Abstract

Background

It is common for people not to take antidepressant medication as prescribed, with around 50% of people likely to prematurely discontinue taking their medication after six months. Community pharmacists may be well placed to have a role in antidepressant management because of their unique pharmacotherapeutic knowledge and ease of access for people. Pharmacists are in an ideal position to offer proactive interventions to people with depression or depressive symptoms. However, the effectiveness and acceptability of existing pharmacist‐based interventions is not yet well understood. The degree to which a pharmacy‐based management approach might be beneficial, acceptable to people, and effective as part of the overall management for those with depression is, to date, unclear. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) will help answer these questions and add important knowledge to the currently sparse evidence base.

Objectives

To examine the effects of pharmacy‐based management interventions compared with active control (e.g. patient information materials or any other active intervention delivered by someone other than the pharmacist or the pharmacy team), waiting list, or treatment as usual (e.g. standard pharmacist advice or antidepressant education, signposting to support available in primary care services, brief medication counselling, and/or (self‐)monitoring of medication adherence offered by a healthcare professional outside the pharmacy team) at improving depression outcomes in adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMD‐CTR) to June 2016; the Cochrane Library (Issue 11, 2018); and Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO to December 2018. We searched theses and dissertation databases and international trial registers for unpublished/ongoing trials. We applied no restrictions on date, language, or publication status to the searches.

Selection criteria

We included all RCTs and cluster‐RCTs where a pharmacy‐based intervention was compared with treatment as usual, waiting list, or an alternative intervention in the management of depression in adults over 16 years of age. Eligible studies had to report at least one of the following outcomes at any time point: depression symptom change, acceptability of the intervention, diagnosis of depression, non‐adherence to medication, frequency of primary care appointments, quality of life, social functioning, or adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently, and in duplicate, conducted all stages of study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment (including GRADE). We discussed disagreements within the team until we reached consensus. Where data did not allow meta‐analyses, we synthesised results narratively.

Main results

Twelve studies (2215 participants) met the inclusion criteria and compared pharmacy‐based management with treatment as usual. Two studies (291 participants) also included an active control (both used patient information leaflets providing information about the prescribed antidepressant). Neither of these studies reported depression symptom change. A narrative synthesis of results on acceptability of the intervention was inconclusive, with one study reporting better acceptability of pharmacy‐based management and the other better acceptability of the active control. One study reported that participants in the pharmacy‐based management group had better medication adherence than the control participants. One study reported adverse events with no difference between groups. The studies reported no other outcomes.

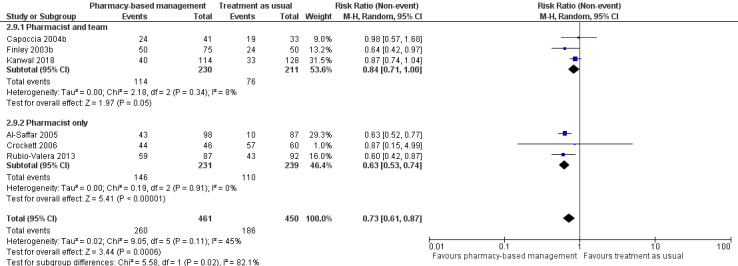

Meta‐analyses comparing pharmacy‐based management with treatment as usual showed no evidence of a difference in the effect of the intervention on depression symptom change (dichotomous data; improvement in symptoms yes/no: risk ratio (RR), 0.95, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.86 to 1.05; 4 RCTs, 475 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; continuous data: standard mean difference (SMD) ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.10; 5 RCTs, 718 participants; high‐certainty evidence), or acceptability of the intervention (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.45; 12 RCTs, 2072 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). The risk of non‐adherence was reduced in participants receiving pharmacy‐based management (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.87; 6 RCTs, 911 participants; high‐certainty evidence). We were unable to meta‐analyse data on diagnosis of depression, frequency of primary care appointments, quality of life, or social functioning.

Authors' conclusions

We found no evidence of a difference between pharmacy‐based management for depression in adults compared with treatment as usual in facilitating depression symptom change. Based on numbers of participants leaving the trials early, there may be no difference in acceptability between pharmacy‐based management and controls. However, there was uncertainty due to the low‐certainty evidence.

Plain language summary

Pharmacies might be able to support people with their depression medicines

Background

Some people with depression find it difficult to take their depression medicines (often called 'antidepressants') as prescribed by their doctor. This can mean that the medicines do not work properly and people might not get better or might even get worse. It could be that pharmacists and their teams can help people with their depression treatment in ways that their family doctor (general practitioner (GP)) cannot. Pharmacies are based within the community, easier to get to, and people may feel more comfortable telling a pharmacist about their mood. However, there are not many studies to tell us if this works.

Study characteristics

We searched medical databases for well‐designed studies that compared a group of adults with depression who received additional help with their depression medicines from their pharmacy with a group of adults with depression who received their treatment as usual.

The evidence is current to 14 December 2018.

Key results and certainty of the evidence

We found 12 studies with over 2000 adults taking part. They compared pharmacy‐based support with treatment as usual, for example, basic information about their medicines or signposting to other services only. We found that additional support given by the pharmacist was no better at reducing people's depression than their treatment as usual. The studies also showed that people may have liked both approaches the same, although we are uncertain about the results as the evidence was of low certainty.

The studies did show that people who received support from their pharmacy were more likely to take their antidepressants as prescribed. We were not able to combine information from the included studies on other outcomes we were interested in (diagnosis of depression, frequency of healthcare appointments, quality of life, social functioning, or side effects).

We found no difference in effectiveness when people with depression received additional support from a pharmacist compared with treatment as usual.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Pharmacy‐based management (pharmacist with or without wider team) compared to treatment as usual for depression in adults.

| Pharmacy‐based management (pharmacist with or without wider team) compared to treatment as usual for depression in adults | |||||

| Patient or population: adults Setting: primary care practices, hospitals, and pharmacies Intervention: pharmacy‐based management (pharmacist with or without wider team) Comparison: treatment as usual | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with treatment as usual | Risk difference with pharmacy‐based management (pharmacist with or without wider team) | ||||

| Depression symptom level: improvement (intervention endpoint) | 475 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | RR 0.95 (0.86 to 1.05) | Study population | |

| 345 per 1000 | 17 fewer per 1000 (48 fewer to 17 more) | ||||

| Depression symptom level: change from baseline mean depression score (intervention endpoint) | 718 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | — | The mean change from baseline mean depression score (intervention endpoint) was 0 | SMD 0.04 lower (0.19 lower to 0.1 higher) |

| Acceptability of the intervention (as measured by participants not attending follow‐up) | 2072 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | RR 1.09 (0.81 to 1.45) | Study population | |

| 285 per 1000 | 26 more per 1000 (54 fewer to 128 more) | ||||

| Diagnosis of depression | 368 (3 RCTs) | — | — | We were unable to combine these studies in a meta‐analysis as they reported findings using different depression measures at different time points. The effectiveness of pharmacy‐based management on a diagnosis of depression (or depression remission) remains unclear. | |

| Non‐adherence to medication | 911 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | RR 0.73 (0.61 to 0.87) | Study population | |

| 413 per 1000 | 112 fewer per 1000 (161 fewer to 54 fewer) | ||||

| Frequency of primary care appointments | 74 (1 RCT) | — | — | At 12 months, there were no significant differences between treatment groups in the number of visits to healthcare providers; this was evident in overall visits, and in subgroup analyses of specific healthcare providers, including those of primary care. | |

| Quality of life | 239 (1 RCT) | — | — | Overall, there was no significant differences in health‐related quality of life between the intervention group and the control group at 3 and 6 months. | |

| Social functioning | 125 (1 RCT) | — | — | At 6 months, there was no significant changes in WSDS scores between intervention and control groups. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; WSDS: Work and Social Disability Scale. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

aEffect estimates of individual studies on either side of the line of no effect. Pooled effect driven by the largest study (Kanwal 2018). bEffect estimates of individual studies on either side of the line of no effect, including several where the confidence interval did not cross the line of no effect in either direction. cSome concern around using number of participants not attending follow‐up as a measure of acceptability of the intervention.

Background

Some services provided by pharmacists may have positive effects on patient health, including improved management of blood pressure and physical function (de Barra 2018). In the UK, antidepressant management for depression is usually achieved through general practitioner (GP) contact and monitoring, which typically involves regular appointments (e.g. every two to four weeks within the first three months) to assess response and tolerance to treatment (NICE 2018). Community pharmacists may be well placed to have a role in antidepressant management because of their unique pharmacotherapeutic knowledge and ease of access for patients. In the UK, there have been efforts to raise public awareness about the role that pharmacists can play as part of multidisciplinary teams to better support people with managing their health conditions, including mental health problems (Royal Pharmaceutical Society 2018).

In England, an estimated 89.2% of the population have access to a community pharmacy within a 20‐minute walk; in the most deprived areas, this figure increases to 99.8% of the population (Todd 2014). Therefore, pharmacy teams (including pharmacists, pharmacy assistants, technicians, healthy living champions) working in community, general practice, or secondary care are ideally placed to offer proactive interventions to people with depression or depressive symptoms. A narrative evidence synthesis by Rubio‐Valera 2014 suggests that pharmacists, specifically, have skills in medication management, provision of drug information, supporting and advising patients about their medicines, and facilitating medication adherence strategies in mental health care. Although pharmacy‐based management interventions can vary in their components, there is scope for these approaches to be used in partnership with other healthcare professionals (e.g. as part of a collaborative care approach). Previous research has suggested that multiprofessional approaches (involving more than one type of health professional, using a structured management plan and scheduled follow‐ups, with enhanced interprofessional communication) have the potential to improve the management of depression in primary care settings (Archer 2012; Gilbody 2003; Gunn 2006). However, despite this potential, and the emerging evidence of the role of pharmacy‐based management interventions for depression, the effectiveness and acceptability of these interventions is not yet well understood.

Description of the condition

Depression can be characterised by low mood; markedly diminished interest or pleasure in activities; impaired cognitive function; fatigue; reduced or disturbed sleep; feelings of worthlessness; and significant decrease or increase in appetite (APA 2013; Otte 2016). The aetiology and maintenance of depression is complex and multifactorial, involving environmental and social factors, as well as genetic and biological factors affecting function changes and regions of the brain (Otte 2016). The condition can be recurrent or long‐term and chronic, and often results in debilitating burden that can interfere with family, home, social, and work responsibilities (Marquez 2016).

Depression is a common mental health problem, with more than 300 million people globally estimated to be living with the condition (WHO 2018). It is the leading cause of disability worldwide and a major contributor to the overall burden of disease (WHO 2018). In extensive global population research on Global Burden of Disease involving 188 countries between 1990 and 2013, depression was one of the top 10 causes of years lived with disability in every country studied, with higher rates of depression typically found in women (Vos 2015). The global point prevalence of depression is reported to be 3.2% for men and 5.5% for women (Ferrari 2013a; Ferrari 2013b; Whiteford 2013). It is estimated that annually 12 billion days of lost productivity (equivalent to 50 million years of work) are attributable to depressive and anxiety disorders (which are often comorbid with each other) combined, with an estimated cost of USD 925 billion, a cost that is anticipated to grow in coming years (Chisholm 2016).

Antidepressants have long been a mainstay of pharmacological treatment for depression (Taylor 2015), and have been reported to be more effective than placebo (Cipriani 2018). However, it is common for patients not to take antidepressant medication as prescribed, with around 50% of patients likely to prematurely discontinue taking their medication after six months. Premature discontinuation of antidepressant therapy has been linked to increased healthcare costs, poor treatment outcomes, and increased risk of relapse and recurrence (Chong 2011).

Description of the intervention

In the treatment as usual (TAU) offered to people with depression, the pharmacist generally has limited involvement with the individual beyond the dispensing of the prescribed antidepressant. Pharmacists or members of the wider pharmacy team (including pharmacy assistants, technicians, healthy living champions, and others who work within the community pharmacy setting) offer basic antidepressant information at the point of dispensing the medication, including information on dosage and important adverse events. They might also signpost the person (back) to primary care services that can provide additional support. Generally, in the UK, the majority of treatment for depression is delivered in primary or secondary care, rather than by the pharmacy team (NICE 2018). Even though there is variation between the standard care offered to people with depression (between, for example, different countries), a common characteristic is that the majority of the information is provided upon request by the person or contingent on the individual taking the initiative ('patient‐led') rather than being offered proactively by the pharmacist or a member of their team.

Pharmacy‐based management interventions can be delivered by a single pharmacist or the wider pharmacy team. In the context of depression, pharmacy‐based management interventions are often delivered in partnership with other healthcare professionals, usually as part of a collaborative care approach. This can be done in several ways: first, by providing patient support, counselling, and education; second, by monitoring or following up adverse effects of medications; and, third, under specific protocols, titrating doses of medications according to patient response (Brook 2005; Capoccia 2004a; Finley 2003a). These interventions can be provided face‐to‐face, using written support materials or visual information relating to medication, through telephone support, or via more formal 'counselling' strategies (Adler 2004; Al‐Saffar 2005), and they may happen alongside the involvement of care managers, mental health specialists, and primary care physicians (Aljumah 2015; Rickles 2005).

As the intervention can be delivered in multiple ways and, given the number of interacting components involved (including the number and difficulty of behaviours required by those delivering or receiving the intervention, the number and potential variability of outcomes, and the degree of flexibility or tailoring of the intervention permitted) it can be described as a complex intervention (Petticrew 2011).

How the intervention might work

A key aspect of effective collaborative care is 'case management' (Gilbody 2003), which has been described as a 'health worker taking responsibility for proactively following up patients, assessing patient adherence to psychological and pharmacological treatments, monitoring patient progress, taking action when treatment is unsuccessful, and delivering psychological support' (Von Korff 2001). Pharmacy‐based management interventions might also involve the delivery of direct psychological interventions to people with depression. An example of this is behavioural activation therapy, which uses principles of operant conditioning by encouraging people with depression to reconnect with environmental positive reinforcement (Ekers 2014a). Behavioural activation can be effective when delivered by paraprofessionals (Gilbody 2017), and current research is exploring if it can be delivered by community pharmacies to people with long‐term physical health problems and subthreshold depression (ISRCTN11290592).

Qualitative work has shown that people tend to form different relationships with a pharmacist compared with other healthcare professionals, such as primary care practitioners or GPs. When people consult with a pharmacist, they do not see themselves as 'patients' and, as such, are more likely to be open and honest in their discussions. In view of this, people might be more likely to discuss certain aspects of their health with a pharmacist compared with other healthcare professionals (Lindsey 2016). Previous research has demonstrated how pharmacist‐based management interventions, including providing patient support, counselling, or coaching patients about their medication and what to expect, can improve antidepressant adherence rates (Al‐Saffar 2005; Brook 2005). It is proposed that pharmacy‐based management interventions, such as engaging patients through face‐to‐face or remote counselling, education and advice (e.g. via teleconferencing, or 'take‐home' audio/visual materials) alongside prescribing and monitoring of antidepressant medication, can also improve depressive symptoms.

Why it is important to do this review

Pharmacists are now engaging with patients in different ways, and it is important to bring together the evidence from randomised controlled trials for pharmacy‐based approaches for depression to determine effectiveness on depressive symptoms and acceptability, as well as adherence levels, adverse effects of prescribed medication, quality of life, and levels of social functioning (Hanlon 2004; Holland 2008; Nkansah 2010; Readdean 2018; Royal 2006; Rubio‐Valera 2013; Yaghoubi 2017). Research involving community household surveys from 21 countries showed that only a minority of people received 'minimally adequate treatment' for depression. This finding equates to one in five people in high‐income countries, and one in 27 in low‐income or low‐ to middle‐income countries, highlighting the need to implement fundamental transformations involving community education and outreach, beyond that currently being offered in primary and secondary care services (Thornicroft 2017). Treatment and support for depression clearly extends beyond the pharmacological; however, due to inadequate resources, antidepressants are more often used than treatment alternatives, for example, psychological therapies (Cipriani 2018).

Against this backdrop, there are policy expectations for pharmacies to expand their professional responsibilities beyond retail and dispensing to encompass more patient‐centred services (Smith 2013), including counselling and support, education, monitoring adverse events, and advice relating to prescribed medication and medicines optimisation and titration, resulting in a trend for community pharmacy medicine management interventions being introduced globally (including in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Switzerland, the US, and England; Latif 2018). Even with a stronger push for pharmacy‐based interventions, there remains ambivalence among pharmacists as to whether the public are willing to engage or would readily accept advice and support (Eades 2011; Rodgers 2016).

Pharmacy‐based management strategies have shown some promising effects in other areas of health care (de Barra 2018). The degree to which a pharmacy‐based management approach might be beneficial, acceptable to patients, effective, and cost‐effective as part of the overall management for those with depression is, to date, unclear. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials will help answer these questions and add important knowledge to the currently sparse evidence base. Our focus is on the impact on improvement in depression as well as acceptability of the intervention rather than medication adherence.

Objectives

To examine the effects of pharmacy‐based management interventions compared with active control, waiting list, or treatment as usual at improving depression outcomes in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered for inclusion all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster‐RCTs where a pharmacy‐based intervention was compared with treatment as usual (TAU), waiting list, or an alternative intervention ('active control', e.g. patient information materials or any other active intervention delivered by someone other than the pharmacist or the wider pharmacy team) in the management of depression. The intervention could have been delivered within the pharmacy or external to the pharmacy (e.g. in a hospital, clinic, online, etc.) or in the community, provided that a pharmacist/wider pharmacy team was involved, or both.

Types of participants

We included all trials of adults (defined as 16 years or over with no upper age limit), with a primary diagnosis of depression according to an international diagnostic classification, including for example, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of Mental Disorders (APA 2013) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (WHO 1992). Studies of participants with depressive symptoms diagnosed via self‐reported scales or questionnaires were also eligible. We included studies in which participants were prescribed an antidepressant (including but not limited to: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; serotonin noradrenaline (norepinephrine) reuptake inhibitors; tricyclic antidepressants; monoamine oxidase inhibitors; tetracyclic antidepressants; noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants) by their primary care physician for the treatment of their diagnosed depression or depressive symptoms.

We included adults as defined as 16 years and over. While we expected most studies to use a cut‐off point of 18 years and above, we note that people consent to take part in research from the age of 16 years. We judged those studies would be relevant to this review if identified and as such used the lower threshold. Furthermore, the age in which people transition from child services to adult services varies from 16 to 18 years across different countries.

Comorbidities

Studies including people with any type of physical (e.g. long‐term conditions, diabetes) or mental health comorbidity (e.g. anxiety) were also eligible, provided that the management of depression was the primary focus of the study.

Types of interventions

We included studies where the intervention was delivered by a pharmacist with or without the input of a (multidisciplinary) team. Studies were excluded if the involvement of the pharmacist was unclear or if they played a background role in the trial intervention, such as prescribing or advising, without coming in contact with the patient.

All comparator interventions were eligible. We grouped studies as follows according to their comparator.

Active control (e.g. other non‐pharmacy‐based management, or psychological intervention).

TAU (i.e. standard pharmacy interaction).

We did not identify any eligible trials that used a waiting list or no treatment as the comparator.

Accordingly, we assessed outcomes for two comparisons.

Pharmacy‐based management versus active control.

Pharmacy‐based management versus TAU.

We conducted subgroup analyses for the primary outcomes to investigate the impact of the involvement of a team (for example, pharmacy assistants, technicians, or healthy living champions; designated 'the wider pharmacy team' in this review) in the delivery of the intervention (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). This was a pragmatic team decision based on the range of eligible studies identified. See Differences between protocol and review for a full explanation.

Types of outcome measures

All outcome measures were eligible as reported by study authors.

Primary outcomes

Depression symptom level: as measured using validated patient‐reported or clinician‐rated depression measures. Included studies used a range of outcome measures to describe symptom level including dichotomous outcomes (improvement in symptoms yes/no) and continuous outcomes (mean depression scores). We combined results from dichotomous outcome measures and results from continuous outcome measures in separate meta‐analyses (see Data synthesis).

Acceptability of the intervention: based on the number of people discontinuing the intervention by leaving the study early.

Secondary outcomes

Diagnosis of depression: as measured using validated clinician‐rated depression measures.

Non‐adherence to medication: the number of participants not taking antidepressant medication as prescribed, assessed via self‐report, through healthcare records, or clinician‐reported adherence scales.

Frequency of primary care appointments (e.g. GP): based on any data relating to primary care service use as reported in the trial.

Quality of life: as assessed using any validated quality of life measure.

Social functioning: as assessed using any validated social functioning measure.

Any adverse event: as reported in the trial.

Timing of outcome assessments

Where possible, we reported outcomes at the following prespecified time points:

intervention endpoint (regardless of length of intervention);

six to 12 months from intervention endpoint ('medium‐term'); and

12 months or more from intervention endpoint ('longer‐term').

We reported these results narratively when meta‐analysis was not possible.

Search methods for identification of studies

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMD‐CTR)

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders (CCMD) Group maintains an archived specialised register of RCTs, the CCMD‐CTR. This register contains over 40,000 reference records (reports of RCTs) for anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, self‐harm, and other mental disorders within the scope of this Group. The CCMD‐CTR is a partially studies‐based register with more than 50% of reference records tagged to about 12,500 individually PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome)‐coded study records. Reports of trials for inclusion in the register were collated from (weekly) generic searches of key bibliographic databases to June 2016, which included: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Ovid MEDLINE (1950 onwards), Embase (1974 onwards), and PsycINFO (1967 onwards), and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials were also sourced from international trial registries; drug companies; the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews; and meta‐analyses. Details of CCMD's core search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders website, with an example of the core MEDLINE search displayed in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches

Searches were developed and conducted in collaboration between the author (RS) and CCMD's information specialist, between the end of November and beginning of December 2018.

1. Cochrane Specialised Register (CCMD‐CTR)

CCMD's information specialist searched the Group's specialised register (CCMD‐CTR‐Studies and CCMD‐CTR‐References) (all years to June 2016), using the following terms (for setting/healthcare professional (only)):

pharmacy or pharmacies or pharmacist* [all fields].

2. Additional bibliographic database searches

We shared the searches of the following bibliographic databases, using relevant subject headings, keywords, and search syntax appropriate to each resource (Appendix 2):

CENTRAL (Issue 11 of 12, December 2018);

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 7 December 2019);

Ovid PsycINFO (1806 to December week 1 2018);

Ovid Embase (1974 to week 49 2018).

We applied no restrictions on date, language, or publication status to the searches.

3. International Trial Registries

We searched ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov), and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/en) via CENTRAL on the Cochrane Registry of Studies (CRS) (27 August 2019) to identify ongoing or unpublished studies.

Two review authors (SJS, NW, AT, or JB) independently considered all abstracts retrieved from the search results for relevancy, and screened full‐text reports to identify studies for inclusion in the review using Covidence software (Covidence 2018). Any disagreements were managed through discussion and referred to a third review author (LW or DE).

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We searched the following databases to identify relevant theses (all available years to 27 August 2019):

DART‐Europe E‐theses Portal (www.dart‐europe.eu);

EThOS – the British Libraries e‐theses online service (ethos.bl.uk);

Open Access Theses and Dissertations (oatd.org);

ProQuest Dissertations and theses database (c/o dissexpress.umi.com).

Reference lists

We checked the reference list of all relevant reviews retrieved from this search together with reports of included studies to help identify additional research relevant to the review. All references identified as potentially relevant were discussed with a second author and deduplicated against records already retrieved through the electronic searches. We screened other systematic reviews and meta‐analyses identified from an earlier search of the Cochrane Library review databases (Issue 4, 2018) (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Health Technology Assessments database (HTA)), and Ovid MEDLINE (from 1946), Embase (from 1974), and PsycINFO (from 1806) to 30 April 2018.

Personal communication

For studies where the published paper(s) did not contain sufficient detail to allow a definitive assessment of eligibility, we made reasonable efforts to obtain missing information from the study authors. Where necessary, we undertook several attempts to contact authors using a range of channels, including email and online research sharing platforms. If we had not received the requested information by the time of submission of the present review, we excluded the study due to 'insufficient data'.

Data collection and analysis

We used Covidence for managing citations, screening titles and abstracts, uploading, and screening full texts (Covidence 2018). We used Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014) and RevMan Web (RevMan Web 2019) alongside Covidence and Excel for data extraction and risk of bias assessments. We used GRADEpro to carry out GRADE assessments and to produce the 'Summary of findings' table (GRADEpro GDT). We conducted meta‐analyses in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014).

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts from the results of the literature searches, including trials potentially relevant to the review and excluding others based on the prespecified criteria. Disagreements were discussed with another review author. Two review authors independently assessed full texts: we obtained full publications of potentially relevant titles/abstracts and made the final eligibility decision. We recorded reasons for exclusion for all full texts that did not meet eligibility criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with another review author.

We documented the flow of studies through the review and presented a PRISMA flow chart in the Results of the search. We reported characteristics of included studies narratively and in tables to show that they met inclusion criteria and provided references to excluded studies alongside reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

We extracted descriptive data pertaining to the methodological, participant, intervention, and outcome characteristics of included studies (including author details; country of study; study design; description of study setting; recruitment process; description of participants including any comorbidities; description of intervention and comparator; primary and secondary outcomes; outcomes reported but not included in this review; and funding and potential conflicts of interest of study authors).

We extracted quantitative data from each trial for the outcomes and time points prespecified in this review. One review author extracted data and another review author checked them, using Covidence (Covidence 2018) and Review Manager (Review Manager 2014; RevMan Web 2019). We resolved disagreements by discussion.

We assessed the usability of our data extraction form to ensure consistency in data extraction between reviewers.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias in included studies using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011a), which addresses the potential for bias in the following six domains:

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of outcome assessment;

blinding of participants and personnel;

incomplete outcome data;

selective reporting;

other sources of bias (e.g. funding, affiliations and declarations of interest of study authors).

One review author assessed risk of bias and another review author checked it. We resolved disagreements by discussion. Where detail reported in the study allowed, domains were rated as 'high' or 'low' risk of bias. The 'unclear' category was used when sufficient detail was not available in the study publication(s) or through contact with the authors.

As per the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, we used an amended risk of bias tool for any included cluster‐RCTs (Higgins 2019a).

Measures of treatment effect

We inputted all data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014) or RevMan Web (RevMan Web 2019). For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), a measure of the relative risk comparison between two groups. For continuous data, we used standardised mean differences (SMDs), where different standardised scales were used to measure the same outcome, and the mean difference (MD) when the same scale was used, with 95% CIs.

For depression symptom level, reporting and outcome measurement were inconsistent across studies (e.g. studies reported a combination of endpoint and change from baseline data). It was not possible to combine endpoint and change from baseline data in meta‐analyses of SMDs that synthesise data from a variety of depression scales. Therefore, where studies reported endpoint data we converted these to change scores (as most studies reported change from baseline).

Where mean change was not reported, we subtracted mean endpoint from mean baseline scores (negative scores indicated a reduction in depression). Similarly, if the standard deviation (SD) of mean change was not reported, we imputed it using the formula in Section 6.5.2.8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019b). The formula requires entering a correlation coefficient. We calculated this correlation coefficient from data reported in Rubio‐Valera 2013 based on the appropriate formula also reported in Section 6.5.2.8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. As Aljumah 2015 did not have the information required to calculate the relevant correlation coefficient, we applied the same correlation used in Rubio‐Valera 2013.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

For any eligible cluster‐RCTs, we incorporated results into the review ensuring that data were analysed within the individual study with consideration of their clustering. As per the guidance of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, we reported data where proper adjustment for the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) had been undertaken (Higgins 2011b).

Trials with multiple treatment arms

We included eligible trial with additional treatment arms. Guided by the effort to avoid double counting of participants, we treated these trials on a case‐by‐case basis when data extracting. Details are reported in Description of studies.

Dealing with missing data

When reported, we extracted data where appropriate imputation methods (e.g. multiple imputation, simple imputation methods with adjustment to the standard error (SE), etc.) or statistical models allowing for missing data have been used by the trialists. However, where such data were not available, we extracted observed case data. Where a combination of imputed and observed case data were available, we investigated the impact of excluding imputed data in a Sensitivity analysis.

Where data were missing, we contacted the trial authors to request further information and documented their responses. For dichotomous outcomes, we used intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis where this was reported. We recorded whether or not ITT analysis was done in the Characteristics of included studies table. We assumed that dropouts from treatment were treatment failures unless trialists expressly stated otherwise.

For continuous data, we contacted trial authors for any missing statistics or calculated them using available reported data. Rubio‐Valera 2013 only presented in 95% CIs, where there is a 95% likelihood that the effect size lies between the upper and lower interval, for depression symptoms at baseline and follow‐up, and these were converted to SD according to Section 6.5.2.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019b). This was then converted to mean change and SD. Crockett 2006 did not present SD with mean change in K‐10 (the depression and anxiety checklist used by the study). The SE was calculated using the P value according to Section 6.5.2.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019b), and the SD was calculated from the SE according to Section 6.5.2.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019b).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic for statistical variation across studies (Deeks 2011). The I2 statistic provides a measure of the proportion of dispersion of effects across studies that reflect real differences rather than random error. Benchmark values of 0% to 40% might not be important, 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity, and 75% to 100% would represent considerable heterogeneity, and we reported 95% CIs. When we detected substantial levels of statistical heterogeneity (via visual inspection of graphs, and the presence of an I2 of 75% or greater, accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2), we closely inspected data to ensure they were inputted correctly. When making this inspection, to avoid imposing arbitrary thresholds, we took into account the magnitude and direction of the observed effect, and the strength of the evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. the P value from Chi2 test, or CI from the I2 test). We also judged clinical and methodological heterogeneity between included trials by inspecting for any outlying people, situations, or methods which we did not expect would arise. We documented and discussed these factors (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity and Sensitivity analysis).

Assessment of reporting biases

For all meta‐analyses including 10 or more trials, we used a funnel plot to help detect instances of reporting biases. We interpreted a symmetrical funnel plot as likely to indicate low publication bias while an asymmetric funnel plot may indicate likely publication bias in included trials (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

Previous systematic reviews have highlighted wide variation in pharmacist‐based interventions and reported outcomes, and have noted high levels of heterogeneity in their data (Bell 2005; Bower 2006; de Barra 2018). We have, therefore, used a random‐effects model for our analyses, taking account of both within‐ and between‐study variance and following the assumption that different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects (Deeks 2011).

We tested heterogeneity using both the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic (as outlined above). If a meta‐analysis was not possible (e.g. due to insufficient data or high heterogeneity), we provided a narrative synthesis of the evidence (Noyes 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Given the different models for delivering pharmaceutical care, we were interested to see if the method of delivery modified the magnitude of the intervention effect. In particular, we were interested to find out if the intervention had to be delivered face‐to‐face by the pharmacist, or if it could be delivered remotely (e.g. telephone). This will have potential implications for future service development. We were also interested if co‐morbidity or depression severity factors moderated the intervention effects. The rationale was that severe depression is often more challenging to treat from a pharmacological viewpoint, so we were interested to establish if this was the case for pharmacy‐based management interventions. Finally, often in a real word setting, people commonly have other comorbidities in addition to depression; in some cases, people have multimorbidity (two or more long‐term conditions); we were interested to establish how applicable our findings were to real world settings for people with other comorbidities.

We conducted the following prespecified subgroup analyses in order to reduce the likelihood of spurious findings on factors that may influence heterogeneity.

1. Participant characteristics

1.1 Participants with physical and mental health comorbidities

Subgrouping trials according to whether or not they provided data for participants either with no comorbidities, or with physical or mental (or both) health comorbidities.

1.2 Baseline severity of depression

As defined as mild, moderate, or severe in individual studies, or using cut‐points for validated rating scales, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ‐9; Kroenke 2001), or the Beck Depression Inventory, second edition (BDI‐II; Beck 1996).

2. Intervention characteristics: delivery method

We conducted a subgroup analysis grouping trials based on the delivery method of the intervention: remote (telephone) or in person. Data were not available for more detailed subgroup analyses.

In addition, we conducted an ad hoc subgroup analysis grouping those trials where the pharmacist was working alone and those where they were working with a team. This analysis was included in the review as part of the decision to analyse studies that included a team together with those that did not, rather than having separate comparisons for each type of study (see Differences between protocol and review).

Subgroup analyses were conducted for primary outcomes only with the exception of the subgroup analysis for presence or absence of a wider pharmacy team, which was also carried out for adherence.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted the following prespecified sensitivity analyses.

1. Risk of bias

If an included trial was rated as a high risk of bias on two or more of the risk of bias domains, we removed this trial to see whether removal would make a substantive difference to the results.

2. Assumptions for missing data

Where meta‐analyses included data from a combination of imputed and completer data, we conducted sensitivity analyses excluding imputed data. We compared these estimates with the main analyses to assess any important differences.

3. Classification of depression

Where a trial did not report how depression is classified, we removed this trial to see whether removal would make a substantive difference to the results.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

To assess the certainty of the evidence available for each outcome across studies (rather than within individual studies), we produced a 'Summary of findings' table using GRADEpro GDT (GRADEpro GDT). The GRADE framework addresses the following five domains:

risk of bias (across studies, for each outcome);

imprecision (between the effect estimates of the studies reporting each outcome);

inconsistency (in the effect estimates of the studies reporting each outcome);

indirectness (of measurement in the studies reporting each outcome);

other (including publication bias).

We chose the following outcomes at intervention endpoint as the most important.

-

Depression symptom level (patient‐reported):

dichotomous outcome: improvement in symptoms yes/no;

continuous outcome: change from baseline in mean depression score.

Acceptability of intervention.

Diagnosis of depression (clinician‐rated).

Non‐adherence to medication.

Frequency of primary care appointments (e.g. GP).

Quality of life.

Social functioning.

One review author performed the GRADE assessment, which was checked by another review author. We resolved disagreements by discussion.

Results

Description of studies

See below for a description of the studies found in our literature searches. Details are reported in the Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

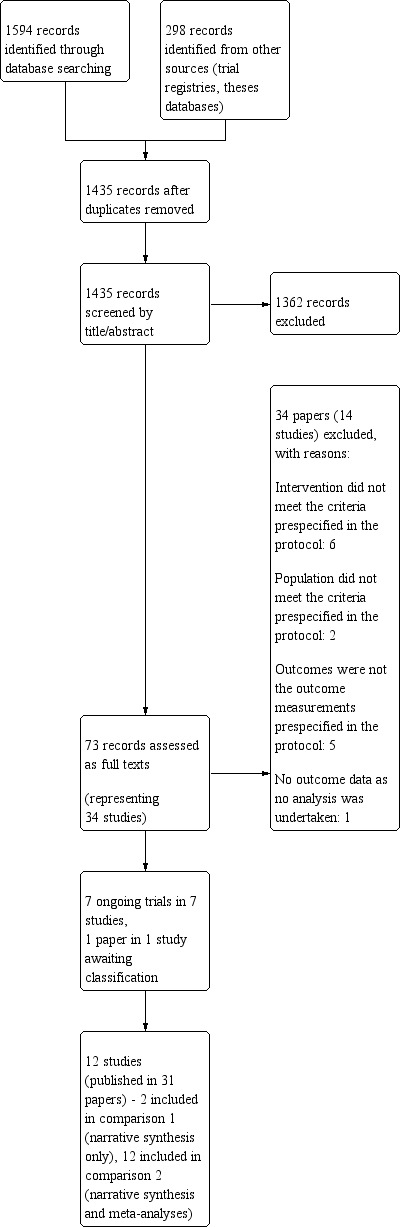

The main database searches identified 1594 records with a further 298 records identified from other sources. After removing duplicates we screened 1435 records for eligibility. We excluded 1362 records after screening titles and abstracts as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. We assessed 73 records at full‐text stage and at this point we combined multiple reports of the same study and began working at study rather than record level. We formally excluded 14 studies (reported in 34 papers) at the full‐text stage. The findings of this review are based on 12 studies (reported in 31 papers). The flow of studies through the review process is illustrated in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We found one potentially relevant unpublished PhD thesis during reference checking of relevant systematic reviews (Harris 2005). Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain this work and consequently any results have not been included in this review. Details of this study can be found in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table.

We identified a conference abstract describing an eligible ongoing study (Phung 2013). Our searches of the trial registers identified six further potentially relevant, ongoing trials (ACTRN12618001105235; ChiCTR‐TRC‐08000726; ISRCTN11290592; NCT01188135; NCT02027259; NCT03591224; see Characteristics of ongoing studies table). Results of these will be included as appropriate when this review is updated.

We contacted the authors of several studies with requests for clarification of their methods or results, or both. This was done either to determine eligibility of a study or to obtain missing data or clarification on a study that was already deemed eligible for inclusion.

Included studies

Twelve studies met the inclusion criteria, 11 of these were individually randomised RCTs. Crockett 2006 was the only cluster‐RCT and the study authors appeared to have adjusted their analyses appropriately to account for clustering. The included studies were published between 2002 and 2016. The majority were carried out in high‐income countries (five in the USA, two in Kuwait, one in Australia, one in the Netherlands, one in Saudi Arabia, and one in Spain) with only one study carried out in an upper‐ to middle‐income country (Brazil). Settings included: primary care (Adler 2004; Capoccia 2004b; Rubio‐Valera 2013); outpatients clinics (Al‐Saffar 2005; Al‐Saffar 2008; Marques 2013); hospital (Aljumah 2015); community pharmacies (Brook 2005; Crockett 2006; Rickles 2005); medical centres (Finley 2003b); and Veteran Affairs clinics (Kanwal 2018). Crockett 2006 was the only study that conducted an intervention in a rural setting.

The 12 studies included 2215 participants. Study samples varied from 63 to 533 participants, with most studies randomising between 100 and 300 participants. One study specified only women (Marques 2013), all other studies included both men and women. Four studies measured comorbidities: Capoccia 2004b; Finley 2003b; and Rubio‐Valera 2013 measured the comorbidities associated with the participants while the intervention presented in Kanwal 2018 was aimed at participants who also had hepatitis C.

Nine studies recruited participants aged 18 years and over (Adler 2004; Aljumah 2015; Al‐Saffar 2008; Brook 2005; Capoccia 2004b; Crockett 2006; Marques 2013; Rickles 2005; Rubio‐Valera 2013). Several studies specified age ranges with both a lower and upper age limits of between 18 and 60 years (Aljumah 2015); 18 and 65 years (Marques 2013); and 18 and 75 years (Rubio‐Valera 2013). One study recruited participants with an age range of 17 to 70 years (Al‐Saffar 2005), and two studies did not report an age range in their inclusion criteria but the mean ages were about 54 to 59 years (Finley 2003b; Kanwal 2018).

In addition to pharmacists, several studies included primary care providers and psychiatrists (Capoccia 2004b), care managers and psychiatrists (Finley 2003b), and nurse depression care manager and psychiatrist (Kanwal 2018). The other nine studies were based on an intervention delivered by a pharmacist only. Capoccia 2004b; Finley 2003b; Kanwal 2018; and Rickles 2005 presented remotely delivered interventions (i.e. contact via telephone); the interventions in the other studies were conducted face‐to‐face.

All interventions were centred around patient education of the condition and the medication that participants were taking: the nature of the depression; possible adverse events; benefits of treatment; and remaining adherent to treatment. Crockett 2006 achieved this by providing participants with an educational video. Management of adverse effects was also an aim of all the interventions; pharmacists were able to alter dosages/titrate based on the information that they were given by participants. Marques 2013 based their intervention on the Dáder Method, a standardised systematic approach aimed at drawing out information relating to patients' health problems and pharmacotherapy.

Self‐management was a key focus of the pharmacy‐based management. Al‐Saffar 2005 and Al‐Saffar 2008 included counselling where patients could talk freely about their concerns. Crockett 2006 emphasised assessing how participants "were going". Rubio‐Valera 2013 additionally encouraged participants to follow GP advice and Adler 2004 aimed to facilitate communication between participants and PCPs. Kanwal 2018 sought to refer participants to speciality health services when necessary. The intervention described in Finley 2003b specifically encouraged participants to continue undertaking activities that they enjoyed. Aljumah 2015 was based on shared decision making designed to assess participant beliefs and their knowledge about medication.

All 12 studies had a TAU arm that was used as a control group, which involved receiving standard communication when collecting their medication, this usually reinforced labelling instructions on the medication, as well as answering any question participants may have had. TAU was viewed as being consistent with the patient education routinely delivered when prescriptions were collected by outpatients. Additionally, Adler 2004 provided participants with the results of the depressive screener that indicated their diagnosis; Kanwal 2018 included referral to speciality mental health clinics; and Rickles 2005 included education and patient monitoring. Al‐Saffar 2005 and Al‐Saffar 2008 had an active control as a third arm, both were based on participant information leaflets (PILs).

All studies used a validated measure of depression to assess participant eligibility for inclusion in the trial. Four studies based diagnosis on the DSM‐IV (APA 2000) (Adler 2004; Aljumah 2015; Capoccia 2004b; Rubio‐Valera 2013); and one study used the ICD‐10 (International Classification of Diseases 10th edition) (Marques 2013). Two studies used the HAMD‐17 (Hamilton Depression Rating) scale (Al‐Saffar 2005; Al‐Saffar 2008). Other measures included: BDI‐II (Rickles 2005); BIDS (Brief Index for Depression Symptoms) (Finley 2003b); PHQ‐9 (Kanwal 2018); SCL‐13 (Symptom Checklist‐13) (Brook 2005); and K‐10 (anxiety and depression checklist) (Crockett 2006).

The primary outcomes of this study were change in depressive symptoms and acceptability of the intervention. The majority of studies measured depression outcomes, either as a symptom change using a change in mean depression score or by means of cut‐off scores on depression measures presented as dichotomous measures. Eleven studies did not present change in depressive symptoms (Adler 2004; Aljumah 2015; Al‐Saffar 2005; Al‐Saffar 2008; Brook 2005; Capoccia 2004b; Finley 2003b; Kanwal 2018; Marques 2013; Rickles 2005; Rubio‐Valera 2013). Adler 2004 did not provide usable depression symptom change data and correspondence with the authors did not provide the necessary information. For all studies, we assessed the acceptability of the intervention based on the number of participants discontinuing the intervention by leaving the study early as specified in our protocol.

Secondary outcome measures included: diagnosis of depression (presented as remission of depression); non‐adherence to medication; frequency of primary care appointments; quality of life; social functioning; and any adverse event. Three studies measured depression remission (Finley 2003b; Kanwal 2018; Marques 2013). Eight studies included a measure of medication adherence (Adler 2004; Al‐Saffar 2005; Aljumah 2015; Capoccia 2004b; Crockett 2006; Finley 2003b; Kanwal 2018; Rubio‐Valera 2013). Two studies measured use of primary care providers and resource utilisation (Capoccia 2004b; Finley 2003b). Five studies presented quality of life (Adler 2004; Aljumah 2015; Brook 2005; Capoccia 2004b; Rubio‐Valera 2013). One study measured social functioning (Finley 2003b). Four studies measured adverse events, including adverse effects and death (Adler 2004; Al‐Saffar 2005; Kanwal 2018; Rubio‐Valera 2013).

Beyond this, most studies reported outcomes that were not prespecified in our protocol. See the Characteristics of included studies table for further details.

Excluded studies

We formally excluded 14 studies. We excluded six studies as the intervention did not meet the criteria prespecified in our protocol (Sampson 2019), often this was due to the pharmacist's involvement being unclear or less than our protocol specification. Two studies had an illegible population. Five studies did not measure our outcomes. One study had only three participants who finished phase one of the intervention and the outcome data were not analysed. Each excluded study and the reason for its exclusion are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

As per the methods prespecified in our protocol (Sampson 2019), we investigated the impact of risk of bias in included studies in sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis). We excluded any studies that were at high risk of bias in two or more domains from the analyses (Adler 2004; Finley 2003b; Marques 2013). Results of the sensitivity analyses are reported in the Effects of interventions section.

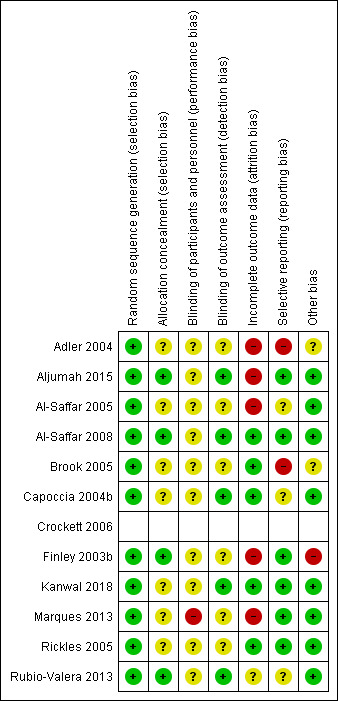

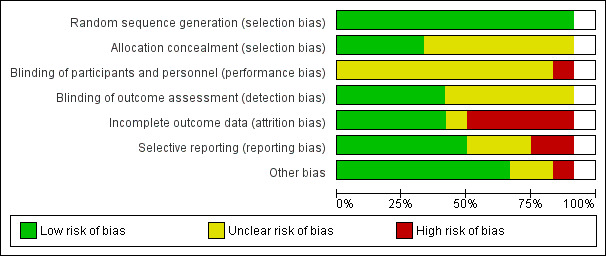

A visual summary of the risk of bias in the included studies is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias summary.*

*Risk of bias assessment for Crockett 2006 is missing from this graph as the risk of bias assessment for this cluster‐RCT was conducted separately, see Additional tables.

3.

Risk of bias graph*

*Risk of bias assessment for Crockett 2006 is missing from this graph as the risk of bias assessment for this cluster‐RCT was conducted separately, see Additional tables.

Crockett 2006 was the only cluster RCT in the included studies. It was not possible to analyse the risk of bias of a cluster RCT in the same table as the other 11 studies; Table 2 presents the risk of bias for Crockett 2006. The study was at low risk for bias arising from the randomisation process. However, there were some concerns of bias arising from the timing of identification and recruitment of participants in relation to timing of randomisation as there was no mention of blinding in either papers. Bias due to deviations from intended interventions was high as the authors stated that "four of the control pharmacists were identified (after randomisation) as delivering a service to their patients, which paralleled that being provided by the intervention pharmacists. This had the potential to confound the results" (p. 267). Bias due to missing outcome data was at low risk. There was a low risk of bias for measurement of the outcome. Finally, there was no evidence of selective reporting so the risk of reporting bias was low.

1. Crockett 2006 risk of bias tablea.

| Bias domain | Judgement | Support for judgement |

| 1. Bias arising from the randomisation process | Low | Quote: "recruited pharmacies were grouped into clusters by geographical area; the clusters were randomly allocated to one of two groups: control and intervention" (p. 264). |

| 2. Bias arising from the timing of identification and recruitment of individual participants in relation to timing of randomisation | Some concerns | No blinding mentioned. |

| 3. Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | High | Quote: "four of the control pharmacists were identified (after randomisation) as delivering a service to their patients, which paralleled that being provided by the intervention pharmacists. This had the potential to confound the results" (p. 267). |

| 4. Bias due to missing outcome data | Low | Complete data were obtained on 106 participants, 60 control and 46 intervention. |

| 5. Bias in measurement of the outcome | Low | 1 measure, set measures; no evidence of bias |

| 6. Bias in selection of reporting | Low | No evidence of selective reporting |

aAs Crockett 2006 was a cluster RCT a custom 'Risk of bias' table was required.

Allocation

Overall, all studies were at low risk of selection bias (random sequence generation). Allocation concealment was unclear for most studies (Adler 2004; Al‐Saffar 2005; Brook 2005; Capoccia 2004b; Crockett 2006; Kanwal 2018; Marques 2013; Rickles 2005), with four having a low risk of bias (Aljumah 2015; Al‐Saffar 2008; Finley 2003b; Rubio‐Valera 2013).

Blinding

Regarding blinding of participants and personnel, 11 studies were at unclear risk (Adler 2004; Aljumah 2015; Al‐Saffar 2005; Al‐Saffar 2008; Brook 2005; Capoccia 2004b; Crockett 2006; Finley 2003b; Kanwal 2018; Rickles 2005; Rubio‐Valera 2013). Due to the nature of the studies, it was difficult to blind either those participating or delivering the interventions. One study was at high risk as the authors reported five participants in the control group received pharmaceutical guidance that was not characterised as the intervention (Marques 2013).

The risk of detection bias (blinding of outcome and assessment) was low for five studies (Al‐Saffar 2008; Aljumah 2015; Capoccia 2004b; Kanwal 2018; Rubio‐Valera 2013), and unclear for seven studies (Adler 2004; Al‐Saffar 2005; Brook 2005; Crockett 2006; Finley 2003b; Marques 2013; Rickles 2005).

Incomplete outcome data

The risk of attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) was low for six studies (Al‐Saffar 2008; Brook 2005; Capoccia 2004b; Crockett 2006; Kanwal 2018; Rickles 2005), unclear for one study (Rubio‐Valera 2013), and high risk for five studies (Adler 2004: high proportion of missing data, participant numbers at enrolment/follow‐up unclear/inconsistent; Al‐Saffar 2005: high rate of unexplained withdrawals; Aljumah 2015: reported completer data only; Finley 2003b: follow‐up surveys returned primarily by participants who were doing well; Marques 2013: high rate of unexplained withdrawals/dropouts).

Selective reporting

The risk of reporting bias was low for seven studies (Al‐Saffar 2008; Aljumah 2015; Crockett 2006; Finley 2003b; Kanwal 2018; Marques 2013; Rickles 2005), unclear for three studies (Al‐Saffar 2005; Capoccia 2004b; Rubio‐Valera 2013), and high for two studies (Adler 2004; Brook 2005: several prespecified outcomes not reported).

Other potential sources of bias

In nine studies, we did not find any other potential sources of bias (Aljumah 2015; Al‐Saffar 2005; Al‐Saffar 2008; Capoccia 2004b; Crockett 2006; Kanwal 2018; Marques 2013; Rickles 2005; Rubio‐Valera 2013). Two studies were at an unclear risk of bias from other sources (Adler 2004: unexplained differences in the effectiveness of the intervention dependent on timing of enrolment; Brook 2005: funded by a pharmaceutical company). Finley 2003b was at high risk of bias; the corresponding author confirmed that there was a high risk of selection bias in the return of the survey questionnaires at follow‐up.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison 1: pharmacy‐based management (pharmacist with or without wider team) versus active control

Two studies (291 participants) compared pharmacy‐based management with an active control as part of three‐armed trials (Al‐Saffar 2005; Al‐Saffar 2008). In both trials, the active control treatment involved participants receiving a PIL. It was not possible to combine any of the reported outcome data in meta‐analyses.

Primary outcomes

1. Depression symptom level

Neither study reported depression symptom level.

2. Acceptability of the intervention

Al‐Saffar 2005 reported that 44/98 (44.9%) participants assigned to the pharmacy‐based management arm did not attend the five‐month follow‐up. Of the 93 participants assigned to the active control arm, 51 (54.8%) did not attend follow‐up. Al‐Saffar 2008 reported that 33/50 (66.0%) participants assigned to the pharmacy‐based management arm did not attend the six‐week follow‐up. For the active control arm, 21/50 (42.0%) participants did not attend six‐week follow‐up.

This shows that for Al‐Saffar 2005 the pharmacy‐based management arm was more acceptable to participants, but for Al‐Saffar 2008, the active control arm was more acceptable. Therefore, it is unclear whether active controls or pharmacy‐based management are more acceptable for participants.

Secondary outcomes

1. Diagnosis of depression

Neither study reported diagnosis of depression.

2. Non‐adherence to medication

Al‐Saffar 2005 measured adherence by self‐report and tablet counting as the number of participants who reported that they were taking their tablets exactly as prescribed and whose 'tablet‐count ratio' was 80–100% inclusive. At two months, people who received the educational intervention had higher odds of being 'adherent' (for counselling and leaflet: OR 5.09, 95% CI 2.35 to 11.03; for leaflet: OR 3.15, 95% CI 1.42 to 6.99). At five months, people who received the educational intervention had higher odds of being 'adherent' (for counselling and leaflet: OR 6.02, 95% CI 2.79 to 13.00; for leaflet: OR 2.83, 95% CI 1.26 to 6.32). Overall, people who received the pharmacist intervention were more likely to be adherent to their antidepressant medication.

3. Frequency of primary care appointments (e.g. GP)

Neither study reported frequency of primary care appointments.

4. Quality of life

Neither study reported quality of life.

5. Social functioning

Neither study reported social functioning.

6. Any adverse event

In Al‐Saffar 2005, the majority of people in the study reported an adverse effect at two months, which appeared to be related to the pharmacology of the antidepressant medication. The number of reported adverse effects appeared to be similar across all groups. The group receiving the leaflet and pharmacist counselling reported fewer adverse effects. However, there were insufficient data reported to judge whether this difference was clinically meaningful.

Comparison 2: pharmacy‐based management (pharmacist with or without wider team) versus treatment as usual

Twelve studies (2072 participants) compared pharmacy‐based management with TAU (Adler 2004; Aljumah 2015; Al‐Saffar 2005; Al‐Saffar 2008; Brook 2005; Capoccia 2004b; Crockett 2006; Finley 2003b; Kanwal 2018; Marques 2013; Rickles 2005; Rubio‐Valera 2013). This section includes the TAU arms of Al‐Saffar 2005 and Al‐Saffar 2008. TAU included advice from the pharmacist reiterating the instructions in the PIL of the antidepressant; standard communication; signposting; routine patient education; and standard patient monitoring. Wherever possible, we combined outcome data in meta‐analyses.

Primary outcomes

1. Depression symptom level

Due to the wide range of measures used in the primary studies to assess depression, we had to make pragmatic decisions weighing up the statistical possibilities of combining continuous and dichotomous data with the desire to produce clinically meaningful results. We outline the methods used to combine studies for this outcome in Data synthesis. In short, we decided to analyse separately improvement in depression (dichotomous data, Analysis 1.1) and change from baseline mean depression score (continuous data, Analysis 1.2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pharmacy‐based management (pharmacist with or without wider team) versus treatment as usual, Outcome 1 Depression symptom level: improvement (intervention endpoint).

1.2. Analysis.

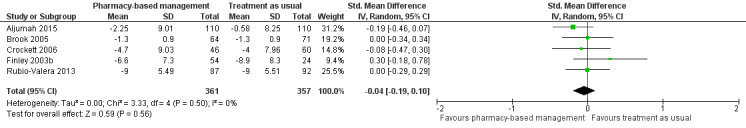

Comparison 1 Pharmacy‐based management (pharmacist with or without wider team) versus treatment as usual, Outcome 2 Depression symptom level: change from baseline mean depression score (intervention endpoint).

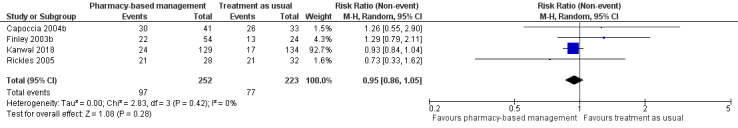

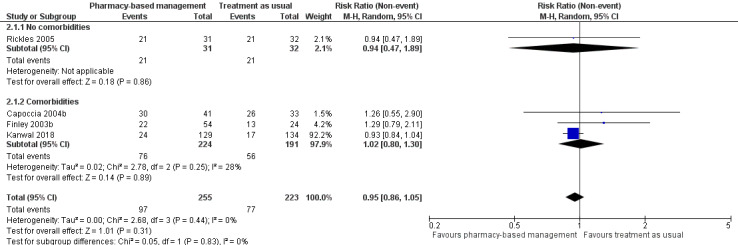

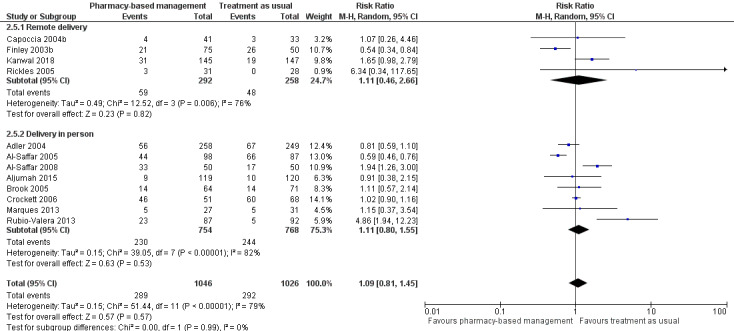

At intervention endpoint, four studies (475 participants) contributed to Analysis 1.1 (Capoccia 2004b; Finley 2003b; Kanwal 2018; Rickles 2005). There was probably no difference in effectiveness between the pharmacy‐based management intervention group and the TAU controls (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.05; I2 = 0%, moderate‐certainty evidence; Figure 4). GRADE assessment of the certainty of the evidence included in this analysis revealed concerns about imprecision in the analyses (the CI was not sufficiently narrow to rule out a difference between interventions and the summary estimate was driven by the largest study, Kanwal 2018).

4.

Primary outcome 1: Improvement in depression (intervention endpoint).

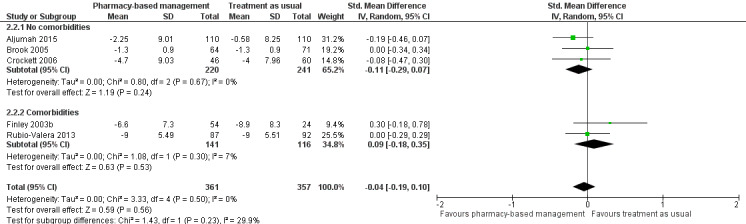

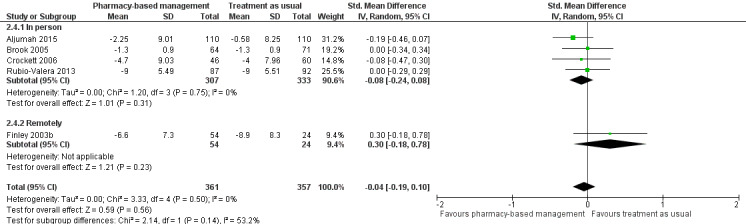

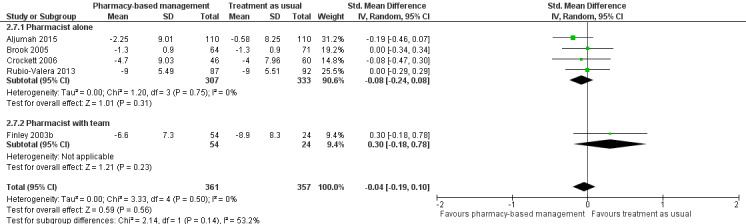

Five studies (718 participants) contributed to Analysis 1.2 (Aljumah 2015; Brook 2005; Crockett 2006; Finley 2003b; Rubio‐Valera 2013). This meta‐analysis found no evidence of a difference in effectiveness between the two groups in change in mean depression score from baseline (SMD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.10; I2 = 0%, high‐certainty evidence; Figure 5).

5.

Primary outcome 1: Change from baseline mean depression score (endpoint).

There was no statistical heterogeneity in these analyses although studies used interventions of different duration.

None of the included studies reported depression outcomes at follow‐up.

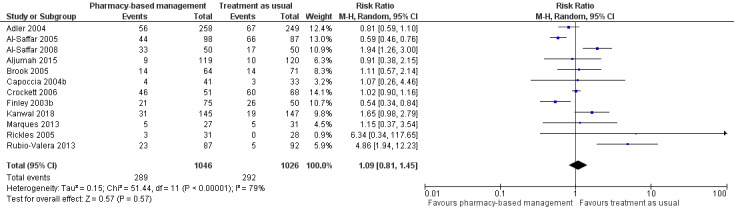

2. Acceptability of the intervention

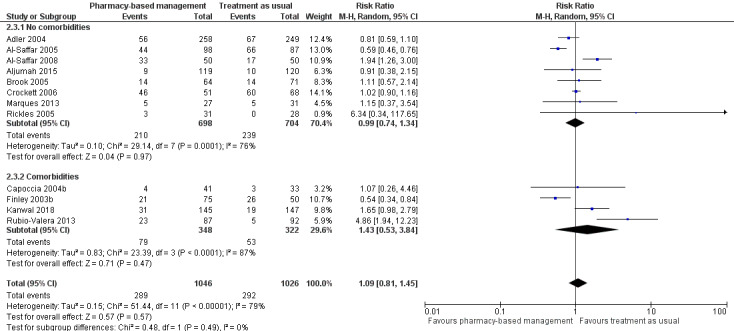

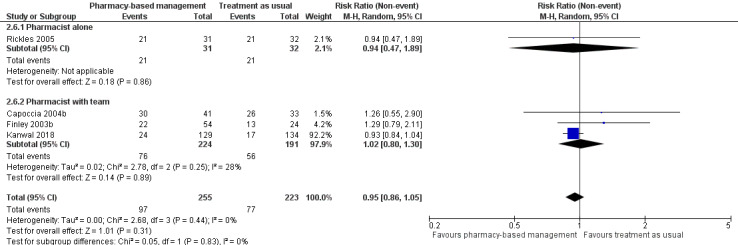

Data for this outcome were extracted from trial publications based on the number of people discontinuing the intervention by leaving the study early using participant numbers at intervention endpoint as defined by the authors. Meta‐analysis of 12 studies (2072 participants) showed there may have been no effect for pharmacy‐based management compared with TAU on the acceptability of the intervention (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.45; I2 = 79%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3). The considerable heterogeneity observed in this analysis might be explained by the difference in treatment duration (six weeks to 12 months). However, regardless of treatment duration, most studies reported equivocal results, with wide CIs often spanning the line of no effect (see Figure 6). We comment on the issues around using number of participants leaving the trial as a measure of acceptability in the Discussion. Given the concerns about imprecision and indirectness in this analysis, we cannot be certain whether or not there is a difference in effectiveness between pharmacy‐based management and TAU.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pharmacy‐based management (pharmacist with or without wider team) versus treatment as usual, Outcome 3 Acceptability of the intervention (as measured by participants not attending follow‐up).

6.

Primary outcome 2: Acceptability of the intervention.

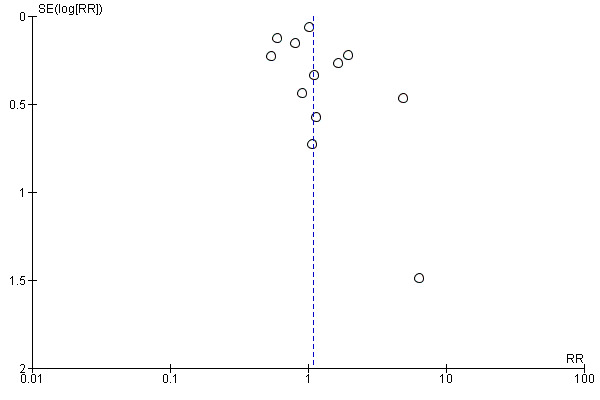

As specified in Assessment of reporting biases, we created and scrutinised a funnel plot for this analysis (Figure 7). Visual inspection of this plot suggested that bigger studies with non‐significant results are relatively well balanced. However, as is often the case, smaller studies with non‐significant findings may be missing. Overall, we do not feel that the shape of the funnel plot gives reason to assume a high risk of reporting bias within the included studies.

7.

Funnel plot for Primary outcome 2: Acceptability of the intervention (Analysis 2.3).

Secondary outcomes

1. Diagnosis of depression

Three studies (368 participants) reported diagnosis of depression or remission (Finley 2003b; Kanwal 2018; Marques 2013). This was defined as a participant scoring below a certain cut‐off point on a depression scale. We were unable to combine these studies in a meta‐analysis as they reported findings using different depression measures at different time points. The effectiveness of pharmacy‐based management on a diagnosis of depression (or depression remission) remains unclear.

At intervention endpoint, Finley 2003b reported that 30/54 (55.6%) participants in the pharmacy‐based management arm had a score of less than 9 on the BIDS depression scale which indicated remission. For the TAU arm, this proportion was 14/24 (58.3%). This suggests a slightly higher proportion of participants in the TAU achieved remission by the end of the intervention than the pharmacy‐based management arm. However, this difference might not be clinically significant as there was a high risk of attrition bias in this trial. The paper did not conduct a statistical test to compare groups for this outcome.

Kanwal 2018 reported at intervention endpoint that 22/114 (19.3%) participants in the pharmacy‐based management arm had a score of less than 9 on the BIDS depression scale. For the TAU arm this proportion was 9/128 (7.0%). A Chi2 test showed that intervention participants were more likely to experience remission at 12 months (P = 0.004).

Marques 2013 reported that 7/22 (31.8%) participants in the pharmacy‐based management arm achieved remission, defined by the study authors as a score of less than 11 on the BDI. For the TAU arm, this proportion was 4/26 (15.4%) participants indicating that a higher proportion of those in the pharmacy‐based management arm experienced remission at intervention endpoint. However, the authors did not perform a statistical test for differences between groups.

2. Non‐adherence to medication

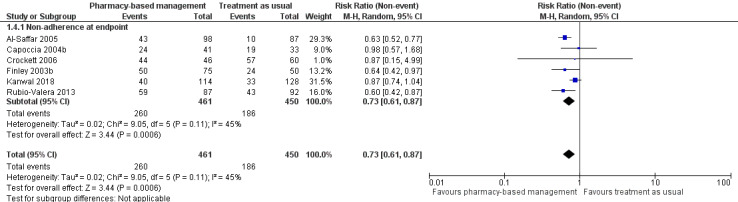

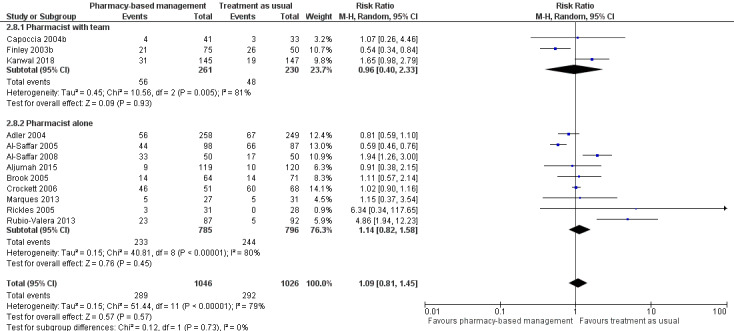

Most of the included studies reported adherence rather than non‐adherence so we extracted these data as reported in the papers. We used the function in Review Manager to swap events and non‐events so that the RR reflected a reduction in non‐adherence (Review Manager 2014). This has the advantage of presenting the forest plots consistently across outcomes so that a pooled effect to the left of the line of no effect indicated benefit for the intervention group.

Al‐Saffar 2005 measured medication adherence by self‐report and tablet counting, presented as a dichotomous variable. Crockett 2006 measured adherence based on a self‐reported dichotomous variable of whether participants were still taking the medication or not. Rubio‐Valera 2013 used computerised pharmacy records to measure non‐adherence defined as refilling less than 80% of the prescribed dosages and thus presented non‐adherence as a dichotomous measure. Capoccia 2004b measured adherence through a self‐reported telephone interview based on the number of days participants said they took the antidepressant medication in the past month. Finley 2003b expressed adherence both as a continuous and dichotomous measure using medication possession ratio (MPR), participants were defined as adherent if they had an MPR of 0.83 and above, as there was no SD provided in the results we opted to use the dichotomous measure. Kanwal 2018 also used MPR to measure adherence but classified a participant as adherent if they had an MPR greater than 90% and presented the data as a dichotomous measure. It was deemed suitable to perform a meta‐analysis.

Aljumah 2015 measured adherence using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS), a continuous scale with scores ranging from 0 to 8, when higher scores represented better adherence; a score of less than 6 indicated poor adherence. Brook 2005 measured adherence using an electronic tablet dispenser called an eDEM that recorded each opening of the box by the day, hour, and minute, this was combined with pharmacy record data and presented as a continuous measure. Rickles 2005 measured medication non‐adherence using pharmacy refill records over a six‐month period (i.e. measured up to three months after the intervention concluded); it was presented continuously as percentage of dosages missed per participant.

At intervention endpoint, the six studies (911 participants) with dichotomous measures contributed to the analysis (Al‐Saffar 2005; Capoccia 2004b; Crockett 2006; Finley 2003b; Kanwal 2018; Rubio‐Valera 2013). The meta‐analysis suggests a 27% reduced risk of non‐adherence in the pharmacy‐based management group compared with TAU (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.87; I2 = 45%; high‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4; Figure 8). The heterogeneity in this analysis might have been related to the difference in adherence measures used or some uncertainty (due to unclear reporting) about when exactly adherence was measured, or both.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pharmacy‐based management (pharmacist with or without wider team) versus treatment as usual, Outcome 4 Non‐adherence to medication.

8.

Secondary outcome 2: Non‐adherence.

3. Frequency of primary care appointments

Capoccia 2004b followed the number of clinic visits accessed by study participants over 12 months. Clinic visits included primary care providers, psychiatrists, emergency department, counsellors, and alternative medicine providers. At 12 months, there were no significant differences between treatment groups in the number of visits to healthcare providers; this was evident in overall visits, and in subgroup analyses of specific healthcare providers, including those of primary care.

4. Quality of life