Abstract

Objectives:

This study explores the relationships of individualistic (e.g., competition, material success) and collectivistic values (e.g., familism, respect) with risky and prosocial behavior among African-American and European-American youth. While previous work has focused upon immigrant adolescents, this study expands the research exploring cultural values to other racial-ethnic groups and to a younger developmental period. This study builds upon culture as individually experienced beliefs and practices, potentially espousing multiple cultural orientations and relationships to behavior.

Methods:

Data from Cohort 3 of a study of 219 urban, suburban, and rural children included African-American (42%) and European-American(58%) children, 54% female, ranging from grades 1–5 (mean age = 9). Multigroup structural equation models were tested resulting in a measurement model that fit similarly across groups (RMSEA=.05, CFI =.94).

Results:

African-American children reported higher levels of individualism, and African-American and European-American children reported espousing similar levels of collectivism. Children in higher grades were found to be more collectivistic and less individualistic. Individualistic values were related to children’s lower prosocial and higher rates of problem and delinquent behavior. Collectivistic cultural values were associated with reduced rates of problem behaviors, controlling for race-ethnicity, gender and grade.

Conclusions:

Results provide support for the assertion that youth espouse multiple cultural orientations and that collectivistic cultural values can serve as promotive factors for children of diverse backgrounds. Practice and policy should seek to understand the role of family, school, and community socialization of multiple cultural orientations and nuanced associations with risk and resilience.

Keywords: Cultural values, Collectivistic, Individualistic, Pro-social behaviors, Problem and Risky behaviors

The Role of Cultural Values in Problem and Prosocial Behavior among African-American and European-AmericanChildren

With the demographic shifts in the United States, there has been increased attention given to the influence of cultural and ethnic factors upon children’s developmental outcomes (Cabrera et al., 2013; García-Coll et al., 1996; Hill, 2006; Spencer, Dupree, & Hartmann, 1997). Indeed, the U.S. has an increasingly diverse citizenship. Overall, European-Americans continue to be the largest racial-ethnic group accounting for 76.6 percent of all people living in the U.S. African-Americans represent 13.4 percent, Asians 5.8 percent, Latino/Hispanics of all races represent approximately 18.1 percent, and 4.2 percent are classified as Amerian Indian, Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and those with two more races (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Additionally, there are approximately 13.2 people in the U.S. who are foreign born. Decades of scholarship have been devoted to examining the modalities by which arriving families retain their native cultural values and begin to adopt the host culture (Myrdal, 1944; Rumbaut & Portes, 2001). Adaptation of various immigrant groups have been compounded by their “voluntary” (by choice) and “involuntary” (by slavery or annexation) immigration to the U.S. (Ogbu,1981). These diverse histories, patterns, and the transgenerational transmission of cultural values continue to be salient.

Models of acculturation and enculturation are informed by immigrants who with each subsequent generation, embark on a process of integrating the values of their native country with the host culture. These pathways for adapting to the host culture include: assimilation - the declining significance of one’s native culture and increasing adoption of the host culture; integration - a multicultural identity embracing aspects of both the native and host cultures; separation - resistance to the host culture and retention of only the native culture; and marginalization/isolation - disconnection from the host or native culture. Acculturative processes have been found to vary with the age of migration to and generational status in the U.S. (Berry, Phinney, Sam, Vedder, 2006; Halgunseth, Ispa, & Rudy, 2006; Rumbaut & Portes, 2001). Cultural-ecological models emphasize the influential role of adaptation not only for problem behaviors, but also for positive child development, particularly among racial-ethnic minority groups (Cabrera et al., 2013; García-Coll et al., 1996; McLoyd, 1990; Ogbu, 1981).

This paper focuses upon culture conceptualized as shared beliefs, values, customs, and practices that embody the implicitly or explicitly shared ideas about what is good, right, and desirable in a society (Triandis, McCusker, & Hui, 1990; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998; Williams, 1970). Cultural values are viewed as “the bases for the specific norms that tell people what is appropriate in various situations” (Schwartz, 1999, p. 25). Though less work attends to cultural processes for children born in the U.S., the current study draws upon a cultural-ecological perspective (Ogbu, 1981) to explore cultural values among African-American and European-American children who are more often defined by their presumed race (physical phenotype) than by their ethnicity (sense of culture, heritage, or nativity) (Hughes et al., 2006; Perry, 2001). We use both terms in this paper to acknowledge that race and ethnicity can be intertwined in complicated ways (Boykin, 1986; Martin, 1991; Perry, 2001).

Researchers suggest that societies differ in the degree to which collectivistic and/or individualistic values exist within a given culture (Tamis-LeMonda, et al., 2007; Triandis, McCusker, & Hui, 1990; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998; Pilgrim & Reuda-Riedle, 2002). Collectivist societies are understood in terms of the in-group defining and influencing the social behavior of its members with an emphasis on shared experiences, and supporting in-group members (Brewer & Chen, 2007; Kim, Triandis, Kâğitçibaşi, Choi, & Yoon, 1994; Pilgrim & Reuda-Riedle, 2002). Identification and solidarity are expected from individuals deemed part of the group, and evaluation of one’s actions is tied to the consequences for the in-group (Brewer & Chen, 2007; Pilgrim & Reuda-Riedle, 2002). Conversely, individualism is related to the evaluation of one’s actions in terms of consequences for the individual. Within more individualistic societies, the emphasis is on uniqueness, independence and competition; personal goals are considered more important than in-group goals (Triandis, McCusker & Hui 1990; Pilgrim & Reuda-Riedle, 2002).

Studies of cultural values frequently include measures of collectivistic (e.g., familism, respect) and individualistic (e.g., competition, material success) values (Kâğitçibaşi, 1997; Triandis, McCusker, & Hui,1990). This research has demonstrated that certain cultural values (e.g., family obligation) may promote positive development and buffer children from the negative effects of poverty and other stressors (Calzada, Tamis-LeMonda, & Yoshikawa, 2013). Espousing a family orientation or sense of familism emphasizes closeness, support, and obligations within the family (Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, VanOss, Perez-Stable, 1987; Schwartz et al., 2013, Schwartz et al., 2014; Steidel & Contreras, 2003; Updegraff, McHale, Whiteman, Thayer, & Delgado, 2005).

Fuligni and colleagues examined attitudes toward family obligation among hundreds of first- and second-generation adolescents in several studies (Fuligni, 2001; Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999; Fuligni, Yip, & Tseng, 2002; Hardaway & Fuligni, 2006). In this program of research, they found that Asian and Latino adolescents retained their parents’ familistic values, particularly stronger family obligation values and greater expectations regarding their duty to assist, respect and support their families than did their peers of European-American backgrounds. Tseng (2004) found in a large sample of American early adults with Asian Pacific, Latino, African/Afro-Caribbean, and European backgrounds that those who valued family obligations considerably were more motivated academically, but high family behavioral demands evidenced deleterious effects on academic achievement. While valuing family obligations is motivating to immigrant youth, family stress can hinder success. Yet, daily diary studies have revealed that it is possible to navigate multicultural spaces in ways that maintain well-being (Fuligni et al., 2002).

While this research points to the importance of familism for youth born outside of the U. S., it would be inappropriate to conclude that family, specifically family closeness, is not important for U.S.-born youth of European heritage. Hardaway and Fuligni (2006) found European-American adolescents to be similar to their Asian and Latino peers on family identification and dyadic closeness. For Chinese-, European-, and Mexican-American youth, family interactions and closeness was an important factor in disclosure to their family, and reduced susceptibility to peer drug use (Kam & Yang, 2014; Yau, Tasopoulos-Chan, & Smetana, 2009). On the other hand, family obligation was related to youth disclosure of behavior for Chinese - and Mexican-American but not European-American adolescents (Yau, Tasopoulos-Chan, & Smetana, 2009). Thus, different dimensions of family processes emerge as salient for various racial-ethnic groups.

In other research comparing immigrant and U.S.-born youth, Phinney, Ong, and Madden (2000) found Armenian, Vietnamese, and Mexican recent immigrants rate family obligations as significantly more important than African-American U.S.-born youth, who rated family obligations higher than their European-American U.S.-born counterparts. However, this cannot be construed to mean that European-Americans are singularly individualistic. For example, Wang and Tamis-Lemonda (2003) conducted a study that examined the cultural values of parents living in the urban cities of Taiwan and the U.S. and they found that non-Latino, European-American parents emphasized some aspects of individualism but also rated connectedness as important. This research offers some nuanced support for the values of family connectedness and to a lesser degree, family obligation among European-American individuals and more support for these values among immigrant children and youth of color. Nevertheless, the cultural orientation of parents can include a mix of values held dear to them and transmited to their children.

Though not always studied under the conceptual framework of familism, there is scholarship dedicated to understanding the importance of kinship, family bonds, and mutual interdependence among African-American families (Billingsley, 1994; Boykin, 1986; Hill, 1999; Nobles, 1991; Sudarkasa, 1998). So often when African-Americans are discussed in the U.S., it is in terms of their presumed race (i.e. physical appearance or phenotype), and not ethnicity or culture (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996). Indeed, the shift in nomenclature to “African-American” was to situate this group in terms of their “involuntary immigration” from countries and cultures of origin (Martin, 1991; Ogbu, 1981). Though an area of controversy, classic work by anthropologists and historians have refuted the premise that the slavery experience resulted in the demise of African-American cultural retentions (Genovese, 1976; Gutman, 1976; Herskovits, 1990). In an effort to understand the cultural realms in which African-Americans find themselves, Boykin (1986) conceptualized the triple quandary theory including; 1) “mainstream” experience, i.e., more individualistic and competitive beliefs and values common to the majority culture within the U.S.; 2) the “minority” experience that refers to coping strategies and defense mechanisms developed in response to oppression and social stratification; and 3) the “Afro-cultural experience” that refers to cultural aspects such as a value for kinship and extended family ties.

In empirical studies of cultural values with African-American adolescent girls, Constantine, Alleyne, Wallace, and Franklin-Jackson (2006) found that collectivistic values operationalized as collective work and responsibility, cooperative economics, and self-determination, were associated with higher levels of self esteem, perceived social support, and life satisfaction. The results from this study exemplified the process by which collectivistic and individual cultural value orientations may be functional or complementary with support from the group fostering individual development of the girls (Constantine et al., 2006; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2007). Thomas, Townsend, and Belgrave (2003) found that collectivistic values (e.g., spiritual orientation, and extended family kinship connections) were associated with higher psychosocial adjustment including more positive racial-ethnic identity, greater self-esteem, and more positive teacher ratings of child behavior. In a study of the cultural values of African-American upper elementary-age children, students and their parents had significantly stronger preferences for cultural and communal activities at home and at school than for individualistic and competitive activities. However, perceived teacher classroom preferences were significantly higher for individualistic and competitive activities; underscoring the importance of multiple cultural orientations predominant across various contexts (Tyler, Boykin, Miller, & Hurley, 2006). Individualistic and collectivistic cultural values may function relative to various situational contexts.

Waterman (1981) has argued that some degree of individualism, particularly freedom and the ability to choose, is critical to developing autonomy and agency. In cross-national data of respondents from dozens of countries on multiple continents, individualism has been found to be strongly correlated with subjective well-being and happiness (Diener, Diener & Diener, 1995; Veenhoven, 1999; Diener & Diener, 2009; Eckersley & Dear, 2002). In studies of adolescent respondents, Schwartz et al. (2013) found psychological well-being was positively linked with individualistic values and negatively associated with collectivistic values across gender, first-generation and second-generation immigrants, and the six ethnic groups included in the sample (European-American, African-American, Latino/a, East/Southeast Asians, South Asians, and Middle Easterners). Thus, some focus on the self has been found to be helpful to well-being. Research conducted by Lam and Zane (2004), among European-American(n=79) and Asian-American participants (n=79) ages 17–44 years old, indicated that European-Americans were more individualistic and scored higher in primary control construals (i.e., changing the existing environment to fit the individual’s need) versus secondary construals (i.e., the individual’s feelings and thoughts adjust to the objective environment). Research with African-Americans has supported the beneficial function of an individualistic orientation, particularly in terms of “effort optimism,” that is, a belief in hard work and sacrifice, and children’s motivation to achieve (Jagers, 1998; Lewis, Sullivan, & Bybee, 2006). Thus, some degree of individualism might be functional in the development of a sense of well-being and motivation.

On the other hand, a strong individual focus has also been found to be linked to less optimal outcomes. In international research, using data from the World Health Organization (WHO) across 11–22 Western and non-Western countries, individualistic values were linked to higher rates of suicide, especially for males, (Eckersley & Dear, 2002). Another potential aspect of individualism includes a materialistic ethos concerned with the acquisition of goods and maximization of profit. Studies have found that people oriented in this way report diminished well-being (Kasser & Ahuvia, 2002) across various age groups and in several cultures around the world (Cohen & Cohen, 1996; Schor, 2004). Second, adolescents high in materialism report more anti-social activities (Cohen & Cohen, 1996; Kasser, Ryan, Couchman, & Sheldon, 2004). These results suggest that an inordinate focus on the self is not adaptive.

Though there is some research to suggest differences in cultural values by race-ethnicity, this variation is not always in predictable directions. In a nuanced meta-analytic study, European-Americans scored higher on Triandis and Gelfand’s (1998) more vertical aspects of individualism (e.g., competition and personal achievement), whereas African-Americans scored higher in horizontal individualism (aspects of uniqueness and autonomy) (Vargas & Kemmelmeier, 2013). In yet another meta-analysis, African-American, Asian, and Latino youth were found to be more collectivistic than European-Americans (Coon & Kemmelmeier, 2001) but, African-Americans were higher than Asian and European Americans in terms of individualism. Thus, as these studies suggest, variation in cultural values may be due to living in a multi-cultural society in which people interact and influence each other in their multiple contexts.

Scholars recognize the problems inherent in placing individualism and collectivism into an overly simplistic dichotomy (Pilgrim & Reuda-Riedle, 2002; Tamis-LeMonda et. al, 2007). While some may presume that individualistic and collectivistic values are orthogonal, these values may not be mutually exclusive; both types of values may be espoused within the individual, family, or society (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2007), particularly in a multi-cultural society (Guerra & Smith, 2006). Tamis-LeMonda and colleagues (2007) assert that orientation to individualistic and collectivistic values can be presented along a continuum, and may vary contextually. For example, more individualistic values may manifest at school, while more collectivistic values might manifest at home, in neighborhoods, or faith communitites. While these values may seem opposing, they are not necessarily in conflict with each other. Yamada and Singlelis (1999) found that people who were raised in a collectivistic culture and lived in an individualistic culture for several years, were high in both value orientations, were better adjusted, and could deal with adversities more successfully.

Nevertheless, aspects of cultural value orientations can be conflicting (interfere with each other), additive (both goals are endorsed) or functional (goals of each value orientation may facilitate each other) (Tamis-Lemonda et al., 2007). We contend that children living in a multi-cultural society, exposed to diverse cultural orientations, may espouse both collectivistic and individualistic values at the individual level, though they may live in an overarching culture that may be more predominantly individually or collectively focused and vice versa (Ipsa et al, 2004; Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). Ecological theories often relegate culture to the ‘outer ring’ of their concentric circles; constraining the influence of culture on children’s development as more distal through its influences on society, policies, and media, which in turn influence families and communities. However, as individuals experience culture, it is a construct that is personal, up-close, and often a proximal influence, affecting daily individual or family practices (Vélez-Agosto, Soto-Crespo, Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer, Vega-Molina, & García Coll, 2017).

Summary and Research Aims

In the U.S., a country of people from diverse racial-ethnic and cultural backgrounds, previous research has found collectivistic values such as familism and communalism to be beneficial to immigrant and racial-ethnic minority populations, though exorbidant family demands can be stressful and less adaptive. The available research on European-American youth indicates some value of family closeness, though family obligations are less salient for this group. It is important to acknowledge that there is diversity among youth who emanate from across Europe and vary in the importance of family, culture and ethnicity. Subsequent generations of immigrants from Europe may not even think of themselves primarily in racial, ethnic, or cultural terms; Perry refers to this as the “invisibility” of race and culture for young people of European heritage (Perry, 2001). Race, culture and ethnicity might be more salient to European-American children contingent upon whether they are in a context in which they are the numerical minority (Perry, 2001).

Previous research on African-Americans born in the U.S. affirms their espousal of collectivistic values emphasizing family closeness, community bonding and solidarity but they also espouse some individualistic values, particularly pertinent to the “horizontal” values of autonomy. As research moves away from artificially dichotomizing cultural values, we recognize that some focus on the individual is related to well-being while an inordinate focus on material success has been found to be related to behavioral problems. These findings reflect the complexity of culture in which youth may espouse values, beliefs, and practices from multiple cultural orientations that vary across contexts in ways that are potentially complementary or conflicting (Boykin, 1986; Tamis-Lemonda et al., 2007; Triandis, 1990).

Whereas the vast majority of this work in the U.S. has been conducted with immigrant adolescents, elementary-age children are an often overlooked population. Examining children in young and middle childhood is important because “early starters,” those who evidence problem behaviors in early and middle childhood, are at increased risk for delinquency or drug use and generally require more comprehensive interventions (Alltucker, Bullis, Close, & Yovanoff, 2006; Milton, Woods, Dugdill, Porcellato, & Springett, 2008; Patterson, Forgatch, Yoerger, & Stoolmiller, 1998; Sprague & Walker, 2000). Being aware of one’s racial-ethnic group is a developmental task and cultural values may be salient for children even before adolescence (Aboud, 1988; Caughy, Nettles, O’Campo, & Lohrfink, 2006; Quintana & Vera, 1999; Smith, Levine, Smith, Prinz, & Dumas, 2009; Thomas et al., 2003; Tyler et al., 2006). Given the paucity of research on cultural values among elementary school-age children, the primary aim of this study was to examine how collectivistic and individualistic value orientations may be related to risky behaviors and prosocial behaviors among less studied groups of African-American and European-American school age children.

The current study examines cultural value orientations of elementary-age children across age/grade, gender, race-ethnicity and how these factors might be related to prosocial and problematic behavior. The specific aims of the current study were as follows: 1) examine the cultural values of individualism (material success, competition, and personal achievement) and collectivism (familism and respect) for African-American and European-American elementary-age children; 2) examine whether cultural values (collectivism and individualism) vary with children’s race-ethnicity, gender, and grade level (as a proxy for age); and 3) explore the degree to which collectivistic and individualistic cultural values are associated with behavioral outcomes (i.e., conduct problems, emotional symptoms, problem behavior, and pro-social behavior) for children who vary in gender, grade, and race-ethnicity.

Method

Participants

The current data is from Cohort 3 of the LEGACY Together Project, collected in 2011–12, including a sample of 302 1st-5th grade elementary school-aged children recruited from 32 afterschool program sites. On average, these afterschool programs were relatively diverse; 16.30% African Amerian, 65.98% European American, 12.05% Latino/a, 3.25% Asian, and 2.42% other-identified. These afterschool program sites were housed in 75 schools that varied in level of urbanicity (8% rural, 61% suburban, and 29.3% urban i.e., based on Phan and Glander (2008). Also, the neighborhoods in which these afterschool programs were implemented varied in their level of disadvantage (Range: −0.95 – 2.50), which is a standardized index of census-based poverty indicators (i.e., poverty, unemployment, less than high school education, female-headed households, residential instability.)

The participating children self-identified as 30% African-American, 47% European American, 6% Latino/a, and 17% mixed race-ethnicity or other; 54% female; and were 7–11 years old (Mean age = 8.50, SD =1.10). The sample (n=68) of Latino and mixed race youth was too small for separate analyses; as such, this study focuses on the African-American and European-American children only. Additionally, 15 children were excluded from the current study due to missing data on key study variables. Therefore, the current study includes 219 children, 55% female, 42% African-American and 58% European-American(58%), and the mean age is 8 years old (SD = 2.38).

Procedures

Consent for parents of children was obtained via letters sent to the home from the afterschool programs to which they could decline their child’s participation at any time and their data would be deleted; children were asked to assent prior to conducting the survey. The research team provided password-protected, personal digital assistants (PDAs) for survey completion, which took approximately 45–60 minutes. To make the process more developmentally appropriate and maintain children’s attention to the surveys, joke and cartoon breaks were built into the PDAs after each 15-minute section. The survey focused on various dimensions of youth self-perceptions, behavior, and community context, in addition to sections examining youth cultural orientations, the focus of the current study. All study procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The following sections describe the measures. Demographic data were collected and consisted of child gender (0 = boy, 1 = girl), grade (0 = 1st - 3rd, 1 = 4th - 5th), age, and race-ethnicity (0 = African-American, 1 = European American).

Cultural values.

The Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (MACVS) was used to assess cultural values of individualism and collectivism among Mexican American families in a longitudinal study in Arizona (Knight et al., 2009; Knight, Mazza, & Carlo, 2018). The current study is the only one we could identify using an African-American and European-American sample with this tested and reliable instrument. Four subscales from the MACVS were used to assess individualistic values (competition and personal achievement, n = 4 items; material success, n = 5 items) and collectivistic values (family obligation, n = 5 items, respect, n = 8 items). With our sample, the measure demonstrated acceptable reliability (Cronbach alpha’s ranging from .71 - .86) for the subscales of respect (.86 for African-Americans and .87 for European Americans), familism (.87 and .78 respectively), competition, (.73 and .68), and material success (.82 and .84). Further psychometric information is provided later when discussing construct validity.

Child behavioral outcomes.

Children’s socio-emotional and behavioral outcomes were assessed using child reports of the Strengths, Difficulties, Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, Meltzer, & Bailey, 2003; Mellor, 2004). The SDQ is comprised of 27 items to which participants responded on a 3-point scale indicating the degree to which each item is “not true, sometimes true, or very true.” We modified two of the original 25 items to make the items clearer and unambiguous for elementary children (Mellor, 2004). The SDQ sums and averages the scores on the items resulting in a total score and subscale scores on conduct problems, emotional symptoms, and prosocial behavior.

The conduct problem scale (Mean = 1.42, SD = .41; α = .58) included five items (e.g., I get very angry and often lose my temper). The emotional symptoms scale (Mean = 1.57, SD = .50; α = .78) included six items (e.g., I worry a lot). The prosocial behavior scale (Mean = 2.52, SD = .48, a = .80) included six items (e.g., ‘I try to be nice to other people” and “I care about their feelings”). All subscales demonstrated adequate to high reliability and the child-reported SDQ has been found to be congruent with parent reports (Mellor, 2004).

Problem behaviors and substance use were assessed by a developmentally-appropriate self-report measure obtained from Loeber and colleagues’ Pittsburgh longitudinal study of delinquency (Russo et al., 1993). These items begin by asking children if they know how and where to obtain fairly mundane items like apples or money, progressing to riskier items like cigarettes or alcohol. The subsequent five items, and focus of the current study, assess involvement in experimenting with substances and problem behaviors to which youth could respond yes or no. Items included theft (taking things from others that don’t belong to you), vandalism (destroying or damaging something that doesn’t belong to you), smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, and experimenting with marijuana. A count variable was created measuring the total number of problem behaviors for which children reported an affirmative response. Scores ranged from 0 to 7 (Mean = .83, SD = 1.22).

Data Analysis

Missing data analyses were conducted on all variables of interest and showed that only 6% or less of the data was missing on most variables for this sample; approximately 5% of the data was missing for the problem behavior measure. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used for all analytical models in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). No significant race-ethnicity, gender, or grade level differences were observed between the children that responded and did not respond to the measures of interest.

Results

First, exploratory factor analyses (EFA) (SPSS v.22) using principal axis factoring (PAF) and varimax rotation was performed on a 22-item MACVS measure without any constraints. In the initial analyses, the scree plot indicating the number of factors and associated eigenvalues, a proxy for variance accounted for by the factor, suggested a 3 or 4 factor model. The 3-factor EFA suggested 3 factors with most loadings above .40 representing 1) the respect and familism subscales; 2) the material success subscale and one item from the competition and personal achievement subscale; and 3) the competition and personal achievement scale with only two items with loadings over .40. Given that a factor needs to have at least three variables to be considered a factor (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007), factor 3 was considered meaningless. We then conducted a 2-factor EFA (see Table 1). Factor 1, collectivistic values was comprised of the same items as before (i.e. respect and familism) and explained 32% of the variance. Factor 2, individualistic values, included the material success, competition and personal achievement items and explained 49% of the variance. Two items, one each from the collectivistism and individualism factors, were removed as their factor loadings were below .40 along with an item that cross-loaded on both factors (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 1998) (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Factor Loadings of Items from the Exploratory Factor Analyses of Total Sample and by Race-Ethnicity

| MACVS ITEMS | TOTAL SAMPLE | AFRICAN AMERICAN | EUROPEAN AMERICAN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collectivistic | Individualistic | Collectivistic | Individualistic | Collectivistic | Individualistic | |

| 1. No matter what, children should always treat adults with respect (R) | .63 | .00 | .58 | .10 | .67 | −.04 |

| 2. Children should respect adults like they are parents (R) | .54 | .02 | .63 | −.04 | .50 | .00 |

| 3. It is important for children to understand that adults should have final say when decisions are made (R) | .54 | .00 | .57 | .01 | .53 | .01 |

| 4. Children should be on their best behavior when visiting homes of friends or relatives (R) | .83 | −.01 | .81 | .10 | .84 | −.08 |

| 5. Children should always honor adults and never say bad things about them (R) | .69 | .04 | .62 | .14 | .74 | −.04 |

| 6. Children should follow rules, even if they think the rules are unfair (R) | .71 | .10 | .67 | .14 | .77 | .09 |

| 7. Children should always be polite when speaking to an adult (R) | .75 | .00 | .68 | .06 | .82 | −.01 |

| 8. Children should be taught that it is their duty to care for their parents when their parents get old (F) | .60 | .20 | .68 | .23 | .54 | .15 |

| 9. If a relative is having a hard time financially, one should help them out if possible (F) | .81 | .04 | .87 | .11 | .77 | −.07 |

| 10. A person should follow rules, even if they think the rules are unfair (F) | .71 | .07 | .73 | .18 | .69 | −.01 |

| 11. Older kids should take care of and be role models for their younger brothers and sisters (F) | .59 | .05 | .57 | .15 | .58 | .01 |

| 12. Parents should be willing to make great sacrifices to make sure their children have a better life (F) | .68 | .16 | .68 | .28 | .66 | .06 |

| 13. The more money one has, the more respect they should get from others (M) | .09 | .60 | .24 | .50 | −.01 | .62 |

| 14. Parents should encourage children to do everything better than others (C) | .14 | .53 | .18 | .39 | .13 | .59 |

| 15. The best way for a person to feel good about himself/herself is to have a lot of money (M) | −.07 | .83 | −.01 | .81 | −.14 | .84 |

| 16. Owning a lot of nice things makes one very happy (M) | .13 | .51 | .23 | .51 | .06 | .46 |

| 17. Children should be taught that it is important to have a lot of money (M) | .05 | .83 | .09 | .85 | .00 | .84 |

| 18. Money is the key to happiness (M) | −.07 | .79 | −.04 | .69 | −.08 | .85 |

| 19 Parents should teach their children to compete to win (C) | .03 | .68 | .06 | .65 | .00 | .67 |

Note. R = Respect items; F = Family Obligations items; M = Material Success items; C = Competition and Personal Achievement items.

Next, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) (MPlus v. 7) was conducted to evaluate the 2-factor (collectivistic and individualistic values) model fit. Following conventions of Hu and Bentler (1999), which suggestan acceptable fit is indicated by a non-significant chi-square; a comparative fit index (CFI) of .90 or above; a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of .06 or less; and SRMR of .08 or less, this model had an acceptable fit (χ2 (152) = 243.28, p < .001; RMSEA = .05, CFI =.93; SRMR = .07). Examination of the standardized estimates showed that two items in the collectivistic values factor (i.e., “Children should respect adults like they are parents”; “It is important for children to understand that adults should have final say when decisions are made”) and two items in the individualistic values factor (i.e., “Parents should encourage children to do everything better than others”; “Owning a lot of nice things makes one very happy”) had very low factor loadings (Range = .49 - .53) compared to the other items, suggesting that these items were not contributing to their respective factors (Furr, 2011). Therefore, these items were removed, and a CFA was performed again. This model had a good fit (χ2 (90) = 135.02, p < .01; RMSEA = .05, CFI =.96; SRMR = .06).

Next, multi-group CFAs were performed for the 2-factor model to examine measurement invariance across the African-American and European-American sample. Using the guidelines provided by Muthén and Muthén (2010), the models were first freely estimated such that factor loadings were allowed to vary across the African-American and European-American sample. Next, constrained models were examined in which factor loadings were not allowed to vary across the two racial-ethnic groups. Among African-Americans, the loadings were somewhat higher for 2 items in the familism scale representing family obligations (i.e., “Children should be taught that it is their duty to care for their parents when their parents get old” and “If a relative is having a hard time financially, one should help them out if possible”); the difference between the loadings was .10 - .14. However, the Satorra-Bentler chi-square difference test (https://www.statmodel.com/chidiff.shtml) was not statistically significant (χ2diff = 7.87, dfdiff = 13, ns) suggesting that the 2-factor model of cultural values was invariant, thus measured similarly overall, across the African-American and European-American samples. Table 2 provides descriptive data on all of the key measures in the study including means, standard deviations, internal consistency reliability and preliminary correlational data.

Table 2.

Inter-correlation among Key Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M (SD) | α | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Individualistic Values | - | 2.35 (1.15) | .85 | |||||

| 2. | Collectivistic Values | .06 | - | 3.72 (.80) | .91 | ||||

| 3. | SDQ - Conduct problems | .35** | −.13 | - | 1.42 (.41) | .58 | |||

| 4. | SDQ -Emotional Symptoms | .17* | −.12 | .44** | - | 1.57 (.50) | .78 | ||

| 5. | Russo et al. -Problem Behavior | .27** | −.24** | .39** | .06 | - | .83 (1.22) | - | |

| 6. | SDQ - Prosocial Behavior | −.31** | .10 | −.43** | −.08 | −.47** | - | 2.52 (.48) | .80 |

Note. Problem behavior was a count variable; therefore, its reliability is not provided.

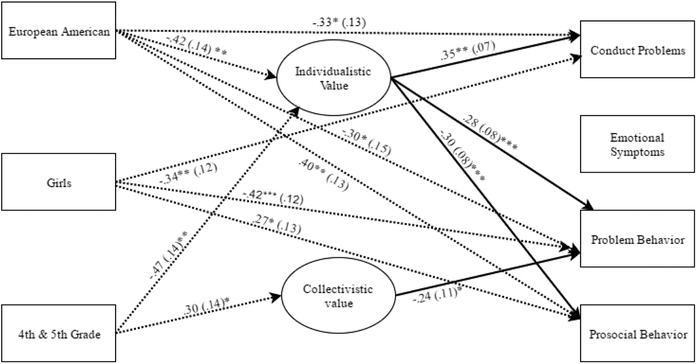

Structure Equation Modeling (SEM) analyses were performed in Mplus v.7 to examine whether cultural values varied by race-ethnicity, gender, and grade (research question 2) and the association of cultural values with behavioral outcomes (research question 3). Individualistic and collectivistic values were included as latent variables. Findings related to research questions 2 and 3 are presented incrementally, although the comprehensive model was tested simultaneously (See Figure 1). Overall, the model had a moderately acceptable fit (χ2 (187) = 286.33, p < .001; RMSEA =.05, CFI = .94; SRMR = .06).

Figure 1.

Association of cultural values with children’s behavioral outcomes.

Note. Coding was as follows: (0 = boy, 1 = girl), grade (0 = 1st – 3rd, 1 = 4th – 5th), and race-ethnicity (0 = African American, 1 = European American).

Solid lines represent associations of cultural values with behavioral outcomes; dotted lines represent associations of individual characteristics with cultural values and behavioral outcomes. For ease of representation, marginal and non-significant findings are not shown in this figure. ***p < .001. **p < .05. *p < .05.

Results showed that European-American children endorsed less individualistic values than African-American children (β = −.42, p < .01; 95% CI = [−.65, −.19]); however, African-American and European-American children did not significantly differ in their reports of collectivistic values as measured in this study. Boys and girls endorsed similar level of collectivistic and individualistic values. Also, children in 4th and 5th grades reported significantly less individualistic values (β = −.47, p < .01; 95% CI = [−.70, −.24]) and more collectivistic values (β = .30, p = .04; 95% CI = [.06, .53]) compared to children in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grades.

In terms of the relationships between values and behavior, children who endorsed more collectivistic values reported significantly less problem behaviors (β = −.24, p = .03, 95% CI = [−.42, −.06]). Children who endorsed more individualistic values reported significantly less prosocial behaviors (b = −.30, p < .001, 95% CI = [−.44, −. 16]) but more conduct problems and delinquent problem behaviors (bconduct problems = .35, p < .001, 95% CI = [.24, .46]; bproblem behavior = .28, p < .001, 95% CI = [.15, .41]).

Additional analyses were performed to examine if the association of cultural values with behavioral outcomes differed between European-American and African American children. First, a model was tested that allowed the paths to vary between groups. Second, a fully constrained model was examined such that all estimates were constrained to be equal across the two groups. The Satorra-Bentler chi-square difference test was not statistically significant (χ2diff = 26.08, dfdiff = 29, p = 0.62), suggesting that the model fit equally well for both groups of students. Therefore, the pattern of associations between cultural values and behavior were similar (i.e., not significantly different from one another) among African-American and European-American children.

Discussion

The present study was conducted to examine the cultural values of individualism and collectivism for African-American and European-American school-age children; whether these cultural values (collectivism and individualism) varied with children’s race-ethnicity, gender, and grade level; and to explore the degree to which collectivistic and individualistic cultural values were associated with children’s behavioral outcomes taking into account their race-ethnicity, gender, and grade level. Findings demonstrated that we could measure cultural values with reliability and validity across African-American and European-American racial-ethnic groups; however, at the item level, there were some small variations with higher loadings of a few items describing family respect and obligations for African-American children. Nevertheless, these variations were not large enough to result in significantly different conceptualizations of cultural values based upon our exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Further, once configured conceptually, all children in the sample were found to endorse collectivism similarly (with some items regarding family obligations that had higher loading for African-American children deleted) and African-American children actually reported higher levels of individualism. Thus, using these measures of cultural values and youth socio-behavioral outcomes, our findings did not provide support a dichotomous notion of classifying racial-ethnic groups as solely individualistic or collectivistic. Instead, our findings supported the notion that both value orientations can co-exist (Triandis et al., 1990; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2007). Collectivistic and individualistic values were found in both groups and, collectivistic values were associated with more adaptive behavior regardless of race-ethnicity.

Supporting Boykin’s (1986) triple quandry theory, African-American children possessed both individualistic and collectivistic values; they actually indicated higher levels of individualistic values that were less adapatative behaviorally. This finding may be due to the value of competition and material success being stressed in some contexts. For example, previous research has found schools to encourage individual values of competition (Tyler et al., 2006). Previous research has found a more materialistic emphasis among those who are less-advantaged economically, and this may well be the case in this study (Kasser & Ahuvia, 2002; Kasser et al., 2004). However, given the relationship in our study of individualistic values to problem behaviors for African-American and European-American children, families and other contexts might do well to encourage more collectivistic approaches that help youth to be attuned to the impact of their actions personally and for the group. For the European-American children, this is another example of how they, presumably in an overarching individualistic society, exhibited more collectivistic values at an individual level, albeit items measuring family obligations had lower loadings for this group. It also points to the potential diversity within the group of children labeled as European-American, in this northeastern state where many know the ethnicity of their forebears, they may emanate from groups across Europe that vary in the degree to which family obligations and respect are of import. It is also possible that youth in multi-cultural contexts influence each other in terms of their cultural values.

All the children in the sample with more collectivistic values reported engaging in significantly less delinquent problem behaviors. Conversely, children high in an individualistic orientation reported less prosocial behavior, increased conduct problems, and experimentation with drugs and alcohol, vandalism, and theft. Children with an individualistic cultural orientation may be over-focused on themselves and material gain whereas collectivistic children may possess more empathy and awareness of how their actions affect others.

The role of age and gender were also examined in this study. Grade differences were observed, with 4th and 5th graders reporting more collectivistic but less individualistic values than children in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grade. According to Eriksonian theory (1994) and cultural perspective-taking theory (Quintana, 1994), older children, regardless of their race-ethnicity, may be more collectivistic. As young people grow, they are expected to have less egocentric notions of self and an awareness of others that may be related to collectivism and prosocial behaviors. Based on Gilligan’s (1982) work on gender socialization and the “care perspective,” we posited that girls would demonstrate higher levels of collectivistic orientation due to how girls are socialized to consider the consequences of their actions on others and are expected to exhibit less conduct problems or delinquent behaviors. Surprinsingly however, irrespective of age, girls and boys demonstrated similar levels of collectivistic and individualistic values.

In sum, we contend that these data support the belief that collectivism and individualism should be considered with complexity, across culture, gender, and the multiple socio-cultural contexts that influence children’s actions, and interactions. While we find collectivistic values to be related to more prosocial behavior, previous research with adolescents has found a more individualistic orientation might foster academic achievement and motivation; an important topic for future exploration given mixed prior research findings in this regard (Tseng, 2004; Tyler et al., 2006). Based on stage-environment fit models (Eccles, Midgley, Wigfield, Buchanan, Reuman, Flanagan, & MacIver, 1993; Gutman & Eccles, 2007), we contend that children balance these cultural value orientations according to specific contexts (i.e., school, home, community, faith community, extracurricular activities). However, in this study, we find collectivtistic values to be more helpful in terms of behavioral outcomes for this sample but future research could also explore relationships with academic and mental health outcomes across multiple contexts.

Strengths and Limitations

These findings indicate that cultural values are significantly related to elementary-age children’s behavior. Much of the scholarship examining cultural values with immigrant adolescents and young adults in the U.S. using African-American and European Americans for comparison. We further extend the predominant scholarship to better understand our sample of African-American and European-American elementary-school-aged children in urban, suburban, and rural regions of a northeastern state, supporting the external validity of our findings across a fairly broad group of children. Future work might attend to the potential role of neighborhood structure and interactions in diverse children’s endorsement of cultural values, given that neighborhoods are also cultural socialization agents (Witherspoon, Daniels, Mason, & Smith, 2016).

As with any study, there are limitations, one being the cross-sectional design. Also, our study predominantly uses child self-reported measures, though previous research has demonstrated child self-reports to correspond with other parent and teacher sources (Mellor, 2004). It would be important for future work to examine development and change in cultural values as children age with multiple reports and how this may be related to prosocial and risky behaviors. In terms of exploring developmental effects in future research, it is possible that certain cultural values may be especially important for younger children, but autonomy and individualistic values may play a stronger role in influencing behaviors in later adolescence and adulthood.

We acknowledge that our study focused on African-American and European-American children and that the sample of Latino, Asian, Native American and other-identified children in our original dataset was small. Notwithstanding, there are fewer studies examining the cultural values of African-American and European-Americanchildren; all of whom are young people living in increasingly diverse environments. We hope this study will serve as a springboard for other studies examining the role of cultural values for children of diverse ethnic and racial groups across development with implications for future research that examines the role of family and community contexts in cultural socialization and youth.

Table 3.

Results of t-test and Descriptive Statistics for Key Study Variables by Race, Gender, and Grade

| Race | Gender | Grade | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African-American | European American | Boy | Girl | 1st,2nd,3rd grade | 4th, 5th grade | |||||||

| M | M | t | df | M | M | t | df | M | M | t | df | |

| (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | |||||||

| Individualistic | 2.65 | 2.14 | 3.35** | 216 | 2.46 | 2.26 | 1.29 | 216 | 2.54 | 2.02 | 3.25** | 216 |

| Value | (1.19) | (1.07) | (1.17) | (1.12) | (1.15) | (1.08) | ||||||

| Collectivistic | 3.69 | 3.74 | −.38 | 217 | 3.66 | 3.76 | −.93 | 171.63 | 3.63 | 3.86 | −2.04* | 217 |

| Value | (.87) | (.75) | (.94) | (.66) | (.81) | (.76) | ||||||

| SDQ-Conduct | 1.54 | 1.33 | 3.54** | 159.87 | 1.52 | 1.34 | 3.24** | 207 | 1.42 | 1.42 | −.15 | 207 |

| Problems | (.45) | (.36) | (.44) | (.37) | (.40) | (.43) | ||||||

| SDQ-Emotional | 1.66 | 1.51 | 2.01* | 170.19 | 1.56 | 1.58 | −.21 | 213 | 1.60 | 1.52 | 1.22 | 192.07 |

| Symptoms | (.55) | (.45) | (.49) | (.50) | (.53) | (.43) | ||||||

| Russo et al- | 1.15 | .61 | 2.96** | 173 | 1.17 | .57 | 3.08** | 108.69 | .84 | .82 | .14 | 173 |

| Problem Behavior | (.122) | (1.18) | (1.54) | (.81) | (1.11) | (1.39) | ||||||

| SDQ- Prosocial | 2.37 | 2.64 | - | 147.38 | 2.43 | 2.60 | −2.52* | 176.78 | 2.52 | 2.53 | −.15 | 212 |

| Behavior | (.55) | (.37) | 3.98*** | (.53) | (.41) | (.50) | (.45) | |||||

Note. Coding was as follows: (0 = boy, 1 = girl), grade (0 = 1st – 3rd, 1 = 4th – 5th), and race-ethnicity (0 = African American, 1 = European American).

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05

Acknowledgments

Funding support was provided from the William T. Grant Foundation, Grant #8529; the Wallace Foundation, Grant #20080489; and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute for Drug Abuse, Grant # R01 DA025187 to Emilie Smith (PI), and an NIH Diversity Supplement to Dawn Witherspoon.

We acknowledge the many staff, parents, and children whose participation made this study possible. Andrea Farnham contributed to earlier versions of this paper.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving Human Participants was approved and monitored by The Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board (IRB # 23990) and have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

Emilie Phillips Smith, University of Georgia.

Dawn P. Witherspoon, The Pennsylvania State University

Sakshi Bhargava, The Pennsylvania State University.

J. Maria Bermudez, University of Georgia.

References

- Aboud FE (1988). Children and prejudice. Oxford, England: B. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Alltucker KW, Bullis M, Close D, & Yovanoff P (2006). Different pathways to juvenile delinquency: Characteristics of early and late starters in a sample of previously incarcerated youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15(4), 475–488. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9032-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, & Vedder P (2006). Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 55(3), 303–332. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley A, (1994). Climbing Jacob’s ladder: The enduring legacies of African-American families. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Boykin AW (1986). The triple quandary and the schooling of Afro-American children In Neisser U (Ed.), The school achievement of minority children (pp. 57–92). Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB, & Chen YR (2007). Where (who) are collectives in collectivism? Toward conceptual clarification of individualism and collectivism. Psychological Review, 114(1), 133–151.doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.1.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ and the SRCD Ethnic and Racial Issues Committee (2013). Positive Development of Minority Children. Social Policy Report, 27(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Tamis-LeMonda CS, & Yoshikawa H (2013). Familismo in Mexican and Dominican families from low-income, urban communities. Journal of Family Issues,34(12), 1696–1724. [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MOB, Nettles SM, O’Campo PJ, & Lohrfink KF (2006). Neighborhood matters: Racial socialization of African-American children. Child Development, 77(5), 1220–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, & Cohen J (1996). Research monographs in adolescence Life values and adolescent mental health. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Coon HM, & Kemmelmeier M (2001). Cultural Orientations in the United States: (Re)Examining Differences among Ethnic Groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(3), 348–364. [Google Scholar]

- Constantine M, Alleyne V, Wallace B, & Franklin-Jackson D (2006). Afrocentric cultural values: Their relation to positive mental health in African-American adolescent girls. Journal of Black Psychology, 32, 141–154. doi: 10.1177/0095798406286801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Diener M, & Diener C (1995). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, & Diener M (2009). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem In Diener E (Ed.), Culture and Well-Being: The collected works of Ed Diener (pp. 71–91). Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Wigfield A, Buchanan C, Reuman, Flanagan C, MacIver D. (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families, American Psychologist, 48(2), 90–101. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1994). Identity: Youth and crisis (No. 7). New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Eckersley R, & Dear K (2002). Cultural correlates of children suicide. Social Science & Medicine, 55(11), 1891–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ (2001), Family obligation and the academic motivation of adolescents from Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 61–76. doi: 10.1002/cd.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Yip T, & Tseng V (2002). The impact of family obligation on the daily activities and psychological well-being of Chinese American adolescents. Child Development, 73(1), 302–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V and Lam M (1999). Attitudes toward Family Obligations among American Adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European Backgrounds. Child Development, 70: 1030–1044. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, & García HV (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese ED (1976). Roll, Jordan, roll: The world the slaves made (Vol. 652). New York, NY: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan Carol (1982). In a Different Voice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Meltzer H, & Bailey V (2003). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. International Review of Psychiatry, 15(1–2), 173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra N, & Smith EP (2006). Preventing youth violence in a multicultural society. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman HG (1976). Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750–1925 Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, & Eccles JS (2007). Stage-environment fit during adolescence: Trajectories of family relations and adolescent outcomes, Developmental Psychology, 43 (2), 522–537. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, & Tatham RL (1998). Multivariate data analysis (Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 207–219). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LC, Ispa JM, & Rudy D (2006). Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development, 77, 1268–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardaway C, & Fuligni AJ (2006). Dimensions of family connectedness among adolescents with Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 42(6), 1246–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskovits MJ (1990). The Myth of the Negro Past. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill RB (1999). The Strengths of African-American Families: Twenty-Five Years Later. Landham, MD: University Press of America, [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE (2006). Disentangling ethnicity, socioeconomic status and parenting: Interactions, influences and meaning. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 1(1), 114–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ispa JM, Fine MA, Halgunseth LC, Harper S, Robinson J, Boyce L, Brooks-Gunn J & Brady-Smith C (2004). Maternal intrusiveness, maternal warmth, and mother-toddler relationship outcomes: variations across low-income ethnic and acculturation groups, Child Development, 75(6), 1613–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagers RJ (1998). Afrocultural integrity and the social development of African-American children: Some conceptual, empirical, and practical considerations. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 16(1–2), 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kâğitçibaşi C (1997). Individualism and collectivism In W Berry J, Segall MH, Kâğitçibaş Ç (Eds.), Handbook of Cross-cultural Psychology: Volume 3, Social Behavior and Applications (2nd Ed.), (pp. 1–49)., Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Kam J, & Yang S (2014). Explicating how parent-child communication increases Latino and European American early adolescents’ intentions to intervene in a friend’s substance use. Prevention Science, 15(4), 536–546. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0404-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T, & Ahuvia A (2002). Materialistic values and well- being in business students. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32(1), 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T, Ryan RM, Couchman CE, & Sheldon KM (2004). Materialistic values: Their causes and consequences In Kasser T & Kanner AD (Eds.), Psychology and consumer culture: The struggle for a good life in a materialistic world (pp. 11–28). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Kim UE, Triandis HC, Kâğitçibaşi ÇE, Choi SCE, & Yoon GE (1994). Individualism and Collectivism: Theory, method, and applications. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, … & Updegraff KA (2009). The Mexican American cultural values scale for adolescents and adults. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 30(3), 444–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Mazza GL, & Carlo G (2018). Trajectories of familism values and the prosocial tendencies of Mexican American adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 54(2), 378–384. doi: 10.1037/dev0000436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam AG, & Zane NW (2004). Ethnic differences in coping with interpersonal stressors a test of self-construals as cultural mediators. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(4), 446–459. [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, & Klonoff EA (1996). African-American Acculturation: Deconstructing race and reviving culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis KM, Sullivan CM, & Bybee D (2006). An experimental evaluation of a school-based emancipatory intervention to promote African-American well-being and youth leadership. Journal of Black Psychology, 32(1), 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Martin BL (1991). From Negro to Black to African-American: The power of names and naming. Political Science Quarterly, 106(1), 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC (1990). Minority children: Introduction to the special issue. Child Development, 61(2), 263–266.2344776 [Google Scholar]

- Mellor D (2004). Furthering the use of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire: Reliability with younger child respondents. Psychological Assessment, 16(4), 396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton B, Woods SE, Dugdill L, Porcellato L, & Springett RJ (2008). Starting young? Children’s experiences of trying smoking during pre-adolescence. Health Education Research, 23(2), 298–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (2010). Mplus User’s Guide (6 Ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén [Google Scholar]

- Myrdal G (1944). An American dilemma, Volume 2: The Negro problem and modern democracy (Vol. 2). Location: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Nobles WW (1991). African philosophy: Foundations for black psychology In Jones RL (Ed.), Black psychology (3rded.) (pp. 47–63). Berkeley, CA, US: Cobb & Henry Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU (1981). Origins of human competence: A cultural-ecological perspective. Child Development, 413–429. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Forgatch MS, Yoerger KL, & Stoolmiller M (1998). Variables that initiate and maintain an early-onset trajectory for juvenile offending. Development and Psychopathology, 10(3), 531–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry P (2001). White Means Never Having to Say You’re Ethnic: White children and the construction of “cultureless” identities. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 30(1), 56–91. [Google Scholar]

- Phan T and Glander M (2008). Documentation to the NCES Common Core of Data Public Elementary/Secondary School Locale Code File: School Year 2005–06 (NCES 2008–332). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; Washington, DC: Retrieved December 5, 2012 from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2008332. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Ong A, & Madden T (2000). Cultural values and intergenerational value discrepancies in immigrant and non-immigrant families. Child Development, 71(2), 528–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim C, & Rueda-Riedle A (2002). The importance of social context in cross-cultural comparisons: First graders in Colombia and the United States. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 163(3), 283–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM (1994). A model of ethnic perspective-taking ability applied to Mexican-American children and children. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 18(4), 419–448. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, & Vera EM (1999). Mexican American children’s ethnic identity, understanding of ethnic prejudice, and parental ethnic socialization. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 21(4), 387–404. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG, & Portes A (2001). Ethnicities: Children of immigrants in America. Berkley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Russo MF, Stokes GS, Lahey BB, Christ MAG, McBurnett K, Loeber R, … & Green SM (1993). A sensation seeking scale for children: Further refinement and psychometric development. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 15(2), 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sabogal R, VanOss Marin B, Perez-Stable EJ. (1987). Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9(4), 397–412. doi: 10.1177/07399863870094003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schor JB (2004). Born to buy: The commercialized child and the new consumer culture. New York, NY: Scribner. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SH (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied Psychology, 48(1), 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Des Rosiers SE, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Zamboanga BL, Huang S, … & Szapocznik J (2014). Domains of acculturation and their effects on substance use and sexual behavior in recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Prevention Science, 15(3), 385–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, & Szapocznik J (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65(4), 237–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Waterman AS, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Lee RM, Kim SY, Vazsonyi AT,& … Williams MK (2013). Acculturation and well-being among college students from immigrant families. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(4), 298–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CO, Levine D, Smith EP, Prinz RJ, Dumas E (2009). The Emergence of Racial-Ethnic Identity in Children and its Role in Adjustment: A Developmental Perspective. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(2), 145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague J, & Walker H (2000). Early identification and intervention for youth with antisocial and violent behavior. Exceptional Children, 66(3), 367–379. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Dupree D, & Hartmann T (1997). A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST): A self-organization perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology, 9(4), 817–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidel AGL, & Contreras JM (2003). A new Familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25(3), 312–330. doi: 10.1177/0739986303256912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarkasa N (1998). Interpreting the African heritage in Afro-American family organization In McAdoo HP (Ed.), Black families (2nd ed.) (pp. 27–43); Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS (2007). Experimental Designs Using ANOVA. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis- LeMonda CS, Way N, Hughes D, Yoshikawa H, Kalman RK, & Niwa EY(2007). Parents’ goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Social Development, 17(1), 183–209. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DE, Townsend TG, & Belgrave FZ (2003). The influence of cultural and racial identification on the psychosocial adjustment of inner- city African-American children in school. American Journal of Community Psychology, 32(3–4), 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC (1990). Theoretical concepts that are applicable to the analysis of ethnocentrism. Applied Cross-cultural Psychology, 14, 34–55. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, & Gelfand MJ (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, McCusker C, & Hui CH (1990). Multimethod probes of individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 1006–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng V (2004). Family interdependence and academic adjustment in college: Youth from immigrant and US-born families”. Child Development 75(3), 966–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KM, Boykin AW, Miller O, & Hurley E (2006). Cultural values in the home and school experiences of low-income African-American students. Social Psychology of Education, 9(4), 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Thayer SM, & Delgado MY (2005). Adolescent sibling relationships in Mexican American families: exploring the role of familism. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(4), 512–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau (2017). U.S. Census, QuickFacts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045217

- Vargas JH, & Kemmelmeier M (2013). Ethnicity and contemporary American culture: Ameta-analytic investigation of horizontal–vertical individualism–collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(2), 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven R (1999). Quality-of-life in individualistic society. Social Indicators Research, 48(2), 159–188. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez-Agosto NM, Soto-Crespo JG, Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer M, Vega-Molina S, & García Coll C (2017). Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory revision: Moving culture from the macro into the micro. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 900–910. http://iournals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1745691617704397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, & Tamis-Lemonda CS (2003). Do child-rearing values in Taiwan and the United States reflect cultural values of collectivism and individualism?. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34(6), 629–642. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman AS (1981). Individualism and interdependence. American Psychologist, 36(7), 762–773. [Google Scholar]

- Williams RM (1970). American society: A sociological interpretation (3rd. ed.). New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Witherspoon DP, Daniels LL, Mason AE, & Smith EP (2016). Racial-ethnic identity in context: Examining mediation of neighborhood factors on children’s academic adjustment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57(1–2), 87–101. 10.1002/aicp.12019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada AM, & Singelis TM (1999). Biculturalism and self-construal. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23(5), 697–709. [Google Scholar]

- Yau JP, Tasopoulos-Chan M, & Smetana JG (2009). Disclosure to parents about everyday activities among American adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Child Development, 80(5), 1481–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]