Abstract

Fungivorous millipedes (subterclass Colobognatha) likely represent some of the earliest known mycophagous terrestrial arthropods, yet their fungal partners remain elusive. Here we describe relationships between fungi and the fungivorous millipede, Brachycybe lecontii. Their fungal community is surprisingly diverse, including 176 genera, 39 orders, four phyla, and several undescribed species. Of particular interest are twelve genera conserved across wood substrates and millipede clades that comprise the core fungal community of B. lecontii. Wood decay fungi, long speculated to serve as the primary food source for Brachycybe species, were absent from this core assemblage and proved lethal to millipedes in pathogenicity assays while entomopathogenic Hypocreales were more common in the core but had little effect on millipede health. This study represents the first survey of fungal communities associated with any colobognath millipede, and these results offer a glimpse into the complexity of millipede fungal communities.

Keywords: Diplopoda, Colobognatha, Brachycybe, millipede, mycophagy, entomopathogenicity, Apophysomyces, Mortierella, fungal diversity

1. Introduction

The Class Diplopoda, known colloquially as millipedes, represent some of the earliest known terrestrial animals, dating back to the early Devonian period ca. 412 million years ago (Wilson & Anderson 2004, Suarez et al. 2017). These early representatives were detritivores and likely played a role in early soil formation and the development of terrestrial nutrient cycling (Bonkowski et al. 1998, Lawrence & Samways 2003). Detritivorous millipedes continue to play a pivotal role in ecosystem processes, though herbivorous (Marek et al. 2012), carnivorous (Srivastava & Srivastava 1967), and fungivorous diets also exist among extant millipedes (Brewer et al. 2012, Marek et al. 2012).

Most fungivorous millipedes belong to the subterclass Colobognatha, which diverged from detritus-feeding millipedes 200–300 million years ago and possess a primitive trunk-ring architecture composed of a free sternum and/or pleurites (Brewer & Bond 2013, Rodriguez et al. 2018). However, these millipedes are characterized by derived rudimentary mouthparts adapted for feeding exclusively on succulent tissues such as fungi (Hopkin & Read 1992, Wilson & Anderson 2004, Wong 2018). Some taxa possess beaks composed of elongate mouthparts encompassing a fused labrum, gnathochilarium, and stylet like mandibles (Read & Enghoff 2018). Members of the Colobognatha are among the most understudied groups in Diplopoda despite their wide geographic distribution and ubiquity in natural history collections (Manton 1961, Hoffman 1980, Read & Enghoff 2009, Shorter et al. 2018). The ancient association between millipedes and fungi raises fascinating questions about interactions in early terrestrial ecosystems, and the possible role of fungi in diplopod success.

Most published records of fungal-millipede interactions are cases where millipedes graze on fungi in the environment (Bultman & Mathews 1996, Lilleskov & Bruns 2005) or where parasitic fungi infect millipedes (Kudo et al. 2011, Hodge et al. 2017). Among the most studied fungal associates of millipedes are specialist ectoparasitic fungi in the Laboulbeniales (Santamaria et al. 2014, Enghoff & Santamaria 2015, Reboleira et al. 2018) and obligate arthropod gut-associated trichomycetes (Wright 1979). However, in none of these interactions does the millipede strictly depend on fungi for survival as it seemingly does in the fungivorous millipede B. lecontii (Diplopoda: Platydesmida: Andrognathidae).

Brachycybe lecontii is most frequently found in multigenerational aggregations in decaying wood with visible fungal growth (Gardner 1975, Shelley et al. 2005). The known geographic range of B. lecontii extends across 13 U.S. states from eastern Oklahoma to western South Carolina, south to Louisiana, and north to southern West Virginia (Shelley et al. 2005, Brewer et al. 2012). Within its known range, B. lecontii is divided into at least 4 clades that are geographically separated and may represent independent cryptic species (Brewer et al. 2012).

Historically, only one study reported Brachycybe feeding on an identified fungus, an unknown species of Peniophora (Russulales) (Gardner 1975). However, observations of Brachycybe species interacting with various fungi (n = 65) from community science websites such as Bugguide.net and iNaturalist.org shows that the fungal communities associated with this genus are more diverse than have been formally described (Supplemental Table 1). Recently, several basidiomycete Polyporales have been confirmed directly from B. lecontii and from B. lecontii-associated wood (Kasson et al. 2016). Given the discovery that Polyporales have helped facilitate the evolution of large, communal colonies with overlapping generations in other arthropods (You et al. 2015, Kasson et al. 2016, Simmons et al. 2016), many interesting questions are raised regarding Brachycybe colonies and their association with Polyporales and allied fungi.

In an attempt to uncover which fungi, if any, are consistently associated with B. lecontii, this study surveys fungal associates of B. lecontii across its known geographic range using culture-based approaches. The use of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) barcoding on collected isolates allowed fine-scale identification and examination of culturable fungal communities. With a primary understanding of these fungal communities, we assessed diversity and applied a network analysis to determine the relationship between genetically and geographically distinct B. lecontii populations, their wood substrates, and associated fungal genera.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Collection sites & field methods

Millipede collection sites were primarily identified through Brewer et al. (2012) and Gardner (1975), and additional sites were identified based on the known range of B. lecontii. Sampling was targeted to collect millipedes from all four B. lecontii clades. Based on previous work by Brewer (2012), individual sites were expected to contain millipedes from a single clade, with no syntopy. In total, 20 sites were sampled, with 18 yielding colonies and solitary individuals, and 2 yielding individuals only. These sites were located in Arkansas, Georgia, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Brachycybe lecontii collection sites.

| Site | Collection reference | Millipede clade |

Level 4 ecoregion |

# millipedes sampled |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR1 | Gardner 1975 | 4 | 37A | 6 |

| AR2 | -------------- | 4 | 36B | 6 |

| AR3 | -------------- | 4 | 36C | 13 |

| AR4 | Brewer et al. 2012 | 4 | 37A | 22 |

| AR5 | -------------- | 4 | 36B | 14 |

| AR6 | -------------- | 4 | 36B | 12 |

| GA1 | Gardner 1975 | 1 | 66D | 9 |

| OK1 | Brewer et al. 2012 | 4 | 36D | 14 |

| SC1 | Brewer et al. 2012,Gardner 1975 | 1 | 66D | 22 |

| SC2 | Gardner 1975 | 1 | 45E | 4 |

| TN1 | Gardner 1975 | 3 | 69D | 42 |

| VA1 | Brewer et al. 2012,Gardner 1975 | 3 | 69D | 4 |

| VA2 | -------------- | 3 | 67I | 8 |

| VA3 | Gardner 1975 | 3 | 69D | 15 |

| VA4 | -------------- | 1 | 67H | 5 |

| WV1 | Brewer et al. 2012,Gardner 1975 | 3 | 69D | 29 |

| WV2 | -------------- | 3 | 69D | 24 |

| WV3 | -------------- | 3 | 69D | 4 |

| WV4 | -------------- | 3 | 69D | 12 |

| WV5 | -------------- | 3 | 69D | 36 |

At each site, decaying logs on the forest floor were overturned, examined, and replaced until colonies of B. lecontii were located. Colonies are defined as groups of two or more individuals, and were typically found on or near resupinate fungi covering the underside of the logs. When suitable colonies were found, individuals from single colonies were placed together in 25-ml sterile collection vials, often with a piece of the fungus-colonized wood they were on, and stored in a cooler on ice until processing. In addition, cross-sections of logs from which colonies were collected were sampled for wood substrate identification.

2.2. Millipede processing & isolate collection

All millipedes were maintained at 4°C until processing, which typically occurred within 3 d of initial collection. After surface sterilization in 70% ethanol, individuals were sexed, sectioned with a sterilized scalpel to remove tail and gonopod sections (Macias 2017). Tail portions were preserved in 95% ethanol for millipede genotyping using custom markers previously described by Brewer et al. (2012). Gonopods were also preserved from males to permit anatomical study. The remainder of the millipede was macerated in 500 μl of sterile distilled water, and a 50-μl sample was spread on glucose yeast extract agar (GYEA) amended with antibiotics to isolate fungi (Macias 2017). GYEA was made as follows: 1000 ml distilled water, 20 g agar, 2 g yeast extract, and 0.5 g MgSO4 (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), 10 g dextrose (BD and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), 1 g KH2PO4 (Ward’s Science, Rochester, NY, USA), 50 μg thiamine, 10 μg biotin, and 1 mL of microelement solution containing 500 μg Fe3+, 439 μg Mn2+, and 154 μg Zn2+. Antibiotics consisted of: 100 mg tetracycline hydrochloride (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and 10 mg of streptomycin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Cultures were sealed with parafilm and incubated at ambient conditions until growth was observed. Each colony-forming unit (CFU) was categorized by morphotype, counted, and recorded. One representative of each morphotype from each plate was retained and assigned an isolate number. Culture plates were retained for up to 3 weeks to ensure that slow-growing fungi were counted and sampled. Depending on how rapidly fungi grew in pure culture, isolates were either grown on potato dextrose broth (PDB; BD and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) prior to DNA extraction, or mycelium was scraped directly from plates. DNA was extracted from all isolates using a Wizard kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). DNA was suspended in 75 ml of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer preheated to 65°C. For long-term storage, isolates were kept on potato dextrose agar slants (pre-mixed PDA; BD and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at 4°C.

Wood samples were dried at room temperature (~21° C) for several weeks and sanded using an orbital sander equipped with 220-grit paper. Identifications were made by examining wood anatomy in cross section, based on descriptions by Panshin and de Zeeuw (1980).

2.3. Isolate identification

Isolates were identified using the universal fungal barcoding gene, the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), which includes ITS1, 5.8S, and ITS2 (Schoch et al. 2012). Primers used in this study were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA, USA). PCR was conducted using primers ITS4 (5’-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3’) and ITS5 (5’-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3’) (White et al. 1990), following the protocol in Macias (2017).

PCR products were visualized via gel electrophoresis on a 1.5% w/v agarose (Amresco, Solon, OH, USA) gel with 0.5% Tris-Borate-EDTA buffer (Amresco, Solon, OH, USA). SYBR Gold (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) was used as the nucleic acid stain, and bands were visualized on a UV transilluminator (Syngene, Frederick, MD, USA). PCR products were purified using ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Products were Sanger sequenced with the same primers used for PCR (Eurofins, Huntsville, AL, USA). Resulting sequences were clipped using the “Clip ends” function in CodonCode Aligner v 5.1.5 and searched in the NCBI GenBank BLASTn database (Altschul et al. 1990) and best-match identifications recorded for each isolate.

2.4. Identification of new species

Fungal isolates were considered to represent a putative new species if three or more identical sequences were recovered with identical low percentage (threshold ≤ 95%) BLASTn matches. The large subunit of the ribosomal ITS region (LSU) was also sequenced using primers LR0R (5’-ACCCGCTGAACTTAGC-3’) and LR5 (5’-TCCTGAGGGAAACTTCG-3’) (Vilgalys and Hester 1990) for each putative new species. PCR conditions were as described in Macias (2017). PCR products were visualized, purified, and sequenced as above.

In the following analyses, the default parameters of each software package were used unless otherwise noted. Two putative new species were confirmed phylogenetically by constructing ITS+LSU concatenated phylogenetic trees for each new species and its known relatives based on a combination of BLAST matches and previously published literature. MEGA7 v. 7.0.16 (Kumar et al. 2016) was used to align sequences (CLUSTAL-W, Larkin et al. 2007), select a best-fit model for estimating phylogeny, and construct maximum likelihood (ML) and maximum parsimony (MP) trees for each putative new species. For ML and MP analyses, 1000 bootstrap replicates were used. The alignments used default parameters. Initial alignments were trimmed such that all positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated. For maximum likelihood analyses, the Tamura 3-parameter substitution model with a gamma distribution (T92+G) was used (Tamura 1992). Both maximum parsimony analyses used the subtree-pruning-regrafting algorithm (Nei and Kumar 2000). Bayesian (BI) trees were constructed using Mr. Bayes v. 3.2.5 (Ronquist et al. 2012). Three hot and one cold independent MCMC chains were run simultaneously for 1,000,000 generations, and the first 25% were discarded as a burn-in. The average standard deviation of split frequencies statistic was checked to ensure convergence between chains (Ronquist et al. 2012) and was <0.01. Final parameter values and a final consensus tree were generated used the MrBayes “sump” and “sumt” commands respectively. The ML tree was preferred and support for its relationships in the other analyses was determined. Reference sequences used in each phylogenetic analysis are listed in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

2.5. Community and diversity analyses

Community and diversity analyses were used to answer two questions: (1) Are the fungal communities of B. lecontii conserved across millipede clade, millipede sex, wood substrate, and/or ecoregion? (2) What genera comprise the core fungal community associated with B. lecontii?

The effects of B. lecontii clade, sex, wood substrate, and ecoregion on the fungal community composition were analyzed by perMANOVA using the vegan package (Oksanen et al. 2018) in R version 3.4.3 (R Core Team 2017). Multilevel pairwise comparisons were performed using the pairwiseAdonis package (Arbizu 2017). Isolates where the fungal order or wood substrate were not identified were removed from the analysis. Additionally, isolates recovered from millipedes that were not part of a colony were removed. Ecoregion 45 was deleted from the analysis because its variance was significantly different from the other ecoregions (checked using function betadisper in vegan). Pairwise comparisons were only made for groups with 20 or more millipedes sampled, and in cases where more than one pairwise comparison was made, Bonferroni-corrected p-values are reported.

In addition, diversity indices were used to provide information about rarity and commonness of genera in the fungal community of B. lecontii, by site. Three alpha diversity indices were chosen according to recommendations laid out in Morris et al. (2014): number of genera present, Shannon’s diversity index, and Shannon’s equitability (evenness) index (formulae from Begon et al. 1990). The relationship between sample size and the three diversity metrics was examined using Spearman rank correlations.

A co-occurrence network was constructed using Gephi (Bastian et al. 2009) for fungal isolates obtained from B. lecontii at the genus level. Betweenness-centrality was used to measure relative contribution of each node (single fungal genus) to connectivity across the whole network. High betweenness-centrality values are typically associated with nodes located in the core of the network (Greenblum et al. 2011), which in this system are defined as fungal genera with multiple edges connecting multiple B. lecontii clades and multiple wood substrates. Low betweenness-centrality values indicate fungal genera with a more peripheral location in the network, with fewer edges connecting clades and wood substrates (Greenblum et al. 2011).

2.6. Pathogenicity testing

Twenty-one isolates (Table 2) representing the diversity of all collected isolates were initially chosen for live plating pathogenicity assay (hereafter referred to as “full-diversity assay”) with Brachycybe lecontii. A second assay (hereafter referred to as “Polyporales assay”) using nineteen isolates in the Polyporales (Table 3) were tested in a separate experiment. Three isolates from the full-diversity assay were re-tested in the second assay, for a total of 37 isolates used between both assays.

Table 2.

Results of pathogenicity assays using a representative set of fungal community members isolated from B. lecontii.

| Name | Order | Isolate | Time to 50% mortality |

% dead at 7 days HPP |

Log-rank P | Wilcoxon P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | ----------------------- | ---------- | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Pestalotiopsis microspora | Amphisphaeriales | BC0630 | --------------- | 20% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Chaetosphaeria myriocarpa | Chaetosphaeriales | BC0320 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Capronia dactylotricha | Chaetothyriales | BC1244 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Fonsecaea sp. | Chaetothyriales | BC1147 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Phialophora americana | Chaetothyriales | BC1193 | --------------- | 7% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Lecanicillium attenuatum | Hypocreales | BC0678 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Metarhizium flavoviride | Hypocreales | BC1163 | 136 HPP | 87% | <.0005*** | <.0005*** |

| Pochonia bulbillosa | Hypocreales | BC0029 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Trichoderma viride | Hypocreales | BC1216 | --------------- | 7% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Verticillium insectorum | Hypocreales | BC0482 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Mortierella aff. ambigua | Mortierellales | BC1150 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Mortierella sp. | Mortierellales | BC0530 | --------------- | 27% | 0.173 | 0.175 |

| aff. Apophysomyces sp. | Mucorales | BC1015 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Mucor abundans | Mucorales | BC1010 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Ramichloridium anceps | Mycosphaerellales | BC0329 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Bjerkandera adusta † | Polyporales | BC0310 | 36 HPP | 80% | <.0005*** | <.0005*** |

| Irpex lacteus † | Polyporales | BC0523 | 72 HPP | 47% | 0.014* | 0.0155* |

| Trametopsis cervina † | Polyporales | BC1143 | 36 HPP | 100% | <.0005*** | <.0005*** |

| Umbelopsis angularis | Umbelopsidales | BC0529 | --------------- | 13% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Umbelopsis isabellina | Umbelopsidales | BC1290 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Umbelopsis ramanniana | Umbelopsidales | BC1028 | --------------- | 0% | ------------- | ------------- |

| Overall | ----------------------- | ---------- | --------------- | ------- | <.0001*** | <.0001*** |

HPP = Hours post-plating. Asterisks denote significantly faster and greater mortality in a treatment, compared to the negative control:

= p<0.05,

= p<0.01,

= p<0.001. Both Log-rank P and Wilcoxon P are Bonferroni-corrected.

Denotes isolates tested again in the Polyporales pathogenicity assay.

Table 3.

Results of pathogenicity assays using a representative set of Polyporales isolated from B. lecontii. HPP = Hours post-plating.

| Name | Order | Isolate | Time to 50% mortality |

% dead at 7 days HPP |

Log-rank | P Wilcoxon P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | --------------- | ---------- | --------- | 20% | --------- | --------- |

| Bjerkandera adusta † | Polyporales | BC0310 | 36 HPP | 50% | 0.8484 | 0.4907 |

| Ceriporia lacerata | Polyporales | BC1158 | --------- | 10% | --------- | --------- |

| Ceriporiopsis gilvescens | Polyporales | BC0174 | --------- | 0% | --------- | --------- |

| Gloeoporus pannocinctus | Polyporales | BC0042 | 12 HPP | 100% | <.0007*** | <.0007*** |

| Irpex lacteus | Polyporales | BC1038 | --------- | 30% | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Irpex lacteus † | Polyporales | BC0523 | 72 HPP | 50% | 0.7119 | 0.5033 |

| Junghuhnia nitida | Polyporales | BC0528 | --------- | 10% | --------- | --------- |

| Phanerochaete cumulodentata | Polyporales | BC0709 | --------- | 0% | --------- | --------- |

| Phanerochaete sordida | Polyporales | BC0691 | 84 HPP | 60% | 0.2352 | 0.1603 |

| Phlebia acerina | Polyporales | BC1331 | --------- | 0% | --------- | --------- |

| Phlebia fuscoatra | Polyporales | BC1014 | --------- | 0% | --------- | --------- |

| Phlebia livida | Polyporales | BC0629 | --------- | 0% | --------- | --------- |

| Phlebia subserialis | Polyporales | BC0054 | --------- | 0% | --------- | --------- |

| Phlebiopsis flavidoalba | Polyporales | BC1426 | --------- | 10% | --------- | --------- |

| Phlebiopsis gigantea | Polyporales | BC1049 | --------- | 0% | --------- | --------- |

| Scopuloides rimosa | Polyporales | BC1046 | --------- | 0% | --------- | --------- |

| Trametopsis cervina † | Polyporales | BC1143 | 36 HPP | 100% | <.0007*** | <.0007*** |

| Trametopsis cervina | Polyporales | BC0494 | 36 HPP | 100% | <.0007*** | <.0007*** |

| Peniophora pithya | Russulales | BC1467 | --------- | 0% | <.0001*** | <.0001*** |

| Overall | --------------- | ---------- | --------- | ------- | <.0001*** | <.0001*** |

Asterisks denote significantly faster and greater mortality in a treatment, compared to the negative control:

= p<0.05,

= p<0.01,

= p<0.001. Both Log-rank P and Wilcoxon P are Bonferroni-corrected.

Denotes isolates used in initial pathogenicity assay.

Isolates were grown on GYEA and scraped to generate inoculum suspensions in sterile water. An ~500 μl aliquot of suspension was spread onto fresh GYEA plates at incubated at room temperature (21° C). After all plates were covered by fungal growth (~3 weeks), the millipedes were introduced for 7-d pathogenicity trials. Five individuals were placed on each plate. In the full-diversity assay, 15 millipedes were used for each treatment, while 10 were used in the Polyporales assay. For a negative control, millipedes were placed on sterile GYEA plates that were changed each time contaminating fungal growth was observed. These plates required replacement due to inadvertent inoculation by the millipede’s phoretic contaminants and gut microbes. Observations were made every 12 h for the first 36 h and then every 4 h for an additional 108 h until 7 d were complete. Mortality was assessed by failure of millipedes to move in response to external stimuli (Panaccione & Arnold 2017). At the end of the assay, samples of deceased individuals were preserved for chemical analyses. Surviving millipedes were returned to laboratory colonies for future studies.

Statistical analysis of survivorship was performed using the “Survival / Reliability” function in JMP 13.1.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons to the control treatment were performed for treatments that reached at least 25% mortality by the end of the trials (five treatments in the full-diversity assay, and seven in the Polyporales assay). Both log-rank and Wilcoxon tests were used. Log-rank tests score mortality at all time points evenly, while Wilcoxon tests score early mortality more heavily. For pairwise comparisons, Bonferroni corrections were applied such that the P-value reported by the analysis was multiplied by the number of comparisons made in each experiment.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Diversity and community structure

A total of 301 millipedes were collected from 3 of 4 known B. lecontii clades (Brewer et al. 2012) and from 20 sites across 7 states (Table 1). Our study recovered 102 males and 146 mature females. Most millipedes were engaged in feeding behavior, with their heads buried in fungus growing on the log (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Brachycybe lecontii colony feeding on the white-rot fungus Irpex lacteus (Basidiomycota: Polyporales). Mature adults (larger individuals in the photo) range from 1.5 cm – 2 cm in length.

Brachycybe lecontii was found to associate with a large and diverse community of fungi, including at least 176 genera in 39 fungal orders from four phyla (Supplemental Table 4). A majority of these fungi (59%) were members of Ascomycota. Of all the genera of fungi found in this study, 40% were represented by a single isolate, and only 13% had 10 or more isolates. The most common order was the Hypocreales, containing 26% of all isolates resolved to at least order. The five next most common orders were the Polyporales (9% of all isolates), Chaetothyriales (8%), Xylariales (6%), Capnodiales (5%), and Eurotiales (5%). All other orders contained fewer than 50 isolates (<5%).

Alpha diversity was assessed at the genus level by millipede clade, wood substrate, and site. Clade 1 included 31 fungal genera, clade 3 included 156, and clade 4 included 69. The number of fungal genera obtained from each wood substrate were as follows: Liriodendron (114 genera), Quercus (74), Betula (54), Carya (45), Fagus (33), Ulmus (19), Acer (18), Pinus (11), Carpinus (10), and Fraxinus (10). However, the number of millipedes sampled for Clade 1, and all wood substrates except Quercus and Liriodendron, are likely not sufficient to capture the full diversity of the communities with culture-based methods (n<20).

At each site, fungal alpha diversity varied from 3 genera at SC2 to 63 genera at WV1 with a mean of 23 per site (Table 4). Shannon’s diversity index and Shannon’s equitability were also calculated for each site. Shannon’s diversity index ranged from 0.95 in SC2 to 3.79 in WV2. Shannon’s equitability ranged from 0.977 in AR1 and VA2 to 0.848 in TN1 (Table 4). Sites with the five highest Shannon’s diversity index values did not overlap with sites with the five highest site equitability values (Table 4). Three diversity metrics were found to be correlated with sample size (alpha diversity r = 0.70, Shannon’s diversity index r = 0.58, Shannon’s equitability index r = −0.28), indicating that many more millipedes would be needed to capture the full fungal diversity using culture-based methods. The wide ranges of the three diversity metrics across sites raises questions about functional redundancies in the fungal communities.

Table 4.

Collection information and genus-level diversity indices for each site.

| Site | # millipedes sampled |

Alpha diversity |

Shannon’s diversity index |

Shannon’s equitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR1 | 6 | 11 | 2.342 | 0.977 |

| AR2 | 6 | 14 | 2.497 | 0.946 |

| AR3 | 13 | 17 | 2.590 | 0.914 |

| AR4 | 22 | 26 | 3.064 | 0.941 |

| AR5 | 14 | 19 | 2.801 | 0.951 |

| AR6 | 12 | 18 | 2.583 | 0.894 |

| GA1 | 9 | 13 | 2.378 | 0.927 |

| OK1 | 14 | 18 | 2.737 | 0.947 |

| SC1 | 22 | 14 | 2.262 | 0.857 |

| SC2 | 4 | 3 | 0.950 | 0.865 |

| TN1 | 42 | 42 | 3.170 | 0.848 |

| VA1 | 4 | 34 | 3.301 | 0.936 |

| VA2 | 8 | 11 | 2.342 | 0.977 |

| VA3 | 15 | 24 | 3.043 | 0.957 |

| VA4 | 5 | 7 | 1.787 | 0.918 |

| WV1 | 29 | 63 | 3.784 | 0.913 |

| WV2 | 24 | 57 | 3.790 | 0.938 |

| WV3 | 4 | 16 | 2.599 | 0.937 |

| WV4 | 12 | 24 | 3.033 | 0.954 |

| WV5 | 36 | 34 | 3.045 | 0.864 |

To statistically explore relationships between fungal community composition and millipede sex, millipede clade, wood substrate, and ecoregion, perMANOVAs and pairwise multilevel comparisons were used. No relationship was found between millipede sex and fungal community composition (p = 0.353, R2 = 0.005), but relationships were found for millipede clade (p = 0.045, R2 = 0.006), wood substrate (p = 0.002, R2 = 0.049), and ecoregion (p = 0.001, R2 = 0.012). However, effect size is very small for each of these factors, indicating that while there are significant relationships between these factors and the fungal community, the strength of those relationships is weak. Pairwise multilevel corrections indicate that there are significant differences between the fungal communities of Clade 1 and 3 (p = 0.009, R2 = 0.015) and 4 and 3 (p = 0.003, R2 = 0.015), but not 1 and 4 (p = 0.096, R2 = 0.014). For wood substrate, only the fungal communities of Liriodendron and Quercus were compared (see Methods), and they were significantly different (p = 0.045, R2 = 0.015). For ecoregion, there are significant differences between the fungal communities of ecoregions 36 and 39 (p = 0.018, R2 = 0.014) and 66 and 69 (p = 0.006, R2 = 0.018), but not 36 and 37 (p = 1.000, R2 = 0.007), 36 and 66 (p = 0.084, R2 = 0.025), 37 and 66 (p = 0.462, R2 = 0.029), or 37 and 69 (p = 0.300, R2 = 0.010). For all of these pairwise comparisons, the effect size was small. Increased sampling depth should help clarify whether any of these factors truly impact the fungal community composition.

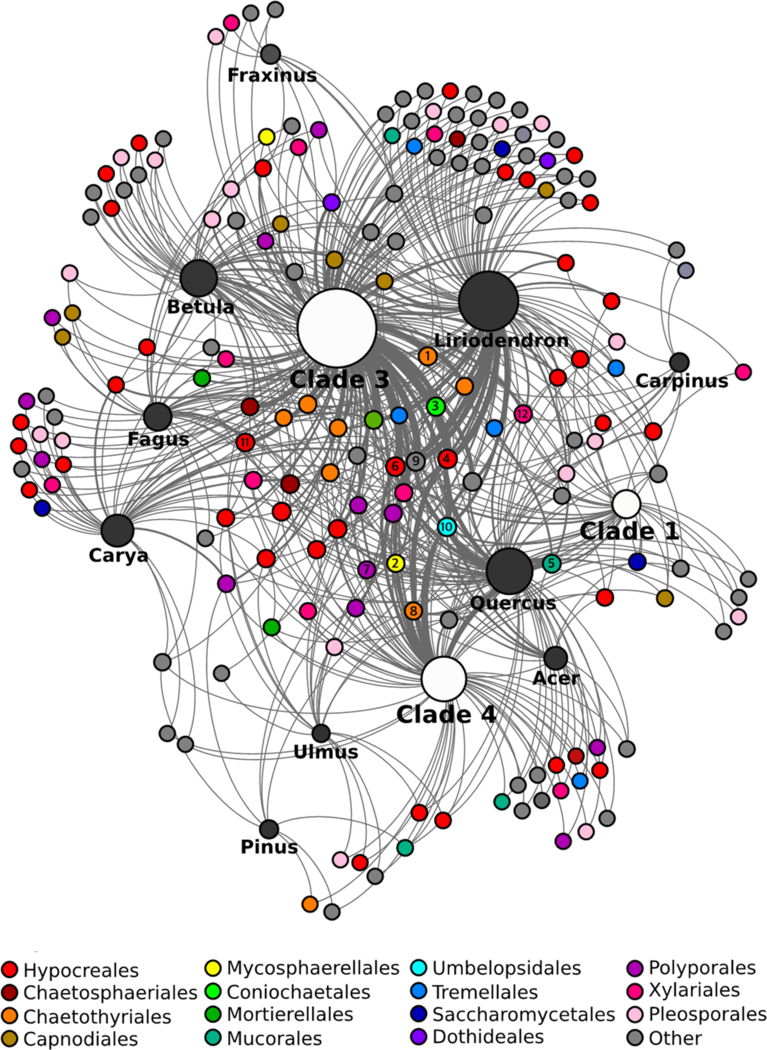

A network analysis and betweenness-centrality scores were used to examine how the structure of the fungal community is affected by different millipede clades and wood substrates (Figure 2). As a whole, community structure was heterogeneous across millipede clades and wood substrates. However, some genera of fungi were consistently associated with most clades and wood substrates, as indicated by their betweenness-centrality scores. Twelve fungal genera showed high connectivity across the whole network (betweenness-centrality values > 0.5) (Figure 2). These included 1) Phialophora (1.55), 2) Ramichloridium (1.44), 3) Mortierella (1.28), 4) Trichoderma (1.03), 5) Mucor (1.02), 6) Verticillium (0.90), 7) Phanerochaete (0.89), 8) Fonsecaea (0.84), 9) Penicillium (0.75), 10) Umbelopsis (0.73), 11) Cosmospora (0.68), and 12) Xylaria (0.63). All other fungal genera fell below a 0.5 threshold, including 144 genera with betweenness-centrality values of 0.0, indicating low presence across millipede communities.

Figure 2.

Fungal community network across B. lecontii clades and wood substrates. Small unlabeled nodes represent fungal genera, color-coded by taxonomic order. Orders with fewer than 10 isolates are lumped into “Other”. Genus nodes with betweenness-centrality scores >0.5 are labeled with the rank of their betweenness-centrality score (1–12). White and black nodes represent clades and wood substrates, respectively. For these, the size of the node represents the relative sample size. Edges represent interactions between a fungal genus and a wood substrate/clade. Edge boldness indicates the strength of the interaction.

The betweenness-centrality scores from the network revealed that the core of the Brachycybe-associated fungal community is comprised of a small group of fungal genera that is fairly representative of the diversity in the broader millipede-associated fungal community. The structure of the network indicates that these core fungi are consumed by many individuals from different lineages of B. lecontii across its reported range and across many wood substrates. As such, these fungi may be the preferred fungal food source for B. lecontii. Alternatively, these fungi may readily survive gut passage, which would result in them being over-represented after culturing.

Only a single member of the order Polyporales, Phanerochaete, falls in the core of the fungal network, a highly unexpected result given that the majority of community science records of Brachycybe interacting with fungi appear to show the millipedes associating with Polyporales and closely allied decay fungi (Supplemental Table 1). It is possible that these fungi may serve a vital role, despite their near-absence from the core network. One such role may be to precondition substrates for arthropod colonization. For example, vascular wilt fungi predispose trees to attack by wood-boring ambrosia beetles (Hulcr & Stelinski 2017). The Verticillium wilt pathogen, V. nonalfalfae, predisposes tree-of-heaven to mass colonization by the ambrosia beetle Euwallacea validus. However, the fungal community recovered from surface-disinfested beetles does not include V. nonalfalfae (Kasson et al. 2013). As such, V. nonalfalfae might be overlooked in its role to precondition substrates for arthropod colonization. A second possibility is that millipedes do actively utilize wood decay fungi but do not exhibit strict fidelity with single species or rely disproportionately on individual fungal community members (Kasson et al. 2013, Jusino et al. 2015, Jusino et al. 2016). Nevertheless, these results, much like studies examining fungal communities in red-cockaded woodpecker excavations, may indicate millipedes are either: (1) selecting degraded logs with a pre-established preferred fungal community, or (2) selecting fresh logs without any evidence of decay, then subsequently facilitating colonization by specific fungi (Jusino et al. 2015, Jusino et al. 2016).

3.2. Pathogenicity testing

To determine how members of the Polyporales and other fungi interact with B. lecontii, millipedes were challenged with pure cultures of a representative set of fungal isolates for 7 d. Only four of 21 isolates caused significant mortality after 7 d (Table 2): Metarhizium flavoviride (Hypocreales; Log-rank p < 0.0005), Bjerkandera adusta (Polyporales; Log-rank p < 0.0005), Irpex lacteus (Polyporales; Log-rank p = 0.014), and Trametopsis cervina (Polyporales; Log-rank p < 0.0005). Interestingly, the known virulent entomopathogens Lecanicillium attenuatum, Pochonia bulbillosa, and Verticillium insectorum caused little to no mortality to Brachycybe after 7 d of continuous exposure (Table 2).

Since three of the four pathogenic fungi were in the Polyporales, a follow-up experiment was performed using 18 isolates from the Polyporales, and one isolate of Peniophora (Russulales), the only fungus reported in the literature to be in association with Brachycybe (Gardner 1975). Only three of these isolates were significantly more pathogenic than the sterile agar control (Table 3): Gloeoporus pannocinctus (Polyporales; Log-rank p < 0.0007), and two isolates of Trametopsis cervina (Polyporales; Log-rank p for both <0.0007). The Bjerkandera isolate and the Irpex isolate that were significantly pathogenic in the first assay were not significantly pathogenic in the second. However, the number of individuals used in the second assay was 10 per treatment, as compared to 15 per treatment in the first assay, and two individuals in the control treatment in the second assay were dead by the end of the assay. Together, these factors suggest that the results of the second assay are less reliable.

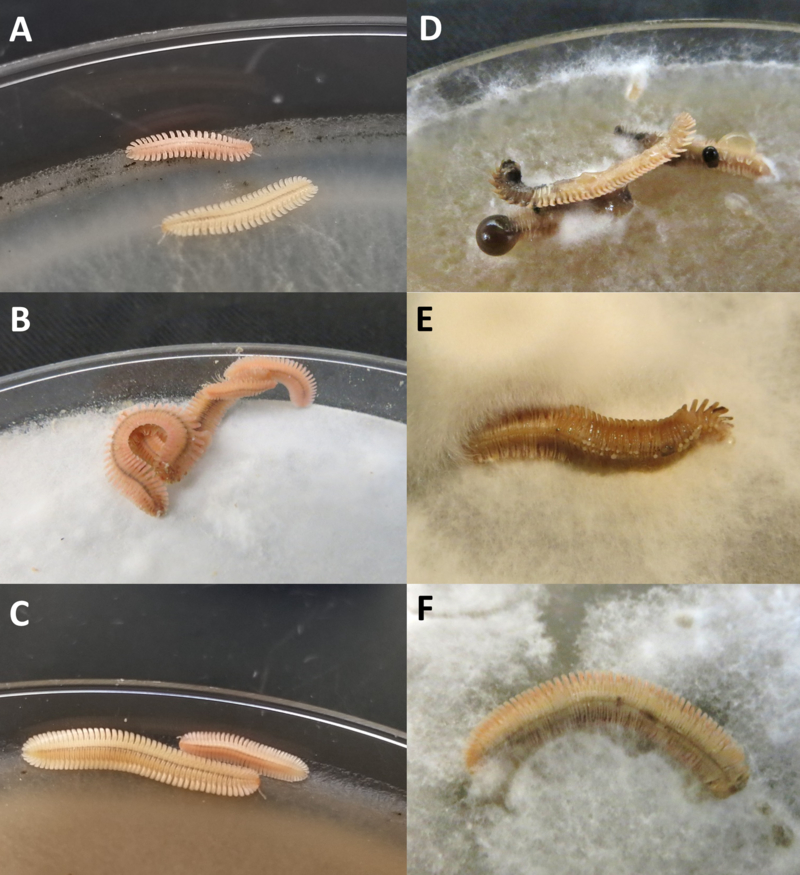

The results of the two pathogenicity assays indicate that several members of the Polyporales, including Bjerkandera, Irpex, Trametopsis, and Gloeoporus, may be pathogenic to Brachycybe millipedes (Figure 3), while three of the four entomopathogenic Hypocreales were not pathogenic. Additionally, seven other fungal orders caused little to no mortality (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Representative outcomes of live-plating assay with Polyporales. A-C show B. lecontii with no outward disease symptoms after 7 d of exposure to the indicated fungus, and D-F show millipedes that were killed by the indicated fungus. In all three examples of mortality, fungal hyphae are growing over the millipede. A: Phlebia livida (BC0629), B: Ceriporia lacerata (BC1158), C: Scopuloides rimosa (BC1046), D: Trametopsis cervina (BC0494), E: Bjerkandera adusta (BC0310), F: Irpex lacteus (BC0523).

It is unclear how B. lecontii resists the well-documented entomopathogenic effects of many Hypocreales with the exception of Metarhizium (Hajek & St. Leger 1994). Parallel studies by Macias (2017) demonstrated that the Hypocrealean isolates used in the Brachycybe pathogenicity assays were pathogenic to insects. In contrast, the high incidence of pathogenicity among Brachycybe-associated Polyporales was unexpected. In a separate study, insects challenged with these same Polyporales were completely unaffected (Macias 2017).

One hypothesis is that Polyporales, depending on whether they are in a growth phase or a fruiting phase (Calvo et al. 2002, Lu et al. 2014), may produce chemicals that inadvertently harm millipedes. Since fruiting bodies were never observed in culture, it is likely that the fungi used in the pathogenicity assays were in a growth phase, which proved detrimental to B. lecontii. A second hypothesis that may explain pathogenicity among the Polyporales is that experiments relying on pure cultures of a single fungus do not account for fungus-fungus interactions or interactions between fungi and other organisms (Li & Zhang 2014, Macias 2017).

3.3. New species

At least seven putative new species were identified, but only two were investigated in this study. The five not examined are “aff. Coniochaeta” (Coniochaetales), “aff. Leptodontidium” (Helotiales), “Pseudonectria aff. buxi” (Hypocreales), “aff. Fonsecaea sp.” (Chaetothyriales) and “aff. Oidiodendron” (Onygenales). The two examined species were from the phylum Mucoromycota (Spatafora et al. 2017), in the orders Mortierellales and Mucorales.

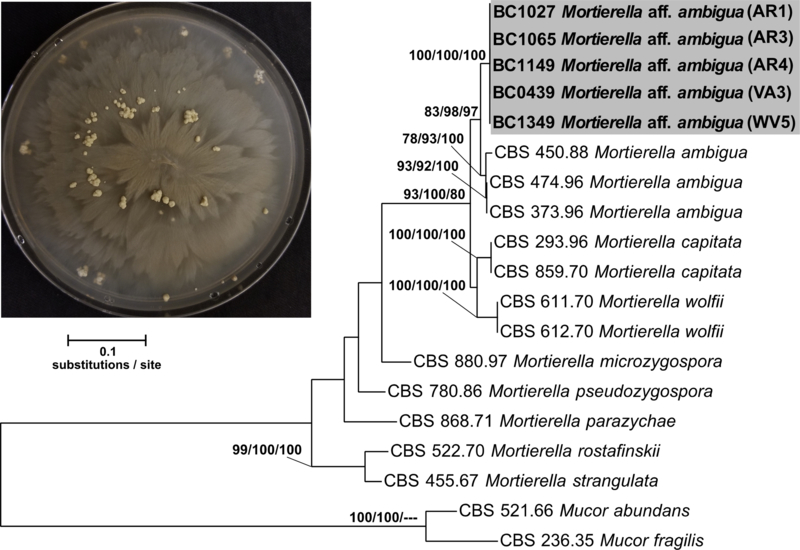

Mortierella aff. ambigua is represented by 27 clonal isolates from seven widespread collection sites (AR1, AR3, AR4, VA3, WV2, WV4, and WV5), five wood substrates (Acer, Fagus, Fraxinus, Liriodendron, and Quercus), and two millipede clades (Clade 3 and 4). These isolates are 92% identical to strain “Mortierella ambigua CBS 450.88” and were deposited as GenBank accessions MH971275 and MK045304 (Supplemental Table 2 & 4). All isolates of “Mortierella aff. ambigua” produced large gemmae (Embree 1963, Aki et al. 2001) as the cultures aged past 7 d. These structures grew to at most half a centimeter across and were present on the surface and embedded in the media (Figure 4). Sporangia were not observed in any of the Mortierella aff. ambigua isolates so comparisons with known Mortierella sporangial morphology could not be made. More in-depth morphological studies are needed before a formal description can be made.

Figure 4.

Concatenated ITS+LSU phylogenetic tree of Mortierella aff. ambigua and close relatives. Bootstrap support and posterior probabilities are indicated near each node (ML/MP/BI), and nodes with >50% support are labeled. Dashes indicate that a particular node did not appear in the indicated analysis. The grey box indicates the isolates belonging to Mortierella aff. ambigua. A representative culture of the fungus with gemmae is shown in the upper left.

The initial alignment included 1149 characters and the final dataset was reduced to 834 characters, and the maximum parsimony analysis yielded 7 most-parsimonious trees with a length of 732. Phylogenetic analysis of a concatenated ITS+LSU 17-isolate dataset including 5 Mortierella aff. ambigua confirmed placement of this novel species sister to M. ambigua sensu stricto (Figure 4) and inside the previously described Clade 5 of Mortierella (Wagner et al. 2013). Clade 5 Mortierella species are common from soil but have also been associated with amphipods and invasive mycoses in humans. More distantly related species such as Mortierella beljakovae and Mortierella formicicola have known associations with ants but the nature of this relationship remains unclear (Wagner et al. 2013).

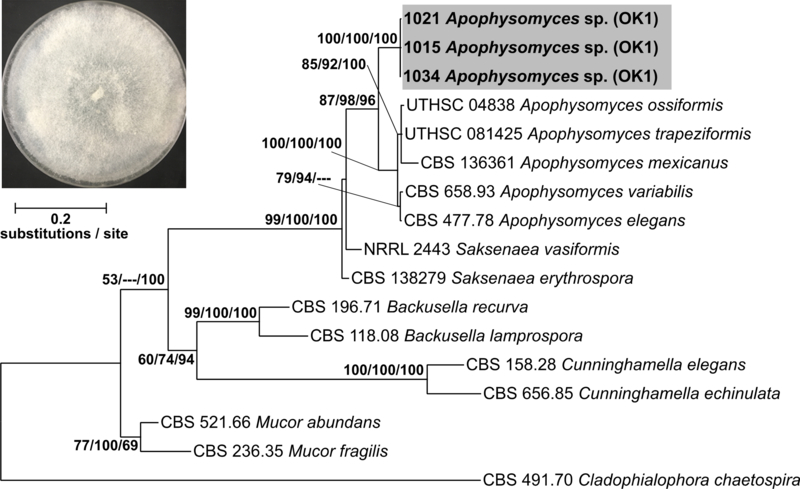

The second putative new species, aff. Apophysomyces sp., is represented by five isolates from one site (OK1), one wood substrate (Quercus), and one millipede clade (Clade 4). These isolates are 84% identical to strain “Apophysomyces ossiformis strain UTHSC 04–838” and were deposited as GenBank accessions MH971276 and MK045305 (Supplemental Table 3 & 4). Sporangial morphology of these isolates aligns with described features for this genus (Alvarez et al. 2010, Bonifaz et al. 2014), but more in-depth morphological studies are needed.

The initial alignment included 1258 characters and the final dataset was reduced to 935 characters, and the maximum parsimony analysis yielded 3 most-parsimonious trees with a length of 1101. Phylogenetic analysis of a concatenated ITS+LSU 16 isolate dataset including three aff. Apophysomyces sp. isolates confirmed placement of this novel species sister to the clade containing known species of Apophysomyces sp. (Figure 5). The combined branch length among all known species of Apophysomyces (0.0589 substitutions/site) is less than the branch length separating our putative new species and these known species (0.0903 substitutions/site), providing evidence that our novel species is in fact, a novel genus. The genus Apophysomyces has been isolated from soil but is also known to cause severe mycoses in immunocompetent humans (Alvarez et al. 2010, Etienne et al. 2012, Bonifaz et al. 2014).

Figure 5.

Concatenated ITS+LSU phylogenetic tree of aff. Apophysomyces sp. and close relatives. Bootstrap support and posterior probabilities are indicated near each node (ML/MP/BI), and nodes with >50% support are labeled. Dashes indicate that a particular node did not appear in the indicated analysis. The grey box indicates the isolates belonging to aff. Apophysomyces sp. A representative culture of the fungus is shown in the upper left.

Despite the use of more classical culture-based approaches, the recovery of seven putative new species highlights the vast amount of undescribed fungal biodiversity associated with millipedes. Culture-independent approaches will undoubtedly uncover many additional new species, possibly including some from unculturable lineages of fungi.

3.4. Summary

Brachycybe lecontii associates with a large and diverse community of fungi, including at least 176 genera in 39 fungal orders from four phyla. Significant differences in the fungal community among wood substrates, millipede clades, and ecoregions indicate that these factors influence the composition of millipede-associated fungal communities, while millipede sex does not. Follow-up studies will help determine if these factors remain important determinants in fungal community composition. One putative new species and one putative new genus of fungi were found and examined in this study, and there is evidence for several additional new species that remain to be assessed phylogenetically. Additional loci and morphological studies are needed to assess the phylogenetic placement of these fungal taxa.

The core fungal community of B. lecontii consists of fungi from at least nine orders, primarily members of phylum Ascomycota. While community science records of Brachycybe show the millipedes interacting with almost entirely Basidiomycota, especially Polyporales, only one genus from that order occurs in the core of the network. The disagreement between the bulk of community science records and the core network identified in this study can be explained by the fact that observers often overlook the dozens to hundreds of microfungi that co-occur on and in the large Polyporales fruiting bodies.

Four genera in the Polyporales were found to be pathogenic to Brachycybe in live-plating assays, while three genera of notorious entomopathogens from the Hypocreales did not cause significant mortality in millipedes. Only a single fungus outside the Polyporales caused significant mortality. However, the results of simple culture-based experiments may not be accurate representations of what happens when these organisms interact in nature.

In less than a decade, the research on arthropod-fungus interactions has accelerated and led to the discoveries of several new associations (Voglmayr et al. 2011, Menezes et al. 2015, You et al. 2015). This study demonstrates that the complexity of millipede-fungus interactions has been underestimated and these interactions involve many undescribed species. This paper represents the first comprehensive survey of fungal communities associated with any member of the millipede subterclass Colobognatha. We anticipate that future studies of millipede-fungus interactions will yield countless new fungi and clarify the ecology of these interactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Derek Hennen, Mark Double, Nicole Utano, and Toby Grapner for assistance with collection of millipedes and/or maintenance of cultured fungi. AM was supported by WVU Ruby Fellowship. MTK was supported by the West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, Morgantown, WV.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article include Tables S1-S4.

References

- Aki T, Nagahata Y, Isihara K, Tanaka Y, Morinaga T, Higashiyama K, Akimoto K, Fujikawa S, Kawamoto S, Shigeta S, Ono K, and Suzuki O. 2001. Production of arachidonic acid by filamentous fungus, Mortierella alliacea strain YN-15. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society. 78(6): 599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, and Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 215(3): 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez E, Stchigel AM, Cano J, Sutton DA, Fothergill AW, Chander J, Salas V,Rinaldi MG, and Guarro J. 2010. Molecular phylogenetic diversity of the emerging mucoralean fungus Apophysomyces: proposal of three new species. Revista Iberoamericana de Micologia. 27(2): 80–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SB, Gerritsma S, Yusah KM, Mayntz D, Hywel-Jones NL, Billen J, Boomsma JJ, and Hughes DP. 2009. The life of a dead ant: the expression of an adaptive extended phenotype. The American Naturalist. 174(3): 424–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbizu PM 2017. pairwiseAdonis: Pairwise multilevel comparison using adonis. R package version 0.0.1. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian M, Heymann S, and Jacomy M. 2009. Gephi: an open-source software for exploring and manipulating networks. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. [Google Scholar]

- Begon M, Harper JL, and Townsend CR. 1990. Ecology--individuals, populations, communities. 2nd ed. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Bonifaz A, Stchigel AM, Guarro J, Guevara E, Pintos L, Sanchis M, and Cano-Lira JF. 2014. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis produced by the new species Apophysomyces mexicanus. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 52(12): 4428–4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonkowski M, Scheu S, and Schaefer M. 1998. Interactions of earthworms (Octolasion lacteum), millipedes (Glomeris marginata), and plants (Hordelymus europaeus) in a beechwood on a basalt hill: implications for litter decomposition and soil formation. Applied Soil Ecology. 9(1): 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MS and Bond JE. 2013. Ordinal-level phylogenetics of the arthropod class Diplopoda (millipedes) based on an analysis of 221 nuclear protein-coding loci generating using next-generation sequence analyses. PLoS ONE. 8(11): e79935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MS, Spruill CL, Rao NS, and Bond JE. 2012. Phylogenetics of the millipede genus Brachycybe Wood, 1864 (Diplopoda: Platydesmida: Andrognathidae): patterns of deep evolutionary history and recent speciation. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 64(1): 232–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BugGuide.net web application at http://www.bugguide.net. Accessed 12 November 2018.

- Bultman TL and Mathews PL. 1996. Mycophagy by a millipede and its possible impact on an insect-fungus mutualism. Oikos. 75(1): 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo AM, Wilson RA, Bok JW, and Keller NP. 2002. Relationship between secondary metabolism and fungal development. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 66(2): 447–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley EA, Rowley HE, and Speed MP. 2015. A field demonstration of the costs and benefits of group living to edible and defended prey. Biological Letters. 11(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dury GJ, Bede JC, and Windsor DM. 2014. Preemptive circular defence of immature insects: definition and occurrences of cycloalexy revisited. Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. [Google Scholar]

- Embree RW 1963. Observations on Mortierella vesiculosa. Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 46(4): 560–564. [Google Scholar]

- Enghoff H and Santamaria S. 2015. Infectious intimacy and contaminated caves— three new species of ectoparasitic fungi (Ascomycota: Laboulbeniales) from blaniulid millipedes (Diplopoda: Julida) and inferences about their transmittal mechanisms. Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 15(2): 249–263. [Google Scholar]

- Etienne KA, Gillece J, Hilsabeck R, Schupp JM, Colman R, Lockhart SR, Gade L, Thompson EH, Sutton DA, Neblett-Fanfair R, and Park BJ. 2012. Whole genome sequence typing to investigate the Apophysomyces outbreak following a tornado in Joplin, Missouri, 2011. PLoS One, 7(11): e49989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 39: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner MR 1975. Revision of the millipede family Andrognathidae in the Nearctic region. Memoirs of the Pacific Coast Entomological Society. 5: 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Greenblum S, Turnbaugh PJ, and Borenstein E. 2012. Metagenomic systems biology of the human gut microbiome reveals topological shifts associated with obesity and inflammatory bowel disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109(2): 594–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek AE and St Leger RJ. . 1994. Interactions between fungal pathogens and insect hosts. Annual Review of Entomology. 39(1): 293–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge KT, Hajek AE, and Gryganskyi A. 2017. The first entomophthoralean killing millipedes, Arthrophaga myriapodina n. gen. n. sp., causes climbing before host death. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 149: 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman RL 1980. Studies on spiroboloid millipeds. XI. On the status of Spirobolus nattereri Humbert and DeSaussure, 1870, and some species traditionally associated with it (Rhinocricidae). Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia. 33: 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Hulcr J and Stelinski LL. 2017. The ambrosia symbiosis: from evolutionary ecology to practical management. Annual Review of Entomology. 62: 285–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- iNaturalist.org web application at http://www.inaturalist.org. Accessed 12 November 2018.

- JMP, version 13.1.0. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA, 1989-2018.

- Jusino MA, Lindner DL, Banik MT, Rose KR, and Walters JR. 2016. Experimental evidence of a symbiosis between red-cockaded woodpeckers and fungi. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 283: 20160106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jusino MA, Lindner DL, Banik MT, and Walters JR. 2015. Heart rot hotel: fungal communities in red-cockaded woodpecker excavations. Fungal Ecology. 14: 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kasson MT, Wickert KL, Stauder CM, Macias AM, Berger MC, Simmons DR, Short DP, DeVallance DB, and Hulcr J. 2016. Mutualism with aggressive wood-degrading Flavodon ambrosius (Polyporales) facilitates niche expansion and communal social structure in Ambrosiophilus ambrosia beetles. Fungal Ecology. 23: 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kasson MT, O’Donnell K, Rooney AP, Sink S, Ploetz RC, Ploetz JN, Konkol JL, Carrillo D, Freeman S, Mendel Z, Smith JA, Black AW, Hulcr J, Bateman C, Stefkova K, Campbell PR, Geering ADW, Dann EK, Eskalen A, Mohotti K, Short DPG, Aoki T, Fenstermacher KA, Davis DD, Geiser DM. 2013. An inordinate fondness for Fusarium: Phylogenetic diversity of fusaria cultivated by ambrosia beetles in the genus Euwallacea on avocado and other plant hosts. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 56: 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo SI, Koshio C, and Tanabe T. 2009. Male egg-brooding in the millipede Yamasinaium noduligerum (Diplopoda: Andrognathidae). Entomological Science. 12(3): 346–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kudo SI, Akagi Y, Hiraoka S, Tanabe T, and Morimoto G. 2011. Exclusive male egg care and determinants of brooding success in a millipede. Ethology. 117(1): 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, and Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 33(7): 1870–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallance IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, and Higgins DG. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 23(21): 2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JM and Samways MJ. 2003. Litter breakdown by the Seychelles giant millipede and the conservation of soil processes on Cousine Island, Seychelles. Biological Conservation. 113(1): 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Li GH and Zhang KQ. 2014. Nematode-toxic fungi and their nematicidal metabolites In: Zhang KQ., Hyde K (eds) Nematode-Trapping Fungi. Fungal Diversity Research Series, vol 23 Springer, Dordrecht. [Google Scholar]

- Lilleskov EA and Bruns TD. 2005. Spore dispersal of a resupinate ectomycorrhizal fungus, Tomentella sublilacina, via soil food webs. Mycologia. 97(4): 762–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MJ, Fan W, Wang W, Chen T, Tang Y, Chu F, Chang T, Wang SY, Li MY, Chen YH, and Lin ZS. 2014. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses of the medicinal fungus Antrodia cinnamomea for its metabolite biosynthesis and sexual development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111(44). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias AM 2017. Diversity and function of fungi associated with the fungivorous millipede, Brachycybe lecontii. MS thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manton SM 1961. The evolution of arthropodan locomotory mechanisms, part 7. Functional requirements and body design in Colobognatha (Diplopoda), together with a comparative account of diplopod burrowing techniques, trunk musculature, and segmentation. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 44(299): 383–462. [Google Scholar]

- Marek P, Shear W, and Bond J. 2012. A rediscription of the leggiest animal, the millipede Illacme plenipes, with notes on its natural history and biogeography (Diplopoda, Siphonophorida, Siphonorhinidae). ZooKeys. 241: 77–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes C, Vollet-Neto A, Marsaioli AJ, Zampieri D, Fontoura IC, Luchessi AD, and Imperatriz-Fonseca VL. 2015. A Brazilian social bee must cultivate fungus to survive. Current Biology. 25(21): 2851–2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhaljova EV, Golovatch SI, Korsós Z, Chen CC, and Chang HW. 2010. The millipede order Platydesmida (Diplopoda) in Taiwan, with descriptions of two new species. Zootaxa. 2178: 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Morris EK, Caruso T, Buscot F, Fischer M, Hancock C, Maier C,TS, Meiners T, Müller C, Obermaier E, Prati D, Socher SA, Sonneman I, Wäschke N, Wubet T, Wurst S, and Rillig MC. 2014. Choosing and using diversity indices: insights for ecological applications from the German Biodiversity Exploratories. Ecology and Evolution. 4(18): 3514–3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M and Kumar S. 2000. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MH; Szoecs E, and Wagner H. 2018. Vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.5–3. URL https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan. [Google Scholar]

- Panaccione DG and Arnold SL. 2017. Ergot alkaloids contribute to virulence in an insect model of invasiva aspergillosis. Scientific Reports. 7: 8930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panshin AJ and de Zeeuw C. 1980. Textbook of wood technology. 4th edition McGraw-Hill, Inc; New York, U.S: 407–645. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2017. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: URL https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Read H and Enghoff H. 2009. The order Siphonophorida–A taxonomist’s nightmare? Lessons from a Brazilian collection. Soil Organisms. 81: 543–556. [Google Scholar]

- Read HJ and Enghoff H. 2018. Siphonophoridae from Brazilian Amazonia Part 1–The genus Columbianum Verhoeff, 1941 (Diplopoda, Siphonophorida). European Journal of Taxonomy. 477: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Reboleira ASP, Enghoff H, and Santamaria S. 2018. Novelty upon novelty visualized by rotational scanning electron micrographs (rSEM): Laboulbeniales on the millipede order Chordeumatida. PloS One, 13: e0206900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J, Jones TH, Sierwald P, Marek PE, Shear WA, Brewer MS, Kocot KM, and Bond JE. 2018. Step-wise evolution of complex chemical defenses in millipedes: a phylogenomic approach. Scientific Reports. 8: 3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, and Huelsenbeck JP. 2012. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large space. Systematic Biology. 61(3): 539–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy HE, Steinkraus DC, Eilenberg J, Hajek AE, and Pell JK. 2006. Bizarre interactions and endgames: entomopathogenic fungi and their arthropod hosts. Annual Review of Entomololgy. 51: 331–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria S, Enghoff H, and Reboleira ASPS. 2014. Laboulbeniales on millipedes: Diplopodomyces and Troglomyces. Mycologia. 106(5): 1027–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch CL, Seifert KA, Huhndorf S, Robert V, Spouge JL, Levesque CA, Chen W, Bolchacova E, Voigt K, Crous PW, and Miller AN. 2012. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109(16): 6241–6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear WA 2015. The chemical defenses of millipedes (Diplopoda): biochemistry, physiology, and ecology. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 61: 78–117. [Google Scholar]

- Shelley RM, McAllister CT, and Tanabe T. 2005. A synopsis of the millipede genus Brachycybe Wood, 1864 (Platydesmida: Andrognathidae). Fragmenta Faunistica. 48(2): 137–166. [Google Scholar]

- Shorter PL, Hennen DA, and Marek PE. 2018. Cryptic diversity in Andrognathuscorticarius Cope, 1869 and description of a new Andrognathus species from New Mexico (Diplopoda, Platydesmida, Andrognathidae). ZooKeys. 786: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons DR, Li Y, Bateman CC, and Hulcr J. 2016. Flavodon ambrosius sp. nov., a basidiomycetous mycosymbiont of Ambrosiodmus ambrosia beetles. Mycotaxon. 131(2): 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Spatafora JW, Chang Y, Benny GL, Lazarus K, Smith ME, Berbee ML, Bonito G, Corradi N, Grigoriev I, Gryganskyi A, and James TY. 2017. A phylum-level phylogenetic classification of zygomycete fungi based on genome- scale data. Mycologia. 108(5): 1028–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava PD and Srivastava YN. 1967. Orthomorpha sp.—a new predatory millipede on Achatina fulica in Andamans. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 23(9): 776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez SE, Brookfield ME, Catlos EJ, and Stöckli DF. 2017. A U-Pb zircon age constraint on the oldest-recorded air-breathing land animal. PLoS ONE. 12(6): e0179262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K 1992. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G + C-content biases. Molecular Biology and Evolution 9:678–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R, and Hester M. 1990. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. Journal of Bacteriology. 172: 4239–4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr H, Mayer V, Maschwitz U, Moog J, Djieto-Lordon C, and Blatrix R. 2011. The diversity of ant-associated black yeasts: insights into a newly discovered world of symbiotic interactions. Fungal Biology. 115(10): 1077–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner L, Stielow B, Hoffmann K, Petkovits T, Papp T, Vágvö C, De Hoog GS, Verkley G, and Voigt K. 2013. A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of the Mortierellales (Mortierellomycotina) based on nuclear ribosomal DNA. Persoonia: Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 30: 77–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee SJWT, and Taylor JW. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. 18(1): 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HM and Anderson LI. 2004. Morphology and taxonomy of Paleozoic millipedes (Diplopoda: Chilognatha: Archipolypoda) from Scotland. Journal of Paleontology. 78(1): 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Wong VL 2018. Natural history of the social millipede Brachycybe lecontii (Wood, 1864). MS thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood WF, Hanke FJ, Kubo I, Carroll JA, and Crews P. 2000. Buzonamine, a new alkaloid from the defensive secretion of the millipede, Buzonium crassipes. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 28(4): 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KA 1979. Trichomycetes and oxyuroid nematodes in the millipede, Narceus annularis. Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington. 46: 213– 223. [Google Scholar]

- You L, Simmons DR, Bateman CC, Short DP, Kasson MT, Rabaglia RJ, and Hulcr J. 2015. New fungus-insect symbiosis: culturing, molecular, and histological methods determine saprophytic Polyporales mutualists of Ambrosiodmus ambrosia beetles. PLoS ONE. 10(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.