were lyophilized using a VD-800R lyophilizer (TAITEC) for 24 hours. Freeze-dried feces were disrupted with 3.0-mm Zirconia Beads (Biomedical Science) by vigorous shaking (1,500 rpm for 10 min) using ShakeMaster (Biomedical Science). Fecal metabolites were extracted using the methanol:chloroform:water extraction protocol. CE-TOFMS experiments were performed using the Agilent CE System, the Agilent G3250AA LC/MSD TOF System, the Agilent 1100 Series Binary HPLC Pump, the G1603A Agilent CE-MS adapter and the G1607A Agilent CE-ESI-MS Sprayer Kit (Agilent Technologies). MasterHands software was used for data processing, quantification and peak annotation 45.

Anaerobic growth of E. coli

Mucin broth was prepared by dissolving 0.5 % mucin in No-Carbon E medium (NCE) supplemented with trace elements 3. Sodium nitrate, DMSO, and TMAO were added to a final concentration of 40 mM. E. coli strains (1 x 104 CFU/ml) were cultured anaerobically for 24 h at 37°C. Bacterial numbers were determined by spreading dilutions on selective LB agar plates.

C. rodentium infection

WT C. rodentium DBS100 (Nalidixic acid-resistant; NalR) or the ΔtdcΔsda double mutant strain (Kanamycin-resistant; KanR) were grown overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with nalidixic acid (50 μg/ml) or kanamycin (50 μg/ml) with shaking at 37°C. Mice were infected by oral gavage with 0.2 ml of PBS containing approximately 1 × 109 CFU of C. rodentium. To measure bacterial colonization, fecal pellets were collected from individual mice, homogenized in cold PBS and plated at serial dilutions on MacConkey agar plates containing antibiotics. Infected mice were sacrificed 12 days post infection. Colons were washed with cold PBS and used for H&E staining. Fecal Lcn2 levels were measured to examine the severity of colitis.

In vitro bacterial culture

For in vitro growth assay, several types of E. coli strains (103 CFU/100 μl) were mono-cultured aerobically in a minimal medium (MM) containing 0.1% glucose supplemented with a single 1 mM amino acid for 8 hours at 37°C in 20% O2 and 5% CO2. Bacterial growth was quantified by optical density measurement (O.D.600). High glucose DMEM (0.45% glucose, Gibco) was used as a positive control. For in vitro competition assay, MG1655 and LF82 were mixed at the ratio of 1:1 (103 CFU each/100 μl) and cultured in MM supplemented with the indicated single amino acid (1 mM) for 8 hours at 37°C anaerobically. For in vitro tdcA activation assay, LF82 was cultured in a custom made DMEM (0% or 0.1% glucose). To examine the influence of O2 concentration, E. coli was cultured in the Coy Microoxic Chamber (2% O2, Coy Laboratory Products) or the Coy Anaerobic Chamber (0% O2, Coy Laboratory Products) for 6 hours at 37°C. Bacterial RNA was extracted using the Trizol Max Bacterial RNA isolation kit (Ambion) and converted to cDNA using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). tdcA expression was quantified by qPCR (primers shown in Supplementary Table 4). For assessing the in vitro tdcA activation in response to NO, the NO-releasing compound 3-[2-hydroxy-1-(1-methylethyl)-2-nitrosohydrazino]-1-propanamine (NOC-5, Calbiochem) was freshly prepared and added to LF82 culture.

Ex vivo growth of E. coli in luminal content

SPF C57BL/6 mice were pre-treated with streptomycin (20 mg/mouse) 1 day prior to infection with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 (2 x 107 CFU/mouse). Two days post Salmonella infection, cecal contents were harvested. Cecal contents were resuspended in a cold PBS at 20mg/ml. Resuspended cecal contents were then centrifuged (500g x 5 min followed by the additional centrifugation at 10,000g x 5 min) to remove intestinal bacteria and debris and then sterilized by passing 0.22 μm filter. The absence of residual bacteria was verified by plating on LB agar 72 hrs. Salmonella uninfected mice were used to obtain control cecal contents. Sterilized luminal contents were stored at −80°C until use. For E. coli ex vivo growth assay, each strain (1 x 103 CFU) was inoculated into sterilized luminal content and cultured for 8 h at 37°C with 20% O2 and 5% CO2. After 8hr, culture media were plated onto LB agar and bacterial CFUs were measured.

In vivo E. coli fitness assay

Naïve SPF C57BL/6 WT mice and colitic mice were inoculated with E. coli strains. For DSS-induced colitis, mice were treated with 1.5% DSS for 5 days. For Il10−/− mice colitis, GF Il10−/− mice received SPF mouse-derived microbial transplants and allowed to reconstitute for 14 days. The presence of active colitis in both models was verified by measuring fecal Lcn2. Control mice and mice with established colitis (day 5 DSS or day 14 conventionalized ex-GF Il10−/− mice) were co-inoculated (at a ratio of 1:1, 1 × 109 CFU each) with E. coli (LF82 or MG1655) WT and the ΔtdcΔsda double mutant. Fecal material was collected 24 hrs post E. coli inoculation. Bacterial load in feces was determined by plating on LB agar plates containing appropriate antibiotics, as described above.

In vivo E. coli competition in gnotobiotic mice

GF C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with different strains of E. coli at a ratio of 1:1 (1 × 109 CFU each). After 7 days of reconstitution, co-colonized animals were treated with filter sterilized 1.5 % DSS (Affymetrix) for 5 days. Fecal material was collected on indicated days post bacterial inoculation and re-suspended in sterile PBS (100 mg/ml). Bacterial load was determined by plating the suspended fecal material on LB agar plates containing appropriate antibiotics, as described above. In dietary intervention experiments, animals were placed in clean cages when animal diet was changed so as to remove any residual chow.

CD microbiota-induced colitis model

The CD microbiota-induced colitis model was previously reported by us 32. Briefly, GF IL-10-deficient nC57BL/6 mice were fed a Ctrl diet or SDD for 7 days. Mice were then reconstituted with the microbiota isolated from a CD patient 32. CD-derived microbiota colonized mice were kept under GF condition for 21 days. At day 21, all mice were sacrificed, and the tissue samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed tissues were processed for H&E staining. The following were used as histology criteria (0 -5): 0; none, 1; minimal (lesions restricted to mucosa; lesions consist of minimal hyperplasia with minimal scattered inflammation), 2; mild (lesions affecting mucosa with infrequent submucosal extension; lesions consist of mild hyperplasia with mild inflammation +/− minimal goblet cell loss, and/or erosions), 3; moderate (lesions affecting mucosa and submucosa; lesions consist of moderate hyperplasia with moderate inflammation +/− few crypt abscesses, moderate goblet cell loss, and/or erosions), 4; severe (lesions affecting mucosa and submucosa; lesions consist of severe hyperplasia with multifocal severe inflammation +/− several crypt abscesses, erosions/ulcerations, and/or irregular crypts/crypt loss), 5; marked (trasmural lesions, lesions consist of marked hyperplasia with marked inflammations, +/−multiple crypt abscesses, erosions/ulcerations, irrecular crypts/crypt loss, and/or inflammation). Histologic assessment was performed by a pathologist in a blinded fashion at the ULAM In Vivo Animal Core.

Bone marrow-derived Macrophages (BMDM) stimulation

Bone marrow cells were isolated from SPF WT C57BL/6 mice. Bone marrow cells were then cultured for 6 days with Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium supplemented with 30% L929 supernatant containing macrophage-stimulating factor, glutamine, sodium pyruvate, 10% FBS and antibiotics. Mycoplasma contamination was not tested for freshly prepared for bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs). Differentiated BMDMs were seeded (2 x 105 cells/well/48 well plate in 200 ml) and stimulated with MG1655, AIEC LF82 WT or LF82 ΔtdcΔsda double mutant (ΔTS) strains at a MOI=5 for 3 hrs, followed by 15 hrs of additional culture in the presence of gentamycin (100 μg/ml) to prevent bacterial overgrowth. Culture supernatants were harvested, and cytokines were measured by ELISA.

Bacterial invasion assay

Authenticated T84 cell line cells (human colonic epithelial cells, ATCC® CCL-248™) was purchased from ATCC. T84 cells were seeded onto 24 well plates (2 x 105 cells/well/24 well plate in 500 μl) and cultured for 3 weeks. Polarized cells were then washed three times with ice-cold PBS and the DMEM media without antibiotics was added. E. coli strain (1 x 106 cells/well) were then added into T84 cells culture. Cell culture plates were then centrifuged (900g x 10 min) to promote bacterial attachment to the cells, and then incubated for 3 hrs at 37°C with 20% O2 and 5% CO2. After 3 hrs, cells were washed, and extracellular bacteria were killed by gentamycin (100 μg/ml). Intracellular (invaded) bacteria werethen quantified by culture on LB agar plates. The percentage of intracellular bacteria was calculated.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 7.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.). Statistical tests used for experiments are provided in Figure legends. Differences of P<0.05 were considered significant.

Data Availability

Source data for all Figures and Extended data Figures are provided with the paper. E. coli LF82 RNA-seq that used in this study has been deposited in GEO under the accession number GSE106412. The metabolome data obtained in this study is available at the NIH Common Fund’s Data Repository and Coordinating Center (supported by NIH grant, U01-DK097430) website, the Metabolomics Workbench, http://www.metabolomicsworkbench.org, where it has been assigned Project ID XXXXX. The data can be accessed directly via it’s Project DOI: XXXXXX

Extended Data

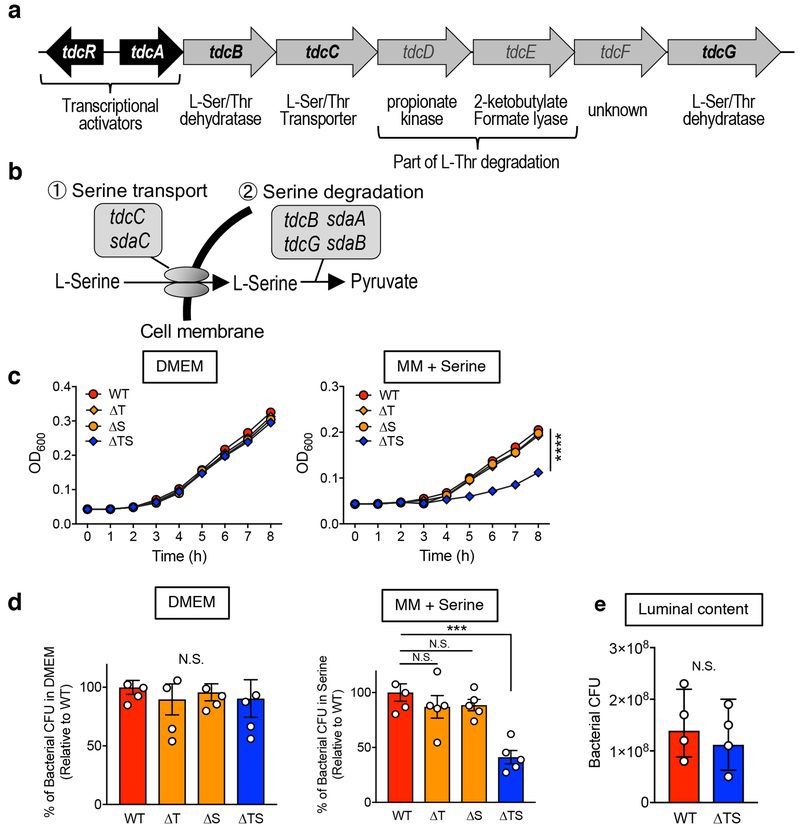

Extended Data Fig. 1. L-serine catabolism mutant LF82 ΔtdcΔsda has serine-dependent growth defect.

Diagram of tdc gene operon (a) and L-serine catabolism pathway in E. coli (b). (c, d) AIEC LF82 WT, Δtdc (ΔT), Δsda (ΔS), and ΔtdcΔsda (ΔTS) mutant strains were cultured in DMEM (0.45% glucose) or a minimal medium (0.1% glucose) supplemented with 1 mM serine for 8 hours at 37°C with 20% O2 and 5% CO2. Growth kinetics (O.D600) are shown. Data represent mean ± s.d. (N=5, technical replicates). Results are representative of 2 biologically independent experiments. ****; P < 0.0001 by 2-Way ANOVA (ΔTS vs WT, ΔT or ΔS). (d) Bacterial CFUs at 8 h were measured by plating on LB agar. Each number inside the bar indicates percent growth to WT LF82. (e) Luminal contents from ceca were collected from SPF C57BL/6 WT mice. The debris and bacteria were removed by centrifugation followed by filtration (0.2 μm). AIEC LF82 WT or ΔTS mutant were cultured in 20% sterilized luminal content for 8 h at 37°C with 20% O2 and 5% CO2. Bacterial CFUs were measured by plating on LB agar. (d, e) Data represent geometric mean ± s.d. (N=4-5, biological replicates). N.S.; not significant, ***; P <0.001 by Mann–Whitney U test (two-sided) (e) or 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test (d).

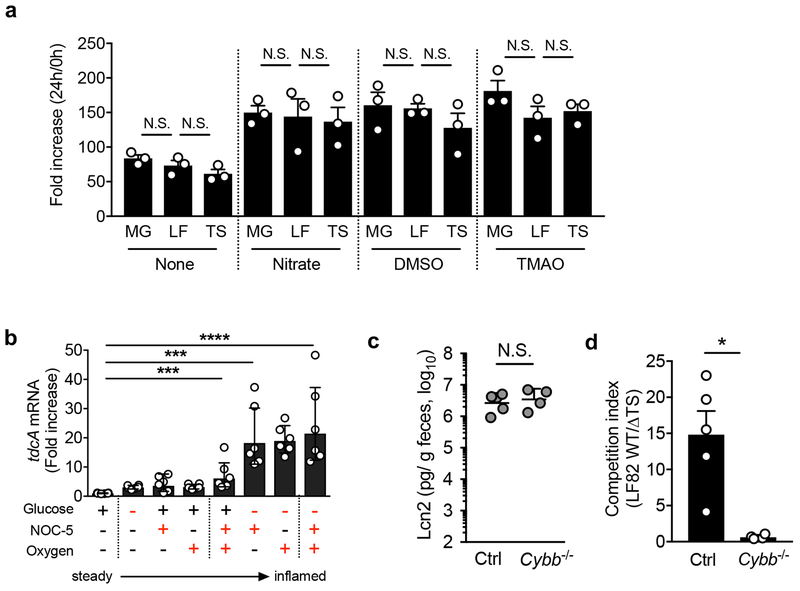

Extended Data Fig. 2. Inflammation-associated milieu may regulate the expression of tdcA in E. coli.

(a) Mucin broth was prepared by dissolving 0.5 % mucin in None-Carbon E medium (NCE) supplemented with trace elements. Sodium nitrate, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) were added to a final concentration of 40 mM. Mucin broth without any supplementation (None) was used as a control. Each E. coli strain (MG1655 (MG), LF82 (LF), and LF82ΔtdcΔsda double mutant (TS)) was inoculated (1 x 104 CFU/ml) in the medium and incubated anaerobically for 24 h at 37°C. Bacterial numbers were determined by spreading dilutions on selective LB agar plates. The fold increase was calculated by normalizing the CFU at 24 hrs to the respective CFU at 0 hrs. Data represent geometric mean ± s.d. (N=3, biologically independent samples). N.S.; not significant by 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. (b) AIEC LF82 was cultured in vitro for 8 hrs at 37°C. The expression of tdcA mRNA was assessed by qPCR. Fold expression of tdcA in steady state-like conditions (DMEM supplemented with 0.1% glucose, cultured in 0% oxygen) is shown. Different concentrations of glucose (0.1% glucose or 0% glucose) and oxygen (0% oxygen or 2% oxygen) were tested. 3-[2-hydroxy-1-(1-methylethyl)-2-nitrosohydrazino]-1-propanamine (NOC-5) (10 mM) was added to mimic the presence of nitric oxide (NO). Data are represented as mean ± s.d.. Dots indicate individual biological replicates. ***; P < 0.001, ****; P < 0.0001 by Dunnett test. (c) SPF C57BL/6 mice WT (Ctrl) and Cybb−/− mice were treated with 3% DSS for 5 days. At day 5 post DSS treatment, mice were co-inoculated with LF82 WT and ΔtdcΔsda (ΔTS) mutant (1 x 109 CFU each/mouse). Fecal samples were collected 24 hrs post E. coli inoculation. Fecal lipocalin-2 (Lcn2) levels (a) and the competitive index (LF82 WT/LF82 ΔTS) (d) are shown. Bars represent geometric mean ± s.d. Dots indicate individual mice. (N=4-5, biologically independent animals). N.S.; not significant, * P < 0.05 by Man-Whitney U test (two-sided).

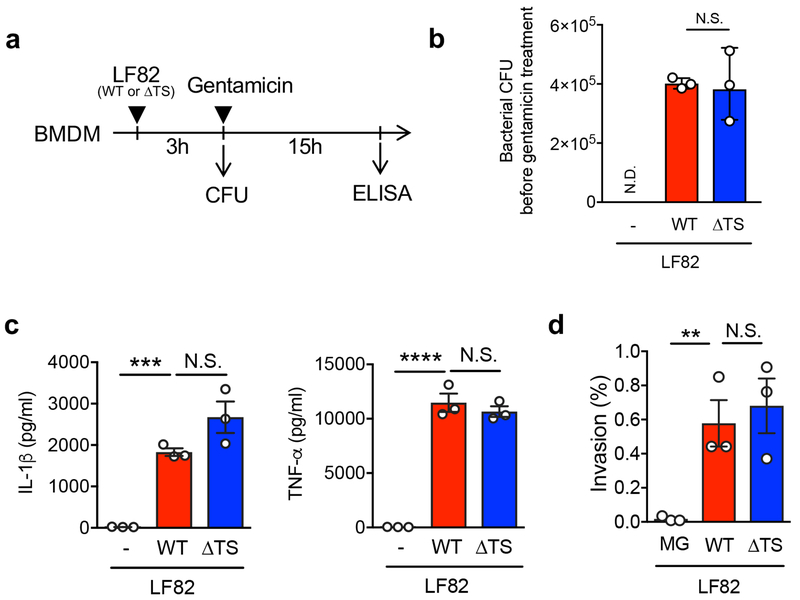

Extended Data Fig. 3. L-serine metabolism pathways are not required for AIEC virulence.

(a) Experimental procedure: BMDMs (2 x 105 cells/well/48 well plate in 200 μl) were stimulated with MG1655, AIEC LF82 WT or LF82 ΔtdcDsda double mutant (ΔTS) strains at a MOI=5 for 3 hrs, followed by 15 hrs of additional culture in the presence of gentamycin (100 μg/ml) to prevent bacterial overgrowth. (b) Bacterial CFU was measured before gentamicin treatment (3hrs). Data represents geometric mean ± s.d. Dots indicate individual biological replicate (N=3). N.S.; not significant. (c) Culture supernatants were harvested, and cytokines were measured by ELISA. Data represents mean ± s.d. Dots indicate individual biological replicate (N=3). N.S.; not significant, ***; P <0.001, ****; P < 0.0001 by 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. (d) T84 intestinal epithelial cells (2 x 105 cells/well/24 well plate in 500 μl) were grown for 3 weeks and infected with each E. coli strain (2 x 106 cells/well). After 3 hrs, cells were washed, and extracellular bacteria were killed by gentamycin (100 μg/ml). Intracellular bacteria were then quantified by culture on LB agar plates. The percentage of intracellular bacteria was calculated. Data represents mean ± s.d. Dots indicate individual biological replicate (N=3). N.S.; not significant, **; P < 0.01 by 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test.

Extended Data Fig. 4. LF82 but not MG1655 employs L-serine for its growth.

(a) AIEC LF82 and commensal E. coli MG1655 were cultured in DMEM (0.45% glucose) or in a minimal medium (0.1% glucose) supplemented with a single L-amino acid (final concentration was 1mM) for 8 h at 37°C in 20% O2 and 5% CO2. Bacterial proliferation (O.D600) is shown. Data represent mean ± s.d. (N=2, technical replicates). Results are representative of 2 biologically independent experiments. SPF C57BL/6 mice were pretreated with streptomycin (800mg/kg, p.o.) 1 day prior to the treatment with 3.0% DSS. Control (Ctrl) and DSS-treated mice (day 5 post 3.0% treatment) were then co-inoculated with MG1655 WT and MG1655 ΔtdcΔsda (ΔTS) mutant (1 x 109 CFU each/mouse). Fecal samples were collected 24 hrs post E. coli inoculation. Bacterial CFUs in feces (b) and the competitive index (WT/ΔTS) (c) are shown. Bars represent geometric mean ± s.d. Dots indicate individual mice (N=5, biologically independent animals). N.S.; not significant by Man-Whitney U test (two-sided) or 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Severity of DSS colitis in gnotobiotic mice.

Germ-free (GF) C57BL/6 mice (N=4, biologically independent animals) were mono-colonized either with MG1655 or LF82, or co-colonized with those two strains (1 x 109 CFU each/mouse) for 10 days. On day 10, colitis was induced by 1.5% DSS (for 5 days). Body weight change at day 15 (% of initial (day 10)) (a) and disease activity index (DAI) (day 10 and day 15) (b) are shown. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. Dots indicate individual mice. **; P < 0.01, **** P < 0.0001 by Man-Whitney U test (two-sided).

Extended Data Fig. 6. Intestinal inflammation alters the luminal metabolome.

SPF C57BL/6 mice (N=5, biologically independent animals) were treated with 1.5% DSS for 5 days. Cecal samples were harvested and luminal metabolic profiles were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CETOF/MS). (a) A heatmap of the quantified luminal metabolites. The concentrations of metabolites were transformed into Z-scores and clustered according to their Euclidean distance. Gray areas in the heatmap indicate that respective metabolites were not detected. (b) Principal component analysis (PCA) of the luminal metabolome data. The ellipse denotes the 95% significance limit of the model, as defined by Hotelling’s t-test. (c) A loading scatter plot of the PCA. (d) The bar graphs showing the selected metabolites whose concentrations were altered significantly during DSS colitis. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. Dots represents individual mice (N=5, biologically independent animals). N.D.; not detected, *; P < 0.05, **; P < 0.01 by Mann–Whitney U test (two-sided).

Extended Data Fig. 7. Effect of dietary amino acid modification on mice.

(a, b) SPF C57BL/6 mice were fed a control amino acid defined diet (Ctrl), protein-free diet (PFD), L-serine-L-glycine-deficient diet (SDD), or Laspartic acid-deficient diet (DDD) for 7 days. Food consumption (a) and body weight change (b) were monitored at indicated time points. Four individual cages were used for each diet. Each cage contains 2-5 biologically independent mice. Food consumption amount per mouse in each cage was calculated. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. (N=4, biologically independent experiments). N.S.; not significant, *; P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test (Ctrl vs PFD). (c) SPF C57BL/6 mice were fed the Ctrl, PFD, SDD, or DDD for 3 days. On day 3, fecal samples were collected from each mouse. Capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CETOF/MS) was used to measure the concentration of luminal L-amino acids. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. Dots indicate individual mice (N=5-6, biologically independent animals). N.S.; not significant, *; P < 0.05, **; P < 0.01, ***; P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test or Man-Whitney U test (two-sided).

Extended Data Fig. 8. Dietary L-serine regulates intraspecific competition between E. coli in the inflamed gut.

(a) Germ-free (GF) C57BL/6 mice were co-inoculated with LF82 and MG1655 for 7 days. All mice were fed the control amino acid-defined (Ctrl) diet during this period. On day 7, the diet was switched to protein-free diet (PFD) or L-serinedeficient diet (SDD). The control group stayed on the ctrl diet. Three days after switching diets, colitis was induced by 1.5% DSS (5-day treatment). (Left) Bacterial CFUs and the (Right) competitive index of LF82/MG1655 were analyzed at indicated time points. Data are represented as geometric mean ± s.d. (N=5-8, biologically independent animals). *; P<0.05, ****; P< 0.0001: 2-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test (Left: Ctrl diet + MG1655 vs. SDD + MG1655, Right: Ctrl Diet vs SDD). (b) GF C57BL/6 mice were fed Ctrl diet or SDD. After three days, the mice were co-inoculated with LF82 and MG1655. Bacterial CFUs and the competitive index of LF82/MG1655 were analyzed at indicated time points. Data are represented as geometric mean ± s.d. (N=5, biologically independent animals).

Extended Data Fig. 9. Deprivation of dietary L-serine does not influence host anti-microbial immunity.

SPF C57BL/6 mice (N=5, biologically independent animals) were fed a control amino acid-defined diet (Ctrl), protein-free diet (PFD), or L-serine and L-glycine-deficient diet (SDD) for 14 days. Colonic mucosa was isolated at day 14 and the expression of host anti-microbial genes was analyzed by qPCR. Data are represented as mean ± s.d. Dots indicate individual mice. N.S.; not significant, by 1-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Michigan Center for Gastrointestinal Research (UMCGR) (NIH 5P30DK034933), Host Microbiome Initiative, Germ-free Animal Facility, DNA Sequencing Core, and Bioinformatics Core, and In Vivo Animal Core at the University of Michigan Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine for performing pathology assessment. S. Yamada, J. Imai, Y-G. Kim, and E.C. Martens for technical assistance, M. Y. Zeng for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Kenneth Rainin Foundation Innovator Award (N.K.), National Institute of Health DK110146, DK108901, and DK119219 (N.K.), T32 DK094775 (T.L.M.), Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (N.K and H.N.-K.), JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad (S.K., H.N.-K., and K.S.), the Uehara Memorial Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (S.K. and K.S.), University of Michigan Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program (S.K.), Prevent Cancer Foundation (S.K.), JSPS 11 KAKENHI 16H04901, 17H05654, and 18H04805 (S.F.), JST PRESTO JPMJPR1537 (S.F.), AMED-CREST JP19gm1010009 (S.F.), the Takeda Science Foundation (S.F.), the Food Science Institute Foundation (S.F.), Université Clermont Auvergne (N.B.), Inserm (U1071) (N.B.), and INRA (USC-2018) (N.B.).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Kamada N et al. Regulated virulence controls the ability of a pathogen to compete with the gut microbiota. Science 336, 1325–1329 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conway T & Cohen PS Commensal and Pathogenic Escherichia coli Metabolism in the Gut. Microbiology spectrum 3 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winter SE et al. Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science 339, 10708–711 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu W et al. Precision editing of the gut microbiota ameliorates colitis. Nature 553, 208–211 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan XC et al. Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol 13, R79 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darfeuille-Michaud A et al. Presence of adherent Escherichia coli strains in ileal mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 115, 1405–1413 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carvalho FA et al. Crohn’s disease-associated Escherichia coli LF82 aggravates colitis in injured mouse colon via signaling by flagellin. Inflamm Bowel Dis 14, 1051–1060 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvalho FA et al. Crohn’s disease adherent-invasive Escherichia coli colonize and induce strong gut inflammation in transgenic mice expressing human CEACAM. J Exp Med 206, 2179–2189 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chassaing B, Koren O, Carvalho FA, Ley RE & Gewirtz AT AIEC pathobiont instigates chronic colitis in susceptible hosts by altering microbiota composition. Gut 63, 1069–1080 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Small CL, Xing L, McPhee JB, Law HT & Coombes BK Acute Infectious Gastroenteritis Potentiates a Crohn’s Disease Pathobiont to Fuel Ongoing Inflammation in the Post-Infectious 33 Period. PLoS Pathog 12, e1005907 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viladomiu M et al. IgA-coated E. coli enriched in Crohn’s disease spondyloarthritis promote TH17-dependent inflammation. Sci Transl Med 9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang DE et al. Carbon nutrition of Escherichia coli in the mouse intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 7427–7432 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vijay-Kumar M et al. Deletion of TLR5 results in spontaneous colitis in mice. J Clin Invest 117, 423909–3921 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peekhaus N & Conway T What’s for dinner?: Entner-Doudoroff metabolism in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 180, 3495–3502 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigottier-Gois L Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel diseases: the oxygen hypothesis. Isme j 7, 1256–1261 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez CA et al. Virulence factors enhance Citrobacter rodentium expansion through aerobic respiration. Science 353, 1249–1253 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pullan ST et al. Nitric oxide in chemostat-cultured Escherichia coli is sensed by Fnr and other global regulators: unaltered methionine biosynthesis indicates lack of S nitrosation. J Bacteriol 189, 1845–1855 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins JW et al. Citrobacter rodentium: infection, inflammation and the microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol 12, 612–623 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawers G The anaerobic degradation of L-serine and L-threonine in enterobacteria: networks of pathways and regulatory signals. Archives of microbiology 171, 1–5 (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reitzer L Nitrogen assimilation and global regulation in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol 57, 155–176 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zinser ER & Kolter R Mutations enhancing amino acid catabolism confer a growth advantage in stationary phase. J Bacteriol 181, 5800–5807 (1999) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imai J et al. Flagellin-mediated activation of IL-33-ST2 signaling by a pathobiont promotes intestinal fibrosis. Mucosal Immunol 12, 632–643 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craven M et al. Inflammation drives dysbiosis and bacterial invasion in murine models of ileal Crohn’s disease. PLoS One 7, e41594 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasko DA et al. The pangenome structure of Escherichia coli: comparative genomic analysis of E. coli commensal and pathogenic isolates. J Bacteriol 190, 6881–6893 (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miranda RL et al. Glycolytic and gluconeogenic growth of Escherichia coli O157:H7 (EDL933) and E. coli K-12 (MG1655) in the mouse intestine. Infect Immun 72, 1666–1676 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bloom SM et al. Commensal Bacteroides species induce colitis in host-genotype-specific fashion in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Host Microbe 9, 390–403 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ralls MW et al. Bacterial nutrient foraging in a mouse model of enteral nutrient deprivation: insight into the gut origin of sepsis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 311, G734–g743 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto M et al. Impact of intestinal microbiota on intestinal luminal metabolome. Scientific reports 2, 233 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto T et al. ACE2 links amino acid malnutrition to microbial ecology and intestinal 46 inflammation. Nature 487, 477–481 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maddocks OD et al. Serine starvation induces stress and p53-dependent metabolic remodelling in cancer cells. Nature 493, 542–546 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pizer LI & Potochny ML NUTRITIONAL AND REGULATORY ASPECTS OF SERINE METABOLISM IN ESCHERICHIA COLI. J Bacteriol 88, 611–619 (1964) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagao-Kitamoto H et al. Functional characterization of inflammatory bowel disease-associated gut dydbiosis in gnotobiotic mice. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2, 468–481 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Britton GJ et al. Microbiotas from Humans with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Alter the Balance of Gut Th17 and RORgammat(+) Regulatory T Cells and Exacerbate Colitis in Mice. Immunity 50, 212–224.e214 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthews RG & Neidhardt FC Elevated serine catabolism is associated with the heat shock response in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 171, 2619–2625 (1989) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sassone-Corsi M et al. Microcins mediate competition among Enterobacteriaceae in the 20 inflamed gut. Nature 540, 280–283 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velayudhan J, Jones MA, Barrow PA & Kelly DJ L-serine catabolism via an oxygen-labile L-serine dehydratase is essential for colonization of the avian gut by Campylobacter jejuni. Infect Immun 72, 260–268 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofreuter D et al. Contribution of amino acid catabolism to the tissue specific persistence of Campylobacter jejuni in a murine colonization model. PLoS One 7, e50699 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma EH et al. Serine Is an Essential Metabolite for Effector T Cell Expansion. Cell metabolism 30 25, 345–357 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Datsenko KA & Wanner BL One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 6640–6645 (2000) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langmead B & Salzberg SL Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature methods 9, 36 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anders S, Pyl PT & Huber W HTSeq--a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 31, 166–169 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schloss PD et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75, 7537–7541 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szklarczyk D et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic acids research 43, D447–452 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirayama A et al. Metabolic profiling reveals new serum biomarkers for differentiating diabetic nephropathy. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 404, 3101–3109 (2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sugimoto M, Wong DT, Hirayama A, Soga T & Tomita M Capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry-based saliva metabolomics identified oral, breast and pancreatic cancer-specific profiles. Metabolomics : Official journal of the Metabolomic Society 6, 78–95 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schauer DB & Falkow S Attaching and effacing locus of a Citrobacter freundii biotype that 10 causes transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Infect Immun 61, 2486–2492 (1993) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data for all Figures and Extended data Figures are provided with the paper. E. coli LF82 RNA-seq that used in this study has been deposited in GEO under the accession number GSE106412. The metabolome data obtained in this study is available at the NIH Common Fund’s Data Repository and Coordinating Center (supported by NIH grant, U01-DK097430) website, the Metabolomics Workbench, http://www.metabolomicsworkbench.org, where it has been assigned Project ID XXXXX. The data can be accessed directly via it’s Project DOI: XXXXXX