Abstract

Background

Low-dose azithromycin is an effective therapy for persistent asthma; however, its benefit in severe asthma is not defined.

Methods

Participants with severe asthma were identified from the AMAZES randomised, placebo-controlled trial of long-term (48 weeks) low-dose azithromycin. Participants who met one of the following severe asthma definitions were included: 1) Global Initiative for Asthma step 4 treatment with poor asthma control (asthma control questionnaire score ≥0.75); 2) International Severe Asthma Registry definition; 3) American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society severe asthma definitions. The rate of total exacerbations was calculated for each subgroup and efficacy of azithromycin compared with placebo. Asthma-related quality of life was assessed before and after treatment along with adverse effects.

Results

Azithromycin significantly reduced asthma exacerbations in each group. In patients meeting the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society task force definition of severe asthma (n=211), the rate of exacerbations with treatment was 1.2 per person-year, which was significantly less than for placebo (2.01 per person-year), giving an incidence rate ratio (95% CI) of 0.63 (0.41, 0.96). The proportion of participants experiencing at least one asthma exacerbation was reduced by azithromycin from 64% to 49% (p=0.021). A similar beneficial treatment effect was seen in participants poorly controlled with Global Initiative for Asthma step 4 treatment and those with International Severe Asthma Registry-defined severe asthma. Azithromycin also significantly improved the quality of life in severe asthma (p<0.05). Treatment was well tolerated, with gastrointestinal symptoms being the main adverse effect.

Conclusion

Long-term, low-dose azithromycin reduced asthma exacerbations and improved the quality of life in patients with severe asthma, regardless of how this was defined. These data support the addition of azithromycin as a treatment option for patients with severe asthma.

Short abstract

Low-dose azithromycin is effective therapy for persistent asthma. AMAZES supports AZM as a treatment option for patients with severe asthma. Long-term, low-dose AZM reduces asthma exacerbations and improves quality of life in patients with severe asthma. http://bit.ly/2LWyjYz

Introduction

Severe asthma is a high-cost, high-burden disease that affects between 3% and 10% of people with asthma [1–3]. It is characterised by persistent poor symptom control and/or disease exacerbations that occur despite maximal therapy with inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) and long-acting bronchodilators. Although severe asthma is uncommon, because of the high disease burden it accounts for up to 50% of healthcare costs from asthma, and per-patient costs can be greater than other chronic diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [4]. New therapies have been introduced to address this disease burden in severe asthma and include monoclonal antibodies that target a subgroup with eosinophilic disease. However, there is an ongoing need for additional therapies for severe asthma, especially for noneosinophilic subtypes and for the residual exacerbation burden in eosinophilic disease.

Low-dose azithromycin (AZM) is an effective therapy for persistent asthma [5, 6]. It led to a 40% reduction in severe asthma exacerbations, and a similar reduction in respiratory tract infections, when adults with symptomatic persistent asthma, despite maintenance inhaled asthma therapy, received AZM 500 mg orally, three times per week, for 48 weeks [6]. AZM is effective in both eosinophilic and noneosinophilic forms of asthma. The mechanism of this effect is not yet established and may involve antibiotic and/or immunomodulatory mechanisms [7]. The treatment is well tolerated, but because of the potential for individual and community antibiotic resistance, concern remains regarding where to place AZM in current practice. Specific questions relate to the efficacy of AZM in severe asthma and the benefit in noneosinophilic phenotypes of the disease.

Current asthma therapy follows a stepwise approach. Treatment options for patients who are symptomatic on ICSs and long-acting β agonists (LABAs) include higher dose ICSs, maintenance low-dose oral corticosteroids (OCSs), long-acting muscarinic agents (LAMAs), eosinophil targeted monoclonal antibody therapy and bronchial thermoplasty. Low-dose AZM could potentially be added to this list. The AMAZES trial which demonstrated efficacy of AZM in persistent asthma, also included patients with severe asthma, which means there is an opportunity to examine the efficacy of AZM in severe asthma in order to inform where AZM could be placed in the treatment options that are available for patients with severe asthma.

In this secondary analysis of the AMAZES trial, we sought to describe the effect of AZM in different severe asthma subgroups in order to further inform treatment decisions. The subgroups were: 1) patients with symptomatic asthma on Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) step 4 therapy; 2) patients meeting the International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR) [8] definition of severe asthma; and 3) patients meeting the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) severe asthma task force definition [2]. We hypothesised that AZM would be beneficial in each of these subgroups.

Methods

Clinical method

We investigated the effect of low-dose AZM in severe asthma by conducting a subgroup analysis of a randomised control trial (RCT) of low-dose AZM in asthma. The AMAZES study [6] was a double-blind placebo-controlled trial where 420 adults with persistent symptomatic asthma, despite the current use of ICSs and long-acting bronchodilators, and who had no hearing impairment or prolongation of the corrected QT interval, were randomised to receive 500 mg of AZM three times per week or identical placebo for 48 weeks. Asthma exacerbations were recorded as the primary study outcome [6]. Severe exacerbations were defined as a worsening of asthma symptoms that led to one of the following: 1) ≥3 days of systemic corticosteroid treatment ≥10 mg·day−1 of prednisone or equivalent or a temporary increase in a stable OCS maintenance dosage of ≥10 mg·day−1 for ≥3 days; 2) an asthma-specific hospitalisation; or 3) an emergency department visit requiring systemic corticosteroids. Moderate exacerbations were defined as any temporary increase in ICSs and/or antibiotics in conjunction with a deterioration in asthma symptoms (change in asthma control questionnaire (ACQ), Δ ACQ6 ≥ 0.5 or increased diary symptom score) or any increase in β2-agonist use for ≥2 days, or an emergency department visit not requiring systemic corticosteroids.

Asthma quality of life was assessed at randomisation and at the end of treatment using a validated questionnaire, the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) [9]. Adverse events were assessed at each study visit. The inflammatory phenotype was assessed using induced sputum, or if not available, blood eosinophils. Noneosinophilic asthma was defined using baseline sputum eosinophils <3% or a blood eosinophil count <300 cells·mL−1. The trial was approved by the institutional ethics committees and registered at the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, number 12609000197235. All patients provided written informed consent.

Definition of severe asthma

Severe asthma was defined as: 1) GINA step 4 treatment with poor asthma control (ACQ score ≥0.75); 2) ISAR definitions of asthma on GINA step 4 or on GINA step 5 treatment [8]; or 3) ATS/ERS severe asthma task force criteria (high-dose ICS plus a second controller and/or systemic corticosteroids) [2].

Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Total asthma exacerbations for each subgroup were analysed using a negative binomial regression with the length of intervention treatment included as an offset and adjustment for clustering for study site. An interaction term for subgroup and treatment was included in each model. The estimated treatment effect (i.e. the incidence rate ratio (IRR) of AZM versus placebo), corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and a two-sided p-value for the IRR were calculated. Exacerbation rates were calculated as the total number of exacerbations per person divided by the number of days of follow-up, multiplied by 365 and expressed as exacerbations per person-year. The proportion of participants experiencing ≥1 exacerbation was compared using a Chi-squared test. End of treatment AQLQ scores were compared between groups using ANOVA adjusted for baseline measurement, phenotype and phenotype–treatment interactions. A p-value <0·05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

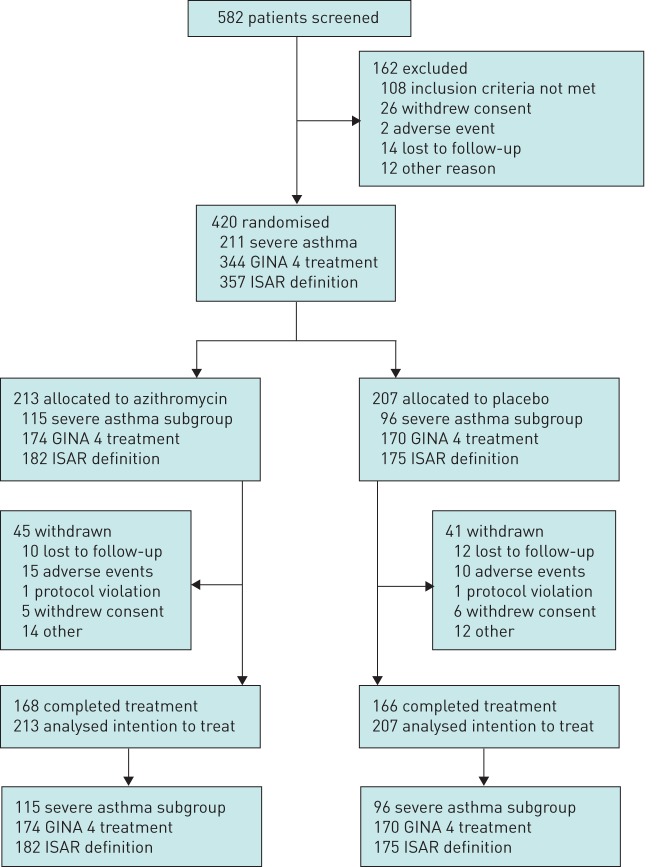

Overall, 420 patients were randomly assigned from a total of 582 patients screened for participation, from June 12, 2009 to January 31, 2015. A total of 213 patients (51%) were allocated to AZM treatment and 207 (49%) to placebo. The trial was completed by 334 (80%) patients, with similar numbers of trial withdrawals in each group (figure 1) [6]. There were 211 patients with severe asthma (ATS/ERS), 344 with GINA step-4 treatment who were poorly controlled, and 357 with ISAR-defined severe asthma (figure 2). Participant characteristics for the ATS/ERS severe asthma subgroup are shown in table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Trial profile. GINA: Global Initiative for Asthma; ISAR: International Severe Asthma Registry.

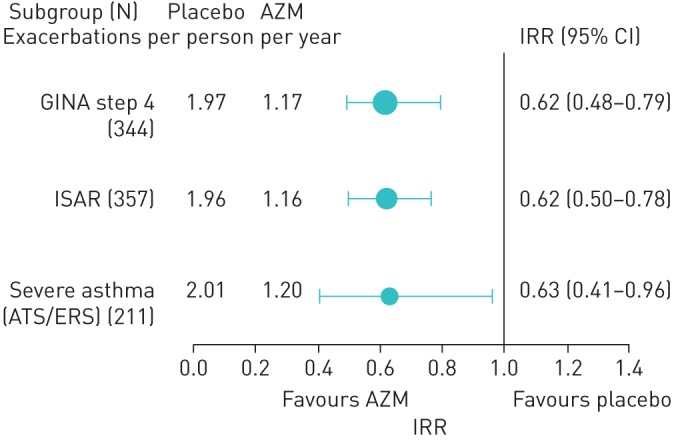

FIGURE 2.

Effect of add-on azithromycin treatment on asthma exacerbations according to subgroup analyses. Severe asthma (ATS/ERS): ≥1000 µg of fluticasone equivalent inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting β agonist combination. No significant interaction was present between subgroup and treatment. AZM: azithromycin; IRR: incidence rate ratio; GINA: Global Initiative for Asthma; ATS: American Thoracic Society; ERS: European Respiratory Society; ISAR: International Severe Asthma Registry.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics for severe asthma using the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society task force definition

| Variable | Severe asthma (N=211) |

| Age years | 61.5 (51.5–68.9) |

| Male | 79 (37%) |

| Atopy | 161 (77.8%) |

| Ex-smoker | 86 (40.8%) |

| Smoking history pack-years | 9.0 (2.3–26.0) |

| Asthma history | |

| Asthma duration years | 33.8 (14.8–49.8) |

| ACQ score | 1.7 (1.2–2.3) |

| Oral corticosteroid courses | 1 (1–3), range 0–15 |

| Medications | |

| ICS daily dose BDP equivalent µg·day−1 | 2000 (2000–2000) |

| ICS/LABA | 211 (100%) |

| Leukotriene modifier | 10 (4.8%) |

| Long-acting muscarinic antagonist | 54 (25.7%) |

| Theophylline | 8 (3.8%) |

| ICS | 17 (8.1%) |

| Oral corticosteroid | 9 (4.3%) |

| Pre-B2 spirometry mean±sd | |

| Pre-B2 FEV1 % predicted | 70.4±18.9 |

| Pre-B2 FVC % predicted | 81±15.5 |

| Pre-B2 FEV1/FVC % | 66.8±11.8 |

| Sputum phenotype (N=168) | |

| Eosinophilic | 73 (43.5%) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) unless otherwise stated. ACQ: Asthma Control Questionnaire; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; BDP: beclomethasone dipropionate; LABA: long-acting β2-agonist; pre-B2: pre-β2-agonist.

Severe asthma

The severe asthma group was a predominantly female population, with a mean age of 61 years and a high prevalence of atopy (78%). They reported a long duration of asthma (33 years), poor symptom control (ACQ 1.67), and moderate airflow obstruction (forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) 70% predicted) despite therapy with high-dose ICSs and long-acting bronchodilators.

AZM significantly reduced asthma exacerbations in severe asthma by all definitions. The rate of asthma exacerbations with placebo (2.01) was significantly reduced to 1.2 exacerbations per person-year with AZM treatment (figure 2). The corresponding IRR (95% CI) was 0.63 (0.41, 0.96). The proportion of participants experiencing at least one asthma exacerbation during treatment was reduced by AZM from 64% to 49% (p=0.021). A similar beneficial treatment effect was seen in participants poorly controlled or uncontrolled with GINA step 4 treatment, and in those with severe asthma defined under ISAR criteria (table 2 and figure 2). AZM treatment also significantly improved asthma-related quality of life in severe asthma (table 3) (p=0.029).

TABLE 2.

Proportion of subjects with severe asthma experiencing an exacerbation

| Placebo | Azithromycin | p-value | |

| Asthma GINA step 4 | 109/170 (64.1%) | 80/174 (46.0%) | 0.001 |

| ISAR# | 112/175 (64.0%) | 84/182 (46.2%) | 0.001 |

| Severe asthma (ATS/ERS)¶ | 62/96 (64.6%) | 56/115 (48.7%) | 0.021 |

GINA: Global Initiative for Asthma; ISAR: International Severe Asthma Registy. #: asthma GINA step 4 and 5; ¶: American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society.

TABLE 3.

Efficacy of azithromycin on quality of life in severe asthma at end of treatment (observed data only)

| Placebo | Azithromycin | p-value# | |

| AQLQ mean score | 5.45 (5.19–5.70)¶ | 5.61 (5.41–5.82)+ | 0.029 |

| AQLQ Activity domain | 5.55 (5.29–5.81)¶ | 5.70 (5.49–5.90)+ | 0.063 |

| AQLQ Symptoms domain | 5.28 (5.02–5.55)§ | 5.49 (5.28–5.71)ƒ | 0.031 |

| AQLQ Emotions domain | 5.37 (5.03–5.71)§ | 5.57 (5.29–5.85)ƒ | 0.017 |

| AQLQ Environment domain | 5.76 (5.49–6.02)§ | 5.68 (5.46–5.91)ƒ | 0.262 |

Data are presented as mean (95% CI) unless otherwise stated. No significant interaction was present. AQLQ: Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. #: ANCOVA adjusted for baseline measurement, phenotype (noneosinophilic/eosinophilic asthma) and phenotype–treatment interaction; ¶: n=95; +: n=113; §: n=96; ƒ: n=115.

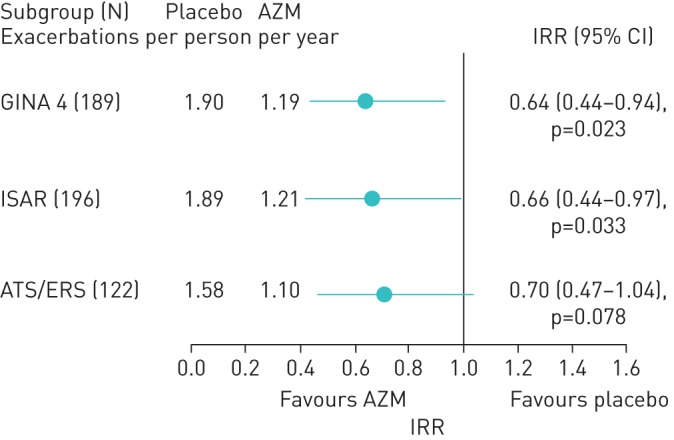

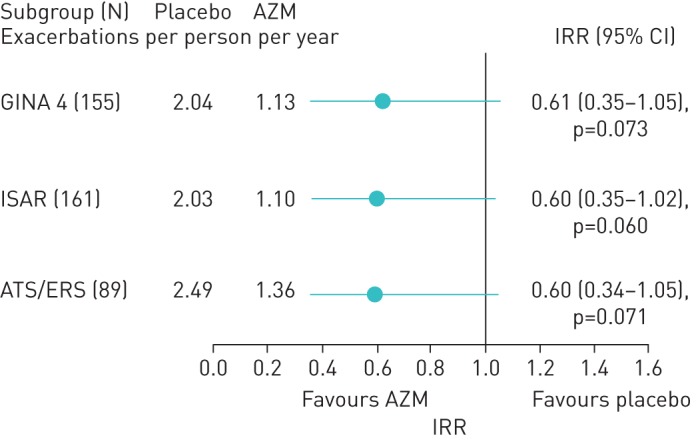

In noneosinophilic asthma, AZM reduced the exacerbation rate in severe asthma defined as GINA step-4 treatment and using ISAR criteria (figure 3). The effect in ATS/ERS defined severe asthma showed a similar trend but was not statistically significant due to insufficient power from the reduced sample size. In severe eosinophilic asthma, AZM significantly reduced the rate of severe exacerbations, when defined using each of the definitions: IRR 0.46, 0.45 and 0.49, for GINA 4, ISAR and ATS/ERS task force-defined severe asthma, respectively, all p<0.05. The effect size for total exacerbations was clinically significant (IRR 0.60) but failed to reach statistical significance (figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Total exacerbations in noneosinophilic severe asthma American Thoracic Society (ATS) criteria: high-dose inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) (≥1000 µg fluticasone and LABA combination). AZM: azithromycin; IRR: incidence rate ratio; GINA: Global Initiative for Asthma; ISAR: International Severe Asthma Registry; ERS: European Respiratory Society.

FIGURE 4.

Total exacerbations in severe eosinophilic asthma. AZM: azithromycin; IRR: incidence rate ratio; GINA: Global Initiative for Asthma; ISAR: International Severe Asthma Registry; ATS: American Thoracic Society; ERS: European Respiratory Society.

Adverse effects

The rate of adverse events was similar in both treatment groups (table 4). In the AZM group there were 7 (6.1%) participants who withdrew from the study due to an adverse event, whereas in the placebo group there were 7 (7.3%) participants who withdrew due to an adverse event. Diarrhoea was more common with AZM, occurring in 41 (35.7%) of AZM-treated participants, compared with 22 (22.9%) of placebo-treated patients. Diarrhoea was managed by temporary dose adjustment and did not result in treatment withdrawal.

TABLE 4.

Adverse events in the AMAZES severe asthma subset

| Placebo (N=96) | Azithromycin (N=115) | |

| Serious adverse events | 15/13 (13.5%) | 22/14 (12.2%) |

| Cardiac | 1/1 (1.0%) | 2/2 (1.7%) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 4/3 (3.1%) | 4/4 (3.5%) |

| Other health issue | 5/4 (4.2%) | 9/3 (2.6%) |

| Possible infectious serious adverse event | 5/5 (5.2%) | 5/3 (2.6%) |

| Events per person | ||

| No events | 83 (86.5%) | 101 (87.8%) |

| 1 event | 12 (12.5%) | 10 (8.7%) |

| 2 events | 0 | 1 (0.9%) |

| 3 events | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (1.7%) |

| 4 events | 0 | 1 (0.9%) |

| Study withdrawal (treatment discontinuation due to adverse event) | 7 (7.3%) | 7 (6.1%) |

| Treatment-related adverse events | ||

| Nausea | 6 (6.3%) | 21 (18.3%) |

| Diarrhoea | 22 (22.9%) | 41 (35.7%) |

| Abdominal pain | 16 (16.7%) | 24 (20.9%) |

| Other gastrointestinal | 2 (2.1%) | 5 (4.4%) |

| Headache | 2 (2.1%) | 3 (2.6%) |

| Vertigo | 0 | 1 (0.9%) |

| Tinnitus | 1 (1.0%) | 0 |

| Hearing loss | 4 (10.5%) | 4 (6.8%) |

| High liver function tests results | 2 (2.1%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Oral thrush | 1 (1.0%) | 4 (3.5%) |

| Allergy | 0 | 1 (0.9%) |

| Rash | 7 (7.3%) | 4 (3.5%) |

| QTc prolongation | 1 (2.6%) | 3 (5.1%) |

| Other adverse event | 17 (17.7%) | 22 (19.1%) |

Data are presented as n events/n (%) people, unless otherwise stated. QTc: corrected QT interval.

Discussion

We report that long-term low-dose AZM is effective in patients with severe asthma. These patients experienced a significant reduction in asthma exacerbations with AZM therapy and improved health status. The effect was consistent across different definitions of severe asthma, and also in severe noneosinophilic and eosinophilic asthma. These data support the addition of AZM as a treatment option for patients with severe asthma.

This study represents the largest RCT to assess the effect of AZM in severe asthma. The positive effect in noneosinophilic asthma is consistent with prior reports, such as the AZISAST study that reported a positive effect of AZM for 6 months in noneosinophilic severe asthma [5] and a smaller trial that showed a benefit of 4 weeks of clarithromycin on asthma-related quality of life in noneosinophilic severe asthma [10]. A retrospective observational trial also reported a positive effect of AZM in severe asthma [11]. Collectively, these data provide evidence that AZM is effective in severe asthma, when defined using several widely accepted definitions, and also in severe noneosinophilic asthma. The benefits are a reduction in asthma exacerbations and an improvement in quality of life.

The existing treatment options for patients with severe asthma include LAMAs, biologics, maintenance OCSs and bronchial thermoplasty. Each of these options has pros and cons. AZM could precede maintenance OCS as it is less toxic. The main benefit of biologics in severe asthma is a reduction in severe asthma exacerbations, and both AZM and anti-eosinophilic biologics reduce severe asthma exacerbations by a similar degree. AZM may be more cost-effective than biologics and in addition, is effective in noneosinophilic asthma, whereas current biologics are restricted to eosinophilic or allergic disease. However, AZM may take longer to produce an effect, and an effect on hospital admissions is not yet demonstrated with AZM. If there is a history of infective bronchitis, AZM is effective where other options are not. Overall, these considerations support the early use of AZM as add-on therapy in severe asthma, and the differential effects can be used to position AZM in particular patient groups, such as those with noneosinophilic severe asthma, and severe asthma with frequent infective bronchitis.

Severe asthma is defined in several ways. The key elements in each of the definitions are evidence of poor control despite use of high intensity asthma therapy, which recognises the disease as being relatively refractory to conventional asthma therapy. The main differences between the definitions relate to the specified treatment intensity, in particular the ICS dose used. Patients receiving at least GINA step-4 treatment, which is a high-dose ICS and LABA, comprise the definitions based on GINA treatment levels and the ISAR definition. Using these criteria, GINA step-4 ICS therapy equates to >1000 µg·d−1 of beclomethasone dipropionate (CFC) or >500 µg·day−1 of fluticasone. The ATS/ERS severe asthma task force definition is “asthma which requires treatment with guidelines suggested medications for GINA steps 4–5 (high-dose ICS and LABA or leukotriene modifier/theophylline)” [2]. There is some variation in the specified ICS dose in the different definitions of severe asthma, both between different versions of the task force document, and with the GINA guidelines. The initial ATS/ERS task force document specified high-dose ICSs as >1200 µg·day−1 of beclomethasone equivalent CFC. This was subsequently revised to ≥2000 µg·day−1 of beclomethasone equivalent CFC MDI. In this paper, we evaluated the effect of AZM in severe asthma, defined using each of the available definitions and found that AZM was effective in reducing asthma exacerbations in each of the different ways that severe asthma was defined.

Macrolide antibiotics have both anti-infective and anti-inflammatory effects [7]. Corticosteroid insensitivity is a feature of severe asthma, and in dynamic model systems, macrolides are effective in both steroid sensitive (eosinophilic) and steroid insensitive (noneosinophilic) forms of the disease, which is consistent with the results of the AMAZES trial [12]. There was not an obvious effect on sputum granulocytes in the AMAZES trial, and other possibilities for the treatment effect of AZM include effects on mucus production, macrophage function and antimicrobial effects. AZM also has promotility effects in the gastrointestinal tract. It is hypothesised that these effects could reduce recurrent aspiration and this may explain the beneficial effect of AZM on exacerbations.

The key effect of AZM was to reduce asthma exacerbations. The molecular mechanisms of these events are an area of ongoing study. Airway gene expression for eosinophil and neutrophil genes is associated with increased exacerbation frequency [13] but this effect does not appear to be modified by AZM. Other potential mechanisms include activation of the interleukin-17 pathway, activation of epithelial interleukin-6 pathways [14, 15] or improved bacterial clearance.

This study reports the results of an RCT of AZM in asthma. The main limitation is that the analysis is a subgroup analysis of a previously reported study. Such analyses can be subject to bias; however, this seems unlikely as the results are in agreement with the main study results, are consistent across different definitions of severe asthma, and are consistent with other publications. A further limitation relates to a reduction in sample size seen when performing analyses on subgroups, and this can preclude identification of a statistically significant effect.

In conclusion, long-term low-dose oral AZM is effective in severe asthma. The treatment is well tolerated and expected benefits are a significant reduction in severe exacerbations and improved quality of life. AZM could be used before maintenance OCS and in severe noneosinophilic asthma. The order in which it is best to add in macrolide therapy still requires elucidation, especially in relation to the sequence of treatments added to ICSs and LABAs when patients are persistently symptomatic.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00056-2019.SUPPLEMENT (916.2KB, pdf)

Footnotes

This article has supplementary material available from openres.ersjournals.com.

This study is registered at www.anzctr.org.au with identifier number ANZCTR12609000197235. Individual participant data will not be made available. Other data and the study protocol will be available beginning 6 months and ending 2 years following data publication. These data may be shared with investigators whose proposed use of the data has been approved by independent review committees (learned intermediary) identified for this purpose, with the data only being used for analyses that achieve the aims in the approved protocol. Proposals for data access may be submitted up to 36 months following article publication. After 36 months, the data will be available in our university's data system but without investigator support other than deposited metadata.

Conflict of interest: P.G. Gibson reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and Sanofi during the conduct of the study.

Conflict of interest: I.A. Yang reports grants from the NHMRC during the conduct of the study.

Conflict of interest: J.W. Upham reports a research grant, advisory boards, speaker fees and conference travel from Astra Zeneca, advisory boards from GSK, advisory boards, speaker fees and conference travel from Novartis, speaker fees and conference travel from Boehringer Ingelheim, and conference travel from Menarini, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: P.N. Reynolds reports grants from National Health and Medical Research Council, and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study.

Conflict of interest: S. Hodge has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A.L. James has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Jenkins reports grants and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees and nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, and personal fees from Novartis, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: M.J. Peters has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G.B. Marks reports grants and nonfinancial support from GSK Australia, grants and other from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: M. Baraket has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H.P. Powell has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J.L. Simpson has nothing to disclose.

Support statement: This study was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council grant 569246. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Hekking PP, Wener RR, Amelink M, et al. The prevalence of severe refractory asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 135: 896–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 343–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Bulow A, Kriegbaum M, Backer V, et al. The prevalence of severe asthma and low asthma control among Danish adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014; 2: 759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Israel E, Reddel HK. Severe and difficult-to-treat asthma in adults. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 965–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brusselle GG, Vanderstichele C, Jordens P, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations in severe asthma (AZISAST): a multicentre randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Thorax 2013; 68: 322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 390: 659–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fricker M, Gibson PG. Macrophage dysfunction in the pathogenesis and treatment of asthma. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulathsinhala L, Eleangovan N, Heaney LG, et al. Development of the International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR): a modified Delphi study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7: 578–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Epstein RS, et al. Evaluation of impairment of health-related quality of life in asthma: development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Thorax 1992; 47: 76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson JL, Powell H, Boyle MJ, et al. Clarithromycin targets neutrophilic airway inflammation in refractory asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 177: 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coeman M, van Durme Y, Bauters F, et al. Neomacrolides in the treatment of patients with severe asthma and/or bronchiectasis: a retrospective observational study. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2011; 5: 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Essilfie AT, Horvat JC, Kim RY, et al. Macrolide therapy suppresses key features of experimental steroid-sensitive and steroid-insensitive asthma. Thorax 2015; 70: 458–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fricker M, Gibson PG, Powell H, et al. A sputum 6-gene signature predicts future exacerbations of poorly controlled asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 144: 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jevnikar Z, Ostling J, Ax E, et al. Epithelial IL-6 trans-signaling defines a new asthma phenotype with increased airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 143: 577–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricciardolo FLM, Sorbello V, Folino A, et al. Identification of IL-17F/frequent exacerbator endotype in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140: 395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00056-2019.SUPPLEMENT (916.2KB, pdf)