Abstract

One of the main characteristics of atherosclerosis is vascular calcification, which is linked to adverse cardiovascular events. Increased homocysteine (Hcy), a feature of hyperhomocysteinemia, is correlated with advanced vascular calcification and phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). Oxidative stress and high phosphate levels also induce VSMC calcification, suggesting that the Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) signaling pathway may also contribute to vascular calcification. In this study, we investigated this possibility and the role and mechanisms of Hcy in vascular calcification. We found that in atherosclerotic apolipoprotein E–deficient (ApoE−/−) mice, Hcy significantly increases vascular calcification in vivo, as well as VSMC calcification in vitro. Of note, the Hcy-induced VSMC calcification was correlated with elevated KLF4 levels. Hcy promoted KLF4 expression in calcified atherosclerotic lesions in vivo and in calcified VSMCs in vitro. shRNA-mediated KLF4 knockdown blocked the Hcy-induced up-regulation of runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and VSMC calcification. RUNX2 inhibition abolished Hcy-induced VSMC calcification. Using ChIP analysis, we demonstrate that KLF4 interacts with RUNX2, an interaction promoted by Hcy stimulation. Our experiments also revealed that the KLF4 knockdown attenuates Hcy-induced RUNX2 transactivity, indicating that KLF4 is important in modulating RUNX2 transactivity. These findings support a role for Hcy in regulating vascular calcification through a KLF4–RUNX2 interaction and indicate that Hcy-induced, enhanced RUNX2 transactivity increases VSMC calcification. These insights reveal possible opportunities for developing interventions that prevent or manage vascular calcification.

Keywords: homocysteine, calcification, vascular smooth muscle cells, Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4), cell biology, gene regulation, atherosclerosis, hyperhomocysteinemia, RUNX2

Introduction

Atherosclerosis increases the occurrence of peripheral vascular disease, cerebral infarction, and coronary heart disease. Among its characteristics, arterial calcification is the most common feature (1–7). Abnormal deposition of hydroxyapatite mineral in the arteries leads to arterial wall thickening and hardening, vascular lumen narrowing, and ischemia or necrosis of tissues or organs (1, 8). Intimal calcification and medial calcification are two types of vascular calcification; they share many common mechanisms, but they have their unique set of risk factors, cellular processes, and clinical presentations. The mechanisms of vascular calcification in atherosclerosis are complex and not yet fully clear (5). Cardiovascular calcification is now recognized as an active process, which provides a potential opportunity for effective therapeutic targeting (6). Many reports indicated that osteogenic differentiation of VSMC in response to various local stimuli is a key mechanism in the development of vascular calcification (9, 10).

Hyperhomocysteinemia (Hhcy)2 is closely linked to atherosclerosis and is one of the risk factors of atherosclerosis (11, 12). We and others have reported that Hhcy promotes atherosclerosis via promoting macrophage apoptosis (13, 14), inhibiting endothelial cell growth (15), and promoting inflammatory monocyte differentiation (16). Studies have shown that Hcy significantly increases oxidative stress via up-regulation of NOX4 and NOX2 in endothelial cells (17), and Hcy significantly up-regulates the expression of NOX4 in adventitial fibroblasts in vitro (18). Earlier studies found that Hcy was linked to increased calcification of blood vessels, possibly by strengthening of lipid peroxidation (19, 20). Hcy also induced calcium deposition and alkaline phosphatase activity in mesenchymal stem cells (21). However, the mechanism underlying Hcy-promoted phenotypic switch of VSMC in atherosclerotic vascular calcification remains unknown.

Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) is a zinc finger transcription factor family member required in mammalian embryonic development and various diseases. KLF4 promotes phenotypic switching of VSMC (4, 22, 23). Furthermore, activation of KLF4 in VSMC by phosphate (24) and or oxidized phospholipids (25) promotes phenotypic switch of VSMC. In addition, KLF4 also mediates H2O2-induced injury in human cardiomyocyte (26) and oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in follicular granulosa cell (27). Because oxidative stress and high phosphate also induce VSMC calcification (28–30), we hypothesized that activating KLF4 signaling pathway may contribute to vascular calcification.

The present study investigated the function of Hcy in the regulation of vascular calcification in vitro and in vivo. In addition, we determined the role of KLF4 in mediating Hcy-induced VSMC calcification and explored the interplay between KLF4 and RUNX2 in calcification development. We found that Hcy enhanced atherosclerotic vascular calcification in vivo and promoted calcification of VSMC in vitro. Furthermore, activation of KLF4 up-regulated RUNX2 and its transactivity, leading to VSMC calcification. Our findings add to the current understanding of vascular calcification mechanisms and present new fields of research and new strategies for prevention and treatment vascular calcification.

Results

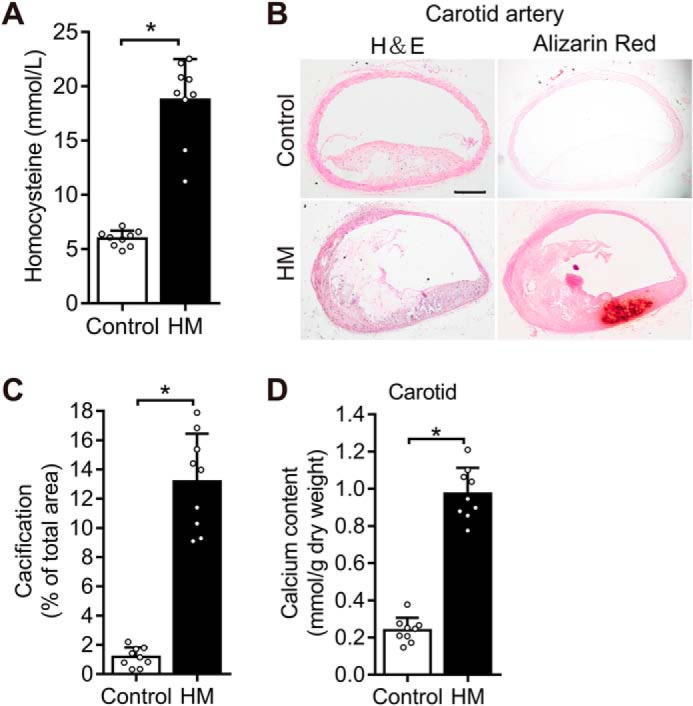

Vascular calcification in ApoE−/− mice stimulated by methionine diet in vivo

To examine the effects of Hhcy on vascular calcification in vivo, homocysteinemia was administrated to mice. Compared with ApoE−/− mice fed control diet, methionine diet-fed mice showed a significant increase in Hcy after 30 weeks (Fig. 1A). The plasma Hcy level was 5.964 ± 0.24 mmol/liter in control ApoE−/− mice and increased to 18.76 ± 1.25 mmol/liter in the methionine-fed ApoE−/− mice. These results demonstrate the effects of methionine-triggered Hhcy on vascular calcification in the atherosclerotic mice. It was observed that Hhcy increased vascular calcification in mice carotid arteries in vivo (Fig. 1, B and C). Carotid arteries with alizarin red staining displayed increased calcification in methionine-treated ApoE−/− mice (Fig. 1, B and C). Moreover, high calcium level in the carotid arteries revealed that Hhcy remarkably promoted calcification (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that Hhcy increases vascular calcification in atherosclerosis in vivo.

Figure 1.

Methionine diet increases Hhcy, thereby accelerating vascular calcification in ApoE−/− mice. Hhcy increases vascular calcification in atherosclerosis mice. ApoE−/− mice were fed on control diet and methionine diet for 30 weeks (n = 9 mice/group). The results are expressed as the ratio of positive staining area to the total area, and bar values stands for means ± S.D. *, p < 0.01. A, quantification of plasma homocysteine level. B, determination of vascular calcification in the carotid artery. Paraffinized carotid artery sections stained with alizarin red. The scale of the image is shown in the lower right corner. Scale bar, 500 μm. C, total area of calcification quantified in the carotid artery using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). D, determination of vascular calcification in the carotid artery based on the calcium content with the Arsenazo III method.

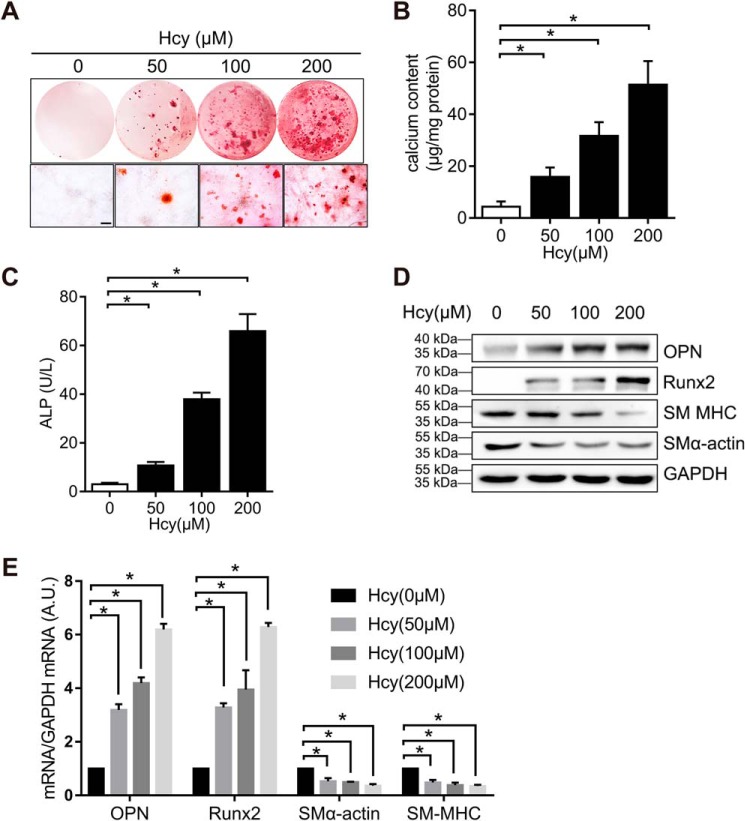

Hcy induces VSMC calcification

To define whether Hcy increases vascular calcification in vitro, we treated A7r5 VSMC with different concentrations of Hcy in the osteogenic medium. Alizarin red staining showed that Hcy increased VSMC calcification in vitro (Fig. 2A). The increases in calcium content and alkaline phosphate activity in a dose-dependent manner further confirmed the effect of Hcy on VSMC calcification in vitro (Fig. 2, B and C). The results confirmed that Hcy suppressed the level of smooth muscle marker genes α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SM MHC) but elevated the level of bone-associated markers, RUNX2 and osteopontin (OPN) (Fig. 2, D and E), suggesting that Hcy promotes osteogenic differentiation of VSMC.

Figure 2.

Hcy induces VSMC calcification. VSMC lines grown in osteogenic growth medium with or without Hcy for 3 weeks. VSMC were serum-starved for 24 h and then treated with different concentrations of Hcy. A, level of VSMC calcification in vitro by alizarin red staining. The lower image shows the high magnification. Scale bar, 1 mm. B, quantification of calcium content by Arsenazo III method. The data are normalized to the total protein (n = 3) *, p < 0.01. C, ALP activity quantified by a colorimetric analysis (n = 3). *, p < 0.01). D, Western blotting results of α-SMA, SM MHC, RUNX2, and OPN in VSMC. GAPDH served as the loading control. E, qPCR analysis of α-SMA, SM MHC, RUNX2, and OPN in VSMC. VSMC genes expression at control conditions (first bar in each group) is defined as 1 (n = 3). *, p < 0.01 relative to control conditions.

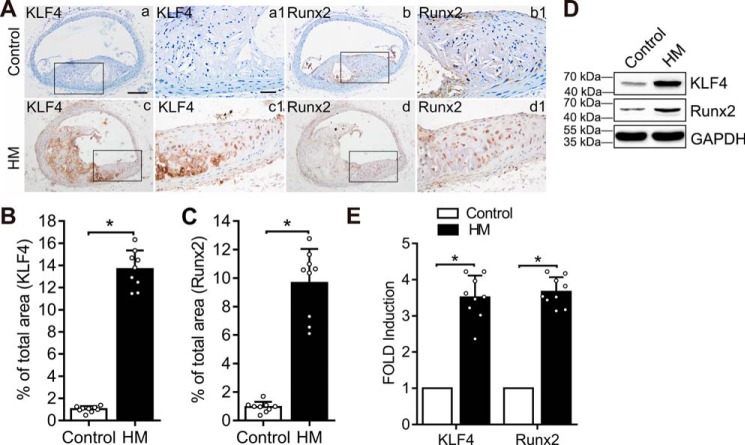

Hcy induces expression of KLF4

To understand the mechanisms of Hcy-induced VSMC calcification, we determined the effects of Hcy on the expression of KLF4, a key regulator for the phenotypic switch of VSMC, and the expression of RUNX2, the master osteogenic regulator for VSMC calcification. We found increased KLF4 in the carotid artery sections from mice fed a methionine diet (Fig. 3, A and B). Similarly, increased RUNX2 was observed in the carotid artery sections from mice fed on methionine diet (Fig. 3, A and C). Western blotting and qPCR analyses demonstrated that methionine diet increased KLF4 expression and RUNX2 level in the carotid artery (Fig. 3, D and E). Therefore, increased expression of KLF4 and RUNX2 may contribute to Hcy-triggered vascular calcification.

Figure 3.

Methionine diet increased KLF4 expression. ApoE−/− mice were fed on control diet and methionine diet for 30 weeks (n = 9 mice/group). *, p < 0.01. A, immunohistochemistry analysis of KLF4 (panels a and c) and RUNX2 (panels b and d) in carotid artery paraffinized sections. Higher-magnification images are shown to the right of each image (panels a1, b1, c1, and d1). The scale of the image is provided on the lower right corner (panels a and a1): scale bar in panel a, 500 μm; and scale bar in panel a1, 100 μm. B and C, measurement of KLF4 and RUNX2 expression in carotid artery paraffinized sections. The results are expressed as the ratio of positive staining area to total area by ImageJ software, and bar values stands for means ± S.D. *, p < 0.01. D, Western blotting analysis of KLF4 and RUNX2 in carotid artery tissues in the two groups. GAPDH was used as the loading control. E, qPCR analysis of RUNX2 and KLF4 expression in carotid artery tissues in two groups. The expression of RUNX2 and KLF4 in the first bar in each group is defined as 1 (n = 3). *, p < 0.01 relative to control conditions. Con, control.

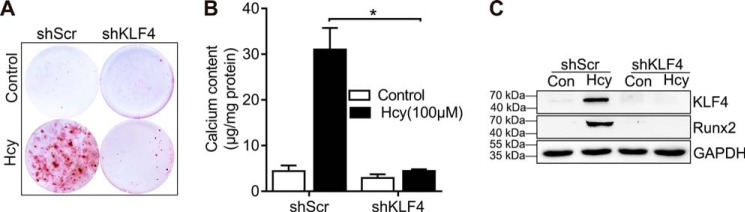

Knockdown of KLF4 expression attenuates Hcy-induced VSMC calcification

Having shown that Hhcy increased expression of KLF4 in vivo, we determined whether KLF4 inhibition can reverse the calcification caused by Hcy in vitro. We designed in vitro studies in which KLF4 expression was knocked down by specific shRNA. Hcy-induced calcification was blocked in the KLF4 knockdown cells (Fig. 4, A and B). Knockdown of KLF4 blocked RUNX2 expression (Fig. 4C), supporting the role of KLF4 in mediating Hcy-induced RUNX2 up-regulation and VSMC calcification. The results presented here demonstrate that Hcy activates KLF4, thereby up-regulating RUNX2 and VSMC calcification.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of KLF4 attenuates Hcy-induced VSMC calcification. VSMC were infected with lentivirus particles contain control (shScr) or KLF4 specific shRNA (shKLF4) and then exposed to Hcy in osteogenic medium for 3 weeks. A, VSMC calcification measurement using alizarin red staining. B, measurement of calcium content (n = 3). *, p < 0.01. C, RUNX2 and KLF4 protein expression. Con, control.

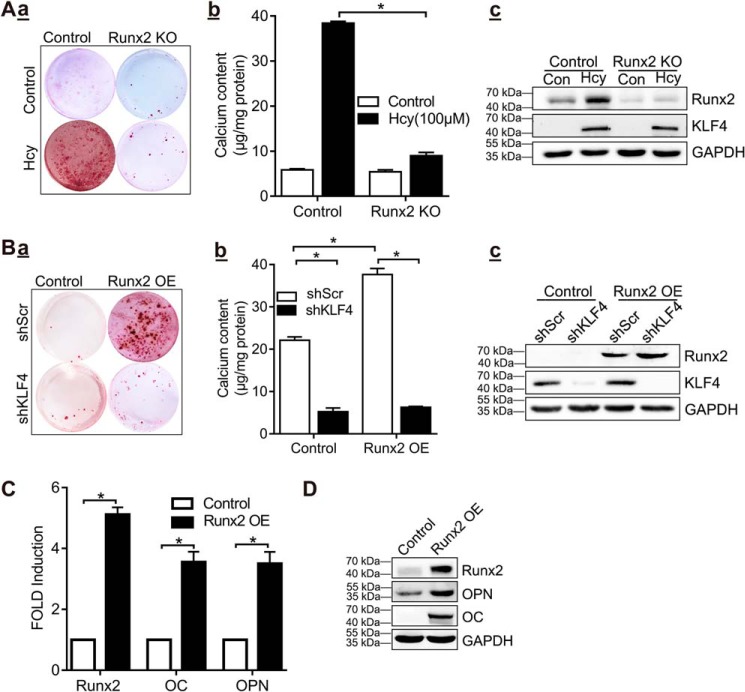

Hcy-induced KLF4 expression promotes VSMC calcification via RUNX2

To examine whether Hcy-induced increase in RUNX2 is critical for calcification of VSMC, we used shRNA to knock down the expression of RUNX2 in VSMC. The results showed that VSMC calcification was abolished in VSMC with RUNX2 knockdown, compared with the control group (Fig. 5A, panel a). The difference in calcium content between the groups indicated that RUNX2 knockdown inhibited Hcy-induced VSMC calcification (Fig. 5A, panel b). Notably, Hcy-induced KLF4 expression occurred similarly in RUNX2 knockdown VSMC and in control cells (Fig. 5A, panel c), suggesting that RUNX2 is a downstream effector of Hcy-induced KLF4 expression. In addition, alizarin red staining (shScr; Fig. 5B, panel a) and quantitative calcium measurement (shScr; Fig. 5B, panel b) showed that overexpression of RUNX2 induced VSMC calcification in control VSMC. The amount of KLF4 was not affected by RUNX2 overexpression (shScr; Fig. 5B, panel c). In contrast, RUNX2-induced VSMC calcification was eliminated following KLF4 knockdown (shKLF4; Fig. 5B, panels a and b), but this knockdown did not alter RUNX2 expression (Fig. 5B, panel c). Furthermore, overexpression of RUNX2 increased the expression of osteogenic marker genes OPN and osteocalcin (OC) (Fig. 5, C and D). These data sets demonstrated that inhibition of KLF4 or RUNX2 blocks Hcy-induced VSMC calcification, indicating an interaction between RUNX2 and KLF4 in Hcy-induced VSMC calcification.

Figure 5.

Hcy-induced KLF4 activation enhances VSMC calcification through RUNX2. A, RUNX2 knockout blocked Hcy-induced VSMC calcification. VSMCs from infected with lentivirus particles containing control (control) or RUNX2-specific shRNA (RUNX2 KO) were cultured in osteogenic medium for 21 days. Panel a, alizarin red staining for calcification. Panel b, calcium content in different experimental groups (n = 3). *, p < 0.01. Panel c, Western blotting results of RUNX2 and KLF4. B, knockdown of KLF4 inhibited RUNX2-induced VSMC calcification. Stably selected VSMCs with control (shScr) or KLF4 shRNA (shKLF4) were infected with the control lentivirus (Control) or RUNX2 protein (RUNX2 OE) and cultured for 21 days in osteogenic medium. Panel a, alizarin red staining for calcification. Panel b, calcium content in different experimental groups. (n = 3). *, p < 0.01. Panel c, Western blotting analysis of RUNX2 and KLF4 expression. C, qPCR analysis of RUNX2, OC and OPN in VSMC with RUNX2 overexpression. The expression of each gene in VSMC (the first column in each group) was defined as 1 under control conditions (n = 3). *, p < 0.01 compared with control conditions). D, Western blotting analysis of RUNX2, OC, and OPN expression in VSMC with RUNX2 overexpression.

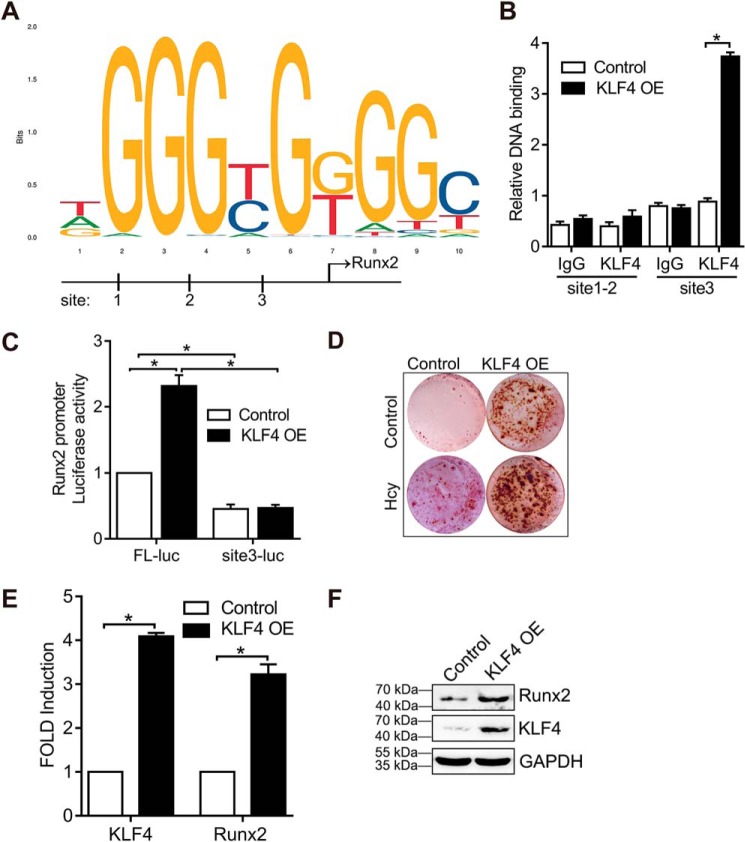

KLF4 regulates RUNX2 transcription

We found that KLF4 knockdown inhibited RUNX2 expression (Fig. 4C), indicating that RUNX2 is modulated by KLF4 transcription factor. Using the JASPAR data set, we identified three putative KLF4-binding sites in the 5′-flanking region of the RUNX2 gene: +1897/1888, +1640/1649, and −555/546, based on the KLF4 sequence outlined in Fig. 6A (+ refers that the binding site is on the sense strand, and − refers the binding site on the antisense strand). The sequence is shown in Fig. 6A. To assess whether KLF4 interacts with RUNX2 gene, an anti-KLF4 antibody was used for ChIP assay. The RUNX2 promoter segment containing the putative KLF4-binding site was amplified by PCR using the selected primer site 1–2 (+1897/1649) and site 3 (−555/546). Fig. 6B revealed that KLF4 overexpression in VSMC increased KLF4 binding to the RUNX2 promoter at the upstream site 3 of the TSS, whereas in the other putative site, no significant KLF4 binding was observed between +1897 and 1649. We then generated a plasmid construct (pGL3-RUNX2-Luc) containing the upstream region of the RUNX2 promoter fused to the luciferase reporter gene. KLF4 overexpression elevated the luciferase activity in VSMC transfected with RUNX2 FL-Luc (Fig. 6C). However, deletion of the region between −555 to −546 bp containing the predicted KLF4-binding site 3 did not increase luciferase activity (Fig. 6C), indicating that this region is required for KLF4 binding and RUNX2 transcription. Alizarin red staining demonstrated that overexpression of KLF4 triggered VSMC calcification in control VSMC (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, overexpression of KLF4 was sufficient to promote RUNX2 expression in VSMC (Fig. 6, E and F). Thus, increased expression of KLF4, induced by Hcy or mediated by a viral infection, up-regulates the expression of RUNX2 in calcified VSMC.

Figure 6.

KLF4 regulates RUNX2 transcription. A, description of the predicted KLF4-binding site in rat RUNX2 gene from +1897 to +1888 bp (site 1), +1640 to +1649 bp (site 2), and −555 to −546 bp (site 3). B, VSMCs treated with or without KLF4 overexpression were analyzed by ChIP assay using anti-KLF4. KLF4-binding site from +1897 to +1649 bp (site 1–2) and −555 to −546 bp (site 3). KLF4 promoter enrichment analysis by qPCR. IgG was used as the control isotype. C, transfection of the luciferase reporter gene with the VSMC and RUNX2 promoter region (RUNX2 FL-Luc) or site 3 deletion (RUNX2 site3-Luc) and co-transfection with a control plasma expressing Renilla luciferase for 6 h, followed by infection with LV-KLF4 (KLF4 OE) or control lentivirus (LV-GFP) (control) for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to the activity of Renilla luciferase. D, VSMCs were transduced with LV-KLF4 (KLF4 OE) or control lentivirus (LV-GFP) (control) and cultured for 21 days in osteogenic medium. Alizarin red staining for calcification. E, qPCR analysis of KLF4 and RUNX2 in VSMCs with KLF4 overexpression. The expression of each gene in VSMC (the first column in each group) was defined as 1 under control conditions (n = 3). *, p < 0.01 relative to control conditions. F, Western blotting analysis of KLF4 and RUNX2 expression in VSMCs with KLF4 overexpression.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that Hcy induced VSMC calcification in atherosclerosis mice in vivo and in VSMC in vitro. It was also found that activation of KLF4 by Hcy in the vasculature is key to atherosclerosis vascular calcification. We provide evidence that binding of KLF4 to RUNX2 promoter contributes to high expression of RUNX2 and VSMC calcification. Because KLF4 is a master transcription factor, these new findings have exciting implications for treatment as well as prevention of atherosclerosis vascular calcification through therapies targeting KLF4 and signaling.

Emerging studies have linked atherosclerosis and vascular calcification with Hhcy (31, 32). Hcy was found to be independently associated with intracranial arterial calcification (31). A previous report showed that Hhcy induced by supplementation promotes atherosclerosis progression in ApoE−/− mice (33). However, whether methionine-induced Hhcy can cause atherosclerosis vascular calcification in vivo is not clear. In vivo, we identified that increased Hcy enhanced vascular calcification during atherosclerosis in mice (Fig. 1). Using cultured VSMCs, we found that high expression of Hcy induced VSMC calcification. Although it was previously known to be a passive process characterized by calcium deposition, vascular calcification is now recognized as a tightly modulated dynamic process driven by osteochondrogenic differentiation of vascular cells (3). Based on the analysis of gene expression of the osteogenic factors and markers, it was herein observed that Hcy promoted vascular calcification and osteogenic differentiation of VSMC in vitro. Moreover, these effects were dose-dependent (Fig. 2). These findings are in line with prior reports that osteogenic differentiation of VSMC plays a key role in vascular calcification associated with atherosclerosis.

Our studies determined a new role of Hcy in promoting VSMC calcification via KLF4 pathway. KLF4 is a master transcription factor associated with many biological processes (34). Emerging studies demonstrate that KLF4 participates in many contexts during phenotypic switching of SMCs (22, 25, 35, 36). For instance, KLF4 inhibits the level of SMC differentiation-associated genes, e.g. SM22, SM-myosin heavy chain, and α-SMA following exposure to oxidized phospholipids or platelet-derived growth factor BB (37, 38)

We found that increased expression of KLF4 was associated with vascular calcification in the Hcy-induced atherosclerosis arteries (Fig. 3). Furthermore, inhibition of KLF4 expression attenuated VSMC calcification in vitro, confirming the essential role of KLF4 activation in mediating Hcy-induced vascular calcification (Fig. 4). Notably, constitutively active KLF4 was able to induce calcification of VSMC (Fig. 6), implying that KLF4 activation has profound effects on vascular calcification.

This study has revealed an important regulatory mechanism of RUNX2 transcription by KLF4, which underlies the Hcy-induced osteogenic differentiation and calcification of VSMC. Stimulation of KLF4 has been shown to promote bone formation and cell differentiation by interacting with RUNX2, thereby slightly inhibiting RUNX2 expression (35). In contrast, we found that high expression of KLF4 induced by Hcy increased RUNX2 expression in VSMC (Fig. 6), thus promoting VSMC calcification. Therefore, KLF4 may be differentially regulated and have different functions depending on the cell types, cellular environment and disease status. Our results reveal an important role of KLF4 activation in promoting osteogenic differentiation of VSMC, which contributes to increased vascular calcification in atherosclerosis. Furthermore, this study identified the link between RUNX2 and KLF4 in VSMC, which played important roles in Hcy-induced VSMC calcification. Hence, Hcy potentiates the binding of KLF4 to RUNX2 promoter, thereby up-regulating RUNX2 transcription and promoting VSMC calcification.

Conclusion

Our study has revealed an important role of Hcy in promoting VSMC osteogenic differentiation and vascular calcification in atherosclerosis. Results further show that Hcy up-regulates KLF4 signal, and KLF4 in turn regulates RUNX2 transcription, leading to VSMC calcification. Further studies using SMC-specific KLF4 knockout mice are warranted to determine the role of KLF4 in regulating Hhcy-induced atherosclerotic vascular calcification in vivo. Nonetheless, a key molecular mechanism in which Hcy-promoted up-regulating RUNX2 and VSMC calcification via KLF4 has been presented. This offers new targets for vascular calcification management.

Experimental procedures

Experimental animals

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Animal Experiments of the Health Science Centre of Ningxia Medical University and were carried out in conformity with the recommended guidelines. Eight-week-old ApoE−/− mice of C57BL/6J genetic origin were purchased from the Animal Centre of Peking University Health Science Centre (Beijing, China). The use of ApoE−/− mice is a well-established atherosclerosis model (39). Nine mice were assigned to each group, including male and female, and were fed with following diets (KeAoXieLi, Beijing, China) for 30 weeks: the control group ate a standard rodent maintenance diet-93 purified diet (AIN-93G) as recommended by the American Institute of Nutrition and the hypermethionine group ate a chow diet plus a methionine-containing diet (17 g/kg) (13, 14). Random selection and blinding methods were used for the selection of experimental animal.

Tissue processing

After feeding for 30 weeks, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (catalog no. 55) inhaled at a concentration of 2%, which was maintained at the concentration of 1.5%, after which 2 ml of peripheral blood was obtained from the iliac vein. The blood was immediately collected into microtubes containing cooled EDTA, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm and 4 °C for 15 min, and then kept at −80 °C for experimentation. Serum Hcy was measured as previously described (14). Carotid artery tissue from mice was washed with sterile PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (15 min), and then embedded in paraffin. Sections cut into 4-mm thickness were subjected to alizarin red staining, hematoxylin/eosin, and immunohistological analysis. Carotid tissue was also used for Western blotting and quantitative PCR detection tests.

Artery calcification

Calcium deposits in the carotid artery was detected by alizarin red (Sigma–Aldrich) staining (40, 41). Paraffin sections were gradually deparaffinized in Histo-Clear and incubated in alizarin red solution for 5 min after washing with distilled water. The sections were dehydrated and coverslipped, examined by microscopy, and then photographed. The percentage of positive-stained surface area in each section was determined using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Calcium content in carotid arteries was quantified as reported in a prior study (40, 41). Carotid artery specimen was lyophilized to obtain dry weight and incubated with 0.6 mmol/liter HCl at 37 °C for 48 h. Calcium was examined by Arsenazo III method with calcium diagnostic kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). The content of carotid artery calcium is represented as millimolar/gram standardized to the dry weight of the tissues.

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical staining was performed to determine protein expression in paraffinized sections. Carotid paraffin section was deparaffinized in Histo-Clear reagent, washed with distilled water, and treated with avidin/biotin blocking kit to inhibit endogenous biotin activity according to the manufacturer's protocol. The sections were incubated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide to quench endogenous peroxidase activity followed by blocking with 10% goat serum 1 h at room temperature. Next, specimens were incubated with primary antibody KLF4 (Abcam, ab215036) or RUNX2 (Abcam, ab23981) at 4 °C overnight. The sections were incubated with diluted biotinylated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling, 7075) for 1 h at 37 °C and then treated with horseradish peroxidase–labeled streptavidin solution for 20 min at 37 °C. Lastly, the sections were stained with diaminobenzidine (DAB kit, ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China) and counterstained with hematoxylin.

VSMC culture and transfection

Rat aortic smooth muscle cells (A7r5) used for in vitro experiments were bought from the American Type Culture Collection. The cell cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere and grin-grown to reach the desired confluence. The growth medium contained Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (high glucose, Hyclone) together with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 100 unit/ml penicillin. The medium was changed once a day. To prepare a calcification model in vitro, 10 mmol/liter β-sodium glycerophosphate was added to the growth medium and cultured for 3 weeks (9, 41). To determine the role of Hcy in vitro, 50, 100, and 200 μmol/liter Hcy (Sigma–Aldrich) was added to the growth medium for 3 weeks (14). For shRNA knockdown, the specific shRNA against RUNX2 (5′-AAGCTTGATGACTCTAAACCTAG-3′), KLF4 (5′-GACCGAGGAGTTCAACGATCT-3′), and control (5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′) were designed by Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and packaged into viral vector, purified, and transfected with 293T cells with helper vectors. After 6 h of transfection, the cells were replaced with fresh medium and cultured for 72 h. The supernatant of the cells enriched in lentiviral particles was collected, and the virus was measured. The VSMCs were infected with the lentivirus particles at a multiplicity of infection of 50. After virus transduction for 48 h, the VSMCs were passaged at a ratio of 1:10 and cultured in a medium containing 2 μg/ml puromycin for 1 week. For RUNX2 and KLF4 overexpression, lentiviral vector containing their cDNAs was obtained from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. The recombinant lentivirus is packaged into 293T cells and collected, and then the VSMCs were infected with lentivirus particles.

In vitro calcification

For calcification staining in vitro, the cells were cultured in a medium containing 10 mmol/liter β-sodium glycerophosphate with or without Hcy for 3 weeks. After washing with PBS, cell samples were fixed with paraformaldehyde for 45 min at 4 °C, then treated with alizarin red staining (Sigma–Aldrich) for 5 min at room temperature, washed with double-distilled water, dehydrated, and coverslipped. The section were examined by microscopy and photographed. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) was used to calculate the percentage of positive-stained surface area in each section. Determination of calcium content in cells requires decalcification with 0.6 mmol/liter HCl at 37 °C for 48 h (40, 41). The calcium content was examined by Arsenazo III method with calcium diagnostic kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), following the manufacturer's protocols. For ALP activity, the cell lysates were treated with an alkaline phosphatase assay kit (Abcam, ab83369) following the manufacturer's guidelines, after which absorbance was read at OD 405 nm.

Western blotting analysis

Vascular tissue or cells were lysed with lysis buffer and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm, 4 °C for 30 min to extract total protein from the lysate (KeyGEN BioTECH, JiangSu, China). Protein concentration was carried out using BCA protein assay kit (KeyGEN BioTECH). Approximately 40 μg of protein samples were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE gel, and electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. 5% skim milk was used to treat the membrane for 1 h at room temperature, and the blot was incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C: anti–α-SMA (Abcam, ab5694, 1:2000), anti–SM MHC (Abcam; ab53219, 1:1000), anti-RUNX2 (Abcam, ab23981, 1:1000), anti-KLF4 (Abcam, ab215036, 1:1000), anti-OPN (Abcam, ab214050, 1:1000), anti-OC (Abcam, ab93876, 1:1000), and anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling, 97166, 1:2000) antibodies for normalization. The blot membrane was washed with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibody for 1 h at room temperature, then detected by ECL test.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was obtained from vascular tissues or cells using a Total RNA kit (Omega Bio-tek) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA was used to synthesize cDNA by PrimeScript Master Mix kit (Takara, Tokyo). The mRNA level of α-SMA, SM MHC, RUNX2, KLF4, OPN, OC, and GAPDH were detected by real-time quantitative PCR using the SYBR Select Master Mix (Invitrogen) on a iQ5 Multicolour real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). GADPH mRNA levels were used for normalization. The formula 2 − ΔΔCT was used to calculate mRNA relative expression. Primers used for RT-qPCR in Table 1 were obtained from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

Table 1.

Lists of primers used for RT-qPCR

| Name | Species | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| RUNX2 | Rattus norvegicus | Forward: CCACCACTCACTACCACACG |

| Reverse: GGACGCTGACGAAGTACCAT | ||

| RUNX2 | Mus musculus | Forward: TAGCGGCAGAATGGATGAGTC |

| Reverse: AAACCCAGTTATGACTGCCCC | ||

| KLF4 | Rattus norvegicus | Forward: GAGACCGAGGAGTTCAACGA |

| Reverse: GGAAGACGAGGATGAAGCTG | ||

| KLF4 | Mus musculus | Forward: TGGCCATCGGACCTACTTATC |

| Reverse: CATGTCAGACTCGCCAGGTG | ||

| GAPDH | Rattus norvegicus | Forward: AGACTGGCAGTGGTTTGCTT |

| Reverse: CTCTCTGCATGGTCTCCGTC | ||

| GAPDH | Mus musculus | Forward: CAGGTTGTCTCCTGCGACTT |

| Reverse: TATGGGGGTCTGGGATGGAA | ||

| SMα-actin | Rattus norvegicus | Forward: CCACCAACCCCCAAAGAGAA |

| Reverse: GGGCAAAGAACGAGGGATCA | ||

| SM MHC | Rattus norvegicus | Forward: CCAAGTTCTCCAAGGTGGAA |

| Reverse: CACAGAAGAGGCCCGAGTAG | ||

| OPN | Rattus norvegicus | Forward: AGACTGGCAGTGGTTTGCTT |

| Reverse: CTCTCTGCATGGTCTCCGTC | ||

| OC | Rattus norvegicus | Forward: ATTGTGACGAGCTAGCGGAC |

| Reverse: TCGAGTCCTGGAGAGTAGCC |

Promoter construction and luciferase reporter assays

To detect the transactivity of RUNX2 following KLF4 stimulation, bioinformatics methods were used to analyze and predict possible KLF4-binding sites in the promoter region of RUNX2. The RUNX2 promoter fragment was cloned from the genomic DNA by PCR using the designed primers, the fragment was inserted into the luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL3-basic), and then the pGL3-Runx-Luc (RUNX2 FL-Luc) was constructed. The mutant RUNX2 luciferase reporter plasmid (RUNX2 site3-Luc) was generated by deleting the putative KLF4-binding site (TGGGTGGGGA) at position −546/-555, and then the fragment was inserted into the luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL3-basic). A control plasmid encoding the Renilla luciferase was co-transfected into the cells with RUNX2 luciferase reporter plasmid for normalizing the transfection efficiency. After transfection with luciferase reporter plasmid for 6 h, the medium of the cells was changed, after which the cells were transfected with KLF4 overexpression plasmid for 24 h. The luciferase activity was determined by Dual-Luciferase assay kit (Promega) (9). Primers used for generating the luciferase reporter listed in Table 2 and lentiviruses were obtained from Hanbio Biotech. Co., Ltd. (Shanghai).

Table 2.

Lists of primers used for construction of luciferase reporter

| Name | Species | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| RUNX2 FL-Luc | Rattus norvegicus | Forward: CTCGAGACATCTTCATCTGCCAAGT |

| Reverse: AAGCTTCCTCCCTCTTTCTCTTCTGG | ||

| RUNX2 site3-Luc | Rattus norvegicus | Forward: cGtGAGGAAGGGAGAGAGAGAG |

| Reverse: CaCaCgTTCTCCCTCTCTG |

ChIP assays

ChIP assays were conducted according to the established protocol using anti-KLF4 (Abcam, ab106629) and anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz). Briefly, VSMCs were cross-linked with 0.75% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and quenched with 125 mm glycine. The cells were lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay (Santa Cruz) buffer and sonicated to fragment the DNA to a size of 200–1000 bp. The cell lysates were incubated with Dynabeads (Santa Cruz), vortexed at 4 °C for 1 h, and then precipitated by centrifugation. The supernatant was collected, and 10 μl (1%) was taken as input. Anti-KLF4 (Abcam, ab106629) and anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz) antibodies were added to the supernatant, co-cultured with Dynabeads overnight at 4 °C, and precipitated by centrifugation. Immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were reverse cross-linked, and DNA binding was quantified as the percentage of input using qPCR. Primers used for ChIP assays were obtained from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., in Table 3.

Table 3.

Lists of primers used for ChIP assays

| Name | Species | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| KLF4-Site 1–2 | Rattus norvegicus | Forward: CTGTCTGGCGACCCTATTGA |

| Reverse: GTTGCCAGATCACAACTGGG | ||

| KLF4-Site 3 | Rattus norvegicus | Forward: GGCAAGGAGTTTGCAAGCAGACC |

| Reverse: GCAGTGGGTCACATCTTGGGAT |

Statistical analysis

All experimental results were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 7.0 and presented as means ± S.D. or median. In vitro data are from at least three independent experiments. All data were tested for normality and equal variance. Student's t test was used for comparing differences between two groups, and one-way or two-way analysis of variance was used for multiple comparisons followed by a Student–Newman–Keuls test. A Mann–Whitney test was used for data not normally distributed. p < 0.05 was set as the threshold for significant.

Author contributions

L. Z. and S. J. conceptualization; L. Z. and N. Y. resources; L. Z., N. Z., G. C., N. Y., and W. M. data curation; L. Z., R. Y., W. Y., N. Y., and J. H. software; L. Z., N. Z., W. Y., G. C., N. Y., and W. M. formal analysis; L. Z., N. Z., R. Y., W. Y., G. C., W. M., J. H., and L. Y. methodology; L. Z. writing-original draft; L. Z., R. Y., and S. J. project administration; L. Z. writing-review and editing; R. Y. and S. J. investigation; J. H. and L. Y. validation; S. J. supervision; S. J. funding acquisition.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 81660060 and 81460079 and Ningxia Medical University Scientific Research Project of Advantage Discipline Construction Grant XY201704. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- Hhcy

- hyperhomocysteinemia

- Hcy

- homocysteine

- VSMC

- vascular smooth muscle cells

- KLF4

- Krüppel-like factor 4

- RUNX2

- runt-related transcription factor 2

- OPN

- osteopontin

- OC

- osteocalcin

- α-SMA

- α-smooth muscle actin

- SM MHC

- smooth muscle myosin heavy chain

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- OE

- overexpression

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR.

References

- 1. Demer L. L., and Tintut Y. (2008) Vascular calcification: pathobiology of a multifaceted disease. Circulation 117, 2938–2948 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lanzer P., Boehm M., Sorribas V., Thiriet M., Janzen J., Zeller T., St Hilaire C., and Shanahan C. (2014) Medial vascular calcification revisited: review and perspectives. Eur. Heart J. 35, 1515–1525 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sage A. P., Tintut Y., and Demer L. L. (2010) Regulatory mechanisms in vascular calcification. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7, 528–536 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bennett M. R., Sinha S., and Owens G. K. (2016) Vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 118, 692–702 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Voelkl J., Lang F., Eckardt K. U., Amann K., Kuro-O M., Pasch A., Pieske B., and Alesutan I. (2019) Signaling pathways involved in vascular smooth muscle cell calcification during hyperphosphatemia. Cell Mol Life Sci. 76, 2077–2091 10.1007/s00018-019-03054-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rogers M. A., and Aikawa E. (2019) Cardiovascular calcification: artificial intelligence and big data accelerate mechanistic discovery. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16, 261–274 10.1038/s41569-018-0123-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shaw L. J., Giambrone A. E., Blaha M. J., Knapper J. T., Berman D. S., Bellam N., Quyyumi A., Budoff M. J., Callister T. Q., and Min J. K. (2015) Long-term prognosis after coronary artery calcification testing in asymptomatic patients: a cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 163, 14–21 10.7326/M14-0612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shroff R., Long D. A., and Shanahan C. (2013) Mechanistic insights into vascular calcification in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24, 179–189 10.1681/ASN.2011121191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Byon C. H., Sun Y., Chen J., Yuan K., Mao X., Heath J. M., Anderson P. G., Tintut Y., Demer L. L., Wang D., and Chen Y. (2011) RUNX2-upregulated receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand in calcifying smooth muscle cells promotes migration and osteoclastic differentiation of macrophages. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31, 1387–1396 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.222547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sun Y., Byon C. H., Yuan K., Chen J., Mao X., Heath J. M., Javed A., Zhang K., Anderson P. G., and Chen Y. (2012) Smooth muscle cell-specific RUNX2 deficiency inhibits vascular calcification. Circ. Res. 111, 543–552 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.267237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCully K. S. (2015) Homocysteine metabolism, atherosclerosis, and diseases of aging. Compr. Physiol. 6, 471–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCully K. S. (2015) Homocysteine and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 8, 211–219 10.1586/17512433.2015.1010516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cong G., Yan R., Huang H., Wang K., Yan N., Jin P., Zhang N., Hou J., Chen D., and Jia S. (2017) Involvement of histone methylation in macrophage apoptosis and unstable plaque formation in methionine-induced hyperhomocysteinemic ApoE−/− mice. Life Sci. 173, 135–144 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jin P., Bian Y., Wang K., Cong G., Yan R., Sha Y., Ma X., Zhou J., Yuan Z., and Jia S. (2018) Homocysteine accelerates atherosclerosis via inhibiting LXRα-mediated ABCA1/ABCG1-dependent cholesterol efflux from macrophages. Life Sci. 214, 41–50 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.10.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jamaluddin M. D., Chen I., Yang F., Jiang X., Jan M., Liu X., Schafer A. I., Durante W., Yang X., and Wang H. (2007) Homocysteine inhibits endothelial cell growth via DNA hypomethylation of the cyclin A gene. Blood 110, 3648–3655 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang D., Fang P., Jiang X., Nelson J., Moore J. K., Kruger W. D., Berretta R. M., Houser S. R., Yang X., and Wang H. (2012) Severe hyperhomocysteinemia promotes bone marrow-derived and resident inflammatory monocyte differentiation and atherosclerosis in LDLr/CBS-deficient mice. Circ. Res. 111, 37–49 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lai W. K., and Kan M. Y. (2015) Homocysteine-induced endothelial dysfunction. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 67, 1–12 10.1159/000437098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu Z., Luo H., Zhang L., Huang Y., Liu B., Ma K., Feng J., Xie J., Zheng J., Hu J., Zhan S., Zhu Y., Xu Q., Kong W., and Wang X. (2012) Hyperhomocysteinemia exaggerates adventitial inflammation and angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm in mice. Circ. Res. 111, 1261–1273 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.270520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fang K., Chen Z., Liu M., Peng J., and Wu P. (2015) Apoptosis and calcification of vascular endothelial cell under hyperhomocysteinemia. Med. Oncol. 32, 403 10.1007/s12032-014-0403-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang Y., Yu F., Li J. X., Tang C. S., and Li C. Y. (2004) [Promoting effect of hyperhomocysteinemia on vascular calcification in rats]. Zhongguo Ying Yong Sheng Li Xue Za Zhi 20, 333–336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Campenhout A., Moran C. S., Parr A., Clancy P., Rush C., Jakubowski H., and Golledge J. (2009) Role of homocysteine in aortic calcification and osteogenic cell differentiation. Atherosclerosis 202, 557–566 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shankman L. S., Gomez D., Cherepanova O. A., Salmon M., Alencar G. F., Haskins R. M., Swiatlowska P., Newman A. A., Greene E. S., Straub A. C., Isakson B., Randolph G. J., and Owens G. K. (2015) KLF4-dependent phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells has a key role in atherosclerotic plaque pathogenesis. Nat. Med. 21, 628–637 10.1038/nm.3866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alexander M. R., and Owens G. K. (2012) Epigenetic control of smooth muscle cell differentiation and phenotypic switching in vascular development and disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 74, 13–40 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yoshida T., Yamashita M., and Hayashi M. (2012) Kruppel-like factor 4 contributes to high phosphate-induced phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells into osteogenic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 25706–25714 10.1074/jbc.M112.361360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yoshida T., Gan Q., and Owens G. K. (2008) Kruppel-like factor 4, Elk-1, and histone deacetylases cooperatively suppress smooth muscle cell differentiation markers in response to oxidized phospholipids. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 295, C1175–C1182 10.1152/ajpcell.00288.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang X., Liu F., Wang Q., and Geng Y. (2017) Overexpressed microRNA-506 and microRNA-124 alleviate H2O2-induced human cardiomyocyte dysfunction by targeting kruppel-like factor 4/5. Mol. Med. Rep. 16, 5363–5369 10.3892/mmr.2017.7243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xu L., Sun H., Zhang M., Jiang Y., Zhang C., Zhou J., Ding L., Hu Y., and Yan G. (2017) MicroRNA-145 protects follicular granulosa cells against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis by targeting Kruppel-like factor 4. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 452, 138–147 10.1016/j.mce.2017.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Al-Aly Z. (2011) Phosphate, oxidative stress, and nuclear factor-κB activation in vascular calcification. Kidney Int. 79, 1044–1047 10.1038/ki.2010.548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ciceri P., Elli F., Cappelletti L., Tosi D., Braidotti P., Bulfamante G., and Cozzolino M. (2015) A new in vitro model to delay high phosphate-induced vascular calcification progression. Mol. Cell Biochem. 410, 197–206 10.1007/s11010-015-2552-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brown R. B., Haq A., Stanford C. F., and Razzaque M. S. (2015) Vitamin D, phosphate, and vasculotoxicity. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 93, 1077–1082 10.1139/cjpp-2015-0083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim B. J., Kim B. S., and Kang J. H. (2015) Plasma homocysteine and coronary artery calcification in Korean men. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 22, 478–485 10.1177/2047487314522136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun Q., Jia X., Gao J., Mou W., Tong H., Wen X., and Tian Y. (2014) Association of serum homocysteine levels with the severity and calcification of coronary atherosclerotic plaques detected by coronary CT angiography. Int. Angiol. 33, 316–323 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lentz S. R. (2001) Does homocysteine promote atherosclerosis? Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 21, 1385–1386 10.1161/atvb.21.9.1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ghaleb A. M., and Yang V. W. (2017) Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4): what we currently know. Gene 611, 27–37 10.1016/j.gene.2017.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim J. H., Kim K., Youn B. U., Lee J., Kim I., Shin H. I., Akiyama H., Choi Y., and Kim N. (2014) Kruppel-like factor 4 attenuates osteoblast formation, function, and cross talk with osteoclasts. J. Cell Biol. 204, 1063–1074 10.1083/jcb.201308102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu Y., Sinha S., McDonald O. G., Shang Y., Hoofnagle M. H., and Owens G. K. (2005) Kruppel-like factor 4 abrogates myocardin-induced activation of smooth muscle gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9719–9727 10.1074/jbc.M412862200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yoshida T., Yamashita M., Horimai C., and Hayashi M. (2014) Deletion of Kruppel-like factor 4 in endothelial and hematopoietic cells enhances neointimal formation following vascular injury. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 3, e000622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cherepanova O. A., Pidkovka N. A., Sarmento O. F., Yoshida T., Gan Q., Adiguzel E., Bendeck M. P., Berliner J., Leitinger N., and Owens G. K. (2009) Oxidized phospholipids induce type VIII collagen expression and vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circ. Res. 104, 609–618 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meir K. S., and Leitersdorf E. (2004) Atherosclerosis in the apolipoprotein-E-deficient mouse: a decade of progress. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 1006–1014 10.1161/01.ATV.0000128849.12617.f4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang Y., Sun Y., Chen J., Bradley W. E., Dell'Italia L. J., Wu H., and Chen Y. (2018) AKT-independent activation of p38 MAP kinase promotes vascular calcification. Redox Biol. 16, 97–103 10.1016/j.redox.2018.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Deng L., Huang L., Sun Y., Heath J. M., Wu H., and Chen Y. (2015) Inhibition of FOXO1/3 promotes vascular calcification. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35, 175–183 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]