Abstract

Sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is a devastating complication of epilepsy which was under-recognized in the recent past despite its clear importance. In this review, we examine the definition of SUDEP, revise current pathophysiological theories, discuss risk factors and preventative measures, disclose tools for appraising the SUDEP risk, and last but not least dwell upon announcing and explaining the SUDEP risk to the patients and their caretakers. We aim to aid the clinicians in their responsibility of knowing SUDEP, explaining the SUDEP risk to their patients in a reasonable and sensible way and whenever possible, preventing SUDEP. Future studies are definitely needed to increase scientific knowledge and awareness related to this prioritized topic with malign consequences.

Keywords: Pathophysiology, prevention, risk factors, communication

WHAT IS SUDEP?

Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder bearing the rare possibility of devastating results. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is one of the most important but least known of these possible worrying results. The first formal definition of SUDEP has been made in 1997 by Nashef et al. as “sudden, unexpected, witnessed or unwitnessed, nontraumatic and non-drowning death in patients with epilepsy, with or without evidence for a seizure and excluding documented status epilepticus, in which postmortem examination does not reveal a toxicologic or anatomic cause of death” (1). Although the formal definition has undergone different revisions and modifications, the current criteria (Table 1) still carry the same essence with the original definition (2).

Table 1.

SUDEP criteria (2)

| 1. Definite SUDEPa: Sudden, unexpected, witnessed or unwitnessed, nontraumatic and non-drowning death, occurring in benign circumstances, in an individual with epilepsy, with or without evidence for a seizure and excluding documented status epilepticus (seizure duration ≥30 min or seizures without recovery in between), in which postmortem examination does not reveal a cause of death. 1a. Definite SUDEP Plusa: Satisfying the definition of Definite SUDEP, if a concomitant condition other than epilepsy is identified before or after death, if the death may have been due to the combined effect of both conditions, and if autopsy or direct observations/recordings of terminal event did not prove the concomitant condition to be the cause of death. |

| 2. Probable SUDEP/Probable SUDEP Plusa: Same as Definite SUDEP but without autopsy. The victim should have died unexpectedly while in a reasonable state of health, during normal activities, and in benign circumstances, without a known structural cause of death. |

| 3. Possible SUDEPa: A competing cause of death is present. |

| 4. Near-SUDEP/Near-SUDEP Plus: A patient with epilepsy survives resuscitation for more than one hour after a cardiorespiratory arrest that has no structural cause identified after investigation. |

| 5. Not SUDEP: A clear cause of death is known. |

| 6. Unclassified: Incomplete information available; not possible to classify. |

If a death is witnessed, an arbitrary cutoff of death within one hour from acute collapse is suggested.

SUDEP, sudden unexpected death in epilepsy.

SUDEP is the leading cause of epilepsy-related deaths (3). The incidence of sudden death among people with chronic epilepsy is 24- to 27-fold higher than control populations, with an annual incidence of 1 per 4500 pediatric and 1 per 1000 adult patients (4, 5). These rates are much higher among patients with drug-resistant seizures such as epilepsy surgery candidates. Moreover, SUDEP rates in patients with ongoing seizures following surgery had been reported as high as 2.46-9.3 per 1000 person years (6, 7). A lower, however, still prominent risk exists for newly diagnosed epilepsy patients with a rate of 1 in 10.000 patient years.

It is believed that SUDEP cases are highly unrecognized and underreported. The primary difficulty is that 90% of SUDEP cases are unwitnessed, therefore critical information regarding the events leading to death are not known in a majority of the cases, leaving the medical history and postmortem findings as the only source of information. Studies on death certificates and autopsy findings are not prosperous either. It is reported that, death certificates highly underestimate the SUDEP in epilepsy, attributing 1.5% of sudden deaths to seizure complications and seizures themselves (8, 9). When the patient undergoes autopsy, pathologists performing the autopsy tend to ignore SUDEP cases based on the rather vague pathological findings (10). Another pitfall would be the existence of comorbid conditions such as a minor coronary artery disease, etc. Death could be falsely attributed to these comorbid conditions instead of SUDEP. Therefore, better standardization of the pathological criteria, raised SUDEP awareness and better documentation are essential in this pursuit to understand and prevent SUDEP.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL THEORIES

Underlying mechanisms leading to SUDEP are highly debated and there is still not a single hypothesis explaining the SUDEP pathophysiology as a whole. It is mostly assumed that death happens following a seizure, mostly based on autopsy findings such as tongue and lip bites indicating a generalized tonic clonic seizure (GTCS) and witnessed SUDEP and near-SUDEP cases (11, 12). However, there are also case reports of witnessed SUDEP or near-SUDEP cases without any immediately prior visible seizures in the literature (13–15).

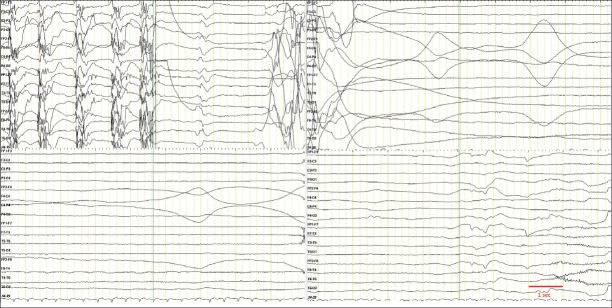

Still, why most of the seizures do not cause SUDEP and only a minority of seizures, lead up to this disastrous complication is not known. There are different mechanisms with rather strong evidence about their role in SUDEP pathophysiology: cardiac dysfunction, respiratory dysfunction, failing of the brainstem arousal systems and other factors such as neurotransmitter abnormalities and genetic mutations (Figure 1). MORTEMUS study, accomplished in video-EEG monitoring units is still one of the most important milestones in the pursuit of understanding the SUDEP process. What this study revealed is a peculiar pattern of cardiorespiratory dysfunction in SUDEP patients, either a centrally mediated alteration of severe cardiorespiratory function leading to death immediately after a GTCS, or a short period of partly restored function followed by a terminal apnea and later cardiac arrest (16).

Figure 1.

Pathophysiological mechanisms involved in SUDEP.

CARDIOVASCULAR DYSFUNCTION

Given that it has been one of the forerunning hypotheses since the definition of SUDEP, cardiovascular dysfunction during seizures and SUDEP is relatively well studied. Cardiac arrhythmia is a well-known companion of seizures; the most common arrhythmia is sinus tachycardia but other types of tachycardia, bradycardia (to the point of asystole), conduction blocks and repolarization abnormalities have been widely reported. (17) The arrhythmia is more common in nocturnal, prolonged and generalized seizures (18, 19). Tachyarrhythmia before, during and after the seizures are more commonly encountered, compared to bradyarrhythmia, with rates of 50–100% and <5% respectively but ictal asystole was reported as low as 0.3% (17, 20, 21). Tachycardia is even more common in right sided and temporal onset seizures. Ictal asystole, albeit rare, mostly happens in drug-resistant patients with a possible link to the ictal bradycardia (22, 23). Other than arrhythmia, transient abnormalities such as neurogenic left ventricular stunning and Takatsubo cardiomyopathy have also been reported (24).

Pathological studies have shown myocyte hypertrophy and fibrosis in 25% of the SUDEP cases. However, no difference has been shown between epilepsy, SUDEP and trauma cases in regard of cardiac fibrosis (25).

RESPIRATORY DYSFUNCTION

Respiratory dysfunction appears to be as important as cardiac dysfunction hypothesis in SUDEP pathogenesis. Ictal and peri-ictal respiratory dysfunction is a well-known phenomenon and even a possible biomarker in identifying the patients at risk for SUDEP since it might be signifying the beginning of the process leading up to a terminal apnea and asystole (26, 27). Apnea, particularly of central origin is more common in hemispheric involvement. Limbic temporal areas are believed to play a critical role in coordination of respiration. Propagation of the seizure activity to these areas can derange breathing along with concomitant tachycardia (28–30). Nobis et al. showed that stimulation of the amygdala induced an apnea in their case series, which could have been overcome entirely via breathing through the mouth before the electrical stimulation (31). Periaqueductal grey matter is another important regulator of the respiration and it was disclosed that seizures including this area caused cardiorespiratory dysfunction in mice (32).

On the other hand, pulmonary edema is so commonly observed, being a finding that it is almost a hallmark of the SUDEP autopsies. The pulmonary edema appears due to a physiologic left to right shunt and centrally mediated vascular effects (33). Brain under stress triggers a massive adrenergic release, causing a systemic and pulmonary vascular vasoconstriction, leading to an increased hydrostatic pressure in capillaries and increase in capillary permeability (34). The inflammatory mediators secondary to endothelial damage further facilitate the edema formation (35, 36). Oxygen desaturations are associated with end tidal carbon dioxide rise under certain levels, which do not respond to an increased respiratory effort, also supporting the pulmonary dysfunction theory (37).

Although the hypoxemia is primarily of central origin, peripheral vasoconstriction likely contributes to the general hypoxic state as well (38, 39). Upper airway restriction accompanying 1/3 of the seizures and ictal laryngospasm are other possible contributors to the hypoxia and apneic response (26, 27, 40).

AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM DYSREGULATION

Autonomic nervous system is believed to play a major role in SUDEP pathogenesis and heart rate variability (HRV) appears to be the major component of the SUDEP pathogenesis related to the autonomic nervous system. A recent study performed by Meyers et al. showed that lower awake HRV and extremely high or extremely low sleep to awake HRV ratios were associated with SUDEP risk. This was more prominent in patients with sodium channel mutations (41).

The circadian rhythmicity of the HRV dysregulation is further noted in other studies, reported to be worst in 5–6:00 am, which can partly explain the timing of the SUDEP cases since they are most likely to occur during night and in the early morning (42, 43).

Imaging studies provide further evidence for the autonomic dysfunction. A resting state fMRI study showed widespread functional connectivity differences between autonomic regulatory brain regions in temporal lobe epilepsy patients, who are at high risk for SUDEP compared to ones at low risk (44). Mueller et al. also reported that brainstem atrophy expanding into mesencephalon impairs autonomic control and increases the risk of SUDEP (45).

AROUSAL SYSTEM DYSFUNCTION

Arousal failure following a seizure is another speculated contributing mechanism in SUDEP patients. Ascending arousal system located in the brainstem can be affected by a seizure via spreading ictal activity itself or by the global inhibitory response, leading to loss of consciousness, disruption of protective responses and possibly the failure of proper regulation of the cardiorespiratory systems as well as autonomic nervous system (37). Patodia et al. has also disclosed reduction in neuromodulatory neuropeptidergic and monoaminergic neuronal populations in the medulla in SUDEP cases, pointing out to an already established anatomopathological background regarding the brainstem arousal mechanisms (46).

Postictal generalized electroencephalographic suppression (PGES) occurring after GTCS is strongly associated with severe hypoxemia and arrhythmias. The relation between the length of PGES and SUDEP risk is speculative due to conflicting results in the literature. However, Tang et al. have shown that PGES and SUDEP cases share a significant anatomical finding which is thinning of the right sided cortical structures, intriguingly (47–49). Lhatoo et al. suggested that since PGES is a global depression of the cortical electrical activity, it may lead to inhibition of respiratory areas especially in the brainstem, leading to a central apnea and henceforth to SUDEP.

It was important to note that postictal arousal problems may benefit from early nursing interventions such as stimulation, positioning and correction of hypoxemia, similar to apnea induced by amygdalar stimulation, therefore supplying us a possible window for prevention (50).

OTHER HYPOTHESES

Some neurotransmitters and neuromodulators have also been hypothesized to be associated with the SUDEP pathogenesis. Serotonin, playing vital roles in arousal and breathing regulation, is the mostly investigated neurotransmitter in this regard. Suppression of the serotonergic neurons during seizure can cause hypoventilation and this can lead to prolonged PGES duration postictally (51, 52). A study in humans showed that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be of aid in reducing the peri-ictal hypoxemia in focal seizures (53). However, this effect was not observable following GTCS.

Another cited neurotransmitter, adenosine, is predominantly inhibitor in nature. Due to its inhibitory effect, which is in charge as a possible in vivo antiepileptic mechanism, it also inhibits respiratory centers, therefore increasing SUDEP in mice epilepsy models (54). A powerful adenosine receptor inhibitor caffeine is reported to decrease SUDEP incidence in those mice, remarkably. The impaired adenosine clearance might be another contributor of the SUDEP pathogenesis.

Moreover, many mutations and related channelopathies are associated with increased SUDEP risk. Explanation of all these mutations and their mechanisms is beyond the scope of this review. For a mutation to be named as a SUDEP gene, it should “cause epilepsy and increase SUDEP risk via central or peripheral nervous system or end organ effects on respiratory, cardiac, or other autonomic functions” (55). The SCN1A mutation of the Dravet syndrome deserves a special attention here; the mutated Na channels lead to both seizures and cardiac conduction defects, increasing the SUDEP risk (56, 57).

A new and interesting hypothesis is the “ictal mammalian dive response” (MDR) (58). MDR in an autonomic response to submersion starting with an apnea, followed by diving bradycardia and peripheral vasoconstriction and splenic contraction with an accompanying shunting of the blood to the cardiopulmonary vasculature and hypertension in humans. It represents an oxygen conserving mechanism. The reflex is elicitable via a prolonged voluntary apnea without the water contact to the facial structures. The apnea induced by seizure might trigger this “oxygen preserving” mechanism, however without the control of a failing brain due to seizure and other pathological processes secondary to the seizure, this specific mechanism leads to an asystole and terminal apnea, causing SUDEP. This hypothesis is further supported by Cihan et al.’s findings; an autopsy study found that epilepsy related drowning and SUDEP cases were indistinguishable via autopsy (59).

RISK FACTORS

Defining risk factors for such a complex and uncovered multifactorial phenomenon is a difficult task. Scant number of the cases in the company of heterogeneity of the factors together with conflicting findings reported in the studies complicate further the process of defining certain risk factors. This attempt requires a profound apprehension of the pathophysiological process and prospective studies based on that knowledge. However, our knowledge regarding the pathophysiological basis of the SUDEP is still just in the level of hypotheses, as explained above. Nonetheless, based on the pooled information over the years, some risk factors stand out as remarkable, and will be discussed in this section (Table 2). These risk factors can be examined in three groups: static, genetic and modifiable risk factors.

Table 2.

Top risk factors for SUDEP (modified from DeGiorgio) (6)

| • ≥3 GTCS per year |

| • ≥13 seizures in the last year |

| • No AED treatment |

| • ≥3 AEDs |

| • 11–20 GTCS in the last 3 months |

| • Age at onset of 0–15 years |

| • IQ <70 |

| • 3–5 AED changes in the last year |

SUDEP, sudden unexpected death in epilepsy; GTCS, generalized tonic clonic seizure; AED, antiepileptic drugs; IQ, intelligence quotient.

Static risk factors:

Static risk factors consist of demographic factors, mostly. Male gender, early age of seizure onset (<16 years of age), longer duration of the epilepsy (>15 years), age between 20–40 years and intellectual disability are the most consistently described static risk factors (60, 61).

Genetic risk factors:

There are many SUDEP genes, and new ones are added to the list day by day. As mentioned in the pathophysiology section, genes transcribed in multiple systems such as SCN1A can effect sodium channels in heart and brain leading to seizures and cardiac rhythm abnormalities, increasing the risk of SUDEP. Many of the proposed genes and candidates appear to overlap with the genes accountable for sudden cardiac death (62–64). Many sodium and potassium channel mutations have been associated with an increase in SUDEP risk for that matter (41, 65). A specific sodium channel mutation SCN8A has been especially associated with high SUDEP rate (66). Mutations in ryanodine, µ-opiod signaling pathway, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate-mediated synaptic signaling genes have also been reported (62). But it should be kept in mind that even “benign” syndromes may cause SUDEP, as reported in 3 boys with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (67).

Modifiable risk factors:

From a clinical point of view, the most important challenge is to enlighten the modifiable SUDEP risk factors, since they can be intervened in order to reduce the SUDEP risk.

Seizure profile is the most consistently reported risk factor for SUDEP in all studies. Presence of GTCS, frequency of the GTCS (>3 per year), not being seizure free for 1–5 years and nocturnal seizures are associated with an increase in SUDEP risk (4, 6, 68, 69). Maximizing seizure control, if possible to the point of less than 3 GTCS per year is known to be one of the most effective strategy against SUDEP (60). Nocturnal seizures are associated with more severe and longer hypoxemia, PGES and lower probability to be intervened by a caregiver, therefore they need special attention for the increase of SUDEP risk (69).

Origin of the seizures, on the other hand, is also mentioned as a risk factor. Extratemporal lobe seizures are reported to manifest a higher risk for SUDEP (4, 70). This might be due to the structures involved in the extratemporal seizures, worse outcomes with epilepsy surgery and harder to control seizures (71).

Other items regarding the seizure characteristics with indecisive evidence are prone position, postictal immobility and PGES (47, 50, 72–74). Prone position and postictal immobility are believed worsen respiratory problems and increase the chance of suffocation. Postictal immobility is also related to PGES.

Treatment is of utmost importance as a modifiable risk factor for daily practice. Lack of appropriate antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment, more than 3 AEDs necessity, frequent AED changes (3–5 AED changes in the last year) are amongst the top 10 risk factors for SUDEP (4, 6). Higher number of AEDs prescribed overall is also associated with an increase in SUDEP risk (4, 75). However, Rylvin et al. has reported that introducing new AEDs or adjunctive treatments for drug-resistant seizures reduce the incidence of SUDEP compared to placebo (4, 76). Therefore, the increased risk due to higher number of AED is possibly reflecting the refractoriness of the seizures and longer duration of the disease. On the other hand, there is a study reporting polytherapy as an independent risk factor after adjusting for confounders such as seizure frequency and proposing the cardiac side effects as the underlying mechanism, however these results have not been replicated by other studies (60, 77).

Specific AEDs have been proposed to increase the risk of SUDEP over the years, but supporting evidence was found only for lamotrigine therapy in women with IGE and GTCSs, surprisingly (4, 60, 78, 79).

Non-adherence to the therapy is a further important risk factor as it may have devastating results on the disease course too (80). Non-compliance with the therapy and subtherapeutic AED levels are associated with an increase in SUDEP risk in most of the relevant studies (60, 61, 81).

Follow up planning came out as another important step for reducing SUDEP, as it has been shown that mortality due to SUDEP decreases with longer follow up as much as 7% per year (7).

Lifestyle factors such as alcohol misuse and loneliness pose a risk for an increase in SUDEP (12, 60, 61).

Comorbidities, especially psychiatric comorbidities are known to increase the risk for SUDEP and early diagnosis and effective treatment are indispensable (12, 82). As noted above, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors might also aid in reduction of postictal apnea and therefore may collaterally assist in reducing the SUDEP risk (53). On the contrary, it is also important to keep in mind that some drugs such as anxiolytics and antipsychotics are associated with an increase in SUDEP risk, so planning the treatment requires further refinement and a good communication between neurologists and psychiatrists (4, 83).

General health status of the subjects is of importance for the SUDEP and SUDEP plus definitions. Underlying health problems, like arrhythmia and sleep related breathing problems, especially obstructive sleep apnea are more common in epileptic population; furthermore they also pose rather easily modifiable risk factors for SUDEP, when properly recognized and treated (84, 85).

Children require a special attention in regard of SUDEP due to diversity of their epileptic syndromes, clinical picture and treatment options. Etiology related factors such as genetic syndromes and comorbidities like cardiac and respiratory problems are far more intricate in pediatric population. Lack of proper communication/cooperation and resistance against treatment might pose bigger problems. Acute changes in physical health even due to minor problems such as fever or flu could accentuate the risk more prominently in children compared to adult counterparts (86).

APPRAISING THE SUDEP RISK: INVENTORIES AND BIOMARKERS

Despite the disturbing fact that all epilepsy patients, even those with an entirely benign syndrome bear a risk for SUDEP, the risk is not the same for each and every patient. Stratifying the patients according to risk groups and identifying the ones with the highest risk of SUDEP is important not only for everyday practical challenges, but also for developing prospective preventive measures and also testing potential therapeutic strategies. Electrophysiological biomarkers and inventories based on historical factors are necessary for such matter. Electroencephalographic findings, especially ictal recordings, prolonged ECG findings and new imaging modalities can provide valuable information in the expanse of time and money, but they are impractical in the busy setting of an outpatient clinic and not readily available in all facilities worldwide. However, inventories such as SUDEP-7 are based on historical data, therefore they are quick and easy to use in such settings.

Biomarkers for SUDEP are mostly acquired from electrophysiological and neuro-imaging studies. Electrocardiograms, especially ictal heart rate changes provide an important and well-investigated clue for SUDEP. High maximal ictal heart rates, cardiac repolarization abnormalities (QT interval shortening or lengthening) and rhythm abnormalities are associated with increased SUDEP risk (87–90). Ictal bradycardia and asystole, which are less commonly observed compared to tachycardia, are more likely to be a part of SUDEP process rather than a standing risk factor (55, 91).

Heart rate variability is also another important indicator, as stated above. Low HRV is associated with an increased SUDEP risk. Circadian rhythmicity of the HRV should also be evaluated since extremely high or extremely low sleep to awake HRV ratios are also associated with an increased risk (41, 43, 92).

Respiration provides valuable information regarding the SUDEP risk of the patient. Ictal hypoxemia, hypoventilation, apnea and increased end-tidal carbon dioxide are potential biomarkers for an impending SUDEP (16).

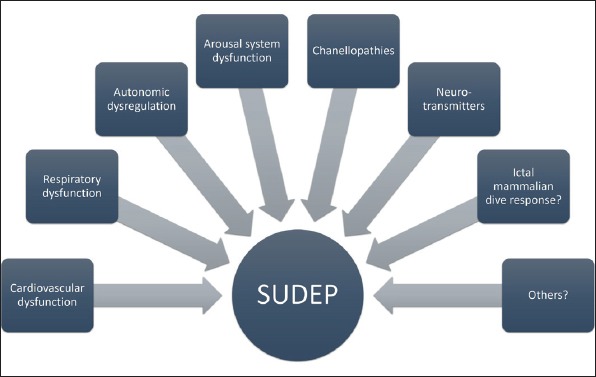

Electroencephalography can reveal PGES, which is considered as an important biomarker for SUDEP, especially if it lasts longer than 80 seconds (Figure 2) (47).

Figure 2.

Low pass filter, 70 Hz; High pass filter, 0.5 Hz; Notch filter, 50 Hz; Sensitivity, 100 µV.

An example of postictal generalized electroencephalographic suppression in EEG following a generalized tonic clonic seizure.

Magnetic resonance imaging and functional MRI (fMRI) are luscious modalities to search for a biomarker since they are already a routine part of the evaluation process of epilepsy. Although some findings are promising, none of the studies have succeeded to point a single abnormality as a biomarker yet. Brainstem atrophy, volume loss in the critical structures such as posterior thalamus and impaired connectivity are the strongest candidates, so far.

Inventories are more practical tools in the clinical setting and more suitable for widespread screening. The idea of developing an inventory to foresee SUDEP risk has led to SUDEP-7 inventory using most validated risk factors as items of the inventory (Table 3) (75, 92). The inventory has been associated with some of the biomarkers of SUDEP risk such as HRV and PGES (75, 93, 94). On the other hand, a more recent study has claimed that there is no significant difference in SUDEP-7 scores, ILAE scores and physiological biomarkers such as HRV, peri-ictal cardiorespiratory measures and PGES between SUDEP cases and controls (95).

Table 3.

SUDEP-7 risk factor inventory (92)

| 1. More than 3 tonic-clonic seizures in past year | 0 or 2 |

| 2. One or more tonic-clonic seizures in past year (Don’t score if risk factor 1 is selected) | 0 or 1 |

| 3. One or more seizures of any type over the past 12 months (Don’t score if risk factor 4 is selected) | 0 or 1 |

| 4. >50 seizures of any type per month over the past 12 months | 0 or 2 |

| 5. Duration of epilepsy ≥30 years | 0 or 3 |

| 6. Current use of 3 or more AED | 0 or 1 |

| 7. Mental retardation, IQ <70, too impaired to test | 0 or 2 |

SUDEP, sudden unexpected death in epilepsy; AED, antiepileptic drugs; IQ, intelligence quotient.

There are also other inventories and check lists in the literature such as; SUDEP safety checklist, SUDEP safety checklist for caretakers, EpSMon and top 10 risk factors, that are more of structured communication tools rather than appropriate risk assessment tools (6, 80, 96, 97).

In conclusion, there are yet no perfect biomarkers or inventories that can distinguish which individual is going to die due to SUDEP.

PREVENTION MEASURES

Effective seizure control lies in the heart of SUDEP prevention. Appropriate AED treatment regimens are the first step to achieve seizure freedom, which is possible in two thirds of the patients, with currently available medical treatment options. Sadly, one third of epilepsy patients will not be seizure free under AEDs alone and necessitate further evaluation by a comprehensive epilepsy center and additional treatment modalities such as epilepsy surgeries and neural stimulators.

Epilepsy surgery is associated with a dramatic decrease in SUDEP risk but only if it is successful (98). The expected SUDEP rates drop from 6.3–9.3 to 1.8–4.0 per 1000 patient years following successful resective surgery (91). Sperling et al. also showed that epilepsy surgery is associated with reduced mortality in suitable patients compared to AED treatment alone (99). Unfortunately, epilepsy surgery programs are expensive and not available for many drug-resistant patients in different parts of the world.

Palliative measures such as vagal nerve stimulators (VNS) and less commonly used emerging options like deep brain stimulators (DBS) and responsive neurostimulation (RNS) should be considered in patients with drug-resistant seizures who are not suitable candidates for resective surgery. A number of studies have shown consistently that VNS significantly reduces SUDEP risk (100–103). The risk reduction is more pronounced in the first two years following implantation, thereafter it somewhat stabilizes (101, 102). Although VNS has been suspected to facilitate the SUDEP via cardiac arrhythmia and suppression of respiration, no studies have furnished satisfactory evidence for this speculation (104). The data on DBS and RNS are even more scarce. They are rather new interventions, RNS was licensed in 2011 and DBS in 2018 by FDA. Both of them are not licensed by Turkish authorities yet. SANTE study has shown beneficial effects of bilateral anterior thalamic nuclei stimulation via DBS on seizure control, however, no satisfactory data on SUDEP was noted (105). Devinsky et al. reported a modest rate of SUDEP (2.0/1000 patient-stimulation years) with a favorable seizure control with RNS systems (106). Bergey et al. reported 3.5 per 1000 patient-stimulation years again with favorable seizure control and safety profile for RNS systems in focal epilepsy patients (107).

Seizure prediction and detection devices use different modalities with various pros and cons of each system. A recent Cochrane review has shown that overall evidence for these devices was limited to suggest a decreased risk (108, 109). Another review has shown that sensitivity ranged from 4–100% and false detection rates were 0.25 to 20 per 8 hours for these systems but GTCS were detected with an acceptable success rate (110). Since GTCS are the seizure types bearing the highest risk for SUDEP and other secondary problems, it may be feasible to use such systems. Multimodal detection systems may increase the sensitivity and specificity (111).

The seizure detection tools can be grouped into two categories: EEG based and non EEG based systems (112). EEG based systems are capable of detecting all seizure events in theory and EMG based systems are capable of detecting only major seizures with motor phenomena (113, 114). Other biological data such as ECG, HRV, oxygen saturation, apnea detection, electrodermal activity and baroreflex sensitivity and accelerometers have all been used alone or in combination with other systems with different success rates (115–122). There are not any devices that can properly detect apnea in the home setting yet, and oximetry devices lag between apnea and hypoxemia for too long, giving rise to a great lag in resuscitation attempts, therefore missing the possible therapeutic window of first three minutes (16). However, wearable apnea detection devices, although necessitating further studies, appear to be promising for such purpose (117).

Other systems based on audio input, pressure sensor mats and video monitoring are commercially available, however the clinical trials and data regarding the sensitivity and specificity are scant or lacking for each system (123–127).

Nocturnal monitoring has rather strong evidence supporting the benefit. Studies evaluating residential care settings have clearly shown decreased SUDEP incidence with some form of nocturnal supervision (68.76.128). This supervision can be provided by a person (preferably over the age of 10 years and of normal intelligence) or audio and video monitors (4, 78, 128). However, the ethical issues associated with the nocturnal supervision are controversial since it defiles the privacy of the person with epilepsy (129). Seizure alert dogs could provide a more private precaution for selected patients.

Early nursing interventions following a seizure could provide great benefit, even prevent the impending SUDEP. Stimulation and repositioning are the first steps to avoid suffocation and stimulate the respiration. Somatosensory and auditory stimulation in addition to suctioning and supplemental oxygen administration can aid in alleviating the respiratory dysfunction, PGES and immobility, possibly partly due to enhanced state of arousal (130).

Supplemental oxygen use is controversial since it is shown to be beneficial in the early period of hypoxemia but does not work in the cases of central apnea or intrapulmonary shunts. Direct evidence of benefit is shown only in animal studies and these findings are failed to be replicated in human subjects (128, 131). It also bears risks such as burns and etc. in the home setting use (131, 132).

Medical agents such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors, opiate receptor inhibitors and adenosine receptor inhibitors are suggested to attenuate the SUDEP risk (4, 53, 54, 83, 91). Beta blockers are reported to be beneficial in a case with near SUDEP caused by a reversible Takatsubo cardiomyopathy (133). Although some of these drugs are beneficial for the treatment of comorbidities such as depression that can contribute to the SUDEP risk, some other substances, like an adenosine receptor blocker caffeine might have detrimental effects by means of proconvulsant effects (134). There are yet no satisfactory evidence for suggesting any of these medications to prevent SUDEP (135). On the other hand, avoidance of some drugs such as anxiolytics and opiates unless they are strictly necessary is a sensible precaution in patients with epilepsy.

Cardiac pacemakers are already used in patients with ictal asystole to prevent further episodes and falls associated with it, but there are no systemic studies testing for the effectivity of the permanent pacemakers (136, 137). In theory, it is expected to be helpful in cases with defined bradycardia and asystole but definitive selection criteria for the appropriate patients do not exist yet. Lack of effectivity is expected if bradyarrhythmia is a result of the hypoxemia and in cases with tachyarrhythmia. For the latter, implantable intracardiac defibrillators may be appropriate. Other concerns such as MRI compatibility are obsolete and insertion is a relatively safe procedure (65, 91, 138, 139).

Pillows and bedding changes might be important contributors in prevention strategies. Since prone position is associated with an increase in SUDEP risk, the airway obstruction and suffocation is believed to contribute to the pathophysiological process. Anti-suffocation pillows such as lattice pillows and proper bedding changes such as fitted sheets might decrease risk (140, 141). A recent video EEG monitoring unit study, investigating patients in peri-ictal prone positions elucidated that SUDEP-7 scores were significantly higher in the prone (+) group. Nocturnal supervision and appropriate positioning become important to reduce SUDEP risk, especially in patients with mental retardation (4, 74).

Awareness programs, discussions and apps (such as EpSMon) are also important strategies, as well as structured discussions about SUDEP with the patients and caregivers, which leads to a decrease in SUDEP risk. (142) Self-monitoring apps like EpSMon also help the patients to regain the control of their lives and provide better information to their doctors (143).

HOW AND WHEN TO COMMUNICATE WITH THE PATIENTS AND CAREGIVERS

Talking about SUDEP with patients and their caregivers is a tricky business. It carries an emotional burden and anxiety not only for the patient but also for the physician. Still, research consistently shows that the patients and their families prefer to be informed and it is their right to know even if the probability of such an event is extremely low (144, 145). In a study, over 90% of the patients wanted the SUDEP discussion for themselves and over 70% wanted SUDEP discussion with their child (146). Parents were more certain on this issue; in a study all participants claimed that all parents with a child with epilepsy should be informed on SUDEP risk (147). Another study revealed that three quarters of family members wished they had known of SUDEP before the death (148).

To talk about the SUDEP risk, firstly the physician should be well informed about it. According to the Berl et al., 75.3% of the pediatric care providers were unaware of the SUDEP risk, and, the ones that are aware were assuming the neurologist told the family about the risks (149). Another study reported that, in a survey of clinicians in Italy, 55% of the responders admitted they did not possess adequate communication skills to discuss SUDEP (150). To have thorough knowledge about SUDEP and to obtain associated communication skills requires a collaborative effort of clinicians, national societies and educational institutes.

Second question is when should information on SUDEP be disclosed. According to the NICE and SIGN guidelines, information on the risk of SUDEP should be given either at or soon after the diagnosis (151, 152). Despite the fact that every patient is not under the same risk, and stratifying the patients in consonance with these risk ratios and disclosing the SUDEP information accordingly would have been a better option, since perfect risk assessment is not yet possible, it is advisable to inform every patient as soon as the diagnosis is final and a working physician-patient relationship is formed vividly (153).

The information should be personally tailored and conceptual, focusing on the risk of both having and “not having” the event, using numbers and frequencies rather than percentages to prevent overestimation. It should be emphasized that there is a rare risk of SUDEP, as 1 in 4500 children is affected by SUDEP in one year, the 4.499 children will NOT be affected, similar to 1-person vs 999 living people out of 1000 adults (4).

Communicating the SUDEP risk has a couple of advantages. Having the discussion and getting informed leads to better management of the disease and better therapy adherence in addition to allowing the caregivers to taking precautionary measures (142, 145, 146, 154). Clinicians appear to anticipate that patients will be anxious or distressed discussing SUDEP but contrary to the expectations, being informed on SUDEP risk does not have adverse effects on quality of life or mood itself, according to studies (146, 154, 155). Negative reactions to SUDEP discussions are common, however, they do not have long term effects, and proper communication skills combined with experience can minimize them (156).

The discussion also aids in the physician-patient relationship, giving way to a more trustful one compared to the physicians avoiding this disclosure (157). Additionally, discussing SUDEP before such a devastating event ever happens can help the mourning relatives to cope with a loss of loved one. It would also prevent the caregivers to blame themselves or even physician for “all the things they possibly could have done to prevent it”.

TIPS FOR THE FUTURE

SUDEP is a frightening issue, about which we have very little knowledge, so far. Scientific improvement is absolutely necessary in all aspects of this vital topic. Identification and reporting of the SUDEP cases is the first important step and systematic methods in combination with better integrated health systems in order to recognize the cases should be implemented so we can achieve a better understanding of the incidence, circumstances and causes for SUDEP.

Education is vital in all steps of the patient care, from neurologists to pathologists, nurses to caregivers, and most importantly, for the patients. Educational institutions and national societies should arrange devoted meetings in order to educate doctors and patients and plan activities aiming to raise awareness on this topic.

The research on identifying risk factors and biomarkers is the heart of prevention. Such studies focusing on these topics should be supported and encouraged.

The possible ethical and legal dilemmas should be discussed and negotiated by relevant professionals and guidelines for such matters should be developed.

In conclusion, preventing SUDEP is a long road to run rather then walk, and we are only at the starting line of it. As clinicians we have the responsibility to know SUDEP, explain SUDEP to our patients and their caregivers and whenever possible, prevent SUDEP.

Acknowledgement:

This study was supported by the Istanbul University Scientific Research Fund (Project No. 23855).

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - ADE, BB, NB; Design - ADE, BB, NB; Supervision - ADE, BB, NB; Data Collection and/ or Processing - ADE, BB, NB; Analysis and/or Interpretation - ADE, BB, NB; Literature Search - ADE, BB, NB; Writing - ADE, BB, NB; Critical Reviews - ADE, BB, NB.

Financial disclosure and conflict of interest: None of the authors have anything to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nashef L. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy:Terminology and definitions. Epilepsia. 1997;38:S6–S8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb06130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nashef L, So EL, Ryvlin P, Tomson T. Unifying the definitions of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012;53:227–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sander JW, Bell GS. Reducing mortality:an important aim of epilepsy management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:349–351. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.029223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harden C, Tomson T, Gloss D, Buchhalter J, Cross JH, Donner E, French JA, Gil-Nagel A, Hesdorffer DC, Smithson WH, Spitz MC, Walczak TS, Sander JW, Ryvlin P. Practice guideline summary:Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy incidence rates and risk factors. Neurology. 2017;88:1674–1680. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holst AG, Winkel BG, Risgaard B, Nielsen JB, Rasmussen PV, Haunsø S, Sabers A, Uldall P, Tfelt-Hansen J. Epilepsy and risk of death and sudden unexpected death in the young:A nationwide study. Epilepsia. 2013;54:1613–1620. doi: 10.1111/epi.12328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeGiorgio CM, Markovic D, Mazumder R, Moseley BD. Ranking the leading risk factors for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Front Neurol. 2017;8:8–13. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomson T, Sveinsson O, Carlsson S, Andersson T. Evolution over time of SUDEP incidence:A nationwide population-based cohort study. Epilepsia. 2018;59:e120–e124. doi: 10.1111/epi.14460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen S, Joodi G, Devinsky O, Sadaf MI, Pursell IW, Simpson RJ., Jr Under-reporting of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. 2018;20:270–278. doi: 10.1684/epd.2018.0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atherton DS, Davis GG, Wright C, Devinsky O, Hesdorffer D. A survey of medical examiner death certification of vignettes on death in epilepsy:Gaps in identifying SUDEP. Epilepsy Res. 2017;133:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devinsky O, Friedman D, Cheng JY, Moffatt E, Kim A, Tseng ZH. Underestimation of sudden deaths among patients with seizures and epilepsy. Neurology. 2017;89:886–892. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afandi D, Romus I. Autopsy findings of SUDEP in adolescence. Malays J Pathol. 2018;40:185–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sveinsson O, Andersson T, Carlsson S, Tomson T. Circumstances of SUDEP. A nationwide population-based case series. Epilepsia. 2018;59:1074–1082. doi: 10.1111/epi.14079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ba-Armah DM, Donner EJ, Ochi A, Go C, McCoy B, Snead C, Drake J, Jones KC. “Saved by the Bell”:Near SUDEP during intracranial EEG monitoring. Epilepsia Open. 2018;3:98–102. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lhatoo SD, Nei M, Raghavan M, Sperling M, Zonjy B, Lacuey N, Devinsky O. Nonseizure SUDEP. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy without preceding epileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2016;57:1161–1168. doi: 10.1111/epi.13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langan Y, Nashef L, Sander JW. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy:a series of witnessed deaths. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:211–213. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryvlin P, Nashef L, Lhatoo SD, Bateman LM, Bird J, Bleasel A, Boon P, Crespel A, Dworetzky BA, Høgenhaven H, Lerche H, Maillard L, Malter MP, Marchal C, Murthy JMKK, Nitsche M, Pataraia E, Rabben T, Rheims S, Sadzot B, Schulze-Bonhage A, Seyal M, So EL, Spitz M, Szucs A, Tan M, Tao JX, Tomson T. Incidence and mechanisms of cardiorespiratory arrests in epilepsy monitoring units (MORTEMUS):a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:966–977. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70214-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Lende M, Surges R, Sander JW, Thijs RD. Cardiac arrhythmias during or after epileptic seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:69–74. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-310559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nei M, Ho RT, Sperling MR. EKG abnormalities during partial seizures in refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41:542–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opherk C, Coromilas J, Hirsch LJ. Heart rate and EKG changes in 102 seizures:analysis of influencing factors. Epilepsy Res. 2002;52:117–127. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(02)00215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tinuper P, Bisulli F, Cerullo A, Carcangiu R, Marini C, Pierangeli G, Cortelli P. Ictal bradycardia in partial epileptic seizures:Autonomic investigation in three cases and literature review. Brain. 2001;124:2361–2371. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.12.2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moseley BD, Nickels K, Britton J, Wirrell E. How common is ictal hypoxemia and bradycardia in children with partial complex and generalized convulsive seizures? Epilepsia. 2010;51:1219–1224. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rugg-Gunn FJ, Simister RJ, Squirrell M, Holdright DR, Duncan JS. Cardiac arrhythmias in focal epilepsy:a prospective long-term study. Lancet. 2004;364:2212–2219. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17594-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rocamora R, Kurthen M, Lickfett L, Von Oertzen J, Elger CE. Cardiac asystole in epilepsy:clinical and neurophysiologic features. Epilepsia. 2003;44:179–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.15101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nascimento FA, Tseng ZH, Palmiere C, Maleszewski JJ, Shiomi T, McCrillis A, Devinsky O. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) Epilepsy Behav. 2017;73:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devinsky O, Kim A, Friedman D, Bedigian A, Moffatt E, Tseng ZH. Incidence of cardiac fibrosis in SUDEP and control cases. Neurology. 2018;91:e55–e61. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacuey N, Vilella L, Hampson JP, Sahadevan J, Lhatoo S. Ictal laryngospasm monitored by video-EEG and polygraphy:a potential SUDEP mechanism. Epileptic Disord. 2018;20:146–150. doi: 10.1684/epd.2018.0964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart M, Kollmar R, Nakase K, Silverman J, Sundaram K, Orman R, Lazar J. Obstructive apnea due to laryngospasm links ictal to postictal events in SUDEP cases and offers practical biomarkers for review of past cases and prevention of new ones. Epilepsia. 2017;58:e87–e90. doi: 10.1111/epi.13765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaada BR, Jasper H. Respiratory responses to stimulation of temporal pole, insula, and hippocampal and limbic gyri in man. AMA Arch NeurPsych. 1952;68:609–619. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1952.02320230035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonvallet M, Bobo EG. Changes in phrenic activity and heart rate elicited by localized stimulation of amygdala and adjacent structures. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page T, Rugg-Gunn FJ. Bitemporal seizure spread and its effect on autonomic dysfunction. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;84:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nobis WP, Schuele S, Templer JW, Zhou G, Lane G, Rosenow J, Zelano C. Amygdala-stimulation-induced apnea is attention and nasal-breathing dependent. Ann Neurol. 2018;83:460–471. doi: 10.1002/ana.25178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kommajosyula SP, Tupal S, Faingold CL. Deficient post-ictal cardiorespiratory compensatory mechanisms mediated by the periaqueductal gray may lead to death in a mouse model of SUDEP. Epilepsy Res. 2018;147:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terrence CF, Rao GR, Perper JA. Neurogenic pulmonary edema in unexpected, unexplained death of epileptic patients. Ann Neurol. 1981;9:458–464. doi: 10.1002/ana.410090508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao H, Lin G, Shi M, Gao J, Wang Y, Wang H, Sun H, Cao Y. The mechanism of neurogenic pulmonary edema in epilepsy. J Physiol Sci. 2014;64:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s12576-013-0291-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baumann A, Audibert G, McDonnell J, Mertes PM. Neurogenic pulmonary edema. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51:447–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romero Osorio OM, Abaunza Camacho JF, Sandoval Briceño D, Lasalvia P, Narino Gonzalez D. Postictal neurogenic pulmonary edema:Case report and brief literature review. Epilepsy Behav Case Reports. 2018;9:49–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ebcr.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Massey CA, Sowers LP, Dlouhy BJ, Richerson GB. Mechanisms of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy:the pathway to prevention. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:271–282. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nashef L, Walker F, Allen P, Sander JW, Shorvon SD, Fish DR. Apnoea and bradycardia during epileptic seizures:relation to sudden death in epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;60:297–300. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.60.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blum AS, Ives JR, Goldberger AL, Al-Aweel IC, Krishnamurthy KB, Drislane FW, Schomer DL. Oxygen desaturations triggered by partial seizures:implications for cardiopulmonary instability in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41:536–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bateman LM, Li C-S, Seyal M. Ictal hypoxemia in localization-related epilepsy:analysis of incidence, severity and risk factors. Brain. 2008;131:3239–3245. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myers KA, Bello-Espinosa LE, Symonds JD, Zuberi SM, Clegg R, Sadleir LG, Buchhalter J, Scheffer IE. Heart rate variability in epilepsy:A potential biomarker of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy risk. Epilepsia. 2018;59:1372–1380. doi: 10.1111/epi.14438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Z, Liu H, Meng F, Guan Y, Zhao M, Qu W, Hao H, Luan G, Zhang J, Li L. The analysis of circadian rhythm of heart rate variability in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2018;146:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baysal-Kirac L, Serbest NG, Şahin E, Dede HÖ, Gürses C, Gökyiğit A, Bebek N, Bilge AK, Baykan B. Analysis of heart rate variability and risk factors for SUDEP in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;71:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allen LA, Harper RM, Kumar R, Guye M, Ogren JA, Lhatoo SD, Lemieux L, Scott CA, Vos SB, Rani S, Diehl B. Dysfunctional Brain Networking among autonomic regulatory structures in temporal lobe epilepsy patients at high risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Front Neurol. 2017;8:544. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mueller SG, Nei M, Bateman LM, Knowlton R, Laxer KD, Friedman D, Devinsky O, Goldman AM. Brainstem network disruption:A pathway to sudden unexplained death in epilepsy? Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39:4820–4830. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patodia S, Somani A, O'Hare M, Venkateswaran R, Liu J, Michalak Z, Ellis M, Scheffer IE, Diehl B, Sisodiya SM, Thom M. The ventrolateral medulla and medullary raphe in sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Brain. 2018;141:1719–1733. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lhatoo SD, Faulkner HJ, Dembny K, Trippick K, Johnson C, Bird JM. An electroclinical case-control study of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:787–796. doi: 10.1002/ana.22101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Surges R, Strzelczyk A, Scott CA, Walker MC, Sander JW. Postictal generalized electroencephalographic suppression is associated with generalized seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;21:271–274. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang Y, An D, Xiao Y, Niu R, Tong X, Liu W, Zhao L, Gong Q, Zhou D. Cortical thinning in epilepsy patients with postictal generalized electroencephalography suppression. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:191–197. doi: 10.1111/ene.13794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seyal M, Bateman LM, Li C-S. Impact of periictal interventions on respiratory dysfunction, postictal EEG suppression, and postictal immobility. Epilepsia. 2013;54:377–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seyal M, Bateman LM, Albertson TE, Lin TC, Li C-S. Respiratory changes with seizures in localization-related epilepsy:Analysis of periictal hypercapnia and airflow patterns. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1359–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murugesan A, Rani MRS, Hampson J, Zonjy B, Lacuey N, Faingold CL, Friedman D, Devinsky O, Sainju RK, Schuele S, Diehl B, Nei M, Harper RM, Bateman LM, Richerson G, Lhatoo SD. Serum serotonin levels in patients with epileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2018;59:e91–e97. doi: 10.1111/epi.14198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bateman LM, Li C-S, Lin T-C, Seyal M. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors are associated with reduced severity of ictal hypoxemia in medically refractory partial epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2010;51:2211–2214. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen H-Y, Li T, Boison D. A novel mouse model for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP):Role of impaired adenosine clearance. Epilepsia. 2010;51:465–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Devinsky O, Hesdorffer DC, Thurman DJ, Lhatoo S, Richerson G. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy:epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:1075–1088. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frasier CR, Zhang H, Offord J, Dang LT, Auerbach DS, Shi H, Chen C, Goldman AM, Eckhardt LL, Bezzerides VJ, Parent JM, Isom LL. Channelopathy as a SUDEP Biomarker in Dravet Syndrome Patient-Derived Cardiac Myocytes. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;11:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dede HÖ, Gelişin Ö, Baykan B, Çağlayan H, Topaloğlu P, Gürses C, Bebek N, Gökyiğit A. Dravet sendromunda kesin SUDEP. Erişkin bir olgu sunumu. J Neurol Sci [Turk] 2015;32:610–616. Available at: https://nsnjournal.org/sayilar/102/buyuk/pdf_JNS_910.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vega JL. Ictal Mammalian Dive Response:A likely cause of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Front Neurol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cihan E, Hesdorffer DC, Brandsoy M, Li L, Fowler DR, Graham JK, Donner EJ, Devinsky O, Friedman D. Dead in the water:Epilepsy-related drowning or sudden unexpected death in epilepsy? Epilepsia. 2018;59:1966–1972. doi: 10.1111/epi.14546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hesdorffer DC, Tomson T, Benn E, Sander JW, Nilsson L, Langan Y, Walczak TS, Beghi E, Brodie MJ, Hauser A ILAE Commission on Epidemiology;Subcommission on Mortality. Combined analysis of risk factors for SUDEP. Epilepsia. 2011;52:1150–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomson T, Surges R, Delamont R, Haywood S, Hesdorffer DC. Who to target in sudden unexpected death in epilepsy prevention and how?Risk factors, biomarkers, and intervention study designs. Epilepsia. 2016;57:4–16. doi: 10.1111/epi.13234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedman D, Kannan K, Faustin A, Shroff S, Thomas C, Heguy A, Serrano J, Snuderl M, Devinsky O. Cardiac arrhythmia and neuroexcitability gene variants in resected brain tissue from patients with sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) NPJ Genom Med. 2018;3:9. doi: 10.1038/s41525-018-0048-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goldman AM, Behr ER, Semsarian C, Bagnall RD, Sisodiya S, Cooper PN. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy genetics:Molecular diagnostics and prevention. Epilepsia. 2016;57:17–25. doi: 10.1111/epi.13232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bagnall RD, Crompton DE, Petrovski S, Lam L, Cutmore C, Garry SI, Sadleir LG, Dibbens LM, Cairns A, Kivity S, Afawi Z, Regan BM, Duflou J, Berkovic SF, Scheffer IE, Semsarian C. Exome-based analysis of cardiac arrhythmia, respiratory control, and epilepsy genes in sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:522–534. doi: 10.1002/ana.24596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ruthirago D, Julayanont P, Karukote A, Shehabeldin M, Nugent K. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy:ongoing challenges in finding mechanisms and prevention. Int J Neurosci. 2018;128:1052–1060. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2018.1466780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johannesen KM, Gardella E, Scheffer I, Howell K, Smith DM, Helbig I, Møller RS, Rubboli G. Early mortality in SCN8A-related epilepsies. Epilepsy Res. 2018;143:79–81. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Doumlele K, Friedman D, Buchhalter J, Donner EJ, Louik J, Devinsky O. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy among patients with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:645–649. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van der Lende M, Hesdorffer DC, Sander JW, Thijs RD. Nocturnal supervision and SUDEP risk at different epilepsy care settings. Neurology. 2018;91:e1508–e1518. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lamberts RJ, Thijs RD, Laffan A, Langan Y, Sander JW. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy:People with nocturnal seizures may be at highest risk. Epilepsia. 2012;53:253–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Almeida AG, Nunes ML, Palmini ALF, Costa JC. Incidence of SUDEP in a cohort of patients with refractory epilepsy:the role of surgery and lesion localization. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2010;68:898–902. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2010000600013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sarkis RA, Jehi L, Bingaman W, Najm IM. Seizure worsening and its predictors after epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. 2012;53:1731–1738. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liebenthal JA, Wu S, Rose S, Ebersole JS, Tao JX. Association of prone position with sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Neurology. 2015;84:703–709. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shmuely S, Surges R, Sander JW, Thijs RD. Prone sleeping and SUDEP risk:The dynamics of body positions in nonfatal convulsive seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;62:176–179. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oguz Akarsu E, Şahin E, Ozel Yildiz S, Bebek N, Gürses C, Baykan B. Peri-ictal prone position is associated with ındependent risk factors for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy:a controlled video-EEG monitoring unit study. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2018;49:197–205. doi: 10.1177/1550059417733385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Walczak TS, Leppik IE, D'Amelio M, Rarick J, So E, Ahman P, Ruggles K, Cascino GD, Annegers JF, Hauser WA. Incidence and risk factors in sudden unexpected death in epilepsy:a prospective cohort study. Neurology. 2001;56:519–525. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ryvlin P, Cucherat M, Rheims S. Risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy in patients given adjunctive antiepileptic treatment for refractory seizures:a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomised trials. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:961–968. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tomson T, Kennebäck G. Arrhythmia, Heart Rate Variability, and Antiepileptic Drugs. Epilepsia. 1997;38:S48–S51. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb06128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Langan Y, Nashef L, Sander JW. Case-control study of SUDEP. Neurology. 2005;64:1131–1133. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000156352.61328.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aurlien D, Larsen JP, Gjerstad L, Taubøll E. Increased risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy in females using lamotrigine:A nested, case-control study. Epilepsia. 2012;53:258–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shankar R, Cox D, Jalihal V, Brown S, Hanna J, McLean B. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP):Development of a safety checklist. Seizure. 2013;22:812–817. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Latreille V, Abdennadher M, Dworetzky BA, Ramel J, White D, Katz E, Zarowski M, Kothare S, Pavlova M. Nocturnal seizures are associated with more severe hypoxemia and increased risk of postictal generalized EEG suppression. Epilepsia. 2017;58:e127–e131. doi: 10.1111/epi.13841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Faingold CL, Tupal S, Randall M. Prevention of seizure-induced sudden death in a chronic SUDEP model by semichronic administration of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nilsson L, Farahmand BY, Persson PG, Thiblin I, Tomson T. Risk factors for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy:a case-control study. Lancet. 1999;353:888–893. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)05114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McCarter AR, Timm PC, Shepard PW, Sandness DJ, Luu T, McCarter SJ, Dueffert L, Dresow M, Feemster JC, Cascino GD, So EL, Worrell GA, Britton JW, Sherif A, Jaliparthy K, Chahal AA, Somers VK, St Louis EK. Obstructive sleep apnea in refractory epilepsy:A pilot study investigating frequency, clinical features, and association with risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2018;59:1973–1981. doi: 10.1111/epi.14548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Billakota S, Odom N, Westwood AJ, Hanna E, Pack AM, Bateman LM. Sleep-disordered breathing, neuroendocrine function, and clinical SUDEP risk in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;87:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Saxena A, Jones L, Shankar R, McLean B, Newman CGJ, Hamandi K. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy in children:a focused review of incidence and risk factors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89:1064–1070. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nei M, Ho RT, Abou-Khalil BW, Drislane FW, Liporace J, Romeo A, Sperling MR. EEG and ECG in sudden unexplained death in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2004;45:338–345. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.05503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Johnson JN, Hofman N, Haglund CM, Cascino GD, Wilde AA, Ackerman MJ. Identification of a possible pathogenic link between congenital long QT syndrome and epilepsy. Neurology. 2009;72:224–231. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000335760.02995.ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dasheiff RM, Dickinson LJ. Sudden unexpected death of epileptic patient due to cardiac arrhythmia after seizure. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:194–196. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1986.00520020080028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Surges R, Taggart P, Sander JW, Walker MC. Too long or too short?New insights into abnormal cardiac repolarization in people with chronic epilepsy and its potential role in sudden unexpected death. Epilepsia. 2010;51:738–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.DeGiorgio CM, Curtis A, Hertling D, Moseley BD. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy:Risk factors, biomarkers, and prevention. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;139:220–230. doi: 10.1111/ane.13049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.DeGiorgio CM, Miller P, Meymandi S, Chin A, Epps J, Gordon S, Gornbein J, Harper RM. RMSSD, a measure of vagus-mediated heart rate variability, is associated with risk factors for SUDEP. The SUDEP-7 Inventory. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;19:78–81. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Novak JL, Miller PR, Markovic D, Meymandi SK, DeGiorgio CM. Risk Assessment for Sudden Death in Epilepsy:The SUDEP-7 Inventory. Front Neurol. 2015;6:252. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moseley BD, DeGiorgio CM. The SUDEP Risk Inventory:Association with postictal generalized EEG suppression. Epilepsy Res. 2015;117:82–84. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Odom N, Bateman LM. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, periictal physiology, and the SUDEP-7 Inventory. Epilepsia. 2018;59:e157–e160. doi: 10.1111/epi.14552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shankar R, Walker M, McLean B, Laugharne R, Ferrand F, Hanna J, Newman C. Steps to prevent SUDEP. the validity of risk factors in the SUDEP and seizure safety checklist:a case control study. J Neurol. 2016;263:1840–1846. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Young C, Shankar R, Henley W, Rose A, Cheatle K, Sander JW. SUDEP and seizure safety communication:Assessing if people hear and act. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;86:200–203. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sperling MR, Feldman H, Kinman J, Liporace JD, O'Connor MJ. Seizure control and mortality in epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:45–50. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199907)46:1<45::aid-ana8>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sperling MR, Barshow S, Nei M, Asadi-Pooya AA. A reappraisal of mortality after epilepsy surgery. Neurology. 2016;86:1938–1944. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Granbichler CA, Nashef L, Selway R, Polkey CE. Mortality and SUDEP in epilepsy patients treated with vagus nerve stimulation. Epilepsia. 2015;56:291–296. doi: 10.1111/epi.12888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Annegers JF, Coan SP, Hauser WA, Leestma J. Epilepsy, vagal nerve stimulation by the NCP system, all-cause mortality, and sudden, unexpected, unexplained death. Epilepsia. 2000;41:549–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Annegers JF, Coan SP, Hauser WA, Leestma J, Duffell W, Tarver B. Epilepsy, vagal nerve stimulation by the NCP system, mortality, and sudden, unexpected, unexplained death. Epilepsia. 1998;39:206–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ryvlin P, So EL, Gordon CM, Hesdorffer DC, Sperling MR, Devinsky O, Bunker MT, Olin B, Friedman D. Long-term surveillance of SUDEP in drug-resistant epilepsy patients treated with VNS therapy. Epilepsia. 2018;59:562–572. doi: 10.1111/epi.14002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Giordano F, Zicca A, Barba C, Guerrini R, Genitori L. Vagus nerve stimulation:Surgical technique of implantation and revision and related morbidity. Epilepsia. 2017;58:85–90. doi: 10.1111/epi.13678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fisher R, Salanova V, Witt T, Worth R, Henry T, Gross R, Oommen K, Osorio I, Nazzaro J, Labar D, Kaplitt M, Sperling M, Sandok E, Neal J, Handforth A, Stern J, DeSalles A, Chung S, Shetter A, Bergen D, Bakay R, Henderson J, French J, Baltuch G, Rosenfeld W, Youkilis A, Marks W, Garcia P, Barbaro N, Fountain N, Bazil C, Goodman R, McKhann G, Babu Krishnamurthy K, Papavassiliou S, Epstein C, Pollard J, Tonder L, Grebin J, Coffey R, Graves N SANTE Study Group. Electrical stimulation of the anterior nucleus of thalamus for treatment of refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2010;51:899–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Devinsky O, Friedman D, Duckrow RB, Fountain NB, Gwinn RP, Leiphart JW, Murro AM, Van Ness PC. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy in patients treated with brain-responsive neurostimulation. Epilepsia. 2018;59:555–561. doi: 10.1111/epi.13998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bergey GK, Morrell MJ, Mizrahi EM, Goldman A, King-Stephens D, Nair D, Srinivasan S, Jobst B, Gross RE, Shields DC, Barkley G, Salanova V, Olejniczak P, Cole A, Cash SS, Noe K, Wharen R, Worrell G, Murro AM, Edwards J, Duchowny M, Spencer D, Smith M, Geller E, Gwinn R, Skidmore C, Eisenschenk S, Berg M, Heck C, Van Ness P, Fountain N, Rutecki P, Massey A, O'Donovan C, Labar D, Duckrow RB, Hirsch LJ, Courtney T, Sun FT, Seale CG. Long-term treatment with responsive brain stimulation in adults with refractory partial seizures. Neurology. 2015;84:810–817. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jory C, Shankar R, Coker D, McLean B, Hanna J, Newman C. Safe and sound?A systematic literature review of seizure detection methods for personal use. Seizure. 2016;36:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Maguire MJ, Jackson CF, Marson AG, Nolan SJ. Treatments for the prevention of Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP)(Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011792.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Leijten FSS Dutch TeleEpilepsy Consortium. Multimodal seizure detection:A review. Epilepsia. 2018;59:42–47. doi: 10.1111/epi.14047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gutierrez EG, Crone NE, Kang JY, Carmenate YI, Krauss GL. Strategies for non-EEG seizure detection and timing for alerting and interventions with tonic-clonic seizures. Epilepsia. 2018;59:36–41. doi: 10.1111/epi.14046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhao X, Lhatoo SD. Seizure detection:do current devices work?And when can they be useful? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018;18:40. doi: 10.1007/s11910-018-0849-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Baumgartner C, Koren JP, Rothmayer M. Automatic computer-based detection of epileptic seizures. Front Neurol. 2018;9:639. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Beniczky S, Conradsen I, Henning O, Fabricius M, Wolf P. Automated real-time detection of tonic-clonic seizures using a wearable EMG device. Neurology. 2018;90:e428–e434. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Onorati F, Regalia G, Caborni C, Migliorini M, Bender D, Poh MZ, Frazier C, Kovitch Thropp E, Mynatt ED, Bidwell J, Mai R, LaFrance WC, Jr, Blum AS, Friedman D, Loddenkemper T, Mohammadpour-Touserkani F, Reinsberger C, Tognetti S, Picard RW. Multicenter clinical assessment of improved wearable multimodal convulsive seizure detectors. Epilepsia. 2017;58:1870–1879. doi: 10.1111/epi.13899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vandecasteele K, De Cooman T, Gu Y, Cleeren E, Claes K, Paesschen WV, Huffel SV, Hunyadi B. Automated epileptic seizure detection based on wearable ECG and PPG in a hospital environment. Sensors (Basel) 2017;17:E2338. doi: 10.3390/s17102338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rodriguez-Villegas E, Chen G, Radcliffe J, Duncan J. A pilot study of a wearable apnoea detection device. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005299. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hampel KG, Jahanbekam A, Elger CE, Surges R. Seizure-related modulation of systemic arterial blood pressure in focal epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2016;57:1709–1718. doi: 10.1111/epi.13504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hampel KG, Elger CE, Surges R. Impaired baroreflex sensitivity after bilateral convulsive seizures in patients with focal epilepsy. Front Neurol. 2017;8:210. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lockman J, Fisher RS, Olson DM. Detection of seizure-like movements using a wrist accelerometer. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;20:638–641. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Beniczky S, Polster T, Kjaer TW, Hjalgrim H. Detection of generalized tonic-clonic seizures by a wireless wrist accelerometer:A prospective, multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2013;54:e58–e61. doi: 10.1111/epi.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cuppens K, Karsmakers P, Van de Vel A, Bonroy B, Milosevic M, Luca S, Croonenborghs T, Ceulemans B, Lagae L, Van Huffel S, Vanrumste B. Accelerometry-based home monitoring for detection of nocturnal hypermotor seizures based on novelty detection. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2014;18:1026–1033. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2013.2285015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Arends JB, van Dorp J, van Hoek D, Kramer N, van Mierlo P, van der Vorst D, Tan FI. Diagnostic accuracy of audio-based seizure detection in patients with severe epilepsy and an intellectual disability. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;62:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Narechania AP, Garić II, Sen-Gupta I, Macken MP, Gerard EE, Schuele SU. Assessment of a quasi-piezoelectric mattress monitor as a detection system for generalized convulsions. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;28:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.van Poppel K, Fulton SP, McGregor A, Ellis M, Patters A, Wheless J. Prospective study of the emfit movement monitor. J Child Neurol. 2013;28:1434–1436. doi: 10.1177/0883073812471858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Fulton S, van Poppel K, McGregor A, Ellis M, Patters A, Wheless J. Prospective Study of 2 Bed Alarms for Detection of Nocturnal Seizures. J Child Neurol. 2013;28:1430–1433. doi: 10.1177/0883073812462064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Carlson C, Arnedo V, Cahill M, Devinsky O. Detecting nocturnal convulsions:efficacy of the MP5 monitor. Seizure. 2009;18:225–227. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ryvlin P, Nashef L, Tomson T. Prevention of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy:A realistic goal? Epilepsia. 2013;54:23–28. doi: 10.1111/epi.12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Watkins L, Shankar R, Sander JW. Identifying and mitigating sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) risk factors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18:265–274. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2018.1439738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kang JY, Rabiei AH, Myint L, Nei M. Equivocal significance of post-ictal generalized EEG suppression as a marker of SUDEP risk. Seizure. 2017;48:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Venit EL, Shepard BD, Seyfried TN. Oxygenation prevents sudden death in seizure-prone mice. Epilepsia. 2004;45:993–996. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.02304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Murabit A, Tredget EE. Review of burn ınjuries secondary to home oxygen. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:212–217. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182331dc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dupuis M, van Rijckevorsel K, Evrard F, Dubuisson N, Dupuis F, Van Robays P. Takotsubo syndrome (TKS):A possible mechanism of sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP) Seizure. 2012;21:51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Shapira B, Zohar J, Newman M, Drexler H, Belmaker RH. Potentiation of seizure length and clinical response to electroconvulsive therapy by caffeine pretreatment:A case report. Convuls Ther. 1985;1:58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Shorvon S, Tomson T. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Lancet. 2011;378:2028–2038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wirrell EC. Epilepsy-related Injuries. Epilepsia. 2006;47:79–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Schuele SU, Bermeo AC, Locatelli E, Burgess RC, Lüders HO. Ictal asystole:A benign condition? Epilepsia. 2008;49:168–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rugg-Gunn F, Duncan J, Hjalgrim H, Seyal M, Bateman L. From unwitnessed fatality to witnessed rescue:Nonpharmacologic interventions in sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2016;57:26–34. doi: 10.1111/epi.13231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Bartlam R, Mohanraj R. Ictal bradyarrhythmias and asystole requiring pacemaker implantation:Combined EEG-ECG analysis of 5 cases. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;64:212–215. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Catcheside PG, Mohtar AA, Reynolds KJ. Airflow resistance and CO2 rebreathing properties of anti-asphyxia pillows designed for epilepsy. Seizure. 2014;23:462–467. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Carleton JN, Donoghue AM, Porter WK. Mechanical model testing of rebreathing potential in infant bedding materials. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:323–328. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.4.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]