Abstract

This article analyzes the ways in which rights-based arguments are utilized by anti-abortion activists in the UK. Drawing on an ethnographic study featuring 30 abortion clinic sites, anti-abortion marches, and other campaigns, we argue that rights-based claims form an important part of their arguments. In contrast to the way in which human rights law has been interpreted to support abortion provision, anti-abortion activists seek to undermine this connection through a number of mechanisms. First, they align their arguments with scientific discourse and attempt to downplay the religious motivation for their action. While this is an attempt to generate greater credibility for their campaign, ultimately, the coopting of scientific arguments actually becomes embedded in their religious practice, rather than being separate from it. Second, they reconfigure who should be awarded human rights, arguing not only that fetuses should be accorded human rights but also that providing abortion to women goes against women’s human rights. This article is important in showing how rights claims are religiously reframed by anti-abortion activists and what the implications are regarding debates about access to abortion services in relation to religious rights and freedom of belief.

Introduction

Across the UK, there has been a recent resurgence in anti-abortion activism outside abortion clinics, hospitals, and pregnancy advisory services. While the activities outside clinics have been happening for decades, more recently the number of people mobilizing against abortion has slightly increased and a greater number of clinics have been targeted.1 Almost all of the activists are religiously motivated, with religious displays the most common type of activity outside clinics.2 The difficulties experienced by those using services has led to campaigns for buffer zones surrounding clinics—areas free from activists—with the first one successfully being introduced outside a clinic in London in 2018. Despite the efforts of anti-abortion activists, support for abortion is strong in the UK, with more than 90% of people supporting access to abortion in at least some circumstances, and 70% advocating that it should be a choice for any reason.3 Moreover, abortion is provided free for all those who are eligible within the National Health Service (NHS), accounting for approximately 98% of all abortions.4

This article investigates the relationship between anti-abortion activists’ religious motivations and how they construct their views in relation to human rights discourses. First, we outline the general relationship between religion and rights-based discourses. Second, we demonstrate how data were gathered and how the findings were derived. Third, we outline how human rights claims and religious understandings are intertwined for UK anti-abortion activists. Lastly, we explore the implications for abortion rights claims if anti-abortion activism were understood as a specific religious practice.

As in other places, the UK is home to a range of anti-abortion organizations covering different activities. To name just a few: The Society for the Protection of Unborn Children (which claims to be the oldest anti-abortion organization in the world) was established in 1967 and focuses mainly on campaigning, political lobbying, and anti-abortion education. Life (which claims to have invented the term “pro-life”) was set up in 1970 to provide crisis pregnancy services, and it also conducts anti-abortion education. The main organizations involved in anti-abortion clinic activism are Helpers of God’s Precious Infants, the Good Counsel Network, the Centre for Bioethical Reform UK (often known as Abort 67), and, in Northern Ireland, Precious Life, although local groups also play an important role. In addition, some organizations take part in the biannual campaign 40 Days for Life, a US initiative that encourages local groups to stand outside abortion clinics for 12 hours a day for 40 consecutive days. Some of the organizations that target clinics, such as Precious Life, are also involved in other aspects, such as campaigning. The Alliance of Pro-Life Students provides support for a small network of university groups. Finally, March for Life UK is an annual event that seeks to bring together organizations and activists through running stalls, workshops, and a public demonstration.

Abortion, religion, and human rights

Increasingly, human rights law is being used to expand access to abortion.5 Human rights bodies have successfully used arguments regarding women’s equality and the rights to non-discrimination, health, autonomy, and liberty when advocating for the legalization of abortion, and many of these arguments have been upheld in national courtrooms and have contributed to progressive law reform.6 This provides an important backdrop for current anti-abortion activities.7 Indeed, the increasing use of a human rights framework by abortion rights advocates may have contributed to anti-abortion groups’ efforts to refocus their own frames of resistance and utilize rights-based claims aimed at restricting abortion. Joshua Wilson argues, in relation to the ongoing legal arena in the United States, how both the movement and countermovement are shaped by the tactical turn of the other.8 Once drawn into an arena, these movements develop capacity and expertise that then shapes future strategies.

The adoption of a human rights framing by anti-abortion groups builds on historic claims concerning the fetal right to life. While the first criminal statute was not passed in the UK until 1803, prior to this there were common law prohibitions and legal cases involving prosecutions for abortion.9 As John Keown has shown, during this history, there was some debate about the point at which the fetus was recognized as having legal protection, and there were considerable difficulties in distinguishing between abortion and other fetal losses, which meant that there was uncertainty over the issue.10 Nevertheless, some cases were brought against women and others, such as the prosecution of Margaret Webb for consuming poison with the intention of “destroying” a fetus in her womb in 1602.11 The common law position is likely to have built on earlier understandings from ecclesiastical courts, and thus religious beliefs were important in the formation of ideas about abortion, centered on the notion of ensoulment—that is, the point at which a fetus acquires a soul. Historically, quickening—the moment at which the fetus can be felt moving—was often taken to be a marker of ensoulment; terminating a pregnancy before quickening was not usually deemed problematic, while doing so after this point was.12

The right to life of the fetus was a significant issue in the debates during the passing of the 1967 Abortion Act, and it has continued to be an important point for those opposed to abortion. However, the medical framing of the abortion law means that attempts to restrict abortion have often not followed this line of reasoning.13 Since 1967, the attempts by anti-abortion groups and politicians have focused on, in their terms, reducing “abuses” and introducing other measures to restrict abortion. With one exception, all legal attempts to restrict abortion since the 1967 Abortion Act have failed.14 The only successful legal change, which happened in 1990, reduced the time limit for most abortions from 28 to 24 weeks; but at the same time, it clarified and extended the exceptional grounds for when abortions could take place at any time. This change did not significantly restrict services, as most later abortions were carried out for reasons covered by the exceptional grounds. While anti-abortion activists have not been successful in changing the law or reducing services, their constant attempts to restrict access and demonize service providers contribute to the ongoing stigmatization of abortion.15

Anti-abortion activists have long recognized that framing their opposition around religious objectives alone would not necessarily be a successful strategy. When the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children was established, it made a specific decision to be “secular” and to not have leaders who were Catholic, in order to tactically distance the organization from its religious roots.16 More recently, the public materials (for example, leaflets and website) of the Centre for Bioethical Reform UK make no direct references to religion, even if the majority of staff and volunteers are religiously motivated and one of the organization’s projects focuses specifically on encouraging churches to advocate against abortion. Hence, while religious belief has long been at the heart of the anti-abortion movement, anti-abortion groups have a long history of adopting “secular” frames to promote their arguments.

The number of people in the UK who describe themselves as religious is declining, and recent research has found that more than half of the population now states that it has no religion.17 Yet while fewer people are religious, those who are, Grace Davie suggests, take their religion more seriously.18 The majority of religious practitioners accept or support abortion in similar numbers to those without faith.19 However, anti-abortion activists are typically highly religious Christians, with the majority being Roman Catholic.20 Linda Woodhead specifies that 8.5% of the religious landscape in Britain is constituted as a “moral minority, typified by high levels of religiosity and deep conservatism on sexuality issues.”21 It is also important to note that while there is widespread tolerance of religion across the UK, it is tolerated only to the extent that it is low key and unobtrusive.22 In general terms, public displays of faith are frowned on, save for specific occasions such as Christmas, and even then, they are often more acceptable if they are understood as ecumenical and potentially even having a non-faith dimension.23 This prevailing attitude toward religions and religious practices means that many anti-abortion activities are considered to fall outside of generally accepted behavior on the basis of their faith-based public practice and their opposition to abortion. The lack of general support—among both those with a faith and those with none—to restrict abortion highlights the difficulties that anti-abortion groups face when seeking to frame their arguments.

Methodology

This article emerges from an ethnography of abortion debates in UK public spaces, which focused on public activism, especially around abortion clinics. Over a five-year period, we carried out observations at 30 clinic sites targeted by anti-abortion groups in a variety of large and small cities and towns. We visited many of the abortion clinics more than once, and our observations usually lasted between one and two hours. During observations, we took fieldwork notes on the geography, signs, and behavior of the anti-abortion activists and, when present, abortion rights groups’ counter-actions. We also took photographs of the activism, taking care not to photograph clinic users or staff. The notes and photographs that were taken during ethnographic encounters were later written up into formal research accounts.

In some places, organizations such as the Good Counsel Network are directly involved in organizing a clinic presence, whereas in other cases, organizations provide the necessary support for local grassroots groups to begin and sustain clinic activism (for example, Helpers of God’s Precious Infants). Across the UK, those taking part in clinic-based anti-abortion activities are overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, with a minority being Evangelical Christians. During the course of our fieldwork, we encountered only a few individuals who were not aligned with one or another religious tradition. Some sites have more than one group taking action, and individuals can be active in more than one group, which makes it difficult to ascertain who is “leading” the activities on any particular occasion. Typically, there will be two to four anti-abortion activists present, with larger groups of 30–50 on special occasions. The largest group we observed consisted of approximately 160 people outside a hospital in Glasgow in April 2019. Many of the groups have signs and religious iconography. At some sites, these elements are present throughout the activity, but in other places, individuals bring their own “displays” and remove them when their shift finishes.

Apart from sites organized by the Centre for Bioethical Reform UK, the anti-abortion activists were usually praying, either silently (often using rosary beads to pray the Rosary) or audibly in unison with others, occasionally singing hymns. On many occasions, direct approaches to women seeking abortion services would be made by “pavement counselors.” Whether or not direct approaches were made was related to the specific site and to the particular anti-abortion activists present. On hospital sites, for example, approaches were not usually made because the anti-abortion activists frequently had to stand outside the hospital grounds, meaning they could not easily identify those seeking abortion services. Most activists made individual decisions regarding what they actually did, such as whether to directly approach service users. This individual-based style also meant that the type of activism varied hour by hour, as those present at any given moment determined the form of activism. Some sites had activists present on a daily basis, whereas others had people present only for a few hours a week, or only during the 40 Days campaign. Moreover, even if anti-abortion groups signed on to the 40 Days campaign, the commitment to being present for 12 hours a day for the full 40 days was fulfilled only by a minority, demonstrating the challenges that anti-abortion activists face in achieving broader support.

We also conducted formal and informal interviews with a range of activists who provided their consent. Some interviews were conducted at the site of activism and varied in length from 10 minutes to nearly an hour. Other interviews were formally arranged away from the activism site, usually in a quiet café or the home of the participant. These interviews were normally recorded, centered on specific topics, and lasted as long as two hours. Both formal and informal interviews were designed to enable participants to raise points of interest and to explain their activism in their own words and at length. Due to the small numbers of anti-abortion activists in many locations, we cannot include demographic information, as this could potentially identify our participants and thus breach their confidentiality. In certain situations, we are also unable to provide details of the exact location of the activism, as this too would compromise confidentiality.

The dataset consisted of field notes from observations and informal interviews, transcriptions of formal interviews, and photographs. We also collected and analyzed materials such as leaflets that were being distributed at activist sites, focusing on both the written content and any accompanying drawings or photographs. In addition, we attended public anti-abortion events, including five annual “March for Life” events (three in Birmingham and two in London) and accompanying counter-demonstrations. We also gathered data at local government meetings, particularly in relation to the buffer zone debate. Finally, we added documents containing public statements made by activist groups to the data set, focusing on key moments such as council debates on buffer zones. The analysis of all textual data (such as transcripts, field notes, and documents) followed the thematic analysis principles of Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke.24 Initial coding was generated following close reading of the data, and these were then combined into broader themes. The photographs were used to add depth to the field notes, but also analyzed in relation to the themes emerging in the textual data. This article arises from the human rights theme, which contained data on when abortion needed to be stopped on the basis of rights-based claims.

Ethical approval was granted by Aston University. Ethical issues emerging throughout data collection centered on our position as researchers and on negotiating access to individuals suspicious or hostile toward our motivations. We wore university identification during fieldwork and highlighted our role as university researchers. Some activists robustly declined to speak to us; others wanted us to speak to the vigil or other organizational leaders instead of them. In our exchanges with participants, we tried to frame our interactions as an open inquiry, using a conversational style. Some groups had previously encountered hostile press coverage, creating concerns regarding our intentions. We stressed the academic nature of our investigation, as well as the importance of generating a range of views on the issue so that we could report on the activism as accurately and fully as possible. As both of us take a pro-choice stance, difficulties sometimes emerged when we were directly questioned regarding our own views on abortion, but we were always open about this and stressed that in the context of data collection, the activists’ views were more important than ours. Some took this as an opportunity to explain more fully their motivations for activism.

Findings

“It’s not just about religion”

Despite the majority of anti-abortion activities outside of abortion clinics having a religious component, many of the activists stated that religion was not necessarily their main motivation for being there. For example, one of the activists during a Lent 40 Days campaign outside of a clinic in central London in 2019 told us that she had been involved in anti-abortion activism for a number of years and also supported prayer vigils run by the Good Counsel Network. On that particular day, she was covering an early morning shift and was holding her rosary beads and reciting prayers with others. Next to her, propped up against the fence, was a candle, flowers, and a picture of Our Lady of Fatima, producing an altar-like display on the pavement (Figure 1). She explained that she had brought the items from her home. Yet despite both this individual religious framing and the overarching rationale of the 40 Days campaign to “pray to end abortion,” she stated that her opposition to abortion “wasn’t just about religion.” This sentiment was repeated frequently by those engaged in religious activities outside clinics:

Figure 1.

Pavement display in London, 2019

Even if I wasn’t religious I would still be really concerned to protect unborn children. (interview, Nottingham, 2017)

But for me, the bit that becomes more black and white philosophically is either you believe life starts with conception or you don’t. And if it’s not a baby … if it’s not a life, what is it? … I come at it probably less from a faith-based point of view and more from a philosophical point of view. (interview, Birmingham, 2016)

We suggest that framing their activism as being beyond religion is not simply a denial of the importance of their faith; rather, it indicates how everyday faith practices can be inclusive of other frameworks. As a form of lived religion—that is, how individuals themselves negotiate their religious practices—the anti-abortion activists interpret and shape religious doctrine into individualized beliefs and practices.25 Moreover, as we will show below, this includes potentially adopting “secular” understandings into their religious practices. In other words, while the activists themselves may suggest that their adoption of a “rights” or “equality” framework is separate from their religious motivations, the way that they engage and articulate these ideas demonstrates that they are shaped by their religious practice.

Unique “losses”

Generally speaking, the activists outside of abortion clinics accepted a “life from conception” position in which abortions should not take place under any circumstance. This position, for a few, stretched to denying that abortion was ever needed to save a woman’s life. For example:

Interviewer: But some women have to have abortions or they will die themselves?

Activist: I don’t know about that [doubtful tone, long pause]. Ireland has the highest, the most safest place to have a baby was Ireland, then they brought in abortion, because there is money to be made. (field notes, London, 2019)

The belief that the absence of abortion made Ireland safer was rooted in an understanding that abortion is an “unnatural” act and that abortion service providers are motivated by profit.26 In addition, on two recent occasions (Cheltenham 2019 and London 2018), we were told that it was “not true” that Savita Halappanavar’s death in Ireland in 2012 was due to the constitutional ban of abortion in place at the time, although the official report concerning her death indicated that her health care team did not offer best clinical practice because of concerns about the legal status of abortion.27 Understanding the activists’ position is made more complex by the doctrine of double effect, which states if the intention is good, an act is moral even if it has a bad outcome. This means that treating a woman for a life-threatening condition is permitted even if it causes the fetus to die, provided that the main “intention” is treatment rather than terminating the pregnancy. Using this premise, anti-abortion organizations have argued that it was not law but medical negligence that led to Halappanavar’s death. However, during our interviews, it was not clear if individuals specifically accepted the double-effect doctrine or if they simply accepted the overall messages from anti-abortion organizations that her death had nothing to do with the law.

From the activists’ “life from conception” position emerged an understanding that each fetus was a “unique” human being, and this was rooted in the adoption of scientific claims. They frequently mentioned that science “proved” that life began at conception, stating that each fetus has “individual DNA.” Examples include the following:

[I]t is not just a woman’s body, we are carriers when we carry children. It is in our body, our body, but it is a completely separate living entity with its own human DNA, its own bloodstream. (field notes, March for Life, 2016).

You realize that your [pro-abortion] view is going against science, the science of conception? (field notes, London, 2016)

One activist, who spoke passionately about religious teaching on abortion, sought to bring together claims about science, rights, and the relationship between mother and developing fetus by talking about equality. She argued that DNA proved that the fetus was human; and as a human, it has a right to equality, which was jeopardized by the promotion of abortion:

Age is an artificial construct. If we look at what is human, especially about biology … if it has human DNA and meets the test of being alive, it is human life and has a right to its own equality … They both have equality … The argument that abortion is anyway a promotion of equality is wrong, it promotes inequality between mother and child. That inequality exists, but not to the degree that you say the child has no rights. (interview, Midlands, 2018)

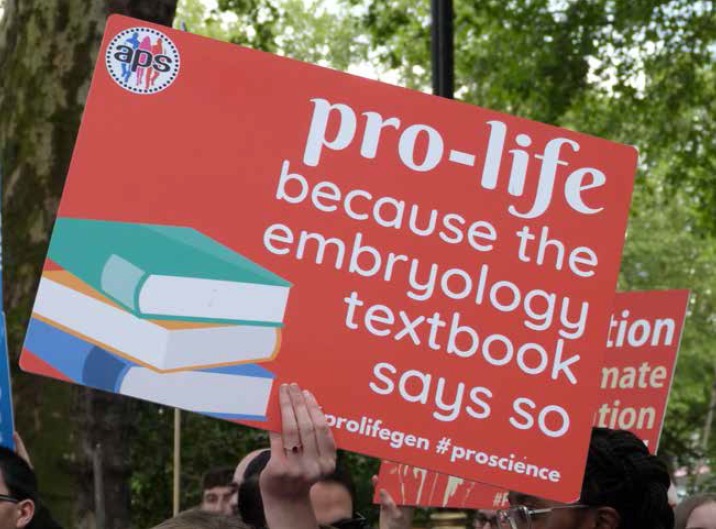

Some organizations go further in adopting “science” as the foundation from which “rights” may be claimed on behalf of the fetus. For instance, the Abort 67 website (now taken down) featured quotations from medical textbooks that discussed embryology and genetics, which the organization felt supported its claim that “science” determines when life begins. We observed this sentiment among members of the Alliance of Pro-Life Students, who had a number of placards at the 2019 March for Life making scientifically focused rights-based claims, including the phrase “Pro-life because the embryology textbook says so” (Figure 2). In this case, neither the sign nor the activist holding it referred to a specific book. On the one hand, utilizing scientific authority could be a means through which activists seek to appeal to a secular audience unconvinced by religious reasoning for opposing abortion. But on the other, such secular messages appeared indivisible from activists’ everyday religious framework, according to which every child was a “gift” from God and choosing to have an abortion was thus denying God’s will. This understanding was often underscored by reference to a Bible quote from Jeremiah 1:5 in public displays: “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you.”

Figure 2.

Alliance of Pro-Life Students sign during the March for Life, London, 2019

In short, anti-abortion activists’ foundation position is premised on a religious belief in which each pregnancy is a “gift”, and therefore abortion is contrary to God’s intentions. From this understanding, they interpret and incorporate ideas from “scientific” discourse into their everyday anti-abortion religious practices.

“Missing people”

The Vatican has utilized rights-based frameworks to endorse conservative notions of rights, such as the right to life, and this positioning can be located in Catholic discourse more broadly, particularly within anti-abortion narratives.28 The foundation position is that a “unique” life has been created. From there, the assignment of “rights” is, for the anti-abortion activists, a logical progression, and the number of abortions undertaken is then discursively positioned as “missing” people. For example, on the 50th anniversary of the UK’s Abortion Act, the Catholic Herald published an article entitled “The Bill That Wiped Out Millions.” The article described abortion as the “industrial destruction of human life,” noting that “the sanctity of human life has been thrown into open trash bins.”29

Given that the Catholic Herald is a religiously mediated periodical, the term “sanctity of life” clearly embraces a religious meaning, and it represents an idea counter to the “industrial,” which connotes large-scale, and possibly even polluting, levels of abortions. The fetal right to life given by God is “destroyed” by the secular world. This also came up in discussions with activists; one participant in Glasgow explained the importance of allowing everyone to be born, linking this to a personal story in which his grandmother had been left for dead at birth, but a health care professional had realized at the last moment that she was alive. He attached significance to the fact her own generational line had produced many children, who had all offered key service roles to the community in the health care professions and charity work, thereby underscoring the important contribution they had made.

Claims about equality and the right to life also allow the anti-abortion activists to make comparisons to historical situations featuring a denial of rights, such as slavery and the Holocaust. As one activist explained:

When people saw slavery, they had to put an end to it. When people see abortion, if they are convicted they will have to put an end to it. So I see it in the same level. There are people without rights, who need to be stood up for. It is exactly the same thing, it is no less. (interview, Birmingham, 2016, emphasis added)

The use of the term conviction in this quotation is important. As a theological idea, it means that God is encouraging one to change one’s behavior and therefore live a righteous path. In this case, it means that taking a stand against abortion becomes a demonstration of one’s sacred commitments to God.30 This quotation thus not only aligns the campaign against abortion with the campaign against slavery, but does so with a specific religious understanding. In both cases, human rights (the right of the slave and the right of the fetus) are understood as being revoked. The power of aligning the issue of abortion with slavery lies in a more universal understanding of slavery as an inherently bad thing, thereby appealing to more secular sensibilities—if one is against the evil of slavery, then one must also be against the “evil” of abortion. This position of aligning the two together is sacredly endorsed through the understanding that fighting them is a religious commitment. For the activists, changing the minds of others to oppose abortion becomes rooted in the very raison d’être of their religiosity, as this quotation indicates:

I don’t want Him [God], when I breathe my last breath … to say, “But what did you do about it?” I just go down to the abortion clinic, to satisfy my conscience really. I’m doing what I can. I could probably do more, actually, but at least I’m doing something. (interview, town south of England, 2017)

Therefore, by taking a stand, one is doing God’s work. This then causes tensions with those Catholics (the majority) who do not participate in anti-abortion activism. The activists saw this as problematic, and it was not uncommon for them to criticize others of faith and faith leaders for a lack of active participation in their campaign.

Reworking women’s rights

As we have described elsewhere, for the anti-abortion activists, womanhood and motherhood are religiously entwined. The activists therefore believe that abortion is always a result of pressure or coercion, as women would never “naturally” choose abortion.31 Positioning the fetus as a bearer of rights attracts the common refrain that women’s right to bodily autonomy is subsequently eroded. This was addressed by activists in a number of ways. One strategy was to reconstitute women’s rights into responsibilities (in the quotation below, the activist used “child” in the context of an abortion being considered):

Mothers and children are active in stages of development throughout that whole process. But not at the degree of development which you say the child has no rights. The responsibility of any adult towards a child during the development of the child from start to finish is one of protection and support. It’s not one of power. (interview, Nottingham, 2017)

In this way, when fetal rights are recognized, a woman’s rights are not overtly revoked but rather reworked in relation to her “unborn child.” There is slippage here in how the woman is addressed; calling the woman considering an abortion a “mother” is no accident. A woman’s role is inherently bound up with motherhood in these accounts, and abortion is seen as a threat to this “natural” inclination. Women have a “right” to be mothers. In addition, invoking the woman as a mother from the moment she conceives ensures that the particular expectations of maternal sacrifice are invoked, making the responsibilitization narrative more plausible.32 This was also supported in signs we saw at activist sites with slogans such as “Value motherhood, choose life,” accompanied by an image of a woman kissing a baby (Edinburgh, 2017).

The understanding that motherhood is both natural and under threat frequently underpinned activists’ claims that abortion is harmful. For example, at one public demonstration in Nottingham, participants held placards saying “Abortion kills babies and hurts women” and “Women deserve better than abortion.” In this way, abortion is framed as being inherently harmful to women and as a form of rights violation. One participant at another anti-abortion event said:

[A]s a woman myself, I am all for equal rights for empowering women and I think it is quite sad in a way that a lot of feminists fight so hard for abortion when the original feminist like Alice Paul described abortion as the ultimate exploitation of women. I don’t think abortion empowers women; I think it puts them in a horrible situation, a horrible position. (March for Life, 2016)

For this participant, and many others, motherhood is women’s role, meaning that abortion undermines women’s main purpose in life and thus their authentic selves. Consequently, abortion is seen as fundamentally anti-feminist, going against equal gender rights. In such discussions, abortion due to rape is also seen as fundamentally harmful to women:

Rape isn’t necessarily, to me, a reason to have an abortion. The baby hasn’t done anything wrong. The man has done something wrong who has raped … But why should the baby be punished by being killed? Then the mother’s body, in a way, is violated twice. First of all she’s raped and then a baby is ripped out of her. (interview, town south of England, 2017)

In such cases, women’s rights were understood as being affirmed through taking an anti-abortion stance.

Discussion

It’s hard to fight increasingly obvious science … This is why we are seeing a renewed crackdown on pro-life protests: they … represent the very inconvenient truth … A movement that thinks nothing of the very right to life can hardly be expected to cherish the right to free speech for its opponents.33

This quotation is taken from an anti-abortion article in the Catholic Herald opposing the imposition of buffer zones around abortion clinics. It illustrates two themes we have analyzed within the rights-based claims of anti-abortion groups: their incorporation of science into their claims and their belief that support for abortion involves ignoring or destroying rights, including the rights of women themselves.

Despite their strong reliance on religious iconography and practices, many of the activists sought to downplay their religious motivations, stating that their opposition to abortion is based on understandings of human rights and equality rather than on religious teachings. In other words, they explained that they would actively oppose abortion regardless of whether they were religious. The explicit utilization of secular-based equality and human rights claims, we argue, cannot be understood simplistically as a strategic choice aimed at appealing to a secular audience. Instead, it should be understood as being adopted and incorporated into activists’ very religious practice. Indeed, while science and religion have often been considered as two oppositional frameworks, our findings demonstrate the way that the secular and the religious become entwined.34 Nonetheless, the way that these two elements are woven together is complex.35

Focusing on the everyday lived practices of religion reveals the ways in which individuals are active in constructing religious meanings in their lives.36 As Meredith McGuire argues, the experiences of individuals of faith are different from the beliefs that are defined at an institutional level, and in everyday practice, individuals incorporate and disregard official teachings in various ways.37 In other words, for people of faith, involvement in the anti-abortion movement needs to be understood as a central element of their religious practice, and this is also likely to be important in the way that they understand themselves as religious people. Opposing abortion is a means of demonstrating their religious identity, even though their active opposition to abortion places them within a religious minority.

The use of science and other secular narratives within anti-abortion campaigns has often been documented as arising from a religious position.38 We argue here that the relationship between secular frames and religious beliefs of the anti-abortion movement is complex. As our analysis shows, “secular” understandings of the “science” of conception appear to be reshaped and used as part of anti-abortion activists’ lived practice of religion. The idea of the “unique” person—identified though individual DNA—is easily interpreted within their understanding of each fetus being an individual gift from God. While they are comfortable with the use of a science frame to promote a belief in life from conception as an “obvious truth,” our analysis suggests that the activists may not necessarily recognize that this understanding is informed by and incorporated into their religious practice. Understanding religion as a lived practice that allows a “flexible” pathway of belief enables the incorporation of scientific “facts” such as the uniqueness of DNA to be read through a religious lens. Research in other areas has shown how potentially challenging scientific ideas can be coopted rather than rejected.39 Religious practice is (re)interpreted and (re)constructed in relation to issues that are particularly pertinent to a specific faith position.40 However, the religious (re)interpretation of the science of DNA may not have had the universal appeal that anti-abortion groups are hoping for.

We have demonstrated elsewhere that activists’ opposition to abortion is rooted in essentialized constructions of womanhood in which motherhood is the only “natural” role for women, based on conservative religious understandings of separate spheres and gender complementarity.41 This understanding shapes their actions, regardless of whether they choose a religious approach or adopt more “secular” scientific messages.42 Their religious ideas, such as regarding women’s “natural role” as mothers, form an important part of their opposition to abortion.43 In relation to rights claims, the activists work these ideas into a position where abortion itself poses a threat to women’s rights, even in cases such as rape, and where abortion is seen as never being really medically necessary. This challenges the positioning of abortion as a woman’s fundamental human right, as advocated by human rights bodies.

Our findings add an important new dimension to the ways in which the rights claims of anti-abortion groups are understood. While the narratives used by those opposed to abortion may adopt the secular language of rights claims, their arguments do not simply build on their religious beliefs—instead, they constitute those very religious beliefs. This is also illustrated in their rejection of the term “protest” in favor of “prayer vigil” to describe their activities outside abortion clinics.44 Recognizing anti-abortion views as a religious practice rather than just a religious strategy raises both challenges and opportunities. The right to hold individual religious beliefs is, and should be, supported, which raises questions about the extent to which there should be attempts to change anti-abortion views. However, as articulated in Dulgheriu & Anor v. The London Borough of Ealing (2018), a case centering on a legal challenge to the UK’s first buffer zone, freedom of belief is a qualified right that can be curtailed to protect the freedom of others.45 The key point of this judgment is that while activists have a right to hold anti-abortion views, this right should not extend to being able to constrain abortion or intervening when women are accessing abortion services. There is an important distinction between the holding of individual beliefs and appropriate ways to demonstrate and try to convert others. The space outside service providers is not seen as an appropriate space for anti-abortion religious practices. Recognizing anti-abortion activism as a religious practice, and thus an individual belief, could therefore actually encourage the protection and enhancement of abortion access by fostering recognition that there is both sacred and secular pluralism and that the beliefs of some should not curtail the rights of others.

References

- 1.Lowe P., Hayes G. “Anti-abortion clinic activism, civil inattention and the problem of gendered harassment,”. Sociology. 2019;53(2):330–346. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowe P., Page S-J. “‘On the wet side of the womb’: The construction of mothers in anti-abortion activism in England and Wales,”. European Journal of Women’s Studies. 2019;26(2):165–180. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swales K., Taylor E. A. British social attitudes 34. London: National Centre for Social Research; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Social Care. Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2017. 2018.

- 5.Rebouché R. “Abortion rights as human rights,”. Social and Legal Studies. 2016;25(6):765–782. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ibid.

- 7.Baird B. “Decriminalization and women’s access to abortion in Australia,”. Health and Human Rights. 2017;18(1):197–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson J. C. The street politics of abortion: Speech, violence, and America’s culture wars. Stanford Law Books; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keown J. Abortion, doctors and the law: Some aspects of the legal regulation of abortion in England from 1803 to 1982. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ibid.

- 11. Ibid.

- 12. Ibid.

- 13.Amery F. “Solving the ‘woman problem’ in British abortion politics: A contextualised account,”. British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 2015;17(4):551–567. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ibid.

- 15.Lee E., Sheldon S., Macvarish J. “The 1967 Abortion Act fifty years on: Abortion, medical authority and the law revisited,”. Social Science and Medicine. 212(2018):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hindell K., Simms M. Abortion law reformed. London: Peter Owen; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Swales and Taylor (see note 3).

- 18.Davie G. Religion in Britain: A persistent paradox. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Swales and Taylor (see note 3).

- 20. Lowe and Page (see note 2).

- 21.Woodhead L. Religion and personal life. London: Darton, Longman and Todd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davie (see note 18).

- 23.Engelk M. “Angels in Swindon: Public religion and ambient faith in England,”. American Ethnologist. 2012;39(1):155–170. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun V., Clarke V. “Using thematic analysis in psychology,”. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGuire M. Lived religion: Faith and practice in everyday life. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lowe and Page (see note 2).

- 27.Health Service Executive. Investigation of incident 50278 from time of patient’s self referral to hospital on the 21st of October 2012 to the patient’s death on the 28th of October, 2012. 2013.

- 28.Morgan L. M. “Reproductive rights or reproductive justice? Lessons from Argentina,”. Health and Human Rights Journal. 2015;17(1):136–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alton D. “The bill that wiped out millions,”. Catholic Herald. 2017. p. 20.

- 30.Harding S. F. “Convicted by the holy spirit: The rhetoric of fundamental Baptist conversion,”. American Ethnologist. 1987;14(1):167–181. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lowe and Page (see note 2)

- 32. Ibid.

- 33.Condon E. “Public enemies?,”. Catholic Herald. 2018. p. 21.

- 34.Martin D., Catto R. Religion and change in modern Britain. London: Routledge; 2012. “The religious and the secular,”. in L. Woodhead and R. Catto (eds) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butler E. “God is in the data: Epistemologies of knowledge at the creation museum,”. Ethnos. 2010;75(3):229–251. [Google Scholar]

- 36. McGuire (see note 25).

- 37. Ibid.

- 38.Wyatt D., Hughes K. “When discourse defies belief: Anti-abortionists in contemporary Australia,”. Journal of Sociology. 2009;45(3):235–253. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Butler (see note 35).

- 40. McGuire (see note 25).

- 41. Lowe and Page (see note 2).

- 42. Ibid.

- 43. Ibid.

- 44. Lowe and Hayes (see note 1).

- 45. Dulgheriu & Anorv. The London Borough of Ealing [2018] EWHC 1667 (Admin) (02 July 2018). Available at http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2018/1667.html.