Abstract

Depression is one of the most prevalent mental health disorders and is estimated to become the leading cause of disability worldwide by 2030. Increasing access to effective treatment for depression is a major societal challenge. In this context, the increasing use of computers in the form of laptops or smartphones has made it feasible to increase access to mental healthcare through digital technology. In this study, we examined the effectiveness of a 14-week therapist-guided Internet-delivered program for patients with major depression undergoing routine care. From 2015 to 2018, 105 patients were included in the study. For depressive symptoms, we identified significant within-group effect sizes (post-treatment: d = 0.96; 6-month follow-up: d = 1.21). We also found significant effects on secondary anxiety and insomnia symptoms (d = 0.55–0.92). Clinically reliable improvement was reported by 48% of those undergoing the main parts of the treatment, whereas 5% of the participants reported a clinically significant deterioration. However, a large proportion of patients showed no clinically reliable change. In summary, the study identified large treatment effects, but also highlighted room for improvement in the usability of the treatment.

Keywords: Depression, Guided Internet-delivered treatment, Implementation, Cognitive behavioural therapy, Effectiveness

Highlights

-

•

The effectiveness of guided ICBT for 105 patients with major depression in secondary routine care

-

•

Large within-group effect sizes were identified at post-treatment and follow-up for primary symptoms

-

•

Moderate within-group effect sizes were identified at post-treatment and follow-up for anxiety and insomnia symptoms.

-

•

At an individual level, 48% of those who completed the main parts of the treatment had clinically reliable change

1. Introduction

Depression is one of the most prevalent mental health disorders and is estimated to be the leading cause of disability worldwide by 2030 (WHO, 2017). Every fourth person experiences major depression during their lifetime, and the disorder has major individual, societal, and economic consequences. However, access to treatment remains low, with only 20% of the patients receiving adequate care (Torvik et al., 2018; Ebmeier et al., 2006).

Increasing access to effective treatment for depression is a major societal challenge. In this context, the growing use of computers in the form of laptops or smartphones by most people on a daily basis has made it feasible to increase access to mental healthcare through the use of technology. Therapist-guided Internet-delivered treatments for depression have been extensively researched over the last 20 years (Andersson, 2018), and the findings of efficacy trials have been summarised in several meta-analyses (Andersson et al., in press). In a recently published meta-analysis of individual participant data for the effects of guided Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural treatment (ICBT) for depression, the findings from 24 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) including almost 5000 patients were reported (Karyotaki et al., 2018). This sample included a high proportion of college/university-educated individuals (65%), and the pooled response rate was 56% and remission rate was 39%. In trials directly comparing guided ICBT and face-to-face therapy for depression, two modes of delivery did not show any significant differences (Andersson et al., 2016). The negative effects of guided ICBT have been summarised in a meta-analysis of 18 studies with a total of 2079 participants (Ebert et al., 2016), which showed deterioration in 5%–10% of the patients, with lower education levels being associated with higher deterioration rates (Ebert et al., 2016).

The progression from documented effects in efficacy trials to implementation and effectiveness in routine care represents a major challenge in healthcare services (Shafran et al., 2009). One effectiveness trial illustrates this challenge (Littlewood et al., 2015). In that trial, suboptimal implementation of therapist guidance, with General Practitioners (GPs) offering guidance on an irregular basis, in ICBT for depression was a plausible explanation for the reported poor and atypical effects. However, examples of successful implementation of guided ICBT in routine care have also been reported (Titov et al., 2018). In the Internet Psychiatry Clinic in Sweden, guided Internet-delivered treatment from a self-recruited sample in routine care (N = 1203) showed large treatment effects (Hedman et al., 2014). However, one limitation of this study was a large attrition rate at the six-month follow-up (63%). In a recently published study from Denmark (Mathiasen et al., 2018), guided ICBT for 60 adults with depression showed a large within-group effect size (d = 1.10), with 62% completing the main parts (5 of 6 mandatory modules) of the treatment. In that study, higher education levels and more time spent in the program predicted improved outcomes. A benchmarking study for guided ICBT for depression was undertaken by our group in order to study the effects after disseminating the treatment from Sweden to Norway (Jakobsen et al., 2017). Large effects were identified and results comparable to those of the Swedish studies were reported. However, the evidence for guided ICBT as a part of routine care with a GP-referred sample is still scarce, and more documentation of its effectiveness is needed. In the present trial, we report the effectiveness data of guided ICBT in routine care for adults with depression from the point of implementation and the subsequent three years.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

Since 2015, the eCoping (eMeistring.no) clinic at Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, has offered guided ICBT for major depression (Jakobsen et al., 2017) in a routine mental health outpatient care setting. In order to receive treatment at the hospital, patients require having significant and severe impairments due to their psychiatric disorder.

Overall, during 2018, 352 patients were referred to the clinic for all available Internet-delivered treatments (depression, social anxiety disorder and panic disorder), and 91.5% of the referrals were offered treatment. Of these, 80% signed informed consent forms. This article will cover all depression patients included between 2015 and 2018.

The clinic is part of the Division of Psychiatry, Haukeland University Hospital, Norway. The catchment area of the hospital includes 300,000 persons and consists of four mental health outpatient clinics. The Western Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway approved the present study (2015/878).

2.2. Design

We present an open effectiveness study with a naturalistic within-group design with repeated assessments for primary and secondary treatment outcomes and a 6-month follow-up.

2.3. Procedure

Patients were either referred to the psychiatric clinic by their GP or another psychiatric clinic or contacted the clinic directly. A face-to-face assessment was conducted at the clinic and included a structured diagnostic evaluation with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998) and questions regarding treatment history and background factors. The patients were informed about the ICBT during the assessment meeting. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a major depressive episode and major depression as the main problem according to the MINI, (2) 18 years of age or older, (3) not using benzodiazepines on a daily basis, (4) if using antidepressants, receiving a stable dosage over the previous four weeks, and (5) able to read and write in Norwegian. The exclusion criteria were (1) current suicidal ideation, (2) current psychosis, (3) current substance abuse, (4) in immediate need of other treatment (e.g. to address complex comorbidities), and (5) no access to the Internet. Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were interested in starting guided ICBT for depression were invited to participate in the current study. All included participants signed a written informed consent form.

2.4. Treatment

The depression ICBT program in this study was based on a program originally developed and tested in a randomised controlled trial by Andersson and colleagues (e.g. Andersson et al., 2005). The program was translated into Norwegian and tested in a benchmarking trial (Jakobsen et al., 2017). After further amendments, the program was implemented at the eMeistring clinic and has been offered as part of routine care since 2015.

The guided ICBT program for depression consists of eight text-based modules, or chapters, which are provided online. The program includes state-of the art components of CBT for depression: psychoeducation, behavioural activation, and cognitive reappraisal. A more detailed overview of the content in each module can be found in Table 1. Treatment time was set to 14 weeks, and the patients were expected to spend 7–10 days per module. This is a longer timeframe than that used in the original studies, but it was considered acceptable in this context since many referred patients had complex and long-lasting psychiatric disorders; this timeframe in line with the existing practices among therapists. After each completed module, a therapist gave feedback and guidance on the work done by the patient and then introduced the patient to the next module, all of which was performed asynchronously in the secure digital platform. For more extensive information about this type of Internet-delivered treatment, please refer to the book on the subject by Andersson (2015). Each patient had the same therapist throughout the treatment. If the patient was not heard from for one week, the therapist contacted the patient via a secure message and mobile phone text message to encourage the patient to continue with the work. If necessary, phone calls could be made to solve problems, discuss motivation, or simply get in touch with an inactive patient.

Table 1.

Content of the treatment modules and homework assignments.

| Content | Main homework assignments | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Psychoeducation on cognitive behaviour therapy and the depression diagnosis. | Setting goals for the treatment. Answering questions about motivation for the treatment and hopes and fears about the treatment. |

| 2 | Introducing the rationale for behavioural activation. Discussing the aetiology of depression. | Filling out one week of planned activities and marking activities with + or -. Answering questions about personal background related to the depression, mood-lowering situations, and reflections on the activity planning. Following up on treatment goals. |

| 3 | Psychoeducation for short- and long-term positive activities. Introducing the value compass as a guide to choosing activities. How to handle activities that are negatively reinforced but have long-term positive effects (like exercise or cleaning). | Filling out a value compass. Making a list of short- and long-term positive activities they wish to increase and a list of negative activities they wish to reduce. Activity planning. Answering questions about activity planning. Following up on treatment goals. |

| 4 | Psychoeducation on negative activities: avoidance behaviours and punishing activities. Behavioural activation: problem-solving and reward planning. | Activity planning to reduce the number of negative activities and replace them with positive activities. Making a list of rewards. Drawing up a behavioural activation contract including rewards. Answering questions about the behavioural activation. |

| 5 | Psychoeducation about depressive thinking and rumination. Introducing a behavioural approach to negative thoughts. Introducing a problem-solving method. Introducing techniques for shifting focus and being mindful in the execution of positive activities. | Registering negative thoughts in relation to situation, behaviour, and consequences. Challenging negative thoughts by choosing a different behaviour and evaluating the consequences. Answering questions about negative thoughts and alternative behaviours. |

| 6 | Introducing approaches to defuse negative thoughts in order to accept and shift focus towards valued activities, e.g. defining negative terms and etiquettes, nuancing statements. | Registering negative thoughts and using defusion strategies. Answering questions about negative thinking, thought defusion strategies, and situations associated with negative thinking. |

| 7 | Psychoeducation about sleep and its relation to depression. Introducing sleep hygiene, sleep diary, scheduled sleep, sleep restriction, stimulus control and relaxation techniques. | Registering sleep hygiene factors and planned changes. Sleep diary registration. Choosing and starting relevant sleep improvement strategies. Answering questions about sleep history and chosen sleep strategies. |

| 8 | Summary of modules 1–7. Preparing for setbacks and preventing relapse. Planning the future work with the treatment methods. | Registering the most important and effective strategies from each module. Following up on treatment goals. Answering questions about learnings, goal achievement, plans for the future. |

2.5. Therapists

The therapists were licensed healthcare staff: psychologists, registered nurses, a clinical social worker, and a psychiatrist. Their role was to monitor progress, address problems, and give therapeutic feedback. The majority of therapists had received one year of training in guided ICBT (10 days), which included general knowledge and training in CBT principles, diagnosis-specific considerations, and training for role of an e-therapist. The therapists underwent weekly supervision by a specialist psychologist.

2.6. Measures

All measures were administered via the Internet. Online measures have been found to yield equivalent psychometric properties to those of paper- and pencil measures (van Ballegooijen et al., 2016).

2.6.1. Primary outcome

The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale-Self report (MADRS-S; Svanborg and Asberg, 1994) measures depression severity using nine items scored 0 to 6, with answer alternatives varying between items. The total score ranges from 0 to 54. Pre-treatment Cronbach's alpha for the study sample was 0.85. MADRS-S shows good psychometric properties in other samples as well (Thorndike et al., 2009), and is sensitive to change (Svanborg and Ekselius, 2003). MADRS-S assessment was performed pre-treatment, seven times throughout the treatment at the opening of a new module, post-treatment, and at the 6-month follow-up.

2.6.2. Secondary outcomes

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002) measures depression severity with nine items scored 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”), corresponding to the criteria for major depression in the DSM-5. The sum of the scores for the nine items ranges from 0 to 27. Pre-treatment Cronbach's alpha for the study sample was 0.77. The scale has shown good psychometric properties in other samples as well, and is sensitive to change (Löwe et al., 2004; Titov et al., 2011). PHQ-9 assessments were performed pre-treatment, post-treatment, and at the 6-month follow-up.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006) measures anxiety severity with seven items scored 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”). The total score ranges from 0 to 21. Pre-treatment Cronbach's alpha for the study sample was 0.87. GAD-7 shows good psychometric properties in other samples as well, and has sufficient sensitivity to detect the presence of anxiety disorders (Kroenke et al., 2007; Dear et al., 2011). GAD-7 assessments were performed pre-treatment, post-treatment, and at the 6-month follow-up.

The Bergen Insomnia Scale (BIS; Pallesen et al., 2008) measures insomnia severity with six items. Each item is scored from 0 to 7, representing the average number of days per week the participant presented with sleep difficulties in the previous month, and the sum of the scores thus ranges from 0 to 42. The pre-treatment Cronbach's alpha for the study sample was 0.82. The BIS has demonstrated good psychometric properties in other samples as well (Pallesen et al., 2008). BIS assessments were distributed pre-treatment, post-treatment, and at the 6-month follow-up.

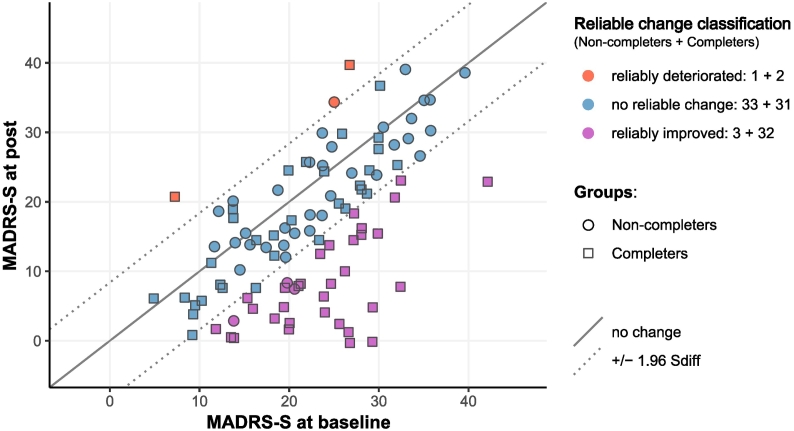

2.7. Clinically reliable change at an individual level post-treatment

Individual-level changes at the post-treatment assessment were calculated using the observed data for patients who underwent two or more assessments (N = 102), with the last observed data point up to and including the post-treatment assessment serving as the post-data. Participants were considered to have shown an improvement if they showed a clinically reliable change on MADRS-S, as defined by the Reliable Change Index (RCI; Jacobson and Truax, 1991). The RCI was calculated with the formula 1.96*(SD1*√2*√(1-rel)), where SD1 is the observed standard deviation at the pre-treatment assessment (7.9), and rel is the pre-treatment reliability (0.85; Martinovich et al., 1996). Clinically reliable change was thus found to require a reduction of 8.5 points or more on MADRS-S. Deterioration was defined by the presence of a negative clinically reliable change.

2.8. Statistical analyses

Intent-to-treat analyses of the treatment outcome from pre- to post-treatment and follow-up were performed using linear mixed modelling, which is a recommended statistical method for handling missing data and uses all available data for estimation of the outcomes (Gueorguieva and Krystal, 2004; Hesser, 2015). The primary outcome measure MADRS-S was assessed at the opening of each module during the treatment, which means that for that measure, the mixed model used up to 10 data points (pre-treatment, seven measures activated at the opening of each new module, post-treatment, and the 6-month follow-up). The model that best fit the data consisted of a linear and quadratic function of time, using random intercept and slope. To assess the changes between post-treatment assessment and the 6-month follow-up, we performed a separate analysis with these two measurement points and a linear function of time, random intercept, and slope. Since the patients missing from the 6-month follow-up were significantly younger than those whose data were available (see Results), a sensitivity analysis was performed with age as a covariate in the post-treatment to 6-month follow-up model for the primary outcome. For PHQ-9, GAD-7, and BIS, three data points were used (pre- and post-treatment and 6-month follow-up).

Within-group effect sizes were calculated as Cohen's d values by using the estimated means for the pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 6-month follow-up data. The estimated pre-treatment SD (Standard Error*√N) was used as σ. Comparisons between participants who underwent the 6-month follow-up and those who did not were performed using t-tests and χ2 associations. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp., Released 2016).

3. Results

3.1. Participants

A total of 105 participants were included in the study between September 2015 and April 2018. All included participants had consented to participation in the study, filled out the pre-treatment measures, and had accessed at least one treatment module. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics.

| n/N, mean | %/SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 61/105 | 58% | |

| Age | 35 | 12 | 19–71 |

| Higher educationa | 51/105 | 48% | |

| Married/cohabiting | 59/105 | 56% | |

| Has children | 42/105 | 40% | |

| MADRS-S mean score at baseline | 22.32 | 7.93 | |

| Years with complaints of depression | 8 | 9 | 0–46 |

| Used antidepressants sometime during the treatment period | 20/73b | 27% |

Note. N = sample size for that measure, n = number of participants with the specified characteristic, SD = standard deviation, MADRS-S = Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Self-rated.

College or university level.

73 participants provided medication data collected post-treatment.

3.2. Attrition and adherence

Seventy-four participants (70%) completed the post-treatment measurements, and 47 (45%) completed the 6-month follow-up. We followed the routine care practice of not providing prompts for information after completion or termination of treatment, except one text message asking patients to fill out the 6-month follow-up questionnaires. The primary measure MADRS-S was assessed at the opening of a new module, and the average number of MADRS-S forms filled out online during treatment, including pre- and post-assessments, was 6.6 (SD, 2.7). The participants were given access to an average of 5.7 modules (SD, 2.5) out of 8 during the treatment period. Sixty-five participants (62%) received access to the main part of the treatment, i.e. at least five of the eight modules.

When comparing the participants who provided data at the 6-month follow-up to those who did not, the following findings were obtained: participants who provided 6-month data were significantly older than those who did not (t (103) = 2.1, p = .04), and the mean age for those who provided data was 38 years (SD, 13) while it was 33 years (SD, 10) for those who did not provide data. There was no significant difference in pre-treatment MADRS-S scores (t (103) = −1,9, p = .06). The mean score for data providers was 20 (SD, 7), while it was 24 for those who did not provide data (SD, 8); there were no differences related to gender (χ2 = 0.4, p = .50).

3.3. Primary outcome

The MADRS-S score was the primary outcome in this study. The mixed-model analyses showed statistically significant individual variations at baseline (intercept p < .001). The mean reduction from pre- to post-treatment was 7.62 points (df = 650, F = 140, p < .001), and the reduction from pre-treatment to the 6-month follow-up was 9.65 points (df = 660, F = 137, p < .001) (see Table 3). The change from post-treatment to the 6-month follow-up was not significant (p = .18). Sensitivity analysis from post-treatment to the 6-month follow-up including age as a covariate did not change the result in a significant manner (p = .19). The estimated mean values, confidence intervals, and effect sizes are presented in Table 3. Almost half (48%) of the patients who completed the main parts of the treatment showed clinically reliable change at the post-treatment assessment. Among those who did not complete the main parts of the treatment, only 16% showed clinical improvement post-treatment (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Estimated mean values and effect sizes.

| Pre Mean (SD) [95% CI] |

Post Mean (SD) [95% CI] |

FU6 Mean (SD) [95% CI] |

Effect size pre-post | Effect size pre-FU6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MADRS-S | 22.15 (7.96) [20.61–23.69] |

14.53 (8.31) [12.93–16.14] |

12.50 (10.85) [10.42–14.59] |

0.96 | 1.21 |

| PHQ-9 | 15.12 (5.20) [14.12–16.13] |

10.33 (6.14) [9.15–11.52] |

9.31 (7.69) [7.83–10.79] |

0.92 | 1.11 |

| GAD-7 | 9.89 (4.22) [9.07–10.70] |

7.43 (4.82) [6.50–8.35] |

6.01 (5.53) [4.94–7.08] |

0.58 | 0.92 |

| BIS | 21.45 (9.70) [19.58–23.32] |

16.10 (10.90) [13.99–18.20] |

13.54 (13.04) [11.02–16.05] |

0.55 | 0.82 |

Note. MADRS-S = Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale-self report, PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire, GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale, BIS = Bergen Insomnia Scale, CI = confidence interval, SD = standard deviation, Pre = pre-treatment, Post = post-treatment, FU6 = 6-month follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Note. Reliable changes on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale-Self report (MADRS-S) for the non-completers (n = 37) and the completers (n = 65).

3.4. Secondary outcomes

The mixed-model analyses of the secondary outcome measures PHQ-9, GAD-7, and BIS all showed significant improvements from pre-treatment to post-treatment, as well as from pre-treatment to the 6-month follow-up (p-values, .03 for BIS and <.001 for the others). Estimated mean values, standard deviations, confidence intervals, and effect sizes are presented in Table 3.

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined the effectiveness of guided ICBT for adults with major depression in a routine mental healthcare service, with data collected during initial implementation and the following three years. All patients who visited the clinic in this period were invited to participate in this study. A total of 105 patients were eligible and accepted the invitation to participate in the study. Our sample consisted of a majority of women, with 48% having a higher education and the first depressive episode being reported an average of 9 years previously.

Significant group-level positive changes were reported, with a large within-group effect size on the primary outcome MADRS-SR observed post-treatment and at the 6-month follow-up (ES = 0.96–1.21). Moderate to large effect sizes were also reported for the secondary outcomes, including insomnia and anxiety symptoms post-treatment and at the 6-month follow-up (ES = 0.55–1.11). A total of 70% of the participants completed the post-assessment. These effects are comparable to the results of earlier efficacy studies of guided ICBT for depression (Andersson et al., 2005; Vernmark et al., 2010; Johansson and Andersson, 2012; Andersson et al., 2013) and a previous benchmarking study (Jakobsen et al., 2017). These effects are also comparable to those obtained in recent effectiveness studies. In Denmark (Mathiasen et al., 2018) large effects (d = 1.0) were reported for 60 patients with depression receiving guided ICBT with a completion rate of 62%. From a study conducted during routine care in Sweden (Hedman et al., 2014) in a sample of 1203 participants, large effects and a 75% completion rate were reported.

In routine mental healthcare services, an increasing number of patients are presenting with comorbid disorders. The present study suggests that diagnosis-specific depression ICBT treatment is also effective for comorbid anxiety and insomnia symptoms (ES = 0.55–0.92). This supports the notion that comorbid symptoms may decrease as an effect of diagnosis-specific treatment for the primary disorder (Titov et al., 2009).

On an individual level, 48% of those who completed the main parts of the treatment showed clinically reliable improvement. This is slightly lower than the 56% treatment response rate reported in a meta-analysis of individual participant data (Karyotaki et al., 2018), but similar to the findings in the Swedish effectiveness trial (Hedman et al., 2014). It is also lower than the 65% and 56% response rates reported from previous effectiveness trials on guided ICBT for panic disorder and social anxiety disorder from the same setting the present trial was carried out in Nordgreen et al., 2018a, Nordgreen et al., 2018b. Furthermore, a total of 46% of the participants who received treatment did not show any positive or negative clinically reliable change. This is considerably higher than the average non-responder rate of 27% reported across 29 clinical trials for ICBT (N = 2866; Rozental et al., 2019). This is also higher than the findings in previous trials from the same setting on guided ICBT for panic disorder and social anxiety disorder (Nordgreen et al., 2018a, Nordgreen et al., 2018b). In assessments of deterioration, five out of 102 patients (5%) reported a clinically reliable worsening of their symptoms in the course of the treatment, and the treatment was terminated early for one of these patients. This proportion of patients showing deterioration was similar to the average of 5.8% found across 29 studies including 2866 participants (Rozental et al., 2019).

The findings in this effectiveness trial indicate large effect sizes. However, the majority of patients did not show a clinically reliable change. This may be attributed to our implementation strategy of offering treatment initiation to most patients (92% in 2018) who sought treatment. This strategy is based on the lack of predictors for treatment success, which otherwise would have guided our inclusion or exclusion criteria. However, since depression is a multidimensional disorder with different core features across different patients, the present behaviour-oriented treatment (i.e. behaviour activation) may not meet the expectations of many patients who seek a more supportive-, or cognitive-oriented treatment in routine care. These findings may also be attributed to fact that the program was perceived by therapists and patients to be too text-heavy with low interactivity and usability and that the timeframe was 14 and not 12 weeks as in the original studies. As noted by Rozental et al. (2019), differences in definitions, settings, and calculations make it difficult to reliably compare changes across studies. For example, the Karyotaki et al. (2018) study imputed missing data to calculate treatment response at an individual level post-treatment, whereas we used the last available observed data for each individual patient in our calculations of clinically reliable change. However, the differences in patient characteristics and healthcare settings may also explain some of the differences between treatment responders in the current trial and previous trials. First, in comparison to previous trials of ICBT for depression (Karyotaki et al., 2018), the present study included a lower proportion of participants who had received education after high school (48% vs 65%). Second, the patients in this sample were referred for any psychiatric treatment, not specifically guided ICBT, whereas the Swedish Internet Psychiatry Clinic had patients specifically seeking Internet-delivered treatment. Moreover, all patients in the present setting were required to have significant impairment due to their psychiatric disorder in order to receive treatment at this secondary care level. Finally, this sample included data from the start of the implementation of guided ICBT for depression. Taken together, these aspects may indicate a suboptimal implementation of guided ICBT in this setting.

4.1. Implications

Since 2009, the national guidelines for treating mild and moderate depression in Norway have recommended ICBT for depression, exemplified by MoodGym (https://moodgym.anu.edu.au/welcome) (The Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2009). However, the treatment presented in this trial is the first guided ICBT program implemented as routine care in mental healthcare services in Norway that fulfils the clinical guidelines for mild and moderate depression.

The results indicate large group-level effects in line with the findings of previous trials. However, the proportion of patients not completing the main parts of the intervention is somewhat higher than those in previous trials, and consequently, the proportion of patients showing clinically reliable change is somewhat lower than that in previous trials. The individual-level results may be improved by updating the treatment content and increasing the usability of the software to provide a stronger focus on timeframe and completion rates from the beginning of the treatment. In addition, assessing therapist fidelity to guidelines for delivering therapist-assisted ICBT could be beneficial (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2018). Finally, facilitating self-referral is important, as self-referral is associated with improved outcomes (Haug et al., 2012).

4.2. Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is the fact that it reports results from an effectiveness trial conducted as part of routine care where multiple treatments are offered and where the patients are GP-referred. Moreover, this study reports findings for guided ICBT in a sample with lower levels of education compared to other similar studies. Another strength is the relatively large sample size.

The main limitation of this study was the lack of a control group. This is a significant limitation as depression is a disorder characterised by fluctuations and does not show a more stable and chronic course as seen in anxiety disorders such as social anxiety disorder (Posternak and Miller, 2001). However, in order to study the treatment effects of guided ICBT for depression in a naturalistic setting, as presented in the present study, randomisation is not a practically feasible approach. Another limitation is the large attrition at follow-up, since only 45% of the patients completed the 6-month follow-up assessment. This may be explained by the fact that the naturalistic setting does not allow individual prompts when collecting 6-month follow-up data since no study personnel is part of the routine care clinic.

5. Conclusion

This effectiveness study of therapist-guided ICBT for depression showed large treatment effects on depressive symptoms and moderate to large effects on the comorbid symptoms of anxiety and insomnia. More than half of the patients did not show a clinically reliable change. This indicates room for improvement of the usability of the treatment. However, we conclude that our results support the use of therapist-guided ICBT for depression in routine psychiatric care.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The implementation of internet-based treatment for depression at Haukeland University Hospital has been funded by the Western Norway Regional Health Authority (911826), Directorate of Health (11/6252), and Haukeland University Hospital. This publication is part of the INTROducing Mental health through Adaptive Technology (INTROMAT) project, funded by the Norwegian Research Council (259.293/o70).

Declaration of competing interest

Andersson royalties for a self-help book based on a major part of the treatment material used in the Internet treatment. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The research and implementation of Internet-based treatment for major depressive disorder at Haukeland University Hospital has been funded by the Western Norway Regional Health Authority, Directorate of Health, and Haukeland University Hospital.

Grant-awarding bodies

The Western Norway Regional Health Authority.

References

- Andersson G. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2015. The Internet and CBT: A Clinical Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G. Internet interventions: past, present and future. Internet Interv. 2018;12:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Bergström J., Hollandare F., Carlbring P., Kaldo V., Ekselius L. Internet-based self-help for depression: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2005;187:456–461. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.5.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Hesser H., Hummerdal D., Bergman-Nordgren L., Carlbring P. A 3.5-year follow-up of Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy formajor depression. J. Ment. Health. 2013;22:155–164. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.608747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Topooco N., Havik O.E., Nordgreen T. Internet-supported versus face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for depression. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2016;16:55–60. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2015.1125783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Carlbring P., Titov N., Lindefors N. Internet interventions for adults with anxiety and mood disorders: a narrative umbrella review of recent meta-analyses. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2019;64(7):465–470. doi: 10.1177/0706743719839381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ballegooijen W., Riper H., Cuijpers P., van Oppen P., Smit J.H. Validation of online psychometric instruments for common mental health disorders: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:45. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0735-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear B.F., Titov N., Sunderland M., McMillan D., Anderson T., Lorian C., Robinson E. Psychometric comparison of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for measuring response during treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2011;40:216–227. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.582138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D.D., Donkin L., Andersson G., Andrews G., Berger T., Carlbring P.…Cuijpers P. Does Internet-based guided-self-help for depression cause harm? An individual participant data meta-analysis on deterioration rates and its moderators in randomized controlled trials. Psychol. Med. 2016;46:2679–2693. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebmeier K.P. Recent developments and current controversies in depression. Lancet. 2006;367:153–167. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67964-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueorguieva R., Krystal J.H. Move over ANOVA - progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the archives of general psychiatry. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004;61:310–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos H.D. Development and evaluation of a scale assessing therapist fidelity to guidelines for delivering therapist-assisted Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018;47:447–461. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2018.1457079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug T., Nordgreen t., Ost L.G., Havik O.E. Self-help treatment of anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of effects and potential moderators. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2012;32:425–445. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman E., Ljotsson B., Kaldo V., Hesser H., El Alaoui S., Kraepelien M.…Lindefors N. Effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for depression in routine psychiatric care. J. Affect. Disord. 2014;155:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesser H. Modeling individual differences in randomized experiments using growth models: recommendations for design, statistical analysis and reporting of results of internet interventions. Internet Interv. 2015;2:110–120. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp . IBM Corp; Armonk, NY, USA: Released 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N.S., Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991;59:12. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen H., Andersson G., Havik O.E., Nordgreen T. Guided Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for mild and moderate depression: a benchmarking study. Internet Interv. 2017;7:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson R., Andersson G. Internet-based psychological treatments for depression. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2012;12:861–870. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karyotaki E., Ebert D.D., Donkin L., Riper H., Twisk J., Burger S.…Cuijpers P. Do guided internet-based interventions result in clinically relevant changes for patients with depression? An individual participant data meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018;63:80–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002;32:509–515. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B., Monahan P.O., Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlewood E., Duarte A., Hewitt C., Knowles S., Palmer S., Walker S.…Team R. A randomised controlled trial of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for the treatment of depression in primary care: the Randomised Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Acceptability of Computerised Therapy (REEACT) trial. Health Technol. Assess. 2015;19 doi: 10.3310/hta191010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe B., Kroenke K., Herzog W., Gräfe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) J. Affect. Disord. 2004;81:61–66. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinovich Z., Saunders S., Howard K. Some comments on “Assessing clinical significance”. Psychother. Res. 1996;6:124–132. doi: 10.1080/10503309612331331648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiasen K., Riper H., Andersen T.E., Roessler K.K. Guided Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for adult depression and anxiety in routine secondary care: observational study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20 doi: 10.2196/10927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordgreen T., Gjestad R., Andersson G., Carlbring P., Havik O.E. The implementation of guided Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder in a routine-care setting: effectiveness and implementation efforts. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018;47:62–75. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2017.1348389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordgreen T., Gjestad R., Andersson G., Carlbring P., Havik O.E. The effectiveness of guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder in a routine care setting. Internet Interv. 2018;13:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallesen S., Bjorvatn B., Nordhus I.H., Siversten B., Hjørnevik M. A new scale for measuring insomnia: the Bergen insomnia scale. Percept. Mot. Skills. 2008;107:691–706. doi: 10.2466/pms.107.3.691-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posternak M.A., Miller I. Untreated short-term course of major depression: a meta-analysis of outcomes from studies using wait-list control groups. J. Affect. Disord. 2001;66:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental A., Andersson G., Carlbring P. In the absence of effects: an individual patient data meta-analysis of non-response and its predictors in Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy. Front. Psychol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafran, R., Clark, D. M., Fairburn, C. G., Arntz, A., Barlow, D. H., Ehlers, A., … J.M.G., W. (2009). Mind the gap: improving the dissemination of CBT. Behav. Res. Ther., 47, 902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K.H., Amorim P., Janavs J., Weiller E.…Dunbar G.C. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl. 20):22–33. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1998-03251-004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder - the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svanborg P., Asberg M. A new self-rating scale for depression and anxiety states based on the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1994;89:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svanborg P., Ekselius L. Self-assessment of DSM-IV criteria for major depression in psychiatric out- and inpatients. Nord. J. Psychiatry. 2003;57:291–296. doi: 10.1080/08039480307281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2009: Nasjonale retningslinjer for diagnostisering og behandling av voksne med depresjon i primær og spesialisthelsetjenesten (2009). ISBN-nr. 978-82-8081-184-4.

- Thorndike F.P., Carlbring P., Smyth F.L., Magee J.C., Gonder-Frederick L., Ost L.G., Ritterband L.M. Web-based measurement: effect of completing single or multiple items per webpage. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009;25:393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Gibson M., Andrews G., McEvoy P. Internet treatment for social phobia reduces comorbidity. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2009;43:754–759. doi: 10.1080/00048670903001992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Dear B.F., McMillan D., Anderson T., Zou J., Sunderland M. Psychometric comparison of the PHQ-9 and BDI-II for measuring response during treatment of depression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2011;40:126–136. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2010.550059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Dear B., Nielssen O., Staples L., Hadjistavropoulos H., Nugent M.…Kaldo V. ICBT in routine care: a descriptive analysis of successful clinics in five countries. Internet Interv. 2018;13:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torvik F.A., Ystrom E., Gustavson K., Rosenström T.H., Bramness J.G., Gillespie N., Aggen S.H., Kendler K.S., Reichborn-Kjennerud T. Diagnostic and genetic overlap of three common mental disorders in structured interviews and health registries. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018;137:54–64. doi: 10.1111/acps.12829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernmark K., Lenndin J., Bjärehed J., Carlsson M., Karlsson J., Öberg J.…Andersson G. Internet administered guided self-help versus individualized e-mail therapy: a randomized trial of two versions of CBT for major depression. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010;48:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates.https://www-who-nt.ezp.sub.su.se/mental_health/management/depression/prevalence_global_health_estimates/en/ [Google Scholar]