Abstract

Background

Treatment options are limited for patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (HNSCC) following progression after first-line platinum-based therapy, particularly in Asian countries.

Patients and methods

In this randomised, open-label, phase III trial, we enrolled Asian patients aged ≥18 years, with histologically or cytologically confirmed recurrent/metastatic HNSCC following first-line platinum-based therapy who were not amenable for salvage surgery or radiotherapy, and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0/1. Patients were randomised (2 : 1) to receive oral afatinib (40 mg/day) or intravenous methotrexate (40 mg/m2/week), stratified by ECOG performance status and prior EGFR-targeted antibody therapy. The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS) assessed by an independent central review committee blinded to treatment allocation.

Results

A total of 340 patients were randomised (228 afatinib; 112 methotrexate). After a median follow-up of 6.4 months, afatinib significantly decreased the risk of progression/death by 37% versus methotrexate (hazard ratio 0.63; 95% confidence interval 0.48–0.82; P = 0.0005; median 2.9 versus 2.6 months; landmark analysis at 12 and 24 weeks, 58% versus 41%, 21% versus 9%). Improved PFS was complemented by quality of life benefits. Objective response rate was 28% with afatinib and 13% with methotrexate. There was no significant difference in overall survival. The most common grade ≥3 drug-related adverse events were rash/acne (4% with afatinib versus 0% with methotrexate), diarrhoea (4% versus 0%), fatigue (1% versus 5%), anaemia (<1% versus 5%) and leukopenia (0% versus 5%).

Conclusions

Consistent with the phase III LUX-Head & Neck 1 trial, afatinib significantly improved PFS versus methotrexate, with a manageable safety profile. These results demonstrate the efficacy and feasibility of afatinib as a second-line treatment option for certain patients with recurrent or metastatic HNSCC.

Clinical trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01856478.

Keywords: afatinib, methotrexate, HNSCC, Asian

Key Message

LUX-Head & Neck 3, undertaken in Asia, is the second head-to-head trial comparing afatinib and methotrexate in recurrent/metastatic HNSCC following first-line platinum-based therapy. As with LUX-Head & Neck 1, the trial achieved its primary PFS end point, demonstrating that afatinib is a potential treatment option in this setting. The tolerability profile of afatinib was predictable and manageable.

Introduction

Currently, the most common first-line treatment option for recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is platinum-based chemotherapy, which, in some regions including the United States and European Union, can be combined with the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted monoclonal antibody cetuximab. However, ∼50% of patients relapse after first-line therapy and prognosis for these patients is particularly poor [1]. Second-line treatment options are limited but commonly include methotrexate, taxanes, and re-challenge with platinum-based chemotherapy. Cetuximab monotherapy and, more recently, the immunotherapy agents nivolumab and pembrolizumab are approved in some countries [2], but response rates to these agents as second-line treatment remain low [3−5] and many patients, particularly those in Asian countries, cannot access such treatments. Furthermore, recent data indicate that immunotherapy agents are likely to be increasingly used in the first-line rather than second-line setting [2]. Consequently, alternative second-line treatment options are needed.

The feasibility of targeting the EGFR in HNSCC was first demonstrated with cetuximab [1], and encouraging results have been observed with the oral irreversible ErbB family blocker, afatinib, in a second-line setting. In a phase II study, afatinib demonstrated comparable efficacy to cetuximab as subsequent therapy in patients with recurrent/metastatic HNSCC [3]. In the global, phase III LUX-Head & Neck 1 study, second-line afatinib significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) versus methotrexate in patients with recurrent/metastatic HNSCC progressing on or after platinum-based chemotherapy [hazard ratio (HR) 0.80; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.65–0.98; P = 0.030] [6]. Notable benefit with afatinib versus methotrexate was seen in patients who had not received a prior EGFR-targeted antibody and in those with p16-negative disease.

More than 55% of global HNSCC cases are reported in Asia [7]. Most cases of HNSCC in Asian patients are p16-negative disease, with previous studies reporting that only 21%–25% of cases are human papilloma virus (HPV)-positive [8, 9]. In contrast, rates of 50%–70% are reported in the United States and Europe [10]. Combined with the limited availability of cetuximab and immunotherapy agents, this provides a rationale for the use of afatinib in Asian patients. Here, we compared second-line afatinib and methotrexate in Asian patients with recurrent/metastatic HNSCC.

Methods

LUX-Head & Neck 3 was a randomised, open-label, phase III study done at 53 centres in eight countries (China, India, Korea, Thailand, Egypt, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the Philippines). Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years with histologically/cytologically confirmed recurrent/metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, or larynx, unamenable for salvage surgery or radiotherapy. All patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0/1, adequate organ function, and had documented progressive disease after platinum-based chemotherapy based on investigator’s assessment. Previous treatment with EGFR-targeted antibody therapy (but not EGFR-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors) was allowed. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization. All patients provided written informed consent.

Patients were randomised (2 : 1) to receive oral afatinib (40 mg once daily) or methotrexate (40 mg/m2/week; intravenous bolus injection), stratified by ECOG performance score (0 versus 1) and prior use of EGFR-targeted antibody therapy in the recurrent/metastatic setting (yes versus no) at baseline. Treatment continued until disease progression confirmed by imaging, adverse events (AEs) requiring treatment discontinuation, or other reasons necessitating withdrawal.

The primary end point was PFS, assessed by independent central review blinded to treatment allocation (supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online). Secondary end points included overall survival (OS), objective response rate [ORR, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) version 1.1], health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and safety.

The study was designed to demonstrate a PFS benefit of afatinib over methotrexate. A total of 274 progression/death events were needed to achieve 80% power with a one-sided type-I error α = 0.025, assuming a median PFS of 3.0 months with afatinib and 2.1 months with methotrexate [3, 11]. The study was not powered to detect statistically significant differences in OS. Further details on the methods are provided in the supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01856478.

Results

Between 11 June 2013 and 10 February 2018, 340 patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to receive afatinib (228 patients) or methotrexate (112 patients; supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). All randomised patients (intent-to-treat population) were included in the efficacy analyses; 332 were included in the safety population. Patient baseline demographics and disease characteristics were well balanced between the two treatment arms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics

| Characteristic | Afatinib (n = 228) | Methotrexate (n = 112) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 193 (85) | 99 (88) |

| Female | 35 (15) | 13 (12) |

| Age, years | ||

| Median (range) | 55.5 (28–83) | 58.0 (27–76) |

| <65, n (%) | 197 (86) | 96 (86) |

| ≥65, n (%) | 31 (14) | 16 (14) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Asian | 215 (94) | 107 (96) |

| White | 13 (6) | 5 (4) |

| Region, n (%) | ||

| East Asia | 131 (58) | 78 (70) |

| Other | 97 (42) | 34 (30) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 47 (21) | 24 (21) |

| 1 | 181 (79) | 88 (79) |

| Smoking pack-years, n (%) | ||

| <10 | 107 (47) | 46 (41) |

| ≥10 | 120 (53) | 66 (59) |

| Unknown | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | ||

| ≤7 units/week | 179 (79) | 84 (75) |

| >7 units/week | 49 (21) | 27 (24) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) |

| Primary tumour site, n (%) | ||

| Oral cavity | 115 (50) | 50 (45) |

| Oropharynx | 29 (13) | 18 (16) |

| Hypopharynx | 26 (11) | 17 (15) |

| Larynx | 57 (25) | 27 (24) |

| Other | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Time since first diagnosis, years | ||

| Median (range) | 1.6 (0.2–21.3) | 1.7 (0.2–12.9) |

| <2, n (%) | 149 (65) | 72 (64) |

| ≥2, n (%) | 79 (35) | 40 (36) |

| Localisation of recurrence, n (%) | ||

| Locoregional disease only | 114 (50) | 59 (53) |

| Distant metastases only | 17 (8) | 7 (6) |

| Both | 96 (42) | 46 (41) |

| Unknown | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Metastatic sites, n (%) | ||

| Any | 112 (49) | 51 (46) |

| Non-regional lymph nodes | 50 (22) | 20 (18) |

| Lung | 76 (33) | 39 (35) |

| Liver | 11 (5) | 4 (4) |

| Bone | 8 (4) | 6 (5) |

| Skin | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Other | 10 (4) | 4 (4) |

| p16 status,an (%) | ||

| Positive | 9 (4) | 1 (<1) |

| Negative | 79 (35) | 30 (27) |

| No result available | 140 (61) | 81 (72) |

| Differentiation grade, n (%) | ||

| Well differentiated | 66 (29) | 28 (25) |

| Moderately differentiated | 90 (40) | 41 (37) |

| Poorly differentiated | 32 (14) | 16 (14) |

| Undifferentiated | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Not specified/unknown | 38 (17) | 27 (24) |

| Prior platinum-based therapy for R/M disease, n (%) | ||

| Cisplatin | 171 (75) | 79 (71) |

| Carboplatin | 42 (18) | 23 (21) |

| Cisplatin and carboplatin | 7 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Other | 5 (2) | 7 (6) |

| Prior use of anti-EGFR mAb for R/M disease, n (%)b | 30 (13) | 13 (12) |

| Duration of anti-EGFR mAb for R/M disease, n (%) | ||

| ≤12 weeks | 13 (6) | 4 (4) |

| >12–24 weeks | 9 (4) | 6 (5) |

| >24 weeks | 8 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Prior surgery, n (%) | 176 (77) | 88 (79) |

| Prior anticancer therapy for early-stage or LA disease, n (%) | ||

| RT only | 66 (29) | 43 (38) |

| CRT | 86 (38) | 34 (30) |

| CT alone | 7 (3) | 1 (<1) |

| CT+RT+EGFR-targeted mAb | 7 (3) | 1 (<1) |

| Other | 3 (1) | 1 (<1) |

Based on central test results.

Nine patients received prior nimotuzumab and the remaining patients received cetuximab.

CRT, chemoradiation therapy; CT, chemotherapy; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; LA, locally advanced; mAb, monoclonal antibody; R/M, recurrent or metastatic; RT, radiation therapy.

At data cut-off (19 September 2018, after a median follow-up of 6.4 months), two patients in the afatinib group remained on treatment; all other patients had permanently discontinued treatment, mostly because of disease progression. Ninety-five percent of patients in the afatinib group and 76% of patients in the methotrexate group had received at least 80% of the assigned drug.

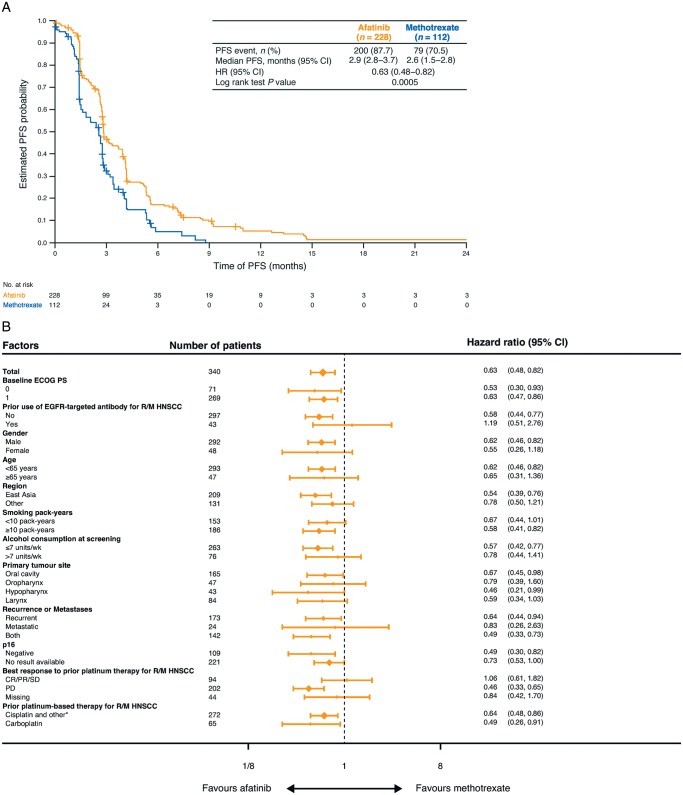

At data cut-off, PFS by independent review was significantly improved with afatinib versus methotrexate (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.48–0.82; P = 0.0005; median 2.9 versus 2.6 months, respectively; Figure 1A). PFS rates were 58% versus 41% at 12 weeks, and 21% versus 9% at 24 weeks. Results were consistent when assessed by investigator review (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online), and across most major prespecified subgroups (Figure 1B). There was no significant difference in OS between the groups (HR 0.88; 95% CI 0.68–1.13; P = 0.32; supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

Survival outcomes. (A) Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free survival assessed by independent review. (B) Pre-specified subgroup analysis of progression-free survival (independent review). CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Group Performance Status; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; R/M, recurrent or metastatic; SD, stable disease. *Cisplatin alone, cisplatin+carboplatin, nedaplatin alone and other.

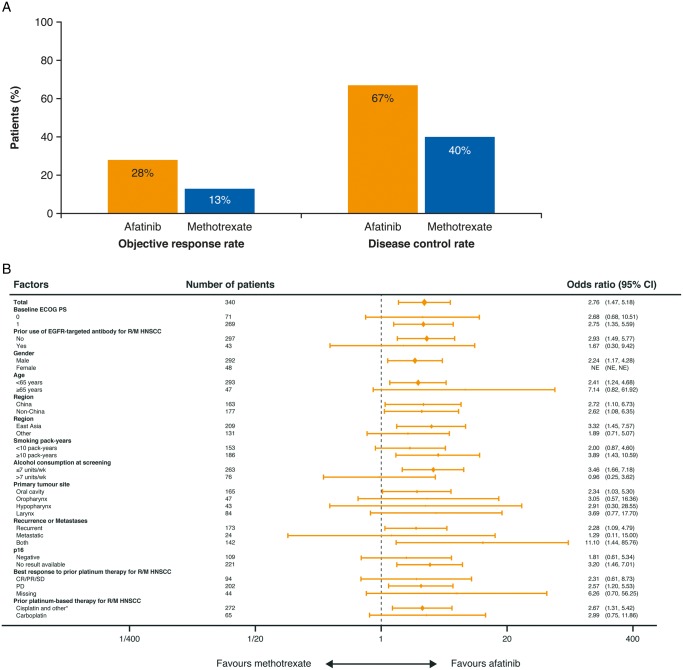

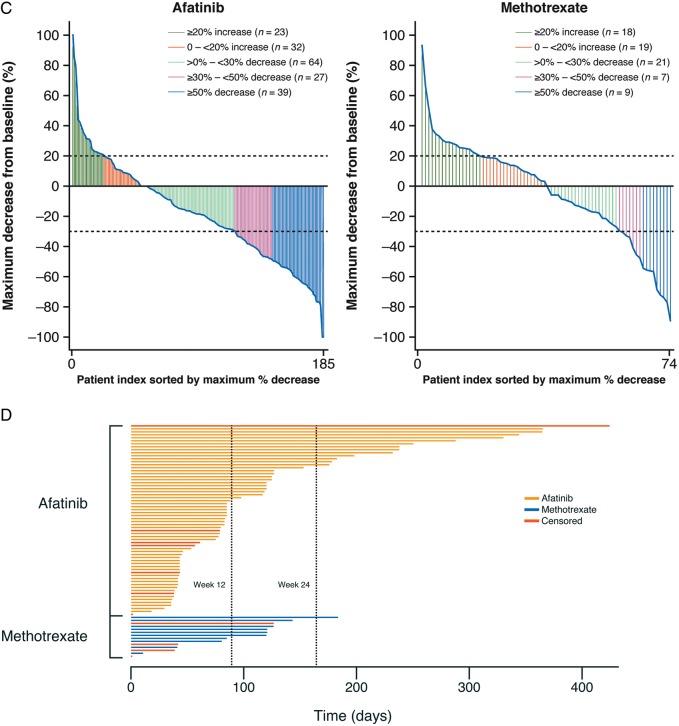

The ORR was 28% with afatinib and 13% with methotrexate [odds ratio (OR) 2.76; 95% CI 1.47–5.18; P = 0.0016; Figure 2A]. Results were consistent across prespecified patient subgroups (Figure 2B). A ≥50% decrease in tumour size was observed in 17% and 8% of patients, respectively (Figure 2C). Median duration of response was 2.8 and 4.0 months with afatinib and methotrexate; 22% and 7% of patients had a response duration of ≥24 months (Figure 2D). 7% and 3% of patients in the afatinib and methotrexate groups, respectively, continued treatment beyond progression.

Figure 2.

Disease control and tumour shrinkage. (A) Objective response rate and disease control rate with afatinib and methotrexate, assessed by independent review. (B) Prespecified subgroup analyses of objective response rate (independent review). (C) Maximum percentage tumour shrinkage in individual patients. (D) Duration of response for individual patients. CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Group Performance Status; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; R/M, recurrent or metastatic; SD, stable disease. *Cisplatin alone, cisplatin+carboplatin, nedaplatin alone and other.

Most patients in the afatinib and methotrexate arms filled out both QLQ-C30 and QLQ-HN35 questionnaires at each visit (95.2% versus 93.8% at randomisation; 69.1% versus 63.3% at end of treatment). More afatinib-treated patients than methotrexate-treated patients reported improvements in QLQ-C30 global health status/quality of life (40% versus 23%) and swallowing symptoms (34% versus 18%; supplementary Figure S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Rates of analgesic use were 59% for afatinib-treated patients and 63% for methotrexate-treated patients (OR 0.65; 95% CI 0.38–1.10; P = 0.11). Patients receiving afatinib had a greater mean change in global health status than patients receiving methotrexate (22.9 versus 15.0; difference 7.9, 95% CI 3.5–12.4; P = 0.0005; supplementary Figure S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Median time to deterioration in global health status, pain and swallowing scores are shown in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Median duration of treatment was 91.5 days [interquartile range (IQR) 49.0–170.5] in the afatinib group, and 42.5 days (IQR 24.5–79.5) in the methotrexate group. Grade ≥3 AEs occurred in 50% of afatinib-treated patients and 45% of methotrexate-treated patients (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online); 16% and 23%, respectively, were drug-related (Table 2). The most frequent grade ≥3 drug-related AEs were rash/acne (4%), diarrhoea (4%), and stomatitis (3%) with afatinib, and anaemia, fatigue and leukopenia (all 5%) with methotrexate (Table 2). Drug-related AEs led to dose reductions in 22% and 29% of patients in the afatinib and methotrexate groups, respectively (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online), and to discontinuation in 11% and 17% of patients.

Table 2.

Most common drug-related adverse events (≥10% of patients in either treatment group)

| Afatinib (n = 228) |

Methotrexate (n = 104) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | |

| Any drug-related adverse event | 165 (72) | 32 (14) | 3 (1) | 2 (<1) | 46 (44) | 16 (15) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) |

| Diarrhoea | 145 (64) | 8 (4) | 0 | 0 | 6 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rash/acnea | 116 (51) | 10 (4) | 0 | 0 | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stomatitisb | 79 (35) | 7 (3) | 0 | 0 | 24 (23) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Paronychiac | 40 (18) | 2 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dermatitis acneiform | 27 (12) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mouth ulceration | 23 (10) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 6 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigued | 11 (5) | 3 (1) | 0 | 0 | 12 (12) | 5 (5) | 0 | 0 |

| Anaemia | 6 (3) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 6 (6) | 5 (5) | 0 | 0 |

| Leukopeniae | 3 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 (16) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 |

| Increased alanine aminotransferase | 3 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (12) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (8) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 |

Grouped term including acne, blister, dermatitis, dermatitis acneiform, eczema, erythema, folliculitis, rash, rash maculo-papular, rash pustular, skin exfoliation, skin fissures, skin lesion, skin reaction, and skin ulcer.

Grouped term including aphthous ulcer, mouth ulceration, mucosal erosion, mucosal inflammation, and stomatitis.

Grouped term including nail bed infection and paronychia.

Grouped term including asthenia, fatigue, lethargy, malaise.

Grouped term including leukopenia and decreased white blood cell count.

Serious AEs occurred in 40% and 35% of patients treated with afatinib and methotrexate; these were considered drug-related in 8% and 15% of patients, respectively. Fatal AEs occurred in 23% and 11% of patients; of these, two deaths (<1%) in the afatinib group (hypoglycaemia and lung infiltration/pneumonitis) and four (4%) in the methotrexate group (lung infection, pneumonia, respiratory failure, and tumour haemorrhage) were considered drug-related. In the afatinib group, most fatal AEs were considered related to disease progression (n = 28). Most fatal AEs (77% and 82% in the afatinib and methotrexate groups, respectively) occurred after termination of treatment. The rate of fatal AEs adjusted by time at risk was 0.51 event/patient year for afatinib and 0.43 event/patient year for methotrexate.

Among the patients who discontinued study treatment, 32% of the afatinib-treated patients and 38% of the methotrexate-treated patients received subsequent anticancer therapy (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Discussion

This study demonstrated a significant, clinically meaningful, improvement in PFS with afatinib versus methotrexate in Asian patients with recurrent/metastatic HNSCC. Importantly, PFS benefit was generally consistent across prespecified patient subgroups and over time. While the difference in median PFS between the two treatment groups was numerically small (2.9 versus 2.6 months, respectively), the HR, which summarises the treatment difference over the entire duration of the trial, favoured afatinib [12]. Furthermore, the PFS benefit with afatinib was substantiated by the high response rates and patient-reported HRQoL benefits versus methotrexate. The reduction in risk of progression/death was greater in LUX-Head & Neck 3 than LUX-Head & Neck 1. While there was no significant difference in OS with afatinib versus methotrexate, the study was not powered to detect an OS benefit.

In this study, the p16 status of tumours was not available for over 60% of patients. Nevertheless, based on available data, a high proportion of patients had p16-negative tumours, as expected for an Asian population, indicating low rates of HPV-related HNSCC [13−15]. Interestingly, HPV-negative disease has been associated with EGFR amplifications [16], suggesting HPV-negative patients may derive particular benefit from EGFR-targeted therapy. The PFS benefit in p16-negative patients seen here is in line with that observed in LUX-Head & Neck 1, albeit based on fewer patients with available p16 status, and is consistent with this hypothesis. In both studies, particular PFS benefit was also seen in EGFR pre-treatment-naïve patients and those who had not responded to prior platinum therapy. Future approval of immunotherapeutic drugs in a first-line setting will likely increase the proportion of patients who are EGFR pre-treatment-naïve at the onset of second-line treatment.

Owing to the potential impact of HNSCC on basic activities such as breathing, swallowing and speaking, effective, and prolonged tumour reduction is particularly important [17, 18]. Although direct cross-trial comparisons are not possible, given differences in study populations and design, the ORR with afatinib (28%) was of interest in the context of other monotherapy studies in the second-line setting, where rates of 4%–14% are common with single-agent methotrexate, paclitaxel, and cetuximab [19, 20]. Furthermore, while both pembrolizumab and nivolumab have demonstrated significant OS benefit versus standard care in this setting, the ORR was only 15% and 13%, respectively, although median duration of response was considerably higher than observed with afatinib in the current study [4, 5]. Of note, the ORR with afatinib was higher than seen in LUX-Head & Neck 1 (10%), possibly reflecting differences in the proportions of p16-negativity and EGFR pre-treatment [6]. Indeed, in LUX-Head & Neck 1, higher ORRs were seen in patients with p16-negative disease (14%) and EGFR pre-treatment-naïve patients (20%) than in the overall population [6], with an ORR of 28% reported for EGFR pre-treatment naïve patients who also had p16-negative disease [21].

The improvements in swallowing symptoms and global health status with afatinib further demonstrate the clinical relevance of our findings. While there was no significant reduction in pain symptoms, the reduced use of analgesics with afatinib versus methotrexate is encouraging. While stable scores across the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 functional and symptom domains were reported with nivolumab in the CheckMate 141 study [22], as yet, there are limited data on the effects of other targeted therapies on patient-reported outcomes in recurrent/metastatic HNSCC, limiting comparisons of different treatment options.

The safety profile of afatinib was in line with previous clinical experience with afatinib, including LUX-Head & Neck 1 [6], with the most common AEs (diarrhoea, rash and stomatitis) being EGFR-mediated events. However, few AEs were grade ≥3, and discontinuations due to AEs were uncommon, suggesting that, per previous clinical experience, they can be readily managed with appropriate treatment and tolerability-guided dose modification. The results demonstrated the feasibility of prolonged afatinib treatment, with a median treatment duration more than double that of methotrexate. While the incidence of fatal AEs was higher in the afatinib group versus the methotrexate group, few of these deaths were considered treatment related. The incidence of fatal AEs considered drug-related was similar to that seen in LUX-Head & Neck 1 (<1% in the afatinib group and 3% in the methotrexate group). The difference in the total incidence of fatal AEs between the afatinib and methotrexate groups in LUX-Head & Neck 3 could reflect the longer duration of exposure with afatinib versus methotrexate.

One potential limitation of our study is the choice of methotrexate as a comparator. However, methotrexate is a globally accepted second-line treatment and is widely used in Asian countries, where the newer anti-PD1 immunotherapies are often unavailable. Furthermore, LUX-Head & Neck 3 was not designed or powered to detect an OS benefit, and many patients will likely have received subsequent therapies beyond second-line treatment, limiting interpretation of the OS results. Finally, owing to the different administration routes, patients and clinicians were not blinded to study group, possibly confounding reporting of AEs.

In summary, LUX-Head & Neck 3 substantiates the previous LUX-Head & Neck 1 study, further demonstrating the feasibility of oral afatinib as a second-line treatment option for patients with recurrent/metastatic HNSCC. These results are of particular relevance for patients in Asian countries, where there are high rates of HPV-negative disease and low rates of EGFR pre-treatment. They could also have wider global relevance if immunotherapy agents are approved in the first-line setting [2], a change that is likely to increase the proportion of second-line patients who are EGFR treatment-naïve. In this regard, further research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of afatinib in the post-immunotherapy setting.

Data sharing

The clinical study report (including appendices, but without line listings) and other clinical documents related to this study may be accessed on request. Before providing access, the documents and data will be examined, and, if necessary, redacted and de-identified to protect the personal data of study participants and personnel, and to respect the boundaries of the informed consent of the study participants. See https://trials.boehringer-ingelheim.com/data_sharing/sharing.html#accordion-1-2 for further details. Bona fide, qualified scientific and medical researchers may request access de-identified, analysable patient-level study data, together with documentation describing the structure and content of the datasets. Researchers should use https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/ to request access to raw data from this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance, supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim, was provided by Jane Saunders and Lynn Pritchard of GeoMed, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim. No grant number was applied.

Disclosure

YGu received honoraria from Merck Serono, Roche, Celgene, Janssen, Bayer, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim. M-JA received honoraria from AstraZeneca, MSD, ONO, BMS and consultant fees from Alpha pharmaceutical. AC received honoraria from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck Serono, Cullinan Management, Inc., Immunomic Therapeutics, Inc., Tessa Therapeutics; and research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, Pfizer Eli Lilly, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme; non-financial support, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche. EEWC received advisory fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, Merck. YGe and EZ report employment from Boehringer Ingelheim. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Gold KA, Lee HY, Kim ES.. Targeted therapies in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer 2009; 115(5): 922–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Forster MD, Devlin MJ.. Immune checkpoint inhibition in head and neck cancer. Front Oncol 2018; 8: 310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seiwert TY, Fayette J, Cupissol D. et al. A randomized, phase II study of afatinib versus cetuximab in metastatic or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Oncol 2014; 25(9): 1813–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohen EEW, Soulieres D, Le Tourneau C. et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019; 393(10167): 156–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr, Fayette J. et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(19): 1856–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Machiels JP, Haddad RI, Fayette J. et al. Afatinib versus methotrexate as second-line treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck progressing on or after platinum-based therapy (LUX-Head & Neck 1): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(5): 583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rao Kulkarni M. Head and neck cancer burden in India. Int J Head Neck Surg 2013; 4(1): 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guo L, Yang F, Yin Y. et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus type-16 in head and neck cancer among the Chinese population: a meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2018; 8: 619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shaikh MH, Khan AI, Sadat A. et al. Prevalence and types of high-risk human papillomaviruses in head and neck cancers from Bangladesh. BMC Cancer 2017; 17(1): 792.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stein AP, Saha S, Kraninger JL. et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal cancer: a systematic review. Cancer J 2015; 21(3): 138–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Machiels JP, Subramanian S, Ruzsa A. et al. Zalutumumab plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy: an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12(4): 333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barraclough H, Simms L, Govindan R.. Biostatistics primer: what a clinician ought to know: hazard ratios. J Thorac Oncol 2011; 6(6): 978–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang H, Sun R, Lin H, Hu WH.. P16INK4A as a surrogate biomarker for human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal carcinoma: consideration of some aspects. Cancer Sci 2013; 104(12): 1553–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deng Z, Hasegawa M, Aoki K. et al. A comprehensive evaluation of human papillomavirus positive status and p16INK4a overexpression as a prognostic biomarker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol 2014; 45(1): 67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vermorken JB, Psyrri A, Mesia R. et al. Impact of tumor HPV status on outcome in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck receiving chemotherapy with or without cetuximab: retrospective analysis of the phase III EXTREME trial. Ann Oncol 2014; 25(4): 801–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mirghani H, Amen F, Moreau F. et al. Oropharyngeal cancers: relationship between epidermal growth factor receptor alterations and human papillomavirus status. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50(6): 1100–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murphy BA. To treat or not to treat: balancing therapeutic outcomes, toxicity and quality of life in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck cancer. J Support Oncol 2013; 11(4): 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gandhi AK, Roy S, Thakar A. et al. Symptom burden and quality of life in advanced head and neck cancer patients: AIIMS study of 100 patients. Indian J Palliat Care 2014; 20(3): 189–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lala M, Chirovsky D, Cheng JD, Mayawala K.. Clinical outcomes with therapies for previously treated recurrent/metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (R/M HNSCC): a systematic literature review. Oral Oncol 2018; 84: 108–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vermorken JB, Trigo J, Hitt R. et al. Open-label, uncontrolled, multicenter phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of cetuximab as a single agent in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck who failed to respond to platinum-based therapy. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25(16): 2171–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cohen EEW, Licitra LF, Burtness B. et al. Biomarkers predict enhanced clinical outcomes with afatinib versus methotrexate in patients with second-line recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(10): 2526–2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harrington KJ, Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr. et al. Nivolumab versus standard, single-agent therapy of investigator's choice in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (CheckMate 141): health-related quality-of-life results from a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18(8): 1104–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.