PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids demonstrates clinical and neuroimaging heterogeneity.

Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS) is an autosomal dominant disease caused by mutations in colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R).1 HDLS is associated with progressive white matter disease with diverse clinical presentation, including behavioral and personality changes, dementia, seizures, pyramidal signs, ataxia, and parkinsonism. The role of brain MRI in the diagnosis is well established, showing white matter lesions mainly with frontoparietal distribution, spreading out from the periventricular and deep white matter into the subcortical areas, with corresponding atrophy.2

We describe the heterogeneity of a family with cognitive decline in which HDLS was considered in the diagnostic approach.

Case

Patient 1

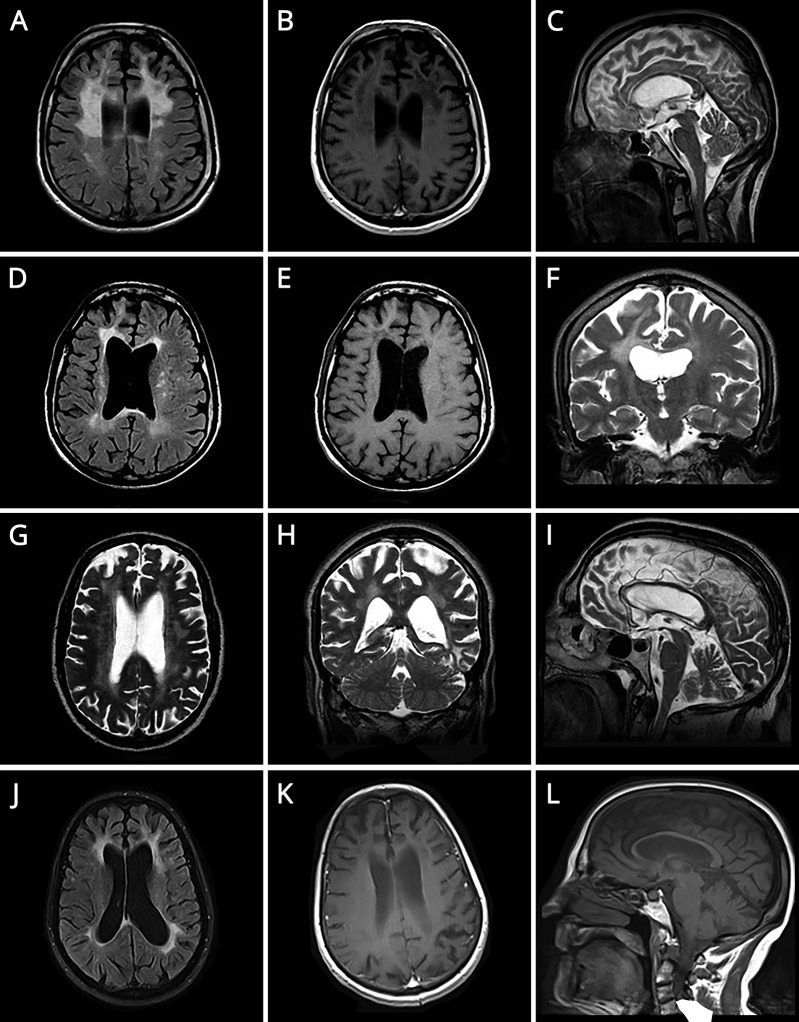

A 39-year-old man, former alcoholic, presented with progressive behavioral changes. Family history of dementia in his mother, 2 maternal uncles, and grandfather, the first with frontotemporal features, was known. In the previous year, his behavior became bizarre, searching for food in garbage, picking up cigarette butts from ashtrays in cafés, and parking cars on the street. His speech became poor. Self-care and hygiene neglect was noted. He demonstrated binge eating and urinary incontinence. Neurologic examination revealed inattention, apathy, impulsivity, abstract thinking and planning difficulties, and poor language. He scored 27/30 in Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and 10/18 in Frontal Assessment Battery. He had no insight into his behaviors and deficits. The remainder of the neurologic examination was unremarkable. Neuropsychological testing revealed executive dysfunction and memory, visuoconstructional, and calculation impairment. Blood tests for other causes of dementia were unremarkable. Brain MRI is presented in figure A–C. Considering clinical presentation compatible with frontal syndrome, family history suggestive of autosomal dominance inheritance, and MRI findings, genetic study for CSF1R was performed, revealing a pathogenic, heterozygous mutation, c.2275T>C (p.Ser759Pro), confirming the diagnosis of HDLS. In the following months, major neurologic deterioration was noted, with progressive cognitive decline, seizures, sphincter incontinence, and gait inability.

Figure. Brain MRIs.

(A) Axial T2 FLAIR. (B) Axial T1 SE GAD. (C) Sagittal T2 TSE. (D) Axial T2 FLAIR. (E) Axial T1 SE. (F) Coronal T2 TSE. (G) Axial T2 TSE. (H) Coronal T2 TSE. (I) Sagittal T2 TSE. (J) Axial T2 FLAIR. (K) Axial T1 SE GAD. (L) Sagittal T1 SE). (A–F and J–L) Three patients presented T2 FLAIR hyperintense extensive and confluent lesions in frontoparietal white matter, asymmetric with frontal predominance and involving the corpus callosum, with decreased signal on T1 and no gadolinium enhancement, and corresponding volume loss. (G–I) Diffuse and confluent T2 hyperintense lesions in both hemispheres, slightly asymmetric with no involvement of corpus callosum, along with prominent volume loss.

Patient 2

A 42-year-old man, twin brother of patient 1, presented 2 years after with a 2-year course of behavioral changes. He was a smoker and an alcoholic. He left his job and started parking cars on the street. He revealed self-care neglect and inappropriate behavior, retrieving cigarette butts from the floor. Neurologic examination revealed impulsivity, abstract thinking and planning difficulties, verbal fluency, and visuoconstructional impairment and apraxia. He scored 25/30 in MMSE. The remainder of the neurologic examination was normal. Blood tests were unremarkable. Brain MRI is illustrated in figure D–F. Considering his brother's results, genetic study for CSF1R was performed, revealing the same mutation.

Patient 3

The twins' maternal uncle, a 70-year-old man with a history of bladder cancer in remission, hypertension, dyslipidemia, psoriasis, and alcoholism, presented with a 1-year history of cognitive and behavioral decline. He felt forgetful, had difficulty following conversations and expressing himself, was unable to sign his name or read, and stopped driving and going out alone. He became disinterested, stopped taking care of the house, and no longer fed his animals, with occasional emotional outbursts. He scored 16/30 in MMSE. Neurologic examination was otherwise normal. Formal neuropsychological testing demonstrated inattention and major deficits in manual dexterity, visuospatial construction, language, memory, and executive functions. Blood tests for other causes of dementia were normal. CSF analyses were remarkable for an increased amyloid 1–42, tau, and phosphorylated tau. Brain MRI is presented in figure G–I. After his nephew diagnosis, CSF1R was sequenced, and the same mutation was identified.

Patient 4

The twins' mother had been observed 6 years before for a 3-year course of cognitive decline. At age 54 years, she developed apathy and abulia, difficulty in recognizing faces, and progressive speech difficulty. She demonstrated impulsivity and inappropriate behavior. Neurologic examination revealed apathy, severe language (naming, comprehension, writing, and reading) and verbal fluency impairment, visual agnosia, and prosopagnosia. Otherwise, neurologic examination was normal. Laboratory studies were unremarkable. Brain MRI is shown in figure J–L. The patient died at age 60 years, with no definite diagnosis.

Discussion

Patients 1 and 2 presented in their late thirties with bizarre behavior and cognitive decline with frontotemporal features and MRI typical for HDLS.3,4 Family history of dementia, suggestive of autosomal dominant inheritance, namely their mother exhibiting clinical diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia, were key clues for the diagnosis. Patient 3, however, presented in late life with cognitive decline affecting multiple cognitive domains, suggesting a widespread involvement. MRI was also not typical for HDLS, revealing periventricular bilateral changes, suggestive of small vessel ischemic disease. Patient 4, retrospectively, exhibited the typical clinical picture and neuroimage for HDLS, but no definite diagnosis was made.

These cases highlight the clinical and neuroimaging heterogeneity of HDLS and illustrate the intrafamilial variability concerning the age at onset and clinical features.

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Rademakers R, Baker M, Nicholson AN, et al. Mutations in the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) cause hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Nat Genet 2011;44:200–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundal C, Van Gerpen JA, Nicholson AM, et al. MRI characteristics and scoring in HDLS due to CSF1R gene mutations. Neurology 2012;79:566–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axelsson R, Roytta M, Sourander P, Akesson HO, Andersen O. Hereditary diffuse leucoencephalopathy with spheroids. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1984;314:1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stabile C, Taglia I, Battisti C, Bianchi S, Federico A. Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS): update on molecular genetics. Neurol Sci 2016;37:1565–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]