Abstract

The political momentum around universal health coverage (UHC) provides a welcome opportunity to scale up efforts to dismantle barriers to accessing health services and to create enabling environments for people to thrive and be healthy. However, UHC lacks sufficient clarity, both conceptually and operationally, to generate the societal transformation required to ensure its successful implementation in countries. This article argues that both the messaging and the monitoring and implementation guidance around UHC are ambiguous and flawed from a human rights perspective. To leverage the reforms necessary to achieve UHC, human rights norms and principles need to signpost the direction ahead, and human rights mechanisms need to be involved to enhance the accountability of those United Nations member states that choose to “take a wrong turn.” The article argues that a human rights-based approach to programming offers a practical methodological framework for designing and implementing UHC at the national level. It concludes by illustrating five key areas in which it is critical to invoke human rights as the foundation for UHC and for which consistent, authoritative, and practical guidance is needed to support countries in getting onto the right(s) road to UHC.

Introduction

Universal health coverage (UHC) has risen on the global health agenda since its adoption as a Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target and now features prominently in the advocacy of global health institutions.1 “All roads lead to universal health coverage,” according to World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, who has made UHC the organization’s top priority while considering UHC, ultimately, to be a political choice.2

UHC provides a welcome and unifying platform for the global health community to focus its efforts in the midst of competing priorities. However, its ability to leverage the reforms necessary in countries to achieve its intended purpose is hampered by its own ambiguity, which reflects a deeper failure to put people and their rights at the center of health and health systems. This failure has, in many countries, led to priorities being skewed away from poor, vulnerable, and marginalized communities; services not reaching deep and far enough; widespread out-of-pocket spending by patients; and rampant corruption.3

Addressing UHC requires grappling with a wide spectrum of laws, policies, and practices that reflect the willingness and capacity of governments to deliver on their commitments and meet their human rights obligations.4 To secure meaningful progress, therefore, global health and development institutions leading efforts to support countries in implementing UHC must step up to the task of clarifying UHC and signposting the journey ahead, conceptually and operationally, in line with relevant human rights norms and principles.

Following this introduction, the first part of this article unpacks the assertion that UHC is rooted in a wider, longer, and deeper journey toward the realization of human rights, using various legal, historical, institutional, and social arguments. The second part briefly examines the current messaging and monitoring and implementation guidance around UHC from a human rights perspective. The third and last part argues that a human rights-based approach (HRBA) to programming provides a useful methodological framework for implementing UHC at the national level and concludes by highlighting five critical areas in which consistent, authoritative, and practical guidance is urgently needed to support countries in getting onto the right(s) road to UHC.5

The long and continuous road toward the realization of rights

The peoples of the United Nations have “reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom.”

—Universal Declaration of Human Rights, preamble

UHC and other SDGs and targets are critical milestones, or “an important step on the longer, and continuous, road towards the full and effective realization of all human rights for all.”6

2030 Agenda rooted in human rights

UHC has been widely articulated across General Assembly and World Health Assembly resolutions in recent years.7 Its formulation culminated in SDG target 3.8, which sets out the commitment of United Nations (UN) member states to “achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.”8

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which builds on and expands from the Millennium Development Goals, can be characterized as a nonbinding consensual UN policy document to be interpreted in a manner consistent with the treaties and principles of international law.9 In this regard, the 2030 Agenda sets out that the 17 SDGs and 169 targets “seek to realize the human rights of all,” that the agenda is “grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [and] international human rights treaties,” and that it is to be “implemented in a manner that is consistent with the rights and obligations of States under international law.”10

Universal Declaration of Human Rights: The launching pad of UHC

UHC implicates a wide range of human rights, including the rights to life; health; security; equality and nondiscrimination; freedom of movement, association, and assembly; information; expression; privacy; participation; an adequate standard of living; food; water; adequate housing; education; social security; and access to the benefits of scientific progress. These and other rights are enshrined in international and regional treaties and in national constitutions, and they also form part of customary international law. Overall, they can be traced back to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which established the normative foundation for the international human rights movement.11

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted in the aftermath of the Second World War, shortly after the creation of the UN, of which human rights form part of its foundational purposes.12 In this spirit, the WHO Constitution (1946) set out the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health as a human right.13 During this period, many industrialized countries emerging from the devastation of the war established their health systems (for example, France in 1945, Japan in 1951, and the United Kingdom in 1948). Today, these systems are integral to the wider governance of society as reflected in the Alma-Ata and Astana declarations on primary health care, which reaffirm governments’ responsibility to promote the health of their people and which refer to health as a human right.14 Furthermore, ample legislation and jurisprudence testify how human rights norms and principles should permeate national health systems and set parameters for what governments, as the stewards of these systems, can and should do, as well as what they are not permitted to do.15

Knitting UHC into the right to health

General Assembly and World Health Assembly resolutions adopted on UHC over the years have consistently reiterated how human rights—particularly the right to health—provide the overarching framework for UHC.16 To give a recent example, the first operative paragraph of the political declaration adopted at the high-level meeting on UHC reaffirms health as a human right.17 In a similar vein, the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health has emphasized that UHC must be understood as consistent with the right to health.18

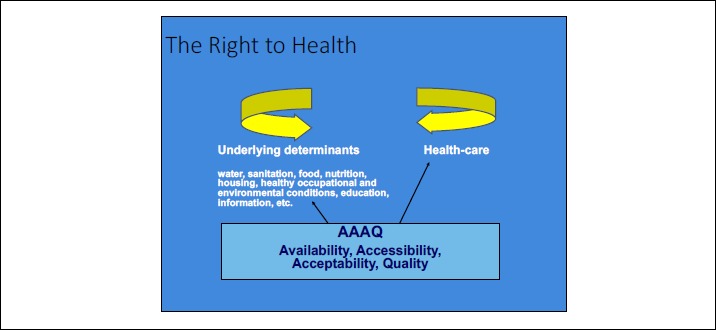

General Comment 14 adopted by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2000 provides an authoritative interpretation of the normative scope and content of the right to health (Figure 1).19 As such, it can be considered to flesh out the constitutional provision of WHO on the right to health while underscoring WHO’s role in supporting the realization of the right to health through “the formulation of health policies, or the implementation of health programmes.”20

Figure 1.

Normative scope and content of the right to health

Source: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and World Health Organization, The right to health: Fact sheet no. 31 (June 2008). Available at http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Factsheet31.pdf.

The concept of UHC, in turn, is rooted in the WHO secretariat’s efforts to address health financing as a basic building block of a strong and well-performing health system. Interestingly, WHO’s framework for monitoring health systems’ performance was developed in parallel with the drafting of General Comment 14. The WHO secretariat attempted to forge synergies by providing input into the drafting of General Comment 14 and, conversely, integrating critical aspects of the right to health into its measurement strategy for health systems around access, utilization, quality, and effective coverage.21 Moreover, WHO’s health systems indicators were drawn on in the identification of appropriate indicators to monitor the realization of the right to health.22

UHC in “human rights terms”

The first two letters in the acronym UHC can be easily defined using international instruments. “Universal” in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights clearly means everyone, and “health” is defined broadly in WHO’s Constitution.23 While the word “coverage” is often interpreted in accordance with American English usage to refer to insurance, its origin—“cover”—resonates with protection, a fundamental human rights principle.24 As such, “coverage” is linked to social protection under SDG 1.3, which is, in turn, anchored in the human right to social security.25 The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has interpreted “coverage” to mean that “all persons are covered by the social security system, especially individuals belonging to the most disadvantaged and marginalized groups without discrimination” and has noted that noncontributory schemes are necessary to ensure “universal coverage.”26

The risk of sliding down narrow and slippery paths

“If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there.”

—Lewis Carroll

Current guidance and messaging around UHC reveal incoherence in terms of how UHC is understood, in addition to numerous human rights deficits, which will inevitably hamper countries’ ability to leverage the structural reforms necessary for its achievement.

Stuck in a box

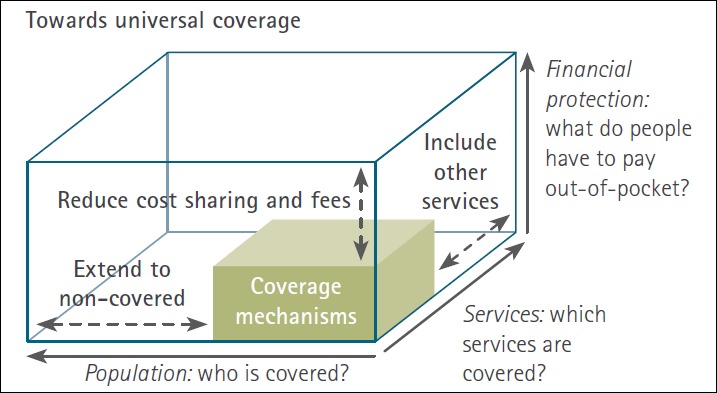

Guidance on UHC implementation tends to jump right into the question of “financial risk protection” rather than focusing on UHC writ large. Moreover, the debate around progress toward UHC implementation often starts on a negative footing that assumes difficult financing decisions.27 In fact, UHC is often associated with a box (Figure 2) depicting trade-offs among the proportions of the population to be covered, the range of services to be made available, and the proportion of the total costs to be met.28

Figure 2.

The three dimensions (policy choices) of UHC

Source: World Health Organization, Universal coverage: Three dimensions. Available at http://www.who.int/health_financing/strategy/dimensions/en.

In this context, the human rights principle of progressive realization has been extracted from other interrelated norms and principles and is applied to describe what are considered “policy choices.”29 This negates other interrelated human rights principles relevant to any priority-setting exercise, such as nonretrogression, minimum core content, maximum available resources, international assistance and cooperation, and equality and nondiscrimination.30 It also disregards the process for setting priorities, which is equally important from a rights perspective and must be transparent, participatory (involving affected communities and other rights holders), and guided by an HRBA to programming (see the last section of this article).31

By diving into this “box,” the analysis misses the crucial opportunity to explore why needs and rights are not being met or realized in the first place, and it also fails to allow for an expansive interpretation of UHC that goes beyond the issue of health sector resources. The box accepts an unfortunate (and oftentimes unacceptable) status quo: the fact that a variety of technologies, goods, and services are unaffordable. In this context, and as an example, case studies illustrating how to make trade-offs include an agonizing account of whether to include hepatitis B treatment in UHC, thus implicitly accepting its exorbitant price as a given.32 Just imagine where we would be with the AIDS epidemic today if prices of antiretroviral medicines had not been questioned and the injustice of unaffordable medicines not acted on through strategic litigation and other strategies.33 Consider, moreover, how investing in expanding hepatitis B treatment ultimately saves costs in the long run by reducing long-term medical expenses for liver cancer and cirrhosis.34

Why not measure what we treasure?

Several human rights considerations arise in relation to the monitoring of UHC. The two indicators adopted by the United Nations Statistical Commission in March 2017 for UHC are as follows:

3.8.1 Coverage of essential health services (defined as the average coverage of essential services based on tracer interventions that include reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases and service capacity and access, among the general and the most disadvantaged population).

3.8.2 Proportion of population with large household expenditures on health as a share of total household expenditure or income.35

Firstly, the global indicator framework for the 2030 Agenda supports efforts to ensure equality and nondiscrimination by calling for indicators to be disaggregated.36 WHO reports, however, that “because of the lack of data, it is not yet possible to compare the UHC service coverage index across key dimensions of inequality.”37 Another observation is that despite target 3.8’s explicit reference to access to essential medicines, WHO’s extensive experience in monitoring this aspect of UHC, and the fact that access to essential medicines is a core obligation of the right to health, neither of the indicators mentions essential medicines.38

Several questions from a rights perspective arise in relation to indicator 3.8.2, starting with its focus on “households,” which can mask significant power differentials that reflect entrenched patterns of discrimination in society at large. Evidence reveals that labeling a household as rich or poor, moreover, is an oversimplification and masks “intrahousehold inequality,” which often hits children hardest.39 While practical from a measurement point of view, household expenditure will not help track key human rights dimensions, such as gender equality, in the context of UHC and risks missing vulnerable household members such as persons with mental or physical disabilities.

More fundamentally, the way that 3.8.2. is formulated incorporates an assumption of how societies are structured, with households paying for health care (while also supposing that “health” means “health care”). This echoes an underlying view of health as a commodity or individual responsibility, which is problematic from a rights perspective. Studies have demonstrated, furthermore, that to reduce catastrophic payment incidence, the share of total health expenditure that is prepaid needs to be increased, particularly through taxes and mandatory contributions.40 Ironically, in this regard, the indicators risk being irrelevant or difficult to measure for countries that ensure the most health expenditure through taxes.41

To ensure a more holistic monitoring approach to UHC, it is critical to underscore the interconnectedness and interdependence of human rights and their respective linkages to various SDGs. For instance, SDG 16—which addresses several human rights-related issues, such as democratic governance, the rule of law, access to justice, and personal security—is increasingly becoming central to national planning, budgeting, and reporting in some African countries (for example, Ghana and Benin are emphasizing budget spending that has a high SDG 16 impact).42

Inconsistent messaging

In contrast to the relatively narrow and technical exercises of UHC indicators and guidance, the advocacy around UHC is increasingly dispersed and all-encompassing, with the global health community advocating for UHC as the pathway to numerous other SDG-health targets and issues, from diseases to wider prevention efforts and actions to address the underlying determinants of health.43

According to WHO, UHC means that “all individuals and communities receive the health services they need without suffering financial hardship.”44 In contrast to this rather top-down and passive formulation, in another publication WHO describes UHC as an active subject that “delivers disease prevention, health promotion, and treatment for communicable and noncommunicable diseases alike.”45 In other words, the way that UHC is referred to is circular, with “UHC delivering UHC.”

Messaging around UHC and human rights has added to the confusion around UHC’s scope and content. Interpretations vary: At one end of the spectrum is WHO’s director-general asserting that “universal health coverage is a human right,” thus assuming a new self-standing human right to UHC.46 At the other end, WHO has published a policy brief on “what policy makers should keep in mind if they want to use UHC as a way to promote the right to health,” sending the message that UHC is somehow separate from, and outside of, the realm of human rights and that governments can choose to implement UHC in isolation from their human rights obligations.47

The need to signpost the journey ahead

“Action without vision is only passing time, vision without action is merely day dreaming, but vision with action can change the world.”

—Nelson Mandela

The vision of UHC anchored in human rights norms and principles is expansive and helps provide clarity in interpreting UHC. It would be timely to translate it into clear and coherent messaging as well as firm and thoughtful normative guidance to support countries. In this regard, a human rights-based approach to programming provides a practical methodological framework for designing and implementing UHC at the national level. While several areas are ripe for attention and need to be included in such a roadmap, five interrelated ones can help us illustrate the way forward:

1. Government in the driver’s seat but all eyes on the road

While the government is the prime duty bearer under international human rights law and has a legitimate place in the driver’s seat, a strong and vibrant civil society needs to occupy a front seat in the journey toward UHC. Activism needs to be nurtured, not least among young people, who need to be at the helm of UHC implementation. To exercise their essential functions—including those of advocate, watchdog, whistle-blower, and service provider—civil society organizations require support in light of the growing number of countries that are passing restrictive legislation to prevent or deter them from performing their work.48 They will also need to help convene and facilitate coalition building across wider movements dedicated to specific health issues (such as HIV, tuberculosis, mental health, and noncommunicable diseases) and those representing specific population groups.49 This process of cultivating active agents of change for UHC from within the societies in which they live will be key to success.

Working hand in hand with civil society, affected communities, and other relevant stakeholders, governments can initiate the journey by doing a thorough situational analysis using an HRBA to programming, which starts by assessing the health needs and rights of individuals and groups in light of constitutional and international human rights obligations.50 Process is central in an HRBA, and several human rights principles—such as freedom of association, which has a long history in supporting the realization of social rights—are relevant. As an illustration, consider how the freedom of association, when legalized in France in 1884, led to a social dialogue from which workers were able to claim their social rights at the enterprise and national levels.51 Today, many of these principles, such as the right to participation, are enshrined not only in national laws but also at the provincial level (for example, the Kisumu County Public Participation Act of 2015 in Kenya) and at times establish mechanisms such as committees for community participation in health (for example, Law No. 100 of 1993 in Colombia).52

Using an HRBA to programming helps identify a spectrum of bottlenecks to UHC implementation, as it considers the roles of rights holders and duty bearers. A lack of political will from duty bearers, for example, may be found to be rooted in an entrenched lack of motivation among the governing elite for various reasons, such as their own ability to travel abroad whenever requiring medical treatment.53 Working closely with civil society organizations and the wider human rights community, efforts to support UHC implementation can include ensuring that those countries that “stray off the road”—for example, by joining forces with, or bowing to, powerful interests—are held to account for failing to fulfill their human rights obligations.

The 2030 Agenda, with its voluntary national reviews and peer-reviewed soft guidance, lacks an accountability framework. This is where human rights not only offer a legal basis and guidance in the implementation of UHC but also a plethora of mechanisms to enhance accountability, including national human rights institutions, ombudspersons, parliamentary committees, and courts. National constitutions supported by legislation can play a central role in realizing the rights to social security, health, and equality, and when articulated as explicit entitlements grounded in law, they can sustain across time as governments come and go.54 UHC will need to be reflected in national laws—and this is perhaps the most critical phase, as legislation often ultimately determines who will benefit from health coverage and how.55 Litigation can then be an effective strategy for highlighting health system failures and challenging discriminatory historical structures and hierarchies, thereby spurring broader social, economic, and political change.56

At the global and regional levels, mechanisms include UN human rights treaty bodies, which monitor states’ compliance with treaty implementation; optional protocols, which allow individuals to petition governments; and the Special Procedures and Universal Periodic Review of the UN Human Rights Council. Human rights monitoring mechanisms are already and systematically pointing out inconsistencies as countries come up for scrutiny when it comes to UHC implementation. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, for example, has expressed concern about South Africa’s attempts to achieve UHC through its National Health Insurance Bill, which excluded non-nationals.57

2. Reach the furthest behind first

“Universal” means everyone; however, WHO advises countries to pursue at least “a minimum of 80% population coverage of essential health services” and asserts that “all countries can reach some level of universality.”58 A review of experiences from Indonesia, Kenya, Uganda, and Ukraine in integrating HIV treatment into UHC revealed how the 20% who are not covered likely include marginalized people, in particular key populations stigmatized and criminalized because of their HIV status, sexual orientation, gender identity, behavior (for example, drug use), or occupation (for example, sex workers).59

The HIV response has revealed how punitive laws, discrimination, and other forms of exclusion fuel vulnerability to disease, poverty, and ill-health and how, in corollary, the ability of affected communities to protect themselves or survive HIV clearly depends on their ability to exercise their rights.60 UNAIDS is now calling for lessons of the HIV response to be applied to efforts to achieve UHC.61 Importantly, in the 2030 Agenda, UN member states have committed “to endeavour to reach the furthest behind first.”62 In this spirit, UNICEF advocates for actions toward UHC to first address the needs of those currently left behind, given that these populations often have the least political voice.63

Redressing de facto discrimination and achieving substantive equality may require states to adopt special measures.64 For instance, in the context of its state reporting to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the United States was urged to

take concrete measures to ensure that all individuals, in particular those belonging to racial and ethnic minorities who reside in states that have opted out of the Affordable Care Act, undocumented immigrants and immigrants and their families who have been residing lawfully in the United States for less than five years, have effective access to affordable and adequate health-care services.65

WHO and other UN agencies must be consistent and forceful in their messaging so that “universal” is clearly understood to mean everyone. In other words, the journey to UHC needs to start by reaching those left furthest behind while stepping up support to states for civil registration and vital statistics systems and other relevant tools.66

3. Strap the private sector firmly into the backseat

The operationalization of UHC is currently underway in a muddied playing field of diverse stakeholders pursuing different agendas. Among these stakeholders are powerful private sector actors with high stakes in how UHC is interpreted and implemented. These actors include insurance companies, health care providers, and pharmaceutical companies, for which, evidently, UHC can help boost revenue and stock value, which heightens the risk that its ambiguities are exploited to push for a market- and (private) insurance-driven model.67 The ability of such actors to influence the interpretation and implementation of UHC (often through governments) should not be underestimated. For example, in the United States, Big Pharma tops the lists for US campaign contributions and lobbying dollars, with the industry spending US$28 million in 2018 on lobbying, and the pharmaceutical and health products industry overall spending US$280 million in 2018 to influence federal policy.68

At the international level, many private sector actors are already shaping the public health agenda, often under the umbrella of public-private partnerships or in more subtle but sophisticated ways.69 At the national level, moreover, these partnerships are growing, including in low-income countries such as Uganda, where efforts by civil society to promote the accountability of public-private partnerships have been undermined by a lack of information, transparency, participation, and remedial mechanisms.70 In this regard, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights recently adopted a resolution expressing concern about “the current trend amongst bilateral donors and international institutions of putting ‘pressure on States Parties to privatize or facilitate access to private actors in their health and education sectors.”71 As the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health observed in his mission report on Algeria:

owing to the quality of care provided in the public sector and the dissatisfaction of service users, the private sector was growing fast and in an unregulated manner. This was leading to a dual system that offered better quality care for those who could afford to pay out of pocket or travel abroad to be treated, thereby increasing inequalities in access to health care.72

General Comment 24 of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights calls on states to subject private providers to strict regulations that prohibit them from denying access to affordable and adequate services, treatments, or information.73 States need support in operationalizing relevant human rights standards, such as those set out in the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which UN member states endorsed as part of the 2030 Agenda.74 The field of education provides inspiration: for example, the recently adopted Abidjan Principles provide guidance in the context of the rapid expansion of private sector involvement in education.75 Another initiative from the field of education is the recent commitment undertaken by the board of the Global Partnership for Education not to support for-profit provision of core education services.76

WHO has experience in supporting states in their regulation of the private sector. Two examples are the implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and the 1981 International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes.77 It is imperative that WHO step up its support to states in this area in the context of UHC. Guidance and mechanisms to tackle conflicts of interest, secure access to justice, and ensure effective remedies when private actors are responsible for violating health-related human rights are urgently needed. At present, civil society organizations are taking on this tremendously important task without the requisite engagement, leadership, and support from WHO, the World Bank, and other leading actors in the field of UHC.78

4. Stay on course and don’t divert down narrow paths

UHC was conceptualized in the context of states’ recognition of health as a foreign policy issue, inviting a multisectoral approach.79 In line with the expansive definition of health, and in support of the realization of the right to health, UHC extends beyond the health sector to the underlying determinants of health. These determinants include access to safe and potable water and adequate sanitation, an adequate supply of safe food, nutrition and housing, healthy occupational and environmental conditions, and access to health-related education and information, including on sexual and reproductive health.80

When it comes to health care specifically, an expansive interpretation is required, starting at the community level with primary care in an integrated, coordinated, community-oriented, and person-focused care system.81 An HRBA situational analysis, with affected communities at the forefront, can help determine what services are deemed priority and what barriers exist to making them available. “Availability”—the initial “A” in the AAAQ framework, which underpins the right to health—addresses the question whether health personnel, medicines, and facilities are in place in the first place. Sobering statistics (from 2013 to 2018) indicate that all least developed countries had fewer than 10 medical doctors and fewer than 5 dentists and 5 pharmacists per 10,000 people, and 98% had fewer than 40 nursing and midwifery personnel per 10,000 people.82 To illustrate how stark these numbers really are, contrast the average of 3.1 medical doctors per 10,000 people in low-income countries with the global average of 15.1 per 10,000 and with the fact that high-income countries have twice the global average.83 A lesson learned from the HIV response, in this context, has been the engagement of community health workers as part of wider community health systems; these workers are often better placed to reach people who are being left behind due to prejudice, poverty, punitive laws, or geographical distance.84

5. Tackle roadblocks and replenish

An HRBA to programming can help unpack whether and in what way the government lacks capacity or is unwilling to meet its human rights obligations. It can reveal numerous barriers to UHC beyond those traditionally considered financial barriers, addressing related costs such as transportation to facilities or corruption. In relation to the latter, for example, a recent study across 34 African countries found that more than one in four people who accessed public services, such as health care and education, paid a bribe in the preceding year, and that the poorest people were twice as likely to pay a bribe as the richest people.85

Critically, an HRBA allows the analysis to go “upstream” to consider harmful and punitive laws, policies, and practices that oftentimes may require political will to reform yet may require minimal financial resources to change. An example is spousal consent in order for women to access sexual and reproductive health services, which is required in 29 countries.86 Another is how across 19 countries, HIV status has been found to have resulted in approximately one in five people living with HIV having been denied health care (including dental care, family planning services, and sexual and reproductive health services).87 By exposing and addressing barriers beyond just the financial ones, the journey toward UHC will move faster and help ensure that gaps among different populations are not widened.

Human rights obligations, including the obligation to fulfill (which requires states to adopt appropriate legislative, administrative, budgetary, judicial, promotional, and other measures), bind the government as a whole—in other words, ministries of finance, planning, and trade are equally accountable as the ministry of health when it comes to advancing UHC.88 In our complex and interdependent world, governments need to navigate and defend the right to health among a myriad of push-and-pull factors that take many different shapes and forms, from trade agreements to investment treaties. Moreover, there is a pressing need to go beyond traditional sources of aid and trade and address structural causes that are blocking financing for sustainable development, from a heavy debt burden on countries to illicit financial flows.

Prioritizing reliable domestic financing is a prerequisite to sustain the gains made toward UHC and may require tax reform. Too often, valuable resources are being diverted from states; the International Monetary Fund alerts that developing countries are most affected by corporate base erosion and profit shifting, generating losses of 1.3% of GDP for non-OECD countries.89 The tax burden often shifts from multinational enterprises to small and medium enterprises, and to the rest of the population via indirect regressive taxes such as value-added taxes, which have a particularly negative impact on women and marginalized groups.90 Another sobering statistic is that only US$0.04 of every US$1 of tax revenue comes from taxes on wealth.91 Undertaxing the richest segments of the population leads to the underfunding of public services, which are then often outsourced to private companies that exclude the poorest.92 As Jeffrey Sachs has noted, a 1% net worth tax on billionaires could in principle fund both UHC and universal education access in low-income countries.93

Finally, and to end on a positive note, the transformative 2030 Agenda creates exciting new opportunities to explore win-win scenarios across the SDGs, including health and the environment. In relation to financing, for example, the Nigerian Sustainable Finance Roadmap lists health as the first of its examples of sustainability-related factors that could influence an alternative future growth trajectory, noting how air pollution costs the Nigerian economy 1% of gross national income.94 With increasing awareness of the tremendous health impacts of clean air, access to clean water and adequate sanitation, healthy and sustainable food, a safe climate, and healthy biodiversity and ecosystems, creative ways of working across sectors can allow for a dynamic interaction that shifts the focus in UHC to prevention, embracing the expansive scope of the right to health and its interrelatedness and interdependence with other human rights.

Conclusion

Powerlessness, discrimination, inequality, and accountability failures that lead to ill-health and poverty are politically driven and deeply rooted. As a result, the struggle to achieve UHC is inherently political. UHC is not a political “choice,” however, nor do “all roads lead to UHC.” UHC is a human right imperative, and countries urgently need support to get onto the right(s) road to UHC.

As the custodian of the 2030 Agenda and guardian of human rights, the UN is well-placed to articulate how human rights norms and principles provide explicit parameters for UHC implementation. Within and beyond the UN, moreover, 12 multilateral global health agencies have recently pledged to work together to accelerate country progress on the health-related SDG targets.95 Another relevant initiative is UHC2030, which aims to inform collaboration on UHC and includes a civil society engagement mechanism.96 Whichever platform or mechanism is used, WHO, the World Bank, and other agencies involved in UHC implementation must urgently step up efforts to ensure that it promotes, reinforces, and furthers the realization of human rights.

Operational guidance that builds on lessons learned from the HIV response and uses an HRBA to programming should be developed and provided to support countries in their implementation of UHC.97 Otherwise, as warned by the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health, there is a real danger of countries forging ahead with UHC implementation in a way that is disconnected from their human rights obligations.98 We cannot afford to repeat this mistake from the Millennium Development Goal era.99 The hardwiring of human rights in the SDGs needs to be activated as a potentially powerful corrective to counter the risk of UHC implementation sliding down a narrow and dangerous path where vested interests prevail and the most vulnerable and marginalized are left behind.100 Addressing UHC as a human rights imperative—with human rights norms and principles providing explicit and nonnegotiable parameters for moving forward—will help energize, support, and speed up the journey ahead, as well as ensure that it is inclusive and transformative.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Mira Törnqvist, intern at UNAIDS, for support in referencing this article.

The author is currently a staff member of UNAIDS and former staff member of the World Health Organization and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the author may be associated with.

References

- 1.Kirton J., Kickbusch I. Health: A political choice. 2019. See, for example. Available at http://edition.pagesuite.com/html5/reader/production/default.aspx?pubname=&edid=1b1471a7-7575-4371-9969-9e93f7dd4aa8.

- 2.Ghebreyesus T. “All roads lead to universal health coverage,”. Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(9):839–840. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sidibé M., Nygren-Krug H., McBride B. “The future of global governance for health: Putting rights at the center of sustainable development”. Oxford Scholarship Online. 2018. Available at http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780190672676.001.0001/oso-9780190672676-chapter-5.

- 4.Saiz I. “Rising inequality is a wake-up call for human rights, the challenges that economic inequality poses for human rights are not the death knell for the movement but a wake-up call for a more holistic approach,”. Open Global Rights. (May 29, 2018). Available at http://www.openglobalrights.org/rising-inequality-is-a-wake-up-call-for-human-rights/.

- 5.United Nations Sustainable Development Group. Human rights. See. Available at http://undg.org/human-rights/; World Health Organization. A human rights-based approach to health. see also. Available at http://www.who.int/hhr/news/hrba_to_health2.pdf.

- 6.Joint statement of the chairpersons of the UN human rights treaty bodies on the post-2015 development agenda. 2013.

- 7. See, for example, General Assembly, G.A. Res. 74/2, UN Doc. A/RES/74/2 (2019); General Assembly, G.A. Res. 73/337, UN Doc. A/RES/73/337 (2019); General Assembly, G.A. Res. 73/131, UN Doc. A/RES/73/131 (2019); General Assembly, G.A. Res. 72/139, UN Doc. A/RES/72/139 (2018); General Assembly, G.A. Res. 72/108, UN Doc. A/RES/72/138 (2018).

- 8. General Assembly, G.A. Res. 70/1, UN Doc. A/RES/70/1 (2015).

- 9. See, for example, United Nations, Statute of the International Court of Justice (1946), art. 38; Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969).

- 10. General Assembly, G.A. Res. 70/1 (see note 8), preamble, paras. 10, 18.

- 11. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217 A (III) (1948).

- 12. Charter of the United Nations (1945), art. 1.

- 13. General Assembly, Entry into Force of the Constitution of the World Health Organization, UN Doc. A/RES/131 (1947); Constitution of the World Health Organization (1946).

- 14. International Conference on Primary Health Care: Declaration of Alma-Ata, Alma-Ata, September 6–12, 1978; Global Conference on Primary Health Care: Declaration on Primary Health Care, Astana, October 26, 2018.

- 15.Global health and human rights database. See. Available at http://www.globalhealthrights.org/category/health-topics/health-care-and-health-services.

- 16. General Assembly, G.A. Res. 67/81, UN Doc. A/RES/67/81 (2013). See also note 7.

- 17.General Assembly. “Universal health coverage: Moving together to build a healthier world”. (adopted September 23, 2019, at the High-Level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage).

- 18. D. Puras, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, UN Doc. A/71/304 (2016), para. 78.

- 19. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000).

- 20. Ibid., paras. 1, 4, 12, 63.

- 21.Shangelia B., Tandon A., Adams O. B., Murray C. J. “Access, utilization, quality, and effective coverage: An integrated conceptual framework and measurement strategy,”. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations. Human rights indicators: A guide to measurement and implementation. 2012. UN Doc. HR/PUB/12/5.

- 23. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A (III)(1948), arts. 1, 2; Constitution of the World Health Organization (1946), preamble.

- 24. See Lexico, Coverage. Available at http://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/coverage.

- 25.101st session of the International Labour Conference Geneva. R202 – Social protection floors recommendation. June 14, 2012. Available at http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:3065524.

- 26. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 19, The Right to Social Security, UN Doc. E/C.12/GC/19 (2008).

- 27.Chan M. “Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage,”. Health Systems and Reform. 2016;2:5–7. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2015.1111288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Health systems financing: The path to universal health coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. fig. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank. Monitoring progress towards universal health coverage at country and global levels: Frameworks, measures and targets. 2014.

- 30.Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Frequently asked questions on economic, social and cultural rights. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/ESCR/FAQ%20on%20ESCR-en.pdf.

- 31.World Health Organization. A human rights-based approach to health. (see note 5).

- 32.Voorhoeve A., Edejer T., Kapiriri L. et al. “Three case studies in making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage,”. Health and Human Rights Journal. 2016;18(2):11–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.UNAIDS. How AIDS changed everything. 2015. Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/campaigns/HowAIDSchangedeverything.

- 34.Barnhart M. “A convenient truth: Cost of medications need not be a barrier to hepatitis B treatment,”. Global Health Science and Practice. 2016;4:186–190. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. General Assembly, G.A. Res. 71/313, UN Doc. A/RES/71/313 (2017).

- 36. Ibid.

- 37.World Health Organization and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 Global monitoring report. 2017.

- 38.World Health Organization. Access to essential medicines. 2010. Available at http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/WHO_MBHSS_2010_section4_web.pdf.; World Health Organization. WHO Model lists of essential medicines. Available at http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/.

- 39.United Nations Development Programme and Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. Global multidimensional poverty index 2019: Illuminating inequalities. 2019. Available at http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/mpi_2019_publication.pdf.

- 40.Wagstaff A., Flores G., Hsu J. et al. “Progress on catastrophic health spending in 133 countries: A retrospective observational study,”. Lancet Global Health. e169;6(2017):e179. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30429-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Health and Social Affairs Sweden. Sweden’s work on global health: Implementing the 2030 Agenda. Stockholm: Government Offices of Sweden; 2018. p. 39. See. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laberge M. “How Africa measures up on governance,”. Project Syndicate. (July 18, 2019). Available at http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/africa-data-measuring-governance-progress-by-marie-laberge-2019-07.

- 43. Kirton and Kickbusch (see note 1).

- 44.World Health Organization. Questions and answers on universal health coverage. See. Available at http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/uhc_qa/en/.

- 45.World Health Organization. Together on the road to universal health coverage: A call to action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghebreyesus T. Adhanom. “All roads lead to universal health coverage,”. Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(9):e839–e840. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization. Anchoring universal health coverage in the right to health: What difference would it make? Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swiney C. “Undemocratic civil society laws are appearing in democracies,”. Open Global Rights. (March 28, 2019). Available at http://www.openglobalrights.org/undemocratic-civil-society-laws-are-appearing-in-democracies-too/.

- 49. UNAIDS, Report by the NGO Representative (2019). Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/21112019_UNAIDS_PCB45_NGO_Report_EN.pdf.

- 50.Kisumu Civil Society Organization. “UHC conference position paper”. (July, 18 2019). Available at http://www.kelinkenya.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/UHC-Position-Statement-by-Kisumu-CSO-at-the-3rd-UHC-Conference_17052019.pdf.

- 51.the International Labour Organization. 100 years of social protection: The road to universal social protection systems and floors. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2019. p. 16. See. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Republic of Kenya. Kisumu Country Public Participation Act. 2015. Colombia, Ley 100 de 1993 (1993), art. 2.10.1.1.8.

- 53.Kazeem Y. “Africa’s presidents keep going abroad for medical treatment rather than fixing healthcare at home,”. Quartz Africa. (June 30, 2017). Available at http://qz.com/africa/1017973/zimbabwes-mugabe-and-nigerias-buhari-are-two-of-africas-sick-leaders-going-to-hospitals-abroad.; Mwonzora G. “Political will or not? The right to health in Zimbabwe in the era of SDGs,”. Impakter. (March 7, 2019). Available at http://impakter.com/the-right-to-health-in-zimbabwe/.

- 54. International Labour Organization (see note 51), p. 25.

- 55.Magnusson R. “Advancing the right to health: The vital role of law,”. Sydney Law School Research Paper. 2017;17(43) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dunn J. T., Lesyna K., Zaret A. “The role of human rights litigation in improving access to reproductive health care and achieving reductions in maternal mortality,”. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 17(2017) doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1496-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Concluding Observations: South Africa, UN Doc. E/C.12/ZAF/CO/1 (2018).

- 58.World Health Organization. Together on the road to universal health coverage: A call to action. Geneva: World Health Organization ; 2017. p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 59.PITCH. Towards transformative integration of the HIV/AIDS response into Universal Health Coverage: Building on the strengths and successes of the HIV and AIDS response. 2019. p. 6.

- 60.Krug H. Nygren. Human rights in global health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. “The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS: With communities for human rights,”. in B. Mason Meier and L. O. Gostin (eds) [Google Scholar]

- 61.UNAIDS. Delivering on SDG3: Strengthening and integrating comprehensive HIV responses into sustainable health systems for Universal Health Coverage. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 62. General Assembly, G.A. Res. 70/1 (see note 8), para 4.

- 63.UNICEF. The UNICEF health systems strengthening approach. New York: UNICEF; 2016. p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 20, Non-discrimination in Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, UN Doc. E/C.12/GC/20 (2009), art. 2(2).

- 65. Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Concluding Observations: United States of America, UN Doc. CERD/C/USA/CO/7-9 (2014).

- 66.Global Financing Facility and the World Bank Group. Civil registration and vital statistics fact sheet. Available at http://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/sites/gff_new/files/documents/CRVS-GFF-FactSheet-EN.pdf.

- 67. Parroting the Right. Available at http://parrotingtheright.org/.

- 68.Caldwell L. A. “Senators publicly grill ‘Big Pharma’ executives after accepting millions from industry,”. NBC News Digital. (February 26, 2019). Available at http://www.nbcnews.com/politics/congress/senate-testimony-pharma-executive-admits-drug-prices-hit-poor-hardest-n976346?cid=sm_npd_nn_tw_ma.

- 69.Richter J. “Public-private partnerships for health: A trend with no alternatives?,”. Society for International Development. 2004;47(2):43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Initiative for Social and Economic Rights. Achieving equity in health: Are public private partnerships the solution? Kampala: Initiative for Social and Economic Rights; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 71. African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Resolution on States’ Obligation to Regulate Private Actors Involved in the Provision of Health and Education Services, Res. 420 (LXIV) (2019).

- 72. Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health on His Visit to Algeria, UN Doc. A/HRC/35/21/Add.1 (2017).

- 73. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 24, State Obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in the Context of Business Activities, UN Doc. E/C.12/GC/24 (2017).

- 74.Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Guiding principles on business and human rights. Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights; 2011. General Assembly, G.A. Res. 70/1 (see note 8) [Google Scholar]

- 75.The Abidjan Principles: Guiding principles on the human rights obligations of states to provide public education and to regulate private involvement in education. 2019.

- 76.Statement by the GPE board chair on the June 2019 board meeting. 2019. Available at http://www.globalpartnership.org/news-and-media/news/statement-gpe-board-chair-june-2019-board-meeting.

- 77.World Health Organization. Framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]; World Health Organization. International code of marketing of breast-milk substitutes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kembabazi A., Mtsumi A. How can we assess the impact of the private sector in health care on the realisation of the right to health? (Initiative for Social and Economic Rights). Available at http://www.gi-escr.org/publications/assessing-the-impact-of-the-private-sector-in-health-care-on-the-realisation-of-the-right-to-health.

- 79. General Assembly, Global Health and Foreign Policy, UN Doc. A/RES/67/81 (2013), paras. 3, 4.

- 80. See Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 24, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000).

- 81.Sumriddetchkajorn K., Shimazaki K., Ono T. et al. “Universal health coverage and primary care, Thailand,”. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 415;97(2019):422. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.223693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform. Sustainable Development Goal 3: Progress and info 2019. Available at http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3.

- 83. Ibid.

- 84.UNAIDS. “The AIDS response and primary health care linkages and opportunities”. (presentation at Global Conference on Primary Health Care, Astana, Kazakhstan, 2018). Available at http://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health-care-conference/aids.pdf?sfvrsn=189b259b_2.

- 85.Transparency International. Global corruption barometer Africa 2019: Citizens’ views and experiences of corruption. 2019. Available at http://www.transparency.org/files/content/pages/2019_GCB_Africa.pdf.

- 86.UNAIDS. Act to change laws that discriminate: Zero Discrimination Day, 1 March 2019. 2019. Available at http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019_ZeroDiscrimination_Brochure_en.pdf.

- 87. Ibid.

- 88.Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and World Health Organization. The right to health: Fact sheet no. 31. 2008. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Factsheet31.

- 89.International Monetary Fund. Corporate taxation in the global economy. 2019. Available at http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2019/03/08/Corporate-Taxation-in-the-Global-Economy-46650.

- 90.Center for Economic and Social Rights. New human rights and fiscal justice initiative calls for global corporate tax reforms. Available at http://www.cesr.org/new-human-rights-and-fiscal-justice-initiative-calls-global-corporate-tax-reforms.

- 91.Oxfam International. 5 Shocking facts about extreme global inequality and how to even it up. Available at http://www.oxfam.org/en/5-shocking-facts-about-extreme-global-inequality-and-how-even-it.

- 92. Ibid.

- 93.Sachs J. D. “Financing universal health coverage in low-income countries,”. Health: A political choice. 2019. in J. Kirton and I. Kickbusch (eds)

- 94.UN Environment. Nigerian Sustainable Finance Roadmap. 2018. Available at http://unepinquiry.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Nigerian_Sustainable_Finance_Roadmap.pdf.

- 95.World Health Organization. Stronger collaboration, better health: Global action plan for healthy lives and well-being for all. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 96. UHC2030. Available at https://www.uhc2030.org.

- 97.World Health Organization and Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Human rights, health and poverty reduction strategies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Examples to build on include. [Google Scholar]; Sida, World Health Organization, and Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Human rights and gender equality in health sector strategies: How to access coherence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 98. Puras (see note 18).

- 99.Das S. “Maternal health, human rights and the politics of state accountability: Lessons from the Millennium Development Goals and implications for the Sustainable Development Goals,”. Journal of Human Rights. 2018;17(5) [Google Scholar]

- 100.Saiz I. “Human Rights in the 2030 Agenda: Putting justice and accountability at the core of sustainable development governance,”. Spotlight on sustainable development 2019: Reshaping governance for sustainability. 2019. in B. Adams, C. Alemany Billorou, R. Bissio, et al. (eds)