Abstract

Background

Behavior change communication (BCC) to improve health and caring practices is an integral component of efforts to improve maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH). Mobile phones are widely available in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), presenting new opportunities for BCC delivery. There is need for delivery science to determine how best to leverage mobile phone technology for BCC to improve MNCH practices.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of studies and project reports documenting the feasibility, implementation or effectiveness of using mobile phones for BCC delivery related to MNCH in LMIC. Data were extracted and synthesized from three sources: i) systematic search of three electronic databases (PubMed, MedLine, Scopus); ii) grey literature search, including mHealth databases and websites of organizations implementing mHealth projects; iii) consultation with researchers and programme implementers. Records were screened using pre-determined inclusion criteria and those selected were categorized according to their primary intervention delivery approaches. We then performed a descriptive analysis of the evidence related to both effectiveness and implementation for each delivery approach.

Results

The systematic literature search identified 1374 unique records, 64 of which met inclusion criteria. The grey literature search added 32 records for a total of 96 papers in the scoping review. Content analysis of the search results identified four BCC delivery approaches: direct messaging, voice counseling, job aid applications and interactive media. Evidence for the effectiveness of these approaches is growing but remains limited for many MNCH outcomes. The four approaches differ in key implementation elements, including frequency, length and complexity of communication, and potential for personalization. These elements influence resource allocation and are likely to impact effectiveness for BCC targeting complex, habitual MNCH practices.

Conclusions

This scoping review contributes to the evidence-base on the opportunities and limitations of using mobile phones for BCC delivery aiming to improve MNCH practices. The incorporation of mobile phone technology in BCC interventions should be guided by formative research to match both the content and delivery approach to the local context. We recommend five areas for further research, including both effectiveness and implementation studies on specific delivery approaches.

Improved caring practices is one important pathway towards progress in many aspects of maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Behavior change communication (BCC) has become an integral component of many MNCH interventions, but there are multiple known challenges to its implementation [1], particularly when addressing complex, habitual practices that are influenced by a variety of contextual factors [2].

The proliferation of mobile phones in LMIC suggests great potential to dramatically expand information access and enhance engagement with health messaging using mobile phone technology for health (mHealth) [3,4]. The current state of knowledge is fragmented and challenging to synthesize because there are numerous deployments of new mHealth initiatives and the timeliness and quality of reporting and assessment varies [5]. There is a need to strengthen the research agenda for evaluating such initiatives, and specifically to categorize BCC delivery approaches to support improved MNCH practices in LMIC. To meet this practical and scientific need, we present key findings of a broad scoping review that aimed to categorize BCC delivery approaches, and to describe the current state of evidence for the major approaches identified.

Globally, there are an estimated 5.7 billion unique individual mobile phone subscribers, with significant continued growth in LMIC [6]. There is optimism that leveraging mobile phone technology will assist in overcoming barriers to health system functioning and service delivery in LMIC, and many projects are integrating mHealth components [4,7,8]. Within the broader field of digital health, the term “mHealth” is used to refer collectively to the use of mobile technology for health-related functions, including data collection and management, service delivery, health communication and diagnostics [5,9]. Mobile phones are the primary mHealth technology and the most relevant to BCC interventions.

To our knowledge, two systematic reviews of mHealth for BCC in LMIC have been published. In 2012, Gurman et al. assessed sixteen studies of varying designs for their adherence to best practice guidelines for mHealth intervention designs [10]. Most showed evidence of appropriate formative work but tailoring of messages was limited, and few studies included long-term follow up or evaluation. More recently, Higgs et al. identified fifteen studies, primarily randomized controlled trials (RCTs), reporting causal attribution of mHealth interventions to behavioral outcomes relevant to child survival [11]. All selected studies used text messaging as the BCC intervention and addressed episodic rather than complex, habitual health behaviors. No conclusions regarding effectiveness could be drawn from either of these reviews. The authors of both reviews called for more attention to building the mHealth evidence base and highlighted specific limitations of the existing data in the field as the small number of available studies and the heterogeneity of study contexts, intervention strategies and target health outcomes. Higgs et al. also highlighted the need for implementation research to identify mechanisms of change and contextual factors influencing the success of mHealth interventions [11]. The mHealth evidence base has grown substantially since these two reviews were published, enabling some of the identified limitations to be addressed through an updated review.

Despite this growth, heterogeneity of mHealth study designs and contexts continue to hinder the determination of effects on MNCH outcomes. A systematic review of mHealth interventions targeted to pregnant women reported improvements in antenatal and neonatal service utilization, but evidence of effects on maternal and neonatal outcomes was limited, preventing meta-analysis [12]. A comprehensive systematic review of the effectiveness of mHealth interventions for MNCH outcomes in LMIC identified only fifteen relevant studies, ten of which were BCC interventions [13]. Meta-analysis was conducted for three studies which aimed to improve exclusive breastfeeding practices [14-16]. There were positive effects of the mHealth interventions on early initiation of breastfeeding (odds ratio OR = 2.01; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.27-2.75) and exclusive breastfeeding at three or four months (OR = 1.88; 95% CI = 1.26-2.50) and at six months (OR = 2.57; 95% CI = 1.46-3.68) [13]. The evidence review for the recently published Digital Health Guidelines found moderate evidence that targeted client communication improves attendance at four or more antenatal care (ANC) visits, antenatal use of iron-folic acid supplements, skilled birth attendance and infant vaccination rates, but concluded that effects on other MNCH outcomes are uncertain due to limited or poor quality evidence [5].

Notwithstanding the limited evidence base, multiple projects utilizing mHealth for MNCH are being designed and implemented within the programming sphere. These initiatives provide a rich basis for implementation learning that is not captured in systematic reviews of the peer reviewed scientific articles focused on determining effectiveness. In addition, mHealth interventions vary considerably in their approaches. There is a need to examine the characteristics, strengths and limitations of specific mHealth delivery approaches, as an aggregate effect size may be less useful for identifying specific strategies that could be implemented to address particular MNCH practices. The aims of this research were therefore: i) to classify, based on current evidence from recent and ongoing projects and programs, the specific approaches through which mobile phones can be used to deliver BCC related to MNCH; and ii) to describe the current state of evidence related to both effectiveness and implementation for each delivery approach. Within the broad field of MNCH this work focuses on BCC interventions intended to improve home-based care practices and uptake of preventive health services for mothers and young children during pregnancy, infancy and the first five years of childhood. It complements a separate forthcoming analysis that adopts a particular focus on infant and young child feeding.

METHODS

We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage methodology for scoping reviews in the health sciences [17]. Data were collected through searches of both the published and grey literature, and consultation with researchers and implementers of mHealth projects targeting improved MNCH practices. Ethics approval was not required.

Three major online databases (PubMed, MedLine and Scopus) were searched using the key term “mobile phone” with the following search terms: “counseling”, “behavior change”, “nutrition”, “infant feeding”, and “breastfeeding”. The full PubMed search is provided in Appendix S1 in Online Supplementary Document, and formed the basis of the MedLine and Scopus searches. These terms were chosen to achieve both a broad review of the relevant BCC literature and to address our specific interest in infant and young child feeding. Inclusion of the terms “maternal”, “neonatal”, “infant”, and “child” with the core search terms was tested in PubMed but did not produce any additional results, so these terms were not incorporated into the full search strategy. The search was initially conducted in October 2015 and subsequently updated to include papers published up to December 31, 2018. Searches were filtered for English language papers only, and the Scopus search was limited to journals in the medical and social science fields. All records were exported to EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, Toronto ON, Canada) citation management software and duplicates were removed.

To identify any additional BCC interventions within the target definition that may not have been reported in the peer-reviewed, published and indexed scientific literature we searched for relevant grey literature in online repositories of mHealth program information using the terms “behavior change”, “nutrition” and “counseling” separately and in combination. We also searched the websites of many organizations known to be engaged in mHealth, either using the website’s internal search function or by screening the documents available for download under relevant website tabs. These online repositories and websites are listed in Tables S1 and S2 in Online Supplementary Document. Additional published studies and grey literature reports were identified through review of the reference lists of all selected documents, PubMed suggestions for similar articles, Google searches, and through direct consultation with implementers and researchers in the mHealth field. We also searched two registries of clinical trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry, http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) using the terms “mHealth”, “mobile phone” and “mobile health” combined with “nutrition”, “behavior change” and “counseling” to identify current research studies relevant to the scoping review. New papers were added to the grey literature search until February 8, 2019.

We screened all records from these literature searches using pre-determined inclusion criteria. Published articles were selected if they reported on feasibility or intervention studies in LMIC related to the use of mobile phone technology for BCC to improve home-based care practices and uptake of preventive health services for mothers and young children during pregnancy, infancy and the first five years of childhood. There were no restrictions by publication date or study methodology. We excluded studies reporting on: monitoring and evaluation aids; electronic health records; clinical interventions; MNCH interventions occurring outside our target period of pregnancy to age five; and interventions in high-income countries. Abstracts were reviewed for records that could not be excluded by title alone; where uncertainty remained, the full text was reviewed.

We reviewed all potentially relevant documents from the grey literature by title, abstract or executive summary (if available), or full text. We included documents that reported on the feasibility, evaluation or implementation lessons from interventions conducted in LMIC using mobile phone technology for BCC to improve home-based care practices and uptake of preventive health services for mothers and young children during pregnancy, infancy and the first five years of childhood. Media articles and blog posts were excluded, as were project briefs without any evaluation data or reflection on lessons learned. Only one grey literature document was included for each discrete mHealth project unless additional documents contributed unique findings.

We categorized the selected studies and reports according to their primary intervention delivery approaches. Data were extracted and compiled using charting tables developed to record key details regarding study methodology (design, sample size, location), intervention, and findings or lessons learned. We performed a descriptive analysis of the evidence related to both effectiveness and implementation for each delivery approach.

RESULTS

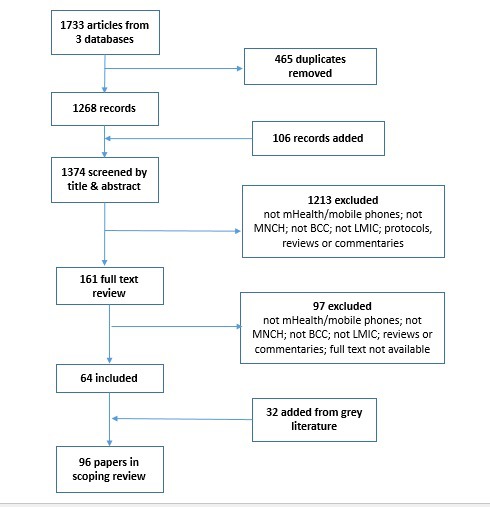

The search of published literature yielded 1374 unique articles after removal of duplicates. After title and abstract review, 161 remained for full text review, of which 64 met the inclusion criteria. A further 32 were added from the grey literature, including unpublished research and programmatic case studies, for a total of 96 papers included in the scoping review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature search flowchart.

We classified the papers into four BCC delivery approaches: direct messaging, voice counseling, job aid applications and interactive media (Table 1). Several projects utilized both direct messaging and voice counseling, and are presented under this combined category. Table 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 provide an overview of the studies and reports included under each delivery approach.

Table 1.

Literature search results by behaviour change communication delivery channel

| Type | Source | Direct messaging | Voice counseling | Messaging + voice | Job aid apps | Interactive media |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intervention studies |

Published |

16 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

1 |

| Grey |

4 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

||

|

Implementation Studies |

Published |

9 |

2 |

3 |

||

| Grey |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Feasibility Studies |

Published |

6 |

2 |

3 |

||

| Grey |

||||||

|

Formative/Qualitative Studies |

Published |

6 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

| Grey |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Case studies & other programmatic reports |

Published |

|||||

| Grey |

8 |

1 |

9 |

|||

|

TOTAL documents |

50 | 4 | 14 | 27 | 1 | |

Table 2.

Direct messaging studies and programmatic reports

| Study |

Design |

Messaging intervention |

Target outcomes |

Key results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intervention studies – published literature: | ||||||||

| Jiang et al, 2014 [14] |

Quasi-experimental cluster randomized trial in Shanghai, China; N = 582 mothers in first trimester recruited from 4 community health clinics |

Weekly SMS on infant feeding from 3rd trimester to 12 months postpartum; participants could text questions to a health professional |

Increased exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) duration |

Median duration EBF: 11.41 weeks (I.) vs 8.87 (C.). EBF at 6 months: 15.1% vs 6.3% |

||||

| Unger et al, 2018 [18] |

Randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Nairobi, Kenya; N = 298 pregnant mothers with own mobile phones. |

Weekly SMS from pregnancy to 12 weeks postpartum. Group 2 also had bi-directional SMS communication with a nurse. |

Increase facility-based delivery (FBD), EBF duration and postpartum contraception use. |

No significant effects for FBD & contraceptive use. EBF probability significantly higher vs Control in both I-groups at 10 weeks (OR = 0.93; 95% CI = 0.86-0.97 and OR = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.89-0.98 vs OR = 0.79; 95% CI = 0.69-0.86; P < 0.005) and 16 weeks (OR = 0.82; 95% CI = 0.72-0.89 and OR = 0.93; 95% CI = 0.85-0.97 vs OR = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.52-0.71; P < 0.005) and in I-2 at 24 weeks (OR = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.51-0.72 vs OR = 0.41; 95% CI = 0.31-0.51; P = 0.005). |

||||

| Flax et al, 2014 [16] |

Cluster RCT in Bauchi state Nigeria; N = 390 mothers pregnant at baseline & interviewed when infants ≥6 months |

Intervention × 10 months: monthly large group breastfeeding education; weekly SMS to small group who presented to monthly large group |

Increase timely breastfeeding initiation and EBF duration |

Timely initiation: OR = 2.6 (95% CI = 1.6-4.1). EBF to 6 months: OR = 2.4 (95% CI = 1.4-4.0) |

||||

| Lund et al, 2012 [19] |

Wired Mothers project; cluster RCT via 24 health facilities in Zanzibar, Tanzania; N = 2550 (Intervention: n = 1311) |

Intervention group received 1-way SMS tips & reminders 2×/months to 36weeks gestation then 2×/week to 6 weeks postpartum; also received airtime voucher & health worker phone number. |

Increase in skilled birth attendance |

Skilled birth attendance: 60% vs 47% overall but non-significant for rural women. Urban OR = 5.73 (95% CI = 1.51-21.81). |

||||

| Lund et al, 2014 [20] |

As above |

As above |

Primary: Increase in mothers attending >4 antenatal care (ANC) visits. Secondary: improve timing and quality of ANC service delivery |

4+ANC: 44% I vs 31% C. OR = 2.39 (95% CI = 1.03-5.55). Trend towards improved timing & quality of ANC services but not significant. |

||||

| Lund et al, 2014 [21] |

As above |

As above |

Reduced perinatal mortality |

Significant difference in perinatal mortality: 19/1000 (I) vs 36/1000 (C). OR = 0.50 (0.27-0.93). Non-significant reduction in stillbirths (OR = 0.65; 95% CI = 0.34-1.24) & deaths in first 42 d of life (OR = 0.79; 95% CI = 0.36-1.74) |

||||

| Fedha, 2014 [22] |

RCT in 4 ANCs in Kenya. N = 397 pregnant mothers |

Fortnightly SMS reminders of ANC visits and pregnancy health information |

Increase uptake of ANC services and FBD. Reduce neonatal mortality. |

<4 ANC visits: 3.6% (I) vs 9.7% (C) (P = 0.002). FBD: 88.0% (I) vs 72.8% (C) (P = 0.00). No significant difference in intrauterine deaths (1% vs 1.5%; P = 0.715) or neonatal deaths (1.0% vs 3.4%; P = 0.269). |

||||

| Omole et al, 2016 [23] |

Quasi-experimental pre/post study in 4 ANCs in Nigeria; N = 548 pregnant mothers with mobile phones |

Weekly SMS reminders of ANC visits and pregnancy health information; two-way messaging for questions. Control = general health messages |

Increase in mothers with 4 ANC visits and FBD |

Difference-in-differences for FBD compared with prior pregnancies showed significantly greater increase in Intervention group (29% vs 13%). |

||||

| Bangal et al, 2017 [24] |

RCT in Ahmednagar, India. N = 400 pregnant mothers with mobile phones. |

Phone call reminders for ANC visits. SMS messages with pregnancy health information. |

Increase in mothers with 4 ANC visits, FBD and post-natal checks |

>4 ANC: 57.5% (I) vs 23.5% (C) (P < 0.0001). FBD: 91.5% (I) vs 89% (C) (P-value not given). No postnatal visits: 5.9% (I) vs 29.3% (C) (P < 0.001). |

||||

| Odeny et al, 2014 [25] |

RCT in Nyanza region, Kenya; N = 388 HIV+ pregnant mothers enrolled in a prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV project, randomized to Intervention (n = 195) or Control (n = 193) |

Intervention: 8 prenatal and 6 postnatal SMS messages. Participants in both study arms had SMS access to a study nurse. |

Increase in postnatal care attendance and infant HIV testing by 8 weeks postpartum |

Results (I. vs C.): Postnatal care attendance: 19.6% vs 11.8% (RR = 1.66; 95% CI = 1.02-2.70). Infant HIV testing: 92.0% vs 85.1% (RR = 1.08; 95% CI = 1.00-1.16) |

||||

| Uddin et al, 2016 [26] |

Quasi-experimental pre/post evaluation using population level household surveys in Bangladesh; N = 4158 |

SMS reminders to mothers timed to vaccination schedule |

Increase vaccination coverage in hard-to-reach groups |

Difference-in-differences for full vaccination: +29.5% (rural; P < 0.001) & +27.1% (urban; P < 0.05). OR = for rural: 3.8 (95% CI = 1.5-9.2); OR = for urban: 3.0 (95% CI = 1.4-6.4) |

||||

| Haji et al, 2016 [27] |

Quasi-experimental evaluation in 3 districts of rural Kenya with low coverage of 3rd dose pentavalent vaccine; N = 1116 children receiving first dose pentavalent vaccine |

SMS vaccination appointment reminders compared with stickers or standard of care |

Increase full vaccination coverage |

SMS group significantly less likely to miss 3rd vaccine dose (OR = 0.2, CI = 0.04-0.8) |

||||

| Gibson et al, 2017 [28] |

Cluster RCT in rural Kenya; N = 2018 infants from 152 villages |

SMS reminders before pentavalent & measles vaccination dates. Parents in 2 groups also received incentives of either KES75 (US$0.88) or KES200 (US$2.35) for timely immunization. |

Increase full vaccination coverage (BCG, measles, 3 doses polio, 3 doses pentavalent) at 12 months |

Overall 86% fully immunized. No significant effects for SMS or SMS+KES75 groups. SMS+KES200 group were significantly more likely to achieve full immunization vs control (RR = 1.09; 95% CI = 1.02-1.16; P = 0.014) |

||||

| Zhou et al, 2016 [29] |

Cluster RCT in 351 villages in Shaanxi Province, China; N = 1818 infants age 6-12 mo. |

Free delivery of micronutrient powders plus daily SMS usage reminders compared with free delivery only and control |

Increase caregiver compliance with micronutrient powder regimen; reduce child anaemia. |

Higher compliance in SMS group (marginal effect: 0.10; 95% CI = 0.03-0.16). Greater decrease in anemia in SMS group relative to control group (marginal effect: -0.07; 95% CI = -0.12, -0.01), but not relative to delivery-only group (marginal effect = -0.03; 95% CI = -0.09-0.03). |

||||

| Alam et al, 2017 [30] |

Observational study comparing Aponjon subscribers from 5 districts of Bangladesh who did and did not receive prenatal messages; N = 476 |

Twice-weekly maternal and newborn health messages by SMS or IVR |

Increase in skilled birth attendance; early initiation of breastfeeding; delayed newborn bathing; and postnatal care visits. |

No significant differences between groups for any outcome. |

||||

| Coleman et al, 2017 [31] |

Retrospective study of HIV+ pregnant mothers, South Africa; N = 235 mothers receiving SMS intervention compared with non-users (N = 586) |

Twice-weekly maternal health SMS messages tailored to stage of pregnancy and first year postpartum |

Increase in ANC attendance and timely infant HIV testing; reduce low birth weight (<2500g). |

SMS group were significantly more likely to attend ≥4 ANC visits (RR = 1.41; 95% CI = 1.15-1.72) and less likely to have a low birth weight infant (RR = 0.14; 95% CI = 0.02-1.07). |

||||

|

Intervention studies – grey literature: | ||||||||

| Chowdhury, 2015 [32] |

Retrospective observational study of MAMA’s Aponjon project in Bangladesh; N = 1473 (600 users +873 non-users matched by propensity score) |

Subscriber-based MNCH messaging service using SMS or IVR, tailored to stage of pregnancy and infancy |

Increase care seeking for MNCH |

8/19 maternal care practices and 1/12 neonatal care practices significantly associated with Aponjon use (P < 0.05). No effect on infant feeding indicators. |

||||

| Coleman & Xiong, 2017 [33] |

Retrospective case-control study using clinical records, comparing MomConnect subscribers matched with non-subscribers in Johannesburg, South Africa. N = 98 per group for ANC data; n = 33 per group for infant immunization data. |

Subscriber-based messaging service delivering twice-weekly pregnancy and post-partum health messages to personal phones; help desk for registered users to ask questions and give feedback on health services |

Primary: ≥4 ANC visits; Secondary: total ANC visits; infant birth weight; infant immunization coverage |

Descriptive results (I. vs C.) as sample size not achieved. ≥4 ANC visits: 68.4% vs 70.4%. Full immunization at 1 y: 97% vs 93.9%. 80.5% MomConnect users were satisfied with the service. |

||||

| MatCH, 2016 [34] |

Mixed methods evaluation of MomConnect (2011-2014) in KwaZuluNatal, South Africa. Quantitative: analysis of project monitoring data. Qualitative: interviews with subscribers (n = 60) and health workers (n = 37) |

Subscriber-based messaging service delivering twice-weekly pregnancy and post-partum health messages to personal phones, linked to electronic medical records |

Improved maternal and infant health and uptake of Prevention of Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission services |

Enrollment targets were achieved and subscribers were highly satisfied with the SMS service. Further training for health workers and improved connectivity at health facilities were recommended to fully integrate the SMS service with electronic medical records. |

||||

| Healthbridge Foundation of Canada, 2016 [35] |

Quasi-experimental mixed methods study of 3M project (Men using Mobile phones to improve Maternal health) in Jharkhand state, India; N = 207 couples with pregnant mothers, divided into Intervention (n = 104) and Control groups (n = 103). Qualitative data collected through stakeholder interviews and six focus group discussions with participants. |

Husbands in intervention group received weekly IVR messages with maternal health information and reminders. Mothers in both groups were counseled by frontline health workers using a job aid app with multimedia messages. |

Improved uptake of maternal health services (4+ ANC visits; consumption of 100 iron-folic acid tablets; FBD) |

On average, husbands in Intervention group listened to 9 of 29 messages, with 31% listening to none. Results (I. vs C.):4+ ANC visits: 68.3% vs 58.3%; P > 0.05. 100 Iron-folic acid tablets: 33.7% vs 27.2%; P > 0.05. FBD: 93.3% vs 62.1%; P < 0.001. |

||||

|

Implementation studies – published literature: | ||||||||

| Crawford et al, 2014 [36] |

Analysis of electronic monitoring records and quarterly phone-based user surveys in Chipatala Cha Pa Foni project, Malawi |

Subscriber-based MNCH messaging service delivered through SMS or IVR sent to personal phone, or IVR stored and retrieved from a community phone |

Increase knowledge and coverage of home- and facility-based MNCH care |

Message delivery success was greatest for SMS subscribers (30% of users) who were also more likely to report intended or actual behavior change (P = 0.01) |

||||

| Jiang et al, 2018 [37] |

Description of implementation process and summary of process evaluation findings from monitoring records and qualitative interviews with participants at midterm (n = 22) and endline (n = 15). |

Weekly SMS on infant feeding from 3rd trimester to 12 months postpartum; participants could text questions to a health professional |

Increased EBF duration |

3-phase implementation process: formative study; baseline questionnaire; message bank development. Process evaluation found high acceptability but preference for more in-depth and personalized content. |

||||

| Flax et al, 2016 [38] |

Evaluation of feasibility and acceptability of using group cell phones in cluster RCT with micro-credit clients in Nigeria. Analysis of data from exit interviews (n = 195) and in-depth interviews (n = 17) with participants, and focus group discussions (n = 16) with non-participants |

Intervention x10 months: monthly large group breastfeeding education; weekly SMS to small groups who presented to monthly large group |

Increase timely breastfeeding initiation and EBF duration |

Participants reported that the group cell phones worked well (64%) and 44% met at least weekly to share BCC messages. Participants in groups meeting at least weekly were more likely to practice EBF to six months than those in groups that never met (OR = 5.6; 95% CI = 1.6-19.7). |

||||

| Entsieh et al, 2015 [39] |

Qualitative study; in-depth interviews (n=19) and focus group discussions (n=25 participants) with mothers who used Mobile Midwife messaging service in Ghana |

Subscriber-based messaging service for maternal health |

Improve maternal health and care-seeking |

Participants described a gradual process of gaining trust in the Mobile Midwife messages, but needing to balance the new content with traditional practices. Engagement with the messages increased awareness of the need for skilled care and birth preparedness. |

||||

| LeFevre et al, 2018 [40] |

Evaluation of MomConnect reach and exposure from August 2014-April 2017 using system-generated data, South Africa |

Subscriber-based messaging service delivering twice-weekly pregnancy and post-partum health messages to personal phones; help desk for registered users to ask questions and give feedback on health services |

Improve maternal health and quality of health care services. |

Half of all women attending ANC-1 registered with MomConnect (n = 1 159 431) and subscribers received over 80% of messages sent. In 2016, 26% of attempted registrations failed, indicating a need for on-going system monitoring and improvement. |

||||

| Skinner et al, 2018 [41] |

Qualitative study; in-depth interviews (n = 32) and 7 focus groups with MomConnect users, South Africa |

Subscriber-based messaging service delivering twice-weekly pregnancy and post-partum health messages to personal phones; help desk for registered users to ask questions and give feedback on health services |

Improve maternal health and quality of health care services. |

Participants were satisfied with both the content and delivery system, with many saving the messages for future reference. Awareness of the help desk service was low. |

||||

| Xiong et al, 2018 [42] |

Evaluation of system data collected from August 14, 2014 to March 31, 2017 for MomConnect helpdesk, South Africa |

Subscriber-based messaging service delivering twice-weekly pregnancy and post-partum health messages to personal phones; help desk for registered users to ask questions and give feedback on health services |

Improve maternal health and quality of health care services. |

Approximately 8% of MomConnect subscribers used the helpdesk (n = 95.288), sending over 250 messages per day; 78.5% were health questions. |

||||

| Huggins & Valverde, 2018 [43] |

Systems theory analysis of mNutrition using Malawi as a case study |

SMS service delivering MNCH, household nutrition and agriculture content to smallholder farmers |

Improve maternal and child nutrition |

mNutrition was implemented within a complex system. Limited integration between sub-systems promoted more rapid implementation but likely compromised effectiveness and sustainability of messaging. |

||||

|

Implementation study – grey literature: | ||||||||

| Chakraborty et al, 2019 [44] |

Descriptive summary of monitoring findings (user surveys and focus group discussions) in Bihar, India |

JEEViKA Mobile Vaani: interactive IVR platform allowing users to listen to pre-recorded content and record their own messages (curated). Core content focused on maternal diet diversity, complementary feeding, diarrhea management and social entitlements. |

Increase intra-household dialogue on maternal and child nutrition, leading to improved practices |

Extensive training facilitated user adoption of the JeeViKA platform. Implementing through self-help groups increased women’s participation but many were older women who engaged less with core content. Including non-core topics of interest to users increased overall engagement with content. |

||||

|

Feasibility studies – published literature: | ||||||||

| Datta et al, 2014 [45] |

Pre/post knowledge test and qualitative assessment in Tamil Nadu, India; N = 120 |

Participants received 10 MNCH messages over 10 d via SMS |

Assess feasibility of SMS for improving MNCH knowledge |

Knowledge scores improved and qualitative data indicated acceptability of SMS |

||||

| Hazra et al, 2018 [46] |

Quasi-experimental study in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. Quantitative survey (N = 881 husbands & 956 women). Qualitative in-depth interviews with 10 couples and 2 focus group discussions with frontline health workers |

Husbands of pregnant women received IVR messages on 5 MNCH topics twice-weekly over 4 months |

Assess feasibility of IVR to husbands for improving household MNCH discussions and practices |

34% participants reported receiving messages; 16% discussed messages at home. Main barrier: calls came while at work. Mothers with husbands who discussed messages were more likely to report ANC visit in 3rd trimester (OR = 1.72, P < 0.05), postnatal visit within 7 d (OR = 3.02, P < 0.05) & delayed newborn bathing (OR = 1.93, P < 0.05). |

||||

| Huang & Li, 2017 [47] |

Survey of 129 randomly selected mothers who had registered for IVR service through community midwives in Cambodia. |

Seven messages on neonatal care sent to mother’s phone from postnatal day 3-28 |

Assess acceptability of IVR to improve newborn care |

Intervention was well accepted, with 60% indicating willingness to pay for the service. 43% reported taking baby to the health centre because of the IVR messages. |

||||

| McBride et al, 2018 [48] |

Qualitative endline evaluation of mMom users, Vietnam. 2 Focus Groups and 8 interviews with frontline health workers; 4 focus group discussions and 30 interviews with participants (n = 60) |

2-3 times weekly SMS during pregnancy & infancy. 15% interactive messages. SMS service linked to Health Management Information System to enhance contact and follow up by health providers. |

Increase access to MNCH services by ethnic minority women in remote areas |

High satisfaction with SMS and most expressed willingness to pay for the service. Participants reported increased knowledge and care seeking and stronger relationships with frontline health workers. |

||||

| Prieto et al, 2016 [49] |

Mixed methods study: quantitative survey (all) and content analysis of text messages (groups 2 & 3). N = 78 Spanish speaking pregnant women or mothers of young infants in Guatemala. |

All participants received a free basic mobile phone with prepaid credit. Group 1: 2 × weekly breastfeeding SMS. Group 2: group text messaging to discuss MNCH topics. Group 3: same as group 2 + breastfeeding messages + health professional facilitated group. Group 4: control |

Compare text messaging approaches for MNCH with focus on breastfeeding |

Knowledge of EBF at endline was greater in Groups 1 (60%) & 3 (50%) than Groups 2 (8%) & 4 (25%). Content analysis (groups 2 & 3): 62% messages related to social support; 35% health info; 3% other |

||||

| Domek et al, 2016 [50] |

Pilot RCT at 2 public health clinics in Guatemala City. N = 321 infants age 8-14 weeks presenting for 1st immunization dose. |

3 SMS reminders one week before 2nd and 3rd immunization dose. |

Assess feasibility and acceptability of SMS to improve adherence to full immunization. |

No significant differences between groups (i. vs C.) for dose 2 (95.0% vs 90.1%; P = 0.12) or dose 3 (84.4% vs 80.7%; P = 0.69). Over 90% of participants wanted future SMS reminders with the Intervention group more willing to pay for the service (67.5% vs 49.6%; P = 0.01). |

||||

| Wakadha et al, 2013 [51] |

Pilot study in western Kenya; N = 72 mothers of infants age 0-3 weeks |

SMS reminders sent 3 d before and on the day of Pentavalent vaccine doses 1 and 2. Mothers of infants vaccinated within 4 weeks of the scheduled date received KES150 (US$2) as either airtime credit (1/3) or mobile money transfer (2/3). |

Assess feasibility and acceptability of SMS plus conditional cash transfers to improve timely vaccination. |

63 children had known vaccination status at endline, of whom 90% received dose 1 and 85% received dose 2 within 4 weeks of the scheduled date. All mothers preferred mobile money transfer to airtime credit. |

||||

|

Formative research – published literature: | ||||||||

| Hmone et al, 2016 [52] |

Qualitative formative study with pregnant mothers and family members (n = 20 in-depth interviews) and service providers (n = 7 interviews; n = 15 focus group participants) in Yangon, Myanmar |

SMS to increase EBF |

Identify barriers and facilitators of EBF and of SMS communication in order to guide the design and messaging content for an RCT |

EBF barriers include grandmothers’ recommendations for early supplementation, perception of insufficient breastmilk, and mothers’ return to work. Contextualized messages sent in the evening were recommended for the intervention. |

||||

| Weerasinghe et al, 2016 [553] |

Qualitative study in 2 tea estates, Sri Lanka. Focus group discussions with mothers (n = 109), fathers (n = 30) and older women (n = 32). Interviews with health and childcare providers (n = 15). |

SMS or IVR for infant and young child feeding counseling |

Explore issues related to infant and young child feeding, use of mobile phones and sources of nutritional information. |

Most household have mobile phones, primarily used by men for voice calls. Infant and young child feeding counseling is provided in-person at regular growth monitoring sessions. Mothers and health workers preferred in-person counseling but were open to IVR as a supplementary intervention. |

||||

| Kazi et al, 2017 [54] |

Survey conducted in 8 health facilities in Northern Kenya; N = 284 attendees at routine ANC and immunization clinics. |

SMS to promote ANC and immunization |

Explore potential for SMS delivery platform |

88% had access to mobile phones; 92% of those were interested in receiving a weekly SMS health message. |

||||

| Yamin et al, 2018 [55] |

Cross-sectional survey in Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan; N = 240 women |

Direct Messaging for MNCH, including ANC and immunization reminders. |

Explore perceptions related to use of mobile phones for MNCH communication. |

91.7% routinely used mobile phones. 87.1% were willing to receive health messages. IVR was preferred to SMS. |

||||

| Calderon et al, 2015 [56] |

Cross-sectional survey in Arequipa, Peru. N = 220 mothers with at least one child under 5 y old |

2-way SMS for child care during illness |

Explore feasibility and acceptability of 2-way SMS platform |

95% reported mobile phone access. 86% were interested in using SMS to receive child health messages or seek care but only 27% wanted to receive appointment reminders. |

||||

| Brinkel et al, 2017 [57] |

Qualitative study in four districts of the Greater Accra Region, Ghana; 4 focus group discussions with caregivers of at least one child under 10 y old N = 40 |

IVR for health seeking |

Explore feasibility and acceptability of IVR platform |

Participants were open to IVR but had no prior experience with it. Social, infrastructure and technology literacy barriers were identified. A toll-free number and training was recommended. |

||||

|

Case studies – grey literature: | ||||||||

| MAMA Bangladesh [58] |

Narrative report of intervention design process based on formative research findings |

Subscriber-based MNCH messaging service using SMS or IVR; hotline for subscribers to contact a female doctor |

Key design elements identified through formative research: options for users with low technology literacy; inclusion of family members; use female doctor voice; timing of message delivery; record messages in local dialects; adapt message content & frequency for rural vs urban clients |

|||||

| MOTECH ‘Mobile Midwife’ [59] |

Narrative report of intervention design process and lessons learned |

Subscriber-based IVR service for maternal health in rural Ghana |

Message design & delivery guided by formative research. Collaboration with respected partners increased trust, and mHealth initiative integrated with efforts to improve ANC services. |

|||||

| Mobile Information for Maternal Health [60] |

Narrative report of project design and monitoring results |

Subscriber-based MNCH messaging service using IVR or SMS for pregnant mothers in Ghana, with interactive messages to assess retention of content |

5400 subscribers; 73% report the messages are useful and the majority listen to >80% of the messages. Monitoring data showed IVR messages of 90 s retained 70% of users, so content was redeveloped to fit this optimal timing. |

|||||

| ‘Healthy pregnancy, healthy Baby’ [61] |

Narrative report of intervention design with lessons learned |

Subscriber-based text messaging service in Tanzania with tracks for pregnant mothers, their supporters and general information-seekers |

Lessons learned on content development: messages must be localized & pre-tested; best to craft in local language, not translate; include fun messages with formal health content. Implementation challenges include low female phone ownership & literacy; poor connectivity; responding to questions from subscribers. |

|||||

| ‘Healthy Pregnancy Healthy Baby’ [62] |

Narrative report of lessons learned from GSMA engagement with the ‘Healthy Pregnancy Healthy Baby’ program from 2014-2017, based on user feedback and surveys |

Subscriber-based SMS service in Tanzania offering content on MNCH, prevention of mother-child HIV transmission and family planning, embedded in Ministry of Health mHealth platform |

Key lessons learned: self-registration is challenging for many users but frontline workers assisting registration need regular refresher training; promoting the program via radio and TV ads doubled registrations; in-kind support from 4 national mobile network operators allows large reach at no cost to users; content must be both accurate and contextually appealing; appointment reminders are highly valued. |

|||||

| People In Need Cambodia [63] |

Narrative report of intervention design process and pilot study |

Subscriber-based IVR service in Cambodia delivering seven messages on neonatal care to mother’s phone from postnatal day 3-28 |

Message design and delivery guided by formative research. Contextual adaptations included use of voices representing locally authoritative figures; content geared to build community support for improved newborn care; midwives registered mothers after delivery; subscribers also received a hanging mobile toy with the messages. Key partnerships supported both content development and technology systems. |

|||||

| Kilkari [64] |

Narrative report of lessons learned and best practices for implementation at scale |

Subscriber-based weekly IVR service for MNCH in six states of India |

2 million subscribers in first 12 months; 42% listen to ≥75% of messages. Content is narrated by a female doctor character and targets both fathers and mothers. Call costs are covered by Government of India. Ongoing investment in skilled technology support is needed to maintain large-scale implementation. |

|||||

| mNutrition [65] | Narrative report of intervention design and monitoring results |

SMS service delivering MNCH and nutrition content in 8 countries: Malawi, Ghana, Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria, Zambia, Uganda, Mozambique |

Multi-partner initiative delivering localized content through mobile network providers. 1.59 million users across 8 countries by December 2017. 69% of users reported correct nutrition knowledge and practices vs 57% and 56% of non-users. 42% of users report sharing content with others. Repeated messages are appreciated and reinforce key content. |

|||||

EBF – exclusive breastfeeding, FBD – facility-based delivery, RCT – randomized controlled trial, ANC – antenatal care, IVR – interactive voice response, MNCH – maternal newborn and child health

Table 3.

Voice counseling studies

| Study | Design | Voice counseling intervention | Target outcomes | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intervention studies – published literature: | ||||

| Maslowsky et al, 2016 [66] |

Prospective evaluation in Quito, Ecuador; N = 178 Spanish speaking mothers recruited as inpatients at delivery and randomized to intervention (n = 102) or control (n = 76). |

Structured postnatal education via mobile phone within 48 h of delivery; phone access to nurse during business hours for newborn’s first 30 d |

Improve postnatal care and maternal and infant health |

EBF at 3 mo: 86.7% (I.) vs 66.7% (C.); P = 0.005. Neonatal well baby check attendance: 72% (I.) vs 53.3% (C.); P = 0.022. No significant differences for 2-months well baby visit attendance or contraception use. |

|

Formative and qualitative studies – published literature: | ||||

| Huq et al, 2014 [67] |

Qualitative pre/post study in rural Bangladesh. Pre: interviews with Community Skilled Birth Attendants (CSBA) (n = 12) & mothers (n = 14). Post: in-depth interviews (n = 6 CSBA); semi-structured interviews (n = 27 CSBA). 1 FGD with 10 mothers. |

‘mobile pathways’ using toll free numbers: mother/family calls CSBA who provides advice and/or consults with experts |

Increase access to prompt, quality care for complications during pregnancy & delivery |

Participants perceived improvement in timely access to care, access to specialist care and care seeking. |

| Khan et al, 2018 [68] |

Formative study in 2 sub-districts, Bangladesh. In-depth interviews with mothers (n = 24) and health workers (n = 13); focus group discussions with fathers (n = 4) and grandmothers (n = 4). |

Mobile phones for infant and young child feeding counseling |

Increase quality and coverage of counseling by frontline health workers (FLWs) |

Voice calls were preferred by both mothers and FLWs, but issues of phone access (mothers), cost (FLWs) and building trust with household decision-makers were identified. |

|

Intervention studies – grey literature: | ||||

| Sellen et al, 2013 [15] | Randomized control trial in Kenya; n = 752 HIV-mothers randomized to two intervention groups or control (standard of care) | Group 1: Proactive bi-weekly call from same counselor to 3 months post-partum; unlimited access to text & phone support. Group 2: monthly peer support group facilitated by infant and young child feeding counselor | Increased prevalence of EBF at 3 months postpartum | EBF at 7 d: 94% all groups. EBF at 3 months: 90.9% (group 1), 82.8% (group 2), 78.2% (control) [P = 0.0017 between group 1 and other 2 groups, non-significant between group 2 and control] |

EBF – exclusive breastfeeding, CSBA – Community Skilled Birth Attendant, FLWs – frontline health workers

Table 4.

Studies of direct messaging + voice counseling

| Study | Design |

Intervention | Target outcomes | Key results |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intervention studies – published literature: | ||||||

| Fotso, Robinson et al, 2015 [69] |

Two-arm, pre/post quasi-experimental effectiveness evaluation using cross-sectional household surveys; n = 2810 (baseline); n = 3643 (endline) |

Chipatala Cha Pa Foni project, Balaka district, Malawi. Intervention: subscriber-based ‘tips and reminders’ weekly messaging service and case management hotline for health advice and referrals; community-shared phones hosted by volunteers to increase access |

Increased knowledge and use of home- and facility-based MNCH care |

Intention-to-treat analysis: negative effects on child care practices; no effect on knowledge or maternal care. Treatment-on-treated effect analysis: positive effects on home-based (P < 0.01) and facility-based (P < 0.05) maternal care, and home-based child care (P < 0.01). |

||

| Fotso, Bellhouse et al, 2015 [70] |

As above |

As above |

As above |

Home-based care for child health improved through increased bed net usage (P < 0.01); facility-based care seeking for child fever decreased (P < 0.01) |

||

| Patel et al, 2018 [71] |

Two-arm cluster randomized trial of mothers (n = 1036) recruited through baby-friendly hospital antenatal care facilities; 2 clusters per arm |

Daily SMS, weekly call from certified lactation counselor, and phone number to call counselor from 3rd trimester to 6 months postpartum. |

Improve exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) |

EBF (I. vs C.): Birth: 74.3 vs 73.7%; Follow up: (P < 0.001) 6 weeks: 97% vs 80.9%; 10 weeks: 97.6% vs 78.1%; 14 weeks: 96.2% vs 70.7%; 6 months: 97.3% vs 48.5% |

||

|

Intervention studies – grey literature: | ||||||

| Watkins et al, 2013 [72] |

Mixed methods evaluation. Quantitative: Two-arm, pre/post quasi-experimental design; cross-sectional population-based household surveys; n=2810 (baseline); n=3643 (endline). Qualitative: Key Informant Interviews (n=47) with health staff, village leaders & project staff; Focus Group Discussions (n=12 with 10 participants each) with users, non-users and mothers who had not heard of the project; in-depth interviews (n=16) with 1 participant per focus group and her husband; hearsay ethnographic journals (n=46) |

Chipatala Cha Pa Foni project, Balaka district, Malawi Intervention: subscriber-based ‘tips and reminders’ weekly messaging service + case management hotline providing protocol-based advice and referrals; community-shared phones hosted by volunteers to increase access |

Increased knowledge and use of home- and facility-based MNCH care |

Intervention reached 19% of eligible mothers; 61% used the community phone to access services. Endline survey: no significant differences in knowledge or home-based care practices; negative effect on uptake of facility-based services for child health. Qualitative: high user satisfaction and perceived improvements in quality of facility-based care. Non-users faced technical and socio-cultural barriers. |

||

| Health Alliance International, Liga Inan Technical Briefs 2 & 3 [73,74] |

Pre/post intervention study comparing intervention and control communities in Timor-Leste; N=603 mothers of children under 2 years at endline (breakdown between Intervention and Control areas not provided) |

Registered pregnant mothers receive twice weekly SMS education and reminder messages and can request a call from their midwife. Midwives call all clients 3 weeks before due date. |

Improve uptake of maternal and neonatal health services, particularly antenatal care (ANC), facility-based delivery, skilled birth attendance, postpartum care for mother and postnatal care for infant within 2 days |

Changes from baseline to endline (I. vs. C.; P-values not given): 4+ ANC visits: 76% to 85% vs. 67% to 81%; Facility-based delivery: 32% to 49% vs. 29% to 28%; Skilled birth attendance:48% to 62% vs. 38% to 36%; Postpartum care within 2 days: 26% to 51% vs. 38% to 25%; Postnatal care within 2 days: 20% to 39% vs. 32% to 22% |

||

|

Implementation studies – published literature: | ||||||

| Larsen-Cooper et al, 2015 [75] |

Mixed-methods study of use of community shared phones; data from monthly usage records and larger program evaluation qualitative data |

Chipatala Cha Pa Foni (CCPF) project, Balaka district, Malawi. Intervention: subscriber-based ‘tips and reminders’ weekly messaging service + case management hotline providing protocol-based advice and referrals; community-shared phones hosted by volunteers to increase access. |

Increased knowledge and use of home- and facility-based MNCH care |

9328 users called the hotline; 5884 subscribed to messaging service. 68% accessed services through non-owned phone, but usage decreased over time. |

||

| Larsen-Cooper et al, 2016 [76] |

Cost-outcome analysis of CCPF project, Malawi, using a base cost model to estimate costs per user and per contact. Costs were mapped to MNCH indicators which showed improvements in the pre/post evaluation in order to estimate costs of health improvements, with sensitivity analysis to explore effects of higher intervention usage. |

Chipatala Cha Pa Foni (CCPF) project, Balaka district, Malawi. Intervention: subscriber-based ‘tips and reminders’ weekly messaging service + case management hotline providing protocol-based advice and referrals; community-shared phones hosted by volunteers to increase access. |

Increased knowledge and use of home- and facility-based MNCH care |

9798 unique users accessed CCPF, at a cost of US$29.33 per user and US$4.33 per successful contact (message sent or received). Costs ranged from US$67 to US$355 for each pregnant user reporting improvements in MNCH knowledge, and from US$128 to US$256 for each user reporting changes in MNCH practices. Sensitivity analysis showed a 48% reduction in cost per user if the system operated at full capacity. |

||

|

Implementation study – grey literature: | ||||||

| Health Alliance International, Liga Inan Technical Brief 1 [77] |

Analysis of participation data from Liga Inan endline evaluation,Timor-Leste; N = 603 mothers with children under

2 years of age (breakdown between Intervention and Control

areas not provided) |

Registered pregnant mothers receive twice weekly SMS education and reminder messages and can request a call from their midwife. Midwives call all clients 3 weeks before due date. |

Improve uptake of maternal and neonatal health services |

70% of pregnant women in Intervention area participated, 82% using their own phone. 97% found the messages easy to understand and 53% reported sharing messages with another person. |

||

|

Feasibility studies – published literature: | ||||||

| Huda et al, 2018 [78] |

Mixed methods pilot study with pre/post quantitative surveys and post-intervention qualitative interviews (n = 21). N = 340 pregnant and lactating mothers in rural Bangladesh. |

2 × weekly IVR messages tailored to stage of pregnancy/infancy, bi-weekly nutrition counseling calls, call centre access and monthly unconditional cash transfers of BDT787 (US$10). |

Improve perceptions of maternal and infant nutrition |

96% of participants were satisfied with the IVR messaging content and frequency. 81% of call centre contacts were successful, and 50.9% of participants phoned the call centre at least once. Preferences for nutrition advice: 62.2% IVR + voice counseling; 32.7% voice counseling; 5.1% IVR. |

||

| Alhaidari et al, 2017 [79] |

Pilot randomized controlled trial in antenatal clinics affiliated with a maternity hospital in Iraq; N = 250 pregnant women. |

Weekly text messages tailored to stage of pregnancy. Hotline for pregnancy questions. |

Assess feasibility and acceptability of text messaging to improve uptake of ANC services. |

Median number of ANC visits was higher in intervention group (4 vs 2; P < 0.001). 60.8% of I-group made ≥1 hotline call, for a total of 314 calls. 90.7% would recommend the SMS service. |

||

|

Formative study – published literature: | ||||||

| Jennings et al, 2013 [80] |

4 in-depth interviews with nurses and 6 focus groups (2 each with HIV+ women, male partners & FLWs) in Nyanza, Kenya; N = 45, recruited through 2 hospital PMTCT programs |

n/a |

Assess perceptions of cell phone communication to support PMTCT service delivery |

Preferred mHealth platform combines SMS for reminders and basic information with voice counseling for discussion; health workers prefer in-person sessions |

||

|

Formative study – grey literature: | ||||||

| Napier & Peterson, 2013 [81] |

Doer/non-doer analysis of qualitative interviews with adolescent mothers in Honduras; n = 31 |

Initial intervention: monthly breastfeeding support groups, weekly SMS and additional voice counseling support |

Improved breastfeeding practices among adolescent mothers |

Identified technical and social barriers to cell phone support |

||

|

Programmatic case study – grey literature: | ||||||

| Health Alliance International [82] | Narrative description of intervention design, monitoring and lessons learned from the Liga Inan mHealth program in Timor-Leste. |

Registered pregnant mothers receive twice weekly SMS education and reminder messages and can request a call from their midwife. Midwives call all clients 3 weeks before due date. | Integration with Ministry of Health facilitates participation and sustainability. Telephone surveys indicate high user satisfaction with messages and a high rate of sharing content with family members. Participants value the enhanced communication with their midwife. In-depth interviews with midwives found high satisfaction with the service despite increased workload. Variations in access to health services affects uptake of recommended practices. |

|||

MNCH – maternal, newborn and child health, EBF – exclusive breastfeeding, ANC – antenatal care, IVR – interactive voice response, PMTCT – prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV

Table 5.

Job aid application studies and reports

| Study | Design | Intervention | Target outcomes | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intervention studies – published literature: | ||||

| Martinez-Fernandez et al, 2015 [83] |

Retrospective observational study of population level baseline to endline changes in mortality comparing intervention communities (n = 125) with non-intervention areas in rural Guatemala |

FLWs equipped with cell phone-based tools, including job aid app, distance learning modules, and access to supervisors for phone consultation. |

Maternal mortality, Infant mortality |

Maternal mortality rate decreased in intervention areas (309 to 254) but increased in control areas (338 to 558) (P < 0.05 between groups). Infant mortality rate decreased in both groups (25-13; 27-20) (P = 0.054 between groups). |

| McNabb et al, 2015 [84] |

Pre/post evaluation of pregnant mothers (n = 267) in Nigeria; baseline data collection at first ANC visit, endline 12 months later |

Job aid app to guide facility-based health workers through ANC protocols and track client data in real time; 13 BCC audio files embedded |

Improve quality of ANC care and client satisfaction |

Quality score increased from 13.33 (baseline) to 17.15 out of 25 (P < 0.0001); greatest improvements in BCC message delivery |

| Battle et al, 2015 [85] |

Mixed methods evaluation in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Quantitative: system generated monitoring data; N = 13 231 registered mothers who gave birth in the project period. Qualitative: semi-structured interviews with mothers (n = 27), FLWs (n = 25) and health facility staff (n = 12) |

Job aid app supporting safe deliveries through client registration, monitoring, BCC, communication with health facilities and money transfer for transport |

Increase uptake of facility-based delivery (FBD) and postnatal care |

FBD: 75% vs 35% in most recent Demographic & Health Survey. Postnatal care attendance: 88%. Interview findings: referral and communication functions increased FLW confidence; frequent contact with FLWs and transport service increased FBD but cost of FBD was a barrier |

| Shiferaw et al, 2016 [86] |

Non-randomized prospective controlled evaluation in 10 health facilities (5 intervention, 5 control) of Amhara region, Ethiopia. Exit interviews with mothers attending ANC: n = 933 (baseline); n = 1037 (endline). Chart review of ANC clients: n = 1224 |

Job aid app for facility-based health workers supporting client registration, ANC and postnatal care visit reminders, decision support, and pregnancy health information. Health workers contacted clients on receiving visit reminders. |

Increase in mothers with 4 ANC visits, FBD and postnatal care at each facility |

Results (I. vs C.): 4+ ANC visits: 27% vs 23.4% (AOR = 1.31; 95% CI = 1.00-1.72). FBD: 43.1% vs 28.4% (AOR = 1.98; 95% CI = 1.53-2.55). Postnatal care attendance: 41.2% vs 21.1% (AOR = 2.77; 95% CI = 2.12-3.61). |

| Hackett et al, 2018 [87] |

Cluster randomized trial in 32 villages in rural Tanzania; N = 572 mothers selected for postnatal survey |

Job aid app supporting FLWs with data management and real-time guidance for prenatal home visits |

Increase uptake of FBD |

FBD significantly more likely in I-group (74% vs 63%; OR = 1.96; 95% CI = 1.21-3.19; P = 0.01). |

| Ilozumba et al, 2018 [88] |

Quasi-experimental study in 3 sub-districts of rural Jharkhand, India; N = 2200 mothers with infants <12 months old |

2 sub-districts received NGO-led MNCH activities. Mobile for Mothers (MfM) app was added in 1 sub-district to support FLW home visits with data management and embedded multimedia BCC messages |

Improve maternal health knowledge, ANC attendance and FBD |

Mothers in the MfM group were significantly more likely than NGO or control groups to attend ≥4 ANC visits (OR = 1.23; 95% CI = 1.17-1.29; OR = 1.36; 95% CI = 1.30-1.42) and to have FBD (OR = 1.19; 95% CI = 1.13-1.25; OR = 1.34; 95% CI = 1.28-1.41) |

| Prinja et al, 2017 [89] |

Pre/post quasi-experimental study in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. Annual Health Survey data served as pretest; matched with posttest household survey sample (N = 3106 mothers equally divided between intervention & control areas). |

Job aid app supporting FLWs with data management and real-time guidance for home visits during pregnancy and infancy (ReMiND project) |

Improve uptake of MNCH services |

Large increases in both groups for 4 of 8 MNCH indicators. Significantly greater increases in the Intervention group for self-reporting illness during pregnancy (13.2 p.p.; P = 0.04) and after delivery (19.5 p.p.; P = 0.01) |

|

Intervention studies – grey literature: | ||||

| Borkum et al, 2015 [90] |

Cross-sectional survey in Bihar, India comparing mothers of infants <12 months old (n = 1550) in randomly selected intervention and control communities. Qualitative process evaluation: interviews with FLWs (n = 23) and project staff (n = 4) |

Job aid app for home visits during pregnancy and infancy, with multimedia BCC messages embedded |

Improve coverage and quality of FLW services |

Intervention group more likely to receive home visits prenatally, in first week postnatal, and for complementary feeding (P < 0.05), and more likely to report 3+ antenatal care visits, birth preparedness, and timely initiation of both breastfeeding and complementary feeding (P < 0.05). |

| BBC Media Action, 2016 [91] |

Observational study in Bihar, India, comparing mothers exposed to the Mobile Kunji intervention (n = 2543) vs unexposed (n = 956). Qualitative process evaluation: 4 focus groups and 28 in-depth interviews with FLWs |

Counseling tool (Mobile Kunji) combining visual aid with IVR messages accessed through FLWs’ personal phones |

Improve quality and engagement with BCC for key MNCH practices |

Exposed mothers more likely to have saved the FLW’s phone number (OR = 2.72) and to have fed infants 6-11 months old from at least one food group in past 24 h (OR = 1.72) but no effect on family planning practices. |

| World Vision, 2018 [92] |

Randomized controlled trial in Niger. N = 126 FLWs randomized equally to intervention and control groups were evaluated for their assessment of 544 sick children age 2-59 months |

Job aid app supporting Integrated Community Case Management for childhood illnesses |

Improved assessment of childhood danger signs and counseling for caregivers |

Preliminary results show no significant difference between groups for identification of cough, diarrhea or fever. Mixed results for counseling. Overall no added benefit from the app for management of priority illnesses. |

|

Implementation studies – published literature: | ||||

| Balakrishnan et al, 2016 [93] |

Observational study comparing monitoring data from FLWs in intervention districts of Bihar, India with government statistics for the rest of the state and for the intervention district in the previous year |

Job aid app for home visits during pregnancy and infancy, with multimedia BCC messages embedded |

Improve quality, equity and efficiency of FLW delivery of 8 core MNCH services: pregnancy registration; registration in first trimester; 3 ANC visits; ≥1 tetanus toxoid vaccine; >90 iron folic acid tablets; delivery in health facility; early initiation of breastfeeding; and ≥1 postnatal home visit. |

Coverage of all MNCH services was higher in implementation areas but statistical significance was not assessed. Utilization of MNCH services was similar between scheduled castes and others except for facility-based delivery. Instant data upload from app eliminated delay in data capture from paper forms. |

| Ilozumba et al, 2018 [94] |

Mixed methods assessment of factors influencing outcomes of Mobile for Mothers (MfM) study in Jharkhand, India. Quantitative surveys with mothers (N = 740) and FLWs (n = 57) participating in the intervention. Qualitative interviews with FLWs (n = 28), mothers (n = 32) and men (n = 31). |

Mobile for Mothers (MfM) app supporting FLW home visits with data management and embedded multimedia BCC messages |

Improve maternal health knowledge, ANC attendance and FBD |

MfM app increased FLWs’ knowledge, confidence and efficiency. Main barriers to ANC and FBD uptake were women’s workload, finances, household power dynamics and access to health services. |

|

Feasibility studies – published literature: | ||||

| McConnell et al, 2016 [95] |

Randomized trial in Kiambu county, Kenya. N = 104 postnatal mothers recruited from one private maternity hospital and individually randomized to home visit (n = 32), phone call (n = 41) and control (n = 31) groups |

3-d postnatal checklist administered by FLWs either by mobile phone or home visit, compared with standard of care |

Improve knowledge and care-seeking for postnatal danger signs |

Postnatal checklist administered to 76% of phone group and 59% in home visit group. Infant care-seeking occurred earlier in home visit (2.0 d, P = 0.014) and phone call groups (1.8 d, P = 0.034) compared with control. |

| Amoah et al, 2016 [96] |

Pilot study in 4 communities of rural Ghana; N = 323 pregnant women. Outcomes compared with preliminary survey (N = 100 women in project communities who were pregnant in past 5 years) |

Job aid app supporting FLWs with registration, data management and point-of-care guidance for prenatal clients; ultrasound scans conducted in project communities for mothers unable to attend hospital. |

Increase ANC attendance and FBD |

40 births in study period; 30 (75%) had >3 ANC visits; 25 (62.5%) had FBD compared with 54% and 33% in the preliminary survey. |

|

Formative studies – published literature: | ||||

| Modi et al, 2015 [97] |

Descriptive report of design and feasibility testing of ImTeCHO app for FLWs (n = 45) in Gujarat, India. Feasibility study: Interviews with 6 FLWs and 2 medical officers; focus groups with 9 FLWs and 6 Auxiliary Nurse Midwives; home visit observations |

Job aid app for FLWs with work flow scheduling, task monitoring, videos on key BCC messages; link to supervisory support for complex cases and ongoing monitoring |

Improve coverage of key MNCH services assigned to FLWs |

Job aid app well accepted & considered feasible but ongoing NGO support required for facilitation and technical support. |

| Kaphle et al, 2015 [98] |

Demographics questionnaire completed by FLWs (n = 15); home visit observations (n = 14) |

Job aid app for home visits |

To develop methods to analyze 1) the effects of app adoption on the quality and experience of care; and 2) personal factors influencing app usage by FLWs |

Quality scores were 33.4% higher for high users of the app (P = 0.04). No significant associations with individual factors were found. |

|

Qualitative studies – published literature: | ||||

| Hackett et al, 2018 [99] |

Qualitative study in rural Tanzania. In-depth interviews with FLWs (n = 60) and two rounds of focus group discussions with mothers (n = 56) participating in an mHealth trial |

Job aid app supporting FLWs with data management and real-time guidance for prenatal home visits |

Women’s reproductive health is a private matter in rural Tanzania, due to fear of exposure to witchcraft. FLWs are trusted confidants. FLWs believed smartphones enhanced data privacy but some mothers expressed concerns about data storage and who could access the phones. |

|

| Pimmer & Mbvundula, 2018 [100] |

Interpretive case study within the Millennium Village Project in rural Malawi. Focus group discussions with FLWs (n = 29) and interviews with supervisors (n = 3). |

Job aid app for FLWs with embedded audio counseling messages related to health topics including MNCH and nutrition. |

FLWs perceived the audio messages to support their work in three ways: i) legitimize the use of phones during home visits; ii) assist the FLW to deliver a comprehensive message; iii) support FLWs to persuade communities to adopt health practices. |

|

|

Qualitative study – grey literature: | ||||

| Treatman & Lesh, 2012 [101] |

Interviews with implementers (n = 8) of CommCare app deployments in India |

Job aid tool with embedded audio messages for BCC |

Improve quality of counseling by FLWs |

Audio messages improved FLW credibility and eased discussion of sensitive topics but design challenges with localization. |

|

Reviews & case studies – grey literature: | ||||

| Chamberlain, 2014 [102] |

Case study |

Counseling tool (Mobile Kunji) combining visual aid with IVR messages in Bihar, India |

User-centred design process: extensive formative research, prototype development; iterative testing & refinement. Partnerships built with 6 major mobile network operators who subsidize 90% cost of Mobile Kunji calls. >35 000 FLWs using the service with their own basic phones. |

|

| Ramachandran, 2013 [103] |

Case study |

Cell phone-based audio-visual counseling tool for FLWs in Orissa, India |

Iterative design process informed by qualitative data and concepts from theories of persuasion. Final tool used locally filmed video with built-in questions and pauses to encourage discussion. |

|

| Manthan Project, 2013 [104] |

Case study of mSAKHI app with summary findings from 2 pre/post quasi-experimental feasibility studies: i) self-learning and counseling (n = 86 FLWs); ii) postnatal care delivery (n = 57 FLWs) |

Job aid app with multimedia functions |

i) improved knowledge & counseling delivery by FLWs; ii) Improved coverage and quality of newborn care |

i) greater frequency & completion of BCC message delivery (P < 0.05 for 6/9 messages); ii) intervention group more likely to correctly assess newborn health (P < 0.05 for 5 of 7 skills) |

| Chatfield & Javinski, 2015 [105] |

Narrative review of CommCare evidence base, both published & grey literature (n = 40 papers) |

CommCare job aid tool for FLWs |

Documented evidence related to CommCare acceptability; contribution to improved access to care; quality, experience, and accountability of care; and changes in client knowledge & practices. |

|

| Flaming et al, 2016 [106] |

Narrative review of CommCare evidence base, both published & grey literature (n = 51 papers; 22 papers address MNCH) |

CommCare job aid tool for FLWs |

Descriptive review of evidence related to CommCare contribution to improvements in FLWs’ knowledge; performance and credibility; client knowledge and practices; and quality of care. Implementation challenges include technical difficulties, decrease in usage over time, and integrating data with local health systems. |

|

| Keisling, 2014 [107] |

Project case studies: i) pre/post evaluation (n = 206) with comparison group in Afghanistan; ii) supervisory app monitoring data in India |

CommCare job aid apps for FLWs |

Improved MNCH knowledge and practices |

i) changes in 7 of 15 indicators including birth preparedness, ANC and FBD; ii) 136% increase in clients asking questions during home visits; 78% of mothers served by app gave birth in facilities |

| World Vision, 2015 [108] |

Narrative overview of World Vision’s mHealth projects with country project examples from India, Indonesia, Sierra Leone & Uganda |

MOTECH Suite with apps supporting five MNCH project models including home visits by FLWs |

Strengthen community health systems |

16 projects in 21 countries; 7 projects have >100 users. Implementation lessons: high acceptability of apps; need adequate technology training and support to FLWs |

| MIRA Channel, 2015 [109] |

Project brief summarizing MIRA concept and results of pilot test with 50 FLWs |

Mobile phone “channel” integrating health communication and management functions for rural women in India |

Increase rural women’s access to health knowledge and care |

59% increase in ANC attendance, 49% increase in FBD and 41% increase in immunization coverage with MIRA use |

| World Vision, 2018 [92] | Narrative description of evaluation and research findings related to World Vision’s mHealth deployments for FLWs in 11 countries | CommCare job aid apps for FLWs | Process evaluation surveys in Sierra Leone and Uganda found high acceptance of job aid apps, particularly by beneficiaries with greater exposure to mHealth. Formative research in Mauritania and Tanzania guided program adaptions related to technology, contextualization and integration with Ministry of Health systems. Analysis of projects in Uganda, Sierra Leone and India using the mHealth Assessment and Planning for Scale (MAPS) toolkit identified site-specific strengths to leverage and challenges to address in ongoing program plans. |

|

FLWs – frontline health workers, ANC – antenatal care; BCC – behaviour change communication, FBD – facility-based delivery, MNCH – maternal, newborn and child health, IVR – interactive voice response

Table 6.

Interactive media study

| Study | Design | Interactive media intervention | Target outcomes | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intervention study – published literature | ||||

| Santoso et al, 2017 [114] | Randomized controlled trial with pre/posttest design in Indonesia; N = 38 couples from antenatal service at 3 health centres randomized equally to intervention or control. | Android app for husbands to monitor pregnancy progress and receive information on danger signs, care and treatment. Both groups received counseling. | Improve husbands’ birth preparedness and complication readiness (BP/CR scores) | BP/CR score (I. vs C.): Pretest: 60.4 vs 61.5 (NS); 3 week posttest: 72.9 vs 62.6 (P = 0.001); Postpartum posttest: 81.8 vs 71.3 (P < 0.001) |

Direct messaging

Direct messaging delivers brief, standardized messages to users’ phones, using either short-message-service (SMS) for written text, or Interactive Voice Response (IVR) technology for audio content. This is the oldest form of BCC using mobile phones, and still widely used; we identified more documents related to direct messaging than the other three delivery approaches combined (Table 1). These documents describe pilot and intervention studies, implementation research, formative studies and programmatic case studies targeting a range of MNCH outcomes (Table 2).