Abstract

Rationale:

Since 1996, members of the Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation and faculty and students at Montana State University have worked in a successful community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnership, leading to increased trust and improvements in health awareness, knowledge, and behaviors. As major barriers to health and healthy behaviors have caused inequities in morbidity and mortality rates for multiple chronic diseases among the Apsáalooke people, community members chose to focus the next phase of research on improving chronic illness management.

Objective:

Existing chronic illness self-management programs include aspects inconsonant with Apsáalooke culture and neglect local factors seen as vital to community members managing their health conditions. The aim of this study was to use CBPR methods grounded in Apsáalooke cultural values to develop an intervention for improving chronic illness self-management.

Method:

Community members shared stories about what it is like to manage their chronic illness, including facilitators and barriers to chronic illness management. A culturally consonant data analysis method was used to develop a locally-based conceptual framework for understanding chronic illness management and an intervention grounded in the local culture.

Results:

Components of the intervention approach and intervention content are detailed and similarities and differences from other chronic illness management programs are described.

Conclusions:

Our collaborative process and product may be helpful for other communities interested in using story data to develop research projects, deepen their understanding of health, and increase health equity.

Keywords: United States, Indigenous, Chronic illness, Community health, Community-based participatory research, Indigenous research methods, Trauma informed intervention

1. Introduction

Chronic illnesses are the leading causes of death and disability worldwide (Benzinger et al., 2016), accounting for over 70% of all deaths in the US in 2016 (Heron, 2018). In 2010, the prevalence of multiple chronic illnesses (> 2) across ethnicities for those aged 44 to 64 was 28.1%, whereas for non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Natives, the prevalence was 66.8% (Ward and Schiller, 2013). Significant disparities in morbidity and mortality exist between whites and American Indians with chronic illness (Hatala et al., 2019; IHS, 2015). Montana American Indians die 18 years earlier than whites overall with disparities in potential years of life lost from chronic illnesses, including atherosclerosis (21.5 years), kidney disease (20 years), cerebrovascular disease (12 years), and diabetes (11 years) (Vital Statistics Unit, 2018).

In Montana, the chronic illness disparities American Indians face are rooted in a complex interplay of factors, including colonization practices that forced a rapid shift in diet and activity patterns (Joe and Young, 1994), ongoing economic, geographic, and political impacts of the reservation system (Brown et al., 2007), generations of poor health care access (Zuckerman et al., 2004), and the physical and mental effects of historical and current cultural loss (Real Bird et al., 2016). The Apsáalooke (Crow) community, spread across more than two million acres, is served by an Indian Health Service hospital and two rural outpatient clinics on the reservation, a community health center and critical access hospital located just outside the reservation. A significant portion of the community also receives health care from traditional healers and spiritual leaders within the community. Ongoing challenges in health care access include long distances and lack of reliable transportation even to local health facilities (Hensely-Quinn and Shawn, 2006), provider shortages and inadequate access to specialty care (Baldwin et al., 2008; Warne and Frizzell, 2014), fragmentation between health systems, lack of trust in providers and systems, and provider racial bias (Bastos, Harnois, and Paradies, 2018; Maina et al., 2018; Simonds et al., 2011). Indeed, as other studies with different populations have found, the persistent and daily strain and stress related to structural inequalities and access to health care services can have profound impacts on mental and physical health outcomes (Cheney et al., 2018).

While access to high quality, stable, and holistic primary care systems are essential to managing chronic illnesses, people living with chronic illnesses spend significantly more time managing their care at home and in the community compared to time spent in clinical settings (IOM, 2012;Thorne, 2008). Chronic illness self-management requires daily adherence to a medication and lifestyle change regimen, yet nonadherence rates are estimated to be 50–80%, across populations (Osterberg and Blaschke, 2005; WHO, 2003). The ability to effectively manage health conditions is key to improving health outcomes (Bodenheimer et al., 2002; Nuovo, 2007). Therefore, interventions focusing on daily self-management are essential to improve health outcomes and address health disparities.

The evidence-based, Stanford University-developed, Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) is considered the gold standard for chronic illness self-management programs for the general adult population (Bodenheimer et al., 2002; Lorig et al., 1999, 2001, 2013; Ory et al., 2013;Woodcock et al., 2013). The CDSMP was not developed using knowledge of what helps and what hinders chronic illness self-management from the perspective of individuals from Indigenous cultures. This deficit is crucial considering the significant differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous views of health and disease (Bartlett et al., 2007; Donatuto et al., 2011; Duran, 2011) and the ramifications of colonization and the reservation system on health outcomes. These factors are important to consider as programs such as the CDSMP have been shown to be difficult to sustain in American Indian communities (Jernigan, 2010; Narayan et al., 1998; Stillwater, 2007, 2012).

Implementing and testing evidence-based interventions in new settings is considered a best practice (Rotheram-Borus et al., 2012). But, when an intervention developed for the majority culture is implemented in an Indigenous community without local input, it becomes another example of a colonizing behavior, and may evoke feelings similar to past forced assimilation practices, such as boarding schools, removal from tribal lands, and banning of traditional hunting and languages (Bartlett et al., 2007; E. Duran and Firehammer, 2014). The “implementation without consultation” practice is often viewed as contributing to the health disparities that these very interventions are intended to address (Real Bird et al., 2016). Health initiatives using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach can provide effective solutions as an alternative to imposing externally developed interventions onto communities (Wallerstein and Duran, 2010).

Established in 1996, our CBPR partnership is comprised of an Apsáalooke Nation non-profit organization called Messengers for Health and Indigenous and non-Indigenous faculty and students from Montana State University. The Messengers for Health Board of Directors serves as a Community Advisory Board (CAB) for research projects, which enrolled members of the Apsáalooke Nation, including elders, those with chronic illness, and those working in education and health, comprise. With their collective knowledge base, expertise, and wisdom, the CAB provides direction for the partnership and assures that CBPR projects respect the cultural protocols of the Apsáalooke Nation.

Our CBPR approach is grounded in a decolonizing research process, which places Indigenous voices and epistemologies at the center of the research (Bartlett et al., 2007; Battiste, 2000; Kovach, 2010b; Rigney, 1999; Smith, 1999; Wilson, 2008; Zavala, 2013). Research using methods that emerge from frameworks consonant with local cultures results in greater community acceptance and ownership, which produce more effective and sustainable interventions (Cochran and Geller, 2002; Cochran et al., 2008; Mohatt et al., 2004; Wilson, 2008).

In 2013, our CAB decided to focus our next project on working with community members who have chronic illnesses. The core motivation for this research arose from concern over the disparate impact of chronic illnesses on the community and from the lack of chronic illness interventions responsive to Indigenous contexts. The aim of this study was to use CBPR methods grounded in Apsáalooke cultural values to develop an intervention for improving chronic illness self-management. The research question informing this study was, “How can a CBPR method grounded in Indigenous cultural values and approaches guide the development of a chronic illness self-management program that responds to local needs and historical contexts?” This study describes how: 1) qualitative interview data informed both content and approach of a culturally consonant chronic illness self-management program for Apsáalooke tribal members, and 2) Apsáalooke cultural values provided for a strengths-based program.

2. Method

We engaged community members who offered stories of living with and managing chronic illness by utilizing a qualitative phenomenological approach. We received primary Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from Little Big Horn College, which is an Apsáalooke Tribal College, and secondary approval from the Montana State University IRB. From January to May 2014, in partnership with a local community health center, we interviewed 20 community members. We used purposive sampling, selecting interviewees based on their ability to provide information on managing chronic illness. Recruitment and interviewing proceeded efficiently because community members knew and trusted the organization that has been working in the community for several decades and that has previously used community interviews to build local programs. Participants (12 female and 8 male) ranged in age from 26 to 78 and had a variety of chronic illnesses including hypertension, chronic pain, chronic hepatitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, alcoholic cirrhosis, and rheumatoid arthritis; many participants had multiple chronic illnesses. Participants fulfilled a variety of roles in the community including elders, clan aunts and uncles, those employed by the tribe and by other community employers, retirees, home makers, parents, grandparents, and caregivers. Participants also participated in a variety of traditional spiritual and cultural practices.

Many Indigenous communities, including the Apsáalooke, use stories to communicate local ways of knowing as a primary method for illness explanation and to cultivate deeper levels of understanding that facilitate positive changes for community members (Garroutte and Westcott, 2008; Hodge et al., 2002; Tom-Orme, 2000; Wexler, et al., 2019). The third author, a tribal member, conducted interviews at a convenient time and location for community members. Participants were asked to “share about [their] health from the time [they] were young up until the present time.” Additional open-ended questions focused on participants’ perceptions of the impact of historical and current trauma/loss on health, experience managing their chronic illness, and thoughts on how to help community members with chronic illness. Interviews ranged from about 9 min to 1 h 40 min, with an average length of about 42 min.

In the past, when co-analyzing interview data, CAB members stated that breaking up interview data into themes (i.e., content or thematic analysis) was not compatible with their ways of knowing (Simonds and Christopher, 2013). This instance is a methodological issue discussed by multiple Indigenous researchers and researchers working with Indigenous communities (Kovach, 2010a; Lavalee, 2009; West et al., 2012; Wilson, 2008). After seeking input from a wide array of literature, community Elders, and colleagues, we developed a culturally consonant data analysis solutison. For an extensive explanation of the process, including inclusion criteria, sampling strategy, data gathering and analysis details, please see Hallett et al. (2017).

Data analysis consisted of 8–16 team members sitting together listening to community members’ stories and discussing “what touched [their] heart.” This prompt was asked by the third author, whose heart was touched listening to community members’ stories during the interview process. She felt that asking this question invited data analysts to the scene of the interview to feel the power and emotion of participants’ stories. In addition to sharing what touched their hearts while listening to the interviews, community analysts also added information from their and their family members’ experiences managing chronic illness.

Direct listening allowed team members to be engaged and focused, and it opened the door to a natural unfolding of the program’s content and approach. Instead of fracturing stories into themes, what developed was a holistic picture of the community’s daily victories and struggles with chronic illnesses. Halfway through discussing the interviews, at a time when similar information was repeated, we hung a piece of paper to capture key emerging ideas. On one half of the paper was written “things that help with coping [with chronic illness] ” and the other half “things that make it harder to cope.” This framework was a natural unfolding of events, rather than a preplanned activity. More discussions ensued and team members wrote phrases (e.g., access to medicine, self-advocacy, good communication with your provider, feel like you are a burden to family) and single words (e.g., grief, spirituality, denial, exercise) on sticky notes and put them on the corresponding half of the paper. Eventually, we noted that we were no longer adding new sticky notes to the paper, signaling we had reached theoretical saturation.

The combination of analysis structure and flexibility allowed for the translation of community stories into a conceptual framework of a holistic and local understanding of chronic illness self-management, which guided the development of an intervention that was tailored to the specific needs and experiences of chronic illness management in this community. Analyzing in this manner provided honor, respect, and wholeness to everyone’s story. The team spent more than 60 h conducting data analysis over three months.

3. Results

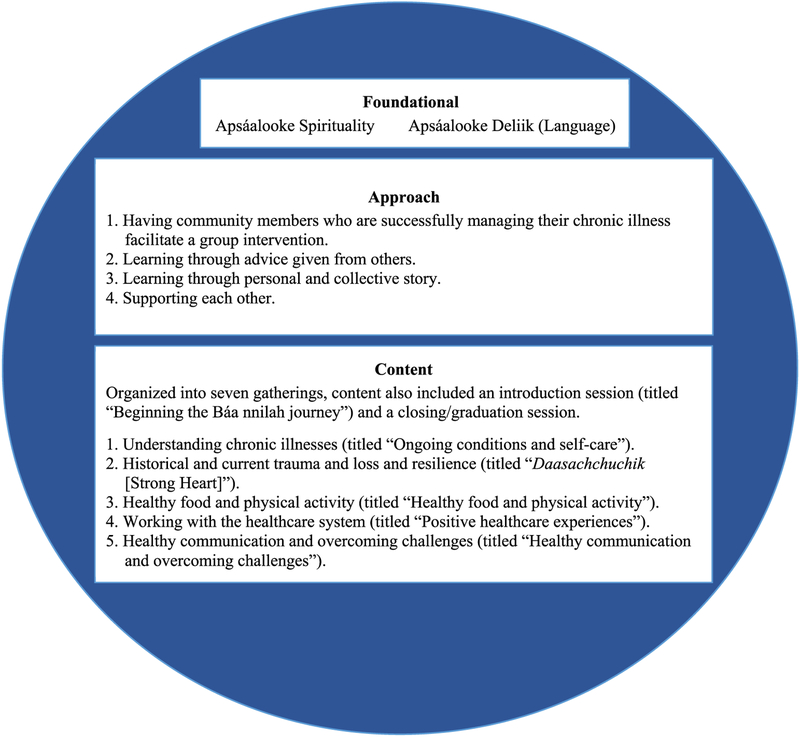

Fig. 1 shows the components of the intervention approach and intervention content that arose from our analysis discussions. Two components are foundational for both the intervention approach and content – spirituality and language. Interview participants expressed that spirituality was a primary factor that impacted their chronic illness, that it has helped them in their lives thus far, and that it will be used to seek guidance going into the future. Because spirituality is a powerful guide in community members’ daily lives in all that is done and in every step that is taken, it featured prominently in, and fundamentally guided the development of our program. Spirituality will be demonstrated in multiple ways throughout the program, for example, by opening and closing each program gathering with prayer and by including praying and maintaining a spiritual connection as a method for addressing chronic illness symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Aspects of the intervention approach and intervention content that arose from data analysis discussions.

Apsáalooke Deliik is the Apsáalooke language. The value and power of language cannot be overstated – language sustains the culture. An estimated 85% of adults 45 and older speak the language, and the vast majority of adults understand it when spoken to. The Apsáalooke language will be used in the intervention name and in appropriate ways during the intervention. As discussed below, the intervention will be facilitated by community members. When both facilitator and program participants speak the language, the intervention gatherings will be naturally facilitated in the language. Apsáalooke team members stated that information received in the Apsáalooke language is absorbed in a deeper and more impactful way.

3.1. Intervention approach

Insights from interview participants directly informed our intervention approach. Components of the intervention approach that resulted from the analysis included: 1. having community members who are successfully managing their chronic illness facilitate a group intervention, 2. learning through advice given from others, 3. learning through personal and collective story, and 4. supporting each other. For examples of direct quotations from interview transcripts illustrating each of these domains, please see Table 1.

Table 1.

Interview quotations that informed intervention approach.

| 1. Having community members with chronic illness facilitate a group intervention. | “If you guys found out what could help, I’d like to know. And maybe, possibly, even going and help[ing]. I don’t have the answer to that, but I’d like to say that if you guys find out, I’d like to be a person that helps.” [Interview 18] |

| 2. Learning through the advice given from others. | “I think, things like this, this interview, could help a lot of people from preventing things like diabetes and alcoholism and depression. And, to look after one another and help each other, and just even uh, get advice, too.” [Interview 1] |

| 3. Learning through personal and collective story. | “I love that so much, working with old people and hearing their stories …” [Interview 15] |

| “… our elders taught us the history of where we came from, and where, how this happened, how we ended up here. And I learned a lot from my grandparents and my uncles, and my aunts. I listened.” [Interview 5] | |

| 4. Supporting each other. | “I think I need more support for the emotional or spiritual side. I think I should go to meetings for – they talk about things like this, you know. So, that I can get a better idea of how to react to it and how to be able to cope with it. And how to understand it.” [Interview 19] |

-

Having community members with chronic illness facilitate a group intervention. Early in our analysis discussions, team members noted that many community members who were interviewed were role models for how to positively manage a chronic illness and that there were others in the community with chronic illnesses who were positive role models. This finding led to the approach of having role model community members with chronic illnesses become mentors for other community members who are working on improving chronic illness self-management.

The approach that arose from the analysis was to have mentors facilitate small group meetings (called gatherings) comprised of a facilitator and 10 community members. Gatherings are congruent with the close kinships and relationships present in Apsáalooke culture and reflect the cultural significance of visiting and of spending quality time with others. As one community member stated, “[Visiting] makes both people feel good.”

-

Learning through the advice given from others. A community member analyst shared that a vital aspect of role modeling is báa nnilah, which means “advice that is received from others.” This advice is often shared through story and gives instructions for life. If one listens and applies this advice, it will keep one on the right path and will help one avoid making mistakes. Culturally, it is an honor to receive and follow the advice because doing so respects both the storyteller and the tradition.

It was decided through consensus to name the developing intervention Báa nnilah and the mentors Aakbaabaaniilea, “the ones who give advice.” In addition, it was decided that each gathering would include a sharing circle, where participants could share advice and learn from each other through stories.

-

Learning through personal and collective story. In the sharing circle, Aakbaabaaniilea share a story from their life focused on the topic of the gathering (see topics below) and invite other participants to share their stories. Stories often describe what has been learned through one’s own experiences, actions that caused positive or negative outcomes, and lessons from which others can learn. Stories are also a way to ease into sensitive topics.

The power of learning through story will also be utilized in each gathering by including a traditional collective story that has a lesson related to the topic of the gathering. Many of these stories involve Old Man Coyote, a common figure in Apsáalooke stories. These stories were offered by CAB members and gathered from tribal college archives. In the gatherings, participants will take turns reading parts of the story out loud; during a follow-up sharing circle, they may relate their experiences to what they learned from the story or from other participants.

Supporting each other. Many interview participants shared feelings of isolation and loneliness that arose from living with chronic illnesses. To positively impact these feelings, we developed an approach called “supportive partnerships.” Participants will be partnered into supportive pairs and commit to providing support by staying in touch with each other at least once per week throughout the intervention. If they live together or are married, we will encourage the supportive pair to take time outside of their usual activities, where they will share and support each other. Partners will share contact information, ideas on how they would most like to be supported and make plans for how they will stay in touch in between the bimonthly gatherings. Participants will learn from and mentor each other within their supportive pair, while also learning and engaging with the larger group.

3.2. Intervention content

Concepts regarding intervention content also emerged from analysis discussions and resulted in an intervention that included 7-gatherings: 1. Understanding chronic illnesses (titled “Ongoing conditions and self-care”), 2. Historical and current trauma and loss and resilience (titled “Daasachchuchik [Strong Heart] ”), 3. Healthy food and physical activity (titled “Healthy food and physical activity”), 4. Working with the healthcare system (titled “Positive healthcare experiences”), and 5. Healthy communication and overcoming challenges (titled “Healthy communication and overcoming challenges”). There will also be an introduction gathering (titled “Beginning the Báa nnilah journey”) and a closing/graduation gathering. Intervention content was developed collaboratively by the project team and reviewed by the Aakbaabaaniilea and CAB for feedback and suggestions. Components of the content that emerged during analysis were directly informed by insights from interview participants. Please see Table 2 for direct quotations from interview transcripts illustrating each component.

Table 2.

Interview quotations that informed intervention content.

| 1. Understanding chronic illnesses (titled Ongoing conditions and self-care). | “I think if they’re more involved. You asked earlier about, you know, spiritually and emotionally and I think if people become more aware of you know, that these are things that they gotta’ contend with, perhaps through no faults of their own and sometimes through faults of their own, or sometimes through environment because of you know, things that they self-medicate with … [Y]ou know, it affects them. [Interview 3] |

| 2. Historical and current trauma and loss and resilience (titled Daasachchuchik [Strong Heart]). | “The prejudices – it still goes on. You know. It goes on. It’s still there. Like I said, you know, they tried to get rid of the Indians […]” [Interview 14] |

| “I think they took a lot away from Crow people. Actually, all Native Americans. They took a lot away, all within a short period of time. And it was, a whole culture shock, and I think that made a lot of people depressed, especially with rations, commodities came around then. And then we had to stop hunting, and those kind of things, those traditional foods were just take – were just substituted by the rations by the government, and that’s when, what probably caused a lot of diabetes, and even people just depressed, it leads to other diseases … I think we learned to get strong and to – just to be strong. It really made us strong in the mind, in the soul. To not ignore them, but to, to cope with them. […] I think that we’re very strong people. If we put our minds to it.” [Interview 1] | |

| 3. Healthy food and physical activity (titled the same). | “Healthier foods you know, that kind of don’t come around too much anymore. It’s more as a commodity, where a lot of us don’t have cars here and I’d like to have a more, like a one on one like that way again, where, where I’m living here at the handicapped place, and she came to us and showed us how to cook, ‘cause that was real – I really liked that… Talk about other things, do things together, and you know, like um, exercise. Exercise groups, you know, like that, that group exercising in there, and like – I don’t know, just a lot of things to take care of ourselves better, you know?” [Interview 12] |

| 4. Working with the healthcare system (titled “Positive healthcare experiences”). | “I can go to IHS. Again, there’s a lot of the doctors today have no clue of what we physically go through. They don’t even know. And to them, it’s you – I mean, every ER you’re another drunk. And they are pushed aside, and then we’re shoved out like it’s some cattle that’s gonna’ be slaughtered. And even at that, they get treated better than we do.” [Interview 9] |

| 5. Healthy communication and overcoming challenges (titled the same). | “… since I’ve been back up here, most of the ones don’t even necessarily know their cousins or relatives, and, you know, their, families, the older ones may know, you know. But, as far as becoming aware of you know, their environment and how they interact and how they need to treat one another, that’s kinda going to the wayside in, you know, kind of a sad thing.” [Interview 3] |

Note. IHS, Indian Health Services.

-

Understanding chronic illnesses (titled Ongoing conditions and self-care). Interview participants who discussed seeking and having knowledge of their chronic illnesses, who were active problem-solvers, and who took ownership of their chronic illnesses also discussed being able to manage their illnesses better than those who did not mention these actions. Therefore, this gathering will include information on self-care, how to access information and specific local resources, and information about the most prevalent chronic illnesses on the Apsáalooke reservation with symptoms, risk factors, and hints for management. Participants will receive a published book about managing various chronic illnesses.

To facilitate participants’ problem solving and ownership, we developed a journal that includes a culturally consonant goal-setting tool. This tool is called Counting Coup, because, in the past, Apsáalooke warriors could carry a coup stick to which they could add a feather when they achieved a brave war deed such as touching the enemy with their hand or coup stick and coming away unharmed. The concept of Counting Coup in Báa nnilah will include having participants make goals for themselves related to caring for themselves, while fulfilling their various roles such as mother/father, sister/brother, and wife/husband. The journal will discuss how community members can envision themselves as riding into battle with their health and can add feathers to their coup stick, which includes drinking water versus sugar-sweetened beverages, walking, or using positive communication—all of these to be resilient and strong for their family and community, and for future generations. Participants will discuss their feathers with their supportive partners, to support collaborative problem solving and deeper ownership of their personal process.

-

Historical and current trauma and loss, and resilience (titled Daasachchuchik [Strong Heart]). The interview included a question asking how trauma and loss affected coping with chronic illnesses. All interviewees and community member data analysts shared examples of how trauma and loss negatively impacted their and their family members’ chronic illness self-management. Due to the importance and frequency of this topic, we will dedicate an entire gathering to this issue and include trauma-informed intervention content throughout the gatherings. For example, Aakbaabaaniilea will discuss how the gatherings will be a place of healing, connection, hopefulness, and safety. In another gathering, we will provide a chronic illness symptom cycle diagram (e.g., pain, depression, sleeping problems) that is overlaid with a healing circle that includes practices for breaking out of the symptom cycle. Many of the practices are specific to the Apsáalooke culture—such as listening to or singing traditional lullabies, practicing traditional ceremonies, and maintaining spiritual connections.

In the Daasachchuchik gathering, participants will receive information on the impacts of loss and grief and how Apsáalooke cultural values and resilience can counter them. Examples of what community members may feel and say during stages of grief and healing will be reviewed during this gathering, and participants will complete an exercise in their supportive partnership, where they assess their losses and resilience through a traditional Apsáalooke flower design. Participants will be provided with additional options for dealing with the impacts of loss and trauma and connecting with mental health professionals.

-

Healthy food and physical activity (titled the same). Many participants mentioned the importance of food and exercise in managing their chronic illnesses and navigating the challenges of inadequate access to healthy food and places to exercise. In response to the question on trauma and loss, interview participants shared how changes in access to traditional foods and the provision of commodity foods (provided to American Indians through the federal Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations), have negatively impacted their health, increased chronic illnesses, and decreased their ability to manage chronic illnesses.

In this gathering, program participants will be provided locally and culturally relevant nutrition and exercise information. Examples of nutrition information will include how to shop for healthy food, read a food label, and portion sizes. They will participate in an activity to understand the amount of sugar in beverages. In addition, participants will be provided exercise bands and a handout with local community members demonstrating exercises. All gatherings will begin with a shared healthy meal.

-

Working with the healthcare system (titled “Positive healthcare experiences”). Interview participants discussed a number of strategies for working with the healthcare system that could positively impact chronic illness management including: learning how to engage with the healthcare system, being assertive with their healthcare, accessing timely and quality care, having a regular provider who cares about them, having good communication with providers, and understanding their medications. Multiple participants mentioned that negative interactions with the Indian Health Service were barriers to their health.

This gathering was developed to address these topics and includes a letter for participants to give to their healthcare provider and tips for developing a positive relationship with healthcare providers and learning how to problem-solve issues with the healthcare system. The letter for the healthcare provider is intended to be handed to a provider by the participant and will include advice for the provider on what they can do to help build a positive relationship with the participant and provides culturally specific contextual information to improve communication. Participants will also receive tools to help prepare for doctor visits and to understand and manage medications. Participants will also watch a DVD that was developed in one of our prior research projects that focuses on how to have positive interactions with the healthcare system and what individuals can do to take care of their health on a daily basis, because most health decisions are made outside of a clinic setting.

-

Healthy communication and overcoming challenges (title the interviews, participants often mentioned communication challenges and the importance of positive and healthy communication with family members, friends, and the healthcare system to best manage their chronic illnesses. This gathering will provide information on the importance of speaking and acting for themselves and their families for better health while still maintaining honor and respect for others. It will include tools to strengthen positive communication, including tips for understanding and working with the majority culture and ways to overcome challenges, which empowers participants to make and maintain healthy changes in their lives. Supportive partnerships will role-play healthy conflict resolution using scenarios taken from the interviews and data analysis discussions.

The final gathering (closing and graduation) will include the development of an individual action plan for going into the future and encouraging participants to be mentors to others with chronic illnesses in their community. There will also be a graduation ceremony where the participants receive a certificate of completion.

4. Discussion

This study was guided by our research question: How can a CBPR method grounded in Indigenous cultural values and approaches guide the development and delivery of a chronic illness self-management program? The objectives of this study were to describe how: 1) qualitative interview data informed both content and approach of a culturally consonant chronic illness self-management program for Apsáalooke tribal members, and 2) Apsáalooke cultural values provided for a strengths-based program.

The CAB of our long-standing partnership identified chronic illness management as the focus of this project, which led to the creation of the Báa nnilah program. As in the past, we used a CBPR approach grounded in a decolonizing research process. We conducted interviews with community members with chronic illnesses and reviewed literature on chronic illness self-management interventions. We developed a locally-based conceptual framework for understanding chronic illness management and intervention content and approach grounded in the local culture.

Our analysis process differed from thematic analysis in two primary ways. First, a typical approach to thematic analysis is to have one study team member code the qualitative data with an additional check for reliability assessed by another team member. Our analysis consisted of 8–16 team members sitting together for 60 h together listening to each interview and conducting collaborative analysis. This method provided constant real-time reliability checks with deep listening to each team member’s contributions and discussions. All analysts could ask questions, for clarification, or for further detail during the discussions. Second, in typical thematic analysis, the analyst works to keep at a distance from the data while coding, intentionally not including themselves in the analysis decisions. Our analysis was intentionally relational in that each analyst identified how they related to the story by looking into their own hearts to see what touched them in the story. In discussions, community member analysts (and to a lesser extent university member analysts) related each story to their personal story or a family member’s story. Relationality is a key concept in conducting research using Indigenous Research Methods (Wilson, 2008; Kovach, 2010a, 2010b). This method broadened the analysis and was consonant with practices of the local culture. Thus, this approach addresses existing health inequities that originated with colonization and avoids further colonizing behavior.

The extent literature discusses four criteria for enhancing trustworthiness in qualitative research projects: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Shenton, 2004). Credibility refers to confidence that the researchers have accurately recorded the phenomenon under study and was established by aligning our interview questions with literature and community views of important aspects of chronic illness management; letting participants know that there were no right answers to the questions and that they could stop the interview at any time or not answer any question; member checking data; ensuring credibility of the interviewer; and reporting similarities and differences with the gold standard chronic illness self-management program. Transferability is the “extent to which the findings of one study can be applied to other situations” (Shenton, 2004). Shenton (2004) stated that a job of future researchers is to assess their ability in transferring results and conclusions from earlier studies into their situation, which is enabled through this study. Dependability is established by providing information here on a) the research design and its implementation, b) the operational detail of data gathering, and c) reflective appraisal of the project. The criterion of confirmability assesses the steps to ensure that the “work’s findings are the results of the experiences and ideas of the informants, rather than the characteristics and preferences of the researcher.” Tables 1 and 2 provide examples of how insights from interviews directly informed content and analysis.

One of the dominant themes that emerged from the data analysis was the many ways that historical and current loss impacted the development, understanding, and self-management processes of chronic illnesses among community members. For example, historical and current losses were linked to mental and physical health, feelings of isolation, and changes in diet. Many participants said mental health factors such as stress, grief, and depression were linked to physical health outcomes and their ability to manage chronic illnesses in a healthy manner. By directly tailoring the specific needs and experiences of chronic illness management in the community to our intervention (please also see Real Bird et al., 2016 for more details) we were able to not only validate community members’ experiences and difficulties in managing chronic illness but also incorporate healthy coping strategies already being practiced by community members into our intervention.

In the interviews, participants also articulated many strategies that helped and hurt when managing their chronic illness. For example, many participants and analysts spoke about how changes in access to traditional foods and the introduction of novel and commodity foods to their diet (e.g., white flour, corn syrup, lard) not only contributed to the prevalence of chronic illnesses in the community but also continued to severely limit how they were able to manage their chronic illnesses successfully. Community members spoke about the importance of eating healthy food and being physically active when managing their chronic illness; therefore an entire gathering is dedicated to this topic. Other actions community members felt helped them better manage their chronic illnesses that emerged as themes in the data included spirituality and faith, social connections, relationships and support, knowledge about their health condition, coping with grief, loss and stress, being a self-advocate and taking action, developing healthy relationships with health care providers, speaking good words, and having a positive attitude. Each of these identified needs and local best practices found in the interviews with community members were built into our intervention, thus demonstrating a direct link between the qualitative data analysis and the intervention. As such, our intervention is tailored to the specific needs and experiences of chronic illness management in the community and incorporates their experiences, impressions, and understandings about what helped and hindered chronic illness management.

This study also directly addresses a knowledge deficit in current evidence-based interventions for chronic illness self-management—namely, not including Indigenous views and perspectives. Health inequities in chronic illness rates and earlier deaths from chronic illnesses among Indigenous populations demand interventions that are developed in partnership with Indigenous communities that utilize specifics of managing chronic illnesses in these communities. Building the Báa nnilah program from the ground up versus adapting an existing program resulted in significant differences from existing interventions in both intervention content and approach. This method was deemed more likely to positively impact program adherence and satisfaction and tangible social and health behavior outcomes.

A primary difference from existing chronic illness self-management programs is the centrality of spirituality and language. Interview participants and community analysts shared that spirituality greatly impacts and guides the hearts, minds, and actions of community members managing chronic illnesses. Appropriately, we incorporated spirituality throughout our program. Because the Apsáalooke language is primarily oral, language is used in appropriate ways such as titles and also may be used by facilitators when leading gatherings.

Content differences between existing chronic illness self-management programs and our program include the culturally consonant goal setting tool, the use of trauma-informed material across the gatherings, with one gathering devoted to historic and current trauma and loss, information to improve relationships with healthcare providers, and recommendations to strengthen healthy communication. Although content areas including nutrition, exercise, and education regarding chronic conditions (Lorig et al., 2013; NCOA, 2018) are included in both existing programs and our program, the approach for delivering the content is different.

The development and use of an Apsáalooke-specific method for goal setting (Counting Coup) addresses a deficit inherent in implementing other chronic illness self-management programs in Indigenous settings. In the literature, we noticed one goal setting tool developed for a non-Western audience (Garner et al., 2011) and none developed for use in chronic illness management programs.

Another primary difference in content between our program and chronic illness programs developed for the majority culture is the focus on historical and current trauma and loss. This topic was discussed in the interviews and analysis as a primary factor that underlies chronic illness self-management in the community. Providing trauma-informed content throughout the gatherings and dedicating an entire gathering to discussing the impacts of trauma and loss explicitly validates what was shared in the interviews. Our findings are similar to Warren et al. (2009), who in developing and implementing a chronic illness self-management program with Indigenous Australians, incorporated trauma-informed content to address the finding that many community members were not ready for self-management because they were preoccupied dealing with grief and loss.

Other chronic illness self-management programs include working with healthcare providers to improve patient-provider relationships, but we do not know of other programs that provide information to participants on bridging cross-cultural relationships. The final content area difference is a focus on healthy communication. Interview participants and community members commented on how negative communication between community members and between community members and health care providers can interfere with chronic illness self-management.

Approach differences between Báa nnilah and other chronic illness self-management programs include learning through advice given from others, learning through personal and collective story, and the use of supportive dyads. We will recruit lay community members who are role models for positively managing their chronic illnesses to become program facilitators. They will provide credibility as they understand both the struggle of managing a chronic illness as well as the culture.

Regarding learning through advice from others, some self-management programs, such as the CDSMP, discourage lay leaders from giving advice and train facilitators to teach from a provided script. This method is not an appropriate practice in the Apsáalooke community, as providing advice is a strong cultural practice that has been nurtured within the community over time. Indeed, our program is titled Báa nnilah., which describes the practice of giving advice, and the facilitators are referred to as Aakbaabaaniilea, “the ones who give advice.” Advice to each other will happen in sharing circles, which have similarities to group medical visits and have proven to be effective for chronic illness self-management (Nuovo, 2007; Trento et al., 2001). Sharing circles have been used effectively in health research with other Indigenous communities, where community members can generate solutions by “talking it out” (Affonso et al., 1996).

The final difference in approach between other chronic illness self-management programs and ours is in the use of supportive dyads within the group setting. Other chronic illness programs solely utilize a group setting, yet we identified a need for a further layer of support in view of interview participants’ sharing feelings of loneliness and isolation due to their chronic illness.

Though many self-management programs focus on older populations, American Indians/Alaska Natives are more likely to report risk factors for prevalence of and mortality from chronic illness at a significantly younger age than other ethnic groups (Amparo et al., 2011; Heron, 2013; IHS, 2015). Therefore, we will implement the intervention with those ages 25 and older.

4.1. Limitations

The Báa nnilah program emerged out of a particular culture and community and what helps and hinders chronic illness self-management may be different across communities, including different Indigenous nations. We believe that the intervention we developed is more appropriate for other Indigenous Nations than interventions developed without Indigenous voices. A limitation is that interviews were not conducted with adolescents and young adults, and thus the developed intervention may not be effective for these age groups who may present different issues and support needs from older community members. In addition, community members who provided stories and helped to build the intervention may not represent the entire Apsáalooke Nation as they were not a random sample.

5. Conclusions

The importance of building a chronic illness self-management program from the ground up versus implementing or adapting an existing program is apparent when looking at the differences between the Báa nnilah program and existing chronic illness self-management programs. We believe that by grounding the program in an Apsáalooke context, utilizing traditional methods of knowledge transmission, and harnessing cultural strengths to improve community health, there is a greater likelihood of lasting impacts on individual and community health (Bishop et al., 2014). We do not know of another locally developed conceptual framework for understanding chronic illness management that has been tested using a community-based intervention in an American Indian community.

This culturally consonant intervention, and the process by which it was developed, are potentially applicable to other communities and showcase a novel structure for chronic illness self-management programs. Future research should focus on implementation of the program and testing the ability of the program to improve chronic illness self-management.

References

- Affonso DD, Mayberry L, Inaba A, Matsuno R, Robinson E, 1996. Hawaiian-style “talkstory”: psychosocial assessment and intervention during and after pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs 25, 737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amparo P, Farr SL, Dietz PM, 2011. Chronic disease risk factors among American Indian/Alaska Native women of reproductive age. Prev. Chronic Dis 8, A118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin LM, Hollow WB, Casey S, Hart LG, Larson EH, Moore K, Lewis E, Adrilla CHA, Grossman DC, 2008. Access to specialty health care for rural American Indians in two states. J. Rural Health 24, 269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JG, Iwasaki Y, Gottlieb B, Hall D, Mannell R, 2007. Framework for Aboriginal-guided decolonizing research involving Metis and First Nations persons with diabetes. Soc. Sci. Med 65, 2371–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battiste M (Ed.), 2000. Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, BC. [Google Scholar]

- Benzinger CP, Roth GA, Moran AE, 2016. The global burden of disease study and the preventable burden of NCD. Glob Heart 11, 393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop R, Ladwig J, Berryman M, 2014. The centrality of relationships for pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J 51, 184–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K, 2002. A model of self-regulation for control of chronic disease. J. Am. Med. Assoc 288, 2469–2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B, Noonan C, Nord M, 2007. Prevalence of food insecurity and health-associated outcomes and food characteristics of Northern plains Indian households. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr 1 (4), 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cheney AM, Newkirk C, Rodriguez K, Montez A, 2018. Inequality and health among foreign-born latinos in rural borderland communities. Soc. Sci. Med 215, 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran P, Geller A, 2002. The melting ice cellar: what Native traditional knowledge is teaching us about global warming and environmental change. Am. J. Public Health 92, 1404–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran PA, Marshall CA, Garcia-Downing C, Kendall E, Cook D, McCubbin L, et al. , 2008. Indigenous ways of knowing: implications for participatory research and community. Am. J. Public Health 98, 22–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donatuto JL, Satterfield TA, Gregory R, 2011. Poisoning the body to nourish the soul: prioritising health risks and impacts in a Native American community. Health, Risk & Society 13, 103–127. [Google Scholar]

- Duran B, 2011. The promise of health equity: advancing the discussion to eliminate disparities in the 21st century In: 32nd Annual Minority Health Conference. Chapel Hill, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Duran E, Firehammer J, 2014. Story sciencing and analyzing the silent narrative between words: counseling research from an indigenous perspective In: Gorski R.G.a.P. (Ed.), Decolonizing “Multicultural” Counseling and Psychology: Visions for Social Justice Theory and Practice. George Mason University: Springer SBM. [Google Scholar]

- Garner H, Bruce MA, Stellern J, 2011. The goal wheel: adapting Navajo philosophy and the medicine wheel to work with adolescents. J. Spec. Group Work 36, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Garroutte E, Westcott K, 2008. “The stories are very powerful”: a Native American perspective on health, illness, and narrative In: O’Brien S (Ed.), Religion and Healing in Native America: Pathways for Renewal. Praeger, Westport, Connecticut, pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett J, Held S, Knows His Gun McCormick A, et al. , 2017. What touched your heart? Collaborative story analysis emerging from an Apsáalooke cultural context. Qual. Health Res 27 (9), 1267–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatala A, Morton D, Njeze C, Bird-Naytowhow K, Pearl T, 2019. Research on media framing of public policies to prevent chronic disease: a narrative synthesis. Soc. Sci. Med 230, 122–130.31009878 [Google Scholar]

- Hensley-Quinn M, Shawn K, 2006. American Indian Transportation: Issues and Successful Models. RTAP National Transit Resource Center InfoBrief No. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Heron M, 2013. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2010 National Vital Statistics Reports. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron M, 2018. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2016 National Vital Statistics Reports. National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge FS, Pasqua A, Marquez CA, Geishirt-Cantrell B, 2002. Utilizing traditional storytelling to promote wellness in American Indian communities. J. Transcult. Nurs 13, 6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service, 2015. Indian Health Disparities. Indian Health Service, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Institute Of Medicine, 2012. Living well with chronic illness: a call for public health action In: Institute of Medicine. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan V, 2010. Community-based participatory research with native American communities: the chronic disease self-management program. Health Promot. Pract 11, 888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe JR, Young RS (Eds.), 1994. Diabetes as a Disease of Civilization: the Impact of Culture Change on Indigenous Peoples. Mouton de Gruyter, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach M, 2010a. Conversational method in indigenous research. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev 5, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach M, 2010b. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations and Contexts. University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Lavalee L, 2009. Practical application of an indigenous research framework and two qualitative indigenous research methods: sharing circles and anishnaabe symbol-based reflection. Int. J. Qual. Methods 8, 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Ritter P, Stewart A, Sobel D, Brown B Jr., Bandura A, et al. , 2001. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med. Care 39, 1217–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Ritter P, Ory MG, Whitelaw N, 2013. Effectiveness of a generic chronic disease self-management program for people with type 2 diabetes: a translation study. Diabetes Educat. 39, 655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Sobel D, Stewart A, Brown B, Bandura A, Ritter P, et al. , 1999. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med. Care 37, 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, Singh A, Johnson TJ, 2018. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc. Sci. Med 219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt GV, Hazel KL, Allen J, Stachelrodt M, Hensel C, Fath R, 2004. Unheard Alaska: culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. Am. J. Community Psychol 33, 263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan KM, Hoskin M, Kozak D, Kriska AM, Hanson RL, Pettitt DJ, et al. , 1998. Randomized clinical trial of lifestyle interventions in Pima Indians: a pilot study. Diabet. Med 15, 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council On Aging, 2018. Title III-D Highest Tier Evidence-Based Health Promotion/Disease Prevention Programs National Council On Aging. https://www.ncoa.org/wp-content/uploads/Title-IIID-Highest-Tier-EBPs-March-2018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nuovo J (Ed.), 2007. Chronic Disease Management. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ory MG, Ahn S, Jiang L, Lorig K, Ritter P, Laurent DD, et al. , 2013. National study of chronic disease self-management: six-month outcome findings. J. Aging Health 25, 1258–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T, 2005. Adherence to medication. NEJM 353, 487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real Bird S, Held S, McCormick A, Hallett J, Martin C, Trottier C, 2016. The impact of historical and current loss on chronic illness: perceptions of crow (apsaa-looke) people. Int. J. Indig Health 11 (1), 198–210. 10.18357/ijih111201614993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigney L, 1999. Internationalization of an indigenous anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies: a guide to indigenist research methodology and its principles. Wicazo Sa Rev. 14, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Ingram BL, Swendeman D, Lee A, 2012. Adoption of self-management interventions for prevention and care. Prim Care 39, 649–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenton A, 2004. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Simonds V, Christopher S, 2013. Adapting Western research methods to indigenous ways of knowing. Am. J. Public Health 103 (12), 2185–2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonds VW, Christopher S, Sequist TD, Colditz G, Rudd RE, 2011. Exploring patient-provider interactions in a Native American community. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 22 (3), 836–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L, 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books Ltd, London. [Google Scholar]

- Stillwater B, 2007. Living Well Alaska. Alaska Section of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Chronicle. www.hss.state.ak.us/dph/chronic/ (Alaska Division of Public Health; ). [Google Scholar]

- Stillwater B, 2012. Living well Alaska: an evaluation of a distance delivery project In: Fenaughty A (Ed.), Chronic Disease Prevention Health Promotion Chronicles. Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Anchorage, AK. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S, 2008. Chronic disease management: what is the concept? Can. J. Nurs. Res 40, 7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tom-Orme L, 2000. Native Americans explaining illness: storytelling as illness experience In: Whaley BB (Ed.), Explaining Illness: Research, Theory, and Strategies. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey, pp. 237–257. [Google Scholar]

- Trento M, Passera P, Tomalino M, Bajardi M, Pomero F, Allione A, et al. , 2001. Group visits improve metabolic control in type 2 diabetes: a 2-year follow-up. Diabetes Care 24, 995–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vital Statistics Unit, 2018. Montana Vital Statistics 2016 Office of Epidemiology and Scientific Support. Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, Helena, Montana. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B, 2010. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health 100 (Suppl. 1), S40–S46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward BW, Schiller JS, 2013. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Prev. Chronic Dis. 10, E65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warne D, Frizzell LB, 2014. American Indian health policy: historical trends and contemporary issues. Am. J. Public Health 104, S263–S267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren K, Coulthard F, Harvey P, 2009. Elements of successful chronic condition self-management program for Indigenous Australians In: National Rural Health Conference, pp. 1–13 (Australia: ). [Google Scholar]

- West R, Stewart L, Foster K, Usher K, 2012. Through a critical lens: indigenist research and the dadirri method. Qual. Health Res. 22, 1582–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L, Ratja S, Ivanich J, Plavin J, Mullany A, Moto R, Kirk T, Goldwater E, Johnson R, Dombroski K, 2019. Community mobilization for rural suicide prevention: process, learning and behavioral outcomes from promoting community conversations about research to end suicide (PC CARES) in Northwest Alaska. Soc. Sci. Med 232, 398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2003. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action In: World Health Organization. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S, 2008. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods Black Point. Fernwood Publishing, Nova Scotia. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock C, Korda H, Erdem E, Pedersen S, Kloc M, Tollefson E, 2013. Chronic disease self-management program (CDSMP) process evaluation. IMPAQ Int. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/programs/2017-02/CDSMPProcessEvaluationReportFINAL062713.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Zavala M, 2013. What do we mean by decolonizing research strategies? Lessons from decolonizing, Indigenous research projects in New Zealand and Latin America. Decolonization: Indig. Educ. Soc 2, 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman S, Haley J, Roubideaux Y, Lillie-Blanton M, 2004. Health service access, use and insurance coverage among American Indians/Alaska Natives and whites: what role does the Indian health service play? Am. J. Public Health 94, 53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]