Abstract

Background

Considerable evidence supports the efficacy of e-interventions for mental health treatment and support. However, client engagement and adherence to these interventions are less than optimal and remain poorly understood.

Objective

The aim of the current study was to develop and investigate the psychometric properties of the e-Therapy Attitudes and Process questionnaire (eTAP). Based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), the eTAP was designed to measure factors related to client engagement in e-interventions for mental health.

Methods

Participants were 220 adults who reported current use of an e-intervention for mental health support. Participants completed the eTAP and related measures, with a subsample of 49 participants completing a one-week follow up assessment.

Results

A 16-item version of the eTAP produced a clear four-factor structure, explaining 70.25% of variance. The factors were consistent with the TPB, namely, Intention, Subjective Norm, Attitudes, and Perceived Behavioural Control. Internal consistency of the total and subscales was high, and adequate to good one-week test retest reliability was found. Convergent and divergent validity of the total and subscales was supported, as was the predictive validity. Specifically, eTAP Intentions correctly predicted engagement in e-interventions with 84% accuracy and non-engagement with 74% accuracy.

Conclusions

The eTAP was developed as a measure of factors related to engagement and adherence with e-interventions for mental health. Psychometric investigation supported the validity and reliability of the eTAP. The eTAP may be a valuable tool to understand, predict, and guide interventions to increase engagement and adherence to e-interventions for mental health.

Keywords: Adherence, Theory of Planned Behaviour, Engagement, Digital interventions, E-mental health, Dropout

Highlights

-

•

User adherence and engagement with digital interventions is not well understood, with a need for theory driven research

-

•

The e-Therapy Attitudes and Process questionnaire (eTAP) was developed with input from experts, users, and literature

-

•

The eTAP produced a four-factor structure, with factors consistent with the theory of planned behaviour

-

•

The validity and reliability of the eTAP was supported

-

•

Preliminary evidence was also found for the utility of the scale in predicting user engagement with digital interventions

1. Introduction

Interventions for mental health are increasingly being offered and delivered via online or digital means. Although terminology differs throughout the literature (e.g. online, digital, e-, m-interventions), these interventions, herein referred to as e-interventions, are typically aimed at increasing or enhancing access to mental health services through the use of technology (Clough and Casey, 2015a). Over half-a-billion people worldwide have downloaded at least one of the more than 100,000 available mental health Smartphone applications (Dorsey et al., 2017), with Smartphone ownership in developing countries, and willingness to use such approaches, often rivalling those of developed nations (Clough et al., 2017a). These e-interventions have the potential to overcome barriers to care, reduce unmet need, and enhance existing treatment services (Clough and Casey, 2011a, Clough and Casey, 2011b; Joyce and Weibelzahl, 2011; Meurk et al., 2016). Yet, despite the efficacy and advantages of e-interventions, their overall effectiveness is often limited by low client adherence, such as high rates of client dropout and low engagement (Donkin et al., 2011; Melville et al., 2010).

1.1. Treatment adherence

Poor engagement and dropout limit exposure to the full program or the required “dosage” of treatment and may negatively impact psychological outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviours (Donkin et al., 2011; Christensen et al., 2002; Ghaderi, 2006). Although not all clients who dropout of mental health interventions have negative outcomes, there is evidence to suggest that continually engaging with psychotherapy offers substantial benefits (Sheeran et al., 2007). High dropout also impacts research into e-interventions by reducing generalisability of results and the statistical power of randomised controlled trials (Schneider et al., 2014). However, despite being identified as a consistent problem within research and practice, issues of non-adherence remain poorly understood.

The most common approach to understanding factors related to adherence has been through correlational studies, which have examined associations between adherence and various personality and demographic variables. Similarly, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of controlled trials have also been used to examine factors associated with client adherence. However, these approaches have produced inconsistent and at times conflicting results (Clough and Casey, 2011b; Casey & Clough, 2016). Attitudes towards e-interventions and barriers to care have also been investigated as tools for predicting uptake and usage of interventions (e.g., Klein and Cook, 2010; Casey et al., 2014), although it has been acknowledged that these constructs likely to do not provide a complete understanding of client engagement and have also largely been lacking in theoretical basis. It has been argued that this is likely due to the limited theoretically driven research in this field (Donkin et al., 2011; Beatty and Binnion, 2016; Apolinário-Hagen et al., 2017). There have been calls for a greater focus on theory led research and innovative design to target the unique challenges and barriers associated with e-interventions (Clough and Casey, 2015b).

1.2. The Theory of Planned Behaviour

One of the most widely used theories concerning client adherence within healthcare has been the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB; Ajzen, 1985, Ajzen, 1991). The theory asserts that behavioural intentions are the immediate antecedents to behaviours and hence, the stronger the intention to perform a behaviour, the greater the likelihood of that behaviour actually occurring. Behavioural intentions refer to an individual's willingness to perform a given behaviour (e.g. ‘I intend to use my online intervention for mental health’) and have been shown to be reliable predictors of health behaviour (McEachan et al., 2011). Additionally, the TPB has considerable advantages over other theories of adherence in the field, such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), in that while TAM may be easier to apply, the TPB typically provides more specific information that can guide development of interventions, and has greater capacity to account for the effects of behavioural control and the influence of others on individuals' decision making processes (Mathieson, 1991).

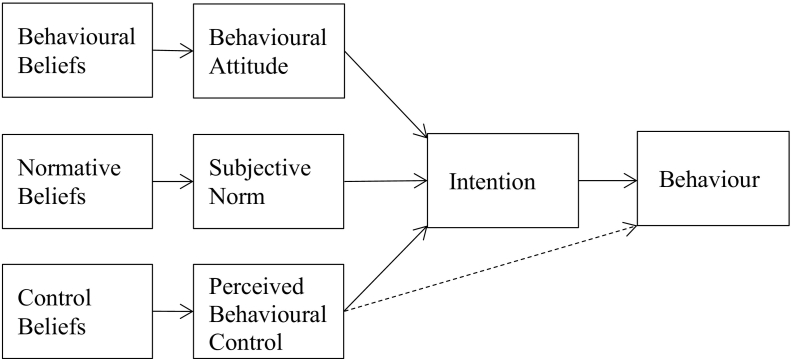

According to the TPB, behavioural intentions are influenced by three factors, as illustrated in Fig. 1: Attitudes, Subjective Norms, and Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC) (Ajzen, 1991, Ajzen, 2002). Behavioural attitudes refer to how positively or negatively an individual views the specific behaviour (e.g. ‘I find online interventions for mental health to be helpful’), while subjective norm refers to an individual's perception of whether engagement in the behaviour would be considered normative or appropriate for themselves, based on the judgements of significant others (e.g. ‘Those people who are important to me would support me using online interventions for mental health’). PBC refers to an individual's perceptions of their self-efficacy and capacity to perform the required behaviour/s (e.g. ‘I have complete control over whether I use online interventions for mental health’), and not only influences behavioural intention, but also directly influences behaviour.

Fig. 1.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991).

According to Ajzen (1991) these three antecedents to intentions are influenced by an individual's beliefs. Behavioural beliefs relate to an individual's degree of preference for a particular behaviour and result in the development of either negative or positive attitudes. Normative beliefs arise from an individual's internalised social pressure to perform a specific behaviour and result in subjective norms. Lastly, control beliefs relate to an individual's perceptions of the degree of difficulty in performing a behaviour and result in PBC (Ajzen, 2002).

The TPB has been used in the prediction of health behaviours such as adherence to diet (White et al., 2010), exercise (De Vivo et al., 2016), and medication (Kopelowicz et al., 2015) and several meta-analyses (Albarracin et al., 2001; Armitage and Conner, 2001) have demonstrated that the TPB predicts intentions and behaviours across a variety of health domains. There have been several attempts to develop scales that apply the TPB model to measure adherence and engagement in e-interventions (Wojtowicz et al., 2013; Erdem et al., 2016; Hebert et al., 2010). However, the available scales have lacked appropriate investigation with regards to validity and structure, and have typically been developed ad hoc, without expert or user input. Furthermore, none of these measures have been developed in accordance with the guidelines proposed by Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) for measures based on the TPB. One scale, the Therapy Attitudes and Process Questionnaire (TAP) (Clough et al., 2017b), has been validated for use in understanding factors related to adherence to psychotherapy. This scale was developed in line with Ajzen's guidelines for TPB questionnaire construction (Ajzen, 2006), with the exception of including expert but not target group elicitation in the construct of items. The TAP demonstrated strong psychometric properties with regards to validity and reliability, and was designed to be brief enough for regular administration (Clough et al., 2017b). However, the TAP was designed specifically for use in face-to-face (F2F) psychotherapy, and in its current form is not suitable for use in e-interventions. Development of a psychometrically valid and theoretically grounded tool for understanding client adherence to e-interventions would enable better identification of client risk factors for non-adherence, thereby allowing for better use of, and outcomes associated with, e-interventions.

1.3. The current study

The aim of the current study was to report on the development and testing of a scale to understand client adherence to psychological e-interventions. Previous research has demonstrated that the TPB provides a useful framework to understand client adherence to psychological interventions, with the TAP (Clough et al., 2017b) providing a useful measure of this. However, as the TAP was developed specifically for F2F treatment the current research focused on the adaptation and testing of the TAP for use with e-interventions. Detail regarding the development process of the eTAP is provided later in this paper. The resulting eTAP was tested among a large sample of users of e-interventions for mental health. The psychometric properties of the resulting eTAP were investigated in regard to structural validity, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent, divergent, and predictive validity.

Structural validity was investigated in an exploratory manner, with reference to the performance of items and factors, and the theoretical basis of the model. It was predicted that the measure would demonstrate satisfactory estimates of internal consistency and test-retest reliability, which would be comparable to the original TAP (Clough et al., 2017b) questionnaire. Further, it was hypothesized that the items/factors (depending on emergence of structure) of the eTAP would converge and diverge appropriately, with related constructs, as based on the theoretical underpinnings of the measure (Table 1). Lastly, it was predicted that the eTAP would significantly predict user engagement with e-interventions over a one-week period.

Table 1.

Hypothesized relationships between TPB constructs and relevant measures.

| Attitudes | Subjective Norms | Perceived Behavioural Control | Behavioural Intentions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Social Support | – | Convergent | – | – |

| Locus of Control | – | – | Convergent | – |

| Self-Stigma of Seeking Help | – | – | – | Convergent |

| Attitudes towards Psychological Online Interventions | Convergent | – | – | – |

| Self-Efficacy to use the Internet | – | – | Convergent | – |

| Help-Seeking Intentions for Online Interventions | Convergent | Convergent | Convergent | Convergent |

| Help-Seeking Intentions for F2F Professional Interventions | Divergent | Divergent | Divergent | Divergent |

2. Method

2.1. Participants

In determining minimal sample size for factor analysis (Fabrigar et al., 1999), this study adopted the guidelines outlined by the consensus based standards for the selection of health status measurement instruments (COSMIN; Mokkink et al., 2010; Prinsen et al., 2018), which endorse a participant-to-variable ratio of 7:1. As such, a minimal sample size of 217 (7 × 31 items = 217) was required.

Three hundred and sixty individuals responded to an invitation to participate in this study. Participants were required to be currently using an e-intervention for mental health, with a definition and examples provided to prospective participants. Participants were excluded if they did not progress beyond the initial demographic questions (n = 139) or demonstrated data entry errors in their responses (n = 1), leaving a final sample of 220 participants for the primary analyses. A sub-sample of participants (n = 49) provided matched survey data in a follow up study conducted one week after initial survey completion.

The sample for the primary analyses was comprised of 178 (81%) females, 35 (16%) males, and 7 (3%) individuals who identified their gender as other. Ages ranged between 17 and 64 years (M = 27.60, SD = 11.37). A sub-sample of this population were undergraduate students enrolled in an introductory psychology course (N = 51) who received partial course credit for their participation and who were included if they were 17 years of age (n = 7) or older. The majority of the respondents were Caucasian (71%), single/never married (66%), and reported using mobile/tablet applications as their current type of e-intervention (52%). Additionally, almost half (49.5%) of respondents reported currently receiving assistance or support for an emotional or mental health concern from one or more health professionals. The mean chronicity of mental health concerns within the sample was 7.22 years (SD = 9.79 years). The follow-up sample, tested one week following completion of the first survey, was comprised of seven (14.23%) males and 42 (85.71%) females (N = 49), aged between 17 and 60 years (M = 26.24, SD = 10.56).

2.2. Materials and measures

2.2.1. eTAP

The eTAP was developed based on the TAP (Clough et al., 2016), which measures factors related to client engagement in F2F psychotherapy. It has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including a clear four factor structure reflecting the four constructs of the TPB, high internal consistency (α ranging from 0.88 to 0.94), and acceptable to good test-retest reliability (0.65 to 0.80) (Clough et al., 2017b).

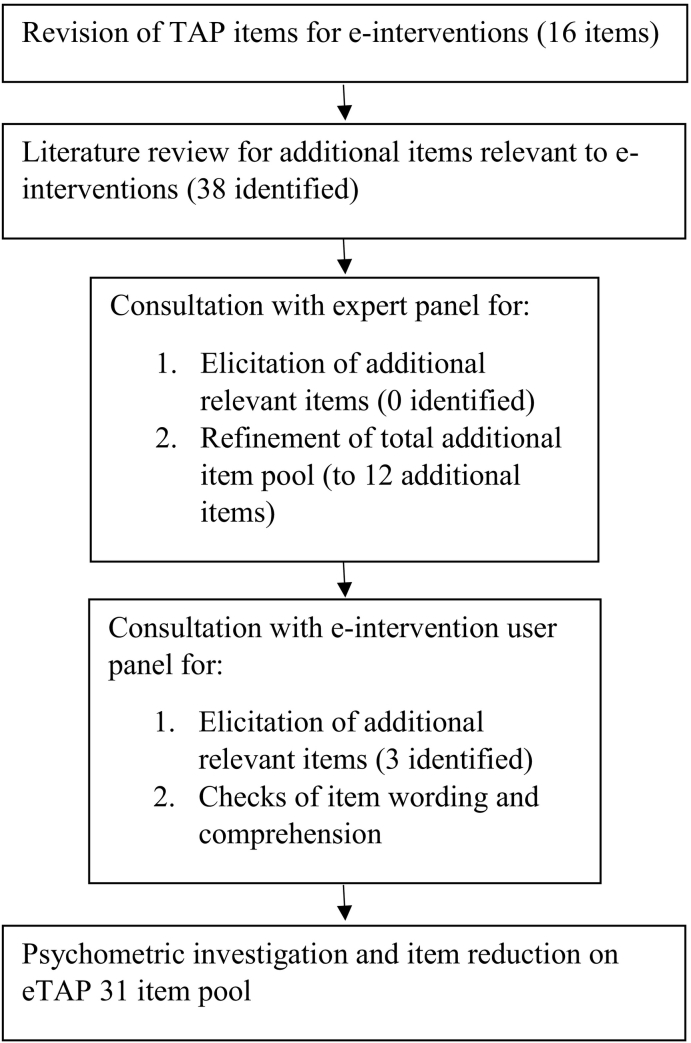

The development of the eTAP was conducted over several phases (Fig. 2). Firstly, items from the original TAP (Clough et al., 2017b) were modified to reflect engagement with e-interventions. For example, the TAP item ‘I find psychotherapy to be’, was modified to ‘I find online interventions for mental health to be’. Secondly, previous literature in the field was reviewed and a total of 38 items that related to engagement with e-interventions were added to the item pool. This was deemed necessary as e-interventions may be associated with unique aspects of attitudes, subjective norms, PBC, and intentions when compared to F2F interventions (Klein and Cook, 2010). As appropriate, the additional items were reworded to reflect the structure and style of those from the original TAP.

Fig. 2.

eTAP item pool development process.

Thirdly, an expert panel of five clinical psychologists, selected based on familiarity with the TPB and involvement with e-interventions in clinical practice, was asked to complete an elicitation survey designed to evoke ideas around how people use or do not use e-interventions. The questions were based on the guidelines from Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) for developing items for a TPB questionnaire. The panel was also asked to rank the top four items (from the 38 added from the literature) they believed best assessed each of the four TPB constructs, as was consistent with the development procedures for the TAP. For each of the four TPB constructs, the three highest ranked items (3 × 4 = 12) were included along with the 16 modified TAP items to create the preliminary 28-item eTAP.

Lastly, the preliminary eTAP was supplied to a sample of participants who self-reported currently using e-interventions (n = 8). Participants were given the same elicitation survey as described above and in addition were asked whether they could comprehend each item. A total of three additional items were included based on results of this elicitation study. The eTAP that was put forward for psychometric evaluation therefore consisted of 31 items.

The 31-item eTAP was developed to test the four constructs identified by the TPB as important in the understanding of behavioural engagement: attitudes; PBC; subjective norm; and intention. Nine items were designed to assess attitudes towards e-interventions and were constructed using 7-point bipolar adjective scales as suggested by Fishbein and Ajzen (2010). Seven items were designed to assess perceptions of subjective norms, eight items were designed to assess PBC, and seven items were designed to assess intention to use e-interventions. Items designed to assess subjective norm, PBC, or intention, utilised 7-point Likert scales, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

2.2.2. Scales used for tests of validity

A number of established scales with strong psychometric properties were selected for use in tests of convergent and divergent validity. Perceived levels and quality of social support were measured using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; present study alpha = 0.93; Zimet et al., 1988), self-stigma and impact on help-seeking behaviours related to obtaining psychological support was measured using the Self-Stigma of Seeking Help Scale (SSOSH; present study alpha = 0.85; Vogel et al., 2006), attitudes towards internet-based psychological interventions was measured using the Attitudes towards Psychological Online Interventions Questionnaire (APOI; present study alpha = 0.77; Schröder et al., 2015), locus of control was measured using the Internal-External Scale (I-E Scale; present study alpha = 0.69; Rotter, 1966), self-efficacy to use the internet was measured using the Internet Self-Efficacy Scale (ISS; present study alpha = 0.93; Kim and Glassman, 2013), and help-seeking intentions was measured using the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ; present study alpha = 0.74; Wilson et al., 2005). For the present study the GHSQ was modified according to Klein and Cook's (2010) categorization of online services, with all non-professional help-seeking services replaced with online therapy options.

2.2.3. Engagement

Engagement was assessed one week following completion of the original survey. Participants were asked if they had used their e-intervention for mental health in the seven consecutive days between testing time-points (dichotomous response: Yes/No). This dichotomous measure of engagement was selected over continuous measurement (such as time spent engaging with services) due to the heterogeneity of e-interventions expected to be used by participants, and that these e-interventions may have different expectations of optimal client engagement.

2.2.4. Demographic variables

Chronicity, prior contact with psychological services, gender, age, recruitment source, and type of e-intervention used were measured by a series of self-report items.

2.3. Design

The structural validity of the eTAP was assessed by means of a factor analytic design, with a correlational design used to assess convergent, divergent, and predictive validity, and test retest reliability.

2.4. Procedure

Ethical clearance was obtained from the associated university prior to commencement of data collection. Participants were recruited via posts placed on social media sites, mental health forums, and university research recruitment sites and participant pools. Participants were asked to complete an online survey, of approximately 30 min duration. Online consent was obtained and no identifying data were collected, with the exception of participants who elected to partake in an optional prize draw (draw of six $50 AUD gift vouchers) and/or follow-up study. In these instances, either a phone number and/or email address were provided and stored separately from survey data. To ensure confidentiality, participants were asked prior to beginning the survey to generate an unidentifiable unique code in accordance with recommendations of Kristjansson et al. (2014). This code was used to link data over time. Upon completion of this survey, participants who were students were directed to an external site where they were provided with partial course credit. Respondents who identified that they wished to participate in the follow-up survey were emailed a link to the survey one week after completing the initial survey. The follow-up survey consisted of: unique code generation, demographic questions, eTAP, engagement questions, and optional additional entry into a second prize draw. The follow up survey took approximately 15 min to complete.

3. Results

3.1. Data screening and assumptions

Examination of the data indicated some small deviations from normality with several variables of the eTAP being negatively skewed. However, given the robust nature of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) in relation to skewness (Tabachnick et al., 2013) these deviations were not considered problematic. Spot checks of scatterplots were performed, with approximate linear relationships present and no evidence of curvilinearity identified. Several univariate outliers were identified. Multivariate normality was assessed (utilising Mahalanobis Distances), with 17 outlier cases identified. To test the impact of these outliers on the analysis, the EFA was run with and without the cases included. No substantive differences in results were identified. Consequently, the outliers were retained as they were not impacting on inferential decisions (Tabachnick et al., 2013). Multicollinearity was assessed with reference to correlations (Appendix A), tolerance, and variance proportions, and was not considered to be problematic (Tabachnick et al., 2013).

3.2. Initial factor analysis

3.2.1. Structure

EFA was chosen to investigate the factorial validity of the eTAP, as at this stage of development confirmatory factor analysis would be considered premature (Pallant, 2010). Principle Axis Factoring (PAF) with promax rotation was selected as it is robust against violations of normality and suitable for the moderately high item correlations observed in the current data (Tabachnick et al., 2013). The 31 items were considered appropriate for factor analysis, based on the inter-item correlations, communalities (all greater than 0.30), Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure (0.93), and significant Bartlett's Test of Sphericity (χ2 (465) = 5931.00, p < .001).

Extracting factors greater than 1.00 revealed the presence of five factors. However, inspection of the scree plot revealed a slight break after the fourth factor. Based on Catell's (1966) scree test and the theoretical underpinnings of the eTAP, it was decided to further investigate both a five and four-factor solution. The five-factor solution resulted in numerous cross-loadings and factors which were not theoretically meaningful. The most parsimonious solution, with fewest cross-loadings and most theoretically meaningful factors, was the four-factor solution, which explained a total of 62.32% of the variance. Factors explained 44.02%, 8.32%, 5.73%, and 4.26% of the variance respectively. The rotated four-factor solution revealed the presence of simple structure, with all factors showing a number of high loadings, and all but three items loading onto a single factor (Table 2). One item (item 14) resulted in a factor loading greater than 1, however, given that an oblique rotation was used and all assumptions for this analysis were met, this loading was not deemed problematic (Pett et al., 2003).

Table 2.

Promax rotated factor structure and communalities of the 31 eTAP items.

| Item | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | Communalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21. I find online interventions for mental health to be: not helpful/helpful | 0.95 | 0.47 | |||

| 8. I find using online interventions for mental health to be: unpleasant/pleasant | 0.89 | 0.72 | |||

| 17. I find online interventions for mental health to be: not credible/credible | 0.83 | 0.63 | |||

| 13. I find using online interventions for mental health to be: harmful/beneficial | 0.82 | 0.80 | |||

| 7. I find using online interventions for mental health to be: bad/good | 0.79 | 0.72 | |||

| 29. I find online interventions for mental health to be: impersonal/personal | 0.73 | 0.82 | |||

| 1. I find online interventions for mental health to be: negative/positive | 0.64 | 0.54 | |||

| 25. I believe an online intervention for mental health, compared to face-to-face therapies is: less effective/more effective | 0.58 | −0.47 | 0.51 | ||

| 10. I am confident that I can use my online intervention for mental health | 0.52 | 0.63 | |||

| 31. I think my personal information provided when using an online intervention for mental health is: insecure/secure | 0.48 | 0.39 | |||

| 30. I am capable of making time to engage in online intervention | 0.31 | 0.38 | |||

| 26. I would feel comfortable using an online intervention for mental health program on my own | 0.31 | 0.38 | |||

| 14. It is likely I will use my online intervention for mental health in the next week | 1.02 | 0.89 | |||

| 11. I will use my online interventions for mental health in the next week | 0.99 | 0.83 | |||

| 4. I intend to use my online intervention for mental health in the next week | 0.94 | 0.80 | |||

| 20. I intend to ensure I have access to the required technology to use my online intervention for mental health in the next week | 0.74 | 0.64 | |||

| 28. I intend to make time to complete the required homework/activities for my online intervention for mental health in the next week | 0.73 | 0.64 | |||

| 24. I plan to complete the required homework/activities for my online interventions for mental health in the next week | 0.73 | 0.69 | |||

| 3. I intend to continue using my online intervention for mental health | 0.51 | 0.61 | |||

| 15. Those people who are important to me would approve of me using online interventions for mental health | 0.85 | 0.80 | |||

| 9. Most people who are important to me would approve of me using online interventions for mental health | 0.82 | 0.73 | |||

| 2. Those people who are important to me would support me using online interventions for mental health | 0.74 | 0.59 | |||

| 19. Those people who are important to me think online interventions for mental health are credible | 0.73 | 0.70 | |||

| 23. Those people who are important to me think online interventions for mental health are effective ways of treating mental health concerns | 0.73 | 0.69 | |||

| 6. Those people who are important to me would want me to use online interventions for mental health | 0.73 | 0.76 | |||

| 22. I possess the required technical knowledge to use online interventions for mental health | 0.76 | 0.55 | |||

| 5. I have complete control over whether I use online interventions for mental health | 0.56 | 0.42 | |||

| 12. It is mostly up to me whether I use my online interventions for mental health in the next week | 0.55 | 0.33 | |||

| 18. I am confident using the technology for my online intervention for mental health | 0.52 | 0.56 | |||

| 27. Those people who are important to me think that compared to face-to-face therapy, online interventions are as effective in treating mental health concerns | 0.43 | 0.38 | −0.47 | 0.44 | |

| 16. I think I can use my online intervention for mental health | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.66 |

Note: Item loadings below 0.30 are suppressed.

3.2.2. Reducing the item pool

The four highest loading items on each factor were selected to construct shorter scales intended to facilitate ease of administration in clinical settings, as was consistent with the construction of the original TAP (Clough et al., 2017b). The final scale consisted of 16 items that were subject to another EFA. The 16-item eTAP is provided in Appendix B.

3.3. Factor analysis of the final scale

3.3.1. Structure

The item pool was found to be suitable for factor analysis (KMO = 0.90), Bartlett's Test of Sphericity (χ2 (120) = 2807.40, p < .001, communalities reported in Table 3). Parallel analysis is a robust extraction method that minimises over-identification of factors based on sampling error (Green et al., 2015). Therefore, a parallel analysis was performed on the final item pool as an additional check of factor structure. Parallel analysis confirmed the presence of four factors, with the fifth factor containing an eigenvalue (λ = 0.24) that was less than the average eigenvalue (λ = 0.25) and the 95th percentile eigenvalue (λ = 0.29). PAF analysis of the 16 items using promax rotation also revealed the presence of four factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1.00. PAF explained a total of 70.25% of variance, with 44.86%, 12.58%, 7.22%, and 5.59% of the variance explained across the four factors. An inspection of the scree plots from the parallel analysis and PAF revealed a clear break after the fourth factor. The parallel analysis, Kaiser criteria, Catell's (1966) scree test and the theoretical underpinnings of the eTAP determined the retention of four factors. The rotated solution revealed the presence of simple structure, with all four factors showing a number of high loadings (Table 3). All variables, but one (item 19) loaded onto a single factor. This item ‘Those people who are important to me think online interventions for mental health are credible’ loaded on both Factor 2 and Factor 3. As its communality was moderately high (0.58) this indicated that the item had a unique contribution to the measure. Consequently, it was decided to keep the item and further evaluate its contribution to the internal consistency of both Factor 2 and Factor 3 (Fabrigar et al., 1999). The interpretation of the four factors was consistent with the four factors of the TPB. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, all factors correlated significantly, either moderately or highly, with other factors.

Table 3.

Promax rotated factor structure and communalities of the 16-item eTAP.

| Item | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | Communalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11. I will use my online intervention for mental health in the next week | 0.98 | 0.90 | |||

| 14. It is likely I will use my online intervention for mental health in the next week | 0.98 | 0.92 | |||

| 4. I intend to use my online intervention for mental health in the next week | 0.93 | 0.86 | |||

| 20. I intend to ensure I have access to the required technology to use my online intervention for mental health in the next week | 0.64 | 0.58 | |||

| 21. I find online interventions for mental health to be: not helpful/helpful | 1.00 | 0.88 | |||

| 13. I find using online interventions for mental health to be: harmful/beneficial | 0.86 | 0.84 | |||

| 8. I find using online interventions for mental health to be unpleasant/pleasant | 0.83 | 0.68 | |||

| 17. I find online interventions for mental health to be: not credible/credible | 0.82 | 0.64 | |||

| 15. Those people who are important to me would approve of me using online interventions for mental health | 0.98 | 0.90 | |||

| 9. Most people who are important to me would approve of me using online interventions for mental health | 0.91 | 0.79 | |||

| 2. Those people who are important to me would support me using online interventions for mental health | 0.76 | 0.58 | |||

| 19. Those people who are important to me think online interventions for mental health are credible | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.58 | ||

| 22. I possess the required technical knowledge to use online interventions for mental health | 0.87 | 0.63 | |||

| 12. It is mostly up to me whether I use my online interventions for mental health in the next week | 0.71 | 0.47 | |||

| 5. I have complete control over whether I use online interventions for mental health | 0.62 | 0.48 | |||

| 18. I am confident using the technology for my online intervention for mental health | 0.42 | 0.52 |

Note: Item loadings below 0.30 are suppressed.

Table 4.

Factors intercorrelations for the 16-item eTAP.

| Factor | Intention | Attitude | Subjective Norm | PBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention | 1.00 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.35 |

| Attitude | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.55 | |

| Subjective Norm | 1.00 | 0.59 | ||

| PBC | 1.00 |

Note. Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach's Alpha (N = 220).

3.3.2. Factor interpretation

Factor 1, Intention, consisted of four items and accounted for 44.86% of the variance. This factor focused on intentions to use and continue using e-interventions for mental health. Factor 2, Attitude, consisted of four items and accounted for 12.58% of the variance. This factor focused on attitudes and beliefs towards using e-interventions for mental health. Factor 3, Subjective Norm, consisted of four items and accounted for 7.22% of the variance. This factor focused on perceptions of how the important people in participants' lives felt about them using e-interventions for mental health. Factor 4, Perceived Behaviour Control, consisted of four items and accounted for 5.59% of the variance. This factor focused on perceptions of control regarding use of e-interventions for mental health.

3.4. Reliability analyses

3.4.1. Internal consistency

High internal consistency for the total scale and individual subscales of the eTAP was found (Table 5). Item 19, which cross-loaded on two factors, was included in the reliability analyses for both Factors 2 and 3. The decision was made that this item be included with Factor 3 due to making the most impact on this factor's coefficient alpha, and having the most consistent theoretical similarity to other items in this factor (Fabrigar et al., 1999).

Table 5.

Internal reliability coefficients for the 16-item eTAP.

| Scale | Number of items | Internal consistency |

|---|---|---|

| Total scale | 16 | 0.92 |

| Subjective Norm | 4 | 0.89 |

| Intention | 4 | 0.94 |

| Attitude | 4 | 0.92 |

| PBC | 4 | 0.78 |

Note. Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach's alpha (N = 220).

3.4.2. Test retest reliability and standard error of measurement (SEM)

Utilising Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (Agreement, 2, random model), the one-week test retest reliability of the total scale was acceptable (0.72, SEM = 6.72), with the test retest of the subscales ranging from acceptable to good (Intention = 0.67, SEM = 3.81; Attitudes = 0.76, SEM = 1.91; PBC = 0.67, SEM = 1.89; subject norm = 0.75, SEM = 2.64).

3.5. Validity analyses

3.5.1. Convergent and divergent validity

Table 6 displays the correlations relating to analyses of convergent and divergent validity. Support for the convergent validity of the eTAP was found with expected relationships between: the MSPSS and Subjective Norms subscale; ISS and PBC subscale; APOI and attitudes subscale; and GHSQ online help seeking options and all eTAP scales except PBC. Moderate correlations were also found between the validity scales and other eTAP subscales (Table 6). This finding was not specifically predicted, although it was not surprising given the eTAP subscales were found to be related to each other. Within each of the previously mentioned relationships, the strongest correlations for validity measures were with the eTAP subscales that were directly hypothesized (Table 1), supporting the convergent validity predictions. Three convergent validity predictions were not supported. The relationship between the Intentions subscale and the SSOSH was not significant, as was the relationship between the PBC subscale and the IE scale and GHSQ online help-seeking scale. However, each scale of the eTAP demonstrated predicted convergent validity with at least one of the predicted measures. All correlations between eTAP scales and the GHSQ professional help-seeking scale were small and non-significant, supporting the predicted divergent validity of the scale.

Table 6.

Convergent and divergent validity of the eTAP.

| eTAP Subjective Norms | eTAP PBC | eTAP Intentions | eTAP Attitudes | eTAP Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSPSS | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.18⁎ | 0.05 | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ |

| IE Scale | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| ISS | 0.18⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.18⁎ | 0.19⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ |

| SSOSH | 0.03 | 0.17⁎ | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| APOI | 0.40⁎⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.56⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ |

| GHSQ: Professional Help Seeking Options | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| GHSQ: Online Help Seeking Options | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.12 | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.47⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

3.5.2. Predictive validity

Logistic regression was performed to determine if the eTAP significantly predicted one-week engagement (dichotomous) with e-interventions (Table 7). Engagement data were available for 47 of the 49 follow up sample respondents. Of these, 24 participants reported engagement with their e-intervention in the week following completion of the initial eTAP, with 23 participants reporting lack of engagement in this period.

Table 7.

Logistic regression predicting likelihood of engaging with e-intervention.

| Variables | 95% Confidence Interval for Odds ratio |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | B | Wald Chi-Square | Odds ratio | Lower | Upper | |

| PBC | 0.09 | 0.23 | 1.95 | 1.26 | 0.91 | 1.74 |

| Attitudes | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.39 | 1.10 | 0.82 | 1.47 |

| Subjective Norm | 0.05 | −0.12 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.67 | 1.18 |

| Intentions | 0.74⁎⁎ | −0.40⁎⁎⁎ | 11.38 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.85 |

| (Constant) | 2.68 | 0.71 | 14.65 | |||

Engagement YES = 0, NO = 1.

p < .01.

p < .001 (N = 47).

The model contained four predictors (Subjective Norm, Intention, Attitude, and PBC). A test of the full model against a constant-only model was statistically significant, (χ2 (4, N = 47) = 28.65, p < .001), indicating that the predictors, as a set, significantly distinguished between those who engaged with e-interventions (in the week following eTAP completion) and those who did not. The variance in engagement accounted for was moderate (Nagelkerke's R2 = 0.61), indicating a moderately strong relationship between the predictors and engagement. The eTAP predicted engagement with 84% accuracy and dropout with 74% accuracy.

According to the Wald criterion, only Intention made a significant contribution to prediction (p = .001). Attitudes, PBC and Subjective norms were not significant predictors. A model run with Intention omitted was not significantly different from a constant only model (χ2 (3, N = 47) = 2.65, p = .449). However, this model was significantly different from the full model (χ2 (1, N = 47) = 20.88, p < .001). This supports the finding that Intention towards using e-interventions was the only statistically significant predictor of engagement with e-interventions. Odds ratio indicated that when Intention was raised by one scale point participants were 0.67 times more likely to engage with their e-intervention.

4. Discussion

The aim of the current study was to develop and investigate the psychometric properties of a scale, utilising the TPB, to understand client adherence to psychological e-interventions. An existing scale, the TAP, was adapted for this purpose, with a comprehensive review of the literature, consultation with clinical and research experts in the field, and consultation with a panel of current users of e-interventions for mental health. This process enabled a thorough check of content validity of the item pool, and is consistent with best practice for recommendations for the development of health questionnaires (Mokkink et al., 2010; Prinsen et al., 2018). The psychometric properties of the eTAP were tested, with a 16-tem version demonstrating strong structural validity (four factors, consistent with TPB model, explaining approximately 70% of variance), good convergent, divergent, and predictive validity, adequate to good test-retest reliability, and good internal consistency. Estimates of internal consistency and test-retest reliability were comparable to those of the original TAP (Clough et al., 2017b).

The convergent and divergent validity of the eTAP was tested through a series of correlational analyses. Three predictions of convergent validity were not supported. No relationship was found between eTAP intention and self-stigma of seeking help. Arguably, the absence of a relationship between the intentions subscale and self-stigma for seeking help may support the notion that there are important differences between F2F and e-interventions. That is, that stigma may not be strongly related to intentions to seek help via e-interventions, which in itself is thought to be one of the advantages of these treatment modalities (Casey et al., 2014). There was also no relationship between PBC and intentions to seek help online or locus of control. It is possible that the lack of relationship between the PBC subscale and the online help-seeking options of the GHSQ could be associated with the focus of the GHSQ on measuring likelihood of an individual to use the suggested services (Klein and Cook, 2010; Wilson et al., 2005). Indeed, there are known problems with existing help-seeking measures, particularly with regards to scope, content validity, and predictive validity (White et al., 2017). Indeed, the construct of PBC extends beyond likelihood, including whether a person believes the target behaviour is within their volitional control, which may explain the lack of relationship with help-seeking intentions as measured by the GHSQ. Similarly, although it was predicted that locus of control may share some overlap with PBC, it appeared in the current study that perceptions of volitional control over online help-seeking behaviours was not related to the broader construct of locus of control. The convergent validity of the PBC subscale was however supported by a positive relationship with self-efficacy to use the internet (Ajzen, 2002). Convergent validity was supported overall by all subscales demonstrating predicted convergence with at least one measure. Furthermore, the divergent validity of all subscales was supported, with small and non-significant relationships identified as predicted.

Importantly, the eTAP was shown to significantly predict client engagement with e-interventions over a one-week period. Although it was originally predicted that all four TPB constructs would predict engagement, the TPB does assert that intention is the strongest and most proximal predictor of behaviour, with attitudes, subjective norm, and PBC forming the behavioural intention (Ajzen, 1991). That intention was the strongest predictor of engagement behaviours in this study is consistent with the theory. However, a unique pathway from PBC to behaviour was not found, as has been proposed by the TPB (Ajzen, 2002). This relationship warrants further examination in future research, specifically regarding whether this relationship is relevant to understanding individual engagement with e-interventions for mental health. One possible explanation is that PBC may not be have a strong relationship with behavioural intentions for e-interventions, if these interventions are associated with low barriers and high ease of use, as has been argued by proponents of such modalities. However, further research is required to investigate this relationship.

4.1. Limitations

The strengths of the eTAP should be considered in context of a number of limitations in the current study. In order to develop a psychometrically robust measure, COSMIN criteria were used to guide the process of development and validation. However, it should be noted that not all COSMIN domains were assessed in the present study, with responsiveness, criterion, and cultural validity requiring investigation in future research. Furthermore, although preliminary support was found for the structural validity of the eTAP, these results require confirmation in an independent sample. In addition, the sample was predominantly female, which may have created bias in the results and indicate that the scale requires further validation in a more gender balanced sample. However, previous research has demonstrated that females are more likely to participate in research (Chrisler and McCreary, 2010) and use e-interventions (Crisp and Griffiths, 2014). Consequently, having a sample that was predominantly female may be true of the clinical population of interest and not limit the overall generalisability of results. Engagement was also measured via self-reported use, which is likely not as accurate as an objective measure. Due to the heterogeneity of e-interventions used by the current sample, an objective measure of engagement was not possible. However, should the scale be used within a specific e-intervention program in the future, investigations of the scale's capacity to predict objective measures of engagement may be necessary. Lastly, the mean age of the sample was representative of young adults. Although research highlights that this age group is more likely to use e-interventions (Crisp and Griffiths, 2014), and has the highest prevalence of mental health concerns (Slade et al., 2009), some programs have been targeted towards older adults (Zemore and Kaskutas, 2009). It would be useful in future research to examine the capacity of eTAP to predict engagement in e-interventions in both male and older populations, as well as to investigate whether factors associated with adherence differ across the user groups. Despite the limitations of the current study, to the authors' knowledge, the eTAP is the only theoretically based and psychometrically sound instrument to measure factors related to adherence in e-interventions (Wojtowicz et al., 2013; Erdem et al., 2016; Hebert et al., 2010; Schröder et al., 2015).

4.2. Implications

The present study provides further support for the usefulness of the TPB in understanding and predicting health related behaviours. In particular, investigation of the eTAP properties highlights the importance of measuring behavioural intentions as a reliable predictor of future adherence to e-interventions for mental health. Also highlighted in the present study, was that important differences exist in the TPB beliefs associated with F2F and e-interventions for mental health. Although items from the original TAP were modified for inclusion in the eTAP, additional items were also identified through literature searches for specific concerns relating to e-interventions. Six of these additional items (e.g. credibility, technical knowledge) were found to be more relevant to adherence to e-interventions than the modified TAP items, supporting the need for a tailored scale in this area. This finding also demonstrates the importance of therapists and researchers being aware of the unique factors associated with adherence to e-interventions, to be able to best support clients and increase engagement with these services. Indeed, clinicians and researchers may be able to use the eTAP to identify problem areas, such as negative attitudes, poor PBC, and low subjective norms, which may be impacting a client's intention to engage with their interventions (Ajzen, 1985). By identifying and consequently aiming to improve beliefs in these areas, clinicians and researchers may be able to consequently improve and adherence engagement with e-interventions. This is particularly important for clinicians utilising e-interventions as primary methods of treatment (e.g. for clients in geographically isolated areas) or as adjuncts to increase engagement with F2F interventions (Clough and Casey, 2011b).

4.3. Conclusions

This study has provided preliminary support that the eTAP is a reliable and valid measure, with strong theoretical foundations, which can be used to understand and predict client engagement with e-interventions. Specifically, the measure may prove to be useful in identifying clients at risk of disengagement or dropout from e-interventions. Future research should focus on validating the tool in an independent sample and examining the clinical and research uses of the scale in predicting and guiding interventions to improve clients' ongoing engagement with e-interventions.

Appendix A.

Table 8.

Bivariate correlations between the 31 eTAP items.a

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.55⁎⁎ | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ | 0.66⁎⁎ | 0.64⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.20⁎⁎ | 0.67⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | 0.47⁎⁎ |

| 2 | 1.00 | 0.51⁎⁎ | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.72⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.65⁎⁎ | 0.40⁎⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.23⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.72⁎⁎ | 0.50⁎⁎ | |

| 3 | 1.00 | 0.71⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.57⁎⁎ | 0.57⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | 0.56⁎⁎ | 0.64⁎⁎ | 0.22⁎⁎ | 0.57⁎⁎ | 0.61⁎⁎ | 0.51⁎⁎ | 0.63⁎⁎ | ||

| 4 | 1.00 | 0.19⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎ | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.89⁎⁎ | 0.19⁎⁎ | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.88⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.50⁎⁎ | |||

| 5 | 1.00 | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.37⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | 0.15⁎ | 0.54⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.16⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | ||||

| 6 | 1.00 | 0.55⁎⁎ | 0.51⁎⁎ | 0.76⁎⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.55⁎⁎ | 0.40⁎⁎ | 0.77⁎⁎ | 0.59⁎⁎ | |||||

| 7 | 1.00 | 0.77⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.67⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.78⁎⁎ | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.66⁎⁎ | ||||||

| 8 | 1.00 | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.63⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.79⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.58⁎⁎ | |||||||

| 9 | 1.00 | 0.54⁎⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.51⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.85⁎⁎ | 0.55⁎⁎ | ||||||||

| 10 | 1.00 | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.72⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | 0.71⁎⁎ | |||||||||

| 11 | 1.00 | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.92⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | ||||||||||

| 12 | 1.00 | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.19⁎⁎ | 0.37⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | |||||||||||

| 13 | 1.00 | 0.49⁎⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.67⁎⁎ | ||||||||||||

| 14 | 1.00 | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ | |||||||||||||

| 15 | 1.00 | 0.59⁎⁎ | ||||||||||||||

| 16 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 17 | ||||||||||||||||

| 18 | ||||||||||||||||

| 19 | ||||||||||||||||

| 20 | ||||||||||||||||

| 21 | ||||||||||||||||

| 22 | ||||||||||||||||

| 23 | ||||||||||||||||

| 24 | ||||||||||||||||

| 25 | ||||||||||||||||

| 26 | ||||||||||||||||

| 27 | ||||||||||||||||

| 28 | ||||||||||||||||

| 29 | ||||||||||||||||

| 30 | ||||||||||||||||

| 31 | ||||||||||||||||

| M | 5.37 | 5.25 | 4.87 | 4.53 | 5.99 | 4.95 | 5.51 | 5.32 | 5.38 | 5.26 | 4.39 | 6.03 | 5.49 | 4.42 | 5.28 | 5.45 |

| SD | 1.06 | 1.63 | 1.64 | 1.97 | 1.35 | 1.48 | 1.23 | 1.27 | 1.41 | 1.39 | 1.83 | 1.35 | 1.20 | 1.89 | 1.46 | 1.39 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.57⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.70⁎⁎ | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.54⁎⁎ | 0.47⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎ | 0.50⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ |

| 2 | 0.37⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.56⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.54⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.20⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.22⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ |

| 3 | 0.42⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | 0.57⁎⁎ | 0.55⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.56⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎ | 0.23⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ |

| 4 | 0.37⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.68⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.63⁎⁎ | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.22⁎⁎ | 0.60⁎⁎ | 0.37⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ |

| 5 | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.24⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.50⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.15⁎ | 0.09 | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.09 | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.13 | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ |

| 6 | 0.51⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | 0.67⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.63⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ |

| 7 | 0.68⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.79⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.47⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.47⁎⁎ |

| 8 | 0.65⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.77⁎⁎ | 0.23⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.55⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.55⁎⁎ |

| 9 | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | 0.65⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.60⁎⁎ | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.19⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.24⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ |

| 10 | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.57⁎⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.69⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.61⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.37⁎⁎ | 0.51⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ |

| 11 | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.65⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.17⁎ | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.66⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.64⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.24⁎⁎ |

| 12 | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.14⁎ | 0.02 | 0.22⁎⁎ | 0.00 | 0.17⁎⁎ | 0.07 | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ |

| 13 | 0.71⁎⁎ | 0.55⁎⁎ | 0.56⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.85⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | 0.50⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎ | 0.47⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.47⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ |

| 14 | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.69⁎⁎ | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.16⁎ | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.71⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.71⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ |

| 15 | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | 0.65⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.37⁎⁎ | 0.61⁎⁎ | 0.37⁎⁎ | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.37⁎⁎ |

| 16 | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.63⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.56⁎⁎ | 0.64⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.50⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.56⁎⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.47⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.51⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ |

| 17 | 1.00 | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.75⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.51⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.55⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ |

| 18 | 1.00 | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.54⁎⁎ | 0.54⁎⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.20⁎⁎ | 0.50⁎⁎ | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.30⁎⁎ | 0.55⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ | |

| 19 | 1.00 | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.55⁎⁎ | 0.30⁎⁎ | 0.77⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.33⁎⁎ | 0.46⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | ||

| 20 | 1.00 | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.63⁎⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.16⁎ | 0.64⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | |||

| 21 | 1.00 | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.51⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.56⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ | ||||

| 22 | 1.00 | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.16⁎ | 0–0.10 | 0.40⁎⁎ | 0–0.05 | 0.14⁎ | 0.01 | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | |||||

| 23 | 1.00 | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.54⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎ | ||||||

| 24 | 1.00 | 0.47⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.90⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | |||||||

| 25 | 1.00 | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.63⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.37⁎⁎ | ||||||||

| 26 | 1.00 | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.49⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | |||||||||

| 27 | 1.00 | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ | ||||||||||

| 28 | 1.00 | 0.37⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | |||||||||||

| 29 | 1.00 | 0.41⁎⁎ | 0.38⁎⁎ | ||||||||||||

| 30 | 1.00 | 0.46⁎⁎ | |||||||||||||

| 31 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| M | 5.24 | 5.57 | 4.59 | 4.88 | 5.40 | 6.05 | 4.52 | 4.14 | 3.26 | 5.32 | 3.40 | 4.07 | 4.44 | 5.06 | 4.87 |

| SD | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.40 | 1.86 | 1.34 | 1.26 | 1.40 | 1.74 | 1.59 | 1.57 | 1.49 | 1.75 | 1.68 | 1.50 | 1.62 |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

N = 220.

Appendix B. The e-Therapy Attitudes and Process Questionnaire (eTAP)

-

1.

I will use my online intervention for mental health in the next week:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

-

2.

I find online interventions for mental health to be:

| Not helpful | Helpful | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 |

-

3.

Those people who are important to me would approve of me using online interventions for mental health:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

-

4.

I possess the required technical knowledge to use online interventions for mental health:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

-

5.

It is likely that I will use my online intervention for mental health in the next week:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

-

6.

Most people who are important to me would approve of me using online interventions for mental health:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

-

7.

I find using online interventions for mental health to be:

| Harmful | Beneficial | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 |

-

8.

It is mostly up to me whether I use my online intervention for mental health in the next week:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

-

9.

I intend to use my online intervention for mental health in the next week:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

-

10.

I find using online interventions for mental health to be:

| Unpleasant | Pleasant | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 |

-

11.

Those people who are important to me would support me using online interventions for mental health:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

-

12.

I intend to ensure I have access to the required technology to use my online intervention for mental health in the next week:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

-

13.

I have complete control over whether I use online interventions for mental health:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

-

14.

I find online interventions for mental health to be:

| Not credible | Credible | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 |

-

15.

I am confident using the technology for my online intervention for mental health:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

-

16.

Those people who are important to me think online interventions for mental health are credible:

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Scoring:

Att: 2, 7, 10, 14 (all items on this scale are to be rescaled to a 1–7 scale before addition or interpretation).

SN: 3, 6, 11, 16.

Int: 1, 5, 9, 12.

PBC: 4, 8, 13, 15.

References

- Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J., Beckmann J., editors. Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior. Springer; Heidelberg: 1985. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002;32(4):665–683. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. 2006. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Albarracin D. Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2001;127(1):142–161. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apolinário-Hagen J., Vehreschild V., Alkoudmani R.M. Current views and perspectives on E-mental health: an exploratory survey study for understanding public attitudes toward internet-based psychotherapy in Germany. JMIR Ment. Health. 2017;4(1) doi: 10.2196/mental.6375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage C.J., Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001;40(4):471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty L., Binnion C. A systematic review of predictors of and reasons for adherence to online psychological interventions. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2016;23(6):776–794. doi: 10.1007/s12529-016-9556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey L.M., Clough B.A. Making and keeping the connection: improving consumer attitudes and engagement in e-mental health interventions. In: Riva G., Wiederhold W., Cipresso P., editors. The Psychology of Social Networking: Communication, Presence, Identity and Relationships in Online Communities. Versita: Open Access; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Casey L.M., Wright M.-A., Clough B.A. Comparison of perceived barriers and treatment preferences associated with internet-based and face-to-face psychological treatment of depression. Int. J. Cyber Behav. Psychol. Learn. 2014;4(4):16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Catell R.B. The scree test for number of factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1966;1:245–276. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrisler J.C., McCreary D.R. In: Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology Gender Research in General and Experimental Psychology. SpringerLink, editor. Springer New York; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H., Griffiths K.M., Korten A. Web-based cognitive behavior therapy: analysis of site usage and changes in depression and anxiety scores. J. Med. Internet Res. 2002;4(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.4.1.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough B.A., Casey L.M. Technological adjuncts to enhance current psychotherapy practices: a review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011;31(3):279–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough B.A., Casey L.M. Technological adjuncts to increase adherence to therapy: a review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011;31:697–710. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough B.A., Casey L.M. The smart therapist: a look to the future of smartphones and mHealth technologies in psychotherapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2015;46(3):147. p. No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- Clough B.A., Casey L.M. Smart designs for smart technologies: research challenges and emerging solutions for scientist-practitioners within e-mental health. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2015;46(6):429. [Google Scholar]

- Clough B.A., Nazareth S.M., Casey L.M. The therapy attitudes and process questionnaire: a brief measure of factors related to psychotherapy appointment attendance. Patient Patient Cent. Outcomes Res. 2016;10(2):237–250. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough B.A. Going global: do consumer preferences, attitudes, and barriers to using e-mental health services differ across countries? J. Ment. Health. 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2017.1370639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough B.A., Nazareth S.M., Casey L.M. The Therapy Attitudes and Process Questionnaire: a brief measure of factors related to psychotherapy appointment attendance. Patient Patient Cent. Outcomes Res. 2017;10(2):237–250. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp D.A., Griffiths K.M. Participating in online mental health interventions: who is most likely to sign up and why? Depression Research and Treatment. 2014;2014:e790457. doi: 10.1155/2014/790457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vivo M. Examining exercise intention and behaviour during pregnancy using the Theory of Planned Behaviour: a meta-analysis. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2016;34(2):122–138. [Google Scholar]

- Donkin L. A systematic review of the impact of adherence on the effectiveness of e-therapies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e52. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey E.R. The use of smartphones for health research. Acad. Med. 2017;92(2):157–160. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdem A., Bardakci S., Erdem Ş. Receiving online psychological counseling and its causes: a structural equation model. Curr. Psychol. 2016;2016:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar L.R. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Methods. 1999;4(3):272–299. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M., Ajzen I. Psychology Press; New York: 2010. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi A. Attrition and outcome in self-help treatment for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: a constructive replication. Eat. Behav. 2006;7(4):300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S.B. Type I and type II error rates and overall accuracy of the revised parallel analysis method for determining the number of factors. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2015;75(3):428–457. doi: 10.1177/0013164414546566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert E.A. Attrition and adherence in the online treatment of chronic insomnia. Behav. Sleep Med. 2010;8(3):141–150. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2010.487457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce D., Weibelzahl S. Student counseling services: using text messaging to lower barriers to help seeking. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2011;48(3):287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Glassman M. Beyond search and communication: development and validation of the Internet Self-efficacy Scale (ISS) Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013;29(4):1421–1429. [Google Scholar]

- Klein B., Cook S. Preferences for e-mental health services amongst an online Australian sample? Sensoria: A Journal of Mind, Brain & Culture. 2010;6(1):28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kopelowicz A. Using the theory of planned behavior to improve treatment adherence in Mexican Americans with schizophrenia. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015;83(5):985. doi: 10.1037/a0039346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjansson A. Self-generated identification codes in longitudinal prevention research with adolescents: a pilot study of matched and unmatched subjects. Prev. Sci. 2014;15(2):205–212. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0372-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson K. Predicting user intentions: comparing the technology acceptance model with the theory of planned behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991;2(3):173–191. [Google Scholar]

- McEachan R.R.C. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2011;5(2):97–144. [Google Scholar]

- Melville K.M., Casey L.M., Kavanagh D.J. Dropout from Internet-based treatment for psychological disorders. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010;49(4):455–471. doi: 10.1348/014466509X472138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meurk C. Establishing and governing e-mental health care in Australia: a systematic review of challenges and a call for policy-focussed research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016;18(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.4827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink L.B. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010;10(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallant J. 4th ed. Open University Press; Maidenhead, Berkshire: 2010. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS. [Google Scholar]

- Pett M.A., Lackey N.R., Sullivan J.J. Sage Publications, Inc.; USA: 2003. Making Sense of Factor Analysis: The Use of Factor Analysis for Instrument Development in Health Care Research. [Google Scholar]

- Prinsen C.A., Mokkink L.B., Bouter L.M., Alonso J., Patrick D.L., De Vet H.C., Terwee C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018;27(5):1147–1157. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotter J.B. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. 1966;80(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J. Acceptability of online self-help to people with depression: users' views of MoodGYM versus informational websites. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16(3) doi: 10.2196/jmir.2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder J. Development of a questionnaire measuring Attitudes towards Psychological Online Interventions–the APOI. J. Affect. Disord. 2015;187:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P., Aubrey R., Kellett S. Increasing attendance for psychotherapy: implementation intentions and the self-regulation of attendance-related negative affect. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007;75(6):853–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade T. 2007 national survey of mental health and wellbeing: methods and key findings. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2009;43(7):594–605. doi: 10.1080/00048670902970882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B.G., Fidell L.S., Osterlind S.J. 6th ed. Pearson Education; Boston, MA: 2013. Using Multivariate Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel D.L., Wade N.G., Haake S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006;53(3):325. [Google Scholar]

- White K.M. Predicting the consumption of foods low in saturated fats among people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The role of planning in the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite. 2010;55(2):348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White M.M., Clough B.A., Casey L.M. What do help-seeking measures assess? Building a conceptualization framework for help-seeking intentions through a systematic review of measure content. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017;59:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C.J. Measuring help-seeking intentions: properties of the general help-seeking questionnaire. Can. J. Couns. 2005;39(1):15. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtowicz M., Day V., McGrath P.J. Predictors of participant retention in a guided online self-help program for university students: prospective cohort study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013;15(5) doi: 10.2196/jmir.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore S.E., Kaskutas L.A. Development and validation of the alcoholics anonymous intention measure (AAIM) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104(3):204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet G.D. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]