PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

A detailed clinical description of episodic ataxia type 5 will help identify this condition more readily.

Episodic ataxias (EA) are characterized by spells of incoordination and imbalance, often associated with progressive ataxia. We describe the clinical manifestations of 2 patients molecularly diagnosed with EA5.

Patient 1

A 31-year-old woman began experiencing episodes of unsteadiness at age 18.

The episodes started with numbness, incoordination, and slight weakness in the left thigh that spread to the entire left lower limb, progressing to the left upper and right lower limbs. Obtundation, vertigo, word-finding difficulty, and dysarthria were also present. During the episodes, objects fell out of her hands, her gait became wide-based and unsteady, and she experienced mild generalized headache. On occasion, she also experienced brief loss of consciousness with muscle relaxation, followed by generalized weakness and incoordination on recovery.

The patient reported 2 episodes per month, which started gradually and progressed to maximal severity within 4–12 hours after onset. The episodes were followed by a phase with stable symptoms lasting about 12 hours, then by gradual recovery with a return to normal within 48–72 hours. She also experienced milder episodes of shorter duration.

Triggering factors were lack of sleep, fatigue, alcohol intake, intercurrent infection, copious meals, and psychological stress. Following the adoption of lifestyle measures (regular sleep schedule, light physical exercise, and lower levels of job stress), the patient has reported no new episodes in the past few months.

Examination during the episodes revealed dysmetria on left finger-to-nose and heel-to-knee tests, left-sided hypoalgesia, and grade 4+/5 left hemiparesis. Other findings included wide-based gait, tandem gait requiring support, and Romberg test with retropulsion. Intercritical examination was normal.

Cranial MRI, MRI angiography, and CSF analysis were normal. Two intercritical EEGs recorded normal cortical activity. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of CACNB4 identified the heterozygote variant c.311G>T (p.Cys104Phe); NGS of episodic ataxia genes CACNA1A, KCNA1, and SLC1A3 was negative.

Patient 2

A 73-year-old man, father to patient 1, described bouts of vertigo and unsteady gait after drinking small amounts of beer; these bouts lasted several hours and had been occurring since age 20. At age 61, after several days of a heavy workload and lack of sleep, he woke up with vertigo and unsteadiness that prevented independent stance and gait. On examination, stance was wide-based, walking was impossible, and the Romberg test showed sway with no preference for either side. The patient gradually recovered in 10 days. Cranial MRI, Doppler examination of the supra-aortic arteries, and caloric labyrinthine tests were normal. NGS identified CACNB4 c.311G>T (p.Cys104Phe) in heterozygosis. On examination at age 73, gait was wide-based and tandem gait was impossible.

Clinically, EAs are heterogeneous. Ataxic spells are variably accompanied by vertigo, tinnitus, blurred vision, diplopia, myokymia, tremor, obtundation, or headache and may coexist with epilepsy and alternating hemiplegia. The spells may appear spontaneously and can be triggered by alcohol or coffee intake, anxiety, fatigue, lack of sleep, or exercise. Permanent ataxia and cerebellar atrophy may develop after years of disease duration.1,2

Genetically, EAs are also heterogeneous diseases, with autosomal dominant inheritance.1,2 EA5 has been linked to the c.311G>T (p.Cys104Phe) missense mutation in CACNB4, as in our patients; however, no clinical description was provided.3

The aim of this report is to describe the clinical characteristics of ataxic episodes in EA5. In patient 1, unilateral numbness, weakness, headache, and loss of consciousness were present, in addition to gait ataxia, leading us to include vascular disease, migraine with aura, and epilepsy in the differential diagnosis. Psychological and job stress that triggered attacks led us to also consider an anxiety disorder.

Low levels of alcohol intake have been shown to cause transient cerebellar ataxia4 and are a well-known precipitating factor for EA.1,2 In patient 2, ataxic spells were caused by drinking small amounts of beer.

In patient 2, a prolonged episode was caused by fatigue and lack of sleep, triggers similar to those observed in patient 1. On examination, at age 73, the patient was found to have mild permanent cerebellar ataxia.

Episodes caused by EA5 may exhibit multiple clinical manifestations besides cerebellar ataxia, vary in severity, and cause late permanent ataxia. Ataxic spells are similar in EA5 and EA2, with onset later in EA5.3

Pharmacologic prophylaxis was not necessary in our patients. However, because EA5 episodes may be prevented by lifestyle measures, as in patient 1, and by acetazolamide administration,1–3 a detailed description of the clinical features, examination findings, and triggering factors of this rare condition may make it more readily recognizable. To our knowledge, our patients represent the third family3 reported to have genetically confirmed EA5.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Helen Casas and Laura Casas for their English editing of the text.

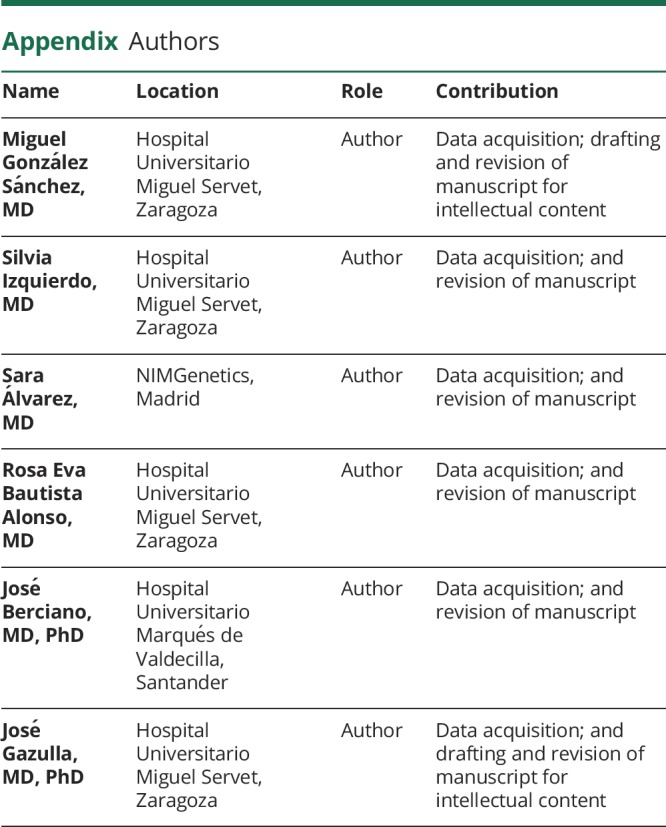

Appendix. Authors

![]()

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Choi KD, Choi JH. Episodic ataxias: clinical and genetic features. J Mov Disord 2016;9:129–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riant F, Vahedi K, Tournier-Lasserve E. Ataxies épisodiques génétiques. Rev Neurol 2011;167:401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escayg A, De Waard M, Lee DD, et al. Coding and noncoding variation of the human calcium-channel beta4-subunit gene CACNB4 in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy and episodic ataxia. Am J Hum Genet 2000;66:1531–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Setta F, Jacquy J, Hildebrand J, Manto MU. Ataxia induced by small amounts of alcohol. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;65:370–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]