Abstract

mHealth interventions promise the economic delivery of evidence-based mental health treatments like cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to populations that struggle to access health services, such as adolescents and in New Zealand, Māori and Pasifika youth. Unfortunately engagement with digital therapies is poor; modularisation and gamification have potential to increase their appeal. Gamifying CBT involves selecting suitable interventions, adapting them to a digital format while applying gamification principles. We describe the design and development of Quest - Te Whitianga, an app that encourages the user to learn CBT skills via a series of activities and games. A variety of approaches including consultation with clinicians, reference to best-practice literature, focus groups and interactive workshops with youth were used to inform the co-design process. Clinicians worked iteratively with experienced game designers to co-create a youth CBT digital intervention. The Quest modular app is set on an ocean and the user travels between islands to learn six evidence-based skills. These include a relaxation/mindfulness activity, activity planning, a gratitude journal plus problem solving and communication skills training. We describe the theoretical and design aspects of each module detailing the gamified features that aim to increase user engagement. In the near future we will be testing the app and the principles discussed in this paper via a randomised-controlled trial.

Abbreviations: ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; cCBT, computerized cognitive behavioural therapy; mHealth, mobile (device) health

Keywords: Digital cognitive behavioural therapy, Gamification, Smartphone treatment, Adolescent, Mental health

Highlights

-

•

We describe the iterative co-design of an mHealth app, Quest - Te Whitianga, for young people with emotional difficulties

-

•

Co-design with Māori and Pasifika youth is important to assist with cultural engagement

-

•

The app uses modularisation and gamification extensively to enhance engagement as well as the learning of CBT principles

-

•

A wide and varied range of gamification elements were used across the various modules in the Quest - Te Whitianga app

1. Introduction

In the last decade there has been increased development of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy (cCBT) interventions. This has been driven by the promise of addressing unmet need for traditional psychological therapies, which are expensive and difficult to access for many populations, combined with rapidly growing access to internet-enabled devices and cheaper software development (Khazaal et al., 2018).

Many cCBT interventions for anxiety and depression are untested; however, enough have shown promise such that there is now little debate about the potential merit of internet-based treatment in young people (Ebert et al., 2015; Pennant et al., 2015). In a recent meta-analysis cCBT was shown to be effective for young people, yielding a medium effect; g = 0.66 (Grist et al., 2018). Importantly, it is also acceptable, especially for those with mild or moderate illness (Shih Ying et al., 2011). The focus of research is now very much on ‘real world’ implementation, as the promise demonstrated in the research environment has not been shown to the same degree in naturalistic settings; completion of digital interventions falls well below that anticipated from the research trials (Fleming et al., 2016; Mohr et al., 2017).

Therapist-led CBT typically consists of a series of six or more face-to-face meetings, often a week apart, interspersed with homework tasks (Beck et al., 1979; Szigethy et al., 2012). In many early versions of cCBT, treatment was provided along similar lines, albeit digitally, with the user completing a lot of reading and some typing, instead of talking (Stasiak and Merry, 2015). Unsurprisingly, engagement with this kind of treatment is poor (Fleming et al., 2018). The therapeutic alliance has always been a key factor in both the success of, and engagement with all kinds of therapy and, more than any treatment factor, it has the greatest influence on clients' participation (Holdsworth et al., 2014). A lack of personal contact likely contributes to poor adherence to cCBT, along with various other factors, such as potential confusion about the applicability of the treatment, lack of support/oversight, inadequate computer skills and unrealistic expectations (Gerhards et al., 2011; Johansson et al., 2015). That said, non-completers of cCBT still get some benefit from partial involvement and increasing the choices for users and providing reminders have been shown to increase adherence (Hilvert-Bruce et al., 2012).

Gamification has arisen as a potential remedy to poor adherence with cCBT and on the face of it, the idea would have potential, especially for young people. Gaming is now very much a part of normal adolescent life and adjusting to and managing its compelling nature is just another of the developmental challenges that young people meet through adolescence (Brooks et al., 2016). Gamification involves the incorporation of electronic gaming elements into non-gaming contexts. An example of this is ‘Pain Squad’, an app-based pain diary that supports paediatric patients age 9–18 through a pain management program. It incorporates a narrative, in-game rewards and point scoring (Stinson et al., 2013). ‘Serious games’ take gamification a step further and usually include a full range of gaming elements (Marsh, 2011). Initial studies of ‘serious games’ suggest that they can lead to positive psychological and behavioural changes as well as symptom relief (Merry et al., 2012; Tarrega et al., 2015; Sardi et al., 2017a; Sardi et al., 2017b). A recent study examining gamification in mental health interventions found 28 programmes that applied gamification, serious games or virtual reality as part of the therapy or used gamification as a way to promote engagement and adherence to treatment (Dias et al., 2018) but overall, empirical research on serious games and their mental health applications is less developed than that of cCBT (Fleming et al., 2014).

As mobile phones become ubiquitous in societies across the globe there has also been a rise in the number and sophistication of ‘mHealth’ interventions and many of these health-oriented smartphone apps use gamification (Bakker et al., 2016). Similarly to cCBT, only a handful of mHealth tools have been empirically tested and concerns about translation from the research environment to the real world remain (Torous and Powell, 2015). Interventions delivered via a mobile platform are an obvious next step in light of the increasing primacy of mobile phones in young people's lives (Lauricella et al., 2014). Young people are now more likely to have a mobile phone than to own a personal computer and expect to access most software via their smart phones. The easy assimilation of mHealth approaches into users' everyday routine means it makes sense to design treatment for this platform (Ly et al., 2015), as it may lead to better engagement with cCBT interventions.

In this paper we outline the process we took in developing a gamified mHealth CBT intervention, Quest - Te Whitianga. Our aim is to provide a description of the therapeutic components utilised and the steps taken during the co-design process to gamify a mHealth CBT intervention for adolescents.

2. Methods

For our app, Quest - Te Whitianga, we embarked on an extensive scoping phase prior to product conception and software development. It included various qualitative methods to collect feedback from a range of stakeholders including youth services, primary healthcare providers and schools. The emphasis was on feedback from young people from Māori (indigenous New Zealand people) and Pacific communities, both of which are underserved by the health system (Sheridan et al., 2011). This initial scoping process sought to understand young people's current use of e-therapies to inform the subsequent co-design process and is described elsewhere (Fleming et al., 2019).

Following this scoping phase, we undertook an iterative and inclusive process across the conception and design of Quest - Te Whitianga. When designing software for internet therapies, planning across all stages of development, from conception to user analysis, ideation and implementation is recommended (Morschheuser et al., 2018). Expert advice was sought from clinicians via face-to-face interviews and focus groups regarding the optimum balance of skills-based activities and interventions in the app. We engaged a software development company and began development using fortnightly (approximately) sprints with software, graphics and narrative designers. The ‘sprint’ involved a meeting of 1 to 2 h where specific aspects of the app design and user experience were discussed and trialled. Visuals, sounds and wireframe models detailing how the interventions would perform and appear would be considered and discussed. Following this, the designers and investigators would spend the next week or so working on specific tasks, for example creating content, such as written text or artwork. As development progressed, the overall design, appearance, components and the delivery method of the app were built and improved incrementally, on a week by week basis.

Interspersed with these sessions involving the investigators and the software company were fifteen short sessions with adolescents in two high schools (with mostly Māori and Pacific youth) and eight more in-depth workshops. Young people's feedback was used to identify and enhance the ‘look and feel’ of the app and maximise its engagement and utility. As part of the co-design process, Māori and Pacific young people allowed the exploration of how Māori values and cultural practices (tikanga) could be incorporated into the app to reflect to assist with engagement of Māori adolescents.

The first prototype app had three modules that included a gratitude journal, a mindfulness activity and a game that taught about the interaction between thoughts, feelings and actions. We incorporated an aesthetic to appeal to Māori and Pacific young people and included gamification and a fantasy storyline to encourage users to use the app daily. Following the completion of this prototype app, a more formal evaluation occurred with a sample of 30 young people using think-out loud interviews, a usability testing method where participants verbalise their thoughts as they move through the user interface of the app. Feedback from this process included that young people liked the artwork, having a ‘companion’ character and the process of collecting badges and rewards. On the other hand, they disliked the story line and wanted shorter games that could be played more frequently.

The findings from this process formed the foundation for the further development of Quest. This second extensive development stage was more focussed on implementing the feedback and improving the user interface, thus involved more direct collaboration between the developers and investigators, with less input from young people. We extended the range of modules, put less emphasis on the narrative story, added more customisation and choice and enhanced the gamification features (points, badges, leveling up) with a more direct focus on younger adolescents (who were most receptive to the gamified aspects of the software).

2.1. Selecting therapeutic components: weighing up effectiveness vs gamification

CBT and related therapies such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (Hayes et al., 2011) are psychological intervention processes that examine and seek to change cognitions (how we think about ourselves, relationships and the future), our behaviours (what we do, problem solving, conflict resolution) and feelings via a conversational relationship with a therapist. Many therapies can be broken down into a range of tasks, skills and learning points. One of the key tasks for the development team was deciding on which specific intervention techniques should be incorporated into the app.

We considered and attempted to balance a number of factors. Firstly, we considered which psychological principles are the most effective, or rather, how do we get best ‘bang for our buck’. Expecting young people to persist with a programme over a number of weeks is unrealistic (Mohr et al., 2017) and most improvement with cCBT, if it is going to occur, transpires in the first four weeks of treatment with further gains often minimal (Pratap et al., 2018). Integrating all components of a therapist-led CBT programme into a brief mHealth tool for young people was not feasible and instead we were interested in selecting those therapeutic elements that were most likely to be of benefit.

We extended the range of therapeutic techniques beyond what is traditionally considered CBT to include other evidence based strategies that fit well with CBT approaches, sourcing techniques from positive psychology (Fredrickson, 2001), mindfulness (Kabat-Zinn et al., 1985) and interpersonal skills (Christie and Viner, 2005).

We had to consider how easily a given principle could fit into our desired game framework. For example, can the learning of the cognitive model of depression (Beck, 1976), be made into a game of skill? Can competitive elements be added to it? Does the game demonstrate the learning principles well? How can the attributes of a smart phone be utilised best to enhance the experience of learning and applying CBT skills in young people's lives?

The eventual process for selecting and gamifying the therapeutic elements was iterative, informed by the co-design with young people, and the step-by-step creative process that unfolded while explaining the various treatment principles to the software developers and brainstorming together how these might be gamified. The final results are described and discussed below.

2.2. Gamification elements

Guidance around gamification of mental health interventions suggests using a range of options such as strategies which offer opportunities for the discovery of information, having a balance between challenge and difficulty and providing step-wise achievements (Goh et al., 2008). There are a number of accepted standard key gamification elements which are discussed at length elsewhere (Miller et al., 2014; Cugelman, 2013; Seaborn and Fels, 2015). We endeavoured to incorporate these in Quest – Te Whitianga and specific details regarding how these were included in the app are discussed below and summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Gamification features used in Quest – Te Whitianga.

| Gamification mechanism | Amalgamated from (Miller et al., 2014, Cugelman, 2013, Seaborn and Fels, 2015) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Explanation | Use in Quest | |

| Points, scores, feedback | Units or other indicators (time or lives left) indicating progress | Points are earned daily for gratitude journal entries and for completing challenges on other islands. Points accumulate and user can save or spend them on customisation of the ‘home island’. Progress is visible through ‘leveling’ on each island and by being able to unlock the next available island (when it appears from out of the volcanic ash). |

| Badges, rewards | Visual icons or game tokens signifying achievements | Completing three levels of each island (‘minimum dose’) earns the player a badge in the form of a motivational poster (whakatauki). All badges are displayed on the user's dashboard. |

| Leaderboards, ranks and status | Display of ranks for comparison or monikers indicating progress | At this stage of the project, this feature has not been implemented to protect the anonymity of trial participants. |

| Progression | Milestones in the game indicating progress or providing comparison | Islands get revealed one by one as the user levels up. Guardians (kaitiaki) are revealed after 3 levels on each island. Each island is visually transformed after the kaitaki reveal to symbolise achievement, happiness and wellbeing. |

| Narrative, challenges and quests | Stories or tasks that organise character roles, rewards and guide action | Through onboarding and gameplay, a story of mythical islands and their guardians (kaitiaki) that hold knowledge of wellbeing is used to provide an overarching narrative and context for the game. |

| Levels | Increasing difficulty of activities | Each island (other than the home island which is unlimited) has 6 or more levels which are progressively more challenging to complete or build on previously acquired skill set. |

| Roles, avatars | A personalised and customisable representation of player | Player is invited to customise their avatar upon onboarding and can update it throughout the game. The aesthetic of the avatar reflects the style of the game. |

| Social engagement | Sharing of progress and/or gameplay with social media contacts | At this stage of the project, this feature is not available on account of cost and also to protect the anonymity of trial participants but feedback to date suggests that some would like to post their game's progress, compete against other or display on social media their collected badges or other achievements. |

3. Results and discussion

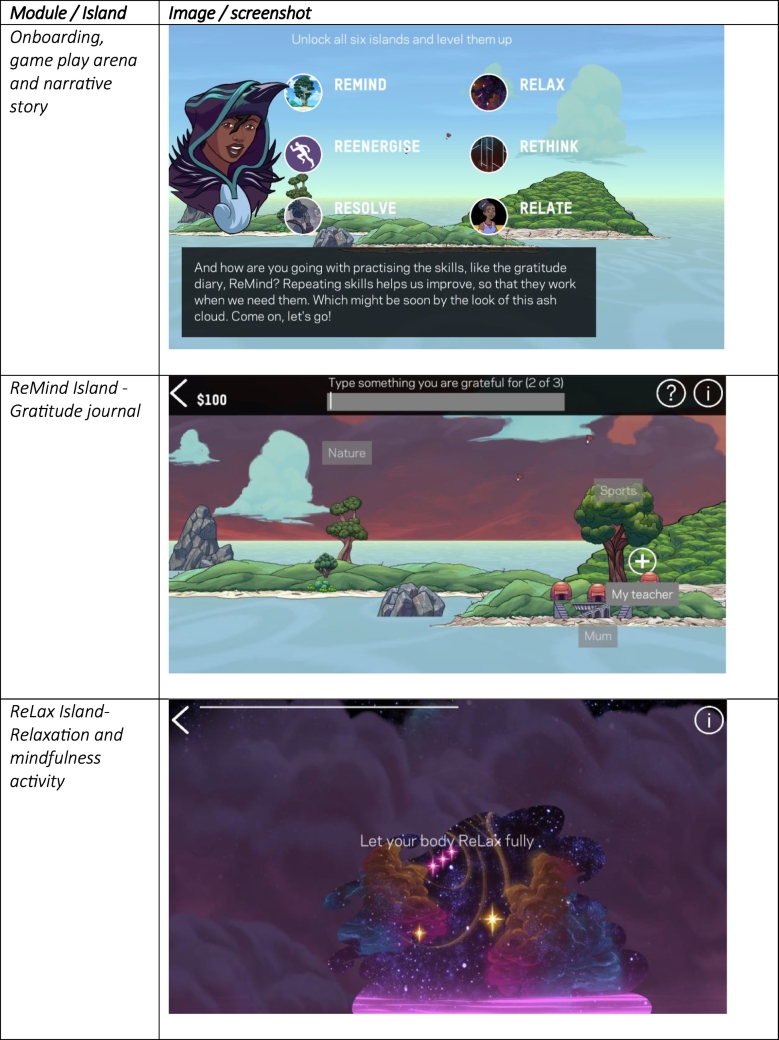

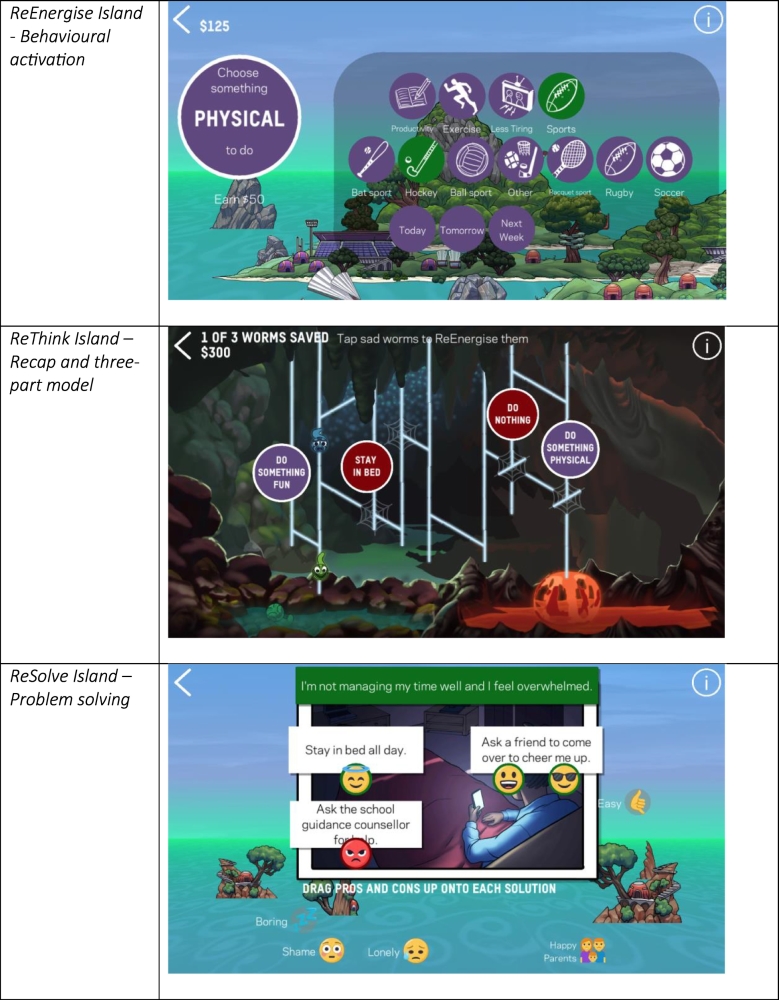

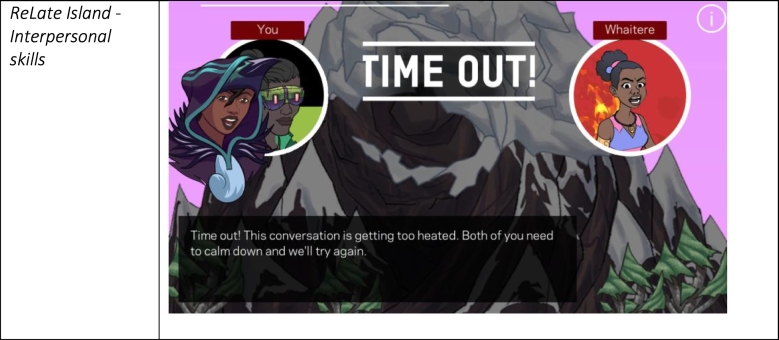

The following sections describe and discuss the way that we applied gamification to the chosen CBT techniques selected for our tool, Quest – Te Whitianga. Images from each part of the game as detailed below are provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Quest - Te Whitianga artwork from each module/island.

3.1. Onboarding, game play arena and narrative story

The setting for Quest - Te Whitianga is an imaginary archipelago of islands impacted by a volcanic eruption. The game's host ‘Tata’ enlists the player to find her 5 ‘kaitiaki’ friends, each being the guardian of an island that holds ancient wisdom on a different aspect of well-being. The guardians are represented by an indigenous bird or sea creature, the strengths from each of these highlighted in the narrative that Tata shares with the participant. Participants also learn the Māori name and cultural significance of the bird or sea creature thus reinforcing the cultural adaption of the programme. Tata's role provides a purpose for the app (to learn skills and enhance well-being) and scaffolds the user experience, encouraging completion. During the onboarding, no specific skill is taught but the overall context is set, allowing story development to occur as the player progresses. The user learns how to navigate the game world, how to check their overall progress and review rewards, which include points and Maori proverbs or sayings, ‘whakatauki’, chosen to encourage engagement (Savage et al., 2011). The user is also able to customise their avatar, which creates emotional investment and increases the personal relevance of the overall experience. These attributes aim to contribute to ongoing engagement and allow repetition of activities, promoting reinforcement of principles learned, akin to completing daily ‘homework’, a factor that is highly associated with increasing effectiveness of CBT treatment (Kazantzis et al., 2016).

3.2. ReMind Island – gratitude journal

Each time players visit this island they are cued to enter three things they are grateful for. This earns money (points or game's ‘currency’) which can be saved and spent on features, such as huts, trees, boats, used to enhance the island. The player can choose from suggested options (rather than entering their own) to help model potential answers and reduce cognitive load. The activity on this island, practising gratitude, is based on a key principle of positive psychology (Fredrickson, 2001) and orients a young person's thinking and focus away from setbacks, problems and deficits towards the more positive aspects of their life. It is a strengths-based skill that can be empowering, as well as increasing satisfaction and hopefulness (McCullough et al., 2004). In clinical populations, trials show that practising gratitude promotes happiness and well-being and reduces symptoms related to depression and anxiety (Wood et al., 2010). Players are encouraged to return to this island each day (maximum twice a day) and are reminded of the good things they have recorded in the diary, as well as recording more gratitude items. The island, which is bare at first following the volcanic eruption can serve as a creative outlet as the user fills it with features they select and position.

3.3. ReLax Island – relaxation and mindfulness activity

On this nocturnal island, the player clears away a volcanic ash cloud by slowly and mindfully tracing their finger across the screen. As they do this, stars, celestial bodies and constellations are revealed. Messages appear during the activity such as ‘time your breathing and relax fully’, promoting and teaching relaxation. Relaxation has a number of applications across a range of psychological conditions and is particularly helpful for anxiety and depressive symptoms with a meta-analysis demonstrating moderate to high effect size of relaxation training (Kim and Kim, 2018). Mindfulness is a related skill, that enhances awareness through the skill of purposefully and non-judgmentally paying attention, in the present moment, which can help to neutralise ruminative and negative thinking (Kabat-Zinn et al., 1985). Components of mindfulness training are also included in the messaging related to the island. Each time the player returns to the island, the activity lasts longer, scaffolding the development of this skill and increasing a sense of competence. A progress bar (to indicate elapsed/remaining time) is included to reduce uncertainty.

3.4. ReEnergise Island – behavioural activation

On this island the player learns the importance of being active and how planning a range of different activities can enhance mood and well-being. Initially the player is introduced to brief activities that can be done immediately, such as ‘forced smiling’ (Neuhoff and Schaefer, 2002), providing instant feedback about the positive effect of actions on feelings. Next the player selects activities for completion later in the day or week across three categories; novel, energetic and fun. Behavioural activation (BA) is well-studied and is one of the most effective CBT components (Ekers et al., 2014). It is based on a behavioural model of depression; that low mood stems from a lack of positive reinforcement. It is highly customisable and includes self-monitoring to track activities and their impact on mood so that the client can see for themselves how actions (or inaction) can produce emotions. It also taps into the positive physiological effects of exercise on general wellbeing. As such it is an ideal strategy for any young person, regardless of whether they suffer from symptoms or not. Internet guided behavioural activation has been shown to have similar efficacy to a number of other treatments for depression in meta-analysis (Huguet et al., 2018). The range of activities on this island is structured in a branching manner to reduce the cognitive load associated with processing long lists. Low effort activities are used to ‘onboard’ young people, allowing completion of an interaction loop easily, quickly demonstrating how the game points can be earned. When the player returns, they report on the activities that have been completed and are rewarded with game currency that can be spent on the ReMind (home) island.

3.5. ReThink Island – recap and three-part model

On the ReThink island, the player helps glow worms negotiate their way through a maze of silk strands, changing junctions so that angry, sad, worried and happy glow worms can avoid ‘hot’ thinking (hot lava) and navigate towards ‘cool’ thinking (plunge pool). There are seven levels where the glow worms contend with different emotions, using a range of different strategies. Since first proposed, a key part of cognitive behavioural therapy (Beck et al., 1979) is providing the client with a way to conceptualise how their mood, emotions and actions interact. This is now most commonly described as the five part model (Greenberger and Padesky, 1995) although ReThink focusses mostly on demonstrating the relationship between thoughts, feelings and actions. Initially, ReThink reinforces learning from the first three islands, recapping principles of gratitude, relaxation and activation, but presenting them in different contexts. As the player advances (level 4 and beyond), they learn how thoughts, emotions and actions interact and how changing thoughts can promote positive well-being. The game dynamics do not enable the player to actually participate in actually recognising or changing their own negative cognitions, as might happen in therapy but they see this occurring. For example, worms experiencing negative thoughts can be directed through zones that introduce the concepts of distraction, acceptance and ‘rethinking’, and this is achieved by changing the content of a given thought (illustrated via speech bubbles). ReThink is designed most like a game and the user's play strategy directly impacts the conclusion, modelling that changing thoughts and actions can lead to change in feelings and outcome. The overall game system promotes positive well-being as helping glow worms to feel ‘chilled’ (i.e. landing in the plunge pool) leads to progression through the levels. Sound effects are used to add humour and a sense of achievement.

3.6. ReSolve Island – problem solving

Problem-solving therapy teaches skills to help to manage stressful events, large and small, helping young people to cope more effectively with difficulties (D'zurilla and Nezu, 2007). Using it can decrease the negative impact of stress and can increase one's sense of self-efficacy. The development of skills in this area is important in youth development for promoting well-being as well as improving the quality of life of those suffering from a mental health and physical health problems. Problem solving therapy is extensively studied and has been shown to be similar or superior to other psychological treatments for depression and anxiety (Cuijpers et al., 2018). Problem solving skills are taught on the ReSolve island via a series of six interactive scenarios relevant to young people. The game teaches basic problem-solving therapy using an easy to remember ‘STEPS’ acronym, which stands for: ‘Say what the problem is; Think of solutions; Examine them; Pick one; See what happens.’ These five problem-solving stages are reinforced through discrete scenarios; at each the player defines the problem, makes choices and finds solutions to common youth issues such as struggling at school and bullying through social media. Visual aids complement the text scenarios to enhance engagement with the story. A limited set of potential answers are provided, speeding up user interaction while teaching the problem-solving process. Performance occurs before competence, in that users complete the process before reviewing it afterwards. Choosing a less than optimal solution does not lead to failure though, and instead, the player is allowed to experience the consequence but encouraged to try a different solution next time.

3.7. ReLate Island – interpersonal skills

On the ReLate island, a range of communication skills are learned by playing through a series of youth-oriented vignettes that feature a difficult conversation or negotiation with another character. Interpersonal skills are of particular importance for young people, as ‘fitting in’ and affiliating with peers is a key challenge of adolescent development (Christie and Viner, 2005). The practice of positive communication has widespread impacts on various health outcomes being protective against bullying and antisocial activity, enhancing social skills, as well as promoting confidence, socialisation and well-being (Federica Sancassiani et al., 2018). In this module the player, represented by their avatar, makes choices about how to behave in a given situation and faces consequences related to this. Poor choices lead to increasing tension and conflict in the relationship, and cumulatively these can lead to the game restarting. Positive communication wins the game and allows the player to progress through levels. Listening skills, assertiveness, negotiation and general social skills are progressively covered. Visual aids (emoji symbols) reduce cognitive load and convey emotional reactions in an efficient and recognisable way that increases interest in the options. Options often only become available if the user is calm (e.g. chooses a ‘timeout’ or a relaxation strategy), promoting healthy mood states and teaching that certain things are only available depending on the consequences. The user is able to try risky social approaches and fail safely without real social costs.

4. Conclusions

We have described the approach we took in the development of Quest – Te Whitianga, a modular mobile application that uses gamification throughout to engage young people in online CBT. The process involved iterative co-design with NZ European, Māori and Pasifika adolescents and with a software development company.

Fortnightly sprints with the software company combined with successive feedback from young people proved an excellent way of obtaining input from the different groups. As the process progressed, engaging a more tightly defined group of users familiar with the developing app, was more productive, saving time on orientation to the developing app and the feedback process. Those young people who were more enthusiastic about the process remained involved and tended to be more creative providing useful feedback more efficiently.

We employed gamification for two reasons. Firstly, we used it to increase engagement with the tool i.e. to encourage repeated and meaningful use, for example through the use of points, badges, progress and use of narrative. Secondly, we gamified various aspects of the selected therapeutic techniques to scaffold the learning of skills and make it more immersive and fun. These features are described in the Results and discussion section and summarised in Table 1. Few existing CBT apps incorporate the same extent or range of gamification that we have employed in Quest - Te Whitianga. For example a study reviewing 61 different intervention programs found that almost all of them (58) utilised just one gamification feature and none had greater than three features (Brown et al., 2016). In most cCBT, the gamification mechanisms are minimal in number and in scope, for example, the most common game mechanics used in eHealth in general are rewards and feedback (Sardi et al., 2017b).

Although promoted, it is not yet established as to whether gamification has a positive effect on engagement with mental health apps (Brown et al., 2016). One study compared engagement between a gamified and non-gamified version of the SmartCAT intervention finding increased use and increased time (in minutes) spent on the app (Pramana et al., 2018). Predicting real-world engagement is difficult, although the quality of the user experience is key; better product quality for visual design, user engagement, content for attributes and therapeutic alliance is positively correlated with real-world usage of mobile apps (Baumel and Kane, 2018).

4.1. Strengths of our approach

We employed a number of strategies we believed would lead to an improved product. This included involving young people throughout co-design process, employing an experienced game designer and working iteratively throughout to improve on the product. We learned that young people may not always be prepared to provide critical feedback and their positive feedback does not necessarily translate to engagement or use. ‘Think aloud’ protocol interviews, where young people play through the app while being observed and asked questions was useful in these cases, as the young person, while immersed in the experience of playing on the app, was less self-conscious about offending the investigators or saying the wrong thing.

In New Zealand, where there are disparities in mental health and well-being for Māori and Pasifika communities, working cross-culturally has been an important way to ensure the app is acceptable and safe for these groups. Our team included Māori and Pasifika researchers and advisors and our user groups were chosen to ensure a strong Māori and Pasifika voice.

4.2. Limitations of our approach

One of the challenges for gamification is how to personalise the experience so that it is directly relevant to the individual. In a therapeutic context, providing general advice is seldom effective unless it is directly applicable. For example, in brief substance use interventions, advice is provided only on topics that the person has identified (usually through some kind of screening test) as relevant to them (Stockings et al., 2016). This is based on a direct contact with the therapist so that any learning goals can be adapted to the young person's lived experience. In Quest – Te Whitianga, customisable avatars, entry of personal gratitude diary entries, and choice of activities in the activity planning module offer some personalisation, however the game provides the same advice and teaches the same skills to all users and this remains a limitation of the app.

There are concerns about the potentially addictive qualities of gaming and its potential to cause disorder (Paulus et al., 2018). Numerous studies warn about the potential negative impacts of gaming, such as increased aggression (Anderson et al., 2010) and decreased psychological well-being (Page et al., 2010). As well there is wide-spread concern about excessive screen time in clinical research and the lay press (Domingues-Montanari, 2017). When designing Quest – Te Whitianga we were careful to avoid functionalities that are associated with more harmful and addictive aspects of gaming such as violence and ‘compulsion loops’. We have limited the duration of the game and included discrete activities to allow for a sense of accomplishment, without strategies to encourage prolonged use at any one sitting.

On the other hand, a range of positive impacts such as enhancing concentration, facilitation of learning and positive behaviour change have also been associated with gaming (Granic et al., 2014). A recent study examining gamification in mental health interventions found 28 that applied gamification, serious games or virtual reality as part of the therapy or used gamification as a way to promote engagement and adherence to treatment (Dias et al., 2018). Putting gamification to the more productive task of engaging people into attainment of CBT skills and to enhance adherence to digital health interventions is increasingly accepted and is becoming a key instrument in the internet interventions sphere.

Quest – Te Whitianga does not incorporate elements that promote social interaction, or shared learning, something for which some young people have expressed a keen interest (Fleming et al., 2019). The expectations of young people are high however, and an interface similar to that which they are used to (such as Instagram or Snapchat) was clearly beyond the scope of the project and too expensive to build. Although social interaction has been included in other interventions, for example the Challenger App for Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) gets users to face increasingly challenging situations, using functionalities such as real-time location awareness and anonymous social interaction (Miloff et al., 2015), the cost of systems that are able to ensure privacy and confidentiality are relatively prohibitive as was a platform that allows moderation. Future updates of Quest – Te Whitianga may look at incorporating some kind of anonymized leaderboard system that would allow players to compare their progress against others.

4.3. Next steps

Our next steps are to conduct a randomised controlled trial of Quest – Te Whitianga with young people seeking help to assess its efficacy, acceptability and measure engagement. The app will then be integrated within a wider HABITs platform (habits.auckland.ac.nz) which is designed to deploy and test a range of digital health interventions, as well as provide links to other avenues for help, for example mental health services and primary care.

Acknowledgements

The HABITs research team.

Role of funding source

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) funded the development and testing of Quest – Te Whitianga via the ‘A Better Start – E Tipu e Rea’ National Science Challenge.

References

- Anderson C.A., Shibuya A., Ihori N., Swing E.L., Bushman B.J., Sakamoto A., Rothstein H.R., Saleem M. Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in eastern and western countries: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2010;136:151–173. doi: 10.1037/a0018251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker D., Kazantzis N., Rickwood D., Rickard N. Mental health smartphone apps: review and evidence-based recommendations for future developments. JMIR Mental Health. 2016;3:e7. doi: 10.2196/mental.4984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumel A., Kane J.M. Examining Predictors of Real-World User Engagement with Self-Guided eHealth Interventions: Analysis of Mobile Apps and Websites Using a Novel Dataset. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20(12):e11491. doi: 10.2196/11491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T. International Universities Press; New York: 1976. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Rush A.J., Shaw B.F., Emery G. Guilford Press; New York: 1979. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks F.M., Chester K.L., Smeeton N.C., Spencer N.H. Video gaming in adolescence: factors associated with leisure time use. J. Youth Stud. 2016;19:36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Brown M., O’Neill N., van Woerden H., Eslambolchilar P., Jones M., John A. Gamification and adherence to web-based mental health interventions: a systematic review. JMIR Mental Health. 2016;3 doi: 10.2196/mental.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie D., Viner R. Adolescent development. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2005;330:301–304. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7486.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cugelman B. Gamification: what it is and why it matters to digital health behavior change developers. JMIR Serious Games. 2013;1:e3. doi: 10.2196/games.3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P., de Wit, L., Kleiboer, A., Karyotaki, E. & Ebert, D. D. 2018. Problem-solving therapy for adult depression: an updated meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 48, 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dias L.P.S., Barbosa J.L.V., Vianna H.D. Gamification and serious games in depression care: a systematic mapping study. Telematics Inform. 2018;35:213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Domingues-Montanari S. Clinical and psychological effects of excessive screen time on children. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2017;53:333–338. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’zurilla T.J., Nezu A.M. Springer; New York: 2007. Problem-solving Therapy: A Positive Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D., Zarski A., Christensen H., Stikkelbroek Y., Cuijpers P., Berking M., Riper H. Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekers D., Webster L., Van Straten A., Cuijpers P., Richards D., Gilbody S. Behavioural activation for depression; an update of meta-analysis of effectiveness and sub group analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federica Sancassiani E.P., Arne H., Peter P., Maria Francesca M., Giulia C., Matthias C A., Mauro Giovanni C., Jutta L. Enhancing the emotional and social skills of the youth to promote their wellbeing and positive development: a systematic review of universal school-based randomized controlled trials. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2018;14:21–40. doi: 10.2174/1745017901511010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming T., Bavin L., Lucassen M., Stasiak K., Hopkins S., Merry S. Beyond the trial: systematic review of real-world uptake and engagement with digital self-help interventions for depression, low mood or anxiety. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20:e199. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming T., Merry S., Stasiak K., Hopkins S., Patolo T., Ruru S., Latu M., Shepherd M., Christie G., Goodyear Smith F. The Importance of User Segmentation for Designing Digital Therapy for Adolescent Mental Health: Findings From Scoping Processes. JMIR Ment. Health. 2019;6(5):e12656. doi: 10.2196/12656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming T.M., Cheek C., Merry S.N., Thabrew H., Bridgman H., Stasiak K., Shepherd M., Perry Y., Hetrick S. Serious games for the treatment or prevention of depression: a systematic review/Juegos serios para el tratamiento o la prevención de la depresión: una revisión sistemática. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clinica. 2014;19:227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming T.M., De Beurs D., Khazaal Y., Gaggioli A., Riva G., Botella C., Baños R.M., Aschieri F., Bavin L.M., Kleiboer A., Merry S., Lau H.M., Riper H. Maximizing the impact of e-therapy and serious gaming: time for a paradigm shift. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2016;7:65. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist. 2001;56:218–226. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhards S.A.H., Abma T.A., Arntz A., De Graaf L.E., Evers S.M.A.A., Huibers M.J.H., Widdershoven G.A.M. Improving adherence and effectiveness of computerised cognitive behavioural therapy without support for depression: a qualitative study on patient experiences. J. Affect. Disord. 2011;129:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh D.H., Ang R.P., Tan H.C. Strategies for designing effective psychotherapeutic gaming interventions for children and adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008;24:2217–2235. [Google Scholar]

- Granic I., Lobel A., Engels R.C. The benefits of playing video games. Am Psychol. 2014;69:66–78. doi: 10.1037/a0034857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger D., Padesky C.A. Guilford Press; New York: 1995. Mind over Mood. [Google Scholar]

- Grist R., Croker A., Denne M., Stallard P. Technology Delivered Interventions for Depression and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2018;1 doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0271-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C., Strosahl K.D., Wilson K.G. The Process and Practice of Mindful Change, New York, UNITED STATES, Guilford Publications; Second Edition: 2011. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Hilvert-Bruce Z., Rossouw P.J., Wong N., Sunderland M., Andrews G. Adherence as a determinant of effectiveness of internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety and depressive disorders. Behav. Res. Ther. 2012;50:463–468. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdsworth E., Bowen E., Brown S., Howat D. Client engagement in psychotherapeutic treatment and associations with client characteristics, therapist characteristics, and treatment factors. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014;34:428–450. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguet A., Miller A., Kisely S., Rao S., Saadat N., McGrath P.J. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of internet-delivered behavioral activation. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;235:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson O., Michel T., Andersson G., Paxling B. Experiences of non-adherence to internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy: a qualitative study. Internet Interv. 2015;2:137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J., Lipworth L., Burney R. The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. J. Behav. Med. 1985;8:163–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00845519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzis, N., Whittington, C., Zelencich, L., Kyrios, M., Norton, P. J. & Hofmann, S. G. 2016. Quantity and quality of homework compliance: a meta-analysis of relations with outcome in cognitive behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy, 47, 755–772. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Khazaal Y., Favrod J., Sort A., Borgeat F., Bouchard S. Editorial: computers and games for mental health and well-being. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2018;9:141. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-S., Kim E.J. Effects of relaxation therapy on anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018;32:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauricella A.R., Cingel D.P., Blackwell C., Wartella E., Conway A. The mobile generation: youth and adolescent ownership and use of new media. Communication Research Reports. 2014;31:357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Ly K.H., Janni E., Wrede R., Sedem M., Donker T., Carlbring P., Andersson G. Experiences of a guided smartphone-based behavioral activation therapy for depression: a qualitative study. Internet Interv. 2015;2:60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh T. Serious games continuum: between games for purpose and experiential environments for purpose. Entertainment Computing. 2011;2:61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mccullough M.E., Tsang J., Emmons R.A. Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004;86:295–309. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry S.N., Stasiak K., Shepherd M., Frampton C., Fleming T., Lucassen M.F. The effectiveness of SPARX, a computerised self help intervention for adolescents seeking help for depression: randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2012;344 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.S., Cafazzo J.A., Seto E. A game plan: gamification design principles in mHealth applications for chronic disease management. Health Informatics Journal. 2014;22:184–193. doi: 10.1177/1460458214537511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miloff A., Marklund A., Carlbring P. The challenger app for social anxiety disorder: new advances in mobile psychological treatment. Internet Interv. 2015;2:382–391. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr D., Weingardt K., Reddy M., Schueller S. Three problems with current digital mental health research…and three things we can do about them. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017;68:427–429. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morschheuser B., Hassan L., Werder K., Hamari J. How to design gamification? A method for engineering gamified software. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2018;95:219–237. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhoff C.C., Schaefer C. Effects of laughing, smiling, and howling on mood. Psychological Reports. 2002;91:1079–1080. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.91.3f.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page A.S., Cooper A.R., Griew P., Jago R. Children’s screen viewing is related to psychological difficulties irrespective of physical activity. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1011–e1017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus F.W., Ohmann S., Gontard A.V., Popow C. Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2018;60:645–659. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennant M.E., Loucas C.E., Whittington C., Creswell C., Fonagy P., Fuggle P., Kelvin R., Naqvi S., Stockton S., Kendall T. Computerised therapies for anxiety and depression in children and young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2015;67:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramana G., Parmanto B., Lomas J., Lindhiem O., Kendall P.C., Silk J. Using mobile health gamification to facilitate cognitive behavioral therapy skills practice in child anxiety treatment: open clinical trial. JMIR Serious Games. 2018;6:e9. doi: 10.2196/games.8902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratap A., Renn B.N., Volponi J., Mooney S.D., Gazzaley A., Arean P.A., Anguera J.A. Using Mobile apps to assess and treat depression in Hispanic and Latino populations: fully remote randomized clinical trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20 doi: 10.2196/10130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardi L., Idri A., Fernandez-Aleman J.L. A systematic review of gamification in e-Health. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017;71:31–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardi L., Idri A., Fernández-Alemán J.L. A systematic review of gamification in e-Health. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017;71:31–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage C., Hindle R., Meyer L.H., Hynds A., Penetito W., Sleeter C.E. Culturally responsive pedagogies in the classroom: indigenous student experiences across the curriculum. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2011;39 283–198. [Google Scholar]

- Seaborn K., Fels D.I. Gamification in theory and action: a survey. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 2015;74:14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan N.F., Kenealy T.W., Connolly M.J., Mahony F., Barber P.A., Boyd M.A., Carswell P., Clinton J., Devlin G., Doughty R., Dyall L., Kerse N., Kolbe J., Lawrenson R., Moffitt A. Health equity in the New Zealand health care system: a national survey. Int. J. Equity Health. 2011;10:45. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-10-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih Ying G., Titov N., Andrews G. Acceptability of internet treatment of anxiety and depression. Australasian Psychiatry. 2011;19:259–264. doi: 10.3109/10398562.2011.562295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasiak K., Merry S. E-therapy. Using computer and mobile technologies in treatment. In: Rey J.M., editor. IACAPAP e-Textbook of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions; Geneva: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson J.N., Jibb L.A., Nguyen C., Nathan P.C., Maloney A.M., Dupuis L.L., Gerstle J.T., Alman B., Hopyan S., Strahlendorf C., Portwine C., Johnston D.L., Orr M. Development and testing of a multidimensional iPhone pain assessment application for adolescents with cancer. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013;15:e51. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockings E., Hall W.D., Lynskey M., Morley K.I., Reavley N., Strang J., Patton G., Degenhardt L. Prevention, early intervention, harm reduction, and treatment of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:280–296. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szigethy, E., Weisz, J. R. & Findling, R. L. (eds.) 2012. Cognitive-behavior therapy for children and adolescents: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Tarrega S., Castro-Carreras L., Fernandez-Aranda F., Granero R., Giner-Bartolome C., Aymami N., Gomez-Pena M., Santamaria J.J., Forcano L., Steward T., Menchon J.M., Jimenez-Murcia S. 2015. A Serious Videogame as an Additional Therapy Tool for Training Emotional Regulation and Impulsivity Control in Severe Gambling Disorder. (Frontiers in Psychology) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torous J., Powell A.C. Current research and trends in the use of smartphone applications for mood disorders. Internet Interv. 2015;2:169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Wood A.M., Froh J.J., Geraghty A.W.A. Gratitude and well-being: a review and theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010;30:890–905. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]