PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Consider serum sickness and avoid further infusions in patients who develop fever, arthralgia, and elevated inflammation parameters around 10 days after treatment with chimeric monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab.

Rituximab is not licensed for treatment of MS, but has shown promising effects in phase II and real-life studies.1,2 Rituximab is now the most frequently used disease-modifying drug in Sweden3 and is increasingly used in Norway.

Whereas acute infusion reactions are caused by B-cell lysis and mast cell degranulation, serum sickness is a delayed (type III) hypersensitivity reaction caused by an immune response against foreign protein, usually presenting around 10 days after the infusion.3 Repeated infusion in patients who have experienced serum sickness can induce severe allergic reactions.4 We here report cases of rituximab-induced serum sickness in patients treated for MS.

Case

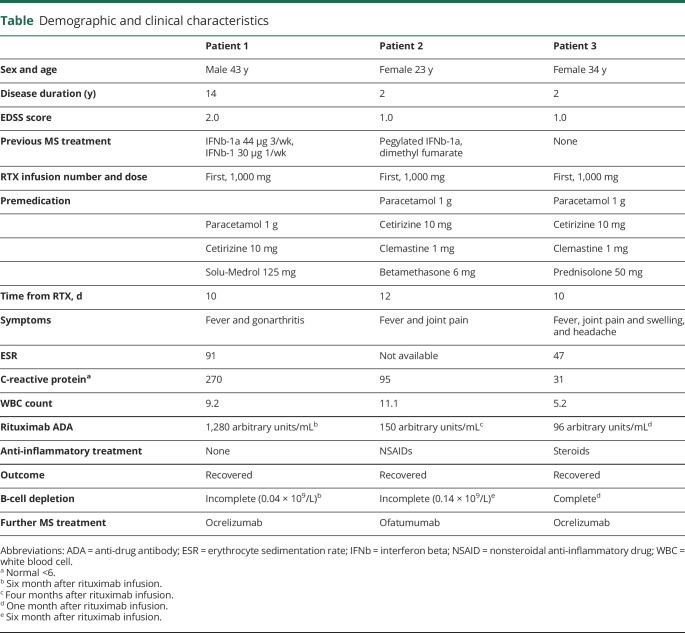

Demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in the table.

Table.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Patient 1 switched treatment to rituximab because MRI revealed a contrast-enhancing cerebral lesion. He had no infusion reactions, but 10 days later, he developed fever up to 40°C and painful swelling of the right knee, the next day less pronounced in the left knee. C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were high, and thrombocytes were low (113; normal 145–390 × 109/L). Arthroscopy revealed synovitis with elevated synovial fluid cell count (59.2 × 109/L). He was treated at the intensive care unit with broad-spectrum antibiotics, but there was no bacterial growth in synovial fluid or in blood. He was discharged from hospital after 10 days and gradually recovered completely. Anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) against rituximab were high, and B-cell depletion was incomplete.

Patient 2 switched to rituximab because of side effects from interferon beta and dimethyl fumarate. She experienced no infusion reaction, but 14 days later, she sought medical care because of fever and increasing joint pain for 2 days. The pain was migrating from the right to the left hip, and she could not stand on her legs because of severe pain. She was tender on palpation of the ankles, hips, and rib cage, but had no obvious joint swelling. CRP increased from 14 to 95 and white blood cell count from 11.1 to 11.8. She required a combination of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids to relive the joint pain. Extensive investigations for infectious agents were negative. The symptoms resolved spontaneously over 2 weeks. She developed high ADA levels and incomplete B-cell depletion.

Patient 3 received rituximab in a randomized trial between rituximab and dimethyl fumarate (RIFUND-MS; NCT02746744). She had moderate infusion-related side effects. After the infusion, she experienced headache and joint pain, followed by low-grade fever and chills. The joint pain escalated about 10 days after the infusion, and she sought emergency care because of severe pain in her hands, knees, and wrists. She had slightly elevated inflammatory parameters, was afebrile, and displayed slight swelling and tenderness of both wrists and finger joints with difficulties clenching her fists. No local signs of infection were present. The pain was not adequately relieved with NSAID and paracetamol/codeine, but rapidly resolved on prednisolone 30 mg daily with 5 mg taper every other day. She displayed high ADA levels but complete depletion of B-lymphocytes.

Discussion

ADAs in form of human antichimeric antibodies occur rather frequently during rituximab treatment and are associated with incomplete B-cell depletion, but so far, their clinical significance is unclear.5 Anti-rituximab ADAs in our patients were measured on a validated Meso Scale Discovery platform by electrochemiluminescence platform (adopted from GlaxoSmithKline). Tests can be provided by several laboratories listed at the BIOPIA website hosted by the Karolinska Institutet (ki.se/en/cns/biopia).

Serum sickness has been reported after rituximab treatment of other diseases.4,6 Immune complexes between the chimeric monoclonal antibody and ADA activate complement, and the deposition of these complexes in different organs causes an inflammatory reaction.7 The typical features of joint pain, increased systemic inflammatory parameters with varying degrees of fever and malaise 10–12 days after the first infusion, and high-titer ADA led us to the conclusion that our patients experienced serum sickness of variable intensity.

Two other monoclonal anti-CD20 antibodies are either licensed or under development for MS. Whereas rituximab has murine variable regions, ocrelizumab is humanized through grafting of murine complementarity-determining regions to human framework regions, whereas ofatumumab is fully human. All 3 patients tolerated retreatment with ocrelizumab or ofatumumab. This is expected because ADAs are rare after exposure to human and humanized monoclonal antibodies.

It is important to be aware of serum sickness because re-exposure after a first event may cause more severe reactions. In patients with typical symptoms and high levels of rituximab ADA, we advise treatment switch to a humanized anti-CD20 antibody or another disease-modifying drug.

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

The research leading to these results has in part been supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) contract MS-1511-33196 for Funded Research Project Standard CR8 with Karolinska Institutet for the project: “Rituximab in Multiple Sclerosis: A Comparative Study on Effectiveness, Safety, and Patient-Reported Outcomes.”

Disclosure

T. Holmøy has received speaker honoraria from Biogen, Sanofi, Genzyme, and Roche; has received honoraria for consultancy for Roche, Biogen, and Sanofi; and is involved in clinical trials sponsored by Roche and Biogen. A. Fogdell-Hahn has received unrestricted research grants from Biogen and Pfizer and has been invited speaker sponsored by Biogen, Sanofi, Merck, and Pfizer. A. Svenningsson is involved in a clinical trial sponsored by Sanofi. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:676–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alping P, Frisell T, Novakova L, et al. Rituximab versus fingolimod after natalizumab in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol 2016;79:950–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karmacharya P, Poudel DR, Pathak R, et al. Rituximab-induced serum sickness: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2015;45:334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar A, Khamkar K, Gopal H. Serum sickness and severe angioedema following rituximab therapy in RA. Int J Rheum Dis 2012;15:e6–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn N, Juto A, Ryner M, et al. Rituximab in multiple sclerosis: frequency and clinical relevance of anti-drug antibodies. Mult Scler 2018;24:1224–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Todd DJ, Helfgott SM. Serum sickness following treatment with rituximab. J Rheumatol 2007;34:430–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawley TJ, Bielory L, Gascon P, Yancey KB, Young NS, Frank MM. A prospective clinical and immunologic analysis of patients with serum sickness. N Engl J Med 1984;311:1407–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]