Abstract

The catalytic, enantioselective N-oxidation of substituted pyridines is described. The approach is predicated on a biomolecule-inspired catalytic cycle wherein high levels of asymmetric induction are provided by aspartic acid-containing peptides as the aspartyl side chain shuttles between free acid and peracid forms. Desymmetrizations of bis(pyridine) substrates bearing a remote pro-stereogenic center substituted with a group capable of hydrogen bonding to the catalyst are demonstrated. Our approach presents a new entry into chiral pyridine frameworks in a heterocycle-rich molecular environment. Representative functionalizations of the enantioenriched pyridine N-oxides further document the utility of this approach. Demonstration of the asymmetric N-oxidation in two venerable drug-like scaffolds, Loratadine and Varenicline, show the likely generality of the method for highly variable and distinct chiral environments, while also revealing that the approach is applicable to both pyridines and 1,4-pyrazines.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Substituted pyridines continue to emerge with high frequency in disclosures of biologically active scaffolds.1 Accordingly, methods for synthesizing differentially substituted analogs are highly coveted.2 Strategies for constructing pyridine-containing molecules in optically enriched form are generally indirect, given the planarity of the heteroaromatic pyridine N-nucleus. Nonetheless, methodologies for achieving “asymmetric”, or enantioselective, syntheses of pyridines are essential given the extant and growing number of pyridine-containing chiral molecules now found in drugs and drug candidates (Fig. 1a).3

Figure 1.

(a) Representative bioactive pyridine-containing compounds. (b) Several conventional strategies to access optically enriched pyridine-containing molecules. (c) Inspiration from enantioselective N-oxidation of tertiary amines. (d) The method reported herein for enantioselective N-oxidation of pyridines and subsequent derivatization.

Enantioselective syntheses of pyridines are often predicated on using building blocks containing stereogenic centers (Fig. 1b, i),4 or appending chiral auxiliaries to the pyridine as a substituent (Fig. 1b, ii).5 Using asymmetric catalysts, chiral pyridines can be accessed through the coupling of chiral fragments (Fig. 1b, iii)6 or by performing an asymmetric catalytic reaction on a pyridine with a prochiral element (Fig. 1b, iv).7 Particularly inspiring for the present report, enantioselective N-oxidation of tertiary amines (Fig. 1c) was reported by Sharpless in 1983, wherein chiral Ti-based complexes were employed in stoichiometric quantities to affect kinetic resolution of tertiary amines.8

We now report herein an alternative, unprecedented catalytic pyridine N-oxidation reaction, in which chirality is established via remote asymmetric desymmetrization (Fig. 1d). As described below, the chemistry proceeds with high levels of enantio- and chemoselectivity, and we have also achieved derivatizations of the resulting pyridine N-oxides (Fig. 1d, right) that add to the versatility of the approach for synthesis. In addition, we have extended this chemistry to intriguing, now-venerable classes of bioactive heterocyclic scaffolds (vide infra), which implies generality for this new method.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Our approach required the identification of an appropriate catalytic cycle for pyridine N-oxidation, and the design of a substrate-type that would allow us to interrogate enantioselectivity. For the former, we wondered if a recently explored family of biologically inspired oxidation catalysts might suffice. We have shown, for example, that aspartic acid-containing catalysts exhibit significant prowess as enantioselective epoxidation (Fig. 2a)9 or asymmetric Baeyer–Villiger (BV)10 catalysts that also exert control over migratory aptitude in BV reactions (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, the peptide sequence can control functional group selectivity, selecting olefins (epoxidation) or ketones (BV), even if both are present within the same molecule, overcoming the specter of cross-reactivity (Fig. 2c).11 Moreover, because these catalysts exhibit high chemoselectivity in the presence of electron-rich heterocycles,12 we thought they might have the mechanistic generality to serve as selective pyridine N-oxidation catalysts, as projected in Fig. 1d. Several other designs of catalytic residues for enantioselective pyridine N-oxidation were also considered based on the previous literature.13

Figure 2.

Asp-containing peptide as catalysts for (a) electrophilic epoxidation and (b) nucleophilic Baeyer–Villiger (BV) oxidation. (c) Catalyst-dependent reactivity when olefins and ketones are both present in the molecule.

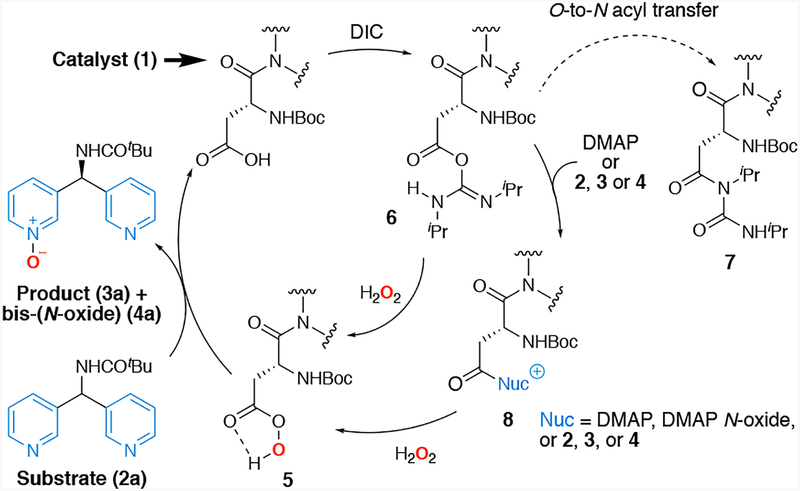

Shown in Scheme 1 is the catalytic cycle we desired to implement for asymmetric pyridine N-oxidation of 2 to 3 using Asp-containing catalysts (1). Overoxidation to form bis(N-oxide) product 4 is also possible, as is a general issue with desymmetrizations wherein double functionalization can occur. Nevertheless, in analogy to epoxidation and BV oxidation, we relied on carbodiimide activation of 1 to chaperone the Asp-containing catalysts to the Asp-based peracid 5.

Scheme 1.

Hypothesis of the catalytic cycle for enantioselective N-oxidation of pyridine substrates.

The desired pyridine N-oxidation then completes the catalytic cycle and regenerates 1. One interesting difference between the presently disclosed pyridine N-oxidation and our prior epoxidation and BV catalytic systems is that in this new application, both the substrate 2 and product 3 can serve as transient co-catalysts for the reaction, preventing deleterious rearrangement of the intermediate O-acyl urea 6 to the catalytically inactive N-acyl urea 7,14 possibly through the formation of intermediates like 8. In our earlier studies, we had deliberately assigned this function to the additive DMAP or DMAP N-oxide. Notably, we observed no particular advantage or disadvantage to the incorporation of extra DMAP on the selectivity in the current studies. In any event, we were pleased to see that with 10 mol% of Boc-Asp-OMe (1a) as the catalyst, 63% yield of 3a could be achieved, albeit in racemic form (Fig. 3b, table, entry 1).

Figure 3.

Screening of peptide catalysts from (a) the one-bead-one-compound (OBOC) library and (b) proline-type β-turn peptides. aThe mono-N-oxide 3a was produced in 63% yield. bInstead of CDCl3, the solvent listed in parentheses was used in this reaction. cPolar solvents included: EtOAc, Et2O, and THF. dThe reaction was performed at 4 °C. Ers were measured according to the eluent order. eAbbreviatiations are specified in the Supporting Information.

We then turned our attention to the critical question of enantioselectivity. Given nonexistent analogy in the literature for the explicit design of chiral catalysts for pyridine N-oxidation, we elected to compare a combinatorial approach to the discovery of a “hit” catalyst to a class of β-turn-biased catalysts we have previously employed for many asymmetric reactions.15 For the combinatorial approach, we applied the one-bead-one-compound (OBOC) library concept.16

Application of this approach (described in the Supporting Information) to the desymmetrization of 2a led to the identification of a number of “hit” catalysts, including 1b and 1c (Fig. 3a). These catalysts delivered 3a with appreciable enantioselectivity under the conditions of the assay (resin-bound 1b, 69.5:30.5 enantiomeric ratio (er); resin-bound 1c, 70:30 er); synthesis and evaluation under homogeneous conditions gave validating results (1b, 75:25 er; 1c, 72:28 er). In parallel, our assessment of β-turn-biased catalysts included a survey of the diastereomers of canonical Boc-Asp-Pro-type tetramers (Fig. 3b, table, entries 2–5),15b, 17 and of these catalysts, 1d delivered 3a with 74:26 er. Thus, we elected to pursue catalysts related to 1d further. Parenthetically, we suspect that any of the three scaffolds in Fig. 3a could in principle be optimized for the selective oxidation of 2a to 3a.

Accordingly, we then turned to the optimization of catalyst 1d, exploring simple variations of side chains and stereochemical configurations at each position of the catalyst. Several illustrative and heuristic substitutions are shown in the table of Fig. 3b. First, the monomeric Asp-derived catalyst 1a noted above delivered the product in racemic form, indicating that some higher-order structure would be necessary for enantioselectivity (Fig. 3b, table, entry 1). Furthermore, the survey of the stereochemical disposition of each residue in the β -turn-biased sequence (entries 2–5) revealed that Boc-D-Asp-D-Pro-Acpc-Phe-OMe (1d) was indeed optimal, delivering the 74:26 er, while other diastereomers gave lower selectivity. Chloroform also emerged as the preferred solvent with catalyst 1d in a preliminary survey (entries 6–7).18 Variation of the i+2 residue generally led to catalysts with lower selectivity (entries 8–9); yet, variation of substituents to the N-terminal side of the peptide sequence led to promising improvements. An N-terminal tert-butyl urea substituent (1j, entry 10) resulted in observation of nearly 80:20 er. Addition of a fifth amino acid residue to the N-terminal side gave further enhancement of er (entries 11–17). Of these catalysts, peptide 1n with a Boc-D-phenylglycine (Boc-D-Phg, entry 15) N-terminal residue delivered 3a with an 86:14 er. Accordingly, we elected to examine this catalyst further with reaction conditions and for studies of substrate scope.

Variations of the reaction parameters impacted the enantioselectivity, but none more profound than the nature of the 6- and 6′-positions of 2. Thus, when 2b was employed, with a methyl group at the 6- and 6′-positions, we observed an increase in the er such that 3b was produced with 92:8 er, and in 71% isolated yield (Table 1, entry 1). Moreover, we discovered that there was a degree of secondary kinetic resolution in the overoxidation of 3b (to give 4b) that led to further er enhancement (entries 2–4). Indeed, 3b was generated with >98:2 er when 1.6 equiv of DIC was employed, albeit with a small sacrifice in yield (55% yield). With this level of enantioselectivity, we turned our attention to the scope and limitations for this new asymmetric process.

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditions for pyridine N-oxidation with peptide 1n performed on 0.05 mmol scale.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | DIC Equiv | Yield 3b [%] | er, 3b | Yield 4b [%] |

| 1 | 1.0 | 71% | 92:8 | 12 |

| 2 | 1.2 | 73% | 93.5:6.5 | 18 |

| 3 | 1.4 | 68% | 96:4 | 30 |

| 4 | 1.6 | 55% | 98.5:1.5 | 45 |

Our explorations of substrates led to the identification of a number of excellent substrates, as well as some that did not work as well. Under optimized conditions (1.5 equiv oxidant, 0.2 M in substrate, 4 °C), 3a was isolated in 75% yield with 87:13 er (Fig. 4a). In addition, quite a few excellent substrates emerged with 6,6’-di-substitution. For example, 3b was isolated in 76% yield with 97:3 er. iso-Pro-pyl-bearing product 3c was also obtained with high er (71% yield, 99:1 er), as was the tert-butyl substituted compound 3d (70% yield, 98.5:1.5 er), albeit requiring a 48 h reaction time in this case. Similarly, the cyclohexyl-bearing substrate 2e was converted to 3e with 99:1 er (69% isolated yield). Aryl-substituted pyridines were also well-tolerated by catalyst 1n, as illustrated by the isolations of 3f (78% yield, 98:2 er), 3g (78% yield, 99:1 er), 3h (74 % yield, 98:2 er) and 3i (79% yield, 96:4 er). Some other more exotic substituents were also promising, as bis(quinoline) 3j was isolated in 79% yield with 97:3 er under these conditions. 6,6′-Bismethoxy-substitution was less tolerated, although 3k was still isolated with 88:12 er and in 67% yield. Altering the position of the pyridyl substituent to 5,5′-dimethylation led to a product with somewhat lower selectivity, as 3l was isolated with 87:13 er and 65% yield. The absolute configuration of N-oxide 3l was determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction, which enabled the assignment of the remaining substrates by analogy.

Figure 4.

Substrate scope of the desymmetrization of bis(pyridine)s with peptide catalyst 1n, with (a) substrates reacting well to excellently and (b) those that reacted with low to no selectivity. Different reaction times are noted in parentheses. For reaction details, see Supplementary Information. Absolute configuration of 3a–3k and 3p–3r were determined by analogy to the single-crystal X ray diffraction of 3l, and the ones of 3m–3o were listed as uncertain.

On the other hand, Fig. 4b depicts several substrates that do not work as well with peptide 1n, including substitution at the 2-position of the pyridine (3m) or when the pyridyl moieties are bridged at the 4-positions (3n). These two cases afforded products that were nearly racemic with catalyst 1n. In addition, compounds related to 3 generally exhibited higher selectivity when the bridging amide group was a secondary pivaloyl amide. When the free N-H group was replaced with N-Me (3o), selectivity was greatly diminished (54:46 er), suggesting that the secondary amide may play a mechanistic role as a hydrogen bond donor. When the pivaloyl group was converted to benzoyl (3p) or acetyl (3q), selectivity was partially restored (84:16 er and 72:28 er, respectively). The Boc-protected substrate 3r was also examined, but delivered the product with a reduced er (60:40 er). It is certainly possible that re-optimization with another catalyst from our library might address these classes in a more selective manner.

While we do not yet know the basis of asymmetric induction in the highly selective variants of these reactions, we are in a position to offer some speculation in analogy to previous studies. In this spirit, the ensemble shown in Fig. 5 presents a schematic drawing in which the activated aspartic peracid catalytic intermediate may interact with the substrate in a manner that is consistent with the identity of the major enantiomer in the (S)-configuration that we observe. This model is predicated on well-precedented conformational analyses for Pro-Acpc peptides,15b, 19 and accommodates the SAR derivable from Fig. 3b and Fig. 4. In this speculative transition state, the peptide adopts a type II′ β-turn conformation in the reactive complex. Hydrogen bonding interactions are envisioned to contribute to catalyst-substrate organization.

Figure 5.

A speculative and heuristic model for the enantiomeric outcome.

The optically enriched pyridine N-oxides emerging from this study also provide a platform for the synthesis of chiral pyridine-containing scaffolds, as demonstrated in Fig. 6. For example, Ph-substituted pyridine N-oxide 3f was permuted to aminopyridine 9, aryloxypyridine 10, and thioether variant 11 under established PyBroP®-based substitution conditions (Fig. 6).20 Parenthetically, the desymmetrized unsubstituted pyridine N-oxide 3a may also be regioselectively diversified. For example, using recrystallized material of 3a (91:9 er), amination delivered 12 in a 15:1 ratio of 2/6 positional regioisomers, while sulfonamidation (13) occurred in a >19:1 ratio of 6/2 positional regioisomers (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Derivatization of (a) enantioenriched 3f via amination, etherification, and thioetherification and (b) 3a through regioselective amination and sulfonamidation.

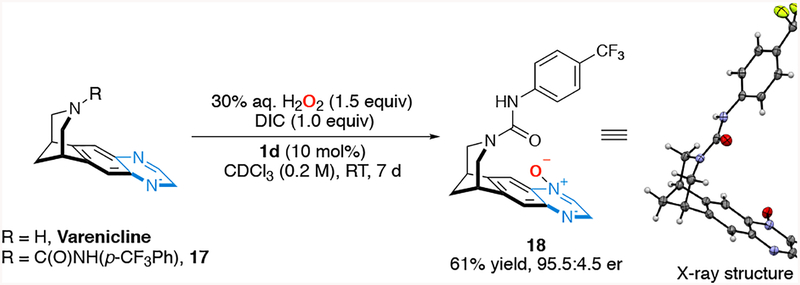

To address the question of whether our approach might be applicable generally, and in genuinely different classes of substrates, we conclude with two exotic and demanding applications in unambiguously drug-like scaffolds. Loratadine,21 the active ingredient in the allergy medicine Claritin®, exhibits unusual stereochemical properties. For example, while Loratadine itself does not exhibit stable enantiomers due to rapid conformational interconversion, compounds like 14 can be isolated with optically purity due to high barriers to racemization of the helically chiral enantiomers (Fig. 7).22 Thus, we wondered whether or not catalytic, enantioselective pyridine N-oxidation of Loratadine derivative 15 could be subjected to dynamic kinetic resolution. Notably, catalyst 1d afforded 16 in 45% yield with 95:5 er (Fig. 7). Pyridine N-oxidation is preferred, although we also observed 30% conversion to the corresponding putative epoxide under these conditions, as assayed by LC/MS (See Supporting Information for details). This result highlights the applicability of this chemistry beyond desymmetrizations. Moreover, we demonstrated that a scaffold related to Varenicline23 may undergo desymmetrization, such that 17 was converted to 18 with catalyst 1d in 61% yield and with 95.5:4.5 er (Fig. 8). This last result suggests the present approach may have generality with respect to other, enantio- and site-selective heteroarene N-oxidations.

Figure 7.

Dynamic kinetic resolution of Loratadine derivative 15.

Figure 8.

Desymmetrization of Varenicline derivative 17.

CONCLUSIONS

We have described a new enantioselective transformation: the catalytic, asymmetric N-oxidation of pyridines employing aspartic acid-derived peracid catalysis. This chemistry not only extends the general utility of this catalytic cycle beyond epoxidation and Baeyer–Villiger oxidations, but also provides strategic access to optically enriched heterocycles in a class of substrates fertile for studies of bioactivity. With efficiency demonstrated for a range of desymmetrizations, heterocycles, and enantioselective derivatization of drug-like scaffolds, we anticipate this approach will be of interest and use in fundamental and applied studies in both process-oriented and discovery-oriented synthetic chemistry settings.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr. Margaret J. Hilton for critical suggestions. We also would like to thank Dr. Brandon Q. Mercado for solving our X-ray crystal structures.

Funding Sources

This work is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health for support (R35 GM132092). S.Y.H. is very grateful to the Swiss National Science Foundation for a postdoctoral fellowship. E.A.S. acknowledges the support of the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental details, characterization, and X-ray crystallographic data (PDF)

X-Ray crystallographic data for compounds 3l (CCDC 1950272), 16 (CCDC 1950546), and 18 (CCDC 1950273) are available free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center.

ABBREVIATIONS

See Supporting Information for details.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Taylor RD; MacCoss M; Lawson ADG “Rings in Drugs” J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 5845–5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vitaku E; Smith DT; Njardarson JT “Analysis of the Structural Diversity, Substitution Patterns, and Frequency of Nitrogen Heterocycles among U.S. FDA Approved Pharmaceuticals” J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 10257–10274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Henry GD “De novo Synthesis of Substituted Pyridines” Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 6043–6061. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hill MD “Recent Strategies for the Synthesis of Pyridine Derivatives” Chem. Eur. J 2010, 16, 12052–12062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).For several representative examples of chiral pyridines in drugs and drug-like molecules, see:; (a) Roecker AJ; Mercer SP; Schreier JD; Cox CD; Fraley ME; Steen JT; Lemaire W; Bruno JG; Harrell CM; Garson SL; Gotter AL; Fox SV; Stevens J; Tannenbaum PL; Prueksaritanont T; Cabalu TD; Cui D; Stellabott J; Hartman GD; Young SD; Winrow CJ; Renger JJ; Coleman PJ “Discovery of 5′′- Chloro-N-[(5,6-dimethoxypyridin-2-yl)methyl]-2,2′:5′,3′′-terpyridine-3′-carboxamide (MK-1064): A Selective Orexin 2 Receptor Antagonist (2-SORA) for the Treatment of Insomnia” ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ding J; Hall DG “Concise Synthesis and Antimalarial Activity of All Four Mefloquine Stereoisomers Using a Highly Enantioselective Catalytic Borylative Alkene Isomerization” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 8069–8073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rastelli EJ; Coltart DM “A Concise and Highly Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (+)-anti- and (−)-syn -Mefloquine Hydrochloride: Definitive Absolute Stereochemical Assignment of the Mefloquines” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 14070–14074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Parton AH; Ali MH; Brookings DC; Brown JA; Ford DJ; Franklin RJ; Langham BJ; Neuss JC; Quincey JR “Quinoline and Quinoxaline Derivatives as Kinase Inhibitors” WO2012/032334 (2012). [Google Scholar]; (e) Brookings DC “8.15 - The Discovery and Development of Seletalisib: A Potent and Selective PI3Kδ Inhibitor for Inflammatory Diseases” In Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry II, Chackalamannil S; Rotella D; Ward SE, Eds. Elsevier: Oxford, 2017; pp 366–407. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Tanyeli C; Akhmedov İM; Işık M “Synthesis of Various Camphor-Based Chiral Pyridine Derivatives” Tetrahedron Lett 2004, 45, 5799–5801. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kuduk SD; DiPardo RM; Chang RK; Ng C; Bock MG “Reversal of Diastereoselection in the Addition of Grignard Reagents to Chiral 2-Pyridyl tert-Butyl (Ellman) Sulfinimines” Tetrahedron Lett 2004, 45, 6641–6643. [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Proctor RSJ; Davis HJ; Phipps RJ “Catalytic Enantioselective Minisci-Type Addition to Heteroarenes” Science 2018, 360, 419–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yin Y; Dai Y; Jia H; Li J; Bu L; Qiao B; Zhao X; Jiang Z “Conjugate Addition–Enantioselective Protonation of N-Aryl Glycines to α-Branched 2-Vinylazaarenes via Cooperative Photoredox and Asymmetric Catalysis” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 6083–6087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cao K; Tan SM; Lee R; Yang S; Jia H; Zhao X; Qiao B; Jiang Z “Catalytic Enantioselective Addition of Prochiral Radicals to Vinylpyridines” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 5437–5443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Tao X; Li W; Ma X; Li X; Fan W; Xie X; Ayad T; Ratovelomanana-Vidal V; Zhang Z “Ruthenium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Hydrogenation of Aryl-Pyridyl Ketones” J. Org. Chem 2012, 77, 612–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Miyano S; Lu LDL; Viti SM; Sharpless KB “Kinetic Rresolution of Racemic β-Hydroxy Amines by Enantioselective N-Oxide Formation” J. Org. Chem 1983, 48, 3608–3611. [Google Scholar]; (b) Miyano S; Lu LDL;Viti SM; Sharpless KB “Kinetic Resolution of Racemic β-Hydroxy Amines by Enantioselective N-Oxide Formation” J. Org. Chem 1985, 50, 4350–4360. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bhadra S; Yamamoto H “Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of N-Chiral Amine Oxides” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 13043–13046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Peris G; Jakobsche CE; Miller SJ “Aspartate-Catalyzed Asymmetric Epoxidation Reactions” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 8710–8711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lichtor PA; Miller SJ “Combinatorial Evolution of Site- and Enantioselective Catalysts for Polyene Epoxidation” Nat. Chem 2012, 4, 990–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Romney DK; Colvin SM; Miller SJ “Catalyst Control over Regio- and Enantioselectivity in Baeyer–Villiger Oxidations of Functionalized Ketones” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 14019–14022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Alford JS; Abascal NC; Shugrue CR; Colvin SM; Romney DK; Miller SJ “Aspartyl Oxidation Catalysts that Dial in Functional Group Selectivity, Along with Regio- and Stereoselectivity” ACS Cent. Sci 2016, 2, 733–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Kolundzic F; Noshi MN; Tjandra M; Movassaghi M; Miller SJ “Chemoselective and Enantioselective Oxidation of Indoles Employing Aspartyl Peptide Catalysts” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 9104–9111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mercado-Marin EV; Garcia-Reynaga P; Romminger S; Pimenta EF; Romney DK; Lodewyk MW; Williams DE; Andersen RJ; Miller SJ; Tantillo DJ; Berlinck RGS; Sarpong R “Total Synthesis and Isolation of Citrinalin and Cyclopiamine Congeners” Nature 2014, 509, 318–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) Limnios D; Kokotos CG “2,2,2-Trifluoroacetophenone as an Organocatalyst for the Oxidation of Tertiary Amines and Azines to N-Oxides” Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20, 559–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dyer RMB; Hahn PL; Hilinski MK “Selective Heteroaryl N-Oxidation of Amine-Containing Molecules” Org. Lett 2018, 20, 2011–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Rebek J; McCready R; Wolf S; Mossman A “New oxidizing agents from the dehydration of hydrogen peroxide” J. Org. Chem 1979, 44, 1485–1493. [Google Scholar]; (b) Greene FD; Kazan J “Preparation of Diacyl Peroxides with N,N’-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide” J. Org. Chem 1963, 28, 2168–2171. [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Metrano AJ; Miller SJ “Peptide-Based Catalysts Reach the Outer Sphere through Remote Desymmetrization and Atroposelectivity” Acc. Chem. Res 2019, 52, 199–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Metrano AJ; Abascal NC; Mercado BQ; Paulson EK; Hurtley AE; Miller SJ “Diversity of Secondary Structure in Catalytic Peptides with β-Turn-Biased Sequences” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 492–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Lam KS; Lebl M; Krchnák V “The “One-Bead-One-Compound” Combinatorial Library Method” Chem. Rev 1997, 97, 411–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Miller SJ “In Search of Peptide-Based Catalysts for Asymmetric Organic Synthesis” Acc. Chem. Res 2004, 37, 601–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Revell JD; Wennemers H “Peptidic Catalysts Developed by Combinatorial Screening Methods” Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2007, 11, 269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Haque TS; Little JC; Gellman SH “Stereochemical Requirements for b-Hairpin Formation: Model Studies with Four-Residue Peptides and Depsipeptides” J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 6975–6985. [Google Scholar]

- (18).A comparison of CDCl3 and CHCl3 (with and without Al2O3 treatment) revealed essentially no differences. See Table S1 in the Supporting Information for details.

- (19).Hurtley AE; Stone EA; Metrano AJ; Miller SJ “Desymmetrization of Diarylmethylamido Bis(phenols) through Peptide-Catalyzed Bromination: Enantiodivergence as a Consequence of a 2 amu Alteration at an Achiral Residue within the Catalyst” J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 11326–11336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Londregan AT; Jennings S; Wei L “General and Mild Preparation of 2-Aminopyridines” Org. Lett 2010, 12, 5254–5257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Londregan AT; Jennings S; Wei L “Mild Addition of Nucleophiles to Pyridine-N-Oxides” Org. Lett 2011, 13, 1840–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Clissold SP; Sorkin EM; Goa KL “Loratadine - A Prelim- inary Review of its Pharmacodynamic Properties and Therapeutic Efficacy” Drugs 1989, s, 42–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Piwinski JJ; Wong JK; Chan TM; Green MJ; Ganguly AK “Hydroxylated Metabolites of Loratadine: An Example of Conformational Diastereomers Due to Atropisomerism” J. Org. Chem 1990, 55, 3341–3350. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Morgan B; Zaks A; Dodds DR; Liu J; Jain R; Megati S; Njoroge FG; Girijavallabhan VM “Enzymatic Kinetic Resolution of Piperidine Atropisomers: Synthesis of a Key Intermediate of the Farnesyl Protein Transferase Inhibitor, SCH66336.” J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 5451–5459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).(a) Rouden J; Lasne M-C; Blanchet J; Baudoux J “(–)-Cytisine and Derivatives: Synthesis, Reactivity, and Applications” Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 712–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Coe JW; Brooks PR; Vetelino MG; Wirtz MC; Arnold EP; Huang J; Sands SB; Davis TI; Lebel LA; Fox CB; Shrikhande A; Heym JH; Schaeffer E; Rollema H; Lu Y; Mansbach RS; Chambers LK; Rovetti CC; Schulz DW; Tingley FD; O’Neill BT “Varenicline: An α4β2 Nicotinic Receptor Partial Agonist for Smoking Cessation” J. Med. Chem 2005, 48, 3474–3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.