Abstract

Background.

No guidelines exist for surveillance following cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS/HIPEC) for appendiceal and colorectal cancer. The primary objective was to define the optimal surveillance frequency after CRS/HIPEC.

Methods.

The U.S. HIPEC Collaborative database (2000–2017) was reviewed for patients who underwent a CCR0/1 CRS/HIPEC for appendiceal or colorectal cancer. Radiologic surveillance frequency was divided into two categories: low-frequency surveillance (LFS) at q6–12mos or high-frequency surveillance (HFS) at q2–4mos. Primary outcome was overall survival (OS).

Results.

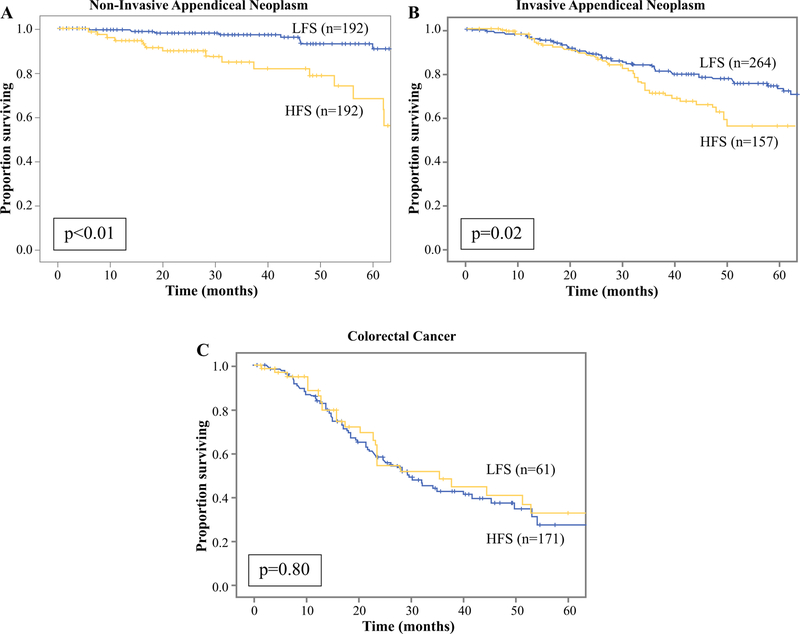

Among 975 patients, the median age was 55 year, 41% were male: 31% had non-invasive appendiceal (n = 301), 45% invasive appendiceal (n = 435), and 24% colorectal cancer (CRC; n = 239). With a median follow-up time of 25 mos, the median time to recurrence was 12 mos. Despite less surveillance, LFS patients had no decrease in median OS (non-invasive appendiceal: 106 vs. 65 mos, p < 0.01; invasive appendiceal: 120 vs. 73 mos, p = 0.02; colorectal cancer [CRC]: 35 vs. 30 mos, p = 0.8). LFS patients had lower median PCI scores compared with HFS (non-invasive appendiceal: 10 vs. 19; invasive appendiceal: 10 vs. 14; CRC: 8 vs. 11; all p < 0.01). However, on multivariable analysis, accounting for PCI score, LFS was still not associated with decreased OS for any histologic type (non-invasive appendiceal: hazard ratio [HR]: 0.28, p = 0.1; invasive appendiceal: HR: 0.73, p = 0.42; CRC: HR: 1.14, p = 0.59). When estimating annual incident cases of CRS/HIPEC at 375 for noninvasive appendiceal, 375 invasive appendiceal and 4410 colorectal, LFS compared with HFS for the initial two postoperative years would potentially save $13–19 M/year to the U.S. healthcare system.

Conclusions.

Low-frequency surveillance after CRS/HIPEC for appendiceal or colorectal cancer is not associated with decreased survival, and when considering decreased costs, may optimize resource utilization.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) is a subgroup of stage IV cancer characterized by intraperitoneal tumor dissemination with appendiceal and colorectal cancer (CRC) representing two of the most frequent originating histologies. Appendiceal neoplasms (AN) account for approximately 1500 annual cases with PC present in half of all new diagnoses.1 Conversely, CRC accounts for almost 150,000 cases annually, but only 20% of new diagnoses present with synchronous PC.2–7 The management of appendiceal and colorectal PC has evolved considerably with the advent of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Several single-center studies and two randomized, controlled trials have demonstrated a significant survival benefit with a median disease-specific survival of more than 10 years for AN and up to 22 months for CRC.8–16 Despite the recent results of the PRODIGE-7 trial, which demonstrated that HIPEC did not provide any added survival benefit over just CRS for CRC, these procedures continue to be widely performed.17

Even after curative-intent CRS/HIPEC, disease commonly recurs within 2–5 years of treatment with recurrence rates approaching 30% for AN and 80% for CRC with a high proportion confined to the peritoneal cavity.18–22 Knowledge of this anatomic and temporal pattern of recurrence is crucial for the development of surveillance recommendations. Furthermore, because some studies have demonstrated the feasibility as well as survival benefit with secondary CRS/HIPEC for peritoneal recurrences, surveillance is justified to facilitate prompt initiation of salvage therapy.23–28

Several randomized-clinical trials and a 2016 meta-analysis have sought to address the optimal surveillance interval for stage I–III CRC with most studies demonstrating no survival benefit with more frequent surveillance, despite earlier detection of recurrences.29–35 Importantly, limited evidence is available regarding surveillance after curative treatment of stage IV AN or CRC.19,31,36,37 Current recommendations by the NCCN offer wide variability in the frequency of surveillance strategies with cross-sectional imaging ranging from 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years and then every 6 to 12 months for a total of 5 years.34,37–42 While more frequent surveillance may seem prudent, it has potential risks, including false-positive findings, increased radiation exposure, and incremental costs to the U.S. healthcare system.

Notably, no study has evaluated the optimal surveillance strategy after curative-intent treatment with CRS/HIPEC. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to evaluate the difference between a high-frequency and low-frequency surveillance protocol after CRS/HIPEC for AN and CRC in regards to survival and costs to the U.S. healthcare system.

METHODS

Data Source

The U.S. HIPEC Collaborative is a consortium of 12 institutions: Emory University, The Ohio State University, City of Hope, Johns Hopkins University, Mayo Clinic, Medical College of Wisconsin, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of California San Diego, University of Cincinnati, University of Massachusetts, MD Anderson Cancer Center, and University of Wisconsin. All patients, older than 18 years, with AN or CRC who underwent curative-intent CRS with or without HIPEC from 2000 to 2017 were assessed. Analysis was limited to patients who underwent a complete cytoreduction with no visible disease (CCR0), or with no remaining nodules [>2.5 mm (CCR1). Patients who died within 30 days of CRS/HIPEC and those without information on post-operative surveillance frequency were excluded. Demographic, perioperative, and pathologic data were reviewed retrospectively. Institutional review board approval was obtained at each institution before data collection.

Analysis was stratified by histology with AN further classified into non-invasive and invasive according to the 2016 Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International diagnostic terminology.43 Non-invasive AN includes low-grade mucinous neoplasm and high-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm, whereas invasive AN includes adenocarcinoma. Surveillance was performed with cross-sectional imaging of the abdomen and pelvis and frequency was divided into two categories: high-frequency surveillance (HFS) every 2 to 4 months, or low-frequency surveillance (LFS) every 6 to 12 months. Primary outcome was overall survival (OS). Secondary outcome was potential cost savings.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical package 25.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY). Statistical significance was predefined as two-tailed p < 0.05. Chi square or Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables. Continuous variables were analyzed using t-tests or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Comparative analyses were conducted between HFS and LFS cohorts. Survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier (KM) method, and the log-rank test was used for comparison of survival between HFS and LFS cohorts. Univariate Cox regression was performed to determine associations between clinicopathologic variables and OS. Factors that were significantly associated with OS on univariate analysis or significantly different between surveillance cohorts on comparative analyses were included in a multivariable model.

Cost Analysis

The model aimed to estimate savings to the U.S. healthcare system by using an LFS protocol. The 2018 incidence data of stage IV, resectable AN and CRC were determined based on previously published estimates. This hypothetical cohort was simulated to enter either a HFS or LFS protocol over a 2-year period with a CT or MRI-based modality. Patients with non-invasive AN underwent either a contrast CT or MRI abdomen/pelvis at HFS every 4 months or LFS every 12 months. Patients with invasive AN and CRC underwent a non-contrast CT chest and either a contrast CT or MRI abdomen/pelvis at HFS every 3 months or LFS every 6 months. According to the probabilities provided by this study’s survival-analysis, patients could transition to death or remain on surveillance. The cost of each modality was derived by using the 2018 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule and each service was identified using the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code (Table 3). Each model was simulated 1000 times, and the average cost at 2 years was reported.

TABLE 3.

Cost model assumptions

| % | Number | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-invasive appendiceal neoplasms incidence | ||

| Number appendectomies/year | - | 500,00047 |

| Appendiceal neoplasms | 0.3 | 15001 |

| Low-grade incidence | 50 | 15048 |

| Stage IV | 50 | 3751 |

| Final cohort | 375 | |

| Invasive appendiceal neoplasms incidence | ||

| Number appendectomies/year | - | 500,00047 |

| Appendiceal neoplasms | 0.3 | 15001 |

| Low-grade incidence | 50 | 15048 |

| Stage IV | 50 | 3751 |

| Final cohort | 375 | |

| Colorectal cancer incidence | ||

| Incidence of colorectal cancer | - | 150,0003 |

| Incidence of adenocarcinoma/year | 98 | 147,00049 |

| Stage IV (synchronous PC) | 10 | 14,7004 |

| Stage IV (metachronous PC) | 20 | 29,40050 |

| Eligible for CRS/HIPEC | 10 | 4410 |

| Final cohort | 4410 | |

| Cost data | ||

| Modality | CPT | Cost |

| CT chest without contrast | 72,178 | $183.96 |

| CT abdomen with contrast | 74,160 | $235.08 |

| CT pelvis with contrast | 74,170 | $267.48 |

| MRI abdomen with contrast | 74,182 | $390.60 |

| MRI pelvis with contrast | 72,196 | $354.60 |

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinicopathologic Characteristics

Among 2372 patients in the U.S. HIPEC Collaborative, 975 patients were included of which 301 patients had noninvasive AN, 435 invasive AN, and 239 CRC. In patients with non-invasive AN, median age was 47 (interquartile range [IQR] 47–64) and 39% were male (n = 117). CCR0 resection was achieved in 70% (n = 211). Median follow-up was 28 months (IQR 12–50). HFS was used in 31% (n = 93) and LFS in 69% (n = 208). Patients who underwent HFS had a significantly higher median PCI (19 vs. 10, p < 0.01) but were well-matched for other clinicopatho-logic variables (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinicopathologic factors of the entire cohort and comparing HFS versus LFS cohorts

| All patients | HFS | LFS | HFS versus LFS p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-invasive appendiceal neoplasm | n = 301 | n = 93 | n = 208 | |

| Age at diagnosis (median, IQR) | 55 (47–64) | 58 (50–66) | 54 (46–63) | 0.20 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 184 (61) | 56 (60) | 128 (62) | 0.93 |

| Male | 117 (39) | 37 (40) | 80 (38) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 266 (88) | 79 (85) | 187 (90) | 0.41 |

| Black | 15 (5) | 5 (6) | 10(5) | |

| Other | 18 (6) | 8 (9) | 10(5) | |

| ASA class | ||||

| 1 | 2(1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.01) | 0.40 |

| 2 | 63 (21) | 22 (24) | 41 (20) | |

| 3 | 219 (73) | 63 (68) | 156 (75) | |

| 4 | 11 (4) | 5 (5) | 6(3) | |

| BMI | ||||

| ≤ 18 | 7 (2) | 0 (0) | 7 (3) | 0.11 |

| 18–25 | 79 (26) | 24 (26) | 55 (26) | |

| 25–30 | 110 (37) | 36 (39) | 74 (36) | |

| 30–35 | 91 (30) | 31 (33) | 60 (29) | |

| 35–40 | 13 (4) | 2 (2) | 11 (5) | |

| Operative intent | ||||

| Curative | 297 (99) | 92 (99) | 205 (99) | 1.0 |

| Prophylactic | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | |

| PCI (median, IQR) | 12 (5–19) | 19 (11–26) | 10 (4–15) | < 0.01 |

| CCR | ||||

| CCR 0 | 211 (70) | 52 (56) | 159 (76) | < 0.01 |

| CCR 1 | 90 (30) | 41 (44) | 49 (24) | |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Well | 116 (39) | 46 (49) | 70 (34) | 0.77 |

| Moderate | 19 (6) | 9(10) | 10(5) | |

| Poor/un-differentiated | 6 (2) | 2 (2) | 4 (2) | |

| Lymph vascular invasion | 7 (2) | 5 (5) | 2(1) | 0.10 |

| Perineural invasion | 1 (0.3) | 3 (3) | 1 (0.5) | 0.14 |

| Mutations | ||||

| KRAS | 15 (5) | 11 (12) | 4 (2) | 0.41 |

| BRAF | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Multimodal treatment | ||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 32 (11) | 14 (15) | 18 (9) | 0.14 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 22 (7) | 10(11) | 12(6) | 0.09 |

| Recurrence | 81 (27) | 37 (40) | 44 (21) | < 0.01 |

| Peritoneal | 33 (41) | 13 (35) | 20 (45) | 0.39 |

| Distant | 2(3) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | |

| Peritoneal and distant | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Treatment for recurrence | ||||

| Systemic therapy, radiotherapy or targeted therapy | 35 (43) | 12 (32) | 23 (52) | 0.12 |

| Repeat CRS/HIPEC | 18 (22) | 4(11) | 14 (32) | 0.02 |

| Median follow-up (months, IQR) | 28 (12–50) | 23 (9–47) | 32 (14–51) | 0.03 |

| Median time to recurrence (months, IQR) | 14 (7–22) | 13 (6–19) | 14 (8–30) | 0.82 |

| Invasive appendiceal neoplasm | n = 435 | n = 159 | n = 276 | |

| Age at diagnosis (median, IQR) | 55 (47–64) | 55 (46–65) | 55 (47–63) | 0.87 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 265 (61) | 98 (62) | 167 (61) | 0.89 |

| Male | 170 (39) | 61 (38) | 109 (39) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 388 (90) | 138 (87) | 250 (91) | 0.62 |

| Black | 23 (5) | 10(6) | 13 (5) | |

| Other | 21 (5) | 9 (6) | 12(4) | |

| ASA class | ||||

| 1 | 5 (1) | 4 (3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.09 |

| 2 | 80 (18) | 30 (19) | 50 (18) | |

| 3 | 334 (77) | 115 (72) | 219 (79) | |

| 4 | 13 (3) | 7 (4) | 6 (2) | |

| BMI | ||||

| ≤ 18 | 9 (2) | 6 (4) | 3 (1) | 0.24 |

| 18–25 | 148 (25) | 50 (31) | 98 (36) | |

| 25–30 | 131 (31) | 52 (33) | 79 (29) | |

| 30–35 | 110 (26) | 35 (22) | 75 (27) | |

| 35–40 | 29 (7) | 11 (7) | 18 (7) | |

| Operative intent | ||||

| Curative | 432 (99) | 158 (99) | 274 (99) | 1.0 |

| Prophylactic | 3 (1) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.7) | |

| PCI (median, IQR) | 12 (5–19) | 14 (8–22) | 10 (4–17) | < 0.01 |

| CCR | ||||

| CCR 0 | 301 (69) | 111 (70) | 190 (69) | 0.92 |

| CCR 1 | 134 (31) | 48 (30) | 86 (31) | |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Well | 156 (36) | 54 (34) | 102 (37) | < 0.01 |

| Moderate | 77 (18) | 28 (18) | 49 (18) | |

| Poor/un-differentiated | 49 (11) | 31 (19) | 18 (7) | |

| Lymph vascular invasion | 25 (6) | 16 (10) | 9 (3) | 0.03 |

| Perineural invasion | 29 (7) | 17 (11) | 12(4) | 0.11 |

| Mutations | ||||

| KRAS | 42 (10) | 27 (17) | 15 (5) | < 0.01 |

| BRAF | - | - | - | - |

| Multimodal treatment | ||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 119 (27) | 42 (26) | 77 (28) | 0.79 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 64 (15) | 35 (22) | 29 (11) | < 0.01 |

| Recurrence | 200 (46) | 92 (58) | 108 (39) | < 0.01 |

| Peritoneal | 92 (46) | 43 (47) | 49 (45) | 0.05 |

| Distant | 12 (6) | 9(10) | 3 (3) | |

| Peritoneal and distant | 6(3) | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | |

| Treatment for recurrence | ||||

| Systemic therapy, radiotherapy or targeted therapy | 94 (47) | 56 (61) | 38 (35) | < 0.01 |

| Repeat CRS/HIPEC | 16 (8) | 5 (5) | 11 (10) | 0.30 |

| Median follow-up (months, IQR) | 29 (16–51) | 29 (14–47) | 29 (17–56) | 1.0 |

| Median time to recurrence (months, IQR) | 15 (9–24) | 12 (7–20) | 18 (11–35) | < 0.01 |

| Colorectal cancer | n = 239 | n = 174 | n = 65 | |

| Age at diagnosis (median, IQR) | 55 (47–64) | 54 (47–63) | 56 (47–65) | 0.72 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 120 (50) | 84 (48) | 36 (55) | 0.41 |

| Male | 119 (50) | 90 (52) | 29 (45) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 183 (77) | 132 (76) | 51 (78) | 0.69 |

| Black | 22 (9) | 15 (9) | 7(11) | |

| Other | 32 (14) | 25 (14) | 7(11) | |

| ASA class | ||||

| 1 | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 0 (0) | 0.25 |

| 2 | 20 (8) | 14 (8) | 6 (9) | |

| 3 | 188 (79) | 133 (76) | 55 (85) | |

| 4 | 28 (12) | 24 (14) | 4 (6) | |

| BMI | ||||

| ≤ 18 | 6(3) | 2(1) | 4 (6) | 0.11 |

| 18–25 | 67 (28) | 54 (31) | 13 (20) | |

| 25–30 | 85 (36) | 63 (36) | 22 (34) | |

| 30–35 | 72 (30) | 49 (28) | 23 (35) | |

| 35–40 | 6 (3) | 5 (3) | 1 (2) | |

| Operative intent | ||||

| Curative | 238 (99) | 174 (100) | 64 (98) | 0.27 |

| Prophylactic | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| PCI (median, IQR) | 10 (6–16) | 11 (7–17) | 8 (5–14) | 0.01 |

| CCR | ||||

| CCR 0 | 189 (79) | 140 (80) | 49 (75) | 0.50 |

| CCR 1 | 50 (21) | 34 (20) | 16 (25) | |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Well | 21 (9) | 17 (10) | 4 (6) | 0.74 |

| Moderate | 86 (36) | 63 (36) | 23 (35) | |

| Poor/un-differentiated | 41 (17) | 30 (17) | 11 (17) | |

| Lymph vascular invasion | 55 (23) | 42 (24) | 13 (20) | 0.83 |

| Perineural invasion | 30 (13) | 23 (13) | 7(11) | 0.83 |

| Mutations | ||||

| KRAS | 61 (26) | 50 (29) | 11 (17) | 0.90 |

| BRAF | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.34 |

| SMAD4 | 6 (3) | 6(3) | 0 (0) | 0.31 |

| APC | 15 (6) | 13 (7) | 2 (3) | 0.76 |

| PIK3CA | 8 (3) | 7 (4) | 1 (2) | 0.89 |

| Multimodal treatment | ||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 130 (54) | 88 (51) | 42 (65) | 0.07 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 57 (24) | 41 (24) | 16 (25) | 0.95 |

| Recurrence | 151 (63) | 118 (68) | 33 (51) | 0.08 |

| Peritoneal | 42 (28) | 34 (29) | 8 (24) | 0.72 |

| Distant | 19 (13) | 15 (13) | 4(12) | |

| Peritoneal and distant | 19 (13) | 17 (10) | 2 (3) | |

| Treatment for recurrence | ||||

| Systemic therapy, radiotherapy or targeted therapy | 73 (48) | 60 (51) | 13 (39) | 0.33 |

| Repeat CRS/HIPEC | 8 (5) | 3 (3) | 5 (15) | 0.01 |

| Median follow-up (months, IQR) | 17 (9–29) | 17 (9–30) | 16 (9–28) | 0.38 |

| Median time to recurrence (months, IQR) | 7 (5–14) | 7 (4–13) | 12 (6–16) | 0.08 |

Percentages in parentheses are based on cohort size

Bold indicates statistical significance

In patients with invasive AN, median age was 55 (IQR 47–64) and 39% were male (n = 170). CCR0 resection was achieved in 69% (n = 301). Median follow-up was 29 months (IQR 16–51). HFS protocol was used in 37% (n = 159) and LFS in 63% (n = 276). Patients who underwent HFS had a higher median PCI (14 vs. 10, p < 0.01), more poorly/undifferentiated tumors (19 vs. 7%, p < 0.01), and were more frequently treated with adjuvant chemotherapy (22 vs. 11%, p < 0.01; Table 1).

In patients with CRC, median age was 55 (IQR 47–64), 50% were male (n = 119). CCR0 resection was achieved in 79% (n = 189). Median follow-up was 17 months (IQR 9–29). HFS was used in 73% (n = 174) and LFS in 27% (n = 65). Patients who underwent HFS had a higher median PCI (11 vs. 8, p < 0.01; Table 1).

Recurrence and Survival Analysis by Frequency of Surveillance

For patients with non-invasive AN, 27% of patients (n = 81) recurred of which 43% underwent salvage treatment with any modality, and 22% underwent repeat CRS/HIPEC. While HFS patients had more recurrences (40 vs. 21%, p < 0.01), LFS patients were treated with secondary CRS/HIPEC more frequently (11 vs. 32%, p = 0.02). There was no difference in median time to recurrence (13 vs. 14 months, p = 0.82; Table 1). On KM analysis, LFS patients had a non-inferior 5-year OS compared with HFS (91 vs. 62%, p < 0.01; Fig. 1). On univariate analysis, CCR1 status, poorly/undifferentiated grade, presence of lymphovascular and perineural invasion, receipt of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy, and recurrence were associated with worse OS (Table 2). LFS was associated with non-inferior OS (HR: 0.22, p < 0.01). When considering PCI, CCR, and tumor grade on multivariable-analysis, LFS remained associated with non-inferior OS (HR: 0.28, p = 0.10).

FIG. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival comparing surveillance frequencies: a non-invasive appendiceal neoplasm, b invasive appendiceal neoplasm, c colorectal cancer

TABLE 2.

Clinicopathologic factors associated with overall survival for each histology

| Univariable cox regression | Multivariable cox regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Non-invasive appendiceal neoplasm | ||||

| Age at diagnosis | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 0.78 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | |||

| Male | 0.78 (0.34–1.77) | 0.56 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | 2.28 (0.53–9.80) | 0.27 | ||

| Other | 1.36 (0.18–10.26) | 0.77 | ||

| PCI score | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | 0.12 | 0.99 (0.93–1.04) | 0.63 |

| CCR | ||||

| CCR 0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| CCR 1 | 2.90 (1.32–6.38) | < 0.01 | 2.18 (0.64–7.46) | 0.22 |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Well-differentiated | Reference | Reference | ||

| Moderately-differentiated | 3.86 (1.26–11.83) | 0.02 | 2.39 (0.72–7.93) | 0.15 |

| Poorly/un-differentiated | 42.93 (6.65–277.09) | < 0.01 | 42.34 (5.23–341.31) | < 0.01 |

| Lymph vascular invasion | 16.65 (4.73–58.70) | < 0.01 | ||

| Perineural invasion | 28.51 (4.59–176.77) | < 0.01 | ||

| Multimodal treatment | ||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 4.98 (2.06–12.09) | < 0.01 | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 10.37 (1.95–55.02) | < 0.01 | ||

| Recurrence | 7.25 (2.47–12.32) | < 0.01 | ||

| Frequency of surveillance | ||||

| HFS | Reference | Reference | ||

| LFS | 0.22 (0.09–0.49) | < 0.01 | 0.28 (0.06–1.26) | 0.10 |

| Invasive appendiceal neoplasm | ||||

| Age at diagnosis | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.77 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | |||

| Male | 1.32 (0.89–1.85) | 0.16 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | 1.31 (0.57–3.00) | 0.52 | ||

| Other | 1.73 (0.75–3.99) | 0.19 | ||

| BMI | ||||

| ≤ 18 | Reference | |||

| 18–25 | 0.45 (0.16–1.29) | 0.14 | ||

| 25–30 | 0.64 (0.23–1.81) | 0.40 | ||

| 30–35 | 0.37 (0.13–1.08) | 0.07 | ||

| 35–40 | 0.45 (0.11–1.84) | 0.27 | ||

| PCI score | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 0.08 | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 0.07 |

| CCR | ||||

| CCR 0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| CCR 1 | 1.25 (0.84–1.86) | 0.27 | 1.26 (0.55–2.86) | 0.58 |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Well-differentiated | Reference | Reference | ||

| Moderately-differentiated | 2.76 (1.58–4.83) | < 0.01 | 5.11 (2.15–12.14) | < 0.01 |

| Poorly/un-differentiated | 5.89 (3.17–10.95) | < 0.01 | 11.68 (4.70–28.98) | < 0.01 |

| Lymph vascular invasion | 3.8 (1.84–7.87) | < 0.01 | ||

| Perineural invasion | 3.38 (1.50–7.60) | < 0.01 | ||

| Multimodal treatment | ||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 2.64 (1.77–3.91) | < 0.01 | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 1.98 (1.19–3.31) | < 0.01 | ||

| Recurrence | 5.36 (2.85–10.07) | < 0.01 | ||

| Frequency of surveillance | ||||

| HFS | Reference | Reference | ||

| LFS | 0.64 (0.43–0.94) | 0.02 | 0.73 (0.34–1.56) | 0.42 |

| Colorectal cancer | ||||

| Age at diagnosis | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.61 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Male | 1.56 (1.05–2.32) | 0.03 | 1.45 (0.96–2.19) | 0.07 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | 0.55 (0.24–1.27) | 0.16 | ||

| Other | 0.97 (0.54–1.74) | 0.91 | ||

| BMI | ||||

| ≤ 18 | Reference | |||

| 18–25 | 2.44 (0.33–17.86) | 0.38 | ||

| 25–30 | 1.49 (0.20–10.88) | 0.70 | ||

| 30–35 | 1.25 (0.17–9.22) | 0.83 | ||

| 35–40 | 1.13 (0.10–12.50) | 0.92 | ||

| PCI score | 1.06 (1.04–1.09) | < 0.01 | 1.06 (1.03–1.08) | < 0.01 |

| CCR | ||||

| CCR 0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| CCR 1 | 22.34 (1.53–3.59) | < 0.01 | 1.32 (0.77–2.27) | 0.32 |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Well-differentiated | Reference | |||

| Moderately-differentiated | 0.74 (0.36–1.51) | 0.41 | ||

| Poorly/un-differentiated | 1.28 (0.61–2.67) | 0.52 | ||

| Lymph vascular invasion | 1.57 (0.94–2.64) | 0.09 | ||

| Perineural invasion | 1.33 (0.73–2.44) | 0.35 | ||

| Mutations | ||||

| KRAS mutation | 1.17 (0.68–1.99) | 0.58 | ||

| BRAF mutation | 1.19 (0.16–8.86) | 0.86 | ||

| Multimodal treatment | ||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.94 (0.63–1.39) | 0.75 | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 1.12 (0.68–1.86) | 0.66 | ||

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | 0.94 (0.29–2.99) | 0.91 | ||

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | 8.98 (2.61–30.90) | < 0.01 | ||

| Recurrence | 1.92 (1.16–3.17) | 0.01 | ||

| Frequency of surveillance | ||||

| HFS | Reference | Reference | ||

| LFS | 0.94 (0.60–1.47) | 0.8 | 1.14 (0.71–1.84) | 0.59 |

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

For patients with invasive AN, 46% of patients (n = 200) recurred of which 47% underwent salvage treatment with any modality, and 8% underwent secondary CRS/HIPEC. Again, HFS patients had more recurrences (58 vs. 39%, p < 0.01) and a shorter median time to recurrence (12 vs. 18 months, p \ 0.01; Table 1). LFS had a non-inferior 5-year OS (72 vs. 54%, p = 0.02; Fig. 1). On univariate analysis, higher tumor grade, lymphovascular, and perineural invasion, receipt of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy, and recurrence were associated with worse OS (all p < 0.01; Table 2). LFS was associated with non-inferior OS (HR: 0.64, p = 0.02). When considering PCI, CCR, and tumor grade, LFS remained associated with non-inferior OS (HR: 0.73, p = 0.42).

For patients with CRC, 63% (n = 151) recurred of which 48% underwent salvage treatment with any modality, and 5% underwent secondary CRS/HIPEC. There was no difference in the proportion of recurrences between HFS and LFS protocols (66 vs. 51%, p = 0.08) or median time to recurrence (7 vs. 12 months, p = 0.08). HFS and LFS patients had an equivalent 5-year OS (27 vs. 28%, p = 0.8; Fig. 1). On univariate analysis, male sex, higher PCI score, CCR1 status, receipt of adjuvant radiotherapy, and recurrence were associated with worse OS (Table 2). LFS was associated with non-inferior OS (HR: 0.94, p = 0.8). When considering sex, PCI, and CCR, LFS remained associated with non-inferior OS (HR: 1.14, p = 0.59).

Cost Analysis

Estimated 2018 incidence data for each histologic cohort are shown in Table 3. Over a 2-year surveillance period, an LFS CT-based protocol results in a savings of $13,780,294 or $18,746,543 for an MRI-based protocol (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Cost model results for a 2-year surveillance period

| Surveillance protocol | Mean cost (STD)—CT protocol | Mean cost (STD)—MRI protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Non-invasive appendiceal neoplasms (n = 375) | ||

| HFS | $1,128,898.02 ($978.61) | $1,673,898.05 ($1,480.37) |

| LFS | $374,997.21 ($986.81) | $556,119.66 ($1,442.76) |

| Savings | $753,900.81 | $1,117,778.39 |

| Invasive appendiceal neoplasms (n = 375) | ||

| HFS | $2,055,575.44 ($2,642.02) | $2,782,120.61 ($3,485.31) |

| LFS | $1,025,012.12 ($3,082.02) | $1,387,454.23 ($4,021.93) |

| Savings | $1,030,563.32 | $1,394,666.38 |

| Colorectal cancer (n = 4410) | ||

| HFS | $23,945,828.58 ($32,283.47) | $32,408,996.73 ($42,196.84) |

| LFS | $11,949,998.25 ($18,098.09) | $16,174,898.12 ($23,887.23) |

| Savings | $11,995,830.33 | $16,234,098.61 |

| Total savings | $13,780,294.46 | $18,746,543.38 |

DISCUSSION

No evidence-based guidelines exist for surveillance following CRS/HIPEC. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first analysis to examine the possible impact of surveillance frequency on the OS of patients with AN and CRC after curative-intent CRS/HIPEC. Our results demonstrate that although recurrence portends a poor prognosis on OS for all three histologies (Table 2), a low-frequency surveillance protocol is associated with non-inferior OS compared with a high-frequency protocol. Furthermore, depending on which modality is utilized for imaging (CT vs. MRI), a low-frequency protocol affords a potential cost savings of $14–19 million over a 2-year period to the U.S. healthcare system.

In this study, each histology was analyzed according to two radiologic surveillance protocols: high-frequency surveillance every 2 to 4 months, or low-frequency every 6 to 12 months. Across all histologies, patients in the HFS group had higher PCI scores, a known prognostic factor for extent of peritoneal disease and worse OS. Accordingly, patients in the HFS group had significantly more recurrences (non-invasive AN: 40 vs. 21%, invasive AN: 58 vs. 39%, CRC: 66 vs. 51%, all p < 0.01). Importantly, for the patients with invasive AN, median time to recurrence was earlier in the HFS group (12 vs. 18 months, p < 0.01), and in CRC there was a trend towards earlier detection (7 vs. 12 months, p = 0.08), further suggesting a more aggressive tumor biology in the HFS cohort. Intuitively, these patients were surveyed more frequently, a finding that is consistent with some physician surveys, which have indicated that disease severity may increase surveillance intensity.44 However, even when accounting for factors contributing to this selection bias for a HFS protocol, including PCI score and tumor differentiation, LFS was associated with a non-inferior OS for all histologies.

This finding has been previously reported in multiple, randomized, controlled trials for stage I–III CRC. Indeed, the COLOFOL trial evaluated the benefit of a HFS protocol and found no significant impact on OS for stage II/III disease as earlier detection did not translate into reduced mortality.30 Similarly, the FACS trial demonstrated that earlier diagnosis did not lead to improved OS.31 One reason why more frequent surveillance may not be associated with improved outcomes is that recurrences presenting as small nodules are likely to be missed by cross-sectional imaging. One study reported CT sensitivity as low as 60% in lesions 1–6 mm in size with sensitivity increasing to 80% for lesions [1 > cm in size.45 These findings also highlight the need for additional surveillance modalities that improve detection sensitivity and better evaluate patient candidacy for repeat intervention. Additionally, it is likely that even if a small peritoneal nodule is detected after 3 mon0074hs of follow-up, intervention is not pursued immediately, and the patient is imaged again at the next interval to evaluate disease progression, thus eliminating the potential benefit to earlier detection of disease.

Another reason that may explain the lack of benefit to more frequent surveillance is that salvage therapy for recurrence of peritoneal metastases in high-risk patients may not be associated with improved outcomes. Several studies have established that iterative CRS/HIPEC is both feasible and safe in a highly select group with more favorable baseline prognostic characteristics. The results of this study suggest similar selection criteria, because iterative CRS/HIPEC was performed more frequently for patients with non-invasive AN and CRC who underwent LFS, and therefore had more favorable baseline clinicopathologic factors (non-invasive AN: HFS 11% vs. LFS 32%, p = 0.02, CRC: HFS 3% vs. LFS 15%, p = 0.01). As previously established, the early detection of recurrent disease is only useful if the patient’s condition allows for repeated therapeutic intervention, and it is possible that patients who underwent HFS had more unfavorable characteristics, which could result in fewer available options for salvage therapy.

The decision to proceed with more frequent surveillance has significant economic implications, and given the increasing incidence of CRS/HIPEC procedures performed, the cumulative cost of surveillance represents a sizable expenditure for the U.S. healthcare system. Our proposed cost model takes into account a hypothetical cohort of patients with stage IV, resectable AN and CRC. The model considers this cohort entering a high-frequency or low-frequency surveillance protocol. Based on cost data extracted from CMS, the model demonstrates a total savings to the U.S. healthcare system of nearly $14 million for a CT-based protocol or $19 million for an MRI-based protocol.

There are several limitations to our study which arise from its retrospective design. There is certainly a selection bias between the patients in the HFS and LFS cohorts, although this was mitigated with the use of multivariable Cox regression analysis. Additionally, due to lack of available data, this study cannot comment on the true value of surveillance for this disease process. However, it would be unusual for a patient to not undergo surveillance after curative-intent CRS/HIPEC, as is evidenced by the low number of patients in our database who had no surveillance. The limitations of the cost model result from several assumptions as the cohorts were derived by using published estimated incidence data. Additionally, cost data were estimated using Medicare payments as proxy given the interest in estimating cost to the U.S. healthcare system. Although these costs may change over time and vary per institution, the economic impact of LFS is compelling. Lastly, some nuances of the physician–patient relationship cannot be captured in this study as patients may derive reassurance from knowing that they are disease-free. In fact, a study by Lewis et al. highlights that fear of recurrence is a major source of anxiety for patients.46 Conversely, patients may experience disappointment associated with recurrence detection for which salvage therapy may not be indicated. Accordingly, surveillance strategies must balance the advantage of a survival benefit with the limitations of imaging modalities, costs to the healthcare system, and patient satisfaction. The results of this study are not attempting to propose a protocol for generalized acceptance in stage IV disease, but rather suggesting that using a low-frequency surveillance protocol after CRS/HIPEC may optimize these factors. These findings provide a foundation for clinical trials to validate surveillance protocols for peritoneal malignancies.

CONCLUSIONS

In this large, multicenter study, low-frequency surveillance after CRS/HIPEC for appendiceal or colorectal cancer is not associated with worse OS, and when considering decreased costs, may optimize resource utilization. Further prospective studies are needed to validate the appropriateness of a LFS strategy following CRS/HIPEC.

FUNDING

Supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number TL1TR002382 / UL1TR002378 and the Katz Foundation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES The authors have no disclosures relevant to this study.

Meeting Presentation: 14th International Symposium on Regional Cancer Therapies.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaib WL, Assi R, Shamseddine A, et al. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: diagnosis and management. Oncologist. 2018;23(1):137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glehen O, Kwiatkowski F, Sugarbaker PH, et al. Cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: a multi-institutional study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavaliere F, De Simone M, Virzi S, et al. Prognostic factors and oncologic outcome in 146 patients with colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: Italian multicenter study S.I.T.I.L.O. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37(2):148–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manfredi S, Bouvier AM, Lepage C, Hatem C, Dancourt V, Faivre J. Incidence and patterns of recurrence after resection for cure of colonic cancer in a well defined population. Br J Surg. 2006;93(9):1115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Platell CF. Changing patterns of recurrence after treatment for colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(10):1223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayne DG, Fook S, Loi C, Seow-Choen F. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89(12):1545–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ansari N, Chandrakumaran K, Dayal S, Mohamed F, Cecil TD, Moran BJ. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in 1000 patients with perforated appendiceal epithelial tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(7):1035–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, et al. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(20):3737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verwaal VJ, Bruin S, Boot H, van Slooten G, van Tinteren H. 8-year follow-up of randomized trial: cytoreduction and hyper-thermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(9):2426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cashin PH, Mahteme H, Spang N, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy for colorectal peritoneal metastases: a randomised trial. Eur J Cancer. 2016;53:155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elias D, Delperro JR, Sideris L, et al. Treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: impact of complete cytoreductive surgery and difficulties in conducting randomized trials. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11(5):518–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elias D, Lefevre JH, Chevalier J, et al. Complete cytoreductive surgery plus intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia with oxaliplatin for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(5):681–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franko J, Ibrahim Z, Gusani NJ, Holtzman MP, Bartlett DL, Zeh HJ 3rd. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion versus systemic chemotherapy alone for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer. 2010;116(16):3756–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugarbaker PH, Gianola FJ, Speyer JC, Wesley R, Barofsky I, Meyers CE. Prospective, randomized trial of intravenous versus intraperitoneal 5-fluorouracil in patients with advanced primary colon or rectal cancer. Surgery. 1985;98(3):414–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elias D, Gilly F, Boutitie F, et al. Peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis treated with surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: retrospective analysis of 523 patients from a multicentric French study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(1):63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quenet F, Elias D, Roca L, et al. A UNICANCER phase III trial of hyperthermic intra-peritoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC): PRODIGE 7. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(18_suppl):LBA3503–LBA3503. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braam HJ, van Oudheusden TR, de Hingh IH, et al. Patterns of recurrence following complete cytoreductive surgery and hyper-thermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109(8):841–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delhorme JB, Honore C, Benhaim L, et al. Long-term survival after aggressive treatment of relapsed serosal or distant pseudomyxoma peritonei. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(1):159–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Govaerts K, Chandrakumaran K, Carr NJ, et al. Single centre guidelines for radiological follow-up based on 775 patients treated by cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for appendiceal pseudomyxoma peritonei. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(9):1371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feferman Y, Solomon D, Bhagwandin S, et al. Sites of recurrence after complete cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal and appendiceal adenocarcinoma: a tertiary center experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;26: 482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson LE, Russell AH, Tong D, Wisbeck WM. Adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon: sites of initial dissemination and clinical patterns of recurrence following surgery alone. J Surg Oncol. 1983;22(2):95–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Oudheusden TR, Nienhuijs SW, Luyer MD, et al. Incidence and treatment of recurrent disease after cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneally metastasized colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(10):1269–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klaver YL, Chua TC, Verwaal VJ, de Hingh IH, Morris DL. Secondary cytoreductive surgery and peri-operative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal recurrence of colorectal and appendiceal peritoneal carcinomatosis following prior primary cytoreduction. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107(6):585–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chua TC, Quinn LE, Zhao J, Morris DL. Iterative cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for recurrent peritoneal metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108(2):81–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams BH, Alzahrani NA, Chan DL, Chua TC, Morris DL. Repeat cytoreductive surgery (CRS) for recurrent colorectal peritoneal metastases: yes or no? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(8):943–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lord AC, Shihab O, Chandrakumaran K, Mohamed F, Cecil TD, Moran BJ. Recurrence and outcome after complete tumour removal and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in 512 patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from perforated appendiceal mucinous tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(3):396–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Eden WJ, Elekonawo FMK, Starremans BJ, et al. Treatment of isolated peritoneal recurrences in patients with colorectal peritoneal metastases previously treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(7):1992–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kjeldsen BJ, Kronborg O, Fenger C, Jorgensen OD. A prospective randomized study of follow-up after radical surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1997;84(5):666–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wille-Jorgensen P, Syk I, Smedh K, et al. Effect of more vs less frequent follow-up testing on overall and colorectal cancer-specific mortality in patients with stage II or III colorectal cancer: the COLOFOL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319(20):2095–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Primrose JN, Perera R, Gray A, et al. Effect of 3 to 5 years of scheduled CEA and CT follow-up to detect recurrence of colorectal cancer: the FACS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(3):263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laghi A, Iannaccone R, Bria E, et al. Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic colonography in the follow-up of colorectal cancer patients: a feasibility study. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(4):883–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosati G, Ambrosini G, Barni S, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus minimal surveillance of patients with resected Dukes B2-C colorectal carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(2):274–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohlsson B, Breland U, Ekberg H, Graffner H, Tranberg KG. Follow-up after curative surgery for colorectal carcinoma. Randomized comparison with no follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38(6):619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeffery M, Hickey BE, Hider PN. Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(1):CD002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Low RN, Barone RM, Lee MJ. Surveillance MR imaging is superior to serum tumor markers for detecting early tumor recurrence in patients with appendiceal cancer treated with surgical cytoreduction and HIPEC. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(4):1074–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoemaker D, Black R, Giles L, Toouli J. Yearly colonoscopy, liver CT, and chest radiography do not influence 5-year survival of colorectal cancer patients. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(1):7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Secco GB, Fardelli R, Gianquinto D, et al. Efficacy and cost of risk-adapted follow-up in patients after colorectal cancer surgery: a prospective, randomized and controlled trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28(4):418–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez-Moranta F, Salo J, Arcusa A, et al. Postoperative surveillance in patients with colorectal cancer who have undergone curative resection: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(3):386–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pietra N, Sarli L, Costi R, Ouchemi C, Grattarola M, Peracchia A. Role of follow-up in management of local recurrences of colorectal cancer: a prospective, randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(9):1127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Renehan AG, Egger M, Saunders MP, O’Dwyer ST. Impact on survival of intensive follow up after curative resection for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2002;324(7341):813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (U.S.). The complete library of NCCN oncology practice guidelines In: 2000. ed Rockledge, PA: NCCN; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carr NJ, Cecil TD, Mohamed F, et al. A consensus for classification and pathologic reporting of Pseudomyxoma peritonei and associated appendiceal neoplasia: the results of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) Modified Delphi Process. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(1):14–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakata K, Johnson FE, Beitler AL, Kraybill WG, Virgo KS. Extremity soft tissue sarcoma patient follow-up: tumor grade and size affect surveillance strategies after potentially curative surgery. Int J Oncol. 2003;22(6):1335–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen CT, Vicens-Rodriguez RA, Wagner-Bartak NA, et al. Multidetector CT detection of peritoneal metastases: evaluation of sensitivity between standard 2.5 mm axial imaging and maximum-intensity-projection (MIP) reconstructions. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(7):2167–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis RA, Neal RD, Hendry M, et al. Patients’ and healthcare professionals’ views of cancer follow-up: systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(564):e248–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCusker ME, Cote TR, Clegg LX, Sobin LH. Primary malignant neoplasms of the appendix: a population-based study from the surveillance, epidemiology and end-results program, 1973–1998. Cancer. 2002;94(12):3307–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amin MB, American Joint Committee on Cancer, American Cancer Society. AJCC cancer staging manual, 8th edn Amin MB, Edge SB, et al. (eds) Chicago: American Joint Committee on Cancer, Springer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raul S, Gonzalez M. Adenocarcinoma of colon. 2015; http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/colontumoradenocarcinoma.html. Accessed 20 Feb 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mirnezami R, Moran BJ, Harvey K, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for colorectal peritoneal metastases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(38):14018–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]