Abstract

Microtubules grow not only from the centrosome but also from various noncentrosomal microtubule-organizing centers (MTOCs), including the nuclear envelope (NE) and pre-existing microtubules. The evolutionarily conserved proteins Mto1/CDK5RAP2 and Alp14/TOG/XMAP215 have been shown to be involved in promoting microtubule nucleation. However, it has remained elusive as to how the microtubule nucleation promoting factors are specified to various noncentrosomal MTOCs, particularly the NE, and how these proteins coordinate to organize microtubule assembly. Here, we demonstrate that in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, efficient interphase microtubule growth from the NE requires Alp7/TACC, Alp14/TOG/XMAP215, and Mto1/CDK5RAP2. The absence of Alp7, Alp14, or Mto1 compromises microtubule regrowth on the NE in cells undergoing microtubule repolymerization. We further demonstrate that Alp7 and Mto1 interdependently localize to the NE in cells without microtubules and that Alp14 localizes to the NE in an Alp7 and Mto1-dependent manner. Tethering Mto1 to the NE in cells lacking Alp7 partially restores microtubule number and the efficiency of microtubule generation from the NE. Hence, our study delineates that Alp7, Alp14, and Mto1 work in concert to regulate interphase microtubule regrowth on the NE.

Keywords: microtubule, microtubule nucleation, nuclear envelope, microtubule-associated protein, fission yeast

Introduction

Many fundamental cellular activities, including vesicle/organelle trafficking, cell migration, establishment of cell polarity, and cell division, involve the microtubule cytoskeleton (Sawin and Snaith, 2004; Bao et al., 2018a; Wei et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2019). Microtubule organization varies in a cell-type and cell-cycle-dependent manner, and is generally dictated by the sites of microtubule growth (Petry and Vale, 2015; Muroyama and Lechler, 2017; Sanchez and Feldman, 2017; Wu and Akhmanova, 2017). Such microtubule initiating sites are referred to as the microtubule organizing center (MTOC) (Sawin and Tran, 2006; Wu and Akhmanova, 2017). The centrosome and its equivalents in lower eukaryotic cells (i.e. the spindle pole body, SPB) are conventionally thought of as the main MTOC. However, noncentrosomal/non-SPB MTOCs have been increasingly recognized as key players in microtubule organization (Muroyama and Lechler, 2017; Sanchez and Feldman, 2017).

In epithelial cells, MTOCs locate at the apical cortex and generate microtubules running parallel toward the basal cortex (Muroyama and Lechler, 2017; Sanchez and Feldman, 2017). Similarly, in plant cells, MTOCs are present at the cell cortex and on pre-existing microtubules to form complex cortical microtubule arrays (Sanchez and Feldman, 2017). Moreover, MTOCs are present at the Golgi apparatus, assembling microtubules to organize the organelle (Muroyama and Lechler, 2017; Sanchez and Feldman, 2017; Zheng et al., 2019). In muscle cells, the nuclear envelope (NE) is the main location for generating microtubules (Muroyama and Lechler, 2017; Sanchez and Feldman, 2017). This is similar in fission yeast, in which the NE appears to be the main site for interphase microtubule regrowth in cells recovering from cold shock or treatment with the microtubule depolymerizing drug Methyl benzimidazol-2-yl-carbamate (MBC) (Tran et al., 2001; Anders et al., 2006). It has been reported that centrosomal proteins including γ-tubulin undergo redistribution from the centrosome to the NE during the differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes and that Akap450 and its associated protein Nesprin-1a are responsible for tethering microtubule minus ends to the NE in muscle cells (Bugnard et al., 2005; Gimpel et al., 2017; Muroyama and Lechler, 2017). How NE-dependent microtubules are generated in general remains elusive.

The fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe is an excellent model organism for the study of microtubules because of the simple organization of microtubule arrays (Hagan, 1998). Generally, 3–6 microtubule bundles are aligned along the long axis of the interphase cell with the microtubule plus ends pointing toward cell tips and the minus ends apposed to the NE. Microtubules in fission yeast grow from the SPB, multiple MTOCs on pre-existing microtubules, and the NE during interphase while from the SPB and eMTOC (equatorial MTOC localizing around the actomyosin ring) during mitosis (Hagan, 1998; Sawin and Tran, 2006). It has been noted that interphase microtubules mainly regrow from the NE in fission yeast cells recovering from cold shock or MBC treatment, suggestive of an important role of the NE in microtubule nucleation (Tran et al., 2001; Anders et al., 2006). This feature makes fission yeast a convenient model organism to dissect molecular mechanisms underlying NE-dependent microtubule generation.

The transforming acidic coiled-coil protein (TACC) Alp7 likely contributes to NE-dependent microtubule generation. First, the absence of Alp7 causes detachment of microtubule bundles from the NE (Zheng et al., 2006). Second, the absence of Alp7 impairs the NE localization of Alp4, a component of the γ-tubulin ring complex (γ-TuRC), and Mto1, a factor required for activating non-SPB microtubule nucleation (Sawin et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2006; Samejima et al., 2008; Samejima et al., 2010; Lynch et al., 2014). Third, Alp7 functions in complex with the TOG (Tumor overexpressed gene) domain-containing protein Alp14 to regulate microtubule dynamics (Sato et al., 2004). Alp14 has been shown to function not only as a microtubule polymerase but also as a key factor in promoting microtubule nucleation (Al-Bassam et al., 2012; Flor-Parra et al., 2018). How Alp7 coordinates with Alp14 and Mto1 to promote NE-dependent microtubule generation is still unclear.

We employed profusion chambers to examine interphase microtubule regrowth in cells after MBC washout by live-cell microscopy, and showed that efficient interphase microtubule regrowth from the NE requires Alp7, Alp14, and Mto1. We further showed that Alp7 and Mto1 interdependently localize to the NE and that Alp14 localizes to the NE in an Alp7 and Mto1-dependent manner. Thus, this present work demonstrates a synergism of Alp7, Alp14, and Mto1 in promoting NE-dependent microtubule assembly.

Results

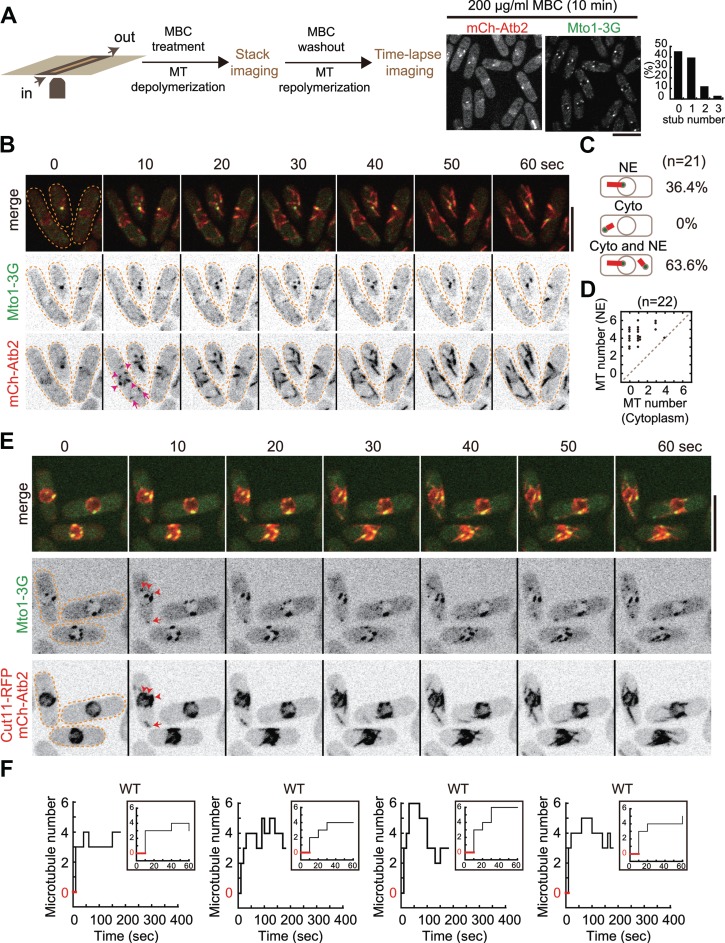

Microtubules regrow mainly from the NE after MBC washout

Cold treatment and MBC washout assays have been regularly used to study microtubule nucleation (Tran et al., 2001; Sawin et al., 2004; Sawin and Snaith, 2004; Zimmerman et al., 2004; Janson et al., 2005; Anders et al., 2006). Both assays show rapid microtubule regrowth from the NE in fission yeast. To understand how microtubule regrowth from the NE is regulated mechanistically, we revisited microtubule assembly dynamics by live-cell microscopy with profusion chambers, in which cells were treated with MBC followed by washout (Figure 1A). Pilot experiments on wild-type (WT) cells expressing Mto1-3GFP (a key factor promoting non-SPB microtubule nucleation) and mCherry-Atb2 (α-tubulin) showed that treating cells with 25 or 50 μg/ml MBC for ~10 min, a condition used in many previous studies (Tran et al., 2001; Sawin and Snaith, 2004; Janson et al., 2005), was not able to depolymerize microtubules completely and left multiple microtubule stubs on the NE. This resistance to microtubule depolymerization was likely contributed by the robust microtubule overlapping structures and/or the SPB (Loiodice et al., 2005). To examine de novo microtubule growth, we sought to depolymerize microtubule completely and thus treated cells with 200 μg/ml MBC for ~10 min. Such attempt was successful with most of the cells displaying no microtubule or 1 microtubule remnant/stub on the NE, presumably at the SPB (Figure 1A). The MBC-treated cells could recover after washout of the drug as no apparent defects of cell growth and mitosis progression were found (Supplementary Figure S1B and C). We then followed the condition to perform all the experiments described below.

Figure 1.

Microtubule regrowth after MBC washout. (A) Diagram illustrating the experimental procedure. Cells attached to the poly-L-lysine-coated coverslip in a profusion chamber were treated with 200 μg/ml MBC to depolymerize microtubules, and stack images were then acquired to assess microtubule depolymerization. Time-lapse imaging was performed upon MBC washout to monitor microtubule regrowth. On the right are maximum projection images of WT cells expressing Mto1-3GFP (a protein required for non-SPB microtubule nucleation) and mCherry-Atb2 (α-tubulin) and quantification of microtubule stubs left after MBC treatment. Note that ~45% and ~39% of the cells (n = 28) had 0 and 1 microtubule stub on the NE, respectively. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Maximum projection time-lapse images of WT cells expressing Mto1-3GFP and mCherry-Atb2. Upon MBC washout, microtubules regrew rapidly from the NE (within 10 sec). Arrowheads and arrows mark newly generated microtubules on the NE and in the cytoplasm, respectively. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of microtubule regrowth patterns as indicated. NE, regrowth from the NE; Cyto, regrowth from the cytoplasm; Cyto and NE, regrowth both from the cytoplasm and from the NE. n indicates cell number. (D) Quantification of microtubule number on the NE and in the cytoplasm for each cell within 2 min after MBC washout. n indicates cell number. (E) Maximum projection time-lapse images of WT cells expressing Mto1-3GFP, Cut11-RFP (a protein localizing to the NE), and mCherry-Atb2. Red arrowheads mark newly generated microtubules on the NE while the red arrow indicates a newly generated microtubule in the cytoplasm. (F) Representative step plots of microtubule number against time after MBC washout for WT cells (also see Supplementary Figure S1 for all plots). Note that cells with microtubules growing only from the NE were used for analysis and that at the second time point (i.e. after 10 sec upon MBC washout) microtubules appeared (see inset graphs; red lines indicate the period of time during which cells did not display microtubules).

Microtubules regrew rapidly in random directions upon MBC washout (Figure 1B). To follow these rapidly growing microtubules, we acquired stack images, consisting of three planes with 0.5 μm spacing, every 10 sec. As shown in Figure 1B, microtubules grew from the Mto1 foci mainly on the NE and sometimes from the cytoplasm. Indeed, quantification confirmed that 36.4% (n = 21) of the cells grew microtubules only from the NE, 0% only from the cytoplasm, and 63.6% both from the NE and from the cytoplasm (Figure 1C). We further quantified, in each cell (n = 22), the location of microtubule regrowth, and as shown in the scattering dot plot (Figure 1D), microtubules grew mainly from the NE. To ascertain that newly generated microtubules were from the NE, we examined microtubule regrowth with a strain expressing Mto1-3GFP, mCherry-Atb2, and Cut11-RFP (a transmembrane protein marking the NE; West et al., 1998). As shown in Figure 1E, upon MBC washout, microtubules clearly regrew from Mto1-3GFP foci on the NE. Such microtubule regrowth events were very rapid as ≥2 microtubules were clearly visible at the second time point of the imaging (i.e. within 10 sec; Figure 1F; also see Supplementary Figure S1A). Hence, we concluded that the NE is the predominant location for microtubule regrowth upon MBC washout.

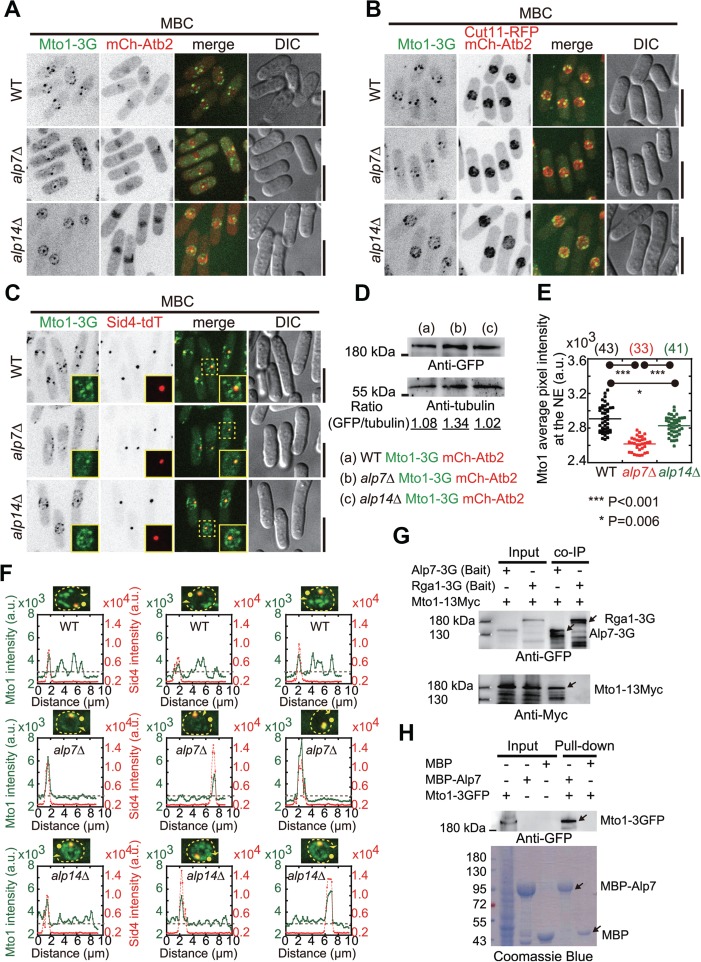

Alp7, but not Alp14, is required for the localization of Mto1 to the NE

Alp7 and Alp14 are involved in promoting microtubule nucleation (Flor-Parra et al., 2018). We then assessed if the absence of either Alp7 or Alp14 affects the localization of Mto1, the factor activating microtubule nucleation (Lynch et al., 2014), with stack images consisting of 11 planes spaced by 0.5 μm (Figure 2A). In WT cells, microtubule depolymerization led to enrichment of Mto1 on the NE, forming multiple large Mto1 foci. In alp7Δ cells, only one resolvable large Mto1 focus appeared on the NE and such focus colocalized with Sid4-tdTomato (SPB marker) at the SPB (Figure 2C). In addition, multiple amorphous structures were present in the cytoplasm in alp7Δ cells. Intriguingly, in alp14Δ cells, the localization of Mto1 to the NE appeared not to be impaired except that the distribution of Mto1 on the NE became more diffusive. These observations were further confirmed by imaging WT, alp7Δ, and alp14Δ cells expressing Mto1-3GFP, mCherry-Atb2, and Cut11-RFP or expressing Mto1-3GFP and Sid4-tdTomato (Figure 2B and C). Western blotting analysis of protein expression showed that Mto1-3GFP expressed comparably in WT, alp7Δ, and alp14Δ cells except that the Mto1-3GFP levels in alp7Δ cells were slightly higher (Figure 2D). Nevertheless, such elevated expression did not enhance the localization of Mto1-3GFP to the NE in alp7Δ cells. Instead, much less Mto1-3GFP signals were detected on the NE in MBC-treated alp7Δ cells (Figure 2A–C). To compare the amount of Mto1 on the NE in a quantitative manner, we measured the average pixel intensity of Mto1 signals on the NE (i.e. integrated fluorescent intensity over area of the NE). As shown in Figure 2E, the absence of Alp7 significantly decreased the average fluorescent intensity of Mto1-3GFP on the NE and the absence of Alp14 only slightly decreased the average fluorescent intensity of Mto1-3GFP on the NE, suggesting that Mto1 mainly depends on Alp7, but not Alp14, for localizing to the NE (Figure 2E). Consistent with the quantification, line-scan intensity measurements of Mto1-3GFP around the NE confirmed that Alp7 plays a major role in localizing Mto1-3GFP to the NE in MBC-treated cells as very few Mto1-3GFP signals were detected around the NE except at the SPB in alp7Δ cells (Figure 2F). Mto1 was likely recruited by Alp7 to the NE because co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments showed that Alp7-3GFP was able to precipitate with Mto1-13Myc (Figure 2G) and pull-down experiments confirmed that the interaction between MBP-Alp7 and Mto1-3GFP was positive (Figure 2H). Together, these results suggested that Alp7, but not Alp14, is required for the redistribution of Mto1 to the NE upon microtubule depolymerization by drug treatment.

Figure 2.

Localization of Mto1 to the NE in MBC-treated alp7Δ and alp14Δ cells. (A) Maximum projection images of WT, alp7-deletion (alp7Δ), and alp14Δ cells expressing Mto1-3GFP and mCherry-Atb2. Cells were treated with 200 μg/ml MBC for 10 min to depolymerize microtubules. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Maximum projection images of WT, alp7Δ, and alp14Δ cells expressing Mto1-3GFP, Cut11-RFP, and mCherry-Atb2. Cells were treated with 200 μg/ml MBC for 10 min to depolymerize microtubules. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Maximum projection images of WT, alp7Δ, and alp14Δ cells expressing Mto1-3GFP, Sid4-tdTomato (a protein marking the SPD). Cells were treated with 200 μg/ml MBC for 10 min to depolymerize microtubules. The highlighted regions by dashed squares are shown as inset images. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Western blotting analysis of the expression of Mto1-3GFP in WT, alp7Δ, and alp14Δ cells with antibodies against GFP and tubulin. Intensity of the bands was measured and the ratio of GFP intensity over tubulin is indicated. (E) Quantification of the average pixel intensity of Mto1-3GFP on the NE for the cells indicated in C. Mto1-3GFP signals from the SPB were excluded. P-values were calculated by student’s t-test, and cell number is indicated. Note that Mto1 average intensity on the NE significantly decreases in alp7Δ cells, but slightly in alp14Δ cells. (F) Line-scan intensity analysis of Mto1-3GFP and Sid4-tdTomato distribution around the NEs (marked by the dash yellow lines with filled circles and arrowheads indicating the start and stop positions, respectively). Dashed gray lines in the graphs correspond to the Mto1-3GFP intensity value of 3 × 103. (G) Co-IP assays. Cell lysates were prepared with cells expressing Mto1-13Myc and either Alp7-3GFP or Rga1-3GFP. Dynabeads magnetic beads bound with an anti-GFP antibody were used, and anti-GFP and anti-Myc antibodies were used for the western blotting analysis. (H) Pull-down assays. Recombinant proteins MBP-Alp7 and MBP were incubated with the cell lysate containing Mto1-3GFP. Pull-down products were analyzed by western blotting with an antibody against GFP and by SDS-PAGE coomassie blue staining.

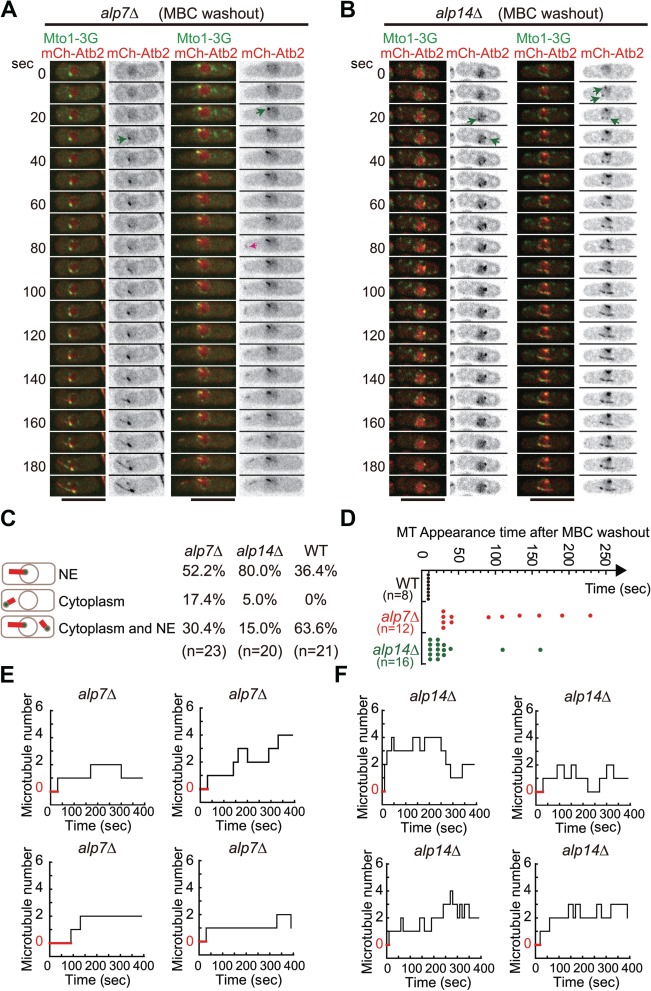

Alp7, but not Alp14, is required for microtubule regrowth from the NE in cells recovering from MBC treatment

Next, we performed MBC washout assays to examine microtubule regrowth in alp7Δ and alp14Δ cells. As shown in Figure 3A and B, microtubules were able to regrow from the NE and the cytoplasm in both types of cells after MBC washout. Despite the capability of generating new microtubules, alp14Δ cells had microtubules growing mainly from the NE, but the microtubules appeared to be defective in elongation (Figure 3B), which is consistent with the role of Alp14 as a microtubule polymerase (Al-Bassam et al., 2012). In contrast, in alp7Δ cells, microtubules appeared to elongate normally but more alp7Δ cells displayed microtubules growing from the cytoplasm. Quantification of the location of microtubule growth confirmed that 17.4% of alp7Δ cells grew microtubules only from the cytoplasm, compared with 5.6% of alp14Δ cells and 0% of WT (Figure 3C). These results suggested that Alp7 is indeed required for microtubules to grow from the NE.

Figure 3.

Microtubule regrowth in alp7Δ and alp14Δ cells after MBC washout. (A) Maximum projection time-lapse images of alp7Δ cells expressing Mto1-3GFP and mCherry-Atb2. Cells were treated with MBC to depolymerize microtubules and images were acquired every 10 sec upon MBC washout. The pink arrow marks a newly generated microtubule in the cytoplasm while the green arrows indicate the microtubules growing from the NE. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Maximum projection time-lapse images of alp14Δ cells expressing Mto1-3GFP and mCherry-Atb2. Cells were treated with MBC to depolymerize microtubules and images were acquired every 10 sec upon MBC washout. Microtubules grew from the NE (marked by green arrows). Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of microtubule regrowth patterns as indicated. NE, regrowth only from the NE; Cytoplasm, regrowth only from the cytoplasm; Cytoplasm and NE, regrowth both from the cytoplasm and from the NE. n indicates cell number. The quantification data for WT cells is the one in Figure 1C. Note that the percentage of cells with microtubules growing only from the cytoplasm and only from the NE increased significantly in alp7Δ and alp14Δ cells, respectively. (D) Quantification of the appearance time of the first microtubule in WT, alp7Δ, and alp14Δ cells upon MBC washout. n indicates cell number. Note that cells with microtubules growing only from the NE were used for analysis. (E and F) Representative step plots of microtubule number against time after MBC washout for alp7Δ (E) and alp14Δ (F) cells (also see Supplementary Figures S2 and S3 for all plots). Note that cells with microtubules growing only from the NE were used for analysis and that red lines indicate the period of time during which cells did not display microtubules.

Despite the differential roles in regulating microtubule regrowth after MBC washout, both Alp7 and Alp14 appeared to be required for efficient microtubule regrowth as the absence of either Alp7 or Alp14 caused a delay in generating the first visible microtubule on the NE (Figure 3D–F). We then monitored the number of microtubules on the NE in alp7Δ and alp14Δ cells by live-cell microscopy for 400 sec after MBC washout (Figure 3E and F). As shown in the step plots (Figure 3E; also see Supplementary Figure S2), the number of microtubules on the NE in most of the alp7Δ cells increased slowly over time but rarely exceeded 2. Interestingly, the number of microtubules on the NE in alp14Δ cells increased over time but fluctuated significantly during the observation period, indicative of instability of the newly generated microtubules (Figure 3F; also see Supplementary Figure S3). Nonetheless, more microtubules regrew from the NE in alp14Δ cells than alp7Δ cells. This correlates well with the finding that the absence of Alp7, but not Alp14, impaired the localization of Mto1 to the NE (Figure 2A). Taken together, we concluded that microtubule regrowth from the NE upon MBC washout mainly depends on Alp7, but not Alp14.

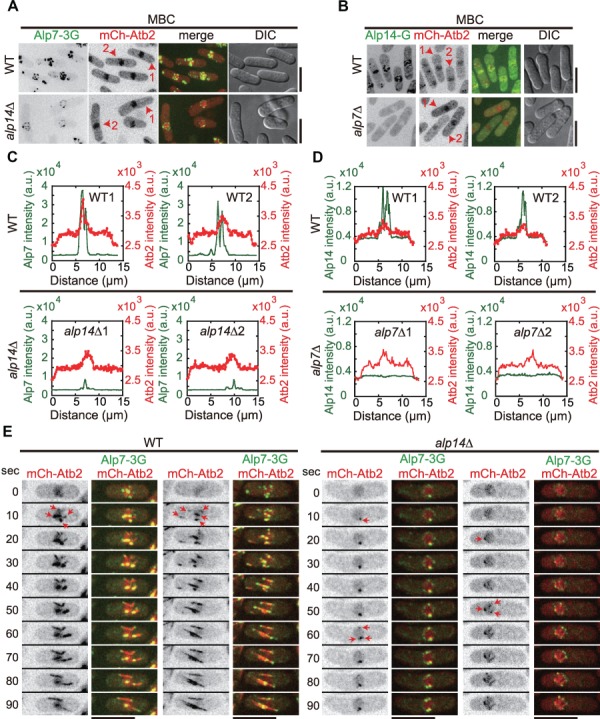

Alp7 is required for the localization of Alp14 to the NE, but not vice versa

We then examined how microtubule depolymerization alters the localization of Alp7 and Alp14. Similar to Mto1, MBC treatment caused a great enrichment of both Alp7-3GFP and Alp14-GFP on the NE (Figure 4A and B). Interestingly, after MBC treatment, Alp7 remained at the NE in alp14Δ cells whereas Alp14 did not decorate the NE anymore in alp7Δ cells (Figure 4A and B). In addition, line-scan fluorescent intensity analysis of the signals of mCherry-Atb2 and either Alp7-3GFP or Alp14-GFP along the long axis of cells further showed that Alp7 signals on the NE were reduced in the absence of Alp14 and that Alp14 localization on the NE was abolished in alp7Δ cells (Figure 4C and D). These data suggested that Alp7 dictates the localization of Alp14 to the NE but Alp14 plays a minor role in determining the localization of Alp7 to the NE. The Alp7 foci on the NE appeared to be the main sites responsible for microtubule regrowth as microtubules generally grew from the Alp7 foci regardless of the presence of Alp14 (Figure 4E). Hence, Alp14 requires Alp7 for localizing to the NE but not vice versa.

Figure 4.

Localization of Alp14 to the NE depends on Alp7, but not vice versa. (A) Maximum projection images of WT and alp14Δ cells expressing Alp7-3GFP and mCherry-Atb2. Cells were treated with 200 μg/ml MBC for 10 min to depolymerize microtubules. The cells used for line-scan intensity analysis in C were marked as `1’ and `2’. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Maximum projection images of WT and alp7Δ cells expressing Alp14-GFP and mCherry-Atb2. Cells were treated with 200 μg/ml MBC for 10 min to depolymerize microtubules. The cells used for line-scan intensity analysis in D were marked as `1’ and `2’. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Line-scan intensity analysis of Alp7-3GFP and mCherry-Atb2 along the long axis of WT and alp14Δ cells indicated in A. The peak regions correspond to the nuclei. (D) Line-scan intensity analysis of Alp14-GFP and mCherry-Atb2 along the long axis of WT and alp7Δ cells indicated in B. The peak regions correspond to the nuclei. (E) Maximum projection time-lapse images of WT and alp14Δ cells expressing Alp7-3GFP and mCherry-Atb2. Cells were treated with 200 μg/ml MBC for 10 min to depolymerize microtubules. Red arrows mark newly generated microtubules after MBC washout. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Tethering Mto1 to the NE enhances microtubule regrowth in alp7Δ cells

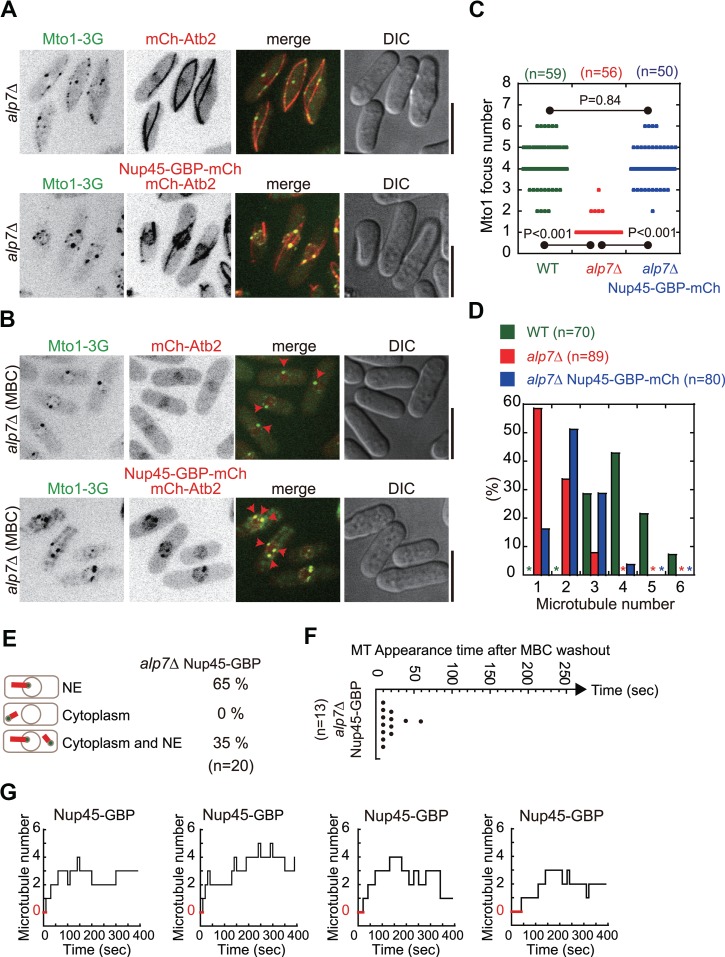

Alp7 is required for the localization of both Mto1 and Alp14 to the NE (Figures 2 and 4) and for microtubule regrowth from the NE (Figure 3C–E). In addition, it has been shown that Mto1 is an essential factor in activating non-SPB microtubule nucleation (Lynch et al., 2014). Therefore, we reasoned that restoring the localization of Mto1 to the NE in alp7Δ cells could rescue the defective microtubule phenotype. We employed the GBP (GFP binding protein)-GFP targeting system (Rothbauer et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2017). As shown in Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure S4A, expression of Nup45-GBP-mCherry (a component of the nuclear pore complex) enhanced the localization of Mto1-3GFP to the NE in alp7Δ cells. The enhancement was more apparent after MBC treatment (Figure 5B and Supplementary Figure S4B), which was confirmed by quantification of Mto1 foci on the NE (Figure 5C). The restored localization of Mto1 enhanced microtubule regrowth from the NE (Figure 5E) and microtubule regrowth became more efficient (Figure 5F and G, compared with the data in Figure 3C–F; also see Supplementary Figure S5). As a result, microtubule number increased significantly in the cells expressing Nup45-GBP-mCherry (Figure 5D). These results suggest that proper localization of Mto1 to the NE is a key factor in regulating microtubule organization.

Figure 5.

Tethering Mto1-3GFP to the NE by Nup45-GBP-mCherry in alp7Δ cells promotes microtubule growth from the NE. (A) Maximum projection images of WT and alp7Δ cells expressing Mto1-3GFP and either mCherry-Atb2 or mCherry-Atb2 plus Nup45-GBP-mCherry (alp7Δ Nup45-GBP-mCherry cells). Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Maximum projection images of the indicated cells in A treated with MBC. Red arrowheads mark Mto1-3GFP foci on the NE. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of Mto1-3GFP foci on the NE in WT, alp7Δ, and alp7Δ Nup45-GBP-mCherry cells. The P-values were calculated by student’s t-test and n indicates cell number. (D) Quantification of microtubule number in WT, alp7Δ, and alp7Δ Nup45-GBP-mCherry cells. n indicates cell number. Note that tethering Mto1-3GFP to the NE by Nup45-GBP-mCherry in alp7Δ cells partially restores microtubule number. (E) Quantification of microtubule regrowth patterns as indicated for alp7Δ Nup45-GBP-mCherry cells (for comparison, also see Figure 3C). NE, regrowth only from the NE; Cytoplasm, regrowth only from the cytoplasm; Cytoplasm and NE, regrowth both from the cytoplasm and from the NE. n indicates cell number. (F) Quantification of the appearance time of the first microtubule in alp7Δ Nup45-GBP-mCherry cells upon MBC washout (for comparison, also see Figure 3D). n indicates cell number. Note that cells with microtubules growing only from the NE were used for analysis. (G) Step plot of microtubule number against time after MBC washout for alp7Δ Nup45-GBP-mCherry cells (for comparison, see Figure 3E; also see Supplementary Figure S5 for all plots). Note that cells with microtubules growing only from the NE were used for analysis and that red lines indicate the period of time during which cells did not display microtubules.

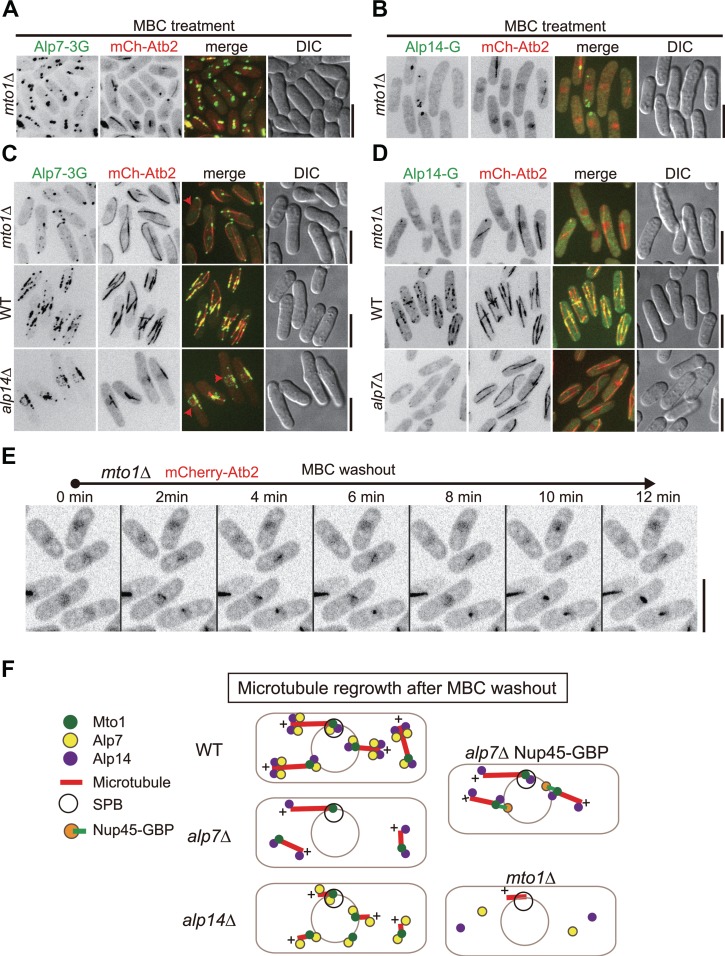

The localization of Alp7 and Alp14 to the NE depends on Mto1

We further tested if Mto1 is required for the localization of Alp7 and Alp14 to the NE in MBC-treated cells. As shown in Figure 6A and B, the localization of Alp7 and Alp14 to the NE were abolished in MBC-treated mto1Δ cells. Such effect was also apparent in mto1Δ cells without MBC treatment (Figure 6C and D). It is most likely that in MBC-treated cells, Mto1 and Alp7 localize to the NE interdependently and that Alp14 depends both on Mto1 and on Alp7 for localizing to the NE. As a result, the absence of Alp7 and Alp14 on the NE in mto1Δ cells abolished microtubule regrowth from the NE because most of the mto1Δ cells failed to regrow microtubules or regrew only one very short microtubule from the NE (presumably from the SPB) after MBC washout (Figure 6E). The microtubule regrowth from the SPB in mto1Δ cells could be due to the presence of Alp4, a component of the γ-tubulin small complex responsible for microtubule nucleation, at the SPB as the localization of Alp4 to the SPB has been shown to be independent of Mto1 (Sawin et al., 2004; Zimmerman and Chang, 2005).

Figure 6.

Localization of Alp7 and Alp14 to the NE after MBC treatment is abolished in mto1Δ cells. (A and B) Maximum projection images of mto1Δ cells expressing mCherry-Atb2 and either Alp7-3GFP (A) or Alp14-GFP (B). Cells were treated with 200 μg/ml MBC for 10 min to depolymerize microtubules. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C and D) Maximum projection images of unperturbed mto1Δ, WT, and either alp14Δ (C) or alp7Δ (D) cells expressing mCherry-Atb2 and either Alp7-3GFP (C) or Alp14-GFP (D). Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Maximum projection time-lapse images of mto1Δ cells expressing mCherry-Atb2. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Diagram illustrating the proteins regulating microtubule regrowth after MBC washout. In WT cells, Alp7, Alp14, and Mto1 are present, presumably as a complex, on the NE to promote initial microtubule growth; the presence of the Alp7-Alp14 at microtubule plus ends further promotes efficient microtubule elongation. Such Alp7, Alp14, and Mto1 complex also function to promote microtubule regrowth in the cytoplasm. The absence of Alp7 (alp7Δ) impairs the localization of Mto1 and Alp14 to the NE, compromising microtubule growth from the NE but not in the cytoplasm. The absence of Alp14 (alp14Δ) affects, but does not abolish, the localization of Alp7 and Mto1 to the NE. As a result, microtubules are still able to regrow from the NE after MBC washout but display a defect in microtubule elongation due to the lacking of the microtubule polymerase Alp14. The absence of Mto1 (mto1Δ) abolishes the localization of both Alp7 and Alp14 to the NE, leading to no microtubule regrowth from the NE after MBC washout.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that Alp7 and Alp14 synergize to promote microtubule regrowth from the NE in cells recovering from MBC treatment. Alp7 and Mto1 likely work in concert to initiate microtubule regrowth from the NE while Alp14 functions to promote further elongation of the NE-associated microtubules (Figure 6F). We further demonstrate that Alp7 and Mto1 interdependently localize to the NE (Figures 2A–C, 6A and C) and that Alp14 depends both on Alp7 and on Mto1 for localizing to the NE (Figures 4B and D, 6B and D).

Our results underscored the critical role of Alp7 in assembling microtubules on the NE, and Alp7 may do so by accumulating Mto1 and Alp14 to the NE where Mto1 functions to activate microtubule nucleation and Alp14 promotes microtubule elongation. This is supported by our findings that the absence of Alp7 abolishes the NE localization of Alp14 while significantly impairs the NE localization of Mto1 (Figures 2A–C and E, 4B and D), which is consistent with the previous publications (Zheng et al., 2006; Flor-Parra et al., 2018). We further noted that particularly in alp7Δ cells, Mto1 emerged in the cytoplasm and displayed as many amorphous structures (Figure 2). This redistribution of Mto1 to the cytoplasm in alp7Δ cells is likely the cause of the increased percentage of microtubule regrowth from the cytoplasm (Figure 3A and C). Recently, it was reported that the exportin Crm1 recruits Mto1 to the nuclear pore complex on the NE to promote NE-associated microtubule growth (Bao et al., 2018b). In addition, this work showed that Alp7 is not required for the NE localization of Mto1(9A1-NE), an Mto1 mutant localizing specifically to the NE and lacking the C-terminus of Mto1 (amino acids 550–1115; additional nine amino acids in the CM1 domain are mutated to Alanine). This does not necessarily contradict our conclusion because we examined endogenous NE-associated Mto1 whereas the indicated study examined the truncated Mto1 mutant, Mto1(9A1-NE), that specifically localizes to the NE. Rather, the two studies together suggest a possibility that Crm1 and Alp7 may interact with different regions of Mto1 and both interactions are required for localizing Mto1 to the NE. Indeed, our co-IP assay showed that Alp7-3GFP precipitates with Mto1-13Myc (Figure 2G).

This present work showed that Mto1 is also required for localizing Alp7 to the NE (Figure 6A). Therefore, it is conceivable that Alp7 and Mto1 form a complex to allow for efficient localization of the complex to the NE. Such Alp7-Mto1 complex on the NE should possess a very strong activity in microtubule nucleation because Mto1 has been shown to be required for de novo non-SPB microtubule assembly and Alp7 has been shown to recruit Alp14 to nucleation sites for promoting microtubule assembly (Sawin et al., 2004; Samejima et al., 2010; Lynch et al., 2014; Flor-Parra et al., 2018).

Interestingly, despite the important role of Alp14 in promoting microtubule nucleation (Flor-Parra et al., 2018), alp14Δ cells are still able to grow very short microtubules from the NE, indicative of defective microtubule elongation (Figures 3B and 4E). This finding suggests that Alp14 may not be required for de novo microtubule regrowth from the NE, at least in cells recovering from MBC treatment, but instead support the claim that Alp14 is a microtubule polymerase (Al-Bassam et al., 2012). The ability in generating microtubules from the NE in alp14Δ cells may be due to the presence of Alp7 and Mto1 on the NE (Figures 2A–C and 4A). Nevertheless, this does not exclude the possibility that Alp14 plays a critical role in microtubule nucleation since the appearance of the first microtubule on the NE in alp7Δ and alp14Δ cells recovering from MBC treatment is significantly delayed (Figure 3D).

In unperturbed cells, it is generally difficult to detect NE-associated microtubule growth. Alp7 and Alp14 mainly localize along pre-existing microtubules as foci (Figure 6C and D), and the same is true for Mto1 as reported previously (Sawin et al., 2004; Shen et al., 2018). Such localization preference may enable microtubules to be generated mainly on pre-existing microtubules in unperturbed cells. It is conceivable that microtubule generation from the NE may serve as a backup fast-acting mechanism to restore microtubule arrays in response to unfavorable environmental conditions such as cold treatment.

In conclusion, microtubule generation from the NE requires concerted efforts of the evolutionarily conserved proteins Alp7/TACC, Alp14/TOG/XMAP215, and Mto1/CDK5RAP2. Given the conservative nature of the involved proteins, the proposed working model may be conserved through evolution. This awaits further investigation.

Materials and methods

Plasmids and yeast strains

Plasmids were constructed by homologous recombination method using ClonExpress II One Step Cloning kits (www.vazyme.com), and yeast strains were created either by random spore digestion or tetra-dissection analysis (Forsburg and Rhind, 2006). Gene deletion and tagging were achieved using the PCR-based homologous recombination method (Bahler et al., 1998). The plasmids and strains used in this study are included in the Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

Biochemistry

Yeast cells at the exponential phase, cultured in 1 L YE5S (YE medium supplemented with the five supplements: Adenine, Uracil, Leucine, Histidine, and Lysine, 0.225 g/L each), were harvested for the co-IP assay. Cell lysates were prepared by liquid nitrogen grinding with the mortar grinder RM 200 (www.retsch.com), and were then suspended in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) plus 0.1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail (www.biovision.com) at 4°C for 0.5 h. Supernatants were collected after centrifugation at 12 000 rpm for 20 min and incubated with Dynabeads Protein G beads (www.thermofisher.com) coupled with an anti-GFP antibody (www.rockland-inc.com) at 4°C for 2 h. After incubation, Dynabeads were washed with the buffer TBS + 0.1% Triton X-100 for three times and then with the TBS buffer for one time. Finally, co-IP samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting with antibodies against GFP and Myc (www.rockland-inc.com). For pull-down assays, recombinant proteins MBP-Alp7 and MBP were expressed in E.coli and were purified with amylose resins (www.neb.com). The purified recombinant proteins on the resins were then incubated with cell lysates (prepared as indicated above) containing Mto1-3GFP in TBS plus 0.1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail for 1 h. After the incubation, the resins were washed with buffer TBS+ 0.1% Triton X-100 for five times and TBS buffer for one time. SDS-PAGE and western blotting were then performed to analyze the pull-down protein samples with an antibody against GFP. For testing protein expression, cells were broken using glass beads and cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting with antibodies against GFP and tubulin (www.enogene.com).

Profusion chamber experiments

Profusion chambers were prepared with double-sticky tape and poly-L-lysine (5 mg/ml) coated coverslips, as described previously (Tran et al., 2001). Cells were flowed into an upside-down chamber, followed by 10 min incubation at room temperature to allow attachment of cells to coverslips. Medium replacement was performed by adding medium from one side and absorbing from the other with tissue papers. EMM Medium containing the five supplements and 200 μg/ml MBC was used to depolymerize microtubules. To allow microtubule regrowth, MBC-free EMM medium was used.

Microscopy and data analysis

A PerkinElmer UltraVIEW Vox spinning-disk microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C9100-23B EMCCD camera and a CFI Apochromat TIRF 100× objective (NA = 1.49) was used for all microscopy experiments. Briefly, cells at the exponential phase were collected and imaged on EMM (with the five supplements) agarose pad slides, as described previously (Tran et al., 2004). For maximum projection imaging, stack images containing 11 planes spaced by 0.5 μm were acquired; for time-lapse imaging, stack images containing three planes spaced by 0.5 μm were acquired every 10 sec. MetaMorph 7.7 (www.moleculardevices.com) and Image J 1.5 (imagej.nih.gov) softwares were used to analyze the imaging data. Plot and step graphs were created using KaleidaGraph 4.5 (www.synergy.com), and statistical analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Quanwen Jin (Xiamen University), Phong Tran (UPENN), Fred Chang (UCSF), and Snezhana Oliferenko (KCL) and the Yeast Genetic Resource Center Japan for providing yeast strains and plasmids.

Funding

This work is supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0503600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91754106, 31871350, 31671406, 31601095, and 31621002), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB19040101), the Major/Innovative Program of Development Foundation of Hefei Center for Physical Science and Technology (2017FXCX008), and China’s 1000 Young Talents Recruitment Program.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- Al-Bassam J., Kim H., Flor-Parra I., et al. (2012). Fission yeast Alp14 is a dose-dependent plus end-tracking microtubule polymerase. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 2878–2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders A., Lourenco P.C., and Sawin K.E. (2006). Noncore components of the fission yeast γ-tubulin complex. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 5075–5093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler J., Wu J.Q., Longtine M.S., et al. (1998). Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14, 943–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X., Liu H., Liu X., et al. (2018a). Mitosis-specific acetylation tunes Ran effector binding for chromosome segregation. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 18–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X.X., Spanos C., Kojidani T., et al. (2018b). Exportin Crm1 is repurposed as a docking protein to generate microtubule organizing centers at the nuclear pore. eLife 7, pii: e33465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugnard E., Zaal K.J., and Ralston E. (2005). Reorganization of microtubule nucleation during muscle differentiation. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 60, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.H., Wang G.Y., Hao H.C., et al. (2017). Facile manipulation of protein localization in fission yeast through binding of GFP-binding protein to GFP. J. Cell Sci. 130, 1003–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor-Parra I., Iglesias-Romero A.B., and Chang F. (2018). The XMAP215 Ortholog Alp14 promotes microtubule nucleation in fission yeast. Curr. Biol. 28, 1681–1691.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsburg S.L., and Rhind N. (2006). Basic methods for fission yeast. Yeast 23, 173–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimpel P., Lee Y.L., Sobota R.M., et al. (2017). Nesprin-1α-dependent microtubule nucleation from the nuclear envelope via Akap450 is necessary for nuclear positioning in muscle cells. Curr. Biol. 27,2999–3009.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan I.M. (1998). The fission yeast microtubule cytoskeleton. J. Cell Sci. 111, 1603–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson M.E., Setty T.G., Paoletti A., et al. (2005). Efficient formation of bipolar microtubule bundles requires microtubule-bound γ-tubulin complexes. J. Cell Biol. 169, 297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiodice I., Staub J., Setty T.G., et al. (2005). Ase1p organizes antiparallel microtubule arrays during interphase and mitosis in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 1756–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch E.M., Groocock L.M., Borek W.E., et al. (2014). Activation of the γ-tubulin complex by the Mto1/2 complex. Curr. Biol. 24,896–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroyama A., and Lechler T. (2017). Microtubule organization, dynamics and functions in differentiated cells. Development 144, 3012–3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry S., and Vale R.D. (2015). Microtubule nucleation at the centrosome and beyond. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 1089–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbauer U., Zolghadr K., Muyldermans S., et al. (2008). A versatile nanotrap for biochemical and functional studies with fluorescent fusion proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7, 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samejima I., Miller V.J., Groocock L.M., et al. (2008). Two distinct regions of Mto1 are required for normal microtubule nucleation and efficient association with the γ-tubulin complex in vivo. J. Cell Sci. 121, 3971–3980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samejima I., Miller V.J., Rincon S.A., et al. (2010). Fission yeast Mto1 regulates diversity of cytoplasmic microtubule organizing centers. Curr. Biol. 20, 1959–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez A.D., and Feldman J.L. (2017). Microtubule-organizing centers: from the centrosome to non-centrosomal sites. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 44, 93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M., Vardy L., Angel Garcia M., et al. (2004). Interdependency of fission yeast Alp14/TOG and coiled coil protein Alp7 in microtubule localization and bipolar spindle formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 1609–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawin K.E., Lourenco P.C., and Snaith H.A. (2004). Microtubule nucleation at non-spindle pole body microtubule-organizing centers requires fission yeast centrosomin-related protein mod20p. Curr. Biol. 14, 763–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawin K.E., and Snaith H.A. (2004). Role of microtubules and tea1p in establishment and maintenance of fission yeast cell polarity. J. Cell Sci. 117, 689–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawin K.E., and Tran P.T. (2006). Cytoplasmic microtubule organization in fission yeast. Yeast 23, 1001–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Li T., Niu X., et al. (2018). The J-domain co-chaperone Rsp1 interacts with Mto1 to organize non-centrosomal microtubule assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 30, 256–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran P.T., Marsh L., Doye V., et al. (2001). A mechanism for nuclear positioning in fission yeast based on microtubule pushing. J. Cell Biol. 153, 397–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran P.T., Paoletti A., and Chang F. (2004). Imaging green fluorescent protein fusions in living fission yeast cells. Methods 33, 220–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z., Su W., Lou H., et al. (2018). Trafficking pathway between plasma membrane and mitochondria via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R.R., Vaisberg E.V., Ding R., et al. (1998). cut11+: a gene required for cell cycle-dependent spindle pole body anchoring in the nuclear envelope and bipolar spindle formation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 2839–2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., and Akhmanova A. (2017). Microtubule-organizing centers. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 33, 51–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Liu H., Zhu L., et al. (2019). Microtubule-bundling protein Spef1 enables mammalian ciliary central apparatus formation. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Schwartz C., Wee L., et al. (2006). The fission yeast transforming acidic coiled coil-related protein Mia1p/Alp7p is required for formation and maintenance of persistent microtubule-organizing centers at the nuclear envelope. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 2212–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S., and Chang F. (2005). Effects of γ-tubulin complex proteins on microtubule nucleation and catastrophe in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 2719–2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S., Tran P.T., Daga R.R., et al. (2004). Rsp1p, a J domain protein required for disassembly and assembly of microtubule organizing centers during the fission yeast cell cycle. Dev. Cell 6, 497–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.