Abstract

Cell division cycle 25 (Cdc25) and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 (MKK7) are enzymes involved in intracellular signaling but can also contribute to tumorigenesis. We synthesized and characterized the biological activity of 1,4-naphthoquinones structurally similar to reported Cdc25 and(or) MKK7 inhibitors with anticancer activity. Compound 7 (3-[(1,4-dioxonaphthalen-2-yl)sulfanyl]propanoic acid) exhibited high binding affinity for MKK7 (Kd = 230 nM), which was greater than the affinity of NSC 95397 (Kd = 1.1 μM). Although plumbagin had a lower binding affinity for MKK7, this compound and sulfur-containing derivatives 4 and 6–8 were potent inhibitors of Cdc25A and Cdc25B. Derivative 22e containing a phenylamino side chain was selective for MKK7 versus MKK4 and Cdc25 A/B, and its isomer 22f was a selective inhibitor of Cdc25 A/B. Docking studies performed on several naphthoquinones highlighted interesting aspects concerning the molecule orientation and hydrogen bonding interactions, which could help to explain the activity of the compounds toward MKK7 and Cdc25B. The most potent naphthoquinone-based inhibitors of MKK7 and/or Cdc25 A/B were also screened for their cytotoxicity against nine cancer cell lines and primary human mononuclear cells, and a correlation was found between Cdc25 A/B inhibitory activity and cytotoxicity of the compounds. Quantum chemical calculations using BP86 and ωB97X-D3 functionals were performed on 20 naphthoquinone derivatives to obtain a set of molecular electronic properties and to correlate these properties with cytotoxic activities. Systematic theoretical DFT calculations with subsequent correlation analysis indicated that energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital E(LUMO), vertical electron affinity (VEA), and reactivity index ω of these molecules were important characteristics related to their cytotoxicity. The reactivity index ω was also a key characteristic related to Cdc25 A/B phosphatase inhibitory activity. Thus, 1,4-naphthoquinones displaying sulfur-containing and phenylamino side chains with additional polar groups could be successfully utilized for further development of efficacious Cdc25 A/B and MKK7 inhibitors with anticancer activity.

Keywords: Naphthoquinone, Kinase inhibitor, Mitogen-activated kinase kinase 7, Cdc25 phosphatase, Cytotoxicity, Molecular docking, DFT analysis

1. Introduction

Naphthoquinone derivatives, including vitamin K3 analogs and plant-derived naphthoquinones, have been reported to exhibit a variety of pharmacological properties involving antimicrobial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor effects [1-4]. Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the world, and recent advances in the field of novel anticancer agents has been promising. Naphthoquinone derivatives may be attractive for the development of novel anticancer agents because they have a broad spectrum of biological activities and could target multiple signaling pathways in tumor cells. Studies of the antitumor properties and mechanisms of action of various naphthoquinone derivatives have shown that they can act as inhibitors of cell division cycle 25 (Cdc25) phosphatases and DNA topoisomerases, disrupt kinase signaling important for cancer cell proliferation, and inhibit Snail-p53 binding [5-9]. Their cytotoxicity can also be explained by oxidative stress induced via reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and glutathione depletion [10-12]. Indeed, the 1,4-naphthoquinone moiety can form redox isomers, such as napthosemiquinones and catechols, by accepting one or two electrons, respectively, during metabolism by quinone oxidoreductase, which is overexpressed in solid tumors from a variety of cancer types [13].

One naphthoquinone with multiple biological mechanisms is NSC 95397 (2,3-bis-[(2-hydroxyethyl)thio]-1,4-naphthoquinone), an inhibitor of protein kinase B (Akt), IκB kinases α/β (IKKα/β), TANK-binding kinase (TBK1), and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 (MKK7) [14]. NSC 95397 suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells through mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) pathway [15]. Moreover, NSC 95397 inhibits the C-terminal binding protein (CtBP1)-protein partner interaction and CtBP1-mediated transcriptional repression, which are important pathways in cancer cell survival [16]. This compound was first identified in a high-throughput screening program as a potent irreversible inhibitor of cell division cycle 25 (Cdc25) [17]. Cdc25 dual specificity phosphatases, which include A, B, and C isoforms, serve as important regulators of cell cycle progression by activating the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) through removal of inhibitory phosphates from tyrosine/threonine residues [18]. Cdc25B and Cdc25C play a major role in the G2/M progression of the cell cycle, whereas Cdc25A assists in the G1/S phase transition [19]. Cdc25 phosphatases seem to play a role in the development of several human malignancies, including acute myeloid leukemia, and Cdc25 inhibition is therefore considered as a possible anticancer strategy [20]. Over half of the 15 different cancers studied overextressed both Cdc25A and Cdc25B; the remainder overexpressed either Cdc25A or Cdc25B, whereas there was no significant overexpression of Cdc25C [21]. Thus, small-molecule inhibitors of these phosphatases may represent promising therapeutic anticancer agents [22].

c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling also plays a vital role in metastasis and malignant transformation in various cancers and is involved in cancer cell apoptosis [23-25]. For example, JNK is highly activated in basal-like ‘triple-negative’ breast cancer [26]. Reduced JNK activation is associated with better overall survival of patients with infiltrating ductal breast carcinoma [27]. Several other publications indicate that targeting JNK signaling has potential for cancer treatment (e.g., Ref. [28]). There are only two direct upstream activators of JNK: mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 and 7 (MKK4 and MKK7) [29]. MKK4 activates JNK primarily in response to stress stimuli, whereas MKK7 signaling is triggered by release of inflammatory cytokines [30]. Thus, by targeting MKK7, the physiological role of JNK regulated by MKK4 would be preserved. Development of MKK7 inhibitors could represent a new therapeutic strategy for the treatment of ischemia and other pathologies involving MKK7 and(or) JNK activation [31,32]. Recently Shraga et al. [33] reported irreversible MKK7 inhibitors based on an indazole acrylamide scaffold. The observation that a naphthoquinone derivative, NSC 95397, is an inhibitor of MKK7 [14] makes the 1,4-naphthoquinone scaffold also attractive for development of MKK7 inhibitors.

Although several studies have attempted to improve the naphthoquinone scaffold regarding Cdc25 inhibitory activity [34-38], there are no comprehensive reports on structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis and molecular modeling of naphthoquinone derivatives targeting MKK7 and Cdc25. In the present study, 33 naphthoquinones, including synthetic and naturally occurring compounds, were evaluated for their inhibition/binding activity for Cdc25 A/B and MKK7. To provide insights into their possible binding interaction, we also performed molecular docking studies into MKK7 and Cdc25B. Twenty selected compounds were evaluated for their in vitro antiproliferative activities against nine human tumor cell lines and primary human mononuclear cells using sunitinib as a positive control. We report for the first time that plumbagin, a natural naphthoquinone, has a high inhibitory activity for Cdc25A and B and that compounds 7 and 22e have relatively high binding affinities for MKK7 but not for MKK4.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Screening compounds

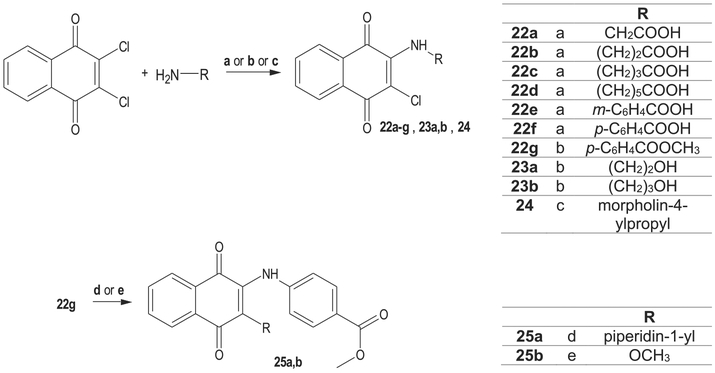

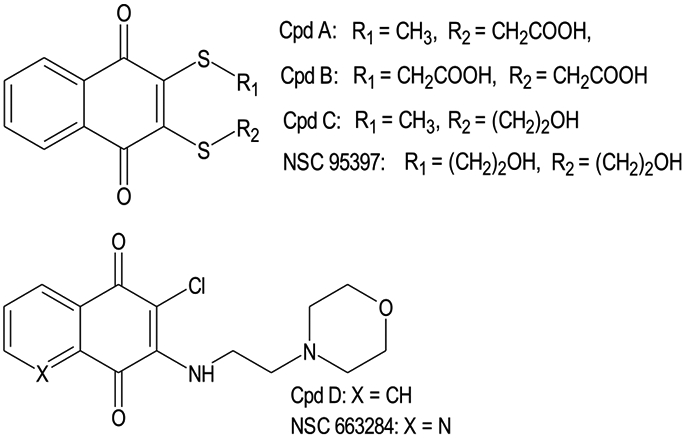

Two main classes of Cdc25 inhibitors with naphthoquinone and quinolinedione scaffolds have been reported, including sulfur-containing analogs and amino derivatives (Scheme 1). Among these compounds, NSC 95397 was previously reported as a potent Cdc25B inhibitor and a weak MKK7 inhibitor [14,17]. Based on structures of these compounds, natural and synthetic naphthoquinones with different substituents mainly at positions 2 and 3 of the 1,4-naphthoquinone scaffold were selected. These analogs included known naphthoquinones, such as shikonin (1), plumbagin (2), lapachol (3), Cpd C (5; shown in Scheme 1), vitamin ks-II (9), GN25 (14), buparvaquone (21), and menadione (18). Twelve compounds with nitrogen in the R2 position (22a-g, 23a,b, 24, and 25a,b) were designed as analogs of NSC 663284 (Scheme 1) and synthesized, as described below. All compounds were diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 10 mM and stored at −20 °C.

Scheme 1.

Reported naphthoquinone-based sulfur-containing analogs and amino derivatives with Cdc25 inhibitory activity [14,17,38].

2.2. Chemistry

New compounds (22a-g, 23a,b, 24, and 25a,b) were synthesized with high yields via condensation of 2,3-dichloro-1,4-naphthoquinone with amino-compounds in boiling ethanol (aqueous) or methanol in the presence of base (CH3COONa, CaCO3 or amine excess) [38-41]. Further transformations of 22g were achieved as described [40] or, in an analogous way, via condensation with nucleophilic components under basic conditions (Scheme 2). The compounds were characterized by their physical, analytical, and spectral data (MP, mass-spectroscopy and NMR).

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions for compound synthesis. (a) 22a-f: CaCO3, 50% EtOH, boiling, 10 h, 80% yield; (b) 22g, 23a, b: CH3COONa, 50% EtOH, boiling, 12 h, 80% yield; (c) 24: 2 mol. 3-morpholin-4-yl-propylamine, EtOH, boiling, 16 h, 95% yield; (d) 25a: 12 mol piperidine, CH3OH, boiling, 20 h, 51% yield; (e) 25b: 2 mol CH3ONa, CH3OH, boiling, 4 h, 64% yield.

The mass-spectra of most compounds contained molecular ions that had a chlorine profile (with the exception of des-chlorinated 25a,b and 24 with weak molecular ions). The main degradation paths under MS/EI conditions were: decarboxylation for carboxylic acids (highest for aromatic acids) and loss of aliphatic sidechains with m/z = 220 splinter ion formation. All of the expected signals according to molecular structure and symmetry were found in the 1H NMR spectra. Aromatic signals were present at 7–8 ppm, and their quantity, intensity, and multiplicity were in accordance with calculated results. Common N–H group signals were present at 7.2–7.5 ppm, with the exception of 22b (6.6 ppm) and Ar–NH–Ar compounds (8.4–9.5 ppm). COOH group signals were present at 12–13 ppm. The most expressed and common feature of 13C NMR spectra was the presence of three signals at 170–180 ppm, which are from inequivalent C═O groups, with the exception of 23a,b, 24, which have only two such groups.

2.3. Activity of the naphthoquinones for MKK7

All compounds were evaluated for their ability to bind to MKK7 and compared with binding of NSC 95397 (compound 4), and the Kd values are presented in Table 1. The results demonstrated that the naphthoquinone nucleus with a sulfur atom in its side chain is an appropriate scaffold for MKK7 inhibitor development. Compound 7 was the most potent MKK7 inhibitor (Kd ~230 nM). Reference naphthoquinone derivative NSC 95397 had a Kd in the micromolar range, which is in agreement with Yang et al. [14], who reported that the compound was a weak MKK7 inhibitor. Likewise, natural compound plumbagin (2) and compounds 9 and 11 exhibited binding affinity for MKK7, although in the micromolar range (Kd ~14–15 μM). In contrast, natural compounds shikonin (1) and lapachol (3), as well as menadione (18) and buparvaquone (21), did not bind to MKK7. Although no clear SAR emerged from modifications in this series, several important observations were useful. As shown in Table 1, elimination of the methyl group in 9 led to a potent MKK7 inhibitor (compound 7). The same result was obtained by elongation of the spacer between the sulfur and carboxyl groups by one methylene group (compound 6). Substitution of both SCH3 groups in compound 13 (Kd = 4.6 μM) with OCH3 groups (compound 15) was associated with almost complete loss of binding affinity. Introduction of two OCH3 groups at positions 5 and 8 of the 1,4-naphthoquinone scaffold in the most potent compound 7 also led to inactive compound 14. Among amino-derivatives at the R2 position, only 22e exhibited good binding affinity toward MKK7 (Kd = 1.9 μM). Thus, MKK7 binding activity may be very sensitive to small modifications of substituents at positions 2 and 3 of the 1,4-naphthoquinone scaffold.

Table 1.

Structure and activity of natural and synthetic naphthoquinone derivatives toward MKK7, Cdc25A, Cdc25B, and human neutrophil elastase (HNE).

|

|

|

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shikonin (1) |

Plumbagin (2) |

3-13, 15-25a,b |

14 |

|||

| Compd. | R1 | R2 | Kd (μM) vs MKK7 | Cdc25A | Cdc25B | HNE |

| IC50 (μM) | ||||||

| 1 | – | – | N.B. | 0.22 ± 0.08 | 0.4 ± 0.05 | N.A. |

| 2 | – | – | 14.0 ± 1.4 | 0.7 ± 0.14 | 3.1 ± 0.6 | N.A. |

| 3 | OH | CH2CHC(CH3)2 | N.B. | 33.2 ± 3.2 | 42.7 ± 11.7 | N.A. |

| 4 | S(CH2)2OH | S(CH2)2OH | 1.1 ± 0.35 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 0.78 ± 0.17 | N.A. |

| 5 | S(CH2)2OH | CH3 | N.B. | 4.5 ± 1.4 | 10.9 ± 2.5 | N.A. |

| 6 | SCH2COOH | H | 1.4 ± 0.35 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 1.0 ± 0.35 | N.A. |

| 7 | S(CH2)2COOH | H | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | N.A. |

| 8 | S(CH)CH3COOH | H | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 36.1 ± 3.7 |

| 9 | S(CH2)2COOH | CH3 | 15.0 ± 2.1 | 5.1 ± 1.7 | 6.7 ± 0.8 | N.A. |

| 10 | SCH2CH3 | CH3 | 13.0 ± 1.4 | 5.5 ± 1.4 | 4.7 ± 1.7 | N.A. |

| 11 | S(CH2)2OCH3 | CH3 | 14.0 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 6.5 ± 1.1 | N.A. |

| 12 | SCH(CH3)2 | CH3 | 13.0 ± 3.5 | 6.3 ± 1.9 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | N.A. |

| 13 | SCH3 | SCH3 | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | N.A. |

| 14 | – | – | N.B. | 26.0 ± 6.3 | 7.8 ± 2.3 | N.A. |

| 15 | OCH3 | OCH3 | 27.0 ± 1.4 | 8.9 ± 3.4 | 17.4 ± 3.4 | N.A. |

| 16 | OCH3 | H | N.B. | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 46.8 ± 4.2 | N.A. |

| 17 | OCH3 | CH3 | N.B. | 22.3 ± 3.8 | 33.1 ± 9.7 | N.A. |

| 18 | CH3 | H | N.B. | 6.9 ± 1.8 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | N.A. |

| 19 | CH2N(CH2CH2Cl)2 | OH | N.B. | 15.4 ± 3.0 | 12.7 ± 2.6 | N.A. |

| 20 | C(CH2)2OH | OH | N.B. | 25.9 ± 4.3 | 18.7 ± 4.6 | N.A. |

| 21 | A | OH | N.B. | N.A. | 12.0 ± 3.3 | N.A. |

| 22a | Cl | NHCH2COOH | N.B. | 36.0 ± 2.1 | N.A. | N.A. |

| 22b | Cl | NH(CH2)2COOH | N.B. | 26.1 ± 0.4 | 28.8 ± 5.1 | N.A. |

| 22c | Cl | NH(CH2)3COOH | N.B. | 8.2 ± 2.6 | 10.9 ± 2.7 | N.A. |

| 22d | Cl | NH(CH2)5COOH | N.B. | 36.4 ± 8.6 | 23.7 ± 4.2 | N.A. |

| 22e | Cl | B | 1.9 ± 0.28 | 32.9 ± 3.7 | 24.3 ± 4.3 | N.A. |

| 22f | Cl | C | N.B. | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 1.8 | N.A. |

| 22g | Cl | D | N.B. | 20.3 ± 4.5 | 10.9 ± 3.1 | N.A. |

| 23a | Cl | NH(CH2)2OH | N.B. | 45.3 ± 1.6 | N.A. | N.A. |

| 23b | Cl | NH(CH2)3OH | N.B. | 45.7 ± 0.9 | N.A. | N.A. |

| 24 | Cl | E | N.B. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 25a | 1-piperidyl | C | N.B. | 11.6 ± 0.9 | 14.2 ± 3.8 | N.A. |

| 25b | OCH3 | C | N.B. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

N.B., no binding at concentrations <30 μM; N.A., no inhibitory activity at concentrations <50 μM.

The most potent naphthoquinone derivatives that targeted MKK7 (4, 6–8, and 22e) were also evaluated for their ability to bind to MKK4, another kinase that can phosphorylate JNK [42]. No MKK4 binding affinity was found for 4, 7, 8, and 22e, whereas low binding affinity was found for compound 6 (Kd = 19.5 ± 0.7 μM) (data not shown).

We also tested six 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinazoline and quinazolin-4(3H)-one analogs of compound 7 with similar or related R1 tail substituents but did not find any binding affinity for MKK7 (Supplementary Table 1S). These results indicate that the presence of the naphthoquinone moiety is critical for biological activity, possibly due to the hydrophobic properties of this molecular fragment and/or specific location of the two H-bond acceptors (carbonyl groups). It should be noted that p-naphthoquinones are prone to reduction, with the formation of semiquinone anion radicals. In contrast, 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinazoline derivatives have a structure that does not lead to effective resonance stabilization of a radical [43].

2.4. Molecular docking of selected naphthoquinones with MKK7

To provide insights into possible binding interaction of MKK7 inhibitors, we performed molecular docking studies of selected naphthoquinone derivatives 4 (reference compound NSC 95397), 6, 7, 22e, and 22f into the binding site of human MKK7 (PDB code 2DYL) (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Docking calculations gave the best poses of compounds 6 and 7, where they formed H-bonds by their quinone oxygen atoms with the NH group of Met215 and the SH group of Cys276. The carboxyl group of 6 and 7 formed a H-bond with Lys165 and Asp277, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2). The presence of an additional methylene group in 7 compared to 6 led to some differences in the binding modes for these two molecules. Indeed, compound 7 is 6-fold more active than 6. Conversely, elongation of the spacer between the sulfur and carboxyl group by one more methylene group compared to 7 led to breaking of the H-bond between the naphthoquinone carbonyl and Cys276, while H-bonding of another naphthoquinone carbonyl to Met215 became much weaker. Thus, our modeling experiments suggest that the length of side chain in 7 could be optimal for supporting MKK7 inhibitory activity. Regarding compound 4, both oxygen atoms of the quinone moiety in molecule are also H-bonded to Cys276 and Met215. In addition, the terminal OH groups in 4 form H-bonds with Glu213 and Asp277 (Supplementary Fig. S3).

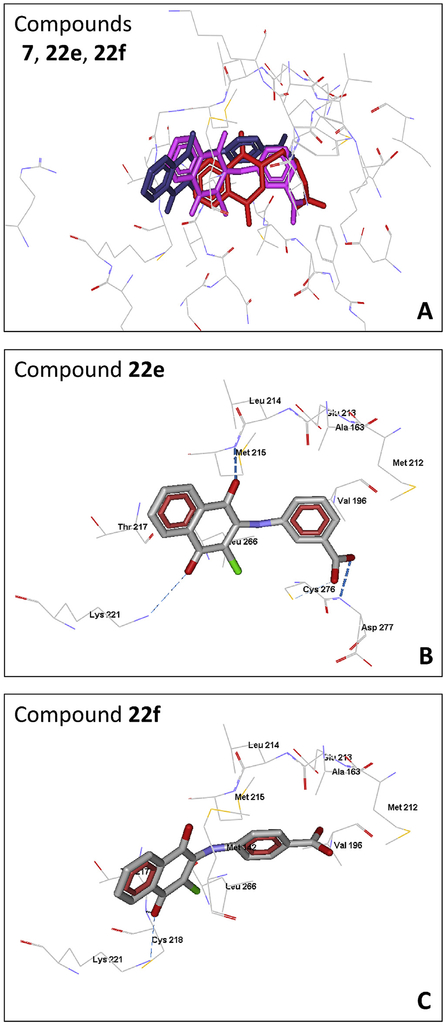

In the pair of novel molecules 22e and 22f, which contain a carboxyl group in the benzene ring, the naphthoquinone moieties are displaced in their docking poses relative to molecules 4, 6, and 7, especially for inactive compound 22f (Fig. 1A). Despite the displacement of 22e relative to 7, the positions of their carboxyl groups almost coincide. The active compound 22e forms rather strong H-bonds with Asp277 and Met215, as well as somewhat weaker H-bonds with Cys276 and Lys221 (Fig. 1B). Thus, molecule 22e interacts with Met215, Cys276, and Asp277, which presumably play a key role in the binding activity. Unlike 22e, the inactive 22f is not H-bonded to any of these residues (Fig. 1C) but forms only a weak H-bond with Lys221 and a stronger bond with Cys218. Obviously, the carboxyl group in the para position of the benzene ring of molecule 22f cannot stretch to the “important” Cys276 and Asp277. In addition, the para-carboxyl group, due to steric hindrances, causes a noticeable displacement of 22f. As a result of this displacement, H-bonding of the quinone carbonyl oxygen atom with the key Met215 becomes impossible. Thus, our docking results satisfactorily explain the observed binding activities of these substituted naphthoquinones.

Fig. 1.

Docking poses of selected naphthoquinones in the MKK7 binding site. Superimposition of docking poses of 7 (red), 22e (magenta), and 22f (violet) (Panel A). Separate poses are shown for compounds 22e (Panel B), and 22f (Panel C). For all panels, except Panel A, residues within 3 Å of each pose are visible. For Panel A, residues within 6 Å of the cavity are visible. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Shraga et al. [33] recently reported that the MKK7 binding site is surrounded by Leu266, Val196, Met212, Ala163, Val150, Cys276, and Cys218. Six of these residues are present in the nearest vicinity of the docking poses reported here, although they performed covalent docking of acrylamides, which cannot be directly compared with the results of our non-covalent docking. Nevertheless, the ligand-receptor complexes modelled by us might be suitable starting structures for subsequent covalent interaction of the naphthoquinones with MKK7, e.g. with Cys276. This issue needs further investigation.

2.5. Activity of the naphthoquinones toward Cdc25A and Cdc25B

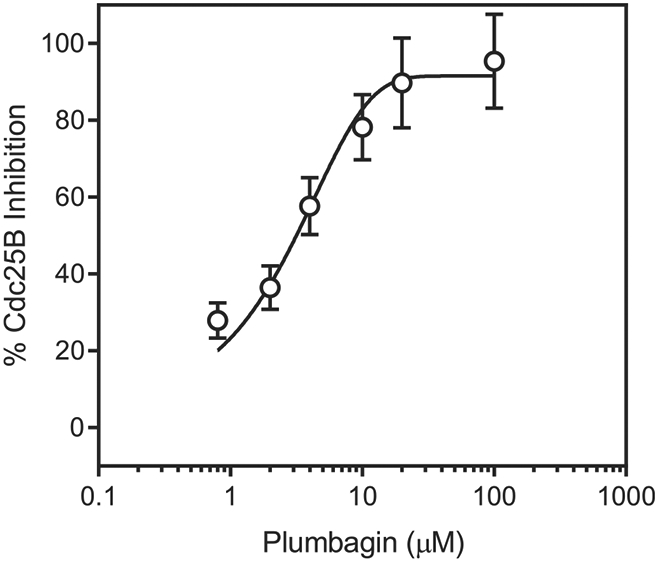

Most of the known inhibitors of Cdc25 phosphatases are quinone-based derivatives (e.g., Refs. [5,6]). Thus, the naphthoquinones under investigation were also examined for their effects on Cdc25 A/B activity. Our set of the compounds included shikonin (1), NSC 95397 (4), Cpd C (5), and menadione (18), which were previously reported as inhibitors of Cdc25 [6,17,34,44-46]. IC50 values for inhibition of Cdc25A and B are presented in Table 1. Compounds 6–13, 22f, and plumbagin (2), together with the reference compounds 1, 4, 5, and 18, were the most potent Cdc25 A/B inhibitors. As an example, the dose-dependent inhibition of Cdc25B by plumbagin (2) is shown in Fig. 2. Plumbagin (2) was even more active than menadione (18), which lacks a hydroxyl group. Compounds 6–13 are related sulfur-contained analogs of known Cdc25 inhibitors 4 and 5. Compound 24 with a high degree of similarity to the structure of NSC 663284, a potent Cdc25 inhibitor [44], was inactive. IC50 values for inhibition of Cdc25A versus inhibition of Cdc25B had a good linear correlation (r = 0.83) with one exception (compound 16), suggesting that almost all inhibitors targeted both Cdc25A and Cdc25B. Although there are many publications on the anticancer activity of plumbagin (e.g., Ref. [47]), this is a first report that this natural compound inhibits Cdc25A and B.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of Cdc25B by plumbagin. Cdc25B was incubated with the indicated concentrations of plumbagin, and cleavage of the fluorogenic phosphatase substrate (3-O-methyl fluorescein phosphate) was monitored, as described under Materials and Methods. The data are presented as the mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples from a representative experiment of two independent experiments.

To evaluate inhibitory specificity, we analyzed the effects of the naphthoquinones on activity of human neutrophil elastase (HNE), a member of the chymotrypsin family of serine proteases. All compounds, except one (compound 8) had no HNE inhibitory activity (Table 1).

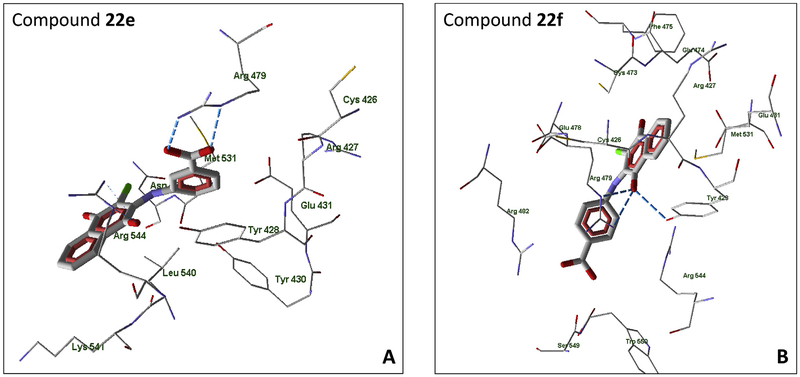

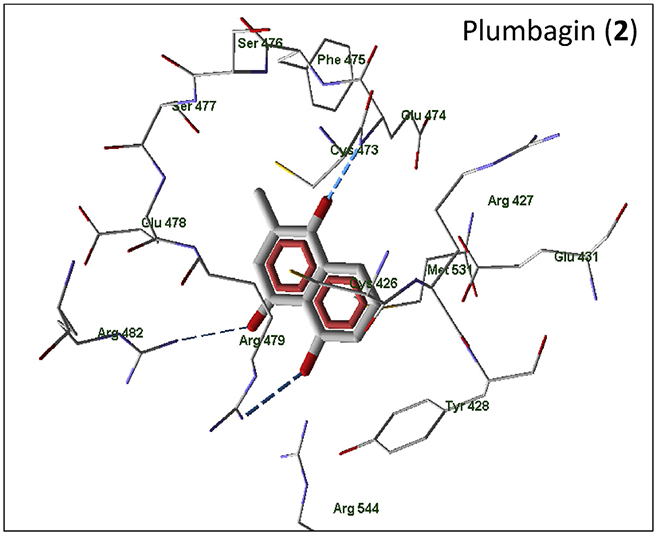

2.6. Molecular docking of selected naphthoquinones with Cdc25B

We performed molecular docking of selected naphthoquinones (1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 13, 15, 22e, and 22f) into Cdc25B (PDB code 1QB0). The binding site is located near Cys473 and Tyr428 and corresponds to one of the three binding sites (also designated as “active sites”) suggested by docking and molecular dynamics simulations [48]. Previously, it was reported that Cys473 is catalytically essential for substrate activation, and inhibition of Cdc25B activity can occur by the oxidation of Cys473 through ROS production [22,49]. Thus, Cys473 was specified as the ligand reactive group (see also [6]), and docking of various ligands to this site was carried out previously [6,48].

Our docking studies with Cdc25B were performed with the use of the ROSIE server [50] and accounted for full flexibility of both ligand and the closest amino acid residues within the Cdc25B binding site. Supplementary Table S2 shows the distances obtained between the closest heavy (i.e., non-hydrogen) atoms of Cys473 and the ligand. Energies for the interaction of a ligand with Cys473 and Tyr428 (partial docking scores) are also presented. Tyr428 was mentioned earlier as one of the important residues in a docking study of shikonin [6]. Due to the larger size of tyrosine, the partial docking scores related to Tyr428 are higher than those for Cys473 since they include van der Waals interactions with each of the atoms of the amino acid residue. In addition, most active compounds form H-bonds or participate in π-π stacking interactions with Tyr428.

All of the active compounds are located within the binding site near Cys473, which is favorable for electron transfer from the cysteine sulfur atom to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the naphthoquinone moiety. It should be noted that the docking pose of shikonin is in agreement with the results of Zhang et al. [6]. This ligand is connected to the binding site due to H-bonding of Tyr428 and Arg479 with the OH group and carbonyl oxygen in the naphthoquinone moiety. In addition, Arg479 forms an H-bond with the hydroxyl group of the shikonin side chain. The location of plumbagin, another natural naphthoquinone, within the binding site is shown in Fig. 3. Plumbagin forms H-bonds with Glu474 and Arg482 due to quinone carbonyl groups, as well as an H-bond to Arg479 with the participation of the phenolic hydroxyl group. The less active compound 15 is anchored at a distance >7 Å from Cys473 due to H-bonding of quinone carbonyl groups to Arg482 and Arg544 (Supplementary Table S2). Naphthoquinone 13, which is a sulfur-containing analogue of 15, also forms an H-bond between one of the quinone oxygen atoms and Arg482 in its best docking pose (Supplementary Fig. S4). It should be noted that in the docking pose of 13, a cation-π interaction may occur between the charged Arg479 and the closely located π-electron system of the ligand. In addition, a π-π interaction between the naphthoquinone and Tyr428 benzene rings is possible; the distance between the centers of the rings is 4.00 Å, while the distance between their planes is about 3.2 Å. A similar π-π stacking with Tyr428 was previously considered for quinolinedione NSC 663284 [48]. Arg479 is involved in H-bonding to the quinone oxygen atom of molecule 4 (Supplementary Fig. S5). The possibility of Tyr428 π-π interaction with the ligand was also found for naphthoquinones 6 and 7 (Supplementary Fig. S6). Molecule 6 forms H-bonds with Arg482 and Arg544, with the participation of a quinone oxygen atom, as well as with Glu478 and Arg482, with the participation of the carboxyl group. Compound 7 has a similar orientation within the binding site; there is an H-bond between the quinone oxygen atom and Arg482, while the carboxyl group forms H-bonds with Glu474, Phe475, and Ser477.

Fig. 3.

Docking poses of plumbagin (compound 2) in the Cdc25B binding site. Residues within 4 Å of the pose are shown.

According to our docking results, derivatives 22e and 22f, which contain a carboxyl-substituted phenylamine fragment, are differently oriented within the Cdc25B binding site. Molecule 22e forms strong H-bonds via two oxygen atoms of the carboxyl group with Arg479 (Fig. 4). In addition, there is a π-π interaction of the carboxyl-substituted benzene ring in 22e with Tyr428. As a result, 22e is anchored far from the key Cys473. A carboxyl group in the para-position of the benzene ring in 22f does not have the possibility for similar effective H-bonding to Arg479. Compound 22f is located in the binding site such that Arg479 forms H-bonds with a quinone carbonyl group and simultaneously participates in cation-π interaction with the benzene ring of the phenylamino substituent. There is also an additional strong H-bond between Tyr428 and the naphthoquinone carbonyl group. These interactions facilitate location of 22f in the vicinity of Cys473, which is consistent with its higher biological activity compared to 22e. It should be noted that an orientation of 22e inside the binding site similar to molecule 22f would be very difficult due to a steric repulsion of the ligand carboxyl group in the meta-position from Arg482 and Arg544.

Fig. 4.

Docking poses of naphthoquinones 22e and 22f in the Cdc25B binding site. For both panels, residues within 4 Å of each pose are shown.

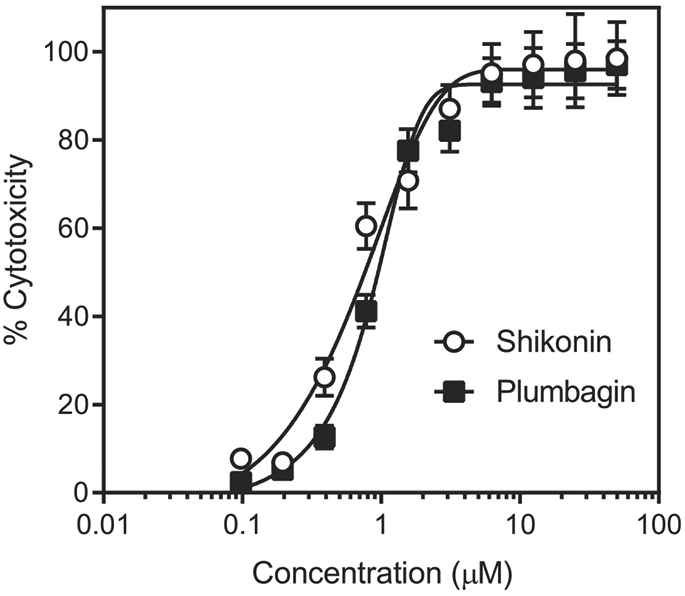

2.7. Anticancer cell activity of selected naphthoquinones

Twenty selected naphthoquinone derivatives were tested for their in vitro anticancer activity against a panel of nine tumor cell lines and primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in comparison with sunitinib, a known anticancer drug. The human cancer cell lines used were lung carcinoma (A549), synovial sarcoma (SW-982), breast adenocarcinoma (MCF7), colorectal adenocarcinoma (LS-174t), monocytic leukemia (THP-1, Mono-Mac6, U937), promyelocytic leukemia (HL60), and leukemic Jurkat T cells. The cells were treated with the selected compounds for 24 h at different concentrations (up to 50 μM).

The selected compounds displayed moderate to strong cytotoxic activity against the tested cancer cell lines (Table 2). For most of the cell lines, the greatest cytotoxic activity (IC50 < 10 μM) was found for compounds 1, 2, 4, 9–13, 18, 22e, and 22f. Furthermore, cytotoxicity of many compounds was even higher in comparison with the reference compound sunitinib. As an example, the concentration-dependent effect of shikonin (1) and plumbagin (2) on viability of HL60 cells is shown in Fig. 5. Compound 13 was 2- to 8-fold more toxic than 15 in seven of the cell lines, indicating that substitution of oxygen with sulfur atoms in R1/R2 could increase biological activity. The slightly higher hydrophobicity of 13 (LogP = 2.83) may contribute to its enhanced cytotoxicity versus 15 (LogP = 1.29). Although lapachol was previously found to be active against Walker-256 carcinoma and Yoshida sarcoma [51], we did not find any toxicity for this compound against all 9 tumor cell lines tested or the primary PBMCs (Table 2). Similarly, 14, a known inhibitor of Snail-p53 binding [9], was weakly toxic or nontoxic for the tumor cell lines and PBMCs. It should be noted that 22e exhibited good selectivity against SW-982 synovial sarcoma cells, as compared to PBMCs. Interestingly, there was a definite linear correlation between activity of the compounds toward Cdc25 A/B and anticancer cell activity for most of the tested cell lines, whereas no correlation was found between cancer cell line cytotoxicity and binding affinity for MKK7 (Table 3). However, this tendency could also reflect an ability of naphthoquinones to generate ROS and(or) their redox potential. Indeed, both inhibitory activity of naphthoquinones toward Cdc25 A/B and anticancer cell activity are determined by redox potentials of the compounds [52]. Although 6 was weakly active or inactive against all eight tumor cell lines and primary PBMCs, it had strong cytotoxic activity against Jurkat T cells (IC50 = 0.94 μM). Thus, the mechanism of selective cytotoxicity of 6 in Jurkat T cells should be further investigated.

Table 2.

Anticancer cell cytotoxicity of selected naphthoquinones versus nine cancer cell lines and primary mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

| Compd. | THP-1 | MonoMac6 | HL60 | SW-982 | Jurkat | U936 | MCF7 | LS174T | A549 | PBMCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM) | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0.82 ± 0.26 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 0.97 ± 0.05 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 8.9 ± 2.5 | 7.3 ± 2.2 | 5.0 ± 1.4 |

| 2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 0.95 ± 0.23 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 9.9 ± 3.2 | 7.2 ± 1.6 | 2.7 ± 1.1 |

| 3 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 4 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 2.5 | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 3.9 ± 1.2 | 9.4 ± 2.9 | 18.1 ± 4.8 | 13.1 ± 3.3 | 7.8 ± 2.7 |

| 5 | 3.9 ± 1.2 | 6.3 ± 1.5 | 9.3 ± 2.8 | 19.3 ± 2.4 | 6.8 ± 2.1 | 12.1 ± 2.2 | 30.9 ± 1.6 | 39.4 ± 7.4 | 41.3 ± 6.4 | 13.3 ± 3.1 |

| 6 | N.T. | 23.2 ± 7.5 | 20.4 ± 3.6 | 11.1 ± 2.2 | 0.94 ± 0.05 | 15.9 ± 3.6 | 16.5 ± 4.2 | N.T. | 22.9 ±4.7 | N.T. |

| 7 | 17.6 ± 0.7 | 22.0 ± 6.1 | 15.0 ± 3.9 | 10.5 ± 1.3 | 9.1 ± 2.4 | 18.6 ± 3.8 | 18.1 ± 2.2 | N.T. | N.T. | 23.4 ± 5.6 |

| 8 | N.T. | 43.6 ± 11.2 | 20.5 ± 4.6 | 21.1 ± 4.3 | 17.9 ± 2.9 | 34.6 ± 4.3 | 27.9 ± 4.4 | N.T. | N.T. | 23.8 ± 5.3 |

| 9 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 6.4 ± 1.8 | 7.5 ± 2.1 | 5.7 ± 1.9 | 10.0 ± 2.6 | 21.6 ± 3.8 | 31.9 ± 7.2 | 37.3 ± 5.4 | 10.3 ± 2.1 |

| 10 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 7.8 ± 1.7 | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 6.7 ± 2.1 | 12.2 ± 1.9 | 17.3 ± 3.6 | 21.5 ± 3.8 | 5.6 ± 1.3 |

| 11 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 9.7 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 14.9 ± 2.6 | 15.7 ± 4.1 | 18.6 ± 3.6 | 6.2 ± 1.4 |

| 12 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 12.8 ± 3.6 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 8.9 ± 2.1 | 16.8 ± 4.1 | 20.8 ± 3.4 | 24.0 ± 7.3 | 8.9 ± 2.4 |

| 13 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 7.6 ± 1.3 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 2.3 | 15.1 ± 4.4 | 12.4 ± 2.5 | 2.4 ± 0.8 |

| 14 | 33.3 ± 8.7 | 12.8 ± 3.5 | 28.7 ± 3.7 | N.A. | 21.3 ± 4.5 | 26.6 ± 6.6 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 15 | 8.2 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 20.6 ± 3.8 | 11.5 ± 2.1 | 11.3 ± 3.8 | 6.3 ± 1.6 | 27.9 ± 6.7 | 15.6 ± 3.1 | 18.5 ± 1.5 |

| 16 | 16.6 ± 3.8 | 4.8 ± 0.9 | 7.1 ± 2.1 | 29.8 ± 5.7 | 16.1 ± 3.1 | 13.9 ± 3.2 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 33.7 ± 6.4 | 16.4 ± 3.3 | 29.8 ± 6.2 |

| 17 | 47.3 ± 8.4 | 18.4 ± 3.8 | 20.4 ± 2.6 | N.A. | 49.2 ± 7.2 | 35.1 ± 7.6 | 21.4 ± 5.2 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 18 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 6.2 ± 1.7 | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 9.3 ± 1.6 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 9.0 ± 2.3 | 26.6 ± 2.5 | 25.1 ± 4.2 | 14.5 ± 3.2 |

| 22e | 8.6 ± 0.3 | 13.4 ± 5.2 | 12.1 ± 1.9 | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 8.2 ± 0.8 | 7.6 ± 2.1 | 28.5 ± 3.5 | 11.7 ± 3.3 | 26.2 ± 6.2 | 37.9 ± 9.4 |

| 22f | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 6.0 ± 1.6 | 8.9 ± 2.3 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 14.5 ± 0.9 | 9.9 ± 2.3 | 17.6 ± 3.6 | 13.1 ± 2.6 |

| Sunitinib | 14.9 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 1.3 | 21.5 ± 3.9 | 41.2 ± 4.7 | 8.5 ± 2.1 | 13.7 ± 2.9 | 6.8 ± 1.3 | N.T. | 22.1 ± 4.9 | 46.3 ± 16.4 |

IC50 values were calculated from three independent experiments. N.A, no cytotoxic activity at concentrations <50 μM.

Fig. 5.

Anticancer cell cytotoxicity of plant-derived naphthoquinones shikonin (1) and plumbagin (2). HL60 cells were incubated with the indicated naphthoquinones for 24h, and cell viability was measured, as described. The data are presented as the mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples from a representative experiment of three independent experiments.

Table 3.

Results of pairwise regression analysis of reciprocal cytotoxicity values (1/IC50) for nine human cancer cell lines and PBMCs vs reciprocal values for MKK7 and Cdc25 A/B phosphatase inhibitory activity (1/Kd and 1/IC50, respectively) of the tested naphthoquinones.

| Activity | THP-1 | MonoMac6 | HL60 | SW-982 | Jurkat | U936 | MCF7 | LS174T | A549 | PBMCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson correlation coefficient r (p value) | ||||||||||

| MKK7 | −0.14 (n.s.) | −0.28 (n.s.) | −0.09 (n.s.) | 0.03 (n.s.) | 0.07 (n.s.) | −0.15 (n.s.) | −0.14 (n.s.) | −0.08 (n.s.) | −0.25 (n.s.) | −0.14 (n.s.) |

| Cdc25A | 0.80 (***) | 0.31 (n.s.) | 0.57 (*) | 0.76 (***) | 0.76 (***) | 0.87 (***) | 0.85 (***) | 0.56 (*) | 0.70 (**) | 0.63 (**) |

| Cdc25B | 0.71 (**) | 0.38 (n.s) | 0.76 (***) | 0.62 (**) | 0.66 (**) | 0.79 (***) | 0.67 (**) | 0.36 (n.s.) | 0.57 (*) | 0.30 (n.s.) |

Statistical significance at p < 0.05 was determined using the Prism software.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001, n.s.: non-significant.

2.8. Density functional theory (DFT) study

We performed DFT analysis of selected naphthoquinone derivatives to identify characteristics of their electronic structure related to anticancer cell activity/cytotoxicity and enzyme inhibitory activity. Geometry optimizations were performed with the BP86 functional, triple-zeta basis set def2-TZVPP. This level of theory provides high-quality results for molecular geometries and was previously validated on several hundred organic molecules [53]. Subsequent single-point calculations were then made for each compound with the ωB97X-D3 functional and the largest Pople basis set 6–311++G(3df,3pd) in order to obtain better results for orbital energies [54].

We chose the following characteristics of electronic structure for further analysis: energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital [E(HOMO)], energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital [E(LUMO)], vertical electron affinity (VEA), absolute hardness η, absolute electronegativity χ, and reactivity index ω. Values of η, χ, and ω were calculated according to equations (1)-(3) [55,56]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Although the ωB97X-D3 functional presumably leads to more correct electronic structures, for comparison purposes we also considered the electronic properties calculated with the BP86 functional, as they were available from the geometry optimization runs. The magnitudes obtained at the BP86/def2-TZVPP level of theory are denoted here by subscript “BP86” (e.g. E(LUMO)BP86, χBP86, etc). The electronic characteristics for the investigated compounds are presented in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 together with estimated LogP values. All of these characteristics were used as variables for pairwise correlation analyses vs cytotoxic activity, the latter being expressed in a reciprocal scale (1/IC50) where inactive compounds were assigned a value of 0. The correlation coefficients obtained are shown in Table 4 and Supplementary Table 5S. The purpose of the correlation analysis was to establish how tightly the cytotoxic activity was associated with main characteristics of electronic structure and LogP of the investigated naphthoquinones.

Table 4.

Results of pairwise regression analysis of reciprocal cytotoxicity values for nine human cancer cell lines and PBMCs vs Log P and electronic properties calculated using ωB97X-D3 functional for the investigated naphthoquinones.

| Descriptor | THP-1 | MonoMac6 | HL60 | SW-982 | Jurkat | U936 | MCF7 | LS174T | A549 | PBMC | Cdc25A | Cdc25B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson correlation coefficient r (p value) | ||||||||||||

| E(LUMO) | −0.53 (*) | −0.13 (n.s.) | −0.25 (n.s.) | −0.81 (***) | −0.66 (**) | −0.69 (**) | −0.6 (**) | −0.56 (*) | −0.54 (*) | −0.3 (n.s.) | −0.77 (***) | −0.40 (n.s.) |

| E(HOMO) | 0.26 (n.s.) | 0.22 (n.s.) | 0.35 (n.s.) | 0.12 (n.s.) | 0.02 (n.s.) | 0.21 (n.s.) | −0.11 (n.s.) | 0.24 (n.s.) | 0.08 (n.s.) | 0.25 (n.s.) | 0.15 (n.s.) | 0.33 (n.s.) |

| VEA | 0.51 (*) | 0.14 (n.s) | 0.27 (n.s.) | 0.80 (***) | 0.61 (**) | 0.67 (**) | 0.50 (*) | 0.58 (**) | 0.49 (*) | 0.30 (n.s) | 0.62 (**) | 0.30 (n.s.) |

| η | −0.49 (*) | −0.26 (n.s.) | −0.43 (n.s.) | −0.51 (*) | −0.34 (n.s.) | −0.52 (*) | −0.2 (n.s.) | −0.49 (*) | −0.34 (n.s.) | −0.37 (n.s.) | −0.40 (n.s.) | −0.49 (*) |

| χ | 0.03 (n.s.) | −0.13 (n.s.) | −0.19 (n.s.) | 0.29 (n.s.) | 0.30 (n.s.) | 0.15 (n.s.) | 0.38 (n.s.) | 0.06 (n.s.) | 0.19 (n.s.) | −0.07 (n.s.) | 0.32 (n.s.) | −0.10 (n.s.) |

| ω | 0.45 (*) | 0.06 (n.s.) | 0.14 (n.s.) | 0.75 (***) | 0.62 (**) | 0.63 (**) | 0.63 (**) | 0.48 (*) | 0.51 (*) | 0.21 (n.s.) | 0.76 (***) | 0.62 (**) |

Statistical significance was determined using Prism software:

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001, n.s.: non-significant. All statistically significance values are shown in bold font.

According to the molecular orbital theory of chemical reactivity, a lower E(LUMO) means the compound more easily accepts electrons in chemical reactions and thus plays a role as an electrophilic reagent [57,58]. We found that all compounds involved in our DFT study were soft electrophiles, as defined by a level of E(LUMO) lower than 2.5 eV and that the E(LUMO) affects their cytotoxic activities toward SW-982, Jurkat T cells, and U936 cells. A negative correlation coefficient for E(LUMO) indicates that decreasing E(LUMO) values can increase the 1/IC50 as a measure of cytotoxic activity. Therefore, we can reasonably speculate that the naphthoquinones act as electron acceptors upon interaction with a target, and electron transfer occurs from the target to the compound. It should be noted that the importance of E(LUMO) for the cytotoxicity of amides of pyrazine-2-carboxylic acid was previously shown by Hosseini et al. [57]. However, for a group of celastroid triterpenoids, it was found that cytotoxicity correlated better with E(HOMO) than with E(LUMO) [59], although the author postulated that these triterpenoids undergo a nucleophilic attack associated with their biological action.

Tendency of a molecule to accept an electron and form an anion radical can be directly characterized by electron affinity. We calculated values of vertical electron affinities (VEA and VEABP86) as energy differences between an anion radical and a corresponding neutral naphthoquinone. Both species were taken at the geometry obtained in the optimization run for a neutral molecule. Satisfactory and significant positive correlations were obtained between VEA and 1/IC50 values for SW-982, Jurkat, and U963 cells, indicating again that higher electron acceptor ability of the investigated naphthoquinones favors their biological activity against these cell lines. As shown in Table 4, Supplementary Table S5, and Supplementary Figs. S7 and S8, tightness of the correlations was in general higher for E(LUMO) and VEA than for the corresponding values of E(LUMO)BP86 and VEABP86 obtained with the BP86 functional. This observation agrees with the results obtained by Lin et al. [54], which introduced the ωB97X-D3 functional as highly suitable for calculations of electronic properties, particularly orbital energies of organic compounds.

Correlations of 1/IC50 values vs E(HOMO) and HOMO-related properties (absolute hardness η and absolute electronegativity χ) were expectedly weaker, as HOMO does not participate in one-electron reduction of naphthoquinones. However, the combined characteristic ω (and also ωBP86) correlates satisfactorily with cytotoxic activity measures against SW-982, Jurkat, U963, and MCF7 cell lines. Similar results were obtained earlier for a group of vitamin K2 analogs by Ishihara and Sakagami [55], who also indicated correlation of the reactivity index ω with cytotoxicity against HSC-2, HSC-3, HSC-4, HepG2, and HL60 cells. Log P values did not provide any significant correlations with 1/IC50 values for the cancer cell lines evaluated (Supplementary Table S5).

Cdc25 phosphatases are primary targets for nucleophile attack by electrophilic molecules, such as 1,4-naphtoquinones [34-38]. Thus, we conducted pairwise correlation analysis for the molecular DFT descriptors and inhibitory activity (1/IC50) of the naphthoquinone derivatives for Cdc25 A/B. Similar to our correlation analysis regarding cytotoxicity, we found that the DFT-derived properties, including E(LUMO), VEA, absolute hardness ηBP86, and reactivity index ω, correlated with Cdc25A inhibitory activity. With Cdc25B, the correlation was found only for descriptors η, ω, and VEABP86. Negative correlation coefficients were found for LUMO energy and absolute hardness, while positive values of r were obtained for the reactivity index (Table 4 and Supplementary Table S5). These correlations indicate that high electrophilicity of the compounds would be favorable for Cdc25 A/B inhibitory activity. In other words, our modeling showed that electron transfer between the naphthoquinone molecules and Cdc25 is the most important factor contributing to phosphatase inhibition.

Thus, electronic properties associated with the possibility to accept electrons [E(LUMO), VEA] and with general chemical reactivity (ω) are the most important variables related to Cdc25 inhibition and cytotoxic anticancer cell activity of our naphthoquinone derivatives. Importance of these properties is in accordance with the general concept of donor-acceptor and nucleophile-electrophile interactions, which are to a great extent defined by the energies of frontier molecular orbitals [56]. Indeed, the high values of ω for aryl substituted flavones/flavanones and their analogs were previously found to be associated with high cytotoxic activity [60].

3. Conclusion

Synthesis and analysis of novel 1,4-naphthoquinone derivatives demonstrated that several of these compounds had high affinity for MKK7 and high inhibitory activity toward Cdc25 A/B. We report for the first time that the four naphthoquinone derivatives 6–8, and 22e and previously reported compound 4 (NSC 95397) are specific inhibitors of MKK7 vs MKK4, with the most potent compound being 7. Our modeling experiments suggest that the length of side chain in 7 could be optimal for supporting MKK7 inhibitory activity. Compounds 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 13, and 22f were potent (IC50 < 5 μM) inhibitors of Cdc25 A/B activity. Although plumbagin (2) had weak affinity for MKK7, this compound and shikonin (1) were potent inhibitors of Cdc25 A/B. Molecular docking studies revealed that all of the naphthoquinone derivatives that inhibited Cdc25 A/B bound within the enzyme binding site near Cys473, which is favorable for electron transfer from the cysteine sulfur atom to the LUMO of the naphthoquinone moiety. Although we did not find a correlation between naphthoquinone binding affinity toward MKK7 and compound cytotoxicity, there was a definite correlation between activity of the compounds toward Cdc25 A/B and cytotoxic activity against eight of the nine cancer cell lines tested. Moreover, 6 and 7 could be prototypic molecules for design of analogs with dual MKK7/Cdc25 inhibitory activity. Our DFT analysis showed that E(LUMO), VEA, and reactivity index (ω) are important electronic structure characteristics related to cytotoxicity of the naphthoquinone derivatives. Some characteristics derived from the DFT calculations also allowed us to suggest a physical explanation for electronic properties of the molecules that could contribute to Cdc25 inhibition. Finally, the analogs evaluated here could be successfully utilized for further development of efficacious Cdc25 A/B and MKK7 inhibitors with anticancer activity. The quantum chemistry modelling of electronic structure by DFT or other computational approaches can be useful for the estimation of naphthoquinone reactivity towards possible nucleophilic centers in a protein. On the other hand, docking studies can provide an additional elucidation on reachability of these centers by a ligand for electron transfer or covalent interaction within a binding site.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. General methods

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Acros Organics and were used without further purification. The melting points (in °C) were recorded in open capillaries and are uncorrected. Mass spectra were recorded by the direct inlet method on an MX 1321 mass spectrometer at 70 eV collision energy and source T = 200 °C in the EI mode. Mass spectra FAB were recorded on a VG 70-70 EQ mass spectrometer at 8 kV collision energy, using 3-NO2-benzyl alcohol as a solvent. Alugram SIL G/UV254 pre-coated thin layer chromatography (TLC) sheets were used for TLC (Macherey-Nagel) with Eluent A: benzene:acetone:acetic acid 10:1:0.1 and Eluent B: benzene:triethylamine 10:1.1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker spectrometer at 400 MHz and 100 MHz, respectively, with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard (the aromatic protons designations are presented below). For aromatic proton designations, see Supplementary Fig. S9. Representative NMR spectra for compounds 22a-g, 23a,b, 25a,b are provided in supplementary material.

4.1.2. 4-(3-Chloro-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydro-naphthalen-2-ylamino)-benzoic acid (22f)

The compound was synthetized, as described [41]. Briefly, a mixture of 2,3-dichloro-1,4-naphthoquinone (1.135 g, 5 mmol), 4-aminobenzoic acid (0.686 g, 5 mmol), and calcium carbonate (0.501 g, 5 mmol) in 50 ml of 50% ethanol was heated under reflux for 10 h (presence of 2,3-dichloro-1,4-naphthoquinone was controlled by TLC in CHCl3). The mixture was cooled to room temperature mixture and poured in 200 ml of H2O. The precipitate was filtered, washed with 1M HCl (2 × 20 ml) and H2O (2 × 30 ml) and recrystallized from acetic acid. Yield = 81% (1.33 g); M.p. = 361–363 °C. NMR 1H (DMSO-d6) δ 7.16 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Hε), 7.83–7.90 (4H, m, Hα-Hδ), 8.06 (2H, br. d, J = 7.2 Hz, Hξ), 9.52 (1H, s, NH), 12.75 (1H, s, COOH). NMR 13C (DMSO-d6) δ 118.2, 122.5, 125.7, 126.7, 127.1, 127.6, 129.9, 132.3, 134.0, 135.2, 143.2, 143.84, 167.5, 177.5, 180.5. Mass-spectra EI M/z (I,%): 328(40), 326(100), 292(30), 282(20), 248(55). C17H10ClNO4; Mr = 327.73 g/mol. Compounds 22a-e were obtained under similar conditions.

4.1.3. (3-Chloro-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydro-naphthalen-2-ylamino)-acetic acid (22a)

Yield = 79%, M.p. = 208–210 °C. NMR 1H (CDCl3): 3.90 (2H, d, J = 5.6 Hz, NHCH2), 6.57 (1H, br s, NH), 7.08 (1H, dd, J = 7.6 Hz, Hβ), 7.17 (1H, dd, J = 7.2 Hz, Hγ), 7.40 (2H, dd, J1 = 7.6 Hz J2 = 8.0 Hz, Hα+Hδ), 12.05 (1H, br s, COOH). Mass-spectra EI M/z (I,%): 267(10), 265(30), 220(100), 157(20). C12H8ClNO4; Mr = 265.65 g/mol.

4.1.4. 3-(3-Chloro-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydro-naphthalen-2-ylamino)-propionic acid (22b)

Yield = 75%; M.p. = 178–180 °C. NMR 1H (DMSO-d6): 2.63 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz, CH2COOH), 3.95 (2H, td, J = 6.6 Hz, NHCH2), 7.38 (1H, br s, NH), 7.75 (1H, dd, J = 7.8 Hz, Hβ), 7.83 (1H, dd, J = 8.4 Hz, Hγ), 7.97 (2H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, Hα+Hβ), 12.39 (1H, br s, COOH). NMR 13C (DMSO-d6) δ 35.6, 40.6, 106.3, 127.0, 127.6 130.5, 131.5, 132.4, 133.2, 135.4, 173.1, 175.9, 180.6. Mass-spectra EI M/z (I,%): 280(20), 279(75), 233(20), 222(25), 220(100), 157(35). C13H10ClNO4; Mr = 279.68 g/mol.

4.1.5. 4-(3-Chloro-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydro-naphthalen-2-ylamino)-butyric acid (22c)

Yield = 80%; M.p. = 173–174 °C. NMR 1H (DMSO-d6) δ 1.85 (2H, m, CH2CH2CH2), 2.30 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz, CH2COOH), 3.75 (2H, td, J = 6.6 Hz, NHCH2), 7.56 (1H, br s, NH), 7.75 (1H, td, J1 = 7.8 Hz J2 = 1.2 Hz, Hβ), 7.83 (1H, td, J1 = 8.4 Hz J2 = 1.2 Hz, Hγ), 7.97 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Hβ), 12.11 (1H, br s, COOH). NMR 13C (DMSO-d6) δ 26.4, 31.3, 43.8, 126.3, 126.9, 127.6, 130.4, 132.5, 133.1, 135.3, 145.8, 174.6, 176.4, 180.6. Mass-spectra EI M/z (I,%):295(10), 293(40), 240(30), 222(25), 220(100), 212(20). C14H12ClNO4; Mr = 293.97 g/mol.

4.1.6. 6-(3-Chloro-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydro-naphthalen-2-ylamino)-hexanoic acid (22d)

Yield = 71%; M.p. = 117–120°C. NMR 1H (DMSO-d6) δ 1.32 (2H, m, (CH2)2CH2(CH2)2), 1.52 (2H, m, HOOCCH2CH2(CH2)3), 1.61 (2H, m, NHCH2CH2(CH2)3), 2.18 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2COOH), 3.70 (2H, td, J = 7.2 Hz, NHCH2)td, 7.53 (1H, br s, NH)br s1 H, 7.74 (1H, td, J1 = 7.2 Hz J2 = 1.2 Hz, Hβ), 7.83 (1H, td, J1 = 7.8 Hz J2 = 1.2 Hz, Hγ), 7.97 (2H, br d, J = 7.2 Hz, Hα+Hδ), 12.06 (1H, br s, COOH). NMR 13C (DMSO-d6) δ 24.9, 26.2, 31.1, 34.7, 44.3, 125.93, 126.3, 127.0, 130.4, 132.6, 133.1, 135.4, 145.6, 172.2, 175.8, 180.7. Mass-spectra FAB M/z (I,%):323(15). 321(40), 222(35), 220(100). C16H16ClNO4; Mr = 321.76 g/mol.

4.1.7. 3-(3-Chloro-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydro-naphthalen-2-ylamino)-benzoic acid (22e)

Yield = 83%; M.p. = 313–316 °C. NMR 1H (DMSO-d6) δ 7.34 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Hξ), 7.42 (1H, dd, J1 = 7.8 Hz J2 = 1.2 Hz, Hη), 7.68–7.70 (2H, m, Hξ+Hθ), 7.82 (1H, td, J1 = 7.2 Hz J2 = 1.2 Hz, Hβ), 7.88 (1H, td, J1 = 7.2 Hz J2 = 0.6 Hz, Hγ), 8.05 (2H, d, J1 = 7.8 Hz, Hα+Hδ), 9.43 (1H, s, NH), 13.145 (1H, br s, COOH); NMR 13C (DMSO-d6) δ 115.4, 124.8, 125.4, 126.6, 127.0, 128.0, 128.4, 130.8, 132.4, 133.7, 135.2, 139.5, 143.6, 167.9, 177.3, 180.4. Mass-spectra EI M/z (I,%): 329(40), 327(100), 292(35), 274(90), 248(30). C17H10ClNO4; Mr = 327.73 g/mol.

4.1.8. 4-(3-Chloro-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydro-naphthalen-2-ylamino)-benzoic acid methyl ester (22g)

A mixture of 2,3-dichloro-1,4-naphthoquinone (1.135 g, 5 mmol), 4-amino-benzoic acid methyl ester (3.023 g, 20 mmol), and sodium acetate trihydrate (0.68 g, 5 mmol) in 50 ml of 50% ethanol was heated under reflux for 12 h (presence of 2,3-dichloro-1,4-naphthoquinone was controlled by TLC in CHCl3). The mixture was cooled to room temperature and poured in 200 ml of water. The precipitate was filtered, washed with 1M HCl (3 × 20 ml) and H2O (3 × 30 ml) and recrystallized from ethanol. Yield = 76%; M.p. = 281–283 °C. NMR 1H (DMSO-d6) δ 3.84 (3H, s, COOCH3), 7.18 (2H, d, J = 9.0 Hz, Hε), 7.84 (1H, dt, J1 = 7.8 Hz, J2 = 1.8, Hβ), 7.87–7.91 (3H, m, Hα+Hδ+Hγ), 8.06 (2H, br t, Hξ), 9.56 (1H, s, NH)s 1H NH; NMR 13C (DMSO-d6) δ 52.4; 119.0; 122.5; 124.4; 126.7; 127.1; 129.7; 131.0; 132.3; 134.0; 135.2; 143.1; 144.3; 166.4; 177.5; 180.4. Mass-spectra EI M/z (I,%): 343(33), 341(100), 310(60), 282(22), 262(20), 247(20), 138(20). C18H12ClNO4; Mr = 341.75 g/mol. Compounds 23a,b were obtained under similar conditions.

4.1.9. 2-Chloro-3-(2-hydroxy-ethylamino)-1,4-naphthoquinone (23a)

Yield = 82%; M.p. = 154–156 °C. NMR 1H (DMSO-d6) δ 3.60 (2H, dt, J = 5.4 Hz, NHCH2), 3.83 (6H, dt, J = 6.0 Hz, CH2OH), 4.93 (1H, t, J = 5.4 Hz, CH2OH), 7.24 (1H, br s, NH), 7.75 (1H, dd, J = 7.8 Hz, Hγ), 7.83 (1H, dd, J = 7.2 Hz, Hβ), 7.97 (2H, dd, J1 = 7.8 Hz J2 = 3 Hz, Hα+Hδ); NMR 13C (DMSO-d6) δ 46.8, 59.6, 100.4, 126.3, 126.9, 131.9, 132.5, 133.2, 135.4, 140.1, 173.9, 180.6. Mass-spectra EI M/z (I,%): 253(10), 251(400), 235(20), 233(55) 222(50), 220(100). C12H10ClNO3; Mr = 251.67 g/mol.

4.1.10. 2-Chloro-3-(3-hydroxy-propylamino)-1,4-naphthoquinone (23b)

Yield = 77%; M.p. = 120–121 °C. NMR 1H (DMSO-d6) δ 1.775 (2H, m, CH2CH2CH2), 3.51 (2H, dt, J = 5.4 Hz, NHCH2), 3.82 (2H, dt, J = 6.6 Hz, CH2OH), 4.66 (1H, t, J = 4.8 Hz, CH2OH),7.54 (1H, br s, NH), 7.74 (1H, dd, J = 7.8 Hz, Hγ), 7.83 (1H, dd, J = 7.2 Hz, Hβ), 7.97 (2H, dd, J1 = 7.8 Hz J2 = 2.4 Hz, Hα+Hδ); NMR 13C (DMSO-d6) δ 33.7, 42.7, 59.1, 108.5, 126.3, 126.9, 130.4, 132.6, 133.1, 135.4, 145.8, 175.8, 180.6. Mass-spectra EI M/z (I,%): 267(10), 265(50), 222(30), 220(100). C13H12ClNO3; Mr = 265.70 g/mol.

4.1.11. 2-Chloro-3-(3-morpholin-4-yl-propylamino)-1,4-naphthoquinone (24)

A mixture of 2,3-dichloro-1,4-naphthoquinone (2.27 g, 10 mmol), 3-morpholin-4-yl-propylamine (1.586 g, 11 mmol), and sodium acetate trihydrate (2.722 g, 20 mmol) in 100 ml of ethanol was heated under reflux for 16 h (presence of 2,3-dichloro-1,4-naphthoquinone was controlled by TLC in CHCl3). The mixture was cooled to −18 °C, filtered, washed with cooled ethanol (2 × 5 ml) and H2O (2 × 10 ml) and recrystallized from ethanol. Yield = 95%; M.p. = 175–176 °C. NMR 1H (DMSO-d6) δ 1.77 (2H, m, CH2CH2CH2), 2.35–2.39 (6H, m, CH2NH(CH2 CH2)2O), 3.58 (4H, br s, NH(CH2 CH2)2O), 3.83 (2H, dt, J = 7.2 Hz, NHCH2), 7.74 (1H, dd, J = 7.2 Hz, Hβ), 7.83 (1H, dd, J = 7.8 Hz, Hγ), 7.97 (2H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, Hα+Hδ); NMR 13C (DMSO-d6) δ 26.8, 44.1, 53.9, 56.8, 66.5, 126.3, 126.9, 130.4, 132.6, 133.1, 135.4, 146.1, 175.7, 180.7. Mass-spectra EI M/z (I,%): 334(10), 220(40), 114(55), 100(100). C17H19ClN2O3, Mr = 334.81 g/mol.

4.1.12. 4-(1,4-Dioxo-3-piperidin-1-yl-1,4-dihydro-naphthalen-2-ylamino)-benzoic acid methyl ester (25a)

The compound was synthetized, as described previously [39], using 22g (see Scheme 1). To a solution of 22g (144 mg, 0.42 mmol) in 2 ml of ethanol, 0.5 ml (426 mg, 5 mmol) of piperidine was added. The mixture was heated under reflux for 20 h. The mixture was cooled to −18 °C, filtered, and washed with cooled ethanol (2 × 1 ml) and H2O(3 × 1 ml). Yield = 51%; M.p. = 186–188 °C. NMR 1H (DMSO-d6) δ 1.36 (6H, br s, NH(CH2CH2)2CH2), 3.14 (4H, br s, NH(CH2 CH2)2CH2), 3.79 (3H, s, COOCH3), 6.92 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Hε), 7.75–7.79 (4H, m, Hα-Hδ), 7.93–7.97 (2H, m, Hξ)m 2 H, 8.43 (1H, s, NH); NMR 13C (DMSO-d6) δ 24.2, 26.3, 50.1, 52.0, 116.8, 120.0, 125.5, 126.5, 126.5, 130.3, 131.1, 132.5, 133.8, 140.9, 147.2, 166.6, 181.4, 182.2. Mass-spectra FAB M/z (I,%): 391(100) [M+H]+. C23H22N2O4; Mr = 390.44 g/mol.

4.1.13. 4-(3-Methoxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydro-naphthalen-2-ylamino)-benzoic acid methyl ester (25b)

Compound 22g (144 mg, 0.42 mmol) was added to a solution of sodium methylate (46 mg, 0.84 mmol) in 2 ml of methanol. The mixture was heated under reflux for 4 h. The mixture was cooled to −18 °C, filtered, and washed with cooled methanol (2 × 1 ml) and H2O (3 × 1 ml). Yield = 64%; M.p. 199–201 °C. NMR 1H (DMSO-d6) δ 3.66 (3H,s, OCH3), 3.82 (3H, s, COOCH3), 7.05 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Hε), 7.79–7.87 (4H, m, J = 5.4 Hz, Hα+Hδ+Hξ), 7.99 (2H, dd, J1 = 4.2 Hz J2 = 3.6 Hz, Hβ+Hγ), 8.82 (1H, s, NH); NMR 13C (DMSO-d6) δ 52.2, 59.9, 119.8, 122.3, 126., 126.3, 129.8, 130.8, 131.9, 132.9, 133.8, 134.8, 144.2, 146.0, 166.5, 179.8, 182.8. Mass-spectra EI M/z (I,%): 337(10), 294(15), 133(20), 104(20), 76(20). C19H15NO5; Mr = 337.34 g/mol.

4.2. Other compounds

Compounds 1–21 (see Table 1) and six 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinazoline and quinazolin-4(3H)-one analogs (see Supplementary Table S1) were purchased from Princeton BioMolecular Research (Princeton, NJ, USA), Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), ChemShuttle (Hayward, CA, USA), AlfaAesar (Haverhill, MA, USA), Totonto Research Chemicals (Toronto, ON, Canada), and Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland).

4.3. Kinase assay

Dissociation constant (Kd) determination was performed by KINOMEscan (Eurofins Pharma Discovery, San Diego, CA, USA), as described previously [61,62]. In brief, MKK4 and MKK7 were produced and displayed on T7 phage or expressed in HEK-293 cells. Binding reactions were performed at room temperature for 1 h, and the fraction of kinase not bound to a test compound was determined by capture with an immobilized affinity ligand and quantified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Primary screening at fixed concentrations of compounds was performed in duplicate. For Kd determination, a 12-point half-log dilution series (a maximum concentration of 30 μM) was used. Assays were performed in duplicate, and their average mean value is displayed. Reference anticancer compound sunitinib was obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO, USA).

4.4. Cdc25 inhibition assay

CycLex® protein phosphatase Cdc25A and B fluorometric assay Kits (Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd, Japan) were used to evaluate enzyme inhibition by naphthoquinone analogs. Cdc25A and B activity was measured in a 96-well half-area microtiter plate using 3-O-methylfluorescein phosphate (OMFP) as a substrate. Five μL (0.1 μg/μL) of purified recombinant Cdc25 (Cdc25A or B) was mixed with 40 μL of assay mixture and incubated with 5 μL of the test compound at various concentrations in a well. Kinetic measurements were obtained every 30 s for 10 min at 25 °C using a Fluoroskan Ascent FL fluorescence microplate reader (Thermo Electron, MA) with excitation and emission wavelengths at 485 and 538 nm, respectively. For all compounds tested, the concentration of inhibitor that caused 50% inhibition of the enzymatic reaction (IC50) was calculated by plotting % inhibition versus logarithm of inhibitor concentration.

4.5. HNE inhibitory assay

The HNE inhibition assay was performed in black flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates. Briefly, a buffer solution containing 200 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 0.01% bovine serum albumin, 0.05% Tween-20, and 20 mU/mL HNE (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) was added to wells containing different concentrations of each compound. The reactions were initiated by addition of 25 μM elastase substrate (N-methylsuccinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin, Calbiochem) in a final reaction volume of 100 μL/well. Kinetic measurements were obtained every 30 s for 10 min at 25 °C using a Fluoroskan Ascent FL fluorescence microplate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths at 355 and 460 nm, respectively. The concentration of inhibitor that caused 50% inhibition of the enzymatic reaction (IC50) was calculated by plotting % inhibition versus logarithm of inhibitor concentration.

4.6. Cell culture

All cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. A549 carcinoma cells were cultivated in F–12K medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). SW-982 synovial sarcoma cells were cultivated in Leibovitz's L-15 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. MCF7 breast adenocarcinoma cells were cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 μg/ml bovine insulin and 10% FBS. LS-174t colorectal adenocarcinoma cells were cultivated in Eagle's minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% FBS. HL60 cells were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS. THP-1, U937, and Jurkat T cells were cultivated in RPM1-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. MonoMac6 cells (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 10 μg/ml bovine insulin. All cultural media also contained 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin.

PBMCs were purified from human blood using dextran sedimentation, followed by Histopaque 1077 gradient separation and hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes. Blood was collected from healthy donors in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at Montana State University, and informed consent was obtained from all donors for the use of their blood in this study (Protocol #MQ041017). PBMCs were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 U/ml penicillin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cell number and viability were assessed microscopically using trypan blue exclusion.

4.7. Anticancer cell cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity was analyzed with a CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay Kit from Promega (Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were treated with the compounds under investigation and incubated for 24 h. After treatment, the cells were allowed to equilibrate to room temperature for 30 min, substrate was added, and the samples were analyzed with a Fluoroscan Ascent FL fluorescence microplate reader. The IC50 was calculated by plotting percentage inhibition against the logarithm of inhibitor concentration (at least five points).

4.8. Molecular docking

The structure of MKK7 was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (2DYL entry) and imported into the Molegro Virtual Docker 6.0 (MVD) program (CLC Bio, Copenhagen, Denmark). All co-crystallized water molecules were removed from the downloaded structure. The 2DYL file did not contain any co-crystallized ligands, so we searched for cavities as potential binding sites. The “detect cavity” tool of MVD was applied with default options, which led to detection of 5 cavities in MKK7. The largest cavity of 152 Å3 in volume was regarded as a binding site for the docking study (Supplementary Fig. S1). A sphere 8 Å in radius around the geometric center of the cavity was set as a search space for initial pose generation. This sphere fully embraced the cavity. Molecular models of investigated naphthoquinones were built and pre-optimized with the ChemBioOffice 2010 suite, imported in the MVD program, and docked into MKK7 with full conformational flexibility of a ligand and rigid structure of the receptor. Thirty docking runs were performed for each ligand with the MolDock scoring function and the following options of the MVD Docking Wizard: “Constrain poses to cavity”, “Ligand Energy Minimization and Optimize H-bonds after docking”. The best docking poses were saved and analyzed with the built-in visualization tool of MVD software.

For docking into the Cdc25B binding site, the structure of the human Cdc25B catalytic domain was used (PDB code 1QB0). This structure, along with the prepared molecular models of the investigated naphthoquinones (see above), were uploaded on the ROSIE web server [50], where the ligand docking protocol [63,64] was applied. Up to 500 conformers were generated for each ligand with the use of BCL conformer generation algorithm [65] incorporated in the ROSIE server. The center of search space was chosen between the geometric centers of Cys473 and Tyr428. Performance of 1000 docking runs was set for each investigated ligand, with the other options of the docking protocol used as default. The docking poses with the optimally induced conformations of the surrounding Cdc25B protein were downloaded from the ROSIE server in PDB format, imported into the MVD program, and analyzed with built-in visualization and “Energy inspector” tools of the MVD software.

4.9. DFT calculations

The structures of the investigated naphthoquinones were built and pre-optimized by the semiempirical PM3 method using HyperChem 7 software (Hypercube, Inc, Gainesville, FL, USA). For lapachol, which exists in different tautomeric forms, the tautomer listed in the PubChem database was taken for DFT analysis (PubChem CID: 3884). DFT calculations were performed with the use of the ORCA 4.1.1 program (Max Planck Institute fuer Kohlenfor-schung, Muelheim/Ruhr, Germany, December 2018) on a computer operating under Windows Server 2016 (16 × 2.4 GHz CPU, 16 Gb RAM). The BP86 functional [66], def2-TZVPP orbital basis set [67], RI approximation with def2/J auxiliary basis set [53], and D3BJ dispersion correction [68] were applied. Attaining real energy minima on geometry optimizations in vacuo was confirmed by frequency calculations. Subsequently, for the energy minimum found for each compound, a single point calculation was performed using the ωB97X-D3 functional [54], 6–311++G(3df,3pd) orbital basis set with RIJCOSX approximation [69,70], and auxiliary basis sets generated by the AutoAux procedure [71]. For the computation of vertical electron affinities (VEABP86 and VEA), the anion radical species were subjected to single point calculation with the BP86 and ωB97X-D3 functionals at the geometries of the corresponding neutral naphthoquinones optimized, as described above. The obtained results were visualized and analyzed with the use of Chemcraft graphical software for visualization of quantum chemistry computations (https://www.chemcraftprog.com).

4.10. Calculation of lipophilicity

Octanol-water partition coefficients (LogP) were calculated using ACD/ChemSketch software (Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc., Toronto, Ontario).

4.11. Statistics

Linear regression analysis was performed on the indicated sets of data to obtain correlation coefficients, 95% confidence intervals, and statistical significance (GraphPad Prism Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The quality of the fit was characterized by the Pearson's correlation (r) and the probability of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis (p).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health IDeA Program COBRE Grant GM110732; USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch project 1009546; the Montana State University Agricultural Experiment Station; the Tomsk Polytechnic University Competitiveness Enhancement Program; and the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation project No. 4.8192.2017/8.9.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111719.

References

- [1].Bhasin D, Chettiar SN, Etter JP, Mok M, Li PK, Anticancer activity and SAR studies of substituted 1,4-naphthoquinones, Biorg. Med. Chem 21 (2013) 4662–4669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bin Hafeez B, Zhong WX, Fischer JW, Mustafa A, Shi XD, Meske L, Hong H, Cai WB, Havighurst T, Kim K, Verma AK, Plumbagin, a medicinal plant (Plumbago zeylanica)-derived 1,4-naphthoquinone, inhibits growth and metastasis of human prostate cancer PC-3M-luciferase cells in an orthotopic xenograft mouse model, Mol. Oncol 7 (2013) 428–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Balassiano IT, De Paulo SA, Silva NH, Cabral MC, Carvalho MDGDC, Demonstration of the lapachol as a potential drug for reducing cancer metastasis, Oncol. Rep 13 (2005) 329–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Carr BI, Wang Z, Kar S, K vitamins PTP antagonism, and cell growth arrest, J. Cell. Physiol 193 (2002) 263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brezak MC, Kasprzyk PG, Galcera MO, Lavergne O, Prevost GP, CDC25 inhibitors as anticancer agents are moving forward, Anti Cancer Agents Med. Chem 8 (2008) 857–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhang SD, Gao Q, Li W, Zhu LW, Shang QH, Feng S, Jia JM, Jia QQ, Shen S, Su ZH, Shikonin inhibits cancer cell cycling by targeting Cdc25s, BMC Canc. 19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Song GY, Kim Y, Zheng XG, You YJ, Cho H, Chung JH, Sok DE, Ahn BZ, Naphthazarin derivatives (IV): synthesis, inhibition of DNA topoisomerase I and cytotoxicity of 2-or 6-acyl-5,8-dimethoxy-1,4-naphahoquinones, Eur. J. Med. Chem 35 (2000) 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brenner AK, Reikvam H, Rye KP, Hagen KM, Lavecchia A, Bruserud O, CDC25 inhibition in acute myeloid leukemia-A study of patient heterogeneity and the effects of different inhibitors, Molecules (2017) 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lee SH, Shen GN, Jung YS, Lee SJ, Chung JY, Kim HS, Xu Y, Choi Y, Lee JW, Ha NC, Song GY, Park BJ, Antitumor effect of novel small chemical inhibitors of Snail-p53 binding in K-Ras-mutated cancer cells, Oncogene 29 (2010) 4576–4587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Watanabe N, Forman HJ, Autoxidation of extracellular hydroquinones is a causative event for the cytotoxicity of menadione and DMNQ in A549-S cells, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 411 (2003) 145–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wu J, Chien CC, Yang LY, Huang GC, Cheng MC, Lin CT, Shen SC, Chen YC, Vitamin K3-2,3-epoxide induction of apoptosis with activation of ROS-dependent ERK and JNK protein phosphorylation in human glioma cells, Chem. Biol. Interact 193 (2011) 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lien YC, Kung HN, Lu KS, Jeng CJ, Chau YP, Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress and activation of MAP kinases in beta-lapachone-induced human prostate cancer cell apoptosis, Histol. Histopathol 23 (2008) 1299–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Belinsky M, Jaiswal AK, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1 (DT-diaphorase) expression in normal and tumor tissues, Cancer Metastasis Rev. 12 (1993) 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yang Y, Yang WS, Yu T, Yi YS, Park JG, Jeong D, Kim JH, Oh JS, Yoon K, Kim JH, Cho JY, Novel anti-inflammatory function of NSC95397 by the suppression of multiple kinases, Biochem. Pharmacol 88 (2014) 201–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dubey NK, Peng BY, Lin CM, Wang PD, Wang JR, Chan CH, Wei HJ, Deng WP, NSC 95397 suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells through MKP-1 and the ERK1/2 pathway, Int. J. Mol. Sci 19 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Blevins MA, Kouznetsova J, Krueger AB, King R, Griner LM, Hu X, Southall N, Marugan JJ, Zhang Q, Ferrer M, Zhao R, Small molecule, NSC95397, inhibits the CtBP1-protein partner interaction and CtBP1-mediated transcriptional repression, J. Biomol. Screen 20 (2015) 663–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lazo JS, Nemoto K, Pestell KE, Cooley K, Southwick EC, Mitchell DA, Furey W, Gussio R, Zaharevitz DW, Joo B, Wipf P, Identification of a potent and selective pharmacophore for Cdc25 dual specificity phosphatase inhibitors, Mol. Pharmacol 61 (2002) 720–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lavecchia A, Coluccia A, Di Giovanni C, Novellino E, Cdc25B phosphatase inhibitors in cancer therapy: latest developments, trends and medicinal chemistry perspective, Anti Cancer Agents Med. Chem 8 (2008) 843–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sur S, Agrawal DK, Phosphatases and kinases regulating CDC25 activity in the cell cycle: clinical implications of CDC25 overexpression and potential treatment strategies, Mol. Cell. Biochem 416 (2016) 33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brenner AK, Reikvam H, Lavecchia A, Bruserud O, Therapeutic targeting the cell division cycle 25 (CDC25) phosphatases in human acute myeloid leukemia - the possibility to target several kinases through inhibition of the various CDC25 isoforms, Molecules 19 (2014) 18414–18447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kristjansdottir K, Rudolph J, Cdc25 phosphatases and cancer, Chem. Biol 11 (2004) 1043–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lavecchia A, Di Giovanni C, Novellino E, Inhibitors of Cdc25 phosphatases as anticancer agents: a patent review, Expert Opin. Ther. Pat 20 (2010) 405–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Li JY, Wang H, May S, Song X, Fueyo J, Fuller GN, Wang H, Constitutive activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase correlates with histologic grade and EGFR expression in diffuse gliomas, J. Neuro Oncol 88 (2008) 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chang Q, Chen J, Beezhold KJ, Castranova V, Shi X, Chen F, JNK1 activation predicts the prognostic outcome of the human hepatocellular carcinoma, Mol. Cancer 8 (2009) 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wu Q, Wu W, Fu B, Shi L, Wang X, Kuca K, JNK signaling in cancer cell survival, Med. Res. Rev (2019. March 25), 10.1002/med.21574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wang X, Chao L, Li X, Ma G, Chen L, Zang Y, Zhou G, Elevated expression of phosphorylated c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase in basal-like and "triple-negative" breast cancers, Hum. Pathol 41 (2010) 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yeh YT, Hou MF, Chung YF, Chen YJ, Yang SF, Chen DC, Su JH, Yuan SS, Decreased expression of phosphorylated JNK in breast infiltrating ductal carcinoma is associated with a better overall survival, Int. J. Cancer 118 (2006) 2678–2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Xie X, Kaoud TS, Edupuganti R, Zhang T, Kogawa T, Zhao Y, Chauhan GB, Giannoukos DN, Qi Y, Tripathy D, Wang J, Gray NS, Dalby KN, Bartholomeusz C, Ueno NT, c-Jun N-terminal kinase promotes stem cell phenotype in triple-negative breast cancer through upregulation of Notch1 via activation of c-Jun, Oncogene 36 (2017) 2599–2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Davis RJ, Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases, Cell 103 (2000) 239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Harper SJ, LoGrasso P, Signalling for survival and death in neurones - the role of stress-activated kinases, JNK and p38, Cell. Signal. 13 (2001) 299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Shvedova M, Anfinogenova Y, Atochina-Vasserman EN, Schepetkin IA, Atochin DN, c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) in myocardial and cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury, Front. Pharmacol 9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Vercelli A, Biggi S, Sclip A, Repetto IE, Cimini S, Falleroni F, Tomasi S, Monti R, Tonna N, Morelli F, Grande V, Stravalaci M, Biasini E, Marin O, Bianco F, di Marino D, Borsello T, Exploring the role of MKK7 in excitotoxicity and cerebral ischemia: a novel pharmacological strategy against brain injury, Cell Death Dis. 6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shraga A, Olshvang E, Davidzohn N, Khoshkenar P, Germain N, Shurrush K, Carvalho S, Avram L, Albeck S, Unger T, Lefker B, Subramanyam C, Hudkins RL, Mitchell A, Shulman Z, Kinoshita T, London N, Covalent docking identifies a potent and selective MKK7 inhibitor, Cell Chem. Biol 26 (2019) 98, 108 e105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tamura K, Southwick EC, Kerns J, Rosi K, Carr BI, Wilcox C, Lazo JS, Cdc25 inhibition and cell cycle arrest by a synthetic thioalkyl vitamin K analogue, Cancer Res. 60 (2000) 1317–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kar S, Wang M, Ham SW, Carr BI, Fluorinated Cpd 5, a pure arylating K-vitamin derivative, inhibits human hepatoma cell growth by inhibiting Cdc25 and activating MAPK, Biochem. Pharmacol 72 (2006) 1217–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cao S, Murphy BT, Foster C, Lazo JS, Kingston DG, Bioactivities of simplified adociaquinone B and naphthoquinone derivatives against Cdc25B, MKP-1, and MKP-3 phosphatases, Bioorg. Med. Chem 17 (2009) 2276–2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Braud E, Goddard ML, Kolb S, Brun MP, Mondesert O, Quaranta M, Gresh N, Ducommun B, Garbay C, Novel naphthoquinone and quinolinedione inhibitors of CDC25 phosphatase activity with antiproliferative properties, Bioorg. Med. Chem 16 (2008) 9040–9049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Brun MP, Braud E, Angotti D, Mondesert O, Quaranta M, Montes M, Miteva M, Gresh N, Ducommun B, Garbay C, Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel naphthoquinone derivatives with CDC25 phosphatase inhibitory activity, Biorg. Med. Chem 13 (2005) 4871–4879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ge Y, Li AB, Wu JW, Feng HW, Wang LT, Liu HW, Xu YG, Xu QX, Zhao L, Li YY, Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel non-peptide boronic acid derivatives as proteasome inhibitors, Eur. J. Med. Chem 128 (2017) 180–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dregeris J, Liepinya I, Freimanis Ja, Synthesis and properties of complexes and autocomplexes with charge transfer XVIII. Some water-soluble 1,4-naphthoquinon derivatives, Review of Academy of Sciences of Latvian, Sect. Chem (1977) 460–464. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Shishkina R, Ectova L, Matoshina K, Fokin E, Synthesis of 2,3-bisaminoderivatives of 1,4-naphthoquinones, review of Siberian department of academy of sciences of USSR, Sect. Chem 5 (1982) 136–142. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zhao HF, Wang J, To SST, The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling in cancer: alliance or contradiction? (Review), Int. J. Oncol 47 (2015) 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Klotz LO, Hou X, Jacob C, 1,4-naphthoquinones: from oxidative damage to cellular and inter-cellular signaling, Molecules 19 (2014) 14902–14918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lazo JS, Aslan DC, Southwick EC, Cooley KA, Ducruet AP, Joo B, Vogt A, Wipf P, Discovery and biological evaluation of a new family of potent inhibitors of the dual specificity protein phosphatase Cdc25, J. Med. Chem 44 (2001) 4042–4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lee MH, Cho Y, Kim DH, Woo HJ, Yang JY, Kwon HJ, Yeon MJ, Park M, Kim SH, Moon C, Tharmalingam N, Kim TU, Kim JB, Menadione induces G2/M arrest in gastric cancer cells by down-regulation of CDC25C and proteasome mediated degradation of CDK1 and cyclin B1, Am. J. Transl. Res 8 (2016) 5246–5255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Peyregne VP, Kar S, Ham SW, Wang M, Wang Z, Carr BI, Novel hydroxyl naphthoquinones with potent Cdc25 antagonizing and growth inhibitory properties, Mol. Cancer Ther 4 (2005) 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Tripathi SK, Panda M, Biswal BK, Emerging role of plumbagin: cytotoxic potential and pharmaceutical relevance towards cancer therapy, Food Chem. Toxicol 125 (2019) 566–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ge Y, van der Kamp M, Malaisree M, Liu D, Liu Y, Mulholland AJ, Identification of the quinolinedione inhibitor binding site in Cdc25 phosphatase B through docking and molecular dynamics simulations, J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des 31 (2017) 995–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]