Bison engineer forage green-up

Bison migrate and graze in Yellowstone National Park. Image courtesy of the US National Park Service.

The Green Wave Hypothesis states that migrating herbivores follow the progression of young vegetation greening up from low to high altitudes or latitudes, given that young vegetation provides superior forage. However, it is unclear how the migrations of large herbivores that engineer their environment interact with the green wave. Chris Geremia et al. (pp. 25707–25713) tracked 64 bison, which migrate up to 100 km, in Yellowstone National Park between 2005 and 2015 while monitoring the greenness of the migratory landscape using satellite imagery. In early spring, the bison “surfed” the green wave, but consistently exhibited a stopover pattern where the green wave passed them by. Falling behind the wave did not appear to impact bison diet quality. Hence, the researchers set up experimental grazing plots and found that intense bison grazing removed more than half of plant tissue, preserving a low, dense plant stature and high forage quality. Further, changes in bison numbers over the decade of observation allowed the authors to examine of the effects of grazing intensity on movement of the green wave itself. According to the authors, heavy and repeated grazing caused rapid, intense, and long-duration greening, suggesting that the Green Wave Hypothesis may need modification to accommodate plant engineering by large herbivores. — P.G.

Penguin responses to climate change and human activity

A pair of chinstrap penguins and an egg at a breeding colony on Deception Island along the Antarctic Peninsula.

Krill is a main food source for Antarctic penguins. However, the historic harvesting of whales and seals in addition to recent anthropogenic climate change are thought to have led to shifts in krill abundance over the past century. To better understand the ecological implications of these changes, Kelton McMahon et al. (pp. 25721–25727) examined the diets of chinstrap and gentoo penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula by analyzing the nitrogen stable isotope values of amino acids in feathers from the 1930s, 1960s, 1980s, and 2010s. The authors found that both species had low trophic positions and primarily fed on krill during krill surpluses in the 1930s and 1960s caused by harvesting of krill-eating marine mammals. In contrast, during the latter half of the past century, gentoo penguins advanced a full trophic position and showed an adaptive shift from strictly eating krill to including fish and squid in their diets. Chinstrap penguins, however, continued to feed exclusively on krill. During the same time period, chinstrap penguins experienced severe population declines in the Antarctic Peninsula, whereas gentoo penguin populations increased. The findings suggest that species with specialized diets are more sensitive to human-induced environmental change than generalist foragers, according to the authors. — M.S.

Activated myelin-specific lymphocytes in multiple sclerosis

In multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system, the immune system attacks and damages myelin sheaths surrounding nerve fibers. Although CD4+ T cells have long been thought to play a central role in MS pathogenesis, recent findings have shown that CD8+ T cells outnumber CD4+ T cells in human brain lesions and may contribute directly to demyelination. Joseph Sabatino Jr. et al. (pp. 25800–25807) used a large panel of myelin peptide:MHC I tetramers—a standard for detecting and isolating antigen-specific CD8+ T cells—to identify myelin-specific CD8+ T cells in humans. Though these cells appear in similar numbers in both untreated MS patients and healthy controls, the authors found that MS patients exhibit relatively higher counts of memory and CD20-expressing myelin-specific CD8+ T cells, suggesting previous autoantigen response. In addition, the authors demonstrate that certain populations of activated myelin-specific CD8+ T cells were significantly reduced after anti-CD20 treatment. The findings suggest that MS may have an activated myelin-specific CD8+ T cell phenotype that can be targeted with therapies that deplete anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. — T.J.

Rapid lake drainage on the Greenland Ice Sheet

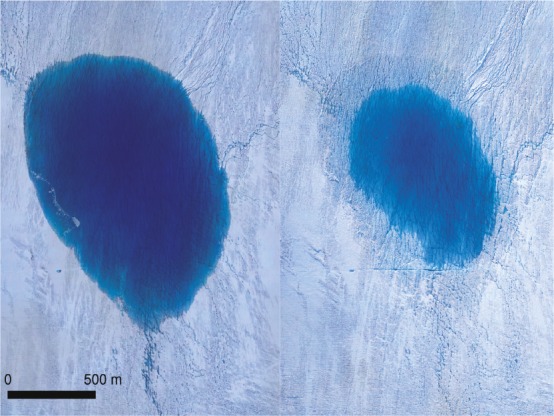

Aerial view of a lake on the Greenland Ice Sheet before (Left) and after drainage (Right).

Supraglacial lakes can drain to the bed of ice sheets in a matter of hours, altering ice dynamics on multiple timescales. Previously, field observations of such rapid drainage on the Greenland Ice Sheet were conducted in slow-flowing, land-terminating areas. Thomas Chudley et al. (pp. 25468–25477) used in situ instrumentation and custom-built drones to measure lake volume and discharge, ice flow and uplift, and seismic activity during drainage of a lake on a fast-flowing, marine-terminating glacier in west Greenland in July 2018. Ice uplift and ice flow acceleration were greatest approximately 4 km downstream from the lake. Such large distal responses to drainage have not been previously observed or predicted. In contrast to previous studies where lakes drained completely, only two-thirds of the lake volume drained. Such partial drainage events had previously been assumed to occur slowly over days, but, in this instance, the authors report, 5 million cubic meters drained in less than 5 hours. The results suggest that even partial drainage events rapidly deliver water to the bed. Hence, the number and impact of rapid drainage events may have been underestimated, according to the authors. — B.D.

Analyzing effects of the Justinianic Plague

Revisiting the Justinianic Plague. Image courtesy of Elizabeth Herzfeldt-Kamprath (The National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center, Annapolis, MD).

Current scholarly consensus indicates that the first plague pandemic, and in particular, its initial outbreak known as the Justinianic Plague, caused significant demographic, economic, and political changes between 541 CE and 750 CE. To determine how the Justinianic Plague affected Late Antique populations in Europe and the Mediterranean, Lee Mordechai et al. (pp. 25546–25554) examined contemporary literary sources, stone inscriptions, coinage, papyrus documents, pollen samples, Late Antique plague genomes, and mortuary archaeology. The authors found that several historical texts exaggerate plague mortality. Additionally, the authors found no detectable decrease in coin circulation, inscription production, or papyrus documents, suggesting continued economic vitality and no observable demographic decline after the plague onset. Further, the authors analyzed pollen evidence for agricultural production, which showed no decrease tied to plague mortality. An analysis of human burials demonstrated that the plague did not result in burial custom changes, such as those that occurred when the Black Death killed vast numbers of people. The results suggest that the demographic effects of the Justinianic Plague may have been overestimated, according to the authors. — M.S.