Abstract

In the search for improved selective antagonist ligands of the A2B adenosine receptor, which have the potential as antiasthmatic or antidiabetic drugs, we have synthesized and screened a variety of alkylxanthine derivatives substituted at the 1-, 3-, 7-, and 8-positions. Competition for 125I-ABOPX (125I-3-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)-8-(phenyl-4-oxyacetate)-1-propylxanthine) binding in membranes of stably transfected HEK-293 cells revealed uniformly higher affinity (<10-fold) of these xanthines for human than for rat A2B adenosine receptors. Binding to rat brain membranes expressing A1 and A2A adenosine receptors revealed greater A2B selectivity over A2A than A1 receptors. Substitution at the 1-position with 2-phenylethyl (or alkyl/olefinic groups) and at N-3 with hydrogen or methyl favored A2B selectivity. Relative to enprofylline 2b, pentoxifylline 35 was equipotent and 1-propylxanthine 3 was >13-fold more potent at human A2B receptors. Most N-7 substituents did not enhance affinity over hydrogen, except for 7-(2-chloroethyl), which enhanced the affinity of theophylline by 6.5-fold to 800 nM. The A2B receptor affinity-enhancing effects of 7-(2-chloroethyl) vs 7-methyl were comparable to the known enhancement produced by an 8-aryl substitution. Among 8-phenyl analogues, a larger alkyl group at the 1-position than at the 3-position favored affinity at the human A2B receptor, as indicated by 1-allyl-3-methyl-8-phenylxanthine, with a Ki value of 37 nM. Substitution on the 8-phenyl ring indicated that an electron-rich ring was preferred for A2B receptor binding. In conclusion, new leads for the design of xanthines substituted in the 1-, 3-, 7-, and 8-positions as A2B receptor-selective antagonists have been identified.

Introduction

Four extracellular G protein-coupled receptors for adenosine have been identified as follows: A1, A2A, A2B, and A 3.1 A2B receptors, which are coupled to stimulation of adenylyl cyclase2,3 and also lead to a rise in intracellular calcium,4 are involved in the control of vascular tone,5 hepatic glucose balance,6 cell growth and gene expression,7 mast cell degranulation,8 and intestinal water secretion.9 Activation of A2B receptors in human retinal endothelial cells may lead to neovascularization by a mechanism involving increased vascular endothelial growth factor expression.7 Selective xanthine antagonists of the A2B receptor have recently been reported.10,11 Such antagonists are potentially useful in the treatment of asthma,12,13 intestinal disorders,9 and diabetes (through improved glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and suppression of glucose production in hepatocytes).6

On the basis of adenosine receptor binding assays, we have identified several new xanthines with improved potency and selectivity for human A2B receptors.10,14 A P-cyanoanilide derivative in this series, N-(4-cyanophenyl)-2-[4-(2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-2,6-dioxo-1,3-dipropyl-1H-purin-8-yl)phenoxy]acetamide) 1, was shown to be 204-, 255-, and 289-fold selective for human A2B receptors vs human A1, A2A, and A3 receptors, although less selective vs rat A1 and A2A receptors. Compound 1 (100 nM) was shown to completely inhibit calcium mobilization stimulated by 1 μM NECA in HEK-293 (human embryonic kidney) cells expressing human A2B receptors.10

Nonselective radioligands have been used to characterize binding to recombinant human A2B receptors overexpressed in cell lines such as HEK-293. These include 125I-ABOPX (125I-3-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)-8-(phenyl-4-oxyacetate)-1-propylxanthine),15 [3H]8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine,13 and [3H]4-(2-[7-amino-2-{furyl}{1,2,4}triazolo{2,3-a}{1,3,5}triazin-5-ylamino-ethyl)phenol.16 [3H]N-(4-Cyanophenyl)-2-[4-(2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-2,6-dioxo-1,3-dipropyl-1H-purin-8-yl)phenoxy]-acetamide) 1 was recently introduced as a new selective radioligand that bound to human A2B receptors with a kD of 1 nM.17

In the present study, in an effort to better understand the structure–activity relationships (SAR) of antagonist ligands of the A2B adenosine receptor, we have screened a variety of alkylxanthine derivatives substituted at the 1-, 3-, 7-, and 8-positions and synthesized some derivatives that were designed by analysis of the biological results obtained from screening. In this study, previously uncharacterized patterns in the SAR of rat and human A2B receptors have been identified.

Results

Chemistry.

Sixty-five xanthine derivatives (Table 1) were examined as antagonists of binding at the human A2B adenosine receptor. Many of these ligands had been investigated in earlier studies of A1 and A2A receptors.14,18–25,37 Other compounds were synthesized, based on SAR indications that arose during the course of the present study.

Table 1.

Affinities of Xanthine Derivatives in a Radioligand Binding Assay at Human A2B Receptors

| compd | R1 | R3 | R7 | R8 | Kia (nM) | compd | R1 | R3 | R7 | R8 | Kia (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a (theophylline) | Me | Me | H | H | 9070 ± 1490 | 31 | CH2OCH3 | Me | Me | H | 14 000 ± 2400 |

| 2b (enprofylline) | H | Pr | H | H | 4730 ± 270 | 32 | CH2CN | Me | Me | H | 21 600 ± 5200 |

| 3 | Pr | H | H | H | 360 ± 70 | 33 | (CH2)2OC-OCH3 | Me | Me | H | 8710 ± 1320 |

| 4 | propargyl | H | H | H | 552 ± 76 | 34 | CH2COCH3 | Me | Me | H | 20 800 ± 4800 |

| 5 | allyl | H | H | H | 461 ± 18 (4) | 35 (pentoxifylline) | (CH2)4CO-CH3 | Me | Me | H | 5180 ± 2010 |

| 6 | n-Bu | H | H | H | 421 ± 38 (4) | 36 | Me | Propargyl | Me | H | 9480 ± 1340 |

| 7 | 2-phenylethyl | H | H | H | 408 ± 67 (4) | 37 | Pr | H | H | cyclopentyl | 34 ± 10 |

| 8 | cyclopentyl | H | H | H | 965 ± 64 (4) | 38 (CPX) | Pr | Pr | H | cyclopentyl | 63.8 ± 8.3 |

| 9 | Et | Et | H | H | 1770 ± 260 | 39 (8-PT) | Me | Me | H | C6H5 | 415 ± 219 |

| 10 | n-Pr | n-Pr | H | H | 1110 ± 330 (4) | 40 (SPT) | Me | Me | H | C6H4-4-S-O3H | 1330 ± 220 |

| 11 | allyl | allyl | H | H | 1330 ± 240 | 41 | Me | Me | H | C6H4-4-OH | 60.7 ± 3.1 |

| 12 | n-hexyl | n-hexyl | H | H | 7580 ± 1900 | 42 | Me | Me | II | C6H4-4-OCH3 | 394 ± 38 |

| 13 | Et | Me | H | H | 1620 ± 440 | 43 | Me | Me | H | C6H4-4-NO2 | 6940 ± 1960 |

| 14a | propargyl | Me | H | H | 511 ± 52 (4) | 44 | Me | Me | H | C6H4-4-N-(CH3)2 | 289 ± 11 |

| 14b | benzyl | Me | H | H | 10 200 ± 2000 | 45 | Me | Me | II | C6H4-2-CO2H | 11 100 ± 4700 |

| 14c | 2-phenylethyl | Me | H | H | 646 ± 15 | 46 | Me | Me | H | C6H4-3-CO2H | 5530 ± 640 (4) |

| 14d | 3-phenylpropyl | Me | H | H | 2330 ± 250 | 47 | Me | Me | H | C6H3-2,4-(NO2)2 | 15 400 ± 6600 |

| 15 | Me | i-Pr | H | H | 4890 ± 870 | 48 (DPX) | Et | Et | H | C6H5 | 62.0 ± 11.4 |

| 16 | n-Bu | Et | H | H | 1720 ± 160 | 49 | Pr | Pr | H | C6H5 | 18.9 ± 3.2 (4) |

| 17 | i-amyl | i-Bu | H | H | 6240 ± 1340 | 50 | Pr | Pr | H | pyrazine | 79.6 ± 11.3 |

| 18 (caffeine) | Me | Me | Me | H | 10 400 ± 1800 | 51 | allyl | Me | H | C6H5 | 37 ± 6 |

| 19a | Me | Me | 2-Cl-ethyl | H | 1390 ± 200 | 52 | i-amyl | i-Bu | H | C6H5 | 9890 ± 1440 |

| 19b | Me | Me | 3-Cl-propyl | H | 5620 ± 980 | 53 | Pr | Pr | H | C6H3-2,6-F2 | 310 ± 42 |

| 19c | Me | Me | 4-Cl-butyl | H | 15 000 ± 1100 | 54 | Pr | Pr | H | C6H3-2,3-(OH)2 | 125 ± 10 |

| 20 | Me | Me | propargyl | H | 9460 ± 1880 | 55 | Pr | Pr | H | C6H3-2,4-(OH)2 | 20.7 ± 2.0 |

| 21 | Me | Me | allyl | H | 9490 ± 1220 | 56 | Pr | Pr | H | C6H3-2,5-(OH)2 | 138 ± 6.9 |

| 22 | Me | Me | benzyl | H | 19 400 ± 4140 | 57 | Pr | Pr | H | C6H3-2-OH-4-OCH3 | 46.5 ± 0.7 |

| 23 | Me | Me | CH2COOH | H | 27 600 ± 11 400 | 58 | Pr | Pr | H | C6H3-3,5-(OH)2-4-OCH3 | 59.5 ± 7.0 |

| 24 | Me | Me | CH2CN | H | 14 500 ± 300 | 59 | Pr | Pr | H | C6H4-4-NHC-OCH3 | 36.7 ± 9.5 (4) |

| 25 | Me | Me | (CH2)2-NH2 | H | 23 500 ± 6700 | 60 | Pr | Pr | H | C6H3-2-OMe-4-Cl | 6530 ± 570 (4) |

| 26 | Me | Me | (CH2)2OH | H | 17 300 ± 2900 | 61 (XCC) | Pr | Pr | H | C6H4-4-OCH2-CO2H | 40 ± 4 |

| 27 | Me | Me | (CH2)2OCO-CH3 | H | 23 200 ± 8300 | 62 | Pr | Pr | H | C6H3-2-OH-4-OCH2-CO2H | 188 ± 22 |

| 28 | allyl | allyl | Me | H | 3390 ± 760 | 63 | allyl | Me | Me | C6H5 | 11 400 ± 1000 |

| 29 | propargyl | Me | Me | H | 4130 ± 1040 | 64 | allyl | Me | 2-Cl-ethyl | C6H5 | 311 ± 22 |

| 30 | CH2COOH | Me | Me | H | 23 500 ± 7600 | 65 | Pr | Pr | 2-Cl-ethyl | C6H4 | 691 ± 72 |

Displacement of specific [125I]ABOPX binding at human A2B receptors expressed in HEK-293 cells, in membranes, expressed as Ki ± SEM. n = 3, unless noted. Cases in which n = 4 are noted in parentheses.

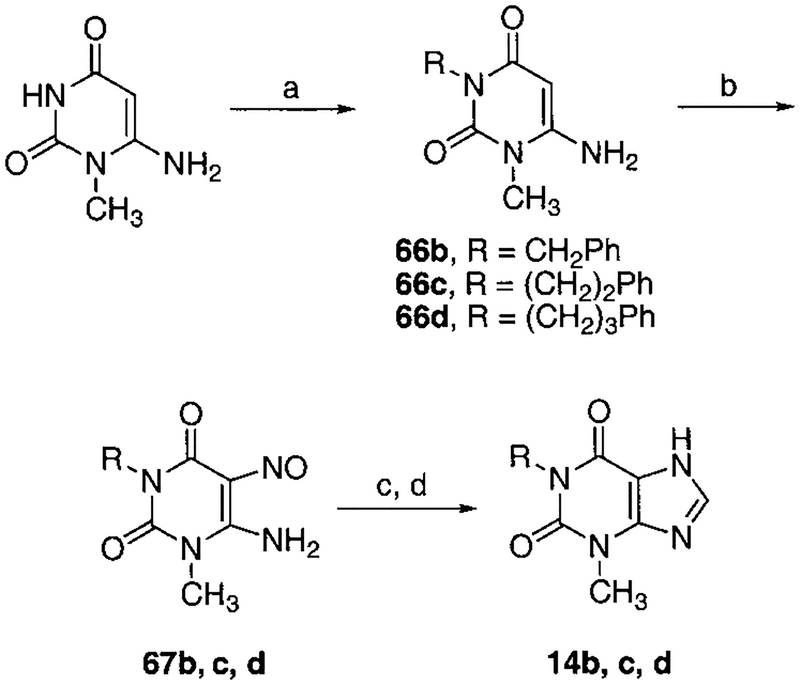

Compounds 14b–d, which were substituted with various phenylalkyl groups in the 1-position, were synthesized in four steps (Scheme 1). Alkylation of 6-amino-1-methyluracil was performed with 10% aqueous NaOH and the appropriate alkyl halide. Compounds 66b–d were converted to xanthines 14b–d according to standard procedures as reported.10,25 The synthesis of several 8-H and 8-aryl derivatives alkylated at the 7-position, 19b, 19c, 64, and 65, was performed using NaH and the alkyl halide in dimethylformamide (DMF) (Schemes 2 and 3). The yields and characterization of the xanthine derivatives prepared are listed in Table 2.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Xanthine Derivatives 14b–da

a Reagents: (a) 10% NaOH, EtOH, R–Br; (b) NaNO2, 6 N HCl, AcOH; (c) Na2S2O4; (d) HC(OMe)3.

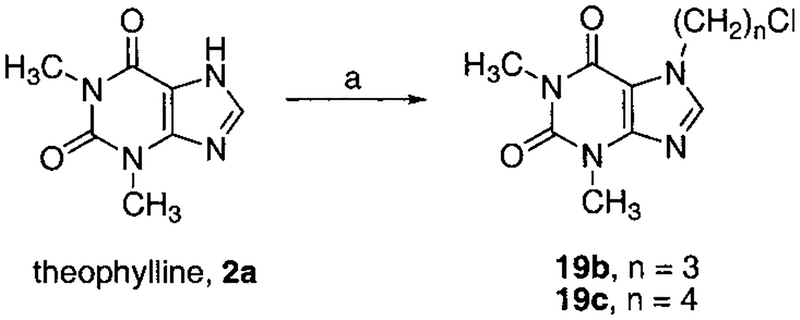

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Xanthine Derivatives 19b,ca

a Reagents: (a) NaH, Br(CH2)nCl, DMF.

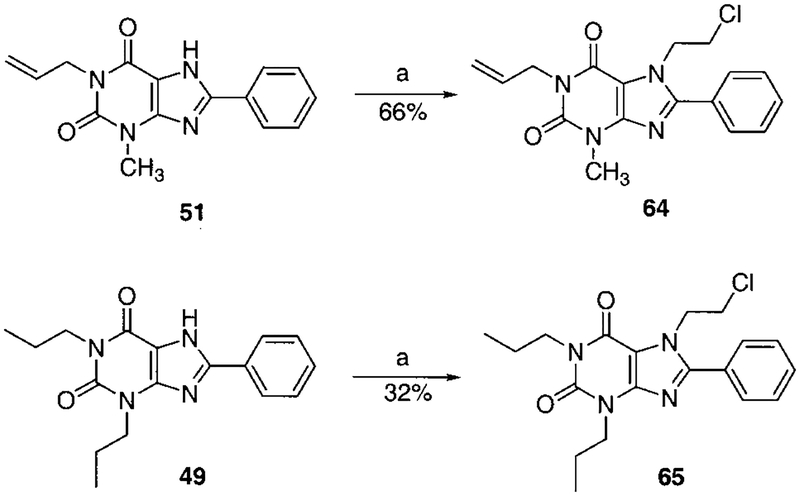

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Xanthine Derivatives 64 and 65a

a Reagents: (a) NaH, Cl2(CH2)2, DMF.

Table 2.

Synthetic Yields and Characterization of Xanthine Derivatives

| compd | formula | yield (%) | analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14b | C13H12N4O2 | 44 | C, H, N |

| 14c | C14H14N4O2·0.2H2O | 32 | C, H, N |

| 14d | C15H16N4O2 | 60 | C, H, N |

| 19b | C10H13ClN4O2 | 88 | C, H, N |

| 19c | C11H15ClN4O2 | 95 | C, H, N |

| 64 | C17H18C1N4O2 | 66 | HRMSa |

| 65 | C19H24ClN4O2 | 32 | HRMSa |

High-resolution mass in positive ion FAB mode determined to be within acceptable limits. Compound 64: calcd, 345.1118; found, 345.1110. Compound 65: calcd, 375.1588; found, 375.1573. HPLC demonstrated >95% purity, retention times (mobile phase, min): 64, (A) 22.69; (B) 23.63; 65, (A) 23.58; (B) 30.18.

Biology.

Binding experiments were carried out using 125I-ABOPX15 for binding to recombinant human or rat A2B receptors overexpressed in HEK-293 cells (Tables 1 and 3). The xanthines examined included those substituted at the 1-position alone (3–8), the 3-position alone (2b), the 1- and 3-positions (2a and 9–17), the 1-, 3-, and 7-positions (18–36), the 1- and 8-positions (37), the 1-, 3-, and 8-positions (38–62), and the 1-, 3-, 7-, and 8-positions (63–65). At the 8-position, cycloalkyl or aryl substituents were included. For selected derivatives, binding to membranes expressing rat A1 and A2A adenosine receptors as an indication of rat A2B selectivity was also carried out (Table 3).

Table 3.

Affinities of Xanthine Derivatives in Radioligand Binding Assays at Rat A1 and A2A Receptors and Selected Compounds at Other Subtypesa–d

| Ki (nM) | Ki ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | rA1a | rA2Ab | rA2Bc | rA1/rA2B | rA2A/rA2B |

| 1 | 16.8 ± 3.6f | 612 ± 287f | 12.8 ± 1.1 | 1.3 | 48 |

| 2a | 6920 ± 160f | 6700 ± 320f | 15 100 ± 2700 | 0.46 | 0.44 |

| 3 | 3310 ± 580 | < 10% (10−5) | 1880 ± 190 | 1.8 | >10 |

| 4 | 12 700 ± 5600 | <10% (10−5) | |||

| 5e | 24 300 ± 4300 | <10% (10−5) | |||

| 6 | 8890 ± 1090 | <10% (10−5) | |||

| 7 | 37 600 ± 8900 | <10% (10−5) | |||

| 8 | 5570 ± 760 | <10% (10−4) | |||

| 13 | 24 700 ± 8100 | 9780 ± 220 | |||

| 14ae | 5830 ± 250 | 33 600 ± 7700 | 2150 ± 260 | 2.7 | 16 |

| 14b | 1660 ± 620 | 3190 ± 1970 | 10 200 ± 1500 | 0.16 | 0.31 |

| 14ce | 27 600 ± 3900 | <10% (10−4) | 5530 ± 610 | 5.0 | >20 |

| 14d | 24 400 ± 4800 | <10% (10−4) | 15 300 ± 2000 | 1.6 | >10 |

| 16 | 2170 ± 940 | <10% (10−4) | |||

| 19a | 15 200 ± 1100 | 4230 ± 1580 | 5390 ± 780 | 2.8 | 0.78 |

| 19b | 23 600 ± 3900 | <10% (10−4) | 14 200 ± 100 | 1.7 | >10 |

| 19c | 17 700 ± 3700 | 33 300 ± 4300 | 18 700 ± 500 | 0.95 | 1.8 |

| 37 | 7.68 ± 1.46 | ||||

| 38 | 1.0 | 500 | 186 ± 5 | 0.005 | 3 |

| 51e | 302 ± 49 | 1920 ± 400 | 174 ± 35 | 1.7 | 11 |

| 54 | 39.0 ± 5.2 | <10% (10−5) | |||

| 55 | 220 ± 11 | 107 ± 10 | |||

| 56 | 7.46 ± 0.58 | 17 300 ± 6500 | |||

| 57 | 97.7 ± 2.7 | 5500 ± 760 | |||

| 58 | 30.3 ± 3.5 | 1340 ± 680 | |||

| 59 | 39.2 ± 10.8 | <10% (10−5) | |||

| 62 | 757 ± 109 | 2720 ± 470 | |||

| 63 | < 10% (10−5) | 23 500 ± 9800 | |||

| 64e | 35 ± 4% (10−5) | 3570 ± 1360 | 1700 ± 90 | >6 | 2.1 |

| 65e | 1660 ± 130 | 16 700 ± 4300 | 3360 ± 530 | 0.49 | 5.0 |

Displacement of specific [3H]R-PIA binding in rat brain membranes in HEK-293 cells, expressed as Ki ± SEM or percent displacement at the indicated concentration (n = 3–5).

Displacement of specific [3H]CGS 21680 binding in rat striatal membranes, expressed as Ki ± SEM or percent displacement at the indicated concentration (n = 3–5).

Rat A2B receptor expressed in HEK cells, using [125I]I-ABOPX as radioligand.

Human A3 receptor, Ki ± SEM (μM), using [125I]I-AB-MECA as radioligand: 3, 2.37 ± 0.08; 4, 3.08 ± 0.43; 5, 16.1 ± 2.9; 6, 4.61 ± 1.26; 7, 7.51 ± 1.64; 8, 0.639 ± 0.158; 14a, 10.9; 14b, 4.44 ± 0.89; 14c, 6.88 ± 0.47; 14d, 8.65 ± 2.73.

5, MRS 1973; 7, MRS 1975; 14a, MRS 1980; 14c, MRS 3005; 51, MRS 1916; 64, MRS 3000; 65, MRS 1995.

Enprofylline (3-propylxanthine 2b) was previously identified as being roughly 1 order of magnitude selective for the human A2B vs human A1 and A2A receptors.13 Surprisingly, the A2B affinity of the enprofylline isomer (1-propylxanthine 3) was 13-fold greater than enprofylline itself. Another monosubstitution was examined at N-1: propargyl, allyl, and n-butyl analogues 4–6 displayed similar affinity with Ki values (equilibrium inhibition constant) of approximately 0.5 μM, and even the more bulky substitutents, 2-phenylethyl 7 and cyclopentyl 8, were relatively potent with Ki values of 0.4 and 1.0 μM, respectively.

Symmetrical 1,3-substitution of xanthine with methyl 2a, ethyl 9, n-Pr 10, or allyl 11 resulted in Ki values of roughly 1 μM at A2B receptors, while the 1,3-di-n-hexyl derivative 12 was less potent. Among asymmetrically substituted xanthines, the 1-ethyl-3-methyl derivative 13 was equipotent to the 1,3-diethyl analogue 9 and elongation at the 1-position, as in 16, did not have a significant effect. The 1-propargyl-3-methyl derivative 14a was equipotent to the 1-propargyl derivative 4. Other 1-position substitutions were included (14b–d) and studied in binding (Table 3). Branched alkyl chains, in 15 and 17, reduced affinity of A2B binding. A comparison of 6 and 16 indicated that addition of a 3-ethyl group reduced affinity 4-fold.

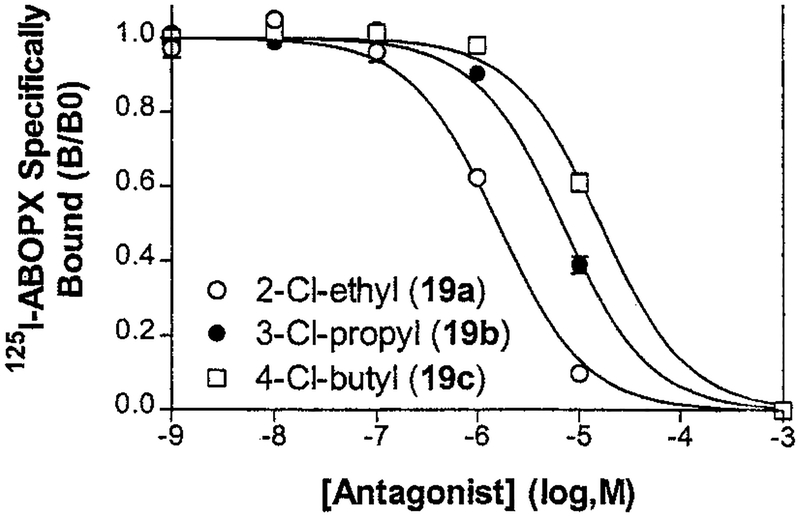

Most N-7 substituents did not enhance affinity of alkylxanthines over hydrogen at this position. For example, theophylline 2a and caffeine 18 were equipotent with Ki values of approximately 10 μM for the human A2B receptor. Most other 7-position substitutions of theophylline examined, i.e., 20–27, including charged and heteroatom substitution, produced Ki values of 10–20 μM. The notable exception to this pattern was 2-chloroethyltheophylline 19a (Ki value of 1.4 μM), which displayed a 7.5-fold greater affinity than caffeine. Homologues of 19a were also prepared and studied in binding (Table 3). As illustrated in Figure 1, the potency order of 7-substituted compounds was 2-Cl-ethyl 19a > 3-Cl-propyl 19b > 4-Cl-butyl 19c. A 7-methyl group slightly reduced the affinity of 1,3-diallylxanthine (28 vs 11). Among caffeine analogues in which the 1-substituent was modified, including charged and heteroatom substitution in 29-35, some variation in affinity was observed (Ki values of 4–21 μM), with the 1-propargyl analogue 29 as the most potent. The relatively high affinity of pentoxifylline 35 (Ki) 5.2 μM) is notable since this compound is used therapeutically to treat intermittent claudication. An isomer 36 was less potent than 29.

Figure 1.

Competition by 7-substituted xanthines for 125I-ABOPX binding to recombinant human A2B receptors. The indicated antagonists (see Table 1) were incubated to equilibrium (2 h) in 100 μL with radioligand (0.7 nM 125I-ABOPX) and human HEK-A2B cell membranes (25 μg of membrane protein). Each point is the mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations. Where not shown, the SEM is smaller than the symbol. Ki values derived from triplicate experiments are summarized in Table 1.

For the 8-cyclopentyl analogues 37 and 38, the absence of a 3-alkyl group slightly increased affinity. An 8-phenyl substituent, well-explored as a means of enhancing affinity at A1 and A2A receptors,19–21 generally enhanced affinity at the human A2B receptor by roughly 20-fold. 8-Phenyltheophylline 39 (Ki value of 415 nM) displayed a 22-fold greater human A2B receptor affinity than theophylline 2a. Substitution of the 8-phenyl ring indicated that an electron-rich ring was preferred in receptor binding. The rank order of potency of substitution at the 8-aryl ring in theophylline analogues 39–47 was 4-hydroxy > 4-dimethylamino > 4-methoxy > 4-sulfo > 3-carboxy and 4-nitro > 2-carboxy and 2,4-dinitro.

Homologation of 1,3-dialkyl groups in 8-phenylxanthines enhanced affinity, by 22-fold in the case of 1,3-dipropyl analogue 49 in comparison to 39. As with 8-H xanthines, a 1-allyl substitutent greatly increased affinity at the A2B receptor in the 8-aryl series. Thus, 1-allyl-3-methyl-8-phenylxanthine 51 displayed a Ki value of 37 nM. Branched substitution, in 52 as before, greatly decreased affinity. Phenyl ring-substituted analogues of 49 were also tested: The electron-withdrawing 2,6-difluoro and 4-chloro groups on the 8-aromatic ring, in 53 and 60, reduced affinity. Various di- and trisubstituted phenyl rings, containing electron-donating groups, displayed considerable affinity but not exceeding that of 49. The functionalized congener XCC (xanthine carboxylic congener, 8-[4-[(carboxymethyl)oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropylxanthine, 61), which served as the basis of A2B receptor-selective amide derivatives such as 1,10 was nearly as potent as 49.

The 7-(2-chloroethyl) group of 65 decreased the affinity of compound 49 by 36-fold to a Ki value of 690 nM. However, in comparison to the 7-methyl modification of 8-phenylxanthines, this group increased affinity. Compound 64, the 7-(2-chloroethyl) derivative of the 8-phenylxanthine derivative 63, displayed a 37-fold greater affinity at human A2B receptors.

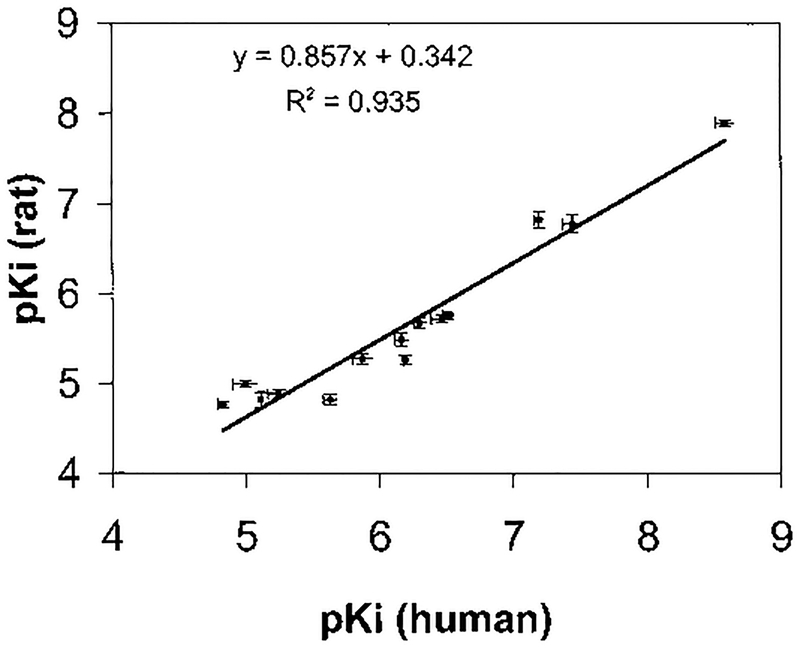

Selected compounds were tested in binding experiments at rat A2B receptors (Table 3). A close correlation between relative potencies at human and rat A2B receptors was found (Figure 2). Affinities were usually higher by 2–9-fold at the human vs the rat A2B receptor, with more pronounced differences observed for the more potent compounds. Compound 14c, a 1-phenylethyl derivative, showed slight A2B receptor selectivity in the rat. The reference compound 1 was still highly potent at the rat A2B receptor, with a Ki value of 12.8 nM, although not selective for A2B vs A1 receptors in the rat. Several other compounds were selective for A2B vs A2A but not A1 receptors in the rat: 3, 14a, 14d, 19b, and 51. Selected compounds were also tested at human A3 receptors (Table 3, footnote e), and most were found to be approximately an order of magnitude more selective for human A2B vs A3 receptors, except compound 8, which was equipotent at the two subtypes.

Figure 2.

Correlation in the affinities of various xanthines for binding to human and rat A2B adenosine receptors. The pKi values of compounds that were evaluated for binding to rat and human receptors (Table 2) are plotted and fit by linear regression.

Discussion

Theophylline 2a is widely used as an antiasthmatic drug, although its mechanism of action is uncertain. The related xanthine, enprofylline13,14 2b, which is also therapeutically efficacious in the treatment of asthma, was earlier thought to act through a nonadenosine receptor-mediated mechanism due to its low affinity at A1 and A2A receptors. However, the discovery that enprofylline has greater than anticipated affinity and slight selectivity at the A2B subtype13 supports the hypothesis that A2B receptor antagonism may contribute to antiasthmatic activity of xanthines.12,26,27 This hypothesis was strengthened by functional effects of A2B receptor activation observed in mast cells of dog and human.8,12,28 Thus, potent and/or selective A2B receptor antagonists may provide new therapeutic agents.

The SAR of xanthines in binding to A2B adenosine receptors was investigated in the present study. Substitution at the 1-position by a group larger than at the 3-position (H or Me) favored affinity at the A2B receptor. The affinity of xanthines in binding to the human A2B receptor was enhanced by substitution with propyl, butyl, allyl, propargyl, or 2-phenylethyl groups at N-1, while hydrogen or methyl at N-3 favored affinity at this subtype.

A 7-(2-chloroethyl) substituent strikingly favored A2B receptor selectivity. Most N-7 substituents did not enhance affinity over hydrogen, except for 2-chloroethyl, which enhanced the human A2B receptor affinity of theophylline by 6.5-fold. Thus, 7-(2-chloroethyl)theophylline displayed a Ki value of 800 nM. Previously, 7-(2-chloroethyl) theophylline was noted to be slightly selective for adenosine A2A vs A1 receptors.29 At the A2B receptor, the effects of the 7-(2-chloroethyl) group were compatible with the enhancement produced by 8-aryl substitution. For example, the affinity of an 8-aryl-7-chloroethyl analogue 64 was intermediate between those of the corresponding 7-H and 7-methyl analogues. Compound 64 was roughly 35-fold more potent at the human A2B receptor than the 7-methyl analogue 63 and 8-fold less potent than the 7-H analogue, 51.

An 8-phenyl substituent, well-explored as a means of enhancing affinity at A1 and A2A receptors,19–24 enhanced affinity at A2B receptors by roughly 20-fold. The detail in the present study concerning 8-aryl ring substitution and compatibility with other xanthine substituents greatly extended previous findings.10,14 As for simpler xanthines, even in the 8-phenyl series, a larger alkyl group at the 1-position than at the 3-position favored affinity at the A2B receptor. This was illustrated by 1-allyl-3-methyl-8-phenylxanthine, 51, which displayed a Ki value of 37 nM at A2B receptors. Substitution of the 8-phenyl ring indicated that an electron-rich ring (e.g., 4-hydroxy substitution, 41) was preferred in receptor binding. Consistent with this finding, nitro and other electron-withdrawing substituents greatly reduced affinity.

The initial screen of A2B receptor affinity in the present study utilized the human subtype, and selected compounds were also evaluated at rat A2B receptors. We found uniformly higher affinity of substituted xanthines for human than for rat A2B adenosine receptors, but these differences were consistently less than 10-fold. Compounds having various degrees of selectivity for rat A2B receptors were 3–7 (1-substitituted xanthines), 14a–d (1-substitituted theophyllines), 51 (1-allyl-3-methyl-8-phenylxanthine), and 64 (1-allyl-7-chloroethyl-3-methyl-8-phenylxanthine). The 1-phenylethyl group appeared to enhance A2B receptor selectivity in the rat.

Selectivity for the human A2B receptor has been easier to achieve than selectivity for the rat homologue, mainly due to the large species differences at A1 and A2A receptors.10 To further define the selectivity of A2B receptor antagonists, additional characterization at receptor homologues of various species will be needed.

In conclusion, we have identified new leads for the design of xanthine derivatives as selective antagonists of the A2B receptor, including asymmetric substitution at the 1- and 3-positions, 7-haloalkyl groups, and 8-aryl ring substitution patterns. Furthermore, the affinities at rat and human A2B receptors have been compared. Optimal combinations of substituents on the 1-, 3-, 7-, and 8-positions of xanthines may lead to more potent and selective antagonists. Such selective compounds will aid in the elucidation of the physiological role of this receptor and possibly lead to therapeutically useful agents for treating asthma, diabetes, and other diseases.6,10,30,31

Experimental Section

Synthetic Methods.

1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were obtained with a Varian Gemini-300 spectrometer using CDCl3 or DMSO-d6 as solvent. The chemical shifts are expressed as parts per million (ppm) downfield from tetramethylsilane or as relative ppm from CDCl3 (7.27 ppm) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (2.5 ppm). FAB (fast atom bombardment) mass spectrometry was performed with a JEOL SX102 spectrometer using 6-kV Xe atoms. CI-NH3 (chemical ionization) mass spectra were carried out with a Finnigan 4600 mass spectrometer. Elemental analysis (±0.4% acceptable) was performed by Atlantic Microlab Inc. (Norcross, GA). All melting points were determined with a Unimelt capillary melting point apparatus (Arthur H. Thomas Co., PA) and were uncorrected. All xanthine derivatives were homogeneous as judged using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) (MK6F silica, 0.25 mm, glass backed; Whatman, Clifton, NJ). Where needed, determinations of purity were performed with a Hewlett-Packard 1090 highperformance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system using an SMT OD-5–60 C18 analytical column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, Separation Methods Technologies, Inc., Newark, DE) in two different linear gradient solvent systems. One solvent system (A) was 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate buffer:CH3CN in ratios of 80:20 to 20:80 in 30 min with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The other (B) was H2O:CH3OH in ratios of 60:40 to 10:90 in 30 min, 10:90 after 30 min, with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Peaks were detected by UV absorption (250 nm) using a diode array detector.

6-Amino-1-methyl-3-benzyl-1H-pyrimidine-2,4-dione (66b).

To a suspension of 6-amino-1-methyluracil (706 mg, 5 mmol) in methanol (15 mL) was added 10% aqueous NaOH solution (2 mL, 5 mmol) and benzyl bromide (0.65 mL, 5.5 mmol). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 3 h and quenched by the addition of saturated NH4Cl solution. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the residue was diluted with chloroform (50 mL). The organic phase was washed with water and brine and dried over sodium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (silica, chloroform:methanol = 10:1) to give 97 mg of 66b (33%, based on recovered starting material) as a white foaming solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 3.33 (s, 3H), 5.00 (s, 1H), 5.08 (s, 2H), 7.23–7.42 (m, 5H). MS (positive ion FAB): 232 [M + H]+.

6-Amino-1-methyl-5-nitroso-3-benzyl-1H-pyrimidine-2,4-dione (67b).

Compound 66b (53 mg, 0.23 mmol) was dissolved in a mixed solvent of water (1 mL), acetic acid (0.2 mL), and 6 N HCl (0.05 mL) and treated with NaNO2 (24 mg, 0.35 mmol) in small portions over a period of 10 min. The mixture was filtered, and the filter cake was washed with water to afford 67b (30 mg, 50%) as a violet solid. 1H NMR(DMSO-d6): δ 3.25 (s, 3H), 5.10 (s, 2H), 7.23–7.40 (m, 5H). MS (positive ion FAB): 261 [M + H]+.

1-Benzyl-3-methylxanthine (14b).

Sodium hydrosulfite (120 mg, 0.69 mmol) was added in small portions to a suspension of 67b (30 mg, 0.12 mmol) in ethyl acetate (4 mL) and water (2 mL), until the violet color disappeared. The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with brine and dried over sodium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure to dryness. The crude product was suspended in trimethylorthoformate (2 mL) and refluxed for 2 h. Trimethylorthoformate was removed by a nitrogen stream, and the residue was purified by preparative TLC (chloroform:methanol = 10:1). The solid was recrystallized from ethyl acetate/hexane to furnish xanthine 14b (13 mg, 44%) as a white solid having a mp 224–226 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 3.65 (s, 3H), 5.28 (s, 2H), 7.27–7.35 (m, 3H) 7.49 (d, 2H, J = 6.6 Hz), 7.73 (s, 1H), 11.93 (bs, 1H). MS (positive ion FAB): 257 [M + H]+.

6-Amino-1-methyl-3-phenethyl-1H-pyrimidine-2,4-di-one (66c).

Compound 66c was prepared by the procedure described for 66b, except using ethanol as solvent, instead of methanol, and obtained in 21% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.91 (m, 2H), 3.42 (s, 3H), 4.12 (m, 2H), 4.56 (bs, 2H), 5.00 (s, 1H),7.20–7.31 (m, 5H). MS (positive ion FAB): 246 [M + H]+.

6-Amino-1-methyl-5-nitroso-3-phenethyl-1H-pyrimidine-2,4-dione (67c).

Compound 67c was prepared by the procedure described for 67b in 51% yield. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 2.88 (t, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz), 3.26 (s, 3H), 4.10 (t, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz),7.20–7.38 (m, 5H). MS (positive ion FAB): 275 [M + H]+.

3-Methyl-1-(2-phenylethyl)xanthine (14c).

Compound 14c was prepared by the procedure described for 14b in 32% yield; mp 240–243 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.97 (m, 2H), 3.66 (s, 3H), 4.29 (m, 2H), 7.22–7.29 (m, 2H) 7.32 (d, 3H, J =4.4 Hz), 7.78 (s, 1H), 11.45 (bs, 1H). MS (positive ion FAB): 271 [M + H]+.

6-Amino-1-methyl-3-(3-phenyl-propyl)-1H-pyrimidine-2,4-dione (66d).

Compound 66d was prepared by the procedure described for 66c in 45% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.97 (m, 2H), 2.68 (t, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 3.39 (s, 3H), 3.97 (t, 2H, J = 7.4 Hz), 4.45 (bs, 2H), 4.97 (s, 1H), 7.10–7.28 (m, 5H). MS (positive ion FAB): 260 [M + H]+.

6-Amino-1-methyl-5-nitroso-3-(3-phenyl-propyl)-1H-pyrimidine-2,4-dione (67d).

Compound 67d was prepared by the procedure described for 67b in 78% yield. 1H NMR(DMSO-d6): δ 1.91 (m, 2H), 2.66 (t, 2H, J = 7.7 Hz), 3.22 (s, 3H), 3.95 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.11–7.30 (m, 5H). MS (CI/NH3): 289 [M + H]+

3-Methyl-1-(3-phenylpropyl)xanthine (14d).

Compound 14d was prepared by the procedure described for 14b in 60% yield; mp 176–180 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.06 (quintet, 2H, J = 7.4 Hz), 2.75 (t, 2H, J = 7.4 Hz), 3.63 (s, 3H), 4.14 (t, 2H, J = 7.4 Hz), 7.12–7.30 (m, 5H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 12.28 (bs, 1H). MS (positive ion FAB): 285 [M + H]+.

7-(3-Chloropropyl)theophylline (19b).

Sodium hydride (24 mg, 60% in mineral oil, 0.61 mmol) was added to a solution of theophylline (100 mg, 0.56 mmol) in DMF (2 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. 1-Bromo-3-chloropropane (0.07 mL, 0.70 mmol) was then added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h, and the solvent was removed by a nitrogen stream. The residue was purified using preparative TLC (ethyl acetate:hexane:methanol = 10:10:1) to give 19b (126 mg, 88%) as a white solid. The solid was recrystallized from ethyl acetate/n-hexane; mp 1223–124 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.39 (m, 2H), 3.42 (s, 3H), 3.50 (t, 2H, J = 5.9 Hz), 3.61 (s, 3H), 4.49 (t, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz), 7.62 (s, 1H). MS (positive ion FAB): 257 [M + H]+.

7-(4-Chlorobutyl)theophylline (19c).

Compound 19c was prepared by the procedure described for 19b in 95% yield; mp 115–117 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.81 (m, 2H), 2.07 (m, 2H), 3.42 (s, 3H), 3.57 (t, 2H, J = 6.3 Hz), 3.60 (s, 3H), 4.35 (t, 2H, J = 7.1 Hz), 7.56 (s, 1H). MS (positive ion FAB): 271 [M + H]+.

1-Allyl-7-chloroethyl-3-methyl-8-phenylxanthine (64).

Sodium hydride (10 mg, 60% in mineral oil, 0.25 mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of 1-allyl-3-methyl-8-phenylxan-thine 5136 (6 mg, 0.02 mmol) in DMF (1 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. 1,2-Dichloroethane (0.05 mL, 0.6 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 36 h. The solvent was removed by a nitrogen stream. The residue was purified using preparative TLC (dichloromethane:2-propanol = 100:1) to give 64 (4.8 mg, 70%) as a white solid; mp 130–133 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): ä 3.66 (s, 3H), 3.94 (t, 2H, J = 6.0 Hz) 4.66 (t, 2H, J = 6.3 Hz) 4.68 (d, 2H, J = 5.5 Hz) 5.22 (dd, 1H, J = 10.2, 1.1 Hz) 5.31 (dd, 1H, J = 17.3, 1.1 Hz) 5.96 (m, 1H) 7.54–7.56 (m, 3H) 7.64–7.68 (m, 2H). High-resolution MS (positive ion FAB) calcd for C17H18ClN4O2 [M + H]+, 345.1118; found, 345.1110. HPLC indicated 99% purity (retention times (min): A, 22.7; B, 23.6).

7-Chloroethyl-1,3-dipropyl-8-phenylxanthine (65).

To a solution of 1,3-dipropyl-8-phenylxanthine 4925 (13 mg, 0.042 mmol) in DMF (2 mL) was added NaH (18 mg, 60% in mineral oil, 0.45 mmol), and the reaction mixture was stirred for 10 min at room temperature. 1,2-Dichloroethane (0.10 mL, 1.27 mmol) was added dropwise, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 48 h. The solvent was removed by a nitrogen stream. The residue was purified using preparative TLC (dichloromethane:2-propanol = 100:1) to give 65 (5.0 mg, 32%) as a white solid; mp 128–132 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.09 (t, 3H, J = 7.4 Hz), 1.10 (t, 3H, J = 7.7 Hz), 1.82 (m, 2H), 1.95 (m, 2H), 4.06 (t, 2H, J = 6.3 Hz), 4.11 (dd, 2H, J = 7.4, 7.7 Hz), 4.23 (dd, 2H, J = 7.7, 7.4 Hz), 4.74 (t, 2H, J = 6.2 Hz), 7.64–7.66 (m, 3H), 7.74–7.77 (m, 2H). High-resolution MS (positive ion FAB) calcd for C19H24ClN4O2 [M + H]+, 375.1588; found, 375.1573. HPLC indicated 96% purity (retention times (min): A, 23.6; B, 30.2).

Pharmacological Methods. Cloning of A2B Receptor.

The rat A2B receptor was cloned by Dr. Eric Yuan-Ji Day (University of Virginia) by the following method: Sprague–Dawley rats were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital. The urinary bladders were removed and stored in RNALater (Qiagen). mRNA was extracted from rat bladder tissue using a Qiagen mRNA extraction kit. The rat A2B receptor was amplified by RT-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the forward primer GGCCATGCAGCTAGAGACGCAGGAC and reverse primer TAGGTCACAAGCTCAGACTGA and then cloned into TOPO2.1 and confirmed by sequencing. The confirmed PCR product was then subcloned in a pDouble-Trouble vector using the restriction enzyme sites for HindIII and ECoRV.

Stable Transfection.

HEK-293 cells were grown in DMEM/F12 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin to 50% confluence in six well dishes. Cells were transfected with 2 μg of plasmid DNA and 5 μL of lipofectamine in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (GibcoBRL). Transfected cells were grown for 48 h prior to selection by the addition of 1 mg/mL G418 in the medium. Resistant colonies were isolated and screened using radioligand binding with 125I-ABOPX. Clonal lines with high specific binding were expanded and maintained in 0.5 mg/mL G418. Several clones with expression levels of approximately 20 000 fmol/mg were preserved. The average KD for 125I-ABOPX for the rat A2B receptor was determined to be 40.9 nM (SEM = 4.4, n = 7).

Binding Assays.

Membranes from HEK-293 cells stably expressing the human or rat A2B receptor were used for competition binding assays with 125I-ABOPX (2200 Ci/mmol).10,32 Radioligand binding experiments were performed in triplicate with 20–25 μg of membrane protein in a total volume of 0.1 mL of HE buffer (10 mM HEPES and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) supplemented with 1 U/mL adenosine deaminase and 5 mM MgCl2. Nonspecific binding was measured in the presence of 100 μM NECA. Xanthine derivatives for competition assays were diluted in HE buffer with 10% DMSO. The incubation time was 3 h at 21 °C. Competition experiments were carried out using between 0.5 and 1.0 nM 125I-ABOPX. Membranes were filtered on Whatman GF/C filters using a Brandel cell harvester (Gaithersburg, MD) and washed three times during 15–20 s with ice-cold buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4). Ki values for different compounds were derived from IC50 values as described, assuming a KD value for 125I-ABOPX of 36 nM at the human A2B receptor. Data from replicate experiments were tabulated as means ± SEM. Nonspecific binding, measured in the presence of 100 μM NECA (RBI-Sigma, St. Louis, MO), was 25% of total binding. All nonradioactive compounds were initially dissolved in DMSO and diluted with buffer to the final concentration, with the amount of DMSO in the final assay tubes consistently ≤0.5%.

For competition experiments, at least six different concentrations of competitor, spanning 3 orders of magnitude adjusted appropriately for the IC50 of each compound, were used. IC50 values, calculated with the nonlinear regression method implemented in the Prism program (GraphPAD, San Diego, CA), were converted to apparent Ki values.33 Equilibrium binding competition experiments at rat A1, rat A2A, and human A3 adenosine receptors were carried out as previously reported.34–36

Acknowledgment.

We thank Dr. John Daly (NID-DK) for helpful discussions and for the gift of xanthine derivatives.

References

- (1).Linden J; Jacobson KA Molecular biology of recombinant adenosine receptors In Cardiovascular Biology of Purines; Burnstock G, Dobson JG, Liang BT, Linden J, Eds.; Kluwer: Norwell, MA, 1998; pp 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Daly JW; Butts-Lamb P; Padgett W Subclasses of adenosine receptors in the central nervous system: interaction with caffeine and related methylxanthines. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol 1983, 3, 69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hide I; Padgett WL; Jacobson KA; Daly JW A2A-Adenosine receptors from rat striatum and rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells: Characterization with radioligand binding and by activation of adenylate cyclase. Mol. Pharmacol 1992, 41, 352–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Feoktistov I; Murray JJ; Biaggioni I Positive modulation of intracellular Ca2+ by adenosine A2B, prostacyclin and prostaglandin E2 receptors via a cholera toxin-sensitive mechanism in human erythroleukemia cells. Mol. Pharmacol 1994, 45, 1160–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Rubino A; Ralevic V; Burnstock G Contribution of P1-(A2B subtype) and P2-purinoceptors to the control of vascular tone in the rat isolated mesenteric arterial bed. Br. J. Pharmacol 1995, 115, 648–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Harada H; Asano O; Hoshino Y; Yoshikawa S; Matsukura M; Kabasawa Y; Niijima J; Kotake Y; Watanabe N; Kawata T; Inoue T; Horizoe T; Yasuda N; Minami H; Nagata K; Murakami M; Nagaoka J; Kobayashi S; Tanaka I; Abe S 2-Alkynyl-8-aryl-9-methyladenines as novel adenosine receptor antagonists: Their synthesis and structure-activity relationships toward hepatic glucose production induced via agonism of the A2B receptor. J. Med. Chem 2001, 44, 170–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Grant MB; Tarnuzzer RW; Caballero S; Ozeck MJ; Davis MI; Spoerri PE; Feoktistov I; Biaggioni I; Shryock JC; Belardinelli L Adenosine receptor activation induces vascular endothelial growth factor in human retinal endothelial cells. Circ. Res 1999, 85, 699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Auchampach JA; Jin J; Wan TC; Caughey GH; Linden J Canine mast cell adenosine receptors: cloning and expression of the A3 receptors and evidence that degranulation is mediated by the A2B receptor. Mol. Pharmacol 1998, 52, 846–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Strohmeier GR; Reppert SM; Lencer WI; Madara JL The A2B adenosine receptor mediates cAMP responses to adenosine receptor agonists in human intestinal epithelia. J. Biol. Chem 1995, 270, 2387–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kim Y-C; Ji X-D; Melman N; Linden J; Jacobson KA Anilide derivatives of an 8-phenylxanthine carboxylic congener are highly potent and selective antagonists at human A2B adenosine receptors. J. Med. Chem 2000, 43, 1165–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).de Zwart M; Vollinga RC; von Frijtag Drabbe Kuünzel JK; Beukers M; Sleegers D; IJzerman AP Potent antagonists for the Human Adenosine A2B receptor. Derivatives of the triazolotriazine adenosine receptor antagonist ZM241385 with high affinity. Drug Dev. Res 1999, 48, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Feoktistov I; Biaggioni I Adenosine A2B Receptors. Pharmacol. Rev 1997, 49, 381–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Robeva AS; Woodard R; Jin X; Gao Z; Bhattacharya S; Taylor HE; Rosin DL; Linden J Molecular characterization of recombinant human adenosine receptors. Drug Dev. Res 1996, 39, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Jacobson KA; IJzerman AP; Linden J 1,3-Dialkylxanthine derivatives having high potency as antagonists at human A2B adenosine receptors. Drug Dev. Res 1999, 47, 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Linden J Molecular characterization of A2A and A2B receptors. Drug Dev. Res 1998, 43, 2. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ji X.-d.; Jacobson KA Use of the triazolotriazine [3H]-ZM241385 as a radioligand at recombinant human A2B adenosine receptors. Drug Des. Discovery 1999, 16, 217–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ji X.-d.; Kim Y-C; Ahern DG; Linden J; Jacobson KA [3H]MRS 1754, a selective antagonist radioligand for A2B adenosine receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol 2001, 61, 657–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Daly JW; Hide I; Muüller CE; Shamim M Caffeine analogues: structure-activity relationships at adenosine receptors. Pharmacology 1991, 42, 309–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Shamim MT; Ukena D; Padgett WL; Daly JW Effects of 8-phenyl and 8-cycloalkyl substituents on the activity of mono-, di-, and trisubstituted alkylxanthines with substitution at the 1-, 3-, and 7-positions. J. Med. Chem 1989, 32, 1231–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Jacobson KA; de la Cruz R; Schulick R; Kiriasis L; Padgett W; Pfleiderer W; Kirk KL; Neumeyer JL; Daly JW 8-Substituted xanthines as antagonists at A1- and A2-adenosine receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol 1988, 37, 3653–3661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Shamim MT; Ukena D; Padgett WL; Hong O; Daly JW 8-Aryl-and 8-cycloalkyl-1,3-dipropylxanthines: further potent and selective antagonists for A1-adenosine receptors. J. Med. Chem 1988, 31, 613–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ukena D; Shamim MT; Padgett WL; Daly JW Analogues of caffeine: antagonists with selectivity for A2 adenosine receptors. Life Sci. 1986, 39, 743–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Daly JW; Padgett WL; Shamim MT Analogues of 1,3-dipropyl-8-phenylxanthine: enhancement of selectivity at A1-adenosine receptors by aryl substituents. J. Med. Chem 1986, 29, 1520–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Daly JW; Padgett WL; Shamim MT Analogues of caffeine and theophylline: effect of structural alterations on affinity at adenosine receptors. J. Med. Chem 1986, 29, 1305–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Muüller CE; Shi D; Manning M Jr.; Daly JW Synthesis of paraxanthine analogues (1,7-disubstituted xanthines) and other xanthines unsubstituted at the 3-position: structure–activity relationships at adenosine receptors. J. Med. Chem 1993, 36, 3341–3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Feoktistov I; Polosa R; Holgate ST; Biaggioni I Adenosine A2B receptors: a novel therapeutic target in asthma? Trends Pharmacol. Sci 1998, 19, 148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Fozard JR; Hannon JP Adenosine receptor ligands: potential as therapeutic agents in asthma and COPD. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther 1999, 12, 111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kirshenbaum AS; Hettinger B; Day Y-J; Gilfillan AM; Metcalfe DD; Kim Y-C; Linden J; Jacobson KA MRS 1754, a Selective A2B Adenosine Receptor Antagonist, Inhibits Degranuilation of Cultured Human but Not Murine Mast Cells. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 57th Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, 2001; abstr. 20000803. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Coffin VL; Spealman RD Psychomotor-stimulant effects of 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine: comparison with caffeine and 7-(2-chloroethyl)theophylline. Eur. J. Pharmacol 1989, 170, 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Cristalli G Synthesis and characterization of potent ligands at human recombinant adenosine receptors. Drug Dev. Res 1998, 43, 23. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Feoktistov I; Goldstein AE; Biaggioni I Cyclic AMP and protein kinase A stimulate Cdc42: role of A2 adenosine receptors in human mast cells. Mol. Pharmacol 2000, 58, 903–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Linden J; Thai T; Figler R; Jin X; Robeva AS Characterization of human A2B adenosine receptors: radioligand binding, western blotting, and coupling to Gq in human embryonic kidney 293 cells and HMC-1 mast cells. Mol. Pharmacol 1999, 56, 705–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Linden J Calculating the dissociation constant of an unlabeled compound from the concentration required to displace radiolabel binding by 50%. J. Cycl. Nucl. Res 1982, 8, 163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Schwabe U; Trost T Characterization of adenosine receptors in rat brain by (–) [3H]N6-phenylisopropyladenosine. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol 1980, 313, 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Jarvis MF; Schutz R; Hutchison AJ; Do E; Sills MA; Williams M [3H]CGS 21680, an A2 selective adenosine receptor agonist directly labels A2 receptors in rat brain tissue. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1989, 251, 888–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Olah ME; Gallo-Rodriguez C; Jacobson KA; Stiles GL [125I]AB-MECA, a high affinity radioligand for the rat A3 adenosine receptor. Mol. Pharmacol 1994, 45, 978–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Daly JW; Padgett WL; Shamim MT; Butts-Lamb P; Waters J 1,3-Dialkyl-8-(p-sulfophenyl)xanthines: Potent water-soluble antagonists for A1- and A2-adenosine receptors. J. Med. Chem 1985, 28, 487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]