Abstract

Background

FIRE-3 compared first-line therapy with FOLFIRI plus either cetuximab or bevacizumab in 592 KRAS exon 2 wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients. The consensus molecular subgroups (CMS) are grouping CRC samples according to their gene-signature in four different subtypes. Relevance of CMS for the treatment of mCRC has yet to be defined.

Patients and Methods

In this exploratory analysis, patients were grouped according to the previously published tumor CRC-CMSs. Objective response rates (ORR) were compared using chi-square test. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) times were compared using Kaplan–Meier estimation, log-rank tests. Hazard ratios (HR) were estimated according to the Cox proportional hazard method.

Results

CMS classification could be determined in 438 out of 514 specimens available from the intent-to-treat (ITT) population (n = 592). Frequencies for the remaining 438 samples were as follows: CMS1 (14%), CMS2 (37%), CMS3 (15%), CMS4 (34%). For the 315 RAS wild-type tumors, frequencies were as follows: CMS1 (12%), CMS2 (41%), CMS3 (11%), CMS4 (34%). CMS distribution in right- versus (vs) left-sided primary tumors was as follows: CMS1 (27% versus 11%), CMS2 (28% versus 45%), CMS3 (10% versus 12%), CMS4 (35% versus 32%). Independent of the treatment, CMS was a strong prognostic factor for ORR (P = 0.051), PFS (P < 0.001), and OS (P < 0.001). Within the RAS wild-type population, OS observed in CMS4 significantly favored FOLFIRI cetuximab over FOLFIRI bevacizumab. In CMS3, OS showed a trend in favor of the cetuximab arm, while OS was comparable in CMS1 and CMS2, independent of targeted therapy.

Conclusions

CMS classification is prognostic for mCRC. Prolonged OS induced by FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab in the FIRE-3 study appears to be driven by CMS3 and CMS4. CMS classification provides deeper insights into the biology to CRC, but at present time has no direct impact on clinical decision-making.

The FIRE-3 (AIO KRK-0306) study had been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00433927.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, CMS, cetuximab, bevacizumab

Key Message

Consensus molecular subgroups (CMS) classification gives a profounder biological insight into metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) carcinogenesis and is of prognostic value. A predictive value to use either bevacizumab or cetuximab in combination with a FOLFIRI backbone cannot established. At present time, CMS classification does not have an impact on clinical decision making in mCRC.

Introduction

The personalized approach to treat metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) as recommended by national (NCCN, German S3-guideline) and international (ESMO/ESMOASIA) [1–4] guidelines is limited to the mutational analyses of RAS (rat sarcoma oncogene) and B-ras associated factor and the analysis of micro-satellite (MSI) status.

Consensus molecular subgroups (CMS) based on gene-expression analysis have gained attention since being published by Guinney et al. [5]. Using gene-expression data from six different cohorts, four different types of colorectal cancer have been defined. CMS1 defined by an upregulation of immune genes is highly associated with microsatellite instability (MSI-h) [6]. CMS2 reflects the canonical pathway of carcinogenesis as defined by the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Genetically chromosomal instable tumors are associated with mutations in APC, p53, and RAS. Overall, CMS2 represents an over-activated epithelial growth factor pathway with higher expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the EGFR-ligands amphiregulin and epiregulin as far as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 overexpression. CMS3 is defined by metabolic dysregulation with higher activity in glutaminolysis and lipidogenesis [7]. Finally, CMS4 is defined by an activated tissue growth factor (TGF)-β pathway and by epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) making it in general more chemo-resistant.

Previous data have been derived for the most from the Union International Contre le Cancer (UICC) stage II and III samples and showed a strong prognostic effect of the four CMS subgroups for both, disease-free survival and overall survival (OS) [5]. The prognostic relevance of CMS in UICC stage IV disease has remained uncertain, as well as its possible predictive effect for the use of EGFR antibodies or vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) antibodies.

The aims of these retrospective, exploratory analyses were as follows: (i) Can the prognostic value of the CMS classification be validated in the metastatic setting of CRC? (ii) Is there a predictive value for the use of the CMS classification for either bevacizumab or cetuximab in the treatment of mCRC? (iii) Do RASmt tumors show a different pattern of CMS distribution when compared with RASwt tumors? (iv) Are there differences in right- versus left-sided tumors with regard to data on CMS classification?

Methods

Patients

Details of the first-line irinotecan (FIRE)-3 study have been published elsewhere [7, 8]. In short, the FIRE-3 study was an open-label randomized phase III study conducted in Germany and Austria testing first-line efficacy of 5-flurouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan (FOLFIRI) plus either cetuximab or bevacizumab in 592 KRAS exon 2 wild-type patients. Primary end point was investigator assessed tumor response rate measured as best overall response rate (ORR) according to RECIST 1.0 criteria [9]. Progression-free survival (PFS) and OS were measured as time-to-event variables from randomization to progression or death (PFS) or death (OS), respectively, using the Kaplan–Meier method to estimate the medians. Patients were censored at the last time of follow up if neither progression nor death had occurred. Per-protocol patients had to be followed up every 3 months after end-of-study treatment.

From 2009 on, only patients with KRAS exon 2 wild-type tumors entered the trial. Before that, 336 patients had been randomized without knowledge of their RAS status. Extended KRAS/NRAS mutational analysis was carried out at the Institute of Pathology of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University (LMU), Munich, as described elsewhere [7]. Using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples of primary tumor tissue gene-expression was analyzed using ALMAC’s Xcel™ gene-expression array at ALMACs own laboratories. CMS groups were determined using the SSP classifiers published in the CMS classifier R package [5]. The CMS calling was done in blinded fashion by a separate institution (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics), which had no access to the clinical data. Tumor samples were tested for MSI-h using the FoundationOne™ (Foundation Medicine, Inc., MA, USA) panel. Sequencing was carried out at FMI Germany GmbH (Penzberg, Germany). All analyses were approved by the ethics committee of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich (#186-15).

Methods statistics

Statistical evaluation was carried out by ClinAssess GmbH using SAS® (SAS Institute, NC, USA) version 9.4. Efficacy data such as ORR were compared between groups using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test or a chi-square test, where appropriate. Time-to-event data were compared using Kaplan–Meier estimation and log-rank tests, while hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated using a Cox proportional hazard regression model.

Results

Details of the different subgroups of RASwt and RASmt populations are shown in the CONSORT diagram (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). In short, 400 patients with a RASwt tumor were included into the analyses. Of those, 315 patients had tumor specimens with measureable gene expression data. For the RASmt population, gene expression could be determined in 123 tumor samples. For allocation to the different CMS cohorts for the different patient cohorts see Table 1. Baseline characteristics for the RASwt population are displayed in Table 2 (RASmt supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online ).

Table 1.

Distribution of CMS cohorts among different patient populations

| Population | CMS1 | CMS2 | CMS3 | CMS4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMS population (n = 438), n (%) | 61 (14) | 164 (37) | 65 (15) | 148 (34) |

| Right-sided tumors (n = 111), n (%) | 24 (22) | 31 (28) | 16 (14) | 40 (36) |

| Left-sided tumors (n = 327), n (%) | 37 (11) | 133 (41) | 49 (15) | 108 (33) |

| RAS wild-type (n = 315), n (%) | 46 (15) | 130 (41) | 36 (11) | 103 (3) |

| RAS wild-type right-sided tumors (n = 71), n (%) | 19 (27) | 20 (28) | 7 (10) | 25 (35) |

| RAS wild-type left-sided tumors (n = 244), n (%) | 27 (11) | 110 (45) | 29 (12) | 78 (32) |

| RAS mutant (n = 123), n (%) | 15 (12) | 34 (28) | 29 (24) | 45 (37) |

| RAS mutant right-sided tumors (n = 40), n (%) | 5 (12) | 11 (28) | 7 (22) | 15 (37) |

| RAS mutant left-sided tumors (n=83), n (%) | 10 (12) | 23 (28) | 20 (24) | 30 (36) |

CMS, consensus molecular subgroup; RAS, rat sarcoma oncogene.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | RASwt population | RASwt CMS population | CMS1 | CMS2 | CMS3 | CMS4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 400 | N = 315 | N = 46 | N = 130 | N = 36 | N = 103 | |

| Sex, male, % | 69.9 | 69.2 | 60.9 | 71.7 | 80.6 | 66.0 |

| Age, median, years | 64 | 64 | 59 | 64 | 66 | 65 |

| Site of primary tumor, % | ||||||

| Colon | 61.3 | 62.9 | 76.1 | 66.2 | 58.3 | 54.4 |

| Rectum | 34.8 | 32.7 | 19.6 | 30.8 | 33.3 | 40.8 |

| Colon + rectum | 3.8 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 8.3 | 4.9 |

| Liver metastasis only, yes, % | 33.2 | 34.9 | 37.0 | 40.9 | 22.2 | 32.0 |

| Primary tumor location, % | ||||||

| Right-sided | 22.8 | 22.5 | 41.3 | 15.4 | 19.4 | 24.3 |

| Left-sided | 77.2 | 77.5 | 58.7 | 84.6 | 80.6 | 75.7 |

| Primary resected, yes, % | 85.3 | 88.6 | 95.7 | 89.8 | 66.7 | 94.2 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, yes, % | 19.0 | 17.5 | 10.9 | 16.2 | 16.7 | 23.3 |

| ECOG, % | ||||||

| 0 | 53.4 | 52.2 | 45.7 | 56.7 | 52.8 | 49.5 |

| 1 | 45.1 | 46.5 | 54.3 | 41.7 | 47.2 | 48.5 |

| 2 | 1.5 | 1.3 | – | 1.6 | – | 1.9 |

| Synchronous, % | ||||||

| Synchronous | 75.7 | 77.5 | 87.0 | 77.7 | 83.3 | 70.9 |

| Metachronous | 24.1 | 22.2 | 10.9 | 22.3 | 16.7 | 29.1 |

| Unknown | 0.3 | 0.3 | 2.2 | |||

CMS, consensus molecular subgroup; RASwt, rat sarcoma wild-type; ECOG, eastern cooperative oncology group performance status.

Most of the baseline characteristics were distributed equally among the four CMS groups. The pattern of CMS distribution was different between RASwt (n = 315) and RASmt tumors (n = 123). While there were comparable frequencies of CMS1 (15% versus 12%) and CMS4 (33% versus 37%), noticeable differences were observed with regard to CMS2 (41% versus 28%) and CMS3 (11% versus 24%). Using a univariate logistic regression model, CMS2 (P = 0.009) and CMS3 (P = 0.002) were significantly associated with RASwt and RASmt status, respectively. This remained significant for the association of RAS mutation and CMS3 (P = 0.046) using a multivariate model (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

As expected, sidedness of primary tumors is reflected by specific patterns of CMS distribution. Right-sided RASwt tumors showed a higher prevalence of CMS1 (27% versus 11%) and a lower prevalence of CMS2 (28% versus 45%) than left-sided RASwt tumors (Table 1). This also led to the observation that only a very low prevalence of CMS1 (20%) was observed in rectal cancer (Table 2). Using a multivariate logistic regression analysis for the baseline characteristics, RAS mutation was associated with right-sided tumors (P = 0.01) and rectum tumors (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

However, comparable frequencies between right- and left-sided tumors were documented for CMS3 (10% versus 12%) and CMS4 (35% versus 32%). In RASmt tumors, by contrast, sidedness had no impact on CMS frequencies (Table 1).

Within the study population of analyzable patients, CMS classification had a significant prognostic value between all groups (P values for both, PFS and OS <0.001). Longest median OS was observed in CMS2 [OS 29.0 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 26.7–31.4 months)], followed by CMS4 [OS 24.8 months (95% CI 22.6–27.1 months)], CMS3 [18.6 months (95% CI 15.4–21.7 months)], and CMS1 [15.9 months (95% CI 11.0–20.8 months)]. PFS followed this ranking (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Within the RASwt population, CMS subtypes were associated with significantly different ORRs (chi-square P = 0.027). When both treatment arms were analyzed together, the highest ORR was observed in CMS2 (ORR 78%), the lowest in CMS1 (ORR 55%). Across all CMS subtypes, ORR was numerically greater in the cetuximab arm. However, levels of statistical significance were reached only in CMS2 and CMS4 (Table 3). Interaction test P-value, using logistic regression was 0.09 for the univariate and 0.91 for the multivariate model within the RASwt population.

Table 3.

Response rates (ORR) according to CMS

| RASwt | CMS1 | P* | CMS2 | P* | CMS3 | P* | CMS4 | P* | Chi-square P | CMS 1–4 | P* | CMS 1–4 left-sided | P* | CMS 1–4 right-sided | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 315) | |||||||||||||||

| FOLFIRI Cet | 61% | 0.54 | 88% | 0.043 | 74% | 0.13 | 76% | 0.049 | 67% | 0.049 | 71% | 0.06 | 52% | 0.81 | |

| FOLFIRI Bev | 50% | 71% | 42% | 55% | 56% | 58% | 47% | ||||||||

| Both arms | 55% | 78% | 61% | 66% | 0.027 | 61% | 65% | 49% | |||||||

| (n = 123) | |||||||||||||||

| FOLFIRI Cet | 40% | 0.58 | 58% | 0.46 | 50% | 0.70 | 40% | 0.054 | 39% | 0.28 | 40% | 0.38 | 40% | 0.75 | |

| FOLFIRI Bev | 67% | 39% | 39% | 74% | 50% | 51% | 47% | ||||||||

| Both arms | 57% | 47% | 44% | 56% | 0.71 | 45% | 46% | 44% | |||||||

| (n = 438) | |||||||||||||||

| FOLFIRI Cet | 54% | 0.59 | 81% | 0.03 | 66% | 0.11 | 63% | 0.73 | 59% | 0.29 | 63% | 0.26 | 47% | >0.99 | |

| FOLFIRI Bev | 55% | 64% | 42% | 60% | 54% | 57% | 47% | ||||||||

| Both arms | 55% | 71% | 55% | 62% | 0.051 | 57% | 60% | 47% | |||||||

CMS, consensus molecular subgroup; P*, two-sided Fisher’s exact test P; Cet, cetuximab; Bev, bevacizumab; RASwt, RAS wild-type.

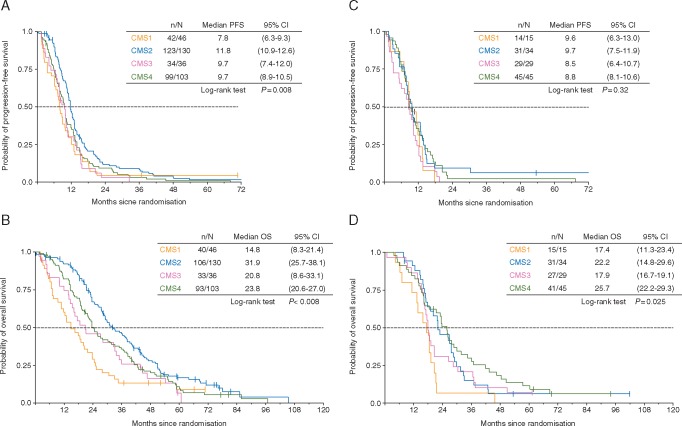

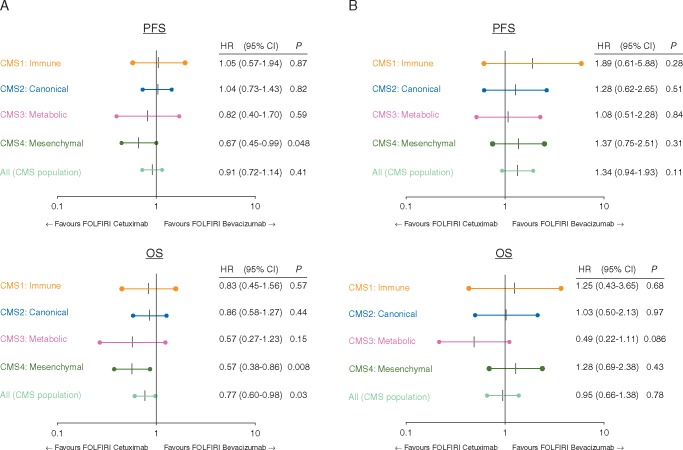

Figure 1 indicates that CMS was associated with differential outcome in patients with RASwt tumors with regard to PFS (P = 0.008) and OS (P < 0.001). The value of CMS with regard to targeted therapy was limited. In RASwt tumors, median OS was numerically longer in all CMS subtypes when treated with cetuximab compared with bevacizumab. This effect reached, however, statistical significance only in CMS4 with regard to PFS (HR 0.67, P = 0.048) and OS (HR 0.57, P = 0.008) (Figure 2). Interaction P value for PFS within the RASwt population was 0.07 using a univariate COX regression model and 0.18 for the multivariate model.

Figure 1.

Survival times according to consensus molecular subgroup (CMS). (A) Progression-free survival (PFS) in rat sarcoma oncogene (RAS) wild-type cases according to CMS. (B) Overall survival (OS) in RAS wild-type cases according to CMS. (C) PFS in rat sarcoma oncogene (RAS) mutant cases according to CMS. (D) Overall survival (OS) in RAS mutant cases according to CMS. n = events occurred; N = number of patients; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Forrest plots: predictive value of consensus molecular subgroup (CMS) with respect to either bevacizumab or cetuximab. (A) Rat sarcoma oncogene (RAS) wild-type cases. (B) RAS mutant cases. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival, HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; P = cox proportional test P.

For median survival times in RASmt within the different treatment groups, see supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online. Again, interaction test was negative within the RASwt population reaching 0.05 for the univariate COX regression model and 0.13 for the multivariate model.

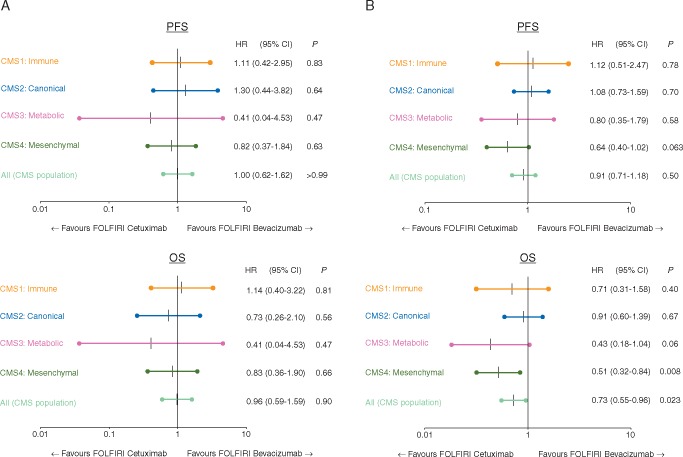

Figure 3 evaluates the predictive value of CMS with regard to the efficacy of bevacizumab or cetuximab in left- versus right-sided tumors. In left-sided RASwt tumors, cetuximab induced longer OS in CMS3 and CMS4, whereas comparable results for cetuximab and bevacizumab were observed in CMS1 and CMS2.

Figure 3.

Forrest plots: predictive value of consensus molecular subgroup (CMS) with respect to either bevacizumab or cetuximab in left- and right-sided rat sarcoma oncogene (RAS) wild-type tumors. (A) (A) Rat sarcoma oncogene (RAS) wild-type right-sided cases. (B) RAS wild-type left-sided cases. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; P, cox proportional test P.

Data on RASmt cases were calculated (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online) but due to the small number of patients within the respective CMS subgroups, no conclusive results were obtained.

When comparing the predictive values for CMS, RAS status, treatment arm, and primary tumor location using multivariate logistic or COX regression tests, respectively, for ORR side of the primary (P = 0.047) and RAS status (P = 0.005) showed significant values. For PFS, only side of the primary was a significant predictor with a P value of 0.0009. RAS status, treatment arm, and primary tumor location were significant predictors of OS with P values of 0.039, 0.049, and <0.0001 respectively.

MSI-h was a rare event (n = 10). The majority of MSI-h cases were CMS1 (8/10), but there was also one CMS3 and CMS4 case each. MSI-h was associated with a shorter median OS versus MSS (18.7 months versus 24.0 months; P = 0.10) and PFS (5.0 versus 10.0 months; P = 0.18), but did not reach the level of statistical significance (data not shown). As numbers were small, the predictive value of MSI-h status was not assessed.

Discussion

Since its first publication, CMS in CRC has triggered multiple analyses. The question remains whether CMS is meaningful in classification of mCRC cases with respect to clinical decisions. The present evaluation therefore set out to evaluate a larger cohort of UICC stage IV mCRC patients treated with either EGFR- or VEGF-A antibodies. CMS-related data presented in this post hoc investigation are exploratory in nature and need to be interpreted accordingly. This specifically also relates to the evaluation of small sample sizes in some subgroups.

Using material from UICC stage IV patients, the frequencies of the single CMS subtypes were comparable to what has been described before [5]. This observation may suggest that all CMS cohorts have a similar ability to progress from UICC stage II/III to the metastatic stage IV. However, analyses of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project-C07, Pan-European Trials in Alimentary traCt Cancer (PETACC)-3, and PETACC-8 trials demonstrate that not all tumors have the same risk of disease recurrence [10–12]. For patients in the adjuvant setting, CMS4 had a higher risk of disease recurrence [11]. Those differences may be attributed to the relatively small number of patients in FIRE-3 when compared with the number of adjuvant trials. Furthermore, the material from which CMS classification has been revealed in this investigation was predominantly derived from primary tumors. This and the selection toward KRAS exon-2- or extended RAS wild-type cases are limitations to our analyses.

Within the FIRE-3 study, the prognostic value of the different CMS subtypes could be confirmed. For both, RASwt (P < 0.001) and RASmt (P = 0.025) tumors, CMS was able to significantly predict survival with CMS1 being the subgroup with worst survival and CMS2 for RASwt and CMS4 for RASmt tumors defining the respective cohorts with the longest survival. This is in line not only with the prognostic relevance of CMS reported before [5] but also with data from the adjuvant PETACC8 study as well as the palliative CALGB80405 study, both presented at ASCO annual meeting in 2017 [11, 13]. While FIRE-3 is the only study with FOLFIRI as the predefined chemotherapeutic backbone, there seems to be no significant [14] difference in the prognostic effect of CMS with regard to FOLFOX or FOLFIRI treatment [14]. This raises the question whether the CMS classification may be used to predict efficacy of either the EGFR antibody cetuximab or the VEGF-A antibody bevacizumab, both in combination with FOLFIRI. As ORR was the primary end point of the FIRE-3 study and ORR is tightly connected to efficacy, CMS2 and CMS4 were able to predict ORR to FOLFIRI plus cetuximab in comparison to FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab (P = 0.043 and 0.049, respectively). For CMS4, this improved tumor response also translated into significantly longer survival times for cetuximab compared with bevacizumab with regard to PFS (HR 0.67, P = 0.048) and OS (HR 0.57, P = 0.008) in RASwt tumors. In CMS3, we observed a strong trend toward longer survival in the cetuximab arm in RASwt (HR 0.57; P = 0.15). It is of interest to note that in the CALGB 80405 study, where 73% of patients had been treated with a 5-fluorouracil-/oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy, only CMS2, but not CMS3 or CMS4 were predictive for the benefit from cetuximab [13]. Reason for this difference may be the use of oxaliplatin rather than irinotecan. As described before, the benefit from oxaliplatin seems to be more pronounced in CMS2 than in CMS1, CMS3, and CMS4 [10]. In a hypothesis-generating paper, it was suggested that the differences observed between CALGB80405 and FIRE-3 may be attributed to the trial-specific sequence of chemotherapy plus targeted therapy [15]. Most of the differences between both studies are probably due to the observation that oxaliplatin is inducing EMT, which may cause fibroblast enrichment decreasing the efficacy of second-line anti-EGFR treatment. Similar effects have also been shown by the UNICANCER PRODIGE18 study, where continuation of bevacizumab beyond progression was associated with a trend toward longer OS when compared with cetuximab in second-line [16].

Another obvious difference to the data presented by the CALGB80405 group was observed with regard to CMS1 and MSI tumors. In CALGB80405, treatment results obtained in CMS1 were significantly in favor of the bevacizumab arm, while cetuximab-treated patients had a markedly worse outcome [13]. This association of CMS1 and poor efficacy of cetuximab has also been observed in the adjuvant PETACC8 trial, where CMS1 patients treated with FOLFOX plus cetuximab had a shorter disease-free survival compared with FOLFOX alone [11]. This observation supports the hypothesis that in CMS1-patients a detrimental effect is induced when oxaliplatin-based therapy is combined with cetuximab. One explanation may be that in fibroblast-rich CMS1, subgroup cetuximab activity is antagonized by interleukin-16A and TGF-β, both factors notably released by oxaliplatin-treated fibroblasts [5, 17].

Looking into the subgroup of left-sided RASwt tumors, which should be treated with an anti-EGFR agent in first-line treatment according to international guidelines [4], the OS benefit induced by cetuximab is mainly derived from CMS3 and CMS4. The large group of CMS2 cases (45% of left-sided RAS wild-type tumors) had no predictive value for the use of FOLFIRI plus either cetuximab or bevacizumab.

For ORR in RASwt tumors, CMS2 and CMS4 were significantly in favor of the use of FOLFIRI plus cetuximab (P = 0.043 and 0.049, respectively). Interestingly, in RASmt CMS4, ORR was in favor of the bevacizumab arm (P = 0.054) pointing out the importance of RAS mutations for CMS4. CMS4 is characterized by an extensive angiogenic pathway activation [5]. While in RASwt tumors, cetuximab seems to be the better antiangiogenic agent than bevacizumab, the reverse was observed in RASmt tumors.

Conclusion

In summary, CMS classification within the FIRE-3 trial could be confirmed to be of significant prognostic value. It was also predictive for outcome in CMS4, favoring FOLFIRI plus cetuximab in RASwt tumors. Although a significantly higher ORR was seen in CMS2 for FOLFIRI plus cetuximab, this did not translate into a difference in PFS or OS when compared with the bevacizumab arm. However, from a clinical standpoint, CMS appear not to be of superior value with regard to the selection of patients optimally treated with either anti-EGFR or anti-VEGF agents. Taken together, CMS classification provides deeper insights into the biology to CRC, but at the present time has no impact on clinical decision making.

Funding

Funding for the clinical study came from Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, and Pfizer GmbH, Germany. Funding for the transcriptome based microarray for gene-expression using Xcel® Array came from ALMAC Ltd, Belfast, UK. Funding for FoundationOne®-based sequencing analysis (MSI) was obtained from Roche Pharma AG, Grenzach, Germany (no grant numbers apply).

Disclosure

SS: got honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: Amgen, Bayer, Lilly, Merck KGaA, MSD, Pierre-Fabre, Sanofi, Servier, Roche, Takeda, Taiho. HJL: got honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: BMS, Merck-Serono, Bayer, Roche. LFvWeikersthal: got honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: Roche, Novartis, Genzyme; AK: got honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: Merck, Roche, Amgen; FK: got honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: Roche, Celgene; MM: got honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: AMGEN, BMS, MSD, Merck-Serono, Lilly, Falk, Pfizer, Roche; DPM: got honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: Merck-Serono, Roche, Servier, Sirtex, BMS, MSD, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lilly; AJ: got honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Boerhinger-Ingelheim, BMS, Roche, Novartis, Merck-Serono; TK: honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: Merck-Serono, Astra-Zeneca, Amgen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche; DA: honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: Merck-Serono, Bayer, Teva; ST: honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: Merck-Serono, Roche, Sanofi, Bayer, MSD, BMS; VH: honoraria for presentations and advisory board role from: Merck-Serono, Roche, Servier, Sirtex, BMS, MSD, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lilly. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.NCCN. NCCN Guidelines Colon Cancer Version 2.2017. 2017.

- 2. Schmiegel W, Buchberger B, Follmann M. et al. S3-leitlinie – kolorektales karzinom. Z Gastroenterol 2017; 55: 1344–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R. et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2016; 27(8): 1386–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yoshino T, Arnold D, Taniguchi H. et al. Pan-Asian adapted ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a JSMO-ESMO initiative endorsed by CSCO, KACO, MOS, SSO and TOS. Ann Oncol 2018; 29(1): 44–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X. et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015; 21(11): 1350–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dienstmann R, Vermeulen L, Guinney J. et al. Consensus molecular subtypes and the evolution of precision medicine in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2017; 17(4): 268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stintzing S, Modest DP, Rossius L. et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a post-hoc analysis of tumour dynamics in the final RAS wild-type subgroup of this randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(10): 1426–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T. et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15(10): 1065–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45(2): 228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Song N, Pogue-Geile KL, Gavin PG. et al. Clinical outcome from oxaliplatin treatment in stage II/III colon cancer according to intrinsic subtypes: secondary analysis of NSABP C-07/NRG oncology randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2016; 2(9): 1162–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marisa L, Aydi M, Balogoun R. et al. Clinical utility of colon cancer molecular subtypes: validation of two main colorectal molecular classifications on the PETACC-8 phase III trial cohort. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 3509. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mooi JK, Wirapati P, Asher R. et al. The prognostic impact of consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) and its predictive effects for bevacizumab benefit in metastatic colorectal cancer: molecular analysis of the AGITG MAX clinical trial. Ann Oncol 2018; 29(11): 2240–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lenz HJ, Ou F-S, Venook A. et al. Impact of consensus molecular subtyping (CMS) on overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): analysis of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 1876–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Okita A, Takahashi S, Ouchi K. et al. Consensus molecular subtypes classification of colorectal cancer as a predictive factor for chemotherapeutic efficacy against metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2018; 9(27): 18698–18711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aderka D, Stintzing S, Heinemann V.. Explaining the unexplainable: discrepancies in results from the CALGB/SWOG 80405 and FIRE-3 studies. Lancet Oncol 2019; 20(5): e274–e283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bennouna J, Hiret S, Bertaut A. et al. Continuation of bevacizumab vs cetuximab plus chemotherapy after first progression in KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: the UNICANCER PRODIGE18 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2019; 5(1): 83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Colangelo T, Polcaro G, Muccillo L. et al. Friend or foe? The tumour microenvironment dilemma in colorectal cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2017; 1867(1): 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.