Abstract

Female infertility impacts the quality of life and well-being of affected individuals and couples. Female reproductive diseases, such as primary ovarian insufficiency, polycystic ovary syndrome, endometriosis, fallopian tube obstruction, and Asherman syndrome, can induce infertility. In recent years, translational medicine has developed rapidly, and clinical researchers are focusing on the treatment of female infertility using novel approaches. Owing to the advantages of convenient samples, abundant sources, and avoidable ethical issues, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can be applied widely in the clinic. This paper reviews recent advances in using four types of MSCs, bone marrow stromal cells, adipose-derived stem cells, menstrual blood mesenchymal stem cells, and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. Each of these have been used for the treatment of ovarian and uterine diseases, and provide new approaches for the treatment of female infertility.

1. Introduction

Infertility is defined as the failure to achieve any pregnancy (including a miscarriage) for at least 12 months [1]. In 2002, 7.4% of married women, or about 2.1 million women, were infertile in the United States [2]. The causes of infertility can be divided into three main categories for which the prevalence is variable: female causes (33 to 41%), male causes (25 to 39%), and mixed causes (9 to 39%) [3]. These statistics highlight the impressive numbers of women undergoing infertility.

There are many factors causing female infertility, among which reproductive system-related diseases are the main causes. Etiologies for female infertility include ovulation disorders (polycystic ovary syndrome, hypothalamic dysfunction, and primary ovarian insufficiency), tubal infertility, endometriosis, and uterine and cervical causes (cervical stenosis, polyps, and tumors). Hormone replacement therapy is effective in some types of infertility, but there is substantial evidence from observational studies that such therapy increases the risk of breast cancer [4, 5]. Ovulation induction, superovulation, or assisted reproductive technologies have shown trends toward increased pregnancy rates, though different factors relating to the increased risks for multiple pregnancies must be considered [6]. These findings indicate shortcomings of existing treatment regimens.

Scientists have investigated other therapeutic measures, such as stem cell therapy, for infertility. Stem cells are undifferentiated cells with the ability to renew themselves for long periods without significant changes in their general properties. They can differentiate into various specialized cell types under certain physiological or experimental conditions. Due to the limitations of using embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells in the clinic, there is great interest in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which are free of both ethical concerns and teratoma formation [7].

MSCs, also called mesenchymal stromal cells, are a subset of nonhematopoietic adult stem cells that originate from the mesoderm. They possess self-renewal abilities and multilineage differentiation into not only mesoderm lineages, such as chondrocytes, osteocytes, and adipocytes, but also ectodermic and endodermic cells [8–10]. MSCs can be harvested from several adult tissues, such as bone marrow, menstrual blood, adipose tissue, the umbilical cord, and placenta [11–15].

2. Causes of Infertility in Female Reproductive Organs

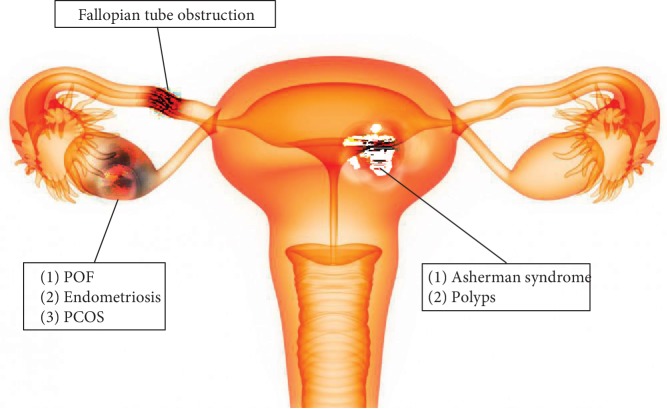

Causes of infertility in female reproductive organs include premature ovarian failure (POF), polycystic ovary syndrome, endometriosis, fallopian tube obstruction, Asherman syndrome, and other, less frequent anomalies of the reproductive tract (Figure 1, Table 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram showing some possible causes of female infertility, such as fallopian tube obstruction, premature ovarian failure (POF), endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), Asherman syndrome, and polyps.

Table 1.

Causes of infertility in female reproductive organs.

| Disease | Etiologies | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| POF | Genetic defects, autoimmune processes, chemotherapy, radiation, and infections | Cessation of ovarian function after menarche but before the age of 40, without or with ovarian follicle depletion |

|

| ||

| PCOS | Maternal PCOS, intrauterine hyperandrogenism, inflammatory adipokines, aboriginal origin-Western diet | A complex disorder characterized by infertility, hirsutism, obesity, and various menstrual disturbances |

|

| ||

| Endometriosis | Oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species, antioxidants and inflammatory, genetic, and epigenetic factors | A condition in which functional endometrial tissue is present outside the uterus |

|

| ||

| Fallopian tube obstruction | Neoplasms, neoplasms, tuboovarian abscess | Tubal obstruction is caused by inflammation of the fallopian tube or pelvic peritoneum |

|

| ||

| AS | Trauma, infection, low level of estradiol, repeated or aggressive curettage, severe endometritis | Absence of a normal opening in the lumen of the female genital tract, from the fallopian tubes to the vagina |

POF: premature ovarian failure; PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; AS: Asherman syndrome.

3. Mesenchymal Stem Cells

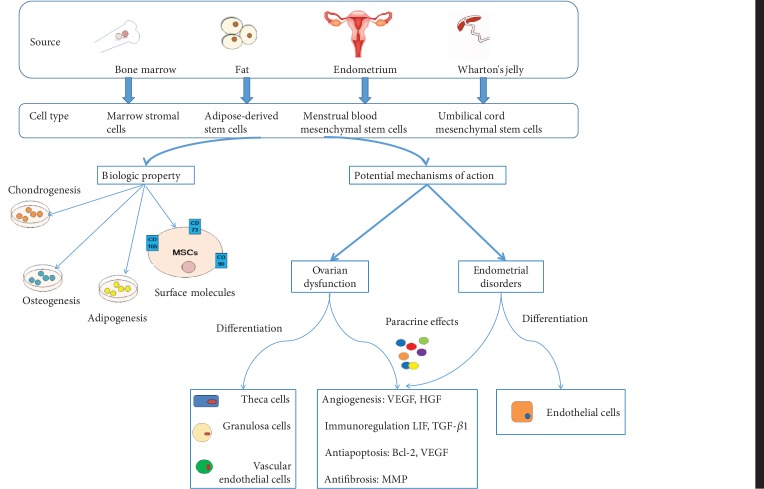

To begin to address the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), the Mesenchymal and Tissue Stem Cell Committee of the International Society for Cellular Therapy has proposed minimal criteria to define human MSCs. First, MSCs must be plastic-adherent when maintained in standard culture conditions. Second, MSCs must express CD105, CD73, and CD90, and lack expression of CD45, CD34, CD14 or CD11b, CD79a or CD19, and HLA-DR surface molecules. Third, MSCs must differentiate to osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondroblasts in vitro [8]. In 2016, the institute recommended adding MSC immunomodulation function-related factor detection as a supplementary test standard [16, 17]. The different MSCs are classified based on their source (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The derivation of the four types of MSCs and the biologic property of these MSCs. Potential mechanisms have been proposed for ovarian dysfunction and endometrial disorder therapy. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), transforming growth factor (TGF), B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP).

Laboratory experiments and clinical trials are now using MSCs, alone or in combination with other drugs, for potential application to ovarian dysfunction and endometrial disorders (Table 2) [18–21]. Importantly, therapeutic interventions for numerous diseases in female reproductive organs are causing great excitement. More importantly, these studies provide a desirable experimental model for elucidating the underlying mechanism of using MSCs for treating female infertility. This provides the theoretical basis for further studies and clinical therapy with MSCs.

Table 2.

Application of MSC therapy in the treatment of female reproductive dysfunction.

| MSC types | Disease | Treatment | Model | Main results | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow stromal cells | Ovarian dysfunction | CTX-induced ovarian failure | Intravenous injection | Rabbit | Ovarian function ↑ | 31 |

| CTX-induced ovarian failure | Local injection | Mice | Restore ovarian hormone production | 34 | ||

| Endometrial disorders | 24-gauge needle-induced AS | Labeled with SPIOs local/tail vein injection | Mice | Endometrial proliferation ↑ | 41 | |

| Refractory AS | Uterine artery injection | Human | Reconstruct the endometrium | 40 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Adipose-derived stem cells | Ovarian dysfunction | Cisplatin-induced ovarian failure | Local injection | Mice | Ovarian function ↑ | 49 |

| TG-induced ovarian damage | Collagen scaffold | Rat | Fertility ↑ | 51 | ||

| Endometrial disorders | Trichloroacetic acid-induced AS | Intraperitoneal injection | Rat | Fibrosis ↓, endometrial proliferation ↑ | 52 | |

|

| ||||||

| MB-MSCs | Ovarian dysfunction | CTX-induced POF | Local injection | Mice | Ovarian weight ↑, hormone secretion ↓ | 59 |

| Cisplatin-induced POF | Local injection | Mice | Ovarian function ↑, fibroblast growth factor 2 ↑ | 62 | ||

| Endometrial disorders | Severe AS | Deliver through the cervix to the fundus of the uterus | Human | Endometrial thickness ↑ | 70 | |

| Mechanical injured-induced intrauterine adhesion | Local injection | Rat | Pregnancy rate ↑ | 77 | ||

|

| ||||||

| UC-MSCs | Ovarian dysfunction | CTX-induced POF | Tail vein injection | Mice | Weight of the ovaries ↑, estradiol ↑, | 80 |

| Paclitaxel-induced POF | Local injection | Rat | Follicle-stimulating hormone ↓, estradiol ↑, ovarian function ↑ | 81 | ||

| Perimenopausal ovary | Tail vein injection | Rat | Estradiol ↑, follicle-stimulating hormone ↓, follicle number ↑ | 85 | ||

| Busulfan CTX-induced premature ovarian insufficiency | Local injection | Mice | Fertility ↑, ovarian functions ↑ | 77 | ||

| Endometrial disorders | Uterine niche | Local intramuscular injection | Human | Uterine scar reconstruction ↑, uterine niche incidence ↓ | 91 | |

| 95% ethanol-induced endometrial injury | Tail vein injection | Rat | Fertility ↑, endometrial fibrosis ↓, angiogenesis ↑ | 87 | ||

CTX: cyclophosphamide; TG: tripterygium glycosides; ↑: increase; ↓: decrease.

For ovarian dysfunction, MSCs can directly and impulsively migrate to the injured ovary and survive there under the stimulation of multiple factors, which facilitates ovarian recovery. According to available studies, the number of differentiated and functionally integrated MSCs is too small to explain the observed improvements in ovarian function. Furthermore, whether MSCs differentiate into oocytes after migrating to injured tissue is still unknown. Improved ovarian function in these studies might be driven by paracrine mechanisms. These mechanisms involve the secretion of certain cytokines, including vascular endothelial growth factor, insulin-like growth factor, and hepatocyte growth factor, which are helpful for angiogenesis, anti-inflammation, immunoregulation, antiapoptosis, and antifibrosis to help ovarian restoration.

Further studies are needed to explore whether MSCs differentiate into target cells such as oocytes or supporting cells that improve ovarian functions and ultimately correct ovarian dysfunction. Such differentiation would also be valuable for MSC transplantation applied as a clinical therapy. Similarly, MSCs improve the endometrial reserve, which mainly depends on homing and paracrine activities. In studies to date, it is widely accepted that the paracrine effect of MSCs is the most important, rather than differentiation. Specifically, the regenerative properties of transplanted MSCs can be attributed to mechanisms that involve cell-cell contact and secretion of bioactive molecules that promote angiogenesis and tissue repair, thereby inhibiting scarring, modulating inflammatory and immune reactions, and activating tissue-specific progenitor cells. However, other research suggests that MSCs engraft the endometrium in rodents and humans, where they become epithelial, stromal, and endothelial cells. Thus, MSCs might promote endometrial regeneration and restore fertility by paracrine factors, but other mechanisms are plausible.

3.1. Bone Marrow Stromal Cells

Initially described by Owen and Friedenstein in 1988 [22], bone marrow stromal cells were separated from nucleated bone marrow cells on plastic culture dishes by density gradient centrifugation [23]. These cells had a longer replication cycle and premature senility, accounting for only 0.01–0.001% of nucleated bone marrow cells [24]. Bone marrow stromal cells, which have been the main source of multipotent stem cells, serve as a standard for comparison with MSCs from other sources [25]. Bone marrow stromal cells not only commit to osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondroblasts, but also differentiate into granulosa [26], endometrial [27, 28], and endothelial cells [29] in mammals. Furthermore, bone marrow stromal cells have broad application prospects in the field of regenerative medicine, including reproductive dysfunction [30].

3.1.1. Application of Bone Marrow Stromal Cells to Treat Ovarian Dysfunction

Several studies have shown beneficial effects of bone marrow stromal cell treatment in a chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure animal model. Specifically, the results showed that ovarian structure and functions could be restored by bone marrow stromal cells [31–34]. Although chemotherapy drugs can inhibit the growth of tumor cells, they can also lead to granulosa cell apoptosis, follicular atresia, ovarian function decline, and other manifestations of premature ovarian failure. Granulosa cells, which are located on the lateral side of the oocyte zona pellucidum and secrete estrogen under the action of follicle-stimulating hormone and other paracrine factors, play a role in nutrition and support of oocytes. Granulosa cell apoptosis thus leads to a decrease in estrogen levels in the body, affecting the normal development of oocytes.

In 2013, Abd-Allah et al. used bone marrow stromal cells from male rabbits to treat cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian failure and discovered that the ovarian functional reserve and number of follicles were improved. In addition, there were increased estrogen and vascular endothelial growth factor levels, reduced follicle-stimulating hormone levels, and diminished caspase-3 expression [31]. Badawy et al., in 2017, showed that bone marrow stromal cells were able to restore ovaries damaged by chemotherapy in mice. Furthermore, the animals regained their fertility [32]. Another study found that bone marrow stromal cells overexpressed miR-21, the earliest discovered microRNA, and this microRNA improved chemotherapy-induced POF in rats, possibly by downregulating phosphatase and tensin homolog and programmed cell death protein 4 to decrease granulosa cell apoptosis [33].

3.1.2. Application of Bone Marrow Stromal Cells to Treat Endometrial Disorders

The uterine endometrium is a dynamic tissue that consists of a glandular epithelium and stroma that undergoes regeneration in each reproductive cycle. The uterine endometrium can be structurally divided into two zones: the upper functional layer and lower basal layer, which regenerates a new functional layer according to fluctuating levels of estrogen and progesterone. In humans, bone marrow stromal cells identified in the uterine endometrium participate in the regeneration of endometrial tissue [35, 36]. Implantation of autologous bone marrow stromal cells to treat endometrial injury restored menstruation in five out of six cases [37]. In animal models, bone marrow stromal cells have been used successfully to treat thin endometrium by locating them in this tissue where they differentiated into numerous cells and exerted immunomodulatory effects [27]. Additionally, bone marrow stromal cells restored functional endometrium in patients with Asherman syndrome and improved the reproductive outcomes [27, 38, 39].

In both preclinical animal models and human clinical trials, CD133+ bone marrow stromal cells induce endometrial proliferation by engrafting around endometrial vessels of the traumatized endometrium and secreting specific growth factors, such as thrombospondin-1 and insulin-like growth factor-1 [40, 41]. To better compensate for the insufficient intrinsic regeneration ability of the endometrium, inhibit fibrosis, promote angiogenesis, and improve endometrial receptivity, collagen scaffolds with bone marrow stromal cells have been introduced into treatments for Asherman syndrome [42].

3.2. Adipose-Derived Stem Cells

Currently, adipose-derived stem cells, a new type of MSC, have been used primarily to repair tissues [43–45]. Although these cells have the same biologic characteristics as bone marrow stromal cells [46], they are easier to isolate in large quantities (by minimally invasive liposuction) than bone marrow stromal cells [47]. Thus, compared with bone marrow stromal cells, adipose-derived stem cells represent a more practical option.

Damous et al. demonstrated that adipose-derived stem cell therapy improved ovarian graft quality by promoting an increase in vascular endothelial growth factor-A gene expression and the number of blood vessels in ovarian tissue to induce an earlier resumption of function in freshly grafted ovaries of adult female rats [48]. In addition, adipose-derived stem cells ameliorated chemotherapy-induced ovarian dysfunction in mouse models and were capable of inducing angiogenesis and restoring the number of ovarian follicles and corpus luteum in damaged ovaries [49, 50]. Another experiment, using a rat model of premature ovarian insufficiency, verified that adding a collagen scaffold enhanced the short-term maintenance of adipose-derived stem cells in ovaries, compared with transplanting these cells alone [51]. In another experimental rat model, the use of estrogen in combination with adipose-derived stem cells efficiently induced regeneration of the endometrium in Asherman syndrome therapy [52].

3.3. Menstrual Blood Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MB-MSCs)

Menstrual blood mesenchymal stem cells (MB-MSCs) can be isolated from menstrual blood [12]. These cells have high proliferative, self-renewal, and multiple differentiation potentials. In addition, they appear to possess numerous advantages over stem cells derived from other sources including ease of collection, safe and noninvasive proliferation, no ethical concerns, and no autoimmune rejection responses [12, 53]. Some clinical trials have used MB-MSCs to treat neuronal diseases [54, 55], diabetes mellitus [56, 57], and multiple sclerosis [53].

3.3.1. Application of MB-MSCs to Treat Ovarian Dysfunction

Several studies have shown that MB-MSCs reduce apoptosis in granulosa cells and fibrosis of the ovarian interstitium, thereby improving folliculogenesis and rescuing overall ovarian function in an animal model of POF [58, 59], including restoring fertility [60]. In addition, Wang et al. demonstrated that MB-MSCs produced a high level of fibroblast growth factor 2, which enhanced cell survival, proliferation, and function to repair tissue damage [61, 62]. Furthermore, Yan et al. indicated that MB-MSCs reduced granulosa cell apoptosis and improved ovarian functions in mice by downregulating Gadd45b protein expression (a stress sensor whose effects are mediated via physical interactions with other cellular proteins implicated in cell cycle regulation) and upregulating cyclinB1 and CDC2 (regulators of the G2/M transition in mammalian cells) [63–66].

3.3.2. Application of MB-MSCs to Treat Endometrial Disorders

MB-MSCs isolated from ectopic endometriotic lesions contribute to the pathogenesis of endometriosis [67, 68]. A clinical study where autologous MB-MSCs were transplanted into seven patients with severe Asherman syndrome, followed by hormonal stimulation, showed that the thickness of the endometrium in five women reached 7 mm, one patient had a spontaneous pregnancy, and two of the remaining four patients undergoing embryo transfer became pregnant [69].

In rats with damaged endometrium (an Asherman syndrome model), transplanted MB-MSCs assembled into spheroids and significantly improved fertility by increasing the synthesis of angiogenic and anti-inflammatory factors [70]. The main properties of MB-MSCs were retained in the spheroids, except for the expression of CD146 that was negatively correlated with self-renewal ability [71]. This seems to be a key to improve the therapeutic effect of MB-MSCs organized into spheroids.

Zheng et al. were the first to show that MB-MSCs could differentiate into endometrial cells in vitro and rebuild endometrial tissue in NOD-SCID mice after administering estrogen and progesterone in vivo [72]. As a transcription factor, OCT-4-positive cells can differentiate into three germ layers [73]. Furthermore, the cloning efficiency and OCT-4 expression of MB-MSCs from patients with severe intrauterine adhesions were significantly decreased compared with controls [72].

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), an autologous plasma product with platelet concentrations above baseline values, has been used to treat acute and chronic injuries [74, 75]. Zhang et al. compared placebo, MB-MSC transplantation, PRP transplantation, and combined MB-MSC and PRP transplantation in the treatment of a rat model of intrauterine adhesion [76]. They found that combining MB-MSCs with PRP was more effective than either treatment alone in improving endometrial proliferation, angiogenesis, and morphological recovery. This treatment also reduced fibrosis and inflammation by changing the Hippo signaling pathway and regulating the downstream factors, connective tissue growth factor, Wnt5a, and Gdf5.

3.4. Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UC-MSCs), isolated directly from Wharton's jelly of the UC, are called human Wharton's jelly MSCs. They express the MSC markers CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, and CD105, and do not express CD31, CD45, and HLA-DR85. Because they have lower oncogenicity and faster self-renewal abilities compared to other sources of MSCs, UC-MSCs are a new source of stem cells that can differentiate into several mesodermal cell types and be used for cell therapy.

3.4.1. Application of UC-MSCs to Treat Ovarian Dysfunction

UC-MSCs have been used in several animal models to successfully treat POF by reducing apoptosis of granulosa cells, decreasing follicle-stimulating hormone serum levels, and increasing estrogen and anti-Mullerian hormone levels [77–80]. Elfayomy et al. proposed that UC-MSCs could reverse paclitaxel-induced apoptosis of ovarian cells either by establishing a normal arrangement of the surface epithelium and tunica albuginea, or by upregulating cytokeratin 8/18, transforming growth factor-β, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen to suppress caspase-3 expression [81]. In another investigation, Jalalie et al. transplanted CM-Dil-labeled human UC-MSCs into cyclophosphamide-injured ovaries in mice [82]. They found that UC-MSCs were not distributed equally in different parts of the ovarian tissue. Specifically, the number of CM-Dil-labeled human UC-MSCs in the ovarian medulla was greater than those of the ovarian cortex and germinal epithelium.

UC-MSCs on a collagen scaffold have been transplanted into ovaries to treat POF [83, 84]. Ding et al. found that this technique activated primordial follicles in vitro via phosphorylation of FOXO3a, a major suppressor of primordial follicle activation, and FOXO1. Li et al. found that human UC-MSCs used to treat perimenopausal rats secreted cytokines, such as hepatocyte growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and insulin-like growth factor-1, resulting in improved ovarian reserve functions [85].

3.4.2. Application of UC-MSCs to Treat Endometrial Disorders

Wharton's jelly-derived MSCs have the ability to differentiate into endometrial cells [86]. In a rat model, Zhang et al. found that human UC-MSCs repaired injured endometrium, thereby improving fertility. These researchers also found that the number of implanted embryos was higher in groups with multiple UC-MSC transplantations compared to a single UC-MSC transplantation, by upregulating vascular and downregulating proinflammatory factors [87]. Furthermore, UC-MSCs in collagen scaffolds have been used to promote endometrial regeneration by upregulating matrix metalloproteinase-9 in rat uterine scars [88, 89].

UC-MSCs can ameliorate damage to human endometrial stromal cells [90], and local intramuscular injection is effective for treating uterine niches after cesarean delivery [91]. Additionally, UC-MSCs on collagen scaffolds have been used in a phase I clinical trial to treat patients with recurrent uterine adhesions. The results suggested that they can improve endometrial proliferation, differentiation, and neovascularization by upregulating estrogen receptor α, vimentin, Ki67, and von Willebrand factor expression levels, and downregulating the ΔNP63 expression level [92].

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

MSCs have demonstrated great potential and availability for treating female infertility in animal and human studies. Autologous adipose-derived stem cells are especially useful because they are not only easily obtained, but also avoid graft rejection after transplantation. In recent decades, autologous adipose-derived stem cell transplantation or injection have shown positive effects on rat models of POF and Asherman syndrome and can increase fertilization rates. However, there are several main directions for using MSC to treat infertile women caused by ovarian or uterine factors: (1) Most studies have been done on small animals, and there is a serious lack of valuable research in large animal models that more closely mimic the ovarian or endometrial pathophysiology of human female infertility. Furthermore, a randomized controlled trial should be conducted to confirm the therapeutic effect of MSCs in fertility medicine. (2) The mechanism of MSCs in treating dysfunction of female reproductive organs is still unknown. Possibilities include promoting angiogenesis, differentiating into functional cells, and a paracrine mechanism. Among these, a paracrine mechanism might be the most important for female infertility treatment. However, beneficial paracrine factors remain unknown and multiple mechanisms may be synergistic. (3) While MSC therapy is promising, the limited survival and engraftment of bioactive agents due to a hostile environment is a bottleneck for disease treatment. Therefore, how to maintain and enhance the survival and secretion of MSCs over a longer period of time requires more in-depth research. One approach that maximizes the utility of MSCs for ovarian and endometrial disorders has been the development of various types of biomaterials. Collagen-based biomaterials have already been used as MSC delivery vehicles to enhance cell adhesion, retention, and engraftment. Nevertheless, additional work is needed to optimize this approach.

Contributor Information

Qi-yang Shi, Email: wsqy214@163.com.

Shu Lin, Email: shulin1956@126.com.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

This work was supported by SWH2018LJ-12 and 2018N019S.

References

- 1.Hull M. G., Glazener C. M., Kelly N. J., et al. Population study of causes, treatment, and outcome of infertility. BMJ. 1985;291(6510):1693–1697. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6510.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandra A., Martinez G. M., Mosher W. D., Abma J. C., Jones J. Fertility, family planning, and reproductive health of U.S. women; data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital and Health Statistics. 2005;23(25):1–160. doi: 10.1037/e414702008-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deroux A., Dumestre-Perard C., Dunand-Faure C., Bouillet L., Hoffmann P. Female infertility and serum auto-antibodies: a systematic review. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2017;53(1):78–86. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8586-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmberg L., Iversen O. E., Rudenstam C. M., et al. Increased risk of recurrence after hormone replacement therapy in breast cancer survivors. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100(7):475–482. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vermeulen R. F. M., Korse C. M., Kenter G. G., Brood-van Zanten M. M. A., van Beurden M. Safety of hormone replacement therapy following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy: systematic review of literature and guidelines. Climacteric. 2019;22(4):352–360. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2019.1582622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Multiple gestation associated with infertility therapy: an American Society for Reproductive Medicine Practice Committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility. 2012;97(4):825–834. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blum B., Benvenisty N. The tumorigenicity of human embryonic stem cells. Advances in Cancer Research. 2008;100(8):133–158. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(08)00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominici M., Le Blanc K., Mueller I., et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dezawa M., Ishikawa H., Itokazu Y., et al. Bone marrow stromal cells generate muscle cells and repair muscle degeneration. Science. 2005;309(5732):314–317. doi: 10.1126/science.1110364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salem H. K., Thiemermann C. Mesenchymal stromal cells: current understanding and clinical status. Stem Cells. 2010;28(3):585–596. doi: 10.1002/stem.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Körbling M., Anderlini P. Peripheral blood stem cell versus bone marrow allotransplantation: does the source of hematopoietic stem cells matter? Blood. 2001;98(10):2900–2908. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.10.2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng X., Ichim T. E., Zhong J., et al. Endometrial regenerative cells: a novel stem cell population. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2007;5(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barry F. P., Murphy J. M. Mesenchymal stem cells: clinical applications and biological characterization. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2004;36(4):568–584. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee O. K., Kuo T. K., Chen W.-M., Lee K.-D., Hsieh S.-L., Chen T.-H. Isolation of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2004;103(5):1669–1675. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.in’t Anker P. S., Scherjon S. A., der Keur C. K.-v., et al. Isolation of mesenchymal stem cells of fetal or maternal origin from human placenta. Stem Cells. 2004;22(7):1338–1345. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krampera M., Galipeau J., Shi Y., Tarte K., Sensebe L., MSC Committee of the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) Immunological characterization of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells--The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) working proposal. Cytotherapy. 2013;15(9):1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galipeau J., Krampera M., Barrett J., et al. International Society for Cellular Therapy perspective on immune functional assays for mesenchymal stromal cells as potency release criterion for advanced phase clinical trials. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(2):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naji A., Rouas-Freiss N., Durrbach A., Carosella E. D., Sensébé L., Deschaseaux F. Concise review: combining human leukocyte antigen G and mesenchymal stem cells for immunosuppressant biotherapy. Stem Cells. 2013;31(11):2296–2303. doi: 10.1002/stem.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Squillaro T., Peluso G., Galderisi U. Clinical trials with mesenchymal stem cells: an update. Cell Transplantation. 2016;25(5):829–848. doi: 10.3727/096368915X689622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galipeau J., Sensébé L. Mesenchymal stromal cells: clinical challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22(6):824–833. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trounson A., McDonald C. Stem cell therapies in clinical trials: progress and challenges. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen M., Friedenstein A. J. Stromal stem cells: marrow-derived osteogenic precursors. Ciba Foundation Symposium. 1988;136:42–60. doi: 10.1002/9780470513637.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altaner C., Altanerova V., Cihova M., et al. Characterization of mesenchymal stem cells of “no-options” patients with critical limb ischemia treated by autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(9, article e73722):9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yun Cheng H. The impact of mesenchymal stem cell source on proliferation, differentiation, immunomodulation and therapeutic efficacy. Journal of Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2014;04(10) doi: 10.4172/2157-7633.1000237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ullah I., Subbarao R. B., Rho G. J. Human mesenchymal stem cells - current trends and future prospective. Bioscience Reports. 2015;35(2):1–18. doi: 10.1042/bsr20150025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Besikcioglu H. E., Sarıbas G. S., Ozogul C., et al. Determination of the effects of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells and ovarian stromal stem cells on follicular maturation in cyclophosphamide induced ovarian failure in rats. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;58(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao L., Huang Z., Lin H., Tian Y., Li P., Lin S. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) restore functional endometrium in the rat model for severe Asherman syndrome. Reproductive Sciences. 2019;26(3):436–444. doi: 10.1177/1933719118799201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y., Tal R., Pluchino N., Mamillapalli R., Taylor H. S. Systemic administration of bone marrow-derived cells leads to better uterine engraftment than use of uterine-derived cells or local injection. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2018;22(1):67–76. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tepper O. M., Sealove B. A., Murayama T., Asahara T. Newly emerging concepts in blood vessel growth: recent discovery of endothelial progenitor cells and their function in tissue regeneration. Journal of Investigative Medicine. 2003;51(6):353–359. doi: 10.1136/jim-51-06-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei X., Yang X., Han Z. P., Qu F. F., Shao L., Shi Y. F. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new trend for cell therapy. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2013;34(6):747–754. doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abd-Allah S. H., Shalaby S. M., Pasha H. F., et al. Mechanistic action of mesenchymal stem cell injection in the treatment of chemically induced ovarian failure in rabbits. Cytotherapy. 2013;15(1):64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badawy A., Sobh M. A., Ahdy M., Abdelhafez M. S. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell repair of cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian insufficiency in a mouse model. International Journal of Women's Health. 2017;9:441–447. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S134074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fu X., He Y., Wang X., et al. Overexpression of miR-21 in stem cells improves ovarian structure and function in rats with chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage by targeting PDCD4 and PTEN to inhibit granulosa cell apoptosis. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2017;8(1):p. 187. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0641-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohamed S. A., Shalaby S. M., Abdelaziz M., et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells partially reverse infertility in chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure. Reproductive Sciences. 2018;25(1):51–63. doi: 10.1177/1933719117699705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor H. S. Endometrial cells derived from donor stem cells in bone marrow transplant recipients. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(1):81–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panchal S., Patel H., Nagori C. Endometrial regeneration using autologous adult stem cells followed by conception by in vitro fertilization in a patient of severe Asherman’s syndrome. Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences. 2011;4(1):43–48. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.82360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh N., Mohanty S., Seth T., Shankar M., Dharmendra S., Bhaskaran S. Autologous stem cell transplantation in refractory Asherman’s syndrome: a novel cell based therapy. Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences. 2014;7(2):93–98. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.138864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alawadhi F., Du H., Cakmak H., Taylor H. S. Bone marrow-derived stem cell (BMDSC) transplantation improves fertility in a murine model of Asherman’s syndrome. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96662–e96666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J., Ju B., Pan C., et al. Application of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of intrauterine adhesions in rats. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2016;39(4):1553–1560. doi: 10.1159/000447857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santamaria X., Cabanillas S., Cervelló I., et al. Autologous cell therapy with CD133+ bone marrow-derived stem cells for refractory Asherman’s syndrome and endometrial atrophy: a pilot cohort study. Human Reproduction. 2016;31(5):1087–1096. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cervelló I., Gil-Sanchis C., Santamaría X., et al. Human CD133+ bone marrow-derived stem cells promote endometrial proliferation in a murine model of Asherman syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2015;104(6):1552–1560.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao G., Cao Y., Zhu X., et al. Transplantation of collagen scaffold with autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells promotes functional endometrium reconstruction via downregulating ΔNp63 expression in Asherman’s syndrome. Science China Life Sciences. 2017;60(4):404–416. doi: 10.1007/s11427-016-0328-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lendeckel S., Jödicke A., Christophis P., et al. Autologous stem cells (adipose) and fibrin glue used to treat widespread traumatic calvarial defects: case report. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery. 2004;32(6):370–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang J.-A., Chung H.-M., Won C.-H., Sung J.-H. Potential application of adipose-derived stem cells and their secretory factors to skin: discussion from both clinical and industrial viewpoints. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2010;10(4):495–503. doi: 10.1517/14712591003610598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ra J. C., Jeong E. C., Kang S. K., Lee S. J., Choi K. H. A prospective, nonrandomized, no placebo-controlled, phase I/II clinical trial assessing the safety and efficacy of intramuscular injection of autologous adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells in patients with severe Buerger’s disease. Cell Medicine. 2017;9(3):87–102. doi: 10.3727/215517916X693069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee R. H., Kim B. C., Choi I. S., et al. Characterization and expression analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow and adipose tissue. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2004;14(4–6):311–324. doi: 10.1159/000080341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choudhery M. S., Badowski M., Muise A., Pierce J., Harris D. T. Donor age negatively impacts adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell expansion and differentiation. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2014;12(1):8–14. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Damous L. L., Nakamuta J. S., Saturi de Carvalho A. E. T., et al. Does adipose tissue-derived stem cell therapy improve graft quality in freshly grafted ovaries? Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2015;13(1, article 104):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0104-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Terraciano P., Garcez T., Ayres L., et al. Cell therapy for chemically induced ovarian failure in mice. Stem Cells International. 2014;2014:8. doi: 10.1155/2014/720753.720753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun M., Wang S., Li Y., et al. Adipose-derived stem cells improved mouse ovary function after chemotherapy-induced ovary failure. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2013;4(4):p. 80. doi: 10.1186/scrt231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Su J., Ding L., Cheng J., et al. Transplantation of adipose-derived stem cells combined with collagen scaffolds restores ovarian function in a rat model of premature ovarian insufficiency. Human Reproduction. 2016;31(5):1075–1086. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kilic S., Yuksel B., Pinarli F., Albayrak A., Boztok B., Delibasi T. Effect of stem cell application on Asherman syndrome, an experimental rat model. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2014;31(8):975–982. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0268-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhong Z., Patel A. N., Ichim T. E., et al. Feasibility investigation of allogeneic endometrial regenerative cells. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2009;7(1):15–17. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolff E. F., Mutlu L., Massasa E. E., Elsworth J. D., Eugene Redmond D., Jr., Taylor H. S. Endometrial stem cell transplantation in MPTP- exposed primates: an alternative cell source for treatment of Parkinson's disease. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2015;19(1):249–256. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolff E. F., Gao X. B., Yao K. V., et al. Endometrial stem cell transplantation restores dopamine production in a Parkinson’s disease model. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2011;15(4):747–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Santamaria X., Massasa E. E., Feng Y., Wolff E., Taylor H. S. Derivation of insulin producing cells from human endometrial stromal stem cells and use in the treatment of murine diabetes. Molecular Therapy. 2011;19(11):2065–2071. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li H.-Y., Chen Y.-J., Chen S.-J., et al. Induction of insulin-producing cells derived from endometrial mesenchymal stem-like cells. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2010;335(3):817–829. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.169284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu T., Huang Y., Zhang J., et al. Transplantation of human menstrual blood stem cells to treat premature ovarian failure in mouse model. Stem Cells and Development. 2014;23(13):1548–1557. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manshadi M. D., Navid S., Hoshino Y., Daneshi E., Noory P., Abbasi M. The effects of human menstrual blood stem cells-derived granulosa cells on ovarian follicle formation in a rat model of premature ovarian failure. Microscopy Research and Technique. 2019;82(6):635–642. doi: 10.1002/jemt.23120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lai D., Wang F., Yao X., Zhang Q., Wu X., Xiang C. Human endometrial mesenchymal stem cells restore ovarian function through improving the renewal of germline stem cells in a mouse model of premature ovarian failure. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2015;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0516-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Z., Wang Y., Yang T., Li J., Yang X. Study of the reparative effects of menstrual-derived stem cells on premature ovarian failure in mice. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2017;8(1):11–14. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0458-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Momose T., Miyaji H., Kato A., et al. Collagen hydrogel scaffold and fibroblast growth factor-2 accelerate periodontal healing of class II furcation defects in dog. The Open Dentistry Journal. 2016;10(1):347–359. doi: 10.2174/1874210601610010347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liebermann D. A., Tront J. S., Sha X., Mukherjee K., Mohamed-Hadley A., Hoffman B. Gadd45 stress sensors in malignancy and leukemia. Critical Reviews in Oncogenesis. 2011;16(1–2):129–140. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v16.i1-2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hyka-Nouspikel N., Desmarais J., Gokhale P. J., et al. Deficient DNA damage response and cell cycle checkpoints lead to accumulation of point mutations in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30(9):1901–1910. doi: 10.1002/stem.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao Y., Lou I. C., Conolly R. B. Computational modeling of signaling pathways mediating cell cycle checkpoint control and apoptotic responses to ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage. Dose-Response. 2012;10(2):251–273. doi: 10.2203/dose-response.11-021.Zhao. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yan Z., Guo F., Yuan Q., et al. Endometrial mesenchymal stem cells isolated from menstrual blood repaired epirubicin-induced damage to human ovarian granulosa cells by inhibiting the expression of Gadd45b in cell cycle pathway. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2019;10(1):4–10. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1101-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kao A. P., Wang K. H., Chang C. C., et al. Comparative study of human eutopic and ectopic endometrial mesenchymal stem cells and the development of an in vivo endometriotic invasion model. Fertility and Sterility. 2011;95(4):1308–1315.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chan R. W. S., Ng E. H. Y., Yeung W. S. B. Identification of cells with colony-forming activity, self-renewal capacity, and multipotency in ovarian endometriosis. The American Journal of Pathology. 2011;178(6):2832–2844. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tan J., Li P., Wang Q., et al. Autologous menstrual blood-derived stromal cells transplantation for severe Asherman’s syndrome. Human Reproduction. 2016;31(12):2723–2729. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Domnina A., Novikova P., Obidina J., et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells in spheroids improve fertility in model animals with damaged endometrium. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2018;9(1) doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0801-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Paduano F., Marrelli M., Palmieri F., Tatullo M. CD146 expression influences periapical cyst mesenchymal stem cell properties. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. 2016;12(5):592–603. doi: 10.1007/s12015-016-9674-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zheng S. X., Wang J., Wang X. L., Ali A., Wu L. M., Liu Y. S. Feasibility analysis of treating severe intrauterine adhesions by transplanting menstrual blood-derived stem cells. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2018;41(4):2201–2212. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Golestaneh N., Kokkinaki M., Pant D., et al. Pluripotent stem cells derived from adult human testes. Stem Cells and Development. 2009;18(8):1115–1126. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gobbi A., Fishman M. Platelet-rich plasma and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in sports medicine. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review. 2016;24(2):69–73. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wei B., Huang C., Zhao M., et al. Effect of mesenchymal stem cells and platelet-rich plasma on the bone healing of ovariectomized rats. Stem Cells International. 2016;2016:11. doi: 10.1155/2016/9458396.9458396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang S., Li P., Yuan Z., Tan J. Platelet-rich plasma improves therapeutic effects of menstrual blood-derived stromal cells in rat model of intrauterine adhesion. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2019;10(1) doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1155-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mohamed S., Shalaby S., Brakta S., Elam L., Elsharoud A., Al-Hendy A. Umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells as an infertility treatment for chemotherapy induced premature ovarian insufficiency. Biomedicines. 2019;7(1):p. 7. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines7010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Song D., Zhong Y., Qian C., et al. Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Therapy in Cyclophosphamide- Induced Premature Ovarian Failure Rat Model. BioMed Research International. 2016;2016:13. doi: 10.1155/2016/2517514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhu S. F., Hu H. B., Xu H. Y., et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transplantation restores damaged ovaries. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2015;19(9):2108–2117. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang S., Yu L., Sun M., et al. The therapeutic potential of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in mice premature ovarian failure. BioMed Research International. 2013;2013:12. doi: 10.1155/2013/690491.690491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Elfayomy A. K., Almasry S. M., El-Tarhouny S. A., Eldomiaty M. A. Human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells transplantation renovates the ovarian surface epithelium in a rat model of premature ovarian failure: possible direct and indirect effects. Tissue & Cell. 2016;48(4):370–382. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jalalie L., Rezaie M. J., Jalili A., et al. Distribution of the CM-Dil-labeled human umbilical cord vein mesenchymal stem cells migrated to the cyclophosphamide-injured ovaries in C57BL/6 mice. Iranian Biomedical Journal. 2019;23(3):200–208. doi: 10.29252/.23.3.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ding L., Yan G., Wang B., et al. Transplantation of UC-MSCs on collagen scaffold activates follicles in dormant ovaries of POF patients with long history of infertility. Science China Life Sciences. 2018;61(12):1554–1565. doi: 10.1007/s11427-017-9272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang Y., Lei L., Wang S., et al. Transplantation of umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells on a collagen scaffold improves ovarian function in a premature ovarian failure model of mice. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Animal. 2019;55(4):302–311. doi: 10.1007/s11626-019-00337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li J., Mao Q. X., He J. J., She H. Q., Zhang Z., Yin C. Y. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells improve the reserve function of perimenopausal ovary via a paracrine mechanism. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2017;8(1) doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0514-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shi Q., Gao J. W., Jiang Y., et al. Differentiation of human umbilical cord Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells into endometrial cells. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2017;8(1) doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0700-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang L., Li Y., Guan C. Y., et al. Therapeutic effect of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells on injured rat endometrium during its chronic phase. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2018;9(1) doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0777-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xin L., Lin X., Pan Y., et al. A collagen scaffold loaded with human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells facilitates endometrial regeneration and restores fertility. Acta Biomaterialia. 2019;92:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xu L., Ding L., Wang L., et al. Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells on scaffolds facilitate collagen degradation via upregulation of MMP-9 in rat uterine scars. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2017;8(1) doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0535-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang X., Zhang M., Zhang Y., Li W., Yang B. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from Wharton jelly of the human umbilical cord ameliorate damage to human endometrial stromal cells. Fertility and Sterility. 2011;96(4):1029–1036.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fan D., Wu S., Ye S., Wang W., Guo X., Liu Z. Umbilical cord mesenchyme stem cell local intramuscular injection for treatment of uterine niche. Medicine. 2017;96(44):p. e8480. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cao Y., Sun H., Zhu H., et al. Allogeneic cell therapy using umbilical cord MSCs on collagen scaffolds for patients with recurrent uterine adhesion: a phase I clinical trial. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2018;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0904-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]