Abstract

Recurrent shoulder instability complicated by capsular insufficiency due to underlying soft-tissue disorders or multiple prior failed surgical procedures poses a challenging surgical problem. Traditional capsulolabral soft-tissue reconstruction techniques are less effective in this setting, and bony procedures sacrifice normal anatomic relations. The described arthroscopic technique aims to prevent instability while maintaining range of motion through creation of a soft-tissue allograft “sling” augmenting the posterior glenohumeral capsule.

Surgical techniques for addressing recurrent shoulder instability can be divided into 2 categories: anatomic and nonanatomic. Anatomic techniques include various anterior and posterior capsulolabral repair and capsulorrhaphy or capsular shift procedures.1 Current literature shows that arthroscopic Bankart repair techniques have equivalent outcomes to open techniques.2

Nonanatomic techniques include various coracoid process transfer procedures, such as the Bristow-Latarjet procedure.3, 4 This is most commonly performed as an open procedure, but arthroscopic techniques have also been described with equivalent mid-term outcomes.5, 6 Long-term studies have suggested that the primary Latarjet procedure may have superior outcomes to arthroscopic Bankart repair.7 Despite the advantages, nonanatomic bony augmentation procedures can be more invasive and make further revision surgery still more difficult because of alteration of normal anatomic structures and relations.8

In cases in which bony defects exist but coracoid transfer is not preferred or not possible, other techniques to address glenoid bone loss include iliac crest autograft reconstruction9 or distal tibial allograft reconstruction.10, 11 Techniques to address humeral head bone loss, such as a Hills-Sachs lesion, include osteochondral allograft transplantation12, 13 or remplissage procedures.14

In cases in which the bony anatomy is normal, instability is attributable to a soft-tissue problem. Capsular insufficiency in these patients may be a result of multiple prior failed surgical procedures; underlying soft-tissue disorders, such as type III Ehlers-Danlos syndrome1; and historically, thermal capsulorrhaphy with resultant tissue necrosis.15 Often, underlying collagen disorders are undiagnosed. In difficult revision surgical stabilization attempts, results are compromised by this multitude of factors.16

In patients with generalized tissue laxity, it is logical that allograft reconstructions would be more durable than procedures relying on the patients' native tissue, which may be compromised by underlying collagen abnormalities or disorders.16 With this in mind, an arthroscopic technique using allograft augmentation was developed to treat multidirectional instability in patients with capsular insufficiency. The technique described here uses gracilis tendon allograft to reconstruct the posterior capsuloligamentous structures, creating a “sling” to prevent recurrent instability while maintaining range of motion (ROM). It is recommended in cases of recurrent multidirectional instability in which there is capsular insufficiency.

Surgical Technique

A demonstration of the reconstruction technique in a right shoulder is provided in Video 1. Table 1 describes the preoperative clinical evaluation and imaging in patients with recurrent multidirectional shoulder instability. The indications and contraindications of the procedure are presented in Table 2. The pearls and pitfalls of the procedure are summarized in Table 3.

Table 1.

Evaluation of Recurrent Multidirectional Shoulder Instability

| Patient history |

| Symptoms can include pain, instability, weakness, mechanical symptoms and/or crepitus, and paresthesia |

| Atraumatic dislocation and/or subluxation with daily activities |

| History of surgical procedures |

| History of diagnosed or suspected soft-tissue disorder—genetic consultation or testing should be considered |

| Physical examination |

| Sulcus sign |

| Apprehension or relocation test |

| Posterior load-and-shift test |

| Generalized hypermobility (i.e. Beighton criteria17) |

| Imaging studies |

| Standard radiographic evaluation in multiple planes with AP, true AP (Grashey), axillary lateral, and scapular Y views |

| Advanced imaging including MR or CT scan—bone loss or pathologic bony conditions such as glenoid hypoplasia or excessive glenoid anteversion or retroversion should be ruled out; 3-dimensional reconstructions with humeral head subtraction can aid in glenoid bone loss evaluation |

AP, anteroposterior; CT, computed tomography; MR, magnetic resonance.

Table 2.

Indications and Contraindications of Arthroscopic Posterior Capsular Augmentation With Gracilis Tendon Allograft

| Indications |

| Recurrent glenohumeral multidirectional instability with capsular insufficiency due to multiple prior surgical procedures or underlying soft-tissue disorder |

| Failed nonsurgical management |

| Contraindications |

| Significant bone loss or deficiency (bony Bankart lesion, engaging Hill-Sachs lesion, glenoid hypoplasia) |

| Voluntary recurrent dislocation |

Table 3.

Pearls and Pitfalls of Arthroscopic Posterior Capsular Augmentation With Gracilis Tendon Allograft

| Pearls |

| Different colored sutures should be used in graft preparation for easier identification during the procedure. |

| A graft length of approximately 65 mm is critical. Whipstitching may affect the functional length of the graft, so the graft should be trimmed to length after placement of whipstitches. |

| Some counter tension should be held on the sutures of the trailing end of the graft as it is shuttled into the joint to avoid suture or graft entanglement. |

| The graft should be drawn fully into the joint, and after placement of the inferior glenoid anchor, the graft should be pushed inferiorly to allow free space for placement of the superior glenoid anchor. |

| Pitfalls |

| Graft and suture entanglement can complicate suture management. |

Patient Positioning and Preparation

The patient undergoes a single-shot interscalene block, and general anesthesia is induced. The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position. The operative shoulder is examined with the patient under anesthesia: ROM and instability including glenohumeral translation and the sulcus sign are documented. The operative shoulder is placed in 10 lb of traction at approximately 50° of abduction and 20° of forward flexion, with neutral rotation.

Diagnostic Arthroscopy

Standard anterior and posterior arthroscopic portals are established. A diagnostic arthroscopy of the glenohumeral joint is performed with the arthroscope in the posterior portal. Optionally, a capsulorrhaphy plication stitch can be placed anteriorly through the capsule and glenoid labrum using a curved, cannulated suture passer (SutureLasso; Arthrex, Naples, FL) and free braided polyethylene-polyester suture (SutureTape; Arthrex). The suture is docked outside the cannula for tying later in the procedure. Switching sticks are used to move the arthroscope to the anterior portal. A cannula with deployable internal wings (Gemini cannula; Arthrex) is placed posteriorly to establish a working portal.

Graft Preparation

A gracilis tendon allograft is selected that is no more than 5 mm in diameter. The graft is trimmed to 65 mm in total length with whipstitches (FiberLoop; Arthrex) on both ends and a single suture in a luggage-tag configuration (FiberLink; Arthrex) at the midpoint to form the apex (Fig 1). Different suture coloration schemes should be selected for each suture to aid in identification during the procedure.

Fig 1.

The gracilis tendon allograft, no greater than 5 mm in diameter, is trimmed to 65 mm in total length with whipstitches (FiberLoop) on both ends and a single suture in a luggage-tag configuration (FiberLink) at the midpoint to form the apex. The end FiberLoops are anchored to the glenoid, and the apex FiberLink is anchored to the humeral head. Different suture coloration schemes should be selected for each suture to aid in identification during the procedure.

Graft Shuttling and Anchor Placement

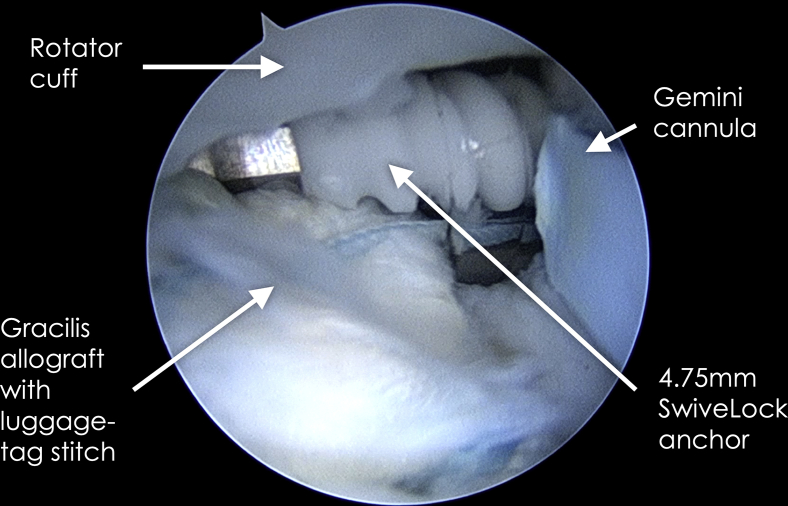

As an accessory posterolateral portal, the portal of Wilmington is established with spinal needle localization and a small skin incision. A disposable percutaneous cannula kit for the 2.9-mm PushLock suture anchor (Arthrex) is placed through this accessory portal, a pilot hole is drilled into the posterior-inferior glenoid, and the first PushLock anchor is placed through the portal and into the joint but not yet impacted into place. A SutureLasso is placed into the posterior working portal cannula, and the nitinol loop is threaded through the anchor eyelet and retrieved (Fig 2). The FiberLoop suture at the end of the first limb of the graft is loaded into the nitinol loop and shuttled through the eyelet at the tip of the anchor. The suture is used to shuttle the graft into the joint through the Gemini cannula, pulling counter tension on the graft's other suture limbs to prevent tangling or bunching of the graft (Fig 3). With the graft pulled into the joint and at the tip of the PushLock, the anchor is placed into the pilot hole, ensuring that no soft tissue from the graft obstructs the pilot hole, and is secured with a mallet (Fig 4). The graft is then pushed fully into the joint to clear the Gemini cannula and pushed inferiorly to free up working space. Next, placement of a more proximal mid-glenoid posterior anchor is achieved in the same fashion as the first, anchoring the other end of the graft (Fig 5).

Fig 2.

Right shoulder with patient in lateral decubitus position and an anterior viewing portal. A 2.9-mm PushLock suture anchor is placed into the joint through a percutaneous cannula using an accessory posterolateral portal (i.e. portal of Wilmington). A left curved SutureLasso is brought into the joint through the Gemini cannula in the posterior portal and used to pass a nitinol wire loop through the PushLock eyelet. The nitinol wire is then retrieved through the posterior portal and used to shuttle the graft FiberLoop suture through the eyelet in preparation for anchoring at the glenoid.

Fig 3.

Right shoulder with patient in lateral decubitus position. The graft is shuttled into the joint through the Gemini cannula in the posterior portal. The camera is in the anterior portal, and a 2.9-mm PushLock suture anchor is held in the joint space through a posterolateral accessory portal with a percutaneous cannula.

Fig 4.

Right shoulder with patient in lateral decubitus position and anterior viewing portal. With the graft shuttled into the joint using suture through the eyelet of the 2.9-mm PushLock suture anchor, the graft is anchored into the pilot hole created at the posterior-inferior glenoid.

Fig 5.

Right shoulder with patient in lateral decubitus position and anterior viewing portal. The second end of the graft is anchored into the mid-posterior glenoid using a second 2.9-mm PushLock suture anchor.

A pilot hole is then placed into the posterior humeral head directly opposite the 2 anchored limbs of the graft. The luggage-tag FiberLink suture at the apex of the graft is loaded into a 4.75-mm SwiveLock anchor (Arthrex) and secured into the hole (Fig 6), which gives an inverse V shape to the final graft configuration (Fig 7).

Fig 6.

Right shoulder with patient in lateral decubitus position and anterior viewing portal. The apex of the graft is anchored to the posterior humeral head at the articular margin using a 4.75-mm SwiveLock anchor and the FiberLink suture previously placed at the graft's apex.

Fig 7.

Right shoulder with patient in lateral decubitus position and anterior viewing portal. The final graft configuration is an inverse V, with either end anchored to the glenoid and the apex anchored to the humeral head. Anchor points are labeled with yellow text and arrows.

Next, as desired, a posterior capsule suture plication can be performed. A SutureLasso is introduced through the posterior portal cannula, and suture plication using a free SutureTape suture is performed, securing the posterior-inferior capsule to the allograft augmentation with arthroscopic knots.

The camera is again placed posteriorly, and the working portal is re-established anteriorly using switching sticks. Any previously placed anterior capsulorrhaphy plication stitches are tied arthroscopically reducing the anterior-inferior capsular pouch volume.

Postoperative Care

The operative shoulder should be immobilized in a sling with an abduction pillow for 6 weeks postoperatively at all times except during bathing and exercise activity. Under the guidance of a skilled therapist, the patient can proceed through early restricted and protected ROM exercises, first passive and then progressing to active-assisted ROM (phase 1). This includes external rotation at 90° of abduction as tolerated and forward flexion to 90° as tolerated but no internal rotation for 8 weeks. Submaximal shoulder isometrics and rhythmic stabilization drills are also incorporated. Over weeks 9 to 16 (phase 2), rehabilitation focuses on gradually re-establishing ROM, normalizing arthrokinematics, increasing strength, improving neuromuscular control, and enhancing proprioception and kinesthesia. By week 16, the patient should have achieved full, non-painful ROM; no pain or tenderness; and strength at 70% of the contralateral side. Then, the patient can enter phase 3, focused on dynamic strengthening. Return to unrestricted activity can be expected at approximately 24 to 28 weeks postoperatively.

Discussion

Many novel reconstruction techniques have been proposed to address the difficult problem of recurrent shoulder instability. Anterior reconstruction techniques have been described using graft from the iliotibial band,18, 19 Achilles tendon,20, 21 hamstring tendon,22, 23, 24 tibialis anterior tendon allograft,8, 16 split subscapularis tendon flap,25 and more recently, acellular human dermal allograft capsular reconstruction.26, 27 An alternative anterior augmentation approach describes using a folded porcine skin surgical mesh membrane to reconstruct the anterior glenoid labrum and create a voluminous anterior bumper.28

Described posterior-based soft-tissue procedures are fewer but have included simultaneous anterior and posterior reconstruction with Achilles allograft.21 Recently, an arthroscopic dermal allograft reconstruction procedure was described,29 which is similar in concept to currently used superior capsular reconstruction techniques.30

Compared with other allograft augmentation techniques described previously, the advantages of our technique include its relative simplicity, speed and ease of use, knotless fixation, and ability to combine the technique with other procedures including capsulorrhaphy and labral repair. Normal anatomic relations are preserved, making potential revision easier. Nonanatomic solutions such as the Latarjet procedure can be reserved as a future salvage option (Table 4).

Table 4.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Arthroscopic Posterior Capsular Augmentation With Gracilis Tendon Allograft

| Advantages |

| Standard arthroscopic setup and portals |

| Familiar arthroscopic shuttling and anchor placement techniques |

| Can be used in combination with concurrent arthroscopic procedures such as capsular plication |

| Allograft tissue avoids need for graft harvest and avoids risk of autograft tissue failure owing to underlying collagen disorder |

| Soft-tissue procedure avoids nonanatomic bony procedures and maintains anatomic range of motion |

| Bony augmentation (i.e. Latarjet) can be reserved as salvage procedure |

| Disadvantages |

| Risk of surgical failure at anchor or graft-suture interface may result in intra-articular loose foreign body requiring revision arthroscopy for removal with or without revision stabilization procedure |

| Inability to address significant bone loss with this procedure |

The ability to treat multidirectional instability with a posteriorly based procedure is supported in the literature. One recent study showed that posterior medial capsular plication reduced anterior shoulder instability without restricting motion in the setting of an engaging Hill-Sachs defect.31

Initial results after use of the described technique have been promising, with patients experiencing restored stability without sacrificing ROM. Arthroscopic posterior capsular augmentation with gracilis tendon allograft can be a very useful and reproducible technique in patients with capsular insufficiency and/or collagen disorders, and it should be considered in cases of multidirectional instability without significant bone defects.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest or sources of funding: M.D.M. is a paid consultant and speaker for Arthrex. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

Posterior capsular augmentation technique. With the patient in the lateral decubitus position, a right shoulder is viewed from an anterior portal. A 65-mm-long gracilis tendon allograft is anchored with two 2.9-mm PushLock suture anchors to the posterior glenoid and one 4.75-mm SwiveLock anchoring the graft's apex to the humeral head.

References

- 1.Vavken P., Tepolt F.A., Kocher M.S. Open inferior capsular shift for multidirectional shoulder instability in adolescents with generalized ligamentous hyperlaxity or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:907–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens B.D., Cameron K.L., Peck K.Y. Arthroscopic versus open stabilization for anterior shoulder subluxations. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3 doi: 10.1177/2325967115571084. 2325967115571084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Latarjet M. [Treatment of recurrent dislocation of the shoulder] Lyon Chir. 1954;49:994–997. [in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi M.A., Young A.A., Balestro J.C., Walch G. The Latarjet-Patte procedure for recurrent anterior shoulder instability in contact athletes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2015;46:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marion B., Klouche S., Deranlot J., Bauer T., Nourissat G., Hardy P. A prospective comparative study of arthroscopic versus mini-open Latarjet procedure with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2017;33:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu Y., Jiang C., Song G. Arthroscopic versus open Latarjet in the treatment of recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation with marked glenoid bone loss: A prospective comparative study. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:1645–1653. doi: 10.1177/0363546517693845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmermann S.M., Scheyerer M.J., Farshad M., Catanzaro S., Rahm S., Gerber C. Long-term restoration of anterior shoulder stability: A retrospective analysis of arthroscopic Bankart repair versus open Latarjet procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1954–1961. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.01398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun S., Millett P.J. Open anterior capsular reconstruction of the shoulder for chronic instability using a tibialis anterior allograft. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;9:102–107. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warner J.J., Gill T.J., O'Hollerhan J.D., Pathare N., Millett P.J. Anatomical glenoid reconstruction for recurrent anterior glenohumeral instability with glenoid deficiency using an autogenous tricortical iliac crest bone graft. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:205–212. doi: 10.1177/0363546505281798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millett P.J., Schoenahl J.Y., Register B., Gaskill T.R., van Deurzen D.F., Martetschlager F. Reconstruction of posterior glenoid deficiency using distal tibial osteoarticular allograft. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:445–449. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Provencher M.T., Frank R.M., Golijanin P. Distal tibia allograft glenoid reconstruction in recurrent anterior shoulder instability: Clinical and radiographic outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2017;33:891–897. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kropf E.J., Sekiya J.K. Osteoarticular allograft transplantation for large humeral head defects in glenohumeral instability. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:322.e1–322.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diklic I.D., Ganic Z.D., Blagojevic Z.D., Nho S.J., Romeo A.A. Treatment of locked chronic posterior dislocation of the shoulder by reconstruction of the defect in the humeral head with an allograft. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:71–76. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B1.22142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buza J.A., III, Iyengar J.J., Anakwenze O.A., Ahmad C.S., Levine W.N. Arthroscopic Hill-Sachs remplissage: A systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:549–555. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massoud S.N., Levy O., de los Manteros O.E. Histologic evaluation of the glenohumeral joint capsule after radiofrequency capsular shrinkage for atraumatic instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dewing C.B., Horan M.P., Millett P.J. Two-year outcomes of open shoulder anterior capsular reconstruction for instability from severe capsular deficiency. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grahame R., Bird H.A., Child A. The revised (Brighton 1998) criteria for the diagnosis of benign joint hypermobility syndrome (BJHS) J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1777–1779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallie W.E., Le Mesurier A.B. Recurring dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948;30B:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iannotti J.P., Antoniou J., Williams G.R., Ramsey M.L. Iliotibial band reconstruction for treatment of glenohumeral instability associated with irreparable capsular deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:618–623. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.126763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moeckel B.H., Altchek D.W., Warren R.F., Wickiewicz T.L., Dines D.M. Instability of the shoulder after arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:492–497. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaudhury S., Gasinu S., Rodeo S.A. Bilateral anterior and posterior glenohumeral stabilization using Achilles tendon allograft augmentation in a patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazarus M.D., Harryman D.T. Open repair for anterior instability. In: Warner J.J.P., Iannotti J.P., Gerber C., editors. Complex and revision problems in shoulder surgery. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia, PA: 1997. pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warner J.J., Venegas A.A., Lehtinen J.T., Macy J.J. Management of capsular deficiency of the shoulder. A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1668–1671. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200209000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouaicha S., Moor B.K. Arthroscopic autograft reconstruction of the inferior glenohumeral ligament: Exploration of technical feasibility in cadaveric shoulder specimens. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2013;7:32–36. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.109893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denard P.J., Narbona P., Ladermann A., Burkhart S.S. Bankart augmentation for capsulolabral deficiency using a split subscapularis tendon flap. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pogorzelski J., Hussain Z.B., Lebus G.F., Fritz E.M., Millett P.J. Anterior capsular reconstruction for irreparable subscapularis tears. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6:e951–e958. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whelan A., Coady C., Ho-Bun Wong I. Anterior glenohumeral capsular reconstruction using a human acellular dermal allograft. Arthrosc Tech. 2018;7:e1235–e1241. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gervasi E., Sebastiani E., Spicuzza A. Multidirectional shoulder instability: Arthroscopic labral augmentation. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6:e219–e225. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karpyshyn J., Gordey E.E., Coady C.M., Wong I.H. Posterior glenohumeral capsular reconstruction using an acellular dermal allograft. Arthrosc Tech. 2018;7:e739–e745. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laskovski J.R., Boyd J.A., Peterson E.E., Abrams J.S. Simplified technique for superior capsular reconstruction using an acellular dermal allograft. Arthrosc Tech. 2018;7:e1089–e1095. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werner B.C., Chen X., Camp C.L., Kontaxis A., Dines J.S., Gulotta L.V. Medial posterior capsular plication reduces anterior shoulder instability similar to remplissage without restricting motion in the setting of an engaging Hill-Sachs defect. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:1982–1989. doi: 10.1177/0363546517700860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Posterior capsular augmentation technique. With the patient in the lateral decubitus position, a right shoulder is viewed from an anterior portal. A 65-mm-long gracilis tendon allograft is anchored with two 2.9-mm PushLock suture anchors to the posterior glenoid and one 4.75-mm SwiveLock anchoring the graft's apex to the humeral head.